Abstract

We present a novel multi-objective optimization algorithm, Archived Multi-Objective Simulated Annealing (AMOSA), based on simulated annealing for transient electromagnetic (TEM) one-dimensional inversion. The data misfit and model-constraint are treated as two objectives rather than being assembled into a single objective function in this method to reduce uncertainties. We obtain a set of satisfactory solutions rather than a single ‘global optimum’ with Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO). Archive and Pareto domination are used for discontinuous fronts and to determine the acceptance of a new model with Pareto-optimal solutions. Temperature based on the Quasi-Cauchy distribution instead of the Gibbs distribution is selected to accelerate the inversion and stabilize model perturbation. We test the method using several 1D layered-earth models with noise and noise-free data. All synthetic model inversion results are in good agreement with true models. Finally, we test the method using a coincident loop TEM field data. The inverted profile shows a reasonable three layers of subsurface geology. A nearby well water table verifies the interpreted aquifer layer and the estimated aquifer’s top surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an efficient geophysical exploration method, TEM method is widely used in mining exploration and monitoring1, metallic ore exploration2, and advanced detection of tunnels3. Inversion plays a crucial role in the interpretation of TEM data. Compared to imaging techniques, inversion can provide more accurate subsurface numerical information. Traditional gradient-based inversion methods operate by searching solely along the negative gradient direction of the objective function. This implies that such algorithms are only capable of descending toward lower fitting errors. However, for inverse problems that involve multiple local minima, an inappropriate initial model may lead these methods to converge to a local minimum. Consequently, their success is heavily reliant on the initial model. To circumvent this limitation, global optimization methods—such as Simulated Annealing (SA), Genetic Algorithms (GA), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)—have been developed. Among these methods, SA exhibits strong global search capabilities and demonstrates excellent adaptability to diverse problem types. The algorithm utilizes the criterion of statistical mechanics in finding globally optimal solutions associated with the lowest energy4. In the process of optimization, it applies the heuristic Metropolis principles5 to reduce the mobility of solutions with the system energy state decreases6. Since its introduction in optimization problems, SA has been applied successfully in many areas, such as traveling salesman problems4,7, integrated circuits designing problems8. As an outstanding nonlinear optimization algorithm, SA is also used in geophysical inversion problems, such as seismic data interpretation9, gravity inversion10, airborne electromagnetic data processing11, transient electromagnetic inversion12, controlled-source audio-frequency magnetotelluric6, and marine electromagnetic inversions13. Geophysical inverse problems are inherently ill-posed; without appropriate regularization, solutions often become non-unique and unstable. Even though simulated annealing is capable of escaping local minima, it does not always yield satisfactory inversion results because of its probabilistic nature and the high dimensionality and strong parameterization of geophysical models14. Regularization can help stabilize the inversion and mitigate these issues, but within the commonly used single-objective framework, it is difficult to determine appropriate weighting factors for regularization terms in advance15,16,17. Moreover, SA or its constrained variants still optimize a single objective function and therefore produce only one optimal solution, leaving the problems of non-uniqueness and instability unresolved.

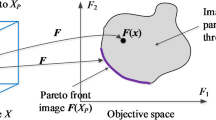

Under these circumstances, it is appropriate to use Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) to separate the model-fitting and model-constraint into two independent objective-functions in the optimization without choosing the weight between them. Unlike single-objective optimization that yields a singular global optimum, MOO generates a Pareto-optimal set—a collection of mutually non-dominated solutions forming the Pareto front (PO front) in objective space. These solutions correspond to different trade-offs between the objective functions; improving one objective typically degrades another, so each point on the Pareto front represents a different compromise between the competing goals. While this requires an additional step to analyze and interpret the resulting models, it also provides richer information about the range of acceptable solutions and the associated uncertainties. Over the past decade, studies on MOO problems mostly use the evolutionary algorithms (EAs) due to their population-based nature and ability to find multiple optima simultaneously18,19. In geophysics, for example, parallel multi-objective genetic algorithms (PMOGA) have been successfully applied to inversion problems by Akca (2013)20 and Bijani et al. (2017)21. However, there have been only a few attempts in extending SA to MOO primarily because of its search-from-a-point nature. Early studies on Multi-Objective SA (MOSA) were mostly aggregating approaches, which combine the different objectives into one using a weighted sum approach22,23,24. It is similar to constraint SA inversion, but selecting proper or adaptive weights during the annealing process to converge to the true PO front remains challenging even for MOO problems25,26. In addition, there are only very few techniques that incorporate the concept of Pareto-dominance for splitting sum objectives into multiple independent objective functions. Such as Suman (2005)27 and Smith et al. (2004)28 use Pareto-domination-based acceptance principle in MOSA. Suman & Kumar (2006) reviewed of several MOSA methods and their performance and suggested to consider constraints which may give promising results in term of saving in computation cost and quality of solution29. However, the acceptance criterion between current and a new state in MOSA is still only considered the difference in the number of solutions that they dominate as Pareto-domination-based MOSA developed so far.

