Abstract

In the smartphone manufacturing industry, detecting cover glass defects is crucial to product quality. To address this, this paper proposes DY-YOLO, an enhanced YOLOv8-based model for defect detection on smartphone cover glass. The model improves the accuracy and efficiency of detecting defects on cover glass surfaces in complex production environments. Specifically, the proposed Dynamic-Large Separable Kernel Attention (Dynamic-LSKA) module effectively suppresses interference from complex backgrounds, such as glass reflections, thereby reducing false detections. DY-YOLO integrates several innovations: the Dynamic-LSKA module for enhanced multi-scale perception, the Dynamic-C2f module for enhanced feature extraction, and the Advanced Screening Feature Bidirectional Path Aggregation Network (HSF-BPAN) for efficient fusion of advanced screening features. Additionally, DySample is used as a lightweight dynamic up-sampler to reduce computational cost. Extensive evaluations were conducted using two public benchmarks, Mobile Phone Screen Surface Defect Dataset (MSD) and Smartphone Screen Glass Dataset (SSGD). Results demonstrate that, compared to the baseline model, the proposed method achieves improvements of 1% and 0.6% in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, respectively, on MSD, reaching 99.3% and 70.9%. On SSGD, the improvements are 4.8% and 2.6%, reaching 46% and 20.2%, respectively, surpassing the state-of-the-art methods in detection accuracy. Moreover, DY-YOLO achieves an excellent balance between performance and efficiency. With a parameter count comparable to the baseline but 33.3% lower computational cost, the model achieves an inference speed of 121.8 FPS, demonstrating its strong potential for real-time edge deployment on production lines. These results confirm the model’s effectiveness and potential for industrial applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of the global smartphone industry, smartphones have become an indispensable part of daily life1. The external surface of modern smartphone screens is primarily covered by glass panels. The surface quality of these glass panels directly affects the display performance, touch sensitivity, imaging quality, and optical sensitivity of sensors2. However, during production, smartphone glass covers may develop various defects, such as scratches, cracks, and chips, which significantly impact product quality and production efficiency.

Due to the high reflectivity and transparency of glass covers, it is challenging for the human eye, limited by physiological structure, to directly observe these defects. With advancements in machine vision imaging and intelligent computer algorithms, vision inspection systems have demonstrated excellent performance in the industrial surface quality inspection of electronic products such as smartphone glass covers. These systems can automatically identify surface defects, providing real-time statistics and feedback, thereby enhancing inspection efficiency and speed3,4.

However, for such systems to be viable in a high-volume manufacturing setting, they must overcome two critical challenges simultaneously. First, they require exceptional robustness to avoid costly false alarms or missed detections caused by complex backgrounds like reflections and fingerprints. Second, and equally important, is the demand for extremely high inference speed. On a high-speed smartphone assembly line, each glass cover passes the inspection station in a matter of milliseconds. Any detection algorithm that cannot keep pace with this throughput would become a bottleneck, leading to the passage of defective products and causing significant batch waste. Therefore, an ideal detection model must achieve an optimal balance between high accuracy and real-time performance.

However, the varying scales of glass defects present significant challenges for algorithms. Deep learning classification and detection methods, represented by CNNs, have adaptive feature extraction and decision-making capabilities. They overcome the reliance on manual intervention seen in traditional methods such as image denoising and threshold segmentation, which enhances accuracy and generalization when dealing with random production defects. As a result, deep learning is widely applicable, offering high precision and efficiency in detection5,6,7,8.

For industrial defect detection and classification needs, object detection methods like YOLO and FCOS9 adopt end-to-end designs, simplifying the detection process and improving efficiency and speed, making them widely used in industrial inspection. The YOLO series10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 has gained attention for its real-time performance and efficiency. We select YOLOv817 as our baseline model due to its well-established architecture that strikes an excellent balance between high accuracy and inference speed, making it a prevalent and reliable choice for industrial vision tasks. Compared to its predecessors, YOLOv8 features optimized network structures and training strategies that significantly enhance both accuracy and speed over models like YOLOv312 and YOLOv514. It also offers more refined feature extraction and greater training stability compared to YOLOv918, which is crucial for consistently identifying minor defects. Although newer versions like YOLOv1120 and YOLOv1221 perform well in certain scenarios, YOLOv8’s mature ecosystem, proven performance, and specific improvements in data augmentation and loss function optimization enhance its stability and generalization in complex backgrounds, making it a robust foundation for our research on glass cover defect detection.

However, YOLOv8 also faces challenges in detecting smartphone cover defects. One issue is that complex backgrounds can lead to false positives or missed detections. For instance, reflections or fingerprints on the cover surface may interfere with the model’s recognition capabilities, especially when the background and defects have similar colors or textures. Additionally, the variability in defect scales is a challenge. Defects on smartphone covers can range from tiny scratches to large cracks, and YOLOv8 may struggle to maintain high precision across these extreme scales.

