Abstract

In Kashgar, Xinjiang, China, skin cancer accounts for 51% of head and neck malignant tumors, and the incidence rate of head and neck skin cancer in this region is much higher than the national average level. This current situation highlights the necessity of risk prediction. This study retrospectively analyzed 1,156 participants from the 2015–2024 Kashgar Facial Skin Health Survey. The study employed logistic regression to screen for risk factors, and through sensitivity analysis, finally identified 8 factors that are independently associated with a high risk of skin cancer. This study developed a nomogram model for head and neck skin cancer incorporating a variety of risk factors. Key findings revealed that individuals with frequent cosmetics use, long-term high-fat diet, inadequate vegetable intake, lip-biting habit, scratching habit, smoking behavior, prolonged outdoor exposure, and those who do not wear hats have a significantly increased risk of head and neck skin cancer. The model was evaluated using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (with Area Under the Curve, AUC), calibration curves, and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA). The results showed that the model exhibited good reliability and accuracy in both groups, and possessed high clinical value within specific threshold ranges. In conclusion, this nomogram model can assist clinicians in identifying high-risk individuals for head and neck skin cancer, and provide guidance for the prevention efforts of head and neck skin cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skin cancer, recognized as the most prevalent malignant neoplasm worldwide, has experienced a notable increase in the incidence of new cases across various regions over the past few decades, indicating a concerning upward trend1. Although the head and neck region constitutes approximately 9% of the total skin surface area, it exhibits a disproportionately high incidence of skin cancer2. Notably, the skin in these areas is characterized by a high density of hair follicles and sebaceous glands, as well as increased exposure to environmental factors when compared to the skin of the trunk or extremities3.The repercussions of skin cancer, particularly in the head and neck region, encompass facial deformities, impairments in eating functions, and visual disabilities, thereby exacerbating the overall disease burden associated with cancer4. Over the 10-year period from 2015 to 2024, our statistical data indicate that skin cancer cases in the Kashgar region of Xinjiang comprised 51% of all head and neck malignant tumors.This raises our concern.Based on 445 cases of head and neck skin cancer and a total resident population of 4.6 million in Kashgar Prefecture from 2015 to 2024, the annual crude incidence rate was calculated using the Poisson distribution χ² approximation method, resulting in a rate of 9.67 per 100,000 population (95% confidence interval: 8.99–10.39 per 100,000 population). According to the 2017 national cancer registration data from the National Cancer Center (covering 436 million people), the annual crude incidence rate of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in China was 2.59 per 100,000 population5, which is significantly lower than that in high ultraviolet (UV) exposure areas. The annual average UV index in Kashgar Prefecture reaches 7.8, which is classified as “extremely high risk” by the World Health Organization (WHO) and serves as a key environmental factor contributing to the high incidence of skin cancer. Local data show that patients with head and neck skin cancer have an average annual medical cost of approximately 12,000 RMB, and 34.5% of these patients lose their labor capacity due to facial deformities6. This further exacerbates regional health inequities, thus highlighting an urgent need for practical risk prediction tools.

Previous evidence-based medical evidence has shown that persistent outdoor exposure and excessive ultraviolet (UV) radiation are important high-risk factors for the occurrence of skin cancer7. The selection of skin care products and the application of cosmetics are also significantly correlated with the occurrence and development process of skin cancer. Multiple studies have suggested that the dietary structure and nutritional intake patterns may have a potential impact on the risk of developing skin cancer8.Meanwhile, bad behavioral habits such as smoking, alcohol abuse, and repeated scratching of the skin can significantly increase the risk of suffering from skin cancer. In addition, the results of epidemiological surveys based on large samples have shown that demographic characteristics such as gender, age, skin color, skin type, and race are closely related to the risk of developing skin cancer9.It is worth noting that recent studies have indicated that an individual’s cognitive level and degree of attention to skin lesions play an important regulatory role in the malignant transformation process of skin lesions into skin cancer10. Most previous studies have focused on the association between a single risk factor and skin cancer development. However, systematic research that integrates multi-dimensional potential risk factors such as environmental exposure, lifestyle, and individual biological characteristics to predict the risk of skin cancer in the head and neck region remains lacking.The occurrence of skin cancer is a complex pathological process resulting from the synergistic effects of multiple factors, including genetic susceptibility, environmental exposure, behavioral habits, and individual physiological differences. Constructing a comprehensive prediction model that encompasses multi-dimensional risk elements can not only enable the early and accurate identification of high-risk individuals for skin cancer in the population but also facilitate the implementation of targeted intervention measures during the critical window period of disease development. This can effectively reduce the disease burden of skin cancer in the head and neck region, alleviate the psychological stress caused by facial disfigurement and functional impairment in patients, and ultimately improve the quality of life and prognosis of patients.

