Abstract

This paper proposes a novel distributed fixed-time adaptive control scheme for cooperative tracking of quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) formations under communication-constrained conditions. Unlike traditional methods that rely on global information or asymptotic convergence, the proposed approach guarantees fixed-time convergence of both state estimation and control within a predefined time bound. First, a distributed fixed-time observer is designed to reconstruct the virtual leader’s position and velocity using only local information. Based on this, a fuzzy adaptive nonsingular terminal sliding mode controller is developed to ensure robust fixed-time convergence of the position tracking. Furthermore, a computationally efficient indirect fuzzy identification mechanism is introduced, which requires only a single adaptive parameter to estimate the upper bound of the lumped uncertainties, thereby significantly reducing the online computational burden. Simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness, fast convergence, and robustness of the proposed method, highlighting its potential for UAV formation control in communication-constrained environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have drawn significant attention in recent decades, for their numerous applications, such as delivery services1, pesticide spraying2, forest fire monitoring3, border patrol4, and geological exploration5. In recent years, quadrotor UAVs have gained significant attention due to their lightweight, compact size, simple structure, and agile control capabilities. However, the individual capabilities of a single UAV are limited, making it unable to handle increasingly complex and diverse tasks. Consequently, the design of UAV formation systems for complementary capabilities and coordinated operations has become an urgent demand. The objective of UAV formation is to explore collaborative control strategies that enable the quadrotor UAV cluster to fly along specified trajectories and form predetermined formations within a certain timeframe through inter-vehicle communication within the system6.

Currently, there are several methods for UAV formation, including leader-follower7, behavior-based8, artificial potential field method9, and virtual structure approaches10. However, there are some shortcomings in the aforementioned results11,12. In recent years, graph theory-based methods have emerged as effective control strategies, where the information of the virtual leader UAV only influences its adjacent quadrotor UAVs. The general formation control system structures are mainly classified into three categories: centralized control13, decentralized control14, and distributed control15. Centralized control relies heavily on the leader, while decentralized control struggles to achieve global optimal control. Distributed control, on the other hand, aims to devise distributed algorithms to reach cooperative control for quadrotor UAVs through local interaction information. This approach requires lower communication bandwidth and has advantages such as high robustness and adaptability. Distributed control is primarily implemented through two frameworks. The first framework is based on local synchronization errors, which define local position and velocity synchronization errors using the state information of neighboring UAVs16. The other framework is based on distributed observers17, in which a state observer is designed to approximate the state of the virtual leader. In the process of controller design of multi-agent formation, to ensure that the system can quickly reach formation and accurately track according to the given trajectory, adaptive control18, sliding mode control19, and backstep method20 are often used to design the controller. When using the sliding mode control method to design the controller, the system can converge to the equilibrium point along the sliding mode surface through reasonable design, to achieve a good control effect. However, how to make the sliding mode surface reach the equilibrium point rapidly plays a critical role in the control performance of quadrotors.

Recently, the finite-time control method has emerged, aimed at improving convergence speed21,22. This method establishes an upper bound on the time required to stabilize the system based on its initial state values, and has been widely applied in quadrotor systems23,24. For example, in25, a novel fixed-time adaptive sliding mode control strategy is developed for saturated quadrotor attitude systems, achieving initial-condition-independent convergence within a prescribed time. In26, a novel safety control strategy employing fixed-time observers is developed for quadrotor UAVs operating under multiple actuator faults and unknown disturbances. The synergistic combination of a fixed-time sliding mode observer and integral sliding mode controller demonstrates remarkable robustness enhancement against complex fault conditions. In27, a novel fixed-time disturbance observer-based control framework is developed for quadrotor UAVs operating under multiple uncertainties and external disturbances, featuring rapid disturbance rejection and fault compensation capabilities with guaranteed fixed-time stability. Although the effectiveness of finite-time control strategies has been thoroughly validated in single quadrotor systems, their efficacy in distributed cooperative control of multiple quadrotors remains an open research question that has attracted growing attention from scholars.

To address this issue, several recent studies have focused on extending finite-time control strategies to multi-UAV cooperative scenarios. In28, a distributed leader-follower formation control scheme was proposed for multiple quadrotors to achieve finite-time formation control. In29, the finite-time cooperative control challenge for disturbance-affected quadrotor formations was effectively resolved through the development of a novel finite-time observer and corresponding robust cooperative controller based on the designed state observer. In30, the authors proposed a practical finite-time cooperative control scheme for UAV formations, introducing an event-triggered finite-time disturbance observer for effective disturbance rejection. Additionally, in31, an adaptive finite-time neural control scheme was achieved for constrained nonlinear systems via an innovatively designed barrier Lyapunov function. Note that the finite-time control approach enhances convergence rates, however, the settling time hinges on initial values.

To handle this issue, the fixed-time control method has been devised32,33, ensuring the convergence time is unaffected by initial conditions, depending solely on design parameters. For instance, in34, a singularity-free distributed formation tracking control scheme was developed, guaranteeing bounded formation errors with fixed-time convergence. In35, a novel distributed fixed-time cooperative control framework was introduced, employing an innovative non-singular terminal sliding surface design. In36, a novel distributed collaboration fixed-time control protoco was proposed to stabilize the geometric spatial shape of multiple quadrotors, where uniform stabilization within a fixed time can be ensured. Furthermore, the chattering issue in conventional linear sliding mode control is notably reduced.

This study further explores distributed fixed-time cooperative control for multiple quadrotor UAVs utilizing local communications, building upon the preceding discussion. The contributions are as follows.

-

1.

