Abstract

Ropivacaine is a commonly utilized local anesthetic for spinal anesthesia (SA); however, its optimal concentration for elective anorectal surgery has not been thoroughly estimated. This study investigated the minimum effective concentration (MEC90) of ropivacaine required to achieve successful SA in patients aged 18–65 years undergoing elective anorectal procedures. Fifty-one patients received SA with 1.5 ml of ropivacaine hydrochloride, utilizing a biased coin design and an up-and-down method, commencing at an initial concentration of 0.30% and adjusted in increments of 0.05%. The results demonstrated that the MEC90 of ropivacaine for SA was 0.2482% (3.7320 mg, 95% CI: 0.1500–0.3000%). Moreover, MEC99 was extrapolated to 0.2926% (4.4389 mg, 95% CI: 0.2500–0.3000%) for 1.5 ml. These findings suggest that a concentration of 0.2482% (3.7320 mg) effectively induces SA in 90% of patients, while a higher concentration of 0.2926% (4.4389 mg) may be recommended to achieve a 99% efficacy rate.

Clinical trial registration ChiCTR2300074796 (https://www.chictr.org.cn/).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anorectal day surgery has gained significant importance in contemporary medicine, owing to its convenience and cost-effectiveness, and the demands for rapid recovery. Spinal anesthesia (SA) is widely used in such procedures because it offers rapid onset, effective control, and expedited recovery1,2. Among the various local anesthetics, ropivacaine is frequently utilized due to its favorable safety profile and reliable efficacy1,2,3. However, the optimal concentration of ropivacaine specifically for SA in elective anorectal surgeries remains inadequately established.

Previous studies have extensively investigated the efficacy of ropivacaine in various forms of anesthesia, particularly caudal blocks, for anorectal surgery4,5. For instance, Zhang et al. found the minimum effective volume (MEV) of 0.5% ropivacaine to be 12.88 ml for males and 10.73 ml for females in anorectal day surgery, with MEV99 values of 13.88 ml and 11.87 ml, respectively5. Similarly, Li et al. observed that 14 ml of 0.35% ropivacaine yielded 90% efficacy in males, and 12 ml achieved the same efficacy in females; a 99% success rate was expected using a 0.4% concentration of 14 ml for males and 12 ml for females4. Although these studies have provided valuable insights into the MEV and concentration of ropivacaine for specific applications, there is a notable gap in the research regarding the optimal concentration for SA in the context of anorectal day surgery. Our study aimed to address this gap by determining the minimum effective concentration(MEC90) of ropivacaine required to achieve adequate anesthesia without compromising patient safety and comfort during anorectal day surgery.

To achieve a robust estimation, our study employed a prospective double-blind biased coin design up-and-down method (BCD-UDM)6,7,8 in a population undergoing elective anorectal surgery. This methodological approach allowed for precise adjustment of ropivacaine concentration, prospective blinded assessment, and accurate modeling of dose–response relationships using isotonic regression and bootstrap resampling algorithms. While MEC90 serves as the primary endpoint due to its clinical relevance and efficiency, modern statistical methods enable extrapolation to higher efficacy thresholds, including MEC99, which represents the concentration effective in 99% of patients9. In our study, we estimated both MEC90 and MEC99 using these robust statistical techniques, thereby providing comprehensive guidance for clinical practice.

Although dose-finding data exist for ropivacaine in lower abdominal procedures, these estimates cannot be applied to intrathecal anesthesia in ambulatory anorectal surgeries. First, anorectal surgery requires dense sensory block of sacral segments S2–S5 while preserving lumbar motor function, as dermatomal targets differ from gynecologic, urologic, or inguinal operations. Second, surgical stimuli like anal canal dilation, hemorrhoid ligation, and fissurectomy induce intense somatic nociception and reflex sphincter contraction, unlike comparator procedures. Third, the intrathecal spread of (hyper) baric ropivacaine is influenced by posture, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume, and small-volume dosing, which differ from caudal/epidural techniques or blocks for higher dermatomes. Finally, day surgery pathways limit the therapeutic window; excessive dosing can cause hypotension, motor block, and urinary retention, delaying discharge, whereas insufficient dosing leads to inadequate blockade, requiring rescue analgesia or general anesthesia, causing patient movement and poor conditions. Therefore, a procedure-specific intrathecal ropivacaine concentration for anorectal day surgery needs to be determined. This gap motivated our study to estimate the MEC90 (and extrapolated MEC99) of ropivacaine for spinal anesthesia. By determining these MECs for SA in outpatient anorectal surgery, our findings aim to enhance patient safety, optimize anesthetic efficacy, and improve the surgical outcomes.

