Abstract

Power management in advanced power distribution systems integrated with Photovoltaic (PV) sources, batteries, and Super Capacitors (SCs) plays a vital role in ensuring stable and efficient energy flow. However, these systems often face drawbacks such as increased energy consumption due to inefficient control strategies, higher emissions from backup conventional sources during low PV output, and elevated operational costs from frequent battery cycling and system maintenance, despite efforts to improve efficiency and enhance renewable energy utilization. To overcome these drawbacks, this manuscript proposes an approach for optimal power management in a power distribution system with RES. The suggested method is the combination of both the Greater Cane Rat Algorithm (GrCRA) and Pre-Activated Convolution Residual and Triple Attention Mechanism Network (PCRTAM-Net), termed as the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net approach. The primary aim of the suggested method is to reduce energy consumption, emissions, and operational cost while maximizing efficiency and renewable energy utilization in an advanced power distribution system. GrCRA optimizes the allocation and scheduling of power resources in advanced power distribution systems. PCRTAM-Net predicts future power demand and renewable energy generation patterns to support optimal power management. Flow Direction Algorithm-Convolutional Neural Network (FDA-CNN), Hippopotamus Optimization Algorithm (HOA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Spider Wasp Optimizer, and Multi-scale Hypergraph-based Feature Alignment Network (SWO-MHFAN), Golden Jackal Optimization-Progressive Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (GJO-PCGAN) are some of the existing techniques that are compared with the suggested method once it is implemented in MATLAB. An 18.7% overall energy reduction compared to the current methods has been achieved by GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net, which also attained an operational cost of 1505 cents, an emission level of 60.3 ppm, an efficiency of 99.1%, and a reduction in overall energy consumption. This further validates that the hybrid method effectively performed power flow optimization and stability enhancement in power distribution networks with renewable integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy from RESs, including solar, wind, and small-scale hydro turbines, has greatly transformed advanced power systems1. Adding these distributed energy resources to the grid creates uncertainty and problems for the traditional type of power flow approach. To meet the needs of decentralized energy, the power grid should be updated with smarter and more flexible technology2,3,4. Problems associated with voltage regulation, frequency, and load in the system must be addressed as renewable sources become a larger part of the grid5. Grids that used to power areas mainly in one direction are now replacing those models with grids that move power back and forth6. By combining batteries and SC in a Hybrid Energy Storage System (HESS), the technology can manage problems related to long- and short-term fluctuations in the grid7. HESS has the benefit of meeting the requirements for energy density and power density, making energy storage more adaptable to the changing renewable energy supply. The operation of distributed generation has to be combined with utilities to maintain a safe routine and avoid overloading the network8,9. When integration occurs, customers are able to play their part in maintaining a stable system by changing how they consume energy. Improved monitoring and ways to communicate make these systems more effective when making decisions and managing operations10,11. Advanced power systems play a key role in helping the world move toward cleaner energy as attention on decarbonization increases. Changing renewable sources of energy need to be handled to ensure the reliability of the power grid12. Good power management ensures conventional and renewable energies work side by side, helping the grid remain stable. Nowadays, distribution systems rely on strong protection systems to handle the risk of reversed power and find faults13. Furthermore, applying energy-saving solutions helps to cut down on power wasted in transferring energy and makes the company’s assets more productive14. Power management is essential for ensuring that power systems using renewables and advanced batteries remain reliable and sustainable15.

Literature survey

Using various methods and strategies, several research papers have focused on power management in power distribution systems integrated with RES. The following is a review of those works.

Lakshmi and Premalatha16 have presented an efficient way of distributing power with an FDA-CNN designed for DC/AC Microgrids (MGs) that also connect Electric Vehicles (EVs). Based on historical data, this technique takes advantage of the predictive abilities of CNN and the FDA to help control how much power was supplied, keeping things like how much electricity people use, how much electricity was being made, and the need to charge electric vehicles in mind. The technique helps manage how power was used and makes charging and discharging EVs more efficient by letting the system change based on what was happening with the grid, so power can be shared between DC and AC parts of the setup.

Maurya et al.17 have introduced an optimization technique that uses the HOA to concurrently determine the best location for Distributed Generation (DG) and carry out network reconfiguration in order to increase the efficiency of radial distribution networks. To appropriately represent load behavior, the technique uses voltage-dependent load models, such as constant power, constant current, constant impedance, and composite kinds. HOA was used to optimize a weighted multi-objective function that incorporates bus voltage variation and active and reactive power losses, drawing inspiration from the behavioral methods of hippopotamuses.

Jouil et al.18 have presented a control model for a PV-based renewable energy system combined with battery and SC energy storage in a DC Microgrid (MG) utilizing a hierarchical strategy that integrates sliding-mode control and Lyapunov stability theory. While a neural network was utilized to ascertain the maximum power defects for the PV system, the Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC)-based Energy Management (EM) framework was utilized to coordinate power distribution between generation and load. Under dynamic circumstances, the MG’s stable and effective operation was guaranteed by the hierarchical control system.

Abu et al.19 have presented a PSO-based approach to help optimize the performance of a Hybrid Energy System (HES) by grouping solar panels, hydrogen Fuel Cells (FCs), batteries, and SCs to better manage energy and use less hydrogen. To efficiently manage the way HES parts work together, the Proportional-Integral (PI) controller was tuned using PSO, making sure things like fuel flow, hydrogen consumption, and system stability were all kept in check. This strategy helps local areas become less dependent on the grid, makes better use of stored energy and renewables, and keeps the energy balancing within the area.

Alzahrani et al.20 have introduced a multi-objective optimization model for energy managers in power systems that relied on a Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA) to address choosing the lowest pollution, reduced operating expenses, and reduced Loss of Load Expectation (LOLE). It also includes solar and wind energy, which change at random, and they were described by using a beta probability density function. Balanced decision-making for a well-operated, secure, and stable power system can be achieved by considering many goals at the same time. Sithambaram et al.21 have presented that the use of SWO-MHFAN combined with the SO technique for better EM in grid-connected PV-powered electric vehicle (EV) charging stations. MHFAN was responsible for estimating the rate of energy demand and solar production, and SWO manages the exchange of power to optimize efficiency. The purpose of a grid-connected setup was to smooth how PV-generated electricity was used for charging EVs by improving the quality and consistency of their output.

