Abstract

Generally, the interaction of gestures presents a set of benefits to persons with disabilities, from improving motor, social, and cognitive skills to delivering a secure and controlled atmosphere for engaging in real-world scenarios. Automatic detection methods, such as hand gesture recognition (GR), are among the most active research fields. Hand gestures, particularly in the form of sign language (SL), are one of the effective modes of non-verbal interaction and a stimulating area of research because they can simplify communication and serve as a standard method of communication, employed in a variety of applications. Particularly, GR has received significant attention in the area of Human–computer interaction. Recently, artificial intelligence (AI) technology has been extensively used by scholars to achieve GR and accurate computer vision. Deep learning (DL) is a rapidly evolving technology that aims to simplify a method by which deaf individuals can connect with others. This study presents an Artificial Protozoa Optimiser-Based Fusion of Transfer Learning Models for Enhancing Gesture Recognition (APOFTLM-EGR) model. The APOFTLM-EGR model aims to enhance GR for visually impaired individuals. The image pre-processing stage applies Wiener filtering (WF) to eliminate the redundant or unwanted noise in the input image data. Furthermore, the VGG16, InceptionV3, and ResNet-50 fusion models perform the feature extraction process. The stacked sparse autoencoder (SSAE) technique is employed for the GR process. Finally, the artificial protozoa optimizer (APO) technique optimally adjusts the hyperparameter values of the SSAE method, resulting in improved detection performance. The efficiency of the APOFTLM-EGR method is validated by comprehensive studies using the Indian SL dataset. The experimental validation of the APOFTLM-EGR method delivered a superior accuracy value of 99.46%, outperforming existing models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In general, gestures are essential to human communication, conveying vital data through coordinated movements of the fingers, arms, and hands1. For individuals dependent on SL, gesture-based communication exceeds mere communication; it includes accessibility, independence, and empowerment2. As smart home technology advances, incorporating GR is a favourable method for improving user-gadget communication, specifically for people with restricted mobility or physical disabilities3. GR methods can significantly aid the elderly, those who are unwell, and individuals who are unable to control their equipment through speech. The development of the Internet of Things (IoT) is driven by enhanced human–computer interaction (HCI) to enable device control in various fields, including play, work, education, communication, and health4. A GR method needs a moderate computing source in real-time applications and is operable at a lower cost. Whereas proprietary GR methods were developed, they tended to be single-task oriented, specific to applications, and highly priced. GR methods can be categorized into contactless or contact types5. The communication between computers and humans is expanding extensively, as the field is witnessing constant advancements, with novel approaches being developed and implemented6.

Hand GR (HGR) is the progressive field in which computer vision (CV) and AI are used to enhance interaction with deaf individuals and assist with gesture-based signalling methods7. Subsets of HGR contain SL recognition (SLR), human action recognition, and detection of special signal language with HGR8. Over the years, developers have utilized diverse computational models to address these concerns while extending the lifetime. The utilization of hand gestures in multiple software applications is provided to enhance human–computer interaction9. The modern accomplishment of Machine Learning (ML) and DL methodologies in image classification, speech, object, and human activity recognition has stimulated multiple analysts to utilize them for HGR. For instance, a DL-based Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is used extensively to learn visual aspects of CV10. GR is crucial in creating inclusive technologies that bridge communication gaps for visually impaired individuals. Intuitive interaction with digital environments improves autonomy and assists seamless access to essential services. The advancement of intelligent recognition systems ensures more accurate, responsive, and accessible solutions tailored to diverse user requirements.

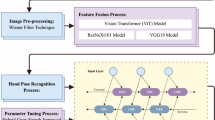

This study presents an Artificial Protozoa Optimiser-Based Fusion of Transfer Learning Models for Enhancing Gesture Recognition (APOFTLM-EGR) model. The APOFTLM-EGR model aims to enhance GR for visually impaired individuals. The image pre-processing stage applies Wiener filtering (WF) to remove redundant or unwanted noise from the input image data. Furthermore, the VGG16, InceptionV3, and ResNet-50 fusion models perform the feature extraction process. The stacked sparse autoencoder (SSAE) technique is employed for the GR process. Finally, the artificial protozoa optimizer (APO) technique optimally adjusts the hyperparameter values of the SSAE method, resulting in improved detection performance. The efficiency of the APOFTLM-EGR method is validated by comprehensive studies using the Indian SL dataset. The key contribution of the APOFTLM-EGR method is listed below.

-

The APOFTLM-EGR model employs the WF method for efficient image pre-processing, thereby enhancing the quality of input images for GR. This technique enhances noise reduction, enabling clearer feature extraction. It improves performance by providing cleaner data for the subsequent DL models.

-

The APOFTLM-EGR methodology performs feature extraction using VGG16, InceptionV3, and ResNet-50. It capitalizes on the capabilities of these pre-trained models to learn complex features effectively. This approach integrates the merits of multiple architectures, ensuring robust and accurate feature representation and improving overall GR accuracy.

-

The APOFTLM-EGR approach utilizes the SSAE-based method for GR, enhancing the model’s ability to learn compact and distinct features from complex data. This method enhances the model’s capability for extracting meaningful representations, ensuring enhanced gesture classification. Concentrating on sparse feature learning improves the model’s efficiency and accuracy.

-

The APOFTLM-EGR method implements the APO technique to fine-tune the hyperparameters of the model, improving overall performance by effectively exploring the parameter space. This optimization ensures the model operates efficiently, thereby enhancing accuracy and facilitating faster convergence. Using APO enhances the model’s adaptability and precision in complex GR tasks.

-

Integrating WF-based image pre-processing with multiple advanced DL models, such as VGG16, InceptionV3, ResNet-50, and APO-based hyperparameter tuning, presents a highly robust GR model. This fusion improves feature diversity and recognition accuracy. The novelty lies in integrating SSAE with multi-model feature extraction and nature-inspired optimization for superior performance.