To address these limitations and meet the stringent requirements of industrial deployment, this paper proposes DY-YOLO. Our model is designed not only to enhance detection accuracy against complex backgrounds and multi-scale defects but also to maintain a high inference speed critical for production lines. With an achieved speed of 121.8 FPS, DY-YOLO ensures millisecond-level response, effectively preventing bottlenecks and batch quality issues, thereby demonstrating a superior balance of accuracy and practicality. Meanwhile, recent studies have also shown that lightweight CNNs can achieve efficient real-time performance in industrial applications, such as instrument indication acquisition, which further motivates our pursuit of lightweight and practical design22. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

To address challenges such as the complexity of backgrounds and scale variability in smartphone cover glass defects, we propose an innovative DY-YOLO model. This model integrates dynamic convolution and multi-scale feature path aggregation techniques, requiring lower computational power and making it more suitable for deployment on resource-constrained mobile devices.

-

(2)

For the issues of complex environmental interference, such as background reflections and indistinct defect features, we designed a Dynamic Large Kernel Attention (Dynamic-LSKA) and Dynamic-C2f module based on dynamic convolution structures. These enhance the model’s ability to resist environmental interference and accurately capture critical features in low-contrast defects by improving the adaptability and expressive power of multi-scale feature representation and extraction.

-

(3)

To tackle the problem of defect scale variability, we propose an Advanced Screening Feature Bidirectional Path Aggregation Network (HSF-BPAN). This network enhances the focus on small-scale objects while maintaining high-level semantic understanding of large-scale objects, addressing feature loss issues caused by deeper network structures and improving defect feature representation.

Related work

In recent years, with the rapid development of computer vision technology, the use of vision-based techniques for defect detection and classification of smartphone cover glass has become a research hotspot23.

Traditional vision-based detection methods primarily rely on image processing techniques or a combination of these with machine learning. Researchers have explored various feature extraction and classification methods. Kong et al.24 utilized the Sobel edge detection operator to enhance the edges of abnormal defects and combined it with an SVM classifier25 for a secondary judgment to improve accuracy. Yang et al.26 developed an automatic detection system that used backlight imaging to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, employed an adaptive binarization algorithm for high real-time performance, and designed multi-dimensional feature vectors for defect classification to meet the speed and accuracy requirements of industrial scenarios. Li et al.27 proposed a highly generalizable region of interest (ROI) extraction algorithm to handle the diversity of smartphone screens, introduced clustering algorithms to avoid false positives and missed detections, and defined detection criteria combined with multilayer perceptrons and deep learning classification algorithms. Jian et al.28 proposed an improved defect recognition and segmentation algorithm for smartphone cover glass, which used a contour-based registration method to address misalignment issues and combined subtraction and projection (CSP) methods to achieve defect recognition while mitigating the effects of lighting fluctuations. Turko et al.29 focused on the reflection issues during smartphone cover glass image acquisition, developing an automatic detection system that utilized a ring lighting system to illuminate glass samples from different directions, with the camera capturing dark-field images to highlight defects. However, traditional methods rely on predefined algorithms and features, which may struggle to capture defects of varying scales in complex environments.

Due to the advantages of deep learning models in automatic feature learning and strong expressive capabilities, they are better suited to capturing defects of varying scales and handling subtle and complex image features in challenging environments30.

Consequently, more researchers have been applying deep learning models for industrial defect detection in recent years. For instance, Lei et al.31 proposed an end-to-end screen defect detection framework, including a scale-insensitive defect detection network (MSDDN) and a self-comparison-driven SCN network. This effectively addresses the issues of traditional methods relying on low-level features and sensitivity to scale and model, efficiently handling defects of various scales. Yang et al.32 tackled the inconsistency in manual smartphone screen defect detection by introducing a model based on YOLOv5s and Ghostbottleneck (Ghostbackbone), effectively overcoming problems associated with traditional machine learning. In addition, lightweight CNNs have been explored in other domains, such as ancient mural element detection and finger vein recognition, proving their effectiveness in balancing accuracy and efficiency33,34.

Among the studies most relevant to ours, several efforts have been made to adapt YOLO models specifically for glass defect detection. Mao et al.35 proposed Dy-YOLOv5s to address challenges like diverse defect morphologies. By incorporating attention modules and cross-layer connections, it enhances feature extraction. However, its feature fusion strategy may still be insufficient for effectively capturing the extreme scale variation between minute scratches and large cracks on glass surfaces. Zhou et al.36 introduced PGS-YOLO, based on YOLOv8n, which focuses on improving small object detection and model efficiency. While effective for small defects, PGS-YOLO does not explicitly address the interference from complex backgrounds, such as reflections and fingerprints, which are prevalent on highly reflective glass surfaces and often lead to false positives. Li et al.37 proposed a detection model based on PU-Faster R-CNN to address issues like obscure defect features and significant size differences. This model effectively extracts multi-scale defect feature information through a multi-scale feature extraction network, showing excellent performance on smartphone screen datasets.

In summary, while existing methods have made progress, a critical research gap remains in developing a model that simultaneously: (1) possesses strong anti-interference capabilities against complex glass backgrounds to reduce false detections, and (2) achieves efficient and adaptive multi-scale feature fusion for defects ranging from tiny to large. To bridge this gap, we propose DY-YOLO. Our model differentiates itself through targeted innovations: the Dynamic-LSKA module is designed to enhance multi-scale perception and suppress background interference (e.g., reflections), directly addressing the limitation of methods like PGS-YOLO. Furthermore, the HSF-BPAN structure is introduced for more efficient fusion of features across scales, improving the handling of scale variation, an area where models like Dy-YOLOv5s show room for improvement. By integrating these advancements, DY-YOLO aims to provide a more robust and accurate solution tailored for the specific challenges of cover glass defect detection.