Unlike the finite-time convergence control methodologies presented in28,29,30, this study delves into the design of a novel distributed fixed-time observer, empowering it to precisely estimate the virtual leader’s position and velocity information within a fixed time horizon.

-

2.

Compared to the literature29,30, leveraging the recovered state information, a tailored fuzzy adaptive nonsingular terminal sliding mode controller is devised for each quadrotor UAV. This controller guarantees the achievement of local position tracking within a fixed time period, enhancing the swarm’s cooperative tracking capabilities. The convergence time does not depend on the initial value, but only on the design parameters

-

3.

Different from33,42, an efficient indirect fuzzy identification mechanism is adopted, which incorporates a fuzzy logic system to estimate the upper bound of the lumped uncertainty. This approach simplifies the identification process by requiring only a single adaptive parameter for each estimation, thereby reducing computational overhead.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. "Preliminaries" introduces the proposal of the problem, graph theory and supporting lemmas, while Sect. "Main results" designs a novel distributed fixed-time observer and a tailored fuzzy adaptive nonsingular terminal sliding mode controller for each quadrotor UAV. After that, simulation results are given in Sect. "Simulation results", and conclusions are finally drawn in Sect. "Conclusion".

Preliminaries

Notations

\({\mathbb{R}}^{n}\) and \({\mathbb{R}}^{m \times n}\) denote a \(n \times 1\) vector and a \(m \times n\) matrix, In and 0n denote an identify \(n \times n\) matrix and a \(n \times 1\) vector with all elements 0, the 1-norm and the 2-norm of a vector are denoted by \(\left\| \cdot \right\|_{1}\) and \(\left\| \cdot \right\|\). \(\otimes\) represents the Kronecker product, and \(\lambda_{\min } (C)\) represents the smallest eigenvalue of matrix C. For \(\varsigma \in {\mathbb{R}}^{n}\) and \(p > 0\), \({\text{sig}}^{p} ( \cdot )\) and \({\text{sgn}} ( \cdot )\) are denoted by \({\text{sig}}^{p} (\varsigma ) = \left[ {|\varsigma_{1} |^{p} {\text{sgn}} (\varsigma_{1} ), \ldots ,|\varsigma_{n} |^{p} {\text{sgn}} (\varsigma_{n} )} \right]^{T}\) and \({\text{sgn}} (\varsigma ) = \left[ {{\text{sgn}} (\varsigma_{1} ), \ldots ,{\text{sgn}} (\varsigma_{n} )} \right]^{T}.\)

Problem statement

The quadrotor UAV cluster, comprising a virtual pilot and multiple quadrotor UAVs, is represented as

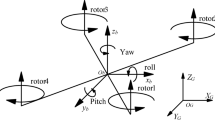

Figure 1 illustrates the configuration of the quadrotor UAV, consisting of a rigid body structure with four rotors arranged in a cross shape. This setup denotes a typically encountered underactuated system, characterized by six degrees of freedom and four control inputs. The dynamics governing its position and attitude are expressed as follows

Position dynamics:

Attitude dynamics:

where \(i = 1, \cdots ,N\), \(P_{i} = \left( {P_{x,i} ,P_{y,i} ,P_{z,i} } \right) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{3}\) and \(V = \left( {V_{x,i} ,V_{x,i} ,V_{x,i} } \right)^{T} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{3}\) represent the position and velocity of the mass center, while \(\Theta_{i} = \left( {\phi_{i} ,\theta_{i} ,\psi_{i} } \right)^{T} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{3}\) and \({{\varvec{\Omega}}}_{i} = \left( {p_{i} ,q_{i} ,r_{i} } \right)^{T} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{3}\) denote the Euler angles and angular velocity. \({\varvec{J}}_{i} = diag\left\{ {J_{x,i} ,J_{y,i} ,J_{z,i} } \right\} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{3 \times 3}\) stands for the inertia matrix, and \({\varvec{G}}_{a,i} = \sum\limits_{l = 1}^{4} {{\varvec{J}}_{r,i} } \left( {{{\varvec{\Omega}}}_{i} \times {\varvec{e}}_{3} } \right)( - 1)^{l + 1} \omega_{l,i}\) signifies the torque produced by the motor rotation. \({\varvec{d}}_{p,i}\) and \({\varvec{d}}_{a,i}\) represent the external disturbances, while \(m_{i}\) and g denote the total mass and gravitational acceleration. \({\varvec{e}}_{3} = (0,0,1)^{T}\) indicates the unit vector along the vertical direction. \({\varvec{u}}_{T,i}\) and \(\tau_{i}\) symbolize the lifting force and rotating torque, i.e.,

where \(f_{1,i}\) and \(\omega_{l,i}\) denote the lift force and speed of each rotor. \(L_{i}\) signifies the distance separating the motor from the mass center. \(\kappa_{i}\) and \(k_{i}\) are aerodynamic coefficients, respectively. \({\mathbf{R}}_{i} \left( {{{\varvec{\Theta}}}_{i} } \right)\) and \(\Pi_{i} \left( {{{\varvec{\Theta}}}_{i} } \right)\) represent the rotation matrix and attitude motion matrix, i.e.,