Chiluka and Sekhar22 have introduced a method to optimize both the power quality and voltage output of hybrid RESs through the use of a Doubly Fed Induction Generator (DFIG), a Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) rectifier under PI control for wind energy conversion, and an Improved Z Source Converter with a Bird Swarm-Optimized PI controller for PV systems. A bidirectional battery converter managed the energy storage, and the energy was delivered as clean AC current using a three-phase Voltage Source Inverter (VSI) with an LC filter. Support for grid synchronization, high-quality DC-AC conversion, and reduced harmonic distortion allowed for more stable and sustainable power distribution. Rangasamy et al.23 have introduced that the GJO-PCGAN system was a combined energy approach for many MGs involving EV charging. Here, PCGAN predicts the ideal EV control strategy, and GJO finds the optimal times for charging and discharging, helping lower carbon emissions, costs, and power losses during transmission. To guarantee dependable EM throughout the MGs, the strategy incorporates RESs such as FCs, wind turbines, and PVs, with diesel engines added when needed.

Recent research has highlighted diverse strategies for optimization and control in renewable-integrated distribution systems. Abbas et al.24 developed a two-stage reactive power optimization technique that merges a traditional model-driven mixed-integer second-order cone programming (MISOCP) approach with a deep learning–based data-driven framework. Their method greatly enhances reactive power optimization and voltage stability by integrating day-ahead on-load tap changer (OLTC) scheduling and real-time control of renewable inverters in distribution networks using transformer networks.

In the same way, Ali et al.25 constructed a multi-objective, multi-period environmental economic power dispatch model that includes probabilistic wind and solar PV generation. Their model attains a robust balance among cost, emission, and voltage stability improvements, especially under uncertain renewable penetration, by using advanced multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (MOEAs) alongside reserve constraints.

In addition, Abbas et al.26 described a multi-objective, multi-period optimization system for the optimal placement and sizing of distributed generation (DG) units, alongside the restructuring of the distribution network. The system simultaneously minimized energy supply costs, energy losses, and voltage deviations using a bidirectional co-evolutionary algorithm (BiCo), which is an efficient approach in improving system reliability and efficiency.

In addition, another research by Ali et al.27 explored the integrated planning of distributed energy resources and battery energy storage with an improved large-scale multi-objective evolutionary algorithm. This study optimized the placement and sizing of generators as well as storage operations over time, thus achieving remarkable cost savings (up to 51.67%), emission reductions (up to 99.9%), and improvements in voltage profiles over multiple operating conditions.

The study by Ahmed et al.28 demonstrated the role of multi-objective optimization techniques in executing optimal operations in grids powered by renewable energy. It involves the integration of evolutionary computation, probabilistic modeling, and AI to holistically solve the problem of uncertainty, variability, and cost-effectiveness. The study shows that integrating renewable forecasting models with sophisticated optimization algorithms leads to stronger grid resilience, lower emissions, and better energy use. The intermittent system planning of power systems, made stable by the use of advanced algorithms, better accounts for PV and wind resources in the study.

All these focus areas underscore the importance of hybrid optimization, probabilistic modeling, and large-scale evolutionary methods in solving renewable integration, uncertainty handling, and multiperiod operational scheduling challenges. Using these insights, the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net method, proposed in this paper, combines evolutionary optimization with DL-based forecasting methods to enhance power management automation, minimize operational expenses, and increase the use of renewable energies in modern distribution systems. Comparison of selected existing studies on management of power in power distribution system with RESs is illustrated in Table 1.

From the analysis, it is evident that most of the existing literature failed to address the prediction of the system’s load while optimizing the participation of storage devices with EV and DG integration, their siting, converter control, and multi-objective optimization. The proposed GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net addresses these issues by employing bio-inspired optimization with deep learning forecasting, attaining 99.1% efficiency, 60.3 ppm emission reduction, and 1505 cents lower operational cost.

Research gap and motivation

Although diverse methods such as FDA-CNN, HOA, hierarchical sliding-mode control with Lyapunov theory, PSO-tuned PI controllers, NSGA, SWO-MHFAN, Bird Swarm-Optimized PI controllers, and GJO-PCGAN have been introduced for power management in distribution systems with integrated RESs, several limitations persist. FDA-CNN and SWO-MHFAN emphasize prediction and control in DC/AC MGs and EV charging coordination but give limited consideration to minimizing emissions and long-term operational sustainability. HOA and NSGA address optimization of distributed generation placement and EM using multi-objective strategies, yet the trade-offs between voltage variations, active/reactive losses, emissions, and cost remain insufficiently addressed under high renewable penetration. Techniques based on hierarchical control and FLC support system stability, but do not fully capture the dynamic interactions among batteries, SCs, PV, wind, and FCs during fluctuating demand and generation conditions. PSO-based tuning of PI controllers improves short-term performance in hybrid energy systems, but scalability and fuel optimization under resource uncertainty are not comprehensively treated. The Bird Swarm-Optimized PI controller and the GJO-PCGAN hybrid method integrate advanced converters and scheduling mechanisms but fall short in unified handling of emission control, energy efficiency, and low-cost operation. These gaps highlight a clear motivation to enhance emission reduction, improve energy utilization efficiency, reduce fuel and operational costs, and maintain power quality under renewable uncertainty and multi-source integration.

Research novelty and contributions

The integration of a new bio-inspired optimization algorithm with an advanced DL framework for intelligent power management in renewable integrated distribution systems is the novelty of this research. Proposing the GrCRA for optimal scheduling and the PCRTAM-Net for predictive intelligence has set a new standard for optimizing systems. The proposed methodology demonstrates significant advanced power management techniques in comparison with existing models that depend on traditional metaheuristics or separately constructed forecasting networks.

The main contributions of this work are highlighted in the following:

-

Unified Set of AI Optimization Methods: A decisive efficiency and the novel integration of distinct methods like GrCRA and PCRTAM-Net (GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net) is developed, allowing GrCRA to perform optimal scheduling of resources while PCRTAM-Net accurately predicts the load and generation power.

-

Improved Forecasting Accuracy: The proposed PCRTAM-Net employs pre-activated residual blocks and a triple attention mechanism (channel–spatial–dilated convolutional attention) to capture spatio-temporal dependencies in renewable and load data, significantly improving prediction reliability in comparison with CNN or RNN-based models.

-

Enhanced Optimization Functionality: The integration of the newly customized GrCRA as a meta-heuristic accomplishes the exploration versus exploitation tradeoff better by modeling the social foraging of greater cane rats. This newly adapted GrCRA performs better than the existing optimizers (PSO, HOA, SWO, GJO, etc.) for resource allocation problems in escaping local optima and converging faster.