Literature review

In11, three models for GR and CV were tested and implemented to examine the most relevant one. Each approach, including ML utilizing IMU and ML on a device, was associated with specific actions established during the investigation. In12, a novel deep model-based HGR for Indian Sign Language (ISL) is proposed to facilitate HGR on ISL. The objective of the advanced technique is to achieve proficiency by implementing subsequent stages, such as segmentation, image collection, edge recognition, and detection. Afterwards, the gathered images are moved to the edge detection and segmentation stage, which is implemented using adaptive thresholding-based region growing and Canny edge detection (ATRG-CED). Then, the seed and threshold values of ATRG-CED are enhanced by the modified Tasmanian devil optimizer (MTDO). The authors13 proposed an innovative SLR method named GmTC, intended to translate McSL into corresponding text to improve knowledge. Thus, a general and graph DL model is utilized as dual stream components to remove the effectual aspects. During the primary stream, yield a graph-based aspect by capturing the benefits of superpixel values and the graph convolutional network (GCN), focusing on removing distance-based, complicated relationship attributes between superpixels. In another stream, short- and long-range feature dependencies are removed by employing attention-based contextual data that moves over CNN and multi-stage, multi-head self-attention (MHSA) components. Zholshiyeva et al.14 projected DL approaches that permit you to effectively classify and process hand gestures and HGR technologies for communicating with computers. This work deliberates cutting-edge DL approaches, such as RNN and CNN, that exhibit favourable results in GR challenges. Wang et al.15 introduced a diverse reality method for fully occluded GR (Fog-MR) that assists in the comprehensive removal of hand motion techniques. Initially, a 3D hand pose registration approach for cyber-physical objects is proposed that utilizes BundleFusion for generating a 3D point cloud method. Then, a hand motion aspect of the spectral clustering analysis approach is developed, using a hand reconstruction technique, and relating mutual information metrics to a dual autoencoder network to match hand behavioural objectives accurately. Al Farid et al.16 projected the use of DL approaches to identify automotive hand gestures using depth data and RGB. Any of this type of information might be used to train the NN to recognize hand gestures. Previous analysis endeavoured to describe hand motions in contextual counts. These approaches are evaluated using a vision-based GR method. In the recommended model, image collection begins with depth data and RGB video taken by the Kinect sensor. It is monitored by tracking the hand utilizing a single-shot detector CNN (SSD-CNN).

Ryumin et al.17 developed dual DNN-based method structures: one for AVSR and another for GR. The major innovation in audio-visual speech detection lies in fine-tuning approaches for acoustic or visual aspects, as well as in the projected end-to-end method that deliberates three modality fusion methods: prediction-, feature-, and model-levels. Xi et al.18 enhanced the dynamic GR accuracy by employing an improved ResNeXt-based model with 3D convolutions and a lightweight attention mechanism, facilitating effective spatiotemporal feature extraction. Kabir et al.19 proposed a robust Bangla SL (BdSL) recognition system by utilizing a max voting ensemble of pre-trained deep neural networks (DNNs) such as Xception, InceptionV3, DenseNet121, ResNet50, and MobileNetV2, achieving high accuracy on BdSL-38 and BdSL-49 datasets. Guo et al.20 enhanced emotion recognition in panoramic audio and video virtual reality content by employing a combination of CNN, bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM), and the XLNet-bidirectional gated recurrent unit-attention (XLNet-BIGRU-Attention) model. Zia et al.21 developed a real-time web-based hand/thumb GR model using You Only Look Once version 5 small (YOLOv5s) integrated with Raspberry Pi and Arduino hardware. Chai et al.22 developed the Internet of Things-based Wearable Firefighting Activity Recognition (IoT-FAR) methodology using multi-modal sensor fusion and a hybrid ML network (HML-SVM-RBF1-RF2) technique for accurate recognition of complex firefighting activities during training. Wang et al.23 proposed an automatic scoring method for the "pull-up" test using the dual stream multiple stage framework transformer (DSMS-TF) model, which incorporates a context-aware encoder (CAE), multi-stage attention decoder (MSAD), and scoring modules to assess action quality based on stage-wise video analysis. Rajalakshmi et al.24 developed a hybrid neural network for accurately recognizing static and dynamic isolated Indian and Russian SL using spatial, temporal, and attention-based feature extraction techniques. Sarwat et al.25 proposed a prototypical network-based one-shot transfer learning (TL) model with K-Best feature selection and extended windowing for accurate gesture classification in stroke rehabilitation using EMG, FMG, and IMU sensors. Marzouk et al.26 developed the Automated GR with Artificial Rabbits Optimisation and Deep Learning (AGR-ARODL) technique. This approach integrates median filtering (MF), squeeze-and-excitation ResNet-50, artificial rabbit optimization (ARO), and deep belief networks (DBN) methodologies to improve hand GR accuracy.

Bhavana, Surendran, and Ramya27 improved hand GR through 3D hand pose estimation, enhancing accuracy in applications like human–computer interaction, SL, and motion recognition, utilizing advanced depth sensors to overcome limitations of 2D models. John and Deshpande28 developed a robust hand GR model by using a hybrid deep recurrent neural network (RNN) integrated with chaos game optimization (CGO) for recognizing American SL (ASL) alphabet signs from 2D gesture images. Saranya et al.29 developed an emotion prediction system using CNN for classification, which extracts Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCC) features to detect the driver’s mood or customer emotions, enabling smart automobile control or AI-based customer interactions. Prabha et al.30 developed a GR model for "Rock, Paper, Scissors" using a modified EfficientNetV2-B1 architecture. Balasubramani and Surendran31 developed a DL method by using self-attention-based progressive generative adversarial networks (SA-PGAN) optimized with the gorilla troops optimizer (GTO) technique for early detection of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) through facial emotion analysis. Zhang et al.32 proposed a model by utilizing multimodal sensor data from surface electromyography (sEMG) and pressure-based force myography (pFMG) employing CNNs. Nguyen, Ngo, and Nguyen33 presented a low-cost smart wheelchair system that enhances mobility for individuals with severe disabilities by utilizing the You Only Look Once version 8n (YOLOv8n) model. The method utilizes MediaPipe for pre-processing and landmark extraction, running on an Nvidia Jetson Nano to achieve real-time, accurate control of wheelchair navigation. Sarma et al.34 improved hand GR by integrating semantic segmentation using the UNet architecture with an attention module and using DNNs for classification. Specifically, VGG16 is adapted for static gestures, whereas 3D-CNN or C3D is implemented for dynamic gestures to capture spatial–temporal features effectively. Kadhim, Der, and Phing35 proposed a robust dynamic system for individuals with finger disabilities by combining advanced Otsu segmentation with motion data from RGB video sequences. The approach employs a hybrid model that integrates a CNN with Inception-v3 for feature extraction and LSTM networks for classification. Jalal et al.36 developed a model by fusing features from RGB videos and inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensor data using techniques such as accelerated segment test (ORB), maximally stable extremal regions (MSER), discrete Fourier transform (DFT), and linear predictive cepstral coefficients (LPCC). The unified feature set is classified using ResNet-50 to accurately recognize activities across diverse scenarios.

