Abstract

This study proposes a dual-branch framework for precise classification of breast tumor cellularity via histopathological images where it integrates two distinct branches: the Embedding Extraction Branch (embedding-driven) and the Vision Classification Branch (vision-based). The Embedding Extraction Branch uses the Virchow2 transformation to generate dense, structured embeddings, whereas the Vision Classification Branch employs Nomic AI Embedded Vision v1.5 to process image patches and produce classification logits. Both branches’ outputs are combined to form the final classification. The framework also suggests Knowledge Block with fully connected layers, batch normalization, and dropout to improve feature extraction and reduce overfitting. The proposed approach reports high performance metrics, with an accuracy of \(97.86\%\), specificity of \(99.29\%\), and sensitivity, precision, and F1 score of \(97.86\%\). Also, ablation studies show the mandatory role of the embedding extraction branch; as its removal drastically reduces accuracy to \(25\%\). Furthermore, the Vision Classification Branch contributes significantly and its removal aims to a smaller decrease in the accuracy performance (\(95.75\%\)). Additionally, data augmentation improves model performance and its exclusion results in a notable decline in accuracy performance (\(89.37\%\)). The approach’s robustness is validated through statistical analysis that reports low variance and high consistency across multiple performance metrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is a global cancer and traditional diagnostic modalities (e.g. mammography, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging) are used in its early diagnosis1,2. But they can give false positives or negatives which require biopsies and histopathological examination (currently the gold standard for BC diagnosis as well as tumor characterization)3,4. Histopathological image analysis (HIA) which is the analysis of tissue samples via hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemical techniques, however manual interpretation of whole slide imaging (WSI) is difficult due to tissue and observer variability causing variability in diagnosis5,6,7. Artificial intelligence (AI) improves HIA through computerized tissue grading and classification, minimizes interobserver variability and enhances diagnostic accuracy8,9. AI can detect tumors, categorize and interact at long distance, pick out subtle patterns that human observers may miss, help in earlier and more consistent BC diagnosis10,11.

Deep learning advancements in recent times have led to convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and vision transformers (ViTs) that provide state-of-the-art performance on the task of medical image classification12. Specifically, ViTs were demonstrated to possess improved capability in capturing long-range dependencies and global context information and therefore are most suited to process intricate histopathological images8. These models can learn hierarchical features at various WSIs scales; supporting precise localization and classification of tumor areas13. Although encouraging, the majority of current approaches rely on either direct classification from raw image patches or feature extraction with subsequent processing where both with inherent drawbacks like loss of spatial information or decreased sensitivity to subtle patterns14,15. High resolution and dimensionality of WSIs (perhaps at gigapixel dimensions) are one of the major obstacles to using AI in histopathology16,17 where it is computationally impossible to process such huge images at such high resolution directly, and hence researchers have been forced to resort to patch-level analysis. Patch-level analysis is fraught with the potential loss of global context, as well as spatial relationships between structures within the tissues18,19. Additionally, morphology heterogeneity and staining artifacts hinder generalization across varied datasets20,21. All these aspects require robust feature encoding methods that are capable of dealing with good local detail and global pattern description within the same analytical framework.

To address the challenges previously discussed, we propose a two-branch architecture that fuses two information paths: (a) extracted embeddings and (b) direct visual classification. The extracted embedding branch employs pre-trained models to yield high-dimensional dense embeddings to maintain tissue patch semantic details; while the other branch employs direct classification via a transformer-based architecture (fine-tuned to adapt to visual patterns across different resolutions). By merging both modalities, our proposed method is spatially coherent and enhances discriminative feasibility, especially in borderline/doubtful instances where small alterations of the cellular pattern could cause a final diagnosis change.

One of the key contributions is the “\(\text {Knowledge~Block}\)” which is the study suggested building block which is used to merge between the two branches by mixing high-level semantic information from the embedding extraction branch and feeding it to the vision classification branch. It is worth noting that adaptive attention-based fusion is the core of that block as it allows the architecture to assign weights to embedded features adaptively based on how much they contribute to classification. As a result the architecture is augmented with high contextual knowledge and interpretability and ultimately results in better diagnostic consistency and less reliance on pathologist’s subjective judgment. The main contributions are:

-

(a)

A dual-branch that merges the embedding extraction and vision-based classification for BC diagnosis.

-

(b)

Fine-tuning two pretrained ViTs: \(\text {Virchow2}\) for embedding extraction and \(\text {Nomic~AI}\)’s Embedded Vision v1.5 for vision classification.

-

(c)

Injection of the “\(\text {Knowledge~Block}\)” to synthesize and enhance information from the embedding extraction branch and hence enhancing the feature representation and classification precision.

The remaining part of the study is split into: “Related studies” provides a summary of the works related. “Materials” provides the specific description of dataset employed in this study. “Methodology” declares the system proposed. “Experiments and discussion” provides the experimental settings and the different experiments and detailed discussions. Lastly, “Conclusions and future directions” concludes the study with future directions suggestions.

Related studies

Breast cancer remains one of the most prevalent cancers in women globally and thus it is an issue that needs new approaches to improving diagnostic performance and speeding up treatment. Sophisticated computational techniques (particularly HIA) has a central mandatory role in improving classification and detection techniques. Existing and recent studies have investigated multiple machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques; achieving remarkable improvement in BC diagnosis2,22. This section reviews literature on those strategies; noting their strengths and limitations as well as gaps warranting the exploration of ViTs as a state-of-the-art approach of diagnosing BC.

Early innovations in histopathological image analysis

Recent attempts to automate the BC diagnosis process have used pre-trained CNNs for feature extraction and classification23,24. For instance, Golatkar et al. designed a DL-based approach using \(\text {InceptionV3}\) to classify H&E-stained breast tissue slides into 4 classes: normal tissues, benign lesions, in situ carcinoma and invasive carcinoma23. By extracting patches based on nuclear density and removing the non-epithelial regions, they got an overall accuracy of \(85\%\) and \(93\%\) accuracy in discriminating between non-cancerous and malignant instances. That targeted patch extraction method showed that focusing on informative regions improves classification. Similarly, Spanhol et al. applied CNNs to the BreaKHis dataset and got patient-level and image-level accuracies of \(90\%\) and \(89.6\%\) respectively24; and their work showed that CNNs can be used in histopathological image analysis and that overfitting is a challenge and large labeled datasets are needed.

