Abstract

Improved antimicrobial medication or treatments are solutions that need to be combined to limit the impact of antibiotic resistance. Plants have historically been the source of many effective medicines. Zanthoxylum caribaeum is typically found in tropical regions and known for its wide range of plant metabolites that can be attributed to antibacterial activity. The aim of this study was to identify the metabolites potentially involved in the antibacterial activity of Z. caribaeum against resistant bacteria. The antibacterial effect of dried microwave-treated aqueous extracts of Z. caribaeum was tested in vitro against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) confirmed the inhibitory effect observed by the disc method. This showed that Z. caribaeum had a more pronounced effect on methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) at a high concentration with a MIC value of 1.6 × 104 µg/mL, reflecting a weak activity. In parallel, this study provided a global characterization of Z. caribaeum aqueous extract by GC×GC-TOFMS. The 24 most abundant compounds tentatively identified in the derivatized dried aqueous extract of Z. caribaeum, such as 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol and 1-monopalmitin, are known precursor molecules for important biological functions and proteins. In addition, the low dose inhibitory effect of Z. caribaeum aqueous extract makes it a candidate for phytochemical isolation of these molecules and improvement of their antibacterial activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria poses a significant challenge to global health. It is estimated that approximately 700,000 people currently die each year from antimicrobial resistance (AMR) infections, and this number is projected to reach 10 million annually by the year 2050 1. Exploring alternative treatment strategies has become a necessity2. Historically, plants have been the source of many effective medicines3. Today, an estimated 80% of people worldwide use traditional herbal medicines4, they are the first line of defense against disease for tens of millions of people. However, traditional uses of most medicinal taxa have not been evaluated clinically5. In parallel, only 16% of plants thought to have therapeutic value have been tested for biological activity6.

Plants are a promising source of natural products for the identification of bioactive compounds7,8. Plant diversity provides numerous phytochemicals and traditional medicine, particularly in the Caribbean islands, has long utilized various plant extracts for their medicinal properties including anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antimicrobial properties9. The great diversity of flora in the Caribbean10 could provide novel phytochemicals with therapeutic potential to counter the rise in bacterial resistance to antibiotics and preserve antibiotics still active today. Among these, the genus Zanthoxylum has demonstrated several bioactive properties, including, among others, antiparasitic11,12 and antifungal13,14 properties. Zanthoxylum caribaeum Lam. (Fig. 1), a plant in the Rutaceae family native to the Caribbean, has demonstrated acaricidal15 and antibacterial properties, but its antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant strains, remains to be tested.

The aim of this work was to test the antibacterial activity of Z. caribaeum extracts, and to identify metabolites with an effect on resistant bacteria.

Results

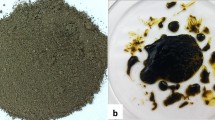

The antibacterial activity of the aqueous extract of Z. caribaeum against several bacteria is presented in Table 1. The water solvent control showed no detectable inhibition. The results obtained using the disk inhibition method showed an effect of Z. caribaeum on most of the bacterial species tested (5 out of 9). Figure 2 shows images of the results of the disk diffusion assay for the Z. caribaeum aqueous extract against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli isolates.

For more precise antimicrobial activity estimation, the MIC was determined. The solvent controls exhibited no antibacterial activity. The MIC determination confirmed the inhibitory effect observed by the disc method and showed a more pronounced inhibitory effect of Z. caribaeum on S. aureus SA024 and S. aureus ATCC25923 (1.6 × 104 µg/mL and 3.1 × 104µg/mL, respectively) than on the other strains (MIC ≥ 1.25 × 105µg/mL). However, these MIC values are significantly higher than those of the standard antibiotic kanamycin (20 µg/mL) (Table 1).

Inhibitory diameters are summarized as mean ± standard deviation (sd). MIC: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, ESBL: extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

As Z. caribaeum was strongly active against S. aureus, to complete the single-point MIC determination, further analyses of the dose-effect were undertaken. Figure 3 presents the sigmoidal dose-response curve of the Z. caribaeum aqueous extract against MRSA S. aureus, SA024. This model explains the concentration-dependent inhibitory effect of Z. caribaeum on MRSA S. aureus SA024 growth (R2 = 0.9838). The slope of the curve (p = 2.542) indicates that bacterial target inhibition will increase markedly as the concentration of the extract increases. The MIC of 1.6 × 104 µg/mL corresponds to the lowest concentration inducing ≥ 88% inhibition.

