Abstract

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. As new treatments emerge, transparent reporting of adverse events (AEs) in clinical trials is essential to ensure patient safety. However, discrepancies persist in the reporting of serious adverse events (SAEs), other adverse events (OAEs), mortality, and participant withdrawals between clinical trial registries and their corresponding peer-reviewed publications. In this systematic review with a cross-sectional comparative analysis, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov for completed glaucoma randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and matched each record to its corresponding publication by screening PubMed and Google Scholar (27 September 2009–31 December 2024). Data on SAEs, OAEs, mortality, and participant withdrawals were compared between registry entries and corresponding journal publications. Statistical analyses assessed the extent and significance of discrepancies. Among 57 eligible trials, 31.6% showed discrepancies in SAE reporting (p < 0.05), and 77.2% had discrepancies in OAE reporting (p < 0.05), with publications frequently omitting key safety data. Mortality reporting was reported in 61.4% in ClinicalTrials.gov compared to 42.1% in published papers and mortality discrepancies were observed in 47.4% of trials. These findings confirm widespread underreporting or omission of safety data in published literature, raising transparency and ethical concerns. To improve AE reporting accuracy, we recommend stricter journal oversight, enforcement of CONSORT-harms guidelines, and broader adoption of supplementary materials for comprehensive safety data disclosure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is a severe and progressive ophthalmologic condition that poses a significant public health challenge globally. Affecting the optic nerve, glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness in adults over 50 and is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide1. Glaucoma carries a substantial economic burden, with estimates suggesting an annual cost of $2.9 billion- a figure projected to rise to $17.3 billion by 20502,3. While various pharmacological and surgical interventions exist to mitigate vision loss, all treatments carry risks, making accurate and transparent reporting of adverse events (AEs) crucial for evidence-based decision-making. Inadequate AE reporting can misrepresent the safety profile of interventions, influence treatment guidelines, and ultimately affect patient care.

Due to the lack of AE reporting and the importance of properly reporting AEs, members of Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) have published a standard CONSORT checklist with recommendations about reporting harm-related issues4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Despite these guidelines, gaps in reporting harm-related issues persist11. This led the FDA to require investigators to report all AEs, serious adverse events (SAEs), other AEs (OEs), and all-cause mortality occurring with a frequency of 5% or more to ClinicalTrials.gov which was mandated as of September 200912,13. However, even with the requirement to report these harm-related issues it has been demonstrated that there are discrepancies between ClinicalTrials.gov and other trial registry reports to published papers14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. This is concerning as health professionals rely on these papers to assess the risks of interventions. Inadequate reporting of harm-related issues can lead to a biased safety profile and potentially jeopardize patient care.

Glaucoma treatments can involve both medical and surgical interventions that carry significant risks such as ocular inflammation, vision loss, and overall increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Initially our study was aimed to examine the reporting of safety reporting between ClinicalTrials.gov and their corresponding published articles comparing our study to the general literature. However, during the course of our research, we became aware of a recently published study by Krešo et al. which also examined AE reporting discrepancies in glaucoma clinical trials, comparing ClinicalTrials.gov data to journal publications24. Their findings revealed significant inconsistencies in safety reporting in glaucoma clinical trials, reinforcing the overarching theme found in the literature. Given the potential impact of selective AE reporting on patient safety, independent validation of these findings is essential to confirm their generalizability and identify additional contributing factors.

Due to the importance in being able to adequately assess harms related to glaucoma interventions it is imperative that published papers have proper reporting of safety events. This study serves as a replication and expansion of prior research, aiming to independently assess AE reporting completeness in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for glaucoma interventions by comparing registry data to corresponding publications from September 2009 to December 2024. While our objectives align with those of Krešo et al., our study also extends the literature by further discussing recommendations for the future of AE reporting24..

Methods

Study design, ethics, reporting and reproducibility

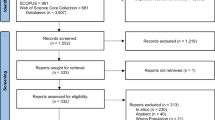

A systematic review methodology was conducted for the search, inclusion, and extraction of data from primary studies. A cross-sectional comparative analysis of the collected data was then conducted. We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) rather than the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines, as our study involved a systematic review and cross-referencing of trial-level data from registries and publications, rather than an observational analysis of individual-level participant data25,26. All versions of our protocol, research data, analysis scripts, and other study artifacts have been uploaded to Open Science Framework (OSF) to promote open science practices and transparency27. Additionally, the complete ClinicalTrials.gov search string is provided in Supplementary File 1.

Search strategy

A retrospective analysis on glaucoma RCTs was complete. On September 30, 2024, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov for completed RCTs using the keywords: “Glaucoma,” “Primary Open Angle Glaucoma\(POAG\),” “Angle-Closure Glaucoma,” “Glaucoma Open-Angle,” and “Glaucoma Eye.” Additional filters included: Completed studies, Phase: 2, 3, 4, Interventional studies, Studies with results, Study Start from 09/27/2009 to 12/31/2023. The same search criteria was used on August 10, 2025 with Study Start from 01/01/2024 to 12/31/2024. The reason 09/27/2009 was chosen was because that was the date when consistent and thorough reporting of harm related events became mandatory by the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) 80. This gave us over 15 years of mandatory safety reporting.

Only trials with publications were included in our study. We only included trials that had results for the National Clinical Trial (NCT) identifier associated with the ClinicalTrials.gov entry and did not include the study if there were other NCT identifiers associated with the published paper. Furthermore, we only included the publication that corresponded to the closest date to when results were first posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. If publications were not listed on ClinicalTrials.gov, we searched for the NCT identifier on Pubmed and Google Scholar. Lastly, if all our initial searches failed, we searched the study title and principal investigators name. Only complete publications were compared with the registered data.

Sample eligibility criteria

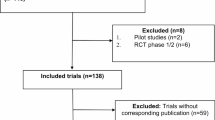

We included trials that (1) RCTs investigating pharmacological, non-pharmacological, surgical, or laser interventions for Glaucoma (2) Registered to ClinicalTrials.gov (3) Completed studies with results (4) Phase: 2, 3, 4, Interventional studies (5) Study start from 09/27/2009 to 12/31/2023. Corresponding articles had to be (1) peer-reviewed, (2) published in English, and (3) indexed on PubMed. Trials without publicly available results on ClinicalTrials.gov or those not linked to a corresponding publication were excluded. Exclusion reasons included: (1) Trials without publicly available results on ClinicalTrials.gov, (2) trials not linked to a corresponding publication, (3) trials other than RCT such as non-randomized clinical trials and observational studies (4) trials not focused on glaucoma interventions, and (5) phase 1 studies. Phase 1 studies were excluded as these studies are typically exploratory and primarily focused on dose-escalation and safety in healthy volunteers. See Fig. 1 for the reasons for the excluded trials in our investigation.

