Abstract

The large-scale integration of renewable energy into the grid through flexible DC transmission systems has become an inevitable trend in power delivery. Model-based protection schemes, unaffected by power source characteristics, have been widely applied in renewable energy grid-connected systems. However, in a dual-end weakly-fed AC system, this results in significant adaptability issues with existing model-based protection schemes. To address this, this paper proposes an active line model identification protection based on characteristic frequency phase for dual-end weakly-fed AC system. First, this paper investigates the adaptability of conventional model recognition principles in a the dual-ended weakly fed AC system. Building on this, a control strategy is proposed that utilizes Modular Multilevel Converters (MMC) for the injection of characteristic frequency signals. The criteria for selecting the injected signals and their extraction methods are outlined. Subsequently, an analysis of the line model under injected characteristic frequency signals is presented, focusing on the differences in the phase characteristics of the line model at various fault locations. Finally, in the PSCAD/EMTDC electromagnetic simulation platform simulation, combined with empirical wavelet transform and Prony (EWT-Prony) algorithm to extract the characteristic frequency phase of the line model, the effectiveness of the proposed protection scheme is verified. The results demonstrate that the proposed scheme can withstand high fault impedance (300Ω) and noise interference (25 dB), confirming its robustness and reliability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

ITH the “dual carbon” strategy is increasingly put into action and its associated action plans, the installed capacity of renewable energy sources such as photovoltaic and wind power has increased significantly in recent times. However, the distribution of energy resources and demand is inversely related, with renewable energy generation characterized by strong randomness and spatial–temporal correlation. These factors highlight the need for the expansion of AC/DC interconnected power grids to accommodate long-distance, large-capacity transmission and facilitate the inter-provincial and inter-regional consumption of renewable energy in the near future1,2.

Large-scale renewable energy transmission methods include AC transmission, conventional DC transmission, and flexible DC transmission. Given the location of large-scale renewable energy bases, such as those in deserts, Gobi regions, and barren areas often distant from the primary power network and lacking synchronous power support flexible DC transmission based on voltage-source converters (VSC) offers distinct advantages. These include long transmission distances, autonomous regulation of active and reactive power, and the ability to operate without requiring grid support for commutation. Moreover, flexible DC transmission can provide active voltage and frequency support to the isolated AC grid at the sending end3,4,5. As a result, flexible DC transmission has become the preferred solution for long-distance power transmission from extensive renewable energy sources bases located in remote areas.

The primary cause of performance degradation in conventional power–frequency protection is the change in the characteristics of the power supply. Therefore, when designing protection principles, it is essential to consider approaches that do not depend on the power supply characteristics. One effective strategy is to explore the differences in the protected line model or key parameters under internal and external fault conditions, which can then be used to develop a new protection principle. Parameter identification-based protection, which does not rely on the characteristics of the power source, primarily leverages the differences in models and parameter characteristics following a fault to establish fault identification criteria6,7. For the protection of renewable energy transmission lines, reference8 fully utilizes the characteristics of the line’s resistance-inductance-capacitance (RLC) model to develop a new principle for longitudinal protection, with the goal of enhancing the speed and sensitivity of protection actions. However, these methods still rely on fault models based on power–frequency characteristics. In the equivalent model of an internal fault, the effect of the backside power source cannot be eliminated. Furthermore, the power–frequency feature extraction algorithm is significantly affected by harmonics generated by power electronic devices, which may lead to misoperation, particularly during the rectification operation mode at the flexible DC converter station side when protecting the AC-side transmission lines in renewable energy transmission systems.

For the transient protection of the AC-side line in new energy flexible DC transmission systems, some scholars have proposed new protection principles based on waveform similarity or singular value decomposition. Essentially, these protection methods exploit the differences between internal and external fault models of the line, which can be classified as a form of model error identification. Various approaches, such as cosine similarity9, Spearman similarity10, Toeplitz matrix transformation11, and singular value decomposition12, have been suggested. These principles utilize the differences in the control strategy and adjustment speed of the bidirectional converter to differentiate between internal and external faults. However, this type of protection is highly sensitive to the control strategies, and the relevant time-domain algorithms often rely on differentiation methods, making them susceptible to harmonic interference. Some high-frequency protection methods exploit the linear characteristics of the converter impedance in the high-frequency band, but their practical application in engineering still requires further refinement.

The highly flexible and controllable nature of power electronics devices in renewable energy systems with flexible DC transmission provides valuable insights for fault identification. In the AC grid or flexible DC system where renewable energy is integrated, some studies have already proposed the concept of active injection protection. References10,13 introduced improved distance impedance elements based on characteristic frequency impedance information and single-ended distance protection using harmonic measurements, both of which rely on the active injection of harmonic frequencies. Reference14 introduced a differential protection method based on frequency differences in current signals by injecting different frequency characteristic signals from the converter stations at each end of the system. However, these active detection protection methods often involve the injection of characteristic signals from the renewable energy-side converter stations. These stations are complex, with multiple voltage levels, various types of power electronic devices, and diverse protection control devices. To ensure reliable and sensitive fault detection, such protection systems must account for the deep coupling and interactive effects of control devices across different time scales, spatial levels, and voltage levels. Coordinated control and protection methods, which consider the dynamic response differences of various equipment types, multiple spatial locations, and time scales, still require further investigation.

In summary, the existing protection schemes applied to the dual-end weakly-fed AC system have the following shortcomings:

-

The performance of traditional power frequency protection is degraded by the change of power supply characteristics, and the conventional transient protection fails to fully consider the influence of control strategy. The protection scheme based on the amount of power frequency information has limitations when applied to the dual-end weakly-fed AC system.

-

The protection scheme identified by the conventional line model, which are not affected by the power supply characteristics and is widely used in renewable energy grid-connected systems. However, these schemes are affected by line parameters and converter operation modes. Therefore, its adaptability in the dual-end weakly-fed AC system requires further analysis.

-

With the wide application of power electronic equipment, active detection protection is facilitated at the technical level. However, there are some problems. For example, signal injection needs to consider the deep coupling and interaction effects of controller devices on time scale, spatial dimension and multiple voltage levels.

This paper introduces a specific characteristic signal into the grid by controlling the MMC. The protection device identifies both internal and external faults in the line by exploiting the distinct response characteristics of the line model under characteristic frequency electrical quantities. The proposed scheme has the following contributions:

-

Aiming at the problems existing in the conventional model recognition principle, this paper adopts the idea of control and protection coordination, and uses the active injection signal to fuse its own line model. An improved model identification protection scheme based on characteristic frequency phase is proposed. The scheme is not affected by the back-side system and does not depend on the calculation error of line parameters.

-

This paper proposes to use the inner loop current control link of MMC to realize differential mode injection, and the feedback regulation mechanism makes the injection signal better. The single-ended signal injection effectively avoids the uncertainty of the power flow, so as to solve the problem of deep coupling and interaction effect of the injected signal in the application of the scheme.