Dose-dependent effect of Z. caribaeum on methicillin-resistant (MRSA) Staphylococcus aureus, SA024. The sigmoidal dose-response curve is based on bacterial growth measurements and shows the inhibitory percentage of MRSA S. aureus (SA024) after 20 h of incubation at different concentrations of the Z. caribaeum aqueous extract.

The MIC of Z. caribaeum aqueous extract against SA024S. aureus was determined to be 1.6 × 104 µg/mL (1× MIC) (Table 1; Fig. 3). All reported fractional concentrations (e.g., 1/2× MIC, 1/4× MIC, 1/8× MIC) were calculated relative to this MIC value. For example, 8.0 × 103 µg/mL corresponds to 1/2× MIC, and 4.0 × 103 µg/mL to 1/4× MIC. These values have been consistently labeled throughout the figures and discussion. Figure 4 shows the kinetic growth curves for Z. caribaeum aqueous extracts at various concentrations. The untreated control, representing maximal S. aureus proliferation, exhibited robust growth. At a concentration of 1/8× MIC of Z. caribaeum, S. aureus growth remained comparable to that of the untreated control, indicating minimal inhibitory effect at this dilution. Conversely, concentrations of 1/4× MIC resulted in a flatter growth curve, achieving approximately 40% inhibition of S. aureus growth (Fig. 3).

Regardless of the concentration of Z. caribaeum extract tested, the growth of susceptible and multidrug resistant S. aureus strains was comparable (Fig. 5). This result showed a similar effect of Z. caribaeum on susceptible and resistant strains of S. aureus. However, the growth of S. aureus at 1/2× MIC of Z. caribaeum is lower than that of S. aureus not treated with Z. caribaeum (Fig. 5). This result indicates that aqueous extract of Z. caribaeum was active against wild type and multidrug resistant S. aureus with MIC above 1.6 × 104 µg/mL corresponding to 1/2× MIC of S. aureus wild type.

Z. caribaeum inhibitory activity against methicillin-resistant (MRSA) Staphylococcus aureus. The figure shows the mean Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values of triplicates after 20 h of incubation. The error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent assays. Staphylococcus aureusSA024 is a methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strain.

A dried aqueous extract of Z. caribaeum was derivatized for analysis via GC×GC. The resulting total ion chromatogram (TIC) is presented in Fig. 6. A total of 389 peaks were detected. Of these, 24 compounds were tentatively identified based on Metabolomic Standard Initiative (MSI) levels 2 and 316 and were assigned to seven chemical classes: TMS derivatives of amino acids, carboxylic acids, dicarboxylic acids, fatty acids, monoglycerides, phenolics, and sugars (Table 2).

Total ion chromatogram (TIC) of the derivatized dried aqueous extract of Z. caribaeum. The TIC represents the sum of all ion intensities detected at each scan, plotted against the retention time. Peaks represent eluting compounds, with peak area roughly proportional to abundance. TIC includes background noise as well as sample components. A total of 389 peaks unique to Z. caribaeum were detected, the 24 most abundant peaks were assigned to compounds belonging to seven different chemical classes: amino acid, carboxylic acid, dicarboxylic acid, fatty acid, monoglyceride, phenolic, phenolic, and sugar.

These chemical classes were chosen as they were the most abundant peaks in the chromatogram and biologically relevant. Of the seven chemical classes, sugars were the most abundant class in terms of peak area, representing approximately a third of the compounds used (Fig. 7). Within the sugar class, the most predominant compound was myo-inositol. Myo-inositol is the most common stereoisomer of inositol in plants and its derivatives are involved in several different plant functions such as structural integrity, oxidative stress responses and are precursors for various pathways17,18,19. The second most abundant chemical class was amino acids and their derivatives. A notable compound from this class is valine, an essential amino acid synthesized by only plants20,21. Valine is an important building block to create many proteins, including valine-glutamine motifs that can behave as signaling molecules for several pathways responsible for plant growth and responding to abiotic and biotic stressors22,23,24,25. Other notable compounds detected were 1-monopalmitin from the monoglyceride class and 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol from the phenolic class.

