Abstract

The traumatic penumbra (TP) is a secondary injury zone surrounding the core area of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and plays a critical role in determining TBI outcomes. The primary pathological change in the TP is brain edema, which includes both vasogenic and intracellular edema. Brain edema is closely associated with the expression of aquaporin-4 (AQP4). Bevacizumab, a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor, reduces vascular permeability. However, the effect of bevacizumab on traumatic brain edema remains unclear, as does its potential molecular mechanism in relation to AQP4. To examine the pathological changes and alterations in AQP4 expression following bevacizumab treatment in the TP. A total of 70 Wistar rats were randomly divided into five groups: a control group, a sham group, a TBI group, a TBI + normal saline group, and a TBI + bevacizumab group. Twenty-four hours after treatment, TP tissue samples were collected for analysis. Histopathological structural changes were examined using hematoxylin-eosin staining and transmission electron microscopy. Western blot was employed to assess changes in AQP4 protein levels, and double-labeling immunofluorescence was utilized to observe the AQP4 and VEGF. After TBI, the primary pathological changes in the TP were characterized by cerebral edema, which included both vasogenic and intracellular edema. Bevacizumab treatment reduced both types of edema. After TBI, AQP4 and VEGF expression in the TP was upregulated, and depolarization of AQP4 distribution was observed. However, bevacizumab treatment led to a downregulation of AQP4 and VEGF expression, and suppression of the AQP4 depolarized distribution. Bevacizumab alleviates cerebral edema in the TP after TBI by modulating the expression and polarized distribution of AQP4. Thus, bevacizumab may serve as a potential therapeutic agent for the clinical treatment of TP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) represents a significant threat to human health, is a leading cause of disability and mortality in individuals with brain injuries, and imposes a considerable economic burden on both families and society1,2. Although significant progress in the treatment of TBI in recent years, there is a lack of effective treatment measures2,3. After TBI, a cascade of secondary injuries can arise, including abnormal cerebral perfusion, excitotoxicity, blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cerebral edema4,5,6. The traumatic penumbra (TP) is a bidirectional recovery zone surrounding the core necrotic area after TBI. Timely and effective intervention in this region can reverse the condition and reduce both disability and mortality7,8. As a result, TP is a critical target for clinical diagnosis and treatment after TBI4,9, with brain edema serving as a key pathological change associated with BBB damage10. Therefore, investigating the molecular and pathological mechanisms of the TP is crucial.

The extent of edema in the TP correlates with the expression of aquaporin-4 (AQP4)11,12, and changes in AQP4 levels can reflect the progression of brain edema13. Bevacizumab is a recombinant, humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits vascular permeability14. Studies have demonstrated that bevacizumab can alleviate macular edema in individuals with diabetes15,16. In addition, bevacizumab can treat tumor-associated brain edema, especially radiation-induced brain edema, by targeting and inhibiting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway17,18,19,20. Previous study have shown that bevacizumab has certain value in reducing brain edema in TBI9. However, the pathological process of brain edema in TBI treated with bevacizumab is still unclear, and whether its molecular mechanism is associated with AQP4?

In light of the aforementioned issues, this study aimed to investigate the pathological changes in the TP and the expression of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) after bevacizumab treatment for TBI, with the goal of elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying its effects on the TP.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Adult male Wistar rats (age, 7–9 weeks; weight, 230–250 g) were obtained from Chongqing Tengxin Biotechnology Co., Ltd. [animal licence number: SCXK (Yu) 2022-0005]. The rats were raised under controlled pathogen-free conditions with a 12 h light/dark cycle, and temperature and humidity of (23 ± 2) °C and (40–60) %, respectively. The rats had unrestricted access to standard dry rat food and purified water. All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics and Welfare Special Committee of the Academic Committee of Chongqing University of Technology (2024 Research Review No. 045). The handling of rats during the experimental process was performed in accordance with the GB/T 35,892 − 2018 “Guidelines for Ethical Review of Experimental Animal Welfare” and “Guidelines for the Feeding Management and Use of Experimental Animals” (8th Edition), the handling of rats during the experimental process and the study was reported following the ARRIVE guidelines.

Experimental grouping

Seventy rats were randomly divided into five groups, with 14 rats in each group, as follows:

Control group

The rats were not subjected to any treatment (data are not shown in results as no significant differences were observed with the Sham Group).

