Abstract

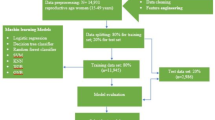

Pregnant women in rural Ethiopia face substantial barriers to accessing adequate healthcare services, contributing to adverse maternal and neonatal health outcomes. Traditional statistical approaches often fall short in capturing the complex, nonlinear interactions among the diverse factors influencing healthcare access. In contrast, machine learning (ML) techniques offer robust tools for analysing large-scale datasets, identifying hidden patterns, and generating accurate predictive insights to inform healthcare interventions. This study aimed to determine the most effective machine-learning algorithm for predicting healthcare service access among pregnant women in rural Ethiopia. Data were sourced from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS). Seven supervised ML classifiers; Gradient Boosting, Random Forest, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression, and Naive Bayes were applied to predict determinants of healthcare access. Model performance was evaluated using accuracy and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis was conducted to interpret the contribution of individual features. Gradient Boosting outperformed all other models based on its highest predictive AUC, achieving predictive accuracy (79.55%) and AUC (81.40%). Key protective (negative) factors associated with improved healthcare access included higher household wealth, residence in the Amhara region, media exposure, and alcohol avoidance. Conversely, lack of formal education emerged as a significant barrier, underscoring its critical role in limiting access to maternal health services. The superior performance of the Gradient Boosting model highlights its effectiveness in predicting healthcare access among pregnant women in rural Ethiopia. Socioeconomic status, regional residence, media exposure, and behavioural factors were linked to health service access, while lack of education remained a prominent barrier. These findings support the utility of machine learning in guiding data-driven policy and targeted interventions to enhance maternal health outcomes in resource-limited settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Access to healthcare services refers to the ability of individuals to obtain and utilize medical care when needed. This includes availability, affordability, and accessibility of essential health services to ensure overall well-being and disease prevention1,2,3. Ensuring access to vital maternal healthcare services is essential for supporting healthy pregnancy outcomes and lowering the risks of maternal and infant mortality4. However, differences in location, along with inadequate infrastructure and resources, create barriers that prevent pregnant women from receiving the healthcare services they require5,6.

Worldwide, approximately 800 women lose their lives each day due to preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth6. Globally, an estimated 300,000 women were expected to have died in 20107. Maternal and child mortality continue to be significant public health concerns in developing countries, with a stark contrast compared to developed nations. Limited access to modern healthcare services plays a major role in the rise of maternal deaths8. The maternal mortality rate in low- and middle-income countries is 15 times greater than that of developed nations9.

Sub-Saharan Africa recorded the highest maternal mortality ratio, with 64 deaths per 10,000 live births, while Ethiopia reported 900 maternal deaths9. The 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) reported a maternal mortality rate of 6.76 per 1,000 live births10. Maternal and child mortality result from inadequate utilization of healthcare services in many countries10. On average, 52% of women in developing regions accessed at least four antenatal care (ANC) services. In Asia, the percentage was 36%, while in sub-Saharan Africa, it stood at 49%11. In Ethiopia, the figure was 32%12.

Moreover, a significant proportion of women postponed their first antenatal care (ANC) visit, with 77.69% in 2005, 73.95% in 2011, and 67.61% in the 2016 EDHS13. The prevalence of pregnancy-induced hypertension, stillbirths, and unsafe abortions remains alarmingly high. Although institutional delivery helps mitigate pregnancy and childbirth risks, home births are still common in low-income countries, with institutional delivery rates ranging from 26% to 32.5% in Ethiopia14. Additionally, the utilization of postnatal care (PNC) services among women is low, standing at just 6.9%, with significant regional variations across Ethiopia15.

Limited access to healthcare services for pregnant women results in numerous life-threatening complications. Maternal and child health issues arise due to barriers such as the unavailability of healthcare facilities, inadequate health-seeking behaviours among women, restricted access to maternal and child health services, low media exposure, poor awareness and attitudes, and substandard service quality14,16,17. Additionally, geographical challenges hinder healthcare accessibility, as rural women often face transportation difficulties, leading to delays in initiating antenatal care (ANC) services18.

Various research studies have identified multiple factors influencing pregnant women’s access to healthcare services. In resource-constrained settings, four key barriers significantly affect women’s healthcare access: reluctance to go alone, long distances to health facilities, financial constraints for treatment, and the need for permission to seek medical care.

Previous studies have highlighted that long distances and the geographical location of health facilities19, poverty, low monthly income, and unemployment, which prevent women from affording medical care, as well as inadequate awareness, low-risk perception, lack of motivation, and the severity of illness discouraging women from seeking care alone20, all contribute to limited access. Additionally, the cultural norm where husbands and relatives have full decision-making authority over women’s healthcare further restricts maternal and child health service access21,22.