Discussion

The aqueous microwave extract of Z. caribaeum was active against most of the bacteria tested, particularly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), where the MIC of 1.6 × 104 µg/mL was below the MIC observed for aqueous plant extracts of Moringa olifera essential oil extract. (2.5 × 104 µg/mL)26. The MIC of Z. caribaeum aqueous extract is significantly higher than that of kanamycin (20 µg/mL). Therefore, while the extract demonstrates antimicrobial activity against MRSA S. aureus27, its efficacy requires substantially high concentrations. Althought there is currently no direct breakpoint established for Z. caribaeum aqueous extract, comparing the MIC values of Z. caribaeum and kanamycin provides insight into its relative antimicrobial potential. The determination of the MICs of purified compounds from Z. caribaeum fractions, are expected to be significantly lower.

This is the first study to investigate the antibacterial activity of aqueous extracts of Z. caribaeum. However, the antibacterial properties of other plant extracts, such as those from S. asoca and A. nilotica, have previously been demonstrated against S. aureus, as well as other bacterial species, including E. coli and P. aeruginosa28. Our findings indicate that Z. caribaeum aqueous extract exhibits limited antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa (inhibitory diameter = 8 mm and MIC = 2.5 × 105 µg/mL). Our observations are supported by reports of limited efficacy of aqueous extracts of Zanthoxylum armatum against P. aeruginosa29. The observed difference in efficacy between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus is likely attributable to fundamental differences in their cell wall structures and inherent resistance mechanisms. Previous works which evaluated plant crude extract found no or little activity against Gram-negative bacteria and potent activity against Gram-positive bacteria30,31. The reduced permeability of the Gram-negative cell envelope prevents the active components of the extract from reaching their intracellular targets effectively. This confirms results showing that aqueous extracts have antibacterial activity32 and contributes to the broader understanding of the genus Zanthoxylum and its potential as a source of antimicrobial agents.

The metabolomic profile of Z. caribaeum aqueous extract highlights several compounds such as phenol, 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol, dodecanoic acid, and 1-monopalmitin have been previously reported to exhibit antibacterial activity, supporting their potential contribution to the observed antimicrobial effects. Notably, phenol and 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol are known for their broad-spectrum antibacterial properties, primarily through disruption of bacterial membranes and oxidative mechanisms33. Dodecanoic acid (lauric acid), a medium-chain fatty acid, has demonstrated strong inhibitory effects against various pathogens including S. aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, likely by compromising cell membrane integrity34. Additionally, monoacylglycerols such as 1-monopalmitin have shown moderate antimicrobial activity, particularly against Gram-positive bacteria, and are believed to act via similar membrane-targeting mechanisms35. While these compounds may not act independently at high potency, their combination effect could contribute to the antibacterial activity of the Z. caribaeum extract. In contrast, common amino acids and sugars, including valine, alanine, and myo-inositol, likely reflect the general metabolic profile of the extract rather than a direct antibacterial function.

Our findings on Z. caribaeum corroborate the relevance of 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (gastrodin) in traditional medicine, showed in the context of Gastrodia elata36 and underscores its potential as a natural antimicrobial agent. In effect, it has been highlighted that gastrodin, exhibit antimicrobial effects against a range of pathogens36, inhibiting the growth of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria37 due to its hydroxyl group ability to disrupt microbial cell membranes38. In addition, gastrodin has been shown to possess antioxidant properties, which may enhance its antimicrobial efficacy37. Although 1-monopalmitin is generally less potent than other monoglycerides, such as monolaurin and monomyristin39,40, this compound can inhibit the growth of specific pathogens suggesting that it may still possess valuable antimicrobial properties under certain conditions41.

