Abstract

Accurate identification of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the prehospital setting is important for timely treatments that reduce damage to the compromised myocardium. Current machine learning approaches lack sufficient performance to safely rule-in or rule-out ACS. Our goal is to identify a method that bridges this gap. To do so, we retrospectively evaluate two promising approaches, an ensemble of gradient boosted decision trees (GBDT) and selective classification (SC) on consecutive patients transported by ambulance to the ED with chest pain and/or anginal equivalents. On the task of ACS classification with 23 prehospital covariates, we found the fusion of the two (GBDT+SC) improves the best reported sensitivity and specificity by 8% and 23% respectively. Accordingly, GBDT+SC is safer than current machine learning approaches to rule-in and rule-out of ACS in the prehospital setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate identification of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the prehospital setting is important for timely treatments that reduce damage to the compromised myocardium. Accordingly, the community has developed Machine Learning (ML) methods to improve the prediction of ACS with prehospital covariates1,2. Nevertheless, performance remains insufficient for safe rule-out or rule-in of ACS3. Current research in cardiovascular disease detection from ECG has observed a possible trade-off between performance and coverage (i.e. percentage of cases to automatically classify) as a viable way to mitigate errors4,5,6. This trade-off is known as selective classification7,8 and it provides more accurate predictions by identifying a subpopulation better suited for automatic classification4,5,9. The objective of this study is to evaluate the predictive performance of doing selective classification based on the predictive uncertainty of the ML model. We seek to answer, can selective classification improve the predictive performance in the early detection of ACS? We observe the answer is yes, and note a 8% increase in sensitivity and a 23% increase in specificity, at the cost of 25% coverage. More concretely, with respect to previous work, our advancements are:

-

1.

Identification of a ML model (i.e. GBDT10) that improves the best reported ACS and NSTE-ACS prediction performance in the prehospital setting. [See Tables 1, 2, 4 and 5]

-

2.

Empirical evidence that selective classification (SC) further boosts sensitivity by 4% and specificity by 10% at the expense of 25% coverage in the prehospital detection of ACS; and 2% sensitivity and 8% specificity for NSTE-ACS. [See Tables 2 and 4]

-

3.

Empirical evidence the that over 20% of the population, the performance of GBDT+SC matches the performance of the traditional HEART risk score without the expensive measurement of troponin. [See Fig. 1]

Results

Patient characteristics and outcomes

Data were collected by Zègre-Hemsey and colleagues11,12. Patients enrolled (n=3646) over 21 years old, transported by ambulance to the ED with non-traumatic chest pain and/or anginal equivalents. Emergency healthcare personnel collected clinical information in the ambulance (i.e. Prehospital setting). The primary outcomes recorded any ACS event (i.e. the acute manifestation of coronary heart disease and include ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina (UA)). The observed prevalence was ACS (20%), STEMI (14%), NSTE-ACS (7%) and unstable angina (3%). These events are within 30 days post ED admission.

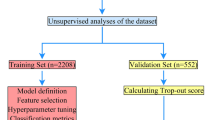

Dataset derivation and preparation

We divide the dataset into two cohorts: An internal cohort (n=1756 cases before 06/2016) for training and validation, and an external cohort (n=1127 cases after 06/2016) for testing. The date was chosen to get a 60%/40% internal/external split. Furthermore, we select 23 covariates (see Table 1) validated in the ACS symptom checklist13,14,15 and available in the prehospital setting16. We discarded patients with a missing initial troponin value (25 total) or without an ECG date; less than 2% of patients had missing covariates imputed with a constant. Constant imputation is a theoretically sound approach to handle missingness17 that generalizes to any site. Nonetheless, we speculate the model’s performance may be negatively impacted if missingness pattern is different between training and evaluation sites. In such a case, there would be distribution shift and this is an open problem in machine learning.

