Abstract

Rockfall, as a common geological hazard, exhibits extremely complex impact dynamic behaviors that are significantly influenced by factors like the impact falling height and the composition of soil layers. To this end, this paper initially establishes a three-dimensional impact model of falling rock based on the DEM-FDM, which takes into account the near-field impact effect. In this model, the near-field DEM of the soil-rock mixture considers the spatial configuration of rock blocks, while the far-field FDM is employed to analyze the mechanical response of impact. On this basis, numerical analyses are conducted on the impact dynamic response of falling rock and the failure mechanism of soil-rock mixture at different falling heights, followed by series of parametric sensitivity analyses. The results indicate that the impact dynamic response of falling rock and the failure degree of soil-rock mixture increase significantly with the falling height, yet the failure mode remains consistent. The increase in particle stiffness reduces the dynamic amplification factor, exacerbating the failure degree of the model along with the energy dissipation through friction and damping. The increase in particle strength elevates the dynamic amplification factor and mitigates the degree of failure of the model as well as energy dissipation through friction and damping. Moreover, there is a threshold effect for the influence of the proportion of rock block on the dynamic behavior of the soil-rock mixture, but the variation of all three parameters exerts no effect on the failure mode resulting from rockfall impact against the soil-rock mixture. These findings contribute to a better understanding and prediction of the impact-collision of rockfall on soil-rock mixture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rockfall hazards occur when unstable rock blocks detach from slopes, cliffs, or embankments due to factors such as geological structures, climate changes, or human activities. These detached rock blocks generally undergo a process of initiation, acceleration, collision and rebound. Other than rock blocks rolling and sliding in landslides, its movement is mainly predominated by the falling, impacting and rebounding, presenting obvious abruptness and uncertainty. Such kind of movement characteristic easily leads to the different impact-collision and resultant damage of impacted infrastructures, such as rock particle internal failure and microcrack expansion of soil-rock mixtures, as well as exacerbating disaster chains1,2,3. Further, different impact-collision induced by complex shapes, i.e., point impact or face impact, also mean different failure damages, even for two shaped blocks with the same falling height4,5. It is thus crucial to capture the dynamic behavior of falling rock blocks impact soil-rock mixtures, specially incorporating the actual shape of rock blocks6.

Over the past decades, numerous scholars have carried out theoretical, experimental, and numerical studies on the dynamic behavior of soil layers under rockfall impact-collision7,8,9, and proposed various empirical methods to evaluate impact dynamics6,10,11,12. For instance, Chen et al.6 developed a rockfall impact model by utilizing viscoelastic contact theory to quantify the rockfall impact process and introduced a novel time-history solution method for rockfall impact parameters. Tian et al.12 employed deep learning and computer vision techniques to develop a non-contact method for reconstructing the impact force. Prades-Valls et al.10 utilized high-speed cameras to investigate the dynamic parameters of rockfall impact and carried out full-scale field experiments to validate their method. Shen et al.11 performed simulations of three full-scale impact load tests using the finite element method (FEM) and proposed a new method for evaluating the maximum impact load. As a result, the dynamic behavior of soil layers under rockfall impact has been widely investigated13,14,15,16, and it is known that there is an impact domain after the impact process. However, FEM in numerical studies often encounters difficulties in handling large mesh deformation in the impact domain, failing to accurately reflect the deformation and failure caused by the impact. To address this issue, scholars have developed the discrete element method (DEM) to describe the dynamic behavior of rockfall impact and have carried out extensive numerical studies17,18,19. Shen et al.18,(2020) employed the DEM to study the impact response and failure mechanism of different rock shapes and irregular rock block impact surfaces against the soil buffering layer, effectively evaluating dynamic parameters such as impact force and penetration depth. Zhang et al.19 carried out a DEM analysis to study the impact mechanism between falling rock and granular soil, revealing the dynamic response and energy distribution evolution. The results of these studies proved the effectiveness of the DEM in replicating the dynamic response of falling rock impact and the failure mechanism in the impact domain, but DEM exhibits high computational cost, specifically in scenarios simulating large-scale soil-rock mixtures. It requires tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of particle elements when simulating the impact of soil-rock mixtures with a large size, and the calculation time can take weeks or even months, making it difficult to meet the demand for rapid evaluation of multiple working conditions in engineering design, and unable to efficiently characterize the impact of dynamic behavior. It is worth noting that existing numerical studies mainly focus on isotropic pure soil layers, regardless of whether they use FEM or DEM alone or even FEM-DEM coupling methods. These studies also ignore the core microstructure characteristics of soil-rock mixtures, including the random spatial distribution of irregular rock blocks and the heterogeneous particle gradation between rock and soil, which directly affect the impact stress transmission path. In reality, soil layers are typically complex soil-rock mixtures composed of irregularly shaped and sized rock blocks, exhibiting diverse and nonlinear mechanical properties20,21. The mechanical behavior of such soil-rock mixture under impact is more difficult to predict and control22,23. Shen et al.24 found that the dynamic behavior of the soil-rock mixture under rockfall impact differed significantly from the soil layer, but their study simplified the construction of the soil-rock mixture as consisting of regular-shaped rock blocks, ignoring the influence of irregular rock shapes on the mechanical properties of the soil-rock mixture.

To address these issues, this study proposes a DEM-FDM coupling numerical analysis method considering near-field impact effects. This method effectively reduces the computational cost of simulating the rockfall impact process and enables synchronous simulation of particle deformation and failure along with the dynamic response of the rock mass, and it fills the limitations in existing research through two core designs: The near-field uses spherical harmonic functions to reconstruct irregular rock blocks, solving the problem of simplified rock block shapes; The far-field uses FDM instead of full-domain DEM, improving computational efficiency and addressing the limitation of high computational cost of DEM. The established DEM-FDM three-dimensional impact model includes a near-field DEM of soil-rock mixture, which considers the spatial configuration of the rock blocks and uses a three-dimensional rock block reconstruction method to construct a complex soil-rock mixture model with irregularly shaped rock blocks. This method fully accounts for the impact of irregular rock block shapes on the dynamic response and failure mechanism of the soil-rock mixture. The far-field FDM analyzes the dynamic response during the rockfall impact. The combination of these two allows for efficient numerical analysis of the dynamic response and failure mechanism of the soil-rock mixture under rockfall impact.