-

The scheme proposed in this paper cooperates in the fault ride-through stage, and the control strategy is fully considered. The scheme uses the combined empirical wavelet transform and Prony (EWT-Prony) algorithm to ensure that the de-noising situation extracts the stable characteristic frequency phase, and the protection setting value does not depend on the simulation setting.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Chapter 2 analyzes the limitations of the conventional model-based identification protection scheme in the dual-end weakly-fed AC system. Chapter 3 presents the differential mode injection strategy for active probing signals via the flexible DC converter station side, providing criteria for the selection of characteristic frequency signals and methodologies for signal extraction. In Chapter 4, a novel characteristic frequency band is constructed under fault conditions, based on the actively injected signals described in Chapter 3. This enables the development of fault identification criteria derived from the fault signatures of the characteristic line model. Chapter 5 proposes a longitudinal protection scheme based on active probing and details its implementation process. Chapter 6 presents a performance evaluation of the proposed protection scheme across various scenarios. Finally, Chapter 7 provides a comprehensive summary and conclusion.

Adaptability analysis of conventional model identification in dual-end weakly-fed AC system.

Fault characterization analysis in dual-end weakly-fed AC system

A large-scale photovoltaic cluster networking AC system is constructed based on the structure and parameters of a large-scale renewable energy delivery system using flexible DC transmission, as shown in Fig. 1. The photovoltaic inverters are stepped up to 525 kV through step-up transformers, and the collected power is transmitted via collection lines to the flexible DC converter station, where high-voltage DC is sent to the grid. Figure 1 illustrates the schematic of the large-scale photovoltaic cluster with flexible DC transmission.

The renewable energy photovoltaic side converter station utilizes a VSC, while the flexible DC converter station is equipped with the MMC. The transmission line has a total length of 230 km, with the MN field covering 100 km. Five fault points are identified at various positions along the AC transmission line. Internal faults are located at F2 (10%), F3 (50%), and F4 (90%), while external faults are at F1 and F5.

Where F represents the fault points, the M side refers to the renewable energy side, and the N side refers to the flexible DC side. In the diagram, the modulation stages for the photovoltaic inverter and flexible DC converter use space vector pulse width modulation and nearest level modulation strategies, respectively.

During normal operation, the positive sequence current reference value of the grid side converter of the photovoltaic station is given by the outer loop active power and reactive power for the Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) controller. The main form of new energy power station with voltage source converter as grid-connected interface. After the fault, in order to ensure that the photovoltaic station does not operate off-grid when the voltage drops, the photovoltaic side converter needs to start the Low Voltage Ride Through (LVRT) control to change the positive sequence current reference value to provide reactive power support, and the initial phase angle is provided by the phase-locked loop. The MMC of the flexible DC side converter station adopts the control scheme of constant frequency voltage configuration. The shaft voltage is taken as the outer ring target, and the constant frequency control is adopted to realize the network control of voltage amplitude, initial phase and rotating electrical angle. In order to prevent MMC from being damaged due to excessive output current, the VSC-DC converter needs to start Fault Ride Through (FRT) control, which adopts step-down V/F control. Under the joint regulation of step-down control and inner loop controller output inner loop current reference value, MMC exhibits current source characteristics during the fault period, and can have rectifier mode and inverter mode according to the specific type, severity and fault ride-through control requirements of the fault15.

The flexible DC converter station uses a dual-loop controller, consisting of a power outer loop and a current inner loop. To protect the MMC from excessive output current, a current limiting module is placed between the power outer loop and the current inner loop controllers. When a fault occurs on the AC-side line, the MMC’s fault ride-through control determines the current limit values on the positive-sequence d and q axes. These values depend on factors such as whether the grid relies on the MMC for reactive power support and whether the short-circuit current needs to be limited16.

Under the influence of the current limiting module and the current inner loop controller, the MMC’s fault output exhibits a current source characteristic. Depending on the fault type, its severity, and the fault ride-through control mode, two operation modes are possible: rectification mode and inversion mode. In rectification mode, the converter station behaves as a load, consuming active power. In inversion mode, the converter station supplies power to the grid. After a voltage drop caused by a short-circuit fault, the converter station typically injects reactive power, depending on the depth of the voltage drop, thereby exhibiting partial capacitive characteristics17.

Based on the theory discussed above, a Single-Phase Ground fault (SPG) is used as an example. The equivalent system model of the flexible DC converter station under different operating modes during fault conditions is shown in Fig. 2.

Where \(\dot{I}_{f}\) represents the fault current at the fault point, \(Z_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) is the equivalent impedance of the flexible DC converter station, \(Z_{{\text{L}}}\) is the line impedance, \(Z_{{{\text{pv}}}}\) is the equivalent impedance of the photovoltaic converter station, and λ is the ratio of the distance from the converter station to the fault point relative to the total line length. The direction from the busbar to the line is considered positive. \(\dot{I}_{M}\) and \(\dot{I}_{N}\) are the measured currents at the M-side and N-side ends of the line, respectively.

When the converter station operates in rectification mode, it acts as a load, consuming active power. As a result, the real part of \(Z_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) is greater than zero. In contrast, during inversion mode, the converter station supplies power to the grid, causing the real part of \(Z_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) to be less than zero. After a short-circuit fault causes a voltage drop in the power grid, the converter station typically injects reactive power, depending on the depth of the voltage drop. This leads to partial capacitive characteristics, resulting in the imaginary part of \(Z_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) being less than zero.

It can be seen from Fig. 3 that the current on both sides of the line MN has the following relationship:

Due to the large transition resistance and small voltage drop, the converter station mainly transmits active power, and its output reactive power is small. Therefore, the real part \(R_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) of \(Z_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) is generally significantly larger than the imaginary part \(X_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\), that is, \(R_{{{\text{hvdc}}}} \gg {\text{X}}_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\), mainly resistive. Due to the weak feed characteristics of the converter station, the amplitude of \(Z_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) is generally much larger than \({\uplambda }X_{{\text{L}}}\), that is, \(\left| {{\text{Z}}_{{{\text{hvdc}}}} \, } \right| \gg {\uplambda }X_{{\text{L}}}\) Therefore, \(R_{{{\text{hvdc}}}} \gg ({\uplambda }X_{{\text{L}}} - X_{{{\text{hvdc}}}} )\) According to the above analysis and Eq. (2), the phase relationship between the current phasors obtained by the phase relationship between the impedance phasors under different operating modes of the converter station is given. The phase relationship between each current phasor is further deduced, which lays a theoretical foundation for subsequent adaptability analysis18.

The photovoltaic side consistently exhibits a “feed-in” characteristic, supplying current to the fault point. The flexible DC converter station shows a “feed-in” characteristic in inverter mode. In rectifier mode, however, the phase angle difference between the converter station current and the fault current at the fault point is obtuse, indicating a “draw-out” characteristic, where the converter station draws current from the fault point19. The simulation results for both operating modes are shown in Fig. 3.

