Abstract

Obesity, insulin resistance (IR), and inflammation are key modifiable cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. We investigated the synergistic effects of body fat percentage (BFP) and the C-reactive protein-triglyceride-glucose index (CTI) on CVD risk. This prospective cohort included 6303 CVD-free Chinese adults (≥ 45 years) from the CHARLS. BFP was calculated via the CUN-BAE equation; the CTI integrates CRP, triglycerides, and fasting glucose. Multivariate Cox regression was used to assess associations with incident CVD over 7 years. Mediation and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to evaluate pathways and predictive performance. Among 1124 incident CVD cases, concurrent high BFP (> 30.8%) and CTI (> 4.68) showed 1.48-fold higher CVD risk (95% CI 1.21–1.80) versus low-level groups. The combined BFP-CTI model improved prediction (AUC = 0.581; DeLong’s P < 0.05) over individual indices. Mediation revealed bidirectional effects: CTI mediated 8.76% of BFP’s CVD association, while BFP mediated 12.22% of CTI’s effect (P < 0.001). Synergy was strongest in adults ≤ 60y (HR = 1.76, CI 1.25–2.48) and diabetics (HR = 3.52, CI 1.69–7.31). The combination of high BFP and high CTI was associated with a synergistic increase in CVD risk, with bidirectional mediation between adiposity and metabolic-inflammation pathways. Joint assessment enhances risk stratification, particularly in younger and diabetic populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are among the leading causes of death globally, imposing significant health and economic burdens on society. As of 2023, CVD claim over 18 million lives annually, accounting for 32% of all deaths globally1. However, projections indicate that CVD-related mortality is expected to increase to 35.6 million deaths by 20252, highlighting the urgent need for effective prevention and treatment strategies. China faces elevated cardiovascular risks and mortality rates, with approximately 330 million individuals affected by CVD, where CVD-related deaths account for nearly 45% of total mortality3. Current therapeutic approaches, including pharmacological interventions, surgical procedures, and lifestyle modifications, often encounter challenges such as limited efficacy, poor patient adherence, and high recurrence rates4. Thus, it is essential to explore the underlying mechanisms and risk factors associated with CVD to develop more effective prevention and management strategies5.

Recent studies have identified obesity and insulin resistance (IR) as critical biological markers influencing the risk of CVD6. Elevated body fat and IR have been shown to correlate significantly with CVD incidence, potentially exacerbating disease progression through mechanisms involving inflammation and metabolic dysregulation. Understanding the relationship between these factors and CVD can provide insights into their pathophysiological roles and inform the development of targeted interventions aimed at reducing CVD risk. Body fat percentage (BFP), a more precise measure of body composition than body mass index (BMI), has emerged as a crucial indicator of obesity-related health risks7,8. BMI, as a commonly used indicator of obesity, fails to distinguish between fat mass and muscle mass, potentially masking the true risk associated with visceral adiposity or metabolic abnormalities9. BFP provides a more accurate representation of individual adiposity status, while studies demonstrate that BFP exhibits superior predictive sensitivity for CVD risk and mortality compared to BMI10,11,12. This is particularly relevant in clinical assessments where body composition can significantly impact health outcomes.

Furthermore, IR, a condition wherein cells become less responsive to insulin, is associated with increased inflammation and oxidative stress, further promoting the development of atherosclerosis and related cardiovascular events13. Although the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (HEC) technique is regarded as the gold standard for assessing IR, its technical complexity, invasive nature, and prohibitive costs render it unsuitable for both clinical practice and epidemiological investigations14. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, introduced as a reliable biomarker for IR, has gained traction in clinical settings and has been linked to adverse CVD outcomes, including stroke and myocardial infarction15. The TyG index was calculated from triglycerides (TG) and fasting plasma glucose (FPG). In addition to body fat and IR, inflammation plays a vital role in CVD pathogenesis. C-reactive protein (CRP), a non-specific inflammatory marker, has been identified as a potential predictor of CVD risk, contributing to atherosclerotic processes and vascular dysfunction16,17,18. The C-reactive protein triglyceride-glucose index (CTI) has been proposed as a composite marker reflecting both IR and inflammation, which may improve CVD risk stratification and early identification of at-risk individuals19. Given the interconnectedness of these biological markers, it is essential to investigate their combined effects on CVD risk to enhance preventive and therapeutic strategies.

