Abstract

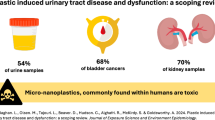

The pervasive environmental presence of polyethylene microplastics (PE-MPs) raises growing concerns about their potential systemic toxicity, particularly in renal physiology. This study investigated the nephrotoxic effects of PE-MPs, focusing on renal function, oxidative stress, mitochondrial integrity, and histopathological outcomes. Male Wistar rats were orally administered PE-MPs at 15 and 60 mg/kg body weight daily for 28 days. Renal function biomarkers, electrolyte levels, oxidative stress markers, mitochondrial enzyme activities, and histological changes were assessed using standard biochemical assays and H&E staining. PE-MPs exposure resulted in dose-dependent elevations in serum creatinine, BUN, uric acid, cystatin C, ACR, and KIM-1, indicating glomerular and tubular dysfunction. Oxidative stress was evidenced by depleted antioxidants (AA, GSH, SOD) and elevated MDA, NO, and MPO. Mitochondrial bioenergetic enzymes and respiratory complexes were significantly suppressed, suggesting impaired bioenergetics. Histological analysis revealed progressive glomerular atrophy, tubular degeneration, and interstitial inflammation. Electrolyte imbalance (hyponatremia, hypochloremia, hyperkalemia) further confirmed disrupted ion homeostasis. Exposure to PE-MPs induces dose-dependent renal injury through oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired renal function. These findings highlight the kidney as a critical target of microplastic toxicity and underscore the need for regulatory attention to environmental microplastic exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The kidney is known for its metabolic functions, which include maintaining systemic homeostasis through filtration, electrolyte balance, acid–base regulation, and waste excretion. Its physiological role is associated with energy metabolism; emphatically, the nephron exhibits a specialized bioenergetic profile where the proximal tubules rely heavily on oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid β-oxidation to meet their high adenosine triphosphate (ATP) demands, while the medulla favours glycolysis due to its hypoxic microenvironment1,2. Thus, mitochondrial integrity and the coordinated activity of glycolytic, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and electron transport chain (ETC) enzymes are important for renal function and resilience against injury2,3.

Recent concerns have emerged regarding the toxicological impact of polyethylene microplastics (PE-MPs), a pervasive class of environmental pollutants. PE-MPs are increasingly detected in human tissues and fluids, including blood, urine, and potentially renal parenchyma4. Their small size and physicochemical properties enable systemic distribution and cellular uptake, raising alarms about their bioactivity and potential nephrotoxicity. Experimental evidence suggests that PE-MPs can induce oxidative stress, disrupt ion homeostasis, and impair mitochondrial function, which are all hallmarks of renal injury, and these effects are often mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, depletion of antioxidant defences, and interference with metabolic enzymes, yet the mechanistic landscape remains understudied2,4.

Given the kidney’s role in maintaining ion homeostasis, detoxification, reliance on tightly regulated energy metabolism, and redox balance, it is imperative to elucidate how PE-MPs perturb these systems. This study addresses that need by examining the effects of PE-MPs on renal function, ion regulation, oxidative stress, and bioenergetic processes. We also performed histological analyses to complement the biochemical findings and assess structural integrity. It also provides mechanistic insights into how PE-MPs compromise renal health. By integrating data on antioxidant defences, mitochondrial bioenergetics, and tissue architecture, we contribute to the expanding field of microplastic toxicology. These findings have implications for environmental toxicology, nephrology, and public health, offering evidence to guide risk assessment and inform potential therapeutic strategies for microplastic-induced kidney injury.

Materials and methods

Materials

PE-MPs (34–50 μm) were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat no.434272), Missouri, USA. All biochemical assay kits used in this study were obtained from ElabScience (Elabscience Biotechnology Inc., USA) and included the following: creatinine (E-EL-0058), blood urea nitrogen (BUN; E-BC-K183-S), uric acid (E-BC-K016-S), cystatin-C (E-EL-R0304), albumin (E-EL-R0025), kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1; E-EL-R3019), neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL; E-UNEL-R0040), sodium (E-BC-K207-S), potassium (E-BC-K279-M), chloride (E-BC-K189-M), total protein (E-BC-E002) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; E-EL-M0419). All chemicals utilized were purchased from AK Scientific (AK Scientific Inc., USA) and included mannitol, sucrose, sorbitol, glucose-6-phosphatedehydrogenase, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, succinate, phospohenolpyruvate, oxaloacetate, rotenone, cytochrome c, potassium chloride, and tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane.

