Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly utilized to provide real-time assistance and recommendations across a wide range of tasks in both education and workplace settings, especially since the emergence of Generative AI. However, it is unclear how users perceive the trustworthiness of these tools, particularly given the publicized “hallucinations” that they may experience. We conduct a randomized field experiment in an undergraduate course setting where students perform periodic tests using a digital platform. We analyze how subject characteristics affect trust in AI versus peers’ advice. Students are randomly assigned to either a treatment group receiving advice labeled as coming from an AI system or a control group receiving advice labeled as coming from human peers. Our results are in line with recent laboratory experiments documenting algorithm appreciation. However, this effect is moderated by subject characteristics: male and high-knowledge participants place significantly less weight on AI advice compared to peer advice. Notably, these trust patterns persist regardless of advice quality (correct or incorrect). Moreover, our results remain consistent over a four-week period, including after providing performance feedback during the second week, allowing subjects to make more informed trust decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large language models and AI tools, such as ChatGPT, are rapidly transforming how humans interact with technology in educational and professional settings. However, adoption patterns among users remain diverse, raising questions about the psychological underpinnings that shape human-AI interactions, such as trust towards AI systems1,2,3,4. Understanding the determinants of user trust in AI systems is essential to understand varying adoption and usage behaviors. To examine individuals’ trust in AI, we conduct a randomized field experiment within an educational context in an undergraduate class where students take online tests regularly on a digital platform.

In our experiment, we focus on the question of whether individuals are more inclined to rely on AI-generated or human (peer) advice, a question debated in the academic literature, particularly in decision-making contexts. More than four decades of research suggests algorithm aversion, where people prefer human advice over algorithmic recommendations1,2,3,4,5,6. However, recent laboratory experiments indicate a shift in preferences towards algorithmic appreciation, particularly for more complex and more objective tasks2,7,8,9, likely reflecting the improved accuracy and performance of modern algorithms. At the same time, early and largely anecdotal evidence suggests subject characteristics, including knowledge, experience, and personality traits may contribute to variations in AI appreciation9,10.

Our research focuses on two primary factors affecting trust in AI. First, we explore gender differences in AI appreciation. Existing economic literature yields mixed results regarding gender differences in trusting behaviors, although most studies indicate that women trust their peers less than men11,12,13,14. However, it remains an open question whether this pattern extends to trust in AI versus peer advice. The current literature on algorithm reliance finds mixed results for gender15: some studies report that women perceive algorithms as less useful16, while others find no gender differences in algorithm preference17,18. Second, we examine subject knowledge as a driver of AI appreciation. Prior evidence indicates that subjects with greater knowledge and expertise generally exhibit lower levels of trust in advice, irrespective of the source of advice (human or AI)9,13. Knowledgeable individuals often dismiss peer advice, viewing it as inferior to their own knowledge and understanding10. Empirical evidence also indicates that knowledgeable individuals tend to reject AI advice more frequently19. Classic work on clinical versus actuarial judgment demonstrates that experts often rely on their own judgment even when actuarial models outperform them20. Yet whether knowledgeable individuals exhibit differential trust toward AI versus peer advice, that is, whether their trust is source-dependent, remains an open empirical question.

Recent studies exploring AI appreciation rely exclusively on ‘one-shot’ laboratory settings7,8,9. However, previous research highlights the external validity limitations of such environments, noting that many effects documented in laboratories do not extend to real-world settings21,22,23. Moreover, trust is a learning process, and individuals may behave differently once they learn about and get used to the source of advice. Thus, while these experiments capture the dispositional aspect of trust, they cannot capture the dynamic nature of trust (i.e., learned trust)24,25. Consequently, it is unclear whether individuals trust AI advice in field settings as they do in the laboratory.

To address this question, we conduct a randomized field experiment over a four-week period, divided into two distinct phases. The first phase captures subjects’ initial exposure to either peer or AI advice under controlled conditions to ensure internal validity (i.e., the one-shot experiment). The second phase extends over the next three weeks, during which students were allowed to engage in normal classroom interactions between quiz sessions, including discussing course material with peers, while we maintained controlled conditions during the quizzes themselves. This multi-period design better reflects real-world educational settings, while allowing us to observe how trust patterns develop over time. Furthermore, we provide students with performance feedback after the second week of this phase. This research design allows us to assess both the persistence of AI appreciation over time and whether trust patterns remain stable after subjects receive performance feedback.

