Abstract

This study was undertaken to identify novel thymidylate synthase inhibitors with improved efficacy and selectivity over existing chemotherapeutics. A series of novel 6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)-substituted benzyl-3-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione derivatives were designed, synthesized, and evaluated as potential anticancer agents. Among these, compound 5 h exhibited the most potent cytotoxicity, with IC50 values of 15.70 ± 0.28 µM and 16.50 ± 4.90 µM against SW480 (colorectal cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer) cell lines, respectively, which were comparable to cytometry demonstrated that 5 h significantly induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (up to 62% at 32 µM) and caused marked S-phase cell cycle arrest. Molecular docking and 100-ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations revealed strong and stable interactions of 5 h with the active site of thymidylate synthase (TS), primarily through hydrogen bonding with Asp218 and Met311. MM/GBSA analysis further supported a favorable binding free energy profile. Density functional theory (DFT) studies indicated that 5 h possessed lower Gibbs free energy and higher electron affinity than less active analogs, suggesting enhanced binding and biological stability. binding affinity predictions showed that all derivatives met Lipinski’s criteria and had favorable intestinal absorption exhibited permeability. Collectively, these results highlight 5 h as a promising lead for further preclinical evaluation as a thymidylate synthase inhibitor and anticancer agent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer remains one of the major global health challenges, with its incidence and mortality rates steadily increasing over recent decades. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cancer was responsible for nearly 10 million deaths worldwide in 2020, underscoring the urgent need for more effective and selective therapeutic strategies1,2. Despite substantial progress in systemic treatments—including chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted agents, and immunotherapy—the clinical management of many solid tumors remains suboptimal due to challenges such as drug resistance, severe adverse effects, and poor selectivity3,4,5. These limitations highlight the necessity of developing novel chemotherapeutic agents with enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity.

Nitrogen-containing heterocycles constitute a privileged class of structural motifs in medicinal chemistry and play a central role in anticancer drug discovery due to their broad pharmacological activities and structural versatility6,7,8. Among these, pyrimidine derivatives are particularly significant, as they are essential components of nucleic acids and have served as the foundation for widely used anticancer drugs, including 5-fluorouracil and raltitrexed9,10,11,12. Structural modifications of the pyrimidine ring have yielded derivatives with diverse therapeutic applications, ranging from anticancer to antibacterial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory agents13,14,15,16.

Contemporary drug discovery has increasingly embraced molecular hybridization strategies, in which two or more pharmacophoric moieties are combined into a single molecular scaffold to enhance biological potency and overcome resistance mechanisms17,18. Hybrid molecules incorporating uracil and piperidine units are especially attractive because both fragments exhibit favorable pharmacokinetic properties and cytotoxic potential. Piperidine-based derivatives, in particular, have demonstrated cytostatic effects by inhibiting key enzymes involved in DNA synthesis and cell cycle regulation19,20.

Building upon our previous studies of uracil-based scaffolds with antidiabetic and anticancer activities21,22, we designed and synthesized a novel library of 6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl) benzyl-3-methylpyrimidine-2,4-dione derivatives. Their in vitro cytotoxicity was evaluated against MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) and SW480 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma) cancer cell lines using the MTT assay. To gain mechanistic insights, molecular docking was performed targeting thymidylate synthase (TS), a key enzyme in the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway and a validated target in anticancer therapy21,22. Furthermore, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to assess molecular reactivity and thermodynamic stability, while in silico ADME and drug-likeness analyses were conducted to predict the pharmacokinetic profiles of the synthesized compounds.

The MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) and SW480 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma) cell lines were selected because they are well-established models in anticancer drug discovery and have been extensively used to evaluate pyrimidine-based derivatives. Previous studies have demonstrated that compounds structurally related to our designed hybrids exhibit significant cytotoxic activity against these two cell lines23,24,25. Moreover, both MCF-7 and SW480 have been reported to express elevated levels of thymidylate synthase (TS), making them suitable in vitro models for evaluating TS-targeted anticancer agents26,27. Therefore, these two cell lines provide a relevant and complementary platform to assess the cytotoxic potential and mechanistic rationale of the synthesized derivatives. Thymidylate synthase (TS) was chosen as the primary molecular target due to its pivotal role in de novo DNA synthesis and its clinical validation as the target of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)28,29. Targeting TS not only provides a mechanistic basis for the observed cytotoxic effects but also supports the rationale for developing new analogues with improved selectivity and reduced resistance compared to existing therapies.

This integrated experimental and computational approach was designed to identify novel pyrimidine–piperidine hybrids exhibiting potent antitumor activity and favorable drug-like properties suitable for further preclinical development.

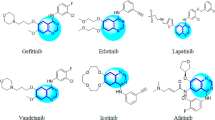

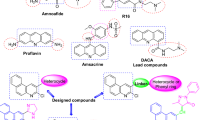

Rational design basis for pyrimidine-piperidine hybrids

The design strategy for the synthesized compounds was guided by the goal of inhibiting thymidylate synthase (TS), a well-established enzyme target in cancer chemotherapy. Considering the proven anticancer activity of pyrimidine derivatives such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), the pyrimidine ring was chosen as the central scaffold to maintain structural relevance to known TS inhibitors11,30. The structural inspiration and design rationale are illustrated in Fig. 1. To modulate the physicochemical and binding properties, a benzyl substituent was introduced at the N1 position of the uracil ring. This hydrophobic moiety was designed to enhance lipophilicity and strengthen interactions with the hydrophobic pockets of the thymidylate synthase (TS) binding site. Systematic variation of substituents on the benzyl ring—including electron-donating versus electron-withdrawing groups and meta versus para orientations—was further explored to assess their effects on electronic distribution, hydrogen bonding patterns, and overall binding affinity31. In addition, a 4-aminopiperidine fragment was incorporated at the C6 position to improve aqueous solubility, introduce additional hydrogen bond donor sites, and enhance polar interactions with residues in the TS active site. Although not derived from any single marketed drug, this modification reflects well-established medicinal chemistry principles, as piperidine groups frequently improve solubility, membrane permeability, and overall pharmacokinetic properties32,33. Halogen substitution, exemplified by the fluorine atom in compound 5 h, was employed as a classical medicinal chemistry strategy to fine-tune lipophilicity, polarity, and electronic properties, aiming to achieve favorable binding interactions and enhanced metabolic stability34,35. In summary, the rational design of these pyrimidine–piperidine hybrids incorporates three complementary features: (i) a pyrimidine scaffold for thymidylate synthase (TS) inhibition, (ii) a benzyl substituent to explore hydrophobic and electronic effects, and (iii) a 4-aminopiperidine group to enhance solubility and hydrogen-bonding potential. Collectively, these structural elements create a novel scaffold with the potential to combine potent TS inhibitory activity and improved drug-like properties.