Experimental animals, ethical approval, treatment and organ sampling

Fifteen (15) male Wistar rats (8 weeks old; 180–200 g) were housed in the animal facility of Ajayi Crowther University and acclimatized for seven days prior to experimental procedures. The animals were maintained in standard cages under controlled environmental conditions (temperature: 22 ± 2 °C; 12-hour light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to clean drinking water and a standardized pellet diet. Following acclimatization, the rats were randomly assigned into three groups (n = 5 per group). Group 1 (control) received normal saline orally for 28 days, while groups 2 and 3 were administered PE-MPs at doses of 15 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg body weight, respectively, via oral gavage. Doses were based on the study by Farag et al.5. The 28-day exposure period was selected based on established subacute toxicity protocols and aligns with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Test Guideline 407 for repeated dose oral toxicity studies (https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/test-no-407-repeated-dose-28-day-oral-toxicity-study-in-rodents_9789264070684-en.html). This duration is widely accepted for evaluating systemic effects and early toxicological responses to environmental contaminants, including microplastics. All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Natural Sciences, Ajayi Crowther University (FNS/ERC/2024/020HH), and conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Following the final administration of PE-MPs, all animals were fasted overnight and subsequently euthanized under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia. Blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture into plain tubes and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 5 min to obtain serum, which was used for kidney function analysis. Both kidneys were excised, weighed, rinsed in 1.15% ice-cold potassium chloride (KCl), and homogenized in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a ratio of 1:5 (w/v). The homogenate was used for mitochondria isolation following the protocol described by Fernández-Vizarra et al.6. Briefly, the homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000 g for 2 min at 4 °C to isolate the mitochondrial fraction. The resulting pellet was collected and stored at − 40 °C until further analysis.

Biochemical analyses

Renal function, injury biomarkers and electrolyte dysregulation assay

Renal function parameters (creatinine, BUN, uric acid, cystatin-C, and albumin), kidney injury biomarkers (KIM-1 and NGAL), and electrolytes (sodium, potassium, and chloride) were assayed in serum samples using ELISA kits and colorimetric methods according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Absorbance readings for creatinine, cystatin-C, albumin, NGAL, KIM-1, potassium, and chloride were measured using a Tecan Infinite F50 microplate reader at 450 nm, except for chloride, which was read at 460 nm. BUN, uric acid, and sodium were quantified using a T90 + UV/VIS Spectrophotometer (PG Instruments Limited, Beijing, China) at 580 nm, 690 nm, and 405 nm, respectively.

Renal mitochondrial redox status

Renal mitochondrial redox status was assessed by examining the levels of non-enzymic antioxidants namely ascorbic acid (AA), glutathione (GSH), enzymic antioxidants; catalase (CAT), glutathione-S-transferase (GST), superoxide dismutase (SOD), oxidants concentration nitric oxide (NO), malondialdehyde (MDA), and myeloperoxidase activity (MPO) in the kidney mitochondrial fraction using established protocols7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

Glycolytic enzymes activities

The method outlined by Colowick & Schmidt15 was followed to determine hexokinase (HK) activity, Jagannathan et al.16 method was employed to assess aldolase (ALD) activity, lactate dehydrogenase activity (LDH) was determined using the manufacturer’s protocol, and the method described by Kim et al.17 was used to measure NADase activity.

Tricarboxylic enzymes activities

The activity of citrate synthase (CS) was measured by following the method of Nulton-Persson and Szweda18, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) assayed spectrophotometrically according to the protocol described by Romkina and Kiriukhin19, malate dehydrogenase (MDH) activity was determined utilizing Lopez-Calcagno et al.20 method, and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity measured by Jones and Hirst approach21.

Electron transport chain enzymes activities

The functional capacity of the mitochondrial was assessed through the assessment of electron transport chain (ETC) by quantifying the activities of the key respiratory chain complexes (NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I), succinate ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex II0, cytochrome c oxidoreductase (complex III) and cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV)) using the protocol described by Medja et al.22.

