Abstract

Rock masses in cold regions deteriorate due to frost heave caused by fissure water, posing risks to engineering projects. This study investigates the long-term mechanical behavior of fully saturated fissured red sandstone under freeze–thaw conditions. Creep acoustic emission (AE) experiments were conducted to explore how freeze–thaw cycles and fissure dip angles influence rock creep and AE characteristics. Four freeze-thaw cycle levels (0, 30, 60, and 90) and three double-fissure orientations (15°–15°, 15°–75°, and 75°–75°) were examined in this study. Results show that: (1) Increasing freeze–thaw cycles lead to greater instantaneous and creep strains, higher AE signal amplitudes, exponential growth in AE energy rates, and faster b-value fluctuations. (2) With larger fissure dip angles, the instantaneous and creep strains significantly increase, while the amplitude density, intensity, and AE energy rates decrease. b-value fluctuations also slow down. (3) Abrupt b-value changes can predict freeze–thaw-induced rock failure. For intact samples subjected to 90 freeze–thaw cycles, intact non-freeze–thaw samples, and fissured non-freeze–thaw samples, b-value mutations occurred 12.96 s, 35.28 s, and 48.24 s earlier, respectively. These findings highlight b-value changes as an early indicator of freeze–thaw damage and provide theoretical insights into the creep failure of fissured rock masses under such conditions, aiding in the design and safety of cold-region engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Industrial Revolution marked a significant leap in productivity, which, in turn, led to a rapid increase in the consumption of global energy and mineral resources. In response, many countries have endeavored to develop mineral resources located in cold regions1,2,3,4, necessitating the establishment of an increased number of geotechnical engineering projects in these areas5,6,7. Rock masses, as natural geological bodies, inevitably contain numerous micro-pores and micro-defects due to geological structures8. With the seasonal or diurnal temperature changes in cold regions, the water retained within rock masses undergoes freeze-thaw cycles, resulting in the generation and dissipation of frost heave forces caused by the phase change of water to ice9, the freeze–thaw cycle mechanism stems from the approx. 9% volumetric expansion of water upon freezing, which generates high pore pressures within rock pores; upon thawing, melting ice creates additional void space and induces microcrack opening. Repeated freeze–thaw action thus accumulates damage by interacting with pre-existing joints, reducing elastic modulus and compressive strength, and accelerating microcrack nucleation and growth. These freeze-thaw cycles significantly diminish the physical and mechanical properties of the rock masse10. Consequently, the stability assessment of rock engineering in cold regions and the prevention of freeze-thaw disasters have become urgent issues that need to be addressed.

Among these time-dependent deformation processes, creep is one of the most fundamental mechanisms controlling the long-term stability of rock masses. In cold regions, repeated freeze–thaw cycles further accelerate creep deformation, making its investigation essential for understanding deterioration patterns and ensuring the safety of geotechnical structures.

Regarding the study of rock creep behavior, Ma and Daemen developed a mathematical model for steady-state creep under varying stress conditions based on uniaxial compression creep tests11. Sabitova et al. analyzed the staged characteristics observed in rock during creep and stress relaxation experiments, verifying the nonlinear deformation behavior of rocks12. In terms of modeling theory, Cirone et al.13 proposed a dual-mechanism model to serve as a theoretical basis for predicting the long-term deformation of rock salt. Gutiérrez14 applied rate process theory (RPT) in numerical simulations to reproduce various stages of the creep process, thereby supporting the development of more precise creep models. In terms of engineering applications, Tarifard et al.15 investigated how groundwater affects rock creep behavior in tunnels, analyzing the interaction between weak rock and groundwater and its impact on the long-term stability of tunnels. Delchiaro et al.16 used a multi-faceted approach to comprehensively analyze the dynamic feedback relationship between surface processes and tectonic activity on the time-dependent deformation of rock masses, providing a theoretical basis for predicting rockslides.

The mechanical properties of rocks are significantly influenced by freeze-thaw cycles. In microscopic analysis methods, Mousavi17 utilized scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to analyze the texture and microstructural changes of weathered samples and proposed a practical empirical model to predict and evaluate the performance of such rocks. Park et al.18 used X-ray computed tomography (CT) and SEM to obtain images of the internal microstructure of rocks and observed that freeze-thaw-induced volumetric expansion increased porosity. For the analysis of the corresponding parameters of microstructures under these conditions, Kolay19 explored the impact of freeze-thaw cycles on the engineering properties of sedimentary rocks, highlighting the critical role of internal properties like mineral composition and texture in determining engineering parameters. Aral et al.20 conducted experimental analyses on water absorption, P-wave velocity, uniaxial compressive strength, point load strength index, and Schmidt hardness values to measure and quantify the disintegration rate of rocks affected by freeze-thaw cycles. In the field of damage prediction and evaluation, Fakhri et al.21 developed a technique based on Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to estimate the failure load of rock samples under varying freeze-thaw (F-T) cycle conditions. Yahaghi et al.22 revealed the deterioration and failure mechanisms of sandstone under different freeze-thaw cycles through experiments and three-dimensional (3D) numerical modeling methods, providing valuable insights for assessing and designing durable geological structures in cold climates.

The inherent joints, pores, and other structures in fractured rock masses play a critical role in determining their mechanical properties23. Tobler et al.24 performed microscopic analysis of rock core samples using CT and electron microscopy, demonstrating a robust correlation between strength and the intact rock bridge area across fractures. Bauer et al.25 used a Schmidt hammer to measure rebound hardness in the field and identified variations in the mechanical properties of rock fractures across different fault zone sections. Major et al.26 conducted open-mode fracture mechanics tests to investigate the effects of CO2–water–rock interactions on fracture properties and the associated changes in reservoir and cap rock characteristics. Kluge et al.27 simulated the microscopic evolution of fault zones using a novel experimental apparatus and CT imaging, uncovering the relationship between fracture networks and permeability changes, and offered theoretical insights into the structural evolution of fault zones within geological reservoirs.

Acoustic emission plays a crucial role in predicting the failure and instability of coal28 and rock masses29. In damage monitoring applications, Rodríguez et al.30 used acoustic emission techniques to monitor sound signals emitted during material deformation or fracture. Khoshouei31 investigated the use of acoustic emission technology and the Kaiser effect to assess rock damage. Munoz-Ibanez32 assessed the fracture toughness of sandstone samples with varying diameters using synchronized multi-sensor acoustic emission monitoring. Petružálek et al.33 investigated the fracture behavior of jointed anisotropic mixed rocks using acoustic emission monitoring techniques, highlighting its utility in characterizing fracture properties. Regarding the prediction and assessment of acoustic emissions, Ebrahimian et al.34 analyzed the frequency of AE signals generated in rocks under stress through mathematical methods, offering a novel method for assessing crack propagation and damage in rocks. Manthei et al.35 utilized two significant AE clusters to analyze dimensions, spatial distributions, and the spatiotemporal relationships of AE events, demonstrating the existence of a Poisson process.