Graph theory

Consider a directed graph \({\mathcal{G}} = \left\{ {{\mathcal{V}},{\mathcal{E}}} \right\}\) with nodes set represented by \({\mathcal{V}} = \{ 1,...,n\}\) and edges set represented by \({\mathcal{E}} \subseteq {\mathcal{V}} \times {\mathcal{V}}\). Let’s denote the adjacency matrix as \({\mathcal{A}} = \left[ {g_{ij} } \right] \in {\mathbb{R}}^{n \times n}\), where \(g_{ij} { = 1}\) when \((i,j) \in {\mathcal{E}}\) and \(g_{ij} { = 0}\) otherwise. Let’s denote the Laplacian matrix as \({\mathcal{L}} = \left[ {L_{ij} } \right] \in {\mathbb{R}}^{n \times n}\) where \(L_{ii} = \sum\limits_{j = 1,j \ne i}^{n} {g_{ij} }\) and \(L_{ij} = - g_{ij}\) when \(i \ne j\). Define a virtual leader labeled by agent 0 with the position and attitude equal to the desired values. For the quadcopter UAV cluster with a virtual leader and \(n\) followers, then \({\mathcal{L}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} 0 & {0_{n}^{{\text{T}}} } \\ {{\mathcal{L}}_{2} } & {{\mathcal{L}}_{1} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\) denotes the Laplacian matrix where \({\mathcal{L}}_{1}\) represents the interconnections among the followers while \({\mathcal{L}}_{2}\) signifies the interconnections between the virtual leader and the followers. If a node without neighbors can reach other nodes by any path, the graph is considered to possess a directed spanning tree.

Assumption 1.

\({\mathcal{G}}\) has a directed spanning tree.

Assumption 2.

The virtual leader’s acceleration \(\ddot{p}_{0}\) is bounded, that is, \(\left\| {\ddot{p}_{0} } \right\| \le \overline{a}\) with \(\overline{a} > 0\).

Lemma 1.

37 For matrix \(- {\mathcal{L}}_{1}^{ - 1} {\mathcal{L}}_{2}\), each element is non-negative, and the sum of each row equals 1.

Supporting lemmas

In this section, we will establish the following lemmas, which play an important role in the subsequent stability analysis.

Lemma 2.

38 For a system

when there’s a \(V(\chi )\) such that

with \(\kappa_{1} > 0\), \(\kappa_{2} > 0\), \(0 < \alpha < 1\), and \(\beta > 1\), system (3) is considered to be globally fixed time stable with \(V\left( \chi \right)\) converging to zero in a fixed time \(T_{c} \le \frac{1}{{\kappa_{{1}} \left( {1 - \alpha } \right)}} + \frac{1}{{\kappa_{{2}} \left( {\beta - 1} \right)}}.\)

Lemma 3.

39 For system (3), when there’s a \(V\left( \chi \right)\) such that

with \(\kappa_{1} > 0\), \(\kappa_{2} > 0\), \(0 < \alpha < 1\), \(\beta > 1\), and \(\vartheta > 0\), system (3) is considered to be practically fixed-time stable. \(V\left( \chi \right)\) can stabilize towards the region of zero, i.e.,

with \(0 < \varepsilon < 1\) in a bounded convergence time \(T_{c} \le \frac{1}{{\kappa_{{1}} \varepsilon \left( {1 - \alpha } \right)}} + \frac{1}{{\kappa_{2} \varepsilon \left( {\beta - 1} \right)}}\).

Lemma 4.

40 \(\hbar ( \cdot )\) is a continuous function defined over the compact set \(\Gamma \subset {\mathbb{R}}^{n}\). Using the fuzzy logic system, there holds

with \(W^{ * } = \left[ {w_{1}^{ * } , \ldots ,w_{N}^{ * } } \right]^{T} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{N}\) denoting the ideal weight and \(\Psi \left( {\rm K} \right) = \frac{{\left[ {\Psi_{1} \left( {\rm K} \right), \ldots ,\Psi_{N} \left( {\rm K} \right)} \right]^{T} }}{{\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{N} {\Psi_{i} \left( {\rm K} \right)} }} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{N}\) signifying the basis function. \(\varsigma\) denotes the approximation error, while \(N\) indicates the number of rules. \(\Psi_{i} \left( {\rm K} \right)\) generally refers to the Gaussian function

where \(i = 1,2, \ldots ,N\), \(c_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{n}\) and \(w_{i}\) are the center and width.

Lemma 5.

41 For \(x_{1} \in {\mathbb{R}}\), \(x_{2} \in {\mathbb{R}}\), \(\alpha > 0\), \(\beta > 0\), and \(\rho > 0\), there holds

Lemma 6.

42 For \(X_{1} \in {\mathbb{R}}\), \(X_{2} \in {\mathbb{R}}\), \(X_{1} \le X_{2}\), and \(\beta > 1\), there holds

Lemma 7.

41 For \(x_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}\), \(0 < \alpha \le 1\), and \(\beta > 1\), there holds

Lemma 8.

43 For the following systems

where \({\text{sig}}^{\mu } (y) = |y|^{\mu } \cdot {\text{sgn}} (y)\), \({\text{sig}}^{\nu } (y) = |y|^{\nu } \cdot {\text{sgn}} (y)\), \(l_{1} > 0\), \(l_{2} > 0\), \(\mu > 1\), and \(0 < \nu < 1\). System (12) is stable at a fixed time, and the stable time \(T_{s}\) is bounded by:

Main results

In this section, a novel distributed fixed-time observer is designed in 3.1. In 3.2, a tailored fuzzy adaptive nonsingular terminal sliding mode controller is designed for each quadrotor UAV. The indirect fuzzy identification mechanism is adopted in which the aggregated uncertain term is determined by using the fuzzy logic system, in which each identification only requires one adaptive parameter, and the computational cost is reduced. The proposed distributed control framework is shown in Fig. 2.