Advancements in CNN-based frameworks

Later studies built upon that by advising with more complex/advanced architectures and techniques like Motlagh et al. did with \(\text {ResNet}\) and achieved \(99.8\%\) for benign vs. \(98.7\%\) for malignant sub-categories25. Also, Vang et al. improved performance by merging \(\text {InceptionV3}\) with majority voting ensemble and obtained \(12.5\%\) better than state-of-the-art26. Xiang et al. used data augmentation and fine-tuning on a common benchmark named BreaKHis and reported \(97.2\%\) (patient-level) and \(95.7\%\) (image-level) accuracy27. But CNNs have limitations, first, they are computationally expensive and not suitable for resource constrained environments25. Also, they rely on local pattern recognition and cannot capture global contextual relationships which is required for precise histopathological analysis28.

Hybrid models and transfer learning approaches

To address those challenges, researchers observed hybrid models as shown by Zhou et al. as they suggested a resolution-adaptive network (RANet) merged with an anomaly detection support vector machine (ADSVM)29. That approach removed incorrectly labeled patches during training and hence improving the computational efficiency and achieving multiclass and binary classification accuracies of \(97.75\%\) and \(99.25\%\) respectively. Also, Vesal et al. employed transfer learning with \(\text {InceptionV3}\) and \(\text {ResNet50}\); achieving test accuracies of \(97.08\%\) and \(96.66\%\) respectively for classifying breast histology images30. Vizcarra et al.31 and Kone et al.32 further demonstrated the hybrid models potential where Vizcarra et al. fused shallow learners (SVM) with deep learners (CNN); reporting an accuracy of \(92\%\), surpassing individual model performances. Kone et al. suggested a hierarchical CNN for classifying BC pathologies; reporting accuracies of 99% and 96% on the BACH benchmark and extension datasets respectively.

Emergence of vision transformers (ViTs)

While CNNs dominated the field, their drawbacks prompted the exploration of other architectures as ViTs emerged as auspicious solutions due to their capability to capture long- and short-range dependencies. For example, Thomas et al. used ViTs to the BreaKHis dataset and reported an accuracy of 96% which reflected stability among multiple magnifications33. Also, Zou et al. introduced DCET-Net, a multi-stream framework combining CNNs and transformers; achieving image-level and patient-level recognition rates of 98.79% and 98.77%, respectively34. Wu et al.35 further advanced the field with ScATNet (a multiscale self-attention-based network) where its performance was comparable to that of 187 practicing U.S. pathologists; underscoring its potential for real-world clinical applications. Those studies highlight the growing ViTs importance in overcoming the traditional CNNs limitations and advancing BC diagnosis.

Summary and justification for ViT exploration

Table 1 summarizes the discussed related studies on BC classification and diagnosis. As pointed, notable studies showed state-of-the-art performance; including DCET-Net33 (which employs a dual-stream framework integrating CNN-based local feature extraction and transformer-based global attention) and ScATNet34 (a multiscale self-attention network that fuses hierarchical CNN features with scale-aware transformers to mimic pathologist-like multi-resolution analysis). However, those studies primarily rely on early or mid-level concatenation or attention gating of parallel streams where features from CNN and ViT branches are fused through simple element-wise operations or attention-weighted summation without dedicated semantic refinement. For example:

-

DCET-Net uses parallel convolutional and transformer streams whose outputs are concatenated and passed through shared fully connected layers. It treats both modalities symmetrically and does not accentuate deep semantic abstraction before the fusion.

-

ScATNet introduces scale-aware attention to dynamically weight features across resolutions but still performs fusion at the feature level; lacking a structured mechanism to refine and distill high-level knowledge from one branch before influencing the other.

Instead of fusing raw features from two parallel backbones, our Knowledge Block introduces an asymmetric, knowledge-driven fusion paradigm. We use the Embedding Extraction Branch (Virchow2) to generate dense, pre-trained, high-dimensional embeddings that encode rich histopathological semantics. Those embeddings are not directly fused with visual features; instead they are passed through a dedicated multi-layer refinement module (the Knowledge Block) that applies batch normalization, \(\text {LeakyReLU}\) activation, dropout regularization and cascaded fully connected layers to extract discriminative patterns and generate enhanced classification logits. That knowledge is then added to the vision-based logits from the second branch (Nomic AI’s Embedded Vision v1.5). That way:

-

Semantic knowledge is distilled before fusion, preventing noise propagation and enhancing interpretability.

-

The fusion is adaptive yet lightweight as the contribution of the embedding branch is modulated via learned non-linear transformations rather than static concatenation.

-

The architecture supports modular training and interpretability and hence allowing isolation and analysis of each branch’s contribution (as demonstrated in ablation studies).

Moreover, unlike DCET-Net and ScATNet, which require joint end-to-end training of multiple complex subnetworks, our dual-branch model uses pretrained foundation models (Virchow2 and Nomic Embedded Vision) and focuses on logit-space fusion via a compact, trainable block, significantly reducing training complexity while maintaining superior performance. Thus, the Knowledge Block is not merely a fusion layer but a semantic enhancement unit that transforms pretrained embeddings into actionable diagnostic knowledge, enabling more accurate and robust classification; particularly in ambiguous cases where subtle morphological differences determine tumor cellularity grade.

Materials

We utilized a human BC dataset named Post-NAT-BRCA that can be publicly accessed36. It was developed by the Department of Anatomic Pathology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SBHSC) in Toronto, Canada. It consists of 96 whole-slide images (WSIs) stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Pathologic slides were taken from 54 patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy (NAT)37. Manual annotations of tumor cellularity and cell labels, provided as sedeen annotation files. The dataset classes are low-grade tumor cellularity, medium-grade tumor cellularity, high-grade tumor cellularity, and healthy. The samples from the utilized dataset are presented in Figure 1.