Currently, nomograms and decision curve analysis, as highly innovative predictive model methods, can achieve accurate prediction of the probabilities of clinical events and specific prognostic outcomes by virtue of the in-depth integration of multi-dimensional predictive factors and the establishment of a visual statistical prediction system11,12. This technological innovation has opened up an intuitive, efficient, and quantifiable new paradigm for disease risk prediction.Against the backdrop of this disciplinary development, the development of nomogram and decision curve models tailored to skin cancer in the head and neck region can not only assist clinicians in achieving early and accurate identification of high-risk populations through a scientifically quantified risk assessment system, but also enable the formulation of step-by-step and precise intervention plans based on individualized risk values. However, it cannot be ignored that in the field of predicting skin cancer in the head and neck region, risk prediction models with both high sensitivity and reliability are still in a severely scarce state. It is urgent for the academic community to conduct systematic explorations focusing on directions such as multi-source data integration and model optimization algorithms to promote innovative breakthroughs in prediction technologies.

Based on this, this study systematically explored the risk factors of skin cancer in the head and neck region. Relying on the large-scale sample data from the Skin Health Survey Project in Kashgar Prefecture, Xinjiang from 2015 to 2024, an innovative risk prediction model was constructed.Firstly, the study applied the logistic regression analysis method to systematically screen the potential risk factors and selected the key influencing factors with a high goodness of fit. Subsequently, a nomogram model encompassing all-dimensional predictive elements was developed and validated, enabling precise quantitative prediction of the incidence probability of skin cancer in the head and neck region. Finally, through Decision Curve Analysis (DCA), the effectiveness and practicality of the model were verified from the perspective of clinical application value.This model can not only efficiently screen out high-risk individuals for skin cancer in the population but also provide a scientific basis for clinicians to formulate personalized early intervention strategies. Thereby, it can effectively reduce the disease burden of patients with skin cancer in the head and neck region and alleviate their psychological stress, possessing important clinical application value and public health significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics

According to the set inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, a total of 1,156 participants were included in this study. The average age of all the included participants was 67 ± 9 years old, among which 53.52% were male and 46.48% were female. 70% of the eligible participants were randomly assigned to the model construction group (809), and the remaining 30% were assigned to the model validation group (347). Among all the 1,156 participants, there were 445 skin cancer patients, including 316 in the model construction group and 129 in the model validation group(see Table 1).

According to clinical experience and literature retrieval, we included 23 potential predictors in the logistic regression analysis. After excluding collinearity, the logistic regression finally screened out 15 risk factors with a P-value less than 0.05 (including Age, Early skin lesions, Sunscreen, Moisturizer, High fat diet, Enough vegetable intake, Habit of wearing hat, Lip-biting habits, Scratching habits, Smoking, Prolonged outdoor exposure, Humidifier, Heating, Correct understanding of skin lesion, The right treatment for skin lesion; see Table 1).

Clinical predictor selection

To address potential reverse causality bias (since “Correct understanding of skin lesion” and “The right treatment for skin lesion” are post-diagnosis behaviors, not pre-onset risk factors), sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding these two variables from the initial multivariate model. Table 2 compares logistic regression results of the full model (with reverse causality variables) and simplified model (without these variables) for head and neck skin cancer risk factors.

In the full model (left two columns: OR, P), 9 variables were significantly associated with the outcome (all P < 0.05), including Cosmetics (yes: OR = 13.899), High fat diet (yes: OR = 1.850), Enough vegetable intake (yes: OR = 0.401), Lip-biting habits (yes: OR = 1.571), Scratching habits (yes: OR = 3.244), Smoking (yes: OR = 3.460), Prolonged outdoor exposure (yes: OR = 2.860), “Correct understanding of skin lesion” (yes: OR = 0.055), and “The right treatment for skin lesion” (yes: OR = 0.453). However, “Habit of wearing hat (yes)” showed no significant protective effect (OR = 0.768, P = 0.643), possibly masked by bias.

In the simplified model (right two columns: OR, P), 8 independent risk/protective factors with more accurate effect sizes were identified: Risk factors (OR > 1, P < 0.05): Cosmetics (yes: OR = 5.056, overestimated risk corrected), High fat diet (yes: OR = 2.483, effect strengthened), Lip-biting habits (yes: OR = 1.483), Scratching habits (yes: OR = 3.176), Smoking (yes: OR = 3.551), Prolonged outdoor exposure (yes: OR = 2.781); Protective factors (OR < 1, P < 0.05): Enough vegetable intake (yes: OR = 0.402), Habit of wearing hat (yes: OR = 0.070, now significant, risk reduction rate up to 93%).

Other variables (Age, Early skin lesions, Sunscreen, Humidifier, Heating) were non-significant in both models (all P > 0.05). Detailed OR, 95% CI, and P values are in Table 2.