Data extraction and analysis of safety reporting

To ensure transparency in our blinded, duplicate extraction process, we adhered to the STROBE checklist throughout title screening, full-text screening, and data extraction28. Each step was conducted independently and in duplicate by two masked reviewers (MC and SK) using a standardized extraction form and a de-identified spreadsheet in which trials were labeled solely by numeric ID. Reviewers were blinded to each other’s responses during the screening and extraction phases. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (AK) until consensus was achieved. Although formal inter-rater reliability metrics such as kappa coefficients were not calculated, this masked and consensus-driven process was employed to minimize bias and improve the consistency of data collection. The standardized extraction form captured information from each trial’s ClinicalTrials.gov record and its corresponding publication. Extracted data included: NCT identifier, trial start date, primary completion date, date of results posting, trial phase, sponsor, and funding source. Extractions regarding harms related events included: number of SAEs, OAEs, treatment-related withdrawals and discontinuations, reported mortality, differences in description of OAEs between publication and ClinicalTrials.gov, frequency threshold value, and omissions of harms related events. We also assessed the relationship between reporting discrepancies and the time delay between results posting and publication. We tracked the time elapsed between the posting of trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov and the publication date of the corresponding articles. The extraction form used is found in our OSF link27.

Operationalization of discrepancies

Discrepancies in the reporting of harm related events were analyzed by comparing the number of reported SAEs, OAEs, mortality, and patient withdrawals across both sources. A participant-level discrepancy was defined as any numerical mismatch in the number of participants experiencing an AE between ClinicalTrials.gov (“Affected / at Risk (%)”) and the corresponding publication. An event-level discrepancy was defined as any difference in the total number of AEs reported between ClinicalTrials.gov (the “# Events”) and the publication. A descriptive discrepancy was defined as any inconsistency in the labeling or listing of AE types (e.g., if ClinicalTrials.gov listed “uveitis and corneal edema” and “strabismus,” but the publication listed only “strabismus”). An omission was recorded when an AE reported in ClinicalTrials.gov was not mentioned at all in the publication. Finally, a mortality discrepancy was defined as any difference in the number of deaths reported between the two sources. A more detailed view on the discrepancies seen are outlined in Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias (RoB) for each included randomized controlled trial was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2) tool, which evaluates potential bias across five domains: (1) bias arising from the randomization process; (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions; (3) bias due to missing outcome data; (4) bias in measurement of the outcome; and (5) bias in selection of the reported result. All assessments were conducted by a single trained reviewer following the RoB 2 guidance. Domain-level ratings for each trial are presented in Supplementary Figs. 1–4, and the complete set of answered RoB 2 tool forms has been uploaded to the OSF27. Traffic-light heatmaps were auto-generated using the RoB 2 Excel (.xlsm) tool provided by Cochrane, and domain-level summary bar charts (including overall RoB ratings) were generated in R (version 4.3.2).

Comparison of registry and publication safety reporting

We compared safety outcome reporting between ClinicalTrials.gov results entries and corresponding peer-reviewed publications for all included trials. Outcomes assessed included the number of participants with SAEs, total SAE events, the number of participants with OAEs, total OAE events, the OAE frequency threshold, all-cause mortality, and discontinuation due to AEs. For each outcome, zero values were classified as “reported,” whereas blank cells were classified as “not reported.” Trials were classified as having any discrepancy if the numerical values in the registry and publication differed, or if the outcome was reported in one source but not the other. Discrepant trials were further categorized into mutually exclusive subtypes: (1) fewer in publication, (2) more in publication, (3) omitted in publication but registry reports value > 0, (4) omitted in publication but registry reports value = 0, (5) omitted in registry but publication reports value > 0, (6) omitted in registry but publication reports value = 0, and (7) omitted in both publication and registry. The prevalence of discrepancies was expressed as the percentage of discrepant trials with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To evaluate directional bias in reporting presence (reported vs not reported), McNemar’s tests for paired binary data were performed, and discordant pairs odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were calculated. For each “any discrepancy” analysis, both the prevalence (with binomial CI) and the McNemar OR (with CI and p-value) are reported in Table 2. As a secondary descriptive analysis, relative risks (RRs) and absolute risk differences (ARDs) for reporting presence between publications and registries were calculated without accounting for the paired design and are presented in Supplementary Table 1 These measures, along with their 95% confidence intervals, were visualized in a forest plot (Fig. 2). RRs with 95% CIs were estimated using the Katz log method, and ARDs with 95% CIs were estimated using Wald intervals. Effect size reporting was guided by the Statistical Analyses and Methods in the Published Literature (SAMPL) guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility29. All analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.2).

Relative risks and absolute risk differences comparing the presence of AE reporting in publications versus ClinicalTrials.gov Forest plots display RR and ARD with 95% CI for adverse event reporting in publications compared with ClinicalTrials.gov. RR is the ratio of the proportion of trials reporting AEs in publications to the proportion reporting it in the registry; values above 1 indicate a higher reporting rate in publications, and values below 1 indicate a higher reporting rate in the registry The ARD represents the absolute difference in reporting proportions (publication minus registry); values above 0 indicate higher reporting in publications, and values below 0 indicate higher reporting in the registry. Intervals where the 95% CI crosses the null value (RR = 1 or ARD = 0) indicate no statistically significant difference.

Subgroup analysis and correlation with timeline gap

A subgroup analysis was performed to examine whether discrepancies in AE reporting differed between trials published before versus after results were posted to ClinicalTrials.gov. The publication date and “Results First Posted” date from the registry were compared to classify each trial into one of two categories: published before registry posting or published after registry posting. For each discrepancy variable, total SAE differences, participant SAE differences, total OAE differences, participant OAE differences, mortality differences, discontinuations due to AEs, and omissions of SAE or OAE data, binary indicators (present vs absent) were tabulated for each subgroup. Categorical comparisons between subgroups were conducted using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test, as appropriate, and effect estimates were expressed as ORs and RRs with corresponding 95% CIs.