Methodology

The proposed dual-branch AI framework for BC diagnosis (Fig. 2) utilizes both whole slide images (WSIs) and their corresponding annotations to classify between the tissue instances into four distinct categories: Healthy, Low, Medium, and High. The suggested architecture is composed of two complementary branches (the Embedding Extraction Branch and the Vision Classification Branch) which work in parallel to improve diagnostic accuracy by utilizing both semantic embeddings and visual feature extraction.

Mathematically, let \(\mathscr {X} = \{x_i \mid x_i \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\}_{i=1}^{N}\) represent a set of histopathological image patches extracted from WSIs, where H, W, and C represent height, width, and channel count, respectively. Each patch \(x_i\) is associated with a ground truth label \(y_i \in \{0, 1, 2, 3\}\), corresponding to the classes: healthy, low-grade, medium-grade, and high-grade tumor cellularity. The framework uses ViTs in both branches due to their superior modeling capacity for long-range dependencies in histopathological data. The processing pipeline proceeds as follows:

-

Image patches are preprocessed using standard normalization and augmentation techniques.

-

In the Embedding Extraction Branch, each patch \(x_i\) is transformed into a structured embedding vector \(e_i \in \mathbb {R}^d\), where d denotes the embedding dimension.

-

In the Vision Classification Branch, the same patch \(x_i\) is processed through a vision transformer to produce a class-aware visual feature vector \(v_i \in \mathbb {R}^k\), where k is the output feature dimension.

-

A novel Knowledge Block synthesizes the embedding \(e_i\) into enhanced logits \(l_i^{emb}\).

-

Vision-based logits \(l_i^{vis}\) are computed directly from \(v_i\).

-

Final classification logits are gathered via the element-wise summation process using \(l_i^{final} = l_i^{emb} + l_i^{vis}\).

-

Class probabilities are derived using the \(\text {SoftMax}\) function via \(p(y_i = c) = \frac{\exp (l_{i,c}^{final})}{\sum _{c'=0}^{3} \exp (l_{i,c'}^{final})}\).

That dual-pathway approach improved the discriminative capability by merging abstract semantic knowledge from pretrained models with direct visual reasoning. To evaluate the separability of the embedded features across the four classes, we applied three dimensionality reduction techniques: t-SNE38, UMAP, and PCA. As shown in Fig. 3 (as some clustering is evident) there is significant overlap between adjacent classes (e.g., Low vs. Medium); highlighting the need for an auxiliary vision-guided pathway to disambiguate such cases.

Embedding extraction branch

The embedding process can be formalized as learning a nonlinear mapping \(f: \mathbb {R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^m\), where n is the dimensionality of the input space (e.g., the number of pixels in an image) and where m is the dimensionality of the lower-dimensional embedded space, with \(m \ll n\). In this framework, the Embedding Extraction Branch processes input batches by first applying the \(\text {Virchow2}\) transformation, a technique specifically designed for large-scale histopathology data.

Let \(\textbf{I} \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\) represent a histopathological image. The ViT-based \(\text {Virchow2}\) model39,40 partitions \(\textbf{I}\) into non-overlapping patches \(\textbf{P} = \{p_j \in \mathbb {R}^{P \times P \times C}\}_{j=1}^{N_p}\), where P is the patch size and \(N_p = \frac{H \cdot W}{P^2}\) is the total number of patches. Each patch is linearly projected into an embedding space \(\textbf{E}_p = \{e_j \in \mathbb {R}^D\}_{j=1}^{N_p}\), where D is the embedding dimension. Positional encodings \(\textbf{E}_{pos} \in \mathbb {R}^{(N_p+1)\times D}\) are added to the patch embeddings to preserve spatial structure; as presented in Equation 1 where \(\textbf{E}_{cls} \in \mathbb {R}^{1\times D}\) is a learnable class token. After passing through multiple transformer layers, the final output includes the class token \(\textbf{E}_{cls}^{final}\), register tokens (ignored in our setup), and patch tokens \(\textbf{E}_p^{final}\).

After passing through 24 transformer layers, the final output layer includes the refined class token \(\textbf{E}_{cls}^{final}\) and patch tokens \(\textbf{E}_p^{final}\). We form the final embedding by concatenating the class token with the mean-pooled patch tokens; as in Eq. (2). To further enrich the representation, we augment this vector with L2-normalized versions of both components, resulting in a total dimensionality of 2560 as in Eq. (3) where \(\bar{\textbf{E}}_p = \frac{1}{N_p} \times \sum _{j=1}^{N_p} \textbf{E}_{p,j}^{final}\). That extended representation preserves both magnitude and directional semantics, improving robustness to staining variations.

Vision classification branch

The Vision Classification Branch serves as the primary visual reasoning pathway in the proposed dual-branch framework as it directly processes raw histopathological image patches through a state-of-the-art ViT, specifically \(\text {Nomic~AI}\)’s Embedded Vision v1.5, which has been pretrained on large-scale general and biomedical image datasets. That branch is responsible for extracting high-level semantic features from the input patches and generating class-aware logits that complement the knowledge-driven embeddings from the other branch.

Let \(\textbf{I} \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\) represent an input histopathological image patch of height H, width W, and channel count C. The ViT-based Embedded Vision v1.5 model first partitions \(\textbf{I}\) into a grid of non-overlapping patches of size \(P \times P\), resulting in a total of \(N_p = \frac{H \cdot W}{P^2}\) patches. Each patch is linearly embedded into a D-dimensional space (using Eq. 4) where \(\textbf{E}_p\) denotes the patch embedding matrix. To keep positional information, learnable positional encodings (\(\textbf{E}_{pos} \in \mathbb {R}^{(N_p + 1) \times D}\)) are added to the patch embeddings, along with a special class token (\(\textbf{E}_{cls} \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times D}\)) (see Eq. 5).

These transformer encoder layers undergo an alternation of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks. Thereafter, the final hidden representation of the class token \(\textbf{T}_{cls} \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times D}\) carries global contextual information aggregated across all patches. In addition, for confident numerical stability and calibration, an L2 normalization (see Eq. 6) was performed and, after this, a fully-connected layer maps the normalized class token into the output logit space (see Eq. 7); here, \(\textbf{W}_{vis} \in \mathbb {R}^{K \times D}\) is the weight matrix, \(\textbf{b}_{vis} \in \mathbb {R}^{K}\) is the bias vector, and \(K = 4\) refers to the number of classes of interest in our study. This branch complements the Embedding Extraction Branch by focusing on direct visual pattern recognition and can therefore capture fine-grained morphological differences that are not encoded in the structured embeddings. The use of a modern ViT architecture also helps the network to learn robust features that are invariant to the various challenges of tissue staining, morphology, and spatial arrangement; hence, it stands out in dealing with the heterogeneity that histopathological images are exposed to.