Distributed fixed-time state observer

A novel distributed fixed-time state observer is devised for each follower UAV to accurately determine the virtual leader’s position and velocity. \({{\varvec{\upxi}}}_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{3}\) and \({{\varvec{\upzeta}}}_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{3}\) represent the position and velocity estimates of the virtual leader. Define \({{\varvec{\upxi}}}_{0} = {\mathbf{p}}_{0}\) and \({{\varvec{\upzeta}}}_{0} = {\mathbf{v}}_{0}\). Design the distributed fixed-time state observer as follows

with \(l_{1} > 0\), \(l_{2} > 0\), \(0 < \mu < 1\), \(\nu > 1\), and \(b \ge \overline{a}\) being observer parameters that play a crucial role in determining the observer’s performance.

Theorem 1:

For the quadrotor-UAV cluster (1), under the designed distributed fixed-time observer, the virtual leader’s position and velocity can be approximated within a fixed time for each follower UAV.

Proof:

Define the error \({\tilde{\mathbf{\xi }}}_{i} = {{\varvec{\upxi}}}_{i} - {\mathbf{p}}_{0} - {{\varvec{\upchi}}}_{i}\), \({\tilde{\mathbf{\zeta }}}_{i} = {{\varvec{\upzeta}}}_{i} - {\mathbf{v}}_{0}\). Let \({\tilde{\mathbf{\xi }}} = \left[ {{\tilde{\mathbf{\xi }}}_{1}^{{\text{T}}} , \ldots ,{\tilde{\mathbf{\xi }}}_{n}^{{\text{T}}} } \right]^{{\text{T}}}\),\({\tilde{\mathbf{\zeta }}} = \left[ {{\tilde{\mathbf{\zeta }}}_{1}^{{\text{T}}} , \ldots ,{\tilde{\mathbf{\zeta }}}_{n}^{{\text{T}}} } \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \({{\varvec{\Lambda}}}_{0} = \left[ {{{\varvec{\upeta}}}_{0}^{{\text{T}}} , \ldots ,{{\varvec{\upeta}}}_{0}^{{\text{T}}} } \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), and \({\mathbf{H}} = \mathcal{L}_{1} \otimes {\mathbf{I}}_{3}\).

We select the Lyapunov function

Employing Lemmas 1 and 7, we can arrive at

where \(\kappa_{1} = \frac{{2^{{\frac{1 + \mu }{2}}} l_{1} }}{{\lambda_{\min }^{{\frac{1 + \mu }{2}}} \left( {\mathbf{H}} \right)}}\) and \(\kappa_{2} = \frac{{2^{{\frac{1 + \nu }{2}}} \left( {3n} \right)^{{\frac{1 - \nu }{2}}} l_{2} }}{{\lambda_{\min }^{{\frac{1 + \nu }{2}}} \left( {\mathbf{H}} \right)}}\). By using Lemma 2, it can be observed that the convergence can be achieved in the fixed time \(T_{c1} \le \frac{2}{{\kappa_{{1}} \left( {1 - \mu } \right)}} + \frac{2}{{\kappa_{{2}} \left( {\nu - 1} \right)}}\), and hence \({\tilde{\mathbf{\zeta }}}_{i}\) also converges to zero within \(T_{c1}\).

When \(t \ge T_{c1}\), \({{\varvec{\upzeta}}}_{i} = {\mathbf{v}}_{0}\) can be obtained. Select the Lyapunov function

Employing Lemma 7, we can arrive at

By using Lemma 2, one deduces that \(U_{2}\) converges to zero within the fixed time \(T_{c1}\). Consequently, \({\tilde{\mathbf{\xi }}}_{i}\) also converges to zero within \(T_{c1}\). The analysis presented above shows that the leader’s position and velocity can be approximated within a fixed time \(T_{c1}\). This concludes the proof of Theorem 1.

Remark 1.

Unlike the finite-time convergence control methodologies presented in28,29,30, which depend on the initial conditions, a distributed fixed-time state observer was designed for each follower UAV to estimate the status information of the virtual leader. This status information can be used for subsequent controller development.

Fixed-time adaptive local controller design

This section endeavors to devise the fixed-time adaptive controller to realize cooperative control by utilizing the designed observer. Define the error variables

When \(t \ge T_{c1}\), by Theorem 1, we can obtain that \({{\varvec{\upxi}}}_{i} = {\mathbf{p}}_{0} + {{\varvec{\upchi}}}_{i}\) and \({{\varvec{\upzeta}}}_{i} = {\mathbf{v}}_{0}\). Meanwhile, the error variables are equal to the position and velocity synchronization errors. Introduce the following fixed-time terminal sliding mold surface

with \(r_{1} > 0\) and \(r_{2} > 0\).

Lemma 9.

Considering the fixed-time terminal sliding mold surface (20), when \(s = 0\), the tracking errors \({\mathbf{e}}_{1i}\) and \({\mathbf{e}}_{2i}\) are stable at a fixed time.

Proof:

When \(s = 0\), (20) is rewritten as

and

where \({\text{r}}_{1} { > 0}\), \(r_{2} { > 0}\), \(\mu { > 0}\) and \(0 < \nu < 1\).

We design the Lyapunov function

Using (22), we can further get

where \(\kappa_{3} = r_{1} 3^{{\frac{1 - \mu }{2}}} 2^{{\frac{1 + \nu }{2}}}\) and \(\kappa_{4} = r_{2} 2^{{\frac{1 + \nu }{2}}}\).

According to Lemma 8, \(e_{1i}\) and \(e_{2i}\)

This concludes the proof for Lemma 9.