To assess whether the magnitude of discrepancies was associated with the timing of publication relative to registry posting, we calculated a “timeline gap” in days (publication date minus registry results posting date; negative values indicate publication before results posting). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (ρ) with corresponding p-values were calculated between the timeline gap and each binary discrepancy variable. Correlation analyses were conducted separately for participant-based discrepancies, event-based discrepancies, omissions (SAE and OAE), and mortality differences.

Scatter plots with binary y-axes (0 = no discrepancy, 1 = discrepancy present) were generated to visualize the relationship between timeline gap and each discrepancy type. For participant-based and event-based analyses, SAE and OAE variables were plotted in the same figure with separate colors and regression lines; omission and mortality discrepancies were displayed separately. Each plot included the Spearman’s ρ, p-value, and sample size (N) in the subtitle. All analyses and visualizations were performed using 4.3.2. We uploaded our data and the r script used for our analysis to OSF27.

Ethical oversight

The Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences IRB reviewed our protocol (IRB #2,024,138) and determined that our research project qualifies as nonhuman subjects research as defined in regulation 45 CFR 46.102(d) and (f).

Results

A total of 159 registered trials were identified, with 57 (35.8%) meeting the criteria for analysis after screening. The majority of the published trials were phase 3 (n = 24, 42.1%), followed by phase 2 (n = 17, 29.8%) and phase 4 (n = 16, 28.1%). Additionally, 50 (87.7%) of the published trials were industry-sponsored, 4 (7%) were sponsored by universities, 2 (3.5%) by hospitals, and 1 (1.8%) by private individuals. Among the publications, 17 (29.8%) were published before the results of their trials were first posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. The average time between trial results first posted on ClinicalTrials.gov and the corresponding publication was 19.2 months. The median impact factor of the journals in which these trials were published was 3.7 (95% CI 2.34–5.14), with a range spanning from 1.5 to 13.2. See Table 1 for additional study characteristics.

Risk of bias

RoB was evaluated for all 57 included RCTs using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool. Overall RoB was rated as low in 31 trials (54.4%), some concerns in 8 trials (14.0%), and high in 17 trials (29.8%). The most common contributors to high overall risk were issues related to selective reporting and inconsistent or potentially biased outcome measurement. The selection of the reported result domain showed the greatest variability, with only 34 trials (59.6%) rated as low risk, 5 trials (8.8%) rated as some concerns, and 18 trials (31.6%) rated high risk. The majority of trials were rated as low RoB for the randomization process (51/57, 89.5%) and deviations from intended interventions (52/57, 91.2%). A smaller proportion achieved low risk ratings for measurement of the outcome (49/57, 86.0%), with 7 trials (12.3%) judged to be at high risk in this domain. The percentage of trials with a high RoB was higher in the per protocol group (100%) compared to the intention to treat group (16%). All bar graphs and traffic-light heatmaps figures are seen in supplementary Figs. 1–4 and the RoB tables are uploaded to OSF27.

SAE reporting

Discrepancies in SAE reporting were frequent (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 2). The number of participants affected by SAEs differed between ClinicalTrials.gov and the corresponding publication in 18 of 57 trials (31.6%, 95% CI 19.9–45.2), with publications significantly less likely to report the same participant counts as the registry (McNemar OR = 19.00, 95% CI 1.11–326.44, p = 0.0077; RR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.75–0.94; ARD = –15.8%, 95% CI –25.3% to –6.3%). Among these discrepancies, 7 (38.9%) publications reported fewer participants, 2 (11.1%) reported more, 2 (11.1%) omitted the outcome despite the registry reporting a value > 0, and 7 (38.9%) omitted the outcome despite the registry reporting 0.

The total number of SAE events differed in 27 trials (47.4%, 95% CI 34.0–61.0; McNemar OR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.25–1.37, p = 0.2864; RR = 1.16, 95% CI 0.92–1.46; ARD = 10.5%, 95% CI –5.9% to 26.9%). Of these, 4 (14.8%) publications reported fewer events, 1 (3.7%) reported more, 3 (11.1%) omitted the outcome despite the registry reporting a value > 0, 5 (18.5%) omitted the outcome despite the registry reporting 0, and 14 (51.9%) reported events absent from the registry. A difference in the description of SAEs between ClinicalTrials.gov and the corresponding publication was identified in 9 of 23 trials with non-missing data (39.1%, 95% CI 19.7–61.5).

OAE reporting

OAEs showed even greater inconsistency (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 2). The number of participants experiencing OAEs differed in 44 of 57 trials (77.2%, 95% CI 64.2–87.3; McNemar OR = 25.00, 95% CI 1.48–422.24, p = 0.0015; RR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.69–0.90; ARD = –21.1%, 95% CI –31.6% to –10.5%). Among discrepant trials, 4 (9.1%) publications reported fewer participants, 28 (63.6%) reported more, 11 (25.0%) omitted the outcome despite the registry reporting a value > 0, and 1 (2.3%) omitted the outcome despite the registry reporting 0.

The total number of OAE events differed in 51 trials (89.5%, 95% CI 78.5–96.0; McNemar OR = 0.05, 95% CI 0.01–0.25, p < 0.001; RR = 2.16, 95% CI 1.60–2.92; ARD = 50.9%, 95% CI 36.8%–65.0%). Of these, 8 (15.7%) publications reported fewer events, 12 (23.5%) reported more, 1 (2.0%) omitted the outcome despite the registry reporting 0, and 30 (58.8%) reported events absent from the registry. A difference in the description of OAEs was observed in 43 of 57 trials with non-missing data (75.4%, 95% CI 62.2–85.9).

An OAE frequency threshold was discrepant in 49 trials (86.0%, 95% CI 74.2–93.7; McNemar OR = 51.00, 95% CI 3.10–837.71, p < 0.001; RR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.45–0.71; ARD = –43.9%, 95% CI –56.7% to –31.0%), and among trials where both sources reported a threshold, 24 (75.0%) differed in value.