The knowledge block

The Knowledge Block is a new component introduced in this study to improve the discriminative ability of the Embedding Extraction Branch by synthesizing high level semantic knowledge from dense embedding vectors. This block is a feature refinement module that processes normalized embeddings and generates enhanced classification logits through a series of cascaded transformations to capture complex non linear relationships between features.

Let \(\textbf{e}_i \in \mathbb {R}^{2560}\) denote the structured embedding vector obtained from the \(\text {Virchow2}\) model, where 2560 is the concatenated dimension of the class token and mean-pooled patch tokens. Before being fed into that block, the embedding undergoes L2 normalization \(\tilde{\textbf{e}}_i = \frac{\textbf{e}_i}{\Vert \textbf{e}_i\Vert _2}\). That normalized embedding is then passed through a multi-layer feedforward network consisting of three fully connected (FC) layers interspersed with batch normalization (BN), \(\text {LeakyReLU}\) activation, and dropout regularization. Each transformation can be described as in Eq. (8) where \(\textbf{W}_1 \in \mathbb {R}^{1024 \times 2560}, \textbf{W}_2 \in \mathbb {R}^{512 \times 1024}, \textbf{W}_3 \in \mathbb {R}^{4 \times 512}\) are weight matrices, \(\textbf{b}_1, \textbf{b}_2 \in \mathbb {R}^{1024}, \mathbb {R}^{512}\) are bias vectors, \(p=0.5\) denotes the dropout rate applied to prevent overfitting, and \(\textbf{l}_i^{emb} \in \mathbb {R}^4\) represents the final logit vector corresponding to the four diagnostic classes (Healthy, Low, Medium, High).

Each component of the Knowledge Block has a mandatory role:

-

Fully Connected (FC) Layers learn the hierarchical representations by mapping the input features domain to higher-order abstractions; and the usage of decreasing dimensions (i.e., \(2560 \rightarrow 1024 \rightarrow 512 \rightarrow 4\)) benefits the architecture to compress information while preserving class-discriminative patterns.

-

Batch Normalization is applied after each FC layer as it normalizes the activations across the batch dimension and therefore accelerating training and improving generalization.

-

LeakyReLU Activation introduces a small negative slope (unlike standard ReLU) for negative inputs and hence preventing neuron saturation and enabling better gradient flow during backpropagation.

-

Dropout Regularization randomly deactivates the neurons during training encourages robustness and reduces dependency on specific feature pathways and hence enhancing model reliability.

Additionally, the \(\text {Knowledge~Block}\) is followed by a “\(\text {Patch~Augmentation~Layer}\)” that operates stochastic spatial and color transformations to the input image patches/tiles where that included random horizontal & vertical flipping (with \(50\%\) probability), rotation (up to \(45^\circ\)), and translation (within \(10\%\) of the image dimensions). Therefore, they can increase data diversity and the model’s capability to generalize across the unseen variations of histopathological data. By using both structural regularization and dynamic feature learning, the “\(\text {Knowledge~Block}\)” improves the “\(\text {Embedding~Extraction~Branch}\)” representational efficiency where its outputs are merged with those from the “\(\text {Vision~Classification~Branch}\)” via element-wise summation (see Eq. 9) followed by a \(\text {SoftMax}\) normalization function (see Eq. 10) to get the corresponding class probabilities. That integration confirms that both abstract semantic knowledge (from the pretrained embeddings) and direct visual reasoning (from the raw pixel analysis) contribute to the final diagnosis and hence they can enhance the classification precisions and robustness compared to single-branch approaches (as confirmed by our ablation studies).

Performance metrics and evaluation

The model’s performance was assessed via key metrics (including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, the F1 score, and an average score) with experiments conducted on two GPU devices running Windows 11 and utilizing Python and libraries such as PyTorch, Timm, and transformers. The loss function used was cross-entropy loss (defined as \(\mathscr {L}_{CE} = -\frac{1}{M} \times \left( \sum _{i=1}^{M} \sum _{c=1}^{C} \left( y_{i,c} \times \log (\hat{y}_{i,c})\right) \right)\)) where \(y_{i,c}\) represents the ground truth and where \(\hat{y}_{i,c}\) is the predicted probability for class c.

Overall pesudocode

In this section we show a high level pseudocode of the proposed dual-branch framework (see Algorithm 1) for breast tumor cellularity classification. It has two branches: (a) the Embedding Extraction Branch and (b) the Vision Classification Branch. The former uses the \(\text {Virchow2}\) transformer to extract structured embeddings from histopathological image patches, the latter uses \(\text {Nomic~AI}\)’s Embedded Vision v1.5 to extract visual features from the same patches. Those feature representations are then processed independently through normalization layers, then a “\(\text {Knowledge~Block}\)” in the embedding branch which is composed of fully connected layers, batch normalization, \(\text {LeakyReLU}\) activation and dropout to enhance feature learning and regularization. Finally the classification logits from both branches are summed element wise and passed through a \(\text {SoftMax}\) layer to get the final class probabilities. That pseudocode summarizes the forward pass of the dual-branch architecture and hence the integration of vision transformers and knowledge driven enhancement for BC diagnosis.

Experiments and discussion

The experiments were conducted on two GPU devices, each with 4 GB of GPU memory, 128 GB of RAM, and running Windows 11. Both devices had identical software versions. The experiments were implemented via Python, with key libraries such as PyTorch, Timm41, and Transformers42. The settled configuration included a batch size of 32, a total of 250 epochs, and a patch size of \(256 \times 256\) pixels. Testing was performed 10 times, and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for the results. The dataset was split 85% for training and 15% for testing.

