Abstract

This study investigates the mechanical and microstructural performance of hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete (HFRC) incorporating steel, glass, and polypropylene fibers in varying proportions to optimize crack control and structural durability. Experimental results indicate that the optimal HFRC mixes exhibit a significant enhancement in mechanical properties, with compressive strength increasing by approximately 20–25%, split tensile strength by around 30%, and flexural strength improvements reaching up to 35% compared to plain concrete. The modulus of elasticity similarly improved by 15–20%, contributing to enhanced stiffness and load-bearing capacity. Workability remained within acceptable limits, with slump reductions not exceeding 15% due to superplasticizer use. Scanning electron microscopy confirmed that fiber incorporation densifies the matrix and strengthens the interfacial transition zones, effectively mitigating micro- and macro-crack propagation. These findings demonstrate that carefully optimized hybrid fiber combinations can provide a durable, high-performance concrete solution suitable for demanding structural applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is a vital material in construction, widely used in structures such as buildings, bridges, dams, and tunnels1,2. It is a composite material made by mixing hydraulic cement, water, fine aggregates, and coarse aggregates. When combined, a chemical reaction between the cement and water leads to the formation of a hardened, stone-like substance. Despite its widespread use and superior compressive strength, conventional concrete has relatively low tensile strength, making it vulnerable to cracking, especially at early stages. These cracks typically originate in regions subjected to tensile stress and can gradually spread toward the compression zones of structural elements, potentially compromising the structural integrity and leading to eventual failure. Crack formation is not solely caused by external loads; drying shrinkage also induces micro-cracks, which, over time, expand and lead to concrete failure. Thus, the emergence and propagation of cracks are significant factors contributing to concrete failure.

The primary cause of concrete degradation is crack formation, which can be triggered by several factors, including shrinkage, static and dynamic loads, freezing and thawing cycles, and creep3,4,5. The size and depth of these cracks can facilitate the ingress of gases, liquids, and dissolved ions, particularly chloride ions, which accelerate the corrosion of reinforcing steel bars typically embedded in concrete6,7. This degradation poses serious safety risks to both the structure and human life. Early detection of cracks can significantly extend the service life of these structures and help reduce the environmental and social costs associated with their maintenance8.

Over the past two decades, Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) has been developed to assess the performance of concrete structures through systematic evaluations, monitoring, and diagnosis in response to various types of deformation9. SHM can be implemented using externally attachable sensors, embedded sensors, and self-sensing concretes10. Commonly used sensors for SHM include strain gauges11, accelerometers, extensometers12, piezoelectric sensors13, fiber optic sensors, and wireless sensors14,15. Despite their usefulness, these sensors face several challenges such as variable performance due to climate conditions, low accuracy, poor compatibility with concrete, short lifespan, limited durability, and installation complications12,16,17. To overcome these issues, researchers have developed self-sensing concretes18,19, which continuously monitor their own condition. These concretes can provide real-time feedback on various internal and external stimuli, including strain, stress, cracking, temperature, humidity, corrosion, and pH levels by generating electrical signals17,20. The advantage of self-sensing concretes lies in their ability to combine structural support with sensory performance, making them a preferred alternative to conventional sensors21,22.

To produce self-sensing concrete, various electrically conductive fillers such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon fibers, steel fibers, carbon black (CB), and nickel powder can be incorporated directly into the concrete during the mixing process23,24,25,26. For instance, Parvaneh et al. developed self-sensing concrete nanocomposites by incorporating CNTs into cement paste and concrete. These composites demonstrated measurable changes in electrical resistance under compressive stress, with a maximum resistance change of 8% observed for 1 wt% CNTs at a compressive stress of 6 MPa27. Le et al. studied the self-sensing properties of ultra-high-performance concretes (UHPCs) containing steel slag aggregates and steel fibers. Their findings showed that finer slag particles and a balanced slag-to-cement ratio resulted in the highest resistance change (FCR = 42.9%) and stress sensitivity (0.298%/MPa)28. However, the corrosion of steel fibers can negatively impact the sensory response. Replacing these fibers with stainless steel fibers could address this issue, but the high cost of such materials remains a challenge29.

In addition to directly adding conductive fillers to the concrete mix, these fillers can also be applied to the surface of reinforcing fibers used to strengthen concrete, making the fibers electrically conductive and providing self-sensing capabilities. For example, Guo et al. produced cement-based composites using polypropylene (PP) fibers with varying dosages of CB. The CB nanoparticles adhered to the PP fiber surfaces, enhancing both electrical conductivity and self-sensing performance. Promising sensing properties were observed for pre-peak flexural stress and crack mouth opening displacement with 1.0% and 1.5% CB9. Another study by Oh et al. focused on developing multifunctional polyethylene (PE) fibers for high-strength strain-hardening cementitious composites (HS-SHCC). These fibers were coated with silver nanoparticles using an electroless plating technique, and surface treatments, including dopamine and plasma, were applied to activate the fiber surfaces. The dopamine-activated, silver-coated PE fibers showed a significant reduction in bulk resistance by around 15%30, 31. This method not only results in self-sensing cementitious composites but also reduces costs compared to using large quantities of nanofillers in the mixing process32,33 and improves adhesion between the fibers and the surrounding concrete matrix.

Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) fibers, known for their exceptional tensile strength, high modulus of elasticity, and chemical/alkaline resistance, are widely used in cementitious composites34,35,36. However, these fibers are electrical insulators and lack active chemical groups on their surfaces37,38. A feasible solution for making these fibers electrically conductive is to modify their surfaces. Tannic acid (TA), a plant-based polyphenol, has gained attention for surface modification due to its numerous hydroxyl groups and lower cost compared to dopamine39,40,41. TA modification typically takes between 12 and 24 h for complete oxidative polymerization42,43. To expedite the process, strong oxidizing agents such as sodium periodate (SP) can be used44,45,46. Additionally, PE fibers can be made electrically conductive by applying carbon-based materials like CNTs. For instance, Tang et al. created UHMWPE/CNT composites with excellent electrical conductivity (49 S/m) and a low percolation threshold of 0.10 vol%47, 48.

The integration of fibers into concrete, known as Fiber Reinforced Concrete (FRC), represents a significant advancement in modern construction practices. Fibers are added to concrete mixtures to enhance its tensile and flexural performance. Rather than replacing cement, fibers work in conjunction with it, providing additional support to resist cracking and improving overall structural integrity. The fibers are typically distributed in a discontinuous and random manner throughout the cement matrix, resulting in a composite material. FRC is known for its enhanced strength and broader performance capabilities, making it suitable for a variety of construction applications. The fibers used in FRC include steel, glass, synthetic, and natural fibers2. The amount of fiber incorporated into the concrete mix is usually expressed as the fiber volume fraction (Vf), and fibers are characterized by their aspect ratio, which is the ratio of length to diameter. Most fibers used in FRC have a high aspect ratio, with length significantly greater than diameter, contributing to the material’s enhanced performance.

Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (FRC) is a composite material in which short, discrete fibers are uniformly distributed throughout the concrete matrix to improve its structural integrity. These fibers exhibit distinct physical and mechanical properties that enhance the performance of concrete under various loading conditions. According to ACI Committee 54449, FRC is defined as concrete made with hydraulic cements, fine and coarse aggregates, and discontinuous discrete fibers. A representative example of FRC is shown in Fig. 1. Commonly used fibers include steel, glass, and synthetic fibers, as illustrated in Fig. 2 (Cement and Concrete Institute50. The quantity of fibers incorporated into a concrete mix is generally expressed as the fiber volume fraction (Vf), defined as the percentage of fiber volume relative to the total volume of the composite. Fibers are further characterized by their aspect ratio, which is the ratio of their length to diameter. Typically, fibers are much longer than they are wide, giving them a high aspect ratio that enhances their crack-bridging capacity and effectiveness in reinforcing the cementitious matrix.