Methods

Participants

This prospective, randomized, double-blind trial aimed to determine the MEC90 of ropivacaine hydrochloride for subarachnoid anesthesia during anorectal day surgery. This study adhered to the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of Fengdu People’s Hospital (Chongqing, China) and was approved by the committee (Approval No 2022SC0722-91). All participants provided informed consent and were granted full autonomy to ensure strict adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki throughout the study. It was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2300074796) on August 16, 2023, before enrolling the first subject. After providing written informed consent, patients aged 18–65 years who underwent hemorrhoid or fistula resection surgery or anorectal polypectomy at Fengdu People’s Hospital, Chongqing, China, from September 2, 2023, to November 10, 2023, were prospectively enrolled. Participants with severe cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases or contraindications to SA were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included preoperative neurological or psychiatric disorders; neuromuscular disorders; severe cardiac, pulmonary, or brain disorders; communication disorders; severe hepatic or renal failure; coagulation dysfunction; pregnancy or lactation; recent participation in other trials; history of allergy to local anesthetic drugs; peripheral neuropathy; and puncture site infection. This study aimed to maintain a focused and appropriate cohort of participants.

BCD-UDM approach for anaesthesia procedures and study design

Randomization codes were generated by an independent statistician. A pharmacy nurse prepared the coded syringes only. Patients received standardized instructions; performing anesthesiologists knew syringe IDs only; outcome assessors used objective tools (Bromage scale, pinprick test) blinded to allocations.

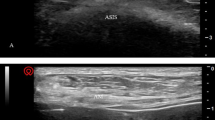

Patients underwent SA via either the lumbar lateral median sagittal oblique or transverse spinous space puncture method, with the puncture site at L3/410,11,12. Thorough sterilization of the puncture site was ensured, with the patient in the left lateral position. Initially, 0.5% lidocaine hydrochloride solution was administered for local anesthesia. Subsequently, 1.5 mL of hyperbaric ropivacaine was administered intrathecally, following our institutional protocol, which has been honed through more than 6000 anorectal procedures, achieving a documented failure rate of less than 1%. An epidural catheter was then inserted, and the effectiveness of the block was evaluated using pinprick testing in the perineal area (S3 dermatome) and by observing anal sphincter relaxation4. Following the administration, the patient was promptly placed in a horizontal supine position. All patients were managed by the same senior anesthesiologist, Dr. Jintao Shen, an Associate Chief Physician, to ensure a consistent and high level of expertise across the procedures.

Successful SA was defined as a pain-free procedure 10 min post-injection without additional intervention. The confirmed cases received 0.5–1 µg/kg/h intravenous dexmedetomidine for maintenance. Effective anesthesia was defined by simultaneously meeting these criteria: successful sensory block, defined as the absence of significant pain (VAS score ≤ 3) upon a standardized initial surgical stimulus (gentle traction on the anal canal). Successful Motor Block: Complete relaxation of the internal anal sphincter, assessed by digital examination and defined as the absence of palpable voluntary or reflexive contraction. No Supplemental Anesthesia: No rescue lidocaine was needed within 10 min after spinal injection. Blinded assessors evaluated these criteria at 3, 5, and 10 min post-injection. An outcome was classified as a failure if any criterion was not met at 10 min, requiring supplemental anesthesia. In cases where effective anesthesia was not achieved within 10 min, a standardized rescue protocol was initiated: 3 mL of isobaric 1% lidocaine hydrochloride (30 mg) was administered intrathecally. Anesthesia was reassessed at 15 min post-initial injection; if block failure persisted, a second 3 mL lidocaine bolus (total 60 mg) was administered. Patients who did not achieve effective anesthesia after the second rescue dose were transitioned to general anesthesia. These patients were excluded from the per-protocol analysis, but retained for safety reporting and classified as rescue failures, ensuring patient safety and methodological rigor.

The sensory block level was assessed via pinprick testing from the S3 to L4 dermatomes via a 26 G needle at intervals after ropivacaine administration and at the end of surgery. Motor block was evaluated using the Bromage scale to assess movement limitations of the feet and knees13. Adverse events, including urinary retention, cephalalgia, hypotension, bradycardia, and lower-extremity sensorimotor deficits, were systematically documented if they occurred during surgery or ≤ 72 h postoperatively. Postoperative pain control was not recorded by the acute pain service team in this study.