In this study, we propose the DEM-FDM coupling numerical analysis method to investigate the dynamic behaviors of soil-rock mixture under rockfall impact. The core innovations of this method are: (1) Establishing a near-field/far-field partitioned model—using DEM in the near-field to reconstruct irregular rock blocks and FDM in the far-field to simplify rock mass calculation, balancing computational efficiency and simulation accuracy; (2) Fully considering the influence of irregular rock block shapes on impact response, which fills the limitation of simplified rock block shapes in existing studies. A series of numerical simulations are performed for rockfall impact at different falling heights, focusing on impact dynamics, energy evolution, and failure mechanism of the soil-rock mixture. Moreover, the effects of three parameters, namely particle stiffness, particle strength, and rock block proportion, are considered and discussed. Section "Establishment of a three-dimensional rockfall impact model" briefly introduces the rockfall impact model configuration and DEM-FDM coupling mechanism. Section "Parameter calibration and model verification" presents the particle contact model, region determination, parameter calibration, and model verification to confirm the effectiveness of the DEM-FDM coupled rockfall impact model. Section "Rockfall impact simulation results" provides the results of rockfall impact simulations at different falling heights, including dynamic response, energy evolution, and failure mechanism. Section "Parameter sensitivity analysis" discusses sensitivity analyses of particle stiffness, particle strength, and rock block proportion on the dynamic behaviors of the soil-rock mixture under rockfall impact. Finally, some main conclusions based on the results of the above analysis are provided in Section "Conclusions".

Establishment of a three-dimensional rockfall impact model

Construction of soil-rock mixture

In previous work, we proposed a three-dimensional (3D) modeling method based on spherical harmonic function reconstruction15,16, which accurately reproduced the irregular microscopic shape of 3D rock blocks. This method evolved from the reproduction of individual irregularly shaped rock particles to an improved method for generating rock clusters composed of different non-overlapping rock particles based on spherical harmonic function reconstruction2526,, as shown in Fig. 1. It controls rock block shapes by adjusting the order n of spherical harmonic (SH) functions and the shape coefficient Ψ. Rock block cluster generation involves four sequential stages: size statistics acquires templates with long axis (Lr), middle axis (Ir), and short axis (Sr) from the rock particle contour template library,sphere estimation generates random spheres in the active layer with radius equal to the half-long axis,trial and error checks for sphere overlap, replacing non-overlapping spheres with rock blocks; reproduction completes 3D modeling of multi-sphere, non-overlapping rock clusters via SH reconstruction and iteration.

Development process of three-dimensional irregular rock particle reconstruction25.

The focus of this section lies in expanding the improved irregular rock clusters generation method and applying it to the construction of soil-rock mixture within the DEM-FDM rockfall impact model. It is accomplished by scanning the contours of the irregular rock clusters and integrating them with high-precision spherical harmonic functions to generate multiple rock blocks with irregular shapes and sizes. Subsequently, these irregular rock blocks are combined with soil particles within a specific size range and in a certain quantity. Through the linear contact model incorporated in the DEM, a linear contact bond is formed between them, which accurately restores the mechanical properties of the particles within the soil-rock mixture. Once the internal particle interactions reach equilibrium, a complex soil-rock mixture is formed. The constructed soil-rock mixture is then assembled with the rock mass generated by the FDM to form the DEM-FDM three-dimensional rockfall impact model.

DEM-FDM coupled model configurations

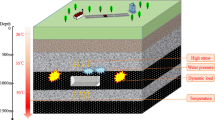

The DEM-FDM coupled model for rockfall impact against the soil-rock mixture is shown in Fig. 2. It can be observed that the model consists of a central soil-rock mixture region and surrounding rock mass. The soil-rock mixture is constrained by four side walls and a bottom wall, with dimensions of 1.6 m in length and width, and 0.4 m in thickness. Before simulating the rockfall impact process, all particles within the soil-rock mixture are subjected to gravity deposition to eradicate all kinetic energy of the particles. Subsequently, a falling rock is positioned directly above the middle of the soil-rock mixture, with an incident angle of 0°. The initial vertical impact velocity \(v_{0}\) of the rockfall impact is determined by the falling height \(h_{f}\) (i.e. \(v_{0} = \sqrt {2gh_{f} }\)). In this study, numerical simulation studies on rockfall impact against soil-rock mixture with falling heights of 1.25, 5, 11.25, and 20 m are carried out. Meanwhile, to monitor the alterations in the mechanical parameters of the soil-rock mixture in the X, Y, and Z directions during the impact process, five measurement circles possessing a radius of 0.19 m are uniformly distributed at intervals of 0.26 m along both the X-axis and Y-axis, centered at a point 0.2 m below the impact surface. The radius of the measurement circles is determined by matching the particle size characteristics of the soil-rock mixture, ensuring each circle encloses a sufficient number of particles to satisfy the statistical validity requirement for mechanical parameter calculation. The interval of 0.26 m is determined based on the stress attenuation law, which enables the complete capture of stress gradient changes in the soil-rock mixture. These measurement circles are used to monitor the mechanical parameters of the soil-rock mixture, specifically for measuring the average normal stress, average displacement, and porosity of particles within each circle, with an optimized sampling frequency to ensure accurate capture of transient dynamic responses during the impact process. Fig. 2(a) shows the shape and position of the central measurement circle (measure 1), and Fig. 2(b) shows the distribution of 10 measurement circles. The five measurement circles along the X-axis are labeled measure 1–5, and the five along the Y-axis are labeled measure 6–10.