The aspect ratio of fibers is a critical factor influencing the performance of fiber-reinforced composites. Higher aspect ratios typically contribute to improved flexural strength and toughness of the cementitious matrix. However, excessively long fibers may result in clumping or poor dispersion, which adversely affects workability a concern noted in earlier studies. The selection of fiber type is governed by multiple parameters, including its functional role, density, elastic modulus, tensile strength, and aspect ratio. In concrete applications, fibers are primarily incorporated to control cracks induced by plastic and drying shrinkage, reduce bleeding, and lower permeability51. The overall objective of fiber inclusion is to enhance key properties such as impact resistance, bond strength, tensile strength, toughness, ductility, energy absorption capacity, and deformation characteristics, as emphasized by Faisal Fouad Wafa52.

Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (FRC) demonstrates superior performance compared to conventional plain concrete. Although incorporating fibers increases the initial construction costs, this expense is justified by the substantial enhancement in structural and durability characteristics, as observed in the study by Ioannis Balafas et al.53. The advantages of FRC including increased crack resistance, impact and fatigue resistance, durability, and design flexibility have contributed to its widespread adoption over the past two decades. Today, it is extensively employed in diverse applications such as highway and airport pavements, seismic-resistant buildings, tunnel linings, bridge deck overlays, and hydraulic engineering structures. The improved performance attributes, coupled with advancements in material technology, continue to drive the growing utilization of FRC in modern construction practices.

Problem statement

Hybrid Fiber Reinforced Concrete (HFRC) has become a vital material in modern construction due to its exceptional ability to enhance the strength, durability, and overall performance of concrete structures. By integrating multiple fiber types such as steel, synthetic, and glass fibers HFRC improves tensile and flexural strengths, thereby increasing resistance to cracking and shrinkage. The synergistic effect of fiber hybridization aids in crack control, enabling the concrete to better withstand various stressors and maintain structural integrity over time. The increased toughness and resilience of HFRC make it especially suitable for applications demanding high durability, providing superior resistance against impact loads and dynamic forces. Additionally, HFRC offers improved performance under extreme environmental conditions, reduces maintenance requirements, allows greater design flexibility, and contributes potential sustainability benefits, positioning it as a robust and reliable alternative to conventional concrete. This study aims to evaluate the workability and mechanical performance of HFRC, focusing on optimizing the combination of steel, glass, and polypropylene fibers. By systematically varying fiber proportions, the research seeks to identify mixtures that balance fresh concrete workability with enhancements in compressive, split tensile, and flexural strengths. This tailored approach ensures the development of practical and high-performance HFRC mixtures suited for diverse structural applications, thereby advancing the optimization of hybrid fiber blends in concrete formulations.

Motivation for hybrid fiber reinforced concrete (HFRC)

The synergistic effect of combining multiple fiber types with contrasting elastic moduli in HFRC substantially enhances the mechanical performance and durability of the composite. High-modulus fibers such as steel and glass primarily inhibit the propagation of macrocracks, leveraging their superior stiffness and tensile strength to bridge wider cracks under load. This action significantly increases the toughness and load-bearing capacity of the concrete. Conversely, low-modulus fibers like polypropylene offer greater flexibility, playing a critical role in controlling the initiation and growth of microcracks, especially during early loading stages or due to shrinkage. Their contribution improves the ductility of the composite, delaying the transition from micro- to macrocracks, thereby boosting the material’s energy absorption capacity and resistance to brittle failure. The combination of these fibers in a hybrid system produces a complementary effect wherein low-modulus fibers enhance matrix cohesion and microcrack resistance, while high-modulus fibers provide macrocrack arrest and structural reinforcement. This dual mechanism results in a more durable, resilient concrete exhibiting increased tensile, flexural, and compressive strengths, as supported by recent experimental findings.

HFRC is an improved form of concrete which can be prepared using a different combination of fibers54. Figure 3 illustrates the incorporation of hybrid steel and polypropylene fibers into the concrete mix, a process termed hybridization. Recent studies (Xu and Hannant55; Kakemi and Hannant56; Mobasher and Li57 have demonstrated that hybridization, through the integration of two different fiber types within a cement matrix, can significantly enhance engineering properties. This improvement arises because the presence of one fiber type facilitates the effective utilization of the other fiber potential characteristics. Ganesan et al.58 noted that hybrid fibers in concrete effectively inhibit the development of both microcracks and macrocracks. Specifically, low-modulus fibers, such as polypropylene, efficiently control the initiation and propagation of microcracks, while high-modulus fibers, like steel, primarily restrict macrocrack propagation. Recent experimental research further confirms that steel fibers provide high stiffness and load-bearing capacity by bridging larger cracks, whereas polypropylene fibers improve ductility and toughness by delaying microcrack growth, resulting in a synergistic enhancement of concrete durability and mechanical performance.

There are two primary approaches to producing HFRC.

-

The first involves combining fibers of varying sizes and shapes to enhance packing density, which improves the stability and cohesiveness of the concrete mix.

-

The second approach consists of mixing fibers with different elastic moduli to achieve superior toughness across a broader range of crack widths.

By leveraging the complementary mechanical properties of diverse fibers, HFRC attains enhanced resistance to both micro- and macro-cracking, resulting in a more ductile and durable composite. These methods collectively optimize the fresh and hardened properties of HFRC, making it suitable for a wide array of demanding structural applications.

The primary purpose of the present research is to optimize the blending of multiple fiber types in concrete mixtures in order to enhance the mechanical behaviour and durability of the resulting concrete composite. Specifically, the study focuses on designing HFRC by combining fibers possessing contrasting elastic moduli incorporating both high-modulus fibers such as steel and glass, and low-modulus fibers such as polypropylene. This hybridization aims to leverage the complementary roles of different fibers where high-modulus fibers effectively restrain the propagation of macrocracks under applied loads, while low-modulus fibers are adept at controlling microcrack initiation and delaying crack coalescence. By carefully optimizing the proportions and combinations of these fibers, the research seeks to achieve an improved balance between workability, mechanical strength (including compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths), energy absorption, and overall durability.

The research investigates how varying dosages of fibers particularly combinations like 1% steel fiber with varying polypropylene fiber volumes or fixed glass fiber content with differing polypropylene fiber amounts affect fresh concrete properties (workability) and hardened properties (strength and modulus of elasticity). Through systematic experimental evaluation encompassing mechanical testing and microstructural characterization (including scanning electron microscopy), the study aims to identify fiber blend ratios that maximize crack control and structural performance without compromising constructability or cohesion of the mix. Ultimately, the goal is to develop HFRC mixtures that surpass conventional concrete and mono- fiber reinforced concretes in mechanical behaviour and durability, providing a cost-effective and engineering-efficient solution for enhanced structural applications where toughness and resistance to cracking are critical. This optimization contributes to advancing the understanding of fiber synergy in concrete and aids in formulating guidelines for effective hybrid fiber use in modern civil engineering practice.

Literature review

Song et al. investigated the mechanical properties of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete (SFRC) across varying fiber volume fractions of 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, and 2.0%. Their findings revealed that the maximum compressive strength was achieved at a 1.5% fiber content, exhibiting a 15.3% increase compared to plain concrete. Furthermore, both splitting tensile strength and modulus of rupture showed a consistent rise with increasing fiber volume, reaching remarkable improvements of 98.3% and 126.6%, respectively, at the highest volume fraction of 2.0%59. Soulioti et al. examined the influence of steel fiber geometry on the fresh and hardened properties of concrete by conducting slump tests on fresh mixes and compressive strength tests on hardened specimens. Their results highlighted the significant impact of fiber addition on both workability and strength. The inclusion of steel fibers reduced slump values by 65 to 90 mm compared to plain concrete, indicating a considerable decrease in workability. Meanwhile, compressive strength increased by 6.9% to 17.6%, with mixes containing waved steel fibers exhibiting superior strength compared to those reinforced with hooked-ended fibers60. Vikrant et al. investigated the effects of hook-ended steel fibers with different aspect ratios (50, 53.85, and 62.50) and incorporated crimped round steel fibers at volume fractions of 0% and 0.5%. Their results showed that the addition of 0.5% crimped round fibers led to approximately 17.7% and 32.7% increases in compressive strength and split tensile strength, respectively, compared to mixes with only hook-ended fibers61.