For our study, we enlisted undergraduate students enrolled in a management course. Students complete tests on an online platform during their weekly lectures, with a significant bonus to their final grade serving as an incentive for participation. We randomly assign students to our treatment group that receives advice labeled as AI or to our control group receiving advice that is labeled peer advice. Through this design, we aim to address the following research questions: Do subjects demonstrate AI appreciation by relying more on AI than peer advice? (RQ1); is AI appreciation moderated by subject gender and knowledge? (RQ2); and do these patterns (AI aversion or appreciation) persist over time and following performance feedback? (RQ3).

We find that subjects place greater weight on AI advice compared to peers’ advice, as measured using Weight on Advice (WOA). However, we find that algorithm appreciation varies with subject knowledge and gender. Specifically, male and high-knowledge participants place considerably less weight on AI advice (Figs. 1 and 2). These results remain stable over time and after providing subjects with performance feedback.

Results

Our field experiment setting is a face-to-face undergraduate management course that meets once a week and includes a digital quiz every meeting. We randomly assign students to either a treatment group, receiving AI-labeled advice, or the control group, receiving peer-labeled advice. These groups remain constant throughout the entire experimental period, and the only difference between them is the label on the advice provided (AI or peer).

The experiment lasts four weeks (four sessions), comprising 82 students who provided 3,667 student-question responses. The first week represents our controlled ‘one-shot’ experiment that allows us to confirm AI appreciation bias observed in recent studies8,9. To explore whether AI appreciation persists over time, we continued the experiment during the remaining three weeks of the course and provided students with performance feedback about their pre-and post-advice performance after the second week. Finally, in the last session, we switched the source of recommendations to capture within subject differences.

Throughout the study, we use two types of questions: numerical questions requiring calculations (e.g., computing financial ratios) and conceptual questions asking students to evaluate management principles (e.g., identifying correct theoretical statements). Examples of both question types are provided in the Online Appendix 1 and 2. We control for question easiness and question type as prior literature indicates that the nature of the task moderates trust in AI, with individuals potentially relying more on advice in tasks of higher difficulty8 or lower subjectivity2. We also control for advice accuracy using a binary indicator of whether the recommendation matches the correct answer. This allows us to account for the possibility that subjects might rely more on accurate recommendations regardless of whether they are labeled as AI or peer advice.

To explore trust differences between AI and peer advice, we focus on advice utilization, a consistently used measure of trust in behavioral studies9,26,27,28. We employ the Judge–Advisor System (JAS)7,8. In this system, subjects can view the advice after their initial answer to a question. After seeing the advice, subjects have the option to revise their answer without any penalty. We then compute the Weight on Advice (WOA), which captures the extent to which subjects incorporate the advice into their revised answers. This measure can be continuous, reflecting partial adoption of advice, or binary, indicating complete switches to match advice exactly.

Task validation and randomization check

We do not find significant performance differences across our treatment and control groups in the quizzes during the pre-experimental period of six weeks (t = 0.22; p-value = 0.826). Furthermore, we document no statistically significant difference in performance between genders in the pre-experimental period (t = 1.26; p-value = 0.213). The gender distribution across our treatment and control groups is balanced. Specifically, out of 41 subjects in the treatment group, 23 are male, while in the control group of 42 subjects, 24 are male. In addition, there is no significant difference across treatment and control groups in their performance on the first attempt answers before receiving the advice (t = -1.21; p-value = 0.229). There is also no significant difference across gender in terms of performance on the first attempt before receiving the advice (t = 1.38; p-value = 0.170). Given that we examine both gender and knowledge as moderators of AI appreciation, we conduct two complementary analyses to verify that these variables are independent in our sample. First, a two-sample t-test shows no significant difference in the probability of being high-knowledge between male and female subjects (p-value = 0.44). Second, regressing subjects’ first-attempt performance at the question level on gender, with controls for question easiness, question type, and quiz fixed effects, yields no significant gender effect (β = 0.052, p-value = 0.16). These analyses suggest that gender and knowledge effects are largely independent in our sample.

We measure knowledge based on subjects’ answers during their first attempts and therefore exogenous to the treatment. To validate this measure, we examine whether high-knowledge subjects outperformed their counterparts in both the pre-experimental phase and the final exam. Notably, high-knowledge subjects exhibited an average performance that is 8.1% points superior to low-knowledge subjects before the experiment (ß = 0.0805; p-value = 0.042), demonstrating a 66.5% accuracy compared to 58.5% for the latter. Furthermore, in the subsequent final exam conducted about one month post-experiment, high-knowledge subjects demonstrated a performance that was 39.45% higher than their low-knowledge counterparts. On average, low-knowledge subjects scored 33.5%, while those with high knowledge scored 46.7%, signifying a 13.2% difference (ß = 0.1320; p-value = 0.003).

