Abstract

The location-specific characteristics of superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) have not been determined. This study analyzed the locational characteristics of superficial ESCC. Medical records of patients with superficial ESCC treated between December 2008 and November 2024 at Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital were retrospectively reviewed. ESCC locations and final pathological results confirmed by surgery or endoscopic resection were compared. A total of 150 patients with 163 superficial ESCCs were analyzed. Lesions were located in in the upper thoracic (n = 16, 9.8%), mid-thoracic (n = 104, 63.8%), and lower thoracic regions (n = 43, 26.4%). Although upper thoracic lesions had higher deep submucosal cancer (62.5% vs. 29.8%, p = 0.015) and poorly differentiated carcinoma (37.4% vs. 9.6%, p = 0.005) rates than mid-thoracic lesions, no lymph node metastasis or lympho-vascular invasion was detected. In contrast, the deep submucosal cancer rate was less for lower thoracic lesions than mid-thoracic lesions (14.0% vs. 29.8%, p = 0.049), but lymph node metastasis (7.0% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.782) and lympho-vascular invasion (7.0% vs. 4.8%, p = 0.600) rates tended to be higher. Superficial ESCCs in the upper thoracic region had more features requiring surgery but had less lymph node metastasis or lympho-vascular invasion, whereas lesions in the lower thoracic region showed the opposite trend. The results of our study may be helpful when deciding between surgery and endoscopic resection for some patients with superficial ESCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) occurs frequently in older individuals, and its prevalence increases with life expectancy1,2. ESCC is the most common histological type of esophageal cancer, and it is overwhelmingly prevalent in East Asia including South Korea2,3. Endoscopic screening programs for gastric cancer are available for the general population in Korea and Japan; and thus, more superficial ESCC cases are being discovered early4,5. Superficial ESCC confined to the mucosa without evidence of lymph node metastasis can be resected endoscopically. However, additional surgery or radiotherapy is required if submucosal invasion or lympho-vascular invasion is observed after endoscopic resection6,7,8. Additionally, poorly differentiated types of cancer present high risks of lymph node metastasis, and thus, additional treatment is recommended8,9,10.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI) are recognized tools for predicting the depth of superficial esophageal cancer11,12,13. However, these techniques can only be performed in tertiary medical institutions and their accuracy is greatly dependent on endoscopist skills. Lymph node metastasis of esophageal cancer can be predicted using EUS, computed tomography (CT), and positron emission tomography/CT14,15. However, since superficial esophageal cancer has a low lymph node metastasis rate, no study has attempted to predict lymph node metastasis using those tools in only superficial esophageal cancer. To date, no report has been issued on the location-specific characteristics of superficial esophageal cancer. This lack of evidence creates clinical dilemmas, as physicians must decide between endoscopic resection and surgical treatment without fully understanding whether the risks of submucosal invasion, lympho-vascular invasion, or lymph node metastasis differ by tumor location. Clarifying these location-specific patterns is important because it may guide endoscopic screening strategies and help optimize treatment selection. Therefore, we considered that if locations are associated with risk factors for lymph node metastasis, more attention could be paid to these locations during screening endoscopy, and the information obtained might help determine treatment directions. In this study, we aimed to identify the characteristics related to the location of superficial ESCC.

Methods

Patients

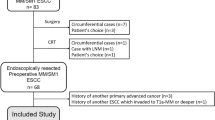

The medical records of patients with esophageal cancer treated between December 2008 and November 2024 at Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital (South Korea) were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with histologically confirmed T1 ESCC who underwent surgery or endoscopic resection were included in the study. Those who did not follow up after treatment, those with ambiguous pathologic results, and those who underwent chemoradiotherapy before surgery were excluded. All patients included in the study underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, chest/abdominal CT, and EUS before treatment.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital review board (Institutional Review Board no. 55-2024-145), which waived the requirement for informed consent because medical records were anonymized before analysis. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations by the Ethics Committee of Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital review board.

Endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound before treatment

The location, size, and macroscopic type of all cancers were recorded at the time of endoscopy. Tumor location and macroscopic type were classified according to the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer16. Tumor location as determined by endoscopy was based on distance from an incisor: 15 to 20 cm was defined as the cervical esophagus, 20–25 cm was defined as the upper thoracic esophagus, 25 to 30 cm was defined as the mid-thoracic esophagus, and 30 to 40 cm was defined as the lower thoracic esophagus17. All lesions were identified by narrow-band imaging and Lugol’s iodine chromoendoscopy. A near circumferential lesion was defined as cancer involving more than three-quarters of the esophageal lumen. All examinations were performed under conscious sedation via intravenous midazolam (2.5–8 mg). Invasion depth was measured using an EUS catheter probe (20 MHz; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with the water-filled method. Lymph nodes were evaluated using a radial EUS scope (GF-UE 160-AL5 Radial Array Ultrasound Gastrovideoscope; Olympus).