-

Performance Improvements for Multiple Objectives: The framework optimizes the operational cost (1505 cents), emission (60.3 ppm), and energy consumption, in addition to reaching an efficiency of 99.1%. This performance exceeds that of the latest approaches like FDA-CNN, HOA, SWO-MHFAN, and GJO-PCGAN.

-

Applicability: In contrast to previous approaches based on separate systems, this research confirms the framework on a MATLAB renewable-integrated distribution system incorporating PV, battery, and supercapacitor, revealing its applicability to actual grid systems.

The remaining sections of the manuscript includes: the configuration of RES combined with the power distribution system is described in part 2. Part 3 explains the cost minimization of the RESs integrated power distribution system based on the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net technique. Part 4 explains the results and discussion. Part 5 concludes the paper.

Configuration of RES integrated with power distribution system

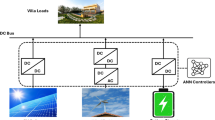

Figure 1 illustrates the structure of a RES integrated power distribution system that combines solar PV, battery storage, and SC units for efficient EM. The solar PV section includes a capacitor C1, inductor L1, switch S1, and diode D1 to regulate and transfer energy to the common DC link29. The battery system is composed of a capacitor C2, an inductor L2, and a bidirectional converter using switches S2 and S3, enabling both charging and discharging operations. Similarly, the SC branch includes capacitor C3, inductor L3, and bidirectional switches S4 and S5 to handle rapid charge-discharge cycles, suitable for managing transient power demands30. All sources are connected to a common DC bus, which is stabilized by a DC-link capacitor CDC and connected to the load through switch S6, diode D2, inductor L4, and output capacitor C4. This coordinated architecture allows flexible and intelligent control of power flows from various energy sources, ensuring stable voltage at the load and optimal utilization of renewable and storage resources under dynamic operating conditions.

To improve the performance of PV–battery hybrid systems, battery cycling needs to be reduced, and hybrid systems should be operated reliably, which is dependent on battery charge status modelling (State of Charge – SoC) and SoC operating conditions. The latest research focuses on three main topics: (i) choosing the right battery model (equivalent circuit or electrochemical) that offers the best trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency, (ii) accurate online SoC estimation, and (iii) age-reduction through active charge-balancing and SoC-constrained control to prevent over-charging and deep-discharging. In practical BMS implementations, equivalent circuit models (first-order Thevenin or higher-order Thevenin variations) tend to be used due to their simplicity and ability to capture transient behaviour. These models are usually integrated with observers or data-driven estimators for reliable online SoC estimation. For instance, the authors suggest using first-order Thevenin models coupled with data-driven SoC estimators, as it lowers implementation complexity and yields satisfactory estimation accuracy.

In the context of SoC estimation, model-based observers like the EKF (Extended Kalman Filter), UKF (Unscented Kalman Filter), sigma-point KF, and Luenberger observers, as well as machine-learning methods such as BPNN (Backpropagation Neural Networks) and ANN (Artificial Neural Networks), have proven to be highly accurate, given the right training and parameter tuning. BPNN methods have been noted to achieve sub-1–3% RMSE in numerous PV-battery associative scenarios, whereas Kalman filter variants are known for their strong noise robustness and direct applicability to equivalent-circuit parameters. Recent studies show that combining the equivalent circuit model with a precise SoC estimator not only enhances SoC tracking but also allows the BMS to schedule charging and discharging actions in a manner that prolongs battery life31.

For series-connected cells, the deployment of active cell balancing along with SoC-aware control strategies is strongly advised: leveraging SoC estimation of individual cells, along with the control of bidirectional DC–DC converters or switched-capacitor/balancer circuits, permits the transfer of energy from higher-SoC cells to lower-SoC cells, which helps to decrease cell imbalance and eliminates the need for the weakest cell to drive the pack limits32.

Simulations and experiments show that active balancing, accurate per-cell SoC estimation, and simple operational rules (like keeping SoC within a window) mitigate the rate of ageing, improve the usable capacity, and decrease the RMSE of SoC estimates, whereas OCV/voltage-only schemes deteriorate it further. Considering these observations, this paper adopts the computationally light transient model, the first-order Thevenin model, uses a robust estimator, be it BPNN or an appropriate observer, for per-cell SoC tracking, assumes avoidance of dual end SoC over-charging and deep discharging with active balancing control for cells in series strings. These are the conditions and modelling assumptions required to implement reliable BMS actions, extend the battery life, and improve the overall PV–battery system efficiency33.

Modelling of battery

The quantity of batteries and their condition at any one time determine how much energy is produced and consumed34. Power generation surpasses load demand while the battery is charged. The provided Eq. (1) expresses the battery bank’s power availability at a given time.

Where, \(\:{e}_{EE}\left(T\right)\) denotes extra energy available from all the systems, \(\:{\eta\:}_{cc}\) denotes the efficiency of the charging controller, \(\:{\eta\:}_{Charging}\) denotes battery charging efficiency.

The SoC of the battery is expressed by the given Eqs. (2),

Where, \(\:So{C}_{Min}\) denotes the value of the minimum SoC, \(\:So{C}_{Max}\) denotes the value of the maximum SoC is assumed as 1.

The following Eq. (3) is used to determine the minimum value of SoC.

Where, \(\:DoD\) denotes depth of discharge.

Modelling of SC

SCs are among the newest advancements in power storage technology, especially in integrated systems35. In this setup, the capacitance \(\:\left({c}_{supercapacitor}\right)\) was connected to the analogous series resistance\(\:\left({r}_{supercapacitor}\right)\). The voltage of SC \(\:\left({v}_{supercapacitor}\right)\) as a function of the SC current \(\:\left({i}_{supercapacitor}\right)\) was computed by applying the following Eqn:

Where, \(\:{q}_{supercapacitor}\) indicates the electricity exists in the cell.

The power of SC \(\:{p}_{supercapacitor}\) is computed by applying Eq. (5).

Modelling of PV

Solar PV energy has emerged as one of the most common RESs in current times. The PV cell functions as an electric current generator, which functions like a switched current source using a diode’s operation36. A p-n junction forms the diode. Two parallel and series intrinsic resistors \(\:{r}_{ip}\) and\(\:{r}_{is}\), have been incorporated within the model to study the physical processes at the cell level.