Overall, although deep learning-based defect detection methods surpass traditional machine vision in terms of efficiency and accuracy, they still face challenges in practical industrial applications. Therefore, developing a robust, high-precision, and lightweight real-time detection system holds significant potential for practical applications.

Methods

Overall architecture of the DY-YOLO network

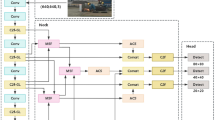

The overall architecture of DY-YOLO is illustrated in Fig. 1, which primarily consists of three core components: the Backbone, HSF-BPAN, and Head.

DY-YOLO adopts a multi-module collaborative Backbone structure: Dynamic-C2f enhances feature extraction, SPPF improves multi-scale feature representation, and Dynamic-LSKA captures global contextual information and adjusts feature weights, effectively boosting feature recognition and extraction capabilities in complex environments.

In the neck, the HSF-BPAN network is designed to achieve dual-path feature fusion through the Feature Selection and Path Aggregation modules. Additionally, the DySample38 upsampling method is incorporated to reduce computational overhead while preserving critical semantic information.

Finally, the feature maps generated by the collaborative efforts of the Backbone and HSF-BPAN are processed by the detection head, which decouples the results into defect classification and localization.

Dynamic convolution-based backbone network

Dynamic convolution module

Traditional convolution employs fixed convolutional kernel parameters, as shown on the left side in Fig. 2, whereas dynamic convolution39 dynamically generates convolutional kernel parameters based on input features through a weight generation network. This adaptive mechanism enables the model to adjust filters according to different inputs, thereby capturing richer features, as shown on the right side in Fig. 2.

Assume the input feature map is \(\:X\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{B\times\:{C}_{in}\times\:H\times\:W}\), where B is the batch size, \(\:{C}_{in}\) is the number of input channels, and H and W are the height and width of the feature map, respectively. First, global average pooling is applied to the input feature map X to extract global contextual information, as illustrated in Eq. (1):

Here, \(\:{X}_{pooled}\) is the global feature vector obtained through the global average pooling operation, which encapsulates the global information of the input feature map. Subsequently, dynamic weights \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\) are generated through a fully connected layer. Assuming there are K experts (i.e., K different convolution kernels) for each scale, this work generates a set of dynamic weights α for each scale, as illustrated in Eq. (2):

Here, \(\:{W}_{routing}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{B\times\:{C}_{in}}\) is the convolution kernel weight generation matrix, and \(\:{b}_{routing}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{K}\) is the bias term. \(\:\alpha\:\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{B\times\:K}\) is a matrix where each row \(\:\alpha\:=[{\alpha\:}_{b,1},{\alpha\:}_{b,2},\dots\:,{\alpha\:}_{b,K}]\) represents the scalar weights for the K experts generated for the b-th sample in the batch. The routing weights \(\:{\alpha\:}_{b,i}\) are normalized using the sigmoid function. This non-competitive normalization is chosen over alternatives like softmax to allow for the simultaneous activation of multiple experts, which enables a more flexible and composite feature representation—this proves particularly beneficial for capturing the complex and varied patterns of glass defects. This design fundamentally alters the kernel weighting in Eq. (3), promoting a collaborative fusion over a winner-takes-all selection. The resulting dynamic kernel becomes a balanced ensemble that adaptively integrates the strengths of multiple experts, which is crucial for capturing complex glass defects.

For the convolution experts, there are K expert kernels, with the weights of the i-th expert being \(\:{W}_{i}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{C}_{out}\times\:{C}_{in}\times\:{K}_{H}\times\:{K}_{W}}\). Each expert is also associated with a bias term \(\:{b}_{i}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{C}_{out}}\) . For each sample b in the batch, the dynamic convolution parameters are computed as the weighted sum of all expert parameters, where each expert’s kernel and bias are scaled by its corresponding scalar weight \(\:{\alpha\:}_{b,i}\), as illustrated in Eq. (4):

Where \(\:{W}_{i}\) represents the convolution kernel of the i-th expert, and \(\:{\alpha\:}_{b,i}\) is its associated sample-specific dynamic weight. Note that we employ Sigmoid for normalization, thus \(\:{\sum\:}_{\varvec{i}=1}^{\varvec{K}}{\alpha\:}_{b,i}\). This deliberate departure from the standard softmax constraint (which enforces a convex combination) allows for the simultaneous activation of multiple experts, enabling a more powerful and composite feature representation. This per-sample dynamic kernel and bias are then used to perform the convolution operation on the corresponding input features, as defined in Eq. (5):

Here, stride and padding are the hyperparameters of the convolution operation.

Dynamic-C2f module

To enhance the model’s capability in handling complex and variable input data, this paper introduces an improved feature extraction module named Dynamic-C2f, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The core innovation of this module lies in its incorporation of a dynamic convolution mechanism. By replacing standard convolutional layers within the bottleneck blocks, the module significantly augments the network’s feature modeling capacity and its adaptability to varying inputs.

The module employs two tailored variants of the dynamic bottleneck structure to address the distinct functional requirements of different network sections. A residual connection structure is adopted within the backbone network to facilitate efficient feature propagation and mitigate the gradient vanishing problem. Conversely, a non-residual structure is utilized in the neck network to prioritize superior multi-scale feature aggregation and the extraction of deeper semantic information.

