Abstract

Continuous monitoring of respiratory rate (RR) in dogs is critical for early detection of respiratory and cardiac conditions. However, current solutions are often invasive, or impractical for at-home use. This study aims to evaluate four smartphone-based nearable methods (two audio-based and two video-based) for non-invasive RR monitoring in sleeping dogs. 27 dogs were recorded during natural sleep using four different setups: (A) audio with earphone microphone, (B) audio with smartphone microphone, (C) video from a top-down perspective, and (D) video from a lateral view. Signals were processed to estimate RR. Manual breath counting served as the reference. All methods demonstrated good agreement with the reference. RMSE ranged from 1.1 to 2.2 bpm, MAE from 0.7 to 1.5 bpm. Video-based methods performed better, with method D achieving the lowest errors (RMSE = 1.1 bpm, MAE = 0.7 bpm, bias = 0.00 bpm) and tightest limits of agreement in the Bland-Altman analysis ([-2.17, + 2.17] bpm). Pearson’s R² was above 0.97 for all methods except B. Friedman tests revealed no significant differences among methods. Based on these results, smartphone-based nearable solutions are accurate for non-invasive respiratory monitoring in sleeping dogs. Video-based methods are more robust, while audio methods may be suitable for dogs with audible breathing patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Monitoring respiratory rate (RR) in dogs during sleep is crucial for assessing their overall health. Respiratory irregularities can serve as early indicators of various medical conditions, including pulmonary and cardiac diseases. Conditions such as pneumonia, heart failure, or respiratory infections can all manifest through changes in breathing patterns. Early detection of these irregularities is essential for timely medical intervention and improved outcomes for the animal.

Methods of monitoring canine respiration

Veterinary clinics primarily rely on vital sign monitors, which require sensors in direct contact with the animal. These devices often necessitate sedation to minimize movement-related errors. While sedation can lower behavioral arousal and facilitate stillness, it is undesirable for respiratory monitoring because commonly used sedatives in dogs reduce respiratory rate and modify the breathing pattern (e.g., lower RR with compensatory increases in tidal volume), yielding measurements that may not reflect natural resting respiration1,2. In addition, the need for supervised drug administration reduces feasibility for routine or at-home use3. Other widely used methods include auscultation with a stethoscope, thoracic impedance measurements, and spirometry, but these approaches also come with limitations. Manual counting, which involves visually monitoring the dog’s chest movements, remains the most used reference method but is subject to operator error, making it an unreliable and time-consuming method for accurate and precise measurements.

Recent research has explored various non-invasive technologies for RR analysis. Among these, wearable and nearable technologies have demonstrated promising results.

These include systems that measure airflow movement, changes in thoracic volume, pulmonary resistance, and respiratory sounds. For instance, the Dolittle device (Zentry inc., Seoul, South Korea)4, a transducer belt placed around the dog’s thorax, is declared to measure heart rate (HR) and RR, but no validation data have been published. Another example of commercial wearable device is the PetPace smart collar (PetPace, Burlington, MA, USA)5, which uses acoustic sensors to detect RR in static conditions and has been used in published research works6. Foster et al.7 used a 6-axis inertial measurement unit (IMU) in an instrumented collar and obtained an accuracy in RR estimation of 94.3% on average when compared to a wearable respiration belt designed for humans, which cannot be considered a reference for validation studies. In a past work from our research group, we validated the use of three 9-axis IMUs to track canine respiration during surgical procedures, and obtained a mean root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.68 breaths per minute (bpm)8.

Using acoustic sensors appears to be a promising solution not only in wearables but also in nearables. In fact, studies in human medicine have successfully utilized smartphone microphones to detect respiratory patterns via breath sounds, processed through filtering and statistical analysis. Nam et al.9 investigated the use of a smartphone microphone to estimate RR by recording breath sounds. Similarly, Doheny et al.10 used audio signal processing and statistical evaluations to analyze expiration duration and RR, showing high accuracy compared to traditional plethysmography methods. While these approaches have been validated on humans, their application in animal studies is still in early stages.

Also the field of video analysis has been explored in the context of nearables, with techniques such as background subtraction, frame subtraction, and optical flow tracking applied to measure respiratory movements in animals. An abstract by Lampe and Self11 proposes the measurement of canine respiratory rates from video recordings, yielding an error margin of ± 4 bpm when compared to manual counting.

Other nearable-based solutions include the use of ultra-wideband (UWB) radars for vital signs monitoring, which was proposed by Wang et al.12 on 3 dogs and 5 cats. While estimated error in RR measurements was within 3%, it must be noted that the reference system for RR measurements was the electrocardiographic (ECG) signal, even if it is known from the literature that ECG-based RR measurements are not highly reliable when not at complete rest.

