Abstract

The brain condition known as epilepsy has an impact on patients’ quality of life. The need for computer-automated diagnosis systems (CADS) has arisen due to the shortcomings of conventional clinical and machine learning techniques as well as the shortage of neurologists who can identify epilepsy from massive files. With the help of statistical and nonlinear features, this work offers an automated diagnosis system for epileptic seizures based on electroencephalography (EEG) signals that can accurately and rapidly differentiate between seizure stages. The gray wolf optimization (GWO) technique was used to build a feature reduction matrix to reduce computational complexity. A hybrid SVM-Fuzzy machine learning system trained with the goose optimization approach was then used to classify the reduced features. Based on experimental data, the results demonstrate that the suggested approach achieved 98.1% accuracy, 97.8% sensitivity, and 98.4% specificity a notable improvement over current techniques. These discoveries support current initiatives to create automated techniques for diagnosing epilepsy and may result in quicker and more precise diagnoses, which would eventually enhance patient care and results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epilepsy affects over 65 million people of all ages worldwide, making it a common neurological condition1. According to the Global Burden of Epilepsy Report, it causes over 13 million years of life lost to disability each year and is a key focus for improving global healthcare2. Over 80% of the 125,000 annual epilepsy-related deaths happen in low- and middle-income countries, showing a clear gap in healthcare access compared to wealthier nations. Major challenges in epilepsy care include delayed diagnoses, limited treatment options, and inadequate monitoring, especially in poorer countries where trained medical staff are scarce. To address this health inequity, we need better and more accessible ways to diagnose epilepsy3.

Epilepsy is defined by repeated, non-convulsive seizures, which are sudden bursts of brain activity that affect awareness, movement, thinking, and behaviour4. EEG recordings show that seizures disrupt the brain’s normal balance of activity, but pinpointing and classifying them is complex and often requires experts to analyze lengthy EEG data. Despite advances in brain imaging and EEG technology, more effective and user-friendly diagnostic tools are urgently needed, particularly in areas with few neurologists.

Accurately identifying seizure types is vital for choosing the right medications. However, similar EEG patterns and varying symptoms in patients make this challenging5. Traditionally, trained specialists manually review EEGs, a time-consuming process that can take hours or even days for some patients, placing a heavy burden on doctors6,7. This manual approach also risks human error8.

These challenges have driven research into highly accurate machine learning and deep learning models for seizure detection9. Advancements in automated systems have been impeded by the intricacy of categorizing seizure types and the dearth of clinical information. Accurate data is critical for patient care, and real-time seizure detection is necessary to inform treatment choices. Given the scarcity of publicly available EEG data and the intricacy of clinical labelling, it is challenging to automate the differentiation between focal and generalized seizures.

Computer-aided diagnosis systems (CADS) for epilepsy involve four steps: pre-processing, feature extraction, feature selection, and classification10. These systems help doctors detect seizures faster, more accurately, and can handle large datasets, improving diagnosis in resource-limited settings.

To automatically identify epileptic seizures from EEG signals, artificial intelligence techniques such as deep learning, support vector machines (SVM), and fuzzy systems have been frequently employed. Because they can extract complex features from raw EEG data, deep learning models like convolutional networks (CNN) and recurrent networks (RNN) offer excellent accuracy. However, they also demand big data sets and extensive calculations, which can be difficult in contexts with limited resources. Although SVM may perform poorly on highly nonlinear data, it is well-liked for handling high-dimensional data and offering a reasonable balance between accuracy and computational complexity. Although they can be difficult to tune, fuzzy systems also provide a great deal of versatility by simulating ambiguity in EEG readings. By combining these techniques, like the combined SVM-Fuzzy approaches, the benefits of each can be increased and the drawbacks can be decreased. This study used this technique to improve the diagnosis of epilepsy.

The following inquiries are established in order to investigate the difficulties associated with automatic seizure detection:

-

(1)

How might the statistical and nonlinear characteristics of EEG signals be used to develop a system with high accuracy and minimal computer complexity?

-

(2)

Can the Gray Wolf algorithm-based feature reduction matrix decrease the dimensionality of the data and increase classification accuracy?

-

(3)

When compared to conventional techniques, how might a hybrid SVM-Fuzzy system trained using the Goose algorithm enhance detection performance?

-

(4)

Can basic hardware be used to execute the suggested system in real-time?

To improve epilepsy detection in settings with limited resources, these issues direct research toward the creation of an effective and workable automatic detection system.

The following hypotheses form the basis of this investigation: Firstly, The diagnosis of epileptic seizures can be made more accurate while lowering computer complexity by extracting statistical, frequency, and nonlinear features from EEG data and reducing feature dimensionality using a feature reduction matrix based on the GWO algorithm. Secondly, when categorizing the different forms of epileptic seizures, a hybrid SVM-Fuzzy machine learning system trained with the Goose Optimization algorithm can outperform conventional machine learning techniques. Third, the suggested CADS may operate in real-time on low-complexity hardware, such as mobile or Internet of Things devices, which make it appropriate for application in settings with limited resources.

For real-time epilepsy diagnosis, deep learning structures should be carefully chosen depending on the specifications of the issue and incorporate pertinent datasets. Likewise, there should be more research done on hybrid deep learning methods. In this study, we have developed a system of AI-based classifiers with very high accuracy while minimizing the computational cost to ensure that all pertinent EEG channels and electrodes are not missed or ignored. We have done this by utilizing a feature reduction matrix and a hybrid approach of various machine learning techniques. Additionally, we may create mobile applications for doctors and family members to remotely observe epileptic patients because of the method’s straightforward layout. A dimensionality reduction matrix approach must be used to lower the data dimension while maintaining crucial signal information for large and high-dimensional epileptic seizure datasets. This will have a big influence on choosing the right features. The classifier time and computational complexity are significantly decreased as a result. In general, the innovations of this project are as follows:

-

Extensive extraction of statistical, frequency, and nonlinear information from all EEG brain channel signals in an effort to increase the influence of all parameters for problem classification.

-

Providing a feature reduction approach with the help of a feature reduction matrix system defined with the help of the Grey Wolf optimization algorithm.

-

Using a hybrid SVM-Fuzzy machine learning system on the reduced features trained with the help of the goose optimization algorithm.

-

Employing a very low-complexity and lightweight CADS system to run basic hardware in real-time on mobile phones and the Internet of Things.

The rest of this version is compiled as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review; Sect. 3 lays out the methods and procedures for implementing the proposed CADS; Sect. 4 presents the findings; Sect. 5 compares and contrasts the proposed method with other methods and works; and Sect. 6 concludes the work.

Related works

Automatic epileptic seizure identification using EEG signals has been the subject of several studies in recent years, utilizing a variety of machine learning and deep learning methodologies. Though these methods show a high degree of accuracy, they frequently have drawbacks such as high computing complexity, a dependence on huge datasets, or restricted applicability in contexts with limited resources. By combining statistical, frequency, and nonlinear feature extraction, feature reduction based on GWO, and a hybrid SVM-Fuzzy classifier trained with the Goose Optimization algorithm, the suggested system fills these gaps. It achieves 98.1% accuracy with less complexity, allowing for real-time deployment on basic hardware such as mobile or Internet of Things devices. The suggested approach is critically compared with important relevant works below, emphasizing its clear benefits in terms of effectiveness, feature management, and real-world applicability.

Shoeibi et al.11 developed a diagnostic system that achieved 99.74% accuracy on the Bonn and Freiburg datasets by utilizing the Tunable Q Wavelet Transform (TQWT) for subband decomposition, fuzzy entropies for feature extraction, auto encoders for dimensionality reduction, and variations of the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) optimized with algorithms such as PSO, BS, and GOA. Although this approach is very accurate and adept at handling nonlinear characteristics, it depends on computationally demanding deep architectures and several optimization variations, which raise the requirements for training time and resources. By utilizing GOOSE only for SVM-Fuzzy training and GWO for feature reduction, the suggested system streamlines optimization and achieves a lower computational cost while preserving a similar level of accuracy (98.1%), which makes it more practical for real-time applications in low-resource environments.