Quantitative analysis

Table 2 summarizes the performance of the proposed approach for BC classification with several ablation studies conducted to evaluate different aspects of the suggested architecture where each ablation study involves removing or modifying certain components of the approach to understand their contribution to the overall performance. They are (1) the removal of the “patch augmentation” layer, (2) the removal of the embedding branch, and (3) the removal of the vision branch. The proposed approach achieves a notably high level of performance, with an accuracy of 97.86% and a specificity of 99.29%. The high specificity reflects the model’s capability to correctly identify true negatives that is critical to avoid false positives.

The sensitivity, precision, and F1 score are all reported at 97.86% which indicate that the model is well balanced in terms of its ability to correctly identify positive cases (sensitivity) and maintain precision, which is mandatory for minimizing false positives. The average performance metric is 98.15% which further demonstrating the robustness of the model. The confusion matrix (see Fig. 4) also confirms the model’s performance which highlights its ability to classify the four tumor cellularity classes accurately while identifying specific areas of misclassification (which provides valuable insights for further refinement). On the other hand when data augmentation is removed the performance drops significantly on all the metrics (89.37% accuracy and 96.46% specificity) so it seems to have a big impact on the models ability to generalize to unseen data. Removing the embedding branch drops the performance drastically with the model getting only 25% accuracy and sensitivity. That means the embedding branch is capturing the mandatory features needed for classification. Without that branch the specificity is 75% and precision and F1 score is N/A so its clear that this branch is essential in the model architecture. Removing the vision branch causes a smaller drop in performance (accuracy drops to 95.75% and sensitivity and specificity are still high at 95.75% and 98.58% respectively). That means the vision branch is contributing to the models performance but the embedding branch is more important.

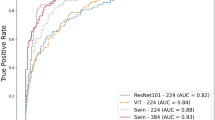

Complementing that confusion matrix, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (see Fig. 5) shows the model’s exceptional discriminative capability across all classes with area under the curve (AUC) values approaching 1.0 for each category (particularly for Healthy and High-grade categories). That near-perfect separation confirms the model’s capability to assign high confidence scores to correct classes while effectively suppressing incorrect ones. Similarly, the Precision-Recall Curve (PRC) (Fig. 6) maintains high precision even at elevated recall levels, especially for the minority classes, demonstrating the model’s resilience against class imbalance and its capacity to reliably detect critical pathological states without sacrificing specificity. Together, these figures substantiate the quantitative metrics reported in Table 2; offering visual confirmation of the model’s superior generalization and calibration.

PRC showing the trade-off between precision and recall for each tumor cellularity class. The reported high precision maintained at increasing recall levels (particularly for minority classes) confirms the model’s robustness to class imbalance and its capability to reliably detect clinically significant cases with minimal false positives.

Qualitative analysis

To further examine the consistency (and variability) of the suggested approach and its ablated variants, we plotted Fig. 7 to present box plots (depicting the distributions of key performance metrics across all experimental runs); while Fig. 8 highlights the critical contribution of each component. These illustrations show a visual discrimination between our proposed method and the ablation studies, which is supported by differences in the central tendency, spread, and hence possible outliers. For instance, the proposed approach reports tight interquartile ranges and high median value scores in all metrics, thus emphasizing its robust and consistent performance. On the contrary, the ablation studies (particularly the removal of the embedding branch) show an unusually wide distribution, a greater dispersion of outliers, low median scores, thus indicating comparatively low stability and diminished classification accuracy. These results confirm the importance of merging both the vision-based and embedding-based branches in order to reach optimal diagnostic performance.

Statistical analysis

To find out how important the differences in our results between the complete model and the ablation studies are, we performed some statistical tests: (a) bootstrap resampling, (b) non-parametric hypothesis testing, and (c) goodness of fit to distribution. The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1 scores were collected with 1000 bootstrap resamples (with replacement) across 10 runs/trials, and showed high precision in bootstrap estimates because: (a) the SE for all metrics under the full model is \(< 0.0025\). (b) \(95\%\) CI(s) are quite narrow (e.g., accuracy: \([97.85\%, 97.87\%]\)); this much higher consistency. (c) the “No Data Augmentation” version has wider CI(s) (e.g., accuracy: \([89.36\%, 89.38\%]\)) and higher values of SE (\(\sim 0.005\)); more variability than generalization.

As we used a small number of independent trials (\(n = 10\)), we applied the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare between the paired performance scores where all comparisons yielded \(p < 0.001\); confirming that performance degradation from removing any component (especially data augmentation or the embedding branch) is statistically significant. We assessed normality using the Shapiro–Wilk and Anderson–Darling tests. Results indicate: (1) the proposed method yields normally distributed results for all metrics (\(p > 0.05\)), supporting parametric inference. (2) the “No Data Augmentation” variant shows non-normal distributions (\(p \le 0.05\)), suggesting instability. (3) Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) tests further validate fit to normal distribution where KS result for full model accuracy: \({KS}_{test}(statistic=0.2437; p_{value}=0.4593)\) and Good Fit to Normal Distribution (\(p > 0.05\)). In contrast, ablated studies deviate significantly (\(p < 0.01\)). Additionally, Anderson–Darling analysis confirms that.

To reduce sensitivity to outliers, we computed trimmed mean (\(10\%\)) and Winsorized mean (\(10\%\)) and found (1) Full model: Trimmed mean accuracy = \(97.85\%\), closely matching arithmetic mean (\(97.86\%\)). (2) No Augmentation: Trimmed mean = \(89.34\%\); showing slight downward skew due to low-performing outliers. Those findings corroborate the visual evidence in Fig. 7 (box plots), where the full model shows tight interquartile ranges and minimal outliers, whereas ablated configurations exhibit greater dispersion.

Ablation studies

The \(\text {Virchow2}\) model generates embeddings of dimension 2560 by concatenating class tokens and mean-pooled patch tokens. We evaluated lower-dimensional projections via PCA (see Table 3) to assess sensitivity to embedding size. Finding: Performance degrades monotonically as dimension decreases and hence confirming that high-dimensional semantic encoding is mandatory. The decline from \(97.86\%\) to \(91.43\%\) at 256-D shows information loss during compression. Moreover, we tested deeper configurations (see Table 4) while keeping the output dimension fixed at 4 (for 4-class BC cellularity). Finding: Three layers achieve optimal balance between representational power and overfitting and by adding a fourth layer slightly reduces performance (this is likely due to vanishing gradients or excessive complexity relative to BC cellularity experiment size).

