Abstract

The association between greenness exposure and hearing thresholds and the underlying mechanism are unclear. Therefore, this cross-sectional study aims to assess the relationship between greenness exposure and hearing thresholds and whether this relationship is mediated by air pollutants. Our study involved 6016 occupational people examined at an occupational disease screening center. Mean exposure concentrations of air pollutants and green indices [Standardized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI)] were assessed for 250 m, 500 m, and 1000 m buffer zones according to work address. A generalized linear model was used to assess the association between the two, taking into account the influence of workplace clustering effects and applying cluster-robust standard errors (CRSE) to correct for clustering effects. Mediation analysis was used to examine the impact of air pollutant exposure on these associations. After correcting for confounders, compared to the lowest quartile group, exposure to more green space significantly improves hearing thresholds. However, we have not yet found a significant association between air pollutants and the relationship between exposure to green environments and hearing thresholds. Sensitivity analyses also yielded similar results. In summary, increasing exposure to visible green environments outdoors in the workplace may help protect hearing thresholds, but the protective mechanism requires further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the acceleration of global industrialization, the numerous health issues brought on by occupational noise exposure have grown in prominence and urgency1. Occupational noise, as a widespread environmental stressor, not only damages the digestive, respiratory, and immune systems but also threatens workers’ hearing and may induce a range of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and myocardial infarction1,2,3,4,5,6. Stimulation by high-intensity noise can cause varying degrees of mechanical damage to hair cells, including rupture of the oval window and capillaries, and in severe cases, the stapes are observed to peel away from the basement membrane. Hearing can be directly impacted by this mechanical injury on how hair cells work.

According to studies, around 600 million workers globally are at risk of occupational noise-induced health effects7. Over 10 million employees in China are presently subjected to detrimental noise levels. Studies showed that almost all adults experience bilateral hearing loss in later life, including progressive and irreversible bilateral hearing loss8. Occupational noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is a prevalent occupational disease in industrialized nations, primarily caused by prolonged noise exposure9.

An area containing vegetation, such as grass or trees, can be described as a “green space"10. Researchers frequently consider the greenness of a household’s residential area as a significant predictor of their overall greenness exposure level. Numerous health benefits associated with spending time in green space have been reported, such as decreased obesity11, better cardiovascular health12,13,14, enhanced mental health15,16,17,18,19, strengthened immune system20,21, and improved birth outcomes22. The possible health advantages of being around green have been explained by several different theories. Green space may have a positive impact on several aspects, including increasing an individual’s level of physical activity, effectively reducing psychological stress, and improving social cohesion. Additionally, they can significantly lower the risk of exposure to undesirable environmental factors like air pollution and noise23,24. Furthermore, a strong correlation between air pollutant exposure and hearing loss has been demonstrated25. Therefore, it was postulated that green space might affect hearing thresholds through air pollutant exposure. This study aimed to investigate the association between greenness in the neighborhood of noise-exposed occupational populations and hearing and also to observe whether air pollutant mediated this association.

Existing research has primarily focused on the impact of residential greenness26,27,28,29, neglecting the health benefits of workplace green space. Given that adults spend a significant portion of their time at work, the public health value of workplace green space cannot be overlooked. Currently, only one study has addressed the analysis of workplace green space30, leaving a critical gap in the literature that urgently needs to be addressed. A deeper exploration of the health impacts of workplace green space not only advances research in this field but also provides new insights for public health interventions and urban planning.

Methods

Study population

The procedures and protocols for this cross-sectional study have been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hebei Medical University (approval number: 2024-010). All participants signed written informed consent forms prior to enrollment (the informed consent form is as follows). The initial participants in this study included adults who participated in health assessments at occupational disease screening center from January 2021 to March 2024. Since the green space data for the first three months of 2024 did not accurately represent the exposure for the entire year, we excluded the data from the first quarter of 2024 (January to March). Therefore, the final statistical analysis covered participants from January 2021 to December 2023. This center, located in Hebei Province, is tasked with conducting occupational disease and health evaluations. It is equipped to perform six primary categories of occupational health examinations, encompassing assessments for exposure to hazardous chemicals, dust, harmful physical and biological factors, examinations for special workers, and evaluations for radiation workers.