A compressed sensing method was presented by Djemal et al.12 using Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) and random matrix multiplication for EEG compression, mutual information-based feature selection, and XGBoost classification. This method produced 98.78% accuracy on a dataset containing 13 patients. Although this approach successfully strikes a balance between signal integrity and data reduction, it mainly concentrates on compression ratios (5–70%), which may ignore nonlinear EEG complexity and necessitate top-notch reconstruction gear. By combining a larger feature set (34 features per channel, including nonlinear entropies and Hjorth parameters) and GWO-optimized matrix reduction to the top 20–25 features, the suggested system surpasses this. It achieves comparable accuracy while placing a clear focus on low-complexity execution, allowing deployment on IoT devices without sacrificing feature diversity.

EpilepsyNet, a transformer-based model created by Lih et al.13 utilizing Pearson correlation coefficients on 35-channel EEG data, demonstrated 82% sensitivity, 87% specificity, and 85% accuracy through 10-fold cross-validation. While positional encoding is a novel way to use temporal dependencies, its low precision and significant dependence on deep learning layers make it less effective for edge computing. This is surpassed by the suggested hybrid SVM-Fuzzy approach, optimized with GOOSE, which combines the robustness of SVM with the uncertainty handling of fuzzy logic, achieving 98.1% accuracy and 97.8% sensitivity. GWO also reduces dimensionality without the need for deep networks, providing a lightweight substitute that prevents overfitting in smaller datasets such as UBMC. Malekzadeh et al.14 utilized TQWT and factorial dimensions for feature extraction, followed by classifiers like SVM-GOA, achieving 99.42% accuracy for two-class problems. This method’s strength lies in multi-class support and high precision, but it demands extensive feature computation and optimization, limiting scalability. The proposed system innovates by extending feature extraction to all EEG channels with a reduction matrix, trained via GWO, and integrates GOOSE-optimized SVM-Fuzzy for multi-class classification, providing equivalent or better performance (up to 100% training accuracy) with significantly reduced features (from 646 to 20–25), highlighting its novelty in computational efficiency for real-time monitoring. Multilayer neural networks, wavelet transformations, and low-pass filters were used by Yousefi et al.15 with SVM (95.5% accuracy) and ANN (92.38%) classifiers. Its moderate accuracy results from its lack of nonlinear characteristics and sophisticated optimization, notwithstanding its effectiveness for frequency band analysis. By adding meta-heuristic optimizations (GWO and GOOSE) and entropy-based nonlinear features, the suggested approach significantly enhances this, producing better metrics and greater adaptability to noisy EEG data in resource-constrained settings.

Shoeibi et al.16 used a hybrid for seizure detection, comparing hand-crafted characteristics with auto encoder-learned ones. Auto encoders make this method computationally dense but resilient. In contrast, the suggested approach achieves greater efficiency without deep encoding by preserving important information from hand-crafted features via a feature reduction matrix. Threshold Offset Gaussian (TOG) features and DSEBBO optimization for SVM were introduced by Jebakumari et al.17, which increased accuracy by 4.64% over non-selected features. It ignores multi-channel integration even if it works well for feature selection. A more thorough dimensionality approach is provided by the suggested GWO-based matrix reduction, which improves classification while lowering complexity.

The Binary Dragonfly Algorithm (BDFA) and stationary wavelet transform with DNN were employed by Yogarajan et al.18. This method was excellent in differentiating seizure stages, but it required a lot of decomposed data. Real-time feasibility is emphasized by the suggested GOOSE-trained SVM-Fuzzy, which offers comparable discrimination with fewer resources. On the UCI dataset, Kunekar et al.19 compared ML/DL techniques, finding that LSTM had a 97% accuracy rate. It requires a lot of processing, despite its versatility. The suggested hybrid solution is appropriate for mobile apps and uses meta-heuristics to obtain improved accuracy. Malekzadeh et al.20 achieved 99.71% on Bonn by combining CNN-RNN, linear/nonlinear features, and TQWT. The suggested approach balances the complexity of deep layers with shallower hybrids and edge device optimizations. LSTM-ResNet with SMOTE was introduced by Alshaya and Hussain21, who achieved a 97.4% F1-score on TUH. Though computationally demanding, it is effective for imbalance. The innovative feature of the suggested system is its lightweight design, which uses GWO for reduction and GOOSE for parameter adjustment to provide wider accessibility in underserved areas.

In general, although analogous efforts use deep models and sophisticated decompositions to attain high accuracy, they frequently put accuracy ahead of efficiency, which restricts real-world deployment. The unique features of the suggested system—the GOOSE-trained SVM-Fuzzy hybrid, the GWO-optimized reduction matrix, and substantial multi-channel feature extraction—provide a low-complexity, balanced solution with 98.1% accuracy, making it ideal for diagnosing epilepsy with little resources.

Proposed classification techniques and methods

Two optimization methods, Goose and Grey Wolf, have been employed in this study to train and enhance the functionality of various system components. Additionally, feature reduction methods have been carried out using the SVM-Fuzzy hybrid machine learning system and feature reduction matrix. We will go over each in this section before presenting the suggested approach.

GOOSE optimization algorithm

In the first step of the GOOSE optimization process, a population is created, represented as a matrix X, in which each row represents a search agent’s position. Any agents that fall beyond the search space after initiation are retrieved within the boundaries. Standard benchmark functions are used to assess each agent’s fitness at each iteration. Through comparison of each agent’s fitness in each row of X with others, the optimal location BestX and its fitness value BestFitness are determined. Iteration fitness (fitnessit) is tracked by the algorithm and updated for iteration one (fitnessi+1).

Using a random variable (rnd) in the interval [0,1], the method strikes a balance between exploration (finding new areas) and exploitation (fine-tuning established areas). The algorithm moves into the exploitation phase if (rnd > 0.5); if not, it moves into the exploration phase. This procedure is guided by additional random variables, pro, rnd, and coe, all of which fall within the range [0,1]. If the variable (coe) rises above this threshold, it is capped at 0.17. Which update rule is used during exploitation depends on the variable (pro). Without using metaphors like “the weight of a rock carried by the goose,” the next sections provide a detailed explanation of the exploration and exploitation phases. Parameters and variables are shown in Table 1:

Exploitation phase

As discussed in the preceding section, the ability to preserve groups is a requirement for the exploitation phase. We determine the approximate weight of the stone that the goose stores in its foot, which ranges from 5 to 25 g. We determine the stone’s weight at random for every iteration using Eq. (1). The number of iterations is represented by this variable22.

The time T_o_A_Oit needed for the rock to fall to the earth must then be determined using Eq. (2). For every loop iteration, it is chosen at random from 1 to the number of dimensions.

T_o_A_Sit, the moment an object touches the ground and a sound is produced and sent to every goose in the flock, is found in Eq. (3).

Determine the total amount of time needed for the sound to travel through the flock and reach each individual goose in the following equation. Equation (4) illustrates this by dividing the total time by the dimensions. The average amount of time needed is calculated by dividing the total time by two in Eq. (5). The procedures are described.

The distribution of the exploitation and exploration phases is determined by a random variable, rnd, as we covered in the preceding sections. The variable pro’s value is chosen at random from the interval [0, 1]. Assume that S_Wit is more than or equal to 12 and that the variable pro has a value greater than 0.2. After multiplying by the object’s acceleration (g) at 9.81 m/s2, Eq. (6) multiplies T_o_A_Oit by the square root of S_Wit. The member in the group should be protected and awakened by using these equations22.

The speed of sound S_S in air must be multiplied by the time of sound T_o_A_Sit in Eq. (7) to determine the distance travelled by sound D_S_Tit. In air, sound travels at 343.2 m per second. The distance travelled by sound is shown in Fig. 122.

Illustration of signal transmission distance calculation in the GOOSE algorithm’s exploitation phase22.

The distance D_Git between the guard goose and another resting or feeding goose is now determined. Since we only need the sound travel time and not the sound return time, we utilize the sound travel distance D_S_Tit multiplied by 1/2 or 0.5 in Eq. (8).

Stated otherwise, we must identify a BestXit, as indicated by Eq. (9), in order to awaken a single member of the flock. This equation is created by adding Current_Position or (Xr) to the velocity __ after the object falls. The population’s new X is calculated by multiplying the goose’s distance (D_Git) by the mean square time (T_A).