Deriving the derivative of \({\mathbf{s}}_{i}\) produces

with \({{\varvec{\Xi}}}_{1i} = {\text{diag}}\left\{ {\left| {e_{1i,1} } \right|^{\mu - 1} ,\left| {e_{1i,2} } \right|^{\mu - 1} ,\left| {e_{1i,3} } \right|^{\mu - 1} } \right\}\), \({{\varvec{\Xi}}}_{2i} = {\text{diag}}\left\{ {\left| {e_{1i,1} } \right|^{\nu - 1} ,\left| {e_{1i,2} } \right|^{\nu - 1} ,\left| {e_{1i,3} } \right|^{\nu - 1} } \right\}\), and \({\mathbf{N}}_{i} = {{\varvec{\updelta}}}_{i} - {\dot{\mathbf{\zeta }}}_{i}\).

Letting \({\mathbf{Z}}_{i} = \left[ {{{\varvec{\upxi}}}_{i}^{{\text{T}}} ,{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}_{i}^{{\text{T}}} } \right]^{{\text{T}}} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{6}\) and using the fuzzy logic system, the lumped unknown term is approximated as

where \({{\varvec{\Phi}}}\left( {{\mathbf{Z}}_{i} } \right)\) denotes the basis function and \({{\varvec{\upvarepsilon}}}_{i}\) denotes approximation error. Using the inequality relaxation technique, (27) can be rewritten as

where \(B_{i} = \max \left\{ {\overline{W}_{i} ,\overline{\varepsilon }_{i} } \right\}\) represents an unknown constant and \(\Phi_{i} = \left\| {{{\varvec{\Phi}}}\left( {{\mathbf{Z}}_{i} } \right)} \right\| + 1\) represents a time-varying function.

Remark 2: While various approximation methods exist, such as RBF neural networks (RBFNN)44 and reinforcement learning (RL)-based45 approaches, fuzzy systems are adopted in this work due to their unique advantages. Compared with RBFNN, fuzzy systems embed expert knowledge through interpretable linguistic rules, enhancing transparency and safety—especially crucial in UAV applications. Unlike RL-based methods, fuzzy systems enable fast online optimization without relying on large-scale datasets or extensive offline training. These features make fuzzy systems particularly suitable for real-time, safety-critical scenarios.

Choose the following fuzzy adaptive non-singular terminal sliding mode controller

where \(k_{1} > 0\), \(k_{2} > 0\), \(\gamma > 0\), and \(\hat{B}_{si}\) is the estimates of \(B_{si} = B_{i}^{2}\). Choose the adaptive law

with \(h_{1} > 0\), \(h_{2} > 0\), and \(\eta > 0\).

Theorem 2:

Assume Assumptions 1 and 2 hold, considering the quadrotor-UAV cluster (1) under the fixed-time adaptive local controller (29) and the indirect fuzzy adaptive law (30).

-

i)

All signals within the system exhibit uniform ultimate boundedness.

-

ii)

The position and velocity tracking errors of each follower UAV can converge to the small region about zero in fixed time.

Proof:

We design the Lyapunov function.

with \(\tilde{B}_{si} = B_{si} - \hat{B}_{si}\). Using (26), we can further get

Substituting the controller (29) and the adaptive law (30) into (32) and using Lemma 7 yields

It follows from Young’s inequality that

Using Lemma 5 and \(x_{1} = 1\), \(x_{2} = \frac{{h_{1} }}{2\gamma }\tilde{B}_{si}^{2}\), \(\alpha = \frac{1 - \mu }{2}\), \(\beta = \frac{1 + \mu }{2}\), \(\rho = \left( {\frac{1 + \mu }{2}} \right)^{{\frac{1 + \mu }{{1 - \mu }}}}\), the following inequality hold

Furthermore, using Lemma 6 and \(x_{1} = \tilde{B}_{si}\), \(x_{2} = B_{si}\), \(\beta = \nu\), it is not difficult to obtain that

Using Lemma 7, substituting (34)–(37) into (33) yields

with \(\kappa_{5} = \min \left\{ {2^{{\frac{1 + \mu }{2}}} k_{1} ,h_{1}^{{\frac{1 + \mu }{2}}} } \right\}\), \(\kappa_{6} = \min \left\{ {3^{{\frac{1 - \nu }{2}}} 2^{{\frac{1 + \nu }{2}}} k_{2} ,2^{{\frac{1 + \nu }{2}}} \gamma^{{\frac{\nu - 1}{2}}} \frac{{\nu h_{2} }}{1 + \nu }} \right\}\), \(\vartheta_{i} = \frac{{h_{1} }}{2\gamma }B_{si}^{2} + \frac{{\nu h_{2} }}{{\left( {1 + \nu } \right)\gamma }}B_{si}^{1 + \nu }\) \(+ \frac{1 - \mu }{2}\left( {\frac{1 + \mu }{2}} \right)^{{\frac{1 + \mu }{{1 - \mu }}}} + \frac{{\gamma^{2} }}{2}\). Using Lemma 3, we obtain that \(V_{i}\) converge to the following small region about zero.

with \(0 < \varepsilon < 1\). From (39), the sliding variable \({\mathbf{s}}_{i}\) converges to a small region around zero, when \(T_{c2}\) satisfies the following conditions

Based on Eqs. (23)–(25), when \({\mathbf{s}}_{i}\) converges to a small region around zero, the tracking errors \(e_{1i}\) and \(e_{2i}\) also can converge to a small region around zero. The convergence time satisfies

Therefore, the fixed-time cooperative control problem can be handled. This concludes the proof for Theorem 2.