Sham group

Rats received anesthesia and craniotomy without any impact on the brain, and no drug injection was administered after the suturing of the scalp.

TBI group

Rats that received TBI, without drug injection after scalp suturing (data are not shown in results as no significant differences were observed with the TBI + Saline Group).

TBI + Saline (TBI-NS) group

Rats receiving TBI were immediately administered a single intraperitoneal injection of physiological saline after scalp suturing, with the injection dose referring to the bevacizumab treatment group.

TBI + Bevacizumab (TBI-Beva) group

Rats received TBI, and after scalp suturing, they were immediately administered a single intraperitoneal injection21 of bevacizumab (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, 100 mg (4 ml) / bottle). Our other TBI experiments showed that the therapeutic effect of bevacizumab administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 15 mg/kg was superior to that of 5 or 10 mg/kg. Therefore, the injection dose of bevacizumab used in this study was 15 mg/kg.

Establishment of the moderate TBI model

After intraperitoneal injection of 2.5% tribromoethanol (1 mL/100 g) to anesthetize the rats, the head was disinfected and prepared for surgical intervention. An incision approximately 2.0 cm of the opening skin along the midline, and a handheld electric grinder (BOSCH, DREMEL) with a 5 mm drill bit and a speed of 1000 rpm, drill the skull 2.5 mm behind the anterior fontanelle and 2.5 mm to the left of the sagittal line. Subsequently, mosquito-style vascular forceps to drill a bone window with a diameter of approximately 5 mm to ensure the integrity of the dura mater. The rats were fixed in a prone position and subjected to traumatic brain injury using a TBI-0310 (American PSI) device. A brain injury model was established based on the improved Feeney’s method22, with an impact velocity of 2.5 m/s, depth of 4.0 mm, residence time of 0.1 s, impact tip diameter of 4 mm, and damage to both cortex and medulla. After impacting the brain tissue, the dura mater was repositioned, the scalp sutured, and the surgical area was disinfected and marked. The rat was then placed on a thermal blanket to maintain warmth and subsequently transferred to the feeding room upon regaining consciousness.

Pathomorphological observation

After 24 h, three rats were randomly selected from each group and euthanized by administering an overdose of 2.5% tribromoethanol via intraperitoneal injection, resulting in unconsciousness, followed by cardiac perfusion, which led to subsequent death. The brain tissue was stripped and fixed at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde. After routine paraffin embedding, a 5 μm coronal section was cut, followed by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. Optical microscopy (BX53, Olympus) was used to capture images (magnification, ×100 and × 400), and at least two regions (periphery of the necrotic core) were analysed per rat, for a total of 6 regions (n = 6).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation

After 24 h, three rats were randomly selected from each group, and TP area brain tissue was taken within 1–3 min, with a size of approximately 2 mm×2 mm×2 mm, fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the dark. The samples were then dehydrated using ethanol and 100% acetone at room temperature. After the slices were embedded, they were stained with 2% uranium acetate saturated with 2.6% lead citrate. Images were analysed and collected using a transmission electron microscope (HT7800, Hitachi). At least two regions (periphery of necrotic core) were analysed per rat, for a total of 6 regions (n = 6).

Double-labeling Immunofluorescence (IF) observation

After 24 h, three rats were selected from each group, and their brain tissues were embedded in paraffin and sliced. After antigen repair, serum was blocked and a primary antibody against AQP4 (1:1000; product number: GB11529; Servicebio), GFAP (1:500; product number: GB12090; Servicebio) and VEGF (1:200; product number: GB15165; Servicebio) were added, which were subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS at pH 7.4, CY3-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:300; product number: GB21403; Servicebio), Alexa Fluor 488-labelled goat anti- mice IgG (1:400; product number: GB25301; Servicebio) were respectively added dropwise, and the samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark. The nuclei were stained with DAPI, spontaneous fluorescence of the tissue was quenched, and the slides were sealed. The slices were scanned using the Pannoramic 250FLASH system (3DHISTECH, Hungary). Discontinuous fields of view in the TP were randomly selected using the Case Viewer 2.4 software. Then, the distribution of AQP4 in the vascular basement membrane and glial cell membrane were counted. The entire image was used as the region of interest, and the intensity of protein staining was measured using ImageJ. At least two regions (periphery of necrotic core) were analysed per rat, for a total of 6 regions (n = 6).