We fully utilized the physical examination data of the study population, which included several aspects, such as lifestyle and demographics. We collected 26,078 data entries and performed data cleaning on these records to guarantee data quality. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: (1) participants had to work in settings where they would be exposed to noise dangers. According to GBZ/T 229.4-2012 “Classification of Occupational Hazards in the Workplace—Part 4: Noise,” a noise-exposed work environment is defined as one where there are sounds that are harmful to hearing, detrimental to health, or pose other hazards, and where the A-weighted equivalent sound level of noise exposure is ≥ 80 dB for 8 h per day (or 40 h per week); (2) they had to be able to give a precise address of their place of employment. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) data on key variables such as smoking, drinking, and hearing thresholds were outliers or missing; (2) data on duplicate measurements, only the most recent date of the medical examination was retained. In the end, 6,016 individuals were involved in the study. The flowchart for this study is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.The analysis’s participants originated from 109 workplace locations in total.

Outcome assessment

The pure-tone average hearing threshold (PTA) for each ear is strictly measured in accordance with the GBZ 49-2014 standard: using an annually calibrated pure-tone audiometer in a soundproof room with background noise ≤ 25 dB(A). After the subject has been away from noise exposure for ≥ 16 h, a physician who has undergone standardized training and passed the qualification assessment sequentially measures the hearing thresholds at 500 Hz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, and 4 kHz. The “increase by 5, decrease by 10 method” (with three repetitions and the minimum value taken) is used, and the PTA is calculated independently for each ear (as the average of the four frequencies).

Exposure assessment

This study assesses green space coverage using three vegetation indices: the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), the Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI), and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI). NDVI calculates vegetation coverage from near-infrared and red light reflectance, with values [−1,1] (positive for vegetation, negative for water/bare ground; negatives set to zero), with the formula being: \(\:\text{N}\text{D}\text{V}\text{I}=\left(\text{N}\text{I}\text{R}-\text{R}\text{e}\text{d}\right)/\left(\text{N}\text{I}\text{R}+\text{R}\text{e}\text{d}\right)\). However, NDVI is sensitive to soil interference.

SAVI addresses this by adding a soil adjustment factor (L, ranging − 1 to 1), improving accuracy in low-coverage areas. When vegetation is dense (L = 0), SAVI matches NDVI, With the formula being: \(\:\text{S}\text{A}\text{V}\text{I}=\left(\right(\text{N}\text{I}\text{R}-\text{R}\text{e}\text{d})/(\text{N}\text{I}\text{R}+\text{R}\text{e}\text{d}+\text{L}\left)\right)\times\:(1+\text{L})\).

EVI further enhances precision by incorporating blue light reflectance and atmospheric correction, making it more reliable in dense vegetation. All three indices range [− 1,1], but EVI better reflects vegetation productivity, With the formula being: \(\:\text{E}\text{V}\text{I}=\text{G}\times\:\frac{\text{N}\text{I}\text{R}-\text{R}\text{e}\text{d}}{\text{N}\text{I}\text{R}+{\text{C}}_{1}\times\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{d}-{\text{C}}_{2}\times\:\text{B}\text{l}\text{u}\text{e}+\text{L}}\) .

The three indices are obtained from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and are updated every 16 days at a resolution of 250 m. Every residence receives greenness measurements twice a month. We constructed a composite image reflecting the average annual greenness exposure level by superimposing and averaging 24 images collected over the course of a year, and further calculated the average annual green space exposure for three years. Using the Gaode Map open platform (https://ditu.amap.com), we determined the corresponding latitude and longitude based on the survey population’s workplace address information. We then created buffer zones of 250, 500, and 1000 m based on the latitude and longitude. The selection of the buffer radius is based on commonly used scales from previous studies, while also considering its behavioral significance in the workplace context31,32. These distance ranges are intended to reflect the short to medium distances that the workforce may travel during breaks or commuting. To estimate the annual average exposure value of greenness, we calculated the mean value of all the pixel points in the buffer zones (Fig. S2). Geographic distribution processing and all greenness computations were carried out using ESRI’s ArcGIS 10.2 program (v10.2, Redlands, CA, USA).

Air pollutant concentrations

Ambient air pollutants data were obtained from the Shijiazhuang Environmental Monitoring Center. Using an automated data reporting system, the station collected 24-hour daily average concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), as well as 8-hour daily average concentrations of ozone (O3) from eight monitoring stations in Shijiazhuang. The detailed work addresses of the study population and the addresses of the air monitoring stations were converted into specific latitude and longitude coordinates using the Baidu map (https://www.baidu.com/INDEX.PHP) coordinate system and GPSspg (http://www.gpsspg.com/bs.htm) coding services (http://jingweidu.757dy.com/). The inverse distance weighting (IDW) method was used to calculate the average exposure levels of air pollutants during the study period.