Conclusion

Z. caribaeum has broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, and particularly against S. aureus ATCC25923, which is multidrug resistant to common antibiotics. Various compounds tentatively identified in the derivatized dried aqueous extract of Z. caribaeum, such as 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol and 1-monopalmitin are known precursor molecules for important biological functions and proteins. In addition, the low dose inhibitory effect of Z. caribaeum aqueous extract makes it a candidate for phytochemical isolation of these molecules and improvement of their antibacterial activity. This work, complemented by viability and cytotoxicity studies, could pave the way for alternative treatments for infectious diseases caused by S. aureus pathogens that are resistant to standard molecules.

Methods

Plant material

The leaves of Z. caribaeum were collected by one of the authors (GC), with the permission of the owner, in a private garden in Bas-du-Fort, Gosier, Guadeloupe (16.21725° N, 61.52029 W) and were identified by Dr Alain Rousteau (Department of Botany, National University of Asuncion, Asuncion, Paraguay).A voucher specimen (MEF 234) has been deposited at the Herbarium of Chemical Sciences Faculty, San Lorenzo, Paraguay.

Extraction

Zanthoxylum caribaeum Lam. aqueous extract was obtained from leafs and extracted using the microwave-assisted hydrodistillation method. The leaf materials were washed with flowing distilled water, left to air-dry at room temperature and then crushed into a fine powder using a blender. The finely powdered leaves (100 g) were placed in distilled water (2 l) at 80 °C. Hydrodistillation was performed during 3 h in a microvawe apparatus, as described in the European Pharmacopoeia42 the mixture was filtered, concentrated at 40 °C under reduced pressure, freeze-dried, lyophilized and stored at room temperature until use. Aqueous extracts were resuspended to 1 mg/µl stock concentration in sterile water for testing their antibacterial activity in agar diffusion assay.

Bacterial strains

The antibacterial activity of aqueous extracts from Z. caribaeum was tested against nine Gram + and Gram- bacterial strains belonging to six species. Five strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and four strains were from the Pasteur Institute of Guadeloupe collections. The E. coli ATCC 25,922 strain was used as a positive test for the inhibitory effect of Z. caribaeum and the ESBL-resistant E. coli EC335 strain was used as a negative test (Table 1).

Bacterial inhibition assay by the standard disk diffusion method (agar diffusion assay)

The inhibitory effect of aqueous extract samples from Z. caribaeum was determined by the standard disk diffusion inhibition assay. The assay was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar (MH) plates as recommended by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing43. Sterile filter paper disks (Whatman No. 1, 6 mm) were impregnated with aqueous extract from Z. caribaeum (10 µl at 3.3 × 105 µg/mL). A 0.5 McFarland standard bacteria solution was performed on pure fresh cultivated strain and inoculated (100 µl) evenly onto the surface of MH agar plates using a spreader before the disks were positioned on the inoculated agar surface. Water served as the negative control and kanamycin (30 µg) as the antimicrobial reference. All plates were incubated for 24 h at the optimal growth temperature of 37 °C. Antibacterial activity was determined by the presence of a clear zone of inhibition around the disk. Inhibition diameters were measured, and the values were presented as the means of three independent experiments.

Antibacterial minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) measurement

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were determined for all the bacterial strains using the broth microdilution method (Table 1). This method consisted in serial twofold dilutions of a fresh antibiotic working solution in Müller-Hinton (MH) broth, as the diluent, along the length of a 96-well sterile U bottom microtiter plates. Plant extracts susceptibility was tested at 500 to 1 mg/ml concentration ranges. A 0.5 McFarland standard bacteria solution was performed on pure, fresh cultivated strain and diluted at 1/200 in MH broth medium (10 ml). Serial dilutions were inoculated with the suspension within 2 h after preparation. Each plant extract was tested for multiple bacterial strains at once. The first and last wells of every row were used as sterility and growth controls, respectively. Following overnight incubation at 37 °C, under medium shaking, during exposure to plant extract, the absorbance at 630 nm was measured, each 30 min, using ELx808™ absorbance microplate reader (BioTek®, Instruments, Inc., Vermont, USA). The MICs were obtained from at least three independent experiments and correspond to the lowest concentrations of Z. caribaeum that yielded no visible growth of the tested bacterial strains in the in vitro microdilution assay, after 20 h incubation, according to the CLSI definition43. The water negative control should show no growth for the test to be valid. MIC values were averaged to report a final MIC, according to European committee of antimicrobial susceptibility testing (EUCAST) guidelines43. The data were exported in Excel; growth curve were generated by subtracting the blank from each corresponding wells and plotting absorbance values versus time. The inhibitory curve was drawn in GraphPad Prism 10.5.0.