Kwon et al.37 evaluated the efficiency of benchmark hand GR datasets in training lightweight DL techniques for real-time, robust performance. Yadav et al.38 introduced an efficient GR model by integrating region-based bare hand detection, utilizing skin colour and movement, with TL via AlexNet, followed by a detection and tracking (DaT) approach. The model also utilizes DNNs to accurately recognize 60 isolated dynamic gestures with high precision and improved computational efficiency. Yadav et al.39 enhance bare-hand detection and tracking in uncontrolled environments by utilizing a region-based CNN on a selective region (RCNN-SR), which is integrated with point tracking and Kalman filtering. The model utilizes gesticulated trajectory recognition with prior character information to handle variations in pattern, style, scale, rotation, and illumination for robust GR. Yaseen et al.40 evaluated the efficiency of benchmark dynamic hand GR datasets in training lightweight DL techniques for real-time applications, using metrics to analyze model–dataset interactions. Shin et al.41 The objective of this paper is to provide a comprehensive review of hand GR techniques and data modalities. Marques et al.42 developed ThumbsUp, a gesture-driven mobile HCI system using CNNs, Transformers, and Google’s MediaPipe for real-time “thumbs-up” gesture recognition, supported by adaptive lighting pre-processing and a secure offline–cloud AES-GCM-encrypted synchronization model for efficient, low-resource mobile deployment. Haroon et al.43 reviewed single- and multi-sensor-based Human Activity Recognition (HAR) methods, highlighting recent advances, challenges, and future directions in artificial intelligence (AI)-driven HAR for improved human–computer interaction. Zhou et al.44 presented a multimodal DL technique for sign language recognition (SLR) using multi-stream spatio-temporal graph convolutional network (MSGCN) technique for skeleton features, Deformable 3D ResNet (D-ResNet) for RGB image sequences, and a multi-stream fusion module (MFM) with a gating mechanism to enhance recognition accuracy. Pandey and Arif45 developed MELDER, a real-time Mobile Lip Reader that improves silent speech recognition efficiency on mobile devices through temporal segmentation and TL from high-resource vocabularies. Gao, Ye, and Zhang46 proposed a convolutional neural network–support vector machine (CNN-SVM) emotional perception model to classify emotions like Anger, Neutral, Joy, and Anxiety. Wang et al.47 developed a lightweight wearable electronic glove combined with a Parallel LSTM–CNN (Para-LSTM-CNN) model to simultaneously extract spatial and temporal features for accurate SLR.

The existing studies exhibit various challenges and research gaps. Several models rely on massive datasets, which are often unavailable for languages such as BdSL or ISL, thereby restricting the model’s generalization. Additionally, although some approaches utilize advanced DL techniques such as CNNs integrated with LSTM networks, region-based CNNs, and attention mechanisms, their performance is inconsistent in dynamic environments with diverse users. The research gap comprises the lack of comprehensive solutions that effectively handle diverse hand gestures and SLs in real-world scenarios involving noisy and variable input data. Moreover, limited integration of multimodal sensor data, such as surface sEMG and pFMG, specifically in applications like stroke rehabilitation, restricts classifier accuracy in real-time settings. Existing methods also face difficulty in balancing high accuracy with computational efficiency, particularly for real-time processing on low-cost or embedded hardware platforms.

Proposed methods

This paper proposes a novel APOFTLM-EGR model to enhance GR for individuals with visual impairments. The model comprises distinct stages, including image pre-processing, fusion of TL, gesture classification, and a parameter optimizer. Figure 1 depicts the workflow of the APOFTLM-EGR technique.

WF-based image pre-processing

Initially, the image pre-processing stage applies WF to remove redundant or unwanted noise from the input image data48. This model is chosen for its efficiency in mitigating noise while preserving crucial image details, which is significant for accurate GR. This model adapts to local image statistics, enabling it to perform optimally in varying noise environments. The technique’s capability to improve signal-to-noise ratio enhances the clarity of gesture features before they are sent to DL techniques. This model demonstrates superior efficiency in retaining edge and texture data compared to conventional smoothing filters, which is crucial for discerning subtle gesture patterns. Its mathematical formulation provides an optimal balance between inverse filtering and noise smoothing, making it more reliable for gesture datasets captured in real-world, noisy conditions. This advantage directly contributes to improving the performance of subsequent feature extraction and classification stages.

WF is a method employed to reduce noise in signals, making it chiefly beneficial for tasks involving GR, where sensor data may be distorted or noisy. In GR, raw signals from sensors (such as gyroscopes or accelerometers) are corrupted by various types of noise, which can compromise the accuracy of recognition techniques. The WF functions by assessing the clean signal based on statistical properties, such as the power ranges of the signal and noise. Utilizing this filter smooths the noisy data while preserving the significant features of the gestures, thereby enhancing the accuracy of gesture classification. It is a powerful device for improving signal quality and achieving more reliable results in GR models.

Fusion of TL

Afterwards, the fusion models, namely VGG16, InceptionV3, and ResNet-50, execute the feature extraction process. The three famous TL methods are applied: ResNet-50, VGG-16, and Inception-V349. This fusion model utilizes the merits of renowned TL methods. VGG16 is known for its simplicity and depth, capturing fine-grained spatial features with uniform kernel sizes. InceptionV3 outperforms in extracting multiscale features through its factorized convolutions and inception modules, which enhance efficiency and accuracy. ResNet-50 introduces residual connections that help train deeper networks without vanishing gradient issues, enabling robust feature learning. Integrating these models benefits the system by providing diverse feature representations, thereby enhancing generalization across various gesture types. This fusion outperforms single-model approaches by capturing both low- and high-level semantics, which are crucial for precise GR in intrinsic environments.