Covariates

In the directed acyclic graph (DAG), we adjusted for factors such as age, gender, smoking, drinking, and BMI. Additionally, based on prior knowledge, we also adjusted for ‘working age’ and ‘diagnosed ear disease’, as these are known significant risk factors for hearing thresholds. Although we assumed these variables are independent of green space exposure (hence no arrows pointing to exposure are drawn in the DAG), adjusting for them can reduce the residuals of the outcome model, improve estimation accuracy, and control for any potential unmeasured confounding. The values assigned to each variable are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical analyses

In descriptive analysis, we represented continuous variables using the mean, standard deviations, or percentiles. For categorical variables, we used frequencies and percentages to express them. Using Spearman’s correlation analysis, we examined the correlation between the NDVI, EVI, and SAVI values of vegetation in different buffer zones in the workplace.

We used generalized linear models to examine the connection between hearing thresholds and greenness. Since the research subjects were nested within different workplaces, there may be intraclass correlation. We therefore used cluster-robust standard errors (CRSE) and adjusted for the workplace as a clustering variable. This method effectively controls for the correlation between individuals within the same workplace, avoiding underestimation of the standard error and ensuring the validity of statistical inference. The basic model 1 was initially constructed, and adjusted for age and sex. Then, we built the main model 2, on top of the base model 1 and further adjusted it for working age, BMI, diagnosed ear disease, smoking, and drinking. The NDVI, SAVI were categorized into quartiles and we used the lowest quartile as the reference group. The results were expressed as β coefficients (95% CI). We also performed a linear trend test using the median greenness exposure as a continuous variable, and green space indicators were analyzed as continuous variables to examine their association with hearing thresholds.

We invoke a 3-node restricted cubic spline analysis for examining nonlinear associations between workplace greenness exposure and hearing thresholds. Stratified analyses were conducted for each type of pollutant to examine whether the associations between these variables differed. Specifically, each pollutant was stratified by median to further examine the potential moderating effect of air pollutant exposure on the relationship between green exposure and hearing thresholds. We studied the interaction between workplace green space indicators and air pollutants. Based on the median division standard, green space indicators and air pollutants were divided into high and low groups for analysis33. Furthermore, we assessed the potential mediating effects of air pollutant exposure on green exposure and hearing thresholds using the “mediation” package in R and estimated standard errors by generating 5000 iterations. We used the method proposed by Huang to assess direct effect, indirect effect, and total effect with the corresponding 95% CIs34.

At last, We also conducted sensitivity studies to make sure our findings were robust. Specifically, we incorporated green space levels in the 500 m and 1000 m buffer zones into the analytical model to investigate the connection between the hearing thresholds and the green space. In addition, we also conducted sensitivity analysis using the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI).

All statistical analyses in this study were performed in R software version 4.4.1 and IBM SPSS26. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 6016 subjects were included in this study. Among them, 80.04% were male, with an average age of 33.21 years and an average BMI of 25.13 kg/m2. 82.16% of the subjects had no history of smoking, and 59.86% had no history of alcohol use. 90.71% of participants had no clinically diagnosed ear diseases. In the entire study population, the average hearing thresholds for the left and right ears were 20.62 dB and 21.01 dB, respectively. Table 2 summarizes the hearing thresholds and environmental exposure measurements of this medical examination population. The correlation results between green space indicators across different workplace buffer zones are presented in Fig. S4 (in Supplementary Materials).