Deaths and participant discontinuation due to AEs

Mortality reporting differed in 27 of 57 trials (47.4%, 95% CI 34.0–61.0; McNemar OR = 2.29, 95% CI 1.03–5.13, p = 0.0543), with publications less likely to report deaths than the registry. Numeric mortality discrepancies were present in 27 trials (47.4%), most often due to underreporting in publications (19/27, 70.4%), while 8/27 (29.6%) reported more deaths than the registry. Mortality reporting was reported in 61.4% in ClinicalTrials.gov compared to 42.1% in published papers.

Discontinuations due to AEs differed in 19 trials (33.3%, 95% CI 21.4–47.1), with 7 (36.8%) publications reporting fewer discontinuations, 3 (15.8%) reporting more, and 1 (5.3%) omitting the outcome despite the registry reporting a value > 0; no trials omitted the outcome when the registry reported a value = 0.

Effect of publication timing on AE reporting

When stratified by publication timing, omission of SAE data was substantially more frequent in trials published before registry posting (7/17 [41.2%]) compared with those published after (2/40 [5.0%]), a difference that was statistically significant (OR = 12.53, 95% CI 1.99–141.97; RR = 8.24, 95% CI 1.90–35.66; p = 0.0018). Differences in the number of participants with SAEs were present in 8/17 (47.1%) trials published before registry posting and 10/40 (25.0%) published after (OR = 2.62, 95% CI 0.68–10.25; RR = 1.88, 95% CI 0.90–3.93; p = 0.1262), while differences in the total number of SAE events were observed in 8/17 (47.1%) and 18/40 (45.0%) trials, respectively (OR = 1.08, 95% CI 0.30–3.93; RR = 1.05, 95% CI 0.57–1.92; p = 1.0000).

For OAEs, omission was infrequent in both groups (2/17 [11.8%] published before registry posting vs 3/40 [7.5%] published after; OR = 1.63, 95% CI 0.12–15.77; RR = 1.57, 95% CI 0.29–8.56; p = 0.6289). Differences in the number of participants with OAEs occurred in 12/17 (70.6%) trials published before registry posting and 32/40 (80.0%) published after (OR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.14–2.84; RR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.63–1.24; p = 0.4988), while differences in total OAE events were seen in 14/17 (82.4%) and 37/40 (92.5%) trials, respectively (OR = 0.39, 95% CI 0.05–3.23; RR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.70–1.13; p = 0.3492).

Mortality discrepancies were present in 10/17 (58.8%) trials published before registry posting versus 19/40 (47.5%) published after (OR = 1.57, 95% CI 0.43–5.92; RR = 1.24, 95% CI 0.74–2.07; p = 0.5648). Differences in the number of participants discontinued due to AEs were significantly less frequent in trials published before registry posting (2/17 [11.8%]) than in those published after (17/40 [42.5%]) (OR = 0.19, 95% CI 0.02–0.97; RR = 0.28, 95% CI 0.07–1.07; p = 0.0322). See Table 3 for Pre vs Post Registry Publication effect on Discrepancies & Omissions.

Correlation analyses between the timeline gap (days between publication and results posting) and binary discrepancy outcomes showed no significant association for participant-based OAE discrepancies (ρ = 0.180, p = 0.1792) or SAE discrepancies (ρ = − 0.219, p = 0.1015). Similarly, no correlation was observed for event-based OAE discrepancies (ρ = 0.028, p = 0.8374) or SAE discrepancies (ρ = − 0.092, p = 0.4958). In contrast, SAE omission demonstrated a strong negative correlation with the timeline gap (ρ = − 0.405, p = 0.0018), indicating that publication before registry posting was associated with a higher likelihood of omitting SAE data. Mortality discrepancies also showed a significant negative correlation with the timeline gap (ρ = − 0.326, p = 0.0132), suggesting that trials published before registry posting were more likely to differ in reported deaths between registry and publication. No correlation was found for OAE omission (ρ = 0.026, p = 0.8455). See Fig. 3 for the correlations between pre-post reporting timelines and their correlation with discrepancy magnitude.

Timing of publication and registry results in relation to AE reporting discrepancies Scatter plots show the relationship between the number of days between publication date and the date results were first posted on ClinicalTrials.gov (negative values indicate publication date before registry results first posted; positive values indicate publication date after registry results first posted) and the presence of discrepancies in adverse event reporting. A discrepancy is defined as a difference between the data reported in the publication and the corresponding data in the registry for the same outcome. Panels depict participant-based differences, event-based differences, and mortality discrepancies. Omissions were also analyzed. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (ρ) and p-values are shown for each panel.

Discussion

Across the 57 glaucoma RCTs included in our systematic review with cross-sectional comparative analysis, safety data were often inconsistent between ClinicalTrials.gov and the corresponding publications. Discrepancies were observed for participant counts in SAEs in 18 trials (31.6%) and for SAE event counts in 27 trials (47.4%). For OAEs, discrepancies affected participant counts in 44 trials (77.2%) and event counts in 51 trials (89.5%). Mortality reporting differed in 27 trials (47.4%), while discontinuations due to AEs differed in 19 trials (33.3%). These findings build on those of Krešo et al., providing quantitative estimates of the magnitude of safety reporting gaps in ophthalmology trials and underscoring the need for measures such as uniform adherence to CONSORT-Harms and the mandatory posting of structured safety tables to improve transparency.

Our findings are consistent with those of Kreso et al. (2024), who examined 79 glaucoma trials in ClinicalTrials.gov and identified widespread discrepancies in the number of participants experiencing AEs24. In our sample of RCTs, 31.6% of studies showed discrepancies in the number of participants with SAEs compared to 20% in Kreso et al., while 77.2% showed discrepancies in participants experiencing OAEs compared to their reported 87%. They similarly observed that publications reported fewer participants experiencing SAEs than the registry, and that participants experiencing OAEs were more frequently reported in the publication. Extending beyond their approach, we also compared the number of events reported in ClinicalTrials.gov and in publications, in addition to participant counts. This distinction is important, as the number of events can reveal the frequency and burden of safety outcomes within a trial, particularly relevant in ophthalmology, where outcomes may be measured per eye, and one eye may serve as a control. Event counts therefore provide a more granular view of safety that participant-level reporting alone may miss which our study also found significant discrepancies in OAEs. Our study further builds on Kreso et al. by quantifying the magnitude of discrepancies by visualizing effect size differences in a forest plot, examining pre versus post-results registry posting timing, and assessing methodological quality using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool. Together, these additional analyses offer a complementary perspective, yielding greater insight into both the prevalence and potential impact of safety reporting discrepancies in glaucoma trials.