VGG16 is a deep CNN structure designed for image classification. Its framework depends on the input size of 224 × 224 pixels of RGB images. It consists of 16 layers, including three fully connected (FC) and 13 convolutional layers. The ReLU activation function is used for each layer. It is designed for the ImageNet dataset and is well-suited for image classification into 1000 classes and object identification from 200 classes. The convolution layer contains 3 × 3 filters with many filters for detecting the image’s composite hierarchical designs. Max-pooling layers of dimension 2 × 2 with a stride of two were applied to remove features, selecting the maximum-valued pixel within all smaller areas. Afterwards, the layers of feature extraction include two FC layers of 4096 neurons, and lastly, there is an FC layer of 1000 neurons for classification.

The 48-layer, deep pre-trained CNN, Inception-V3, was trained on the ImageNet dataset. The network is derived from the input size of 299 × 299 pixels of RGB images. The layered structure of Inception-V3 contains Inception units, whereas all modules are integrated with 1 × 1, 3 × 3, and 5 × 5 convolutions. It has fewer minor parameter counts due to factorization convolutions. Dual 3 × 3 filters substitute a convolution of 5 × 5 filters. In this case, a 5 × 5 filter needs 25 parameters, while a dual 3 × 3 filter needs 18. It will decrease the parameter counts by 28% without compromising the capability to detect patterns using a 5 × 5 filter. Due to this lightweight structure, it is computationally efficient to work on.

ResNet-50 is a typical deep CNN structure, part of the residual networks (ResNet) family, designed to address the vanishing gradient problem in deep networks by presenting residual blocks. It was initially given. ReLU activations, convolutional layers, skip (residual) connections, and batch normalization comprise this 50-layer deep method. There are numerous residual blocks in all four major phases of the process. All residual blocks in ResNet-50 contain a shortcut connection, which skips multiple or single layers, allowing the gradient to pass back through the network without vanishing. They include three convolutional layers with 1 × 1, 3 × 3, and 1 × 1 convolutions. The last FC layer in ResNet-50 usually takes 1000 output elements for 1000 classes in the ImageNet dataset, on which the method was initially trained. Nevertheless, ResNet-50 is adapted to process several classes by fine-tuning the output component counts in the last layer. This change is ordinary in TL, while the network is modified to various datasets with more or fewer classes. Figure 2 depicts the framework of ResNet-50.

GR process using SSAE

For the GR process, the SSAE technique is employed50. This model is chosen because it can learn hierarchical, abstract, and sparse representations from intrinsic input data. SSAE outperforms in capturing nonlinear patterns and underlying structures within gesture features, making it ideal for handling discrepancies in hand poses, lighting, and background. Unlike conventional classifiers, SSAE performs unsupervised feature learning and supervised classification, presenting a compact and discriminative feature space. Its sparsity constraint promotes effectual encoding, which improves generalization and mitigates overfitting. Unlike shallow models, SSAE more effectively recognizes complex gesture patterns, particularly when integrated with TL-based features.

Stacked autoencoder networks comprise stacked structural elements, commonly referred to as Autoencoders (AEs). Conventional AES mostly contain decoding and encoding phases and a symmetrical architecture. When there are numerous hidden layers (HLs), the encoder and decoder phases comprise an equivalent number of HLs. The encoder and decoder methods are defined as in Eqs. (1) and (2).

whereas \({b}_{1}\) and \({w}_{1}\) characterize the encoder biases and weights, \({b}_{2}\) and \({w}_{2}\) represent the decoder biases and weights, \({\sigma }_{e}\) indicates the commonly applied nonlinear conversion, namely Relu, Tanh, and Sigmoid, amongst others, and \({\sigma }_{d}\) specifies the identical affine or nonlinear conversion used in the encoder procedure. Conventional AEs training by reducing the error of reconstruction \(L(x,y)\). The loss function is \((W, b) = \sum L\left(x,y\right)\). Besides communicating the error of reconstruction between \(x\) and \(y\), organized as the mean square error (MSE), as expressed in Eq. (3), cross-entropy may also serve as an alternative, as explained in Eq. (4).

The encoder and decoder procedure mentioned above does not include the input data’ label information; thus, conventional AEs are categorized as unsupervised learning techniques.

According to classical AEs, traditional enhanced AEs contain sparse AE, convolutional AE, shrinkage AE, and so on. Sparse AEs limit the average activation value of outputs of HL neurons derived from conventional AEs; most of the HL neurons’ output attains a sparse result within the network. The penalty term is delineated as Eq. (5).

whereas \({\widehat{\rho }}_{j}\) characterizes the average activation value of concealed components for \(m\) samples, \({s}_{2}\) refers to hidden neuron counts in the HL, and the index \(j\) characterizes all neurons in the HL in order. The penalty term is the relative entropy amongst dual Bernoulli Random Variables with \(\rho\) and \({\widehat{\rho }}_{j}\) as the means. Consequently, the sparse AE’s loss function is stated as Eq. (6).

Here, \(\beta\) is applied to control the weighting of the sparse penalty term, allowing for the simulation of values within the interval of \(0\) to 1. The lower \(\rho\) is, the more powerful the inhibitory effect, and it generally takes a value near \(0.\)

The SSAE is a DNN consisting of numerous sparse AE structural elements. It employs the greedy layer-by-layer approach for training all AE models unsupervised, iteratively initializing the parameters of all layers, stacking the NNs of all layers, and converting them into a deep supervised feed-forward NN, fine-tuning each parameter based on the supervision conditions. As the layer counts of sparse AEs increase, the learned feature representation of the novel data becomes more abstract. Sparse AEs can learn the main characteristics of source data, revealing typical patterns and characteristics, reducing data sizes, utilizing sparse data coding, and showcasing outstanding noise resistance and generalization performance. The input data processing in a stacked AE proceeds successively, layer by layer, with all NN layers removing changing levels of features from the raw data. Features attained in the advanced NN layers stay continuous despite varying features. In addition, the network’s learned function incorporates a high level of nonlinear operational mixtures, enhancing its ability to tackle complex problems and develop robustness. This enables the model to generalize well across diverse data distributions. As a result, it maintains high performance even in dynamic and unpredictable cybersecurity environments.