Sounthararajan et al. evaluated the effects of polypropylene fibers on concrete by varying fiber proportions from 0% to 0.3%. Their study revealed significant enhancement of tensile strength during both crack initiation and ultimate loading stages, particularly under flexural stresses. Notably, a fiber dosage of 0.1% consistently increased compressive strength by up to 7.92% at 7 days and 23.33% at 28 days, achieving compressive strengths of 44.25 MPa and 55.5 MPa, respectively. However, further increasing the fiber content beyond 0.1% led to a reduction in concrete strength and adversely affected workability. The study concluded that polypropylene fibers offer optimal mechanical benefits when incorporated at or below 0.1% volume fraction62. Shin Hwang and Hwang et al. investigated the impact resistance of Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete (PFRC) in comparison to Normal Strength Concrete (NSC) through drop weight impact tests combined with statistical analysis. Their results demonstrated that PFRC exhibited 1.1 times greater resistance at first crack and 1.2 times higher resistance at failure compared to NSC. Furthermore, the researchers developed predictive models for impact resistance, incorporating confidence intervals for failure strength, providing valuable tools for assessing the performance and reliability of PFRC under impact loads63.

Sawant et al. conducted an experimental investigation on high-strength Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete (SFRC) of M60 grade, focusing on the influence of steel fiber content ranging from 0.5% up to 5% by cement weight on workability and bond strength. Concrete cubes embedded with 16 mm deformed bars were tested to evaluate pull-out strength. The study observed a decrease in workability with increasing fiber content, a challenge effectively mitigated through the use of superplasticizers. An optimal fiber dosage of 1.5% by weight yielded the highest pull-out strength of 14.85 N/mm², representing a 22.62% increase over plain concrete. Failure in all specimens occurred through vertical cracking along the embedded bars, while no spalling was observed in fiber-reinforced samples; this behaviour was attributed to the enhanced toughness and crack resistance imparted by the steel fibers distributing stresses more evenly throughout the matrix64. Wu Yao et al. conducted a comparative study on the mechanical performance of concrete reinforced with carbon, steel, and polypropylene fibers. Among these, carbon fibers achieved the highest compressive strength, while polypropylene fibers resulted in the lowest. Hybrid combinations of carbon fibers with either steel or polypropylene fibers demonstrated significant improvements in overall mechanical behavior, indicating superior composite performance compared to single-fiber concrete65. Additionally, Qian et al. examined the flexural behaviour of hybrid steel-polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete prisms (100 × 100 × 500 mm) subjected to four-point bending tests. Their results revealed that the combination of larger steel fibers with polypropylene fibers enhanced both toughness and load-bearing capacity, highlighting the synergistic benefits of hybrid fiber systems66.

Sivakumar et al. experimentally evaluated high-strength concrete reinforced with hybrid fibers, combining hooked steel fibers with non-metallic fibers such as polypropylene, polyester, and glass at total volume fractions up to 0.5%. Their tests revealed that steel fibers mainly contributed to energy absorption capacity, while non-metallic fibers played a crucial role in delaying microcrack initiation and propagation. Among the hybrid combinations studied, steel-polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete exhibited superior mechanical performance compared to steel fiber reinforced concrete alone, demonstrating enhanced toughness and crack resistance67. Jain et al. investigated the mechanical effects of hybrid polypropylene and glass fibers in concrete by varying polypropylene fiber content from 0% to 0.45% and glass fiber content from 0% to 0.04%. Their results demonstrated that the inclusion of hybrid fibers significantly improved toughness and compressive strength, with optimal performance observed at 0.3% polypropylene and 0.04% glass fiber. Flexural strength also increased, reaching its peak at 0.45% polypropylene combined with 0.04% glass fiber. However, higher fiber dosages adversely affected the workability of the concrete mix, emphasizing the need for careful balance between mechanical enhancement and fresh concrete properties68.

Gaps identified in existing research motivating this experimental work

The motivation for this research stems from several identified gaps in the existing literature concerning HFRC. While prior studies have explored individual fiber types and some hybrid combinations, there remains limited comprehensive understanding of the optimal blending of steel, glass, and polypropylene fibers, particularly in terms of balancing mechanical performance and workability. Moreover, the synergistic interactions between fibers with contrasting elastic moduli where low-modulus fibers control microcracking and high-modulus fibers inhibit macrocrack propagation have not been fully examined, especially under varying dosage regimes. Additionally, the incorporation of fibers often leads to reduced workability, largely due to fiber entanglement and balling effects, yet detailed strategies to mitigate these challenges through admixtures like superplasticizers and optimized dispersion methods are insufficiently addressed. Furthermore, existing research offers limited insights into how hybrid fibers affect the microstructure of the concrete matrix and the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), both critical factors influencing durability and mechanical integrity. Finally, direct comparative assessments between hybrid mixes incorporating steel-polypropylene fibers and glass-polypropylene fibers, particularly with respect to long-term mechanical properties and microstructural developments, are sparse. These gaps underscore the need for systematic experimental investigations to optimize hybrid fiber combinations, understand their effects on fresh and hardened concrete properties, and develop practical guidelines for their application in structural concrete. This study, therefore, aims to fill these gaps by conducting a comprehensive evaluation of HFRC mixes with varied hybrid fiber proportions, assessing their workability, mechanical performance, and microstructural characteristics, thereby advancing the knowledge base and practical application of HFRC in civil engineering.

Materials and methods

Materials

This research utilized a range of materials, including Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) grade 53, fine and coarse aggregates, a superplasticizer, and fibers composed of steel, polypropylene, and glass. All concrete specimens prepared were of ordinary strength. The OPC 53 cement, conforming to IS 12,269 − 201569, exhibited key properties such as a specific gravity of 3.15, fineness of 309 m²/kg, consistency of 31%, initial setting time of 45 min, and a final setting time of 450 min. Detailed physical and chemical properties of the cement are presented in Table 1.

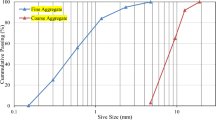

Manufactured sand, commonly known as M-sand, is produced by crushing natural rock to create fine aggregate that meets Indian Standards (IS) specifications. In this study, the fine aggregate was sourced from crushed rock to produce M-sand conforming to Zone-II grading as specified by IS: 383–201670. The particle size distribution of the M-sand ranges from 150 microns to 4.75 mm, complying with the required standards. A detailed summary of the physical properties of the M-sand utilized is provided in Table 2.

The recorded values conformed to the acceptable ranges specified in IS 383:201670. Additionally, the density values of the M-sand met the requirements outlined by relevant standards. It is important to emphasize that the M-sand used in this study complied with Zone-II grading and exhibited various fineness modulus values, all within the permissible limits. A comprehensive sieve analysis was conducted to accurately determine the particle size distribution of the aggregates, which revealed consistency in the shape characteristics of the M-sand samples. For detailed information on the percentage passing values and corresponding grading of the M-sand, please refer to Table 3.

The properties of aggregates, including their geometry, physical characteristics, and chemical composition, are largely influenced by their water absorption capacity. An excessive amount of water in the concrete mix can adversely affect its mechanical strength and durability, while insufficient water can lead to incomplete cement hydration. Therefore, it is critical to add the correct quantity of water in the mix design. The water absorption rates of the aggregates used in this study are summarized in Table 4.

The water absorption rate of the M-sand used in this study was within the acceptable limit of 2%, as specified by IS: 1124–197473. Coarse aggregates conforming to the requirements of IS: 383–201670 were employed. Their physical properties were evaluated following IS: 2386 − 1963 (Part III)72. The aggregates comprised well-graded, angular granite stones with a maximum size of 12.5 mm, fully meeting the prescribed standards. The measured specific gravity was 2.7, the fineness modulus was 7.2, and the water absorption rate was 0.62%. The concrete mix incorporated 60% of 20 mm aggregates and 40% of 12 mm aggregates. Comprehensive testing confirmed that the physical attributes of the aggregates complied with all relevant standards, as presented in Table 5. Detailed sieve analysis results are reported in Table 6.