Research on creep and freeze–thaw (F–T) effects has laid a solid technical foundation for rock engineering in cold regions. Furthermore, studies on the creep behavior of fractured rock masses under F–T conditions have made certain progress. Tang et al.36 conducted creep tests under F–T cycles and established a nonlinear viscoelastic–plastic model to describe the effects of the accelerated stage and the number of cycles. Wei et al.37 proposed a fractional damage index based on triaxial creep tests and acoustic emission (AE) on saturated frozen sandstone, confirming that the steady-state creep rate significantly increases with F–T cycles. Regarding post-F–T mechanical responses, Cao et al.38 used uniaxial compression combined with AE/microscopic observation to reveal progressive damage and strength degradation paths. Kefayati et al.39 conducted F–T–direct shear–AE tests on non-persistent jointed rock samples and found that joint geometry and F–T cycles interact to weaken shear strength and alter failure modes. For fracture inclination, Wang et al. used DIC to quantify that 45° is the most unfavorable angle in terms of strength and modulus loss40; Bi et al.41 revealed an interaction between inclination angle and confining pressure, showing an “enhancement/reversal” effect. Furthermore, Li et al. performed F–T–fatigue coupled creep tests on fractured sandstone and proposed a damage criterion42; Yang et al. proposed an energy rate–b-value precursor and quantified long-term strength degradation through F–T staged creep tests and AE on double-fractured red sandstone43; Jielong et al. analyzed fracture angle and location to reveal the evolution characteristics of surrounding rock creep stages and instability44.

The previous section systematically described the importance and progress of research on rock creep behavior. Based on this, many scholars have studied the mechanical responses of rocks from the perspectives of freeze–thaw (F–T) cycling and fractures, and have also demonstrated the feasibility of using acoustic emission (AE) techniques in this field. However, studies on the creep behavior of rocks with multiple fractures under F–T conditions remain limited. There is insufficient AE–creep coupling evidence, and precursor identification remains unclear, making engineering applications difficult. Therefore, this study conducts creep tests on red sandstone specimens with double fractures under different F–T cycles (0, 30, 60, and 90 times). Specimens with various fracture inclinations were prepared, and staged constant-load creep tests were carried out. AE energy rate and b-values were recorded synchronously. By analyzing the correlations among F–T damage, fracture geometry, loading level, and precursor indicators, the creep behavior of fractured rocks with different inclination combinations under F–T conditions was clarified. This provides technical guidance for disaster prevention and control in cold-region engineering.

Experimental overview

Specimen preparation

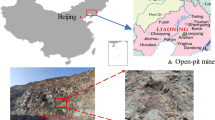

The red sandstone samples used in this experiment were sourced from a mining area in Inner Mongolia, China. Complying with the standards set by the International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM), the samples were processed into standard intact rock specimens with dimensions of D×H = 50 mm × 100 mm. Due to the inherent complexities of geological processes, natural rock formations harbor various pre-existing defects, such as intricate fractures. Consequently, for the laboratory experiment, double-fractured rock samples were chosen as the subjects of investigation. The preparation of these double-fractured rock samples was accomplished using a cutting line method.

In terms of fracture Angle setting, according to the expression of rock mass fault in relevant geological exploration and the fault distribution Angle of natural rock mass in engineering research practice, this paper divides the fracture Angle into two types: gentle type (0°~ 45°) and steep type (45°~ 90°). For this experiment, fracture angles of 15° (gentle) and 75° (steep) were selected and combined in pairs, they respectively correspond to two typical fracture structural forms that frequently occur in regional geological surveys. The resulting samples were designated as “gentle-gentle” (15°-15°), “gentle-steep” (15°-75°), and “steep-steep” (75°-75°). Additionally, an intact rock sample was included as the reference group. The geometric positions of the two pre-existing fractures were controlled by two parameters, α and β. Three fracture angle combinations were named accordingly. The specific illustration of the rock sample with α = 15° and β = 75° is shown in Fig. 1.

According to ISRM standard test procedures for rocks, visually distinct rock samples were initially excluded from the experiment. Subsequently, the remaining rock samples were placed in an oven at a constant temperature of 105 °C for 24 h. After cooling, their dry densities were measured. The selected rock samples were then vacuum-saturated at 0.1 MPa for 4 h, followed by a 4-hour static period under atmospheric pressure. From this point on, the quality of the saturated rock sample remains unchanged for a long time, and the rock sample is saturated. After retrieval, the masses of the saturated rock samples were measured to obtain the basic physical parameters, as presented in Table 1 Mean values of physical parameters of fractured rock samples. Based on the dry density and longitudinal wave velocity of the rock samples, specimens were chosen and divided into four groups, each consisting of three parallel samples, totaling 12 rock samples. These samples were utilized to conduct a study on the creep acoustic emission characteristics of fractured rocks under freeze-thaw conditions.

Test scheme and process

Following geological surveys, the temperature range in this cold region is approximately − 24 °C to 28 °C, with freeze-thaw cycles lasting around 1 to 3 months. To comprehensively study the creep characteristics of fractured rocks in a freeze-thaw environment and the differences in precursor damage, experiments were designed to include freeze-thaw cycles, uniaxial compression tests, and step-wise loading and unloading creep acoustic emission tests. These tests aim to simulate the climatic conditions and rock damage characteristics under creep actions experienced by natural rock masses in the cold region.

-

(1)

Freeze-thaw cycle tests: Except for the rock sample subjected to 0 freeze-thaw cycles, all other samples were placed in a test chamber for freeze-thaw cycle tests. Following the standards of the Engineering Rock Test Methods, freeze-thaw cycle numbers were set at 0, 30, 60, and 90. At the same time, in order to simulate the freeze-thaw cycle environment in the cold area, the cycle is set to 24 h (freezing 12 h, thawing 12 h), and the temperature range is ± 20 °C.

-

(2)

Uniaxial compression acoustic emission tests: The TW-1000 rock mechanics testing machine, controlled by a computer, was used to conduct uniaxial compression tests on samples subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. The test rate was set at 0.05 mm/min, and the mechanical data was collected at the frequency of 2 samples /s until the rock sample was broken (cracks began to develop in the test process, and the stress level of the rock sample dropped sharply in the stress softening stage, to be sure). The computer continuously recorded indicators such as load, displacement, and stress-strain in real-time.

Simultaneously, during the uniaxial compression tests, an acoustic emission monitoring system was employed to monitor and collect acoustic emission signals throughout the compression process of the specimens. Effective AE signals were collected. The AE signal sampling rate was set at 2 MHz, the threshold at 40 dB, and the preamplifier at 40dB. The equipment used in the specific experiment is shown in Fig. 2.