Ensemble of gradient boosted decision trees (GBDT)

GBDT10 was proposed to improve predictive uncertainty estimates in tabular classification tasks. Accordingly, we chose this method because our data is tabular (See Table 1) and we use estimates of predictive uncertainty to filter-out patients unsuitable for automatic classification. Intuitively, this model considers a prediction uncertain if: (1) the input data is out-of-distribution or (2) the data is in-distribution but is ambiguous. The sum of this two sources of uncertainty is equal to the “total uncertainty”18 and is the quantity we use to filter-out patients. From a more formal Bayesian viewpoint, total uncertainty corresponds to the entropy of the posterior predictive distribution \(\mathscr {H}(Y|X,D)\); where X is the test input covariates, Y is the unknown outcome (i.e. \(\{ACS, \lnot ACS\}\)), D is our training split and \(\mathscr {H}(\cdot )\) is the entropy function. In our task, \(\mathscr {H}(Y|X,D)\) will be highest when \(\mathbb {P}(Y=ACS|X,D)\) is 0.5 and decrease monotonically as \(\mathbb {P}(Y=ACS|X,D)\) is closer to 0 or 1. We approximate total uncertainty with a Monte-Carlo sample:

Where \(\{\theta ^{(m)}\}_{m=1}^{M}\) corresponds to an ensemble of M Gradient Boosted Trees (GBT) parametrized by \(\theta ^{(m)}\). Each \(\theta ^{(m)}\) is sampled i.i.d. from an approximate distribution \(q(\theta )\) which converges weakly to a posterior distribution \(p(\theta |D)\) during model training. The likelihood function \(\mathbb {P}(Y|X, \theta ^{(m)})\) corresponds to the output of a modified GBT that guarantees the weak convergence. Please refer to Section 3 from the original paper10 for more details.

Selective classification

Selective classification (SC)7,8 filters-out cases at test time with the goal of improving predictive performance over the filtered-in subpopulation. In this work, our filter rule is “Total uncertainty greater than cutoff value’ (i.e. \(\mathscr {H}(Y|X,D)> \text {cutoff}\)). We use the validation split (\(D_{\text {val}}\)), disjoint from D, to determine a total uncertainty cutoff such that 80% of the cases in \(D_{\text {val}}\) have smaller Total Uncertainty. This corresponds to the 0.8 quantile of \(\{\mathscr {H}(Y|X,D): (X, Y) \in D_{\text {val}}\}\). We deemed 80% the most appropriate coverage to remain clinically useful. However, coverage could be further traded for performance with smaller cutoff values.

Classification performance metrics and estimation

Classification performance is measured in terms of: Coverage, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), accuracy (ACC), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), sensitivity and specificity. These metrics were estimated by 5-fold stratified cross-validation in the internal cohort. More concretely, for each fold: the corresponding training set is used to estimate the model and the selective classification cutoff; the corresponding test set is used to estimate internal cohort performance (Table 3); and the entire external cohort is used to estimate external cohort performance (Table 2). This leads to a total of 5 samples of performance. For each metric, we report the mean (\(\mu\)) and two times the standard error (\(2\sigma\)). For reference, we also reported the prevalence of ACS in the test data, as this affects PPV and NPV.

Classification performance of ACS

The label for this task is either presence or absence of ACS. ACS is the acute manifestation of coronary heart disease and includes ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina (UA). Table 2 compares the ACS predictive performance of GBDT10, GBDT+SC, and the reported performance from alternative methods1,2. GBDT provides better predictive performance as noted by 24% improvement in sensitivity and 13% improvement in specificity. The rest of the metrics follow suit, with only PPV as the exception. The reason for the exception is that PPV can be arbitrarily high due to prevalence. In this case, even though (Takeda)2 discriminator is worse, their higher ACS prevalence masks this in the PPV. With respect to similar prevalence like (Al-Zaiti)1, our PPV is considerably better.

Selective classification (SC) further improves performance (see first row in Table 2) by filtering out uncertain cases (i.e. \(H(Y|X, D)> \text {cutoff}\)). For the filtered-in subpopulation of the external cohort, sensitivity and specificity improve by 4% and 10% points respectively, creating a considerable difference with respect to (Takeda)2 and (Al-Zaiti)1. Table 3 showcases better performance for the internal cohort. This is expected as the model and cutoff are estimated from this cohort. In particular, GBDT improves performance over previous methods by 12% in sensitivity and 8% in specificity. The addition of (SC) further improves the sensitivity and specificity of GBDT by 6% and 8% respectively. Furthermore, the PPV and NPV also increase by 19% and 2% respectively. Nonetheless, coverage decreases by 22% coverage. These results suggests machine learning uncertainty estimates correlate with predictive performance, and that constraining predictions to a subset of patients, may reassure the model’s prediction.