We tested the non-linearities used in the literature (see Table 5) in the 3-layer configuration (\(2560 \rightarrow 1024 \rightarrow 512 \rightarrow 4\)). Result: \(\text {LeakyReLU}\) outperforms others (especially ReLU) and this means that preserving small negative activations helps gradient flow during training; especially with sparse embedding inputs. We tried different dropout rates (see Table 6) after each FC layer. Result: 50% dropout is optimal and lower values lead to overfitting and higher values to underfitting (because of signal suppression in the narrow final layers). We tested batch normalization (BN) (see Table 7) after each FC layer. Result: BN helps both accuracy and stability (lower standard error) and hence faster convergence and less internal covariate shift.

General Findings: Our ablation confirms that the chosen configuration (\([FC(2560 \rightarrow 1024) \rightarrow BN \rightarrow LeakyReLU \rightarrow Dropout(0.5)] \times 3 \rightarrow Output(4)\)) is good for several considerations: (a) high input dimension (2560) retains histopathological semantics, (b) three FC layers provide enough non-linearity without overfitting, (c) \(\text {LeakyReLU}\) is used for gradient flow, (d) \(50\%\) dropout maximizes generalization, and (e) batch normalization stabilizes training. Thus, confirming the Knowledge Block is not a random stack but a carefully devised semantic distilling unit that turns pre-trained embeddings into diagnostic knowledge.

Comparative analysis with state-of-the-art methods

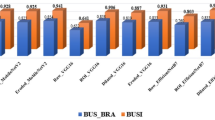

We compared between our suggested dual-branch architecture and state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods43,44,45,46,47,48 including CNNs and Vision Transformers (ViTs). The baselines (\(\text {ResNet50}\), \(\text {EfficientNet-B4}\), \(\text {Swin-Tiny}\), \(\text {ViT-Base/16}\), \(\text {DeiT-Base}\), and \(\text {ConvNeXt-Base}\)) that are widely used in medical image analysis, were trained and evaluated under the same conditions using the same data splits, preprocessing, augmentation and optimization (as our suggested architecture). As shown in Table 8, our approach shows the best accuracy (\(97.86\%\)) and specificity (\(99.29\%\)) and that outperforms the strongest baseline (\(\text {ConvNeXt-Base}\)) by \(+1.43~\text {pp}\) in accuracy. The statistically significant improvement (\(p < 0.001\), Wilcoxon signed-rank test across 10 runs) means our knowledge-driven fusion strategy has a real merit over single-pathway and fusion-based models. That gain is from the domain-specific semantic knowledge (via \(\text {Virchow2}\)) and high-resolution visual reasoning (via \(\text {Nomic~AI}\)) merging; and hence led to more robust classification (especially for ambiguous instances between medium and high cellularity grades). Therefore, our suggested approach is not only consistent but also better than current studies (a big step forward in AI-driven BC diagnosis).

Distinction from our earlier studies

This study builds upon and significantly improves our earlier milestones49,50,51 in BC diagnosis by introducing the dual-branch framework that integrates embedding-driven and vision-based classification and hence marking a pivotal advancement over previous milestones. In Balaha et al.49, we introduced a CAD framework integrating state-of-the-art ViTs with 2-Tier Majority Fusion (MF) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP); achieving diagnostic accuracy exceeding 97% and robust interpretability through SHAP. While that study showed superior performance on the BreakHis dataset, this study further refines interpretability and diagnostic precision by utilizing embedding extraction via \(\text {Virchow2}\) and hence allowing dense and structured representations of histopathological features. Furthermore, in Balaha et al.50, we suggested a framework merging feature extraction, selection, and classification using Support Vector Machines (SVM) and multi-level ViTs; achieving an impressive accuracy of 98.88% on the BreakHis dataset. The current study complements and extends that work by replacing SVMs with \(\text {Nomic~AI}\)’s Embedded Vision v1.5 in the vision-based branch; resulting in enhanced classification capabilities and reducing reliance on traditional ML techniques. That dual-branch architecture ensures high-contextual knowledge integration that further improving diagnostic consistency and mitigating interobserver variability.

Finally, Sabry et al.51 showed a multi-resolution ViT-based framework with ensemble decision-making, addressing limitations of single-magnification models by extracting multiscale features at three magnification levels. While that study achieved promising accuracy (97.08%) and robustness, the current work advances that foundation by using embedding-driven analysis alongside multi-level vision classification. That dual-track approach not only captures fine-grained and high-level tumor characteristics but also improves interpretability and adaptability to diverse morphologies and hence setting a new benchmark for BC diagnosis frameworks. By synthesizing those improvements (embedding-driven analysis, dual-branch integration, and advanced interpretability); this study represents a significant leap forward in BC diagnosis; offering a more comprehensive, precise, and clinically reliable solution compared to our earlier studies.

Computational efficiency and deployment feasibility

We have conducted assessment of our model’s computational efficiency; including inference latency, memory footprint, parameter count, and throughput under realistic conditions. All measurements were performed on a standardized hardware platform: an NVIDIA RTX A2000 12GB, Intel Core i9-12900 CPU, and 64 GB RAM, using PyTorch with mixed precision (FP16) enabled. For WSI processing, our pipeline operates at the patch level due to the gigapixel scale of histopathology slides. On average, a single WSI from the dataset yields approximately 1200 patches (\(256 \times 256\) pixels). The proposed dual-branch framework processes these patches in batches of 32. We measured an average per-patch inference time of 18.7 ms, resulting in a throughput of \(\approx 53.5\) frames per second (FPS) across both branches. When aggregated to the WSI level, the total inference time averages \(\approx 36.2\) seconds per slide, excluding I/O overhead. This is clinically feasible, as it enables near-real-time decision support during diagnostic workflows.

