Abstract

While obesity is associated with increased risk of osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), it paradoxically correlates with less structural joint damage in RA. Its impact on distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint OA in RA remains unclear. This study investigated the association between baseline body mass index (BMI) and DIP joint OA incidence and progression in RA patients. We analyzed RA patients with baseline BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatic Diseases registry. DIP joint radiographs were evaluated using the modified Kellgren/Lawrence grading system. The incidence cohort (1031 patients, median follow-up 5.0 years) included those without baseline DIP OA and the progression cohort (1481 patients, median follow-up 4.9 years) included those with DIP OA at baseline. Multivariable logistic regression assessed the association of BMI with incidence or progression, as well as with joint space narrowing (JSN), osteophytes worsening, subchondral sclerosis, and central erosions. Mean baseline BMI was 25.1 kg/m2 (incidence cohort) and 26.0 kg/m2 (progression cohort). At follow-up, 24.3% of patients developed DIP joint OA and 67.9% showed progression. BMI was not significantly associated with incidence (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.98–1.06) or progression (adjusted OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.98–1.04). BMI was similarly unrelated to JSN, osteophyte worsening, subchondral sclerosis, or central erosions. BMI was not associated with DIP joint OA incidence or progression in RA patients. These findings suggest that DIP joint OA in RA may follow a distinct pathophysiological pathway, independent of BMI-related systemic mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Distal hand osteoarthritis (OA) is a common and debilitating joint condition that lacks disease-modifying treatments1. It primarily affects postmenopausal women and is characterized by deformity and structural changes in distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, leading to pain, reduced function, and impaired quality of life2. Established risk factors include female sex, advanced age, genetic predisposition, repetitive hand use3, and metabolic disturbances such as metabolic syndrome and obesity4,5,6.

Obesity is widely recognized as a risk factor for digital OA, particularly in the DIP and PIP joints7,8,9, with mechanisms thought to involve low-grade systemic inflammation and adipokine dysregulation7. Although some recent studies have reported weaker or null associations between body mass index (BMI) and hand OA10,11, earlier systematic reviews continue to support a positive link between obesity and distal hand OA, particularly at the DIP level9. In parallel, metabolic syndrome has been associated with radiographic hand OA and with distal joint pain, but not with involvement of metacarpophalangeal (MCP) or first carpometacarpal (CMC1) joints8.

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), obesity has been shown to increase the risk of RA development12,13 but is paradoxically associated with less structural joint damage despite contributing to higher Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) scores through elevated subjective symptoms (e.g., pain). Patients with RA and obesity often demonstrate slower radiographic progression, particularly in early RA treated with conventional synthetic Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (csDMARDs) or anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents14, though they may exhibit poorer therapeutic response overall14,15. These observations have been attributed to lower adiponectin levels and other metabolic mediators influencing inflammation and bone remodelling14.

The relevance of obesity for OA development in RA remains poorly defined. While prior work has shown that DIP joint OA can progress independently of RA disease activity and serological markers such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA)16, it remains unclear whether obesity plays a meaningful role in this process. Notably, DIP joints are relatively spared from RA-related synovitis and erosive damage compared to MCP, PIP, or CMC joints, making them a more suitable site for assessing osteoarthritic changes in RA populations. Therefore, evaluating OA in DIP joints provides a unique opportunity to study non-inflammatory structural changes within the context of RA.

In this study, we aimed to determine whether baseline BMI, analyzed both continuously and categorically, was associated with the incidence and progression of DIP joint OA in patients with RA. We also examined associations between BMI and specific radiographic features of DIP OA, including joint space narrowing (JSN), osteophytes worsening, subchondral sclerosis, and central erosions.

Patients and methods

Data

We obtained data from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatic Diseases registry (SCQM)17. The SCQM is a national, multicenter registry in Switzerland that longitudinally collects clinical data and radiographic images from patients with RA to support disease monitoring and management. This study used anonymized data from the SCQM registry. All patients provided informed consent for their data to be used for research. The study was reviewed and approved for scientific integrity and appropriate use of SCQM data by the SCQM-affiliated coauthors. In accordance with Swiss human research regulations, no additional ethics approval was required for analyses using fully anonymized data.