In 2008, Bandyopadhyay et al. developed the Archived Multi-Objective Simulated Annealing (AMOSA) algorithm based on MOSA. This method incorporates the concept of an archive to provide a trade-off among the new solution, current solution, and archived solutions. The acceptance criterion follows the domination status of the new state with the current state, as well as solutions in the archive. The performance of AMOSA is generally superior to the other two well-known MOEA methods proposed before, which are Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-Ⅱ)30 and Pareto Archived Evolution Strategy (PAES)31, due to its ability to maintain a well-distributed Pareto front and its annealing-based search that helps avoid premature convergence. The main trade-offs of AMOSA are its higher computational cost and its sensitivity to annealing parameters compared with population-based methods. Nevertheless, its strength lies in effectively balancing exploration and exploitation, making it particularly robust for complex multi-objective problems where maintaining solution diversity is critical. As an advanced multi-objective optimization algorithm, AMOSA has been applied in many fields, such as computer science32,33, civil engineering34, and machine layout design35, but not reported in geophysical inversions.

In this paper, we develop the AMOSA algorithm for TEM inversion. We treat the data misfit and model structure as two separate objective functions to form a basic MOO. The results are archived as PO front instead of a single solution according to AMOSA characteristics. The non-uniqueness and instability can be significantly mitigated.

Methodology

Multi-objective function

To reduce the tendency toward overly smooth inversion results and to increase robustness to outliers, we use the L1 norm for the data misfit term (Eq. 1) rather than the conventional L2 norm, which emphasizes squared errors and can excessively smooth the recovered model.

where n is the total number of data, \(\:{d}_{real}\left(i\right)\) and \(\:{d}_{inv}\left(i\right)\) are the observed and predicted data, respectively, in the ith time gate, and \(\:{F}_{fitting}\) is the data misfit.

Model-constraint is another objective function in MOO. This term characterizes the model structure during inversion. Different model-constraint will have different influences on the solutions. Portniaguine & Zhdanov (1999; 2009)36,37summarized the expressions of some common model-constraints and their constraint effects on models. Following their work, we employ the focus measurement of model structure (Eq. 2) because it favors compact, high-contrast features and therefore helps to recover models with sharp boundaries.

where v represents the entire model domain in the inversion. m denotes the resistivity model to be recovered, and \(\:\nabla\:m\) represents its spatial gradient. β is a parameter that controls the intensity of focusing and is 0.4 in our study based on experiences, and \(\:{F}_{constraint}\) is the model constraint result. Due to the formulation of the focusing measure of model structure, its minimum value is a non-zero constant. This property enhances the ability of the constraint to emphasize compact, high-contrast features and to suppress overly smooth models. Although the residual value may complicate model updating and interpretation, it does not affect the performance of our algorithm and will be discussed in a later section.

Archived multi objective simulated annealing

AMOSA is an extension of SA. SA iteratively explores the model space through a temperature-controlled stochastic process. At each iteration, a new model is generated by perturbing the current model, and its acceptance probability is determined by the Metropolis criterion:

where \(\:\varDelta\:E\) is the energy difference between the new and current states, T is the temperature, and k is the Boltzmann constant. In this procedure, the lower energy state updating is bound to be accepted, while it has a probability of accepting higher energy state updates. That means SA has the ability to jump out of the local optimum and keep moving toward the global optimum until achieved. The standard simulated annealing algorithm escapes local optima by probabilistically accepting worse solutions according to the acceptance probability defined in Eq. (4). In our AMOSA implementation, we extend this criterion to incorporate Pareto dominance relationships that simultaneously consider the new solution, the current solution, and the archived non-dominated solutions. The complete set of acceptance probability calculations for all possible dominance scenarios between these three solution sets will be presented in subsequent Sect.

where E(current, T) and E(new, T) are energy states of the current and new model, respectively.

In AMOSA, we maintain an archive that stores all non-dominated solutions found at the time of their discovery. Once a solution has been stored in the archive, it is never removed, even if it later becomes dominated by subsequent solutions. We adopt an unlimited archive size to preserve the diversity of solutions throughout the inversion. Although this may increase the number of solutions stored, it does not hinder convergence because the acceptance probability is still governed by the dominance relationships and the cooling schedule. As the temperature decreases, the search gradually focuses near the Pareto-optimal front while the archive provides a rich set of candidate solutions. Of course, a limited archive size can also be used depending on computational requirements. Using a limited archive reduces memory and computational cost because the archive is pruned to retain only representative non-dominated solutions. However, this may sacrifice some solution diversity. In contrast, an unlimited archive retains all non-dominated solutions, which improves diversity at the cost of additional storage. In Fig. 1, we give a general structure and the pseudocode of the AMOSA inversion for TEM data.

Pseudocode of AMOSA algorithm for TEM inversion (after Bandyopadhyay et al., 2008). The algorithm initializes an archive of candidate models and iteratively perturbs the current model to generate new solutions. Each new model is evaluated based on dominance relationships with existing models in the archive and the current solution. Depending on its performance, the new model may replace the current model or update the archive using probabilistic acceptance rules. The process continues until a convergence criterion is met. Finally, all archive solutions are post-processed to determine the optimal model using a weighting function.

Archive initialization

The initialization can be a complicated process. Bandyopadhyay et al. (2008)38used a simple hill-climbing technique to obtain a set of non-dominated solutions, accepting a new solution only if it dominates the previous one. And they used a cluster analysis for reducing the number of solutions to the limited archive size. However, in our algorithm, the initialization is simplified to the random selection of 5 models in the model space since we adopt an unlimited archive.