The superplasticizer used in this study is a brown liquid formulated with specially processed lignosulphonate additives, allowing it to easily blend with water. In concrete construction, preventing water ingress through capillary pores is critical, as even well-constructed concrete exhibits inherent porosity. Water trapped within hardened concrete can lead to reinforcement corrosion, especially when moisture uptake occurs during freeze-thaw cycles. Additionally, if the infiltrating water carries aggressive dissolved salts, it may accelerate concrete deterioration. The Classic Crete Superflo-SP superplasticizer addresses these challenges by filling residual pores formed due to the slow evaporation of excess water not consumed in cement hydration. Furthermore, it introduces a controlled amount of air without increasing the admixture dosage, thereby reducing capillary suction by effectively blocking pore pathways. This combined action enhances the durability and longevity of concrete structures.

The plasticizing effect of the superplasticizer contributes to the production of a denser concrete mortar, significantly reducing its permeability. The commercially available Classic Crete Superflo-SP superplasticizer used in this study complies with IS: 2645 − 200371 standards. It features a specific gravity of 1.24, contains no chlorides, and has a solid content of 48%. The addition of superplasticizer improves concrete workability, as evidenced by increased slump values with higher dosages. Typically, superplasticizer dosages range from 0.20 to 0.32 L per 100 kg of cement. Table 7 summarizes the general properties of the superplasticizer employed, while Fig. 4 provides a visual representation of the admixture used in this experimental research. The improved dispersion of cement particles facilitated by the superplasticizer leads to reduced water content and a more compact microstructure, thereby enhancing concrete strength and durability.

This research employed a blend of three fiber types steel, glass, and polypropylene in an optimized hybrid combination. The fibers used are depicted in Fig. 5, with their mix proportions and characteristics provided in Tables 8 and 9. The study implemented fiber hybridization by combining fibers with both high and low elastic moduli to mitigate the development of microcracks and macrocracks. Low-modulus fibers primarily control microcrack formation and slow the growth of larger cracks, while high-modulus fibers effectively manage the propagation of macrocracks. Steel and glass fibers possess high elastic moduli, whereas polypropylene fibers exhibit a relatively low modulus.

-

Steel fibers were selected in a crimped form to enhance tensile strength and reduce crack widths, thereby improving concrete durability. Chopped strand glass fibers were incorporated to prevent early-age plastic shrinkage cracks and to enhance the mechanical behaviour of the concrete. Short-cut polypropylene fibers were included to increase flexibility, control crack development, and reduce water permeability in the concrete matrix.

-

This hybrid fiber approach leverages the complementary mechanical properties of each fiber type, resulting in a more ductile, crack-resistant, and durable composite material.

The following mix notations were used to identify the different concrete compositions:

Determination of fiber content in mix proportions

The content of fibers in the concrete mixture was calculated using the formula Mass of fibers = Vf × Vc × ρf, where Vf is the fiber volume fraction, Vc is the total volume of the concrete batch, and ρf is the density of the specific fiber. This calculation ensured an accurate and consistent addition of fibers by weight to the mix. The fiber density values were derived from their respective specific gravities and known physical properties. Fiber dosing was performed by weighing the calculated mass of fibers and incorporating them into the mix after the initial blending of cement and aggregates, allowing for uniform dispersion and minimizing fiber clustering. This approach facilitated precise control over fiber content in the hybrid mixes, optimizing the balance between mechanical performance enhancement and workability management.

Mix proportions

Mix design methodology following IS 10262:2019 guidelines

This study employed a concrete mix design targeting a cube compressive strength of 40 MPa, a commonly accepted grade in structural applications. The mix proportions were determined in accordance with the guidelines specified in IS: 10,262 − 201974. The designed mix contained 394.33 kg/m³ of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), 717.29 kg/m³ of fine aggregate, and 1152.59 kg/m³ of coarse aggregate, with a water-cement ratio maintained at 0.40 for the test specimens.

Fiber dosage selection

The chosen fiber dosages of 0.15%, 0.30%, and 0.45% by volume in this study are justified based on literature and common practice in fiber-reinforced concrete research. Research shows that low to moderate polypropylene fiber contents around 0.1% to 0.5% effectively enhance tensile and flexural properties without severely compromising workability or causing fiber balling. Dosages above approximately 0.45–0.5% often reduce compressive strength and workability due to fiber clustering and increased air content (Sounthararajan et al. 2013; Grzesiak et al. 2021; Pham et al. 2025; Askar et al. 2023). Using incremental steps such as 0.15%, 0.30%, and 0.45% ensures systematic evaluation to identify optimal performance while managing fresh concrete behaviour. Similar dosage ranges have been employed in prior experimental studies on hybrid fiber concrete mixes (Sivakumar et al. 2007; Jain et al. 2013), confirming their suitability. This study findings showing peak strength enhancements near 0.30% and reduced gains at 0.45% align well with existing literature, supporting the selected dosage levels for practical and effective mix design.

Sample preparation

Procedure for mixing, fiber incorporation, casting, compaction, and curing protocols

The required quantities of materials were precisely measured and thoroughly mixed using a mechanical mixer to prepare the concrete specimens. Mixing was conducted on a clean, water-tight platform constructed from an appropriately sized iron sheet capable of accommodating the entire concrete volume. Initially, sand was evenly distributed across the platform, followed by the addition and uniform spreading of cement. The materials were mixed manually with shovels until a consistent colour was achieved throughout the blend. Subsequently, coarse aggregate was added a top the sand-cement mixture. To ensure uniform fiber distribution and prevent clumping, fibers were introduced after the coarse aggregate and carefully dispersed during mixing. A central depression was created in the mixture where the required amount of water was gradually poured. Superplasticizer was incorporated to enhance the workability of the concrete. Mixing continued until the concrete exhibited a uniform colour and homogeneous fiber dispersion. The fresh fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) was then placed into molds and consolidated using a vibrating table to achieve proper compaction. After curing in the laboratory for 24 ± 3 h, the specimens were demolded and subsequently submerged in potable water until testing. Details of the cast specimens are provided in Table 10.

Workability refers to the ease with which concrete can be handled, transported, and placed into molds without significant loss of uniformity. The slump cone test, valued for its simplicity and reliability, is commonly employed to assess the workability of fresh concrete. This test is conducted according to the procedures specified in IS: 1199–195977. The apparatus used is a metal mold shaped as a truncated cone, measuring 300 mm in height, with a base diameter of 200 mm and a top diameter of 100 mm. The mold is positioned on a smooth, level surface and filled in three equal layers. Each layer is compacted by tamping 25 times using a standard 16 mm diameter steel rod with rounded ends. To ensure accurate results, the mold must be firmly held in place during filling, either by standing on footrests attached to the mold or by manual securing. Once the final layer is compacted, the mold is carefully and vertically lifted, allowing the unsupported concrete to settle or “slump.” The vertical displacement of the top surface of the slumped concrete, measured from the original height of the mold, is recorded as the slump value. Before lifting the mold, any spilled concrete around the base is cleared to ensure an unobstructed measurement. A uniform settlement of the concrete is termed a “true slump,” whereas uneven settlement, where one side collapses more than the other, is referred to as a “shear slump.” If the concrete collapses or shears laterally, which may produce unreliable results, the test is repeated using a new sample. Figure 6 illustrates the typical appearance of the test specimen.

The preparation of the designed mix during concrete mixing involved meticulous attention to material proportions and preparation to ensure a uniform and homogeneous blend. All materials including cement, manufactured sand (M-sand), and coarse aggregates were first dried in trays to eliminate moisture and break up any lumps in the cement or damp patches in the sand. After precise weighing, the dry ingredients were thoroughly mixed using a systematic dry mixing process to achieve uniformity. Coarse and fine aggregates were blended evenly with the cement until a consistent texture and colour were observed. Water was added in three stages: initially, 50% of the total mixing water was incorporated and mixed thoroughly with the dry blend. Subsequently, 40% of the water, along with the appropriate quantity of superplasticizer to improve workability, was added. Finally, the remaining 10% of water was introduced to ensure complete hydration and uniformity. Throughout the wet mixing process, a mechanical mixer was used to guarantee even distribution of all materials. Before casting, molds were cleaned and coated with oil to facilitate easy demolding. Once fresh concrete properties, such as slump and temperature, were evaluated, the concrete was promptly poured into the prepared molds. Compaction was performed using a vibrating table to eliminate air pockets and achieve proper densification. The concrete specimens were cured in water for a standard period of 28 days. Following curing, mechanical strength tests including compressive strength, split tensile strength, and flexural strength were conducted. The test specimens, as shown in Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10, were cast using standard steel molds in accordance with IS: 516–195975 and IS: 5816 − 199976 specifications.