Classification performance of NSTE-ACS

The label for this task is either presence or absence of ACS derived from NSTE-ACS. Like (Al-Zaiti)1, we consider NSTE-ACS as the presence of non-ST elevation MI or unstable angina. Table 4 compares the NSTE-ACS predictive performance of GBDT10 and the reported performance in (Al-Zaiti)1; (Takeda)2 did not report NSTE-ACS performance due to low prevalence (\(3.2\%\)). For reference, we also included the prevalence of NSTE-ACS in the test samples, as this inflates/deflates certain metrics (e.g. PPV and NPV). GBDT improves both sensitivity and specificity by \(14\%\) and \(7\%\) respectively.

Like the ACS task, selective classification further improves performance by reducing coverage to 80%. For this subpopulation of the test set, average sensitivity and average specificity improve by 2% and 8 % points respectively. Furthermore, on average, PPV improves by 14% while NPV stays the same at 99%. These results reinforce the notion that machine learned uncertainty estimates correlate with predictive performance, and that constraining predictions to a subset of patients may reassure us in the model’s prediction. This lead us to only suggest GBDT for this task if prevalence is close to 7%. Note this was not the case for the dataset used in (Al-Zaiti)1 nor the dataset used in (Takeda)2.

Ablations

What impact do input covariates have on performance?

The more covariates we consider, the more performance improves. We ablate the impact that different sources of data have in the classification (See Table 5). Baseline corresponds to age, sex and ECG interpretations; Baseline + Symptoms correponds to all the baseline covariates and the symptoms covariates in Table 1; Baseline + Symptoms + Medical History correponds to all baseline covariates, all symptoms covariates and all medical history covariates in Table 1. As expected, performance increases the more covariates we consider. However, we observe a larger increase in sensitivity when we include Medical History.

Does total uncertainty correlate with performance?

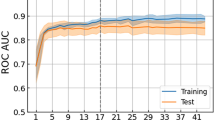

Figure 1, red line with squares, suggest a positive correlation between the average performance of GBDT (y-axis) and the percentage of uncertain samples excluded (x-axis). As expected since excluding uncertain samples should mitigate errors. Furthermore, the AUROC performance of unrelated methods (HEAR and HEART) correlates with the percentage of samples excluded. This assesses whether the excluded samples are deemed uncertain by other predictors. It is surprising that this is the case for both the HEAR and the HEART scores. This is important because we may use GBDT for patient selection and a different method for classification. For instance, the benefit of choosing HEAR and HEART as the classifier is that their prediction is explainable, a valuable feature for healthcare providers. Samples are excluded using the predictive uncertainty estimated from GBDT (Eq. 1). The larger the percentage of uncertain samples excluded, the higher performance we expect.

AUROC performance for three different methods (GBDT, HEAR16, HEART13) as we exclude more uncertain cases. Performance is computed with the non-excluded cases. Uncertainty is the predictive uncertainty from GBDT (Eq. 1). Highlighted is the mean and shaded is two standard deviations from 5-fold cross validation. For this experiment, GBDT uses less covariates than those in Table 1 to match the HEAR16 covariates. Traditional HEART13 requires troponin, in addition to the HEAR covariates. A troponin measurement is generally unavailable in the prehospital setting.

Does GBDT outperform other uncertainty quantification methods on ACS prediction?

We repeated the ACS classification experiment with two other popular approaches for uncertainty quantification (i.e. Deep Ensembles19 and MCDropout20). Results in Table 6 suggest GBDT performs best. Posterior predictive entropy (i.e. H(Y|X, D) or total uncertainty) was used for selective classification across all methods. Note hyperparameter grid search was used for all methods.

Does GBDT outperform traditional scores?

Yes (See Table 7). We measure the predictive performance of GBDT, HEAR16, HEART13, each with and without SC on the task of NSTE-ACS in Fig. 1. HEART ourperforms HEAR because it considers Troponin (a measurement generally unavailable in the prehospital setting). It is important to point that, unlike GBDT, HEAR and HEART are both explainable and thus, on the chance of being correct, may inform decision making further. Since neither HEAR nor HEART consider ST-elevation in their prediction, we evaluate on NSTE-ACS to make a fair comparison with GBDT. To binarize the HEAR and HEART scores, we label intermediate risk cases as high risk. On the other hand, for both HEAR+SC and HEART+SC, we filter out the intermediate risk cases as uncertain. For the task of ACS, previous work21 observes HEART has better discriminative performance than other traditional clinical scores (e.g. GRACE).