Surgery

Patients treated surgically underwent Ivor Lewis esophagectomy with intrathoracic anastomosis and two or three-field lymph node dissection if anatomical abnormalities were absent. Patients with anatomical abnormalities, such as those that had undergone gastrectomy, underwent jejunal or colonic interposition. All patients underwent circular stapled anastomosis. Anastomotic leakage was assessed by using esophagography and endoscopy 1 week after surgery. Resection completeness (R0) and lymph node metastasis were evaluated pathologically.

Endoscopic resection

T1 esophageal cancer cases without evidence of lymph node metastasis during the preoperative examination and those with cancer localized to mucosa by EUS were treated by endoscopic resection. Of the patients with suspected submucosal invasion, some at high surgical risk underwent endoscopic resection. Almost all patients underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), and most procedures were conducted under conscious sedation without general anesthesia. ESD was performed by confirming the lesion border by narrow-band imaging or Lugol’s iodine chromoendoscopy and marking at a distance of ≥ 2 mm from the border. If no complications occurred, patients started eating the day after the procedure and were discharged the following day.

Histopathological evaluation

Surgically resected primary tumors and lymph nodes were sliced at 4-mm intervals, and endoscopically resected primary tumors were sliced at 2-mm intervals. Two pathologists with more than 5 years of experience independently assessed specimens of primary tumors and lymph nodes to determine tumor invasion depth, macroscopic type, differentiation, lympho-vascular invasion status, and nodal metastasis. In cases of discordance, the specimens were re-evaluated under a multi-headed microscope until consensus was reached. The specimens were pathologically reviewed according to the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer (11th edition)16. Infiltration of esophageal cancers was subclassified into the following six categories: M1, intraepithelial carcinoma; M2, tumor infiltrating the lamina propria; M3, tumor infiltrating the muscularis mucosa; SM1, tumor invasion to the shallow strata (medial third) of the submucosal layer or ≤ 200 µm from the muscularis mucosae in endoscopically resected specimens; SM2, tumor invasion into the middle strata (middle third) of the submucosal layer; and SM3, massive tumor invasion into the deep strata (outer third) of the submucosal layer.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for individual lesions because some patients had multiple lesions. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. The mid-thoracic location was used as the reference when comparing groups. The analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was accepted for P values < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients and superficial ESCC

During the study period, 167 patients were histologically diagnosed with T1 ESCC confirmed by surgery or endoscopic resection. One hundred and fifty of these patients constituted the study cohort. The other 17 were excluded: 10 who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, four with ambiguous pathologic results and three who were not followed up. A total of 163 superficial ESCCs were analyzed, including multiple lesions (nine lesions in six patients), metachronous lesions (two lesions in two patients), synchronous lesion (one lesion in one patient), and recurrent lesion (one lesion in one patient). Mean patient age was 67 years (range 41–85 years), and 141 (86.5%) patients were male. Most lesions were located in the mid-thoracic region (n = 104, 63.8%). The most common macroscopic lesion appearance was the flat type (n = 105, 64.4%). There were 14 (8.6%) whole or near circumferential lesions.

Histopathological characteristics of superficial ESCC

Eighty-nine (54.6%) lesions were removed surgically, and 74 (45.4%) were removed endoscopically. After endoscopic resection, 10 patients (4 surgery and 6 radiotherapy) received additional treatment based on final pathological results, and none of them had evidence of lymph node metastasis. No patient developed lymph node metastasis during follow-up after endoscopic resection. Median tumor length along the longitudinal axis was 1.8 cm (range, 0.1–10.0 cm). Cancer invasion depths were 76 (46.6%) for M1/M2, 40 (24.5%) for M3/SM1, and 47 (28.8%) for SM2/SM3. Cancer was well differentiated in 73 (44.8%), moderately differentiated in 71 (43.6%), and poorly differentiated in 19 (11.6%). Lympho-vascular invasion was present in 8 (4.9%) patients and lymph node metastasis in 9 (5.5%) patients. No lympho-vascular invasion or lymph node metastasis was observed in patients with multiple lesions. The baseline characteristics of patients and lesions are summarized in Table 1.