Maternal and child healthcare services are among the most effective interventions for reducing maternal and child mortality. Key components of these services include antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal care (PNC)23, institutional delivery services24, skilled birth assistance, as well as nutritional and breastfeeding counselling. These strategies align with the Millennium Development Goals to decrease mortality and morbidity rates. Additionally, healthcare facilities play a crucial role in providing both preventive and curative services to reduce maternal and child deaths15.

Maternal health services should be accessible and equitably distributed25, with a strong emphasis on ensuring the quality of healthcare delivery26 and maintaining an adequate number of healthcare professionals in medical facilities. Additionally, policymakers must recognize the challenges women face in accessing healthcare, including geographical disparities, to develop effective strategies and interventions. These efforts are essential for addressing maternal healthcare issues and ensuring both equitable access and high-quality service provision23,27.

Pregnant women in Ethiopia encounter major obstacles in obtaining sufficient healthcare services, resulting in negative maternal and child health outcomes. Conventional statistical methods may not effectively capture the intricate relationships among the various factors affecting healthcare access for pregnant women. Machine learning techniques provide a valuable alternative, enabling the analysis of large and diverse datasets, uncovering patterns, and making predictions that are more accurate.

In this study, we utilize machine-learning algorithms to identify hidden trends in how pregnant women in Ethiopia use healthcare services. This method enables us to analyse the influence of various factors, including socio-economic status, geographic location, and healthcare infrastructure, on access to maternal health services.

Utilizing machine learning models can offer valuable insights for policymakers and healthcare providers to enhance resource distribution, improve service delivery, and ultimately strengthen maternal and child health outcomes in Ethiopia. Additionally, this study contributes to the expanding research on leveraging technology to address healthcare disparities and improve access to essential services for vulnerable populations.

Given the limited research on women’s healthcare access in Ethiopia, particularly studies incorporating machine learning, this study serves as a crucial input for policymakers in addressing challenges related to maternal health services. Previous studies have been insufficient in utilizing advanced analytical techniques to explore women’s healthcare access comprehensively.

Furthermore, the findings of this research can support women’s decision-making regarding maternal health services and assist policymakers and program developers in designing targeted interventions to enhance healthcare access. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to predict the factors influencing healthcare access among pregnant women in rural Ethiopia using advanced machine learning algorithms.

Methods

Study design, period and area

A cross-sectional study was employed using data from the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), focusing on rural pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Source and study population

The analysis included rural pregnant women aged 15–49, residing in Ethiopia during the five years before the survey. Of the 15,683 women surveyed, a weighted sample of 885 pregnant women with complete data was used. Records lacking geographic coordinates and non-pregnant respondents were excluded. The data were accessed through a formal request to the DHS Program via their website.

Data collection tools and procedures

The 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) employed standardized and validated questionnaires adapted from the DHS Program’s standard formats to address population and health issues specific to Ethiopia. A two-stage stratified sampling method was applied to ensure the sample represented the national population. The regions of Ethiopia were first divided into urban and rural areas. In the first stage, 645 enumeration areas (EAs) were selected using probability proportional to size, based on the number of residential households recorded in the 2007 Ethiopian Population and Housing Census. In the second stage, 28 households were randomly chosen from the household listings within each selected cluster28. For this study, we used the women’s dataset (IR) from the 2016 EDHS. A detailed description of the sampling process is available in the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey reports on the DHS website (www.dhsprogram.com). However, only data from rural pregnant women were used for this analysis.

Variables of the study

Dependent variable

Access to health services for pregnant women: In this study, pregnant women were defined as all eligible women aged 15–49 years who were either permanent residents or visitors in the selected households and were present before the survey interview began. Several factors hindered their access to healthcare. The factors influencing pregnant women’s access to health services were adapted from the EDHS report and other relevant studies19. Access to health services for pregnant women was assessed based on four key factors: (1) not wanting to go alone, (2) distance to health facilities, (3) getting the money needed for treatment and (4) getting permission to go for medical care. Pregnant women were considered to have access to health services if they did not face any of these challenges. However, if they encountered at least one of these factors, they were classified as facing difficulties in accessing healthcare services29.

Independent variables

The socio-demographic explanatory variables in this study included age, educational status, wealth status, the sex of the household head, and region. The environmental explanatory variables included media exposure, current employment status, health insurance coverage, alcohol consumption history, khat chewing history, and whether the current pregnancy was desired. Media exposure was found to be related to pregnant women’s access to health services. Specifically, if the women had access to media such as radio, television, or newspapers, they were considered to have media exposure. On the other hand, if the women did not have access to any of these media, they were classified as having no media exposure29,30.