Histological analysis

The excised kidney was fixed in neutral buffered formalin for 48 h. Following standard tissue processing, 5 μm-thick sections were prepared using a rotary microtome (Leica RM 2145, Germany). The slides were subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under a Leica DM750 microscope equipped with a digital camera. Histological evaluation focused on the structural integrity of the glomeruli, renal tubules, and Bowman’s capsules, as well as the presence of inflammatory cell infiltration and other pathological features. The histological aberrations were graded as follows: 0 = Normal (no lesion), 1 = Mild (lesion < 25% of field), 2 = Moderate (lesion 25–50% of field), and 3 = Severe (lesion > 50% of field).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., USA; https://www.graphpad.com) employing one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison test to assess intergroup differences. Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Renal injury and ion homeostasis disruption in response to PE-MPs administration

Effect of PE-MPs on renal functions and ion homeostasis is given in Table 1. Exposure to PE-MPs at 15 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg body weight elicited a dose-dependent deterioration in renal function, as evidenced by significant elevations in serum creatinine, BUN, and uric acid levels relative to control (p < 0.05). The 60 mg/kg group exhibited the most pronounced increase, suggesting progressive nephrotoxicity. Notably, serum cystatin C remained unchanged at the lower dose but rose significantly at 60 mg/kg (p < 0.05), indicating compromised glomerular filtration integrity. ACR and KIM-1 concentrations were markedly elevated in both treatment groups, with the highest values observed in the 60 mg/kg cohort (p < 0.05 vs. control and 15 mg/kg), reflecting glomerular leakage and tubular epithelial damage. In contrast, NGAL levels remained statistically unaltered across all groups, suggesting limited sensitivity of NGAL under the present experimental conditions. Electrolyte analysis revealed significant hyponatremia and hypochloremia in the 60 mg/kg group (p < 0.05), accompanied by a dose-dependent rise in serum potassium levels. These findings are indicative of impaired tubular reabsorption and altered ion transport as induced by PE-MPs.

Renal mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation enzymes activities

Glycolytic enzymes

Activities of renal ALD, HK, NADase and LDH activities were assessed to evaluate the potential alterations in glycolytic enzyme functions following PE-MPs exposure (Fig. 1). The mean value of ALD and HK activities did not differ significantly across the experimental groups (p > 0.05). This suggests that exposure to PE-MPs (15 and 60 mg/kg) did not impair the initial steps of glycolysis or fructose metabolism in the renal tissue. However, a significant reduction in NADase activity was observed in the 15 mg/kg bw PE-MPs group compared to controls (p < 0.05), indicating potential disruption in NAD⁺. Interestingly, at 60 mg/kg, no significant change was observed, suggesting a possible compensatory or adaptive response at higher exposure levels. LDH activity exhibited a dose-dependent increase following PE-MPs exposure. The 15 mg/kg bw group showed significant elevations (p < 0.0033), while the 60 mg/kg bw group demonstrated a highly significant increase (p < 0.0001). The upregulated LDH activity may imply an enhanced anaerobic glycolysis or cellular stress responses, potentially linked to hypoxic conditions or mitochondrial dysfunction. Collectively, these findings indicate that while early glycolytic enzymes (ALD, HK) remain unaffected, PE-MPs exposure selectively alters NAD⁺ metabolism and promotes LDH-mediated lactate production, pointing to metabolic reprogramming in renal tissue.

Renal glycolytic enzymatic activities in rats exposed to polyethylene microplastics (PE-MPs) at varying doses (15 and 60 mg/kg bw). Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 5/group) for a aldolase (ALD), b hexokinase (HK), c NADase, and d lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activities in renal tissue. No significant changes were observed in ALD and HK activities across groups, suggesting preserved glycolytic flux. However, NADase activity was significantly increased in the 15 mg/kg and decreased at 60 mg/kg PE-MPs group (*p < 0.05 to ***p < 0.001), indicating potential disruption of NAD⁺ metabolism and redox balance. LDH activity was significantly elevated in the 15 and 50 mg/kg PE-MPs groups (p < 0.05), potentially reflecting a shift toward anaerobic metabolism or compensatory upregulation in response to mitochondrial dysfunction. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Tricarboxylic acid enzymes

Renal tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle enzyme activities were significantly perturbed following oral exposure to PE-MPs (Fig. 2). CS activity showed a marked dose-dependent reduction, with a 2.6-fold decrease in the 15 mg/kg group and a 2.1-fold decrease in the 60 mg/kg group compared to controls (p < 0.0001 respectively), indicating impaired initiation of the TCA cycle. IDH activity also declined significantly, showing a 2.3-fold reduction at 15 mg/kg (p = 0.0372) and a 1.9-fold reduction at 60 mg/kg (p < 0.0001), implying compromised NAD⁺-dependent oxidative decarboxylation and redox imbalance. MDH activity was suppressed by 2.7-fold and 2.2-fold in the 15 and 60 mg/kg groups, respectively (p < 0.0001), reflecting impaired conversion of malate to oxaloacetate and reduced NADH regeneration. Similarly, SDH activity decreased by 2.8-fold in the 15 mg/kg group and 2.3-fold in the 60 mg/kg group (p < 0.0001), indicating potential dysfunction in both the TCA cycle and ETC. Overall, PE-MPs exposure induces significant and consistent downregulation of renal TCA cycle enzyme activities, suggesting mitochondrial bioenergetic impairment.