Description of DEM-FDM coupling mechanism

In the DEM-FDM coupling analysis, to accurately simulate the interaction between the particles and the continuum elements, it is necessary to handle the transformation between the local coordinate system and the global coordinate system. The local coordinate system takes the center of the particle as the origin, and the Z-axis points along the particle radius towards the contact point. The global coordinate system is consistent with the FDM model. The conversion is achieved through the Euler angle rotation matrix, and the rotation angle is calculated based on the spatial coordinates of the particle center and the contact point. Based on this coordinate conversion mechanism, the boundary force transfer between DEM and FDM domains can realize accurate two-way interaction: first, the contact force between DEM particles is decomposed into normal components and tangential components in the local coordinate system, then converted to the global coordinate system via the Euler angle rotation matrix, and further distributed to the corresponding FDM mesh nodes through the nearest neighbor interpolation method; at the same time, the reaction force calculated by the FDM domain according to its stress-strain relationship is transmitted back to the DEM domain along the same coordinate conversion and node mapping path, ensuring force balance between the two domains. For the verification of iterative steps, a dual convergence criterion is adopted to ensure the stability of coupling calculation: the absolute difference between the force transmitted by DEM and the reaction force calculated by FDM at the interface node must be less than a preset force threshold, and the absolute difference between the particle displacement calculated by DEM and the node displacement calculated by FDM must be less than a preset displacement threshold; if the criteria are not met, the force and displacement values at the coupling interface are updated, and DEM and FDM re-calculate in the same time step until convergence is achieved or the maximum number of iterations is reached, and the rationality of the iterative steps is finally verified by comparing the calculation results before and after convergence. Fig. 3 illustrates the 3D contact geometry between particle and continuum element, where the subscripts C, B, and E represent contact, particle, and element, respectively. When considering the individual contact between a single particle and a continuum element, particle-element contact can be represented by the contact point \(x_{i}^{[C]}\) at the contact surface, and the contact force \(F_{i}^{[C]}\) is composed of the combination of normal contact force \(F_{in}^{[C]}\) and tangential contact force \(F_{{i{\text{s}}}}^{[C]}\). The resultant force and resultant moment on the contacted particle after the transmission of the reaction force of the continuum element as described as follows:

where \(F_{i}^{[B]}\) and \(M_{i}^{[B]}\) represent the resultant force and resultant moment on the contacted particle after superimposing the reaction forces of the continuum element, \(x_{i}^{[C]}\) is the coordinate of the contact point, \(x_{i}^{[B]}\) is the coordinate of the center point of the contacted particle, and \(e\) represents the unit vector.

Three-dimensional contact geometry between particle and continuum element27.

For the continuum element at the contact surface, the contact force at the contact point is distributed to the nodes through area-weighted values, and the total contact force at each node can be expressed as:

where \(F_{i}^{[E]}\) represents the nodal force in the continuum element at the contact surface, and \(K\) is the area weight function, which is calculated through linear interpolation based on the influence area of the contact point. Since the overlap between the particles and the continuum elements is very small, the moment generated by the tangential contact force on the continuum element can be neglected. Based on the equations above, the positions and contact forces between the particles and continuum elements can be updated, enabling data interaction during the DEM-FDM coupling process.

Parameter calibration and model verification

Contact model

In the soil-rock mixture, the irregular rock particles and soil particles can be viewed as a collection of spherical particles. The simulation in this study adopts a linear contact bond model, where contact between two particles forms a bond connection. This model is suitable for discrete media exhibiting particle bonding effects, accurately capturing the interlocking and cohesive characteristics of rock fragments and soil particles in soil-rock mixtures. It effectively simulates both the initial elastic deformation during impact and the subsequent fracture of contact bonds, capabilities that pure friction-based models lack in representing such bonding behavior. Fig. 4 shows the particle-particle and particle-boundary linear contact bond model, representing the normal and tangential interactions between particle-particle and particle-boundary. Stiffness parameters are introduced to describe the relationship between contact force and relative displacement in the linear contact bond model28, as shown in Fig. 5. The force-displacement criteria of this contact model can be expressed as:

where \(k_{n}\) and \(k_{s}\) represent the normal stiffness and tangential stiffness, respectively, \(F_{n}^{c}\) is the normal contact force, \(g_{s}\) is the relative normal displacement between two spherical particles, \(\Delta F_{s}^{c}\) and \(\Delta \delta_{s}\) are the tangential contact force increment and the relative tangential displacement increment, respectively. The values of these are continuously updated with the time step.

When the normal force exceeds the tensile strength, the contact bond breaks, and both normal and tangential forces become zero. If the tangential force exceeds the shear strength, the contact bond breaks, but the contact force is not zero. The elastic limit of the tangential force can be expressed by the following inequality:

where \(\mu\) represents the friction coefficient.

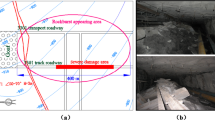

Analysis of key region and first-impact dynamic behaviors

To determine the key analysis region for the dynamic response and failure mechanism during the process of rockfall impact against the soil-rock mixture, a numerical simulation study on the whole process of the rockfall impact was carried out. Taking the falling height \(h_{f}\) = 5 m as an example, an analysis was conducted on the evolution laws of the impact force \(F_{block}\) and the bottom force \(F_{c}\) throughout the whole process of the rockfall impact, as shown in Fig. 6. It can be observed that both \(F_{block}\) and \(F_{c}\) in each impact process show an increasing trend followed by a decrease, The duration of the impact decreases continuously, and as the number of impact increases, the maximum values of \(F_{block}\) and \(F_{c}\) exhibit a nonlinear decreasing trend. The first rockfall impact generates a significantly higher \(F_{block}\) and \(F_{c}\) than subsequent impacts. Fig. 7 illustrates that the maximum values of impact force \(F_{block}\) and bottom force \(F_{c}\) decrease as the number of impacts increases, which corroborates this observation. Fig. 8 shows the evolution of the crack increment distribution in the soil-rock mixture during the whole process of the rockfall impact. It can be observed that after the first rockfall impact, the impact energy is fully applied to the intact particle system, resulting in a significant expansion of the failure range with the largest crack increment. With increasing impact, the rebound kinetic energy of the falling rock decreases, and the subsequent energy is preferentially dissipated by the primary crack network, which is insufficient to generate new cracks. Thus, the increment of cracks and their range in the soil-rock mixture significantly decreases, and the extent of new failure weakens. It should be noted that the cumulative total number of cracks still increases with the number of impacts, but the increment amplitude is much smaller than that of the first impact. From the above, it can be concluded that the rockfall impact mainly contributes to new failure in the first impact, with subsequent impacts showing a gradual weakening of the new dynamic response and failure degree against the soil-rock mixture. Furthermore, comparing the displacement results of the surrounding rock mass formation in the soil-rock mixture after each rockfall impact, it can be seen that the maximum displacement of the rock mass caused by the transmitted impact is no more than 8 mm. This indicates that the rockfall impact mainly affects the near-field soil-rock mixture, with minimal impact transmitted to the far-field rock mass. Therefore, in the following research on rockfall impact at different falling heights, a detailed analysis of the dynamic behaviors in the near-field soil-rock mixture during the first impact process will be conducted.