BCD-UDM was used to determine the optimal concentration of ropivacaine hydrochloride for adequate SA14. An initial intrathecal concentration of 0.30% (4.50 mg in 1.5 mL) was selected based on clinical and methodological grounds. In our day-surgery anorectal practice, 1.5 mL of 0.33% hyperbaric ropivacaine hydrochloride reliably achieves dense sacral anesthesia with rapid recovery; therefore, we set the starting concentration slightly lower to preserve a safety margin and allow symmetric up/down titration within the BCD-UDM design. The concentration of ropivacaine was adjusted using a BCD-UDM design targeting MEC90 in the patients. After an unsuccessful block, the concentration was increased by 0.05% (0.75 mg). After a successful block, a random integer between 1 and 100 was generated using SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A value ≤ 11 resulted in a 0.05% decrease in the concentration for the next patient, whereas a value ≥ 12 maintained the current concentration15,16.

This protocol implemented a biased-coin parameter b = 0.11, which theoretically estimated a stationary success probability π* at the target dose through the relationship π* = 1/(1 + b). Consequently, our design targeted π* ≈ 0.90, which corresponds to the MEC90. This approach maximizes allocation efficiency while preserving dose–response characterization capacity.

After the experiment, sealed envelopes with each patient’s ID number and specific drug concentration received were opened6. This provided essential information for the final analysis and marked the end of the blinding status of the study, maintaining a rigorous double-blind protocol for our study design.

Randomisation and concealment procedures

The subjects were sequentially numbered according to their enrolment order, and the numbering was managed by statisticians to ensure consistency between the subject numbers and envelope numbers. After the randomization scheme was generated, random numbers and the corresponding treatment protocols (drug concentrations) were sealed in consecutively numbered opaque envelopes. To maintain the double-blind nature of the study, all drugs were prepared by a nurse who was not involved in the study according to randomized drug concentrations. Following enrolment, the researchers took corresponding numbered envelopes and administered the interventions based on the indicated treatment protocol. After the study was concluded, blinding was lifted and statistical analysis was conducted to determine the MEC90 of ropivacaine hydrochloride.

Preparation of hyperbaric ropivacaine hydrochloride solutions

In this study, we used a Lichen Technology Discovery-F-10–100 µL pipette (Shanghai Lichen Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) to prepare 1.5 ml of hyperbaric ropivacaine hydrochloride solutions at various concentrations. The preparation method was as follows: 0.45 ml of the 1% ropivacaine hydrochloride injection mixture was mixed with 1.05 ml of the 10% glucose injection mixture to prepare a 0.30% solution; 0.375 ml of the 1% ropivacaine hydrochloride injection mixture was mixed with 1.125 ml of the 10% glucose injection mixture to prepare a 0.25% solution; 0.30 ml of the 1% ropivacaine hydrochloride injection mixture was mixed with 1.20 ml of the 10% glucose injection mixture to prepare a 0.20% solution; and 0.225 ml of the 1% ropivacaine hydrochloride injection mixture was mixed with 1.275 ml of the 10% glucose injection mixture to prepare a 0.15% solution. All solutions were prepared under sterile conditions and were thoroughly mixed before use to ensure homogeneity.

Sample size

The sample size was guided by the operational characteristics of the BCD-UDM. Unlike fixed-nominal-size trials, this adaptive design does not rely on hypothesis testing for sample size estimation. Instead, the required sample size was determined by simulation studies from previous dose-finding trials using similar methodologies6,17,18, which indicated that approximately 45 successful blocks were sufficient for the model to converge and provide a robust and precise estimation of the MEC90 (e.g., with a reasonably narrow confidence interval). Therefore, a prospective stopping rule was set at 45 successful blocks to ensure adequate data collection for the estimation.

Post-trial validation using monte carlo simulation

Our post-hoc Monte Carlo simulations (see Supplementary Materials) provide a nuanced understanding of the sample size-precision relationship19. While the predefined stopping rule (N = 45 successes) achieved clinically acceptable precision (MEC90 95% CI width = 0.121%), the simulations indicated that a larger sample size (e.g., N = 100) would yield a 41.3% improvement in precision (CI width = 0.071%). This valuable insight calibrates the trade-off between operational efficiency and statistical optimization in future study designs.

Four dose levels were used: 0.15% (2.25 mg), 0.20% (3 mg), 0.25% (3.75 mg), and 0.30% (4.50 mg). Recruitment continued until the stopping rule was met. The process concluded after the 51st enrollment, yielding the 45th successful block. In total, 51 patients were enrolled, and 50 were included in the final analysis after excluding one patient who underwent a unilateral spinal anesthesia.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative indicators were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (minimum, maximum, or interquartile range), whereas categorical indicators were presented as frequencies (percentages). MEC90 and MEC99 were estimated using isotonic regression, a non-parametric technique that fits a monotonically non-decreasing dose–response curve7,15,20. The model used ropivacaine concentration levels as the independent variable and binary outcomes (success/failure) as the dependent variable. Isotonic regression was implemented using the Pool-adjacent-violators algorithm (PAVA) and Isotonic Regression modules in Python20. MEC99 was subsequently extrapolated from the same fitted curve to estimate the concentration required to achieve a 99% success probability, considering the potential limitations of extrapolation beyond the observed dose range. MEC90 and MEC99 were estimated using isotonic regression (PAVA), with ropivacaine concentration as the independent variable and binary success/failure as the outcome. Patient-level bootstrap with 2000 resamples was used to derive empirical 95% confidence intervals for the MEC estimates by refitting the isotonic regression for each resample and taking the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution. For each resample, the isotonic regression was re-fitted and the MEC values were recalculated21,22. The 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution define the empirical CIs, which enhances the statistical robustness of the estimators.