The key configuration parameters of the module are detailed in Table 1, which specifies a kernel size of 3 for the dynamic convolutions and an expansion ratio of 0.5 within the bottleneck layers. The module processes input features by splitting and transforming them through multiple branches, where the dynamic convolutions adaptively adjust the convolutional kernel weights for each branch. Subsequently, the features from all branches are concatenated and fused to generate high-quality output, thereby providing more discriminative information for subsequent detection tasks.

Dynamic-LSKA module

To address issues such as background reflection and inconspicuous defect features in glass defect detection, drawing inspiration from applications in tasks like image segmentation40,41,42, we introduce dynamic convolution into the Large Separable Kernel Attention (LSKA) proposed by Lau et al.43, proposing a Dynamic Large Separable Kernel Attention (Dynamic-LSKA) module, as shown in Fig. 4. This module combines depthwise separable convolution with an attention mechanism to reduce computational complexity while maintaining performance. Placed at the end of the Backbone, it leverages the advantages of feature maps with rich high-level semantic information and low resolution, effectively focusing on key information, optimizing computational resource utilization, and improving detection performance and efficiency.

The Dynamic-LSKA module expands the receptive field by decomposing large convolutional kernels into horizontal and vertical depthwise convolutions and further enhances long-range dependency modeling through dilated convolution44. The module achieves multi-scale feature processing by sequentially applying two sets of depthwise dynamic convolutions with different parameters: first, a 1 × 3 and 3 × 1 convolution pair (jointly equivalent to a standard 3 × 3 kernel with a dilation rate of 1) for basic feature extraction; followed by a 1 × 5 and 5 × 1 dilated convolution pair with a dilation rate of 2 to effectively capture broader contextual information. The processed features then undergo fusion and channel integration via a 1 × 1 convolution, and finally, residual connections with the input are employed to improve training efficiency. The parameters for both the depthwise and dilated convolutional kernels are dynamically generated by the Dynamic Convolution module, as illustrated in Fig. 5. This design effectively suppresses interference from complex backgrounds, such as reflections, and enhances the ability to extract critical features.

The processing workflow of the Dynamic-LSKA module is as follows: The input features are first projected using a 1 × 1 convolution and activated with GELU before entering the Dynamic-LSKA Block. This module decomposes the 2D convolutional kernel into a cascade of 1D kernels. By utilizing dynamic convolution, it generates convolutional kernel weights based on the input features, performing both horizontal and vertical convolutions. This approach effectively reduces computational complexity and memory requirements. Finally, a 1 × 1 convolution is used to generate an attention map, which is then element-wise multiplied with the input features to produce the weighted output feature map.

High-level screening feature path aggregation network

To address the issue of varying defect scales, a hierarchical scale-based High-level Screening Feature Bidirectional Path Aggregation Network (HSF-BPAN) is proposed, as shown in Fig. 6. It consists of two main components: the Feature Selection Module and the Bidirectional Path Aggregation Module.

High-level screening features

To suppress the interference of irrelevant features and enhance the expression of key features, this paper designs an Advanced Feature Selection Module (HSF) to filter and weight features at different scales. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the input feature map is processed in the CSA module, which is divided into channel attention and spatial attention branches.

The channel attention branch concatenates global average pooling and max pooling, followed by Sigmoid activation to generate a channel attention map. This enhances critical channel information while suppressing redundant information. The spatial attention branch computes the mean and max values along the channel dimension, using Sigmoid activation to produce a spatial attention map that focuses on important spatial locations. This design employs distinct fusion strategies for channel and spatial dimensions, guided by their respective roles in feature representation. In the channel dimension, concatenating the outputs of average and max pooling provides a comprehensive descriptor for each channel, enabling more accurate feature recalibration. In the spatial dimension, combining mean and max values offers a richer spatial encoding by capturing both the most salient features and their supportive context, which is crucial for precise defect localization. This dual-branch structure effectively improves the model’s ability to distinguish features relevant to smartphone cover glass defects.

The channel and spatial attention maps are fused using element-wise multiplication. This design implements a gating mechanism where both attention types must “agree” to amplify a feature—only features deemed important in both the channel and spatial dimensions are strongly enhanced. While low attention values in either map can suppress features, this behavior is beneficial for filtering out background noise prevalent in glass surfaces. Furthermore, the use of Sigmoid activation, as opposed to Softmax, allows multiple channels and spatial locations to be activated simultaneously. This non-competitive normalization is crucial for detecting co-occurring defects without forcing a “winner-takes-all” suppression of useful but non-dominant features.

Finally, the results from the channel and spatial attention are fused using element-wise multiplication and then multiplied with the original input feature map. This results in a feature map with enriched feature expression and advanced semantic information.

Bidirectional path aggregation network (BPAN)

To effectively integrate the detailed information of high-resolution features with the global semantic information of low-resolution features and enhance feature interaction capabilities, we design a bidirectional feature aggregation path: top-down and then bottom-up. This is combined with dynamic upsampling and downsampling modules (HFF-D and HFF-U), as shown in Figs. 8 and 9. The HFF-U module uses DySample for upsampling to match feature dimensions, while the HFF-D module employs convolutional downsampling. Both utilize the CSA module for low-level feature filtering and the Dynamic-C2f module for feature enhancement.