Renal tricarboxylic cycle (TCA) enzyme activities in rats exposed to polyethylene microplastics (PE-MPs) at varying doses (15 and 60 mg/kg bw). Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 5/group) for a citrate synthase (CS), b isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), c malate dehydrogenase (MDH), and d succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activities in renal tissue. PE-MPs exposure (15 and 60 mg/kg bw) significantly suppressed all four enzyme activities relative to control (*p < 0.05 to ***p < 0.001), indicating impaired TCA cycle flux and mitochondrial dysfunction. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Electron transport chain complexes

Renal mitochondrial respiratory chain complex activities were significantly impaired following oral exposure to PE-MPs (Fig. 3). Complex I activity showed a 2.4-fold reduction in the 60 mg/kg group (p < 0.0001) relative to the control and 15 mg/kg groups, indicating compromised NADH oxidation and electron transfer initiation. However, no significant changes in activity when the control group is compared with PE-MPs at 15 mg/kg group. Complex II activity decreased by approximately 2.2-fold and 1.8-fold in the 15 and 60 mg/kg groups, respectively (p = 0.0037 and p = 0.0019 respectively), suggesting impaired succinate oxidation and FADH₂-linked respiration. Complex III activity was suppressed by 2.5-fold at 15 mg/kg (p = 0.0015) and 2.0-fold at 60 mg/kg (p = 0.0024), indicating reduced ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase function. Notably, complex IV activity exhibited a dose-dependent decline, with a 2.8-fold reduction in the 15 mg/kg group (p = 0.0161) and a 2.3-fold reduction in the 60 mg/kg group (p < 0.0001), indicating substantial disruption of cytochrome c oxidase activity. These findings collectively demonstrate that PE-MPs exposure induces dose-dependent mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction in renal tissue, with significant attenuation of ETC efficiency and potential implications for ATP synthesis and oxidative stress.

Dose-dependent suppression of renal mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes by PE-MPs. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 5/group) for a Complex I, b Complex II, c Complex III, and d Complex IV activities in renal tissue. PE-MPs exposure at both 15 and 60 mg/kg bw significantly suppressed Complex I, II, III, and IV activities compared to control (*p < 0.05 to ***p < 0.001), indicating impaired electron transport chain (ETC) function and reduced oxidative phosphorylation capacity. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Renal mitochondrial redox status perturbation

Renal oxidative stress markers and inflammatory mediators were significantly modulated following oral exposure to PE-MPs (Fig. 4). AA and GSH levels were markedly reduced in both PE-MPs-treated groups compared to controls, with a more pronounced reduction observed at 60 mg/kg, indicating dose-dependent depletion of non-enzymatic antioxidants. CAT activity was suppressed in the PE-MPs groups relative to control, with the 60 mg/kg group showing greater enzyme inhibition, suggesting impaired renal enzymatic detoxification capacity. GST activity showed a dose-dependent increase in the PE-MPs groups relative to the control, indicating an adaptive detoxification response to oxidative stress, reflecting increased conjugation of reactive metabolites for cellular protection. SOD activity also declined significantly in both treatment groups, with a more pronounced reduction observed at the higher dose, reflecting compromised superoxide radical scavenging. In contrast, MDA and NO levels were significantly elevated in PE-MPs-exposed rats, with the 60 mg/kg group exhibiting higher concentrations than the 15 mg/kg group, indicating enhanced lipid peroxidation and nitrosative stress. MPO activity showed a significant downregulation at 15 mg/kg PE-MPs groups compared to control, with a dose-dependent increase between 15 and 60 mg/kg. The initial decrease in MPO activity at 15 mg/kg suggests suppressed neutrophil activation or mild inflammation. Its partial rebound at 60 mg/kg indicates dose-dependent inflammatory re-engagement, yet the activity remains below control levels, implying compromised or dysregulated neutrophil response under escalating oxidative stress induced by PE-MPs exposure. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that PE-MPs exposure induces oxidative and inflammatory stress in renal tissue, with the 60 mg/kg dose exerting more severe biochemical disruptions than the 15 mg/kg dose.