Unilateral neuraxial anesthesia cases were excluded from MEC analyses because they were not included in the isotonic regression or bootstrap procedures. Among the remaining bilateral-block datasets, patients who required epidural lidocaine supplementation due to insufficient SA were classified as failures for the overall block-success analyses and are included in Tables 1 and 3, but were excluded from analyses requiring a successful block (Table 2).

To assess the sample size adequacy for extreme quantiles, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation study. The Monte Carlo simulation approach for assessing the performance of estimators under a known data-generating mechanism follows estimated statistical methodology23. The planned sample size (45 successful blocks) was selected to provide acceptable precision for the primary endpoint, MEC90, following up‑and‑down design guidance. We fitted an isotonic (PAVA) dose–response curve to the observed per‑dose success rates and used the fitted probabilities as the data‑generating mechanism. For N = 45, 100, 200, and 400, we allocated patients proportionally across dose levels, simulated n_sim = 1000 trials per N (Bernoulli draws at each dose according to the fitted probabilities), re‑estimated MEC90 and MEC99 by isotonic regression for each simulated dataset, and reported empirical mean, median, standard deviation, 2.5th–97.5th percentiles (empirical 95% CI), and the proportion of simulations in which the estimated MEC exceeded the maximum tested dose (censoring).

Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted via Python 3.12 (Python Software Foundation, URL http://www.python.org) and SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), following standard procedures and guidelines.

Results

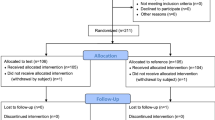

Initially, 51 participants were enrolled to undergo SA, but one participant withdrew from the study because of unilateral SA (Fig. 1); therefore, only 50 patients completed the study (Table 1). Figure 2 illustrates the biased coin design up-and-down sequence, demonstrating the relationship between varying ropivacaine concentrations and the SA outcomes. Graphical representations were generated using Python version 3.12. The graph visualizes successful instances of SA using blue squares, and unsuccessful instances using red circles.

Of the 50 participants included in the analysis, five experienced block failure, which was characterized by the absence of anal sphincter relaxation at the beginning of the surgical procedure and incomplete sensory block in the perineal region within 10 min of anesthesia. However, the participants underwent painless surgery after receiving rescue epidural anesthesia. Anal sphincter laxity is common in such patients.

Using isotonic regression, MEC90 was estimated to be 0.2482% (3.7320 mg, 95% CI 0.1500–0.3000), and MEC99 was subsequently estimated to be 0.2926% (4.4389 mg, 95% CI 0.2500–0.3000).

Analysis of 50 cases showed a concentration-dependent increase in spinal block success with 1.5 mL of 0.15–0.30% concentrations. The success rates increased from 33.3% at 0.15% to 100% at 0.30%, stabilizing at 0.20% or higher. One-way ANOVA indicated significant differences in analgesia duration among the 0.20%, 0.25%, and 0.30% groups (P = 0.037). Post-hoc testing revealed longer analgesia in the 0.30% group than in the 0.20% group (P < 0.05). Detailed values, PAVA-adjusted estimates, means ± SD, and CIs are presented in Table 2.

Table 3. Monte-Carlo results summarizing the distribution of MEC90 and MEC99 estimates across n_sim = 1000 simulated trials for each total sample size N. Empirical 95% CI widths: N = 45, MEC90 = 0.122 and MEC99 = 0.098; N = 100, MEC90 = 0.071 and MEC99 = 0.059; N = 200, MEC90 = 0.067 and MEC99 = 0.018; N = 400, MEC90 = 0.058 and MEC99 = 0.017. Under the assumed dose range and allocation, no simulations produced MEC estimates that exceeded the maximum tested dose (censored_prop = 0). Supplementary Fig. 1 (MEC90 and MEC99 Confidence Interval Precision) shows the CI-width trends across N and the full simulated MEC distributions.