Experimental section

Chemistry

All chemical material were purchased from Merck Company. Electrothermal 9200 device (Electrothermal, UK) was applied to determine the melting points of the all solid compounds. The chemical structures of the all compounds were characterized via Infrared spectroscopy (VERTEX70 spectrometer), as well as 1HNMR and 13CNMR spectra (400 MHz, VARIAN - INOVA Bruker spectrophotometer in CDCl3 as solvent).

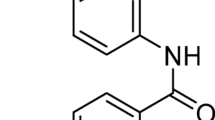

General procedure for the synthesis of 3-methyl-1-(substituted benzyl)−6-4-amino piperidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione derivatives (5a-5j)

To obtain intermediate benzylated uracil, different benzyl bromides (1.2 mmol) (3a-3j) was reacted with 3-Methyl-6-chlorouracil (1 mmol) and then stirred under basic conditions by diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 2 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran as solvent for 6 h. After completion of the reaction, follow by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), the solvent was removed, obtaining the intermediate without further purification (41). Afterwards, the first step products (3a-3j) were combined with 1 mmol of 4-amino piperidine in the presence of a base catalyst (sodium hydrogen carbonate) in in 2-propanol under reflux condition. To purify the final compounds (5a-5j), the thin layer chromatography was applied. The chemical structures of the all synthesized compound (5a-5j) were characterized using 1HNMR, 13CNMR, and IR spectroscopy.

Spectra data

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−1-benzyl-3-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5a)

Yield (59%), m.p:101–103 ℃. yellow powder. IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3448.93 (N-H), 2952.93 (CH aromatic), 1698.40 (C = O), 1650.08 (C = C), 1446.82 (C-O), 1376.64 (C-N). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.25–7.33 (m, 3 H, Phenyl), 7.21–7.22 (m, 2 H, Phenyl), 5.35 (s, 1H, uracil), 5.06 (s, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.30 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 3.16 (d, 2 H, J = 8 Hz, NH2), 3.04 (s, 1H, aliphatic), 2.64–2.77 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.96 (d, 2 H, J = 8 Hz, aliphatic), 1.59–1.62 (m, 1H, aliphatic), 1.27–1.30 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 0.84–0.90 (m, 1H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 169.59, 163.40, 159.94, 152.81, 136.82, 128.2, 127.65, 90.08, 48.10, 48.03, 47.84, 32.81, 27.95. MS m/z (%): 314.2 (63.5), 299.1 (53.17), 223.1 (42.86), 215.0 (4.76), 124.2 (15.08), 91.3 (100), 99.3 (7.0).

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−3-methyl-1-(3-methylbenzyl) pyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5b)

Yield (73%), yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.19 (t, 1H, J = 8 Hz, Phenyl), 7.06 (t, 1H, J = 8 Hz, Phenyl), 6.99–7.02 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 5.35 (s, 1H, uracil), 5.02 (s, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.30 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 3.14–3.17 (m, 2 H, NH2), 2.94–2.99 (m, 1H, aliphatic), 2.84 (s, 2 H, aliphatic), 2.67 (t, 2 H, J = 12 Hz, aliphatic), 3.04 (s, 3 H, CH3-Phenyl), 1.90–1.94 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.48–1.56 (m, 2 H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 167.15, 163.48, 160.15, 152.81, 136.77, 128.57, 128.38, 127.53, 123.82, 89.86, 50.00, 48.07, 47.96, 33.96, 27.93, 21.50. MS m/z (%): 328.1 (72.73), 313.0 (6.76), 229.1 (5.59), 223.1 (27.27), 124.1 (12.59), 105.2 (100), 99.1 (13.98).

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−1-(3-chlorobenzyl)−3-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5c)

Yield (63%), m.p:65–67 ℃. yellow powder. IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3358.38 (N-H), 2943.68 (CH aromatic), 2832.48 (CH aliphatic), 1700.31 (C = O), 1653.22 (C = N), 1439.27 (C-O), 1374.19 (C-N), 768.98 (C-Cl). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.24–7.25 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 7.22 (s, 1H, phenyl), 7.10–7.15 (m, 1H, phenyl), 5.34 (s, 1H, uracil), 5.02 (s, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.30 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 3.10–3.13 (m, 2 H, NH2), 2.86–2.91 (m, 1H, aliphatic), 2.63–2.68 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.87–1.90 (d, 2 H, J = 12 Hz, aliphatic), 1.68 (s, 1H, aliphatic), 1.40–1.48 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 0.83–0.89 (m, 1H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 163.19, 159.88, 152.78, 138.90, 134.54, 127.86, 127.14, 126.40, 125.08, 120.08, 90.15, 50.24, 47.88, 47.41, 34.84, 27.93. MS m/z (%): 348.1 (68.92), 333.2 (4.05), 223.1 (75.68), 124.1 (12.16), 125.0 (100), 99.1 (14.86), 85.2 (18.92).

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−3-methyl-1-(3-nitrobenzyl)pyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5d)

Yield (68%), m.p:113–114 ℃. white powder. IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3437.16 (N-H), 2931.95 (CH aromatic), 1698.861 (C = O), 1649.28 (C = N), 1530.19 (C = C), 1446.53 (C-O), 1352.84 (C-N), 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.17 (s, 2 H, phenyl), 7.54–7.63 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 5.42–5.47 (m, 1H, uracil), 5.15–5.19 (m, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.32–3.33 (m, 2 H, NH2), 3.31 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 2.69–2.89 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 2.01–2.11 (m, 3 H, aliphatic), 1.84–1.92 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.27–1.30 (m, 1H, aliphatic), 0.85–0.92 (m, 1H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 163.21, 159.76, 152.70, 140.87, 129.99, 129.66, 127.13, 125.64, 122.60, 90.22, 53.46, 49.96, 47.60, 33.65, 27.94. MS m/z (%): 359.1 (96.62), 344.1 (5.41), 223.1 (100), 136.1 (68.24), 124.1 (18.24), 99.1 (12.16).

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−3-methyl-1-(3-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)pyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5e)

Yield (63%), yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.14–8.23 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 7.64–7.68 (m, 1H, phenyl), 5.54–5.56 (m, 1H, phenyl), 5.41–5.47 (m, 1H, uracil), 5.15–5.21 (m, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.33 (s, 2 H, NH2), 3.31 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 2.69–2.92 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 2.01–2.11 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.84–1.89 (m, 3 H, aliphatic), 1.27–1.35 (m, 1H, aliphatic), 0.84–0.92 (m, 1H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 170.01, 166.94, 162.15, 160.21, 152.20, 137.50, 128.39, 127.02, 126.45, 88.52, 50.82, 23.20, 22.37, 13.86, 10.75. MS m/z (%): 382.2 (79.86), 283.1 (4.17), 223.1 (94.44), 159.1 (100), 124.2 (20.83), 85.1 (34.72), 69.0 (18.06).