While the individual roles of obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammation in CVD pathogenesis are well-established, the optimal method for integrating these pathways into a practical risk stratification tool, particularly in the Chinese population, remains unclear. To address these knowledge gaps, we utilized data from the prospective cohort of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). This study does not seek to propose new biological mechanisms, but rather to empirically compare and combine easily accessible clinical metrics BFP and the CTI index to assess their interactive and joint associations with CVD risk in a prospective national cohort. Our aim is to inform whether such a combined approach offers incremental utility for risk prediction beyond the consideration of these factors in isolation. By employing robust statistical methods, this research aims to elucidate the interplay between these critical health indicators and their collective impact on CVD risk.

Methods

Study population and design

The CHARLS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey targeting middle-aged and older adults (≥ 45 years) in China20. CHARLS employs a multistage probability sampling design to ensure population representativeness across socioeconomic and geographic strata, selecting participants from 150 counties (districts) and 450 villages (communities) across 28 provinces. The database comprehensively collects socioeconomic status, health behaviors, chronic disease diagnoses, biochemical measurements, and anthropometric data through face-to-face interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests. The protocol for the CHARLS cohort was approved by Peking University’s Ethics Review Committee (IRB00001052–11,015), and all participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation.

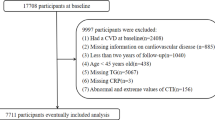

Our analysis utilized CHARLS waves from 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2018, which constitute the complete follow-up cycles with adjudicated CVD outcomes. The 2011 wave served as the baseline for assessing covariates and calculating cumulative exposure metrics, while subsequent waves provided longitudinal outcome data. Participants were sequentially excluded based on the following criteria: (1) participants with missing baseline CVD data or pre-existing CVD at baseline; (2) participants aged below 45 years at baseline; (3) participants lacking baseline BFP and CTI data; (4) participants with missing CVD data during follow-up. Finally, a total of 6303 participants meeting the inclusion criteria were included in this study. Figure 1 shows the screening process for the study population in the current study.

Diagnosis of CVD

The diagnosis of CVD was based on self-reported heart disease or stroke. Similar to previous studies, the interviewer will ask the participants a question, such as “Have you been told by a doctor that you have been diagnosed with a heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems?” or “Have you been told by a doctor that you have been diagnosed with a stroke?” Participants who reported heart disease or stroke were defined as having CVD21. Participants who had diagnosed CVD at 2011 were excluded, and if the participants were diagnosed with CVD until the follow-up period in 2018, they were included in the study and were defined as having new-onset CVD. Additionally, if a participant indicated a heart attack or stroke at a previous round of follow-up, they were required to verify the presence of CVD at a later round of follow-up22. If participants denied a previous self-reported diagnosis of heart disease or stroke, these inconsistencies were corrected retrospectively. Our diagnoses of CVD were consistent with previous studies using CHARLS22,23.

The definition of BFP and CTI

BFP was estimated using the Clínica Universidad de Navarra‐Body Adiposity Estimator (CUN‐BAE) equation: BFP = 44.988 + (0.503 age) 10.689 × sex) + (3.72 × BMI) − (0.026 × BMI2) + (0.181 × BMI × sex) − (0.02 × BMI × age) − (0.005 × BMI2 × sex) + (0.00021 × BMI2 × age) where female gender is defined as 1 and male gender is defined as 0, and BMI = weight in kilograms/ (height in metres)224. Height was measured using the SecaTM213 stadiometer (Medical Scales and Measuring Systems Seca (Hangzhou) Co., Ltd.), while weight was measured using the OmronTM HN-286 scale (Krell Precision (Yangzhou) Co., Ltd.)25. The BFP calculated by this method demonstrates high concordance with actual BFP measured by air displacement plethysmography (ADP) (Pearson’s r = 0.89, P < 0.000001)24. Furthermore, the reliability of this methodology has been robustly validated across multiple independent studies25.

The calculation formula of CTI is as follows26: CTI = 0.412 × Ln (CRP [mg/L]) + Ln (TG [mg/dl] × FPG [mg/dl])/2. All participants provided venous blood samples after fasting for at least 8 h. For each participant, 8 mL of venous blood was collected and immediately frozen at − 20 °C. The samples were transported within two weeks to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Beijing, where they were stored at − 80 °C until analysis20. The analytical methods and detection limits for the aforementioned laboratory indicators are detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Covariates

Covariates mainly include demographic data, lifestyle and metabolic factors. We included age, sex, marital status, educational level and residence place to adjust for differences in demographic data. Educational level was categorized as no formal education, primary school, middle school, high school or above. Marital status was categorized as married and other marital statuses (separated, divorced, widowed and never married). The residence place was categorized as rural or urban27.