Model perturbations: Quasi-Cauchy distribution based on temperature

To accelerate the inversion and stabilize the model perturbations, we use the Quasi-Cauchy algorithm to perturb models instead of Gibbs algorithm. As the temperature decreases in the Quasi-Cauchy scheme, the perturbations become more stable and less intense, which helps reduce the likelihood of skipping over promising regions of the search space. However, it should be noted that simulated annealing—and any stochastic global optimization algorithm—cannot guarantee convergence to the true global minimum. Although such approaches often find high-quality solutions, their performance depends on the complexity of the problem and the choice of initial models.

where \(\:{x}_{i}^{k+1}\) is the ith model parameter in the kth iteration, \(\:{x}_{i}^{max}\) and \(\:{x}_{i}^{min}\) are, respectively, the lower and upper limits of the \(\:{i}_{th}\) model parameter, \(\:{u}_{i}\) is a random number for the \(\:{i}_{th}\) parameter drawn from the uniform distribution in the range [0, 1]. Wang et al. (2012)6 provided an updated Eq. (5c) to replace (5b) in order to obtain efficient SA inversion results in controlled-source audio-frequency magnetotellurics (CSAMT).

We also use Eqs. (5a) and (5c) for model-perturbation in this paper.

Definition and amount of domination

The MOO problems can be considered as minimizing the vector composed of multi-objective functions, as shown in Eq. (6).

Domination is the central concept in MOO optimization. Suppose there are two solutions, a and b, the solution b dominates a if \(\:\forall\:i\in\:1,\:\cdots\:\cdots\:,\:D\), \(\:{f}_{i}\left(a\right)\le\:{f}_{i}\left(b\right)\) and \(\:\exists\:i\in\:1,\:\cdots\:\cdots\:,\:D\), such that \(\:{f}_{i}\left(a\right)<{f}_{i}\left(b\right)\), writing as a < b. Apparently, a non-dominates b means there is no such relationship between the two solutions. In the concept of dominance, the set of non-dominated solutions in the entire model space forms the globally PO front. We introduce the model fitting and model constraints as objective functions; hence the inversion process is

where \(\:{F}_{fitting}\left(x\right)\) and \(\:{F}_{constraint}\left(x\right)\) represent the data fitting function and the constraint objective function, respectively.

By introducing the dominance concept, the difference compared with conventional SA is the amount of domination, which is used in computing the acceptance probability of a new solution. For two given solutions—the current model and the new model, the amount of domination is defined as

where M is the number of objective functions (M = 2 in this study), \(\:{R}_{i}\) is the range of the ith objectives in the current iteration. The concept of \(\:\varDelta\:{dom}_{current,\:new}\) is illustrated intuitively in Fig. 2. \(\:\varDelta\:dom\) is used only in computing the acceptance probability of a new perturbed solution.

Diagram of the domination for the two objectives, model fitting and model constraint, respectively (after Bandyopadhyay et al., 2008). The two axes correspond to the constraint objective function and the data fitting function. The black dot represents the current model state. \(\:{R}_{fitting}\) and \(\:{R}_{constraint}\) are the changing range of model-fitting and model-constraint, respectively. Model update may generate one good or bad new model (as shown with hollow dots). If assuming \(\:\varDelta\:dom\) as the amount of domination between current and new state in computing the acceptance probability of a new solution, it can be easily calculated by the area division, one shaded rectangle area between the black dot and one hollow dot divides by the big rectangle area constructed by the \(\:{R}_{fitting}\) and \(\:{R}_{constraint}\).

Model updating

In the model perturbation and updating phase, we select one solution randomly from the archive as the initial model, i.e., the current model. After perturbing the current model, a new state is generated called new model. AMOSA also incorporates the property that can accept a worse solution which is inherited from the inversion process. Based on the dominance status among the new model, the current model, and the archived solutions, three different cases arise and are enumerated as follows.

Case 1: The current model dominates the new model

This means that the new model may be worse than the current model. In SA algorithm, such inferior states are still accepted with a certain probability to prevent the algorithm from getting trapped in a local minimum. Hence, the probability in AMOSA is calculated with Eq. (9) based on the amount of domination. The new model is then determined to be accepted as the current model by the calculated probability.

where k is solutions amount number dominating the new model in archive, t_0 is the temperature of the current iteration.

As k increasing, the new model is further away from the PO front. Because there will be more points dominating the new model. In addition, the temperature decreases as the inversion proceeds. And the acceptance probability becomes smaller to avoid jumping to a poor solution in later inversion steps.

Case 2: The current model and the new model are non-dominating to each other

In this case, the current model and the new model are non-dominating to each other. There are three situations based on the domination status between the new model and solutions in the Archive.

-

a)

The new model is dominated by k (k ≥ 1) members in the Archive. The acceptance probability of the new model is determined by the following equations:

In this situation, the current model may or may not be in the Archive.

-

b)

The new model is non-dominating with all models in the archive. It means the new model is also on the archival front, as well as current model. Therefore, the new model is added to the Archive and selected as the current model.