Green space and hearing thresholds

Tables 3 and 4 present the results of the association analysis between green spaces exposure and hearing thresholds in noise-exposed populations. Overall, higher levels of green space exposure were significantly associated with improved hearing. After adjusting for covariates such as sex, age, smoking and drinking, BMI, diagnosed with ear diseases, and working age, regression analysis showed that compared with the lowest quartile group, the highest green index exposure group had significantly improved hearing thresholds, specifically: left ear NDVI: β = − 0.816 (95% CI: − 1.192 to − 0.440), right ear NDVI: β= − 0.843 (95% CI: − 1.235 to − 0.450); left ear SAVI: β = − 0.699 (95% CI: − 1.073 to − 0.325), right ear SAVI: β = − 0.633 (95% CI: − 1.108 to − 0.158). Continuous variable analysis showed that each 0.1 unit increase in NDVI and SAVI indices was significantly associated with a decrease in hearing thresholds. For every 0.1 unit increase in NDVI, the left ear hearing threshold decreases by 1.753 dB (95% CI: − 2.375 to − 1.131), the right ear hearing threshold decreases by 1.805 dB (95% CI: − 2.629 to − 0.981); For every 0.1 unit increase in SAVI, the left ear hearing threshold decreases by 2.165 dB (95% CI: − 3.059 to − 1.270), the right ear hearing threshold decreases by 2.252 dB (95% CI: − 3.633 to − 0.872). In addition, the interquartile linear trend test showed a linear trend for all (p linear trend < 0.05). We found that the exposure-response curve tended to flatten before declining. However, the exposure-response curves showed that the association between SAVI and the right ear was nonlinear (P for nonlinear < 0.005). Moreover, for the NDVI250 greenness index, its association with the left and right ear hearing thresholds both show significant nonlinear characteristics (Fig. S5, in supplementary materials).

Stratification, interaction, and mediation analysis

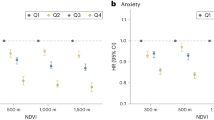

Figures 1 and 2 depict the link between an individual’s exposure to greenness (as a continuous variable) and hearing thresholds at several degrees of air pollution exposure. We found that NDVI and SAVI values were significantly associated with improved hearing function in noise-exposed populations. This protective effect was observed across different types of air pollutant exposure and may be more pronounced in highly polluted environments.

-

Tables 5 and 6 present the results of the mediation analysis, which indicate that the direct protective effect of green space on hearing thresholds was statistically significant, but the indirect effects (mediation effects) of pollutants were not statistically significant. This suggests that the hearing protection mechanism of green space exposure for noise-exposed populations may primarily be achieved through non-air pollution pathways (such as stress relief and noise shielding), rather than through improvements in local air quality. Future research should explore the mechanisms of other potential mediating factors (such as social cohesion, physical activity, etc.).

-

Interaction analysis revealed that under low pollutant exposure conditions, high NDVI exhibited a significant protective effect, with this protective effect being particularly pronounced in high PM10 environments (Tables S2–S3, in supplementary materials). In high NO2 environments, high NDVI maintained its protective effect. For PM2.5, high NDVI could reverse the harmful effects of high pollution. We found that the left ear was more sensitive to the interaction with PM2.5. Therefore, exposure to green space in high-pollution environments partially offsets the hearing damage effects of pollutants. This interaction exhibits pollutant specificity, with the strongest regulatory effect observed for particulate matter (PM2.5/PM10), suggesting that urban green space planning should prioritize high-pollution areas such as industrial zones.

Sensitivity analyses

In the sensitivity analyses, we used NDVI、SAVI with 500 m and 1000 m buffers as a proxy for greenness exposure. The results of Model 2, which adjusts for all covariates, are consistent with the results of the main analysis. The significant associations between greenness and the risk of hearing threshold occurrence were not altered by the use of 500 m and 1000 m buffers. Using EVI as an indicator of green space exposure did not alter the significant correlation between green space exposure and bilateral hearing thresholds. Therefore, the association between green space exposure and the risk of hearing threshold occurrence is robust (Tables S4–S6, in supplementary materials).

Discussion

Prior research has examined the relationship between health outcomes and the level of greenness surrounding residences. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to look into the relationship between an occupational population’s risk of incidence and exposure to visible greenness around the workplace, as well as the potential mechanisms underlying these relationships. We found that greenness (NDVI and SAVI) was negatively correlated with hearing thresholds and that the exposure-response curves for both flattened out before decreasing. In addition, the mediation analysis results show that the hearing protection mechanism of green space may be achieved mainly through non-air pollution pathways (such as stress relief and sound barriers), rather than relying on improving local air quality.