Lifestyle covariate included the drinking and smoking status. Metabolic risk factors include hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM) and BMI. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg or being told by a doctor that they had hypertension. DM was defined as FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, glycated hemoglobin ≥ 6.5%, random blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L or being told by a doctor that they had DM28. We also classified blood lipids laboratory test results as confounding factors because they have a strong correlation with CVD. Laboratory test results included total cholesterol (TC), TG, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).

Missing data processing

In our study, participants with incomplete BFP information (3321, 18.75%), CTI index information (3228, 18.23%) and missing CVD follow-up data (1863, 10.52%) were excluded. The final analytical cohort exhibited minimal missing data, with only 2 cases (0.03%) of missing educational level and 12 cases (0.19%) of missing LDL-C among all covariate variables. To assess potential selection bias, we compared the baseline characteristics of the excluded participants with those retained in the study (Supplementary Table 2).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted by R software (version 4.4.3). Means and standard errors (SE) were used to present continuous variables, while numbers and percentages were used for categorical variables. The median values of BFP (30.80%) and CTI (4.68) were employed as cutoff points to classify respondents into four categories: low BFP and low CTI, low BFP and high CTI, high BFP and low CTI, high BFP and high CTI. The normality of all continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and visual inspection of histograms. As most key variables (e.g., CRP, TG, FPG) deviated significantly from a normal distribution (P-Shapiro–Wilk < 0.05), they are presented as means ± standard errors (SE). Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Differences in baseline characteristics across groups were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier curves were illustrated to estimate the cumulative incidence of CVD, and differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test. Correlations between BFP, CTI and CVD risk were assessed using Cox regression analysis. We have established three multivariable Cox regression model: Crude model, no covariates were adjusted; Model 1: age, sex, marital status, education level and residence place were adjusted; Model 2: age, sex, marital status, education level, residence place, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, hypertension, DM and blood lipids laboratory test results were adjusted. For BFP or CTI indexes, variables already included in the equations were not adjusted for in the Cox regression models. Results from the Cox regression analysis are reported as Hazard Ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We assessed potential multicollinearity among variables in each model using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF values for all variables in each model were below 10 and no significant multicollinearity problems were detected.

A restricted cubic spline (RCS) model with three equally spaced nodes was used to investigate the nonlinear and dose–response trends association between BFP and CTI with CVD risk. The abilities of these indexes to predict CVD risk were evaluated using ROC curves. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each index to predict CVD risk. We also used DeLong’s test to detect differences in the AUCs of different indexes. Subgroup and interaction analyses were performed by stratifying and clustering by age, sex, drinking status, smoking status, hypertension status and DM status to examine the variations in the association between BFP and CTI with CVD risk across different subgroups. “Mediation” package was utilized to perform Mediation analysis assessing the mediating effects of BFP and CTI with the CVD risk, adjusted by marital status, education level, residence place, smoking status, drinking status, hypertension, DM and TC, HDL-C and LDL-C29. The presence of a mediating effect was defined as satisfying all of the following conditions having a significant indirect effect, a significant total effect, and a positive proportion of the mediator effect. We note that the mediation analysis relies on strong assumptions, including no unmeasured confounding between the exposure-mediator and mediator-outcome relationships. Given the observational nature of our study and the fact that BFP and CTI were measured concurrently at baseline, these results should be interpreted as exploratory evidence of potential mechanistic pathways rather than definitive causal mediation. P value < 0.05 is considered to have statistical difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 6303 participants (54.21% female) were included in this study, with an average age of 58.30 ± 8.73 years. Participants were categorized into four subgroups based on BFP and CTI levels: low BFP and low CTI (n = 170), low BFP and high CTI (n = 1411), high BFP and low CTI (n = 1414), and high BFP and high CTI (n = 172). The baseline characteristics of the participants were summarized in Table 1. Statistically significant differences were observed in most baseline characteristics among the four subgroups, including age, sex, marital status, educational level, residence place, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, hypertension, DM, CRP FPG, TC, TG, HDL-C and LDL-C. During the 7-year follow-up period, a total of 1124 individuals were diagnosed with new-onset CVD (heart disease, 844 cases; stroke, 365 cases), and the incidence of CVD was 17.83%. The low-BFP and low-CTI subgroup demonstrated the lowest incidence of CVD (13.22%), whereas the high-BFP and high-CTI subgroup exhibited the highest CVD incidence (22.45%).