Adaptability analysis of existing model recognition principles

The new energy transmission line using flexible direct current (DC) forms a dual-end weak-feed AC system, a typical fully power-electronicized power system. In such systems, voltage and frequency are entirely controlled by power electronic devices. When a fault occurs, the loss of synchronous machine support leads to more significant nonlinear responses and more pronounced transient voltage and current fluctuations in the control of the power electronic devices. The protection scheme based on parameter and model identification does not directly solve for fault electrical quantities and parameters. Instead, it uses model equivalence methods, focusing on identified electrical parameters that are unaffected by the fault characteristics of the converter station. However, due to the unique fault characteristics of the dual-end weakly-fed AC system, traditional model-based protection schemes face issues such as misoperation and reduced sensitivity when applied to these systems.

Conventional protection schemes based on model identification construct criteria using power frequency components. Pilot protection is then applied based on time-domain model identification across the entire frequency range. Model identification based on power–frequency components is significantly influenced by transient components during phasor extraction. This is due to the weak-feed nature of the bidirectional weak-feed system and the fast response speed of power electronic converters20. Research on time-domain model identification protection using full-frequency domain information has been applied to single-ended weak-feed systems. During faults, short-circuit currents from both sides of the system feed into the fault point. The main criterion relies on the characteristic that external faults conform to the capacitive model, while internal faults do not21,22. In the dual-end weakly-fed AC system, the flexible DC converter station side operates in two modes during faults. In rectifier mode, the current on the flexible DC converter station side exhibits a “draw” characteristic. Specifically, in rectifier mode, the impedance measured at the protection installation on the flexible DC converter station side corresponds to the DC feedout system impedance. Therefore, when an internal fault occurs, the line model exhibits characteristics that align with the capacitive model.

As an example, the adaptability of model identification in the dual-end weakly-fed AC system is analyzed for an internal SPG fault, with the line modeled using a π-model. The time-domain circuit diagram for this internal fault is shown in Fig. 4

Where the capacitor model shown in Fig. 4 is simplified into a lumped parameter model, evenly distributed at both ends. \(u_{{\text{M}}} (t)\) is the voltage at measurement point M. \(i_{{\text{M}}} (t)\) is the current measured at point M.\(u_{{\text{N}}} (t)\) is the voltage at measurement point N. \(i_{{\text{N}}} (t)\) is the current measured at point N. \(L_{0}\),\({\text{R}}_{0}\),\({\text{C}}_{\text{M}}\),\({\text{C}}_{N}\) are the lumped parameters corresponding to the inductance, resistance, and capacitance of the line’s π model. \({\text{R}}_{f}\) is the fault resistance during a fault. λ is the proportional coefficient of the distance from the measurement point to the fault point relative to the protection line distance.

To further analyze the characteristics of the equivalent model for the two operation modes of the flexible DC converter station during the fault period, the internal impedance of the T-connected line in the fault area is transformed using a star-delta conversion. The time-domain circuit diagram after the transformation is shown in Fig. 5.

After the equivalent transformation, the line’s equivalent impedance can be expressed as shown in Eq. (3), Eq. (4) and Eq. (5)

where in Eq. (2), (3) and (4): ω is the fundamental frequency; \(R_{12}\), \(R_{23}\), and \(R_{13}\) denote the resistance values of the fault line model after star-delta transformation; \(L_{12}\),\(L_{23}\), and \(L_{13}\) represent the inductance values of the fault line model after star-delta transformation.

When an internal fault occurs, the capacitive current flowing through the outgoing line is approximately neglected. The differential current, \(i_{{{\text{cd}}}} (t)\), and the differential voltage, \(u_{{{\text{cd}}}} (t)\), are defined by Eq. (6) and Eq. (7), respectively.

According to the shunt principle, the current distribution factors for the outgoing line currents are set as km and kn, as shown in Eq. (8).

Next, further analysis is conducted based on different operating modes of the converter station during the fault. Due to the specific nature of the dual-end weakly-fed AC system, a rectified operating mode occurs at the converter station on the flexible DC converter side during a fault. The time-domain equivalent diagram for an internal fault in rectified mode is shown in Fig. 6. The red arrows indicate the actual current flow direction of the short-circuit current flow.

By analyzing the time-domain equivalent diagram of an internal fault in rectified mode shown in Fig. 6 and applying Kirchhoff’s Current Law, Eq. (9) is derived.

Define the current \(i_{{{\text{cd}}}}{\prime} (t)\) flowing into the fault branch as Eq. (10).

The relationship between the differential current \(i_{{{\text{cd}}}} (t)\) and the current \(i_{{{\text{cd}}}}{\prime} (t)\) is analyzed by the Kirchhoff current theorem as shown in Eq. (11).

Therefore, based on Eq. (8), the relationship between the currents i12(t), i23(t) flowing through the sending line’s resistance and inductance parameters and the differential current \(i_{{{\text{cd}}}}{\prime} (t)\) is given by Eq. (12).

According to the capacitive nature of the equivalent impedance \(Z_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) of the flexible direct current (flexible DC) system, and the fact that the current \(i_{{\text{N}}} (t)\) is negative, the phasor relationship of \(u_{{\text{N}}} (t)\) can be determined from the phasor relationship of \(i_{{\text{N}}} (t)\),\(C_{{{\text{hvdc}}}}\) represents the equivalent capacitance value of the VSC-based DC (flexible DC) side system.

Through the time domain equivalent diagram of the internal fault in the rectifier mode shown in Fig. 7, the relationship between the electrical quantities of the fault equivalent branch is shown by Eq. (14) and Eq. (15).

The relationship between the differential current \(i_{{{\text{cd}}}}{\prime} (t)\) and the voltage \(u_{{{\text{cd}}}} (t)\) is given by Eq. (16).

Substituting Eq. (11) into the above Eq. (16), the relationship between differential current \(i_{{{\text{cd}}}} (t)\) and voltage \(u_{{{\text{cd}}}} (t)\) can be obtained as Eq. (17).

Additionally, by considering the phasor relationship of the equivalent impedance \(Z_{23}\) branch on the N-side, the phasor relationship between \(u_{{\text{N}}} (t)\) and the branch current \(i_{23} (t)\) can be obtained using the branch impedance model. Based on the differential current and differential voltage relationships defined in Eq. (5) and Eq. (7), the phasor diagram of the line model for an internal fault in rectified mode can be drawn, as shown in Fig. 7.

The phasor diagram of the line model for an internal fault in rectified mode shows that, during the fault, the differential voltage lags the differential current in phase. This indicates that the line model exhibits capacitive behavior. Due to the capacitive characteristics in the line model of internal faults in the dual-end weakly-fed AC system, the traditional time-domain full-quantity fault model correlation, which distinguishes between external faults (conforming to the capacitive model) and internal faults (which do not), is not applicable.