Baseline and follow-up data

We analyzed radiographic data of DIP joints from baseline and the latest available follow-up for each patient. Radiographs were collected between November 1983 and October 2014. All available films, including those acquired in the 1980s, were digitized where necessary and rescored. Images that did not meet predefined quality criteria (exposure, positioning, or resolution) were excluded. Details of the scoring system and its reliability are provided in the Outcomes section.

Exposure

The primary exposure variable was baseline BMI (kg/m2), analyzed as a continuous variable in the primary analysis and categorized as Normal weight, Overweight, and Obesity in the sensitivity analysis (details provided below). Weight and height were measured and recorded by clinical staff (not self-reported).

Outcomes

We investigated the following six radiographic outcomes: 1) incidence of DIP joint OA; 2) progression of DIP joint OA; 3) worsening of JSN of DIP joints; 4) worsening of osteophytes of DIP joints; 5) incidence of subchondral sclerosis on DIP joints; and 6) incidence of central erosions on DIP joints. All of our outcomes were binary (i.e., Yes or No). To investigate these radiographic outcomes, we created two cohorts: a ‘DIP joint OA incidence cohort’ and a ‘DIP joint OA progression cohort’.

We assessed the incidence and progression of DIP joint OA based on modified Kellgren-Lawrence (K/L) grades18: 0 = no DIP joint OA; 1 = doubtful DIP joint OA; 2 = mild DIP joint OA; 3 = moderate DIP joint OA; and 4 = severe DIP joint OA18. Our reader demonstrated good intra-reader agreement, evidenced by a weighted kappa exceeding 0.90. This agreement was tested using 200 randomly selected radiographs by rereading the images after two months interval. The reader examined images in a blinded fashion, without access to time or clinical information. A DIP joint was considered to have DIP joint OA if the DIP joint had a K/L grade of ≥ 2. For DIP joint OA, we investigated eight DIP joints per patient (bilateral 2nd to 5th digits). Our reader, using the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) atlas19, provided semi-quantitative scoring for JSN and osteophytes (graded 0–3), and scored the presence of subchondral sclerosis, and central erosions. The reader had a good intra-reader agreement for JSN (kappa = 0.83), osteophytes (kappa = 0.77), subchondral sclerosis (kappa = 0.91), and central erosions (kappa = 0.92).

Our first outcome was the incidence of DIP joint OA, which we defined as a patient having it at the latest follow-up but not at baseline. We investigated this outcome in the 'DIP joint OA incidence cohort,' consisting of DIP joints without DIP joint OA at baseline. Our second outcome of progression of DIP joint OA was investigated in the ‘DIP joint OA progression cohort’, which consisted of DIP joint that had DIP joint OA at baseline. Progression of DIP joint OA was defined as an increase of ≥ 1 in the KL grade in at least one DIP joint between baseline and the latest follow-up. To test the robustness of our findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using a more stringent definition of progression, defined as worsening in at least two DIP joints (rather than one).

The outcomes of worsening of JSN, worsening of osteophytes of DIP joints, incidence of subchondral sclerosis, and incidence of central erosions were investigated in the ‘DIP joint OA incidence cohort’ and the ‘DIP joint OA progression cohort’. The worsening of JSN and worsening of osteophytes of DIP joints were defined as an increase ≥ 1 in the grade of JSN and osteophytes, respectively, in at least one DIP joint between baseline and the latest follow-up. The incidence of subchondral sclerosis, and incidence of central erosions were defined as the presence of subchondral sclerosis and central erosions, respectively, in at least one DIP joint at the latest follow-up while not present at baseline.