Association of BFP and CTI with the risk of CVD

Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrated that the cumulative incidence of CVD increased with high BFP, high CTI, and both high BFP and high CTI (Fig. 2) (all log-rank P < 0.0001). Multivariable Cox regression models were employed to assess the independent associations of BFP and CTI with CVD risk, with results presented in Table 2. After adjusting for age, sex, marital status, education level, residence place, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, hypertension, DM and blood lipids laboratory test results, elevated BFP and CTI demonstrated independent associations with incident CVD (BFP: HR = 1.022 per 1% increase, 95% CI 1.012–1.032; CTI: HR = 1.164 per 1unit increase, 95% CI 1.026–1.399). When stratified by median values, participants with high BFP exhibited a 1.205-fold increased risk of CVD compared to those with low BFP (HR = 1.205, 95% CI 1.038–1.399). Similarly, individuals with high CTI showed a 1.151-fold higher CVD risk relative to the low-CTI group (HR = 1.151, 95% CI 1.004–1.319), after adjustment for all covariates. RCS analyses confirmed monotonic dose–response relationships for both biomarkers (nonlinearity P > 0.05) (Fig. 3).

(A) RCS model analysis the dose–response relationships between BFP and CVD risk; (B). RCS model analysis the dose–response relationships between CTI and CVD risk. We adjusted the model fully for age, sex, marital status, education level, residence place, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, hypertension, DM and blood lipids laboratory test results. CVD, cardiovascular disease; BFP, body fat percentage; CTI, C-reactive protein triglyceride-glucose index.

Notably, the joint exposure to high BFP and high CTI exhibited a supra-additive effect. Taking participants with low BFP and low CTI as the reference group, individuals with solely high CTI, solely high BFP, and both high BFP and high CTI were significantly associated with elevated risks of CVD by 1.3-fold (95% CI 1.077–1.569), 1.26-fold (95% CI 1.032–1.539), and 1.476-fold (95% CI 1.21–1.8), respectively (Table 3). The ROC analyses showed that combine BFP and CTI had a favorable performance to predict CVD risk than BFP or CTI alone with an AUC of 0.581 (DeLong’s test P < 0.05) (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that while the absolute AUC value is relatively low, the significant improvement underscores the complementary information provided by integrating adiposity and metabolic-inflammation pathways, rather than advocating for its use as a standalone high-performance predictor.

Subgroup analyses

We conducted subgroup analyses to assess the associations of BFP and CTI with CVD risk. The associations between BFP/CTI and CVD risk were consistent with the primary findings across most subgroups (Table 4). Notably, significant interaction effects were observed for age and DM status with the combined BFP-CTI exposure on CVD risk (P-interaction < 0.05 for both). Specifically, the associations between elevated BFP/CTI levels and CVD risk were more pronounced in participants aged ≤ 60 years (HR = 1.759, 95% CI 1.250–2.475) and those with DM (HR = 3.516, 95% CI 1.691–7.313) compared to older adults (HR = 1.438, 95% CI 0.958–2.160) and non-DM individuals (HR = 1.360, 95% CI 1.027–1.801). These findings suggest synergistic metabolic dysregulation in younger populations and DM patients amplifies adiposity-related cardiovascular toxicity.

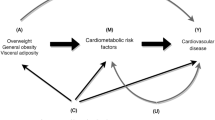

Mediation analysis

Through formal mediation analyses, we quantified the reciprocal pathways between BFP and CTI in CVD pathogenesis. CTI mediated 8.76% (P < 0.001) of the total association between BFP and CVD risk, while BFP mediated 12.22% (P < 0.001) of the total association between CTI and CVD risk (Fig. 5). This bidirectional mediation pattern suggests adiposity and metabolic dysregulation mutually reinforce CVD risk through distinct yet interconnected biological mechanisms.

(A) Mediation analysis of CTI on the association between BFP and the risk of CVD; (B). Mediation analysis of BFP on the association between CTI and the risk of CVD. We adjusted the model fully for marital status, education level, residence place, smoking status, drinking status, hypertension, DM and TC, HDL-C and LDL-C; CVD, cardiovascular disease; BFP, Body fat percentage; CTI, C-reactive protein triglyceride-glucose index.

Discussion

This prospective cohort study of 6303 Chinese adults provides novel evidence that BFP and CTI synergistically amplify CVD risk. Participants with concurrent high BFP (> 30.8%) and CTI (> 4.68) faced a 1.48-fold increased CVD risk (95% CI 1.21–1.80) compared to those with low levels of both markers—a risk magnitude exceeding the sum of their individual effects (high BFP alone: HR = 1.205; high CTI alone: HR = 1.151). The combined BFP-CTI model demonstrated incremental predictive value (AUC = 0.581) over isolated metrics (DeLong’s test P < 0.05), highlighting the clinical relevance of integrating adiposity and metabolic-inflammation pathways for risk stratification. Importantly, mediation analyses revealed bidirectional pathways: CTI mediated 8.76% of BFP’s effect on CVD, while BFP mediated 12.22% of CTI’s effect (P < 0.001). The bidirectional mediation pattern is consistent with the hypothesis of a reciprocal relationship between adiposity and metabolic inflammation.