-

(3)

Step loading and unloading creep acoustic emission test.

In this experiment, a step-wise loading creep test method was employed. It involved conducting step-wise loading creep acoustic emission tests on intact rock samples, as well as rock samples with gentle-gentle, gentle-steep, and steep-steep fracture angles. The intact rock sample had a uniaxial compressive strength (\({\sigma _c}\)) of 19.57 MPa, and the loading procedure was as follows: the first loading stress was set at 30% of the uniaxial compressive strength, and subsequently, each level increased by 15% until failure. If the rock sample did not fail under the fifth level creep stress, the sixth level loading stress was set at 100, with only a 10% increment from the previous level. The stress loading levels at each stage are presented in Fig. 3. During creep loading, the loading speed was set at 0.01 MPa/s, and each load was maintained for 12 h before proceeding to the next stress level, repeating this process sequentially. Acoustic emission monitoring was conducted throughout the creep test. In this creep acoustic emission test of fractured rock under freeze-thaw action, rock samples with freeze-thaw cycles of 0, 30, 60, and 90 times were selected for experimentation. The complete raw AE–creep datasets are available in the supplementary file ae.creep.zip. Among them, 30 times are approximately equal to the number of freeze-thaw cycles in a typical cold and high-latitude region within a year. 60 times and 90 times respectively correspond to cumulative freeze-thaw cycles of two to three years to simulate the deterioration process of rocks under long-term service conditions, while 0 times are retained as the control group.

The influence and analysis of freeze-thaw action on creep AE characteristics of fractured rock

The influence and analysis of freeze-thaw cycle on rock creep characteristics

Creep is a common form of rock deformation, and the cold region’s freeze-thaw environmental conditions can have a certain impact on rock creep. Therefore, studying the creep characteristics of fractured rocks under freeze-thaw conditions is essential.

Figure 4 shows the variation of instantaneous strain in intact rock samples and rock samples with a gentle-gentle fracture angle at the first four stress levels under freeze-thaw cycles. Observations reveal that, at the same stress level, the instantaneous strain of the rock sample increases with the number of freeze-thaw cycles, regardless of the presence of fractures. This is because freeze-thaw cycles lead to the enlargement of internal microcracks in the rock samples, making the microcracks more easily compacted, resulting in an increase in instantaneous strain. Additionally, as the number of freeze-thaw cycles increases, the growth rate of instantaneous strain in the rock sample gradually decreases and eventually stabilizes. Furthermore, under the same freeze-thaw cycle number, the instantaneous strain of the rock sample increases with the increase in stress level. With the increase in freeze-thaw cycles, the influence of stress level on the strain of the rock sample becomes more evident.

Figure 5 illustrates the variation of creep strain in intact rock samples and rock samples with a gentle-gentle fracture angle at different stress levels as a function of the number of freeze-thaw cycles. It is essential to note that, due to the occurrence of a sudden increase in axial strain in the gentle-gentle rock sample with 0 freeze-thaw cycles during the fourth loading stage, this phenomenon is not reflected in the graph. Regardless of the presence of fractures, both intact rock samples and fractured rock samples exhibit noticeable creep strain at the first loading stage, which increases with the number of freeze-thaw cycles. This indicates that freeze-thaw cycles have a significant strengthening effect on the creep strain of rock samples. Meanwhile, the growth rate of creep strain in intact rock samples gradually slows down with an increasing number of freeze-thaw cycles. Additionally, for fractured rock samples with a gentle-gentle angle, the creep strain also increases with different numbers of freeze-thaw cycles, but the growth rate gradually decreases.

Based on the changing rate of the growth amplitude within a certain period, the rock creep stages can be classified into accelerating creep, steady-state creep, and decelerating creep stages.

The influence and analysis of freeze-thaw cycle on AE characteristics of rock

In the process of rock failure, the amplitude of AE reflects the internal stress state and the intensity of energy release within the rock. When rocks experience stress and undergo fracturing, energy is released, generating acoustic waves. The amplitude of these waves is related to the magnitude of internal stress and the intensity of energy release within the rock. Therefore, analyzing the amplitude of AE can provide insights into the internal stress state and the intensity of energy release within the rock.

The b-value is a parameter describing the exponential growth rate of AE events over time, offering information about the dynamic characteristics of internal rock fractures. Meanwhile, the energy rate represents the ratio of energy released during AE events to time, reflecting the activity level of internal fractures in the rock.

In this study, the b-value is calculated using the least squares method for AE events. To standardize the b-values, a normalization process is applied. The normalization method is expressed in equation, nsuring that the normalized AE values are consistent and not affected by fluctuations.

In the formula: \({b_i}\)is the normalized acoustic emission b value, \(b_{\alpha }\)is the normalized acoustic emission b value, \(b_{{\max }}\)is the maximum value of the normalized acoustic emission b value.

AE amplitude A (dB) is converted to magnitude m by:

To ensure complete detection, only events with A ≥ 40 dB are retained. b-values are then computed in overlapping windows of 100 events (or 60 s), whichever comes first, using the maximum-likelihood estimator:

where \(\bar {m}\) and \({m_{\hbox{min} }}\) are the mean and minimum magnitudes in each window. For each window we report the 95% Utsu confidence interval and the coefficient of determination\({R^2}\); windows with \({R^2}<0.9\) are discarded.

Because the law of 2 ~ 4 loading data is similar to that of the first stage, it is not representative. Therefore, only the variation law of acoustic emission amplitude with time under the first and fifth loading conditions is selected. As shown in Fig. 6 The variation of acoustic emission amplitude under the first stage stress loading and Fig. 7, when the unfrozen rock sample is loaded at the fifth level of stress (Fig. 6 The variation of acoustic emission amplitude under the first stage stress loading), the maximum amplitudes of the rock sample are 73 dB and 48 dB during the deceleration creep and constant creep, respectively. Under the subsequent loading stress, the amplitude of the deceleration creep stage is higher than that of the constant creep stage, and the amplitude density of the deceleration creep stage is higher. At the same time, the amplitude of the constant speed creep stage decreases obviously with time, and the number is more and more rare.

It is not difficult to see that in the deceleration creep stage, the density and size of the amplitude of the rock sample are significantly larger than those in the constant creep stage. In the constant creep stage, the number of amplitude changes with time gradually decreases. In the accelerated creep stage, the amplitude increases rapidly and the density reaches the maximum value. When the last level of stress is loaded, the number and strength of the amplitude reach the maximum, and the amplitude change is generally ' U ' -shaped. In addition, with the increase of the number of freeze-thaw cycles, the rock sample produces more micropores, and the amplitude generated by the stress at all levels is significantly increased and densified. However, when the stress is loaded to a certain stress level, the effect of freeze-thaw action on the amplitude gradually tends to dissipate.