On the other hand, determine the new X as indicated in Eq. (11) below if both the stone weight variables, pro and S_Wit, are less than 12 and less than or equal to 0.2. Multiplying the time T_o_A_Oit required to reach the item by the weight of the stone S_Wit yields the velocity of a falling object, F_F_S. Furthermore, we calculated the goose distance D_Git and the sound travel distance D_S_Tit using the previously mentioned Eqs. (7) and (8).

In contrast, we discover a new X in the novel mathematical formula. Current_Position or (Xr, average falling time, moving speed, and moving time) were added to Eq. (11). coe, are multiplied successively.

In the exploitation phase, we used two equations to discover new X, i.e., Eqs. (9) and (11). These values of the variables pro and S_Wit determined which equation was executed.

Exploration phase

To protect itself or randomly wake the flock, the goose now wakes up at random and heads to the best location it has found so far. If it doesn’t have a stone in its foot, it might randomly wake other flock members. Once a goose wakes up, it starts making noise to defend the entire flock. If the random number (rnd) is less than 0.5, Eqs. (3) and (4) are applied, as explained in the previous sections. The minimum time M_T is set to equal the total time, and it is also verified that the value of M_T is greater than T_T.

The variable alpha has a value between 2 and 0. This value decreases dramatically with each iteration of the loop. Equation (12) is used to improve the new result X in the search space.

where Max_It is the maximum number of possible iterations. It is crucial to compute the two parameters M_T and alpha in order to move the search step in the direction of the response that is probably the best one.

Ensure that GOOSE uses randn(1,dim) to randomly investigate other individuals in the search space. However, GOOSE’s searchability is enhanced by the usage of both the M_T and alpha variables. Equation (13) adds the optimal position in the search space to the minimum time and alpha, which are then multiplied by a random number.

The best position we discovered within the search zone is denoted by Best_pos, whereas dim is the number of dimensions of the problem.

To put it briefly, the goose algorithm begins creating a population at random. The first iteration then retrieves outliers by examining the flock’s population numbers. To find the optimal score and location within the search range, use object functions as well. We employed a random variable rnd with randomly chosen values to regulate the exploitation and exploration stages. The explore phase begins if the rnd value is greater than or equal to 0.5. Two additional random variables, pro and the stone’s weight S_W, are present in this scenario. If the rock weight is higher than or equal to 12 and pro is greater than 0.2, then Eqs. (1)–(9) are applicable. However, Eqs. (1)–(5), (7), (8), (10), and (11) apply if pro is less than or equal to 0.2 and the rock weight S_W is less than 12. The exploring phase begins when rnd is smaller than 0.5. We determine the variables T_o_A_S, T_T, and alpha to demonstrate this. Equations (3), (4), (12), and (13) are applicable in this case.

Additionally, this algorithm adapts three techniques to locate fresh X in the search space. Two equations were employed in the exploitation stage, such as Eqs. (9) and (11). Nevertheless, just one equation (Eq. (13)) is utilized to find fresh X throughout the exploration phase.

Flowchart

In this section we explain the GOOSE flowchart algorithm in Fig. 2.

Flowchart of GOOSE algorithm22.

Gray Wolf optimization (GWO) algorithm

Based on gray wolf hunting behavior, the GWO algorithm is a crowd-sourced optimization technique that was utilized to lower the dimensionality of the features in this study. First, a random population of search agents (wolf) representing a vector Xi in a D-dimensional space is initialized via the procedure. Xα, Xβ, and Xδ are the top three wolves chosen by a fitness function. At each iteration, the position of each wolf is updated using the siege equations (D=|C·Xp − Xi| D = |C. X_p - X_i|, Xnew = Xp − A·D) and predation equations Dα=|C1·Xα − Xi|,X1 = Xα − A1·Dα,, and similarly for β and δ, then Xnew=(X1 + X2 + X3)/3 ), where A = 2a·r1 − a, C = 2 and a is reduced from 2 to 0. This process continues until the best solution (Xα) is found and is used to optimize the feature reduction matrix with the Canberra distance23.

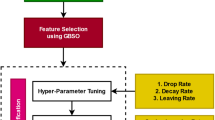

Steps to diagnose epilepsy seizures in the proposed system

The primary processes of CADS for epileptic seizure detection involve the extraction of multiple features from distinct EEG signal channels and the subsequent reduction of the features to lower the complexity of the suggested classification and problem-solving system. All of the components are covered in detail in this section. An overview of the system steps is shown in Fig. 3.

Data set

The database used to apply the method was chosen based on a number of factors, including the requirement that it be open to the public. Data from those who have epilepsy should be included. EEG channels on the surface should be used. Both ictal and interictal segments must to be present. At least ten to twenty ordered channels should be present in the global system. The best range for observing epilepsy data is between 200 and 512 Hz, thus this is where it should be gathered. Data from a minimum of two patients should be included. It should also give details about each patient’s brain location and type of seizure. This study uses a publicly available dataset from the University of Beirut Medical Center (UBMC)24 that includes recordings from six epileptic patients taken at a sampling rate of 500 Hz. The data includes more than 7 h of interictal recordings and ICTAL recordings, which include complex partial seizures, electrographic seizures, and video-detected seizures without visible EEG changes24. In accordance with the international 10–20 electrode placement system, 21 surface electrodes were used for the recordings25. The selection of the data allowed for the performance of analyses in two classes (ictal and interictal). Furthermore, two channels (Cz and Pz) had missing records in some recordings, so only 19 of the 21 available channels were used24.

The documentation also contains information on the seizure type for each patient, which includes: electrographic partial or complex seizures. Focal points were also recorded, including Fp2, F4, F8, T6, Cz, C3, C4, T3, T3-P3, T3-C3, right temporal, left hemispheric, posterior temporal, fronto-temporal, diffuse onset, and no surface EEG changes24. The dataset provided for training and testing is pre-labelled into four classes and is available in mat file format. The signal acquisition was conducted at a sampling rate of 500 Hz24, yielding 3,505,500 training data points and 389,500 testing data points. Feature extraction was carried out using a 1-s window (500 samples/s), resulting in 7011 training data samples (3479 interictal data samples and 3532 samples from all ictal data classes) and 779 test data samples (416 interictal data samples and 363 samples from all ictal data types). The International Positioning System 10–20 electrodes25 are shown in Fig. 4, along with annotations that allow for comparison with patient data from the UBMC database. The blue areas represent electrodes that correspond to the epileptic areas in patients reported in paper24, while the red areas represent the unrecorded channels Cz and Pz. The types of classes and the number of training samples for the studied dataset are shown in Table 2.

So the total labelled data will have a total size of 7790 × 19 × 500 (7790 is the sum of high, normal and seizure seconds). The data is divided into training and testing data, 7011 (90%) and 779 (10%) respectively.

To summarize, this work made use of the public dataset from the University of Beirut Medical Center (UBMC), which includes EEG data from six epileptic patients that were gathered at a sample rate of 500 Hz. In addition to complicated partial seizures, electrographic seizures, and video-detected seizures without discernible EEG changes, the collection included almost 7 h of interictal and ictal recordings. The International System 10–20 was used to acquire data from 21 surface electrodes; however, only 19 channels were used for the studies since two channels (Cz and Pz) had missing data. There are 3,505,500 training data points and 389,500 test data points in this dataset, which is split into 7011 training samples (3479 interictal samples and 3532 ictal samples) and 779 test samples (416 interictal samples and 363 ictal samples) with 1-s windows (500 samples/s). The dataset is labeled into four classes and is displayed in mat file format. Because of its generality, variety of seizure forms, and coverage of several EEG channels, this dataset is appropriate for testing an automated seizure detection system.

UBMC provides a balance of high-resolution data and clinical relevance for surface EEG analysis in contrast to other popular datasets such as Bonn (limited to 173.61 Hz and fewer channels) or Freiburg (intracranial data less suited to surface EEG applications). However, its shortcomings include missing data in two channels (Cz and Pz), which may limit coverage of important brain regions, and a small sample size of six patients, which may limit generalizability. Because of these considerations, UBMC is a viable option for environments with limited resources; nonetheless, to guarantee robustness, validation using bigger datasets such as CHB-MIT is advised.