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−3-methyl-1-(4-methylbenzyl) pyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5f)

Yield (78%), m.p: 112–114℃. yellow powder. IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3827.60-3741.21.60.21.60.21 (N-H), 2926.53 (CH aromatic), 1700.91 (C = O), 1653.83 (C = C), 1514.11 (C = N), 1447.98 (C-O), 1376.11 (C-N). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.15 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz, phenyl), 7.71 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz, phenyl), 7.59 (t, 2 H, J = 8 Hz, phenyl), 5.13 (s, 1H, uracil), 5.05 (s, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.82–3.88 (m, 2 H, NH2), 3.12 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 2.72–2.82 (m,3 H, aliphatic), 2.36 (s, 3 H, CH3), 1.59–1.61(m,2 H, aliphatic), 1.22–1.34 (m,1H, aliphatic), 1.14–1.16 (m,1H, aliphatic), 0.95–1.05 (m,1H, aliphatic), 0.81–0.87 (m,1H, aliphatic), 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 178.38, 147.68, 147.10, 139.46, 129.44, 124.48, 123.99, 119.09, 37.12, 34.88, 34.53, 33.93, 22.71, 14.14. MS m/z (%): 328.1 (72.73), 313.0 (6.76), 229.1 (5.59), 223.1 (27.27), 124.1 (12.59), 105.2 (100), 99.1 (13.98).

4-((6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−3-methyl-2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2 H)-yl)methyl)benzonitrile (5 g)

Yield (73%), m.p:144–150 ℃. white powder. IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3433.34 (N-H), 2932.79 (CH aromatic), 2228.78 (CN), 1699.91 (C = O), 1654.31 (C = C), 1444.54 (C-O), 1375.82 (C-N). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.56 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz, phenyl), 7.38 (s, 1H, phenyl), 7.13–7.16 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 5.26 (s, 1H, uracil), 4.58 (s, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.08 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 3.02 (d, 2 H, J = 12 Hz, NH2), 2.59–2.65 (m, 1H, aliphatic), 2.50–2.57 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.65–1.68 (m, 2 H,, aliphatic), 1.20 (t, 3 H, J = 12 Hz, aromatic), 0.81–0.87 (m, 1H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 163.03, 152.74, 142.30, 132.59, 127.53, 118.50, 111.60, 90.48, 50.10, 47.66, 47.63, 34.02, 27.98. MS m/z (%): 339.2 (65.31), 240.1 (6.80), 223.1 (36.39), 116.1 (100), 99.1 (12.93), 85.1 (22.45), 26.1 (12.24).

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−1-(4-fluorobenzyl)−3-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5 h)

Yield (68%), m.p:135–136 ℃. yellow powder. IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3452.78 (N-H), 2925.52 (CH aromatic), 1697.89 (C = O), 1649.83 (C = C), 1510.51 (C-O), 1448.87 (C-N), 1378.82 (C-C), 1220.68 (C-F). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.20–7.28 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 7.00–7.04.00.04 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 5.34–5.39 (m, 1H, uracil), 5.01–5.07 (m, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.30 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 3.16–3.19 (m, 2 H, NH2), 2.65–2.81 (m, 3 H, aliphatic), 2.00–2.12.00.12 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.85–1.90 (m, 1H, aromatic), 1.45–1.61 (m, 1H, aliphatic), 1.27–1.35 (m, 1H, aliphatic), 0.85–0.91 (m, 1H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 163.02, 159.57, 152.74, 142.30, 132.59, 127.48, 118.49, 90.48, 50.15, 47.74, 34.03, 29.69, 27.98. MS m/z (%): 332.1 (14.62), 317.1 (7.69), 233.1 (11.54), 223.2 (76.92), 199.1 (100), 109.1 (38.46), 99.1 (19.23), 85.1 (23.08), 19.1 (10.0).

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−1-(4-chlorobenzyl)−3-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5i)

Yield (73%), m.p:141–146 ℃. yellow powder. IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3436.36 (N-H), 2943.53 (CH aromatic), 1699.82 (C = O), 1654.61 (C = N), 1445.04 (C-O), 1375.40 (C-N), 806.63(C-Cl). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.56 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz, phenyl), 7.38 (s, 1H, phenyl), 7.13–7.17 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 5.38 (s, 1H, uracil), 5.03 (s, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.07 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 3.03 (s, 2 H, NH2), 2.64 (s, 1H, aliphatic), 2.50–2.59 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.64–1.67 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.17–1.23 (m, 3 H, aliphatic), 0.81–0.87 (m, 1H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 163.26, 159.66, 152.76, 135.33, 133.51, 128.90, 128.54, 90.43, 49.80, 47.43, 32.56, 31.73, 27.98. MS m/z (%): 348.1 (68.92), 333.2 (4.05), 223.1 (75.68), 124.1 (12.16), 125.0 (100), 99.1 (14.86), 85.2 (18.92).

6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)−1-(4-bromobenzyl)−3-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione (5j)

Yield (70%), m.p:101–102 ℃. yellow powder. IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3358.32 (N-H), 2943.68 (CH aromatic), 1700.31 (C = O), 1653.22 (C = N), 1439.27 (C-O), 1374.19 (C-N), 770.09 (C-Br). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.76–7.62 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 7.52–7.56 (m, 2 H, phenyl), 5.26 (s, 1H, uracil), 5.08 (s, 2 H, uracil-CH2), 3.08 (s, 3 H, N-CH3), 3.03–3.04 (m, 2 H, NH2), 2.65 (s, 1H, aliphatic), 2.40–2.59 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.65–1.68 (m, 2 H, aliphatic), 1.17–1.23 (m, 3 H, aliphatic), 0.82–0.88 (m, 1H, aliphatic). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 162.62, 160.24, 146.13, 138.25, 134.93, 122.58, 119.84, 89.28, 49.70, 47.87, 47.29, 34.02, 37.75. MS m/z (%): 392.1 (39.29), 313.0 (5.71), 223.1 (66.43), 168.1 (100), 124.0 (7.14), 99.1 (10.71), 85.0 (10), 78.0 (3.57).

Biological evaluations

MTT assay

To assessment the anti-proliferative potentials of the synthesized (5a-5j), the MTT assay was used according on previous studies (2, 41). The cancerous cell lines MCF-7, SW480 and MRC-5 were purchased from the National Cell Bank of Iran (NCBI). Cancer cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA) and for MRC-5, DMEM/Ham’s F12 (Bio Idea, Iran) were used. 5% trypsin/EDTA solution (Gibco, USA) was used to harvest the cells and then seeded at a density of 1 × 10^4 cells per well in 96-well microplates36. Various concentrations of the synthesized compounds and Cisplatin (ranging from 1 to 200 µM) was treated on the culture cells in triplicate manner. After 48 h, the media was changed with 100 µL of a freshly prepared MTT mixture and incubated at 37 °C37. Later than 4 h, 150 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate ELISA reader. Excel 2016 and Curve Expert 1.4 was used to analysis the all data (44).