Comparison of mucosal and submucosal cancers

There were 105 (64.4%) mucosal and 58 (35.6%) submucosal cancers. Submucosal cancer was significantly more prevalent in the upper thoracic region (17.2% vs. 5.7%, p = 0.024), whereas mucosal cancer was significantly more prevalent in the lower thoracic region (34.3% vs. 12.1%, p = 0.003). Macroscopic findings showed that all types, except IIb, were more prevalent among submucosal cancers. The accuracy of EUS for predicting invasion depth was 76.2% in mucosal cancers and 67.2% in submucosal cancers (p = 0.220). For submucosal cancers, differentiation was poorer (27.6% vs. 2.9%, p = 0.024), tumors were larger (median length 2.7 cm vs. 1.5 cm, p < 0.001), and lympho-vascular invasion (10.3% vs. 1.9%, p = 0.033) and lymph node metastasis (12.1% vs. 1.9%, p = 0.017) were more frequent than for mucosal cancers. Table 2 summarizes comparisons between mucosal and submucosal cancer.

Comparison of characteristics according to location of superficial ESCC

Superficial ESCCs were located in the upper thoracic (n = 16, 9.8%), mid-thoracic (n = 104, 63.8%), and lower thoracic regions (n = 43, 26.4%). Table 3 compares the characteristics of superficial ESCC according to location with those of mid-thoracic lesions. Age, gender, and tumor length did not show any differences according to location. Upper thoracic lesions were more likely to have macroscopic morphology predicting deeper invasion depth than mid-thoracic lesions (e.g., type I; 25.0% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.018). Accordingly, surgery was performed significantly more frequently on upper thoracic lesions (87.5% vs. 43.3%, p = 0.005), and the final histopathological results also showed these lesions had higher prevalences of deep SM cancer (62.5% vs. 29.8%, p = 0.015) and the poorly differentiated type (37.4% vs. 9.6%, p = 0.005). Despite this, there was no lympho-vascular invasion or lymph node metastasis in the upper thoracic lesions. On the other hand, lower thoracic lesions were more likely to have macroscopic morphology predicting shallow invasion depth than mid-thoracic lesions (type IIb; 83.7% vs. 59.6%, p = 0.007). The final pathologic invasion depth of the lower thoracic lesions was also shallow than that of mid-thoracic lesions (M1/M2; 62.8% vs. 43.3%, p = 0.033 and SM2/SM3; 14.0% vs. 29.8%, p = 0.049). Nonetheless, lympho-vascular invasion (7.0% vs. 4.8%, p = 0.600) and lymph node metastasis (7.0% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.782) rates tended to be higher for lower thoracic lesions than mid-thoracic lesions. Figure 1 shows the characteristics of superficial ESCCs by location. A direct comparison between upper thoracic and lower thoracic lesions is provided in the Supplementary Table.

Representative cases

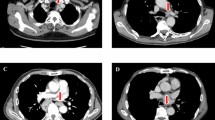

The first case is a 79-year-old male patient with an elevated superficial ESCC, and findings of pulling on the surrounding mucosa in the upper thoracic esophagus (Fig. 2A). Esophagectomy with lymph node dissection was performed (Fig. 2B), and histopathological results showed deep submucosal invasion (Fig. 2C) with poor differentiation (Fig. 2D). Final histological results showed no lymph node metastasis.

A 79-year-old male patient with superficial esophageal cancer located in the upper thoracic esophagus. (A) A raised lesion measuring 1.5 cm and appearing to pull at surrounding mucosa was observed in the upper esophagus. (B) Gross finding after esophagectomy. (C) Histopathological findings showed that cancer occupied almost all of the submucosa (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 20). (D) Section showing a poorly differentiated type (hematoxylin and eosin, × 200).

The second case is a 57-year-old male patient with a flat superficial ESCC, and erased margins as observed by Lugol’s iodine chromoendoscopy in the lower thoracic esophagus (Fig. 3A). Esophagectomy with lymph node dissection was performed (Fig. 3B), and the final pathological results showed it was well-differentiated cancer confined to the lamina propria (Fig. 3C). As compared to the previous case (Fig. 2C), abundant lymphatics are observed in the submucosa (Fig. 3C). In this case, para-esophageal lymph node metastasis was present despite it being an M2 cancer (Fig. 3D).

A 57-year-old male patient with superficial esophageal cancer located in the lower thoracic esophagus. (A) A flat lesion measuring 1 cm with well-defined borders was observed in the lower thoracic esophagus after applying Lugol’s iodine. (B) Gross finding after esophagectomy. (C) Histopathological findings revealed a well-differentiated cancer confined to the lamina propria (hematoxylin and eosin, × 20). Rich lymphatics were observed in the submucosa. (D) Metastasis was observed in a para-esophageal lymph node (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 40).