Consequently, Eqs. (6)-(8) can be used to model the solar cell in relation to the photocurrent\(\:{i}_{PH}\), the current \(\:{i}_{D}\) through the diodes, and the leakage current\(\:{i}_{SH}\). Additionally, a cell’s electrical properties are slightly different from a diode. Consequently, the Shockley equation is used to represent\(\:{i}_{D}\), as illustrated below:

Where \(\:n\) denotes the ideality factor of the diode, which is between 1 and 2, \(\:{r}_{s}\) denotes cell intrinsic series resistance, \(\:{i}_{SC}\) denotes the diode’s saturation current.

The following is the leakage current \(\:{i}_{SH}\) that the parallel resistance \(\:{r}_{p}\) causes:

Where, \(\:{r}_{p}\) denotes cell intrinsic parallel resistance.

The following is a statement of the net current \(\:{i}_{Photovoltaic}\) that the cell supplies:

Where, \(\:{i}_{PH}\) denotes photocurrent in shunt.

Therefore, the above controlling equation can be expressed as follows by substituting \(\:{i}_{D}\) for \(\:{i}_{PH}\) and using their expressions:

With

Where, \(\:Q\)indicates electron charge, \(\:K\) indicates the Boltzmann constant, \(\:T\) indicates the junction’s operating temperature.

A collection of basic PV cells coupled in parallel or series makes up a PV generator. Consequently, the following Eq. (11) defines the current provided by the PV panels as the number of cells function in parallel \(\:{N}_{p}\) and series\(\:{N}_{s}\):

Power converter modelling

A converter should be able to carry the maximum predictable power of loads (\(\:Powe{r}_{Load}^{Max}\))37. Consequently, the inverter rated power (\(\:Powe{r}_{inv}\)) is estimated in terms of the inverter efficiency (\(\:{\eta\:}_{inv}\)) as:

Cost minimization of RESs integrated power distribution system based on GrCRA-PCRTAM-net technique

Efficient power management and operation of RES-integrated power distribution systems are discussed in this research through the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net model. GrCRA optimizes power allocation and scheduling to ensure balanced energy flow and effective utilization of renewable sources, while PCRTAM-Net forecasts future power demand and renewable generation using advanced feature extraction and attention mechanisms, enabling precise and adaptive energy distribution for reliable and sustainable system operation. Figure 2 depicts the workflow of the proposed GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net methodology in the scope of power management in renewable-integrated distribution systems. The methodology starts with data inputs such as load, PV, battery, and SC. The subsequent forecasting of future demand and renewable generation is carried out through PCRTAM-Net. In turn, GrCRA uses the predictions to streamline optimization via exploration and exploitation methods that focus on minimizing cost and emissions and maximizing efficiency. To maintain dependable storage and operation, appropriate battery SoC and SC constraints are implemented. The scheduling strategy is then determined and implemented for the BESS, PV, SC, and grid, and the performance metrics are assessed.

Optimization using GrCRA

GrCRA is a nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization technique modelled after the intelligent foraging behavior of Greater Cane Rats (GrCRs)38. These rodents exhibit nocturnal and social behaviors, where a dominant male guides the group using knowledge of trails connected to essential resources. GrCRA replicates this behavior through two key phases: exploration, representing dispersed foraging from multiple shelters, and exploitation, symbolizing focused foraging in resource-rich areas during mating periods. These behaviors are translated into mathematical operators that enable efficient search dynamics. In the context of advanced power distribution systems, GrCRA optimizes the allocation and scheduling of power resources by balancing global exploration and local exploitation, leading to improved system performance, load balancing, and effective utilization of available renewable energy.

Step 1: Initialization.

Set up the input parameters such as PV, battery, and SC power, current, voltage, SC, and battery SoC, etc.

Step 2: Random Generation.

After initialization, random vectors are used to generate the input parameters at random.

Step 3: Fitness Calculation.

Fitness is influenced by the objective function. It is explained by,

Where, \(\:F\)denotes fitness function.

Step 4: Exploration Phase.

The GrCR construct their nests or small burrows in many locations throughout their area, which includes cultivated crop farms, riverbanks, and marshes. They either follow tracks to past food sources or search for a source of food before exploring the various shelters to forage.

The position of the dominant male establishes a new location for the remaining rat population in the search space, as demonstrated by Eq. (14). The fittest rat is updated in this stage of the GrCR motion simulation, and the positions of the other rats are modified in accordance with the newly determined fittest rat if the objective function value of another rat exceeds that of the fittest rat. Otherwise, it departs from the idea of the fittest rat. Equation (15) models the GrCR movement strategy. According to the exploration phase’s last step, the GrCR should only move to this newly determined location if the value of objective function at this new location improves; if not, it should stay in its original location.

Where, \(\:{Z}_{j}\) denotes the new state of \(\:j\)th GrCR, \(\:{z}_{j,k}^{NEW}\) denotes its value in the \(\:k\)th dimension, \(\:{z}_{j,k}\) denotes the position of the existing GrCR, \(\:{z}_{i,k}\) denotes the dominant male in the \(\:k\)th dimensions, \(\:R\) denotes a number randomly defined in the borders of the problem space, \(\:c\) denotes the impact of a plentiful food source, \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) indicate parameters.

Step 5: Exploitation phase.

The breeding season typically takes place during the wet season, though it varies depending on the habitat. During breeding season, males have been observed to dissociate themselves from the group. After the group is split off, it is considered that the foraging behaviours will target in places with a lot of food. To begin the phase simulation, a female \(\:m\) is chosen at random so that \(\:m\ne\:i\) (the dominant male). The intensification happens around the chosen female because breeding takes place near plentiful food supplies.

The modeling of the process is shown in Eq. (16). The newly calculated position for the GrCR replaces the previous position if it improves the value of the target function, as depicted in Eq. (15).

Where, location of a chosen female in the \(\:k\)th dimension randomly was indicated by \(\:{z}_{m,k}\), and the count of young generated by all the females GrCR/yr was simulated by \(\:\mu\:\), which randomly selects values between 1 and 4.

Step 6: Termination.