Main analyses

We first analyze whether subjects rely differently on AI versus peer-labeled advice. Table 1, column 1, documents that subjects change their answers more often when they receive AI-labeled advice, after controlling for factors that can affect a subject’s reliance on advice (ß = 0.072; p-value = 0.006). Subjects who receive AI-labeled advice revise their responses 7.2% points more than subjects receiving advice from peers, consistent with AI appreciation. We also find a significantly negative effect of task easiness on WOA (ß = -0.361; p-value < 0.001). Task Easiness is measured as the average first-attempt score; thus, lower values correspond to harder tasks. This means that subjects follow the advice more often when the task is more difficult (i.e., when students score fewer points on average in the first attempt). Finally, we also observe that high-knowledge subjects rely on advice to a lesser extent (ß = -0.152; p-value < 0.001).

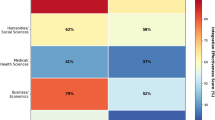

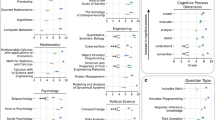

Table 1, column 2 includes the interaction between gender and AI-labeled advice revealing two key findings regarding gender effects. First, the main effect for male subjects is not statistically significant (β = -0.008, p-value = 0.816), indicating no gender difference in trust toward peer advice. Second, we find a significantly coefficient on the interaction term between female gender and AI advice (β = 0.146; p-value = 0.002). That is, female subjects who receive AI advice revise their responses 14.6% points more than female subjects receiving advice from peers. In contrast, male subjects rely on average 12.1% points less on AI advice than female subjects (β = -0.121; p-value = 0.031). Table 1, column 3 includes an additional interaction between high-knowledge and AI advice. We find that low-knowledge subjects who receive AI advice revise their responses 16.1% points more often than low-knowledge subjects receiving advice from peers (ß = 0.161; p-value < 0.001). In contrast, high-knowledge subjects rely 16.8% points less on AI advice compared to low-knowledge subjects (ß = -0.168; p-value = 0.001). Column 4 includes both interactions in a complete model. The magnitude of effects suggests that knowledge (β = -0.155, p-value = 0.003) has a stronger influence than gender (β = -0.099, p-value = 0.076) on AI advice-taking behavior.

Table 2 explores whether AI appreciation and the moderating effects of gender and knowledge persist over time by testing whether our ‘one-shot experiment’ findings hold throughout the entire four-week period of the experiment. We find consistent results regarding all three research questions (i.e., AI appreciation bias, the moderating effects of gender and knowledge). Table 2, Column 1 documents that subjects change their answers 6.1% points more often (compared to 7.2% during the first week) than subjects receiving advice from peers (ß = 0.061; p-value = 0.055), consistent with AI appreciation persisting over time. The interaction between AI advice and gender in Column 2 also supports the results obtained during the first period: male subjects rely 12.8% points less (compared to 12.1% points in the first week) on AI advice compared to female subjects (ß = -0.128; p-value = 0.054). Column 3 confirms that high-knowledge subjects rely 16.3% points less (compared to 16.8% points in the first week) on AI advice (ß = -0.163; p-value = 0.007).

While feedback shows a significant main effect (β = 0.077, p-value = 0.053) in increasing overall advice-taking behavior, the lack of significant interaction with AI advice suggests that feedback affects trust in AI and peer advice similarly. This finding indicates that relative performance feedback influences general advice-taking propensity rather than source-specific trust. This supports the external validity of one-shot lab experiments (e.g., Logg et al., 2019; Bogert et al., 2021) for predicting behavior in real-world settings where subjects can learn and make more informed trust decisions when performance information is shared. Additionally, performance feedback may influence advice-taking propensity differently depending on the relative quality of the advice compared to the subject’s initial answer accuracy. For instance, subjects who consistently outperform the advice may reduce reliance, while those with lower initial accuracy may rely more heavily on advice after receiving feedback. We test this by adding an interaction term between high-knowledge and feedback (see Appendix 4). We find that while feedback significantly increases overall advice-taking propensity (β = 0.147; p-value = 0.009), this positive effect is significantly reduced for high-knowledge individuals (β=−0.135; p-value = 0.022), indicating that feedback helps individuals calibrate their trust in advice more effectively.