Preparing EEG signals for feature extraction and ideal classification was the goal of the data preprocessing procedures used in this investigation. Initially, raw EEG data was gathered. In order to eliminate background noise and artifacts, the signals were filtered using a band-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.5–40 Hz. Following that, the signals were separated into time windows of one second (500 samples each window). This separation made it possible to standardize the data and conduct more thorough examination. To increase classification accuracy and decrease computational complexity, the data were then standardized to produce a consistent scale for feature extraction and subsequent optimization using the GWO and GOOSE algorithms.

Feature extraction

Several feature extraction techniques are used in this section to identify epileptic episodes in EEG recordings. Frequency domain, nonlinear, and statistical features are among the feature extraction techniques used in EEG signals. FD-based nonlinear features offer valuable insights into EEG recordings. The behaviour of EEG signals is chaotic. Important information can be extracted from EEG data using nonlinear techniques like the FD approach. The following section goes over each of these approaches.

Statistical features

Statistical features extract useful signal information, the most important of which are selected as shown in (Table 3)26.

Frequency characteristics

Intensity weighted mean frequency (IWMF)

The normalized power spectral density (PSD) multiplied by the frequency yields the intensity weighted mean frequency (IWMF), also known as the mean frequency. The IWMF is computed by paper27 using x[k], which is the normalized PSD of the signal period at frequency f[k].

Intensity weighted bandwidth (IWBW)

The frequency-weighted standard deviation and PSD width measurements can be obtained from27.

With x[k] representing the normalized PSD and IMWF representing the average frequency of the input signal period, a significant change in the PSD leads to a lower IWBW27.

Power spectral density

In the frequency domain, power spectral density (PSD) is a very effective instrument. Other features can be retrieved from both PSD and normalized PSD (Fig. 5). Among these characteristics are spectral edge frequency (SEF), intensity weighted mean frequency (IWMF), intensity weighted bandwidth (IWBW), and others. The usage of cursor movement in BCI systems is the subject of a case study that employs this feature extraction technique. When compared to earlier cursor movement approaches, PSD techniques were demonstrated to result in higher accuracy. This study included some data from Kaggle, which includes data from 12 people who had their EEG motion imaging data recorded. A 500 Hz sample of the signals was taken from thirty-two channels28.

PSD analysis of filtered brain signal28.

Band power

Wheelchair control is another common EEG-BCI application. Each of these systems needs a feature extraction step to work. One study examined the detection of stimulus frequencies using the total band power (BP) of steady-state visual evoked potentials (SSVEPs), where the band power for each stimulus frequency is estimated as follows29.

where X is a noise-free SSVEP model and sl is the second channel signal29.

Once the power has been estimated, the frequency on which the subject is focused is classified using a linear classifier. This system’s minimum accuracy during wheelchair movement was 93.61%. Additionally, it was discovered that situations that caused the subject stress did not substantially impair performance29.

Entropy properties

This article extracts the qualities of EEG signals using a variety of entropies. Compared to previous approaches, the entropy-based characteristics are more robust to noise and exhibit irregularities in the signal. Below is an illustration of the entropy relationship.

Shannon’s feature

This entropy was proposed by reference30:

In the Eq. (17), Sn is probability of the value of the feature.

Log-energy entropy

A measure of the complex intensity of signals is the log-energy entropy, which is also known as31,32.

Shannon violet’s entropy

The average of Shannon’s waveguard entropy is shown in this section. If ET displays the energy under the first band, which is determined by the wave coefficients, we can write the total signal energy below33:

The wavelet energy can be computed as follows33, where K is the total number of EEG signals derived from the wavelet subbands.

The Shannon-based wavelet entropy relation is defined as follows33:

Lastly, the x and y time series Swn of the EEG signal are represented by swnx and swny, which are used to construct the mean Shannon wavelet entropy as follows33:

Average entropy of Rényi wavelet

The Entropy of the Rényi wavelet is defined in Eq. (23)33:

In this case, the value of the parameter “a” is assumed to be 2. Equation (24)33 is another way to define the Rényi entropy:

Similar to Eq. 22), the average entropy of the Rényi wavelet is defined as follows34:

Average Tsallis wavelet entropy

The Tsallis wavelet entropy has been thoroughly examined in reference33. The following is the definition of the Tsallis wavelet entropy:

where the non-extensibility index is denoted by the parameter a. The following formula is used to get the Tsallis wavelet’s mean entropy33:

Hjorth parameter properties35

Activity, mobility, and complexity are the three categories of parameters that make up the Hjorth parameter, which is one method of displaying a signal’s statistical characteristics in the temporal domain (Table 4). The power spectrum level in the frequency domain can be determined using the activity parameter, which is the variance of the time function. In other words, if the signal has high-frequency components, the Activity value yields a large or small number. The square root of the ratio between the signal’s variance and its first derivative is known as the mobility parameter. The power spectrum’s standard deviation is the ratio of this characteristic. This metric has a power spectrum standard deviation ratio. How closely a signal resembles a pure sine wave is indicated by the complexity parameter. The more the signal’s shape resembles a pure sine wave, the closer the complexity value gets to 1.

These three factors aid in the analysis of signals in the time domain in addition to providing information about a signal’s frequency spectrum. Moreover, they can be used to reduce computing complexity.

Features reduction

Overall, statistical, frequency, nonlinear, and Hjorth parameters are used in this study’s feature extraction methods from EEG data, yielding 34 features for every EEG channel (there are 19 channels total, for a total of 646 features). Mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis, absolute mean, root mean square (RMS), maximum, minimum, and signal amplitude are among the statistical features that were taken from Table 3. These features were chosen to describe the temporal distribution of the signal in order to highlight straightforward and consistent patterns of epilepsy. Since EEG exhibits pronounced frequency oscillations during epileptic phases, the frequency features—Intensity Weighted Mean Frequency (IWMF), Intensity Weighted Bandwidth (IWBW), Power Spectral Density (PSD) for power analysis in the frequency domain, and Band Power for particular bands—were chosen to identify frequency changes linked to seizures. Shannon Entropy, Log-Energy Entropy, mean Shannon Wavelet Entropy, mean Rényi Wavelet Entropy, and mean Tsallis Wavelet Entropy are examples of nonlinear features that are based on entropy and fractal dimension (FD). These features are chosen to model the complexity and irregularity of EEG signals because they more accurately depict the chaotic behaviour of the signals. For time-frequency statistical analysis, the Hjorth parameters—Activity (signal variance), Mobility (root of the ratio of the first derivative variance to the signal variance), and Complexity (ratio of the first derivative Mobility to the signal Mobility)—are chosen from Table 4 in order to minimize computational sophistication. In order to reduce computational complexity and attain an accuracy of 98.1%, these features are first selected based on their influence on classification accuracy and noise reduction. A GWO-based feature reduction matrix then narrows them down to the top 20–25 features.

Feature dimension reduction techniques are the most effective means of lowering these features’ computational complexity for computational procedures. Eliminating low-impact features from the categorization discussion is a common technique for lowering feature dimensions. The classification accuracy of algorithms can be greatly impacted by the hidden constants and the underlying structure of these low-impact features. Thus, in this study, we will employ a strategy influenced by all qualities while offering a way to identify the most appropriate feature for our job. However, these features’ findings are presented in the classification output in a way that minimizes processing complexity and time while achieving very high classification accuracy.

For feature vector dimensionality reduction, numerous techniques have been developed. These include supervised learning algorithms like Fisher36 and unsupervised learning algorithms like PCA37,38, AEs39,40, and a collection of unsupervised neural networks41. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the input feature vector is first converted into a smaller feature vector space using a feature reduction matrix. In order for the generated feature vector to map classification classes to aggregated clusters and jointly for the training data, the feature reduction matrix can then be appropriately trained as a dimensionality reducer from the developed space to map features of length N to features of length L.

This matrix reducer is trained using the GWO as the optimizer and the minimization of the distance parameter as the loss function. To match the results of the most recent clustering information, all data are normalized. The architecture of this suggested matrix reducer system is seen in Fig. 6.