The limitations of BMI in capturing obesity-related CVD risk are well-documented30. BMI fails to differentiate between fat mass and lean mass, potentially misclassifying individuals with high muscle mass (e.g., athletes) as obese or those with normal BMI but excessive visceral adiposity (e.g., "metabolically obese normal weight" phenotype) as low-risk31,32. In contrast, BFP provides a direct measure of adiposity, correlating more strongly with visceral fat accumulation—a key driver of cardiometabolic dysfunction33,34. Multiple studies have demonstrated significant associations between BFP and CVD risk. For instance, a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data revealed that individuals in the highest quartile of BFP had a 3.99-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease (95% CI 1.58–10.88) compared to those in the lowest quartile, with similarly elevated risks for hypertension and DM35. These findings are corroborated in pediatric populations, where elevated BFP in children and adolescents was independently linked to IR, dyslipidemia, and hypertension36,37. BFP thresholds for CVD risk prediction vary across populations. In Korean adults, thresholds of ≥ 21% for male and ≥ 37% for female were associated with significantly higher CVD risks (OR = 4.05 and 3.21, respectively)38. Notably, Asian populations exhibit higher BFP at equivalent BMI levels compared to Caucasians, suggesting the need for population-specific adjustments in obesity criteria39. We found that elevated BFP (> 30.8%) independently predicted CVD risk (HR = 1.205, 95% CI 1.038–1.399) even after adjusting for BMI, suggesting that adiposity-specific metrics like BFP should supplant BMI in clinical risk assessments.

CTI, developed by Ruan et al.26, serves as a significant tool for the prognostic evaluation of cancer patients. This index synthesizes CRP, a recognized biomarker of inflammation, and TyG index, a biomarker of IR. The TyG index is a validated surrogate marker of IR. The concept of integrating inflammation into metabolic risk assessment is further bolstered by studies on liver-derived risk scores. For instance, the APRI score, a marker of liver inflammation and fibrosis, has been independently associated with increased cardiovascular risk, underscoring the importance of extra-cardiac inflammatory sources in CVD pathogenesis40. Large-scale studies demonstrate its predictive value for metabolic syndrome, DM, and CVD41. A multinational prospective cohort study involving 141,243 participants from 22 countries further confirmed that elevated TyG index independently correlates with increased risks of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and incident DM, particularly in low- and middle-income countries42. In patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrom, a higher TyG index is independently associated with coronary artery disease severity and major adverse cardiovascular events (HR = 1.88, 95% CI 1.13–3.12)43. In addition to IR, inflammation serves as another critical risk factor for CVD. Among numerous inflammatory biomarkers, CRP has garnered the most attention due to its established utility in CVD screening and risk reclassification. Elevated CRP levels, a marker of systemic inflammation, are strongly associated with IR, DM, and CVD44. CRP not only reflects inflammatory activity but also directly contributes to endothelial dysfunction and plaque formation, serving as a critical predictor of CVD risk44. Elevated CRP levels (> 3 mg/L) are independently associated with a 58% increased risk of incident coronary heart disease (95% CI 1.37–1.83), even after comprehensive adjustment for traditional risk factors45.

However, a growing body of evidence demonstrates an inseparable pathophysiological interplay between IR and inflammation in CVD, characterized by bidirectional crosstalk that amplifies endothelial damage and atherosclerotic progression. IR and chronic inflammation are closely interconnected through multiple biological pathways. The inflammatory marker CRP further exacerbates endothelial dysfunction by impairing nitric oxide synthase activity in progenitor cells, creating a proatherosclerotic environment that links IR to cardiovascular complications46,47. These findings collectively demonstrate that chronic low-grade inflammation acts as both a cause and consequence of IR, creating a vicious cycle that promotes metabolic syndrome and associated comorbidities. In our study, we introduced the CTI, a novel and comprehensive metric specifically developed to evaluate the interplay between insulin resistance and inflammatory pathways in the pathogenesis of CVD. Our findings robustly demonstrate that the CTI is significantly associated with CVD risk, with each unit increase in CTI corresponding to a 16.4% elevated risk of incident CVD (HR = 1.164, 95% CI 1.026–1.321).