In Table 3, we analyze how subjects react when we switch the source of advice (from AI to peer or vice versa) in the last test of the four-week sequence. The gender-specific analyses reveal distinct patterns in how subjects respond to this switch. Female subjects initially show greater trust in AI compared to peer advice (β = 0.149, p-value = 0.035) and significantly reduce their trust when switched to peer advice (β = -0.286, p-value < 0.001). In contrast, male subjects demonstrate initial skepticism toward AI advice (β = -0.120, p-value < 0.061) and show an even stronger reduction in trust when switched from peer to AI advice (β = -0.452, p-value = 0.011). These opposing gender patterns help explain why the aggregate analysis (Column 1) shows more modest effects in the full sample.

To examine whether advice quality affects trust patterns, Table 4 analyzes reliance on correct versus incorrect advice separately. While our main analyses (Tables 1, 2 and 3) control for advice quality to hold it constant across all observations, Table 4 provides an additional test by splitting the sample based on whether advice was correct or incorrect. We create two separate dependent variables: Weight on Wrong Advice (WOWA) and Weight on Correct Advice (WOCA). WOWA takes the value of 1 if the subject follows the wrong advice and 0 otherwise. WOCA takes the value of 1 if the subject follows the correct advice and 0 otherwise.

Our central findings are robust across both correct and incorrect advice. AI appreciation remains positive and significant in both models (WOWA: β = 0.0815, p-value = 0.013; WOCA: β = 0.114, p-value < 0.002). High-knowledge participants consistently show lower reliance on AI advice (WOWA: β = -0.0619, p = 0.064; WOCA: β = -0.0870, p = 0.017), and gender differences remain stable (WOWA: β = 0.0534, p-value = 0.092; WOCA: β = 0.0537, p-value = 0.078). The moderating effects of gender and knowledge are stable in direction and magnitude across specifications. This indicates that the observed effects are not driven by advice quality, but reflect systematic differences in trust toward AI-labeled advice.

Robustness tests

We test the robustness of our findings to the following empirical design choices. First, our results are robust across two different measures of advice-taking behavior. Our primary WOA measure captures nuanced differences in how subjects incorporate advice, including partial adoption of recommendations. For example, in conceptual questions where students evaluate multiple statements, they might adopt some but not all of the recommended changes, reflecting varying degrees of trust in the advice. This approach aligns with prior studies (e.g., Logg et al. 2019), which emphasize the continuous spectrum of advice-taking behavior.

For our first robustness test, we use a binary WOA measure in a robustness test that takes the value of one if the subject changes the answer to match exactly the recommendation and zero otherwise. This provides a more conservative test of our hypotheses, particularly relevant for numerical tasks where partial adjustments are rarely meaningful. For instance, when calculating operating leverage, partially adjusting an answer toward the advised value rarely results in a correct solution – the answer is either right or wrong.

Second, our results are robust to multiple combinations of control variables (e.g., without including other interactions when analyzing gender and knowledge effects; excluding task easiness and/or conceptual task dummy; and using a binary measure of task difficulty). In Appendix 3, we also examine how task characteristics, particularly task difficulty, interact with AI advice. Our findings show that task difficulty (binary measure) significantly influences overall advice-taking behavior – subjects demonstrate higher reliance on both AI and peer advice for more challenging tasks (β = 0.183; p < 0.001). However, we find that the interaction between task difficulty and AI advice is not statistically significant, suggesting that task difficulty does not affect algorithm appreciation in our setting.

Third, we test whether our results are robust to alternative measures of knowledge. Our conclusions remain unchanged if we substitute our knowledge variable with a binary numeracy variable (median split) that measures subjects’ performance on numerical questions, as numerical ability may particularly affect subjects’ trust in algorithmic advice8,9.

Fourth, we verify that our findings are not artifacts of modeling or inference choices. Specifically, we (i) estimate multilevel mixed-effects models with crossed random intercepts for students (to account for individual differences in advice-taking propensity) and questions (to account for question-specific effects on difficulty and advice utility), (ii) re-estimate our models using nonlinear binary choice specifications (logit) based on a binary advice-taking measure (our second WOA measure), and (iii) compute wild cluster bootstrap p-values clustered at the student level (9,999 replications) to address potential small-cluster bias in inference (although few clusters typically means fewer than 20–5029, — we include this test as an additional robustness check). Across all these alternative specifications, reported in Appendix 5, the signs and significance levels of our main coefficients remain substantively unchanged. These results confirm that our conclusions are robust to alternative modeling strategies.

Fifth, we conduct subsample analyses by gender instead of fully interacted regression models. We find no evidence of AI appreciation among males in either the one-shot experiment or the entire experiment. This confirms that AI appreciation is driven primarily by the female subsample. Similarly, subsample analyses using high-knowledge and low-knowledge groups show no evidence of AI appreciation in the high-knowledge subsample for both the one-shot experiment and the entire experiment. In contrast, we document AI appreciation in the low-knowledge subsample.