A concerning challenge in current research practices is the selective outcome reporting bias wherein published articles tend to emphasize primary outcomes with larger effect sizes while minimizing or omitting the reporting of undesired effects. While it may be exciting to publish positive results of a project the authors worked hard on, it is still imperative that authors publish all aspects of the data regarding their projects. Not being transparent can lead to bias that not only distorts the safety profile of treatments but also undermines the integrity of evidence synthesis, potentially affecting clinical decision-making. Our results align with numerous other studies that have highlighted discrepancies in the reporting of safety events between ClinicalTrials.gov and published articles7,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. For example, Hartung et al. reported similar findings to our study in that in published articles AEs were being omitted or underreported, mortality was underreported, and that there were discrepancies in SAE reporting17. A meta-analysis by Golder et al. revealed that across 11 studies comparing AE reporting, unpublished versions consistently documented a higher number of AEs, including serious AEs, than their published counterparts. In many cases, these events were entirely omitted from the published papers19.

Our RoB 2 assessment reveals that although a majority of included glaucoma RCTs (54%) were rated low overall RoB, a substantial proportion exhibited possible reporting bias in domain 5 (selection of the reported result), a pattern that echoes findings from other methodological research on trial transparency. Notably, Michael et al.39 found that in surgical glaucoma RCTs, over one-third of registered trials displayed outcome reporting bias, underscoring that these transparency concerns extend beyond our dataset and across glaucoma specialties. In a 2010 analysis of Cochrane reviews, Kirkham et al. found that 55% (157/283) did not include complete primary outcome data from all eligible trials40. This highlights an enduring issue in which important outcomes, including AEs, are selectively omitted or incompletely reported. While the ROB 2 assessment provides context to the trials analyzed, it is important to note, however, that our investigation primarily focused on the completeness and consistency of AE reporting between ClinicalTrials.gov and corresponding publications, an issue of reporting transparency rather than methodological bias within each trial. Following the advice of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chapter 8, Sect. 8.7) we analyzed the selective omission of outcomesAE data at the review level rather than exclusively through RoB 2.0 assessments for individual trials41,42. By integrating trial-level RoB 2.0 judgments with our review-level analysis of AE discrepancies, our study provides a more comprehensive appraisal of both methodological quality and transparency in safety reporting, and demonstrates that bias in outcome data sometimes including AE reporting remains a significant and unresolved challenge in ophthalmology clinical trials. A notable observation when conducting our ROB assessment was that AEs were often not pre-specified under the outcome measures section in ClinicalTrials.gov, suggesting that safety endpoints may not be treated as an outcome measure which could contribute to their inconsistent and incomplete reporting.

A problem concerning safety reporting in published articles is that even after federal regulations there are still insufficiencies in reporting. Our findings align with a 2020 study by Talebi et al. who found that even after a decade after the FDA Amendments Act (FDAAA) implementation in 2007 that required reporting of harms related events, there is still a clear demonstration of a lack of safety reporting in published articles especially in reporting of SAEs18. While the implementation of the FDAAA was a pivotal step towards improving primary outcome and safety reporting in clinical trials, our results, alongside those of other researchers, indicate that it has been insufficient to ensure comprehensive reporting in published literature. Addressing this ongoing issue is crucial, and immediate action is needed to enhance the understanding of safety in glaucoma research and improve patient care.

A notable finding in our study was that 87.7% of included trials were sponsored by industry. While industry funding is essential for advancing therapeutic development, previous research has shown that industry-sponsored trials may be more prone to selective outcome reporting or underreporting of harms43,44,45. These discrepancies may be influenced by underlying factors related to the regulatory environment or commercial considerations. For instance, detailed reporting of SAEs could potentially raise concerns during regulatory review or affect how a product is perceived by clinicians and patients. As such, selective reporting may occur, intentionally or unintentionally, as part of broader efforts to present a favorable safety profile. Although our study was not powered to compare discrepancies by funding source, the predominance of industry-funded studies in our sample raises the possibility that sponsorship-related factors may have influenced the observed discrepancies in AE reporting. Future studies with sufficient power should investigate this relationship directly.

A potential contributor to discrepancies in AE reporting is the temporal disconnect between journal publication and ClinicalTrials.gov results posting. In several cases, trial results were published before being uploaded to the registry, which may result in incomplete or selectively reported AE data. Unlike ClinicalTrials.gov, which requires systematic and comprehensive disclosure of both serious and non-serious AEs, journal publications are often constrained by space and rely on author discretion. Researchers may prioritize rapid publication, sometimes of interim findings or subgroup analyses, before completing final data submission to the registry. Additionally, some investigators may delay or fail to update registry entries due to lack of awareness, administrative oversight, or in some cases, deliberate avoidance of reporting unfavorable findings. Journals often emphasize timely dissemination, while ClinicalTrials.gov imposes a more structured and bureaucratic reporting process. This temporal mismatch can result in discrepancies, as harms related data reported in publications may not reflect the full safety dataset later required in the registry or may ultimately conflict with it. Our subgroup analysis found that trials published before registry result availability were significantly more likely to omit SAE reporting altogether, with an eightfold increase in odds compared to those published afterward. This finding was reinforced by our correlation analysis, which showed a strong negative association between the timeline gap and SAE omission (ρ = − 0.405, p = 0.0018), indicating that when publications were posted before results were posted on registry, they were linked to higher omission rates. While the mortality discrepancy rate was non-significant in the difference between discrepancies pre and post registry submission, there was a high discrepancy rate regardless if publications were posted before (58.5%) or after (47.5) and also demonstrated a similar negative correlation (ρ = − 0.326, p = 0.0132), suggesting that earlier publications were more likely to differ in reported deaths between registry and publication. This finding supports the concern that earlier publications may rely on preliminary or incomplete datasets, leading to selective or inconsistent safety disclosures.