Knowledge Block \(\approx 2.8\) much smaller than the end-to-end configurations such as DCET-Net(\(\approx 40\)M) or ScATNet(\(\approx 35\)M). Peak GPU memory usage during inference was \(\approx 11.4\) GB, well within the limits of modern clinical workstations and edge devices with high-end GPUs. To test for scalability of our systems, we ran them on a low-resource device(i.e., NVIDIA RTX 3060; 12 GB VRAM) and achieved \(\approx 41.2\) FPS (\(\approx 24.3\) ms/patch) with almost no drop in accuracy(\(\approx 97.7\%\)), confirming the robustness on hardware tiers. FLOPS count is \(\approx 22.3\) GFLOPs per forward pass so it is a balance between representational power and computational feasibility.

Medical relevance in enhancing breast cancer diagnosis

The proposed double-branch architecture has medical implications for better BC diagnosis, perhaps in that ViTs and self-attention are more accurate than and consistent with histopathological diagnosis. While histopathological diagnosis of BC is important, it is time consuming and subjective to the extent that it is pathologist dependent. Hence, the proposed combination of vision-based classification and embedding-based analysis would bridge the gap by treating tissue tiles as embedment patch sequences at different magnification levels, the high-level tumor features being captured at low-magnification levels, and the low-level tumor features being captured at high-magnification levels. All this improves the diagnosis and reduces inter-observer variability, a known long-standing issue in clinical practice. Early and accurate detection of BC subtypes is thus the clincher for clinical usability of this work, which in turn can improve patient outcomes and personalized treatment design for individual patients.

Validation by practicing pathologists

We conducted blinded validation experiments with practicing pathologists to render our proposed method clinically useful and feasible. More precisely, histopathological tiles/slides were shown to experienced pathologists who independently evaluated the models predictions as that enabled us to test the framework in real diagnostic scenarios and identify further points to improvement. Comments from pathologists emphasized the requirement for increased interpretability and localizability of outputs against tumor areas, and post-processing techniques (like region-growing and level set fast-marching algorithms)49,50,51 were added (in our earlier studies) to improve predictions in WSI and tumor localization. This serves as proof of our commitment and partnership to build a system that can meet these practical needs for clinicians.

Conclusions and future directions

BC cellularity diagnosis has been carried out using a dual-branch framework which integrates embedding extraction and vision-based classification; where it employed two pre-trained ViTs (here, \(\text {Virchow2}\) model for embedding extraction, and \(\text {Nomic~AI}\)’s Embed Vision v1.5 model for vision-based classification). Overall, the use of these continuous components along with the knowledge block, enables the architecture to capture characteristics both on the local and the global level by which it leads to a better-performing system in diagnoses. The experimental outcomes clearly show that the framework has achieved (\(97.86\%\) accuracy), (\(99.29\%\) specificity), and (97.86% sensitivity); exceeding the traditional means and their ablation variants. Furthermore, the embedding extraction branch provides a mandatory role in capturing well-structured and high-dimensional features, while the vision classification branch is complimentary with visual information. Not least, through the incorporation of augmentation data as well as the block of knowledge, model generalization capacity improves while providing handling of variability seen in histopathological slides. These results indicate the promise of this approach in reducing any interobserver variability and improving diagnostic consistency in BC cellularity diagnosis. There remains, however, much to do in the future. First, the dataset will need to include more demographic/geographic variation to optimize generalizability and equity. Second, the information sharing across multi-modal data (i.e., genomic, radiologic, clinical) can facilitate better diagnosis, as well as a more extensive understanding of BC subtypes being assessed. Third, real-time applications for clinical use allow direct integration into existing digital pathology workflows. Because the next generation of XAI methods will use the model to boost its credibility and interpretability, future research will have to identify and develop such techniques. In building the practical framework and making it clinically applicable, an essential aspect would be working with practicing pathologists. Equally important will be identifying the ethical issues (data privacy, bias reduction, compliance standards) so we can implement AI diagnostic tools in practice safely and ethically.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Post-NAT-BRCA repository, https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/post-nat-brca/.

References

Lukong, K. E. Understanding breast cancer-the long and winding road. BBA Clin. 7, 64–77 (2017).

Ben Ammar, M., Ayachi, F. L., Cardoso de Paiva, A., Ksantini, R. & Mahjoubi, H. Harnessing deep learning for early breast cancer diagnosis: A review of datasets, methods, challenges, and future directions. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 16, 1643–1661 (2024).

Dillon, M. F. et al. The accuracy of ultrasound, stereotactic, and clinical core biopsies in the diagnosis of breast cancer, with an analysis of false-negative cases. Ann. Surg. 242, 701–707 (2005).

Kurita, T. et al. Roles of fine-needle aspiration and core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Breast Cancer 19, 23–29 (2012).

Krithiga, R. & Geetha, P. Breast cancer detection, segmentation and classification on histopathology images analysis: a systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 28, 2607–2619 (2021).

Peregrina-Barreto, H., Ramirez-Guatemala, V. Y., Lopez-Armas, G. C. & Cruz-Ramos, J. A. Characterization of nuclear pleomorphism and tubules in histopathological images of breast cancer. Sensors 22, 5649 (2022).

Jiang, H., Yin, Y., Zhang, J., Deng, W. & Li, C. Deep learning for liver cancer histopathology image analysis: A comprehensive survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108436 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Vision transformers for computational histopathology. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 17, 63–79 (2023).

Parvaiz, A. et al. Vision transformers in medical computer vision-a contemplative retrospection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 122, 106126 (2023).

Niazi, M. K. K., Parwani, A. V. & Gurcan, M. N. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence. Lancet Oncol. 20, e253–e261 (2019).

Sechopoulos, I., Teuwen, J. & Mann, R. Artificial intelligence for breast cancer detection in mammography and digital breast tomosynthesis: State of the art. In Seminars in Cancer Biology, vol. 72, 214–225 (Elsevier, 2021).

Takahashi, S. et al. Comparison of vision transformers and convolutional neural networks in medical image analysis: a systematic review. J. Med. Syst. 48, 84 (2024).

Zhou, C. et al. Histopathology classification and localization of colorectal cancer using global labels by weakly supervised deep learning. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 88, 101861 (2021).