If the best solution is identified after reviewing the stopping criteria, the process ends; if not, proceed to step 3. The flowchart of GrCRA is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 represents the sequence of activities for setting the power optimization for a renewable integrated distribution system. The process starts with initialization, which in this case is procedures of generating a population of candidate solutions representing scheduling and allocation strategies that are randomly generated within the feasible limits of system variables such as power outputs, storage states, and load demands. The next step is fitness evaluation, which measures the quality of each candidate solution with respect to the multi-objective criteria — minimizing operational cost and emissions while maximizing system efficiency and renewable utilization. The exploration phase updates the candidate positions by simulating the random foraging and movement of cane rats. This allows the algorithm to broadly explore the solution space and helps in avoiding premature convergence. The subsequent exploitation phase deals with refining potential solutions by simulating localized movements and selective feeding of cane rats. This guarantees convergence to near-optimal resource allocation. Position updating rules (Eqs. 14–16) are iteratively applied during both exploration and exploitation to ensure a proper balance between global exploration and local exploitation. The algorithm then recalculates the fitness of the updated candidates and compares them with previously recorded best solutions. This iterative process repeats until a stopping criterion is reached, which is usually the maximum number of iterations or the convergence to a solution that is optimal. This solution ideally represents the optimal scheduling of power and resource allocation for the system. Based on this step-by-step procedure, the GrCRA effectively balances exploration and exploitation, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional optimizers such as PSO or HOA in handling local minima.

Prediction using PCRTAM-net

The PCRTAM-Net is a deep learning architecture developed to predict future demand of power and generation patterns of renewable energy, supporting management of optimal power in advanced distribution system39. It integrates pre-activated convolutional residual blocks, where normalization and activation precede convolution operations, enhancing gradient flow, training stability, and convergence. To improve the accuracy of prediction, PCRTAM-Net employs a triple attention mechanism consisting of channel, feature-wise, and temporal or positional attention modules. These modules collaboratively highlight the most relevant features of the input data across different abstraction levels. By combining residual learning with a hierarchical attention structure, PCRTAM-Net effectively captures complex patterns and temporal dependencies, enabling precise and adaptive forecasting necessary for reliable and efficient power management.

In a standard convolutional neural network, a block is defined by the convolution operation in Eq. (17):

Where \(\:x\) denotes the input feature map to the convolutional block, \(\:Con\left(x\right)\) denotes convolution operation applied to \(\:x\), \(\:BaNor\) denotes batch normalization, ReLU denotes rectified linear unit activation function.

However, in PCRTAM-Net, the pre-activated convolution residual block (Res-PDC) modifies this formulation by applying pre-activation (Batch Normalization followed by ReLU) before the convolution, and dropout is included for regularization. The output of the Res-PDC block with input \(\:x\) and transformation \(\:R\) is:

Where, \(\:R\left(x\right)=ReLU\left(BaNor\left(n\right)\left({c}_{2}\right)\right)\) denotes a sequence of operations.

To enhance spatial awareness, the Triple Attention Mechanism (TAM) introduces channel and spatial weighting. Given a feature tensor \(\:f\in\:{\mathfrak{R}}^{C\times\:H\times\:W}\), the Channel-Spatial Attention Module (CSAM) first computes the soft attention map:

Where, \(\:{e}_{z}\) denotes vertically extracted feature vector at location \(\:z\), \(\:{m}_{x}\) denotes horizontally extracted feature vector at location \(\:x\), \(\:Exp\left(\right)\) denotes exponential function for softmax calculation, \(\:n\) denotes total number of feature positions, \(\:{f}_{x}\) and \(\:{f}_{z}\) denote feature vectors from channels \(\:x\) and \(\:z\).

The Dual Convolution Block Attention Module (DCBAM) provides additional refinement through:

Where, \(\:\sigma\:\) denotes sigmoid activation, \(\:MLP\) denotes multilayer perceptron applied to the pooled features, \(\:avgpool\left(f\right)\) and \(\:maxpool\left(f\right)\) denotes global average and maximum values over the spatial dimensions of \(\:f\), \(\:{F}^{7\times\:7}\) denotes convolution with a 7 × 7 kernel.

Finally, the concatenated output from the Residual Atrous Convolution Spatial Pyramid (Res-ACSP) module, which includes dilated convolutions of various rates \(\:{D}_{j}\), is computed as:

Where, \(\:{z}_{1},{z}_{2},{z}_{3,}{z}_{4}\) denotes outputs from four parallel branches, \(\:cat\left(\right)\) denotes feature concatenation across channels, \(\:Conv\left(\right)\) denotes 1 × 1 convolution to merge the concatenated features.

Discussion on results

The performance of the suggested method is demonstrated in this section based on simulation results. In the operation of RES-integrated power distribution systems, the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net technique is suggested. This method optimally allocates power resources and schedules operations while accurately forecasting future power demand and renewable generation, ultimately enhancing energy distribution and system reliability. Implemented on the MATLAB platform, the method is described in detail and shows the capability to reduce energy consumption and emissions, maintain balanced power flow, increase renewable energy utilization, and enhance the overall efficiency and stability of power distribution system operations.

Table 2 presents the simulation parameters for the developed research model. The PV, battery, and SC capacities are indicative of typical microgrid installations, and the 30–80% SoC limits are aligned with the recommended ranges from battery ageing research. The one-minute time step and the residential–commercial load replicate demand. For the GrCRA algorithm, the population was set to 30, the generation count of 100, and for PCRTAM-Net hyper parameters, a learning rate of 0.001 managed to reduce the complexity of the optimization and ease convergence. The epoch count of 50 and batch size of 64 were decided from PCRTAM-Net’s hyper parameters and tested via cross-validation, which further increased the forecasting’s accuracy and robustness.

Figure 4 illustrates the evaluation of PV current. Initially, the current is 8.2 A approximately at 0 s and remains constant until about 1 s, where it drops sharply to around 6 A. A subsequent decrease is observed at 2 s, reducing the current to approximately 4 A. At 3 s, the current spikes slightly to about 6.2 A before declining again to 2.2 A at 4 s. It continues to drop to approximately 1.5 A at 5 s and finally reaches around 1.5 A at 5.5 s. This stepwise behavior suggests controlled changes in PV current output, likely due to varying irradiance levels or load conditions in the system being evaluated.

Figure 5 shows the evaluation of PV voltage. The voltage remains nearly constant at around 240 V throughout the duration, with brief and sharp drops occurring at specific intervals, notably near 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 s. During these instances, the voltage dips to 200 V before quickly returning to its normal level. These momentary fluctuations indicate transient disturbances, possibly due to changes in load or environmental conditions, while the overall stability suggests effective voltage regulation by the PV system.

Figure 6 illustrates the evaluation of PV power. Initially, the power output is about 1800 W at 0 s and remains steady until around 1 s, where it drops to approximately 1600 W. At 2 s, the power decreases further to around 1000 W. A rise is observed at 3 s, reaching nearly 1600 W again, followed by a drop to 800 W at 4 s. Finally, at 5 s, the power decreases to around 500 W and remains stable. These step changes reflect the dynamic behavior of the PV system, possibly influenced by changes in current and irradiance conditions, while maintaining efficient power regulation.