Renal oxidative stress and inflammatory markers following exposure to polyethylene microplastics (PE-MPs). Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 5/group) for a Ascorbic acid (AA), b reduced glutathione (GSH), c catalase (CAT), d glutathione-S-transferase (GST), e superoxide dismutase (SOD), f malondialdehyde (MDA), g nitric oxide (NO), and h myeloperoxidase (MPO) in renal tissue. PE-MPs exposure at both 15 and 60 mg/kg bw significantly reduced antioxidant defences (AA, GSH, CAT, SOD), elevated oxidative stress markers (MDA, NO) and inflammatory enzyme MPO (*p < 0.05 to ***p < 0.001), indicating dose-dependent redox imbalance and renal inflammation. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Histological analysis

Histological examination of H&E-stained kidney sections revealed progressive, dose-dependent nephrotoxic alterations following PE-MP exposure (Fig. 5; Table 2). The control group displayed normal renal architecture, with intact glomeruli, clear Bowman’s spaces, and well-preserved renal tubules (histological score = 0). In contrast, the 15 mg/kg group exhibited mild glomerular shrinkage, tubular epithelial cell swelling, occasional tubular degeneration, and scattered interstitial inflammatory cells, corresponding to a mild-to-moderate injury score (overall score = 1.5). The 60 mg/kg group demonstrated pronounced pathological changes, including glomerular atrophy, collapsed Bowman’s spaces, severe tubular degeneration, and dense interstitial inflammatory infiltrates. These alterations were consistent with severe nephrotoxicity (overall score = 3). The quantitative morphometric analysis (Fig. 5b) provides compelling evidence for dose-dependent glomerular shrinkage following PE MPs exposure, validating our histological observations. The significant reduction in glomerular area from 2850 ± 125 μm² in controls to 2420 ± 98 μm² in the 15 mg/kg group (p < 0.05) and further to 1890 ± 87 μm² in the 60 mg/kg group (p < 0.001) demonstrates a clear dose-response relationship between PE MPs exposure and nephrotoxicity. Collectively, these findings confirm that subacute exposure to PE-MPs induces dose-dependent histoarchitectural disruptions in the kidney, with higher doses producing marked glomerular and tubular injury accompanied by interstitial inflammation.

a Representative photomicrographs of kidney tissue from control and PE MPs-exposed groups. H&E-stained kidney sections from (A) control, (B) 15 mg/kg, and (C) 60 mg/kg PE MPs groups (×400). The control kidney demonstrates (red arrow) normal glomeruli and renal tubules with clear Bowman’s spaces. The 15 mg/kg group exhibits mild glomerular shrinkage, tubular epithelial cell swelling, and occasional interstitial inflammatory cells. The 60 mg/kg group shows (yellow arrow) pronounced glomerular atrophy, tubular degeneration, and dense interstitial inflammation, indicating progressive nephrotoxicity with increasing PE MPs exposure. b Quantitative morphometric analysis of glomerular area in kidney sections from control and PE MPs-exposed rats. Data presented as mean ± SEM (n = 25–30 glomeruli per group from 6 rats/group). Glomerular areas were measured using ImageJ software on H&E-stained sections (×400 magnification). Statistical analysis performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. control; **p < 0.01 vs. 15 mg/kg group.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that oral exposure to PE-MPs at 15 and 60 mg/kg body weight induces dose-dependent nephrotoxicity, as evidenced by kidney function, ion homeostasis, redox status, bioenergetic, and histopathological alterations in the renal tissue. The observed dose-dependent decline in renal function is consistent with emerging evidence linking microplastic toxicity to nephrotoxic outcomes. Elevated serum creatinine, BUN, and uric acid levels in both PE-MPs-treated groups, particularly at 60 mg/kg, reflect impaired glomerular filtration and nitrogenous waste clearance, hallmark indicators of renal dysfunction23. The significant rise in serum cystatin C at the higher dose further supports compromised glomerular integrity, given its sensitivity as an early biomarker of filtration impairment24. The marked increase in ACR ratio and KIM-1 concentrations across both treatment groups suggests glomerular leakage and proximal tubular epithelial damage, aligning with histopathological evidence of structural disruption. Interestingly, NGAL levels remained unchanged, indicating that NGAL may lack sensitivity under subacute microplastic exposure conditions or that its expression is temporally delayed25. While NGAL is widely recognized as a sensitive biomarker for acute kidney injury (AKI), its unchanged levels in our subacute PE-MPs exposure model may reflect several mechanistic and temporal nuances. NGAL expression typically peaks within hours to days following acute tubular stress, making it highly responsive in early-phase injury models26. In contrast, our 28-day exposure paradigm may represent a subacute or progressive insult where NGAL induction is either attenuated or temporally resolved before sampling27. Moreover, microplastic-induced nephrotoxicity may preferentially affect glomerular and proximal tubular structures, as evidenced by elevated cystatin C, ACR, and KIM-1, without triggering the distal tubular stress pathways that robustly induce NGAL28. Additionally, NGAL responsiveness varies depending on the physicochemical nature of the toxicant; certain xenobiotics and environmental pollutants fail to elicit significant NGAL elevation despite histological damage27,28. Thus, the lack of NGAL change in our study may underscore its limited sensitivity in detecting low-grade or compartmentalized renal injury under subacute microplastic exposure, warranting further investigation into biomarker kinetics and site-specific expression. Electrolyte imbalances, including hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and hyperkalemia in the 60 mg/kg group, point to impaired tubular reabsorption and disrupted ion transport mechanisms, likely driven by oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction previously documented in PE-MPs-exposed renal tissue29.