Does GBDT outperform other prediction methods?

It depends (See Table 8). If we are interested in rule-out performance (i.e. sensitivity and NPV) the answer is yes. If we are interested in rule-in performance (i.e. specificity and PPV), then XGBoost+SC is superior. Since rule-out performance is more desirable than the rule-in performance, and GBDT is designed for uncertainty quantification, we lean towards GBDT over XGBoost. For the experiments we repeated the ACS classification experiment with XGBoost and its corresponding predictive entropy (i.e. \(\mathscr {H}(Y|X)\)) was used for selective classification. Note hyperparameter grid search was used for all methods.

What are the clinical characteristics of uncertain cases?

The uncertain group showcase older more co-morbid cases than the Non-ACS group, but not as definitive as the ACS group. In Table 9, we measure the count(proportion) of covariates, from the external cohort (n=1127) samples, categorized by GBDT as Non-ACS, Uncertain or ACS. The proportion is w.r.t. the number of samples in the category (i.e. 784, 193 or 150). For example, Hypertension 504(64%) indicates that 504 (or 64%) of the samples in the Non-ACS group had Hypertension; NSTEMI 3(<1%) indicates that 3 (or <1%) of the samples in the Non-ACS group had NSTEMI. We observe symptoms like chest pain are more prominent in ACS, while nonspecific symptoms like palpitations are more frequent in the Non-ACS and Uncertain groups. Prior CAD history, MI, and CABG are average in the Uncertain group (36-55%) but high on the Non-ACS group (54-96%) and small on the Non-ACS group (0-5%). Male patients are more frequent in the ACS group, which reflects previous observations that men have a higher incidence of ACS than women. Older patients are more likely to fall into the Uncertain or ACS categories than the Non-ACS. This aligns with the fact that cardiovascular risk increases with age. ECG changes, particularly ST depression, are much more prevalent in ACS and Uncertain groups. Lastly, the Uncertain group includes a mix of outcomes, most are Non-ACS (92%), but 7% do develop ACS, which supports the need for further evaluation of these cases.

How is performance affected by the coverage threshold?

In general, we observe that accuracy increases and prevalence decreases as we decrease coverage (See Table 10). In the case of NSTE-ACS, the prevalence decreases to the point where sensitivity becomes greatly affected by a single false negative (See the increase in variance and reduction in mean between 80% and 67% coverage). On the other hand, when prevalence is not greatly affected, we observe an improvement across all metrics as we decrease coverage (See ACS section of Table 10). An increase performance as we decrease coverage is consistent with other selective classification work9. Given this is the first work that introduces selective classification for this task, no standard coverage exist and we recommend 80% as a reasonable tradeoff between performance and coverage.

What is the performance of GBDT when we do not consider cases with ST-elevation (STE)?

For this task, we remove any cases with presence of STE from the NSTE-ACS cohort. Additionally, we remove ST-elevation from the list of model covariates. To aid comparison, we also report the performance of the standard NSTE-ACS (i.e. without removing STE cases and including the ST-elevation covariate in the model). Results in Table 11 suggests sensitivity stays the same (at 86%) specificity decreases by 1% (from 83% to 82%). Accordingly, the model would still be advocated, even for the subpopulation that do not present ST-Elevation in the ambulance. The proportion of cases with ST-elevation but without a diagnosis of STEMI is 58%. In the external cohort, this correspond to 13% (n=170) out of (n=1254) total cases. From a clinical perspective this is sensible because ST-elevation is not necessarily associated with STEMI.