Remark 3:

Unlike the literature35,36, by leveraging the recovered state information, a specifically designed fuzzy adaptive nonsingular terminal sliding mode controller is formulated for each quadrotor UAV. In contrast to traditional sliding mode control, this customized controller exhibits superior advantages in terms of position-tracking accuracy, response speed, and stability. It ensures the accomplishment of local position tracking within a predetermined fixed time period. Moreover, an efficient indirect fuzzy identification mechanism is adopted, which incorporates a fuzzy logic system to identify the upper bound of the lumped uncertain term. Additionally, the attitude formation controller can be designed similarly and thus is omitted here.

Simulation results

This section validates the fixed-time formation tracking controller proposed in this paper. In the simulated scenario, the directed topology is depicted in Fig. 3, in which UAV 0 is the leader and only UAVs 1 and 4 can directly access the virtual leader’s information.

To rigorously demonstrate that the convergence rate of the proposed fixed-time controller is independent of the system’s initial conditions, we conducted simulations under two distinct sets of initializations:

Case1: Define the desired trajectory \(p_{0} = \left[ {5\sin \left( {0.1t} \right),5\cos \left( {0.1t} \right),8} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\). We choose the following initial value \(p_{1} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1, \, 1, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(p_{2} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {0, \, 1, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(p_{3} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ { - 2, \, 1, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(p_{4} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ { - 1, \, 1, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(v_{1} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1,{ 1},{ 1}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(v_{2} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1,{ 1},{ 1}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(v_{3} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1,{ 1},{ 1}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(v_{4} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1,{ 1},{ 1}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\).

Case2: \(p_{1} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {2, \, 1, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(p_{2} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {0, \, 1,{ 1}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(p_{3} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ { - 1, \, 1, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(p_{4} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1, \, 1, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(v_{1} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1,{ 1},{ 0}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(v_{2} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1,{ 1},{ 0}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(v_{3} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1,{ 1},{0}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(v_{4} \left( 0 \right) = \left[ {1,{ 1},{ 0}} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\).

All the other parameters are the same. Define \(\hat{B}_{si} \left( 0 \right) = 0\). \(\chi_{1} = \left[ {0.8, \, - 0.8, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(\chi_{2} = \left[ {0.8, \, 0.8, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), \(\chi_{3} = \left[ { - 0.8, \, 0.8, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\), and \(\chi_{4} = \left[ { - 0.8, \, - 0.8, \, 0} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\) denote the formation distances. The external disturbance is \(d = \left( {i - 2.5} \right)\left[ {0.4\sin \left( {0.3t} \right), \, 0.6\sin \left( {0.2t} \right), \, 0.5\cos \left( {0.3t} \right)} \right]^{{\text{T}}}\).

The parameters in the exponential terms are set as \(\mu = {{99} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{99} {101}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {101}}\) and \(\nu = {{103} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{103} {101}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {101}}\), which influence the convergence rate by shaping the Lyapunov function decay rate. The observer gain parameters are chosen as \(l_{1} = 10\), \(l_{2} = 10\), \(b = 0.01\), which determines the convergence of the observer. \(r_{1} = 1\) and \(r_{2} = 1\) are design parameters in the sliding surface definition, which determine the relative weight of error and its derivative in the sliding mode dynamics. \(k_{1} = 100\) and \(k_{2} = 100\) are control gains for the sliding variables, which influence the convergence speed of the sliding surface. \(\gamma = 1\), \(h_{1} = 1\), \(h_{2} = 1\), and \(\eta = 1\) are adaptive update rates. In the FLS, seven fuzzy rules are used with centers \(c_{i} = \left[ { - 3, \, - 2, \, - 1, \, 0, \, 1, \, 2, \, 3} \right]\) and width \(w_{i} = 6\). These settings allow the FLS to approximate a wide range of nonlinear uncertainties effectively.

For Case 1, the simulation results are displayed in Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10. Figure 4 presents the spatial trajectory tracking control implemented on multiple quadrotor UAVs. They take from starting points at an altitude of 0 m, then quickly climb the altitude to correct altitude disturbance, and begin to track the input trajectory of the virtual leader. Finally, the position synchronization mission is completed, and the formation control is also well transformed. The simulation outcomes in Fig. 4 illustrate the good control performance of the fuzzy adaptive controller. The detailed spatial tracking results are shown in Fig. 5. The four quadrotor UAVs complete the altitude climb in about 2 seconds and form an initial formation. In the aspect of speed, as shown in Fig. 6, the direction and speed changes are consistent with the path change in Fig. 5. The entire process of speed changes steadily without any sudden changes, which meets the requirements of practical engineering applications. Moreover, Figs. 7 and 8 provide the tracking errors in terms of spatial position and velocity relative to time. It reveals that the proposed fuzzy adaptive controller can well achieve high position and velocity tracking accuracy even under uncertainties. Owing to the utilization of indirect fuzzy approximation, the proposed controller possesses excellent uncertainty attenuation. Figure 9 presents the control input, which is within the reasonable range for applications. Within the controller, the change of the fuzzy adaptive parameters is depicted in Fig. 10.

To clearly demonstrate that the convergence time of the fixed-time control is unaffected by the initial system’s states, two cases of the system initial value are given in Case 1 and Case 2. For Case 2, the simulation results are displayed in Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14. From Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8 and 11, 12, 13, 14, it can be seen that the fixed-time stability of the system can be ensured under the fixed time controller (29). Furthermore, we can see that the upper bound of settling time is not affected by the initial values of the system. Furthermore, to better demonstrate the performance of the proposed control scheme under two distinct initial conditions, we computed the average RMSE values for both position and velocity errors of the UAV system in each case, as presented in Table 1. Analysis of the obtained RMSE values reveals that the error magnitudes under both initial conditions exhibit remarkable consistency, indicating that the proposed controller achieves similarly high control performance regardless of initial state variations.