Figure 7 shows the evaluation of battery power. Initially, there are fluctuations between − 1000 W and + 1000 W during the first 0.1 s, indicating unstable charging and discharging activity. After this brief instability, the power stabilizes near 0 W until about 1 s. From there, the battery begins discharging, reaching approximately − 200 W. At 2 s, it returns to 0 W. Starting from 4 s, the battery begins charging, with power increasing to about 500 W, then to roughly 800 W at 5 s, and finally stabilizing at around 700 W by 5.5 s. This pattern reflects a transition from discharge to charge mode, supporting power balance in the system during varying load or generation conditions.

Figure 8 shows the evaluation of battery current. Initially, it discharges at − 2 A, then switches to charging at + 3 A around 1 s. The current rises to about + 4.5 A at 2 s, then drops to + 1 A by 3 s. Discharging resumes at − 1.8 A around 4 s. At 5 s, it charges again, peaking at + 6.5 A and settling near + 4.3 A. This reflects dynamic charge and discharge cycles.

Figure 9 illustrates the evaluation of battery voltage. The voltage rises rapidly from 0 V at the start to approximately 240 V within the first 0.2 s, then stabilizes and remains constant around 240 V for the rest of the time. This indicates a quick voltage build-up followed by steady operation, reflecting stable battery performance during the evaluated period.

Figure 10 presents the evaluation of battery SoC. Initially, the SoC is exactly 50%. It slightly increases to about 50.0001% by 1 s, and then gradually declines. At 3 s, it drops to around 49.9985%, followed by a small rise near 49.9987% at 4 s. A sharper decline is observed after 4 s, reaching approximately 49.9952% at 5 s, and stabilizing just below that. The minimal variation reflects fine-grained energy exchanges during short-term charging and discharging cycles.

Figure 11 shows the evaluation of SC power. The SC power starts near 100 W but quickly drops to about − 400 W within 0.2 s and remains there until 1.5 s. After that, it rises in stages, reaching approximately − 100 W, and then steadily increases to around 50 W by 3 s. At 4 s, the power peaks close to 200 W before falling back to about 75 W by 5 s. This pattern shows the SC’s quick response to power demands through rapid charging and discharging.

Figure 12 illustrates the evaluation of SC current. The SC current starts around 2 A but quickly drops to about − 1 A and stays steady at this level until 2 s. After 2 s, the current rises to near 0 A and remains stable until 4 s, when it jumps to approximately 1 A. Between 4 and 5 s, the current stays around 1 A before slightly decreasing to about 0.5 A by 5.5 s. This indicates the SC’s shifting role between charging and discharging during the period.

Figures 13 and 14 illustrate the evaluations of SC’s voltage and SoC. The SoC of the SC starts at approximately 96.4985% and gradually increases over time, reaching around 96.507% by 4 s. After peaking slightly, the SoC experiences a minor decline, settling near 96.505% at 5 s. This indicates a slight overall increase in the stored energy of the SC during the observed period.

Figure 15 illustrates the evaluation of load power. The power remains constant at 500 W throughout the entire period, indicating a stable load condition. This consistent performance suggests that the power management strategy effectively maintains a steady supply without fluctuations or interruptions, which is critical for ensuring reliability and stability in advanced power distribution systems integrated with RES.

Figure 16 presents the evaluation of load current. The current remains consistently around 2.5 A throughout the simulation, with minimal fluctuation. This steady current profile reflects the effective regulation of load conditions under the applied control strategy, ensuring reliable power delivery and system stability in advanced power distribution systems with renewable energy integration.

Figure 17 shows the evaluation of load voltage. The voltage remains consistently around 200 V throughout the entire period, indicating stable voltage regulation. This consistent voltage level confirms the robustness of the power management method in maintaining a steady voltage supply to the load, which is essential for ensuring the safe and efficient operation of power distribution systems with integrated RES.

Figure 18 shows the evaluation of the DC link voltage. The voltage rises quickly and stabilizes near 400 V shortly after startup, indicating a fast transient response. Brief voltage drops are observed at around 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 s, where the voltage dips to approximately 370 to 380 V due to possible switching actions or load variations. Despite these fluctuations, the system consistently returns to its steady-state level, demonstrating strong voltage regulation and effective control under varying conditions.

Table 3 presents a performance comparison between the suggested GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net method and several existing techniques, including FDA-CNN, PSO, HOA, SWO-MHFAN, and GJO-PCGAN, based on operational cost, efficiency, and emission. The GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net achieves the lowest operational cost of 1505 cents, outperforming FDA-CNN at 1544 cents, PSO at 1602 cents, HOA at 1578 cents, SWO-MHFAN at 1532 cents, and GJO-PCGAN at 1511 cents. In terms of efficiency, GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net attains the highest value of 99.1%, followed by GJO-PCGAN at 98.6%, FDA-CNN at 98.5%, SWO-MHFAN at 97.3%, HOA at 96.9%, and PSO at 95.9%. When it comes to emissions, the method uses the lowest value of 60.3 ppm, which is much better than FDA-CNN’s 98.03 ppm, GJO-PCGAN’s 109.32 ppm, SWO-MHFAN’s 241.6 ppm, PSO’s 245.96 ppm, and HOA’s 367.5 ppm. It is clear from these results that the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net achieves better results, at a lower cost and using less electricity, when RES integration is possible.