Testing methods

The mechanical tests conducted on concrete are essential for evaluating its strength, durability, and overall performance. Compressive strength is determined through the cube test, which measures the concrete ability to resist axial loads. The splitting tensile strength is assessed using cylindrical specimens to determine the material resistance to tensile forces. Flexural strength is evaluated using a beam test under 2-point loading, which assesses the material behaviour under bending. The modulus of elasticity is measured using cylindrical specimens, providing an understanding of the concrete stiffness and deformation under stress. Workability is assessed using the slump cone test, which measures the ease with which the concrete mix can be placed and compacted. Finally, microstructural analysis is conducted through Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), which allows for detailed observation of the concrete internal structure at the microscopic level, helping to understand its composition and behaviour under various conditions. These tests collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of concrete mechanical properties and performance.

Compressive strength

The compressive strength evaluation was conducted in accordance with IS: 516–195975 to assess the strength of concrete cubes at 7 and 28 days of curing. Cube specimens measuring 150 × 150 × 150 mm were tested using a Compression Testing Machine (CTM) with a capacity of 2000 kN. The testing procedure was systematically followed to ensure accurate results. Figure 11 depicts the setup used for testing the concrete cubes for compressive strength.

Splitting tensile strength

The splitting tensile strength test was conducted on cylindrical concrete specimens with dimensions of 150 mm in diameter and 300 mm in length. The procedure followed the standards specified in IS: 5816 − 199976. The tensile strength was evaluated after curing the specimens for 7 and 28 days. Upon completion of the curing period, a continuous load was applied to each specimen at a rate between 1.2 N/mm²/min and 2.4 N/mm²/min until failure occurred. During testing, each cylinder split into two equal halves, confirming the tensile failure mode. The average splitting tensile strength was calculated and recorded. Figure 12 displays the testing setup used for assessing the splitting tensile strength of the concrete cylinder.

Flexural strength

The flexural strength test was conducted to evaluate the ability of concrete to resist bending under transverse loading. This test employed the two-point loading method as per the specifications in IS: 516–195975. Concrete prisms measuring 100 mm × 100 mm × 500 mm were tested after 7 and 28 days of curing. The test setup involved placing the specimen on two steel rollers, each with a diameter of 40 mm, spaced 400 mm apart from center to center. The load was applied using two additional rollers positioned at the third points of the span, spaced 133 mm apart. The load was gradually increased at a constant rate of 4 kN/min until the beam failed. The peak load at failure was recorded to determine the flexural strength of the specimen. Additionally, the failure patterns and fracture surfaces were examined and documented. Figure 13 shows the test setup used for evaluating the flexural strength of the concrete prism.

Modulus of elasticity

The modulus of elasticity of concrete refers to the ratio between applied stress and the resulting strain under load. To determine this property, a test was performed at 28 days following the guidelines outlined in IS: 516–195975. The specimens used for this test were concrete cylinders measuring 150 mm in diameter and 300 mm in height. The testing procedure was similar to that of the compressive strength test. Cylindrical specimens were subjected to gradually applied axial loads while measuring the corresponding deformations. The modulus of elasticity was then calculated based on the slope of the stress-strain curve obtained during the test. Figure 14 illustrates the experimental setup used for evaluating the elastic modulus of the concrete cylinders.

Microstructural analysis via scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

A Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) was used to observe microstructural changes in concrete containing polymer emulsion and steel fibers. The test aimed to understand how fibers bond with the cement matrix and how they influence strength development. Samples were carefully prepared by cleaning the cross-section to avoid interference from loose debris. SEM works by scanning the surface with a focused electron beam, generating secondary and backscattered electrons that reflect surface features. These signals are detected and converted into high-resolution images, showing details of the fiber–matrix interface. The analysis revealed improved bonding and structural integration, explaining the enhanced strength and crack control provided by the fibers.

Results

The experimental study involved a thorough evaluation that included workability assessments, compressive strength measurements, splitting tensile strength tests, flexural strength analyses, and modulus of elasticity determinations.

Workability results

Table 11; Fig. 15 present the slump values for various concrete mix proportions. Prior to adding the superplasticizer, slump values for all mixes ranged between 30 mm and 70 mm. The presence of fibers notably reduced the concrete fluidity, primarily due to fiber balling during mixing. Additionally, as the fiber volume fraction increased, the tendency for balling became more pronounced, resulting in decreased workability.

In Hybrid Steel-Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete (HSP-FRC), crimped steel fibers have a more pronounced impact on the workability of fresh concrete, whereas polypropylene fibers exhibit a lesser effect. Consequently, increasing the polypropylene fiber content in HSP-FRC causes only a slight change in slump values. In Hybrid Glass-Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete (HGP-FRC), the addition of 0.03% glass fibers leads to a significant reduction in slump. Moreover, as the polypropylene fiber dosage increases alongside glass fibers, the slump continues to decrease. Compared to HGP-FRC, workability is more severely affected in HSP-FRC, primarily because steel fibers reduce slump more than other fiber types, as steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) tends to clump together within the mix. Visual inspection and slump test results indicate that the incorporation of hybrid fibers reduces the workability of fresh concrete, which can be effectively improved by adding superplasticizer. A superplasticizer dosage of 5 ml per kg of cement was selected, based on the manufacturer’s recommended range of 500 to 1500 ml per 100 kg of cement. This dosage was applied to both plain concrete and hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete (HFRC) mixes to achieve the desired slump. After adding the superplasticizer, slump values ranged from 52 mm to 97 mm for all mixes, meeting the workability requirements for reinforced concrete beams as specified in IS: 456–200078, as illustrated in Fig. 15.

Workability of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete (HFRC)

-

Impact of steel and polypropylene fibers: Steel fibers have a more pronounced impact on the workability of concrete due to their stiffness. This causes clumping and decreases the fluidity of the mix. This is especially noticeable in Hybrid Steel-Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete (HSP-FRC), where adding steel fibers makes it harder to achieve the desired slump. On the other hand, Polypropylene fibers, being more flexible and lightweight, have a much smaller impact on the workability. Therefore, mixes like HSP-FRC tend to face greater challenges in terms of mix consistency than Hybrid Glass-Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete (HGP-FRC).

-

Superplasticizer for improved workability: The addition of a superplasticizer helps overcome these challenges. It significantly enhances workability, allowing for easier compaction and better fiber dispersion within the concrete. This results in a more workable mix with a slump that is within the standards required for reinforced concrete, ensuring the concrete can be effectively placed and compacted without segregation.

Mechanical properties

Compressive strength

Figure 16 illustrates the changes in compressive strength of concrete specimens containing hybrid fibers after curing in water for 7 and 28 days. An increase in compressive strength with curing time is observed across all mixes. At 28 days, every mix achieves a cube compressive strength exceeding 40 MPa, meeting the expected strength criteria. From the Table 12, At 7 days, Mix A0 demonstrated a compressive strength of 34.10 N/mm². Comparatively, Mix B1 exhibited a percentage increase of approximately 17.6% with a compressive strength of 40.10 N/mm², while Mix B2 showed the highest deviation with a percentage increase of around 24.0%, boasting a compressive strength of 42.30 N/mm². Mix B3 displayed a percentage increase of about 15.7%, reaching a compressive strength of 39.50 N/mm². On the other hand, Mix C1 showcased a percentage increase of nearly 9.96%, achieving a compressive strength of 37.50 N/mm², and Mix C2 demonstrated a percentage increase of approximately 14.7%, recording a compressive strength of 39.10 N/mm². Mix C3 exhibited the smallest percentage increase of about 7.97%, resulting in a compressive strength of 36.82 N/mm². These comparisons underscore the varying performance levels of the mixes concerning Mix A0 at the 7-day, reflecting the diverse characteristics and compositions of the concrete mixes under examination.