-

c)

k (k ≥ 1) points of the Archive are dominated by the new model. In this case, we update the current model with the new model and add the new model to the Archive. The k dominated models remain stored in the Archive but are flagged as dominated. The current model may or may not be on the PO front. However, the k dominated models are absolutely not on the PO front.

Case 3: The new model dominates the current model

Similar to Case 2, there are three situations based on the domination status between the new model and the archived solutions.

-

a)

The new model is dominated by k (k ≥ 1) models in the archive. This situation may occur only if the current model is not in the archive. Here, we compute the minimum of domination amounts between the new model and k dominated solutions, denoted as \(\:{\varDelta\:dom}_{min}\). Then we accept the model in the Archive corresponding to \(\:{\varDelta\:dom}_{min}\) as the current model with a probability as follows.

Otherwise, the new model is accepted as the current model. Actually, in traditional SA, the new model is accepted 100% in this situation. However, due to the use of archive in AMOSA, there exist better solutions than the new model. Thus, we do not accept it directly but make a competition for acceptance between the new model and the closest dominating points in the Archive (corresponding to \(\:{\varDelta\:dom}_{min}\)). This is a reseeding process in the current iteration if the Archive point is accepted.

-

b)

The new model is non-dominating with all archived solutions. The new model is on the archival front in this situation. Thus, the new model is added to the archive and accept as the current model. The current model will be updated if it is already in the archive.

-

c)

The new model dominates k (k ≥ 1) other models in the archive. We accept the new model as current model and replace all dominated points in the archive. And, the current model maybe on or not on the archival front in this situation.

The above process may repeat for 20 times at a given temperature. The temperature of current iteration is α times that of the last iteration according to the hyperbolic cooling schemes\(\:\:T={T}_{0}{\alpha\:}^{n}\), and α is selected as 0.93 in this paper based on experience. A smaller α means a faster cooling. However, we may not obtain good inversion results if α is too small.

De-duplicate the archive and output the result

As a result of the operations above, the archive contains many duplicate points, which affect the probability of random model selection in the next iteration. The models with more repetitions will have a higher probability of being selected. This is unfair and incorrect to the total inversion. In this study, we de-duplicate the archive and record the repetition times of each solution after every iteration. These repetition counts are then used only when computing the averaged model, so that solutions with more repetitions contribute more to the averaged model, while the selection probabilities remain fair.

Theoretically, all solutions in the archive are good enough to meet our requirements after inversion. However, not all models are equally satisfactory, since the model-constraint objective function rarely converges to zero. Nevertheless, the diversity of solutions stored on the Pareto front and in the archive allows us to select several models that still meet the requirements even under these circumstances. In addition, although multi-objective optimization produces a set of trade-off solutions, in practical geophysical applications a single representative model is usually required for subsequent geological interpretation and decision-making. Therefore, it is necessary to select one final model from the Pareto-optimal set. In this study, choosing a good result from the Archive is a key issue. In noise-free synthetic tests, the value of this objective can ideally reach zero, whereas in real or noisy data applications, the minimum value will be greater than zero. Although other objectives, such as regularization, play an important role during the inversion process to stabilize the search and ensure geologically reasonable models, the final output stage gives priority to the data-fitting objective. Specifically, we rank the models on the Pareto front by their data misfit and select the three with the smallest misfit values. Instead of presenting only a single model, we take the average of these three models as a representative solution (Eq. 12) in order to reduce non-uniqueness and produce a more stable result.

This does not mean the constraint may not have effects in inversion: during the multi-objective inversion, the model-constraint objectives shape the search space. If the inversion were driven by the data misfit alone, the search would behave like a random walk, require much more computation time, and would be unlikely to converge to a geologically meaningful model within a reasonable time.

This kind of operation represents a compromise strategy. When a very strong smoothing constraint is applied, the value of the constraint objective function can approach zero because the model becomes nearly flat. However, such excessive smoothing will blur important geological structures. Therefore, an important topic for future research is to develop constraint terms that can preserve structural details while providing stability, so that the inversion produces geologically realistic results without relying too much on manual parameter tuning.

In summary, the above describes the complete workflow of the AMOSA algorithm. The flowchart of the AMOSA algorithm is shown in Fig. 3.

Flowchart of the AMOSA algorithm for 1-D TEM inversion. The process starts from reading the observed TEM data, followed by the initialization of temperature, definition of objective functions (model fitting and model-constraint), generation of initial models, and archive initialization. Perturbation sampling based on the temperature-dependent Quasi-Cauchy distribution is used to produce new models. For each new model, 1-D TEM forward modeling is performed and both objectives are evaluated. The dominance relationship between the new and current models determines the acceptance strategy: deterministic acceptance when the new model dominates, probabilistic acceptance when dominated, and conditional acceptance when non-dominated but dominating at least one archived model. The archive is updated accordingly. Iterations continue with temperature reduction until the fitting error is below a predefined threshold. The final inversion result is obtained by averaging the top three Pareto-optimal models with the smallest data misfit.