Parameter calibration

This study mainly focuses on the dynamic response and failure mechanism of the near-field soil-rock mixture subjected to rockfall impact. Therefore, the macroscopic mechanical parameters of the soil-rock mixture are mainly calibrated, with the damping coefficient derived from our previous work, which was iteratively calibrated using the collision restitution coefficient15,16. To obtain the macroscopic mechanical parameters of the soil-rock mixture, triaxial compression simulation tests were conducted using the particle flow program. A cylindrical sample with a diameter of 800 mm and a height of 1200 mm was selected for the simulation, with confining pressures set to 300, 500, and 800 kPa to calibrate the required strength and deformation parameters. The random generation of soil particles with diameters ranging from 0.12 to 0.18 m, rock particles with diameters ranging from 0.3 to 0.45 m, and a rock block proportion of 0.3 were used. The porosity was set at 0.35, and the density of the soil-rock mixture was set at 2600 kg/m3. The loading schematic and the distribution of irregular rock blocks are shown in Fig. 9. Referring to the laboratory triaxial compression test results of the soil-rock mixture29, initial strength parameters (\(F_{n}\),\(F_{s}\) and \(\phi\)) were assigned to the simulated sample, and the strength parameters were iteratively adjusted through repeated triaxial compression simulation tests. After calibration through the triaxial compression simulation test, the resulting stress-strain curve of the soil-rock mixture is shown in Fig. 10. It can be observed that the strength parameters of the simulated soil-rock mixture are consistent with the laboratory test results. The final calibrated physical parameters, strength parameters, and damping coefficient of the soil-rock mixture are shown in Table 1.

Model verification

To verify if the established DEM-FDM model can accurately reflect the dynamic behaviors during the complete rockfall impact process, a numerical simulation study of rockfall impact against the soil-rock mixture under no-damping condition was carried out. By eliminating the effects of damping-induced energy dissipation on velocity and kinetic energy, this condition enables a focused assessment of momentum transfer during impact, thereby facilitating a more direct validation of the accuracy of force transmission within the DEM-FDM coupling model. The simulation results were compared with theoretical results to verify the effectiveness of the DEM-FDM coupling model. A falling rock with a radius of 0.25 m and a mass of 210 kg is released from rest at a height of 1.0 m above the surface of the soil-rock mixture model, undergoing free vertical fall. The study aims to investigate the variation patterns of the rock’s velocity and energy throughout the first impact process. For the soil-rock mixture, all material parameters are adopted from the calibrated values listed in Table 1, except for the damping coefficient, which is set to zero.

Fig. 11 shows the simulation results of the falling rock velocity and kinetic energy during the rockfall impact against the soil-rock mixture model, where the calculation of kinetic energy follows the method proposed in our previous work25. From the velocity variation shown in Fig. 11(a), the complete rockfall impact process can be divided into three phases: free falling, colliding-rebounding, and rebounding-rising. According to the law of conservation of mechanical energy, the instantaneous speed before the impact VN4 \(= \sqrt {2gh} = \sqrt {2 \times 9.8 \times \left( {1 - 0.25} \right)} = 3.83\) m/s. By converting the speed using the theoretical formula, it can be known that the vertical velocity results of the falling rock before impact VN1 - VN4 agree with the simulated values. During the impact, since energy loss is not considered, the vertical velocity after rebounding VN5 is equal to VN4. During the rebounding-rising phase, the theoretical and simulated vertical velocities VN6 - VN8 are consistent. Ignoring the rotational effect, the kinetic energy before the impact \(E_{K4} = {1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}} \right. \kern-0pt} 2}mv^{2} = {1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}} \right. \kern-0pt} 2} \times 210 \times 3.83^{2} = 1.54KJ\). According to the kinetic energy variation shown in Fig.11(b), the comparison between the theoretical and simulated results of kinetic energy EK1 – EK8 shows good agreement as well.

From the qualitative point of view, the DEM-FDM coupled model can reproduce the evolution of velocity and kinetic energy of the impact process. From the quantitative point of view, the DEM-FDM coupled model can also well realize that the simulation results of velocity and kinetic energy are consistent with the theoretical calculation results. Therefore, the above DEM-FDM coupled model can effectively simulate the dynamic behavior of the soil-rock mixture impacted by falling rock.