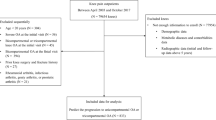

Selection of patients

This analysis was restricted to patients in the SCQM RA registry, which includes only individuals with a clinical diagnosis of RA. To establish the study cohorts, we first excluded patients with follow-up durations of less than two years and those with a baseline BMI in the underweight range (< 18.5 kg/m2) (Fig. 1). The two-year follow-up threshold was chosen to allow sufficient time for potential changes in DIP joint OA to become detectable. Additionally, patients with an underweight BMI were excluded as this may indicate underlying health conditions that could confound the association under investigation. Following these exclusions, we selected patients with at least one DIP joint evaluable on radiographs at both baseline and follow-up. From the remaining 2512 patients, we created the ‘DIP joint OA incidence cohort’ by including only the patients that did not have DIP joint OA at baseline, and the ‘DIP joint OA progression cohort’ by including only the patients with DIP joint OA at baseline (Fig. 1). Median radiographic follow-up was 5.0 years (IQR 3.2–7.3) in the incidence cohort and 4.9 years (IQR 3.2–7.7) in the progression cohort.

Statistical analyses

We used logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between our exposure of BMI our six outcomes (i.e., incidence of DIP joint OA; progression of DIP joint OA; worsening of JSN; worsening of osteophytes; subchondral sclerosis, and incidence of central erosions) over the latest follow-up. Univariable (unadjusted) and multivariable (adjusted) analyses were performed. All of the multivariable analyses were adjusted for sex, and baseline values of the following variables: age, ACPA, RF, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), disease duration since first symptoms, number of tender joints (28 joints), number of swollen joints (28 joints), patient assessed general health visual analog scale (VAS) score, summed percentage of erosive joint surface destruction in 8 MCP joints (to adjust for RA related joint damage), and radiographic observation time. Additionally, adjusted for summed K/L grade in 8 joints at baseline for the outcomes for the progression cohort. These variables were selected because of their association with exposure and outcomes16,20. To evaluate whether the association between BMI and outcomes varied by radiographic observation time, we tested for effect modification by including an interaction term between BMI and radiographic observation time in the multivariable models.

We used R (version 4.3.1). for our analyses. We set our threshold for statistical significance as a two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 in all analyses. Baseline missing values were imputed using multiple imputations by chained equations (m = 50), assuming data were missing at random.

Sensitivity analysis

To complement the primary analysis, which treated BMI as a continuous variable, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using BMI categories. Specifically, BMI was categorized as Healthy Weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and Obesity (≥ 30.0 kg/m2). By comparing the findings from this categorical approach with those of the continuous analysis, we aimed to assess whether categorizing BMI provided distinct insights, thereby enhancing the clinical relevance of our results.

Results

In the DIP joint OA incidence cohort, which included 1,031 patients without DIP joint OA at baseline, 251 individuals (24.3%) developed incident DIP joint OA during follow-up (Table 1). Those who developed incident DIP joint OA were older on average (53.0 ± 9.6 years) compared to those who did not (50.6 ± 10.2 years, p < 0.001). Women were more likely to develop incident DIP joint OA (203 of 251, 80.9%) than men (48 of 251, 19.1%, p = 0.006). Baseline BMI (mean 25.4 ± 4.5 kg/m2 vs. 25.0 ± 4.6 kg/m2, p = 0.330) were similar in those with and without incident DIP joint OA. Patients with incident DIP joint OA had a longer disease duration since first symptoms (median 7.2 vs. 5.1 years, p = 0.012) at baseline, and longer radiographic observation time (median 6.1 vs. 4.6 years, p < 0.001). Other baseline characteristics, including serological markers (ACPA and RF) and tender or swollen joint counts, were comparable between patients with DIP joint OA incidence and no DIP joint OA incidence (Table 1).

In the DIP joint OA progression cohort, which included 1,481 patients with DIP joint OA at baseline, 1006 individuals (67.9%) experienced progression of the disease (Table 2). Patients with progression were of similar age (60.0 ± 9.7 years) to those without progression (61.1 ± 10.6 years, p = 0.051). Women constituted a greater proportion of those with disease progression (786 of 1006, 78.1%) compared to men (220 of 1006, 21.9%, p = 0.046). Baseline BMI (mean 26.0 ± 4.6 kg/m2 vs. 25.8 ± 4.6 kg/m2, p = 0.473) were also similar. Notably, patients with progression had a shorter disease duration since the first symptoms (median 6.5 vs. 8.0 years, p = 0.010) at baseline but longer radiographic observation time (median 5.7 vs. 4.0 years, p < 0.001). Other clinical and radiographic characteristics, such as tender and swollen joint counts and summed erosive joint surface destruction, did not differ significantly (Table 2).