Apoptosis

Approximately 2 × 10^5 MCF-7 cells were seeded and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day, the cultures were treated with 8, 16, or 32 µM of the compound for 72 h. After the treatment period, apoptosis was analyzed using the Annexin V-FITC staining kit (eBioscience™, Invitrogen). The cells were rinsed twice with 1 mL of 1× binding buffer and then resuspended in 100 µL of the same buffer containing 5 µL of Annexin V conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) for 15 min. The proportion of apoptotic cells was quantified using a BD FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The final apoptosis percentage was calculated by combining the percentages of both early and late apoptotic populations.

Cell cycle

A total of 5 × 10^4 MCF-7 cells were seeded into 24-well plates containing high-glucose DMEM and maintained under standard culture conditions for 16 h. Subsequently, the cells were treated with 8, 16, and 32 µM of the compound for 72 h. At the end of the treatment, the cells were detached using 0.25% trypsin, washed with PBS, and stained with 5 µL of propidium iodide (1 mg/mL) and RNase A (10 mg/mL). Cell cycle distribution was then evaluated using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA). DNA content was analyzed using FlowJo software (version 7.0).

Computational studies

Molecular docking

The 3D structure of Thymidylate synthase (TS) was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 1HVY)38. AutoDock Vina was used to run the molecular docking process. Preliminary preparation of ligands and protein was done base on our previous paper39,40. A grid box measuring 40 × 40 × 40 Å and an exhaustiveness setting of 100 was applied for the docking analysis. Discovery Studio 2016 was employed to visualize the interactions and orientations of the compounds.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

An additional assessment was conducted to examine the interactions of the top-ranked drugs with Human thymidylate synthase (PDB ID: 1HVY) in a dynamic context. MD simulation was performed using the Desmond software. The system used in the molecular dynamics simulation was developed from the docking calculation results41. Utilizing the transferable intermolecular potential with a three-point (TIP3P) solvent model, the simulation was carried out inside an orthorhombic box by applying OPLS force field42. By applying Schrödinger’s System Setup, it was possible to introduce sodium and chloride ions at a concentration of 0.15 M and create equilibrium within the system43. Within the NPT ensemble framework, the simulation was run using the default parameters for 100 nanoseconds. The NPT ensemble kept the number of atoms constant throughout the simulation, and the temperature and pressure remained constant as well44. By using the Nose-Hoover protocol, the system’s temperature was successfully set at 310.15 K (37 °C), and isotropic scaling was used to keep the pressure at 1 atm.

MM/GBSA calculation

The MM/GBSA methodology was used to evaluate binding free energies. For this investigation, the Prime module of the Schrödinger software was utilized. The VSGB solvation model was used in conjunction with the OPLS force field to calculate the energy. Below is the equation that was utilized in these computations:

DFT study

In this study, quantum mechanical (QM) calculations were conducted using density functional theory (DFT) within the Gaussian 09 software, employing a 6–31 + G**(d, p) basis set to optimize the compounds and perform additional analyses. The total internal energy (Etot), enthalpy (H), entropy (S), and Gibbs free energy (G) for each molecule were computed. Frontier molecular orbital calculations were also executed at the same theoretical level (B3LYP/6–31 + G** at T = 298 K). Additionally, the hardness (η) and softness (σ) of the compounds under investigation were assessed based on the energies of the frontier HOMOs and LUMOs, in accordance with Parr and Pearson’s DFT framework and Koopmans’ theorem, which relates ionization potential (I) and electron affinities (EA) to HOMO and LUMO energies through specific equations as follows:

Pharmacokinetic profiles

The physicochemical and pharmacokinetic characteristics, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, were assessed using the SwissADME online tool along with the preADMET online platform (http://preadmet.bmdrc.org/). The physicochemical characteristics of all the synthesized compounds were assessed using the online platform http://www.swissadme.ch/, following the guidelines of Lipinski and Veber.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

Ten novel 3-methyl-6-chloro uracil-4 amino piperidine derivatives were obtained through a two-step process. Firstly, different benzyl bromides (2a-2j) were combined with 3-methyl-6-chlorouracil in tetrahydrofuran (THF) at 40 °C to output the benzylated uracil intermediates (3a-3j). The benzylated uracil was reacted with 4-amino piperidine under a basic reaction system that included sodium hydrogen carbonate under reflux conditions for an overnight period. The representation of the synthetic process (5a-5j) was depicted in Fig. 2.

In 1H-NMR spectra, the significant peak is peak belong to H-5 of uracil moiety which appeared as single or multiple at 5.34–5.47 ppm. Two protons of CH2 observed as singlet at 5.02–5.06 ppm except for 5d-5e and 5 g–5 h. In contrast, the NH2 protons were observed at 3.10–3.33 as doublet or multiple and the peak of C5 of the uracil moiety was seen in the range of 78.23–89.29 ppm.

It should be noted that for compounds 5 d, 5e, 5 g, and 5 h, the benzylic and uracil protons appeared as multiplets rather than singlets. This deviation may be attributed to long-range coupling interactions and conformational effects of the aminopiperidine substituent, which can influence the local electronic environment and splitting patterns observed in the 1HNMR spectra.

Biological activity

MTT assay

The 10-novel pyrimidine-4-amino piperidine derivatives (5a-5j) was introduced to evaluate as cytotoxic agents against two cancerous cell lines. The results are depicted in Fig. 3; Table 1. Cisplatin and 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) were applied as positive controls. Compound 5 h was found as the best derivative with IC50 value of 16.50 ± 4.90 µM and 15.70 ± 0.28 µM against MCF-7 and SW480 cell lines, respectively. Compound 5b exhibited the lowest IC50 value against MCF-7 cells (14.15 µM), but its activity against SW480 cells was comparatively weaker (31.75 µM). In contrast, compound 5 h demonstrated consistently strong cytotoxicity across both cell lines (15.70 µM for SW480 and 16.50 µM for MCF-7), along with superior induction of apoptosis, S-phase cell cycle arrest, and higher computational binding affinity to thymidylate synthase. Therefore, although 5b was the most potent compound against MCF-7 cells alone, 5 h was considered the most promising overall lead compound due to its balanced potency, mechanistic evidence, and favorable predicted pharmacokinetic profile. In contrast, 5b and 5e showed significant anti-proliferative activity with IC50 value in a range of 14.15–17.55 against breast cancer cell line. The tested compounds showed a reduced cytotoxic effect on normal MRC-5 cells compared to the cancer cell lines, indicating a degree of selectivity between malignant and non-malignant cells.