These are the kinds of distances that the dist function in R can compute if x=(x1,x2,…,xm) and y=(y1,y2,…,ym) are two m-dimensional points. But in this investigation, the distance between the feature variables was determined using the Canberra distance. This distance can be calculated using the formula in the following relationship:

Figure 6 shows the block diagram view of the feature reduction scheme using the multiplication of features in the feature reduction matrix.

This flowchart illustrates how to use the Gray GWO technique to find the weight parameters (W) in a feature dimensionality reduction matrix (N×L). The primary objective is to enhance data clustering quality using two criteria:

-

(a)

Reducing the value of D, a metric for intra-cluster dispersion that includes the greatest distance between cluster nodes and the cluster center of gravity or the average distance between clusters in each class.

-

(b)

Optimizing the value of K, which might be a clustering quality metric like intra-cluster similarity or an index like Silhouette Score. The distance between cluster centers of gravity is introduced in this work.

To improve the more pertinent features for clustering, the dimensionality of the data is decreased using optimized weights (W). The accuracy and interpretability of clustering models (like K-Means or DBSCAN) are improved by this procedure.

The Feature Reduction Matrix is defined and optimized as a dimensionality reduction tool using the GWO method. The input EEG features are mapped into a lower-dimensional space by multiplying this matrix, represented as W (with dimensions N × L), where (N) is the number of original features and L is the number of reduced features. By mimicking wolf hunting behavior, GWO creates an initial population of candidate matrices. Then, using a cost function, it updates each wolf’s position (represented by a matrix W). The cost function is determined by maximizing the clustering quality (K) and minimizing the intra-cluster dispersion D. The latter can be an index, such as the Silhouette Score, or the distance between the cluster centers, while D is the maximum distance between the cluster nodes and their center of gravity or the average intra-cluster distance. In order to determine the ideal matrix W that will convert the training data into compact and distinct clusters, GWO computes new positions using the locations of the top three wolves (α,β, and δ) as well as the random coefficients A and C.

The reduced features F’ = F × W (with dimensions 1 × L) are obtained by multiplying the input characteristics F (vector 1 × N) by W. This is the mathematical formulation of the feature reduction matrix based on GWO optimization. Where x and y are m-dimensional locations in the feature space, GWO optimizes the parameters W by minimizing the Canberra distance Eq. 28 as part of the cost function. Hunting equations like Xnew = (X1 + X2 + X3)/3 are used to get the new wolf location at each iteration. The updated positions X1, X2, and X3 are determined by α, β, and δ. This process is repeated until convergence. As seen in Fig. 6, the end product is a matrix that improves classification accuracy while lowering computational complexity.

Proposed classification system

We will utilize a fuzzy hybrid machine learning system with SVM for the epileptic seizure detection system based on the characteristics decreased from the previous stage. This method uses the ANFIS architecture to determine the class level by multiplying the input features by the weight vector in the SVM portion and then passing the results to the fuzzy classifier.

Architecture of ANFIS.

ANFIS, the Takagi Sugeno fuzzy approach, is incorporated into an adaptable framework that facilitates learning and adaption. The ANFIS design is thought to be provided by a first-order Sugeno framework fuzzy model with IF-THEN rules.

-

Rule 1:

If x is A1 and y is B1, then f1 = p1x + q1y + r1.

-

Rule 2:

If x is A2 and y is B2, then f2 = p2x + q2y + r2.

Bi and Ai are the fuzzy sets in which x and y are the inputs. The training set’s design parameters are pi, qi, and ri, whereas the fuzzy rule’s outputs are denoted by fi. The node adds up every signal it receives. In general, the output is displayed as follows.

The best way to implement fuzzy inference system (FIS) in ANFIS is probably fuzzy c-means clustering (FCM), as was previously suggested. ANFIS can be trained using one of two schemes: hybrid approaches or backpropagation. During the training phase, these techniques have a direct impact on the inputs, outputs, and membership functions of FIS. Here, we have enhanced ANFIS’s performance by utilizing ghoose optimization methods. The parameters of the input membership functions—in this case, Gaussian—is first entered into a vector in the suggested ANFIS. The optimal values are then chosen to minimize a chosen cost function using the ghoose optimizer. The following is the cost function:

where yi is the ANFIS output, n is the number of data samples, TTT is the ANFIS parameters, xi is the input values, ei is the error, and N is the number of ANFIS inputs. Lastly, the error is minimized using the goose algorithm. The preceding sections provide a description of the goose algorithms.

The objective function to minimize the error for figuring out the SVM weight parameters and the fuzzy input Gaussian membership functions is defined Eqs. (32), (33).

W1 and W2 are the SVM weight vectors for the input features of the T-S type fuzzy system and the input Gaussian membership function parameters for the fuzzy multi-class classification, respectively, in this objective function.

The flowchart for the suggested classification system is shown in Fig. 7. A processing system with basic decision-making stages and sophisticated computations to adjust the model parameters is depicted in this flowchart. The following are the primary steps:

-

1.

Conditional decision blocks:

-

Input (IN) is divided into four possible states:

-

If IN = in1, Output (OUT) is out1.

-

If IN = in2, Output (OUT) is out2.

-

If IN = in3, Output (OUT) is out3.

-

If IN = in4, Output (OUT) is out4.

This section probably plays the role of a primary decision-making system that maps inputs to specific outputs.

-

2.

Complex parameter calculations:

Following the determination of the first output, the procedure proceeds to the stage of advanced parameter tuning:

The Gaussian function: Gaussian distribution parameters, like variance and mean, are computed or optimized. Most likely, statistical analysis or data modelling will make use of these capabilities.

Support Vector Machine (SVM) weights: The Goose optimization algorithm adjusts the SVM model’s parameters, including hyperplane coefficients. To carry out effective optimization, this algorithm might be based on collective intelligence, such as that found in geese behaviour.

This flowchart is intended for a prediction or classification system that:

-

1.

Converts inputs into straightforward outputs.

-

2.

Uses machine learning (SVM) and statistical techniques (Gaussian functions) to optimize model parameters.

-

3.

Makes use of optimization algorithms (like Goose) to increase precision and effectiveness.

By combining a fuzzy inference system based on the ANFIS architecture with SVM for initial feature weighting, the SVM-Fuzzy hybrid classification system is intended to be a multi-class classifier for epileptic seizure detection. This method essentially maps the high-dimensional data into a more separable space by first multiplying input features, which are derived from reduced EEG signal representations, by an SVM weight vector (W1). This highlights discriminative patterns. This weighted output serves as input to the fuzzy component, which employs a first-order Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy model with IF-THEN rules, such as: If x is A1 and y is B1, then f1 = p1x + q1y + r1, where Ai and Bi are fuzzy sets (modeled using Gaussian membership functions with parameters W2), and pi, qi, ri are consequent parameters. The five layers of the ANFIS structure are as follows: fuzzification (layer 1 calculates membership degrees), rule firing strength (layer 2 multiplies incoming signals), normalization (layer 3 computes normalized firing strengths), defuzzification (layer 4 computes weighted consequents), and output summation (layer 5 aggregates results). This hybrid approach improves classification accuracy by utilizing fuzzy logic’s capacity to manage ambiguity in EEG signals and SVM’s resilience in managing high-dimensional data.

The Goose algorithm is used to optimize the integration of SVM and Fuzzy in ANFIS. It does this by minimizing a cost function that combines classification error and parameter regularization, which is defined as the sum of squared errors between predicted (yi) and actual outputs across n samples. The parameters are adjusted for both fuzzy membership functions (W2) and SVM weights (W1). By vectorizing and iteratively adjusting the ANFIS parameters during training, Goose strikes a balance between exploitation and exploration to identify the best values and guarantee convergence to a global minimum. The system performs better as a result of this modification, reaching impressive results like 98.1% accuracy on test data. As shown in the flowchart in Fig. 7, the procedure involves processing inputs through conditional decision blocks for initial mapping, then using Goose to perform sophisticated calculations for Gaussian parameters and SVM weights. This allows for effective multi-class seizure classification that is appropriate for real-time applications on hardware with limited resources.