Unlike traditional fixed interpolation strategies, DySample flexibly adjusts sampling positions by learning offsets, as depicted in Fig. 8. Assuming the input feature map is \(\:X\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{C\times\:{H}_{1}\times\:{W}_{1}}\), a linear layer with input and output dimensions of C and 2s2, respectively, generates offsets \(\:\vartheta\:\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{2{s}^{2}\times\:{H}_{2}\times\:{W}_{2}}\). Each sampling point is determined by “original point + offset”, generating coordinates for each point in the upsampled map before sampling to obtain the sampling set \(\:S\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{2\times\:{H}_{2}\times\:{W}_{2}}\), where the first dimension’s 2 represents the x and y coordinates. The Grid sample function uses the positions in S to generate a higher resolution feature map \(\:X{\prime\:}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{2\times\:{H}_{2}\times\:{W}_{2}}\) through bilinear interpolation.

While this dynamic mechanism introduces a modest computational overhead compared to non-parametric methods like standard bilinear interpolation—due to the lightweight linear layer for offset generation—it is justified by its significant advantages for our specific task. Fixed upsamplers apply a uniform process to all features, which can blur fine details and degrade the clarity of small, critical defects such as thin scratches. In contrast, DySample’s content-aware adaptability preserves sharp edges and intricate defect patterns by dynamically adjusting sampling positions based on feature context. This capability is essential for achieving high localization accuracy in glass defect detection, where the precise reconstruction of defect morphology directly impacts detection performance. The trade-off of a slight increase in computation for a substantial gain in feature fidelity and final accuracy is therefore both necessary and beneficial.

This adaptive upsampling mechanism effectively captures feature details and edge information, enhancing feature representation while reducing computational costs.

Experimental results and analysis

Dataset

In this paper, we conducted experiments on two publicly available standard datasets for smartphone cover glass defects: MSD45 and SSGD46.

The MSD dataset is sourced from the Intelligent Robotics Laboratory of Peking University. It contains three types of surface defects: oil stains, scratches, and spots, as shown in Fig. 10. Each defect type includes 400 images, resulting in a total of 1,200 images. To simulate industrial environments, these defects were artificially generated on glass cover plates and captured using an industrial camera with a resolution of 1920 × 1080. All defects were annotated at the pixel level using the LabelMe tool, ensuring both the authenticity of defect morphology and annotation accuracy. We reallocated the original test set to the validation set, resulting in a final dataset split of training: validation = 8:2.

The SSGD dataset, provided by Han et al., was collected using professional acquisition equipment and non-single workstations, specifically for academic research. This dataset primarily includes seven types of surface defects: crack, broken, spot, scratch, light-leakage, blot, and broken-membrane, covering common defects encountered in actual production processes, as shown in Fig. 11. To minimize environmental interference, images were captured with a line-scan industrial camera against a black background, while glass samples were placed on calibrated platforms to ensure consistent shooting angles. In total, the dataset comprises 2,504 images with a resolution of 1500 × 1000. Similarly, we divided the dataset into a training: validation ratio of 8:2.

Implementation details

We conducted our experiments on a dedicated hardware server, utilizing the PyTorch deep learning framework for algorithm development and model training. The hardware specifications include a 13th Gen Intel Core i5-13400 F processor, 32GB of RAM, and an RTX 4070 12GB GPU, ensuring a high-performance computing environment. For the training setup, all models uniformly adopted the SGD optimization algorithm with a batch size of 32. Mixed precision training was enabled, and the LambdaLR learning rate scheduler was used with an initial learning rate of 0.01 and weight decay of 0.0005. During training, Mosaic data augmentation was applied, but it was disabled in the final ten epochs.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the performance of the proposed smartphone cover glass defect detection model, the following key object detection metrics are used:

-

(1)

Precision: The ratio of true positive samples among those predicted as positive (targets). It is defined as illustrated in Eq. (6):

$$\:\begin{array}{c}Precision=\frac{TP}{TP+FP} \end{array}$$(6)where TP is True Positives (correctly predicted targets), and FP is False Positives (incorrectly predicted targets).

-

(2)

Recall: The ratio of correctly predicted positive samples among all actual positive samples. It is defined as illustrated in Eq. (7):

$$\:\begin{array}{c}Recall=\frac{TP}{TP+FN} \end{array}$$(7)where FN is False Negatives (missed targets).

-

(3)

mAP: Mean Average Precision is used to assess overall performance in multi-class detection tasks. mAP@0.5 is calculated at an IoU threshold of 0.5, while mAP@0.5:0.95 averages precision across multiple IoU thresholds (0.50 to 0.95). The mAP is calculated as illustrated in Eq. (8):

$$\:\begin{array}{c}mAP=\frac{1}{N}\sum\:_{i=1}^{N}A{P}_{i} \end{array}$$(8)where \(\:A{P}_{i}\) represents the AP score for the i-th class.

-

(4)

F1 Score: This metric balances precision and recall, calculated as illustrated in Eq. (9):

$$\:\begin{array}{c}F1=2\times\:\frac{Precision\times\:Recall}{Precision+Recall} \end{array}$$(9) -

(5)

FLOPs: Floating Point Operations measure the number of operations required for a single inference or training pass, indicating the model’s computational complexity.

-

(6)

Params: Refers to the total number of parameters that need to be trained in the network model.