The Tabulated data illustrates the compressive strength (in N/mm²) of different concrete mixes at both 7 days and 28 days. At 28 days, the comparison of compressive strengths relative to Mix A0 reveals notable variations among the concrete mixes. Mix B1 exhibited a percentage difference of approximately 14.20%, indicating a considerable improvement in compressive strength compared to its 7-day performance. In contrast, Mix B2 demonstrated a higher percentage difference of around 19.00%, signifying a significant enhancement in strength over the curing period. Similarly, Mix B3 exhibited a percentage increase of about 12.85%, indicating significant improvement in compressive strength after 28 days of curing. Meanwhile, Mix C1 displayed a percentage difference of about 9.15%, reflecting a moderate increase in strength compared to its 7-day value. Mix C2 showcased a percentage difference of approximately 12.34%, indicating a notable improvement in compressive strength. Notably, Mix C3 exhibited the lowest percentage difference at approximately 7.29%, implying a relatively modest enhancement in strength at the 28-days. These observations underscore the diverse rates of strength development among the concrete mixes and highlight the significance of extended curing periods in achieving optimal compressive strength characteristics. Among the tested concrete mixes, Mix B2 demonstrated the greatest compressive strength at both 7 and 28 days. Specifically, at 7 days, Mix B2 recorded the highest compressive strength of 42.30 N/mm² compared to all other mixes. Furthermore, at 28 days, Mix B2 continued to demonstrate superior performance with a compressive strength of 54.62 N/mm², surpassing all other mixes in strength development. This indicates that Mix B2 had the highest strength achievements at both early and later stages of curing, making it the most strong and durable mix among those tested in this study. The compressive strength results shown in Fig. 16 indicate that HFRC outperformed plain concrete. This improvement is attributed to the fibers capacity to delay the initiation of microcracks and inhibit their growth within the concrete up to a certain extent.

Optimal mixes, Optimal mixes, Crack patterns, and Fiber reinforcement mechanism

The choice of best mixes (B2 and C2) can be justified using a clear performance index based on their superior mechanical properties, including compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and flexural strength. These mixes consistently exhibited the highest values across these critical parameters compared to all other mixes tested, underscoring their enhanced structural performance. A composite performance index such as a weighted sum or normalized aggregation of these strengths can provide quantitative backing for their selection as optimal mixes. Figure 17 illustrates the typical crack patterns and failure modes observed in the hybrid fiber reinforced concrete specimens for mixes B2 and C2.

The failure mode for both mixes transitions from brittle fracture, observed in plain concrete, to a more ductile and controlled crack propagation characterized by multiple fine cracks. The crack patterns reveal that fiber-bridging mechanisms were effective in delaying crack initiation and propagation, contributing to improved toughness and post-peak load resistance. The mechanism of fiber addition plays a pivotal role in enhancing concrete performance. In mix B2, the inclusion of high-modulus steel fibers provides substantial crack bridging capacity for macrocracks, effectively increasing load transfer across cracks and improving toughness. Polypropylene fibers complement this effect by controlling microcrack formation and enhancing the homogeneity of the cement matrix, thereby reducing crack widths and mitigating stress concentrations. In mix C2, the combination of glass fibers with polypropylene fibers contributes to enhanced cracking resistance primarily through controlling plastic shrinkage and microcracks, while also improving flexural behaviour. The synergistic interaction between fibers of different physical and mechanical properties results in multi-scale crack control low modulus fibers inhibit microcrack growth, and high modulus fibers resist macrocrack propagation leading to superior mechanical responses in hybrid fiber mixes. This multi-scale reinforcing mechanism explains the marked improvements in energy absorption capacity, ductility, and durability in the best-performing mixes, B2 and C2. Thus, the observed failure behaviours and crack morphologies substantiate the performance index-based selection and confirm the efficacy of hybrid fiber reinforcement in concrete matrix optimization.

Compressive strength enhancement

-

Hybrid fiber Influence: The addition of hybrid fibers, particularly the combination of steel and polypropylene fibers, leads to a noticeable improvement in compressive strength. In the case of Mix B2 (1% steel and 0.30% polypropylene fibers), the concrete demonstrated a 24.2% increase in compressive strength at 28 days compared to plain concrete (A0). Steel fibers contribute significantly to enhancing the concrete’s load-bearing capacity by restricting the development and growth of cracks.

-

Mechanism of strength enhancement: Steel fibers, due to their higher modulus of elasticity, provide additional reinforcement to resist tensile stresses within the concrete, which delays the formation of microcracks. Polypropylene fibers, being flexible, enhance the concrete’s ability to absorb stress and prevent the rapid expansion of small cracks. This synergy results in a concrete matrix that is more cohesive and capable of resisting compressive forces, particularly under dynamic or impact loading.

Splitting tensile strength

From the Table 13, At 7 days, the split tensile strengths of the various mixes compared to Mix A0 exhibit diverse trends. Mix B2 stands out with a substantial percentage difference of approximately 105.97%, indicating a significant increase in split tensile strength relative to Mix A0. Mix B1 also demonstrates notable improvement with a percentage difference of about 45.27%, while Mix B3 shows a moderate increase of approximately 36.32%. Among the C mixes, Mix C2 displays a moderate enhancement with a percentage difference of around 27.86%, followed by Mix C1 with approximately 17.41%. Mix C3 exhibits the smallest increase at about 13.93%, reflecting a comparatively modest improvement in split tensile strength at the 7-day mark.

At 28 days, the split tensile strength comparisons reveal further insights into the performance of the mixes relative to Mix A0. Mix B2 continues to lead with a notable percentage difference of about 89.93%, indicating substantial strengthening over the curing period. Mix B1 maintains its significant improvement with a percentage difference of approximately 49.66%, while Mix B3 exhibits a moderate increase of around 40.07%. Among the C mixes, Mix C2 demonstrates a moderate enhancement with a percentage difference of about 33.22%, followed by Mix C1 with approximately 20.13%. Mix C3 shows the smallest increase at approximately 12.08%, suggesting a relatively modest improvement in split tensile strength compared to Mix A0 at the 28-days. These observations underscore the dynamic nature of split tensile strength development and highlight the varying performance characteristics of the concrete mixes over time. In comparing the split tensile strengths of HSP-FRC (B series) and HGP-FRC (C series) mixes at 7 days, distinct trends emerge. Mix B2, classified as HSP-FRC, demonstrates a substantial percentage difference of approximately 60.94% compared to C2, an HGP-FRC mix. This indicates a significant disparity in split tensile strength between the two series at the 7-day mark, with the HSP-FRC exhibiting notably higher strength. Mixes B1 and B3 also display percentage differences of around 24.58% and 19.65%, respectively, compared to their HGP-FRC counterparts, C1 and C3. At 28 days, similar trends persist, emphasizing the disparity in split tensile strengths between the two series. Mix B2 continues to showcase a substantial percentage difference of approximately 42.21% compared to C2, indicating a sustained advantage in split tensile strength for HSP-FRC over HGP-FRC. Mixes B1 and B3 also maintain their relative strength advantages over C1 and C3, with percentage differences of approximately 24.58% and 24.85%, respectively. These findings highlight the distinct performance differences between HSP-FRC and HGP-FRC mixes regarding split tensile strength. HSP-FRC consistently exhibits higher strength than HGP-FRC at both 7 and 28 days of curing. Figure 18 illustrates the variation in split tensile strength for concrete specimens containing hybrid fibers. It is evident that incorporating hybrid fibers improves split tensile strength over time compared to the control concrete.

Split tensile strength improvement

-

Enhanced resistance to tension: Hybrid fiber concrete significantly improves split tensile strength. Mix B2, for example, showed a 106% increase in tensile strength at 7 days, continuing to perform strongly at 28 days. This performance is due to the combined actions of steel fibers, which control larger macrocracks, and polypropylene fibers, which help mitigate microcrack initiation.