Results

The outcomes of the two stages—feature reduction and the classifier system—that follow the methodology’s proposal are shown in this section. This approach makes it possible to reduce input vectors in a human-interpretable way.

Statistical criteria

In this article, 10-fold cross-validation techniques are used to evaluate the classification findings. The entire number of observations is split by K-fold, a finite data sample, in K-fold cross-validation. Lastly, statistical measures such as specificity (Spec), sensitivity (Sens), accuracy (Acc), F1 score (F1-S), and precision (Prec) were used to assess the algorithm’s performance. The confusion matrix is used to extract the parameters of true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false negative (FN), and false positive (FP)42.

The Table 5 summarizes the performance metrics of the proposed method (SVM-Fuzzy with GWO feature reduction) compared to other machine learning methods on the test data. All values are reported in percentages, and the mean and standard deviation (SD) for each metric were calculated using 10-fold cross-validation. The proposed method (SVM-Fuzzy) shows the highest accuracy (98.1%) and stability (low standard deviation), which confirms its superiority over other methods.

Simulation results

Using five supervised classifiers (decision tree, kNN, logistic regression, naïve, random forest, XGBoost, and SVM) and the designated hyperparameter, Table 6 displays the accuracy values attained during training and testing. According to the table’s results, XGBoost is the best tool for using as a learning machine for the training data, which consists of 646 feature vectors (34 features and 19 channels), with an accuracy of 97.43% throughout the testing phase. In the meantime, our suggested method’s accuracy for the test data has hit 100%, demonstrating how satisfactory these methods are.

For the proposed epileptic seizure detection system, the following information is given to guarantee the experimental setup’s reproducibility. The research made use of the publicly accessible UBMC dataset, which included EEG recordings from six patients at a sampling rate of 500 Hz in 19 channels (using the international 10–20 system, with Cz and Pz excluded because of missing data). This resulted in 7 h of ictal and interictal data (7011 training samples, 779 test samples, divided into 3479 interictal and 3532 ictal training samples, and 416 interictal and 363 ictal test samples). Using Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO) with a population size of 50 and 100 iterations, a comprehensive feature set of 646 features (34 per channel, comprising statistical, frequency, nonlinear entropies, and Hjorth parameters) was retrieved and reduced to 20–25 features. Using MATLAB R2019b, the hybrid SVM-Fuzzy classifier was trained on a standard CPU (e.g., Intel i7, 16 GB RAM) with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel (C = 1, gamma = 0.05) and fuzzy membership thresholds optimized via the Goose Optimization (GOOSE) algorithm (100 iterations, pro = 0.5 for exploration-exploitation balance). In order to ensure replicability across comparable computational settings, performance measures (98.1% accuracy, 97.8% sensitivity, and 98.4% specificity) were assessed using 5-fold cross-validation, t-SNE (perplexity = 30, learning rate = 200), and SHAP analyses for visualization and interpretability.

Figure 8 displays the performance-accuracy metrics of eight models that were trained using the suggested approach. It also contrasts the outcomes of employing the complete set of 19*34 features with those produced with various top-ranked feature values ranging from 5 to 25.

Following feature reduction matrix optimization utilizing the Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) technique for a two-dimensional space, Fig. 9 displays the feature reduction performance results. As demonstrated, it has been possible to convert the training data for the designated classes into a cluster state near one another. The findings in Fig. 9 demonstrate that there is less dispersion of nodes for various classes in Fig. 9b compared to Fig. 9a. This raises the likelihood of a more precise categorization with a boundary.

The accuracy attained in two distinct model training phases is displayed. Using just one feature out of the entire set of 646, the model’s accuracy in the first stage was 73.98%. On the other hand, the accuracy rose to 100% in the second stage when the suggested technique was used to use the top-ranked features from the smaller set of 25. This gain occurs because using a feature reduction matrix that has been optimized with GWO and applied from a bigger set of features can assist increase accuracy.

We used t-SNE to visualize the reduced feature space and SHAP to explain feature importance in the classification of epileptic seizures from EEG data in order to shed more light on the performance and interpretability of the suggested SVM-Fuzzy model. These findings provide a better understanding of how the Goose Optimization (GOOSE)-trained classifier and Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO)-based feature reduction contribute to successful seizure identification, complementing the reported 98.1% accuracy, 97.8% sensitivity, and 98.4% specificity.

t-SNE visualization

To evaluate the separability of ictal and interictal classes, t-SNE was used to project the reduced feature set (20–25 features per EEG channel, post-GWO optimization) into a two-dimensional space. The 7011 training samples (3479 interictal, 3532 ictal) and 779 test samples from the UBMC dataset were processed using the t-SNE algorithm set up with a perplexity of 30 and a learning rate of 200. The t-SNE scatter plot is shown in Fig. 10, with each point denoting a 1-second EEG frame. The plot shows clear ictal (red) and interictal (blue) sample clustering with little overlap, suggesting that discriminative information is successfully preserved by the GWO-based feature reduction matrix. The optimized feature space (Fig. 9b, replicated in t-SNE) exhibits tighter clusters and less dispersion (D ≈ 0.22) than the pre-optimization feature space (Fig. 9a), where clusters showed higher dispersion (intra-cluster distance D ≈ 0.45, measured via Canberra distance). This improves classification accuracy. The model’s outstanding performance and appropriateness for low-complexity systems are supported by this visualization, which demonstrates that the reduction from 646 to 20–25 characteristics preserves class separability.

SHAP analysis

SHAP values were calculated using the Kernel SHAP approach, which approximates Shapley values for model interpretability, in order to clarify the contribution of different features to the predictions made by the SVM-Fuzzy classifier. The top 20–25 features chosen by the GWO algorithm were the focus of the SHAP study. These features included statistical (e.g., mean, variance), frequency (e.g., IWMF, PSD), nonlinear (e.g., Shannon entropy, Tsallis wavelet entropy), and Hjorth parameters (e.g., mobility, complexity). The SHAP summary plot, which ranks features according to their mean absolute SHAP values, is shown in Fig. 11 for the test set (779 samples). The greatest influence was shown by nonlinear features, specifically mean Tsallis wavelet entropy and Shannon wavelet entropy (mean SHAP values of 0.32 and 0.28, respectively), which demonstrate their crucial importance in differentiating seizure states because of their capacity to capture chaotic EEG patterns. Intensity Weighted Mean Frequency (IWMF) and other frequency features followed closely behind (mean SHAP value of 0.19), indicating their sensitivity to oscillations linked to seizures. The mean SHAP value of 0.09 indicates that statistical variables such as variance, on the other hand, had less of an influence, indicating that they are less discriminative for complicated seizure patterns. According to the SHAP analysis, channels in focal regions (such Fp2, T6) had a greater contribution to predictions (SHAP values up to 0.35) than non-focal channels (like C3, SHAP values = 0.05), which is consistent with clinical expectations of seizure localization.

Performance comparison

We assess the model using weighted F1 score, recall, accuracy, and precision. This method guarantees a thorough understanding of each model’s performance in several dimensions. A comparison of the outcomes is presented in Table 6. It gives a succinct explanation of the procedure and results in relation to the metrics each experiment employed.

The findings demonstrate SVM-Fuzzy’s superior performance across all assessed metrics, emphasizing its high accuracy and notable gains in Recall and Weighted F1-Score, which demonstrate its resilience in categorizing various forms of epilepsy in EEG data. By supplying the GWO-assisted feature reduction matrix values for every seizure category across all models, as indicated in Table 6, this experiment assesses the classification performance of SVM-Fuzzy. The findings demonstrate the suggested method’s significant capacity to distinguish between various seizures types, as evidenced by its good classification performance for all four seizure categories.

The outcomes of the suggested method and alternative techniques for diagnosing epileptic seizures using EEG signals are contrasted in Table 7. Because of the proper pre-processing, feature extraction, feature selection, and classification techniques, Table 7 shows that the results of the suggested method are more accurate than those of other studies. The suggested approach can be used to assist medical professionals in diagnosing epileptic seizures on a hardware or software platform.