Ablation study on different components

Table 2 describes the individual contributions of various modules integrated into the DY-YOLO model, evaluated on the MSD and SSGD datasets. These modules include Dynamic-C2f, Dynamic-LSKA, and HSF-BPAN. The best-performing results are highlighted in bold.

Table 2 demonstrates that enabling the Dynamic-C2f, Dynamic-LSKA, and HSF-BPAN modules simultaneously achieves the optimal performance on both the MSD and SSGD datasets. Here, Avg_Precision and Avg_Recall represent the average precision and average recall across all defect categories, respectively. With the integration of these modules, the average F1 score (Avg_F1) and mean average precision (mAP) progressively improve, highlighting the robust performance of module integration on smartphone cover glass defect datasets.

Beyond the overall performance metrics, a fine-grained ablation study was conducted to dissect the contribution of each proposed module to the detection of specific defect types. The results on the MSD and SSGD datasets, detailed in Tables 3 and 4 respectively, provide compelling evidence for the targeted effectiveness of our architectural innovations. The analysis reveals that the Dynamic-LSKA module exhibits specialized strength in handling defects plagued by complex backgrounds. This is most evident on the MSD dataset, where its introduction yields a distinct performance gain for “Oil” stains, a defect type often characterized by strong reflections and low contrast. The increase in mAP@0.5 for this category underscores the module’s success in enhancing multi-scale perception and suppressing irrelevant background interference, a capability that is less critical for more defined defects like scratches but crucial for minimizing false positives in realistic industrial settings. Conversely, the HSF-BPAN module demonstrates its primary advantage in managing the significant scale variation of defects, as showcased on the more diverse SSGD dataset. It achieves superior performance for the “broken” defect type, which typically presents as a large, irregular anomaly. This result directly validates the module’s design purpose of performing efficient, hierarchical fusion of advanced screening features, enabling the network to construct more robust representations for defects that span a wide range of scales, from tiny spots to extensive cracks. In contrast to the specialized roles of Dynamic-LSKA and HSF-BPAN, the Dynamic-C2f module serves as a backbone enhancer that provides a more balanced and generalized improvement across multiple defect categories. Its consistent contributions to both “Scr” and “Sta” on the MSD dataset, for instance, indicate that the dynamic feature extraction mechanism bolsters the model’s overall robustness and adaptability to diverse defect patterns, laying a solid foundation for the more specialized modules to build upon.

To determine the optimal kernel size for the dynamic convolution layer in the Dynamic-C2f module, we conducted comprehensive ablation studies on the MSD and SSGD datasets. As shown in Table 5, the results reveal a clear and consistent trend: a kernel size of 3 achieves excellent or highly competitive performance while maintaining minimal computational complexity.

To substantiate the selection of our Dynamic-LSKA module, we conducted a comparative analysis against several attention mechanisms, including Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE), Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM), a lightweight Deformable LKA, and the standard LSKA. Each module was integrated into our DY-YOLO architecture under consistent experimental settings. As shown in Table 6, our Dynamic-LSKA variant achieves the best overall performance-efficiency trade-off. It attains the highest accuracy on both datasets while maintaining the lowest computational cost among all compared variants. Specifically, on the challenging SSGD dataset, Dynamic-LSKA outperforms SE, CBAM, and Deformable LKA by 1.8%, 3.9%, and 2.5% in mAP@0.5, respectively, while requiring significantly fewer parameters and lower computational complexity. This demonstrates that our dynamic large kernel design provides superior feature representation capability for glass defect detection tasks, effectively capturing long-range dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency crucial for industrial deployment.

Comparative experiments with state-of-the-art methods

As shown in Tables 7 and 8, to evaluate the performance of DY-YOLO in smartphone cover glass defect detection tasks, we conducted comparative experiments with state-of-the-art methods on the MSD and SSGD datasets, respectively. In these tables, the best-performing results are highlighted in bold.

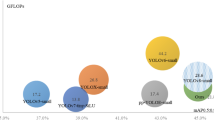

Based on the data analysis from Tables 7 and 8, the DY-YOLO model achieved the highest mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 scores on both datasets, reaching 99.3%, 70.9% and 46%, 20.2%, respectively. These results significantly surpass the baseline model, YOLOv8, while further reducing computational resource consumption by 33.3%.

Compared to the current state-of-the-art YOLO series detectors, DY-YOLO achieved the highest precision for the “Oil” and “Sta” categories on the MSD dataset, reaching 99.8% and 99.4%, respectively. On the SSGD dataset, DY-YOLO demonstrated significantly better AP scores for the “broken,” “blot,” and “broken-membrane” categories compared to other models. Additionally, the model showed strong competitiveness in other categories. The comparison of mAP scores during training with different methods is illustrated in Figs. 12 and 13. These results indicate that DY-YOLO exhibits excellent robustness and generalization capabilities in complex and diverse detection environments.

On the MSD and SSGD datasets, DY-YOLO outperformed YOLOv9 in mAP@0.5 by 0.6% and 10.1%, respectively, and surpassed YOLOv10 by 0.9% and 8.7%, respectively. A critical comparison with the latest models, YOLOv11 and YOLOv12, further underscores our accuracy advantage. DY-YOLO achieves superior mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 on both datasets, demonstrating that our architectural innovations deliver leading detection performance against the most recent state-of-the-art methods.