While the intricate interplay among obesity, IR, and inflammation in CVD pathogenesis remains incompletely understood, our study reveals that concurrent elevations in BFP and CTI synergistically amplify CVD risk. Although the absolute discriminative ability of the combined model (AUC = 0.581) was modest, the statistically significant improvement over either index alone (DeLong’s P < 0.05) suggests that integrating adiposity and metabolic-inflammation pathways provides complementary information for understanding CVD risk etiology, rather than advocating for its immediate standalone clinical use as a predictor. Notably, this association was significantly stronger in participants younger than 60 years (HR = 1.759, 95% CI 1.250–2.475) or those with DM (HR = 3.516, 95% CI 1.691–7.313), compared to older (HR = 1.438) and non-DM individuals (HR = 1.360) (P for interaction < 0.05). Obesity-induced chronic inflammation plays a central role in the pathogenesis of IR, as pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 disrupt insulin signaling in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and liver by inhibiting key phosphorylation steps in insulin receptor substrates48,49. Adipose tissue serves as a primary site for this interaction, with activated tissue-resident macrophages secreting inflammatory mediators that induce localized and systemic IR through autocrine/paracrine and endocrine mechanisms50. Crucially, our mediation analyses revealed significant reciprocal mediation effects between BFP and CTI in driving CVD events, with BFP mediating 8.76% and CTI mediating 12.22% of each other’s associations with CVD risk. This bidirectional mediation architecture robustly confirms the tripartite interplay among adiposity, IR, and systemic inflammation in CVD pathogenesis. Although our mediation analysis suggests potential bidirectional pathways between adiposity and metabolic-inflammation, several important limitations must be considered. The analysis relies on strong assumptions, including no unmeasured confounding between the exposure-mediator and mediator-outcome relationships. While we adjusted for a comprehensive set of covariates, residual confounding remains possible. Furthermore, as both BFP and CTI were measured at a single baseline time point, our analysis captures statistical mediation but cannot definitively establish the temporal dynamics or causality of a truly reciprocal process. Therefore, these results should be interpreted as generating hypotheses about potential mechanistic interplay rather than providing definitive evidence of causal mediation.

As the first prospective cohort study investigating BFP and CTI in CVD, several limitations of the current research should be acknowledged. First, due to the observational study design, we cannot confirm causal relationships between BFP, CTI, and CVD risk. However, BFP and TCI have been extensively validated as predictors of CVD events. This study aimed to assess the combined exposure effects and reciprocal mediation relationships between BFP and CTI regarding cardiovascular risk. Second, we still cannot exclude the possibility of residual or unmeasured confounding bias that might affect effect size estimations. Despite adjusting for a wide range of demographic, lifestyle, and metabolic covariates, as well as medication use, we cannot rule out residual confounding from unmeasured or imperfectly measured factors, such as detailed dietary patterns, physical activity levels, and medication adherence. Third, the diagnosis of CVD in our study was based on self-report, which might lead to misclassification bias due to under-reporting of asymptomatic cases or over-reporting due to misdiagnosis. Although this method is consistent with previous studies using the same database and has been used in published literature51,52, it remains a limitation compared to adjudicated medical records. Fourth, we used BFP as a surrogate measure of body fat and CTI as a proxy indicator of IR and inflammation. Both measurement methods might deviate from true biological values, requiring further studies to validate their measurement accuracy. Furthermore, BFP and CTI were assessed only at baseline, and we could not account for their potential changes over the follow-up period, which might lead to regression dilution bias and potentially underestimate the true association. Finally, a substantial proportion of the original CHARLS cohort was excluded due to missing data on BFP or CTI, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Our supplementary analysis (Supplementary Table 2) indicates that the excluded participants had significant differences from the population included in this study in most baseline data. Therefore, the extrapolation of our results should be made with caution. Future studies with more complete data are needed to validate our findings in broader populations.

In summary, our findings suggest that the joint assessment of BFP and CTI provides complementary information for understanding CVD risk etiology, highlighting a synergistic interplay between adiposity and metabolic-inflammation. While both indices are derived from routine or low-cost measurements (anthropometry and basic blood tests), suggesting potential for affordable risk assessment, future studies incorporating formal cost-effectiveness analyses are necessary to determine their practical utility and value in specific clinical settings.

Conclusions

In summary, through a prospective nationwide cohort study in Chinese adults, we found that IR and inflammation significantly mediated the association between obesity and CVD risk, and vice versa. The findings highlight the combined exposure effects of BFP and CTI levels on CVD events and suggest that joint assessment of BFP and CTI could further stratify CVD risk.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the CHARLS database (https://charls.pku.edu.cn/).