Sixth, we address potential concerns about sample size. While our study has fewer subjects than many laboratory studies (e.g., Logg et al., 2019), we have a high number of within-subject observations (3,667 across four weeks, averaging 44 per subject). Our power analysis, assuming an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.05, conventional significance level (alpha = 0.05), statistical power (beta = 0.80), and medium effect size (delta = 0.5), indicates that 26 subjects (13 per group) would be sufficient to detect treatment effects. Our actual sample size substantially exceeds this threshold.

Discussion

In light of the rapid development and implementation of Generative AI tools, our study offers timely insight into the psychology of digitalization, particularly in an educational setting. While AI advisors in classroom settings are still atypical, with educators often hesitant to adopt these tools particularly for graded assignments, there is growing integration of AI into education. Platforms like Coursera and other e-learning environments are already using Generative AI agents to deliver personalized feedback tailored to students’ needs and capabilities. Understanding trust dynamics in these contexts is crucial for effective implementation.

We employ a randomized field experiment to explore how the availability of AI advice on digital platforms shapes trust. Our first set of results is consistent with recent laboratory findings on algorithm appreciation in real-world settings, thereby contributing to an understanding of digital adoption and trust dynamics. Furthermore, our analyses reveal that two key demographic variables—knowledge and gender— moderate trust in AI. This highlights the need to tailor AI educational tools to subject characteristics to significantly enhance their effectiveness and ultimately also adoption rates. A more personalized approach to AI could help balance the varying trust levels we observe across different user groups.

We use a randomized field experiment for two reasons. First, a controlled field experiment typically provides higher external validity compared to online experiments while keeping internal validity largely comparable to a laboratory environment21. In our ‘one-shot’ experiment, subjects were randomly assigned to treatment or control groups, with no communication allowed during the test phase to avoid spillovers between groups. In our setting, subjects were unaware of the experiment and should therefore not be influenced by the perception of being in an experiment. Furthermore, subjects have a substantial incentive to perform the task voluntarily and seriously. Notably, we find significantly lower weight on advice in our setting compared to previous laboratory experiments (21% versus 75% in Bogert et al., 2021)8, suggesting that real-world stakes may produce more conservative advice-taking patterns. However, our results are in line with other studies in laboratory settings that typically report WOA between 20 and 40% (e.g., Yaniv 2004).

Second, our findings demonstrate that AI appreciation patterns persists over time and even after subjects receive performance feedback (after the second week). While subjects generally reduced their reliance on advice after learning about its accuracy, the relative preference for AI versus peer advice remained stable. This suggests that advice source influences both dispositional trust (initial inclinations) and learned trust (evolved through experience), which we capture over our four-week experiment24,25. However, we acknowledge that the optimal time frame for trust development remains an open question. Future research could explore longer-term trust dynamics in academic settings across multiple terms or within organizational contexts. Research could also investigate how different types of training and feedback influence trust calibration. Such studies would provide deeper insights into how tailored approaches can help balance trust in AI tools and improve adoption in diverse settings.

In addition, our findings support Logg et al.‘s (2019) conclusions when comparing AI to a group of peers, as opposed to comparing AI to the advice of a single individual9. Consequently, we can infer that AI advice is not only more highly valued than advice from a single peer (as shown by Logg et al. 2019) but also more highly valued than advice from a peer group. However, we find important moderating effects: high-knowledge individuals and male subjects show significantly less trust in AI advice. These patterns persist regardless of advice quality (correct or incorrect) and task difficulty, suggesting they reflect deeper psychological dispositions rather than just responses to performance.

Moreover, our analysis regarding advice quality demonstrates that trust biases (i.e., AI appreciation) persist for both correct and incorrect advice. This underscores the importance of appropriate reliance to avoid both over-reliance and unwarranted skepticism30. Persistent trust patterns suggest that early experiences with AI tools influence long-term adoption, emphasizing the need for careful introduction and feedback to help individuals critically evaluate AI outputs.