Model development, validation, and sensitivity analysis

Development and validation of the full predictive nomogram (9 Factors)

To initially explore the risk association of multi-dimensional factors with head and neck skin cancer, a full predictive nomogram was constructed based on multivariate logistic regression results, incorporating 9 variables: Cosmetics use, High-fat diet, Adequate vegetable intake, Lip-biting habits, Scratching habits, Smoking, Prolonged outdoor exposure, Correct understanding of skin lesions, and Standardized treatment of skin lesions.

On the nomogram, each predictor was assigned a specific score: factors with a status change from “0 (absent)” to “1 (present)” (risk factors) received positive scores, while those with a change from “1 (present)” to “0 (absent)” (protective factors) received negative scores. Clinicians can calculate the total score by summing the scores of individual variables based on patient information, then draw a vertical line downward from the total score on the “Total Points” axis—the intersection with the “Risk” axis represents the individual’s predicted probability of head and neck skin cancer (higher score = higher risk; Fig. 1).

Nomogram for predicting the risk of head and neck skin cancer. This nomogram incorporates 9 predictive factors. Model Usage Instructions: For factors where the status changes from “0” (absent) to “1” (present), positive scores are assigned; for factors where the status changes from “1” (present) to “0” (absent), negative scores are assigned. First, calculate the total score by summing the scores of each factor based on the patient’s actual situation. Mark the total score on the “Total Points” axis, then draw a vertical line downward from this mark. The intersection of this vertical line with the “Risk” axis represents the predicted probability of the patient developing head and neck skin cancer. Specific scores for each factor: Cosmetics (83), High fat diet (21), Enough vegetable intake (-25), Lip-biting habits (14), Scratching habits (36), Smoking (39), Prolonged outdoor exposure (34), Correct understanding of skin lesion (-100), The right treatment for skin lesion (-24).

Validation results of the full nomogram showed:

Discriminative ability: The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) was 0.872 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.848–0.895) in the training cohort (Fig. 2A), and 0.885 (95% CI: 0.849–0.921) in the 30% random internal validation cohort (Fig. 2B), indicating good overall discriminative performance.

Performance verification plots of the original nomogram. (A) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the original nomogram in the training cohort, with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.872 (95% confidence interval: 0.848–0.895; (A, B) ROC curve of the original nomogram in the validation cohort, with an AUC of 0.885 (95% confidence interval: 0.849–0.921; (B, C) Calibration curve of the original nomogram in the training cohort (evaluating the agreement between predicted and actual risks); (D) Calibration curve of the original nomogram in the validation cohort; (E) Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) of the original nomogram in the training cohort (comparing the model’s net benefit with “screen all” and “screen none” strategies); (F) DCA of the original nomogram in the validation cohort.

Calibration: After 1000 Bootstrap resamplings, the calibration curve in the training cohort showed good agreement between predicted and actual risks (Fig. 2C); consistent good calibration was also observed in the validation cohort (Fig. 2D).

Clinical utility: Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) revealed positive net benefits only within fragmented risk threshold ranges (1%–91%, 94%–95%, 98%–99%) in the training cohort (Fig. 2E), and a wider but still limited range (3%–99%) in the validation cohort (Fig. 2F). Notably, the protective effect of “Habit of wearing hat” (a key factor consistent with Kashgar’s high UV environment) was not statistically significant in this model (OR = 0.768, P = 0.643; Table 2), suggesting potential bias interference.

Sensitivity analysis and validation of the simplified nomogram (8 Factors)

Considering that “Correct understanding of skin lesions” and “Standardized treatment of skin lesions” are post-diagnosis behaviors (not pre-onset risk factors) and may introduce reverse causality bias, sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding these two variables from the initial multivariate model. Re-conducted multivariate logistic regression identified 8 independent risk/protective factors, and a simplified nomogram was constructed (Fig. 3), including: Cosmetics use, High-fat diet, Adequate vegetable intake, Habit of wearing hat, Lip-biting habits, Scratching habits, Smoking, and Prolonged outdoor exposure. Each factor’s “presence (coded ‘1’)”/“absence (coded ‘0’)” corresponds to a specific score, and the total score maps to a predicted risk probability (0.01–0.99).

Nomogram of the simplified model for predicting head and neck skin cancer risk. This simplified model was constructed after excluding reverse causality variables (“Correct understanding of skin lesion” and “The right treatment for skin lesion”), and includes 8 core risk factors: Cosmetics, High fat diet, Enough vegetable intake, Habit of wearing hat, Lip-biting habits, Scratching habits, Smoking, and Prolonged outdoor exposure. Model Usage Instructions: Sum the corresponding scores based on an individual’s variable status (“0” = absent, “1” = present). Mark the total score on the “Total Points” axis, then draw a vertical line downward; the intersection with the “Risk” axis is the predicted risk of head and neck skin cancer. Specific scores for each factor: Cosmetics (61), High fat diet (27), Enough vegetable intake (-32), Habit of wearing hat (-100), Lip-biting habits (15), Scratching habits (43), Smoking (46), Prolonged outdoor exposure (40).