All participants who successfully achieved blockade experienced satisfactory surgical anesthesia. Within this participant cohort, six patients encountered incomplete conduction blockade during the surgical procedure. One participant withdrew from the study because of unilateral SA, whereas the other five participants required supplemental epidural anesthesia to improve inadequate pain relief. Effective rescue epidural blocks were administered to all six participants, facilitating the completion of the surgical procedure without pain. No adverse events were recorded in any cohort during the continuous intraoperative monitoring or the standardized 72-h postoperative surveillance period. This includes the absence of urinary retention, lower-extremity motor blockade, hemodynamic instability, and headaches.

Table 4 shows no significant concentration effect (F(3,46) = 0.303, P = 0.823), time effect (F(4,184) = 0.289, P = 0.843), or concentration–time interaction (F(12,184) = 1.167, P = 0.319) using repeated-measures ANOVA. Crucially, all tested concentrations (0.15–0.30%) maintained hemodynamic stability, with the mean arterial pressure consistently within the optimal perfusion range (92–102 mmHg) and > 60 mmHg safety threshold across all time points24. The maximum intergroup difference never exceeded 9.13 mmHg (T2: 0.15% = 102.33 vs. 0.3% = 93.20), which was far below the 15 mmHg threshold requiring clinical intervention. Although 0.20% ropivacaine showed a transient statistical variation at T3 (Δ + 0.85 mmHg vs baseline, P = 0.044), this represented < 1% change (< 1.5% of procedural MAP fluctuation tolerance) and had no clinical impact.

Discussion

This dose-finding study estimated the MEC90 and MEC99 of hyperbaric ropivacaine for SA in anorectal surgery at 0.248% (3.73 mg) and 0.293% (4.44 mg), respectively, using a 1.5 mL volume of local anesthetic. These concentrations represent a 50.4% and 41.4% reduction in total mass compared to the standard 0.5% dosing (7.5 mg), aligning with enhanced recovery principles through reduced systemic exposure and toxicity.

Compared to seminal studies on ropivacaine dosing for anorectal surgery using caudal block 4,8, our spinal anesthesia protocol achieved a 99% success rate with only 4.389 mg ropivacaine, representing a > 91% dose reduction from previously reported doses (42–72 mg). Even versus unilateral spinal anesthesia in hip surgery25, our dose was 58% lower while targeting a higher efficacy threshold (99% vs. 95%). Three mechanisms explain these discrepancies. First, intrathecal administration bypasses the dura mater, allowing drugs to reach the CSF, which has a higher bioavailability than epidural delivery. Studies have shown that epidural doses can reach 10 times the intrathecal dose before similar CSF drug concentrations are achieved26,27. Second, neuroanatomical precision: spinal administration targets the dorsal root ganglia (L4–S1), bypassing the epidural fat that impedes uptake28. Third, baricity optimization: hyperbaric solutions enable sacral pooling, yielding a 3.8-fold higher concentration at the sacral nerve roots than isobaric agents29. This optimization stems from volume confinement (1.5 ml), enabling sacral sequestration, a paradigm shift from conventional large-volume diffusion.

Derived from the dose-hypotension relationship, our MEC99 estimate (4.4389 mg) was positioned well below the 17.5 mg risk threshold30. This approach guarantees effective treatment while preventing hemodynamic instability, which would require the use of metaraminol at increased doses for rescue30,31. Although derived from obstetric populations, Li et al.’s 2024 findings30 mechanistically support our hemodynamic results.

Ropivacaine, a long-acting amide local anesthetic, exhibits superior selectivity for Aδ and C nerve fibers compared to Aβ fibres6,32,33, which is critical for achieving effective pain relief with minimal motor blockade. Furthermore, owing to its lower lipophilicity, ropivacaine has a higher threshold for cardiovascular and central nervous system toxicities compared to bupivacaine34,35. These pharmacological properties make it a preferred option for SA and peripheral nerve blocks9.

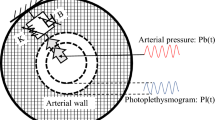

In this study, we selected the lateral midsagittal position of the lumbar spine for SA12. This position improves the needle angle and visualization, aiding accurate puncture localization, particularly in patients with anatomical variations. It also minimizes the risk of spinal cord injury and allows patients to maintain a more relaxed posture, ultimately enhancing the success and safety of the anesthetic procedure. In our practice, intrathecal injections are routinely administered in the lateral position, even when hyperbaric agents are used. While acknowledging that this approach differs from the sitting position techniques commonly employed in Western centers for classic saddle blocks, our choice is rooted in provided an estimate of regional clinical practices that prioritize patient comfort, stability during puncture, and alignment with local training practices. Crucially, the distribution of hyperbaric solutions in the subarachnoid space is influenced not only by gravity but also by diffusion along concentration gradients and CSF dynamics36,37,38,39. Through careful injection technique and appropriate, brief post-injection patient repositioning, this method effectively achieves bilateral perineal anesthesia for anorectal surgery. This demonstrates its clinical efficacy and safety for our target population, providing a targeted low-level block advantageous for day-case surgery by minimizing high spinal effects and promoting rapid recovery.