Data analysis

The data analysis for this study was carried out in two phases. In the first phase, statistical tools (R software) were used for data relevance analysis and descriptive data visualization. The dataset was then converted into a comma-delimited (CSV) format. The second phase involved pre-processing the data using RStudio and Python within an Anaconda notebook, which included tasks such as data cleaning and addressing missing values31.

Feature selection methods

Feature selection and variable importance ranking32,33 is a method used to identify a subset of relevant features by eliminating unnecessary or redundant ones. The importance of feature selection lies in lowering learning costs by reducing the number of features. In this study, the Boruta algorithm was selected for feature selection. This algorithm assesses feature relevance based on the Random Forest model’s importance estimates, identifying both highly relevant and less important features in the dataset34.

Data split

Data splitting refers to dividing the dataset into two parts: a training set used to build the model, and a separate test set to evaluate the model’s performance on new, unseen data. This is typically done using an 80/20 split ratio35.

Imbalanced data handling

Imbalanced data36 refers to situations where the distribution of the outcome variable is skewed, with disproportionate proportions between categories. When working with imbalanced datasets in prediction, the results can become biased. To address this issue, various methods for handling imbalanced data, such as Under-sampling, Over-sampling, SMOTE, ROSE, and ensemble balancing, were applied. Based on their performance, the SMOTE method was selected as the most effective approach. SMOTE improves class balance by creating new, synthetic examples of the minority class rather than duplicating existing ones. This helps reduce over fitting and allows the model to learn more general patterns. Unlike under sampling, it keeps all majority class data intact, preserving valuable information. As a result, it often leads to better performance on imbalanced datasets, especially in terms of recall and F1-score.

Building a predictive modelling

Predictive modeling involves creating a statistical model to forecast future behaviour, using a trained dataset as the foundation. In machine learning, it utilizes a set of predictor variables to estimate the likelihood of an outcome37. Depending on whether the dependent variable is binary (yes/no), various classification algorithms can be applied38. In this study, machine-learning techniques such as gradient boosting, Random Forest, logistic regression, Naïve Bayes classifier, Decision Tree (C5.0), Support Vector Machine with three different kernels, and K-Nearest Neighbors were used for predictions39. A balanced dataset was employed for each prediction algorithm to enhance the accuracy of the results39.

Performance evaluation for predictive models

The performance of the prediction models was evaluated using several standard metrics, including the ROC curve, accuracy via the confusion matrix and Kappa statistics.

Unsupervised machine learning for health service access

Unsupervised machine learning analyses input data to uncover significant patterns or structures that may not be immediately obvious. In this experiment, the model was not trained or supervised by users. Instead, it autonomously identifies hidden patterns and insights as it processes the data over time40.

Association rules

In this analysis, an unsupervised rule-based prediction method was employed. The method generated several rules for classification or prediction, and significant rules were selected based on performance metrics. Key rules were identified using lift41,42, a measure of the interestingness of an association. Lift quantifies the positive or negative correlation between the antecedent (if) and the consequent (then) of a rule. It is calculated as the ratio of the rule’s confidence to the probability of the consequent occurring. Specifically, it is the ratio of the probability of the dependent variable (B) occurring to the probability of the independent variable (A) condition being met:

The lift value ranges from [0, +∞). A lift value of 1 indicates that the simultaneous occurrence of X and Y are independent, meaning there is no correlation between A and B. These are considered uncorrelated rules. When the lift value is less than 1, it suggests that the occurrence of “A” decreases the likelihood of “B,” representing negative correlation rules. Conversely, a lift value greater than 1 implies that the occurrence of “A” increases the likelihood of “B,” indicating positive correlation rules.

In Eq. (1), the arrow symbol (→) represents a directional association rule between two events or conditions. It indicates that when event A occurs (the antecedent), event B (the consequent) is likely to follow. This does not imply causation but reflects a statistical relationship based on patterns in the data. The arrow helps define the structure of the rule used to measure the strength of association, such as with the lift metric.

Hyper parameter tuning

A working model parameter refers to an external characteristic of the model whose value is specified by the user, as it cannot be derived from the data itself43. For this study, the Optuna framework was utilized for hyper parameter tuning44. To better understand how to optimize values and avoid unnecessary estimates from combinations of underperforming parameters, the authors provide an explanation of how Optuna functions. They describe hyper parameter optimization as the process of minimizing or maximizing an objective function based on a set of hyper parameters as input44. This method outperforms traditional hyper parameter tuning approaches, such as grid search and randomized search, by more efficiently optimizing the model using user-specified hyper parameters.