To facilitate clinical application, an Excel spreadsheet (Supplementary file 1) was developed based on this simplified nomogram—automatic calculation of a patient’s head and neck skin cancer risk can be achieved by inputting (checking) their information.

Final validation of the simplified nomogram using three approaches confirmed its superiority:

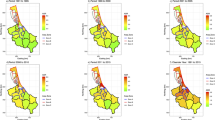

Discriminative ability: AUC remained high at 0.850 (95% CI: 0.824–0.876) in the training cohort and 0.865 (95% CI: 0.826–0.905) in the validation cohort (Fig. 4A and B), with only a slight decrease from the full model (attributed to bias elimination, not performance loss).

Performance verification plots of the simplified model (after excluding reverse causality variables). (A) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the simplified nomogram in the training cohort, with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.850 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.824–0.876); (B) ROC curve of the simplified nomogram in the validation cohort, with an AUC of 0.865 (95% CI: 0.826–0.905); (C) Calibration curves of the simplified nomogram in the training cohort, including apparent (red solid line), ideal (black dashed line), and bias-corrected (green solid line) curves (illustrating the agreement between predicted and actual risks); (D) Calibration curves of the simplified nomogram in the validation cohort (curve definitions consistent with Panel C); (E) Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) of the simplified nomogram in the training cohort; (F) DCA of the simplified nomogram in the validation cohort (curve definitions consistent with Panel E).

Calibration: Bias-corrected calibration curves (via 1000 Bootstrap resamplings) in both cohorts were close to the ideal line (y = x), indicating better consistency between predicted and actual risks than the full model (Fig. 4C and D).

Clinical utility: DCA showed the simplified model had positive net benefits within a continuous, wide risk threshold range in training cohort (1%–90%) and validation cohort (1%-99%), consistently outperforming the “screen all” and “screen none” strategies—addressing the fragmented threshold limitation of the full model and confirming higher clinical applicability (Fig. 4E and F).

Discussion

The incidence of head and neck skin cancer remains persistently high, imposing substantial physical and psychological burdens on patients due to disfigurement and metastatic risks13. Existing predictive models for skin cancer primarily focus on detecting established cancers14,15,16 rather than enabling early preventive screening tailored to unique head and neck risk factors, such as anatomical specificity, cosmetic use, and localized behavioral habits. This gap underscores the need for a comprehensive risk assessment system integrating lifestyle, environmental, and behavioral factors.

Our study developed a nomogram model for head and neck skin cancer, incorporating diverse risk factors. Key findings revealed that individuals with frequent cosmetic use, long-term high-fat diets, inadequate vegetable intake, lip-biting, scratching, smoking, prolonged outdoor exposure, and lack of the habit of wearing a hat exhibit significantly elevated risks (Table 2; Fig. 3). These factors were prioritized due to their unique relevance to the head and neck region, an area frequently exposed to cosmetics, mechanical trauma (e.g., lip-biting), and environmental stressors like ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

UV Radiation and Outdoor Exposure: Prolonged outdoor activity subjects the skin to intense UV radiation, causing irreversible DNA damage in epidermal cells17. Unrepaired damage leads to uncontrolled proliferation and malignant transformation. As the disease progresses, skin cancer may metastasize, threatening vital organs and severely reducing quality of life. This confirms outdoor exposure as a critical modifiable risk factor, emphasizing the need for sun protection strategies, the simplest and most practical one is to develop the habit of wearing a hat (Fig. 3).

Cosmetic Use and Skin Barrier Disruption: Improper cosmetic use emerged as a significant risk factor, accounting for substantial weight in the nomogram (Fig. 4). Mechanisms include: Direct toxicity from heavy metals/illegal additives in low-quality products, damaging the skin barrier and inducing DNA mutations18.Makeup residue from inadequate removal, triggering chronic inflammation and abnormal cell growth.Photochemical reactions of cosmetic components under UV light, exacerbating oxidative stress and tissue damage19.While moderate use of quality cosmetics remains unlinked to cancer, improper practices (e.g., prolonged use, poor removal) pose measurable risks, aligning with emerging research on chemical exposure and skin carcinogenesis20.

Dietary Habits and Inflammatory Microenvironment: High-fat diets alter the skin’s microenvironment, promoting inflammation and carcinogenesis, while insufficient vegetable intake deprives cells of antioxidants and fiber essential for repair. The nomogram quantifies these factors: high-fat intake as a risk (positive score)21,22,23 and vegetable consumption as protective (negative score)24, providing a clinical tool for dietary counseling.

Behavioral and Lifestyle Factors: Habits like lip-biting and scratching disrupt the epidermal barrier, increasing susceptibility to carcinogens, while smoking introduces chemical toxins (e.g., nicotine, tar) that poison cells and suppress immune surveillance25. Correcting these behaviors offers a direct pathway to reduce chronic skin damage and cancer risk26.