APO-based parameter optimiser

Ultimately, the APO approach optimally adjusts the SSAE model’s hyperparameter values, giving improved detection performance51. This model is chosen due to its adaptive search mechanism inspired by protozoa behaviour, which effectually balances exploration and exploitation. Unlike conventional optimizers like grid or random search, APO dynamically adjusts search directions, resulting in faster convergence and better global optima. It is appropriate for complex, high-dimensional optimization problems such as DL model tuning. APO avoids premature convergence by replicating the environmental interactions of protozoa, ensuring diverse solution space coverage. APO presents an enhanced solution stability and precision with lower computational overhead compared to other metaheuristics, such as PSO or GA. This makes it highly effective for optimizing GR model parameters. Figure 3 specifies the steps involved in the APO model.

Derived from natural protozoa, it is a meta-heuristic model tailored explicitly for engineering optimization. Inside the flagellates, the representative Euglena is identified as a protozoan. This method uses the Euglena survival strategy, imitating their generative, dormancy, and foraging behaviours. This nature-inspired approach is essential for the model’s design. The three behaviours mimic the protozoa’s survival strategy; the initial one is a foraging behaviour that combines heterotrophic and autotrophic modes.

Once the protozoa are vulnerable to higher light intensities during this autotrophic manner, they move towards places with low light intensities for the \(jth\) protozoan. This is modelled mathematically in Eqs. (7–12).

\({X}_{i}\) and \({X}_{i}^{new}\) specify the original and updated location of the \(ith\) protozoan. \({X}_{j}\) refers to the \(jth\) protozoan selected at random. An arbitrarily chosen protozoan choice in the \(kth\) paired neighbour whose rank index is lower than \(i\) was specified by \({X}_{k}-\). In detail, when \({X}_{i}\) is \({X}_{1},\) \({X}_{k-}\) is moreover fixed as \({X}_{1}.{X}_{k+}\) mentions a protozoan selected randomly in the \(kth\) paired neighbour, and its rank index is greater than \(i\). Particularly, when \({X}_{i}\) is \({X}_{n}s,{X}_{k+}\) is fixed to \({X}_{n}s\), \(ps\) denotes population size, \(f\) represents a foraging feature, and \(rand\) characterizes randomly generated values in the interval [0,1]. \(iter\) and \(ite{r}_{\text{max}}\) signify the present and maximal iterations, correspondingly. \(np\) represents the neighbour pair counts, and \(n{p}_{\text{ max}}\) is the maximum amount of \(np.\) \({w}_{a}\) refers to the autotrophic type weighted feature. A vector of mapping \(\left({M}_{f}\right)\) to forage takes a dimension of \(\left(1\times dim\right)\), where all elements are 0 or 1. The \(di\) symbolizes the index dimensionality \(di\in \{\text{1,2},\dots , dim\}.\)

Formerly, in a heterotrophic manner, a protozoan might consume food from its environment in the dark. It is modelled as an \({X}_{near}\) representing a neighbouring nutrition‐rich location in Eqs. (13–16), and:

The dormant is the second behaviour. Dormancy is a survival mechanism employed by protozoa to assess complex ecological factors. The mathematical representation of dormant behaviour is illustrated in Eqs. (17–18)

whereas \({X}_{\text{min}}\) and \({X}_{\text{max}}\) symbolize the lower and upper bounds of the attached vectors. \(l{b}_{di}\) and \(u{b}_{di}\) characterize the lower and upper limits of the \(di th\) variable.

Reproduction is the final behaviour once the protozoans are of appropriate health and age. The next is the method’s mathematical representation, as shown in Eqs. (19–20).

whereas \({M}_{r}\) refers to a mapping vector within the reproduction procedure, whose dimensions are \(\left(1\times dim\right)\), and all components are \(0\) or 1.

The APO model is examined in dual phases. The population initialization is the initial phase, utilizing random and Latin hypercube sampling as the primary models. Conventional random sampling is applied in the presented model. Formerly, the fitness value of all possible solutions was measured after the primary population was generated. The population is looked for iteratively across three stages during this second phase. The initial stage in the iterative searching procedure resolves the problem of selecting appropriate solutions. The second stage involves searching for operators that mimic the individual behaviour of a normal population. The final stage is the upgrade mechanism. Algorithm 1 describes the APO method.

The APO model generates a fitness function (FF) to achieve enhanced classification performance. It states an optimistic number to epitomize the better competence of the candidate solution. The classifier rate of error minimization was measured as FF. Its mathematical computation is expressed in Eq. (21).

Experimental result and analysis

The experimental evaluation of the APOFTLM-EGR technique is examined by utilizing the custom dynamic isolated Indian SL dataset52,53. Table 1 presents 210 samples classified into five classes.

Figure 4 illustrates the classifier results of the APOFTLM-EGR methodology on the test dataset. Figures 4a–b shows the confusion matrix with perfect recognition and classification of all five classes on a 70%:30% TRASE/TESSE. Figure 4c displays the PR analysis, indicating superior performance across each class. At the same time, Fig. 4d depicts the ROC values, indicating capable results with a more comprehensive ROC analysis for dissimilar classes.

Table 2 and Fig. 5 present the overall gesture detection analysis of the APOFTLM-EGR technique on the 70%TRASE and 30%TESSE. The results indicate that the APOFTLM-EGR technique correctly identified five samples. On 70%TRASE, the APOFTLM-EGR technique presents an \(acc{u}_{y}\), \(pre{c}_{n}\), \(rec{a}_{l}\), \({F}_{score}\), and \({G}_{mean}\) of 99.46%, 98.72%, 98.52%, 98.58%, and 98.60%, correspondingly. Followed by, on 30%TESSE, the APOFTLM-EGR approach provides an \(acc{u}_{y}\), \(pre{c}_{n}\), \(rec{a}_{l}\), \({F}_{score}\), and \({G}_{mean}\) of 99.37%, 97.50%, 98.67%, 97.98%, and 98.03%, respectively.

Figure 6 illustrates the TRA \(acc{u}_{y}\) (TRAAY) and validation \(acc{u}_{y}\) (VLAAY) analysis of the APOFTLM-EGR technique. The \(acc{u}_{y}\) analysis is computed across the range of 0–25 epochs. The figure highlights that the TRAAY and VLAAY analysis exhibitions exhibit a rising trend, which identifies the capacity of the APOFTLM-EGR approach to deliver superior performance across multiple iterations. Simultaneously, the TRAAY and VLAAY leftovers converge across the epochs, identifying inferior overfitting and exhibiting the optimal results of the APOFTLM-EGR approach, ensuring dependable predictions on unseen samples.