Metabolomic analysis of derivatized dried aqueous Z. caribaeum extracts by GC×GC-TOFMS spectrometry

-

a.

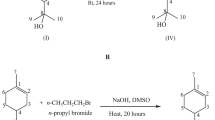

Sample Preparation

A portion of dried aqueous extracts was sent to the University of Alberta and prepared for GC×GC-TOFMS analysis using a two-step methoximation and trimethylsilylation derivatization protocol. An aliquot of 70 mg from the samples was transferred into a 2 ml microcentrifuge tube (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). Extraction was performed with 1 ml of a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of methanol (Optima Grade, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) and chloroform (HPLC-grade, Fisher Scientific). Samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. A 10 µl aliquot of the supernatant was transferred into a 2 ml vial and diluted with 990 µl of the same 1:1 (v/v) methanol solution. From this, 750 µl was aliquoted into a 2 ml clear GC vial (Chromatographic Specialties Inc., Canada) and 50 µl of the internal standard, 413C methylmalonic acid (50 µg/ml, Millipore Sigma, Canada), was added and vortexed. The extract was then dried under nitrogen at 40 °C until completely dry and stored at -80 °C until derivatization.

On the day of derivatization, 100 µl of anhydrous toluene (Millipore-Sigma, Canada) was added to the extracts dried under nitrogen at 50 °C. Then, 50µL of methoxyamine hydrochloride (Fisher Scientific) solution (20 mg/ml in pyridine; HPLC Grade, Fisher Scientific)) was added to the sample, followed by vortexing, then the samples was incubated at 60 °C for 2 h on a heating block. Following a 5 min cooling period, 100 µl of BSTFA + 1% TMCS (Fisher Scientific) was added to the sample, briefly vortexed, then incubated at 60 °C for 1 h. After cooling for 5 min, 70 µl of the derivatized samples plus 70 µl of pyridine (HPLC Grade, Fisher Scientific) were transferred to 300 µl GC vials with fused inserts (Chromatographic Specialties) and stored at 4 °C until being analyzed by GC×GC-TOFMS. All derivatized samples were analyzed within 24 h.

-

b.

GC×GC-TOFMS method

The analysis was performed using a Leco BenchTOF (BT) 4D GC×GC-TOFMS (Leco Instruments, St. Joseph, MI) with a cooled injection System (Gerstel, USA) and a 1 µl liquid injection was performed using a MultiPurpose Sample MPS (Gerstel, USA) in splitless mode into an inlet set at 250 °C. First dimension column was a 60 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm Rxi-5SilMS, and the second dimension a 1.3 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm Rtx-200MS (Chromatographic Specialties, Brockville, ON, Canada). Ultra-pure helium (5.0 grade; Praxair Canada Inc., Edmonton) was used as the carrier gas, with a constant flow rate of 2.0 ml/min. Oven temperature started at 80 °C and was held for 4 min then ramped to 315 °C at 3.5 °C/min, which then was held for 10 min. The secondary oven and modulator temperature offset were constant at + 10 °C and + 15 °C, respectively. The modulation period was 2.5 s. An acquisition delay of 525 s was used, and mass spectra were collected at an acquisition rate of 200 Hz over a mass range between 40 and 800 m/z, with an electron impact energy of -70 ev. The detector had a voltage offset of -200 V relative to the optimized detector voltage. The ion source temperature was 200 °C with a transfer line temperature of 250 °C.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available, for non-commercial purposes, from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

O’Neill, J. A. Antimicrobial resistance: Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 1–20 (2014). https://wellcomecollection.org/works/rdpck35v

Schroeder, M., Brooks, B. D. & Brooks, A. E. The complex relationship between virulence and antibiotic resistance. Genes (Basel) 8, 39 (2017).