Western blot experimental analysis

After 24 h, five rats in each group were selected from the TP area brain tissue, and the total protein of tissue cells was extracted using RIPA lysis solution. The protein concentration was measured using a BCA protein quantitative detection kit (Servicebio). Add 5* reducing protein loading buffer and denature the protein in a boiling water bath. After SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane, which was subsequently sealed with nonfat milk at room temperature. Primary antibody (immune rat AQP4-IgG 1:1000, 34 kDa) was added and the samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C. The membrane was incubated at room temperature with an anti-IgG-horseradish peroxidase antibody and eluted quickly with TBST. The luminescence reaction was performed using a mixed ECL luminescent liquid, the samples were exposed to a chemiluminescence instrument (6100, CLINX), and the original images were saved. The target bands were standardized to the corresponding β-actin band using ImageJ software for data analysis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0, and all data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro-Wilk test and homogeneity of variance test were used to process the data. When the data conformed to a normal distribution and the homogeneity of variance was consistent, one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests were used to compare the differences inter group comparison. When the homogeneity of variance was inconsistent, the Kruskal-Wallis or Welch tests were used for comparison inter group comparison. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the author used [ChatGPT] in order to [improve texts for readability]. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Results

Bevacizumab regulates the expression levels of VEGF

We assessed the efficacy of bevacizumab in modulating VEGF expression using IF. Compared that with in the sham group, the expression levels of VEGF were markedly increased in the TBI-NS group (P < 0.001; Fig. 1, A and B). Furthermore, the expression levels of VEGF in the TBI-Beva group were significantly lower than those in the TBI-NS group (P < 0.01; Fig. 1, B and C). The results indicated that bevacizumab may reduce the expression of VEGF after TBI.

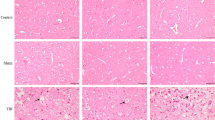

Pathological changes in the TP after bevacizumab treatment

To assess the effect of bevacizumab on brain edema in the TP, HE was employed to observe morphological changes in brain edema. No abnormalities were observed in the Sham group (Fig. 2, A and A1). Twenty-four hours post-TBI, examination under a light microscope revealed endothelial swelling, narrowing of the vascular lumen, and widening of the perivascular space in the TP, along with punctate hemorrhagic lesions and an expanded intercellular interstitial space. The tissue structure appeared disordered, exhibiting a grid-like pattern with faint eosin staining, consistent with vasogenic edema. Glial cells showed significant enlargement and deformation, including hollow or balloon-like changes, indicative of intracellular edema (Fig. 2, B and B1). After bevacizumab treatment, both vasogenic and intracellular edema were significantly reduced, and the disorganized intercellular matrix was partially restored (Fig. 2, C and C1), indicating that bevacizumab effectively mitigates brain edema after TBI.

TEM observation in the TP after bevacizumab treatment

The ultrastructure was observed using TEM before and after bevacizumab treatment. The results showed the chromatin of glial cells was evenly distributed, the BBB basement membrane was continuous, and the mitochondria were not swollen in the sham group (Fig. 3, A, D and D1). After TBI, swollen and deformed endothelial cells in the BBB, with rough and discontinuous basement membrane edges, some exhibiting visible fractures. Additionally, the foot processes of glial cells were swollen and distorted. Notable deep staining and, pyknosis of the nucleus, chromatin condensation at the nuclear periphery, partial rupture of the nuclear membrane, balloon-like changes in organelles (especially mitochondria), and expansion of the endoplasmic reticulum were also observed, further confirming the presence of intracellular edema (Fig. 3, B, E and E1).

After bevacizumab treatment, both vasogenic and intracellular edema were significantly reduced, a reduction in chromatin aggregation, the swelling of mitochondria and blood vessels was alleviated, and the structure of the BBB was also improved (Fig. 3,C, F and F1).

TEM images of brain tissue from the TP region. The ultrastructural changes in the TP in TBI-NS groups, deep staining and pyknosis of the nucleus, the water content in the cytoplasm increased, the swelling of mitochondria, blood vessels and glial cells, the basement membrane of BBB was thickened. Bevacizumab reduced edema and stabilized the structure of the basement membrane (○:chromatin; Blue →: nuclear pyknosis, nuclear membrane rupture; blue *: chromatin aggregation at the edge; red ◀: mitochondrial swelling).