Active detection signal injection strategy

Selection of injected signal types

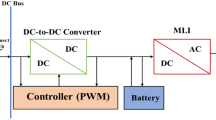

The highly flexible and controllable nature of fully power-electronic devices enables the injection of detection signals. The new energy side converter station involves multiple voltage levels, various types of power electronic devices, and different protection and control systems used for multi-level converter connections. The number of new energy photovoltaic converter stations is large, and their response to injected signals is weak. Therefore, for characteristic frequency signal injection in the dual-end weakly-fed AC system, this paper suggests using the flexible DC converter to inject the characteristic frequency signal. During a fault, the control of the MMC actively injects a characteristic frequency sine wave signal into the AC side of the dual-end weakly-fed AC system. A schematic diagram of the detection signal injected into the AC system is shown in Fig. 8.

The circuit analysis based on sine phasors has clear physical significance and a simple mathematical expression, which allows for the construction of algorithms similar to traditional protection methods. Therefore, a sine wave is injected into the system using an inverter.

Generation of injected characteristic frequency signals

The flexible DC converter station side inverter for MMC utilizes semiconductor switching devices with lower voltage ratings and forms a high-voltage inverter through a cascading method. The basic control strategies required for MMC include inner and outer loop control strategies, circulating current suppression strategies, and submodule capacitor voltage balancing strategies.

The frequency-domain form of the fundamental dynamic equation of MMC in the dq coordinate system is given by Eq. (18).

where ivd and ivq represent the d-axis and q-axis components of the three-phase AC voltage on the valve side of the MMC, respectively; usd and usq represent the d-axis and q-axis components of the three-phase AC bus voltage of the MMC converter station, respectively; udiffd and udiffq represent the d-axis and q-axis components of the three-phase differential modulation voltage of the MMC, respectively.

From Eq. (18), it can be seen that the output current of the MMC depends on the system voltage and the bridge arm differential mode voltage. Based on Eq. (18), the transfer function relationship between the differential mode voltage and the output current can be obtained, providing a theoretical foundation for the harmonic signal injection method.

Next, we consider using the differential mode injection method to inject a detection signal with a determined frequency and amplitude from the DC side to the AC side. The injection strategy control block diagram is shown in Fig. 9.

The parameter UN1 represents the q-axis voltage command value of the positive sequence voltage outer loop. According to the above analysis, it is Vref in steady state; when the negative sequence current increases to the limiting value and the MMC side starts the step-down fault ride-through control, UN1 is calculated by the corresponding control algorithm. Accordingly, UN1 can be summarized as follows:

where, represents the amplitude of negative sequence current.

PI1 and PI3: PI controllers with positive sequence voltage outer loop, respectively, are responsible for tracking voltage instructions. PI2 and PI4 are PI controllers of positive sequence current inner loop respectively, which are responsible for fast tracking current instructions and ensuring the dynamic response performance of the system.

When the injection strategy activation signal \(u_{{{\text{ctrl}}}}\) is triggered, an additional value \(u^{*}_{det - j} (j = {\text{a,b,c}})\) is added in the lower control loop of the MMC in differential mode, which corresponds to the reference values for the upper and lower bridge arm voltages, \(u_{{{\text{up}}}}\) and \(u_{{{\text{low}}}}\), as shown in Eq. (20).

where \(u_{{{\text{dif}}j}}^{*} (j = {\text{a}} ,b,c)\) and \(U_{{{\text{dc}}}}^{*}\) represent the adaptive correction functions for the differential mode voltage reference value of the upper and lower bridge arms and the voltage reference value of the DC side.

The quantity of submodules engaged in the upper and lower bridge arms at any given moment, \(N_{{{\text{up}}}}\) and \(N_{{{\text{low}}}}\), is expressed in Eq. (21).

The expression for the detection signal is given by Eq. (22).

where \(\omega_{\det }\),\(U_{{{\text{det}}}}^{*}\) and \(\varphi_{{{\text{ctrl}}}}\) represent the adaptive correction functions for the characteristic frequency of the detection signal, the amplitude of the detection signal, and the initial phase angle of the injected detection signal, respectively.

In the PSCAD model, the differential mode injection strategy is implemented, with the fifth harmonic chosen for injection and an amplitude of 0.15 p.u. An example of a three-phase short-circuit fault is simulated in PSCAD, and the injection effect is shown in Fig. 10.

To further analyze the injection effect, the amplitude-frequency characteristics of the electrical quantities after injection on the MMC side are extracted for observation, as shown in Fig. 11.

The selection of injected characteristic frequency signals

(1) Selection of frequency

The fundamental principle for selecting the frequency of the detection signal is to ensure that, while fulfilling the performance constraints of the injection device, the line at the opposite end of the non-injection source diverts the injected characteristic frequency signal. This maximizes the response characteristic differences, enhancing detection sensitivity.

(a)Performance constraints of the equipment: The reaction speed of the MMC is influenced by factors such as submodule capacitance, arm inductance, and controller parameters. In reference23, the equation in state-space form of the MMC is established, and the expression for the open-loop time constant is represented in Eq. (21).

where ωAC and Larm represent the AC fundamental frequency and the arm inductance of the MMC bridge, respectively. CSM, N, and RL are the submodule capacitance, the number of submodules, and the equivalent loss resistance, respectively.

Using the model parameters from this paper and substituting the MMC parameters into Eq. (21), the time constant is obtained as T≈0.0149 s. This implies that the detection signal frequency should not exceed 600 Hz.

(b)Impedance equivalent of non-injection sources: The non-injection source is equivalent to an LC parallel resonant circuit for the characteristic signal, and the cutoff frequency of the LC filter is its resonant frequency, as shown in Eq. (24).

where L and C represent the adaptive correction functions for the inductance and capacitance of the photovoltaic-side converter station’s VSC filter, respectively.

The PV converter acts as a non-injection source to shunt the characteristic signal emitted by the injection source. If the resonant frequency of the filter is close to the frequency of the injected signal, the non-injection source converter station is equivalent to the LC parallel resonant circuit for the characteristic frequency signal, and has high resistance to the characteristic frequency signal. The mathematical model of the PV converter station in the characteristic frequency system is an open-circuit state, and the injected signal will not be shunted. The mathematical model equivalence of the characteristic frequency of the photovoltaic converter station is shown in Fig. 12.

According to reference24, the resonant frequency of the filter typically ranges from 10 times the power frequency to half the carrier frequency. Since the carrier frequency of the photovoltaic side inverter is between 1 and 2 kHz25, the selected characteristic signal frequency should be around 500 Hz.

(c)Impact of system fault harmonics: In the normal modulation process, the harmonics output by the MMC and the background harmonics of the grid are mainly composed of odd-order components. Therefore, to highlight the fault characteristics, the harmonics injected by the MMC should theoretically be higher-frequency even-order harmonic current signals.