While experienced anesthesiologists demonstrate an approximately 75% success rate in performing caudal anesthesia for this type of surgery5,40, SA offers a much higher success rate. However, there remains a need for publicly available data on SA MEC specific to anorectal procedures.

Various anesthetic techniques are used in anorectal surgery, including local infiltration, SA, and sacral canal block8,41,42. Among these, SA is particularly notable because of its rapid onset and reliable efficacy. The absence of adverse events, including postdural puncture headache, transient neurological symptoms, urinary retention, and neurological sequelae, aligns with the favorable safety profile of ropivacaine. This null outcome (0/50) corresponds to the rates reported in large cohorts43,44. Although the sample size limits the detection of rare events, our findings support the safety of ropivacaine in ambulatory SA for anorectal procedures.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, the modest sample size may constrain the detection of subtle clinical differences between the groups. Second, as a single-center trial, our findings could be influenced by institution-specific protocols and patient characteristics, limiting their generalizability to broader populations. Third, although we implemented a rigorous double-blind design with blinding of participants, clinicians, and outcome assessors, the single-center setting remains a potential source of homogeneity bias. Additionally, the exclusion of patients aged > 65 years or with significant comorbidities, along with the focus on day-case anorectal surgery (e.g., anal sphincter relaxation requirements), may restrict its applicability to other contexts..

As with any clinical study, our estimates could be influenced by unmeasured confounders. Inter-patient differences in neuroanatomy and CSF dynamics affect drug distribution. Technical variations in needle placement and injection speed introduce variability. The sequential adaptation of the biased-coin design, which bases each dose on the previous response, helps mitigate confounders by focusing on the target concentration estimation. Our findings provide an effective concentration estimate under the study conditions and serve as a starting point for clinical implementation, which requires adjustment for individual factors.

Another significant limitation is the wide confidence interval for the MEC90 (95% CI: 0.1500–0.3000%), indicating potential issues with precision. This variability may be attributed to the limited sample size, variability in outcomes, and nonlinear nature of the dose–response relationship. These factors necessitate caution when interpreting our findings.

Our conclusions on MEC99 precision are conditional on the PAVA-fitted dose–response and proportional allocation used in the simulations. If the true dose–response differs materially (e.g., heavier tails or a substantially higher MEC99), sample sizes larger than those reported here may be required to achieve comparable precision. Thus, the MEC99 estimates in this study should be considered exploratory unless supported by substantially larger samples (under the observed dose–response, we estimate ≳200 successful blocks are required to obtain MEC99 CI widths ≈0.018)45. The Monte Carlo simulation code and full outputs are provided in the Supplementary Material to permit reassessment under alternative assumptions.

Future research with larger sample sizes and advanced statistical methodologies, such as penalized likelihood techniques or enhanced bootstrap methods, could help refine these estimates and improve their applicability to broader patient populations.

Conclusion

In our study on spinal anesthesia during anorectal surgery, 1.5 ml of ropivacaine at 0.2482% (3.7320 mg) achieved a 90% SA success rate, which increased to 99% with 0.2926% (4.4389 mg). These findings suggested an association that lower ropivacaine concentrations can provide effective anesthesia, enhancing safety by reducing potential side effects. Our research supports the development of optimized dosing strategies for day-case surgeries, contributing to patient-centered practices. Future studies should examine these results in diverse populations, assessing recovery times and patient satisfaction with lower doses of the drug. Research on alternative local anesthetics may further optimize spinal anesthesia. In conclusion, our study provides guidance for the effective use of ropivacaine in spinal anesthesia and provides an estimate of a basis for future studies on anesthetic techniques across patient demographics.

Data availability

The data related to this study are included in the attached file titled “Table S1. Dataset of patient demographics, surgical details, and perioperative outcomes for the dose-finding study of intrathecal ropivacaine.” Simulation code and full outputs supporting the sample‑size precision assessment are available in the Supplementary Materials.

References

Feng, J., Xia, P. & Pu, F. Safety and efficacy of topical ropivacaine injection for relieving postoperative pain of spinal tuberculosis: A randomized clinical trial. Asian J. Surg. 46, 1645–1646 (2023).

Schwenk, E. S. et al. Population pharmacokinetic and safety analysis of ropivacaine used for erector spinae plane blocks. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 48, 454–461 (2023).

He, Y. et al. Safety and feasibility of ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block and intercostal nerve block for management of post-sternotomy pain in pediatric cardiac patients: A prospective, randomized trial. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 42, 101268 (2023).