When the original model included 9 variables, the effects of some core factors were distorted by reverse causality bias. For instance, the habit of wearing a hat exhibited a weak protective effect with no statistical significance in the full model (OR = 0.768, P = 0.643); however, after excluding confounding variables, its key role in ultraviolet (UV) protection was significantly highlighted (OR = 0.07, P < 0.001), with the risk reduction rate corrected from 23.2% to 93%, which is highly consistent with the environmental characteristic of high UV exposure in Kashgar. The risk effect of cosmetics use decreased from 13.9-fold (OR = 13.899) in the original model to 5.06-fold (OR = 5.056), eliminating the interference of the reverse association of “reduced cosmetics use after diagnosis” and more truly reflecting the long-term irritating effect of low-quality cosmetics. In addition, the risk effect of a high-fat diet increased from 1.85-fold to 2.48-fold (P < 0.001), indicating that its independent role in promoting carcinogenesis through the inflammatory microenvironment becomes clearer after excluding the interference of treatment behaviors. These changes confirm that uncorrected reverse causality variables can lead to risk estimation bias, while sensitivity analysis can strip away such confounding effects.

The nomogram enables clinicians to calculate individual risk scores using patient interviews and medical data. For example, a 55-year-old male with a high-fat diet, lip-biting, scratching habits smoking, and chronic sun exposure scored 171 points, indicating a 50% probability of head and neck skin cancer (Excel spreadsheet(Supplementary File 1)). This facilitates targeted interventions: educating on lesion monitoring, advising dietary/lifestyle changes, and prioritizing regular screenings for high-risk individuals.

Limitations and future directions

While the constructed nomogram demonstrates promising clinical utility for head and neck skin cancer risk prediction in Kashgar, several limitations of this study require explicit acknowledgment to ensure a comprehensive understanding of its scope and generalizability.

First, limitations related to data source, regional representativeness, and study design are notable. All samples were collected exclusively from the First People’s Hospital of Kashgar Prefecture, rendering this a single-center study. The participant cohort primarily included Uyghur (91.7%) and Han (8.3%) ethnic groups in Kashgar (Table 1), with no data integrated from other regions in Xinjiang or other high-incidence areas across China. This geographic homogeneity—coupled with the study’s retrospective design—introduces dual constraints: on one hand, the regional restriction may limit the external validity of the nomogram; on the other hand, reliance on retrospective questionnaire data for variables like lifestyle and exposure history may introduce recall bias, while the single-center sampling framework could potentially introduce selection bias, both of which may affect the model’s generalizability to broader populations.

Second, omission of key variables compromises the model’s comprehensiveness. This study did not integrate several clinically relevant factors that may influence head and neck skin cancer risk. Genetically, potential susceptibility factors such as CDKN2A or MC1R gene mutations—well-documented contributors to cutaneous melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer risk27,28—were not included, nor were detailed pathological classifications29 or imaging data30 that could refine risk stratification. Occupationally, long-term exposure to chemical carcinogens or prolonged ultraviolet exposure from outdoor occupations was also not assessed; These omissions may lead to underrepresentation of high-risk subgroups, narrowing the model’s predictive scope.

To address these limitations and enhance the model’s robustness, future studies should prioritize multi-dimensional improvements. Prospective, multi-center collaborations are essential: integrating data from other regions in Xinjiang and national high-incidence areas will validate the nomogram’s external validity and optimize it for diverse populations. Additionally, incorporating genomic data (e.g., testing for CDKN2A, MC1R mutations), detailed pathological assessments, and imaging findings will enrich the model’s predictive variables. For occupational exposure, designing standardized assessment tools (capturing job type, exposure duration, and chemical types) will reduce bias and improve data reliability. These adjustments will not only strengthen the model’s accuracy and comprehensiveness but also extend its clinical utility to a wider range of populations, better serving public health efforts for head and neck skin cancer prevention.

This novel nomogram model addresses the unmet need for early preventive screening in head and neck skin cancer, emphasizing region-specific risk factors like cosmetic use, behavioral habits, and UV exposure. By quantifying modifiable risks, it empowers clinicians to deliver personalized prevention strategies, potentially reducing morbidity through proactive intervention. While requiring further validation, the model represents a critical step toward integrating lifestyle and environmental factors into clinical risk assessment, fostering a more holistic approach to skin cancer prevention.

Methods

Study design

This was a case-control study, and the data were sourced from the Skin Health Survey Project in Kashgar Prefecture, Xinjiang (a dataset spanning the ten-year period from 2015 to 2024). Ethical approval was received from Ethics Committee of the First People’s Hospital of Kashgar (Reference No. [2023] Review No. (64)). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before study commencement.The roadmap of the experimental design is as follows (Fig. 5).