In conclusion, this paper selects the 10th harmonic current (500 Hz) as the characteristic signal to optimize the current protection performance.

(2) Selection of amplitude

The fundamental principle for selecting the detection signal amplitude is to minimize the impact on the grid while ensuring the measurement equipment’s detection accuracy and the tolerance capacity of the converter’s power electronic devices.

(a)Detection accuracy of the measurement equipment: Currently, electronic current transformers are commonly used in new energy flexible direct transmission projects. Electronic current transformers do not have the saturation problem of electromagnetic current transformers, offer a wide measurement bandwidth, and the measurement accuracy can reach within 1%26. Therefore, the amplitude of the detection signal should not be less than the measurement error of the measurement equipment, i.e., 0.01 p.u. of the rated voltage.

(b)Tolerance capacity of the equipment: When considering the injection signal, it is necessary to account for the submodule switching process and the safety margin of the converter arm current. If the amplitude of the injected signal is too large, it may affect the safe operation of the injection equipment. The impact of the injected signal on the equipment should be taken into consideration. From the perspective of capacitor and power device costs, the reasonable range of values is approximately 10% to 15%, meaning the voltage fluctuation component of the submodule’s capacitor should be less than 0.15 p.u.

In summary, this paper selects 0.12 p.u as the signal amplitude to optimize the current protection performance.

(3) Selection of injection duration

The fundamental principle for selecting the duration of the injected detection signal (Δt) is to inject the signal for the shortest possible time while ensuring the effective extraction of the signal’s information, in order to avoid affecting the normal operation of the healthy circuit. In consideration of system inertia, controller response delay, and transformer measurement delay, the injection duration is defined as Δt = 100 ms.

(4) Extraction of characteristic frequency signals

Methods for extracting amplitude and phase information from characteristic signals include wavelet transform, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), and the Prony algorithm. While the wavelet transform is effective at capturing time-varying features of signals, it does not provide accurate phase information. FFT reduces computational complexity by minimizing multiplication and addition operations, but its accuracy is limited by factors such as the chosen data window and DC decay components. The Prony algorithm can describe the transient characteristics of signals, but is sensitive to noise. In this paper, an EWT-Prony harmonic detection and identification algorithm is proposed.

The main principle is to decompose noisy harmonic signals using the EWT algorithm, resulting in a series of signal components. Noise components are filtered out, and the remaining signal components undergo soft-threshold wavelet denoising to enhance the harmonic signal by reducing noise. Accurate signal component quantities are determined, and the number of components is used to define the dimensional range for the Prony algorithm. After denoising, the harmonic signal undergoes vibration mode parameter identification.

This study uses the Prony algorithm to extract the amplitude and phase of the characteristic signal based on the measurements at both ends. The mathematical model is represented as Eq. (25).

where y(t) denotes the measured signal, Ai is the amplitude, ai is the attenuation factor, fi is the frequency, θi is the phase, and q is the model order. When the model order is relatively high, the computational complexity of the Prony method increases exponentially.

Protection principle based on model identification using active sensing

Necessity of introducing active detection

Since the injection time, amplitude, duration, and type of the detection signal are controllable, a sine wave signal with a specific amplitude and single frequency is injected. The fault characteristic frequency line model is then identified using the sine wave signal at that frequency. By actively injecting these signals through the converter, fault area discrimination can be achieved without relying on the fault characteristics of the new energy converter station.

Additionally, identifying the system using its characteristic frequency line model effectively mitigates the impact of reverse power flow in the rectifier mode of the flexible DC converter station. Compared to protection schemes that rely on line model parameters, using the phase characteristics of the characteristic frequency line model is less affected by errors caused by line frequency variations and electrical quantity differential factors.

By selecting the characteristic frequency to prevent signal diversion by the new energy sources, the proposed protection algorithm remains unaffected by the system’s backside impedance. During a fault, the flexible DC converter station injects the signal, thereby avoiding the impact of the MMC rectifier operating mode on traditional model-based protection. The inductive and capacitive characteristics of the characteristic frequency line model are used as criteria, without relying on the influence of line frequency variation parameters.

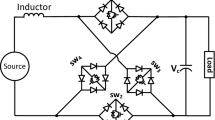

Analysis of the external fault model identification principle

Taking the external fault F1 SPG fault as an example, an analysis of the line model with injected characteristic frequency signals is conducted. Figure 13 shows the equivalent model of the characteristic frequency for the external fault.

Where 13 \(u_{{{\text{MH}}}} (t)\) represents the characteristic frequency voltage at measurement point M,and \(i_{{{\text{MH}}}} (t)\) is the measured characteristic frequency current at point M. \(u_{{{\text{NH}}}} (t)\) represents the characteristic frequency voltage at measurement point N, while \(i_{{{\text{NH}}}} (t)\) is the measured characteristic frequency current at point N. \(i_{{{\text{MCH}}}} (t)\) is the characteristic frequency current flowing through the capacitance branch to ground at the M side, and \(i_{{{\text{NCH}}}} (t)\) is the characteristic frequency current flowing through the capacitance branch to ground at the N side. \(L_{{\text{h}}}\), \(R_{{\text{h}}}\), and \(C_{{\text{h}}}\) represent the inductance, resistance, and capacitance lumped parameters of the characteristic frequency line’s π model. Rf is the fault resistance during a fault. The red arrows indicate the actual direction of the current.

By analyzing the equivalent model of the characteristic frequency for external faults in Fig. 13 and applying Kirchhoff’s Current Law, Eq. (24) can be obtained.

Through the analysis of Fig. 13, the characteristic frequency voltage characteristic frequency current relationship of the branches on both sides of the characteristic frequency line is shown in the Eq. (25).

The characteristic frequency difference current \(i_{{{\text{cdH}}}} (t)\) and the characteristic frequency difference voltage \(u_{{{\text{cdH}}}} (t)\) are defined as Eq. (27) and Eq. (28).

According to Eq. (28) and (29), it can be seen that the characteristic frequency differential voltage and the characteristic frequency differential current at both ends of the external fault line satisfy Eq. (30).

By using the electrical components’ capacitance and inductance and applying Kirchhoff’s definitions, the phasor diagram of the external fault characteristic frequency line model can be drawn, as shown in Fig. 14.

From the phasor diagram of the fault characteristic frequency line model for external fault in Fig. 14, it can be seen that the differential voltage lags the differential current, indicating that the characteristic frequency line model exhibits capacitive behavior. The range of phase angle difference between voltage and current at characteristic frequency is shown in Eq. (31).

where in Eq. (31), \(\dot{U}_{{{\text{cdH}}}}\) represents the characteristic frequency differential voltage vector form; \(\dot{I}_{{{\text{cdH}}}}\) represents the characteristic frequency differential current vector form.