BMI and the incidence of DIP joint OA (DIP joint OA incidence cohort)

There was no evidence of an association between BMI and the odds of incidence of DIP joint OA (Table 3). The odds ratio (OR) for the incidence of DIP joint OA was 1.02 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.98–1.05) in the univariable analysis and was 1.02 (95% CI 0.98–1.06) in the multivariable analysis. Similarly, there was no evidence of an association between BMI and the odds of worsening of JSN, worsening in osteophytes, incidence of sclerosis, and incidence of erosion in either univariable or multivariable analysis (Table 3). None of the interactions between BMI and radiographic observation time were statistically significant (p > 0.05) across any outcomes investigated in the incidence cohort.

BMI and the progression of DIP joint OA (DIP joint OA progress cohort)

There was no evidence of an association between BMI and the odds of progression of DIP joint OA (Table 3). The OR for the progression of DIP joint OA was 1.01 (95% CI 0.98–1.04) in the univariable analysis and was 1.012 (95% CI 0.98–1.04) in the multivariable analysis. Findings were consistent when applying the more stringent progression definition (≥ 2 joints), with no statistically significant associations observed. Similarly, there was no evidence of an association between BMI and the odds of worsening of JSN, worsening in osteophytes, incidence of sclerosis, and incidence of erosion in either univariable or multivariable analysis (Table 3). As in the incidence cohort, no statistically significant interactions were observed between BMI and radiographic observation time for any outcomes investigated in the progression cohort.

Sensitivity analysis

Our sensitivity analysis, in which we used BMI categories, showed no association of BMI categories with any of the outcomes either in univariable or multivariable analysis (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study systematically explored the relationship between BMI and the incidence and progression of DIP joint OA in a large cohort of patients with RA, contributing novel insights to the understanding of OA pathogenesis in non-weight-bearing joints. Notably, we found no association between BMI, whether analyzed as a continuous variable or in categories, and the odds of incidence or progression of DIP joint OA. This includes outcomes related to radiographic structural changes including worsening of JSN, worsening of osteophytes, incidence of subchondral sclerosis, and incidence of central erosions in DIP joints. Furthermore, this lack of association was consistent across different durations of radiographic observation. These findings suggest that the biomechanical and metabolic factors linked to BMI may not substantially influence the risk of DIP joint OA in patients with RA.

In line with our findings, DIP joint OA seems less influenced by BMI, unlike weight-bearing joints such as the knee where elevated BMI associated with increased OA risk, likely through mechanical loading effects21. This distinction is consistent with earlier studies showing that BMI or weight change is associated with knee OA with inconsistent evidence for hip OA, while data specific to DIP OA remain scarce1.

Our findings contribute to the ongoing discussion on the role of inflammation and systemic factors in DIP joint OA pathogenesis in RA. Obesity is known to induce low-grade systemic inflammation that may influence OA in weight-bearing joints22,23, but our results suggest this mechanism may not substantially affect DIP joint OA. We examined ACPA and RF serostatus as RA-specific inflammatory markers. ACPA positivity was statistically less common among patients with incident DIP joint OA, suggesting a modest association; however, this was not observed in the progression cohort and should be interpreted with caution. This observation should not be interpreted as evidence that ACPA-negative status is protective or that ACPA positivity suppresses DIP OA, but rather as a modest, hypothesis-generating signal requiring confirmation in independent cohorts. No significant differences were observed for RF or other RA markers. These findings extend our prior work16, which reported that DIP joint OA progression in RA occurred independently of disease activity or serological status. Although that study16 did not evaluate BMI directly, our current results complement its conclusions by showing no association between BMI and DIP joint OA incidence or progression. Taken together, the absence of associations with BMI or inflammatory markers supports the hypothesis that DIP joint OA in RA may be driven primarily by local or joint-intrinsic mechanisms, rather than by systemic metabolic or inflammatory processes. However, local biomechanical consequences of RA, such as structural damage and deformities at the MCP or PIP joints, may alter hand biomechanics and shift loading patterns distally, potentially predisposing DIP joints to secondary osteoarthritic changes.