Synthetic examples

To test and verify the effectiveness of AMOSA in TEM inversion, we selected two three-layered models and a five-layered model as a numerical test. As listed in Table 1, Model #1 consists of three layers with a conductive layer in the middle, while Model #2 has three layers with a resistive layer in the middle. Model #3 is a five-layered model with two conductive layers inside. The inversion parameters in our study include both the resistivities and the layer thicknesses. The parameters used in the AMOSA inversion test are also given in Table 1, including the resistivity constraints and the initial temperature in SA. Prompted by Occam’s multi-layer inversion, we discretize the model into eight horizontal layers. The thickness of each of the first seven layers is set as an inversion parameter with allowed variation between 20 and 40 m, while the eighth layer represents a half-infinite bottom layer. To ensure consistency, we use the same parameter ranges and initial temperature for all inversion cases. Although the number of layers is fixed as a discretization choice, this constitutes a minimal prior assumption. Both resistivity and thickness parameters are inverted within predefined bounds to simulate limited prior information. In our implementation, one “iteration” corresponds to an outer loop at a given annealing temperature, and within each iteration we perform 20 random perturbations (“steps”) of the model parameters. After completing all steps at a given temperature, the temperature is updated according to the cooling schedule.The program automatically terminates when the data misfit drops below the predefined threshold of ε = 0.01, without requiring a manually set number of iterations. In the Archive initialization, 5 initial models are randomly generated. We use a 200 × 200 m square transmitter loop with a central receiver and 1 A transmitting current.

The AMOSA inversion result for Model #1 is shown in Fig. 4. The inversion pushes the PO front towards the optimal directions of the two objective functions. In Fig. 4b, the solid black dots represent the final non-dominated solutions, namely the current Pareto front, obtained in the last iteration, while the hollow dots correspond to archived solutions that were previously on the Pareto front but have since been dominated by newer solutions. The current Pareto front solutions dominate these older archived ones. Although all the non-dominated solutions on the Pareto front are theoretically optimal in terms of the objective functions, not all of them are equally plausible in real geophysical applications. Some solutions, while mathematically optimal, may correspond to unrealistic or geologically implausible resistivity structures. Therefore, in practical interpretation, additional criteria such as smoothness or prior geological knowledge are often required to select the most reasonable solution from the Pareto front.

(a) Inversion result and (b) the distribution of Archived points’ set for Model #1, a three-layered model with low resistivity in the middle. The model and inversion parameters are listed in Table 1. In (b), the solid dots correspond to the In-PO front while the hollow dots are the Non-PO front but once archived. In (a), the dot line is the average inversion result of three best solutions with minimum model fitting errors on the PO front. The inverted result shows good agreement with the true model in solid line, including the resistivity value and the layer position.

As shown in Fig. 4b, we select the three solutions closest to the vertical axis, which correspond to the smallest model fitting errors among the Pareto-optimal solutions. Although some solutions further away on the front exhibit higher model smoothness, indicating stronger regularization, they provide poorer data fit and are therefore not selected for interpretation. This uneven distribution of solutions along the Pareto front is partly due to the stochastic nature of AMOSA and its tendency to converge toward better-fitting models. However, since all archived solutions are preserved, we retain a diverse set of models that can be further examined using additional geological or geophysical constraints. This helps mitigate the non-uniqueness and instability commonly observed in single-objective SA inversion.

To quantitatively evaluate the accuracy of the inversion results, we adopt the Average Weighted Error (AWE) as the metric, which is defined as:

where denotes the number of layers in the inversion model, \(\:{{\uprho\:}}_{i}^{inv}\) and \(\:{{\uprho\:}}_{i}^{true}\)are the inverted and true resistivities of the th layer respectively, and wi is the thickness of the th layer. To ensure accurate layer-by-layer correspondence, the true resistivity model is discretized into the same number of layers as the inversion model. Specifically, for each inversion layer, the midpoint depth is mapped into the true model, and the true resistivity is obtained by thickness-weighted averaging over the overlapping region. This approach guarantees spatial consistency between the inversion and true models, thereby ensuring the rationality and scientific validity of the error calculation. The computed AWE is 6.02%, indicating a low average relative error between the inversion results and the true model, which demonstrates the high accuracy of the AMOSA algorithm.

To test the stability of the AMOSA, we take three runs for Model #1, with the results shown results in Fig. 4a. The computed Average Weighted Errors (AWE) for these runs are approximately 7.06%, 19.28%, and 11.73%, respectively. While the second run exhibits a somewhat higher error, all three inversion results generally demonstrate reasonable consistency with the true model. All three inversion solutions demonstrate decent consistency with the true model. And the archived solutions for each run are shown in Fig. 5b and c, and 4d. While these results show minor variations compared to those in Fig. 3a, such discrepancies are expected given the fundamentally stochastic nature of the AMOSA. As a probabilistic optimization method, AMOSA inherently produces slightly different solutions in each inversion, a characteristic that is clearly manifested in the distinct distributions of archive members across the three realizations.

AMOSA inversion stability test results for Model-1. Model and inversion parameters are listed in Table 1. (a) displays the inverted results in three runs and the true model. (b), (c), and (d) demonstrate the distribution of all archived points in the inversion of the three runs, respectively. The solid dots correspond to the In-PO front while the hollow dots are the Non-PO front which once archived. The inverted results with three runs are all in good agreement with the true model in the solid line.

Figure 6 presents the inversion results for Model #2, demonstrating that AMOSA remains effective even for resistive target layers. As shown in Fig. 6a, the inverted model exhibits excellent agreement with the true model. The PO front is listed in Fig. 6b. The AWE is approximately 4.78%, quantitatively confirming the accuracy of the inversion.