Principle analysis of internal fault model identification

Taking the internal fault F3 single-phase grounding fault as an example for analysis, the line model injected with the characteristic frequency signal is analyzed. According to the method of internal fault line analysis using time-domain model identification in Section Ⅱ, the line model with the injected characteristic frequency signal for internal fault analysis is examined. As shown in Fig. 15, the equivalent model of the internal fault characteristic frequency is presented. The red arrows indicate the direction of the actual current.

In Fig. 15, the characteristic frequency line equivalent impedances Zh13, Zh12, and Zh23 undergo star-delta transformation equivalence. The line equivalent impedance can be expressed as in Eq. (32, 33, 34).

where \({\upomega }_{\det }\) represents the characteristic angular frequency; \(i_{{{\text{H}} 12}} (t)\) is the equivalent branch current shunt on the M-side fault at the characteristic frequency; and \(i_{{{\text{H}} 23}} (t)\) is the equivalent branch current shunt on the N-side fault at the characteristic frequency.where \(R_{h12}\) and \(L_{h12}\) represent the resistance and inductance of the characteristic frequency line equivalent impedance \(Z_{h12}\), \(R_{h23}\) and \(L_{h23}\) represent the resistance and inductance of the charsacteristic frequency line equivalent impedance \(Z_{h23}\), \(R_{h13}\) and \(L_{h13}\) represent the resistance and inductance of the characteristic frequency line equivalent impedance \(Z_{h13}\).

By analyzing the internal fault characteristic frequency equivalent model in Fig. 15 and applying Kirchhoff’s Current Law, Eq. (35) can be derived.

According to the shunt principle, the current distribution coefficients for the outgoing line, \(k_{{\text{hm}}}\) and \(k_{hn}\), are set as in Eq. (36).

Therefore, based on Eq. (36), the relationship between the currents \(i_{{{\text{H}} 12}} (t)\), \(i_{{{\text{H}} 23}} (t)\) flowing through the outgoing line impedance parameters and the defined differential current \(i_{cdH} (t)\) is given by Eq. (37).

By analyzing the internal fault characteristic frequency equivalent model in Fig. 15 and applying Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law, Eq. (38) and Eq. (39) can be derived.

From Eq. (35, 36, 37, 38, 39), the relationship between the differential current \(i_{cdH} (t)\) and the voltage \(u_{cdH} (t)\) is given by Eq. (40).

Based on the above analysis, the phasor diagram of the internal fault characteristic frequency line model can be drawn, as shown in Fig. 16.

From the phasor diagram of the fault characteristic frequency line model for internal faults in Fig. 16, it can be observed that the differential voltage leads the differential current, indicating that the characteristic frequency line model exhibits inductive behavior. The range of the phase angle difference between voltage and current at the characteristic frequency is given in Eq. (41).

Improved model recognition scheme based on active detection

Active injection control strategy activation criterion

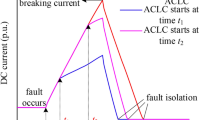

Referring to the LVRT strategy of the existing inverter-based distributed power supply, it is detected that the power frequency voltage drops more than 10% and starts after 3 ms. The additional control strategy is started to inject the detection signal during the LVRT.

During the LVRT period, an active injection strategy is employed to inject characteristic frequency currents. A significant change in the characteristic frequency current is detected at the injection terminal. To assess the stability of the extracted characteristic frequency signal, a signal processing method is applied that combines Empirical Wavelet Transform (EWT) with soft-threshold denoising and the Prony algorithm to activate the protection algorithm.

The Mean Square Error (MSE) of the Prony model is used to quantify the error between the fitted signal and the original signal. Let the original signal be denoted as y(t), the Prony model fitted signal as \(\mathop y\limits^{ \wedge } (t)\), and the signal length as N = 5. The MSE is calculated using the following equation (Eq. 41).

The criterion for assessing the stability of the characteristic frequency signal using MSE is as follows: a smaller MSE indicates a better fit of the Prony model to the original signal, implying higher reliability in the extracted characteristic frequency.

Typically, an MSE threshold of ε = 10⁻3 is established based on the context of power system oscillation analysis. When the MSE is below ε, the fit is considered satisfactory, and the characteristic frequency is deemed stable. The schematic diagram based on the MMC startup criterion is shown in Fig. 17.

Protection action criterion

Based on the analysis in Sect. “Extraction of Characteristic Frequency Signals”, the characteristic frequency line model shows inductive behavior during internal faults and capacitive behavior during external faults. The characteristic frequency line model impedance, ZH, is further defined in Eq. (44), and the fault location is determined based on the capacitive or inductive nature of the phase of ZH.

From the above, it can be concluded that the protection action criterion is given by Eq. (45).

where arg(ZH) represents the phase of the characteristic frequency line model impedance, ZH. When the equivalent impedance exhibits capacitive characteristics, the phase is negative; when it exhibits inductive characteristics, the phase is positive. When \(\arg (Z_{\text{H}} ) > + {\text{Dset}}\), it is judged as an internal fault, and when \(\arg (Z_{\text{H}} ) < - {\text{Dset}}\), it is judged as an external fault. The setting of the safety margin \({\text{Dset = }}5^\circ\) takes into account: the typical measurement error of electronic transformer (phase error < 1°); the influence of system frequency drift (< 0.5°); the phase estimation bias (< 2°) of the signal extraction algorithm (EWT-Prony); additional safety margin reserved (1.5°).

Protection implementation process

Based on the control scheme of the converter stations on both ends, current signals detected by current and voltage transformers (CT, VT) are gathered and recorded in real time by intelligent electronic devices (IED). The flowchart of the proposed protection scheme is shown in Fig. 18.

Simulation and verification

To evaluate the correctness of the protection scheme proposed in this paper, a simulation model of the dual-end weakly-fed AC system is constructed on the PSCAD/EMTDC electromagnetic simulation platform, as shown in Fig. 2. In this model, the rated capacity of the photovoltaic station in the dual-end weakly-fed AC system is 1 MW, with a rated voltage of 6.9 kV. The photovoltaic station is connected to a 35 kV bus through a box transformer, and the voltage is stepped up to 230 kV via a 220 kV voltage level. Finally, the electrical energy is delivered to the flexible direct current (DC) side through a 500 kV transmission line, which is connected to the DC side converter and then fed into the grid system. The transmission line is modeled using a frequency-dependent parameter model, with the relevant information shown in Fig. 19.

The detailed parameters of all key components in the two-terminal weak AC system constructed in this study, including the relevant model settings of photovoltaic power station, MMC converter and AC line, are shown in Table 1 below. The data sampling rate is 4 kHz.

Different fault resistances

Using the grounding fault of a phase at the midpoint of the dual-end weakly-fed AC system line as an example, the performance of the proposed differential protection scheme is evaluated under varying fault resistances (10 Ω, 50 Ω, 100 Ω, 200 Ω, 300 Ω).