Discussion

In this study we measured the ACS and NSTE-ACS classification performance of GBDT and GBDT+SC. Results show that both methods achieve the best sensitivity and specificity reported for the prehospital setting. This is important because any method that furthers is a better candidate to aid the early rule-out or rule-in of ACS. Compared to previously reported results1,2, GBDT10 is a better ML algorithm to rule-out both ACS and NSTE-ACS. Selective classification (SC) further improves both rule-in and rule-out performance of GBDT by, on average, reducing coverage (i.e. percentage of filtered-in test cases) from 100% to 75% (See Table 2). These improvements in performance are particularly important for the task of NSTE-ACS as this represents patients without ST-elevation, a naturally ambiguous class of patients difficult to triage from ECG alone (See Table 4). In regards to standard clinical practice, previous work1 estimates the AUROC of paramedic interpretation to be 67% for ACS and 60% for NSTE-ACS which is more than 20% less than GBDT for the same task. GBDT also outperform standard risk scores (HEAR and HEART) on NSTE-ACS by at least 9% in AUROC (See Table 7). Methodologically, the main difference with respect to previous work is the ML model used for prediction. GBDT10 is designed for predictive uncertainty quantification, whereas previous methods1,2 are designed for predictive accuracy. This difference in design permits more elaborate decision making through the identification of the uncertainty source (See equation 3). Furthermore, we observe GBDT has better rule-out performance than the best previously found predictor2 (See Table 8). In regards to input covariates, previous work2, we consider symptoms, an interpretation of the ECG and age in our prediction of ACS. However, we did not consider vital signs as they are not part of the ACS symptom checklist. We conjecture the addition of vital signs would improve performance like symptoms and history did in Table 5; Unlike other works1, our methodology requires EMS personnel to interpret the ECG and determine the presence/absence of three conditions (See Table 1). However, given how blackbox predictors are prone to random errors22 and overconfidence23, we argue EMS personnel should interpret the patient’s ECG, especially when rule-in and rule-out performance is insufficient. With respect to leveraging uncertainty in cardiovascular disease prediction outside the prehospital setting4,5,6,24,25,26,27, we also observed a positive correlation between selective classification and performance4,5,6,27. However, the deep learning methods19,20 employed among most these studies4,5,24,25 are outperformed by GBDT in this task (See Table 6) and have more complex implementation. Additionally, we reemphasize deep learning models are generally unpredictable under imperceptible or irrelevant changes to the input signal22,28. Even though there have been studies that quantify decreases in performance due to changes in the input (e.g. Modifying the ECG SNR27, ECG distribution shift4,5), no guarantee exists these predictions will not be random or overconfident. Accordingly, as mentioned before, we encourage keeping the clinician in the loop25 until predictive performance is at desired levels3. We emphasize reducing coverage does not imply cases will be missed. Per current clinical guidelines15, uncertain cases should be evaluated further rather than dismissed altogether from care. Additional evaluations may include serial ECG acquisitions, ongoing patient assessment and risk stratification. From an implementation’s perspective, all software is open-source and the model is lightweight (<10 MB) with fast inference (<8 ms per <1 MB sample). Its ACS prediction, uncertainty, and threshold can be displayed on an EMS clinician facing dashboard25. If uncertainty exceeds the threshold, the system alerts the clinician that further assessment may be needed. Ongoing collaboration with EMS clinician partners and prospective evaluations of the model will help inform next steps to this work. An important goal of our work is in being strategic about not adding time/burden to the EMS clinicians. Please see Methods section for further implementation details.

Whilst we showcase performance improvements, the work is still limited by various factors. First, a future prospective study must be done to better ground the performance of any classifier trained retrospectively, especially one that may affect the course of treatment early in the care plan (e.g. GBDT+SC). Second, the current evaluation does not include a completely independent dataset. Though our external validation is large and diverse, we did not use a similar independent dataset at the time of this study. These unique datasets are difficult to obtain as they involve a collaboration between EMS service providers and proprietary institutional data. If GBDT were to be applied to a different site, the model would have to be re-estimated. Third, GBDT+SC prediction remains unexplainable, thus compromising clinical trust and downstream decision making25,29. There exist other explainable predictors that use a subset of our covariates to predict ACS13,16 but either the rule-in and rule-out performance is worse, or require Troponin, a measurement generally unavailable in the prehospital setting (See Fig. 1 and Table 7). In conclusion, GBDT+SC brings ML-based preshopital ACS screening performance closer to the preference of cardiologists3. The improvement in predictive performance outweighs the loss in coverage for this task due to the sensible nature of the prediction. This advocation is stronger if the automatic classification is also intended to aid diagnosis, which requires better rule-in.