Model interpretation/explanation using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP)

In machine learning research, it is often difficult to provide explanations and interpretations for complex models, especially tree-based ones, due to their ‘black box’ nature. To address this challenge and improve the interpretability of machine learning results, we utilized the SHAP value analysis method. Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), rooted in game theory, offers a way to explain predictions made by any machine learning model, whether at a global or local level45. The core concept behind SHAP analysis is to assess the marginal contribution of each predictor to the prediction of the outcome variable46,47.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

Of the 885 pregnant women included, the largest share came from the Somali region (16.2%), where only 19.6% had health service access. Most participants (65.3%) lacked formal education, and only 21.3% of these accessed services. The majority were aged 25–29 years (27.9%) (Table 1).

Environmental characteristics of the study participants

The majority of pregnant women, 706 (79.8%), reported not consuming alcoholic beverages, with only 158 (22.4%) of them having access to health services. Additionally, 694 women (78.4%) indicated that their current pregnancy was desired. Nearly all participants, 849 (95.9%), lacked health insurance coverage, and among these, 640 (75.4%) had access to health services (Table 2).

Feature selection

Feature selection is essential in predictive modeling, especially when working with datasets that contain a large number of variables46,47. In this study, the Boruta algorithm was used to pinpoint the most relevant features for predicting the outcome variable (Fig. 1). Among the twelve variables analyzed, five were identified as important for model development: wealth status, media exposure, region, educational level, and alcohol use, all marked in green. In contrast, variables like marital status, khat use, age, and sex were found to be irrelevant and were excluded by the model, shown in red (Fig. 1). Yellow boxplots represent features with uncertain relevance that may require further analysis, while blue boxplots indicate ‘shadow’ features created by the Boruta algorithm to serve as references in determining variable importance.

Predicting pregnant women’s health service access

Among the seven models evaluated, the Gradient Boosting algorithm delivered the highest AUC in predicting access to health services, with a score of 81.40, followed by SVM (75.10%), Decision Tree (73.90%), Logistic Regression (73.80%), Random Forest (73.10%), KNN (72.50%), and Naïve Bayes (72.2%). Overall, Gradient Boosting showed the strongest performance in predicting health service access in this study (Table 3).

ROC curve for the tested models

Figure 2 shows the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. Of the seven machine learning models tested in this study, the Gradient Boosting model achieved the highest AUC (Area under the Curve), highlighting AUC as the most reliable metric for evaluating model performance. This outperformed other measures like accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. The Gradient Boosting model proved to be the most effective at distinguishing between women with and without access to health services.

Figure 3 illustrates the SHAP global importance scores for the top six factors identified by the optimized Gradient Boosting model. The figure also highlights each feature’s contribution to predicting health service access. Features with higher mean absolute SHAP values have a greater influence on the predictions, and they are listed in descending order of their impact on the outcome variable. The findings show that region, wealth status, media exposure, occupational status, educational status, and alcohol consumption were the most significant factors, as depicted in Fig. 3.

Model explanation and justification

Beeswarm plots were used to offer a detailed view of how different variables influence the model’s predictions. Figure 4 shows the distribution of each predictor’s effect on the model’s output (i.e., predicting health service access) by displaying the Shapley values for each sample related to a specific predictor. The plot emphasizes the significance and relationship of the top six features with the outcome variable, where each point represents the Shapley value for a given feature in relation to health service access. In this visualization, red and blue points indicate higher and lower values of each predictor, respectively. Red points are associated with a higher likelihood of health service access, while blue points reflect lower probabilities (indicating a protective effect) (Fig. 4).

Waterfall plot interpretation

Waterfall plots were used to clarify the model’s predictions for positive cases of health service access. As depicted in Fig. 6, these plots start with the model’s expected output value on the x-axis (E[f(X)] = 0.757), which represents the initial prediction for a sample before considering the contributions of individual features. This baseline prediction typically reflects the average or most common prediction within the dataset.

If a model’s output for a specific observation is higher than this expected value (E[f(X)]), it is classified as a positive case (i.e., the individual had access to health services). In contrast, outputs below this threshold are categorized as negative, indicating no health service access. For the first observation, the expected value shifts to the final model output (f(x) = 0.18), classifying it as a positive case (indicating access to health services). This shift results from the combined effect of positive (red) and negative or protective (blue) contributions. Additionally, the waterfall plot provides insight into the predictability of individual features at the local level (Fig. 6).

The waterfall analysis shows that factors such as having the highest wealth status in the family (4 = wealth), a history of media exposure (1 = media), abstaining from alcohol consumption (0 = alcohol), and living in the Amhara region (3 = Amhara) are negative influencer of health service access among pregnant women, as represented by the blue colour. On the other hand, the lack of formal education (0 = education) has a significant influence on health service access, as indicated by the red colour in (Figs. 5 and 6).