As shown in Fig. 20, the protection scheme proposed in this paper shows that with the increase of fault resistance, the phase of the characteristic frequency line model impedance ZH gradually decreases. When the fault resistance is less than 300Ω, the arg(ZH) is greater than threshold value, and internal faults can be accurately detected, with the characteristic frequency line model exhibiting inductive behavior. Therefore, the protection scheme proposed in this paper has anti-fault ability.

As illustrated in Table 2, with an increase in fault resistance, the phase of the faulted phase’s characteristic frequency line model decreases, while the phase of the non-faulted phase’s characteristic frequency line model remains reliably less than threshold value. With the fault resistance increases, the faulted phase’s operating time gradually increases.

In order to evaluate the fault resistance ability of the protection scheme proposed in this paper, the comparative simulation is carried out by using the power frequency model identification protection of the system. Figure 21 shows the operation characteristics of the traditional protection scheme under different transition resistances.

When the transition resistance is 10 Ω, 100 Ω and 300 Ω respectively, according to Fig. 21, when the transition resistance is 10 Ω, the traditional protection can still operate correctly. When the transition resistance is 100 Ω, the model identification protection is at the critical action boundary under the power frequency phasor, and the reliability is significantly reduced. When the transition resistance is 300 Ω, the power frequency phasor protection refuses to operate.

Different fault types

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed protection scheme for various fault types, faults were simulated at the midpoint of the line. The fault types considered were phase-to-ground (ag), phase-to-phase (ab), two-phase-to-ground (abg), and three-phase-to-ground (abcg) faults, including both symmetric and asymmetric faults, along with a phase-to-ground external fault characterized by a fault resistance of 25 Ω. The phase of the characteristic frequency line model and the response time for internal faults under different fault types are shown in Fig. 22.

As shown in Fig. 22, when different types of internal faults occur, the characteristic frequency line model phase of the faulted phase exceeds the threshold value, ensuring reliable operation. In contrast, the characteristic frequency line model phase of the non-faulted phases remains much smaller than threshold value, ensuring reliable non-operation. Therefore, the protection scheme proposed in this paper demonstrates excellent operational performance.

As shown in Table 3, the characteristic frequency line model phase of the three phases during internal faults and the action time of the faulted phase are presented. In the event of an internal fault, all faulted phases exceed threshold value within a very short time, satisfying the protection criterion. Moreover, the response time of the faulted phase for all internal faults listed in the table is less than 30 ms. The protection criterion proposed in this paper ensures operation within a very brief time, to satisfy the high-speed operation requirement of main protection systems for high-voltage transmission lines.

To further assess the proposed protection’s capability to reliably and accurately differentiate between internal and external faults, faults of A-phase ground fault (ag) with different fault resistances (10Ω, 50Ω, 100Ω, 200Ω, and 300Ω) are set within the protected line for verification and analysis.

As shown in Fig. 23, when external faults occur with different fault resistances, the characteristic frequency line model phase of the faulted phase is always smaller than the action threshold, ensuring reliable operation.

As shown in Table 4, the phase of the characteristic frequency line model and the operating time of the faulted phases for the external fault are presented. In the case of an external fault, all faulted phases remain below threshold value, satisfying the protection criterion. No maloperation occurs, which demonstrates the reliability of the proposed protection scheme.

Different fault locations

The protection scheme proposed in this paper aims to assess the reliability of the protection system at various fault locations. An a-phase grounding fault is used as an example, as shown in Fig. 24.

As shown in Fig. 24, for different fault resistances and fault locations, the characteristic frequency line model phase of the faulted phases remains greater than threshold value. This verifies the effective operating characteristics of the protection scheme proposed in this paper.

As shown in Table 5 when different fault types occur in various fault segments and with different fault resistances within the protected line, the phase of the characteristic frequency line model for the faulted phases is greater than threshold value, while the phase of the characteristic frequency line model for the non-faulted phases is less than threshold value. Therefore, no matter how the fault resistance or fault section changes, the proposed protection scheme can correctly identify the fault. The simulation results further verify the superiority of the proposed scheme.

The impact of different control strategies on protection

Since the power supply characteristics are influenced by the converter control strategy, it is further verified that the proposed algorithm remains unaffected by the power supply characteristics when different control strategies are applied in the dual-end weakly-fed AC system. Therefore, the verification is conducted under various control strategies for the converter stations on both sides of the dual-end weakly-fed AC system. As in27, the negative sequence current suppression control strategy (NCS) on the MMC side under the traditional control strategy is converted to negative sequence voltage suppression control strategy (NVS), and an improved strategy, such as control coordinated strategy of step-down voltage control and negative sequence voltage suppression (CCS-SVC-NCS), is proposed and compared with the control coordinated strategy of step-down voltage control and control coordinated strategy of step-down voltage control and negative sequence current suppression (CCS-SVC-NVS) from28. Using the SPG fault as an example, Table 6 presents a comparison of the sensitivity coefficients and protection times for different control strategies.

As shown in Table 6, the protection algorithm performs consistently under various control strategies. This indicates that the proposed algorithm is unaffected by the power supply characteristics.

The impact of different noises on protection

Considering the impact of external noise and transformer transmission errors on the protection principle in practical applications, this paper employs random Gaussian white noise to assess the anti-interference capability of the proposed principle. To evaluate the noise immunity of the protection scheme, noise levels of 45 dB, 40 dB, 35 dB, 30 dB, and 25 dB are systematically added to the fault current data. Taking the single-phase grounding fault at internal fault F2 and external fault F1 as examples, fault resistances of 10Ω, 50Ω, 100Ω, 200Ω, and 300Ω are selected for verification. Figure 25 illustrates the protection line’s response to internal and external faults under varying noise levels.

The phase of the internal fault characteristic frequency line model is reliably greater than zero, while the phase of the external fault characteristic frequency line model is reliably less than threshold value. It can be observed that both noise and the fault section have minimal influence on the protection scheme proposed in this paper.

According to Table 7, it can be seen that the protection algorithm can work normally under different noise interference and has high robustness.

Comparison of performance among different improvement schemes

In summary, the performance of the protection schemes is compared: the scheme based on transient high-frequency waveform similarity (references9,10,11,12), the scheme based on active detection (references10,13,14), and the model identification protection scheme (references20,21,22), as shown in Table 8.

As shown in Table 8, the proposed scheme fully incorporates the effects of control strategy, power supply characteristics, and boundary adaptability on protection performance. It demonstrates reliable operation under a fault impedance of 300 Ω and noise interference of 25 dB.

Conclusion

Based on the adaptability of the protection of the conventional model in the dual-end weakly-fed AC system, this paper adopts the idea of control and protection coordination, and uses the active injection signal to fuse its own line model. this paper proposes a line model identification protection scheme for the active the dual-end weakly-fed AC system based on characteristic frequency phase. Based on the comprehensive analysis presented, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

This paper proposes the use of the inner current control loop of the MMC to implement differential mode injection, with a feedback regulation mechanism to enhance the quality of the injected signal. The use of single-ended signal injection effectively avoids uncertainties in power flow caused by the operating modes of the MMC, as it eliminates the need for spatial and temporal coordination between multiple devices. This approach is suited for the dual-ended weakly fed AC system.