For further validation, we apply the method to Model #3, a more complex five-layer model containing two embedded conductive layers. The results of the model tests are given in Fig. 7. While the inversion successfully captures the essential characteristics of the true model, some discrepancies emerge in the deeper layers, which may be attributed to the decreasing sensitivity of surface measurements with depth. These results collectively demonstrate the robustness of our approach across different geological scenarios.

For relatively simple geological scenarios (Models #1 and #2), where parameter variations are moderate, AMOSA demonstrates robust inversion capability, consistently producing solutions with excellent data fits. Model #3 presents greater complexity due to its increased parameter variations. While transient electromagnetic (TEM) methods exhibit strong sensitivity to low-resistivity anomalies, their resolution decreases significantly at later time gates corresponding to greater depths. Nevertheless, through careful analysis of the PO front characteristics, we can extract geologically meaningful solutions even for these more challenging cases.

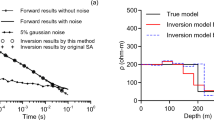

After that, we re-invert Model #1 with 5% Gaussian noise added to the data. We use the Gaussian normal distribution method36 to add noise to the simulated data. The inversion results are shown in Fig. 8. After adding Gaussian noise, the AWE increases to approximately 19.0%, indicating that noise has a certain impact on the inversion accuracy. However, the overall data fitting precision remains within an acceptable range. Compared with the noise-free inversion, the model exhibits more pronounced variations near the layer interfaces, reflecting the inherent uncertainty introduced by noise. However, since our method employs a multi-objective framework balancing data misfit and model constraint, the inversion process is more robust to noise. The model constraint acts as a regularization that prevents overfitting noisy data, thus maintaining model stability and geological plausibility. Consequently, despite the presence of noise, AMOSA produces consistent and geologically reasonable models, which is essential for practical applications where data noise is inevitable. Selecting high signal-to-noise ratio data further enhances inversion reliability.

(a) Inversion result and (b) the distribution of archived points’ set for Model #2, a three-layered model with high resistivity in the middle. Model details and inversion parameters are listed in Table 1. In (b), the solid dots correspond to the PO front while the hollow dots are Non-PO front but once archived. In (a), the dot line is the average inversion result of three best solutions with minimum model-fitting errors in PO front. The inverted result is in good agreement with the true model in solid line.

(a) Inversion result and (b) the distribution of archived points’ set for Model #3, a five-layered model with two low resistivity layers in the middle. Model details and inversion parameters are listed in Table 1. In (b), the solid dots correspond to the PO front while the hollow dots are Non-PO front but once archived. In (a), the dot line is the average inversion result of three best solutions with minimum model-fitting errors on PO front. The inverted result is in good agreement with the true model in solid line. The inversion is a little bit bad than that of Model #1 and Model #2 due to the complexity of model design. Both two low resistivity layers are demonstrated in the inversion result.

AMOSA test with noise data for Model-1, a three-layered model with low resistivity in the middle. (a) inversion result, (b) the distribution of Archived points’ set in the inversion progress, and (c) curves of TEM data with or without noise and 5% Gaussian noise data used. The model and inversion parameters are listed in Table 1. In (b), the solid dots correspond to the PO front while the hollow dots are Non-PO front but once archived. In (a), the inversion result with or without noise is the average inversion result of three best solutions with minimum model fitting errors on PO front. The inverted results are in good agreement with the true model in solid line as well, even with noisy data. Also in (c), the decay data of inversion result with noise fits well with the real model data.

Field data example

While synthetic examples are valuable for controlled evaluation, applying AMOSA to TEM field data provides an opportunity to assess its practical applicability under real-world noise, survey geometry, and subsurface complexity that cannot be fully replicated synthetically. We take the TEM survey in a farm near Mencun Village, Pingdu, Qingdao, China, as location is shown in Fig. 9. The used survey line has 16 stations and the station spacing is 2.5 m. There is a pump well with a diameter of ~ 1 m at about 9 m away from the 1st observation point. The water table is about 15 m from the surface with a tape measurement. This well is for irrigating farmland. We use a coincident loop configuration, and the transmitter has a transmitting area of 100m2. The motivation of the survey is to detect underground aquifer. We use AMOSA to do the inversion. We first discretize the underground using 8 horizontal layers and each layer has a resistivity constraint from 10 to 500 ohm-m. The thickness of each layer is set to in the range from 20 to 40 m and the initial temperature is set to10. In order to completely perturb the model space, we run about 1500 iterations with 20 random steps in each iteration, and 5 initial models are randomly selected in the Archive initialization procedure.

The AMOSA 1D inversion results (Fig. 10a) reveal a three-layer resistivity structure, with the corresponding geological interpretation shown in Fig. 10b. The middle layer is conductive, with resistivity ranging from 30 to 100 ohm·m, while the upper and lower layers have resistivity values exceeding 300 ohm·m. Based on these results, we interpret the subsurface geology as consisting of Quaternary overburden in the upper layer, a ~ 40 m thick aquifer in the middle layer, and bedrock in the lower layer. The interpreted top of the middle aquifer, when projected towards the known well location, coincides with the measured water table depth of approximately 15 m. Although direct verification through drilling or resistivity logging was not available, this agreement, together with the consistency of the recovered resistivity structure with the known regional hydrogeological framework, provides strong indirect support for the plausibility of our interpretation. This demonstrates the practical applicability of AMOSA to real TEM field data under realistic survey constraints.