Discussion

This study sought to forecast healthcare access and identify its determining factors among pregnant women in rural Ethiopia by utilizing machine-learning techniques on the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) dataset. Researchers evaluated seven machine-learning models: Gradient Boosting, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes, Decision Tree, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Support Vector Machine (SVM) with three different kernel types. To ensure balanced predictions, the dataset was equalized using the SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) method, which addressed class imbalance and significantly improved both accuracy and ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) scores.

The findings revealed that balancing the dataset with SMOTE significantly enhanced model performance compared to using imbalanced data. Among all models, Gradient Boosting demonstrated the highest performance, achieving an AUC (Area under the Curve) of 81.40% and an accuracy rate of 79.55%. This suggests that AUC is a more reliable performance indicator than metrics like accuracy, specificity, or sensitivity, particularly in imbalanced datasets. The strong AUC score of the Gradient Boosting model highlights its effectiveness in distinguishing between pregnant women with and without access to healthcare, making it a valuable tool for predicting service access.

To improve the interpretability of the machine learning results, the study incorporated SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations), a game theory-based approach that offers insight into how each feature influences model predictions. This method not only enhances transparency but also helps pinpoint the specific factors driving healthcare access outcomes.

Additionally, the Boruta algorithm was used to identify the most relevant predictors from twelve variables. Five key factors emerged as especially influential: region, wealth status, media exposure, level of education, and alcohol consumption. These variables were crucial in determining access to healthcare and were instrumental in constructing accurate prediction models.

Women with higher wealth status, those living in the Amhara region, those who had media exposure, and those who abstained from alcohol were more likely to access healthcare services. Conversely, women without formal education were less likely to obtain such services.

In more detail, wealth status was positively associated with healthcare access. Interestingly, women in the wealthier category had a protective advantage over those in the poorest category. This aligns with previous studies from Ethiopia15,48,49,50,51, Bangladesh52, and Nigeria17. A higher wealth index is typically linked to easier access to care due to better financial capacity, insurance coverage, and the ability to afford transport and medication53.

Alternatively, individuals with greater wealth often have access to higher levels of education and health literacy, which equips them to make smarter health decisions and use healthcare resources more effectively54. Even though Ethiopia provides free maternity and ambulance services, many essential drugs and transport costs are out-of-pocket expenses, which disproportionately affect poorer women55,56. In contrast, wealthier women can better afford these additional costs, resulting in more timely and consistent access to care48. Policymakers are encouraged to support economic empowerment programs that help women generate sustainable income.

Media exposure also played a significant role. Women with access to media were more likely to use healthcare services. This finding is consistent with studies from Ethiopia19,24,50, Tanzania57, Bangladesh58, and India59,60. Media access likely boosts health awareness, increases knowledge of available services, and encourages timely healthcare-seeking behaviour. In contrast, women with no media exposure may lack critical health information, leading to underuse of services and delayed care61,62. To bridge this gap, health communication strategies should be expanded, especially in underserved areas, through radio, TV, mobile platforms, and community outreach programs.

Educational attainment was another key determinant. Women without formal education were less likely to access maternal healthcare services compared to those with higher education levels. This aligns with other studies in Ethiopia13,18,48,49,50,51,63 and Nigeria17. Education plays a crucial role in promoting positive health behaviours, such as choosing institutional delivery and recognizing the importance of prenatal care. Educated women are more informed and confident in navigating healthcare systems48. Policies should emphasize promoting girls’ education, incorporating health education into curricula, and enhancing health literacy through community-based programs.

Lastly, alcohol consumption was found to negatively influence healthcare access. Women who abstained from alcohol were more likely to seek and receive care. This pattern is supported by studies from Germany64 and Canada65. Women who avoid alcohol may be more health-conscious and more likely to engage in proactive health-seeking behaviours. These findings underline the importance of addressing behavioural factors and promoting healthy lifestyles through public health initiatives that discourage substance use and encourage responsible health practices.

Strengths and limitations

The use of the comprehensive and nationally representative EDHS dataset provides valuable insights that go beyond what individual institutional studies can offer, making it particularly useful for informing policy decisions. A notable strength of this study lies in its comparative evaluation of several machine learning algorithms, allowing for the identification of the most effective model to predict healthcare access among pregnant women. This multi-algorithm approach sets the study apart from conventional research, which often relies on a single statistical method and may miss the potential benefits of alternative algorithms.

However, due to the reliance on secondary data, some important variables related to healthcare access were not available, which may have contributed to the moderate performance of the models. Including these missing variables in future research could improve the accuracy of predictions, underlining the value of applying machine learning techniques to more comprehensive datasets.