Such methods have not only been researched on dogs, but also on other animals, mostly in the field of precision livestock farming. Weixing and Zhilei13 developed a method for RR detection in pigs, using a camera positioned above the animal’s dorsal side to track thoracic oscillations. More advanced computer vision methods have also been applied on group housed pigs for the simultaneous detection of RR in multiple subjects14. Mantovani et al.15 predicted RR in unrestrained dairy cows analyzing video frames of red, green, and blue (RGB) and infrared (IR) night vision images. Bonafini et al. also proposed RR monitoring in sheep using visible and near-infrared videos16. The application of these technologies in veterinary medicine remains underexplored but holds significant potential for non-invasive monitoring.

Limitations of existing methods

Despite the promise of non-invasive respiratory monitoring, several challenges must be addressed before these technologies can be widely adopted.

One significant limitation of audio-based methods is the difficulty in differentiating between inspiratory and expiratory sounds, which is crucial for accurately determining the respiratory rate. Environmental noise can also interfere with the recording, reducing measurement accuracy. The use of external microphones, as seen in some human studies, has shown potential in mitigating background noise and improving signal quality.

Video-based methods, while effective, face challenges related to camera stability and movement artifacts. Studies using fixed overhead cameras, such as those in pig respiration monitoring13, have shown high accuracy, but handheld smartphone recordings introduce additional variability due to hand tremors and shifting backgrounds. Implementing image stabilization and machine learning algorithms could enhance the robustness of video-based respiration tracking also when smartphones are used.

Other nearable methods, such as using UWB radars12, present the problem of high costs and the need to install complex instruments in the owner’s house, with both practical issues and privacy concerns.

Wearable devices offer high accuracy but come with limitations related to comfort and long-term usability. Many dogs may resist wearing a sensor-equipped belt or vest, limiting the practicality of continuous monitoring.

Aim of the work

The aim of this work is to develop a non-invasive, accessible respiratory monitoring system for dogs using smartphone-based audio and video analysis. By leveraging the vast availability of smartphones, the study seeks to provide a low-cost, real-time solution for pet owners, reducing reliance on stressful clinical visits while ensuring continuous health monitoring. Measuring RR at home also avoids the excitement associated with clinic visits, which often leads to overestimation, and reduces dependence on clinic-based assessments.

Specifically, this research evaluates the feasibility of smartphone-based audio and video analysis for detecting canine RRs and compare different methodological approaches to determine the most accurate and practical solution.

Materials and methods

This study developed and tested four distinct methods for assessing canine RR non-invasively. Two approaches focused on audio recordings (Methods A and B), whereas the other two leveraged video recordings (Methods C and D). The overarching goal was to capture dogs’ natural breathing while they slept and to process these data-either via sound amplitudes or thoracic movements—to yield a bpm estimate of RR.

All audio and video analyses were carried out in MATLAB (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA, versions 2022b and 2023b) under a consistent pipeline, comprising signal extraction, filtering, and automated peak detection. Each dog’s true RR was determined by manually counting inspirations, used as a reference method for comparison with the four automated methods.

Population and data collection

A heterogeneous sample of dogs, varying in size, breed, age, sex, and coat length, was recruited through voluntary owner participation. Owner-reported dog characteristics (breed, age, sex, body weight and size category—toy < 2.5 kg, small 2.5–10 kg, medium 11–25 kg, large 26–45 kg, giant > 45 kg—coat length, and known diagnoses) were collected. Dogs were considered healthy according to owner report; no veterinarian-performed clinical examination or medical record verification was undertaken for this study. Owner-reported details are summarized in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material. The only requirement was that each dog be able to sleep comfortably so that owners could record stable, disturbance-free audio or video footage.

This study was designed as a methods-comparison validation with repeated measurements per dog. We set the target sample size a priori by reference to analogous wearable validation studies in healthy humans17, which commonly enroll on the order of 25–35 volunteers and report stable agreement metrics across repeated segments. In view of this precedent and the use of multiple sleep segments per dog, we considered a cohort of 25 to 35 dogs sufficient to characterize method agreement (bias, error and limits of agreement) at this exploratory stage.

Because owners were asked to capture their dogs’ sleep in a home environment (Fig. 1a), no stress was imposed on the animals. Dogs were recorded only when sleeping naturally, with minimal ambient noise and without sedation.

Each dog’s owner was instructed to provide four recordings (approximately 90 s each) corresponding to the four methods, which consist in the following experimental setups:

-

Method A: Audio acquisition using a wired earphone microphone placed near the dog’s muzzle.

-

Method B: Audio acquisition using only the smartphone’s built-in microphone, also positioned near the dog’s muzzle.

-

Method C: Video acquisition from a top-down view, focusing on the dog’s thoracic and abdominal region.

-

Method D: Video acquisition from a side (lateral) view, again emphasizing the trunk area.