The field site location is close to Mencun, a small village in Qingdao, Shandong Province, China. The survey line is on farmland with a pumping well nearby. The well diameter is about 1 m and we can see the water surface. The water table in the well is about 15 m from the wellhead, with a tape measure. The pump well is about 9 m from the survey line start point. A total of 16 sites was measured on the survey line with an interval of 2.5 m to obtain the subsurface geological distribution. Since the survey area is all flat ground without any buildings or roads, the signal-to-noise ratio of acquired data is pretty good.

AMOSA inversion resistivity profile (a) for the acquired TEM field data and the estimation of underground geological strata and aquifer distribution (b). The pumping well is also located in the figure demonstrating the water table. The middle aquifer layer surface is estimated to the well with the dashed line and fits well with the pumping well water table.

Conclusions and discussions

We extend the classical SA into a multi-objective optimization framework by implementing the AMOSA algorithm for 1D TEM inversion. By substituting the Gibbs distribution in SA perturbations with the temperature-dependent Quasi-Cauchy distribution, AMOSA better accommodates the specific inversion characteristics of TEM data. Unlike traditional single-objective optimization methods, AMOSA produces a diverse set of Pareto-optimal solutions, effectively addressing the intrinsic non-uniqueness and instability of TEM inversion. The final solution set obtained in the last iteration resides on the Pareto front, yet not all solutions fully satisfy practical requirements due to excessive model constraints in certain archived points, which leads to variability among inversion results. Our experiments on both synthetic and field TEM datasets demonstrate that AMOSA achieves stable and reliable inversion outcomes, indicating promising potential for practical applications.

This method is based on several key assumptions: (1) the subsurface is modeled as a horizontally layered 1D structure, which limits accuracy in the presence of pronounced 2D or 3D geological heterogeneities; (2) observational noise is moderate and approximately uniform—higher levels or structured noise can broaden the Pareto front and reduce inversion reliability; (3) the focusing constraint parameter is fixed, and inappropriate values may bias the balance between resolution and stability; (4) the Archive size is not explicitly constrained, which enhances solution diversity but increases computational cost for large datasets. Each assumption inherently restricts the method’s applicability under certain conditions. In this study, the selection of optimal solutions is based on identifying the three solutions with the lowest data misfit within the Pareto front. This criterion may be affected by noisy data, necessitating future work to develop more robust selection standards under noisy conditions. Furthermore, potential improvements include incorporating noise-robust objective functions, adopting adaptive weighting strategies for model constraints, and applying clustering techniques to maintain a balanced Archive. These represent important directions for our ongoing research.

Theoretically, our work confirms that AMOSA can be effectively adapted to 1D inversion problems even when objective functions depend on the model, overcoming limitations common to traditional Pareto-based approaches. Practically, it is particularly well-suited for TEM surveys in resource exploration and environmental monitoring, especially where non-uniqueness is prominent and preservation of geological boundaries is critical. However, caution is advised when applying this method in environments characterized by strong 2D/3D effects or high noise levels, as these conditions may impair inversion accuracy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due confidential but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xue, G. Q., Cheng, J. L., Zhou, N. N., Chen, W. Y. & Li, H. Detection and monitoring of water-filled voids using transient electromagnetic method; a case study in Shanxi, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 70 (5), 2263–2270 (2013).

Swidinsky, A., Holz, S. & Jegen, M. On mapping seafloor mineral deposits with central loop transient electromagnetics. Geophysics 77 (3), E171–E184 (2012).

Li, S. C., Sun, H. F., Lu, X. S. & Li, X. Three-dimensional modeling of transient electromagnetic responses of water-bearing structures in front of a tunnel face. J. Environ. Eng. Geophys. 19 (1), 13–32 (2014).

Kirkpatrick, S., Gelatt, J. R. C. D. & Vecchi, M. P. Optim. Simulated Annealing Science 220,671–680 (1983).

Metropolis, N., Rosenbluth, A. W., Rosenbluth, M. N., Teller, A. H. & Teller, E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21 (6), 1087–1092 (1953).

Wang, R., Yin, C. C., Wang, M. Y. & Wang, G. J. Simulated annealing for controlled-source audio-frequency magnetotelluric data inversion. Geophysics 77 (2), E127–E133 (2012).

Kirkpatrick, S. Optimization by simulated annealing: quantitative studies. J. Stat. Phys. 34 (5–6), 975–986 (1984).

Otten, R. &van Ginneken, L. The Annealing Algorithm (Kluwer Academic, 1989).

Ryden, N. & Park, C. B. Fast simulated annealing inversion of surface waves on pavement using phase velocity spectra. Geophysics 71 (4), R49–R58 (2006).

YU, P., Wu, W. A. N. G. J. L., Wang, D. W. & J. S. & Constrained joint inversion of gravity and seismic data using the simulated annealing algorithm. Chin. J. Geophysics-Chinese Ed. 50, 529–538 (2007).

Yin, C. C. & Hodges, G. Simulated annealing for airborne EM inversion. Geophysics 72 (4), F189–F195 (2007).