Methods

Machine learning model development evaluation

Performance samples are obtained using 5-fold cross validation over the internal cohort to estimate a model and the external cohort to test it. That is, 5 different times, we splits the internal cohort into 20% for internal testing and 80% for training. We further split 10% of the internal training set for validation (\(D_{val}\)), and leave the remaining for training (D). The validation set is used for hyper parameter search and the estimation of the selective classification cutoff. Hyperparameters are selected automatically using the grid_search function to mitigate selection biases (See Table 12 for the grid space). The \(\text {cutoff}\) value is estimated as the 0.8 quantile of the total uncertainty estimates in the validation set. The GBDT method is implemented in the Catboost library, as class CatboostClassifier. Due to small prevalence (i.e. 7% for NSTE-ACS and 20% for ACS), the uncertainty scores will often be smaller for true negatives than for true positives (See Fig. 2). To mitigate this and the overall impact of class imbalance, during training and grid search, samples are weighted inversely proportional to the frequency of its corresponding class (See Fig. 3) (See class_weights) . The class weights are estimated dynamically from the data available for training in each cross-validation fold.

The following metrics are evaluated on the test set: coverage, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), accuracy (ACC), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), sensitivity and specificity. In the case of selective classification, these metrics are evaluated on a subset of the test set. This subset corresponds to the test cases that are smaller than the 0.8 quantile of the total uncertainty in the validation set. This is to guarantee around 80% of the test set is covered. The compromise in coverage was arbitrarily limited to 20%, mainly to preserve utility of automatic classification. Total uncertainty is defined in eq. (1) and is estimated by the average output entropy as in eq. (2). Where the average is across the output of all GBDT in the ensemble.

Study population

The dataset used in this paper was obtained from the Optimizing Electrocardiographic Methods for the Early Identification of ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction in Prehospital Cardiac Care study. The cohort study included patients transported by emergency medical services (EMS) with chest pain and/or anginal equivalent to Carolinas Medical Center (now Atrium) in Charlotte, NC (2013-2017). Per prehospital protocol, EMS providers obtained a standard 12-lead ECG on patients with suspected ACS. Raw digital ECG data were acquired and linked to hospital based clinical outcomes. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and all relevant ethical regulations on human experiments, including the declaration of Helsinki, have been followed. Data were collected through a healthcare registry, and all consecutive eligible patients were enrolled under a waiver of informed consent approved by the institutional review board (#18-3411) of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional data use agreements but are available from Jessica K. Zègre-Hemsey PI (jzhemsey@email.unc.edu) on reasonable request.

Code availability

Code will be made available upon publication Github.

References

Al-Zaiti, S. et al. Machine learning-based prediction of acute coronary syndrome using only the pre-hospital 12-lead electrocardiogram. Nat. Commun. 11, 3966. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17804-2 (2020).

Takeda, M. et al. Prehospital diagnostic algorithm for acute coronary syndrome using machine learning: A prospective observational study. Sci. Rep. 12, 14593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18650-6 (2022).

Cooper, J. G. et al. Performance of a prehospital heart score in patients with possible myocardial infarction: A prospective evaluation. Emerg. Med. J. 40, 474–481. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2022-213003 (2023).

Barandas, M. et al. Evaluation of uncertainty quantification methods in multi-label classification: A case study with automatic diagnosis of electrocardiogram. Infor. Fusion 101, 101978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2023.101978 (2024).

Vranken, J. F. et al. Uncertainty estimation for deep learning-based automated analysis of 12-lead electrocardiograms. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 2, 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztab045 (2021).

Upadhyay, U. et al. Hypuc: Hyperfine uncertainty calibration with gradient-boosted corrections for reliable regression on imbalanced electrocardiograms. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. (2023).

Cordella, L., De Stefano, C., Tortorella, F. & Vento, M. A method for improving classification reliability of multilayer perceptrons. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 6, 1140–1147. https://doi.org/10.1109/72.410358 (1995).

El-Yaniv, R. et al. On the foundations of noise-free selective classification. J. Mach. Learn. Res.11 (2010).

Filos, A. et al. A systematic comparison of Bayesian deep learning robustness in diabetic retinopathy tasks. arXiv:1912.10481 [CS, EESS, STAT] (2019). ArXiv: 1912.10481.

Malinin, A., Prokhorenkova, L. & Ustimenko, A. Uncertainty in gradient boosting via ensembles. arXiv:2006.10562 [CS, STAT] (2021). ArXiv: 2006.10562.