Conclusion

This study applied machine-learning techniques to build a predictive model for assessing healthcare access among pregnant women in Ethiopia. Using a design science approach, the researchers developed the model with several ensemble and individual machine learning algorithms, including Gradient Boosting, Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Decision Tree, Naïve Bayes, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Support Vector Machine (SVM). After conducting five experimental tests, Gradient Boosting emerged as the top-performing algorithm, achieving the highest Area under the Curve (AUC) score. This result suggests that AUC is a more reliable performance metric than traditional measures such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values. The strong performance of Gradient Boosting indicates its effectiveness in distinguishing between women with and without access to healthcare services.

Based on these findings, the study recommends developing an AI-based application that incorporates the Gradient Boosting model to improve predictions of healthcare access. The research also identified key determinants of access: higher household wealth, living in the Amhara region, media exposure, and avoiding alcohol were associated with better healthcare access. In contrast, lack of formal education stood out as a major barrier, highlighting its significant influence on healthcare accessibility.

Overall, the study demonstrates that machine learning can reveal new insights and predictors that traditional statistical approaches might overlook. These insights are valuable for policymakers aiming to design targeted strategies to close gaps in healthcare access. The findings emphasize the importance of addressing socioeconomic obstacles; such as poverty, limited media exposure, alcohol use, and low education levels in efforts to ensure equitable access to maternal health services.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the manuscript.

References

Organization, W. H. Primary health care (2023).

Services USDoHaH. Access to Health Services (2023).

Penchansky, R. & Thomas, J. W. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med. Care. 19(2), 127–140 (1981).

Organization, W. H. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience(World Health Organization, 2016).

Csa, I. Central Statistical Agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey(Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, 2016).

Tarekegn, S. M., Lieberman, L. S. & Giedraitis, V. Determinants of maternal health service utilization in ethiopia: analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 14(1), 1–13 (2014).

Organization, W. H. Maternal mortality and child health fact sheet. (2012). https://www.who.int/en/news-room/factsheets/detail/maternal-mortality. 2012.

Addisse, M. Maternal and child health care. Lecture notes for health science students Ethiopian Public Health Training Initiative (2003).

Organization, W. H. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990–2015: Estimates from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations (World Health Organization, 2015).

Mekonnen, Y. & Mekonnen, A. Factors influencing the use of maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 374–382 (2003).

Tegegne, T. K., Chojenta, C., Getachew, T., Smith, R. & Loxton, D. Antenatal care use in ethiopia: a Spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 19, 1–16 (2019).

Program, D. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016 (2016).

Belay, D. G. et al. Spatiotemporal distribution and determinants of delayed first antenatal care visit among reproductive age women in ethiopia: a Spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Public. Health. 21, 1–18 (2021).

Sisay, D., Ewune, H. A., Muche, T. & Molla, W. Spatial distribution and associated factors of institutional delivery among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: the case of Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. (2022).

Sisay, M. M. et al. Spatial patterns and determinants of postnatal care use in ethiopia: findings from the 2016 demographic and health survey. BMJ open. 9(6), e025066 (2019).

Akunga, D., Menya, D. & Kabue, M. Determinants of postnatal care use in Kenya. Afr. Popul. Stud. 28(3), 1447–1459 (2014).

Dahiru, T. & Oche, O. M. Determinants of antenatal care, institutional delivery and postnatal care services utilization in Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 22(1) (2015).

Tesfaye, G., Loxton, D., Chojenta, C., Semahegn, A. & Smith, R. Delayed initiation of antenatal care and associated factors in ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproductive Health. 14, 1–17 (2017).

Alamneh, T. S. et al. Barriers for health care access affects maternal continuum of care utilization in Ethiopia; Spatial analysis and generalized estimating equation. Plos One. 17(4), e0266490 (2022).

Banda, C. Barriers to utilization of focused antenatal care among pregnant women in Ntchisi district in Malawi (2013).

Baffour-Awuah, A., Mwini-Nyaledzigbor, P. & Richter, S. Enhancing focused antenatal care in ghana: an exploration into perceptions of practicing midwives. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2, 59–64 (2015).

Alkema, L. et al. Global, regional, and National levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN maternal mortality Estimation Inter-Agency group. Lancet 387(10017), 462–474 (2016).

Yeneneh, A., Alemu, K., Dadi, A. F. & Alamirrew, A. Spatial distribution of antenatal care utilization and associated factors in ethiopia: evidence from Ethiopian demographic health surveys. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 18(1), 1–12 (2018).