Li, X. et al. The minimum effective concentration (MEC90) of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided caudal block in anorectal surgery A dose finding study. PLoS ONE 16, e0257283 (2021).

Zhang, P. et al. Study on MEV90 of 0.5% ropivacaine for US-guided caudal epidural block in anorectal surgery. Front. Med. 9, 1077478 (2022).

Fang, G., Wan, L., Mei, W., Yu, H. H. & Luo, A. L. The minimum effective concentration (MEC90) of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Anaesthesia 71, 700–705 (2016).

Genc, C. et al. The minimum effective concentration (MEC90) of bupivacaine for an ultrasound-guided suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block for analgesia in knee surgery: A dose-finding study. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 77, 364–373 (2024).

Ma, D. et al. The Minimum effective concentration (MEC95) of different volumes of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided caudal epidural block: a dose-finding study. BMC Anesthesiol. 23, 74 (2023).

Gao, W. et al. The 90% minimum effective volume and concentration of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided median nerve block in children aged 1–3 years: A biased-coin design up-and-down sequential allocation trial. J Clin Anesth 79, 110754 (2022).

Karmakar, M. K., Li, X., Ho, A. M., Kwok, W. H. & Chui, P. T. Real-time ultrasound-guided paramedian epidural access: Evaluation of a novel in-plane technique. Br. J. Anaesth. 102, 845–854 (2009).

Karahan, M. A. et al. The relationship between gestational week and QT dispersion in cesarean section patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia: A prospective study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 75, e14154 (2021).

Liu, Y., Qian, W., Ke, X. J. & Mei, W. Real-time ultrasound-guided spinal anesthesia using a new paramedian transverse approach. Curr. Med. Sci. 38, 910–913 (2018).

Wyles, C. C. et al. More predictable return of motor function with mepivacaine versus bupivacaine spinal anesthetic in total hip and total knee arthroplasty: A double-blinded, randomized clinical trial. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 102, 1609–1615 (2020).

Li, S. et al. The 95% effective dose of intranasal dexmedetomidine sedation for pulmonary function testing in children aged 1–3 years: A biased coin design up-and-down sequential method. J. Clin. Anesth. 63, 109746 (2020).

Cao, R., Li, X., Yang, J., Deng, L. & Cui, Y. The minimum effective concentration (MEC90) of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided quadratus lumborum block for analgesia after cesarean delivery: A dose finding study. BMC Anesthesiol. 22, 410. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-022-01954-5 (2022) (PMID: 36581811).

Drew, T. et al. Carbetocin at elective caesarean section: A sequential allocation trial to determine the minimum effective dose in obese women. Anaesthesia 75, 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14944 (2020) (PMID: 31867715).

Wang, L. et al. Preoperative posterior quadratus lumborum block: Determining the minimum effective ropivacaine concentration in 90% of patients (MEC90) for postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic myomectomy. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 44(2), 101480 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Minimum effective dose of plain bupivacaine 0.5% for ultrasound-guided spinal anaesthesia using Taylor’s approach. Br. J. Anaesth. 124, e230–e231 (2020).

Robert, C. P. & & Casella, G. Monte Carlo Statistical Methods (2nd ed.). Springer, (2004)

Pace, N. L. & Stylianou, M. P. Advances in and limitations of up-and-down methodology: A précis of clinical use, study design, and dose estimation in anesthesia research. Anesthesiology 107, 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.anes.0000267514.42592.2a (2007) (PMID: 17585226).

Hu, J., Li, X., Wang, Q. & Yang, J. Minimum effective concentration of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided transmuscular quadratus lumborum block in total hip arthroplasty: A randomized clinical trial. Braz. J. Anesthesiol. 74, 744461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2023.08.005 (2024) (PMID: 37657517).

Wang, Q. et al. Minimum effective concentration of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided adductor canal + IPACK block in total knee arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Surg. 30, 10225536221122340. https://doi.org/10.1177/10225536221122339 (2022) (PMID: 35975643).

Kedem, B. & Pavlopoulos, H. On the threshold method for rainfall estimation: Choosing the optimal threshold level. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 86(415), 626–633 (1991).

Saugel, B. et al. Intra-operative haemodynamic monitoring and management of adults having noncardiac surgery: A statement from the European society of Anaesthesiology and intensive care. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 42, 543–556 (2025).

Lin, C. et al. ED50 and ED95 of hypobaric ropivacaine during unilateral spinal anesthesia in older patients undergoing hip replacement surgery. Front. Med. 12, 1571574 (2025).

Max, M. B. et al. Epidural and intrathecal opiates: Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma profiles in patients with chronic cancer pain. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 38, 631–641 (1985).