Zègre-Hemsey, J. K. et al. Prehospital ECG with st-depression and t-wave inversion are associated with new onset heart failure in individuals transported by ambulance for suspected acute coronary syndrome. J. Electrocardiol. 69, 23–28 (2021).

Zègre-Hemsey Eugenia, J. K. et al. Patient-reported symptoms of acute coronary syndrome in the prehospital period in a prospective study: Implications for emergency nurse triage diagnosis and clinical outcomes. J. Emerg. Nurs. 51 (6) 1070–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2025.04.016. (2025).

Backus, B. et al. A prospective validation of the heart score for chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int. J. Cardiol. 168, 2153–2158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.255 (2013).

Thygesen, K. et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation 138, e618–e651 (2018).

Rao, S. V. et al. 2025 acc/aha/acep/naemsp/scai guideline for the management of patients with acute coronary syndromes: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (2025).

Stopyra, J. P. et al. Prehospital modified heart score predictive of 30-day adverse cardiac events. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 33, 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X17007154 (2018).

Le Morvan, M., Josse, J., Scornet, E. & Varoquaux, G. What’s a good imputation to predict with missing values? In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 34. (eds Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P. S. & Vaughan, J. W. ) 11530–11540 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2021).

Malinin, A. Uncertainty estimation in deep learning with application to spoken language assessment. Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge (2019).

Fort, S., Hu, H. & Lakshminarayanan, B. Deep ensembles: A loss landscape perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.02757 (2019).

Gal, Y. & Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 1050–1059 (PMLR, 2016).

Al-Zaiti, S. S. et al. Comparison of clinical risk scores for triaging high-risk chest pain patients at the emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 37, 461–467 (2019).

Sato, M., Suzuki, J., Shindo, H. & Matsumoto, Y. Interpretable adversarial perturbation in input embedding space for text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.02917 (2018).

Guo, C., Pleiss, G., Sun, Y. & Weinberger, K. Q. On calibration of modern neural networks. In International conference on machine learning, 1321–1330 (PMLR, 2017).

Aseeri, A. O. Uncertainty-aware deep learning-based cardiac arrhythmias classification model of electrocardiogram signals. Computers 10, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers10060082 (2021).

Elul, Y., Rosenberg, A. A., Schuster, A., Bronstein, A. M. & Yaniv, Y. Meeting the unmet needs of clinicians from AI systems showcased for cardiology with deep-learning-based ECG analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2020620118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2020620118 (2021).

Park, J., Lee, K., Park, N., You, S. C. & Ko, J. Self-attention LSTM-FCN model for arrhythmia classification and uncertainty assessment. Artif. Intell. Med. 142, 102570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2023.102570 (2023).

Jahmunah, V., Ng, E., Tan, R.-S., Oh, S. L. & Acharya, U. R. Uncertainty quantification in densenet model using myocardial infarction ECG signals. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 229, 107308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.107308 (2023).

Hein, M., Andriushchenko, M. & Bitterwolf, J. Why RELU networks yield high-confidence predictions far away from the training data and how to mitigate the problem. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 41–50, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2019.00013 (2019).

Garcıa, J. J., Sarin, N., Kitzmiller, R. R., Krishnamurthy, A. & Zegre-Hemsey, J. K. Risk stratification through class-conditional conformal estimation: A strategy that improves the rule-out performance of mace in the prehospital setting. In Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference (PMLR, 2024).

Acknowledgements

The data used in this study was funded by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (NIH/NINR) through grant K23NR017896 (J.K.Z.-H.) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NCATS) through grant KL2TR002490 (J.K.Z.-H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z.H. provisioned the data. A.K. provisioned the computational resources. J.J.G., R.K. and J.Z.H. analysed the data and reviewed the literature. J.J.G., R.K. and A.K. analysed the methods. J.J.G. conceived the idea, identified the methodology, coded and conducted the experiments, drafted the manuscript. A.K., R.K. and J.Z.H. analysed clinical utility. All authors analysed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garcia, J.J., Kitzmiller, R., Krishnamurthy, A. et al. Selective classification with machine learning uncertainty estimates improves ACS prediction: a retrospective study in the prehospital setting. Sci Rep 16, 913 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24340-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24340-w