To highlight the advantages of the proposed control strategy, a comparative study was conducted with the adaptive FLS-based nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode controller (AFSMC) from46. Under the initial conditions of Case 1, the position and velocity tracking errors of AFSMC are shown in Figs. 15 and 16, respectively. The results demonstrate that while the proposed controller enables the UAV formation to rapidly correct its configuration within 2 seconds (see Figs. 7, 8), AFSMC requires 20 seconds to converge. This comparison clearly indicates the superior convergence speed of the proposed fixed-time controller. Furthermore, as shown in Table 2, the RMSE analysis of both control schemes reveals that the proposed strategy achieves smaller position/velocity tracking errors, confirming its faster convergence rate and enhanced control performance.

Conclusion

For cooperative tracking of quadrotor UAV formation under local communications, a fuzzy adaptive distributed fixed-time control method is proposed. To complete the distributed cooperative tracking task, the method combines a fixed-time distributed state observer, indirect fuzzy identification mechanism, and non-singular terminal sliding mode controller. The proposed control method can ensure the position and velocity tracking errors of each following quadrotor UAV converge to the small region around zero in a fixed time. To substantiate the effectiveness and superiority of our approach, simulation results are presented, showcasing its impressive performance in quadrotor UAV formation cooperative tracking tasks. Prescribed-time formation control, which does not rely on initial values and control parameters, represents a future research direction.

It is important to note that the current fixed-time control’s convergence time depends on controller parameters. Practical issues such as collision avoidance and disturbances also need consideration. Consequently, future research will investigate a simplified prescribed-time control strategy to enable user-specified settling times, alongside the design of integrated collision avoidance mechanisms.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Huang, H., Savkin, A. V. & Huang, C. Scheduling of a parcel delivery system consisting of an aerial drone interacting with public transportation vehicles. Sensors 20(7), 2045 (2020).

Chen, C. J. et al. Identification of fruit tree pests with deep learning on embedded drone to achieve accurate pesticide spraying. IEEE Access 9, 21986–21997 (2021).

Tehseen, A., Zafar, N. A., Ali, T., Jameel, F. & Alkhammash, E. H. Formal modeling of IOT and drone-based forest fire detection and counteraction system. Electronics 11(1), 128 (2021).

Koslowski, R. & Schulzke, M. Drones along borders: Border security UAVs in the United States and the European Union. Int. Stud. Perspect. 19(4), 305–324 (2018).

Mendoza, R. M., Monterrey, F. M., Guayázan, C. M. & Prada, S. R. Design of a strategy for planning of trajectories with avoidance of obstacles of a quadrotor drone used in the characterization of geological. In 2020 IX International congress of mechatronics engineering and automation (CIIMA), pp. 1–6. IEEE (2020).

Guo, H., Chen, M. & Shen, Y. Sliding mode attitude control for a QUAV based on a nonlinear disturbance observer. In Proceedings of 2021 5th Chinese conference on swarm intelligence and cooperative control, pp. 859–868. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore (2022).

Yuan, W., Chen, Q., Hou, Z. & Li, Y. Multi-UAVs formation flight control based on leader-follower pattern. In 2017 36th Chinese control conference (CCC), pp. 1276–1281. IEEE (2017).

Kownacki, C. Multi-UAV flight using virtual structure combined with behavioral approach. Acta Mech. Automat. 10(2), 92–99 (2016).

Wang, N., Dai, J. & Ying, J. UAV formation obstacle avoidance control algorithm based on improved artificial potential field and consensus. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 22(6), 1413–1427 (2021).

Zhou, D., Wang, Z. & Schwager, M. Agile coordination and assistive collision avoidance for quadrotor swarms using virtual structures. IEEE Trans. Rob. 34(4), 916–923 (2018).

Challa, V. R. & Ratnoo, A. Analysis of UAV kinematic constraints for rigid formation flying. In AIAA guidance, navigation, and control conference, p. 2105 (2016).

Crowther, W. J. Rule-based guidance for flight vehicle flocking. Proceed. Instit. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerospace Eng. 218(2), 111–124 (2004).

Kocer, B. B., Tjahjowidodo, T. & Seet, G. G. L. Centralized predictive ceiling interaction control of quadrotor VTOL UAV. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 76, 455–465 (2018).

Zhao, C. et al. Multi-UAV trajectory planning for energy-efficient content coverage: A decentralized learning-based approach. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 39(10), 3193–3207 (2021).

Yu, Z., Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Qu, Y. & Su, C. Y. Distributed finite-time fault-tolerant containment control for multiple unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 31(6), 2077–2091 (2019).

Wu, B., Wang, D. & Poh, E. K. Decentralized robust adaptive control for attitude synchronization under directed communication topology. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 34(4), 1276–1282 (2011).

Meng, Z., Ren, W. & You, Z. Decentralised cooperative attitude tracking using modified Rodriguez parameters based on relative attitude information. Int. J. Control 83(12), 2427–2439 (2010).

Han, Z., Wang, W., Huang, J. & Wang, Z. Distributed adaptive formation tracking control of mobile robots with event-triggered communication and denial-of-service attacks. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 70(4), 4077–4087 (2022).

Díaz, Y., Dávila, J. & Mera, M. Leader-follower formation of unicycle mobile robots using sliding mode control. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 7, 883–888 (2022).

Wang, J., Alattas, K. A., Bouteraa, Y., Mofid, O. & Mobayen, S. Adaptive finite-time backstep control tracker for quadrotor UAV with model uncertainty and external disturbance. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 133, 108088 (2023).