-

Synergy between fiber types: Steel fibers are particularly effective in preventing crack propagation once they initiate, while polypropylene fibers reduce the rate at which microcracks form. Together, they form a comprehensive network that resists tensile stresses more efficiently than a single fiber type could alone. This enhanced resistance to tension is critical for preventing cracking in concrete structures that are subjected to dynamic loads or stress reversals.

Flexural strength

According to Table 14, the HSP-FRC mixes with volume fractions B1, B2, and B3 exhibit flexural strength increases of approximately 60%, 91%, and 51% at 7 days, and 44%, 84%, and 42% at 28 days, respectively, compared to the control concrete (A0). In contrast, the HGP-FRC mixes with volume fractions C1, C2, and C3 show flexural strength improvements of about 14%, 43%, and 9% at 7 days, and 18%, 40%, and 13% at 28 days, respectively, over the control concrete (A0).

The table displays the flexural strength values (in N/mm²) of different concrete mixes measured at 7 and 28 days. Among these, Mix B2 consistently achieves the highest flexural strength, with readings of 6.8 N/mm² at 7 days and 8.4 N/mm² at 28 days. Mixes B1 and B3 also show significant strength, recording 5.7 N/mm² and 6.6 N/mm² at 7 days, respectively. In contrast, Mix A0 has the lowest flexural strength at both intervals, reflecting its relatively weaker resistance to bending forces. Overall, the data indicates a general increase in flexural strength from 7 to 28 days across most mixes, demonstrating ongoing structural improvement. The inclusion of hybrid fibers clearly enhances flexural strength over time compared to the control concrete, as illustrated in Fig. 19, which depicts the variation in flexural strength of concrete specimens containing hybrid fibers.

Table 14 indicates that at lower dosages, polypropylene fibers (0.15% and 0.30%) do not adversely affect the concrete’s strength and may even enhance it. However, at a higher dosage of 0.45%, the strength declines due to the increased fiber content disrupting the concrete cohesion, primarily caused by the balling effect of the hybrid fibers. Among the mixes tested, B2 (containing 1% steel fibers and 0.30% polypropylene fibers) and C2 (with 0.03% glass fibers and 0.30% polypropylene fibers) demonstrated superior mechanical performance. At 28 days, the compressive, split tensile, and flexural strengths of mixes B2 and C2 improved by approximately 24.2%, 89.6%, and 84.4%, and 16%, 31%, and 40%, respectively, compared to the plain concrete (A0). Based on these results, B2 and C2 were selected as the optimal mixes for casting beam specimens. Additionally, previous studies confirm that fiber addition enhances the mechanical properties of hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete compared to plain concrete. It is also evident from Table 14 that B2 outperforms C2, which can be attributed to the higher tensile strength of steel fibers compared to glass fibers.

Flexural strength enhancement

-

Improved bending resistance: The addition of hybrid fibers enhances the concrete ability to resist bending forces. In Mix B2 (1% steel and 0.30% polypropylene fibers), there was a 91% increase in flexural strength at 7 days and an 84% increase at 28 days compared to plain concrete. Steel fibers are particularly effective in enhancing flexural strength by bridging cracks, which prevents further propagation under bending stress.

-

Role of polypropylene fibers: Polypropylene fibers enhance the flexibility of the mix, allowing it to deform under bending stresses without failing. This increases the concrete’s ductility and resistance to cracking, particularly at the early stages when concrete is most vulnerable to cracking under tension.

Modulus of elasticity

Table 15 presents the experimental values of the modulus of elasticity (Ec) at 28 days for all concrete mixes, alongside predictions based on the equations from IS: 456–200078 and BS: 8110 (Part 1) − 198579. The formulas provided by these standards for calculating the modulus of elasticity, which depend on the 28-day compressive strength of concrete, are shown in Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively.

Where,

‘Ec’ represents the modulus of elasticity of concrete measured in N/mm², while ‘fck ‘denotes the concrete cube compressive strength at 28 days, also expressed in N/mm².

Figure 20 shows that the 28-day modulus of elasticity (Ec) for the different proportions of HSP-FRC mixes (B1, B2, and B3) are 1.35, 1.42, and 1.31 times greater than that of the control concrete (A0). Similarly, the HGP-FRC mixes (C1, C2, and C3) exhibit Ec values that are 1.13, 1.17, and 1.11 times higher than the control. These results indicate that adding fibers to the cement matrix improves the concrete modulus of elasticity. Among the two fiber types, HSP-FRC shows a more pronounced increase in Ec compared to HGP-FRC, primarily due to the higher elastic modulus of steel fibers relative to glass fibers.

To compare the experimental results with the formulas provided in the IS and BS codes, the test data and code predictions are plotted in Fig. 21. It is observed that the BS: 8110 (Part 1) − 198579 tends to underestimate the modulus of elasticity (Ec), a finding that aligns with similar observations reported by Anbuvelan et al.80.

To enhance global applicability, a comparison with international codes (ASTM/ACI) for hybrid fiber reinforced concrete can be briefly included alongside IS standards.

Comparison of Key International Codes.

Mechanical Properties – Flexural, Tensile, Compressive strength

-

IS Standards: Specify mechanical property test methods (e.g., compressive, splitting tensile, flexural strength) and prescriptive formulas such as modulus of elasticity, typically derived from cube compressive strength.

-

ASTM

-

ASTM C1609/C1609M: Standard test for flexural performance of fiber-reinforced concrete using beam third-point loading.

-

ASTM C1116/C1116M: Specification for fiber-reinforced concrete materials, covering steel, glass, and synthetic macrofibers.

-

ASTM C469/C469M: Specifies the test procedure and calculation for static modulus of elasticity and Poisson’s ratio for concrete in compression using cylindrical specimens.

-

-

ACI

-

ACI 318: Fundamental mechanical property relationships, including tensile strength as 0.62fc′fc′ for reinforced concrete structures.

-

ACI 544 series: Reports and guides on design, testing, and specification for fiber-reinforced concrete, explicitly covering hybrid mixes (steel, glass, polymeric).

-

ACI 363 and ACI 318: Provide equations for modulus of elasticity estimation based on compressive strength but empirical, may over/underestimate at higher strength grades.

-

ACI 360R: Guide for slabs-on-ground incorporating FRC and toughness/energy absorption parameters.

-

-

ASTM/ACI prefer cylinder-based (diameter: height = 1:2) modulus measurements; IS uses cubes in most cases.

-

Neither ACI nor ASTM specify a minimum modulus, but provide unified approaches for stress–strain evaluation and test protocols for fibers (steel, glass, synthetics).

-

ASTM standards emphasize direct measurement, particularly initial linear portion, and are less sensitive to aggregate type or curing than empirical code equations.

Flexural performance and toughness

-

ASTM C1609/C1609M and ACI 544.4R use third-point loading to assess flexural toughness and post-crack residual strength, critical for FRC design beyond elastic range.

-

ASTM, ACI, and BS EN standards (EN 14651) provide comparable procedures for metallic and macro-synthetic fibers.

For global applicability, experimental procedures and results are compared with ASTM C1609 and C1116 (flexural/tensile/fiber specification), ACI 318 and 544 (mechanical and design recommendations), and IS: 456–200078 (modulus of elasticity and mix design). While IS standards express modulus and strength based on cubes and empirical equations, ASTM and ACI protocols favour direct stress–strain and flexural beam methods, frequently measured on cylinders. Including these comparisons allows robust benchmarking and enhances the relevance of hybrid fiber solutions for international engineering practice.

Microstructural analysis

-

SEM image interpretations of fiber-matrix interfaces

The mechanical properties of materials are closely tied to their microstructure. Concrete is a non-homogeneous material composed of three primary phases: the cementitious matrix, aggregates, and the Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) that exists between them. In fiber-reinforced concrete, the ITZ between the fibers and the cement paste is often identified as a structurally weaker region that significantly affects the composite overall mechanical performance (Li et al., 2013; Mobasher, 2014; Wang et al., 2016). To examine the microstructural behaviour and assess the quality of the ITZ, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed on four different groups of specimens. Each group featured varying combinations and volume fractions of steel, glass, and polypropylene fibers. The specific details for each mix (Mix-ID) are summarized in Table 11. In Mix A0, no fibers are present, while Mixes B1, B2, and B3 incorporate varying volumes of steel fibers along with polypropylene fibers. Conversely, Mixes C1, C2, and C3 combine glass fibers with polypropylene fibers at different ratios. This breakdown clarifies the composition of each concrete mix, aiding in precise selection based on specific project needs and performance criteria.