Rose, F. X. et al. Epidural, intrathecal pharmacokinetics, and intrathecal bioavailability of ropivacaine. Anesth. Analg. 105, 859–867 (2007).

Golovac, S. Spinal cord stimulation: uses and applications. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 20, 243–254 (2010).

Paliwal, N., Kokate, M. V., Deshpande, N. A. & Khan, I. A. Spinal anaesthesia using hypobaric drugs: A review of current evidence. Cureus 16, e56069 (2024).

Li, M., Xie, G., Chu, L. & Fang, X. Association between plain ropivacaine dose and spinal hypotension for cesarean delivery: A retrospective study. PeerJ 12, e18398 (2024).

Qian, X. W., Chen, X. Z. & Li, D. B. Low-dose ropivacaine-sufentanil spinal anaesthesia for caesarean delivery: A randomised trial. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 17, 309–314 (2008).

Bader, A. M., Datta, S., Flanagan, H. & Covino, B. G. Comparison of bupivacaine- and ropivacaine-induced conduction blockade in the isolated rabbit vagus nerve. Anesth. Analg. 68, 724–727 (1989).

Rosenberg, P. H. & Heinonen, E. Differential sensitivity of A and C nerve fibres to long-acting amide local anaesthetics. Br. J. Anaesth. 55, 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/55.2.163 (1983) (PMID: 6830678).

Mio, Y. et al. Comparative effects of bupivacaine and ropivacaine on intracellular calcium transients and tension in ferret ventricular muscle. Anesthesiology 101, 888–894 (2004).

Reiz, S., Häggmark, S., Johansson, G. & Nath, S. Cardiotoxicity of ropivacaine—A new amide local anaesthetic agent. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 33, 93–98 (1989).

Flack, S. H. & Bernards, C. M. Cerebrospinal fluid and spinal cord distribution of hyperbaric bupivacaine and baclofen during slow intrathecal infusion in pigs. Anesthesiology 112, 165–173 (2010).

Toro, E. F., Thornber, B., Zhang, Q., Scoz, A. & Contarino, C. A computational model for the dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid in the spinal subarachnoid space. J. Biomech. Eng. 141, (2019).

Pahlavian, S. H. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid dynamics in the cervical spine: importance of fine anatomical structures (2014).

Stockman, H. W. Effect of anatomical fine structure on the dispersion of solutes in the spinal subarachnoid space. J. Biomech. Eng 129, 666–675 (2007).

Sekiguchi, M., Yabuki, S., Satoh, K. & Kikuchi, S. An anatomic study of the sacral hiatus: A basis for successful caudal epidural block. Clin. J. Pain. 20, 51–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200401000-00010 (2004) (PMID: 14668657).

Feo, C. F., Ninniri, C., Tanda, C., Deiana, G. & Porcu, A. Open hemorrhoidectomy with ligasure™ under local or spinal anesthesia: A comparative study. Am. Surg. 89, 671–675. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031348211038590 (2023) (PMID: 34382441).

Verkuijl, S. J., Trzpis, M. & Broens, P. The anorectal defaecation reflex: A prospective intervention study. Colorectal Dis. 24, 845–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.16101 (2022) (PMID: 35194918).

Kalbande, J. V., Kukanti, C., Karim, H., Sandeep, G. & Dey, S. The efficacy and safety of spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric ropivacaine 0.75% and bupivacaine 0.5% in patients undergoing infra-umbilical surgeries: A randomized, double-blind study. Cureus. 16, 57005 (2024).

McClellan, K. J. & Faulds, D. Ropivacaine: An update of its use in regional anaesthesia. Drugs 60, 1065–1093 (2000).

Chevret, S. Statistical Methods for Dose-Finding Experiments (John Wiley & Sons, London, 2006).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Zhu Xianlin from Enshi Prefecture Hospital, Hubei Minzu University, for the design of this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Bureau Joint Health Bureau, Chongqing, China (2023MSXM033), and the Science and Technology Bureau Joint Health Bureau ,Fengdu, Chongqing, China (2024FDKW002). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, publication decisions, or manuscript preparation. No additional external funding was received for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. J. B. Conceptualized the study, acquired funding, prepared the original draft, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. R. D. T. contributed to the conceptualization of the study and participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript. X. J. D., J. L., and J. H. C. conducted the experiments. X. S. Z. performed the statistical analyses. L. C., J. T. S. carried out the investigation and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement

The patients and the public will not be involved in the study design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Dong, X., Chen, J. et al. Determining the optimal ropivacaine concentration for spinal anaesthesia during day surgery for anorectal procedures: a dose-finding study. Sci Rep 15, 40520 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24272-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24272-5