Flowchart of nomogram development (including sensitivity analysis). A total of 2,339 samples were extracted from the 2015–2024 Kashgar Prefecture (Xinjiang) Skin Health Survey dataset. After excluding 1,183 samples with incomplete data or unmet eligibility criteria, 1,156 qualified samples remained (445 head and neck skin cancer patients, 711 healthy individuals). Stratified random sampling was used to assign 70% of samples from both the patient and healthy groups to the model development cohort (n = 809, 316 patients + 493 healthy individuals), where predictive factor analysis and risk factor screening were conducted to construct an initial nomogram. The remaining 30% of samples (n = 347, 129 patients + 218 healthy individuals) formed the validation cohort, used to verify the model via AUC, calibration curve, and DCA. Sensitivity analysis was then performed to exclude reverse causality variables, and a final simplified nomogram for head and neck skin cancer risk prediction was generated.

The total number of participants in this study was 2,339, among which 445 skin cancer cases were all pathologically confirmed patients. Relying on the standardized medical record management of hospitals, the data of all predictor variables (such as age, UV exposure history, etc.) were complete without missing values. The 1,183 cases of incomplete data excluded were all from the healthy population survey; the missing data were mainly due to incomplete questionnaire responses (e.g., recall bias regarding outdoor work duration). A comparison of the baseline characteristics (age, gender, urban-rural distribution, etc.) between the excluded and included healthy populations showed no statistically significant differences (all P-values > 0.05), indicating no introduction of selection bias.

Since there was no missing data in the case group and the missing samples in the healthy population did not affect the overall representativeness, the complete case analysis was temporarily adopted. To further improve data utilization in the future, multiple imputation method can be applied to the missing data of the healthy population to verify the robustness of the results.

Study population

From the Skin Health Survey Project in Kashgar Prefecture, Xinjiang from 2015 to 2024, a total of 2,339 participants were selected. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Skin cancer patients (confirmed by pathological examination); (2) Patients with skin cancer occurring in the head and neck region (defined as including the head, face, and neck). Participants with missing clinical data or incomplete clinical information of predictive variables and outcomes were excluded.

Eventually, a total of 1,156 participants were selected, including 445 patients with skin cancer and 711 healthy individuals. For model development and validation, we adopted a stratified random sampling strategy to ensure the representativeness of both the case and control groups—this involved randomly selecting approximately 70% of samples from each group to form the model construction set, and the remaining approximately 30% for the validation set.

To confirm that this minor adjustment did not introduce selection bias, we conducted baseline characteristic comparisons between the pre-sampling and post-sampling cohorts. Chi-square tests and t-tests revealed no statistically significant differences in all variables (all P > 0.05), verifying that the model construction set (n = 809, 316 + 493) and validation set (n = 347, 129 + 218) remained representative of the original total sample (Fig. 5).

Candidate predictor variables

According to clinical experience and literature review, we screened out the risk predictors that might affect the occurrence of skin cancer. These variables include: (1) Basic demographic information (such as ethnicity, gender, age). (2) Skin conditions (such as skin color, skin type, early skin lesions). (3) The usage of skin care products (Sunscreen) and cosmetics: defined as “frequent use” [coded “yes”] if using cosmetics [e.g., foundation, eyeshadow, lipstick, excluding basic moisturizers] ≥ 5 days/week, with daily wear time ≥ 4 h, and continuous use duration ≥ 1 year; “no” if usage does not meet the above criteria31. (4) Eating habits: including whether having a high-fat diet and the intake of vegetables, defined as “yes” if daily fat intake accounts for ≥ 30% of total energy intake [equivalent to ≥ 60 g cooking oil + ≥ 50 g animal fat daily] and continuous consumption ≥ 6 months, based on the Chinese Dietary Guidelines 201632; enough vegetable intake: defined as “inadequate” [coded “no”] if daily vegetable intake < 300 g [or weekly intake < 2100 g], with “adequate” [coded “yes”] as ≥ 300 g/day, referring to the recommended intake of the Chinese Nutrition Society32. (5) Daily behavioral habits (including the habit of wearing a hat and the frequency of washing the face). (6) Unhealthy behavioral habits (the habit of biting the lips, scratching the maxillofacial region, smoking, drinking alcohol, and prolonged outdoor exposure). (7) The situation of the family environment (including the use of humidifiers, air conditioners, and heaters). (8) The cognitive status of skin lesions (including correct understanding of skin lesion and right treatment for skin lesion).

Outcome assessment

The endpoint outcome of our study was defined as the occurrence of skin cancer in the head and neck region. The predefined skin cancer group was determined based on the questionnaire of the Skin Health Survey Project in Kashgar Prefecture, Xinjiang (2015–2024). The researchers asked the participants whether they had ever been told by a doctor or a professional that they had skin cancer in the head and neck region. To ensure the reliability of the diagnosis and avoid misclassification, participants who answered “Yes” underwent further verification through retrospective review of their medical records (including electronic medical records and paper-based case files from the hospitals where they received diagnosis and treatment). The diagnosis of head and neck skin cancer was ultimately confirmed by pathological examination—the gold standard for cancer diagnosis: lesion tissues of these participants were subjected to hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. Only participants whose head and neck skin cancer diagnosis was confirmed by pathological examination were finally classified into the predefined skin cancer group; the remaining population was defined as the “healthy group.” Among the 445 skin cancer patients ultimately included in this study, all (100%) were confirmed by pathological examination, which further ensures the accuracy and reliability of the study sample.