-

The proposed scheme utilizes the phase information of the line model at characteristic frequencies, employing a EWT-Prony algorithm. This approach ensures stable extraction of the characteristic frequency phase while mitigating the influence of errors in frequency-dependent parameters or differential terms of the line model, thereby effectively reducing noise interference.

-

The proposed scheme during the fault-ride-through phase takes into full account the control strategy, fault type, and fault severity. The protection scheme does not require the selection of fault phases, and the protection settings are independent of simulation configurations. Validation of the scheme demonstrates that it can withstand high fault impedance (300 Ω) and noise interference (25 dB).

-

The potential impact of series/shunt compensation was examined, and a current compensation method is proposed as a future research direction. Regarding tightly coupled parallel lines, decoupling via phase-mode transformation is considered for future investigation. Furthermore, additional theoretical derivation is still requisite for the arc model. Future work will focus on these boundary scenarios to establish more generalized protection principles.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yang, B. et al. Recent advances in fault diagnosis techniques for photovoltaic systems: A critical review. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 9, 36–59 (2024).

Zhang, T., Yao, J., Lin, Y., Jin, R. & Zhao, L. Impact of control interaction of wind farm with MMC-HVDC transmission system on distance protection adaptability under symmetric fault. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 10, 83–101 (2025).

He, Z. et al. Key technologies and development trends of VSC-HVDC transmission for offshore wind power. Renew. Energy Syst. Equip. 1, 35–49 (2025).

Sun, Y., Zhao, Z., Lu, M. & Li, R. Coordinated fault ride-through strategy for DC faults of photovoltaic grid-connected MMC-HVDC systems. Sol. Energy 296, 113524 (2025).

Alassi, A., Bañales, S., Ellabban, O., Adam, G. & MacIver, C. HVDC transmission: Technology review, market trends and future outlook. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 112, 530–554 (2019).

Samantaray, S. R. & Dash, P. K. Pattern recognition based digital relaying for advanced series compensated line. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 30, 102–112 (2008).

Ma, K., Liu, Z., Bak, C. L. & Chen, Z. Novel differential protection based on the ratio of model error indices in time-domain for transmission cable system. Electric Power Syst. Res. 180, 106077 (2020).

Zhou, B. et al. A novel high-sensitivity time-domain current differential protection scheme for renewable power transmission system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 160, 110083 (2024).

Zheng, L. et al. Cosine similarity based line protection for large scale wind farms part II—the industrial application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 69, 2599–2609 (2022).

Jia, K., Yang, Z., Zheng, L., Zhu, Z. & Bi, T. Spearman correlation-based pilot protection for transmission line connected to PMSGs and DFIGs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 17, 4532–4544 (2021).

Song, W., Lu, C., Lin, J., Fang, C. & Liu, S. A low-quality PMU data identification method with dynamic criteria based on spatial–temporal correlations and random matrices. Appl. Energy 343, 121213 (2023).

Zheng, L., Jia, K., Yang, B., Bi, T. & Yang, Q. Singular value decomposition based pilot protection for transmission lines with converters on both ends. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 37, 2728–2737 (2022).

Yang, Z., Zhang, Q., Liao, W., Bak, C. L. & Chen, Z. Harmonic injection based distance protection for line with converter-interfaced sources. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 70, 1553–1564 (2023).

Soleimanisardoo, A., Kazemi Karegar, H. & Zeineldin, H. H. Differential frequency protection scheme based on off-nominal frequency injections for inverter-based islanded microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 10, 2107–2114 (2019).

Mehdi, A. et al. A systematic review of fault characteristics and protection schemes in hybrid AC/DC networks: Challenges and future directions. Energy Rep. 12, 120–142 (2024).

Shu, H. et al. MMC-HVDC line fault identification scheme based on single-ended transient voltage information entropy. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 141, 107817 (2022).

Liang, Y., Ren, Y., Fan, Z. & Yang, X. Adaptive additional current-based line differential protection in the presence of converter- interfaced sources with four quadrant operation capability. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 151, 109116 (2023).

Liang, Y. et al. Current trajectory image-based protection algorithm for transmission lines connected to MMC-HVDC stations using CA-CNN. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 8, 97–111 (2023).

Liang, Y. et al. Effect of inverter interfaced renewable energy power plants on negative-sequence directional relays and a solution. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 36, 554–565 (2021).

Suonan, J. L., Wang, C. Q. & Jiao, Z. B. A Novel Transmission Line Pilot Protection Principle Based on Frequency-Domain Model Identification of Distributed Parameter. 11th IET International Conference on Developments in Power Systems Protection (DPSP 2012).

Wang, C., Song, G., Kang, X. & Suonan, J. Novel transmission-line pilot protection based on frequency-domain model recognition. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 30, 1243–1250 (2015).

Song, G., Chang, P., Hou, J., Li, W. & Zhang, C. A time-domain distance protection method applicable to inverter-interfaced systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 225, 109806 (2023).

Freitas, C. M., Watanabe, E. H. & Monteiro, L. F. C. A linearized small-signal thévenin-equivalent model of a voltage-controlled modular multilevel converter. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 182, 106231 (2020).

Azizi, A., Akhbari, M., Danyali, S., Tohidinejad, Z. & Shirkhani, M. A review on topology and control strategies of high-power inverters in large- scale photovoltaic power plants. Heliyon 11, e42334 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Active injection pilot protection for distribution network suitable for energy storage access. Electr. Eng. J. Early Access (2025).

Farshad, M. & Sadeh, J. Transmission line fault location using hybrid wavelet-prony method and relief algorithm. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 61, 127–136 (2014).

Shi, L., Adam, G. P., Li, R. & Xu, L. Control of offshore MMC during asymmetric offshore AC faults for wind power transmission. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 8, 1074–1083 (2020).

Hou, J. et al. Improved differential protection for two-terminal weak feed AC system considering negative sequence control coordination strategy. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 164, 110396 (2025).

Funding

This work has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52567016,52442705), the Natural Science Fund project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region under (2022D01C662), and the ‘Tianchi Talent Introduction’ program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. H.: Methodology; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Supervision. Writing—original draft; Writing –review & editing. Z. Z.: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Software; Validation; Visualization; Formal analysis. Y. F.: Funding acquisition; Supervision. G. S: Funding acquisition; Supervision. X.W.: Supervision, Formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, J., Zhang, Z., Fan, Y. et al. Active line model identification protection based on characteristic frequency phase for dual-end weakly-fed AC system. Sci Rep 15, 41195 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24860-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24860-5