For Method A, owners used their own wired earphones. In all cases, owners used their own smartphones, therefore the hardware used differed from owner to owner. There was no constraint on using a single brand or model, nor was any specific hardware provided to owners, to reflect real-world use and maximize generalizability.

Owners were not instructed to standardize temperature, humidity, or room across sessions. To limit short-term variability, they were instructed to perform the audio (A and B) and video acquisitions (C and D) consecutively, possibly within the same sleep episode, and to avoid waking or moving the dog between methods, thereby maintaining largely stable ambient conditions over the few minutes needed to complete the sequence.

The resulting smartphone screen frames are illustrated in Fig. 1, showing how owners should place either the phone or the earphone microphone relative to the dog’s muzzle (for audio methods, Fig. 1b and c) or position the phone’s camera above or beside the dog (for video methods, Fig. 1d and e).

The experiment was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Perugia (approval number 25/2022) and performed in accordance with relevant regulations. Before enrolling a dog, the owner signed an informed consent form.

Audio and video signal processing

In all four pipelines, 90-second-long traces were all cut to 60 s to ensure that duration would be the same across samples, and to easily compute RR by manually counting the number of breaths in a minute.

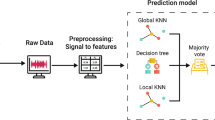

The key objective for methods A and B was to detect each inspiratory peak in the dog’s breathing cycle by analyzing amplitude fluctuations in the audio signal. Despite differences in microphone hardware (method A employed an external wired earphone microphone, while method B used the smartphone’s internal microphone), both methods employed the same MATLAB pre-processing and processing pipeline illustrated in Fig. 2a.

Video-based methods (C and D) employed a different pre-processing and processing pipeline with respect to audio-based methods, illustrated in Fig. 2b. In this case, the hardware used was the same, i.e., the smartphone’s camera, but the shot changed.

Audio-based methods (A and B)

Methods A and B (Fig. 2a) begin by importing the audio track (in MP4 or WAV format), then, using the Signal Analyzer App, the waveform is normalized by removing the mean and the amplitude scale is standardized to ensure consistency across different recordings.

Next, the signal is downsampled to 10 Hz, which reduces data size while preserving relevant frequency content. To highlight the dynamics of breathing, an envelope extraction step is applied using a RMSE-based upper envelope with a window length typically set to 1 s. This envelope helps emphasize the amplitude fluctuations associated with individual breaths. The signal is then smoothed to reduce noise and highlight the slow-varying trends of respiratory cycles.

A band-pass filter [0.075 Hz; 1 Hz] is then applied to isolate the breathing frequencies. The amplitude signal at the same 10 Hz sampling rate is then extracted. Finally, automated peak counting is performed on the filtered amplitude signal, identifying the characteristic breathing cycles, which are used to calculate the RR.

In Method A, we modified the signal pre-processing and processing functions parameters specifically for one dog, specifically adjusting the envelope value from 1 to 0.5 s and omitting the minimum height setting in the peak finder function. This adjustment was necessary because the dog exhibited a significantly elevated RR, averaging 50 bpm. The minimum height setting in the peak finder function was not used in other dogs as well. The parameters used for each acquisition are available in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material.

In Method B, the same issue was encountered with the previously mentioned dog with elevated RR, requiring the envelope window length to be reduced from 1 to 0.5 s, and adjustments to the peak height threshold. Additionally, the minimum distance between peaks was modified from 1.5 s to 0.5 s. For one dog, smoothing was applied only in the final step, while for another it was applied both in the intermediate and final steps. Furthermore, for four dogs, it was necessary to manually specify the smoothing window (either 0.5–1 s), as the automatic setting proved inadequate. The parameters used for each acquisition are available in Table S3 in the Supplementary Material.

Video-based methods (C and D)

Methods C and D (Fig. 2b) are based on the detection and analysis of the animal’s thoracic movements: each respiratory act is, in fact, characterized by an initial rise followed by a subsequent lowering of the thoracic wall. In this case as well, MATLAB was used, and some of the processing was performed in the Signal Analyzer app18.

The first step involves importing into MATLAB the video recorded by the owner and subsequently manually selecting a region of interest (ROI) on the dog’s body where maximum movement was expected, generally at the level of the thorax or abdomen8.

Around this point, a 20-pixel square area is created from which movements are tracked by saving the X and Y coordinates of 25 points within the area, using MATLAB’s Computer Vision Toolbox. The resulting coordinates are then combined into a single Z coordinate, which represents the net displacement, by applying the Pythagorean theorem. Vector Z is then imported into the Signal Analyzer application. First, the signal detrending is applied, followed by a high-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.05 Hz. Lastly, the signal is smoothed; initially, the parameters used are those provided by default, but during the analysis, it was observed that in most cases, it was necessary to adjust the value of the smooth window to 0.5 or 1 (and to 0.8 in one case).The output signal from the application is then imported into the second script, where peaks are identified to determine the number of respiratory acts. To perform this operation, the peakfinder function19 was used, configured to detect only maximum peaks, and interpolate the signal.