Furthermore, biochemical assays corroborated the histological evidence of oxidative stress and inflammation. PE-MPs exposure significantly depleted non-enzymatic antioxidants, alongside marked suppression of enzymatic antioxidants, and these changes were more pronounced at the higher dose, indicating a dose-dependent compromise in the kidney’s antioxidant defence system. Concurrently, elevated levels of MDA and NO suggest enhanced lipid peroxidation and nitrosative stress, while increased MPO activity reflects neutrophil activation and inflammatory burden29,30.

At the metabolic level, PE-MPs exposure disrupted key mitochondrial and glycolytic pathways. Statistically unchanged activities of the glycolytic enzymes ALD and HK is an indication that early glycolytic flux may be preserved. However, significant downregulation of NADase and upregulation of LDH point to altered NAD⁺ turnover and a shift toward anaerobic metabolism, possibly as a compensatory response to mitochondrial dysfunction. This mitochondrial impairment was substantiated by the suppression of TCA enzymes, these enzymes are central to oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production; their inhibition suggests compromised bioenergetic capacity and redox imbalance31. Furthermore, respiratory chain complex activities (Complexes I–IV) dose-dependent reduction indicated impaired electron transport and reduced mitochondrial efficiency. The most severe decline was observed in Complex IV, which mediates terminal electron transfer to oxygen, underscoring the potential for hypoxic stress and ATP depletion31.

Histological analysis revealed progressive structural damage, ranging from mild glomerular shrinkage and tubular epithelial swelling at 15 mg/kg to severe glomerular atrophy, tubular degeneration, and dense interstitial inflammation at 60 mg/kg. These findings are consistent with previous reports linking microplastic exposure to renal architectural disruption and inflammatory infiltration. The observed reduction in glomerular size may result from capillary loop collapse secondary to endothelial cell swelling and basement membrane thickening, as previously reported in other nephrotoxic models23,24. Additionally, our quantitative findings are consistent with emerging evidence from environmental exposure studies, where microplastic contamination has been associated with reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in human populations32.

While the nephrotoxic effects observed in this study were induced by oral exposure to PE-MPs at 15 and 60 mg/kg body weight, these doses reflect plausible high-end exposure scenarios when scaled to chronic human intake in polluted environments. Environmental surveys have reported microplastic concentrations ranging from nanograms to milligrams per liter in drinking water, seafood, and agricultural produce, with cumulative daily intake estimates reaching 1–5 mg/person/day in highly contaminated regions33,34,35. Although direct extrapolation from animal models to humans requires caution, the dose-dependent renal impairments observed, including glomerular dysfunction, tubular injury, oxidative stress, and bioenergetic compromise, underscore the potential health risks posed by sustained microplastic ingestion. Importantly, the renal biomarkers elevated in this study, such as cystatin C, KIM-1, and ACR, are clinically relevant indicators of early kidney damage in humans, suggesting that even subacute exposure to PE-MPs may contribute to gradual renal decline, particularly in vulnerable populations with pre-existing kidney conditions or high environmental exposure.