As shown at Table 1, incorporation of halogen substitution at different position of the benzyl ring tend to varied activity, such as, in compound 5c bearing chlorine at meta position of benzyl moiety noted moderate activity and when the chlorine group moved to para position, the activity was significantly improved. In general, the presence of halogen substitution at para position had better effectiveness compared to meta counterpart in order F > Cl > Br (Fig. 2). It is interesting that 3-nitro benzyl substitution did not have good activity, too. Vice versa, electron donating groups such as Methyl and cyano was significantly affected on meta position of benzyl motif compared to para position. In this series, the high activity of compound 5b (3-methyl benzyl) demonstrated that methyl substitution at the meta position significantly improves inhibition. Compound 5f (para- methyl benzyl) showed a great decrease in inhibition compared to the meta derivative. It is worth noting that the compounds with no substituent showed the appropriate activity (5a). In general, electron-donating groups have a better effect when positioned at meta on the benzyl ring, while electron-withdrawing groups perform better activity at para position.

The SAR analysis revealed that both the type and position of substituents strongly influence cytotoxic activity. For example, compound 5b (3-methylbenzyl) exhibited significantly higher activity against MCF-7 cells compared to its para-substituted analogue 5 f. This suggests that a meta-methyl group enhances electron donation and optimizes hydrophobic interactions within the TS binding pocket, whereas para-methyl substitution may reduce favorable binding orientation. Similarly, the 3-chloro (5c) and 4-chloro (5i) derivatives showed differing activities, with the para isomer demonstrating greater potency. This difference may be attributed to electronic distribution effects, as a para-chloro substituent can more effectively stabilize π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding interactions than its meta counterpart. These findings indicate that electron-donating substituents are favored at the meta position, while electron-withdrawing substituents are more beneficial at the para position, consistent with docking analyses and binding energy predictions.

Apoptosis

Flow cytometry analysis using Annexin V-FITC/PI staining demonstrated that the tested compound significantly increased programmed cell death in MCF-7 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). In the control group, only a small percentage of cells (~ 7%) were in early and late apoptosis, indicating high cell viability under normal conditions. Treatment with 8 µM of the compound elevated apoptosis to approximately 35%. This effect was further enhanced at higher concentrations, reaching 48% and 62% at 16 µM and 32 µM, respectively. Detailed analysis revealed a pronounced increase in late apoptosis at higher concentrations, suggesting enhanced cellular damage and activation of cell death pathways. These findings clearly indicate that the compound effectively reduces cancer cell survival by inducing apoptosis. This mechanism aligns with the anticancer properties of apoptosis-inducing agents reported in previous studies, reinforcing the potential of this compound as a therapeutic candidate.

Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis induction by compound 5 h in MCF-7 cells was performed using Annexin V-FITC/PI dual staining. Cells were treated with 0 (control), 8, 16, and 32 µM concentrations of 5 h for 72 h. Representative dot plots illustrate the distribution of viable (Annexin V⁻/PI⁻), early apoptotic (Annexin V⁺/PI⁻), late apoptotic (Annexin V⁺/PI⁺), and necrotic (Annexin V⁻/PI⁺) cells.

Cell cycle

Cell cycle analysis using propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry demonstrated that the compound induced significant cell cycle arrest at the S phase. In the control group, the majority of cells were in the G0/G1 phase (64.89%), with only 18.92% in the S phase, indicating normal cell cycle progression. Treatment with 8, 16, and 32 µM of the compound increased the percentage of cells in the S phase to 45.14%, 51.91%, and 58.48%, respectively (Fig. 5). This increase was accompanied by a marked reduction in the G0/G1 population, indicating a blockade in DNA replication progression. At higher concentrations, the S phase arrest became more pronounced, with a concomitant decrease in the G2/M population. S phase arrest directly contributes to the inhibition of cell proliferation and may also sensitize cells to apoptosis. These results suggest that cell cycle arrest is a key mechanism by which the compound inhibits cancer cell growth, complementing the apoptosis findings.

Cell cycle distribution of MCF-7 cells following treatment with compound 5 h at concentrations of 0, 8, 16, and 32 µM for 72 h was analyzed by PI staining and flow cytometry. Representative histograms demonstrate a dose-dependent accumulation of cells in the S phase, accompanied by a reduction in the G0/G1 and G2/M populations.

Computational studies

Molecular docking study

Molecular docking plays an important role in drug discovery by helping researchers identify potential drug candidates and understand their binding mechanisms and interactions45. For better understanding the biological outputs, we docked all synthesized compounds against the human thymidylate synthase target (PDB ID: 1hvy). To validate the docking protocol, redocking was also done. The Raltitrexed (D16) internal ligand was exactly located in active site of 1hvy, and RMSD of docking was found to be 1.56, which showed the validity of docking. The score binding of all compounds is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Docking binding scores of the synthesized compounds (5a-5j).

As dedicated, all of the ligands had appropriate binding energy compared to internal ligand. The binding interaction of Raltitrexed (D16) was shown in Fig. 6. a π-sulfor and π- π stacking interaction are observed between Met 311, Phe 225 and Phe 80 and the quinazoline and thiazole ring of the Raltitrexed. His 256 and Arg 50 are involved in salt bridge with aliphatic chain of Raltitrexed analogue. For this particular target, the docking scores of the benzyl pyrimidine compounds (exclusively 5a-5c and 5 g) is higher than the binding energy of the internal ligand, which has been confirmed to inhibit thymidylate synthase effectively.

On the other hand, molecular interactions between 5 h, 5f and thymidylate synthase with the best docking scores are illustrated in detail in Fig. 7. Its strength potential of 5 h is probably related to three hydrogen bonding with Asp 218, Met 311 and Tyr 135 within the main pocket 1hvy. The amino acids Phe 91, Trp 109, His 196, Leu 221 and Ile 108 are frequently involved in π interactions with the main part of compound. The compound 5f is interacted with Leu 221, Leu 192 and Met 311 via π stacking interaction (Fig. 7).

MD simulation

Using a 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation, the interactions between the ligands and proteins for compounds 5 g and 5 h with 1HVY were assessed. During the simulations, the protein’s root means square deviation (RMSD) values converged at roughly 1.8 Å for 5 g and 2.8 Å for 5 h, respectively. Following the simulation time, these values demonstrate that the systems have stabilized. Figure 8A displays the interactions between 5 h and protein during a 100ns time span. Glu87, Ile108, and Phe225 are the residues with the highest interaction fraction. The residues exhibit interactions that are typified by water bridges, hydrophobic contacts, and hydrogen bonds. Figure 8A provides a thorough view of the interactions between 1HVY and 5 h during the simulation. Figure 8B shows a graphical representation of the interactions between 5 g and 1HVY during the course of the simulation. Glu87, Ile108, and Asp218 are the residues with the highest interaction fraction. The most important interaction identified during the simulation is hydrogen bonding. With the ligand, Glu87 has formed a water bridge, an ionic connection, and a hydrogen bond. The interaction that was built between Ile108 and Asp218 is a hydrogen bond. It was assessed how the protein’s secondary structure changed after interacting with 5 g and 5 h. The distribution of secondary structural elements (SSE) found during the MD simulation of the 5 h-1HVY and 5 g-1HVY complexes is shown in Fig. 9. This graphic depicts the constant stability of the alpha-helices (shown in red) and beta-strands (shown in blue segments) during the course of the simulation. This result validates the accuracy of the results by confirming that the simulation effectively preserves the proteins’ structural integrity. Figure 10 displays the protein residues’ root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values. It is evident that the RMSF values for the residues found in the protein’s active sites are less than 2 Å.