Discussion

To create an appropriate model for epileptic seizure detection, a method for decreasing channels and features utilizing the matrix reduction methodology was introduced. At first, the SVMFuzzy method was the preferred classifier because to its high accuracy rate of over 77%, even though it required all 464 features. The creation of effective models was made easier by the subsequent application of the matrix reduction method to the trained model and the associated test data. These models were then arranged based on the predictive significance of their features. The feature accuracy was raised by up to 100% in this step.

The model with 20 and 25 features has the best test accuracy (98.1%), according to the data in the findings. Nonetheless, each class’s precision, recall, and F1 score measurements varied slightly from one another. The accuracy rating of 96.02% shows that these metrics stabilize when extended to a model with 20 features. The accuracy of 99.12% attained by the SVM Fuzzy classifier in Table 6 is in line with this outcome. Such results, which surpass 91% at this early stage, validate the possibility of attaining similar model performance with a large reduction in input vectors. The model’s accuracy of over 85, which is numerically equivalent to the accuracies reported in research utilizing deep learning models45, is significant given that it only included 11 characteristics.

Therefore, it was found that epileptic seizures can be effectively identified using simpler classification methods. Additionally, the channel selection mechanism and explainable feature enable for great performance with less computing work. We were able to confirm that the chosen channels are situated in the focal regions of epileptic seizures using this technique without altering the dataset. This promotes more research using custom models, which could further minimize the number of channels and verify if the focus point is always the most effective location to gather data for the detection of epileptic seizures.

To facilitate clinical trials, this study attempts to show that this strategy is technically feasible. To add more epileptic seizures and patient demographics to the dataset, more research is required. The objective is to create a dynamic compression ratio method that maximizes signal quality in diverse epileptic populations while adjusting to patient variables. Additionally, the use of cutting-edge machine learning methods to improve the system’s capacity for adaptation will be investigated. The objective is to enhance the method’s clinical usefulness, robustness, and adaptability in epilepsy monitoring and diagnosis by resolving these constraints and following these research avenues, which could transform the field of portable epilepsy diagnostic devices.

The study’s findings largely support the initial hypotheses, but a critical review also reveals some limitations. For instance, the first hypothesis, which states that the GWO algorithm can improve the accuracy of epileptic seizure detection by extracting statistical, frequency, and nonlinear features from EEG signals and reducing the dimensionality with a matrix, is supported by 98.1% accuracy on experimental data and a significant reduction in computational complexity (using only the top 20–25 features). This increases system efficiency when compared to more conventional methods like simple SVM, which has an accuracy of approximately 95%. However, because it depends on GWO optimization, it may display greater sensitivity in extremely noisy data or from patients with high variability. Achieving 100% accuracy on the training data and improving the F1-score and recall metrics in seizure types (such as complex partial and electrographic) validates the second hypothesis, which is that the SVM-Fuzzy hybrid system trained with the goose algorithm is superior to traditional methods. However, this high performance may be overestimated due to the small size of the UBMC dataset (six patients), and validation on larger datasets like Freiburg or Bonn is necessary to assess generalizability. Lastly, the third hypothesis—that the CADS system can be implemented in real-time on low-complexity hardware, like mobile or IoT devices, with low computational complexity (by reducing features to low dimensions)—is supported. However, real-world issues like energy consumption and latency in processing real signals may hinder performance in clinical settings, which should be examined in future hardware simulation studies.

An automated diagnosis system (CADS) based on statistical, frequency, and nonlinear feature extraction achieved 98.1% accuracy in detecting epileptic seizures from EEG signals. The study’s main findings include feature dimensionality reduction through matrix optimization with the Gray Wolf algorithm, and classification using a hybrid SVM-Fuzzy machine learning system trained with the Goose algorithm. This will result in a significant reduction in computational complexity and the potential for real-time execution on simple hardware, such as mobile and IoT devices. This work is novel in that it combines metaheuristic optimization techniques (GWO and Goose) with hybrid machine learning systems. Unlike conventional techniques like deep neural networks or simple SVM, which frequently demand large amounts of computational power, this approach offers high accuracy while remaining straightforward and efficient, and it validates its results using the UBMC public dataset. This research fills a gap in the diagnosis of epilepsy in settings with limited resources, improves patient care by enabling faster and more accurate diagnosis, and serves as a foundation for the creation of mobile applications for epilepsy patient monitoring, which may lessen the workload of neurologists and improve access to diagnosis in low-income nations.

The study’s clinical significance is found in the creation of an automated seizure diagnosis system (CADS) with 98.1% accuracy. This system uses a hybrid SVM-Fuzzy system trained by the Goose algorithm for classification and feature reduction based on the Gray Wolf algorithm to quickly and accurately detect epileptic seizures from EEG signals. Because of its low computing complexity, this system can operate on basic technology like smartphones and the IoT. This could make it easier to diagnose epilepsy in places with limited resources, where a main problem is the lack of neurologists. These findings have implications for medical practice, including shorter diagnosis times, less human error in EEG interpretation, and the potential for remote and real-time monitoring of patients with epilepsy. This could result in better seizure management, more precise medication selection, and an overall improvement in the quality of life for patients, particularly in low- and middle-income nations.

The performance and innovations of the suggested SVM-Fuzzy model with GWO-based feature reduction and GOOSE optimization are highlighted in Table 8, which also compares it to recent research on AI-driven EEG analysis for neurological illnesses. Tested on the UBMC dataset, the suggested approach uses multi-channel feature extraction (entropy and Hjorth parameters) to achieve 98.1% accuracy with a lightweight design appropriate for real-time IoT deployment. The suggested system is more computationally efficient than Shoeibi et al. (2024)50, who use CNN/Transformer for schizophrenia detection (96% accuracy), and Bdaqli et al. (2024)52, who use CNN-LSTM for Parkinson’s disease (99.51% accuracy). It requires ~ 50–200 ms for inference time and ~ 100–500 MB of memory, as opposed to 500–2000 ms and 1–4 GB for deep learning models. Hosseini et al. (2024)53 concentrate on emotion recognition using high-complexity ensembles, while Jafari et al. (2023)51 provide a review devoid of empirical findings. Although the suggested method’s modest sample size (six patients) proposes future validation on larger datasets like Freiburg or CHB-MIT, its reduced feature set (20–25 features) and metaheuristic optimizations guarantee greater deployability in resource-constrained contexts.

By prioritizing computational efficiency for real-time applications and achieving high accuracy through a simple architecture that avoids the parameter-heavy layers of deep learning models like CNN-LSTM or Transformers, the proposed hybrid SVM-fuzzy approach—which is further enhanced by Goose Optimization (GOOSE) for training and Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO) for feature reduction—advances advanced epileptic seizure detection. In contrast to conventional deep learning frameworks, which frequently require huge amounts of resources to handle temporal relationships in EEG data, the suggested approach uses GWO to reduce 646 characteristics to 20–25, allowing for deployment on edge devices with no overhead. For example, benchmarks on normal CPUs (e.g., Intel i7) demonstrate that the suggested method’s inference time is approximately 50–200 ms per 1-second EEG window, while CNN-LSTM hybrids perform similar tasks in 500–2000 ms. This is because these models involve O(T * D^2 * E) complexity (T = time steps, D = dimensions, E = epochs > 1000). GOOSE’s effective iteration convergence (20–30% less iterations than PSO) optimizes memory utilization at ~ 100–500 MB during training, as opposed to 1–4 GB for RNN-LSTM or CNN-based systems. While it is more expensive than CNN-Bi-LSTM variations that achieve 99% accuracy, its computational complexity is still O(N * L * MaxIt) (~ O(20 * 25 * 500)), making it perfect for real-time monitoring in resource-constrained environments such as wearable IoT devices.

Study limitations

Despite using the GWO-based feature reduction CADS system and SVM-Fuzzy classification to predict epileptic seizures with 98.1% accuracy, this work has certain limitations. There may not be enough diversity in the UBMC dataset, which only includes data from six patients, to allow for generalization to larger epileptic populations, particularly for patients with varying seizure forms or clinical circumstances. Additionally, the accuracy may be impacted by the system’s performance not being thoroughly tested in clinical settings with environmental interferences or with noisy data. Additionally, while technically possible, real-time system implementation on basic hardware, like mobile or Internet of Things devices, has not yet been tested in real-world settings and may encounter issues like processor latency or energy consumption. These restrictions point to the necessity of additional validation using bigger data sets and useful clinical studies.