Sharma, S. P. & Kaikkonen, P. Global nonlinear inversion of transient EM data from conducting surroundings using a free-space plate model. Geophysics 65 (3), 783–790 (2000).

Roth, F. & Zach, J. J. Inversion of marine CSEM data using up-down wavefield separation and simulated annealing.

Thyer, M., Kuczera, G. & Bates, B. C. Probabilistic optimization for conceptual rainfall-runoff models; a comparison of the shuffled complex evolution and simulated annealing algorithms. Water Resour. Res. 35 (3), 767–773 (1999).

Hu, Z. Z. et al. MT parallel simulated annealing constrained inversion and its application. Shiyou Diqiu Wuli Kantan. 45 (4), 597–601 (2010).

Zhang, P., Yu, X., Xu, Y., Lv, R. & Lu, C. An adaptive regularized inversion of 1D Semi-Airborne Time-Domain electromagnetic data. Comput. Techniques Geophys. Geochemical Explor. 39, 1–8 (2017).

Netto, A. & Dunbar, J. 3-D constrained inversion of gravimetric data to map the tectonic terranes of southeastern Laurentia using simulated annealing. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 513, 12–19 (2019).

Deb, K. Multi-objective optimization using evolutionary algorithms. (2001).

Coello, C. A. C., Lamont, G. B. & Van Veldhuizen, D. A. Evolutionary algorithms for solving multi-objective problems. (2002).

Akca, İ. et al. Joint parameter Estimation from magnetic resonance and vertical electric soundings using a multi-objective genetic algorithm. Geophys. Prospect. 62 (2), 364–376 (2014).

Bijani, R. et al. Physical-property-, lithology- and surface-geometry-based joint inversion using Pareto multi-objective global optimization. Geophys. J. Int. 209 (2), 730–748 (2017).

Czyzżak, P. & Jaszkiewicz, A. Pareto simulated annealing-a metaheuristic technique for multiple-objective combinatorial optimization. J. multi-criteria Decis. Anal. 7 (1), 34–47 (1998).

Suppapitnarm, A., Clarkson, P. J. & Seffen, K. A., Parks, G. T. & A simulated annealing algorithm for multiobjective optimization. Eng. Optim. 33 (1), 59–85 (2000).

Nam, D. & Park, C. H. Multiobjective simulated annealing: A comparative study to evolutionary algorithms. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2, 87–97 (2000).

Das, I. & Dennis, J. E. A closer look at drawbacks of minimizing weighted sums of objectives for Pareto set generation in multicriteria optimization problems. Struct. Optim. 14 (1), 63–69 (1997).

Jaszkiewicz, A. Comparison of local Search-Based metaheuristics on the multiple objective knapsack problem. Found. Comput. Decis. Sci. 26, 99–120 (2001).

Suman, B. Study of self-stopping PDMOSA and performance measure in multiobjective optimization. Comput. Chem. Eng. 29 (5), 1131–1147 (2005).

Smith, K. I., Everson, R. M. & Fieldsend, J. E. Dominance measures for multi-objective simulated annealing.

Suma, B. & Kumar, P. A survey of simulated annealing as a tool for single and multiobjective optimization. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 57 (10), 1143–1160 (2006).

Deb, K., Pratap, A., Agarwal, S. & Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 6, 182–197 (2002).

Knowles, J. D. & Corne, D. W. Approximating the nondominated front using the Pareto archived evolution strategy. Evol. Comput. 8 (2), 149–172 (2000).

Bandyopadhyay, S. Multiobjective simulated annealing for fuzzy clustering with stability and validity. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybernetics Part. C (Applications Reviews. 41 (5), 682–691 (2011).

Saha, S., Ekbal, A., Alok, A. K. & Spandana, R. Feature selection and semi-supervised clustering using multiobjective optimization.Springerplus 3 465 (2014).

Zewdie, M. & Bhallamudi, S. M. Multi-objective management model for waste-load allocation in a tidal river using archive multi-objective simulated annealing algorithm. Civil Eng. Environ. Syst. 29 (4), 222–230 (2012).

Haddou, B. H. & Benyoucef, L. Machine layout design problem under product family evolution in reconfigurable manufacturing environment: a two-phase-based AMOSA approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 104 (1–4), 375–389 (2019).

Portniaguine, O. & Zhdanov, M. S. Focusing Geophys. Inversion Images Geophysics 64(3),874–887 (1999).

Zhdanov, M. S. Geophysical Electromagnetic Theory and Methods (Elsevier Science, 2009).

Bandyopadhyay, S., Saha, S., Maulik, U. & Deb, K. A simulated Annealing-Based multiobjective optimization algorithm: AMOSA. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 12, 269–283 (2008).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42374176), the Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2025RS-CXTD-005) and the Special Support Program for Sanqin Talents of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2025SQTD-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Formal analysis, Qiang Liu and Guihong Li; Methodology, Hao Wang, Zaibin Liu and Zhao Zhao; Visualization, Bo Li; Writing – original draft, Youxin An, Tao Fan and Ping Li.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

An, Y., Fan, T., Li, P. et al. Archived multi-objective simulated annealing transient electromagnetic inversion. Sci Rep 15, 41769 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25699-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25699-6