Analyzing the variation patterns of individual rock samples, it is observed that the AE energy rate during the deceleration creep stage is greater than during the constant creep stage, indicating more active acoustic emission activity. For some rock samples, during the constant creep stage, the AE energy rate approaches zero, and a sudden increase in energy rate occurs when the rock sample enters the acceleration creep stage. Taking Fig. 8a as an example, under the initial stress loading, the maximum AE energy rate during the deceleration creep stage is 89 aJ/s, and during the constant creep stage, the maximum AE energy rate is 28 aJ/s. Comparable behavior is observed for the specimens after 30, 60, and 90 freeze–thaw cycles (Fig. 8b–d): the deceleration-stage energy rates consistently exceed those during the constant-rate stage, and a marked increase appears at the onset of acceleration creep. In subsequent stress loading stages, the AE energy rate consistently shows a pattern where the deceleration stage has a higher rate than the constant stage. When the rock sample enters the acceleration creep stage, the energy rate increases rapidly, reaching a maximum of 2.5 × 103 aJ/s.

Using Fig. 9 as an example, under the final stress loading stage, for all freezing-thawing cycles, the rock sample without freezing-thawing has the highest peak energy rate, reaching 2.5 × 103 aJ/s. With an increase in freezing-thawing cycles, the peak energy rates for 30, 60, and 90 freezing-thawing cycles are 1.9 × 103 aJ/s, 1.6 × 103 aJ/s, and 1.2 × 103 aJ/s, respectively, representing reductions of 24%, 36%, and 52%. This phenomenon suggests that the freezing-thawing cycles lead to a decrease in the peak AE energy rate during the rock sample’s creep failure, reflecting a reduction in the released energy. This is attributed to the weakening of the internal structure of the rock sample induced by the freezing-thawing cycles.

AE energy rate during the deceleration creep stage is greater than during the constant creep stage, indicating that more energy is released internally, and crack development is more pronounced during the deceleration creep stage. When entering the acceleration creep stage, the AE energy rate suddenly increases. Under the initial stress loading, the AE energy rate exponentially increases with the increase in freezing-thawing cycles. Freezing-thawing cycles reduce the peak AE energy rate during the rock sample’s failure stage, reflecting a decrease in the released energy. This phenomenon is attributed to the weakening of the internal structure induced by freezing-thawing cycles.

Figures 10 and 11 plot the evolution of the normalized acoustic-emission b-value (red) together with axial creep strain (black) under the first- and fifth-order stress levels for 0 and 90 freeze–thaw cycles. During the deceleration creep stage, b initially rises (indicating predominance of small-scale cracking) and then, as microcracks coalesce, begins to fall—this downward shift marks a transition to larger-scale damage. Under 90 freeze–thaw cycles, the downward trends are more pronounced and fluctuations denser, reflecting accelerated crack propagation due to ice-induced weakening. Upon entering the constant-rate creep stage, b stabilizes or slowly increases again, suggesting a temporary balance between crack opening and closure. Finally, just before acceleration creep, the b-value drops sharply and fluctuates wildly—an unambiguous precursor of imminent through-going fracture. Overall, increasing freeze–thaw damage shifts the entire b-value curve downward and amplifies its variability, while higher stress levels compress the fluctuation range, indicating that stress dominates crack growth once damage is severe.

In the fifth-stage stress loading (Fig. 11), the normalized b-value under both freeze–thaw conditions rises or remains stable during the deceleration and constant-rate creep stages, indicating predominance of small-scale microcracking. As the sample nears the acceleration creep onset, the b-value rapidly drops and fluctuates intensely, marking the transition to large-scale, through-going fracture—a clear precursor to failure. At the moment of rupture, the b-value reaches its minimum.

Under no freeze–thaw cycling, the b-value increases during the deceleration and constant-rate creep stages, reflecting predominantly small-scale microcracking. With freeze–thaw damage, the b-value instead declines during deceleration creep—signaling a shift to large-scale crack growth—and its fluctuations become denser. At higher stress levels, the difference between frozen and unfrozen samples narrows, as stress-driven damage dominates and compresses the fluctuation range.

The influence and analysis of different fracture dip angles on AE creep characteristics of rock

The influence and analysis of different fracture dip angles on rock creep characteristics

The formation of rock masses in cold regions is complex, often attributed to various factors leading to intricate structures, including joints and fractures. Considering the impact of internal rock structures on the overall stability, strength, and other mechanical characteristics, this study investigates the creep behavior of rocks with different fracture angles.

Figure 12 llustrates the variation in instantaneous strain of three types of double-fractured rock samples under different stress levels for freezing-thawing cycles of 0 and 90 times. When the freezing-thawing cycles are 0, the instantaneous strains of the gentle-gentle, gentle-steep, and steep-steep rock samples at the first stress level (30%) are 0.283 × 10− 2, 0.415 × 10− 2, and 0.595 × 10− 2, respectively. Compared to the gentle-gentle rock sample, the instantaneous strains of the gentle-steep and steep-steep rock samples increase by 46.64% and 110.24%, respectively. This indicates that with an increase in the double fracture angle, the instantaneous strain of the fractured rock samples rapidly increases. Similar trends are observed for fractured rock samples at other freezing-thawing cycle numbers. Moreover, shows that the instantaneous strains of the three fractured rock samples exhibit a linear increase with the increase in stress levels. In summary, at the same stress level, the instantaneous strain of fractured rock samples significantly increases with the increase in fracture angle, and the instantaneous strain demonstrates a linear growth with stress levels.

Figure 13 illustrates the variations in creep strain for three different fractured rock samples under freezing-thawing cycles of 0 and 90 times. From the graph, it is evident that, at the same stress level, the steep-steep rock sample exhibits the maximum creep strain, while the gentle-gentle rock sample shows the minimum creep strain. This indicates that the variation in creep strain is significantly influenced by the fracture angle, with larger angles leading to increased creep strain. For example, at the first stress level (30%) and freezing-thawing cycles of 0 times, the creep strain increases from 0.125 × 10− 3 to 0.158 × 10− 3, a growth of 24.60%, when transitioning from gentle-gentle to gentle-steep; further, transitioning from gentle-steep to steep-steep, the creep strain increases from 0.158 × 10− 3 to 0.232 × 10− 3, a growth of 46.84%. As the freezing-thawing cycles increase to 90 times, at the second stress level (45%), the creep strains for the three fractured rock types are 0.621 × 10− 2, 0.697 × 10− 2, and 0.742 × 10− 2, respectively, with creep strain increasing by 12.24% and 6.46% as the fracture angle increases. Simultaneously, within the same rock sample, it is observed that creep strain significantly increases with the rise in stress levels. In summary, at the same stress level, creep strain increases with the fracture angle and rapidly increases with the rise in stress levels.