Our study also has certain limitations. First, our relatively small sample size reduces statistical power, particularly after clustering the standard errors on the individual subject level to account for correlations in the error terms within individuals over time31. Second, our sample comprises undergraduate management students whose technology exposure may differ from other populations. Third, while our models reveal statistically significant effects, the relatively low R-squared values suggest that a substantial part of the variance in advice-taking behavior remains unexplained. This unexplained variance could stem from unobserved factors such as risk-taking attitudes, confidence levels, prior AI familiarity, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status and norms. Future research could explore these additional determinants of trust and examine longer-term trust dynamics across different educational contexts and populations. Fourth, a limitation of our study concerns the quality of the advice itself. On average, both AI and peer recommendations were correct only about 50% of the time. This moderate accuracy was intentionally chosen to create uncertainty and make the advice-taking decision meaningful. However, this design choice does limit the generalizability of our findings. In real-world applications, AI systems increasingly achieve much higher accuracy rates, which could amplify the AI appreciation effects we observe. Conversely, our findings may not generalize to contexts where algorithmic advice is demonstrably poor. While our analyses control for advice quality and show consistent effects across correct and incorrect advice, future research should systematically examine whether the gender and knowledge moderation effects we document persist across different levels of algorithmic accuracy. This is particularly important in settings where AI substantially outperforms human judgment, as is increasingly common in domains like medical diagnosis and predictive modeling.

Methods

Ethics information

This study was approved by the University of Lausanne ethical committee. Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental design, context, subjects and incentive

Context. Participants are enrolled in the management course that is compulsory in the undergraduate program. Students perform short quizzes (tests) throughout the semester on an online platform during the regular lecture (examples of numerical and conceptual questions are presented in Appendices 1 and 2). Student participation in the quiz is voluntary. However, students have strong incentives to participate as above median performance in the quizzes provides students with a substantial bonus on their final grade (0.5 out of 6 points). Due to these strong incentives, 98% of students participate regularly.

While the observations of the first quiz session (week 1) represent the ‘one-shot’ experiment, we continued the experiment over the following three weeks and performed two additional manipulations. First, after the second week, subjects received feedback on their overall performance. Second, in the last week, we divided the test into two parts. We switched the recommendation source (label) for each subject in the second part of the test to observe within-subject differences. Therefore, subjects initially in the control (treatment) group received AI (peer) recommendations instead of peer (AI) recommendations in the second half of the test. This within subject comparison concerns only the final part of the experiment and (Table 3) is excluded from the main analyses (Tables 1 and 2) in order to keep the advice as a between-subjects’ treatment.

Subjects and Incentives. At the end of the semester, students above the median performance in the tests receive a 0.5 point-bonus out of 6 points on the final grade. Students pass the final exam if they receive a grade of at least 4. Therefore, the bonus represents a high incentive and 94% (98%) of all students participated in the quizzes in the first week (four-week period).

Out of 84 enrolled students, 79 participated in the one-shot experiment, of whom 17 chose not to access the advice provided during the first week (number of observations: 868 from a sample of 62 students). Furthermore, we continued with the same experimental setup during three additional weeks with quizzes to examine whether our findings are stable over time. After the first two weeks, we provided subjects with performance feedback covering their initial attempt performance and their post-advice performance. All subjects either maintained or improved their scores in the second attempt, thus receiving a nudge towards trusting the advice, independent of the advice source. Our dataset for the first session includes 868 student-question observations and the full dataset across all four sessions includes 3,667 student-question observations.

Task and advice

All subjects received 14 (66) independent questions in the first week (in the four-week period), which were provided in a random order and answered consecutively. Out of these questions, 9 (54) were numerical requiring a numerical answer and 5 (12) were conceptual questions that included four short statements in the first week (in the four-week period). For conceptual questions, subjects needed to determine the correct statements and provide a yes/no answer to each one (between zero and four correct statements).

We implemented the Judge Advisor System, where participants initially respond to a question, subsequently decide whether to view the advice, and finally, provide a second answer without any deduction of points or penalty for viewing the advice or changing their answer.

Subjects were randomly assigned to either the group receiving advice labeled as coming from an AI system (treatment group) or the group receiving advice labeled as peer advice (control group). This grouping remained consistent for all questions during the first three weeks, representing a between-subjects condition.

In the instructions, participants in the control group saw an advice source that read: “A frequent answer to this question given by a group of management accounting students was: [Advice]”. Participants in the treatment group saw an advice source that read: “The answer provided by an artificial intelligence*: [Advice].

*An artificial intelligence with various capabilities (such as ChatGPT or BARD) and trained on similar problems.”

We deliberately provided minimal information about the AI system. This general description reflects real-world scenarios where users often interact with AI systems without detailed knowledge of their underlying mechanisms. We chose this approach to avoid biasing students’ initial perceptions of AI.

Students were not aware that they were divided into two groups receiving different types of advice.

We set the accuracy of the advice to 50%. Correct advice was randomly distributed across questions. The advice was the same for both groups, only the labeling of the source of the advice (AI or peers) differing between groups.