Discussion

The suggested GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net technique demonstrates significant improvements in the operation of RES-integrated power distribution systems by enabling optimized power allocation, precise demand forecasting, and stable energy distribution. During the evaluation, the PV current starts at 8.2 A, dips to 6 A, and then further to 4 A, settling at 1.5 A. As a result of the load and light changes experienced. Similarly, most of the time, the PV voltage is held at 240 V, with brief drops to 200 V every 20 min, showing the system stabilizes and regulates its voltage efficiently. This PV power starts with 1800 W and behaves in steps, ending up only at 500 W, revealing the system responds well to fluctuations in the environment. Just before getting out of the initial 0.1 s, the battery’s power swings from − 1000 W to + 1000 W, then steadies around 0 W, and later helps in achieving stable charging by moving from − 200 W to the main charging state of 700 W. Battery current varies between − 2 A and + 6.5 A, showing controlled charge and discharge cycles. Battery voltage rises quickly to 240 V and remains stable, while SoC varies slightly from 50% to around 49.9952%, reflecting fine-tuned EM. Similarly, SC power initially drops from 100 W to − 400 W, then increases gradually to 200 W before declining to 75 W, with SC current ranging from 2 A to − 1 A and then increasing back to 0.5 A, showcasing fast responsiveness to load variations. The SC SoC increases slightly from 96.4985% to 96.507% and settles near 96.505%, confirming minimal yet effective energy buffering. Load power remains constant at 500 W, current at 2.5 A, and voltage at 200 V, indicating consistent and stable power delivery under the suggested control strategy. The DC link voltage quickly stabilizes at 400 V after startup, with transient dips to 370–380 V occurring periodically and recovering immediately, demonstrating robust voltage control. Compared to other methods, the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net achieves an operational cost of 1505 cents, which is lower than FDA-CNN at 1544, PSO at 1602, HOA at 1578, SWO-MHFAN at 1532, and GJO-PCGAN at 1511. It also delivers the highest efficiency at 99.1%, surpassing GJO-PCGAN at 98.6%, FDA-CNN at 98.5%, SWO-MHFAN at 97.3%, HOA at 96.9%, and PSO at 95.9%. In terms of emissions, it records the lowest output at 60.3 ppm, significantly outperforming FDA-CNN at 98.03, GJO-PCGAN at 109.32, SWO-MHFAN at 241.6, PSO at 245.96, and HOA at 367.5. These results confirm the method’s superior capability to minimize energy consumption and emissions while maximizing operational performance and stability in power distribution systems with integrated RES.

Conclusion

This manuscript presents an efficient method for intelligent control and management of optimal power in advanced power distribution system integrated with RES using the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net technique. An 18.7% overall energy reduction relative to the compared methods and system stability improvements under fluctuating renewable generation and load conditions have been achieved, along with an operational cost of 1505 cents, an emission level of 60.3 ppm, and an efficiency of 99.1%, all attained by the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net. It is clear from the simulations that the results of the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net model have been markedly improved compared to PSO, FDA-CNN, GJO-PCGAN, HOA, and SWO-MHFAN. In comparison, FDA-CNN achieves 98.5% efficiency with 98.03 ppm emissions and a cost of 1544 cents. Other existing methods, including PSO, HOA, GJO-PCGAN, and SWO-MHFAN, perform less effectively, with PSO showing the highest operational cost of 1602 cents and HOA, GJO-PCGAN exhibiting emission levels of 367.5 ppm and 109.32 ppm, respectively. These results confirm that the GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net technique substantially enhances efficiency, reduces emissions, and lowers operational cost in power distribution systems integrating RES.

Limitations

While the newly developed GrCRA-PCRTAM-Net model stands out for its remarkable performance metrics of 99.1% efficiency, emission rates of just 60.3 ppm, and operational costs of 1505 cents in simulations, there remain a few limitations, such as:

-

Simulation Environment: Performance metrics were recorded in controlled MATLAB settings, which assumed ideal conditions such as accurate predictions and perfect, noise-free communications. The model has yet to be tested under real-world perturbations such as sensor noise, communication latencies, cyber-attacks, and sudden grid failures.

-

Computational Complexity: Despite the improvements that GrCRA brings to the exploitation–exploration trade-off, combining it with PCRTAM-Net increases the computation cost slightly. This is not a concern for small-to-medium scale networks, but poses a problem for very large distribution networks, as it would impact real-time computation.

-

Hardware Validation: The model requires further testing on real microgrid testbeds as well as hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) simulations to ascertain its feasibility.

-

Battery Ageing and Degradation Models: As far as SoC constraints go, compliance is maintained; however, the model still lacks in accounting for detailed long-term battery health impacts resulting from electrochemical degradation and thermal effects.

Future works

Future work of this research can be focused on the following extensions:

-

Extending the developed model to handle real-time practical issues through robust control and stochastic optimization.

-

Creating lightweight versions of PCRTAM-Net for large-scale power distribution networks and IoT-enabled microgrids to ensure quick deployment.

-

Validating practical applicability through HIL testing and small-scale microgrid pilot testing.

-

Deploying sophisticated models for battery ageing, thermal, and safety to improve both short-term scheduling and long-term lifecycle cost.

-

Integration with demand-side management (DSM) and vehicle-to-grid (V2G) systems to further improve adaptability.

-

Examining cybersecurity protocols to protect the proposed framework from malicious attacks on data and communication.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Dai, X. et al. Advancing distributed AC optimal power flow for integrated transmission-distribution systems. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 12, 1210–1223 (2025). (2025).

Wu, C. et al. Optimal energy management for prosumers and power plants considering transmission congestion based on carbon emission flow. Appl. Energy. 377, 124488 (2025).

Qiao, J. et al. Optimization schedule strategy of active distribution network based on microgrid group and shared energy storage. Appl. Energy. 377, 124681 (2025).

Sezgin, M. E. & Gol, M. Distributed energy management and communication strategy for network of microgrids. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 238, 111079 (2025).

Qi, N., Huang, K., Fan, Z. & Xu, B. Long-term energy management for microgrid with hybrid hydrogen-battery energy storage: A prediction-free coordinated optimization framework. Appl. Energy. 377, 124485 (2025).

Baby, H., Jayakumar, J., Mathew, M., Hussien, M. G. & Kumar, N. M. Analysis of reactive power loadability and management of flexible alternating current transmission system devices in a distribution grid using Whale optimization algorithm. IET Renew. Power Gener. 19, e12661 (2025).

Agoundedemba, M., Kim, C. K., Kim, H. G., Nyenge, R. & Musila, N. Modelling and optimization of microgrid with combined genetic algorithm and model predictive control of PV/Wind/FC/battery energy systems. Energy Rep. 13, 238–255 (2025). 2025.

Lahyani, A., Abdelhedi, R., Ammari, A. C., Sari, A. & Venet, P. Reinforcement learning based adaptive power sharing of battery/supercapacitors hybrid storage in electric vehicles. Energy Sources A: Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 47, 2993–3014 (2025).

Kamarposhti, M. A. et al. Optimum operation management of microgrids with cost and environment pollution reduction approach considering uncertainty using multi-objective NSGAII algorithm. IET Renew. Power Gener. 19, e12579 (2025).

Soltani, Z., Khorsand, M. & Ma, S. Current-voltage unbalanced distribution AC optimal power flow for advanced distribution management system applications. IEEE Open. J. Ind. Appl. 5, 155–167 (2024).