This indicates that freezing-thawing cycles have a significant impact on both the instantaneous strain and creep strain of rocks. Un er the same stress level, the instantaneous strain and creep strain of rocks gradually increase with the increase in freezing-thawing cycles. However, the rate of increase decreases over time and tends to stabilize. Additionally, with an increase in the fracture angle, both instantaneous strain and creep strain of rocks exhibit a noticeable increase. The influence of freezing-thawing cycles and fracture angle on rock strain is related to the applied stress level. As the stress level increases, the impact of freezing-thawing cycles and fracture angle becomes more pronounced, resulting in larger rock strains.

Under the same stress level, an increase in the fracture angle leads to a significant growth in both instantaneous strain and creep strain of fractured rock samples. Instantaneous strain shows a linear increase with stress level, while creep strain rapidly increases with the rise in stress levels.

The influence and analysis of different fracture dip angles on rock AE characteristics

In the creep test, to precisely and academically ascertain the creep mechanical response characteristics of rocks under different fracture conditions, the method of acoustic emission monitoring was employed to monitor the creep process.

Figures 14 and 15 illustrate the amplitude variation graphs corresponding to three different fracture angles (gentle-gentle, gentle-steep, steep-steep) at various stress levels. In the first stress level loading (Fig. 14), the amplitude density and quantity of the gentle-gentle rock sample are significantly higher than the other two types, with maximum amplitudes of 90 dB, 82 dB, and 72 dB, respectively. It is observed that with an increase in fracture angle, the amplitude generated by the rock sample is significantly reduced at the first stress level loading. A similar pattern emerges in subsequent stress loading stages. Using Fig. 15 as an example, during the fifth stress loading level, the gentle-gentle and gentle-steep rock samples undergo failure, releasing a large number of amplitude signals. Although the steep-steep rock sample also exhibits a considerable number of amplitudes, it only experiences failure in the sixth stress loading level.

Figure 16 illustrates the AE energy rate variation curves for three distinct types of fractured rock samples (gentle-gentle, gentle-steep, steep-steep) under different stress levels with 0 freeze-thaw cycles. During the initial stress loading stage (Fig. 16), the AE peak energy rates for the three fracture types are 420 aJ/s, 178 aJ/s, and 90 aJ/s, respectively. The AE energy rate peaks nearly halve, and the density of AE events also significantly decreases. Similar patterns are observed for the other stress levels in the rock samples, indicating that as the fracture angle increases, the energy released during the rock creep process decreases. As AE energy rate is a crucial indicator of accelerated crack propagation in rocks, the reduction in both the frequency and peak values of AE events suggests that with an increase in the fracture angle, the crack propagation and penetration during the rock creep process tend towards stability and continuity.

Throughout the entire creep test, the peak AE energy rate of fractured rock samples consistently occurs during the accelerated creep failure stage, aligning with the timing observed in the intact rock samples. Moreover, it was observed that under the fifth stress level (Fig. 17), the AE energy rate generated by fractured rock samples is significantly higher than that of the intact rock samples. This indicates a notable influence of pre-existing fractures on the AE energy rate. The primary reason for this observation is the reduced stability of rock samples with pre-existing fractures, making them more prone to initiate cracks along the pre-existing fractures during the loading process. Consequently, the presence of pre-existing fractures results in a greater release of energy, leading to a higher AE energy rate in fractured rock samples compared to intact rock samples during the creep failure process.

Figures 18 and 19 respectively depict the variations of b values over time for the “Slow-slow” rock sample and the “slow-steep” rock sample under the condition of zero freeze-thaw cycles. A detailed analysis of the changes in b values under different stress levels for these two types of fractured rock samples is provided below:

During the deceleration creep stage, both the slow-slow and slow-steep samples exhibit a gradual increase in b values, reflecting the progressive nucleation of micro-cracks and stress redistribution within the rock. The slow-slow sample, however, displays a denser cluster of b values and larger fluctuations, indicating more frequent micro-damage events under low loading rates. In the constant-speed creep stage b values for both samples continue to rise as micro-cracks coalesce and localize; notably, the slow-slow sample’s steeper increase signifies accelerated damage accumulation under sustained stress.

At the final stress level, the slow-slow sample fails abruptly, so it does not traverse clear creep stages. Here, b values fluctuate intensely without a monotonic trend—these oscillations reveal rapid crack propagation and imminent collapse. A pronounced drop at 0.11 h marks the onset of macro-fracture formation, after which b-value variations resemble those seen in the earlier deceleration creep stage. By contrast, the slow-steep sample transitions into the acceleration creep stage: its b values decrease sharply just before this transition and then exhibit sustained oscillations, signaling progressive instability and the approach of ultimate failure.

As shown in the figures, increasing the fracture angle causes a marked reduction in both AE amplitude density and amplitude intensity. This decrease in amplitude indicates a smaller scale of microcrack activity and less extensive damage within the rock, thereby enhancing its overall stability. The trend in amplitude effectively captures the fracture process and highlights how damage differs across fracture geometries. At the same time, the AE energy rate peak and event density also decline significantly—since the AE energy rate quantifies crack-growth velocity, a lower peak suggests that, under creep loading, crack propagation shifts from rapid, unstable growth to a steadier, more continuous evolution. Together, these observations confirm that larger fracture angles suppress abrupt failure events and promote more stable crack development in the rock.

As the fracture angle of the rock sample increases, the b values become sparser and the fluctuation amplitude decreases during the deceleration creep stage. In the constant-speed creep stage, the overall upward trend of b values slows down, and the acceleration creep is less influenced by the increase in fracture angle. Rapid decreases in b values followed by intense up and down fluctuations are observed. This indicates that an increase in the predetermined double fracture angle can reduce the fluctuation and upward trend of b values, thereby improving the stability of the rock sample.

Discussion

Identification of rock creep failure precursor information

Creep acoustic emission experiments were conducted to analyze the amplitude, energy rate, and b-value characteristics of acoustic emissions during the rock creep process. The aim was to investigate the influence of fracture angle and freeze-thaw cycles on the acoustic emission characteristics of rock creep and the differences in precursory signals before failure.

The trend of amplitude changes effectively reflects the rock sample’s fracture process and illustrates the differences in damage between different freeze-thaw cycles and fracture angles. As the number of freeze-thaw cycles increases, the amplitude produced by the rock sample significantly increases and becomes denser. However, with the increase in stress loading levels, the impact of freeze-thaw cycles on amplitude gradually diminishes. An increase in fracture angle leads to a substantial decrease in amplitude density and intensity of the rock sample. The reduction in amplitude reflects a decrease in the scale of internal damage within the rock sample, indicating an increase in stability.