To evaluate practical deployment potential, we measured inference speed on a desktop system with Intel i5-13400 F processor and NVIDIA RTX 4070 GPU, using 640 × 640 input resolution at batch size = 1. As shown in Table 9, our DY-YOLO maintains highly competitive inference efficiency with 8.21 ms latency (121.8 FPS), closely matching the fastest models in the comparison. Specifically, DY-YOLO achieves nearly identical speed to YOLOv8 (8.20 ms) while providing significantly better accuracy. Compared to the newer versions, our method is approximately 19% faster than YOLOv11 (10.14 ms) and 17% faster than YOLOv12 (9.85 ms), while maintaining accuracy advantages. This demonstrates that our architectural innovations successfully enhance feature representation capability without compromising inference efficiency. The results confirm that DY-YOLO achieves an optimal balance between accuracy and speed, making it well-suited for real-time industrial defect inspection systems.

In terms of model efficiency, DY-YOLO maintains a highly competitive profile. With 3.0 M parameters and 5.8 GFLOPs, our model operates within a similar efficiency range as YOLOv11 and YOLOv12, yet achieves higher accuracy. This indicates that DY-YOLO establishes a more favorable accuracy-efficiency trade-off. As shown in Figs. 14 and 15, DY-YOLO offers better performance than the extremely lightweight YOLOv9 without succumbing to the accuracy loss typical of aggressive model compression. At the same time, DY-YOLO achieved 121.8 FPS in testing, meeting real-time detection requirements. This combination of high accuracy, low computational cost, and practical inference speed makes DY-YOLO exceptionally well-suited for real-time inspection in industrial environments.

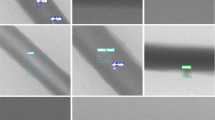

Visualization of detection results

Figures 16 and 17 respectively present the results of the DY-YOLO network model for smartphone cover glass defect detection on the MSD and SSGD datasets, along with heatmap visualizations. These results are compared with the visualizations from the current state-of-the-art YOLO series models, including YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, and YOLOv12. To highlight key regions in the heatmaps and provide a more intuitive representation of the model’s decision-making process, the heatmaps were subjected to Renormalize processing.

This paper employs the HiResCAM48 visualization method to demonstrate the model’s attention to target defects. Regardless of variations in the size of the target objects, DY-YOLO can effectively exclude interference from complex backgrounds, assign higher weights to detection regions of different scales, and maintain high sensitivity to object locations compared to other advanced methods. These results validate the model’s strong robustness under practical application conditions.

Conclusion

To address the challenges of complex backgrounds and scale variations in cover glass defect detection, this paper proposes a smartphone cover glass defect detection model, DY-YOLO, based on YOLOv8. The model incorporates dynamic convolution modules and introduces Dynamic Large Separable Kernel Attention (Dynamic-LSKA) and Dynamic-C2f to enhance the backbone network’s ability to extract global and local features. This improves the model’s anti-interference capability and its ability to extract key features under conditions where defect characteristics are not distinctly visible. Additionally, a High-Level Screening Feature Bidirectional Path Aggregation Network (HSF-BPAN) is designed to achieve effective fusion of multi-scale features. Furthermore, a lightweight dynamic upsampler, DySample, is employed for upsampling, which flexibly adjusts sampling positions by learning offsets, thereby reducing computational resource consumption.

In this study, DY-YOLO was systematically verified on the MSD and SSGD mobile phone cover glass defect benchmark datasets, and the experimental results showed that the accuracy of DY-YOLO was better than that of the baseline model, reaching 99.3% and 46% in mAP@0.5, respectively, while reducing the computing resource consumption by 33.3% and maintaining the inference speed of 121.8 FPS, making it suitable for real-time edge detection tasks. Compared to state-of-the-art methods, DY-YOLO still shows significant advantages in terms of accuracy-efficiency trade-offs. It is important to note that although the model shows strong robustness in complex environments, there is still room for improvement in terms of accuracy. Future work will focus on further improving its performance.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available. The MSD dataset is available on the official website: https://github.com/jianzhang96/MSD. The SSGD dataset is available on the official website: https://github.com/VincentHancoder/SSGD.

References

Sarwar, M. & Soomro, T. R. Impact of Smartphone’s on Society.

Zhang, Z. et al. Analyzing sustainable performance on high-precision molding process of 3D ultra-thin glass for smart phone. J. Clean. Prod. 255, 120196 (2020).

Bhutta, M. U. M., Aslam, S., Yun, P., Jiao, J. & Liu, M. Smart-inspect: Micro scale localization and classification of smartphone glass defects for industrial automation. In IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 2860–2865. https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS45743.2020.9341509 (IEEE, 2020).

Li, D., Liang, L. Q. & Zhang, W. J. Defect inspection and extraction of the mobile phone cover glass based on the principal components analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 73, 1605–1614 (2014).

Voulodimos, A., Doulamis, N., Doulamis, A. & Protopapadakis, E. Deep learning for computer vision: A brief review. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2018, 7068349 (2018).

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Malik J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation.

Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1504.08083 (2025).

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J. Faster, R-C-N-N. Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 39, 1137–1149 (2017).

Tian, Z., Shen, C., Chen, H. & He, T. FCOS: Fully convolutional one-stage object detection. In IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 9626–9635. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2019.00972 (IEEE, 2019).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.91 (IEEE, 2016).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 6517–6525. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.690 (IEEE, 2017).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: an incremental improvement. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.02767 (2018).