Tesema, G. A., Mekonnen, T. H. & Teshale, A. B. Individual and community-level determinants, and Spatial distribution of institutional delivery in Ethiopia, 2016: Spatial and multilevel analysis. PloS One. 15(11), e0242242 (2020).

Assefa, Y., Van Damme, W., Williams, O. D. & Hill, P. S. Successes and challenges of the millennium development goals in ethiopia: lessons for the sustainable development goals. BMJ Global Health. 2(2), e000318 (2017).

Organization, W. H. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities (2016).

Demsash, A. W. et al. Spatial and multilevel analysis of sanitation service access and related factors among households in ethiopia: using 2019 Ethiopian National dataset. PLOS Global Public. Health. 3(4), e0001752 (2023).

Csa, I. Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA (Central statistical agency (CSA), 2016).

Demsash, A. W. & Walle, A. D. Women’s health service access and associated factors in ethiopia: application of geographical information system and multilevel analysis. BMJ Health Care Inf. 30(1) (2023).

Demsash, A. W. et al. Spatial distribution of vitamin A rich foods intake and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in ethiopia: Spatial and multilevel analysis of 2019 Ethiopian mini demographic and health survey. BMC Nutr. 8(1), 1–14 (2022).

Lantz, B. Machine learning with R: Packt publishing ltd (2013).

Revathy, R. & Lawrance, R. Comparative analysis of C4. 5 and C5. 0 algorithms on crop pest data. Int. J. Innovative Res. Comput. Communication Eng. 5(1), 50–58 (2017).

Yildirim, P. Filter based feature selection methods for prediction of risks in hepatitis disease. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Comput. 5(4), 258 (2015).

Stańczyk, U. & Jain, L. C. Feature Selection for Data and Pattern Recognition(Springer, 2015).

Duchesnay, E. & Löfstedt, T. Statistics and Machine Learning in Python. Release 0.1(Springer, 2018).

Zheng, Z., Cai, Y. & Li, Y. Oversampling method for imbalanced classification. Comput. Inform. 34(5), 1017–1037 (2015).

Khadge, M. R. & Kulkarni, M. V. (eds) Machine learning approach for predicting end price of online auction. 2016 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT) (IEEE, 2016).

Raschka, S. Python machine learning: Packt publishing ltd (2015).

Uddin, S., Khan, A., Hossain, M. E. & Moni, M. A. Comparing different supervised machine learning algorithms for disease prediction. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 19(1), 281 (2019).

Berry, M. W., Mohamed, A. & Yap, B. W. Supervised and unsupervised learning for data science (Springer, 2019).

Prajapati, D. J., Garg, S. & Chauhan, N. Interesting association rule mining with consistent and inconsistent rule detection from big sales data in distributed environment. Future Comput. Inf. J. 2(1), 19–30 (2017).

Ju, C., Bao, F., Xu, C. & Fu, X. A novel method of interestingness measures for association rules mining based on profit (Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2015).

Brownlee, J. Machine Learning Mastery with Python: Understand your data, Create Accurate models, and Work Projects end-to-end (Machine Learning Mastery, 2016).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. (eds) Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining (2019).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Gebreyesus, Y., Dalton, D., Nixon, S., De Chiara, D. & Chinnici, M. Machine learning for data center optimizations: feature selection using Shapley additive explanation (SHAP). Future Internet. 15(3), 88 (2023).

Liu, Y., Liu, Z., Luo, X. & Zhao, H. Diagnosis of parkinson’s disease based on SHAP value feature selection. Biocybernetics Biomedical Eng. 42(3), 856–869 (2022).

Tarekegn, S. M., Lieberman, L. S. & Giedraitis, V. Determinants of maternal health service utilization in ethiopia: analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 14, 1–13 (2014).

Negero, M. G., Sibbritt, D. & Dawson, A. Access to quality maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis (2022).

Demsash, A. W. & Walle, A. D. Women’s health service access and associated factors in ethiopia: application of geographical information system and multilevel analysis. BMJ Health Care Inf. 30(1), e100720 (2023).

Tessema, Z. T., Yazachew, L., Tesema, G. A. & Teshale, A. B. Determinants of postnatal care utilization in sub-Saharan africa: a meta and multilevel analysis of data from 36 sub-Saharan countries. Ital. J. Pediatr. 46, 1–11 (2020).

Yaya, S., Bishwajit, G. & Ekholuenetale, M. Factors associated with the utilization of institutional delivery services in Bangladesh. PloS One. 12(2), e0171573 (2017).

Arthur, E. Wealth and antenatal care use: implications for maternal health care utilisation in Ghana. Health Econ. Rev. 2, 1–8 (2012).

Yaya, S., Bishwajit, G. & Shah, V. Wealth, education and urban–rural inequality and maternal healthcare service usage in Malawi. BMJ Global Health. 1(2), e000085 (2016).