The “sel” parameter of the function, i.e., the amount above surrounding data for a peak to be identified, was generally set to 1, but during the analysis of various samples, it was often necessary to adjust it to values between 0.1 and 0.8 (except for two cases, where values of 1.5 and 0.1 were assigned). The parameters used for each acquisition are available in Table S4 (method C) and Table S5 (method D) in the Supplementary Material.

Statistical analysis

To quantify the accuracy of each automated approach, we calculated the RMSE, described in Eq. (1), and the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), described in Eq. (2).

\(\:{RR}_{auto,i}\) is the estimated RR for the i-th sample (using one of the four methods) and \(\:{RR}_{ref,i}\) is the corresponding manually counted RR.

Agreement between each automated method and the reference was evaluated using Pearson’s correlation and Bland-Altman analysis20, which displays the mean of the measurements on the x axis and the difference between them on the y axis.

To visualize the dispersion and potential outliers, boxplots were constructed for each method’s signed and absolute error values, where the signed error (SE) is computed as in Eq. (3), and the absolute error (AE) is the module of the SE.

Medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs), and whiskers were examined to identify whether any method exhibited consistently larger variability or bias.

Prior to comparing the methods, the distribution of error terms (both SE and AE) was assessed with the Lilliefors test to check for normality. Because this test returned a statistically significant result (p < 0.05) in all distributions but one, normality could not be assumed, and non-parametric tests were used for subsequent analyses.

To assess whether the four methods differed significantly in their performance, a Friedman test was applied to both the signed errors and the absolute errors across the entire dataset. The Friedman test is a non-parametric analogue of repeated-measures ANOVA. When the Friedman test indicated no significant difference among methods overall (p ≥ 0.05), no further group-level analysis was required for a global difference.

Nevertheless, for completeness, Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed between all method pairs. This approach compares the distribution of errors from any two methods while accounting for the multiple comparison problem.

Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT to improve the manuscript and the abstract. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Results

Population characteristics

In this study, we collected video and audio recordings from 33 dogs; however, 6 dogs were excluded due to missing recordings for some of the methods or inadequate footage, resulting in a final sample of 27 dogs. The exclusions were primarily due to the absence of specific recordings, as two videos required for audio-based analysis using method A and four for method B were missing.

Additionally, some recordings, despite being available, could not be processed by the software, including two videos for method A and two for method B. The reason why the software was not able to detect the respiratory patterns is likely the presence of background noise, which made it difficult to clearly distinguish respiratory sounds from ambient sounds.

Furthermore, some dogs may have very quiet breathing, producing only minimal noise, which further complicates detection. These challenges suggest that owners may have found it more difficult to record suitable audio of their dogs during sleep compared to capturing videos for thoracic movement analysis. For the remaining 27 dogs, all four required videos were successfully analyzed, resulting in a total dataset of 108 videos.

The analyzed cohort spanned juvenile to geriatric ages and all size categories, and included both mesocephalic and brachycephalic breeds (e.g., Pug, French Bulldog; see Table S1 in the Supplementary Material for details).

Sample respiratory traces

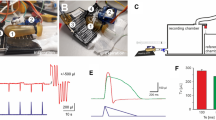

As examples of traces that can be obtained using the four different methods, both the original signals and the processed traces are reported for all methods.

Audio (methods A and B)

Figure 3 reports an example of audio recording with method A and with method B of the same dog. Figure 3a and c show the raw audio signal acquired using standard phone headphones or the smartphone’s built-in microphone, respectively. Figure 3b and d display the processed signal output from the Signal Analyzer app. By applying various functions such as smoothing, resampling, and a band-pass filter, the noise is significantly reduced, thus allowing to clearly identify the single breaths.

(a) Original audio signal obtained with method A (headphones); (b) filtered signal obtained with method A after processing; (c) original audio signal obtained with method B (smartphone’s built-in microphone); (d) filtered signal obtained with method B after processing. All data were acquired from the same dog.

Video (methods C and D)

Figure 4 reports an example of manual ROI selections in video recordings with method C (Fig. 4a) and with method D (Fig. 4b) of the same dog shown in Fig. 3. Figure 5a and c show the original trace of the net displacement Z(t) obtained from the video signal acquired from a top-down view or from a side view, respectively. The noise present in the trace is largely dependent on the selected ROI. Figure 5b and d display the processed signal output from the Signal Analyzer app. By applying functions such as detrending, a high-pass filter, and smoothing, the app made the signal easier to interpret and the peaks, corresponding to individual breaths, easier to identify.