Discussion

In our study, superficial ESCCs located in the upper thoracic had characteristics that required surgery rather than endoscopic resection, such as deep submucosal invasive cancer or poorly differentiated carcinoma, and surgery was indeed more frequently performed. However, upper thoracic lesions did not show lympho-vascular invasion or lymph node metastasis. On the other hand, superficial ESCCs located in the lower thoracic showed characteristics that favored endoscopic resection, like type IIb, and M1/M2 cancer was significantly more prevalent in the histopathological results. However, lympho-vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis of lower thoracic lesions tended to be higher than those of mid-thoracic lesions. Considering these results of our study, we may cautiously attempt endoscopic resection or chemoradiotherapy first for superficial ESCCs located in the upper thoracic region. Conversely, our results caution that the possibility of lymph node metastasis should not be ruled out for superficial ESCCs located in the lower thoracic region, even after curative endoscopic resection.

The only known characteristic related to the location of esophageal cancer is that squamous cell carcinoma often develops in the upper and middle thoracic esophagus, and adenocarcinoma often originates from the esophagogastric junction and develops in the lower thoracic esophagus3,18. Lesions in our study were also most commonly located in the mid-thoracic region (63.8%). However, there are no known location-related characteristics for superficial esophageal cancer. One of the detailed results of a meta-analysis predicting the risk factors for lymph node metastasis in superficial ESCC showed that there was no difference in lymph node metastasis between upper-middle and lower lesions10.

In our study, superficial ESCC in the upper thoracic region had a deeper invasion depth than lesions in other locations. One possible reason is that lesions in the upper thoracic esophagus may have been missed during endoscopy. A large study found that early esophageal cancers of the upper esophagus are commonly missed and recommended that care be taken during endoscopy19. We could find no evidence that might explain why superficial ESCC in the upper thoracic esophagus had low rates of lympho-vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis despite a relatively greater invasion depth. One possible explanation is that the density of submucosal lymphatic vessels is relatively sparse in the upper thoracic esophagus. Kuge et al. (2003), citing Nakazawa et al. (1995), reported that submucosal lymphatic vessels are more numerous and thicker in the thoracic esophagus compared with the cervical esophagus20. Although this does not provide a direct comparison between upper and lower thoracic regions, it suggests regional variation in lymphatic distribution along the esophagus and may partly explain the lower risk of lympho-vascular invasion and nodal spread in upper thoracic superficial ESCC despite deeper invasion. Although we could not review the histopathology of all patients in the study, this trend was evident in the two cases presented. Histopathologic images of the case with an upper thoracic esophageal location showed that lymphatics were rare in the submucosal layer (Fig. 2C), whereas lymphatics were more abundant in the case with a lower thoracic esophageal lesion (Fig. 3C). However, to verify this hypothesis, confirmation based on multiple histopathological results is required.

Esophageal cancer located in the upper thoracic region has several unfavorable aspects compared to lesions in other locations. Since these regions are encountered immediately after inserting an endoscope, early-stage esophageal cancer may be missed during screening endoscopy19. When upper thoracic esophageal cancers reach an advanced stage, dysphagia may appear earlier and be more prominent than for mid or lower cancers. In one study, obstruction by ESCC was most common in the upper thoracic location21. When performing esophagectomy, it may be difficult to secure a proximal margin for upper thoracic esophageal cancer22. On the other hand, difficulties associated with endoscopic resection for esophageal cancer are known to be independent of location23,24. Based on these considerations, our results suggest that superficial ESCC in the upper thoracic region may be cautiously considered for endoscopic resection or chemoradiotherapy rather than surgery.

This study had some limitations. First, it is a single-center retrospective study conducted on a relatively small number of patients, and lesions located in the upper thoracic esophagus were rare. Therefore, the statistical reliability of the findings is limited, and some clinically meaningful differences may not have been detected because of the small sample size. Second, cervical esophageal cancer cases and some patients who underwent chemoradiotherapy were excluded because they could not be resected, and thus, could not be accurately pathologically staged. Third, the fewer lymphatics in the submucosal layer of the upper thoracic esophagus is only a hypothesis confirmed in some cases, and not all pathological specimens were reviewed.