The AE energy rate serves as a crucial indicator of accelerated crack propagation in rock. The freeze-thaw cycles result in increased internal porosity and structural weakening of the rock sample. With an increase in freeze-thaw cycles, the AE energy rate under initial stress loading exhibits an exponential growth, while the peak AE energy rate during the failure stage decreases, indicating a reduction in the released energy of the rock sample. As the fracture angle increases, both the peak and density of AE energy rate noticeably decrease, suggesting that with an increase in the fracture angle, the crack propagation and penetration during the rock creep process tend to stabilize and become continuous, enhancing the stability of the rock. Furthermore, the distinct pattern of exponential growth in AE energy rate during early loading and its subsequent reduction at failure under increasing freeze–thaw cycles offers a powerful basis for real-time warning systems. In practice, one could define an energy‐rate threshold (for instance, 80% of the initial peak rate) and integrate it into an online AE monitoring platform operating at ≥ 1 Hz sampling. Once the measured energy‐rate exceeds this threshold, automated alerts could trigger load reduction or personnel evacuation, thereby providing second‐level early warning of rock deterioration. Such an approach would significantly enhance the safety management of tunnels and slopes in cold regions by converting laboratory observations into actionable, field‐deployable precursors.

Freeze-thaw cycles accelerate the fluctuation speed of the b-value, causing a transition from an ascending trend to a descending trend in the b-value during the deceleration creep stage. This transition signifies a shift in the dominant mode of microcrack development within the rock sample from small-scale to large-scale. However, this influence gradually diminishes with an increase in stress loading levels. A decrease in the angle between the double fractures reduces the stability of the rock sample, intensifying the b-value fluctuations during the deceleration creep stage but maintaining the predominance of small-scale microcrack development within the rock sample.

The recording and analysis of these AE events allow for the identification of distinctive acoustic features generated by rock specimens during different loading stages. This, in turn, facilitates inferences about the creep and failure processes of the rocks. Such experimental methods offer a non-destructive means for researchers to gain profound insights into the deformation and failure mechanisms of rocks under external forces. Consequently, this approach provides essential tools for precursor monitoring and risk assessment in engineering practices.

Precursor difference analysis of rock creep failure

In the process of rock creep, the increase in axial strain and the sudden drop in b-values can both serve as crucial indicators foretelling the unstable failure of the rock. Statistical analysis of the points of sudden b-value drops during the final creep loading of intact rock samples under freeze-thaw conditions (0 cycles and 90 cycles) and intact rock samples under freeze-thaw conditions (0 cycles) with a gentle-steep fracture angle (Slow-step) is conducted. This comparison aims to reveal differences in precursor information related to failure between freeze-thaw cycles and fracture angle specimens. Specific data are presented in Table 2 Precursor information of rock failure.

Based on the data in Table 2, when the rock sample is under the final stage of stress loading during accelerated creep, the points of sudden b-value drops consistently precede the axial strain failure points. This indicates that b-values can predict the unstable failure of the rock sample. For the intact rock sample without freeze-thaw cycles, the axial strain failure occurs at 1.3029 h, while the b-value experiences a sudden drop at 1.2931 h, predicting the failure approximately 35.28 s in advance. In the case of the rock sample subjected to 90 freeze-thaw cycles, the axial strain failure occurs at 4.8291 h, and the b-value shows a sudden drop at 4.8255 h, predicting the failure around 12.96 s in advance. For the unfrozen gentle-steep fractured rock sample, the axial strain failure occurs at 0.3051 h, while the b-value experiences a sudden drop at 0.2917 h, predicting the failure approximately 48.24 s in advance. In comparison to intact rock samples without freeze-thaw cycles, the presence of pre-existing fractures leads to an earlier prediction of failure through b-values, while freeze-thaw cycles delay the prediction of failure, suggesting that the presence of pre-existing fractures is effective in predicting rock sample failure, while freeze-thaw cycles impact the predictive ability, causing a delay in predicting the failure time.

Through the above analysis, it is evident that the AE b-values of the intact rock subjected to 90 freeze-thaw cycles, the intact unfrozen rock, and the fractured unfrozen rock all play a predictive role in the rock’s failure. They respectively anticipated failure by 12.96s, 35.28s, and 48.24s earlier than strain-based failure. The AE b-values effectively serve as a precursor indicating the unstable failure of the rock during creep, providing valuable early warning information for rock creep failure. However, this study does not consider the effect of actual engineering confining pressure. Follow-up research can focus on the acoustic emission characteristics of fractured rock mass under freeze-thaw conditions under confining pressure.

Damage evolution mechanism of fractured rock under freeze-thaw cycles

The experimental results reveal the coupling mechanism between freeze-thaw cycles, fracture geometry, and creep-AE responses. When water freezes within the 13.35% porosity of red sandstone, the 9% volumetric expansion generates cyclic frost heaving pressure that progressively damages the rock microstructure. This process creates new microcrack networks, weakening grain boundaries and cement bonds, which explains the exponential growth in AE energy rate under initial loading (Figs. 8 and 9) and the 52% reduction in peak energy rate after 90 freeze-thaw cycles.

Figure 20 illustrates the microscale freeze-thaw damage mechanism in double-fractured rock. The blue dots represent ice crystals formed within the rock pores, orange arrows indicate frost heave forces generated by 9% volumetric expansion, and red arrows show the resulting crack propagation directions. This schematic demonstrates how water-ice phase transitions within the 13.35% porosity generate cyclic damage that initiates microcracks preferentially along pre-existing fractures.

Pre-existing fractures fundamentally alter the stress distribution and failure mechanism. The gentle-gentle (15°-15°) configuration creates overlapping stress concentration zones at fracture tips, promoting tensile wing crack initiation with high AE activity (420 aJ/s peak energy rate, 90 dB maximum amplitude). Conversely, steep-steep (75°-75°) fractures align with the principal stress direction, accommodating deformation primarily through frictional sliding rather than new crack formation, resulting in lower AE emissions (90 aJ/s, 72 dB). This sliding mechanism paradoxically enhances stability despite larger deformations, as it provides stress relief pathways that prevent excessive stress concentration.

Figure 21 presents the mesoscale failure pattern evolution under different freeze-thaw cycles. The progressive damage from (a) 0 cycles showing localized cracking to (d) 90 cycles exhibiting extensive damage zones reveals how freeze-thaw action transforms failure modes from brittle to more ductile behavior. The red arrows indicate crack propagation directions, demonstrating the transition from concentrated to distributed damage patterns.

The three-stage creep evolution reflects distinct micromechanical processes captured by AE parameters. During deceleration creep, microcrack compaction causes b-value increases in unfrozen samples, while freeze-thaw damaged samples show fluctuating b-values due to heterogeneous damage distribution. The constant-rate stage represents dynamic equilibrium between crack generation and arrest, with near-zero AE energy rates indicating minimal new damage. The transition to acceleration creep, marked by sharp b-value drops (12.96–48.24 s before failure), signals crack coalescence and localized macro-fracture formation. The exponential AE energy increase and U-shaped amplitude distribution during this stage reflect avalanche-like crack propagation preceding catastrophic failure.