Bochkovskiy, A., Wang, C. Y. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2004.10934 (2020).

Jocher, G. et al. ultralytics/yolov5: V3.0. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3983579 (2020).

Li, C. et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.02976 (2022).

Wang, C. Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 7464–7475. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00721 (IEEE, 2023).

Jocher, G., Qiu, J. & Chaurasia, A. Ultralytics YOLO. https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (2024).

Wang, C. Y., Yeh, I. H. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. http://arxiv.org/abs/2402.13616 (2024).

Wang, A. et al. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection.

Khanam, R. & Hussain, M. YOLOv11: an overview of the key architectural enhancements. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.17725 (2024).

Tian, Y., Ye, Q. & Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.12524 (2025).

Shen, J., Liu, N., Sun, H., Li, D. & Zhang, Y. An instrument indication acquisition algorithm based on lightweight deep convolutional neural network and hybrid attention Fine-Grained features. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–16 (2024).

Lima, J. et al. Analysing impact of the digitalization on visual inspection process in smartphone manufacturing by using computer vision. In Advances in Manufacturing III (eds Hamrol, A. et al.) 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-00218-2_11 (Springer, 2022).

Kong, L., Shen, J., Hu, Z. & Pan, K. Detection of water-stains defects in TFT-LCD based on machine vision. In 2018 11th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI) 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/CISP-BMEI.2018.8633154 (2018).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Yang, M., Zhang, B., Zhang, J. & Su, H. Defect detection and classification for mobile phone cover glass based on visual perception. In 2020 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC) 2530–2535. https://doi.org/10.1109/CCDC49329.2020.9164343 (2020).

Li, C., Zhang, X., Huang, Y., Tang, C. & Fatikow, S. A novel algorithm for defect extraction and classification of mobile phone screen based on machine vision. Comput. Ind. Eng. 146, 106530 (2020).

Jian, C., Gao, J. & Ao, Y. Automatic surface defect detection for mobile phone screen glass based on machine vision. Appl. Soft Comput. 52, 348–358 (2017).

Turko, S. et al. Smartphone glass inspection system. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence 655–663. https://doi.org/10.5220/0010223306550663 (SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications, 2021).

Jogin, M. et al. Feature extraction using convolution neural networks (CNN) and deep learning. In 2018 3rd IEEE International Conference on Recent Trends in Electronics, Information & Communication Technology (RTEICT) 2319–2323. https://doi.org/10.1109/RTEICT42901.2018.9012507 (2018).

Lei, J., Gao, X., Feng, Z., Qiu, H. & Song, M. Scale insensitive and focus driven mobile screen defect detection in industry. Neurocomputing 294, 72–81 (2018).

Yang, G., Lai, H. & Zhou, Q. Visual defects detection model of mobile phone screen. IFS 43, 4335–4349 (2022).

Shen, J. et al. An algorithm based on lightweight semantic features for ancient mural element object detection. Npj Herit. Sci. 13, 70 (2025).

Shen, J. et al. Finger vein recognition algorithm based on lightweight deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–13 (2022).

Mao, Y., Yuan, J., Zhu, Y. & Jiang, Y. Surface defect detection of smartphone glass based on deep learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 127, 5817–5829 (2023).

Zhou, S. Y. et al. PGS–YOLO: A smartphone screen blemish detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv8n. Comput. Eng. 51, 326–339 (2025).

Li, W., Chen, Z., Zhang, X. & Zha, Y. PU–Faster R–CNN based defect detection algorithm for mobile phone screens. Comput. Meas. Control. 31, 99–106 (2023).

Liu, W., Lu, H., Fu, H. & Cao, Z. Learning to Upsample by Learning to Sample.

Chen, Y. et al. Dynamic convolution: Attention over convolution kernels. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11027–11036. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01104 (IEEE, 2020)

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556 (2014).

Szegedy, C. et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298594 (IEEE, 2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (IEEE, 2016).

Lau, K. W., Po, L. M. & Rehman, Y. A. U. Large separable kernel attention: rethinking the large kernel attention design in CNN. Expert Syst. Appl. 236, 121352 (2024).

Yu, F. & Koltun, V. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1511.07122 (2016).

Zhang, J., Ding, R., Ban, M. & Guo, T. FDSNeT: An accurate real-time surface defect segmentation network. In ICASSP 2022–2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 3803–3807. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9747311 (2022).

Han, H., Yang, R., Li, S., Hu, R. & Li, X. SSGD: A smartphone screen glass dataset for defect detection. In ICASSP 2023–2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10096682 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. In 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 16965–16974. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01605 (IEEE, 2024).

Draelos, R. L. & Carin, L. Use HiResCAM instead of grad-CAM for faithful explanations of convolutional neural networks. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2011.08891 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and N.B.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L.; validation, J.L.and H.L.; formal analysis, J.L.and H.L.; investigation, Y.H.; resources, H.L.; data curation, J.L. and M.L.; writing-original draft preparation, J.L.; writing-review and editing, J.L.; visualization, J.L. and M.L.; supervision, N.B.; funding acquisition, N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Long, H., Liu, M. et al. Smartphone screen surface defect detection using dynamic large separable kernel attention and multi-scale feature bi-directional path aggregation network. Sci Rep 15, 40620 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24225-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24225-y