Figure 7 shows the TRA loss (TRALO) and VLA loss (VLALO) curve of the APOFTLM-EGR methodology. The loss values are computed across the range of 0 to 25 epochs. The TRALO and VLALO analyses exemplify a reducing tendency, which indicates the APOFTLM-EGR approach’s capacity to balance a trade-off between data fitting and simplification. Besides ensuring the greater results of the APOFTLM-EGR technique, the constant reduction in loss values tunes the prediction results over time.

To demonstrate the superior performance of the APOFTLM-EGR methodology, a brief comparison analysis is presented in Table 3 and Fig. 818,19,20,21,22,23,54,55,56. The results illustrated that the AiFusion model displayed better classification results with an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 92.66%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 96.71%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 93.67%, and \({F}_{score}\) of 93.82. Furthermore, the BiLSTM, XLNet-BIGRU-Attention, YOLOv5s, IoT-FAR, DSMS-TF, MSAD, ResNeXt, DenseNet121, and ResNet50 models attained moderate values. In the meantime, the 3D-CNN, LSTM, KRLS, k-nearest neighbours (kNN), and ANN models have achieved somewhat closer classification results. Furthermore, the SLDC-RSAHDL approach has demonstrated reasonable performance with an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.23%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 95.74%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 96.18%, and \({F}_{score}\) of 94.18%. However, the APOFTLM-EGR approach demonstrates promising performance with \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.46%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 98.72%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 98.52%, and \({F}_{score}\) of 98.58%.

Table 4 and Fig. 9 illustrate the computational time (CT) analysis of the APOFTLM-EGR technique with existing methods. The comparison of computation time (CT) in seconds across various frameworks highlights the efficiency of the APOFTLM-EGR technique, which achieves the fastest CT of 4.04 s. Other models such as BiLSTM and XLNet-BIGRU-Attention require 10.88 and 9.11 s, respectively, while popular architectures like YOLOv5s and DenseNet121 take significantly longer at 15.00 and 18.58 s. Several other methods including IoT-FAR, DSMS-TF, MSAD, and SLDC-RSAHDL exhibit higher CTs ranging from 12.77 to 24.29 s. Conventional algorithms like K-Nearest Neighbors and ANN also show slower times of 23.09 and 11.87 s, correspondingly. Overall, the APOFTLM-EGR method demonstrates superior speed, making it highly appropriate for time-sensitive applications.

Table 5 and Fig. 10 demonstrates the error analysis of the APOFTLM-EGR approach with existing models. The APOFTLM-EGR approach achieves the lowest errors, with an \(acc{u}_{y}\) error at 0.54, \(pre{c}_{n}\) error at 1.28, \(rec{a}_{l}\) error at 1.48, and \({F}_{score}\) error at 1.42, indicating its superior prediction reliability. Other models such as BiLSTM and DenseNet121 exhibit higher \(acc{u}_{y}\) errors of 5.95 and 6.66 respectively, with corresponding \(pre{c}_{n}\), \(rec{a}_{l}\), and \({F}_{score}\) errors also notably larger. Models like IoT-FAR and ResNeXt illustrate relatively low \(acc{u}_{y}\) errors but higher \(pre{c}_{n}\) and \(rec{a}_{l}\) errors, reflecting some imbalance in performance. Conventional methods like k-Nearest Neighbors and ANN exhibit moderate errors in \(acc{u}_{y}\) but higher errors in \(pre{c}_{n}\) and \({F}_{score}\). Overall, the APOFTLM-EGR model’s consistently low error values across all metrics highlight its robustness and efficiency compared to other methods.

Table 6 and Fig. 11 demonstrate the ablation study of the APOFTLM-EGR methodology. The APOFTLM-EGR methodology achieves a superior \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.46%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 98.72%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 98.52%, and an \({F}_{score}\) of 98.58%. The SSAE model achieves an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.85%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 97.92%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.76%, and \({F}_{score}\) of 98.01%, indicating robust performance but slightly lower than the APOFTLM-EGR model. The APO model exhibits an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.08%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 97.14%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.22%, and an \({F}_{score}\) of 97.36%. ResNet-50 achieves an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 97.31%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 96.58%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 96.48%, and \({F}_{score}\) of 96.74%, while InceptionV3 and VGG16 show \(acc{u}_{y}\) values of 96.68% and 96.16%, respectively, with corresponding \(pre{c}_{n}\), \(rec{a}_{l}\), and \({F}_{score}\) values slightly lower than ResNet-50. These outputs highlight the superior performance of the APOFTLM-EGR model across all evaluation metrics.

Table 7 indicates the comparison of computational efficiency and memory usage of the APOFTLM-EGR method over existing approaches57. With only 9.56 GFLOPs and 567 MB of GPU memory usage, the APOFTLM-EGR model significantly outperforms other methods in terms of resource efficiency. In contrast, models like MMMFNet and MCBAM-GRU require 16.37 and 18.25 GFLOPs with 2667 MB and 1821 MB of GPU memory, correspondingly. More complex models such as LFCNN and NIMFT consume even higher computational and memory resources, reaching up to 28.11 GFLOPs and 1784 MB. This clearly emphasizes that the APOFTLM-EGR model presents a highly efficient and lightweight solution, making it appropriate for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Conclusion

In this study, a novel APOFTLM-EGR model is proposed. The APOFTLM-EGR model aims to enhance GR for visually impaired individuals. Initially, the image pre-processing stage applies WF to remove redundant or unwanted noise from the input image data. Furthermore, the fusion models, namely VGG16, InceptionV3, and ResNet-50, execute the feature extraction process. For the GR process, the SSAE technique is designed. Finally, the APO technique optimally adjusts the SSAE technique’s hyperparameter values, resulting in greater detection performance. The efficiency of the APOFTLM-EGR method is validated by comprehensive studies using the Indian SL dataset. The experimental validation of the APOFTLM-EGR method delivered a superior accuracy value of 99.46% compared to existing models.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are openly available at [https://github.com/DeepKothadiya/Custom/_ISLDataset/tree/main] (https:/github.com/DeepKothadiya/Custom/_ISLDataset/tree/main), reference number [52].