Rockfall impact simulation results

Dynamic response to rockfall impact

Fig. 12 illustrates the evolution of the impact force \(F_{block}\) acting on the falling rock and the impact-induced bottom force \(F_{c}\) during the first impact process under different falling heights. From Fig. 12(a), it can be seen that when the falling rock collides with the soil-rock mixture, \(F_{block}\) rapidly increases to its peak value and then decreases to zero in a short period, with the duration of the impact being 0.04 s. Both the peak value of \(F_{block}\) and its rate of rise increase progressively with falling height. Specifically, at a falling height of hf = 1.25 m, the peak \(F_{block}\) reaches 117 kN with a rate of rise of 8239 kN/s, whereas at hf = 20 m, the peak increases to 401 kN with a rate of rise of 54410 kN/s. These represent increases by factors of approximately 3.4 and 6.6, respectively, compared to the lower-height condition, indicating a significant intensification of impact energy with greater falling height. Fig.12(b) reveals a noticeable time delay in the response of the \(F_{c}\), which is attributed to the finite propagation time required for the stress wave generated by the impact to travel from the model surface to its base. Upon arrival of the stress wave, \(F_{c}\) rapidly rises to its peak and then gradually decreases to zero as the wave dissipates. With increasing falling height, the peak \(F_{c}\) increases from 157 kN at hf = 1.25 m to 665 kN at hf = 20 m. The dynamic amplification factor, defined as the ratio \(F_{c}\)/\(F_{block}\), increases from 1.34 to 1.66, demonstrating a more pronounced amplification effect under higher impact energy conditions. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to stress wave superposition and the constraint imposed by the fixed base boundary: the incident stress waves reflect at the rigid base, and the constructive interference between incident and reflected waves leads to a transient stress concentration near the base, resulting in a peak \(F_{c}\) that exceeds \(F_{block}\). This amplification is most prominent during the initial stress wave arrival and does not conflict with the overall trend of energy dissipation, which dominates in later stages of wave propagation. Moreover, under high-speed impact conditions, the larger \(F_{block}\) induces noticeable stress oscillations at the base following wave arrival. Consequently, \(F_{c}\) does not return immediately to zero after the primary peak but exhibits minor post-peak fluctuations.

The stress distribution in the soil-rock mixture model reflects the stress wave transmission effect during the rockfall impact process and reveals the stress state across different regions of the model. Fig.13 shows the maximum normal stress \(\sigma_{x}^{\max }\) and \(\sigma_{y}^{\max }\) at different falling heights and its distribution along the X-axis and Y-axis in the middle of the model. It can be observed that as the falling height increases, the peak values of the stress distributions in both the X-axis and Y-axis significantly increase. The peak value occurs at the impact location, and \(\sigma_{x}^{\max }\) and \(\sigma_{y}^{\max }\) gradually decreases as the distance from the impact point increases. When the distance increases to 0.26 m, \(\sigma_{x}^{\max }\) and \(\sigma_{y}^{\max }\) decreases by nearly 85% compared to the peak value. Notably, due to the anisotropy of the soil-rock mixture model, the maximum normal stress \(\sigma_{x}^{\max }\) and \(\sigma_{y}^{\max }\) distribution along the X-axis and Y-axis are asymmetric (see Fig. 13). However, this distribution can be accurately fitted using a Gaussian function, with the specific expression being:

where \(i\) represents the X or Y direction, \(\sigma_{0}\) is the asymptotic line of the fitting function, \(\frac{A}{{w\sqrt {\pi /2} }}\) is the height of the curve, \(x_{c}\) is the central position of the peak value, and \(w\) is the standard deviation. As shown in Fig. 13, the stress distribution along the X-axis and Y-axis for different falling heights during the rockfall impact process is highly consistent with the Gaussian function (R2>0.99). Specifically, the R2 values of the stress distribution curves along both the X-axis and Y-axis at all tested falling heights range from 0.99915 to 0.99968. Meanwhile, the peak height of the Gaussian fitting curve increases significantly with the increase in falling height: it rises from 1.2 MPa at hf = 1.25 m to 3.3 MPa at hf = 20 m (an increase of 175%). This indicates that the Gaussian function can reliably describe the stress distribution caused by rockfall impact at different falling heights, which in turn provides an accurate basis for determining the stress wave transmission characteristics during the impact process.

During the rockfall impact process, the influence of impact force on the soil-rock mixture model is clearly manifested through changes in porosity, which can indirectly reflect stress wave propagation and the post-impact failure behavior of the model. Fig. 14 illustrates the normalized porosity variation along the X-axis of the soil-rock mixture model after impacts at different falling heights, with normalization based on the model’s overall initial porosity. It should be noted that the initial porosity was uniformly distributed throughout the model, as ensured by the four-step preparation procedure described in Section "Construction of soil-rock mixture". Pre-impact measurements using measurement circles confirmed a consistent initial porosity of 0.35±0.01 across the model, with a coefficient of variation below 3%, indicating high uniformity and effectively eliminating any confounding effects of initial porosity heterogeneity on the analysis of impact-induced changes. As shown in Fig. 14, increasing the falling height leads to a significant increase in the amplitude of porosity variation. At hf = 1.25 m, porosity at the impact point first decreases and then increases, with a maximum variation of only 0.04. The porosity changes at Measure 2 and Measure 3 are less than 0.01 and thus negligible. This suggests that under lower falling heights, the rockfall has a smaller initial impact velocity, resulting in a weaker dynamic response and limited stress wave transmission—only particles near the impact zone experience minor compression and rebound, while those in the far-field remain largely undisturbed. In contrast, when hf = 5 m, 11.25 m, and 20 m, the collision induces rapid compression of the soil-rock mixture at the impact point: porosity drops sharply within a short time, and both the magnitude and duration of this compression increase with falling height. This demonstrates that higher falling heights result in greater impact velocities, prolonged contact durations, and more intense stress disturbances during penetration, thereby inducing stronger compression and larger porosity reductions. Notably, after the rockfall detaches from the model, porosity at and around the impact point gradually exceeds the initial value (0.35). This behavior can be attributed to the following mechanism: under high-impact conditions (hf ≥ 5 m), the intense force causes widespread fracturing of inter-particle contact bonds. Consequently, rock fragments and soil particles slide along newly formed fractures, disrupting particle interlocking and leading to localized loosening. This results in a more disordered particle arrangement and enlarged void spaces, ultimately causing porosity to surpass its initial uniform level. Furthermore, as the stress wave propagates to Measure 2 and Measure 3, porosity variations become more pronounced, which aligns with the stress wave patterns observed in Fig. 13 and further supports the role of stress wave propagation in driving spatial porosity changes within the soil-rock mixture.