Bevacizumab regulates the expression levels AQP4

We assessed the expression levels of AQP4 in the TP after bevacizumab treatment for TBI using Western blot (Fig. 4, A-A1). The results revealed ,,that the expression levels of AQP4 were significantly higher in the TBI-NS groups (3.62 ± 0.72) compared to the sham group (P < 0.001). Notably, the expression of AQP4 was significantly reduced in the TBI-Beva group (1.33 ± 0.20) compared to the TBI-NS group (P < 0.001), indicating that bevacizumab inhibits AQP4 expression after TBI.

Bevacizumab regulates the edistribution of AQP4

We examined the protein expression of AQP4 and the astrocyte marker GFAP in the brain using double-labeling IF. The results showed that the expression of AQP4 and GFAP increased after TBI (Fig. 5, B, B1 and B2). After treatment with bevacizumab, the expression of AQP4 and GFAP was reduced(Fig. 5, C, C1 and C2). The expression of AQP4 was also confirmed by Western blot.

We examined the distribution of AQP4 in the TP using double-labeling IF. In the sham group, AQP4 was primarily localized around the vascular basement membrane, with a smaller amount present at the glial cell membrane, with a ratio of 2.5:1 (Fig. 5, A, A1 and A2). Twenty-four hours after TBI, a noticeable shift in AQP4 distribution was observed in the TBI group, with a marked increase in AQP4 expression around the glial cell membrane, surpassing its distribution around the vascular basement membrane (Fig. 5, B, B1 and B2). After bevacizumab treatment, the amount of AQP4 around the glial cell membrane decreased (Fig. 5, C, C1 and C2), suggesting that bevacizumab inhibits the altered distribution of AQP4 after TBI.

Discussion

Our preliminary experimental research confirmed the presence of TP after TBI, which serves as a transitional zone between the central traumatic necrotic core and peripheral normal tissue11. In the absence of intervention, the central necrotic area gradually increased over time. After 24 h of injury, the volume of necrotic tissue may increase to 400% of the initial injury volume8. Timely and effective intervention can restore normal brain tissue in the TP and is regarded as a key target for clinical treatment4,8,23. Brain edema is one of the primary pathological changes in the TP and is characterized by an increase in the water content in the intercellular or extracellular spaces of the brain tissue, leading to organ swelling24. Post-TBI brain edema mainly includes vasogenic and intracellular edema, which play crucial roles in the severity and prognosis of injury25. Vasogenic edema and intracellular edema increase and decrease with time, and at 24 h after TBI, they are mixed types of brain edema dominated by intracellular edema26. Brain edema can induce ischemia and hypoxia in brain cells, intracranial hypertension, and cerebral herniation, exacerbating secondary damage to TP, and is an important reason for the high mortality and disability rates of TBI27. Therefore, inhibiting brain edema is a feasible approach to alleviate the secondary damage caused by TP.

Bevacizumab is widely used as an anti-angiogenic agent in tumor therapy and is beneficial for treating edema around tumors, especially radiation-induced brain edema20,28,29. However, there are few reports on whether brain edema in the TP is affected by bevacizumab, and this study fills this gap. After TBI, complex pathological and physiological changes occur in the TP, and the early stage is critical for TBI treatment30. Therefore, we chose the immediate method of administration after TBI. Genovese et al.31 suggested, through an indirect method of brain tissue water quantification, that bevacizumab can reduce brain edema in TBI-induced brain tissue, but these studies lacked pathological confirmation and did not discuss the specific classification of brain edema. The results of this study showed that both vasogenic and intracellular edema were significantly aggravated 24 h after TBI, mainly characterized by intracellular edema, consistent with previous research results11. After bevacizumab treatment, both vasogenic and intracellular edema in the TP significantly improved, with a significant decrease in intracellular edema observed, this result is consistent with the reports by Ai et al.9.Therefore, we believe that bevacizumab has a therapeutic effect on cerebral edema in the TP.

AQP4 is the most important aquaporin in the central nervous system and is a key regulatory factor in water metabolism32. AQP4 mediates the free transmembrane transport of water molecules, causing osmotic pressure imbalance and inducing brain edema33. The expression of AQP4 is closely related to the severity of brain edema, and its regulation reflects the body’s defense response after trauma3,34. Vasogenic edema is the main type of early traumatic brain edema characterized by BBB injury, and the downregulation of AQP4 expression can alleviate vasogenic edema. Damage and increased permeability of the BBB lead to upregulation of AQP4 expression, which can induce intracellular edema. AQP4 expression has two peaks at 24 h and 72h26,35,36. The combination of vasogenic and intracellular edema exacerbates traumatic brain edema.