There is limited and heterogeneous evidence on the association between greenness and hearing thresholds. We observed that long-term exposure to higher levels of greenness was associated with a reduced risk of hearing threshold occurrence, which may be related to the fact that green space improve human health by reducing noise. Existing research suggests possible pathways through which greenery affects health: A study on the association between changes in greenery and the incidence of cerebral hemorrhage35, as well as long-term exposure to road traffic noise, indicates that increased greenery can reduce the incidence of cerebral hemorrhage, while long-term exposure to road traffic noise increases the risk. More directly, a study conducted in Canada on early childhood development showed that the total score of the Early Development Instrument (EDI) is positively correlated with lifelong green living experiences, and this association is partly mediated by lower levels of particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and noise exposure36. This implies that greenness may have an indirect impact on children’s development by enhancing air quality and lowering noise pollution, in addition to directly promoting improved developmental outcomes. However, this is inconsistent with our research findings, and we speculate that it may be related to the selection of research subjects.

The mechanisms underlying the association between greenness exposure and hearing thresholds are unknown, but several possible pathways have been proposed. First, green space can reduce exposure to environmental risk factors37,38,39, such as air pollutants and heat waves, which are strongly negatively correlated with hearing thresholds40,41,42,43; Secondly, prolonged noise exposure can lead to overstimulation of inner ear hair cells, which can cause structural damage and in turn lead to attenuation and distortion of auditory stimuli, which is one of the main causes of hearing loss. And greenness is effective in absorbing noise42. Our research was among the pioneering efforts to explore the exposure - response relationship between the degree of exposure to greenness and hearing thresholds. We found that the exposure-response curves for both metrics initially reached a stable state and then started to decline. This discovery implies that enhancing the level of greenness exposure in the workplace could be a worthwhile factor to take into account when aiming to lower the risk of experiencing changes in hearing thresholds.

The results of the stratified analysis were heterogeneous. The relationship between pollutant concentration and greenness and hearing thresholds is more complex, showing differences at different pollutant and concentration levels. The results suggest that the effect of greenery on hearing thresholds may be more significant at higher concentrations of pollutants. This may be because high concentrations of pollutants may have a direct negative effect on hearing, while the greenness of the vegetation may provide some degree of protection. Vegetation significantly reduces exposure to particulate matter through leaf retention, but at high concentrations, hearing damage accumulates linearly, partially offsetting the protective effect of greening. NO2 mainly originates from traffic and combustion emissions, and its distribution exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity; NO2 concentrations are high near roads and decrease with distance. Vegetation may reduce NO2 exposure through pollutant adsorption or physical barriers. However, dense canopy cover prolongs the retention time of pollutants, leading to increased hearing risks. In summary, the role of vegetation in protecting hearing in highly polluted environments is essentially a dynamic trade-off between environmental benefits and exposure risks.

In the mediation analyses, we have not yet identified any association between exposure to air pollutants in green environments and hearing thresholds. We speculate that there may be confounding factors not included in the study that simultaneously affect the green environment-pollutant-hearing threshold chain, and the potential mechanisms involved require further investigation. The interaction of greenness and air pollution on hearing thresholds may imply underlying biological mechanisms. In our study, we found a sustained negative interaction between greenness and air pollution on the risk of hearing threshold occurrence. This may be due to the fact that the surfaces of green plants, such as leaves, have a large specific surface area, which can adsorb airborne pollutants such as particulate matter (e.g., PM2.5, PM10), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and other pollutants, and reduce their concentration in the air44. It reduces the adverse effects on the auditory system such as systemic inflammatory response triggered by air pollution.