Figure 22 depicts the macroscale creep-AE response and failure precursor identification for the 15°-15° fractured rock sample. The synchronized evolution of axial strain (black), AE energy rate (red), and b-value (blue) clearly shows the three creep stages. The failure precursor zone (dashed box) highlights the critical 48.24 s warning period characterized by sharp b-value drop and exponential AE energy increase, providing quantitative basis for early warning systems.

The synergistic effects of freeze-thaw damage and pre-existing fractures create competing mechanisms that control failure precursors. Freeze-thaw cycles generate diffuse damage fields that delay localization, reducing b-value warning time from 35.28 s (unfrozen) to 12.96 s (90 cycles). Pre-existing fractures, however, create preferential failure paths that concentrate damage evolution, extending precursor time to 48.24 s. This interaction demonstrates that freeze-thaw damage masks early localization signals while fractures channel the failure process along specific paths, highlighting the importance of considering multiple damage mechanisms for accurate stability assessment in cold region engineering.

Conclusion

The present study focuses on intact red sandstone and red sandstone with pre-existing double fracture at varying inclinations. Single-axis compression AE tests and creep AE tests were conducted after freeze-thaw cycles. The research aimed to analyze the influence of freeze-thaw cycles and fracture inclinations on the mechanical failure characteristics, creep properties, and AE features of the rock. The study explores the rock creep failure patterns, the variation of b-values during the loading process, and conducts an analysis of the identification and differences in the precursory information of rock creep failure. The following conclusions were drawn:

-

(1)

Freeze-thaw cycles have a significant impact on both the instantaneous strain and creep strain of rocks. Instantaneous strain and creep strain increase with the number of freeze-thaw cycles, but the rate of increase in instantaneous strain gradually decreases and tends to stabilize. The increase in freeze-thaw cycles leads to higher amplitudes and AE energy rates, but this effect diminishes gradually with the increase in stress loading levels. Freeze-thaw action accelerates the fluctuation rate of b-values, causing the b-value to shift from an increasing trend to a decreasing trend during the deceleration creep stage, and the development of internal microcracks in the rock shifts from being predominantly small-scale to large-scale.

-

(2)

Under the same stress level, an increase in fissure inclination leads to a rapid increase in creep strain with the increase in stress level, while instantaneous strain exhibits linear growth with stress level. An increase in fracture inclination results in a significant decrease in amplitude and AE energy rate, indicating that with an increase in fissure inclination, the process of crack extension and penetration during rock creep tends to stabilize and become continuous, enhancing rock stability. A decrease in the inclination of double fissures reduces the stability of the rock specimen and accelerates the fluctuation of b-values during the deceleration creep stage.

-

(3)

The presence of pre-existing fissures leads to an earlier prediction of failure time based on b-values, while the influence of freeze-thaw cycles delays the prediction of failure time based on b-values. AE b-values from intact rock specimens subjected to 90 freeze-thaw cycles, intact non-freeze-thaw rock specimens, and fissured non-freeze-thaw rock specimens all played a predictive role in rock failure, advancing the prediction by 12.96s, 35.28s, and 48.24s, respectively, compared to strain-based predictions. AE b-values can effectively indicate the imminent failure of rocks during the creep process, serving as a valuable precursor information for rock creep failure.

-

(4)

The multi-scale damage evolution mechanism reveals that freeze-thaw cycles induce diffuse microcrack networks through cyclic frost heaving (9% ice expansion), while pre-existing fractures create stress concentration zones that control failure paths. The coupling between these mechanisms determines the creep-AE response: gentle fractures (15°) promote tensile crack growth with high AE activity (420aJ/s peak), while steep fractures (75°) accommodate deformation through sliding with lower emissions (90aJ/s). This mechanistic understanding explains why freeze-thaw damage reduces precursor warning time while fractures extend it, providing theoretical guidance for developing risk assessment strategies in cold region rock engineering.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Orheim, A. Coal resources in Arctic areas outside USSR. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 7, 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-232X(83)90064-2 (1983).

Prowse, T. D. et al. Implications of climate change for economic development in Northern canada: energy, resource, and transportation sectors. AMBIO: J. Hum. Environ. 38 (5), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-38.5.272 (2009).

Webster, K. L., Beall, F. D., Creed, I. F. & Kreutzweiser, D. P. Impacts and prognosis of natural resource development on water and wetlands in canada’s boreal zone. Environ. Rev. 23 (1), 78–131. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2014-0063 (2015).

Samylovskaya, E., Makhovikov, A., Lutonin, A., Medvedev, D. & Kudryavtseva, R. E. Digital technologies in Arctic oil and gas resources extraction: global trends and Russian experience. Resources 11 (3), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030029 (2022).

Carlson, R. F., Zarling, J. P. & Link, L. E. Cold regions engineering research—Strategic plan. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 3 (4), 172–190. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0887-381X (1989).

Aho, J. L. et al. An examination of resource transportation alternatives in Northwest Alaska. In Cold Regions Engineering: Cold Regions Impacts on Transportation and Infrastructure 182–193 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1061/40621(254)15.

Vasiliev, N. K., Pronk, A. D. C., Shatalina, I. N., Janssen, F. H. M. E. & Houben, R. W. G. A review on the development of reinforced ice for use as a Building material in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 115, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2015.03.006 (2015).

Crampin, S. & Gao, Y. Two species of microcracks. Appl. Geophys. 11 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11770-014-0415-7 (2014).

Matsuoka, N. & Murton, J. Frost weathering: recent advances and future directions. Permafrost Periglac. Process. 19 (2), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.620 (2008).

Liu, T. et al. Freeze-thaw damage evolution of fractured rock mass using nuclear magnetic resonance technology. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 170, 102951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2019.102951 (2020).

Ma, L. & Daemen, J. An experimental study on creep of welded tuff. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 43 (2), 282–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2005.07.002 (2006).

Sabitova, A. et al. Experimental compaction and dilation of porous rocks during triaxial creep and stress relaxation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54, 5781–5805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02562-4 (2021).

Cirone, A. & Vargas, E. Jr A thermodynamic modeling of creep in rock salt. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 162, 105298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2022.105298 (2023).

Gutiérrez-Ch, J. G. et al. Discrete element modelling of rock creep behaviour using rate process theory. Can. Geotech. J. 58 (8), 1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2020-0124 (2021).

Tarifard, A., Görög, P. & Török, Á. Long-term assessment of creep and water effects on tunnel lining loads in weak rocks using displacement-based direct back analysis: an example from Northwest of Iran. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energy Geo-resources. 8 (1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-022-00342-0 (2022).