(a) Original net displacement signal Z(t) obtained with method C (smartphone camera; top-down view); (b) filtered signal obtained with method C after processing; (c) original net displacement signal Z(t) obtained with method D (smartphone camera; lateral view); (d) filtered signal obtained with method D after processing. All data were acquired from the same dog.

Errors and agreement

The results in terms of errors with respect to manual counting in the case of the final population of 27 dogs are reported in Table 1.

According to both statistical measures, method D demonstrated the highest level of accuracy, while method B showed the greatest tendency toward error. Video-based methods in general display higher accuracy8.

The analysis of the audio-based methods (A and B) highlights a higher accuracy for method A, which uses an external microphone, i.e., embedded in standard headphones.

In addition to the above results, this can be also assessed in the boxplots in Fig. 6, where Fig. 6a reports the results in terms of signed errors and Fig. 6b in terms of absolute errors.

The boxplots representing the signed errors (Fig. 6a) indicate that the median for each method is close to zero, suggesting the absence of systematic bias in the over or underestimation of RR. Regarding the absolute errors (Fig. 6b), the medians are comparable (1 bpm), but method C exhibits a narrower IQR, fewer outliers, and shorter whiskers compared to the audio-based methods. This indicates lower error variability and greater robustness, confirming the hypothesis previously supported by the RMSE and MAE analysis.

Subsequently, scatterplots with regression lines and Bland-Altman plots are presented in Fig. 7, obtained for each of the four nearable methods analyzed.

(a) Scatterplot with regression line for method A; (b) scatterplot with regression line for method B; (c) scatterplot with regression line for method C; (d) scatterplot with regression line for method D; (b) Bland-Altman plot for method A; (d) Bland-Altman plot for method B; (f) Bland-Altman plot for method C; (h) Bland-Altman plot for method D.

As can be seen in the scatterplot, methods C and D (Fig. 7c,d) have the highest values of R2, equal to 0.99, method A performs slightly worse (R2 = 0.97), and performance decreases substantially in the case of method B (R2 = 0.90).

The Bland-Altman plots confirm the results obtained in terms of error metrics and R2. Method A (Fig. 7e) displays a positive bias (0.37 bpm), suggesting a systematic overestimation relative to manual counting. In contrast, methods B (Fig. 7f) and C (Fig. 7g) have a negative bias (-0.30 bpm and − 0.22 bpm, respectively), and D (Fig. 7h) has a bias of 0.00 bpm. Method D exhibits the smallest bias and narrow limits of agreement (LoAs) ([-2.17, + 2.17] bpm); also method C shows similar LoAs ([-2.55, + 2.11] bpm), indicating a higher overall agreement of video-based analysis with the reference method. Results obtained in the video-based methods show narrower limits of agreement than those obtained by Lampe and Self11, who reported limits of agreement within ± 4 bpm. Also LoAs obtained with method A are narrower than ± 4 bpm ([-2.76, 3.50] bpm), while method B has the worst performance ([-4.67, + 4.08] bpm).

Statistical analysis

The Lilliefors test, applied to the distributions of errors (both signed and absolute) obtained in all four methods, returned a p-value < 0.05 for all methods apart from the case of the signed error obtained with method B (p = 0.10). This result justified the use of non-parametric statistical tests for the subsequent comparative analyses.

The Friedman test did not reveal statistically significant differences between the methods, either for signed error (p = 0.36) or for absolute error (p = 0.41). Post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction, conducted on both metrics, confirmed the absence of statistically significant differences: all p-values were greater than 0.05, and the confidence intervals of the mean differences included zero.

Although no statistically significant differences were found between the methods, video-based methods stand out for their high accuracy (Table 1), lower variability in errors (Fig. 6), and greater agreement with the reference method (Fig. 7). These findings suggest that, within the analyzed context, it is preferable to use video-based methods instead of audio-based ones, but there is no significantly better method with respect to the others.

Discussion

Respiratory monitoring technologies have seen significant advancements in human medicine, particularly in the field of the Internet of medical Things21. The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the development of contactless respiratory monitoring solutions, including smartphone-based breath sound analysis and AI-driven video tracking. While these technologies have been applied in the field of veterinary medicine, and in some cases specifically on dogs, the most used method to assess RR outside clinical settings remains manual breath counting, which is however not suitable for prolonged monitoring. Furthermore, manual counting is subject to observer variability, uncertainty with shallow or silent breaths, and sensitivity to precise temporal alignment and ruling of sighs or pauses. Non-invasive clinical references such as impedance pneumography (IP)22 or respiratory inductance plethysmography (RIP) offer breath-by-breath timing without masks or cannulas and would allow longer, continuous ground truth during sleep; capnography or pneumotachography/spirometry provide accurate timing and flow but typically require nasal cannulas or masks that may alter natural respiration and sleep behavior at home23. We anticipate that, under stable home conditions, our audio–video estimates would show comparable agreement to IP and RIP, which track thoracoabdominal motion, while capnography or pneumotachography would best quantify breath timing and tidal dynamics in controlled settings. Finally, commercial collars (accelerometer or microphone-based) could serve as pragmatic comparators for user-facing applications, though published validation against clinical standards in dogs remains limited.