As mentioned earlier, bevacizumab can alleviate cerebral edema in the TP. Therefore, it is unclear whether its mechanism of action is related to AQP4. This study showed that the expression of AQP4 in the TP was upregulated after TBI, indicating that AQP4 is associated with brain edema, which is consistent with previous reports26. After bevacizumab treatment, the expression level of AQP4 decreased, and brain edema improved. Bevacizumab can alleviate TBI-induced brain edema by inhibiting AQP4 expression, and is an effective method for treating brain edema after TBI.

GUAN et al.30,37 demonstrated that AQP4 siRNA can alleviate traumatic brain edema by reversing the polarity of AQP4 after TBI in rats, and has therapeutic effects on brain edema after TBI. Under normal circumstances, AQP4 exhibits a polar distribution, with AQP4 mainly distributed on endothelial cells and glial cell foot processes of the BBB, whereas only a small amount is expressed on the glial cell membrane, with a ratio of approximately 12:337. The polarization distribution of AQP4 is closely related to cerebral edema38. After TBI, AQP4 undergoes depolarization, also known as polarity reversal, characterized by decreased expression of foot processes in astrocytes around blood vessels and increased expression in the glial cell membrane. The reversal of AQP4 polarity is a direct cause of changes in the type and degree of brain edema. The distribution of AQP4 in the BBB structure decreased, reducing water leakage from blood vessels to interstitial spaces and alleviating vasogenic edema. The increased distribution of AQP4 on the glial cell membrane exacerbates intracellular edema, diluting and protecting cells from harmful substances to a certain extent. The polarity reversal stabilizes at 24 h, at which point the degree of intracellular edema reaches its peak26,37. Therefore, dysregulation of AQP4 is an important cause of brain edema after TBI, and inhibiting the reversal of AQP4 polarity is beneficial in alleviating brain edema. Our study shows that under normal circumstances, AQP4 is only expressed in small amounts and mainly distributed around the vascular basement membrane. After TBI, AQP4 is more distributed on the glial cell membrane than around the vascular basement membrane, which is consistent with previous reports by LU et al.37,39,40. After treatment with bevacizumab, not only did the expression level of AQP4 decreased, but the number of cells distributed on the glial cell membrane also decreased, polarity reversal was inhibited, and brain edema in the TP improved. This phenomenon indicates that bevacizumab can alleviate brain edema after TBI by inhibiting AQP4 expression.

Early bevacizumab treatment has great potential for reducing cerebral edema in the TP. However, additional research is needed to evaluate the mechanism by which bevacizumab regulates AQP4, which may help reveal new potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for TBI.

This study had some limitations. First, this study only used male rats. The influence of physiological processes, such as menstruation in female rats on the experimental results has not been ruled out. Future should also consider this impact. Second, there is a lack of research on the systemic effects of bevacizumab, and further observation of its side effects is required. Therefore, the clinical application of bevacizumab in TBI patients needs further investigation. This study investigated the effect of bevacizumab on brain edema from the perspective of AQP4 in TBI animal models, with the aim of providing theoretical research and experimental guidance for the application of bevacizumab in TBI treatment.

Conclusion

In the rat TBI model, bevacizumab reduces cerebral edema in the TP after TBI by regulating the expression and polarized distribution of AQP4. This modulation helps mitigate TBI-induced secondary brain injury. Bevacizumab holds potential as a therapeutic agent for treating TBI, and this study provides an experimental foundation for developing genetic-based drugs for clinical TBI treatment.

Data availability

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Susanto, M. et al. The neuroprotective effect of Statin in traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. X. 19, 100211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wnsx.2023.100211 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. WTAP participates in neuronal damage by protein translation of NLRP3 in an m6A-YTHDF1-dependent manner after traumatic brain injury. Int. J. Surg. 110, 5396–5408. https://doi.org/10.1097/js9.0000000000001794 (2024).

Lu, Q. et al. Minocycline improves the functional recovery after traumatic brain injury via Inhibition of aquaporin-4. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 441–458. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.64187 (2022).

Li, C. et al. CBF oscillations induced by trigeminal nerve stimulation protect the pericontusional penumbra in traumatic brain injury complicated by hemorrhagic shock. Sci. Rep. 11, 19652. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99234-8 (2021).