Code availability

The method is implemented in Python 3.6.5 and trained on an i5-8600 k CPU with 4 GB GPU, 16 GB RAM, using a 0.01 learning rate, ReLU activation, 50 epochs, 0.5 dropout, and batch size of 5. Code placed the generated results in the publicly available link https://github.com/zgenz1537-code/BrainStroke, with no access restrictions.

References

Mujahid, A. et al. Real-time hand gesture recognition based on deep learning YOLOv3 model. Appl. Sci. 11(9), 4164 (2021).

Deepaletchumi, N. and Mala, R. Leveraging variational autoencoder with hippopotamus optimizer-based dimensionality reduction model for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis data. J. Intell Syst. Internet Things, 16(1), 2025.

Mukhiddinov, M., Djuraev, O., Akhmedov, F., Mukhamadiyev, A. & Cho, J. Masked face emotion recognition based on facial landmarks and deep learning approaches for visually impaired people. Sensors 23(3), 1080 (2023).

Mohanty, A., Rambhatla, S.S. and Sahay, R.R. Deep gesture: Static hand gesture recognition using CNN. In Proceedings of International Conference on Computer Vision and Image Processing: CVIP 2016. 2, 449–461, (Springer 2017).

Al-Hammadi, M. et al. Deep learning-based approach for sign language gesture recognition with efficient hand gesture representation. IEEE Access 8, 192527–192542 (2020).

Nivash, S. et al. Implementation and analysis of AI-based gesticulation control for impaired people. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022(1), 4656939 (2022).

Mukhiddinov, M. & Cho, J. Smart glass system using deep learning for the blind and visually impaired. Electronics 10(22), 2756 (2021).

Kim, J. H., Hong, G. S., Kim, B. G. & Dogra, D. P. deepGesture: Deep learning-based gesture recognition scheme using motion sensors. Displays 55, 38–45 (2018).

Adithya, V. & Rajesh, R. A deep convolutional neural network approach for static hand gesture recognition. Proced. Comput. Sci. 171, 2353–2361 (2020).

Basheri, M. Automated gesture recognition using zebra optimization algorithm with deep learning model for visually challenged people. Fusion Pract. Appl., 16(1), (2024).

Panagiotou, C., Faliagka, E., Antonopoulos, C. P. & Voros, N. Multidisciplinary ML techniques on gesture recognition for people with disabilities in a smart home environment. AI. 6(1), 17 (2025).

Gaikwad, S. A. & Shete, V. User adaptive hand gesture recognition for ISL using multiscale and attention embedded residual densenet with adaptive gesture segmentation framework. SIViP 19(3), 210 (2025).

Miah, A. S. M., Hasan, M. A. M., Tomioka, Y. & Shin, J. Hand gesture recognition for multi-culture sign language using graph and general deep learning network. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 5, 144–155 (2024).

Zholshiyeva, L. et al. Human-machine interactions based on hand gesture recognition using deep learning methods. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 14(1), 2088–8708 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. A mixed reality-based aircraft cable harness installation assistance system with fully occluded gesture recognition. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 93, 102930 (2025).

Al Farid, F. et al. Single shot detector CNN and Deep dilated masks for vision-based hand gesture recognition from video sequences. IEEE Access 12, 28564–28574 (2024).

Ryumin, D., Ivanko, D. & Ryumina, E. Audio-visual speech and gesture recognition by sensors of mobile devices. Sensors 23(4), 2284 (2023).

Xi, J. et al. Three-dimensional dynamic gesture recognition method based on convolutional neural network. High-Confidence Comput. 5(1), 100280 (2025).

Kabir, M. H., Miah, A. S. M., Hadiuzzaman, M. & Shin, J. Combining state-of-the-art pre-trained deep learning models: A novel approach for bangla sign language recognition using max voting ensemble. Syst. Soft Comput. 7, 200230 (2025).

Guo, S., Wu, M., Zhang, C. & Zhong, L. Emotion recognition in panoramic audio and video virtual reality based on deep learning and feature fusion. Egypt. Inform. J. 30, 100697 (2025).

Zia, H., Fteiha, B., Abdulnasser, M., Saleh, T., Suliemn, F., Alagha, K., Yousaf, J. and Ghazal, M. Gesture-controlled omnidirectional autonomous vehicle: A web-based approach for gesture recognition. Array, 100408 (2025).

Chai, X. et al. IoT-FAR: A multi-sensor fusion approach for IoT-based firefighting activity recognition. Inform. Fusion 113, 102650 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. An action quality assessment method for the “pull-up” movement based on a dual-stream multi-stage transformer framework. Intell. Sports Health 1(2), 103–112 (2025).

Rajalakshmi, E. et al. Static and dynamic isolated Indian and Russian sign language recognition with spatial and temporal feature detection using hybrid neural network. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inform. Process. 22(1), 1–23 (2022).

Sarwat, H. et al. Post-stroke hand gesture recognition via one-shot transfer learning using prototypical networks. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 21(1), 100 (2024).

Marzouk, R., Aldehim, G., Al-Hagery, M. A., Hilal, A. M. & Alneil, A. A. Automated gesture recognition using artificial rabbits optimization with deep learning for assisting visually challenged people. FRACTALS (fractals) 33(03), 1–12 (2025).

Bhavana, G., Surendran, R. and Ramya, P. December. Virtual steering with gesture control using 3D hand modeling. In IET Conference Proceedings CP824. 2022(26), 148–151. (The Institution of Engineering and Technology, 2022).

John, J. & Deshpande, S. Intelligent hybrid hand gesture recognition system using deep recurrent neural network with chaos game optimization. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 37(1), 75–94 (2025).

Saranya, G., Tamilvizhi, T., Tharun, S.V. and Surendran, R. Speech Emotion Recognition with High Accuracy and Large Datasets using Convolutional Neural Networks. In 2023 8th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES). 859–864, (IEEE, 2023).

Prabha, C., Singh, R., Malik, M., Pradhan, M. R. & Acharya, B. Advanced gesture recognition in gaming: Implementing EfficientNetV2-B1 for" Rock, Paper, Scissors". Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 15(3), 23386–23392 (2025).

Balasubramani, J. and Surendran, R. October. Utilizing Hybrid-Deep Learning for Autism Spectrum Disorder Detection in Children via Facial Emotion Recognition. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS). 487–492. (IEEE, 2024).