-

Structural characteristics of the Hybrid Fiber-Polymer concrete under electron microscopy

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed at a magnification of 500× to observe the microstructural characteristics of the concrete specimens. Figure 22 presents the cross-sectional SEM images, providing a comparative view of traditional plain concrete and hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer-modified concrete. The images reveal distinct differences in microstructure, highlighting the improved fiber dispersion and matrix bonding in the modified concrete.

A review of Fig. 22a and b reveals the presence of multiple microcracks and small surface voids in conventional concrete. In contrast, the hybrid fiber–polymer concrete exhibits a denser microstructure, where a polymer-enriched cementitious layer effectively fills many of the cracks and voids, leading to a more compact and refined internal structure. The hybrid mix also shows significantly fewer microvoids and fissures than its conventional counterpart, indicating improved bonding and potential enhancements in both mechanical strength and resistance to corrosion. Figure 22c illustrates the interface between a steel fiber and the surrounding concrete matrix. The fiber is partially embedded in a network of polymer-cement slurry formed by the interaction of polymer latex and cement, facilitating mechanical interlock. The degree of adhesion between the steel fiber and the polymer-cement paste is crucial for the overall performance of the hybrid composite. However, the image also suggests that the slurry does not fully envelop the steel fiber, resulting in limited contact between the fiber and the cement paste. This incomplete coverage can affect bond strength. To address this, future studies could focus on optimizing the mix design or enhancing paste workability to improve fiber-matrix interaction and maximize performance.

-

Microstructure of cement paste

The microstructure of cement paste refers to its microscopic arrangement, consisting mainly of hydrated cement particles, water, and additives. Under the microscope, cement paste shows a network of hydrated cement crystals and pores. The microstructure greatly influences concrete properties like strength and durability. The microstructure of concrete consists primarily of C-S-H gel, CH crystals, unhydrated cement particles, and interconnected pores. This pore network plays a critical role in influencing the permeability and long-term durability of concrete. Therefore, effective control of the internal structure through optimized mix design and proper curing techniques is vital for enhancing the concrete resistance to environmental degradation. In terms of strength development, Mix A0 achieved a compressive strength of 24.1 N/mm² at 7 days, which increased to 35.9 N/mm² at 28 days. In comparison, Mix B2 showed a higher early and later strength, reaching 32.1 N/mm² at 7 days and improving to 44.6 N/mm² at 28 days. Similarly, Mix C2 attained 29.1 N/mm² at 7 days and 41.5 N/mm² after 28 days of curing. These strength values serve as key indicators for assessing the mechanical performance and durability of each concrete mix over time. Figures 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 and 28 present the SEM analysis for all mixes at both 7-day and 28-day curing periods, comparing ordinary concrete with hybrid fiber-reinforced variants. The micrographs highlight various features such as crack propagation, C-S-H gel formation, and the presence of unhydrated cement particles, offering insight into the internal development and integrity of the mixes.

The SEM images shown in Figs. 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 and 28 for mixes A0, B2, and C2 at both 7-day and 28-day curing periods reveal a spatial and temporal evolution of these microstructural components. At 7 days, the cement paste is characterized by dispersed C-S-H gel interspersed with CH crystals and remaining unhydrated cement particles. The pore network is relatively more open, with visible microcracks initiating under early hydration stresses. By 28 days, significant densification of the C-S-H gel occurs, reducing pore sizes and bridging microcracks. This change reflects ongoing hydration and microstructural refinement, contributing to the observed increase in compressive strength.

Comparing ordinary concrete (Mix A0) with hybrid fiber-reinforced mixes (B2 and C2), the SEM micrographs suggest that incorporating hybrid fibers improves the microstructural integrity. The fibers act as internal reinforcement that hinders crack initiation and propagation, evident in reduced microcrack density and more cohesive matrix regions. Crack propagation patterns differ notably: fiber-reinforced mixes exhibit crack bridging and retardation, which are mechanisms contributing to enhanced toughness and durability. The fiber–matrix interface in these mixes shows good bonding, indicating efficient load transfer and mechanical synergy.

Furthermore, the presence of unhydrated cement particles at 7 days diminishes substantially by 28 days in fiber-reinforced mixes compared to ordinary paste, implying that fibers may facilitate improved hydration kinetics, potentially by modifying stress distribution and internal curing. The pore network also demonstrates better connectivity control in fiber mixes, suggesting lower permeability and improved resistance to environmental degradation. In inference, this SEM-based microstructural analysis validates the mechanical test results, where Mix B2 and Mix C2 outperform Mix A0 in compressive strength at both curing ages. The hybrid fibers meaningfully enhance microstructural quality by promoting denser C-S-H gel formation, mitigating microcracks, and optimizing pore structure. Such microstructural refinement is pivotal in improving both early-age and long-term performance of concrete, demonstrating the effectiveness of optimized fiber-reinforced mix designs combined with adequate curing regimes. This holistic view supports the vital role of microstructure in dictating concrete behaviour and guides future mix optimization to achieve durable, crack-resistant concrete materials.

Figure 29 presents a comparative analysis of the microstructural characteristics of cement paste in Conventional Concrete (CC) and Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (HFRC). In Fig. 28(a), the micrograph of specimen A0 (CC) shows that the main hydration products include calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel and layered calcium hydroxide (CH) crystals. Despite areas with dense hydration, portions of the paste appear rough, exhibiting voids, depressions, and micro-cracks features that may adversely affect the mechanical integrity of the cement matrix. Figures 28(b) and 28(c) demonstrate the influence of steel and polypropylene fibers on the microstructure. In specimen B2 (containing 1% steel fiber and 0.3% polypropylene fiber), the cement paste appears denser and more uniform compared to that of CC. The enhancement is largely attributed to improved hydration kinetics and the ability of hydration products to fill voids and seal micro-cracks. This densification results in a significant reduction in porosity. The presence of well-formed C-S-H gels, accompanied by tightly bonded hydration products and dispersed solid phases, contributes to a continuous and compact microstructure. In contrast, the hydrated cement paste of specimen A0 reveals a more porous and loosely packed structure, with visible flaky and snowflake-like crystalline formations. Figure 28(d) shows that specimen C2 (containing 0.03% glass fibers and 0.3% polypropylene fibers) achieved the most compact and uniform matrix among all HFRC samples. Micro-cracks and dissolution zones are scarcely observed, with only a few isolated pores visible. The C-S-H gels in this mix display a strongly interlocked and embedded arrangement, enhancing the bond strength and structural cohesion of the cement matrix.

-

Microstructures of ITZ at aggregate-cement paste

Figure 29 illustrates the microstructural features of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the cement paste and aggregates. In Fig. 30(a), corresponding to the A0 (Conventional Concrete) specimen, the aggregates are surrounded by hydration products and dispersed solute particles. However, these hydration products display numerous voids and lack the formation of a continuous, cohesive gel phase. Noticeable gaps and wide cracks in the ITZ indicate a weak and porous interfacial structure. Figures 30(b) and 30(c) depict the ITZ in specimen B2, which contains 1% steel fiber and 0.3% polypropylene fiber. Compared to A0, this sample exhibits a denser ITZ with visibly smaller pore sizes and narrower cracks. The improvement is primarily attributed to more complete hydration of cementitious materials, which enhances the packing and structure at the interface between the aggregates and the surrounding paste. Figure 30(d) highlights the ITZ characteristics in specimen C2, composed of 0.03% glass fiber and 0.3% polypropylene fiber. Although the quantity of gel phases in specimen A0 appears higher, the gels in C2 are more uniform and better integrated. In A0, internal stress generated during cement paste hardening leads to micro-separation at the interface, weakening the bond between the aggregates and the paste. This separation results in visible gaps in the gel layer, compromising the integrity of the ITZ and reducing its bonding capability.