Barker, S., Paul, B. D. & Pieper, A. A. Increased risk of Aging-Related neurodegenerative disease after traumatic brain injury. Biomedicines 11, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11041154 (2023).

Carteri, R. B. Mitochondria as a therapeutic target: focusing on traumatic brain injury. J. Integr. Neurosci. 24, 25292. https://doi.org/10.31083/jin25292 (2025).

Harish, G. et al. Characterization of traumatic brain injury in human brains reveals distinct cellular and molecular changes in contusion and Pericontusion. J. Neurochem. 134, 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13082 (2015).

da Silva Meirelles, L., Simon, D., Regner, A. & Neurotrauma The crosstalk between neurotrophins and inflammation in the acutely injured brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18051082 (2017).

Ai, L., Xin, C., Usman, M., Zhu, Y. & Lu, H. Effect of bevacizumab on traumatic penumbra brain edema in rats at different time points. Tissue Barriers. 12, 2292463. https://doi.org/10.1080/21688370.2023.2292463 (2023).

Esteban-Zubero, E., García-Muro, C. & Alatorre-Jiménez, M. A. Fluid therapy and traumatic brain injury: A narrative review. Med. Clin. (Barc). 161, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2023.03.003 (2023).

Ren, H. & Lu, H. Dynamic features of brain edema in rat models of traumatic brain injury. Neuroreport 30, 605–611. https://doi.org/10.1097/wnr.0000000000001213 (2019).

Chen, J., Xia, Q. & Lu, H. Changes in AQP4 expression and the pathology of injured cultured astrocytes after AQP4 mRNA Silencing. Neuropsychiatry 07, 640–646. https://doi.org/10.4172/Neuropsychiatry.1000232 (2017).

Toader, C. et al. From homeostasis to pathology: decoding the multifaceted impact of Aquaporins in the central nervous system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241814340 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Efficacy and safety of intraperitoneal bevacizumab combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with ovarian cancer and peritoneal effusion and the effect on serum LncRNA H19 and VEGF levels. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 43, 2204940. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2023.2204940 (2023).

Kocapınar, Y., Kaplan, F. B., Demirciler Sönmez, A. & Açıkalın, B. Evaluation of the efficacy of anti-vascular endothelial growth factors in diabetic macular edema with retinal inner and outer layers disorganization. Acta Diabetol. 60, 1391–1398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-023-02121-z (2023).

Sirakaya, E., Kilic, D. & Aslan Sirakaya, H. Comparison of intravitreal ranibizumab, Aflibercept and bevacizumab therapies in diabetic macular edema with serous retinal detachment. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 33, 1459–1466. https://doi.org/10.1177/11206721221144797 (2023).

Bai, X., Feng, M., Ma, W. & Wang, S. Predicting the efficacy of bevacizumab on peritumoral edema based on imaging features and machine learning. Sci. Rep. 15, 15990. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00758-0 (2025).

Mustafayev, Z. Clinical and radiological effects of bevacizumab for the treatment of radionecrosis after stereotactic brain radiotherapy. BMC Cancer. 24, 918. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12643-6 (2024).

Alsahlawi, A. K. et al. Bevacizumab in the treatment of refractory brain edema in High-grade glioma. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 46, e87–e90. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000002792 (2024).

Tijtgat, J. et al. Low-Dose bevacizumab for the treatment of focal radiation necrosis of the brain (fRNB): A Single-Center case series. Cancers (Basel). 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15092560 (2023).

Deng, Z. et al. Astrocyte-derived VEGF increases cerebral microvascular permeability under high salt conditions. Aging (Albany NY). 12, 11781–11793. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.103348 (2020).

Feeney, D. M., Boyeson, M. G., Linn, R. T., Murray, H. M. & Dail, W. G. Responses to cortical injury: I. Methodology and local effects of contusions in the rat. Brain Res. 211, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(81)90067-6 (1981).

Kn, B. P. et al. An end-end deep learning framework for lesion segmentation on multi-contrast MR images-an exploratory study in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 61, 847–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-022-02752-4 (2023).

Freire, M. A. M. et al. Cellular and molecular pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury: what have we learned so far? Biology (Basel). 12, 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12081139 (2023).