Achievements

This work presents two nearable-based solutions to monitor RR in sleeping dogs, i.e., using audio recordings (either by using standard headphones or the smartphone’s built-in microphone) or using video recordings (with different shots on the smartphone). All tested methods demonstrated low RMSE and MAE values and good agreement with manual counting, and results suggest a better performance in case of video-based methods. Method A, which uses an external microphone, proves to be less sensitive to the presence of outliers compared to the internal microphone of the smartphone used in method B. This difference likely reflects the higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) obtained by positioning the microphone a few centimeters from the nares and orienting it toward the airflow. In contrast, the internal smartphone microphone, located farther from the source and subject to automatic gain control and noise-suppression algorithms tuned for human speech, could attenuate quiet airflow sounds and compress peaks.

Since there is no statistically significant difference between the methods, based on the results presented in this work an owner could choose a preferred setup based on their dog’s sleeping position, length of coat hair (e.g., dogs with long hair might be more difficult to be monitored without a clear view of the belly), and even peculiar characteristics (e.g., pugs are known to be noisy while breathing, so audio methods are very effective).

In particular, the limits of agreement obtained by the two methods based on video analysis are within ± 2.55 bpm, way lower than what has been published before in the field of video analysis of breathing in dogs11. The best MAE, obtained in the case of method D, is in line with what Bonafini et al.16 obtained in sheep (0.79 bpm) using videos in the visible range, which in turn is one the best results reported in the cited works. The specific advantage of the video method is that the audio of recording can be turned off, and the smartphone left in a place of choice of the owner, thus this does pose any threat for the owner’s privacy.

This work demonstrates the feasibility of employing smartphones, which most pet owners already have, to perform home monitoring of RR in sleeping dogs, potentially for some hours or even the whole night, without the need for manual intervention of the owner. This allows to have a more complete overview of the dog’s status and to provide the veterinarian with detailed information to make informed decisions on possible therapy or need for visits. Additionally, the technology presented in this paper could also be used as a screening and prevention tool that requires minimum effort for owners and could help the early identification of clinical problems.

This is particularly relevant especially since dogs are non-verbal, therefore they cannot express their discomfort. Additionally, in presence of respiratory diseases, the animal either minimizes its activity or compensates by altering its breathing pattern. For this reason, many animals effectively hide their illness until critically low levels of lung reserve remain.

Limitations

While the methodologies we propose in this work present many advantages, one of which is undoubtedly the low cost and simplicity of the setup, there are limitations to this study that must be considered. Although our cohort size (n = 27) is consistent with sample sizes commonly used in human validation studies17 and also heterogeneous in size and breed, it remains modest; consequently, the precision and power of our estimates are limited and subgroup analyses (e.g., by breed or body size) were not feasible17.

In method A, standard wired headphones were used, however not all pet owners are expected to have wired headphones. Using wireless headphones however poses a threat in case the dog wakes up and accidentally ingests them. The smartphone audio recording appears to be more feasible in practical context.

Additionally, in this specific experiment the ROI of video recordings (methods C and D) was chosen manually by the researchers processing the data, but this is a key limitation as it would not be feasible to apply a method based on manual ROI selection on large scale and for long recordings. Some processing parameters required manual adjustment on a per-dog basis (Tables S2–S5 in the Supplementary Material), which impacts reproducibility and user-friendliness. This reflects heterogeneity in home environments, device microphones, and visual factors (coat, posture). Although the decision pathway was prespecified, manual tuning remains a limitation that needs to be addressed to apply the methodology on a large scale.

Home environmental conditions (room, temperature and humidity, background noise) were not controlled; although back-to-back acquisitions during the same sleep episode likely minimized short-term drift, residual variability may remain, affecting the results.

Finally, dog owners in this case were directly in touch with researchers when preparing the setup, and therefore able to ask questions and clarification. The presence of technical support has been demonstrated to improve the user experience of individuals using digital health solutions24, but having technical support might be too costly and burdensome for a hospital. Such problems might lead to lower-quality recordings or even interruption of participation and cooperation of owners when applied in real-life scenarios.