Hardy, K. Paleomedicine and the use of plant secondary compounds in the paleolithic and early neolithic. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 28, 60–71 (2019).

Luca, V., De, Salim, V., Atsumi, S. M. & Yu, F. Mining the biodiversity of plants: A revolution in the making. Science. 336, 1658–1661 (2012).

Mawalagedera, S. M. U. P., Callahan, D. L., Gaskett, A. C., Rønsted, N. & Symonds, M. R. E. Combining evolutionary inference and metabolomics to identify plants with medicinal potential. Front Ecol. Evol 7, 267 (2019).

Gupta, P. K. Biomedical applications. In Fundamentals of Nanotoxicology 141–164 (Elsevier, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90399-8.00014-3

Cowan, M. M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 564–582 (1999).

Rossiter, S. E., Fletcher, M. H. & Wuest, W. M. Natural products as platforms to overcome antibiotic resistance. Chem. Rev. 117, 12415–12474 (2017).

Padhye, S., Dandawate, P., Yusufi, M., Ahmad, A. & Sarkar, F. H. Perspectives on medicinal properties of Plumbagin and its analogs. Med. Res. Rev. 32, 1131–1158 (2012).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858 (2000).

Ferreira, M. E. et al. Leishmanicidal activity of two canthin-6-one alkaloids, two major constituents of Zanthoxylum Chiloperone var. Angustifolium. J. Ethnopharmacol. 80, 199–202 (2002).

Ferreira, M. E. et al. Effects of canthin-6-one alkaloids from Zanthoxylum Chiloperone on Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 109, 258–263 (2007).

Diéguez-Hurtado, R. et al. Antifungal activity of some Cuban Zanthoxylum species. Fitoterapia 74, 384–386 (2003).

Cornejo-Garrido, J. et al. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activity, liver profile test, and mutagenic activity of five plants used in traditional Mexican medicine. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 25, 22–28 (2015).

Nogueira, J. et al. Acaricidal properties of the essential oil from Zanthoxylum Caribaeum against rhipicephalus Microplus. J. Med. Entomol. 51, 971–975 (2014).

Sumner, L. W. et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis. Metabolomics 3, 211–221 (2007).

Roberts, A. P. & Mullany, P. Tn916-like genetic elements: A diverse group of modular mobile elements conferring antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 856–871 (2011).

Valluru, R. & Van den Ende, W. Myo-inositol and beyond—Emerging networks under stress. Plant. Sci. 181, 387–400 (2011).

Ghosh Dastidar, K. et al. An insight into the molecular basis of salt tolerance of L-myo-inositol 1-P synthase (PcINO1) from Porteresia coarctata (Roxb.) Tateoka, a halophytic wild rice. Plant. Physiol. 140, 1279–1296 (2006).

Kumar, V. et al. Differential distribution of amino acids in plants. Amino Acids. 49, 821–869 (2017).

Galili, G., Amir, R. & Fernie, A. R. The regulation of essential amino acid synthesis and accumulation in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 67, 153–178 (2016).

Ye, Y. J. et al. Banana fruit VQ motif-containing protein5 represses cold-responsive transcription factor MaWRKY26 involved in the regulation of JA biosynthetic genes. Sci. Rep. 6, 23632 (2016).

Marti, R. et al. Impact of manure fertilization on the abundance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and frequency of detection of antibiotic resistance genes in soil and on vegetables at harvest. Appl. Env Microbiol. 79, 5701–5709 (2013).

Lai, Z. et al. Arabidopsis Sigma factor binding proteins are activators of the WRKY33 transcription factor in plant defense. Plant. Cell. 23, 3824–3841 (2011).

Shan, N. et al. Genome-wide analysis of valine-glutamine motif-containing proteins related to abiotic stress response in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L). BMC Plant. Biol. 21, 492 (2021).

Sharma, P., Wichaphon, J. & Klangpetch, W. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of defatted Moringa Oleifera seed meal extract obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction and application as a natural antimicrobial coating for Raw chicken sausages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 332, 108770 (2020).

Sharma, R. K. & Rana, B. K. Studies on antimicrobial activity and kinetics of inhibition by plant products in India (1990–2016). J. AOAC Int. 101, 948–955 (2018).