The absence of a BMI–DIP joint OA association highlights the importance of distinguishing DIP joint OA pathogenesis from that of weight-bearing joints like the knee when making clinical recommendations. While weight loss in patients with elevated BMI remains a critical intervention for knee OA management due to its biomechanical benefits24,25, such recommendations may not be directly applicable to patients with isolated DIP joint OA. In cases of DIP joint OA, interventions targeting mechanical stress (e.g., ergonomic tools to reduce hand strain) may be more relevant than systemic strategies aimed at reducing adiposity.

Obesity has been paradoxically associated with reduced radiographic joint damage in RA despite higher subjective disease activity scores, a finding thought to involve adipokine-mediated effects on bone remodelling14. Our study did not find any association between BMI and DIP OA, which aligns with the notion that the effects of obesity on joint damage may differ across joint sites. However, our data do not suggest that elevated BMI has a beneficial effect on bone, but rather indicate an absence of association. Whether metabolic mediators such as adipokines contribute to DIP joint OA pathogenesis remains uncertain and warrants further investigation.

This study has several strengths, including a large sample size, detailed radiographic assessments, and multivariable analyses adjusting for potential confounders. Sensitivity analyses using BMI categories further strengthen the results. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cohort was predominantly composed of older White women, limiting the generalizability of our findings to younger, male, or more diverse populations. Second, although follow-up period was comparable to prior studies, it may not fully capture the slow progression of DIP joint OA in some individuals. Third, we lacked data on other metabolic or hormonal factors (e.g. lipid profiles, insulin resistance, post-menopausal changes), which could contribute to DIP joint OA pathogenesis and may partly explain the higher incidence observed in women. Fourth, information on hand dominance, occupational workload, and hand use was unavailable, preventing analyses of mechanical stress on DIP joint OA. Fifth, potential effects of biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs (b/tsDMARDs) on bone remodelling, and thus on the BMI-DIP joint OA relationship, were not assessed. Sixth, while BMI is widely used as a proxy for body composition, it does not distinguish between adiposity and lean mass, which may have divergent effects on DIP joint OA risk. Seventh, because our analyses were restricted to DIP joints, the findings cannot be extrapolated to other hand sites (e.g., PIP or CMC), where RA damage complicates evaluation and the potential role of BMI may differ. Eighth, we modelled BMI and RA disease activity at baseline only; longitudinal changes in BMI or inflammation during follow-up could not be incorporated due to data structure. Lastly, while our study was powered to detect moderate effects (e.g., OR ≥ 1.15), it may have been underpowered to detect small associations, particularly for rare outcomes such as central erosions. As with all observational studies, causality cannot be inferred. Future research should examine the interplay between systemic metabolic and genetic factors in DIP joint OA, and advanced imaging modalities such as MRI could help clarify the role of local inflammation and microstructural changes.

In conclusion, our study found no association between BMI and either the incidence or progression of DIP joint OA in RA patients. These findings suggest that BMI-related biomechanical and metabolic factors may have a limited or non-detectable role in DIP joint OA pathogenesis in RA patients. This underscores the need for DIP joint-specific approaches in OA management and highlights the distinct nature of DIP joint OA compared to weight-bearing joint OA, such as the knee.

Data availability

Data are derived from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatic Diseases (SCQM) registry and are not publicly available due to contractual and regulatory restrictions. Access may be granted upon formal request to the SCQM Foundation, which requires collaboration with a contributing Swiss rheumatologist, ethics approval or waiver, and a data-sharing agreement.

References

Salis, Z. et al. Association of weight loss and weight gain with structural defects and pain in hand osteoarthritis: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res. 76(5), 652–663 (2024).

Kloppenburg, M. & Kwok, W. Y. Hand osteoarthritis–a heterogeneous disorder. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 8(1), 22–31 (2011).

Plotz, B. et al. Current epidemiology and risk factors for the development of hand osteoarthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 23(8), 61 (2021).

Frey, N. et al. Type II diabetes mellitus and incident osteoarthritis of the hand: A population-based case-control analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 24(9), 1535–1540 (2016).