Liang, H. & Pirouzi, S. Energy management system based on economic flexi-reliable operation for the smart distribution network including integrated energy system of hydrogen storage and renewable sources. Energy 293, 130745 (2024).

Yousri, D., Farag, H. E., Zeineldin, H. & El-Saadany, E. F. Integrated model for optimal energy management and demand response of microgrids considering hybrid hydrogen-battery storage systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 280, 116809 (2023).

Kumar, R. P. & Karthikeyan, G. A multi-objective optimization solution for distributed generation energy management in microgrids with hybrid energy sources and battery storage system. J. Energy Storage. 75, 109702 (2024).

Dey, B., Misra, S. & Marquez, F. P. G. Microgrid system energy management with demand response program for clean and economical operation. Appl. Energy. 334, 120717 (2023).

Sun, H., Cui, X. & Latifi, H. Optimal management of microgrid energy by considering demand side management plan and maintenance cost with developed particle swarm algorithm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 231, 110312 (2024).

Lakshmi, P. P. & Premalatha, L. Optimal power distribution in DC/AC microgrids with electric vehicles using flow direction algorithm tuned CNN. Energy Rep. 13, 196–216 (2025).

Maurya, P., Tiwari, P. & Pratap, A. Application of the hippopotamus optimization algorithm for distribution network reconfiguration with distributed generation considering different load models for enhancement of power system performance. Electr. Eng. 107, 3909–3946 (2025).

Jouili, K., Jouili, M., Mohammad, A., Babqi, A. J. & Belhadj, W. Neural network energy management-based nonlinear control of a DC micro-grid with integrating renewable energies. Energies 17, 3345 (2024).

Abu, S. M. et al. An effective optimization algorithm for hydrogen fuel cell-based hybrid energy system: A sustainable microgrid approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 98, 1341–1355 (2025).

Alzahrani, A. et al. A strategy for multi-objective energy optimization in smart grid considering renewable energy and batteries energy storage system. IEEE Access. 11, 33872–33886 (2023).

Sithambaram, M., Rajesh, P., Shajin, F. H. & Rajeswari, I. R. Grid-connected photovoltaic system powered electric vehicle charging station for energy management using hybrid method. J. Energy Storage. 108, 114828 (2025).

Chiluka, V. & Sekhar, G. G. Advanced energy management system: Z source converter integration and swarm-optimized control for enhanced performance in hybrid renewable energy systems. J Inst. Eng. (India): B, 3, 1–19 (2025).

Rangasamy, S., Prakash, S. A., Sakhare, N. N. & Kumar, U. A. Multiple microgrids with electric vehicle charging in a hybrid GJO-PCGAN approach for energy management. Electr. Eng. 107, 7523–7537 (2025).

Abbas, G., Zhi, W. & Ali, A. A two-stage reactive power optimization method for distribution networks based on a hybrid model and data‐driven approach. IET Renew. Power Gener. 18, 3967–3979 (2024).

Biswas, P. P., Suganthan, P. N., Qu, B. Y. & Gehan, A. J. Amaratunga. Multiobjective economic-environmental power dispatch with stochastic wind-solar-small hydro power. Energy 150 : 1039–1057. (2018).

Abbas, G., Wu, Z. & Ali, A. Multi-objective multi‐period optimal site and size of distributed generation along with network reconfiguration. IET Renew. Power Gener. 18, 3704–3730 (2024).

Behbahani, F., Mohammadi, B., Ahmadi & Caglar, R. Multi-objective multiverse optimization for optimal allocation of distributed energy resources: the optimal parallel processing schemes. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 231, 110298 (2024).

Ahmed, M. M. et al. A peer-to-peer blockchain based interconnected power system. Energy Rep. 7, 7890–7905 (2021).

Karthikeyan, N. & Jebaselvi, G. A. A bidirectional four-port DC–DC converter for grid-connected and isolated loads of hybrid renewable energy system using hybrid approach. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal. Process. 118, 467–487 (2024).

Samal, K. B., Pati, S. & Sharma, R. Power management using an improved EMS algorithm in a stand-alone hybrid PV-PEMFC microgrid with reduced converter count. Green Energy Intell. Transp 100302, 112–123 (2025).

Qays, M. O. et al. An intelligent controlling method for battery lifetime increment using state of charge Estimation in pv-battery hybrid system. Appl. Sci. 10, 8799 (2020).

Qays, O., Buswig, Y. & Anyi, M. Active cell balancing control method for series-connected lithium-ion battery. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 8, 2424–2430 (2019).

Ohirul Qays, M., Buswig, Y., Hossain, M. L. & Abu-Siada, A. Active charge balancing strategy using the state of charge Estimation technique for a PV-battery hybrid system. Energies 13, 3434 (2020).

Suresh, V., Muralidhar, M. & Kiranmayi, R. Modelling and optimization of an off-grid hybrid renewable energy system for electrification in rural areas. Energy Rep. 6, 594–604 (2020).

Mounica, V. & Obulesu, Y. P. Hybrid power management strategy with fuel cell, battery, and supercapacitor for fuel economy in hybrid electric vehicle application. Energies 15, 4185 (2022).

Mahjoub, S., Chrifi-Alaoui, L., Drid, S. & Derbel, N. Control and implementation of an energy management strategy for a PV–wind–battery microgrid based on an intelligent prediction algorithm of energy production. Energies 16, 1883 (2023).

Elnozahy, A. et al. Optimal economic and environmental indices for hybrid PV/wind-based battery storage system. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 16, 2847–2862 (2021).

Agushaka, J. O. et al. Greater cane rat algorithm (GCRA): A nature-inspired metaheuristic for optimization problems. Heliyon. 10, e31629 (2024). (2024).

Wang, H. D. et al. PCRTAM-Net: A novel pre-activated Convolution residual and triple attention mechanism network for retinal vessel segmentation. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 38, 567–581 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to Deanship of scientific research at King Khalid university, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through the Large research group program under Grant no: RGP 2/343/46..

Funding

The authors express their appreciation to Deanship of scientific research at King Khalid university, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through the Large research group program under Grant no: RGP 2/343/46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing—Review and Editing, S.A, M.A; Methodology, P.P, M.S.R; Formal analysis, M.S, A.M; Investigation and Supervision, J.K.B, H.H, A.Z.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arulkumar, S., Arif, M., Patro, P. et al. GrCRA PCRTAM net based hybrid approach for intelligent control and optimal power management in renewable integrated power distribution systems. Sci Rep 15, 39976 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23793-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23793-3