Future developments

Future developments of this work include the automatization of the ROI selection procedure in the video recordings, possibly using artificial intelligence-based methods to choose the ROI appropriately at the beginning of a recording and even adapting it if conditions change during the recording, which is particularly relevant in the case of long recordings. To improve the performance of automated ROI selection, a possible feature of the mobile app is to allow owners to manually select the sleeping position at the beginning of the recording: this a priori knowledge would provide an additional input variable to the automated, artificial-intelligence based ROI selection algorithm, and make it easier to detect potential posture changes during the recording if ROI characteristics vary too abruptly.

Another key feature to be implemented is the full automatization of the signal processing pipeline: this can be achieved by selecting filter and envelope windows adaptively, for instance from the current inter-breath interval and signal-quality indices and use SNR-adaptive peak detection thresholds. This function and in general the automatization of the process can be achieved with a dedicated mobile application. A minimal viable product (MVP) would acquire synchronized audio and video during sleep, run on-device processing, compute RR with built-in quality flags and error messages, and upload anonymized summaries to a secure database. Key features would include guided acquisitions (sleep posture detection and distance hints), automatic ROI tracking as previously mentioned, fusion of audio and video estimates with outlier rejection, a portal to share data with veterinarians, and privacy-by-design options (local processing by default, owner consent management, pseudonymization, encrypted storage/transmission). Because the core functions are recording and structured storage, the software complexity would be modest. The main effort would lie in hardening the signal-processing modules for diverse home environments and devices. Under typical conditions, an MVP could be engineered within a few months by a small team, whereas a production-grade, validated release would require a longer timeframe (≈ 6–12 months) to cover usability testing, quality assurance, and regulatory/privacy compliance.

Additionally, the methods should be tested on a larger cohort of dogs, stratified by age, breed, size, preferred sleeping position, and length of coat hair. This would allow us to provide accurate recommendations to owners on how to better detect their dog’s RR based on the characteristics of the animal. External validation in clinical cohorts – instead of using only owner-reported characteristics - is needed to quantify performance across phenotypes and to report stratified metrics by cephalic type and disease status. Future work should also log ambient conditions (such as temperature, humidity, and background noise level) to quantify their impact on signal quality and agreement.

The audio-based and video-based methods can be further studied not only in terms of RR, which was the focus of this paper, but also in terms of respiratory waveform and other breathing parameters. In this case manual counting would not be sufficient, therefore a trial using a vital signs monitor should be designed for this case.

Furthermore, the methodologies and technologies developed in this study have potential applications beyond canine subjects, extending to livestock monitoring for early detection of respiratory diseases and overall animal well-being, thereby contributing to improved health management in various veterinary contexts.

Additionally, the potential of non-contact respiratory monitoring extends to human healthcare, where nearable technologies such as smartphone microphones and cameras are being explored as unobtrusive tools for tracking breathing and other physiological parameters, in contexts such as in neonatal wards, sleep monitoring, infectious disease isolation, and home-based chronic care. Recent studies have shown that video-based and radiofrequency-based nearables can reliably estimate RR in hospitalized patients, offering a practical alternative to traditional contact-based systems25.

Conclusions

This paper presents nearable-based methods, specifically audio-based and video-based, to assess RR in sleeping dogs. The results of the validation against manual counting showed that there is good agreement between measurements in all cases. Data have been collected using smartphones, thus proving the immediate applicability of the proposed methodology for home monitoring of one’s pets. Future developments of the work include full automation of the methodology to scale the solution, larger cohorts to provide more robust statistics, and stratified validation in brachycephalic and cardiopulmonary disease cohorts to establish generalizability.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiography

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- IMU:

-

Inertial measurement unit

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- RR:

-

Respiratory rate

- UWB:

-

Ultra-wide band

References

Sinclair, M. D. A review of the physiological effects of α2-agonists related to the clinical use of medetomidine in small animal practice. Can. Vet. J. 44, 885 (2003).

Pleyers, T., Levionnois, O., Siegenthaler, J., Spadavecchia, C. & Raillard, M. Investigation of selected respiratory effects of (dex)medetomidine in healthy Beagles. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 47, 667–671 (2020).

Grubb, T. et al. 2020 AAHA anesthesia and monitoring guidelines for dogs and Cats*. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 56, 59–82 (2020).

Zentry Official. (2025). https://www.zentry.kr/

Monitor your Pets Health with PetPace. (2025). https://petpace.com/

Owoyele, B. V., Nishimura, R., Kleine, S. & Meijs, S. Initial exploration of the discriminatory ability of the PetPace collar to detect differences in activity and physiological variables between healthy and Osteoarthritic dogs.

Foster, M., Wang, J., Williams, E., Roberts, D. L. & Bozkurt, A. Inertial measurement based heart and respiration rate estimation of dogs during sleep for welfare monitoring. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series https://doi.org/10.1145/3446002.3446125 (2020).