Energy evolution of rockfall impact

During the process of the rockfall impact, it is often accompanied by the conversion and evolution of energy, including the kinetic energy of the falling rock (Ek), damping dissipation energy (Ed), elastic strain energy of the soil-rock mixture (Es), and particle friction dissipation energy (Ef). Investigating the evolution laws of various energy components during the impact process helps understand the generation and expansion mechanism of cracks in the soil-rock mixture. These energy components are verified by the initial gravitational potential energy \(W_{0}\) to satisfy the following balance condition:

Based on our previous study, the four energy calculation formulas are as follows:

where Nb denotes the number of falling rocks, and Nc is the number of contacts. The variables \(m_{i}\) and \(v_{i}\) denote respectively the inertial mass and translational velocity of falling rock \(i\). \(E_{{{\text{f}}0}}\) represents the initial value at the beginning of the current time step, \(\Delta u_{i}^{{\text{slip }}}\) is the incremental slip tangential displacement of the particle \(i\). \(a_{n}\) and \(a_{s}\) represent the viscous damping coefficients in the normal and tangential directions. \(\frac{{ {\text{dg}}_{s} }}{{ {\text{d}}t}}\) and \(\frac{{ {\text{d}}\delta_{s} }}{{ {\text{d}}t}}\) are the relative normal and tangential velocities at the contact. Fig.15 shows the variations of the four energy components during the impact process. To facilitate observation and analysis, all energy components are normalized by the initial kinetic energy of the falling rock. When the falling rock collides with the soil-rock mixture model, Ek decreases rapidly from 1.0 to near zero within 0.01–0.015 s, while Es increases sharply to its peak value in the same period, accompanied by a gradual increase in Ef and Ed. Quantitatively, at the moment Ek drops to zero, the proportion of Es decreases from 0.78 at hf = 1.25 m to 0.49 at hf = 20 m, while the total proportion of dissipative energy (Ef + Ed) increases from 0.22 to 0.51. This occurs because higher falling heights induce massive fracture of particle contact bonds in the mixture, where tensile and shear bond failures enhance particle sliding and amplify collision-induced velocity attenuation, thus diverting energy from elastic storage to dissipation. During the rebounding process, Es is gradually converted back into Ek, with a small portion dissipating as Ef and Ed. When rebound completes, the final proportions at hf = 1.25 m are Ek = 0.57, Ef = 0.24, and Ed = 0.18, while at hf = 20 m they change to Ek = 0.28, Ef = 0.39, and Ed = 0.28—driven by irreversible crack damage under high-speed impact, which disrupts the particle skeleton and makes it difficult for elastic energy to fully convert back to kinetic energy, while also increasing frictional and damping losses due to broken particle interactions. This energy variation is closely coupled with crack evolution: as falling height increases, tensile and shear cracks increase significantly, with shear cracks dominating energy dissipation by promoting particle sliding, thus confirming that high-speed impacts intensify mixture damage and alter energy patterns.

Rockfall impact failure mechanism

The impact of the falling rock against the soil-rock mixture model induces the formation and propagation of cracks in the model, and the distribution and degree of failure vary under different falling heights. To accurately identify and count cracks, the following criteria were employed: a crack was defined as a continuous region where particle contact bonds were completely fractured, and its range was determined by tracing disconnected particle clusters with inter-particle distances exceeding 0.03 m and no contact force transmission. Fig. 16 and 17 show the crack distribution and crack number evolution after rockfall impact at different falling heights. From Fig. 16, it can be seen that the failure extent of the model and the number of cracks increase as the falling height increases, with both the transverse and longitudinal crack propagation becoming more severe. From Fig. 17, it is evident that during the impact process, both tensile and shear cracks are generated in the soil-rock mixture model, and the number of shear cracks is greater than that of tensile cracks under all falling heights. The total number of cracks increases exponentially with the falling height, rising from 299 to 7596, reflecting the significant enhancement of the failure as the falling height increases. Fig. 18 shows the variation in the failure range and the proportion of tensile and shear cracks for different falling heights. From Fig. 18(a), it can be seen that as the falling height increases, the failure range in the Z-axis gradually expands until it penetrates the bottom, and the failure ranges in the X-axis and Y-axis also increase, which is consistent with the crack distribution shown in Fig. 17. As shown in Fig. 18(b), the cracks generated in the model after the rockfall impact are either tensile or shear cracks, with the number of shear cracks occupying a larger proportion than the tensile cracks. As the falling height increases, the proportion of tensile cracks increases, while the proportion of shear cracks decreases. However, the proportion of shear cracks, on the whole, remains higher than that of tensile cracks, indicating that the failure mechanism is primarily dominated by shear failure, which is also supported by the energy component variations shown in Fig. 15.

41598_2025_24348_Fig16_Print.tif

Parameter sensitivity analysis

In this section, a series of numerical simulations are carried out on the rockfall impact against the soil-rock mixture model, taking the falling rock height \(h_{f}\)= 5 m as an example. The influence of factors such as particle stiffness, particle strength, and rock block proportion on the dynamic response and failure mechanism of the model after impact are studied and discussed. Other basic parameters in the model are consistent with the values given in Table 1.

Effect of particle stiffness

In the previous parameter calibration study, the particle elastic modulus was set to 10 MPa. To further investigate the influence of particle stiffness on the dynamic response and failure mechanism of the model, we consider four other particle stiffnesses, namely 5, 7.5, 15, and 20 MPa of the particle elastic modulus, respectively. To better evaluate the effect of particle stiffness on the dynamic response of rockfall impact, the ratio of the peak value of the bottom force \(F_{c}^{\max }\) to the peak value of the impact force \(F_{block}^{\max }\) is defined as the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\).

Fig. 19(a) shows the variation of the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\) with particle stiffness. It is observed that with a fixed falling height, the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\) decreases rapidly as the particle stiffness increases, and the relationship can be approximated by linear fitting. When the particle stiffness increases from 5 MPa to 20 MPa, the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\) decreases by approximately 39%. Fig. 19(b) presents the changes in energy components with particle stiffness. As particle stiffness increases, the brittleness of the model increases, leading to a greater proportion of friction and damping dissipation, while the proportion of rebound kinetic energy decreases, particularly when the particle stiffness exceeds 15 MPa, where the friction dissipation exceeds the rebound kinetic energy.