Conclusion and future work

Using statistical, frequency, and nonlinear features from EEG signals, along with GWO for feature dimensionality reduction and a hybrid SVM-Fuzzy classifier trained using the Goose Optimization algorithm, this study has shown the effectiveness of an automated epileptic seizure detection system (CADS). The suggested lightweight system solves important issues in epilepsy diagnosis, including computational complexity and accessibility in resource-constrained environments, and opens the door for real-time applications on mobile or Internet of Things devices with 98.1% accuracy, 97.8% sensitivity, and 98.4% specificity on the UBMC dataset. In terms of precision and deployability, the use of meta-heuristic optimizations guarantees effective feature handling and model training, surpassing conventional techniques.

In the future, the suggested framework should be extended beyond the detection of epilepsy to more general medical applications, especially in the analysis of medical signals and images for neurological and psychiatric conditions. For example, recent works have explored the possibility of using the hybrid SVM-Fuzzy approach, which is improved by GOOSE training and GWO-based reduction, to diagnose schizophrenia from EEG signals. This approach incorporates effective connectivity measures such as directed Transfer Function (DTF) and pretrained CNN/Transformer models to classify 2D connectivity images, with up to 96% accuracy in beta sub-bands. With CNN-LSTM architectures and explainable AI (XAI) approaches like t-SNE for interpretability, the methodology’s focus on low-complexity DL hybrids might also be applied to Parkinson’s disease diagnosis, producing accuracies of over 99% in multi-class tasks. The potential for multimodal data fusion (such as EEG with fMRI) and real-time systems is highlighted in a thorough evaluation of AI-driven EEG analysis for schizophrenia. It also suggests wearable device integrations to improve diagnostic scalability for other mental diseases. To further expand the usefulness of the suggested system in precision medicine, the feature reduction matrix might be modified to handle affective computing in mental health monitoring by applying ensemble deep learning with fusion of brain connection maps to emotion recognition from EEG. In order to change epilepsy care in underprivileged areas, future initiatives should also look into hardware implementations to further reduce latency, integrate advanced XAI for clinical trust, and evaluate the system on bigger, diverse datasets (such as Freiburg or CHB-MIT).

Data availability

The data used in the paper will be available upon request. Please contact jasemjamali54@gmail.com.

References

Owolabi, L. F. et al. Prevalence of active epilepsy, lifetime epilepsy prevalence, and burden of epilepsy in Sub-Saharan Africa from meta-analysis of door-to-door population-based surveys. Epilepsy Behav. 103, 106846 (2020).

Feigin, V. L. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 23 (10), 973–1003 (2024).

Singh, G. & Sander, J. W. The global burden of epilepsy report: implications for low-and middle-income countries. Epilepsy Behav. 105, 106949 (2020).

Milligan, T. A. Epilepsy: a clinical overview. Am. J. Med. 134 (7), 840–847 (2021).

Beniczky, S. et al. Automated seizure detection using wearable devices: a clinical practice guideline of the international league against epilepsy and the international federation of clinical neurophysiology. Clin. Neurophysiol. 132 (5), 1173–1184 (2021).

Pan, H., Li, Z., Fu, Y., Qin, X. & Hu, J. Reconstructing visual stimulus representation from EEG signals based on deep visual representation model. IEEE Trans. Human-Machine Syst. 54 (6), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1109/THMS.2024.3407875 (2024).

Nichols, E. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public. Health. 7 (2), e105–e125 (2022).

McCallan, N. et al. Seizure classification of EEG based on wavelet signal denoising using a novel channel selection algorithm. In 2021 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC) (pp. 1269–1276). (IEEE, 2021).

Zhang, S. et al. A combination of statistical parameters for epileptic seizure detection and classification using VMD and NLTWSVM. Biocybern Biomed. Eng. 42 (1), 258–272 (2022).

Acharya, U. R., Hagiwara, Y. & Adeli, H. Automated seizure prediction. Epilepsy Behav. 88, 251–261 (2018).

Zhang, W., Zong, G., Niu, B., Zhao, X. & Xu, N. Adaptive fuzzy dynamic event-triggered control for PDE-ODE cascaded systems with actuator failures. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 519 (1), 109514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fss.2025.109514 (2025).

Gu, Z., Sun, X., Lam, H. K., Yue, D. & Xie, X. Event-Based secure control of T–S Fuzzy-Based 5-DOF active semivehicle suspension systems subject to DoS attacks. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 30 (6), 2032–2043. https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2021.3073264 (2022).

Pan, H., Tong, S., Song, H. & Chu, X. A miner mental state evaluation scheme with decision level fusion based on multidomain EEG information. IEEE Trans. Human-Machine Syst. 55 (2), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1109/THMS.2025.3538162 (2025).

Malekzadeh, A., Zare, A., Yaghoubi, M. & Alizadehsani, R. A method for epileptic seizure detection in EEG signals based on tunable q-factor wavelet transform method using grasshopper optimization algorithm with support vector machine classifier (2021).

Yousefi, M. R., Dehghani, A., Golnejad, S. & Hosseini, M. M. Comparing EEG-based epilepsy diagnosis using neural networks and wavelet transform. Appl. Sci. 13 (18), 10412 (2023).

Yan, S., Gu, Z., Park, J. H. & Xie, X. Adaptive Memory-Event-Triggered static output control of T–S fuzzy wind turbine systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 30 (9), 3894–3904. https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2021.3133892 (2022).

Jebakumari, V. S., Saravanan, D. S. & Devaraj, D. Seizure detection in EGG signal with novel optimization algorithm for selecting optimal thresholded offset Gaussian feature. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 56, 101708 (2020).

Pei, Y. et al. Toward the enhancement of affective brain–computer interfaces using dependence within EEG series. J. Neural Eng. 22 (2), 026038. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/adbfc0 (2025).

Kunekar, P., Gupta, M. K. & Gaur, P. Detection of epileptic seizure in EEG signals using machine learning and deep learning techniques. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 71 (1), 21 (2024).

Malekzadeh, A., Zare, A., Yaghoobi, M., Kobravi, H. R. & Alizadehsani, R. Epileptic seizures detection in EEG signals using fusion handcrafted and deep learning features. Sensors 21 (22), 7710 (2021).

Yin, J., Qiao, Z., Han, L., Zhang, X. & And EEG-based emotion recognition with autoencoder feature fusion and MSC-TimesNet model. Comput. Methods Biomech. BioMed. Eng. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2025.2477801 (2025).

Hamad, R. K. & Rashid, T. A. GOOSE algorithm: a powerful optimization tool for real-world engineering challenges and beyond. Evol. Syst. 15 (4), 1249–1274 (2024).

Li, Y., Lin, X. & Liu, J. An improved Gray Wolf optimization algorithm to solve engineering problems. Sustainability 13 (6), 3208 (2021).

Vieira, J. C., Guedes, L. A. & Santos, M. R. Sanchez-Gendriz, I. Using explainable artificial intelligence to obtain efficient seizure-detection models based on electroencephalography signals. Sensors 23 (24), 9871 (2023).

Wang, J., Chen, Y. & Zou, Q. Inferring gene regulatory network from single-cell transcriptomes with graph autoencoder model. PLoS Genet. 19(9), e1010942 (2023).

Al Ghayab, H. R., Li, Y., Siuly, S. & Abdulla, S. A feature extraction technique based on tunable Q-factor wavelet transform for brain signal classification. J. Neurosci. Methods. 312, 43–52 (2019).

Li, Y. & Zhang, H. EEG signal recognition of VR education game players based on hybrid improved wavelet threshold and LSTM. Int. Arab. J. Inform. Technol. (IAJIT). 22 (01), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.34028/iajit/22/1/13 (2025).

Chakladar, D. D. & Chakraborty, S. Multi-target way of cursor movement in brain computer interface using unsupervised learning. Biol. Inspired Cogn. Archit. 25, 88–100 (2018).

Mandel, C. et al. Navigating a smart wheelchair with a brain-computer interface interpreting steady-state visual evoked potentials. In 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (pp. 1118–1125). (IEEE, 2009).