In contrast to the SAE subgroup, binary omissions of OAE reporting were not significantly associated with whether the publication occurred before or after trial results were posted to ClinicalTrials.gov. It is possible that non-SAEs are more likely to happen in these clinical trials and happen earlier, and thus more likely to have at least an inclusion of one OAE in the publication. A concern however is that OAEs discrepancies are prevalent regardless if the paper was published before or after the registry entry. For example, more than two-thirds of trials in both pre and post registry posting groups had discrepancies in the number of events, with similarly high proportions showing discrepancies in the number of affected participants. This may suggest that OAE reporting inconsistencies are widespread regardless of timing, possibly reflecting lower regulatory emphasis or clarity around OAE reporting compared to SAEs. Importantly, OAEs can have meaningful clinical implications, as they may influence treatment selection, dosing decisions, and patient counseling. Therefore, the high absolute prevalence of OAE discrepancies underscores the need for clearer definitions, standardized thresholds, and explicit reporting requirements for OAEs in clinical trials.

Temporal misalignment may thus undermine reporting transparency and hinder systematic evidence synthesis. Our findings align with broader calls for enhanced enforcement of trial registration policies, and for journals to verify registry postings prior to peer review and publication. Journal verification of registry postings before peer review and publication is widely endorsed as a practical measure to enhance transparency and accountability. Leading organizations, including the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), require prospective trial registration, at or before trial initiation, as a condition for publication in member journals. The ICMJE also encourages journals to ensure that registry entries are complete and up to date, and that registry results are properly cross-referenced in the manuscript46 Similarly, the World Health Organization emphasizes the ethical imperative to maintain accurate trial information, recommending that registry data be kept current and compliant with established international standards47. Additional strategies could include automated registry-publication linkage audits or improved trial tracking infrastructure to prevent data discrepancies rooted in timing gaps.

A recent study by Junqueira et al. critically evaluated the current relevance of the CONSORT guidelines, highlighting that although these guidelines have markedly improved the reporting quality of clinical trials, they have become outdated and require revision to keep pace with evolving research practices and challenges48. The CONSORT-Harms extension, an adjunct to the core CONSORT statement that provides ten explicit recommendations for the complete and transparent reporting of AEs, was introduced in 2004 but remains under-utilized. This observation is particularly relevant in the context of our findings, which demonstrate ongoing gaps in the reporting of harm-related outcomes, including SAEs and mortality. Despite CONSORT’s specific recommendations for harm-related reporting, many studies still fail to present consistent and comprehensive safety data in their publications. The insights from Junqueira et al. underscore the urgency of revising and strengthening CONSORT guidelines to address emerging issues in clinical trial reporting48. Potential updates could include more explicit requirements for disaggregating and reporting safety data, clearer definitions of AEs, and stronger mechanisms for ensuring compliance during peer review and publication. Incorporating these changes could mitigate the selective-outcome-reporting bias identified in our study and enhance the reliability of safety data.

Furthermore, we agree with Golder et al. that urgent policy action is needed to make all AE data readily accessible to the public in a transparent and unrestricted manner19. This would ensure clinicians have a complete picture of the harms associated with glaucoma therapy. We encourage investigators to submit their safety data even when effect sizes are small and AEs are unfavorable, thereby reducing reporting bias and improving the safety evidence base. Until AE reporting in journal articles improves, clinicians should consult ClinicalTrials.gov to assess the full risk profile of glaucoma treatments. Although published articles summarize harms, they rarely provide a comprehensive account; ClinicalTrials.gov can therefore serve as a vital supplementary source. Lack of space, stemming from character or word limits, is often cited as a barrier to complete safety reporting17,49. However, the CONSORT-Harms extension emphasizes that AE data should be fully reported and, when space is limited, supplied as supplementary material or deposited in online repositories. When AE data are not systematically assessed, authors should explicitly acknowledge these limitations in their publications.

Additionally, we believe that journals should be more involved in ensuring comprehensive reporting of safety reporting in Glaucoma publications. Talebi et al. recommend a three-pronged strategy to promote congruent reporting of trial results across ClinicalTrials.gov and peer-reviewed publications. This includes: (1) a checklist for investigators to use pre-submission, (2) acknowledgment of any known discrepancies in the submitted manuscript, and (3) a post-submission check by journal editors to verify consistency between the manuscript and registry entry18. In our study, where AE data were frequently omitted or altered, the implementation of such editorial checks, particularly the third recommendation, could serve as a critical safeguard to enhance reporting transparency and mitigate bias in the dissemination of glaucoma trial results18. Requirement of supplementary documents or use of open-source platforms such as OSF could be an easy implementation to allow authors to submit additional data, raw data, and detailed accounts of the AEs not reported in the manuscript. By reviewing the manuscript submission even after it has been submitted, journals can ensure that all relevant safety information is adequately detailed. This oversight mechanism can prevent overlooking or underreporting of important findings. Furthermore, the formation of a consortium of ophthalmology journals or partnership with organizations like the ICMJE to standardize safety reporting across publications could help ensure consistency of reporting across studies. Additionally, automated algorithms can be developed to flag potential AE discrepancies, omitted safety outcomes, or inconsistent descriptions. These tools could integrate with existing peer-review workflows to catch inconsistencies prior to publication.

The underreporting of AEs, particularly in high-risk interventions such as glaucoma surgeries, has serious clinical, ethical, and legal implications. Clinically, omission of safety data may mislead physicians into underestimating the risks associated with surgical procedures, leading to inappropriate treatment decisions, preventable patient harm, and suboptimal outcomes. This may compromise evidence-based guidelines and contribute to widespread mismanagement. Ethically, selective reporting of AEs violates core principles such as non-maleficence and respect for patient autonomy. Patients have the right to be fully informed of known risks, and incomplete disclosure undermines this right, potentially invalidating informed consent. Additionally, selective reporting may constitute misconduct under the U.S. Office of Research Integrity (ORI), which defines falsification as “the suppression or distortion of data,” including the omission of adverse outcomes or the manipulation of findings to misrepresent safety50,51,52. Legally, the failure to report serious AEs may violate federal mandates such as the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007, which requires timely and comprehensive disclosure of trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov53. In cases where patients experience harm due to undisclosed risks, sponsors, investigators, or institutions may face legal liability. Beyond individual studies, inadequate AE reporting compromises the integrity of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, distorting the scientific evidence base and undermining clinical practice guidelines. It also diminishes the utility of trial registries as instruments of research transparency and public accountability. The consequences of such reporting gaps are magnified in ophthalmology, where even minor complications from procedures like trabeculectomy or tube shunt implantation can result in irreversible vision loss. Moreover, underreporting disproportionately impacts vulnerable populations, including elderly patients, ethnic minorities, non–English speakers, and individuals with limited health literacy, who are less likely to have their AEs captured in voluntary safety systems, thereby exacerbating their risk of harm50,54,55. These findings underscore the need for harmonized and enforceable safety reporting standards across both registries and publications, particularly in high-stakes surgical domains such as ophthalmology.