As far as we know, no previous study has explored the relationship between exposure to workplace greenness and hearing thresholds, along with the mediating effect of air pollutant exposure in this relationship. These new research directions offer precious perspectives on the intricate connections among environmental factors and hearing thresholds. And we focused this study on a large occupational population. Furthermore, a satellite-based vegetation index which has been extensively used in earlier research was the basis for the exposure measurements. However, there are several limitations to our study. First, a causal relationship between exposure and outcome could not be established due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. Thus, additional longitudinal research is required. Second, some potential confounders (such as socioeconomic position, education level, and other behaviors) were not taken into account because of the lack of data, which may bias the risk estimates. Third, Considering workplace clustering, we applied cluster-robust standard errors (CRSE) to correct for standard error bias, but did not decompose random effects at the workplace level. Future studies should validate multilevel models in larger sample frameworks. Fourth, Our data lacks noise exposure statistics, hindering a better study of the influence of greenness and noise on occupational populations. Fifth, it is important to note that due to the lack of residential address data, we only considered greenness in the workplace and not in the residential environment. Both residential and workplace greenness exposure should be considered in future studies. In addition, this study acknowledges another potential limitation: the geographical location of the workplace may introduce selection bias or rural-urban confounding factors. Workplaces set in rural environments typically have higher levels of green exposure, while their types of work and noise exposure characteristics (such as being dominated by natural noise) may also differ systematically from urban environments (which are mainly dominated by traffic noise). Although this study has controlled for relevant covariates as much as possible in the analysis, this potential confounding effect cannot be completely ruled out. It should be emphasized that this limitation does not challenge the validity of the internal results of this study, but it does caution us to be careful when extrapolating conclusions to workplaces in different geographic environments. Future research should intentionally recruit workplaces from various rural and urban backgrounds to further investigate the associations.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that increased density of green vegetation outside the workplace may be protective against the risk of hearing threshold occurrence in occupationally exposed populations. However, no mediating mechanisms for air pollutants have been identified in this association. Our research offers evidence regarding the possible advantages of green spaces for hearing thresholds. This finding can guide the formulation of strategies aimed at influencing the outcomes of hearing thresholds through environmental interventions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions on data disclosure but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sancini, A. et al. Can noise cause high blood pressure? Occupational risk in paper industry. Clin. Ter. 165, e304 (2014).

Skogstad, M. et al. Systematic review of the cardiovascular effects of occupational noise. Occup. Med.-Oxford. 66, 500 (2016).

Munzel, T. et al. Environmental stressors and cardio-metabolic disease: part I-epidemiologic evidence supporting a role for noise and air pollution and effects of mitigation strategies. Eur. Heart J. 38, 550 (2017).

Munzel, T. et al. Environmental stressors and cardio-metabolic disease: part II-mechanistic insights. Eur. Heart J. 38, 557 (2017).

Kacem, I. et al. Occupational noise exposure and diabetes risk. J. Environ. Public. Health. 2021, 1804616 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Relationship between occupational noise exposure and the risk factors of cardiovascular disease in china: A meta-analysis. Medicine 97, e11720 (2018).

Nassiri, P. et al. The combined effect of industrial noise type, level and frequency characteristics on hand motor skills: A lab trial study. Work 68, 711 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Associations between occupational noise exposure, aging, and gender and hearing loss: A cross-sectional study in China. Audiol. Res. 15, (2025).

Sayapathi, B. S. et al. The effectiveness of applying different permissible exposure limits in preserving the hearing threshold level: a systematic review. J. Occup. Health. 56, 1 (2014).

Pickard, B. R. et al. Mehaffey, M., Jackson, L. E. & Neale, A., EnviroAtlas: A new geospatial tool to foster ecosystem services science and resource management. Ecosyst. Serv. 14, 45 (2015).

Kondo, M. C. et al. Urban green space and its impact on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 15 (2018).

Pereira, G. et al. The association between neighborhood greenness and cardiovascular disease: an observational study. BMC Public. Health. 12, 466 (2012).

Donovan, G. H. et al. The relationship between trees and human health: evidence from the spread of the Emerald Ash borer. Am. J. Prev. Med. 44, 139 (2013).

Seo, S. et al. Association between urban green space and the risk of cardiovascular disease: A longitudinal study in seven Korean metropolitan areas. Environ. Int. 125, 51 (2019).

Alcock, I. et al. Longitudinal effects on mental health of moving to greener and less green urban areas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1247 (2014).

Engemann, K. et al. Associations between growing up in natural environments and subsequent psychiatric disorders in Denmark. ENVIRON. RES. 188, 109788 (2020).

Engemann, K. et al. Association between childhood green Space, genetic Liability, and the incidence of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 46, 1629 (2020).

Engemann, K. et al. A life course approach to Understanding associations between natural environments and mental well-being for the Danish blood donor cohort. Health Place. 72, 102678 (2021).

Gascon, M. et al. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 12, 4354 (2015).

Rook, G. A. Regulation of the immune system by biodiversity from the natural environment: an ecosystem service essential to health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 18360 (2013).

Egorov, A. I. et al. Vegetated land cover near residence is associated with reduced allostatic load and improved biomarkers of neuroendocrine, metabolic and immune functions. Environ. Res. 158, 508 (2017).

Hystad, P. et al. Residential greenness and birth outcomes: evaluating the influence of spatially correlated built-environment factors. Environ. Health Persp. 122, 1095 (2014).