In conclusion, our results indicate that superficial ESCC located in the upper thoracic esophagus showed lower rates of lympho-vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis despite deeper invasion, whereas lesions in the lower thoracic esophagus tended to show the opposite pattern. These findings suggest that tumor location may provide useful information for risk stratification, although treatment decisions should be individualized and further studies are needed to clarify the clinical implications.

Data availability

The data analyzed or generated during the study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ESCC:

-

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasound

- ME-NBI:

-

Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ESD:

-

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

References

Eisner, D. C. Esophageal cancer: Treatment advances and need for screening. JAAPA 37, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAA.0001007328.84376.da (2024).

Rustgi, A. K. & El-Serag, H. B. Esophageal carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 2499–2509. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1314530 (2014).

Liu, C. Q. et al. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in 2020 and projections to 2030 and 2040. Thorac. Cancer 14, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.14745 (2023).

Ishihara, R. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of superficial esophageal squamous cell cancer: Present status and future perspectives. Curr. Oncol. 29, 534–543. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020048 (2022).

Shin, C. M. Treatment of superficial esophageal cancer: An update. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 78, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2021.155 (2021).

Ajani, J. A. et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 2.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 21, 393–422. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.0019 (2023).

Kitagawa, Y. et al. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2022 edited by the Japan esophageal society: Part 1. Esophagus 20, 343–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10388-023-00993-2 (2023).

Obermannova, R. et al. Oesophageal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 33, 992–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.003 (2022).

Pimentel-Nunes, P. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2022. Endoscopy 54, 591–622. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1811-7025 (2022).

Xu, W., Liu, X. B., Li, S. B., Yang, Z. H. & Tong, Q. Prediction of lymph node metastasis in superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis. Esophagus https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doaa032 (2020).

Ishihara, R. et al. Endoscopic imaging modalities for diagnosing invasion depth of superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 17, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-017-0574-0 (2017).

Su, F., Zhu, M., Feng, R. & Li, Y. ME-NBI combined with endoscopic ultrasonography for diagnosing and staging the invasion depth of early esophageal cancer: A diagnostic meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 20, 343. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-022-02809-6 (2022).

Thosani, N. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS in differentiating mucosal versus submucosal invasion of superficial esophageal cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 75, 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.016 (2012).

Jeong, D. Y. et al. Surgically resected T1- and T2-stage esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: T and N staging performance of EUS and PET/CT. Cancer Med. 7, 3561–3570. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1617 (2018).

Sgourakis, G. et al. Detection of lymph node metastases in esophageal cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 11, 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1586/era.10.150 (2011).

Japan Esophageal, S. Japanese classification of esophageal cancer, 11th Edition: Part I. Esophagus 14, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10388-016-0551-7 (2017).

Rice, T. W. et al. Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction-Major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 304–317. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21399 (2017).

Sanchez-Danes, A. & Blanpain, C. Deciphering the cells of origin of squamous cell carcinomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-018-0024-5 (2018).

Chadwick, G. et al. A population-based, retrospective, cohort study of esophageal cancer missed at endoscopy. Endoscopy 46, 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1365646 (2014).

Kuge, K. et al. Submucosal territory of the direct lymphatic drainage system to the thoracic duct in the human esophagus. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 125, 1343–1349. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00036-9 (2003).

Ryu, D. G., Yu, F., Liu, H., Lee, S. S. & Lee, S. L. Clinical outcomes and prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma presenting with obstruction. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 56, 35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-024-01159-8 (2024).

Qureshi, Y. A., Sarker, S. J., Walker, R. C. & Hughes, S. F. Proximal resection margin in ivor-lewis oesophagectomy for cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 24, 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5510-y (2017).

Nagami, Y. et al. Predictive factors for difficult endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal neoplasia including failure of en bloc resection or perforation. Surg. Endosc. 35, 3361–3369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07777-0 (2021).

Wen, J., Lu, Z. S., Liu, C. H., Bian, X. Q. & Huang, J. Predictive factors of endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure time for early esophageal cancer. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 134, 1373–1375. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000001355 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT; no. RS-2023-00242011). This study was supported by Research Institute for Convergence of Biomedical Science and Technology, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital (30-2025-017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DG. R.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft; CW. C.: conceptualization, supervision, funding, writing—reviewing and editing; SY. K.: data curation, investigation; SJ. K.: investigation; SB. P.: resources; JO. J.: resources; WJ. K.: data curation, investigation; BS. S.: data curation; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital review board (Institutional Review Board no. 55-2024-145), which waived the requirement for informed consent because medical records were anonymized before analysis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ryu, D.G., Choi, C.W., Kim, S.Y. et al. Location characteristics of superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 41397 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25324-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25324-6