In addition, Fig. 19(c) and Fig. 19(d) present the variations in total crack number, failure range, and the proportion of tensile and shear cracks. The total crack number and failure range increase with particle stiffness, with the increase in the Z-axis failure range being more significant than in the X-axis and Y-axis. These trends are also confirmed by the energy component distribution in Fig. 19(b). The proportion of shear cracks remains higher than that of tensile cracks, and the failure mode is dominated by shear failure. In conclusion, increasing particle stiffness results in increased brittleness of the model, causing greater crack number and failure range, while weakening the transmission of impact force and reducing the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\).

Effect of particle strength

Based on the above research, the effect of particle strength on the dynamic response and failure mechanism of the model is further explored. As tensile strength and shear strength are proportionally related, the subsequent discussion focuses on tensile strength, with shear strength varying accordingly. In addition to the particle strength used in the parameter calibration, we consider four other different particle strengths, namely the tensile strengths of 150, 225, 450, and 600 N.

Fig. 20(a) shows the variation of the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\) with particle strength. In contrast to the effect of particle stiffness, the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\) increases linearly with particle strength. When the tensile strength increases from 150 N to 600 N, the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\) increases by about 22%. Fig. 20(b) shows the changes in energy components with particle strength. As particle strength increases, the inter-particle interaction becomes stronger, resulting in reduced friction and damping dissipation, while the rebound kinetic energy significantly increases.

The total number of cracks and the failure range decrease with increasing particle strength, as shown in Fig. 20(c). The total crack number and failure range decrease sharply, with a significant reduction observed. This trend is also confirmed by the energy component distribution. Regarding the failure mode in Fig. 20(d), shear cracks dominate, with their proportion increasing as particle strength increases, while the proportion of tensile cracks decreases. These results indicate that particle strength significantly influences the dynamic response and failure mechanism. As particle strength increases, inter-particle interactions strengthen, improving the transmission of impact force and reducing the failure extent of the model.

Effect of rock block proportion

Real soil-rock mixtures typically consist of varying proportions of rock blocks and soil particles. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the effect of rock block proportion on the dynamic behavior of the rockfall impact to better understand the dynamic response and failure mechanism in practical engineering applications. Based on the previous study, we considered four other different rock block proportions, which are 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4, respectively.

Fig. 21(a) shows the variation of the dynamic amplification coefficient \(\alpha\) under different rock block proportions. It is observed that the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\) initially decreases and then increases with the rock block proportion, and the relationship can be approximated by linear fitting. Fig. 21(b) shows the changes in three energy components with increasing rock block proportion. The kinetic energy of the rockfall first decreases and then increases, while the damping energy and friction dissipation energy initially increase and then decrease. The total number of cracks and the failure range in the X, Y, and Z directions show a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, with the most significant change in the Z-axis failure range, as shown in Fig. 21(c). However, regarding the proportion of tensile and shear cracks in Fig. 21(d), the change in both crack types is minimal with increasing rock block proportion, and the failure mode is unaffected by the rock block proportion. This variation indicates that the effect of rock block proportion on the dynamic response and failure mechanism of the rockfall impact exhibits a threshold effect. When the rock block proportion is near this threshold, the dynamic amplification factor \(\alpha\) is minimized, and the total crack number and failure range are maximized.

Conclusions

Based on DEM-FDM coupled numerical simulations of rockfall impacting a soil-rock mixture, the dynamic response and failure mechanism are investigated under various falling heights and material parameters. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1).

The dynamic response is highly sensitive to falling height. As height increases, the peak impact force \(F_{block}\) and bottom force \(F_{c}\) rise significantly, with \(F_{c}\) exceeding \(F_{block}\) due to dynamic amplification. The maximum normal stress follows a Gaussian distribution, intensifying with falling height. Porosity decreases rapidly upon impact and rebounds above the initial value post-impact, indicating compaction and subsequent cracking. These results emphasize that impact energy, controlled by falling height, is the dominant factor governing dynamic response, which is essential for energy-based hazard evaluation.

-

(2).

The total number of cracks grows exponentially with falling height, and the failure zone expands in all directions. Shear cracks dominate across all cases, confirming a shear-driven failure mechanism. The rise in damping and frictional energy dissipation directly corresponds to increased crack propagation, reinforcing the connection between energy loss and material damage.

-

(3).

Particle stiffness negatively correlates with the dynamic amplification factor, increasing brittleness and energy dissipation. In contrast, particle strength enhances force transmission, raising the amplification factor while reducing damage. Rock block proportion exhibits a threshold effect, with peak damage near a specific value. Among these, particle strength has the strongest influence on dynamic response, followed by stiffness, while rock proportion shows nonlinear behavior. This hierarchy offers practical guidance for material selection in cushion layer design.

Appendix A. Description of 3D rock block reconstruction method

For irregularly shaped 3D rock blocks, if the external contour points are known, spherical harmonics (SH) \(S\left( {\theta ,\phi } \right)\) (\(\theta\) and \(\varphi\) satisfy \(0 \le \theta \le \pi\) and \(0 \le \varphi \le 2\pi\)) can be mapped to spherical coordinates as shown in Fig. 22, as follows:

The Cartesian coordinates \(x\left( {\theta ,\phi } \right)\), \(y\left( {\theta ,\phi } \right)\), \(z\left( {\theta ,\phi } \right)\) of the outer contour points of the rock block can be expressed by spherical harmonic expansion as:

\(a_{n}^{m}\) refers to the undetermined spherical harmonic, and \(Y_{n}^{m} \left( {\theta ,\phi } \right)\) refers to the spherical harmonic given by:

where n and m represent the degree and order of \(P_{n}^{m} \left( x \right)\) respectively, and the specific expression of \(P_{n}^{m} \left( x \right)\) is as follows:

\(p_{n} \left( x \right)\) is a Legendre polynomial of order n defined by Rodrigues’ formula:

Based on the known surface points of the rock block and the corresponding spherical harmonic values, Eq. (14) can be extended to a matrix form:

The number of known surface points of the actual rock block is large enough to realize the solution of all coefficients \(a\), to complete the 3D reconstruction of the irregular rock block. At the same time, the volume and surface area of the reconstructed irregular 3D rock block are calculated as follows:

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author (2301100@stu.neu.edu.cn) on reasonable request.