Zhang, S., Zhou, H., Tchantchane, R. & Alici, G. Hand gesture recognition across various limb positions using a multimodal sensing system based on self-adaptive data-fusion and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). IEEE Sensors J. 24, 18633–18645 (2024).

Nguyen, T. H., Ngo, B. V. & Nguyen, T. N. Vision-based hand gesture recognition using a YOLOv8n model for the navigation of a smart wheelchair. Electronics 14(4), 734 (2025).

Sarma, D., Dutta, H. P. J., Yadav, K. S., Bhuyan, M. K. & Laskar, R. H. Attention-based hand semantic segmentation and gesture recognition using deep networks. Evol. Syst. 15(1), 185–201 (2024).

Kadhim, M. K., Der, C. S. & Phing, C. C. Enhanced dynamic hand gesture recognition for finger disabilities using deep learning and an optimized Otsu threshold method. Eng. Res. Express 7(1), 015228 (2025).

Jalal, A., Khan, D., Sadiq, T., Alotaibi, M., Alotaibi, S.R., Aljuaid, H. and Rahman, H. IoT-based multisensors fusion for activity recognition via key features and hybrid transfer learning. IEEE Access (2024).

Kwon, O. J., Kim, J., Lee, J. & Ullah, F. Evaluation of benchmark datasets and deep learning models with pre-trained weights for vision-based dynamic hand gesture recognition. Appl. Sci. 15(11), 2076–3417 (2025).

Yadav, K. S. et al. A selective region-based detection and tracking approach towards the recognition of dynamic bare hand gesture using deep neural network. Multimed. Syst. 28(3), 861–879 (2022).

Yadav, K. S., Kirupakaran, A. M., Laskar, R. H. & Bhuyan, M. K. Detection, tracking, and recognition of isolated multi-stroke gesticulated characters. Pattern Anal. Appl. 26(3), 987–1012 (2023).

Yaseen, Kwon, O. J., Kim, J., Lee, J. & Ullah, F. Evaluation of benchmark datasets and deep learning models with pre-trained weights for vision-based dynamic hand gesture recognition. Appl. Sci. 15(11), 6045 (2025).

Shin, J., Miah, A.S.M., Kabir, M.H., Rahim, M.A. and Al Shiam, A. A methodological and structural review of hand gesture recognition across diverse data modalities. IEEE Access (2024).

Marques, P., Váz, P., Silva, J., Martins, P. & Abbasi, M. Real-time gesture-based hand landmark detection for optimized mobile photo capture and synchronization. Electronics 14(4), 704 (2025).

Haroon, M., Altaf, S., Gulzar, K. and Aamir, M. Human pose analysis and gesture recognition: Methods and applications. Deep Learning for Multimedia Processing Applications, 160–192 (2024).

Zhou, Q. et al. Fusion of multimodal spatio-temporal features and 3D Deformable convolution based on sign language recognition in sensor networks. Sensors 25(14), 4378 (2025).

Pandey, L. and Arif, A.S. MELDER: The design and evaluation of a real-time silent speech recognizer for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–23, (2024).

Gao, M., Ye, D. and Zhang, J. CNN-SVM-based Human-Computer Interaction Model for Automotive Systems in Complex Driving Environments. Informatica, 49(25), (2025).

Wang, D., Wang, M., Zhang, Z., Liu, T., Meng, C. and Guo, S. Wearable electronic glove and multi-layer para-lstm-cnn based method for sign language recognition. IEEE Internet Things J. (2024).

Göreke, V. A novel method based on Wiener filter for denoising Poisson noise from medical X-Ray images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 79, 104031 (2023).

Saha, A., Musharraf, S.M., Dey, A., Roy, H. and Bhattacharjee, D. Potato Leaf Disease Detection using CNN-A Lightweight Approach (2025).

Zhou, J.Q., Liu, Q.M., Ma, C.X. and Li, D., 2024. Cost prediction of tunnel construction based on interpretative structural model and stacked sparse autoencoder. Eng. Lett. 32(10).

Noaman, M. N., Ayoub, A. B. & Mahmood, S. S. Nonlinear model predictive control of a magnetic levitation system using artificial protozoa optimizer. Int. J. Robot. Control Syst. 4(4), 1947–1966 (2024).

https://github.com/DeepKothadiya/Custom_ISLDataset/tree/main

Kothadiya, D. et al. Deepsign: Sign language detection and recognition using deep learning. Electronics 11(11), 1780 (2022).

Alsolai, H., Alsolai, L., Al-Wesabi, F.N., Othman, M., Rizwanullah, M. and Abdelmageed, A. A. Automated sign language detection and classification using reptile search algorithm with hybrid deep learning. Heliyon, 10(1), (2024).

Wang, Y., Wang, S., Zhou, M., Jiang, Q. & Tian, Z. TS-I3D based hand gesture recognition method with radar sensor. IEEE Access 7, 22902–22913 (2019).

Duan, S., Wu, L., Liu, A. & Chen, X. Alignment-enhanced interactive fusion model for complete and incomplete multimodal hand gesture recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 31, 4661–4671 (2023).

Chen, Z., Gouda, M. A., Ji, L. & Wang, H. A multimodal multistream multilevel fusion network for finger joint angle estimation with hybrid sEMG and FMG sensing. Alex. Eng. J. 110, 9–23 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman center For Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2024-229.

Funding

King Salman Center for Disability Research,KSRG-2024-229

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Hanan Abdullah Mengash , Basma S. Alqadi and Radwa Marzouk. Data curation and Formal analysis: Hanan Abdullah Mengash , Basma S. Alqadi and Radwa Marzouk. Investigation and Methodology: Hanan Abdullah Mengash , Basma S. Alqadi and Radwa Marzouk. Project administration and Resources: Supervision; Hanan Abdullah Mengash. Writing—original draft: Hanan Abdullah Mengash , Basma S. Alqadi and Radwa Marzouk. Validation and Visualization: Hanan Abdullah Mengash , Basma S. Alqadi and Radwa Marzouk. Writing—review and editing, Hanan Abdullah Mengash , Basma S. Alqadi and Radwa Marzouk. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mengash, H.A., Alqadi, B.S. & Marzouk, R. An intelligent fusion-based transfer learning model with artificial protozoa optimiser for enhancing gesture recognition to aid visually impaired people. Sci Rep 15, 41426 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25244-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25244-5