This study focuses on the identification of high-risk populations rather than the prediction of future incidence risk. The outcome measure adopts pathologically confirmed prevalent cases — this design not only aligns with the core value of case-control studies, which is “exploring risk factors and identifying high-risk groups”, but also ensures that the risk characteristics of prevalent cases are highly consistent with their pre-onset status, thanks to the population characteristics of Kashgar Prefecture (low population mobility and high stability of living habits). This provides a reliable basis for the clinical application of the tool.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables and categorical variables, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (when the theoretical frequency is less than 10) is used to conduct statistics on the categorical variables, which are presented in the form of frequencies and proportions in the table.

A risk prediction model for skin cancer in the head and neck region was constructed based on the logistic regression method. After excluding the collinearity among the included covariates, meaningful predictive risk factors were screened out. Risk factors with a P-value less than 0.05 were selected, and a nomogram prediction model was established.

To address potential reverse causality bias (where “Correct understanding of skin lesion” and “The right treatment for skin lesion” are post-diagnosis behaviors rather than pre-onset risk factors), sensitivity analysis was further performed: these two variables were excluded from the initial multivariate logistic regression model, and multivariate logistic regression was re-conducted to re-screen for independent risk factors associated with head and neck skin cancer, so as to verify the stability of effect sizes of core predictive factors and avoid the interference of bias on model reliability.

The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was used to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the nomogram. The calibration curve was employed to measure the predictive performance of the nomogram. To improve the accuracy and stability of the model, the 1000-time bootstrap resampling validation method was also adopted for internal validation. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical guiding practicality of the nomogram.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS23.0 software and R 4.1.2 software(The codes of the R program are in the Supplementary Materials_R Codes and Parameters(Supplementary file 2). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

STROBE statement

This study complies with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement for case-control studies. All core items of the STROBE checklist have been integrated into the manuscript, covering aspects such as participant selection (case definition and control recruitment), measurement of variables, bias control, and statistical analysis. A completed STROBE checklist for case-control studies is available in the related files (Related file 2). For full STROBE guidelines, refer to http://www.strobe-statement.org/.

TRIPOD statement

This study adheres to the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement. It aims to develop and validate a multivariable prediction model for head and neck skin cancer risk, using a case-control design (pathologically confirmed head and neck skin cancer cases and healthy controls). Key elements of the TRIPOD checklist relevant to this model have been addressed, including participant selection, definition of predictors, model development and validation methods (e.g., logistic regression, Bootstrap resampling), and assessment of model performance (e.g., AUC, calibration curves, Decision Curve Analysis). A completed TRIPOD checklist (adapted for case-control studies) is provided in the related files (Related file 1). For full TRIPOD guidelines, refer to https://www.tripod-statement.org/.

Data availability

Data are provided within the manuscript.

Code availability

The codes of the R program are in the supplementary file 2: Supplementary Materials_R Codes and Parameters.

References

Asadi, L. K., Khalili, A. & Wang, S. Q. The sociological basis of the skin cancer epidemic. Int. J. Dermatol. 62 (2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15987 (2023).

Roland, N. & Memon, A. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck. Br. J. Hosp. Med. (Lond). 84 (4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2021.0126 (2023).

Perez, M., Abisaad, J. A., Rojas, K. D., Marchetti, M. A. & Jaimes, N. Skin cancer: Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. Part I. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 87 (2), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.066 (2022).

Diao, X., Guo, C. & Jin, Y. Cancer situation in china: an analysis based on the global epidemiological data released in 2024. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 45 (2), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/cac2.12627 (2025).

Li, J., Zeng, J., Yang, Y. & Huang, B. Trend of skin cancer mortality and years of life lost in China from 2013 to 2021. Front. Public. Health. 13, 1522790. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1522790 (2025).

Liu, H. E. Changes of satisfaction with appearance and working status for head and neck tumour patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 17 (14), 1930–1938. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02291.x (2008).

Raimondi, S., Suppa, M. & Gandini, S. Melanoma epidemiology and sun exposure. Acta Derm Venereol. 100 (11), adv00136. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3491 (2020).

Martin-Gorgojo, A., Gilaberte, Y. & Nagore, E. Vitamin D and skin cancer: an epidemiological, patient-centered update and review. Nutrients 13 (12), 4292. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124292 (2021).

D’Arino, A., Caputo, S. & Eibenschutz, L. Skin cancer microenvironment: what we can learn from skin aging? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (18), 14043. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241814043 (2023).