Yu, X., Li, P. & Zhang, Y. The design of fixed-time observer and finite-time fault-tolerant control for hypersonic gliding vehicles. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 65(5), 4135–4144 (2017).

Du, B. H. et al. Quadrotor trajectory tracking by using fixed-time differentiator. Int. J. Control 92(12), 2854–2868 (2019).

Ranjan, S. & Majhi, S. Fixed-time state observer-based robust adaptive neural fault-tolerant control for a quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 39(1), 132–151 (2025).

Ranjan, S. & Majhi, S. Fixed-time observer-based adaptive free-will arbitrary time intelligent fault-tolerant control for an autonomous quadrotor. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 00, 1–24 (2025).

Liu, K. & Wang, R. Antisaturation adaptive fixed-time sliding mode controller design to achieve faster convergence rate and its application. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 69(8), 3555–3559 (2022).

Zhou, S. et al. Fixed-time observer based safety control for a quadrotor UAV. IEEE Trans. Aerospace Electron. Syst. 57(5), 2815–2825 (2021).

Liu, K. et al. Fixed-time disturbance observer-based robust fault-tolerant tracking control for uncertain quadrotor UAV subject to input delay. Nonlinear Dyn. 107(3), 2363–2390 (2022).

Li, Y., Yang, J. & Zhang, K. Distributed finite-time cooperative control for quadrotor formation. IEEE Access 7, 66753–66763 (2019).

Dou, L., Yang, C., Wang, D., Tian, B. & Zong, Q. Distributed finite-time formation control for multiple quadrotors via local communications. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 29(16), 5588–5608 (2019).

Wang, F., He, S., Zhou, C., Gao, Y. & Zong, Q. Distributed practical finite-time formation control of quadrotor UAVs based on finite-time event-triggered disturbance observer. IEEE Syst. J. 18(1), 355–366 (2023).

Liu, L., Zhao, W., Liu, Y. J., Tong, S. & Wang, Y. Y. Adaptive finite-time neural network control of nonlinear systems with multiple objective constraints and application to electromechanical system. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 32(12), 5416–5426 (2020).

Andrieu, V., Praly, L. & Astolfi, A. Homogeneous approximation, recursive observer design, and output feedback. SIAM J. Control. Optim. 47(4), 1814–1850 (2008).

Song, X., Wu, C., Song, S., Zhang, X. & Tejado, I. Performance-guaranteed adaptive fuzzy wavelet neural fixed-time control for unmanned surface vehicle under switching event-triggered communication. IEEE Trans. Vehicular Technol. 73, 16351 (2024).

Xu, H., Cui, G., Ma, Q., Li, Z. & Hao, W. Fixed-time disturbance observer-based distributed formation control for multiple QUAVs. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 70(6), 2181–2185 (2023).

Mechali, O., Xu, L., Xie, X. & Iqbal, J. Theory and practice for autonomous formation flight of quadrotors via distributed robust sliding mode control protocol with fixed-time stability guarantee. Control. Eng. Pract. 123, 105150 (2022).

Mechali, O. & Xu, L. Distributed fixed-time sliding mode control of time-delayed quadrotors aircraft for cooperative aerial payload transportation: Theory and practice. Adv. Space Res. 71(9), 3897–3916 (2023).

Meng, Z., Ren, W. & You, Z. Distributed finite-time attitude containment control for multiple rigid bodies. Automatica 46(12), 2092–2099 (2010).

Liu, K., Wang, R., Zheng, S., Dong, S. & Sun, G. Fixed-time disturbance observer-based robust fault-tolerant tracking control for uncertain quadrotor UAV subject to input delay. Nonlinear Dyn. 107(3), 2363–2390 (2022).

Gao, J., Fu, Z. & Zhang, S. Adaptive fixed-time attitude tracking control for rigid spacecraft with actuator faults. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 66(9), 7141–7149 (2018).

Wang, L. X. & Mendel, J. M. Fuzzy basis functions, universal approximation, and orthogonal least-squares learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 3(5), 807–814 (1992).

Hardy, G. H., Littlewood, J. E. & Pólya, G. Inequalities (Cambridge University Press, 1952).

Sun, Y. & Zhang, L. Fixed-time adaptive fuzzy control for uncertain strict feedback switched systems. Inf. Sci. 546, 742–752 (2021).

Li, H. & Cai, Y. On SFTSM control with fixed-time convergence. IET Control Theory Appl. 11(6), 766–773 (2017).

He, W., Zhang, F., Zhao, Z. et al. Closed-loop dynamics identification and robust neural control for helicopter systems via deterministic learning. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics (2025).

He, W., Zhang, F., Zhao, Z. et al. Reinforcement dynamic learning-based tracking control strategy for an unknown 2-DOF helicopter system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. (2025).

Liu, K. et al. Observer-based adaptive fuzzy finite-time attitude control for quadrotor UAVs. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 59(6), 8637–8654 (2023).

Funding

This research was supported by 2025 Jiangsu Higher Education Blue and Green Project Funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. led the revision, redesigned the distributed fixed-time observer and convergence proofs, coordinated responses to reviewers, and served as guarantor of the work. X.L. developed the indirect fuzzy identification mechanism, implemented the adaptive law, and conducted robustness simulations. M.S. constructed the communication-constrained network model, integrated the observer–controller framework, and performed ablation studies. Z.L. conceived the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and supervised the initial simulation framework. J.Z. and X.L. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Figs. 1–6; M.S. and Z.L. prepared supplementary materials and simulation code. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., Liang, X., Shi, M. et al. Distributed fixed time adaptive cooperative tracking control for quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle. Sci Rep 15, 40567 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24394-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24394-w