Mekonen, A. M., Kebede, N., Dessie, A., Mihret, S. & Tsega, Y. Wealth disparities in maternal health service utilization among women of reproductive age in ethiopia: findings from the mini-EDHS 2019. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24(1), 1034 (2024).

Minyihun, A. & Tessema, Z. T. Determinants of access to health care among women in East African countries: a multilevel analysis of recent demographic and health surveys from 2008 to 2017. Risk Manage. Healthc. Policy 1803–1813 (2020).

Mwangakala, H. A. Pregnant women’s access to maternal health information and its impact on healthcare utilization behaviour in rural Tanzania (Loughborough University, 2016).

Parvin, R. A., Faisal-E-Alam, M. & Hossain, M. B. Role of mass media in using antenatal care services among pregnant women in Bangladesh. Indonesian J. Innov. Appl. Sci. (IJIAS). 2(2), 143–149 (2022).

Singh, R. et al. Utilization of maternal health services and its determinants: a cross-sectional study among women in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 38, 1–12 (2019).

Ghosh, D. Effect of mothers’ exposure to electronic mass media on knowledge and use of prenatal care services: a comparative analysis of Indian States. Prof. Geogr. 58(3), 278–293 (2006).

Acharya, D., Khanal, V., Singh, J. K., Adhikari, M. & Gautam, S. Impact of mass media on the utilization of antenatal care services among women of rural community in Nepal. BMC Res. Notes. 8, 1–6 (2015).

Zamawe, C. O., Banda, M. & Dube, A. N. The impact of a community driven mass media campaign on the utilisation of maternal health care services in rural Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 16, 1–8 (2016).

Sisay, D., Ewune, H. A., Muche, T. & Molla, W. Spatial distribution and associated factors of institutional delivery among Reproductive-Age women in ethiopia: the case of Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2022(1), 4480568 (2022).

Lange, A. E. et al. Antenatal care and health behavior of pregnant Women—An evaluation of the survey of neonates in Pomerania. Children 10(4), 678 (2023).

Debessai, Y., Costanian, C., Roy, M., El-Sayed, M. & Tamim, H. Inadequate prenatal care use among Canadian mothers: findings from the maternity experiences survey. J. Perinatol. 36(6), 420–426 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to the DHS program for permitting data access.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Abdulaziz Kebede Kassaw, Atitegeb Abera Kidie, Natnael Amare Tesfa, Esuyawkal Mislu, Ali Yimer, Molla Hailu, Hassen Ahmed Yesuf, Birtukan Gizachew Ayal, Abebe Kassa Geto and Sefineh Fenta Feleke Data curation: Abdulaziz Kebede Kassaw, Atitegeb Abera Kidie, Natnael Amare Tesfa, Esuyawkal Mislu, Ali Yimer, Molla Hailu, Hassen Ahmed Yesuf, Birtukan Gizachew Ayal, Abebe Kassa Geto and Sefineh Fenta FelekeFormal analysis: Abdulaziz KebedeMethodology: Abdulaziz Kebede Kassaw, Atitegeb Abera Kidie, Natnael Amare Tesfa, Esuyawkal Mislu, Ali Yimer, Molla Hailu, Hassen Ahmed Yesuf, Birtukan Gizachew Ayal, Abebe Kassa Geto and Sefineh Fenta Feleke Writing – original draft: Abdulaziz Kebede Kassaw, Atitegeb Abera Kidie, Natnael Amare Tesfa, Esuyawkal Mislu, Ali Yimer, Molla Hailu, Hassen Ahmed Yesuf, Birtukan Gizachew Ayal, Abebe Kassa Geto and Sefineh Fenta Feleke Writing – review & editing: Abdulaziz Kebede Kassaw, Atitegeb Abera Kidie, Natnael Amare Tesfa, Esuyawkal Mislu, Ali Yimer, Molla Hailu, Hassen Ahmed Yesuf, Birtukan Gizachew Ayal, Abebe Kassa Geto and Sefineh Fenta Feleke All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The researchers received the survey data approval letter from the USAID DHS program after registering with the link https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin/login_main.cfm and then the researchers of this study maintained the confidentiality and privacy of the data. This study was based on publicly available secondary data source. The study does not require ethical approval because it was a secondary data analysis using the 2016 EDHS database. After receiving the data from the USAID–DHS program, the researchers in this study maintained the data’s anonymity. During the survey, informed consent was received from the study participants prior to the start of study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kassaw, A.K., Kidie, A.A., Tesfa, N.A. et al. Optimizing machine learning models for predicting health service access and determinants among pregnant women in rural Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 40559 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24245-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24245-8