Delchiaro, M., Della Seta, M., Martino, S., Nozaem, R. & Moumeni, M. Tectonic deformation and landscape evolution inducing mass rock creep driven landslides: the Loumar case-study (Zagros fold and thrust Belt, Iran). Tectonophysics 846, 22965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2022.229655 (2023).

Mousavi, S. Z. S., Tavakoli, H., Moarefvand, P. & Rezaei, M. Assessing the effect of freezing-thawing cycles on the results of the triaxial compressive strength test for calc-schist rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 123, 104090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.104090 (2019).

Park, J., Hyun, C. U. & Park, H. D. Changes in microstructure and physical properties of rocks caused by artificial freeze–thaw action. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 74, 555–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-014-0630-8 (2015).

Kolay, E. Modeling the effect of freezing and thawing for sedimentary rocks. Environ. Earth Sci. 75, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-5005-3 (2016).

Aral, İ. F., Boy, R. & Dinçer, A. R. Effects of freeze-thawing cycles on the physical and mechanical properties of basaltic and dolomitic rocks evaluated with a decay function model. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 2955–2962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-021-02132-6 (2021).

Fakhri, D. et al. T. Forecasting failure load of sandstone under different Freezing-Thawing cycles using Gaussian process regression method and grey Wolf optimization algorithm. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 125, 103876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.103876 (2023).

Yahaghi, J., Liu, H., Chan, A. & Fukuda, D. Experimental and numerical studies on failure behaviours of sandstones subject to freeze-thaw cycles. Transp. Geotechnics. 31, 100655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2021.100655 (2021).

Askaripour, M., Saeidi, A., Mercier-Langevin, P. & Rouleau, A. A review of relationship between texture characteristic and mechanical properties of rock. Geotechnics 2 (1), 262–296. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics2010012 (2022).

Tobler, D. J., Minto, J. M., Mountassir, E., Lunn, G., Phoenix, V. R. & R. J., & Microscale analysis of fractured rock sealed with microbially induced CaCO3 precipitation: influence on hydraulic and mechanical performance. Water Resour. Res. 54 (10), 8295–8308. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR023032 (2018).

Bauer, J. F., Meier, S. & Philipp, S. L. Architecture, fracture system, mechanical properties and permeability structure of a fault zone in lower triassic sandstone. Up. Rhine Graben Tectonophysics. 647, 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2015.02.014 (2015).

Major, J. R., Eichhubl, P., Dewers, T. A. & Olson, J. E. Effect of CO2–brine–rock interaction on fracture mechanical properties of CO2 reservoirs and seals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 499, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2018.07.013 (2018).

Kluge, C., Blöcher, G., Barnhoorn, A. & Bruhn, D. Hydraulic-mechanical properties of microfaults in granitic rock using the Punch-Through shear test. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 134, 104393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104393 (2020).

Ali, M. et al. Analytical damage model for predicting coal failure stresses by utilizing acoustic emission. Sustainability 15 (2), 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021236 (2023).

Carrasco, Á., Méndez, F., Leaman, F. & Molina Vicuña, C. Short review of the use of acoustic emissions for detection and monitoring of cracks. Acoust. Australia 49, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40857-021-00219-4 (2021).

Rodríguez, P. T. B. Celestino application of acoustic emission monitoring and signal analysis to the qualitative and quantitative characterization of the fracturing process in rocks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 210, 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.06.027 (2019).

Khoshouei, M. & Bagherpour, R. Application of acoustic emission (AE) in mining and Earth sciences: a review. Rudarsko-geološko-naftni Zbornik. 34, 4. https://doi.org/10.17794/rgn.2019.4.3 (2019).

Munoz-Ibanez, A., Delgado-Martín, J., Herbón-Penabad, M. & Alvarellos-Iglesias, J. Acoustic emission monitoring of mode I fracture toughness tests on sandstone rocks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 205, 108906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108906 (2021).

Petružálek, M. et al. Fracturing of migmatite monitored by acoustic emission and ultrasonic sounding. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-018-1590-2 (2019).

Ebrahimian, Z., Ahmadi, M., Sadri, S., Li, B. Q. & Moradian, O. Wavelet analysis of acoustic emissions associated with cracking in rocks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 217, 106516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2019.106516 (2019).

Manthei, G. Application of the cluster analysis and time statistic of acoustic emission events from tensile test of a cylindrical rock salt specimen. Eng. Fract. Mech. 210, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.05.039 (2019).

Tang, L. et al. A nonlinear viscoelastic-plastic creep constitutive model of soil-rock mixture-concrete interface under freeze-thaw cycles. Res. Cold Arid Reg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcar.2025.02.007 (2025).

Wei, Y. & Peng, H. Creep tests and fractional creep damage model of saturated frozen sandstone. Water 17 (16), 2492. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17162492 (2025).

Cao, J. et al. Mechanical properties and acoustic emission characteristics of mixed granite after different numbers of freeze–thaw cycles. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 14074. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65008-1 (2024).

Kefayati, S., Eftekhari, M., Goshtasbi, K. & Ahmadi, M. Evaluating shear strength and acoustic emission in rock-like materials with non-persistent joint geometries under freeze-thaw conditions. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 20488. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07943-1 (2025).

Wang, H., Xie, F., Fu, X., Wang, Y. & Yin, Z. An investigation of the effect of fissure inclination on specimen deformation and the damage mechanism based on the DIC method. Buildings 15 (5), 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050713 (2025).

Bi, R. & Gan, W. Study on the mechanical properties and interaction mechanism of fractured rock subjected to Freeze–Thaw cycles. Appl. Sci. 15, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15084101 (2025).

Li, Y. & Huang, D. Fracturing behavior and damage model of spatial-rotation fissured sandstone: an experimental study on freeze–thaw and fatigue loads coupling. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 131, 104448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2024.104448 (2024).

Yang, D., Duan, X., Cheng, K., Xie, L. & Song, Y. Research on creep characteristics of double fractured rock under freeze-thaw action. PLoS One. 20 (5), e0320194. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0320194 (2025).

Jielong, S., Rui, C., Yu, W., Wenbo, L. & Bing, L. Experimental study on creep characteristics of fractured surrounding rock in straight wall semi-circular arch roadways after thawing. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 105112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2025.105112 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 42277182,42377187).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: Dengke Yang: Conceptualization, literature review, methodology, result analysis, article drafting; Xiaoxiao Duan: software development, literature review, data curation; Keyan Cheng: investigation, validation; Lijun Xie: supervision; Hongjun Jing: laboratory and equipment coordination, experimental guidance; Yongjun Song: conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing – review and editing; Jianxi Ren: methodology, project administration, supervision, writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, D., Duan, X., Cheng, K. et al. Creep acoustic emission characteristics and failure precursor identification of double-fissured red sandstone under freeze–thaw action. Sci Rep 15, 41362 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25331-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25331-7