Markevych, I. et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ. Res. 158, 301 (2017).

James, P. et al. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2, 131 (2015).

Ju, M. J. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollutants and hearing loss in Korean adults. Sci. Total Environ. 820, 153124 (2022).

de Keijzer, C. et al. Long-term exposure to greenspace and metabolic syndrome: A Whitehall II study. Environ. Pollut.. 255, 113231 (2019).

Yang, B. Y. et al. Association between residential greenness and metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults. Environ. Int. 135, 105388 (2020).

Yang, B. Y. et al. Greenspace and human health: an umbrella review. Innov. (Camb). 2, 100164 (2021).

Barnett, A. et al. The neighbourhood environment and profiles of the metabolic syndrome. Environ. Health-Glob. 21, 80 (2022).

Pan, J. et al. Beneficial associations between outdoor visible greenness at the workplace and metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults. Environ. Int. 183, 108327 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Association between residential greenness and diabesity among adults in Southwestern china: the role of physical activity and ambient air pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 303, 118948 (2025).

Li, D. et al. Greenness exposure mitigate PM2.5-Associated congenital heart defects in china: A mediation analysis of chemical composition and Seasonal-Spatial vulnerability. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 269, 114624 (2025).

Knol, M. J. et al. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int. J. Epidemiol. 41, 514 (2012).

Huang, Y. T. et al. Causal mediation analysis of survival outcome with multiple mediators. Epidemiology. 28, 370 (2017).

Gu, T. et al. Modification of green space on the associations between long-term road traffic noise exposure and incident intracerebral hemorrhage: A prospective cohort study. Environ. Res. 231, 116189 (2023).

Jarvis, I. et al. Assessing the association between lifetime exposure to greenspace and early childhood development and the mediation effects of air pollution and noise in Canada: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 5, e709 (2021).

Hirabayashi, S. et al. Comprehensive National database of tree effects on air quality and human health in the united States. Environ. Pollut. 215, 48 (2016).

Denpetkul, T. et al. Daily ambient temperature and mortality in thailand: estimated effects, attributable risks, and effect modifications by greenness. Sci. Total Environ. 791, 148373 (2021).

Nemitz, E. et al. Potential and limitation of air pollution mitigation by vegetation and uncertainties of deposition-based evaluations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 378, 20190320 (2020).

Chang, K. H. et al. Increased risk of sensorineural hearing loss as a result of exposure to air pollution. Int J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 17 (2020).

Tsai, S. C. et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and the risk of developing sudden sensorineural hearing loss. J. Transl. Med. 19, 424 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Exposure to green space, nighttime light, air pollution, and noise and cardiovascular disease risk: A prospective cohort study. Environ. Pollut. 367, 125603 (2024).

Wu, Q. et al. Association of ambient air pollution and Air Quality Index with risk of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 14, e85884 (2024).

Allaouat, S. et al. Long-term exposures to low concentrations of source-specific air pollution, road-traffic noise, and systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease biomarkers. Environ. Res. 262, 119846 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Xiaolin Zhang, Department of Epidemiology and Statistics, School of Public Health, Hebei Medical University, Hebei Province Key Laboratory of Environment and Human Health, for their invaluable guidance and support throughout this research. We also extend our thanks to Lina Yan for providing the necessary resources. Special thanks to our colleagues and collaborators for their insightful feedback and assistance. We also extend our thanks to Jianghong Chen for providing the necessary resources. Special thanks to our colleagues and collaborators for their insightful feedback and assistance. Finally, we are deeply grateful to our families for their unwavering encouragement and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L.: Formal analysis, investigation, software, writing-original draft. S.Y.: Formal analysis, investigation, funding acquisition, software, writing-review and editing. X.L.: Formal analysis, data curation, writing-review and editing. Q.G.: Writing-review and editing. Z.Z.: Formal analysis, investigation, software. X.G.: Data curation. J.Z.: Data curation. L.Z.: Writing-review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hebei Medical University (Approval No.:2024010). The study will strictly adhere to ethical principles and participant protection requirements. All participant data will be anonymized to ensure personal privacy. Prior to the study, all participants will be provided with a detailed explanation of the study content and informed consent will be obtained. During the study, data security and confidentiality will be ensured.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Yan, S., Li, X. et al. Effect of green space in the workplace on hearing thresholds in noise exposed population. Sci Rep 15, 40796 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24661-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24661-w