Table 3 presents the binding free energy values of ligand-protein complexes for compounds 5 h and 5 g against 1HVY. The negative total binding free energy values for both compounds indicate a strong binding affinity to the target protein. Specifically, the total binding free energies for 5 h and 5 g are − 56.35 kcal/mol and − 61.25 kcal/mol, respectively. Among the different energy components, the Van der Waals energy exhibits notably lower (more negative) values for both compounds, measuring − 38.59 kcal/mol for 5 h and − 39.54 kcal/mol for 5 g. These results suggest that Van der Waals interactions are the primary contributors to the overall binding affinity.

DFT analysis

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a powerful tool in quantum chemistry and drug design that can help predict the biological properties of compounds. DFT can be employed to calculate molecular parameters such as the energies of molecular orbitals (HOMO and LUMO), dipole moments, and atomic charges. For a chemical compound, thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS, and ΔG) can provide insights into its structural stability, flexibility, solubility, and phase behavior. This information is invaluable for drug design, solvent selection, and the optimization of laboratory conditions. The interpretation of these parameters enhances our understanding of ligand behavior under various conditions and can lead to improved performance in biological applications. The HOMO (highest occupied molecular orbital) and LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) are crucial for understanding the electronic behavior of molecules, as well as the energy gap between them (ΔE = LUMO - HOMO). A smaller energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO suggests a more reactive molecule, as electron transfer between these orbitals occurs more readily. A larger energy gap typically indicates a more stable molecule, as more energy is required for electronic excitation. Molecules with an appropriate energy gap can function as effective drugs because they maintain a favorable balance between stability and reactivity46. These parameters were examined for the molecules 5 g and 5 h. As illustrated in the Fig. 11, the energy gap (E-gap) for 5 h is larger than that for 5 g, indicating that 5 g is more reactive. The biological results indicated that this compound is less active. This may be attributed to the chemical environment, including factors such as the solvent and the presence of functional groups, which can significantly influence ionization energy and electron affinity values47. Molecules with lower Gibbs free energy (ΔG) and negative enthalpy (ΔH) exhibit a greater affinity for binding to biological receptors and may demonstrate improved therapeutic effects. Compound 5 h, with a ΔG of −1129.137 and an enthalpy of −1129.062, has shown superior biological activity compared to 5 g, which has a ΔG of −1122.129 and an enthalpy of −1122.052, respectively. Molecules with lower ionization energy or higher electron affinity tend to be more reactive, with 5 h exhibiting a higher electron affinity than 5 g. The electrostatic potential (ESP) is a representation that illustrates the distribution of electrostatic potential in the space surrounding a molecule. This map is generated through quantum calculations and offers valuable insights into areas of high electron density (negative regions) and low electron density (positive regions). ESP is extensively utilized in studies of molecular interactions, the identification of active sites within molecules, and drug design. This map is particularly beneficial for predicting how molecules will interact with one another and with various chemical environments, as regions of positive and negative potential can lead to electrostatic attraction or repulsion, respectively48. Figure 12 shows the ESP plot for compounds 5 h and 5 g. The red areas on the plots indicate regions of the molecule that are more negatively charged, making them more likely to undergo electrophilic attacks. In contrast, the blue areas represent regions with a higher positive charge, which are linked to nucleophilic reactivity (Table 4).

Pharmacokinetic profiles

Lipinski’s Rule of Five is a set of empirical criteria used to predict the absorption and penetration of drug compounds in the body. Proposed by Christopher Lipinski in 1997, this rule is based on a review of over 2,000 approved drugs. According to the rule, compounds that are more likely to be orally absorbed typically possess a molecular weight of less than 500 Daltons, a LogP value of less than 5, fewer than 5 hydrogen bond donors, fewer than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors, and fewer than 10 rotatable bonds. These criteria assist researchers in designing compounds that are more likely to succeed in drug development. However, it is important to note that this rule has limitations and may not be applicable to biologics or compounds absorbed through unconventional routes. In these series of synthesized compounds, all of them obeyed the Lipinski rule of 5. Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) serves as a complementary parameter in evaluating the pharmacological properties and predicting the absorption and permeability of drugs. TPSA is a crucial metric in medicinal chemistry, defined as the sum of the surface areas of polar atoms (primarily oxygen and nitrogen) and their associated hydrogens within a molecule. This parameter reflects the polarity of a molecule and directly influences its lipid solubility and ability to traverse biological membranes. Generally, TPSA values below 60 A2 indicate favorable permeability through biological membranes, whereas values exceeding 140 A2 are typically linked to poor permeability. For these series of compounds, the TPSA values was between 73.26 and 119.08 A2 which indicate favorable permeability (Table 5).