Archana, R. & Jeevaraj, P. E. Deep learning models for digital image processing: a review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 11 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Advances in medical image segmentation: a comprehensive review of traditional, deep learning and hybrid approaches. Bioengineering 11, 1034 (2024).

Greeley, C. Deep Learning Approach to Histology in Gigapixel Tissue Images (Washington State University, 2023).

Bahadir, C. D. et al. Artificial intelligence applications in histopathology. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 93–108 (2024).

Gour, A., Bhanodia, P. K., Sethi, K. K. & Rajput, S. Patch-based medical image classification using convolutional neural networks. In Handbook of Deep Learning Models for Healthcare Data Processing, 258–278 (CRC Press).

Pereira-Carrillo, J. et al. Comparison between two novel approaches in automatic breast cancer detection and diagnosis and its contribution in military defense. In Developments and Advances in Defense and Security: Proceedings of MICRADS 2021, 189–201 (Springer, 2022).

Hou, L. et al. Robust histopathology image analysis: To label or to synthesize? In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 8533–8542 (2019).

Khan, A., Atzori, M., Otálora, S., Andrearczyk, V. & Müller, H. Generalizing convolution neural networks on stain color heterogeneous data for computational pathology. In Medical Imaging 2020: Digital Pathology, vol. 11320, 173–186 (SPIE, 2020).

Rahman, S. Recent advancement on breast cancer detection and treatment. Ph.D. thesis, Brac University (2022).

Golatkar, A., Anand, D. & Sethi, A. Classification of breast cancer histology using deep learning. In Image Analysis and Recognition: 15th International Conference, ICIAR 2018, Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal, June 27–29, 2018, Proceedings 15, 837–844 (Springer, 2018).

Spanhol, F. A., Oliveira, L. S., Petitjean, C. & Heutte, L. Breast cancer histopathological image classification using convolutional neural networks. In 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2560–2567 (IEEE, 2016).

Motlagh, M. H. et al. Breast cancer histopathological image classification: A deep learning approach. BioRxiv 242818 (2018).

Vang, Y. S., Chen, Z. & Xie, X. Deep learning framework for multi-class breast cancer histology image classification. In Image Analysis and Recognition: 15th International Conference, ICIAR 2018, Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal, June 27–29, 2018, Proceedings 15, 914–922 (Springer, 2018).

Xiang, Z., Ting, Z., Weiyan, F. & Cong, L. Breast cancer diagnosis from histopathological image based on deep learning. In 2019 Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC), 4616–4619. https://doi.org/10.1109/CCDC.2019.8833431 (2019).

Xiang, Z. et al. Breast cancer diagnosis from histopathological image based on deep learning. In Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC) (2019).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, C. & Gao, S. Breast cancer classification from histopathological images using resolution adaptive network. IEEE Access 10, 35977–35991 (2022).

Vesal, S., Ravikumar, N., Davari, A., Ellmann, S. & Maier, A. Classification of breast cancer histology images using transfer learning. In Image Analysis and Recognition: 15th International Conference, ICIAR 2018, Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal, June 27–29, 2018, Proceedings 15, 812–819 (Springer, 2018).

Vizcarra, J., Place, R., Tong, L., Gutman, D. & Wang, M. D. Fusion in breast cancer histology classification. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics, 485–493 (2019).

Koné, I. & Boulmane, L. Hierarchical resnext models for breast cancer histology image classification. In Image Analysis and Recognition: 15th International Conference, ICIAR 2018, Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal, June 27–29, 2018, Proceedings 15, 796–803 (Springer, 2018).

Thomas, A. M., Adithya, G., Arunselvan, A. & Karthik, R. Detection of breast cancer from histopathological images using image processing and deep-learning. In 2022 Third International Conference on Intelligent Computing Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT), 1008–1015 (IEEE, 2022).

Zou, Y., Chen, S., Sun, Q., Liu, B. & Zhang, J. Dcet-net: Dual-stream convolution expanded transformer for breast cancer histopathological image classification. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 1235–1240 (IEEE, 2021).

Wu, W. et al. Scale-aware transformers for diagnosing melanocytic lesions. IEEE Access 9, 163526–163541. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3132958 (2021).

Martel, A., Nofech-Mozes, S., Salama, S., Akbar, S. & Peikari, M. Assessment of residual breast cancer cellularity after neoadjuvant chemotherapy using digital pathology. The Cancer Imaging Archive (2019).

Peikari, M., Salama, S., Nofech-Mozes, S. & Martel, A. L. Automatic cellularity assessment from post-treated breast surgical specimens. Cytometry A 91, 1078–1087 (2017).

Sainburg, T., McInnes, L. & Gentner, T. Q. Parametric umap embeddings for representation and semisupervised learning. Neural Comput. 33, 2881–2907 (2021).

Zimmermann, E. et al. Virchow 2: Scaling self-supervised mixed magnification models in pathology. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.00738 (2024).

Vorontsov, E. et al. Virchow: a million-slide digital pathology foundation model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.07778 (2023).

Wightman, R. Pytorch image models. https://github.com/rwightman/pytorch-image-models. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4414861 (2019).

Wolf, T. et al. Transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, 38–45 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. CoRRabs/2103.14030 (2021). arxiv:2103.14030.

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Touvron, H. et al. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 10347–10357 (PMLR, 2021).

Liu, Z. et al. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 11976–11986 (2022).

Balaha, H. M., Ali, K. M., Gondim, D., Ghazal, M. & El-Baz, A. Harnessing vision transformers for precise and explainable breast cancer diagnosis. In International Conference on Pattern Recognition, 191–206 (Springer, 2025).

Balaha, H. M., Ali, K. M., Mahmoud, A., Ghazal, M. & El-Baz, A. Integrated grading framework for histopathological breast cancer: Multi-level vision transformers, textural features, and fusion probability network. In International Conference on Pattern Recognition, 76–91 (Springer, 2024).

Sabry, M. et al. Enhancing breast cancer diagnosis with multi-resolution vision transformers and robust decision-making. IEEE Access (2025).

Funding

This research partially supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project Number (PNURSP2025R40), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balaha, H.M., Mahmoud, A., Ali, K.M. et al. Embedding-driven dual-branch approach for accurate breast tumor cellularity classification. Sci Rep 15, 41058 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24877-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24877-w