Frey, N. et al. Hyperlipidaemia and incident osteoarthritis of the hand: A population-based case-control study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 25(7), 1040–1045 (2017).

Burkard, T. et al. Risk of incident osteoarthritis of the hand in statin initiators: A sequential cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 70(12), 1795–1805 (2018).

Gløersen, M. et al. Associations of Body mass index with pain and the mediating role of inflammatory biomarkers in people with hand osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 74(5), 810–817 (2022).

Mohajer, B. et al. Metabolic syndrome and osteoarthritis distribution in the hand joints: A propensity score matching analysis from the osteoarthritis initiative. J. Rheumatol. 48(10), 1608–1615 (2021).

Yusuf, E. et al. Association between weight or body mass index and hand osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69(4), 761–765 (2010).

Magnusson, K. et al. No strong relationship between body mass index and clinical hand osteoarthritis: Results from a population-based case-control study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 43(5), 409–415 (2014).

Eaton, C. B. et al. Prevalence, incidence, and progression of radiographic and symptomatic hand osteoarthritis: The osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol. 74(6), 992–1000 (2022).

Ohno, T., Aune, D. & Heath, A. K. Adiposity and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 16006 (2020).

Lu, B. et al. Being overweight or obese and risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis among women: A prospective cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73(11), 1914–1922 (2014).

Daïen, C. I. & Sellam, J. Obesity and inflammatory arthritis: Impact on occurrence, disease characteristics and therapeutic response. RMD Open 1(1), e000012 (2015).

Dubovyk, V. et al. Obesity is a risk factor for poor response to treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis: A NORD-STAR study. RMD Open 10(2), e004227 (2024).

Lechtenboehmer, C. A. et al. Brief report: Influence of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis on radiographic progression of concomitant interphalangeal joint osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 71(1), 43–49 (2019).

Uitz, E. et al. Clinical quality management in rheumatoid arthritis: Putting theory into practice Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 39(5), 542–549 (2000).

Haugen, I. K. et al. Prevalence, incidence and progression of hand osteoarthritis in the general population: The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70(9), 1581–1586 (2011).

Altman, R. D. & Gold, G. E. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15 Suppl A, A1-56 (2007).

Lechtenboehmer, C. A. et al. Influence of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis on radiographic progression of concomitant interphalangeal joint osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 71(1), 43–49 (2019).

Salis, Z. et al. Decrease in body mass index is associated with reduced incidence and progression of the structural defects of knee osteoarthritis: A prospective multi-cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. n/a(n/a).

Sokolove, J. & Lepus, C. M. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Latest findings and interpretations. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 5(2), 77–94 (2013).

Zhai, G. et al. Reduction of leucocyte telomere length in radiographic hand osteoarthritis: A population-based study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65(11), 1444–1448 (2006).

Christensen, R. et al. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66(4), 433–439 (2007).

Messier, S. P. et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: The IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 310(12), 1263–1273 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatic Diseases Foundation (SCQM) for providing unconditional support and maintenance of the SCQM database. A list of rheumatology offices and hospitals that are contributing to the SCQM registries can be found at www.scqm.ch/institution. The authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) minimally for language refinement during manuscript drafting. All scientific content was developed and verified independently by the authors.

Funding

None. No funding source had a role in the design, analyses, interpretation of data, or decision to submit the results in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design and conception: ZS, TH Radiographic labelling: CL Statistical analysis: ZS Drafting the paper: ZS, CD, TH Critical review of the manuscript: ZS, CD, LC, CL, DK, UW, JG, TH Final approval: ZS, CD, LC, CL, DK, UW, JG, TH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ZS owns 50% each of the shares in Zuman International Pty Ltd, which receives royalties and other payments for educational resources and services in adult weight management and research methodology. TH has received speaker fees, travel support or research grants from Eli Lilly, GSK, J&J, BMS, Abbvie, Medac or Pfizer and is board member of Atreon and Vtuls. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salis, Z., Daien, C., Caratsch, L. et al. Association of BMI with radiographic incidence and progression of distal interphalangeal joint osteoarthritis in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Sci Rep 15, 40984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24764-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24764-4