Conclusion

Taken together, these data suggest that PE-MPs induce renal toxicity through a multifaceted mechanism involving oxidative stress, inflammatory activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. The histological damage aligns with biochemical evidence of redox imbalance and metabolic reprogramming, particularly at the 60 mg/kg dose. These findings highlight the nephrotoxic potential of microplastics and underscore the need for further investigation into their long-term impact on renal health and systemic metabolism. These insights also contribute to the growing body of evidence on microplastic-induced organ toxicity and emphasize the urgent need for regulatory scrutiny and mitigation strategies to limit human exposure. Environmental policies should prioritize the reduction of microplastic release through stricter controls on plastic manufacturing, improved waste management, and the promotion of biodegradable alternatives. Additionally, routine biomonitoring of microplastic burden in high-risk populations could facilitate early detection of renal impairment. Clinically, antioxidant-based interventions and mitochondrial protective agents may offer therapeutic potential, particularly in individuals with pre-existing renal vulnerabilities. Future translational studies are warranted to validate these strategies and inform evidence-based guidelines for both environmental and clinical risk mitigation.

Limitation

This study was designed as an initial toxicological screening to evaluate the renal effects of PE-MP exposure using biochemical and histopathological endpoints. While these findings provide foundational evidence of renal impairment and oxidative stress, the absence of molecular-level analyses such as gene expression profiling, Western blotting, or immunohistochemistry limits mechanistic interpretation. Future studies are warranted to elucidate the signalling pathways and molecular targets involved in PE-MP–induced renal toxicity.

Although our study demonstrated significant differences between groups using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, the relatively small sample size (n = 5 per group) may have limited the statistical power, particularly for detecting smaller effect sizes. ANOVA generally requires larger group sizes to achieve the recommended power of 0.80, and the Tukey post hoc test is conservative in nature, which may further reduce sensitivity to subtle differences. Consequently, while the observed effects are robust, caution is warranted in interpreting non-significant comparisons, as they may reflect insufficient power rather than the absence of a true effect, and larger sample sizes are recommended for future studies.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Tang, W. & Wei, Q. The metabolic pathway regulation in kidney injury and repair. Front. Physiol. 14, 1344271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1344271 (2023).

Lee, Y. H., Zheng, C. M., Wang, Y. J., Wang, Y. L. & Chiu, H. W. Effects of microplastics and nanoplastics on the kidney and cardiovascular system. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 21, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-025-00971-0 (2025).

Gewin, L. S. Renal tubule repair: is glycolysis good or bad? Kidney Int. 99 (2), 278–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.11.005 (2021).

La Porta, E. et al. Microplastics and kidneys: an update on the evidence for deposition of plastic microparticles in human organs, tissues and fluids and renal toxicity concern. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (18), 14391. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241814391 (2023).

Farag, A. A. et al. Hematological consequences of polyethylene microplastics toxicity in male rats: oxidative stress, genetic, and epigenetic links. Toxicology 492, 153545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2023.153545 (2023).

Fernández-Vizarra, E. et al. Isolation of mitochondria for biogenetical studies: an update. Mitochondrion 10 (3), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2009.12.148 (2010).

Padmanabha, K. K. & Linganna, N. Colorimetric estimation of vitamin C present in fruits. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 4 (1), 283–287 (2017). https://www.ijrar.org/papers/IJRAR19D4950.pdf

Moron, M. S., Depierre, J. W. & Mannervik, B. Levels of glutathione, glutathione reductase and glutathione S-transferase activities in rat lung and liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 582 (1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7 (1979).

Hadwan, M. H. Simple spectrophotometric assay for measuring catalase activity in biological tissues. BMC Biochem. 19, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12858-018-0097-5 (2018).

Skopelitou, K. & Labrou, N. E. A new colorimetric assay for glutathione transferase-catalyzed halogen ion release for high-throughput screening. Anal. Biochem. 405 (2), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2010.06.007 (2010).

Misra, H. P. & Fridovich, I. The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 247 (10), 3170–3175. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)45228-9 (1972).

Guevara, I. et al. Determination of nitrite/nitrate in human biological material by the simple Griess reaction. Clin. Chim. Acta 274 (2), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-8981(98)00060-6 (1998).

Devasagayam, T. P. A., Boloor, K. K. & Ramasarma, T. Methods for estimating lipid peroxidation: an analysis of merits and demerits. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 40 (5), 300–308 (2003).

Hanning, N., De Man, J. G. & De Winter, B. Y. Measuring myeloperoxidase activity as a marker of inflammation in gut tissue samples of mice and rat. Bio-protocol 13 (13), e4758. https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.4758 (2023).

Colowick, S. P. The Hexokinases. In: The Enzymes. Vol. 9 1–48. (Academic Press, 1973). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1874-6047(08)60113-4

Jagannathan, V., Singh, K. & Damodaran, M. Carbohydrate metabolism in citric acid fermentation. 4. Purification and properties of aldolase from Aspergillus Niger. Biochem. J. 63 (1), 94. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj0630094 (1956).