Dabur, R. et al. Antimicrobial activity of some Indian medicinal plants. Afr. J. Tradit Complement. Altern. Med. AJTCAM. 4, 313–318 (2007).

Khan, M. F. et al. Antibacterial properties of medicinal plants from Pakistan against multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 815 (2018).

de Paiva, S. R., Figueiredo, M. R., Aragão, T. V. & Kaplan, M. A. C. Antimicrobial activity in vitro of Plumbagin isolated from Plumbago species. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 98, 959–961 (2003).

Bhattacharya, S., Zaman, M. K. & Haldar, P. Antibacterial activity of stem bark and root of Indian Zanthoxylum nitidum. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res 2, 30 (2009).

de Lara, J. G. et al. Chemical composition, antimicrobial, repellent and antioxidant activity of essential oil of Zanthoxylum Caribaeum lam. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 22, 380–390 (2019).

McDonnell, G. & Russell, A. D. Antiseptics and disinfectants: Activity, action, and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 147–179 (1999).

Nakatsuji, T. et al. Antimicrobial property of lauric acid against propionibacterium acnes: Its therapeutic potential for inflammatory acne vulgaris. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 2480–2488 (2009).

Bergsson, G., Arnfinnsson, J., Steingrímsson, O. & Thormar, H. In vitro killing of Candida albicans by fatty acids and monoglycerides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 3209–3212 (2001).

Seok, P. R. et al. The protective effects of Gastrodia Elata Blume extracts on middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 28, 857–864 (2018).

Guo, Y. et al. 4-Hydroxybenzyl alcohol prevents epileptogenesis as well as neuronal damage in amygdaloid kindled seizures. J Neurol. Neurosci 8, 1 (2017).

Luo, L. et al. Anti-oxidative effects of 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol in astrocytes confer protective effects in autocrine and paracrine manners. PLoS One. 12, e0177322 (2017).

Jumina, J. et al. Monomyristin and monopalmitin derivatives: synthesis and evaluation as potential antibacterial and antifungal agents. Molecules https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123141 (2018).

Margata, L., Silalahi, J., Harahap, U., Suryanto, D. & Satria, D. The antibacterial effect of enzymatic hydrolyzed Virgin coconut oil on propionibacterium acne, Bacillus Subtilis, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Rasayan J. Chem. https://doi.org/10.31788/rjc.2019.1225113 (2019).

Sun, C. Q., OʼConnor, C. J. & Roberton, A. M. Antibacterial Actions of Fatty Acids and Monoglycerides against Helicobacter Pylori (Fems Immunology \& Medical Microbiology, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0928-8244(03)00008-7

European Pharmacopoeia: Published under the direction of the Council of Europe (Partial Agreement). European Treaty Series No. 50 & Maisonneuve, S. A. Sainte-Ruffine. Vol. I : p. 401, F.fr. 130.00. Vol. II (1971): pp.xxi + 542, F.fr. 130.00. Vol. III. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 14, 494–495 (1967).

European comittee of antimicrobial susceptibility testing. EUCAST Consultations https://www.eucast.org/publications_and_documents/consultations/

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dany and Philippe Broussier for providing access to the plant biological resources. We would like to thank the students Bibian Garrick and Angel Unimon who prepared the plant extract of Z. caribaeum. Two bacterial strains used in this study, from the Institut Pasteur collection, were collected by students Gaëlle Gruel (PhD) and François-Xavier Mondelice (Master 2 degree).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IA and YD performed plant sampling and aqueous extract preparation. AS implemented bacteriological analysis. AM, SN, and SS conducted the metabolomic analysis, which was supervised by JH. GC, SS, and SF participated in the revision and editing of the manuscript. SF designed the study, supervised the research, and drafted and revised the manuscript. GG, IA, MS, and SN conceptualized substancial revision to the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for their own contributions in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sellin, A., Adou, A.I., Duchaudé, Y. et al. Antibacterial activity and metabolomic profile of Zanthoxylum caribaeum Lam. aqueous extract against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci Rep 15, 40873 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24762-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24762-6