Minchew, H. M. et al. Comparing imaging biomarkers of cerebral edema after TBI in young adult male and female rats. Brain Res. 1789, 147945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2022.147945 (2022).

Zhang, C., Chen, J. & Lu, H. Expression of aquaporin-4 and pathological characteristics of brain injury in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Mol. Med. Rep. 12, 7351–7357. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2015.4372 (2015).

Kirsch, E., Szejko, N. & Falcone, G. J. Genetic underpinnings of cerebral edema in acute brain injury: an opportunity for pathway discovery. Neurosci. Lett. 730, 135046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135046 (2020).

Meng, X. et al. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab treatment for refractory brain edema: case report. Med. (Baltim). 96, e8280. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000008280 (2017).

Garcia, J. et al. Bevacizumab (Avastin®) in cancer treatment: A review of 15 years of clinical experience and future outlook. Cancer Treat. Rev. 86, 102017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102017 (2020).

Guan, Y., Li, L., Chen, J. & Lu, H. Effect of AQP4-RNAi in treating traumatic brain edema: Multi-modal MRI and histopathological changes of early stage edema in a rat model. Exp. Ther. Med. 19, 2029–2036. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2020.8456 (2020).

Genovese, T. et al. Role of bevacizumab on vascular endothelial growth factor in Apolipoprotein E deficient mice after traumatic brain injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 4162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23084162 (2022).

Mohaupt, P., Vialaret, J., Hirtz, C. & Lehmann, S. Readthrough isoform of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) as a therapeutic target for alzheimer’s disease and other proteinopathies. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01318-2 (2023).

Salman, M. M. et al. Emerging roles for dynamic aquaporin-4 subcellular relocalization in CNS water homeostasis. Brain 145, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awab311 (2022).

Xiong, A. et al. Inhibition of HIF-1α-AQP4 axis ameliorates brain edema and neurological functional deficits in a rat controlled cortical injury (CCI) model. Sci. Rep. 12, 2701. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06773-9 (2022).

Zusman, B. E., Kochanek, P. M. & Jha, R. M. Cerebral edema in traumatic brain injury: a historical framework for current therapy. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 22, 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-020-0614-x (2020).

Lu, H., Lei, X. Y., Hu, H. & He, Z. P. Relationship between AQP4 expression and structural damage to the blood-brain barrier at early stages of traumatic brain injury in rats. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 126, 4316–4321. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20131139 (2013).

Lu, H., Zhan, Y., Ai, L., Chen, H. & Chen, J. AQP4-siRNA alleviates traumatic brain edema by altering post-traumatic AQP4 Polarity reversal in TBI rats. J. Clin. Neurosci. 81, 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.09.015 (2020).

Sun, C. et al. Acutely inhibiting AQP4 with TGN-020 improves functional outcome by attenuating edema and Peri-Infarct astrogliosis after cerebral ischemia. Front. Immunol. 13, 870029. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.870029 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Lost polarization of Aquaporin4 and dystroglycan in the core lesion after traumatic brain injury suggests functional divergence in evolution. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015 (471631). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/471631 (2015).

Eidsvaag, V. A., Enger, R., Hansson, H. A., Eide, P. K. & Nagelhus, E. A. Human and mouse cortical astrocytes differ in aquaporin-4 polarization toward microvessels. Glia 65, 964–973. https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.23138 (2017).

Funding

This study was funded by the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (No. KJZD-K202301105), the Technology Innovation and Application Development Project of Shapingba District Science and Technology Bureau (No. 202345), and the Research Project of Chongqing Pharmaceutical Vocational Education Group (No. CQZJ202308).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiao-Yi Lin and Hong Lu conceived and designed the experimental research. Xiao-Yi Lin conducted the experiments. Xiao-Yi Lin and Usman Muhammad analysed the experimental data and drafted and wrote the manuscript. Hong Lu and Dai-Xiang Huang reviewed and edited the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics and Welfare Special Committee of the Academic Committee of Chongqing University of Technology (2024 Research Review No. 045). GB/T 35892 − 2018 “Guidelines for Ethical Review of Experimental Animal Welfare” and “Guidelines for the Feeding Management and Use of Experimental Animals” (8th Edition) guide the handling of rats during the experimental process.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, XY., Usman, M., Huang, DX. et al. Pathological changes and aquaporin-4 expression after bevacizumab treatment of traumatic penumbra in the rat brain. Sci Rep 15, 40253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24151-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24151-z