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- BFP:

-

Body fat percentage

- CTI:

-

C-reactive protein triglyceride-glucose index

- CHARLS:

-

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- HEC:

-

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp

- TyG:

-

Triglyceride-glucose

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ADP:

-

Air displacement plethysmography

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- SE:

-

Standard errors

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- Cis:

-

Confidence intervals

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

References

Ji, W. et al. Air pollution, lifestyle, and cardiovascular disease risk in northwestern China: A cohort study of over 5.8 million participants. Environ. Int. 199, 109459 (2025).

Chong, B. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 32(11), 1001–1015 (2024).

Hu, S. S. Writing committee of the report on cardiovascular H, diseases in C. Epidemiology and current management of cardiovascular disease in China. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 21(4), 387–406 (2024).

Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 76(25), 2982–3021 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Analysis and prediction of research hotspots and trends in heart failure research. J. Transl. Int. Med. 12(3), 263–273 (2024).

Welsh, A., Hammad, M., Pina, I. L. & Kulinski, J. Obesity and cardiovascular health. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 31(8), 1026–1035 (2024).

Zeng, Q., Dong, S. Y., Sun, X. N., Xie, J. & Cui, Y. Percent body fat is a better predictor of cardiovascular risk factors than body mass index. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 45(7), 591–600 (2012).

Lee, H., Rhee, T. M., Choi, J. M., Choi, S. Y. & Kim, D. W. The close link between obesity and cardiovascular disease: Current insights and remaining challenges. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 54(1), 175–192 (2025).

Haidar, A. & Horwich, T. Obesity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 25(11), 1565–1571 (2023).

Si, S. et al. Body surface area, height, and body fat percentage as more sensitive risk factors of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Cancer Med. 9(12), 4433–4446 (2020).

Britton, K. A. et al. Body fat distribution, incident cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62(10), 921–925 (2013).

De Schutter, A., Lavie, C. J., Patel, D. A., Artham, S. M. & Milani, R. V. Relation of body fat categories by Gallagher classification and by continuous variables to mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 111(5), 657–660 (2013).

Suren Garg, S., Kushwaha, K., Dubey, R. & Gupta, J. Association between obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance: Insights into signaling pathways and therapeutic interventions. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 200, 110691 (2023).

DeFronzo, R. A., Tobin, J. D. & Andres, R. Glucose clamp technique: A method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am. J. Physiol. 237(3), E214–E223 (1979).

Dang, K. et al. The association between triglyceride-glucose index and its combination with obesity indicators and cardiovascular disease: NHANES 2003–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23(1), 8 (2024).

Burger, P. M. et al. C-reactive protein and risk of incident heart failure in patients with cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 82(5), 414–426 (2023).

Kuppa, A., Tripathi, H., Al-Darraji, A., Tarhuni, W. M. & Abdel-Latif, A. C-reactive protein levels and risk of cardiovascular diseases: A two-sample bidirectional mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(11), 9129 (2023).

De Matteis, C. et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia is linked to MASLD. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 131, 49–57 (2025).

Huo, G. et al. Association between C-reactive protein-triglyceride glucose index and stroke risk in different glycemic status: Insights from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24(1), 142 (2025).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: The China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43(1), 61–68 (2014).

Cui, C. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index, renal function and cardiovascular disease: a national cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22(1), 325 (2023).

Zheng, G. et al. Association between atherogenic index of plasma and future risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stages 0–3: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24(1), 22 (2025).

Ren, Q. et al. Association between triglyceride glucose-waist height ratio index and cardiovascular disease in middle-aged and older Chinese individuals: a nationwide cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23(1), 247 (2024).

Gomez-Ambrosi, J. et al. Clinical usefulness of a new equation for estimating body fat. Diabetes Care 35(2), 383–388 (2012).

Lv, H. et al. Association between obesity measurement indexes and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis among the Chinese population: Analysis from a nationwide longitudinal study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25(1), 986 (2024).

Ruan, G. T. et al. A novel inflammation and insulin resistance related indicator to predict the survival of patients with cancer. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 905266 (2022).

Huo, R. R., Liao, Q., Zhai, L., You, X. M. & Zuo, Y. L. Interacting and joint effects of triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) and body mass index on stroke risk and the mediating role of TyG in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23(1), 30 (2024).

Tian, X., Qu, Z., Sun, Y. & Zhang, B. Association between the advanced lung cancer inflammation index and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with RA: Insights from NHANES data analysis. Heliyon 10(13), e33673 (2024).

Tingley, D., Teppei, H., Mit, Y., Keele, L. & Imai, K. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 59(5), 1–38 (2014).

Tutor, A. W., Lavie, C. J., Kachur, S., Milani, R. V. & Ventura, H. O. Updates on obesity and the obesity paradox in cardiovascular diseases. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 78, 2–10 (2023).