Angelucci, A., Birettoni, F., Bufalari, A. & Aliverti, A. Validation of a wearable system for respiratory rate monitoring in dogs. IEEE Access. 12, 80308–80316 (2024).

Nam, Y., Reyes, B. A. & Chon, K. H. Estimation of respiratory rates using the Built-in microphone of a smartphone or headset. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 20, 1493–1501 (2016).

Doheny, E. P. et al. Estimation of respiratory rate and exhale duration using audio signals recorded by smartphone microphones. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 80, 104318 (2023).

Lampe, R. & Self, I. Remote respiratory rate monitoring of resting dogs. BSAVA Congress Proceedings 485–485 (2015). https://doi.org/10.22233/9781910443521.66.1

Wang, P. et al. Non-Contact vital signs monitoring of dog and Cat using a UWB radar. Animals (Basel). 10, 205 (2020).

Weixing, Z. & Zhilei, W. Detection of porcine respiration based on machine vision. 3rd International Symposium on Knowledge Acquisition and Modeling, KAM 2010 398–401 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/KAM.2010.5646284

Wang, M. et al. A computer vision-based approach for respiration rate monitoring of group housed pigs. Comput. Electron. Agric. 210, 107899 (2023).

Mantovani, R. R., Menezes, G. L. & Dórea, J. R. R. Predicting respiration rate in unrestrained dairy cows using image analysis and fast fourier transform. JDS Commun. 5, 310–316 (2024).

Bonafini, B. L. et al. Simultaneous, non-contact and motion-based monitoring of respiratory rate in sheep under experimental condition using visible and Near-Infrared videos. Animals (Basel). 14, 3398 (2024). .

Angelucci, A. et al. Validation of a body sensor network for cardiorespiratory monitoring during dynamic activities. Biocybern Biomed. Eng. 44, 794–803 (2024).

Signal Analyzer. https://it.mathworks.com/help/signal/ref/signalanalyzer-app.html

Yoder, N. peakfinder(x0, sel, thresh, extrema, includeEndpoints, interpolate) - File Exchange - MATLAB Central (2025). https://it.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/25500-peakfinder-x0-sel-thresh-extrema-includeendpoints-interpolate

Martin Bland, J., Altman, D. G., Statistical methods for & assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 327, 307–310 (1986).

Angelucci, A. & Aliverti, A. The medical internet of things: applications in respiratory medicine. Digital Respiratory Healthc. (ERS Monograph) Sheff. Eur. Respiratory Society 1–15 (2023).

Grenvik, A. et al. Impedance pneumography. Comparison between chest impedance changes and respiratory volumines in 11 healthy volunteers. Chest 62, 62 (1972).

Angelucci, A. & Aliverti, A. Telemonitoring systems for respiratory patients: technological aspects. Pulmonology 26, 221–232 (2020).

Angelucci, A. et al. A participatory process to design an app to improve adherence to anti-osteoporotic therapies: A development and usability study. Digit. Health. 9, 20552076231218856 (2023).

Diao, J. A., Marwaha, J. S. & Kvedar, J. C. Video-based physiologic monitoring: promising applications for the ICU and beyond. NPJ Digit. Med 5 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly funded by the National Plan for National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) Complementary Investments (PNC, established with the decree-law 6 May 2021, n. 59, converted by law n. 101 of 2021) in the call for the funding of the Research Initiatives for Technologies and Innovative Trajectories in the health and care sectors (Directorial Decree n. 931 of 06-06-2022)–AdvaNced Technologies for Hu-man-centrEd Medicine (ANTHEM) under Project PNC0000003. This work reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither the Ministry for University and Research nor European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A. Angelucci, F. Birettoni, A. Aliverti. Data curation: A. Badino, V. Bussolati, S. Caccia, C. Campanini. Formal analysis: A. Angelucci, A. Badino, V. Bussolati, S. Caccia, C. Campanini. Funding acquisition: A. Aliverti. Investigation: A. Angelucci, A. Badino, V. Bussolati, S. Caccia, C. Campanini. Methodology: A. Angelucci, F. Birettoni, A. Aliverti. Project administration: A. Aliverti. Resources: A. Aliverti. Software: A. Angelucci, A. Badino, V. Bussolati, S. Caccia, C. Campanini. Supervision: F. Birettoni, A. Aliverti. Validation: A. Angelucci. Visualization: A. Angelucci, A. Badino, V. Bussolati, S. Caccia, C. Campanini. Writing – original draft: A. Angelucci, A. Badino, V. Bussolati, S. Caccia, C. Campanini. Writing – review & editing: A. Angelucci, F. Birettoni, A. Aliverti.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Angelucci, A., Badino, A., Bussolati, V. et al. Audio and video nearables for monitoring respiratory rate in sleeping dogs. Sci Rep 15, 41374 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25305-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25305-9