Kim, U. H., Han, M. K., Park, B. H., Kim, H. R. & An, N. H. Function of NAD glycohydrolase in ADP-ribose uptake from NAD by human erythrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1178 (2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4889(93)90001-6 (1993).

Nulton-Persson, A. C. & Szweda, L. I. Modulation of mitochondrial function by hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (26), 23357–23361. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M100320200 (2001).

Romkina, A. Y. & Kiriukhin, M. Y. Biochemical and molecular characterization of the isocitrate dehydrogenase with dual coenzyme specificity from the obligate Methylotroph Methylobacillus flagellatus. PLoS One 12 (4), e0176056. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176056 (2017).

López-Calcagno, P. E. et al. Cloning, expression and biochemical characterization of mitochondrial and cytosolic malate dehydrogenase from phytophthora infestans. Mycol. Res. 113 (6-7), 771–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycres.2009.02.012 (2009).

Jones, A. J. Y. & Hirst, J. A spectrophotometric coupled enzyme assay to measure the activity of succinate dehydrogenase. Anal. Biochem. 442 (1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2013.07.018 (2013).

Medja, F. et al. Development and implementation of standardized respiratory chain spectrophotometric assays for clinical diagnosis. Mitochondrion 9 (5), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2009.05.001 (2009).

Yong, C. Q. Y., Valiyaveettil, S. & Tang, B. L. Toxicity of microplastics and nanoplastics in mammalian systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17 (5), 1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051509 (2020).

Ibrahim, Y. S., Toure, M. & Zhang, Y. Microplastic-induced renal and hepatic toxicity: emerging insights from histopathological and biochemical studies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28 (34), 46812–46825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14688-1 (2021).

Prata, J. C., da Costa, J. P., Lopes, I., Duarte, A. C. & Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: an overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 702, 134455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134455 (2020).

Hong, Y. et al. Advances in the diagnosis of early biomarkers for acute kidney injury: a literature review. BMC Nephrol. 26, 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-025-04040-3 (2025).

Virzì, G. M. et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: biological aspects and potential diagnostic use in acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Med. 14 (5), 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051570 (2025).

Ostermann, M. et al. Biomarkers in acute kidney injury. Ann. Intensive Care. 14, 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-024-01360-9 (2024).

Li, R., Wang, M. & Chen, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in microplastic-induced toxicity: a mechanistic review. Toxicol. Lett. 358, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2022.03.002 (2022).

Wang, Y., Zhang, L. & Liu, X. Oxidative stress and inflammation as key mechanisms in microplastic-induced renal injury. J. Hazard. Mater. 403, 123985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123985 (2021).

Zhang, H., Zhao, Y. & Sun, X. Disruption of mitochondrial respiratory complexes by microplastics: implications for renal bioenergetics. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 98, 104038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2023.104038 (2023).

Dong, C. D. et al. Polystyrene microplastic particles: in vitro pulmonary toxicity assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 385, 121560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121560 (2021).

Heo, S. J., Moon, N. & Kim, J. H. A systematic review and quality assessment of estimated daily intake of microplastics through food. Rev. Environ. Health 40 (2). https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2024-0111 (2024).

Pironti, C. et al. Microplastics in the environment: intake through the food web, human exposure and toxicological effects. Toxics 9 (9), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics9090224 (2021).

World Health Organization. Microplastics in drinking-water. Geneva: WHO. [accessed 26 Sep 2025 ]. (2019). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516198

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the Universiti Driven Research Programme – Future Food, Universiti Putra Malaysia, for their invaluable technical support.

Funding

The research received financial support from the National Science, Research, and Innovation Fund (NSRF), Mae Fah Luang University (Fundamental Fund Grant No. (67A307000040), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Fund from Mae Fah Luang University, Thailand (Contract No. 10/2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Samuel Abiodun Kehinde: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft. Abosede Temitope Olajide: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Sanmi Tunde Ogunsanya: Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. Tolulope Peter Fatokun: Visualization, Software, Methodology. Deborah Itunuoluwa Olulana: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Opeyemi Faokunla: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Folorunsho Adewale Olabiyi: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Tham Chau Ling: Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Sasitorn Chusri: Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kehinde, S.A., Olajide, A.T., Ogunsanya, S.T. et al. Polyethylene microplastics disrupt renal function, mitochondrial bioenergetics, redox homeostasis, and histoarchitecture in Wistar rats. Sci Rep 15, 41120 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24887-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24887-8