Replication is a cornerstone of scientific research, ensuring that findings are robust, reliable, and reproducible across different datasets and methodologies. Differences in research interpretation, data extraction methods, and analytical approaches can lead to variations in reported results, reinforcing the need for independent verification. Even when analyzing the same dataset, subtle differences in inclusion criteria, AE classification, or statistical adjustments can lead to differing conclusions. By replicating prior findings, our study further highlights the lack of robustness in AE reporting and calls for ongoing efforts to improve regulatory and clinical decision-making. Ensuring the reproducibility of results is critical in guiding regulatory and clinical decision-making, ultimately improving patient safety and the integrity of medical research.

Our systematic review and cross-sectional comparative analysis had both strengths and limitations. Among the strengths, we employed a masked, duplicate design for screening and data extraction, performed independently by each author (MC, SK) to mitigate bias. Additionally, we developed a protocol a priori and made it publicly available on OSF27. We adhered to PRISMA guidelines, ensuring transparency and clarity in reporting our methodology, and enhancing the reproducibility of our findings by providing detailed descriptions of our search strategy, inclusion criteria, data extraction, and analysis methods. While our study offers valuable insights into safety reporting in glaucoma research, it has several limitations. First, our analysis was limited to trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov and those published in English, potentially excluding relevant data from other registries or languages. Our reliance on publicly available data may not fully capture the underlying reasons for reporting discrepancies, such as intentional omissions or methodological challenges. Furthermore, our search strategy may not have identified all relevant studies, and there might have been possibilities for data extraction errors. Additionally, our RoB assessment was conducted by a single reviewer, which may introduce potential subjectivity. However, to enhance transparency and reproducibility, each domain and item-level judgment was accompanied by a detailed written rationale documenting the basis for the assigned rating.

Future research should extend this analysis to other therapeutic areas within the field of ophthalmology to determine whether similar discrepancies exist. Additionally, qualitative studies should be conducted to explore the factors contributing to these discrepancies such as looking into the reasons authors decided to omit certain data points or why certain SAEs were not reported to obtain better insights into the underlying cause of these issues. These qualitative studies will help guide future policy changes to enhance the reporting of harm related events in published works. Additionally, as reforms such as CONSORT harms and the FDAAA Final Rule (2017) continue to be implemented, long-term studies should assess whether compliance rates improve over time and whether new enforcement strategies are needed. Additionally, future studies should look at the specific AEs that are being omitted within the field of Ophthalmology to identify trends related to specific AE patterns.

Across glaucoma randomized trials, we found frequent differences between journal articles and ClinicalTrials.gov in how they reported serious and OAEs, deaths, and withdrawals. These appear to be systematic problems due to uneven definitions, timing gaps between registry updates and publication, and too few routine cross-checks. A practical path forward is to standardize harms reporting (e.g., CONSORT-Harms) with structured safety tables; align registry posting with publication workflows; and adopt clear, auditable processes for resolving discrepancies and issuing updates. These steps would reduce omissions, improve comparability, and provide clinicians and patients with more reliable safety information.

Data availability

The dataset and analyses reported in this article are available at Open Science Framework repository: https://osf.io/mxsh4/?view_only = 64d7d50a411a4108be592f28217d5e3f.27.

References:

GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators & Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health 9, e144–e160 (2021).

Allison, K., Patel, D. & Alabi, O. Epidemiology of glaucoma: The past, present, and predictions for the future. Cureus 12, e11686 (2020).

Thomas, S., Hodge, W. & Malvankar-Mehta, M. The cost-effectiveness analysis of teleglaucoma screening device. PLoS ONE 10, e0137913 (2015).

Ioannidis, J. P. A. et al. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: An extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 141, 781–788 (2004).

Zorzela, L. et al. Quality of reporting in systematic reviews of adverse events: Systematic review. BMJ 348, f7668 (2014).

Saini, P. et al. Selective reporting bias of harm outcomes within studies: Findings from a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 349, g6501 (2014).

Péron, J., Maillet, D., Gan, H. K., Chen, E. X. & You, B. Adherence to CONSORT adverse event reporting guidelines in randomized clinical trials evaluating systemic cancer therapy: A systematic review. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 3957–3963 (2013).

Sivendran, S. et al. Adverse event reporting in cancer clinical trial publications. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 83–89 (2014).

Hodkinson, A., Kirkham, J. J., Tudur-Smith, C. & Gamble, C. Reporting of harms data in RCTs: A systematic review of empirical assessments against the CONSORT harms extension. BMJ Open 3, e003436 (2013).

Smith, S. M. et al. Adherence to CONSORT harms-reporting recommendations in publications of recent analgesic clinical trials: An ACTTION systematic review. Pain 153, 2415–2421 (2012).

Pitrou, I., Boutron, I., Ahmad, N. & Ravaud, P. Reporting of safety results in published reports of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 169, 1756–1761 (2009).

Health and Human Services Department. Clinical Trials Registration and Results Information Submission. Federal Register Preprint at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/21/2016-22129/clinical-trials-registration-and-results-information-submission.

ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/policy/fdaaa-801-final-rule.

Tang, E., Ravaud, P., Riveros, C., Perrodeau, E. & Dechartres, A. Comparison of serious adverse events posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and published in corresponding journal articles. BMC Med. 13, 189 (2015).

Riveros, C. et al. Timing and completeness of trial results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and published in journals. Plos Med. 10, e1001566 (2013).

Becker, J. E. & Ross, J. S. Reporting discrepancies between the clinicaltrials.gov results database and peer-reviewed publications. Ann. Intern. Med. 161, 760 (2014).

Hartung, D. M. et al. Reporting discrepancies between the ClinicalTrials.gov results database and peer-reviewed publications. Ann. Intern. Med. 160, 477–483 (2014).