References

Ferrari, F., Giani, G. P. & Apuani, T. Towards the comprehension of rockfall motion, with the aid of in situ tests. Italian J. Eng. Geol. Environ. 6, 163–171 (2013).

Valagussa, A., Frattini, P. & Crosta, G. B. Earthquake-induced rockfall hazard zoning. Eng. Geol. 182, 213–225 (2014).

Volkwein, A. et al. Rockfall characterisation and structural protection – a review. Nat. Hazard. Earth Syst. Sci. 11(9), 2617–2651 (2011).

Agliardi, F. & Crosta, G. B. High resolution three-dimensional numerical modelling of rockfalls. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 40(4), 455–471 (2003).

Asteriou, P. & Tsiambaos, G. Empirical model for predicting rockfall trajectory direction. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49(3), 927–941 (2016).

Chen, T., Zhang, G. & Xiang, X. Research on rockfall impact process based on viscoelastic contact theory. Int. J. Impact Eng. 173, 104431 (2023).

Huang, G. et al. A novel bond model based on three-dimensional sphere discontinuous deformation analysis for simulating rockfall-flexible passive net interactions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 174, 105664 (2024).

Ye, S., Chen, H. & Tang, H. The calculation method for the impact force of the rockfall. Acad. Railway Sci. 31, 56–62 (2010).

Zhong, H., Lyu, L., Yu, Z. & Liu, C. Study on mechanical behavior of rockfall impacts on a shed slab based on experiment and SPH–FEM coupled method. Structures 33, 1283–1298 (2021).

Prades-Valls, A., Corominas, J., Lantada, N., Matas, G. & Núñez-Andrés, M. A. Capturing rockfall kinematic and fragmentation parameters using high-speed camera system. Eng. Geol. 302, 106629 (2022).

Shen, et al. Full-scale testing and modeling of rock-shed shock absorbers under impact loads. Int. J. prot. Struct. 9(2), 157–173 (2018).

Tian, Y., Luo, L., Yu, Z., Xu, H. & Ni, F. Noncontact vision-based impact force reconstruction and spatial-temporal deflection tracking of a flexible barrier system under rockfall impact. Comput. Geotech. 153, 105070 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. Field experimental verifications of 3D DDA and its applications to kinematic evolutions of rockfalls. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 175, 105687 (2024).

Wang, H., Guo, C., Wang, F., Ni, P. & Sun, W. Peridynamics simulation of structural damage characteristics in rock sheds under rockfall impact. Comput. Geotech. 143, 104625 (2022).

Zhang, S.-L., Yang, X.-G. & Zhou, J.-W. A theoretical model for the estimation of maximum impact force from a rockfall based on contact theory. J. Mount. Sci. 15(2), 430–443 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Liu, Z., Shi, C. & Shao, J. Three-dimensional reconstruction of block shape irregularity and its effects on block impacts using an energy-based approach. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 51(4), 1173–1191 (2018).

Shen, W., Zhao, T., Dai, F., Crosta, G. B. & Wei, H. Discrete element analyses of a realistic-shaped rock block impacting against a soil buffering layer. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53(8), 3807–3822 (2020).

Shen, W., Zhao, T., Dai, F., Jiang, M. & Zhou, G. G. D. DEM analyses of rock block shape effect on the response of rockfall impact against a soil buffering layer. Eng. Geol. 249, 60–70 (2019).

Zhang, L., Lambert, S. & Nicot, F. Discrete dynamic modelling of the mechanical behaviour of a granular soil. Int. J. Impact Eng. 103, 76–89 (2017).

Qian, J. et al. A thermodynamically consistent constitutive model for soil-rock mixtures: A focus on initial fine content and particle crushing. Comput. Geotech. 169, 106233 (2024).

Zhong, G., Zhang, X., Wu, S., Wu, H. & Song, X. Study on meso-mechanical properties and failure mechanism of soil-rock mixture based on SPH model. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 162, 375–392 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Failure analysis of soil-rock mixture slopes using coupled MPM-DEM method. Comput. Geotech. 169, 106226 (2024).

Wu, W., Yang, Y. & Zheng, H. Hydro-mechanical simulation of the saturated and semi-saturated porous soil–rock mixtures using the numerical manifold method. Comput. Method. Appl. Mech. Eng. 370, 113238 (2020).

Shen, W., Zhao, T. & Dai, F. Influence of particle size on the buffering efficiency of soil cushion layer against rockfall impact. Nat. Hazard. 108(2), 1469–1488 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Shao, J., Liu, Z. & Shi, C. Numerical study on the dynamic behavior of rock avalanche: Influence of cluster shape, size and gradation. Acta Geotech. 18(1), 299–318 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Numerical and experimental studies on the motion and deposition of collapsing rock clusters: Effect of rock particle sphericity. Powder Technol. 447, 120213 (2024).

Chen, W.-B., Xu, T. & Zhou, W.-H. Microanalysis of smooth Geomembrane-Sand interface using FDM–DEM coupling simulation. Geotext. Geomembr. 49(1), 276–288 (2021).

Potyondy, D. O. & Cundall, P. A. A bonded-particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41(8), 1329–1364 (2004).

Zhang, Q. et al. Discrete element simulation of large-scale triaxial tests on soil-rock mixtures based on flexible loading of confining pressure. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 41(8), 1545–1554 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study has been jointly supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant 2023YFC2907303) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12372374).

Funding

This study was jointly funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant 2023YFC2907303) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12372374).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yulong Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Qiwen Guo: Project administration, Writing – original draft, review & editing. Haixia Zhang: Investigation, Review, Software. Yuhan Wang: Supervision. Xin Wang: Visualization. Xin Zhang: Data curation, Formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Guo, Q., Zhang, H. et al. Numerical analysis of dynamic behavior of falling rock block impact against soil-rock mixture by coupling DEM-FDM approach. Sci Rep 15, 40465 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24348-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24348-2