Human intestinal absorption (HIA%) is a critical parameter in pharmacokinetics and the assessment of drug efficacy, representing the percentage of a drug that is absorbed through the intestinal wall and enters the bloodstream following oral administration. This parameter directly influences the bioavailability of the drug and is a key factor in the design and optimization of drug formulations. An HIA value between 70% and 90% indicates good absorption, suggesting that these compounds are typically well-suited for oral formulations due to their high systemic absorption, which allows them to achieve therapeutically effective concentrations in the bloodstream. All compounds were in an acceptable range. The Caco-2 cell assay is a widely used model for predicting the intestinal absorption of drugs and their pharmacokinetic properties. By measuring the permeability of drugs in Caco-2 monolayers and calculating the permeability coefficient (Papp), researchers can evaluate the intestinal absorption rate and the potential for drugs to cross cell membranes. In this assay, a permeability coefficient greater than 10 nm/s indicates high permeability and favorable intestinal absorption, while values between 1 and 10 nm/s suggest moderate permeability. Values below 1 nm/s indicate low permeability and poor absorption of the compounds. In this series of synthesized compounds, Papp values ranged from 20.30 to 23.41 nm/s, indicating high permeability and good intestinal absorption for these compounds. The MDCK assay is a valuable tool for predicting the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs, particularly regarding intestinal absorption and blood-brain barrier penetration. The permeability ranges established in this assay assist researchers in identifying compounds with optimal absorption potential while eliminating poorly absorbed compounds during the early stages of drug development. The permeability ranges in the MDCK assay are typically assessed based on the permeability coefficient (Papp). Values greater than 20 nm/s indicate high permeability and good absorption, values between 5 and 20 nm/s indicate moderate permeability, and values less than 5 nm/s indicate poor permeability and absorption. The 5 h compound, identified as the most effective compound, exhibited a permeability coefficient of 14.19 nm/s, suggesting moderate intestinal absorption. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitors are substances that decrease the activity of a glycoprotein functioning as an efflux pump in the cell membranes of various tissues. P-gp facilitate the transport of foreign substances from inside the cell to the outside. Of all the compounds, 5d and 5e were assessed for their potential as P-glycoprotein inhibitors. The primary objective of the In Vitro skin permeability test is to evaluate the penetration of a compound through the skin layers and to predict its systemic or local absorption. The permeability coefficient reflects the rate at which the compound penetrates the skin. LogKp values ranging from − 0.44 to −1.44 indicate high permeability, values between − 1.44 and − 2.44 suggest moderate permeability, and values exceeding − 2.44 signify low permeability. For the synthesized compounds, the LogKp values were found to be between − 2.92 and − 4.30, indicating low permeability of these compounds through the skin. Plasma protein binding (PPB) refers to the extent to which a drug binds to blood plasma proteins, such as albumin, globulins, and lipoproteins. Drugs with high binding affinity tend to remain in the plasma for a longer duration and exhibit reduced tissue penetration. The typical range for plasma protein binding is generally between 50% and 99%; however, this can vary based on the specific drug and its therapeutic objectives. The PPB values for the synthesized compounds ranged from 29.72% to 47.07%, indicating that these compounds exhibit a low affinity for plasma proteins. For non-CNS drugs, low blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration is preferred to minimize central nervous system (CNS)-related side effects. The BBB values for the compounds ranged from 0.02 to 0.47. This range indicates that these compounds can cross the BBB to some extent; however, their concentrations in the brain are significantly lower than those in plasma (Table 6).

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully designed, synthesized, and characterized a novel series of 6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)-substituted benzyl-3-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione derivatives. Among these, compound 5 h emerged as the most promising candidate based on its cytotoxic, apoptotic, and cell cycle–arresting activities. Compared to previously reported pyrimidine- and uracil-based scaffolds, our hybrid design strategy—combining the uracil core with a 4-aminopiperidine moiety, addresses existing limitations related to solubility, pharmacokinetic stability, and target selectivity. This work thus fills a significant gap in the literature, where most prior studies have focused on single-core uracil derivatives with limited biological stability and restricted mechanistic insights. The present study offers several advantages over previous reports. First, it integrates computational and experimental approaches, including molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, density functional theory (DFT) analyses, and in silico pharmacokinetic profiling which collectively strengthen the mechanistic interpretation of the observed biological activity. Second, our structure activity relationship (SAR) analysis emphasizes the critical role of para-halogen substitutions, particularly fluorine, in enhancing anticancer potency, providing a clear design strategy for future analogs.

Future perspectives

Taken together, our findings strongly suggest that compound 5 h is a promising lead candidate for further development as a thymidylate synthase-targeting anticancer agent. Future research should focus on expanding the structural diversity of this series to optimize potency and selectivity, as well as evaluating the in vivo efficacy and safety profile in appropriate animal models. Additionally, mechanistic validation through direct thymidylate synthase enzyme inhibition assays, knockdown and overexpression studies, and combination therapy evaluations with clinically used chemotherapeutics such as 5-fluorouracil or cisplatin could further establish the therapeutic potential of 5 h. These efforts will help bridge the gap between the current in vitro and computational findings and the translational requirements for preclinical drug development.

Limitations

Although these findings are promising, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the mechanistic conclusions regarding TS inhibition are primarily based on computational analyses (docking and molecular dynamics simulations) rather than direct biochemical or cellular target validation. Future studies should incorporate enzyme activity assays or Western blotting to confirm TS inhibition at the protein level. Second, all biological evaluations were conducted in vitro; therefore, in vivo pharmacokinetic and efficacy studies are necessary to establish the therapeutic relevance and safety of these derivatives. Finally, expanding the compound library with additional structural modifications could further enhance potency and selectivity.

Data availability

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. We have presented all data in the form of Figures. The PDB code (1HVY) was retrieved from protein data bank (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1HVY.

References

Zaorsky, N. G. et al. Causes of death among cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 28 (2), 400–407 (2017).

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int. J. Cancer. 149 (4), 778–789 (2021).

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 136 (5), E359–E386 (2015).

Compton, C. The nature and origins of cancer, in Cancer: the Enemy from Within: A Comprehensive Textbook of Cancer’s Causes, Complexities and Consequences. Springer. 1–23. (2020).

Ma, F., Laster, K. & Dong, Z. The comparison of cancer gene mutation frequencies in Chinese and US patient populations. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 5651 (2022).

Biswas, T. et al. Nitrogen-fused heterocycles: empowering anticancer drug discovery. Med. Chem. 20 (4), 369–384 (2024).

Kumar, A. et al. Nitrogen containing heterocycles as anticancer agents: a medicinal chemistry perspective. Pharmaceuticals 16 (2), 299 (2023).

Frank, É. & Szőllősi, G. Nitrogen-containing heterocycles as significant molecular scaffolds for medicinal and other applications. MDPI. p. 4617. (2021).

Kumar, A. et al. Medicinal chemistry perspective of pyrido [2, 3-d] pyrimidines as anticancer agents. RSC Adv. 13 (10), 6872–6908 (2023).

Natarajan, R. et al. Structure-activity relationships of pyrimidine derivatives and their biological activity-A review. Med. Chem. 19 (1), 10–30 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. Synthesis and anticancer evaluation of diaryl pyrido [2, 3-d] pyrimidine/alkyl substituted pyrido [2, 3-d] pyrimidine derivatives as thymidylate synthase inhibitors. BMC Chem. 18 (1), 161 (2024).

Van Oirschot, M. et al. Raltitrexed as a substitute for 5-fluorouracil in combination with pembrolizumab and platinum in a patient with metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and coronary artery disease: a case report. Annals Translational Med. 13 (3), 32 (2025).

Ahmed, K., Choudhary, M. I. & Saleem, R. S. Z. Heterocyclic pyrimidine derivatives as promising antibacterial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 259, 115701 (2023).

Jeelan Basha, N. & Chandana, T. Synthesis and antiviral efficacy of pyrimidine analogs targeting viral pathways. ChemistrySelect 8 (19), e202205009 (2023).

ur Rashid, H. et al. Research developments in the syntheses, anti-inflammatory activities and structure–activity relationships of pyrimidines. RSC Adv. 11 (11), 6060–6098 (2021).