Talebi, R., Redberg, R. F. & Ross, J. S. Consistency of trial reporting between ClinicalTrials.gov and corresponding publications: One decade after FDAAA. Trials 21, 675 (2020).

Golder, S., Loke, Y. K., Wright, K. & Norman, G. Reporting of adverse events in published and unpublished studies of health care interventions: A systematic review. Plos Med. 13, e1002127 (2016).

Hughes, S., Cohen, D. & Jaggi, R. Differences in reporting serious adverse events in industry sponsored clinical trial registries and journal articles on antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 4, e005535 (2014).

Pranić, S. & Marušić, A. Changes to registration elements and results in a cohort of Clinicaltrials.gov trials were not reflected in published articles. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 70, 26–37 (2016).

Rodgers, M. A. et al. Reporting of industry funded study outcome data: Comparison of confidential and published data on the safety and effectiveness of rhBMP-2 for spinal fusion. BMJ 346, f3981 (2013).

Paladin, I. & Pranić, S. M. Reporting of the safety from allergic rhinitis trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov and in publications: An observational study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 22, 262 (2022).

Krešo, A., Grahovac, M., Znaor, L. & Marušić, A. Safety reporting in trials on glaucoma interventions registered in ClinicalTrials.gov and corresponding publications. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 27762 (2024).

PRISMA 2020 statement —. PRISMA statement https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/.

Vassar, M., Khan, S., Khan, A., Elghzali, A. & Chaudhry, M. Adverse Event Reporting Discrepancies in glaucoma clinical trials. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MXSH4 (2025).

STROBE - Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. STROBE https://www.strobe-statement.org/.

Lang, T. A. & Altman, D. Basic statistical reporting for articles published in biomedical journals: The ‘statistical analyses and methods in the published literature’ or the SAMPL guidelines. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 52, 5–9 (2015).

Wong, E. K. et al. Selective reporting bias in randomised controlled trials from two network meta-analyses: Comparison of clinical trial registrations and their respective publications. BMJ Open 9, e031138 (2019).

Wieseler, B., Kerekes, M. F., Vervoelgyi, V., McGauran, N. & Kaiser, T. Impact of document type on reporting quality of clinical drug trials: A comparison of registry reports, clinical study reports, and journal publications. BMJ 344, d8141 (2012).

Wieseler, B. et al. Completeness of reporting of patient-relevant clinical trial outcomes: Comparison of unpublished clinical study reports with publicly available data. Plos Med. 10, e1001526 (2013).

Mattila, T. et al. Insomnia medication: Do published studies reflect the complete picture of efficacy and safety?. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21, 500–507 (2011).

Köhler, M. et al. Information on new drugs at market entry: Retrospective analysis of health technology assessment reports versus regulatory reports, journal publications, and registry reports. BMJ 350, h796 (2015).

Hemminki, E. Study of information submitted by drug companies to licensing authorities. Br. Med. J. 280, 833–836 (1980).

Maund, E. et al. Benefits and harms in clinical trials of duloxetine for treatment of major depressive disorder: Comparison of clinical study reports, trial registries, and publications. BMJ 348, g3510 (2014).

Le Noury, J. et al. Restoring study 329: Efficacy and harms of paroxetine and imipramine in treatment of major depression in adolescence. BMJ 351, h4320 (2015).

Hodkinson, A., Gamble, C. & Smith, C. T. Reporting of harms outcomes: A comparison of journal publications with unpublished clinical study reports of orlistat trials. Trials 17, 207 (2016).

Michael, R., Zhang, H., McIntyre, S., Cape, L. & Toren, A. Examining bias in published surgical glaucoma clinical trials. J. Glaucoma 33, 8–14 (2024).

Kirkham, J. J. et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 340, c365 (2010).

Page, M. J. & Higgins, J. P. T. Rethinking the assessment of risk of bias due to selective reporting: A cross-sectional study. Syst. Rev. 5, 108 (2016).

Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. https://www.cochrane.org/authors/handbooks-and-manuals/handbook/current/chapter-08.

Lundh, A., Lexchin, J., Mintzes, B., Schroll, J. B. & Bero, L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, MR000033 (2017).

Lundh, A., Lexchin, J., Mintzes, B., Schroll, J. B. & Bero, L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 44, 1603–1612 (2018).

Siena, L. M., Papamanolis, L., Siebert, M. J., Bellomo, R. K. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. Industry involvement and transparency in the most cited clinical trials, 2019–2022. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2343425 (2023).

De Angelis, C. et al. Clinical trial registration: A statement from the international committee of medical journal editors. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 1250–1251 (2004).

Responsibility, M. International Standards for Clinical Trial Registries. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/274994/9789241514743-eng.pdf.

Junqueira, D. R. et al. CONSORT Harms 2022 statement, explanation, and elaboration: Updated guideline for the reporting of harms in randomized trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 158, 149–165 (2023).

Ioannidis, J. P. & Lau, J. Completeness of safety reporting in randomized trials: an evaluation of 7 medical areas. JAMA 285, 437–443 (2001).

Simon, G. & Christian, M. 6 the Revision of the Credit Derivative Definitions in the Context of the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Selective Reporting of Results. https://ori.hhs.gov/selective-reporting-results.

Travitz, H. 3.1 Description of Research Misconduct. https://cse.memberclicks.net/3-1-description-of-research-misconduct.

ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/policy/fdaaa-801-final-rule.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Adverse Event Reporting. U.S. Food and Drug Administration https://www.fda.gov/drugs/spotlight-cder-science/sociodemographic-characteristics-adverse-event-reporting (2024).

Schulson, L. B., Novack, V., Folcarelli, P. H., Stevens, J. P. & Landon, B. E. Inpatient patient safety events in vulnerable populations: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 30, 372–379 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the intellectual development of this protocol. Authors AE, MC, SK, AK were involved in drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; curation of data; screening and extraction of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of the data; writing of the original draft and copy edits. Author MV was involved in drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design and conceptualization; analysis or interpretation of data, and curation of data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elghzali, A., Chaudhry, M., Khan, S. et al. Systematic review with cross sectional comparative analysis identifies adverse event reporting discrepancies between ClinicalTrials.gov and published glaucoma randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep 15, 40563 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24290-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24290-3