Model

We employ ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions to analyze the effects of type of advice, gender, and subject knowledge on weight on advice. We control for advice accuracy and the type of task (conceptual or numerical) and task easiness. Analyses are conducted at the student-question level. We cluster standard errors by subject and question in the multiple period analysis and use robust standard errors within the one-shot experiment29,32. In our one-shot experiment, the average WOA by subjects is 21.0%. To mitigate the influence of outliers we trimmed the data at the 1% level based on subjects’ WOA. This helps to address scenarios in which a subject blindly follows most of the advice given, indicating that the subject may not be taking the task seriously. This procedure results in the exclusion of three participants from our sample. Students who never opted-in to see the advice (i.e., before knowing the advice source) where excluded by default. While this consisted of 17 students in the first week’s one-shot experiment, none of the students were excluded in the full sample). Thus, our final samples include 59 students in the one-shot experiment and 82 in the full experimental period. Our main model (see Table 1) is the following:

where Xij is the vector of control variables (Advice Accuracy, Task Easiness and Conceptual Task Dummy).

Dependent variable

WOA is the weight on advice. It represents a variable that takes the value of ‘1’ if the subject changes their first attempt answer to follow the advice, ‘0’ if the subject did not change their answer and ‘0.5’ if the subject took the average of the advice given and their initial answer. For instance the subject chose answer A in the initial response. After receiving the advice that recommends answers A, B and C, the subject changes the answer to A and B, thus taking the advice only partly into account.

Explanatory variables

Gender is a dummy variable that takes the value of ‘1’ if the subject is male and ‘0’ if the subject is female. Gender was coded based on student names and profile pictures in the university’s learning management system. We acknowledge this binary (male/female) categorization method has important limitations and may not accurately reflect students’ gender identities. While recent statistics indicate that approximately 0.4% of Swiss residents identify as non-binary, our data collection methods did not allow us to capture non-binary gender identities or self-reported gender information.

Knowledge is a proxy for subject’s overall knowledge and is measured using the subject’s overall first attempt performance in the tests. The variable Knowledge takes the value of ‘1’ if the performance is above the median (i.e., high-knowledge) and ‘0’ otherwise (i.e., low-knowledge).

Control variables

Task Easiness is measured at the question level. It represents the average points achieved by all subjects for a question during the first attempt (thus, exogenous to the advice). Therefore, lower values indicate that the task is harder. We find that subjects are 42% less accurate when answering difficult questions (questions for which the difficulty is above the median) during the first attempt (ß = -0.420; p-value < 0.001). Subject accuracy is on average 69.9% for easy tasks and 27.9% for difficult tasks.

Conceptual Task is a binary variable, equal to ‘1’ for conceptual questions and ’0’ for numerical questions.

Advice Accuracy is a a binary variable, equal to ‘1’ if the provided advice is correct and ’0’ if incorrect.

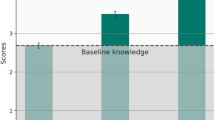

Gender as a moderator of AI appreciation. Week 1 results of the ‘one-shot’ experiment by regressing WOA on treatment dummy, Gender, their interaction plus controls (826 obs.). The left bar (AI advice) represents the treatment effect on the reference group (female subjects). The difference is significant (p-value < 0.01). The right bar (Gender x AI advice) represents the moderating effect of being a male on the treatment effect (AI advice) compared to being a female. The difference across conditions is significant (p-value < 0.05). The confidence interval level is set at 90%.

Knowledge as a moderator of AI appreciation. Week 1 results of the ‘one-shot’ experiment by regressing WOA on treatment dummy, High-knowledge, their interaction plus controls (826 obs.). The left bar (AI advice) represents the treatment effect on the reference group (low-knowledge subjects). The difference is significant (p-value < 0.01). The right bar (High-knowledge x AI advice) represents the moderating effect of being in the high-knowledge group on the treatment effect (AI advice) compared to the reference group for the interaction (low-knowledge subjects). The difference across conditions is significant (p-value < 0.01).

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study, as well as code to conduct analyses, are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Burton, J. W., Stein, M. K. & Jensen, T. B. A systematic review of algorithm aversion in augmented decision making. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 33, 220–239 (2020).

Castelo, N., Bos, M. W. & Lehmann, D. R. Task-Dependent algorithm aversion. J. Mark. Res. 56, 809–825 (2019).

Dietvorst, B. J., Simmons, J. P. & Massey, C. Algorithm aversion: People erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 144, 114–126 (2015).

Dietvorst, B. J. & Bharti, S. People reject algorithms in uncertain decision domains because they have diminishing sensitivity to forecasting error. Psychol. Sci. 31, 1302–1314 (2020).