Mahapatra, A., Prasad, T. & Sharma, T. Pyrimidine: a review on anticancer activity with key emphasis on SAR. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 7 (1), 123 (2021).

de Pinheiro, S. M. Molecular hybridization: a powerful tool for multitarget drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 19 (4), 451–470 (2024).

Shalini & Kumar, V. Have molecular hybrids delivered effective anti-cancer treatments and what should future drug discovery focus on? Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 16 (4), 335–363 (2021).

Abdelshaheed, M. M. et al. Piperidine nucleus in the field of drug discovery. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 7 (1), 188 (2021).

Vodenkova, S. et al. 5-fluorouracil and Other Fluoropyrimidines in Colorectal Cancer: Past, Present and Future 206,107447 (Pharmacology & therapeutics, 2020).

Baziar, L. et al. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and computational studies of 4-Aminopiperidine-3, 4-dihyroquinazoline-2-uracil derivatives as promising antidiabetic agents. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 26538 (2024).

Baziyar, L. et al. Novel uracil derivatives as anti-cancer agents: design, synthesis, biological evaluation and computational studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1302, 137435 (2024).

Huang, L. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of dehydroabietic acid-pyrimidine hybrids as antitumor agents. RSC Adv. 10 (31), 18008–18015 (2020).

Iacob, S. et al. Hybrid molecules with purine and pyrimidine derivatives for antitumor therapy: News, Perspectives, and future directions. Molecules 30 (13), 2707 (2025).

Sharma, S. et al. A review on pyrimidine-based pharmacophore as a template for the development of hybrid drugs with anticancer potential. Mol. Diversity,29 1–23. (2025).

Elledge, R. M. et al. Evaluation of thymidylate synthase RNA expression by polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Cell. Probes. 8 (1), 67–72 (1994).

Derenzini, M. et al. Evaluation of thymidylate synthase protein expression by Western blotting and immunohistochemistry on human colon carcinoma xenografts in nude mice. J. Histochem. Cytochemistry. 50 (12), 1633–1640 (2002).

Mori, R. et al. The mechanism underlying resistance to 5-fluorouracil and its reversal by the Inhibition of thymidine phosphorylase in breast cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 24 (3), 311 (2022).

Kumar, A. et al. Regulation of thymidylate synthase: an approach to overcome 5-FU resistance in colorectal cancer. Med. Oncol. 40 (1), 3 (2022).

Sen, A. & Karati, D. An insight into thymidylate synthase inhibitor as anticancer agents: an explicative review. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 397 (8), 5437–5448 (2024).

Murugavel, S. et al. Synthesis, crystal structure analysis, spectral investigations (NMR, FT-IR, UV), DFT calculations, ADMET studies, molecular docking and anticancer activity of 2-(1-benzyl-5-methyl-1H-1, 2, 3-triazol-4-yl)-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-6-methoxypyridine–a novel potent human topoisomerase IIα inhibitor. Journal of Molecular Structure. 1176, 729–742 (2019).

Parenti, M. D. et al. Discovery of the 4-aminopiperidine-based compound EM127 for the site-specific covalent Inhibition of SMYD3. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 243, 114683 (2022).

Zhang, J. J. et al. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel 4-aminopiperidine Derivatives as SMO/ERK Dual Inhibitors. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 74, 117051 (2022).

Benedetto Tiz, D. et al. New halogen-containing drugs approved by FDA in 2021: an overview on their syntheses and pharmaceutical use. Molecules 27 (5), 1643 (2022).

Shabir, G. et al. Chemistry and Pharmacology of fluorinated drugs approved by the FDA (2016–2022). Pharmaceuticals 16 (8), 1162 (2023).

Zare, S. et al. 6-Bromoquinazoline Derivatives as Potent Anticancer Agents: Synthesis, Cytotoxic Evaluation, and Computational Studies. Chemistry & Biodiversity. 20(7), e202201245 (2023).

Ataollahi, E. et al. Novel Quinazolinone derivatives as anticancer agents: Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and computational studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1295, 136622 (2024).

Phan, J. et al. Human thymidylate synthase is in the closed conformation when complexed with dUMP and raltitrexed, an antifolate drug. Biochemistry 40 (7), 1897–1902 (2001).

Emami, L. et al. In-silico screening of Staphylococcus aureus antibacterial agents based on Isatin scaffold: QSAR, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation and DFT analysis. Molecular Physics. e2398134 (2024).

Zare, F. et al. A combination of virtual screening, molecular dynamics simulation, MM/PBSA, ADMET, and DFT calculations to identify a potential DPP4 inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 7749 (2024).

Poustforoosh, A. et al. Correction: Structure-Based drug design for targeting IRE1: an in Silico approach for treatment of cancer. Drug Res. 74 (02), e1–e1 (2024).

Poustforoosh, A. Optimizing kinase and PARP inhibitor combinations through machine learning and in Silico approaches for targeted brain cancer therapy. Mol. Diversity 29 1–11 (2025).

Poustforoosh, A. The impact of cationic/anionic ratio on the physicochemical aspects of catanionic niosomes as a promising carrier for anticancer drugs. J. Mol. Liq. 408, 125338 (2024).

Poustforoosh, A. Scaffold Hopping Method for Design and Development of Potential Allosteric AKT Inhibitors. Molecular Biotechnology. 1–15 (2024).

Emami, L. et al. Synthesis, design, biological evaluation, and computational analysis of some novel uracil-azole derivatives as cytotoxic agents. BMC Chem. 18 (1), 3–3 (2024). View in Scopus

Tandon, H., Chakraborty, T. & Suhag, V. A brief review on importance of DFT in drug design. Res. Med. Eng. Sci. 7 (4), 791–795 (2019).

Selvakumari, S. et al. Solvent effect on molecular, electronic parameters, topological analysis and Fukui function evaluation with biological studies of Imidazo [1, 2-a] pyridine-8-carboxylic acid. J. Mol. Liq. 382, 121863 (2023).

Murray, J. S. & Politzer, P. The electrostatic potential: an overview. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comput. Mol. Sci. 1 (2), 153–163 (2011).

Funding

Financial assistance from the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, grant numbers 30102 is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B. synthesized compounds and performed the biological assay. E.A. supervised the biological section. Z. R. contributed to the design and characterization of compounds as well as the preparation of the manuscript. Y. A. synthesized the compounds. M.R.A. synthesized the compounds. A.P. performed MD study. S.Z. contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. M.E. performed the MTT assay. M.M.M. performed the DFT analysis. L.E. edit the manuscript and supervised all phases of the study. S. Kh. supervised all phases of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baziar, L., Ataollahi, E., Rezaei, Z. et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel 6-(4-aminopiperidin-1-yl)-substituted benzyl-3-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione derivatives as potential anticancer agents targeting thymidylate synthase. Sci Rep 15, 40991 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24828-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24828-5