Ji-Xu, A., Artounian, K. & Altman, E. M. Dermatology education resources on sun safety and skin cancer targeted at Spanish-speaking patients: A systematic review. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 315 (5), 1083–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-022-02465-6 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z., Wei, L. & Wei, S. Construction and validation of nomograms combined with novel machine learning algorithms to predict early death of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Front. Public. Health. 10, 1008137. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1008137 (2022).

Xing, L., Zhang, X., Zhang, X. & Tong, D. Expression scoring of a small-nucleolar-RNA signature identified by machine learning serves as a prognostic predictor for head and neck cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 235 (11), 8071–8084. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.29462 (2020).

Ibrahim, N. et al. The incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer in the UK and the Republic of ireland: A systematic review. Eur. J. Dermatol. 33 (3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2023.4496 (2023).

Kumar Lilhore, U., Simaiya, S. & Sharma, Y. K. A precise model for skin cancer diagnosis using hybrid U-Net and improved MobileNet-V3 with hyperparameters optimization. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 4299. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54212-8 (2024).

Hosseinzadeh, M., Hussain, D. & Zeki Mahmood, F. M. A model for skin cancer using combination of ensemble learning and deep learning. PLoS One. 19 (5), e0301275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301275 (2024).

Barata, C., Rotemberg, V. & Codella, N. C. F. A reinforcement learning model for AI-based decision support in skin cancer. Nat. Med. 29 (8), 1941–1946. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02475-5 (2023).

Lee, J. W., Ratnakumar, K., Hung, K. F., Rokunohe, D. & Kawasumi, M. Deciphering UV-induced DNA damage responses to prevent and treat skin cancer. Photochem. Photobiol. 96 (3), 478–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/php.13245 (2020).

Balwierz, R., Biernat, P. & Jasińska-Balwierz, A. Potential carcinogens in makeup cosmetics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 (6), 4780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064780 (2023).

Bennett, S. L. & Khachemoune, A. Dispelling Myths about sunscreen. J. Dermatolog Treat. 33 (2), 666–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2020.1789047 (2022).

Ludriksone, L. & Elsner, P. Adverse reactions to sunscreens. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 55, 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517634 (2021).

Ahmed, I. A. & Mikail, M. A. Diet and skin health: the good and the bad. Nutrition 119, 112350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2023.112350 (2024).

Michalak, M., Pierzak, M., Kręcisz, B. & Suliga, E. Bioactive compounds for skin health: A review. Nutrients 13 (1), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13010203 (2021).

Minton, K. High-fat diet depletes skin Treg cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23 (10), 616. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-023-00924-3 (2023).

Flores-Balderas, X., Peña-Peña, M. & Rada, K. M. Beneficial effects of plant-based diets on skin health and inflammatory skin diseases. Nutrients 15 (13), 2842. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132842 (2023).

Lipa, K. et al. Does smoking affect your skin? Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 38 (3), 371–376. https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2021.103000 (2021).

Zhao, C., Wang, X. & Mao, Y. Variation of biophysical parameters of the skin with age, gender, and lifestyles. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 20 (1), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13453 (2021).

Jay, R., Witkoff, B. & Ivanov, N. Utility of gene expression profiling in skin cancer: A comprehensive review. J. Drugs Dermatol. 22 (5), 451–456. https://doi.org/10.36849/JDD.7017 (2023).

Puig-Butille, J. A. et al. Capturing the biological impact of CDKN2A and MC1R genes as an early predisposing event in melanoma and Non melanoma skin cancer. Oncotarget 5 (6), 1439–1451. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.1444 (2014).

Qasim Gilani, S., Syed, T., Umair, M. & Marques, O. Skin cancer classification using deep spiking neural network. J. Digit. Imaging. 36 (3), 1137–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-023-00776-2 (2023).

Brancaccio, G. et al. Artificial intelligence in skin cancer diagnosis: A reality check. J. Invest. Dermatol. 144 (3), 492–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2023.10.004 (2024).

Borowska, S. & Brzóska, M. M. Metals in cosmetics: implications for human health. J. Appl. Toxicol. 35 (6), 551–572. https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.3129 (2015).

Wang, S. S., Lay, S., Yu, H. N. & Shen, S. R. Dietary guidelines for Chinese residents (2016): comments and comparisons. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 17 (9), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1600341 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lin Feng(Health Promotion Commission of Guangdong Province) and Chen Chun(Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention) for their guidance and assistance in epidemiological statistics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Z. and Y.L.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, validation, writing - original draft; C.D.: Resources, supervision, software, validation; G.L.: Conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing - review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was received from Ethics Committee of the First People’s Hospital of Kashgar (Reference No. [2023] Review No. (64)). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before study commencement.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, R., Lin, Y., Da, C. et al. Novel nomogram and decision curve analysis for predicting head and neck skin cancer risk. Sci Rep 15, 41555 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25427-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25427-0