Dawes, R. M. The robust beauty of improper linear models in decision making. Am. Psychol. 34, 571–582 (1979).

Einhorn, H. J. Accepting error to make less error. J. Pers. Assess. 50 (1986).

Bogert, E., Lauharatanahirun, N. & Schecter, A. Human preferences toward algorithmic advice in a word association task. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–9 (2022).

Bogert, E., Schecter, A. & Watson, R. T. Humans rely more on algorithms than social influence as a task becomes more difficult. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–9 (2021).

Logg, J. M., Minson, J. A. & Moore, D. A. Algorithm appreciation: People prefer algorithmic to human judgment. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 151, 90–103 (2019).

Abeliuk, A., Benjamin, D. M., Morstatter, F. & Galstyan, A. Quantifying machine influence over human forecasters. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–14 (2020).

Dittrich, M. Gender differences in trust and reciprocity: Evidence from a large-scale experiment with heterogeneous subjects. Appl. Econ. 47, 3825–3838 (2015).

Croson, R. & Gneezy, U. Gender differences in preferences. J. Econ. Lit. 47, 448–474 (2009).

Buchan, N. R., Croson, R. T. A. & Solnick, S. Trust and gender: An examination of behavior and beliefs in the investment game. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 68, 466–476 (2008).

Croson, R. & Buchan, N. Gender and culture: International experimental evidence from trust games. Am. Econ. Rev. 89, 386–391 (1999).

Mahmud, H., Islam, A. K. M. N., Ahmed, S. I. & Smolander, K. What influences algorithmic decision-making? A systematic literature review on algorithm aversion. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 175, 121390 (2022).

Araujo, T., Helberger, N., Kruikemeier, S. & de Vreese, C. H. In AI we trust? Perceptions about automated decision-making by artificial intelligence. AI Soc. 35, 611–623 (2020).

Thurman, N., Moeller, J., Helberger, N. & Trilling, D. My friends, editors, algorithms, and I: Examining audience attitudes to news selection. Digit. Journal. 7, 447–469 (2019).

Workman, M. Expert decision support system use, disuse, and misuse: A study using the theory of planned behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 21, 211–231 (2005).

Allen, R. T. & Choudhury, P. Algorithm-Augmented work and domain experience: The countervailing forces of ability and aversion. Organ. Sci. 33, 149–169 (2022).

Dawes, R. M., Faust, D. & Meehl, P. E. Clinical versus actuarial judgment. Science 243, 1668–1674 (1989).

Harrison, G. W. & List, J. A. Field experiments. J. Econ. Lit. 42, 1009–1055 (2004).

Levitt, S. D. & List, J. A. What do laboratory experiments measuring social preferences reveal about the real world? J. Econ. Perspect. 21, 153–174 (2007).

Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Laibson, D. & Madrian, B. C. Does aggregated returns disclosure increase portfolio risk taking? Rev. Financ. Stud. 30, 1971–2005 (2017).

Hoff, K. A. & Bashir, M. Trust in automation: Integrating empirical evidence on factors that influence trust. Hum. Factors 57, 407–434 (2015).

Marsh, S. & Dibben, M. R. The role of trust in information science and technology. Annu. Rev. Inform. Sci. Technol. ARIST 37, 465–498 (2003).

Prahl, A. & Van Swol, L. Understanding algorithm aversion: when is advice from automation discounted? J. Forecast. 36, 691–702 (2017).

Van Swol, L. M. & Sniezek, J. A. Factors affecting the acceptance of expert advice. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 44, 443–461 (2005).

Sniezek, J. A., Van Swol, L. M. & Trust Confidence, and expertise in a Judge-Advisor system. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 84, 288–307 (2001).

Colin Cameron, A. & Miller, D. L. A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. J. Hum. Resour. 50, 317–372 (2015).

Schemmer, M., Kuehl, N., Benz, C., Bartos, A. & Satzger, G. Appropriate reliance on AI advice: Conceptualization and the effect of explanations. In International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Proceedings IUI 410–422 (2023).

Petersen, M. A. Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches. Rev. Financ. Stud. 22, 435–480 (2009).

Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G. W. & Wooldridge, J. M. When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? Q. J. Econ. 138, 1–35 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF Grant 10.002.887 and 220038).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D., D.O., I.E., and N.R. designed the research. D.O., and I.E. carried out the field-experiment. I.E. collected the data and I.E. and N.R. analyzed the data. All authors prepared the manuscript and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dávila, A., El Fassi, I., Oyon, D. et al. Gender, knowledge, and trust in artificial intelligence: a classroom-based randomized experiment. Sci Rep 15, 41066 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25002-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25002-7