Al-Kamil, R. et al. The effect of nutritional genomics on cardiovascular system. Georgian Med. News 347, 168–176 (2024).

Soufi, M., Sattler, A. M., Herzum, M., Maisch, B. & Schaefer, J. R. Molecular basis of obesity and the risk for cardiovascular disease. Herz Kardiovask. Erkrank. 31(3), 200–206 (2006).

De Matteis, C. et al. Improving cardiovascular risk stratification: the role of abdominal obesity in predicting MACEs. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24(1), 328 (2025).

De Matteis, C. et al. Identification of a novel score for adherence to the mediterranean diet that is inversely associated with visceral adiposity and cardiovascular risk: The chrono med diet score (CMDS). Nutrients 15(8), 1910 (2023).

Si, J., Kang, L. & Liu, Y. Association between body fat percentage and cardiometabolic diseases in general population. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 24(12), 1395–1400 (2024).

Serrano, N. C., Suarez, D. P., Silva, A. R., Gamboa-Delgado, E. & Quintero-Lesmes, D. C. Association between body fat mass and cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents in Bucaramanga Colombia. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 6(4), 135–141 (2019).

Higgins, P. B., Gower, B. A., Hunter, G. R. & Goran, M. I. Defining health-related obesity in prepubertal children. Obes. Res. 9(4), 233–240 (2001).

Kim, C. H., Park, H. S., Park, M., Kim, H. & Kim, C. Optimal cutoffs of percentage body fat for predicting obesity-related cardiovascular disease risk factors in Korean adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 94(1), 34–39 (2011).

Deurenberg-Yap, M. & Deurenberg, P. Is a re-evaluation of WHO body mass index cut-off values needed? The case of Asians in Singapore. Nutr. Rev. 61(5 Pt 2), S80–S87 (2003).

De Matteis, C. et al. AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) is an easy-to-use predictor score for cardiovascular risk in metabolic subjects. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 14834 (2021).

Gounden, V., Devaraj, S. & Jialal, I. The role of the triglyceride-glucose index as a biomarker of cardio-metabolic syndromes. Lipids Health Dis. 23(1), 416 (2024).

Lopez-Jaramillo, P. et al. Association of the triglyceride glucose index as a measure of insulin resistance with mortality and cardiovascular disease in populations from five continents (PURE study): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 4(1), e23–e33 (2023).

Mao, Q. et al. The triglyceride-glucose index predicts coronary artery disease severity and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Dis. Markers 2019, 6891537 (2019).

Nesto, R. C-reactive protein, its role in inflammation, Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and the effects of insulin-sensitizing treatment with thiazolidinediones. Diabet. Med. 21(8), 810–817 (2004).

Buckley, D. I., Fu, R., Freeman, M., Rogers, K. & Helfand, M. C-reactive protein as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analyses for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 151(7), 483–495 (2009).

Sjoholm, A. & Nystrom, T. Endothelial inflammation in insulin resistance. Lancet 365(9459), 610–612 (2005).

Theuma, P. & Fonseca, V. A. Inflammation, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2(2), 105–113 (2004).

de Luca, C. & Olefsky, J. M. Inflammation and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 582(1), 97–105 (2008).

Shoelson, S. E., Lee, J. & Goldfine, A. B. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 116(7), 1793–1801 (2006).

Yan, K. Recent advances in the effect of adipose tissue inflammation on insulin resistance. Cell Signal 120, 111229 (2024).

Tian, X., Yang, X., Cao, Y., Qu, Z. & Zhang, B. Association between the depression and cardiovascular risk in arthritis patients: a prospective cohort study from the CHARLS database. Front. Immunol. 16, 1590483 (2025).

Zhao, Y. C. et al. Predictive value of the combined triglyceride-glucose and frailty index for cardiovascular disease and stroke in two prospective cohorts. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24(1), 318 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CHARLS project members and every respondent for the time and effort that they have devoted to the CHARLS project.

Funding

This work was supported by the Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant numbers 2024-BS-186, 2024].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XY. Tian: Methodology, investigation, validation, writing original draft. ZA. Qu: Wrote and critically revised the manuscript. XL. Yang: Validation, investigation, formal analysis, writing original draft. Y. Cao: Formal analysis, software. BC. Zhang: Conceptualization, supervision, writing review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The entire study process adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided written informed consent at the time of participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, X., Qu, Z., Yang, X. et al. Synergistic effects of body fat percentage and C-reactive protein triglyceride–glucose index on cardiovascular disease risk: a Chinese cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 40266 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24094-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24094-5