Abstract

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an effective treatment for early gastric cancer (EGC), but submucosal fibrosis remains a major obstacle to successful resection. This study aimed to identify risk factors and construct a clinically applicable nomogram for predicting submucosal fibrosis in EGC, and to evaluate its impact on ESD outcomes. We retrospectively analyzed 264 lesions from 251 patients who underwent ESD between January 2012 and December 2024. Patients were randomly assigned to a training cohort (n = 184) and a validation cohort (n = 80) in a 7:3 ratio. A nomogram was constructed using multivariate logistic regression. Model performance was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), calibration curves, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and decision curve analysis (DCA). Histologic assessment of the submucosal fibrosis was performed using Masson’s trichrome staining. Independent predictors of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis included tumor size greater than 30 mm (OR 4.041, 95% CI 1.412 ~ 11.560, P = 0.009), depressed-type tumor (OR 3.713, 95% CI 1.613 ~ 8.546, P = 0.002), submucosal invasion (OR 4.804, 95% CI 1.369 ~ 16.858, P = 0.014) and tumor location in the middle (OR 11.630, 95% CI 4.243 ~ 31.879, P < 0.001) and upper third (OR 9.967, 95% CI 3.589 ~ 27.685, P < 0.001) of the stomach. The nomogram yielded an AUC of 0.880 (95% CI 0.828 ~ 0.932) in the training cohort and 0.864 (95% CI 0.786 ~ 0.941) in the validation cohort. The calibration curve showed excellent consistency between the nomogram predictions and actual observations. DCA showed a positive net benefit for the nomogram. Increased fibrosis severity was associated with lower en bloc and curative resection rates, higher rates of bleeding and perforation, and prolonged procedure time. Concordance between endoscopic and histologic fibrosis grading was high (Cohen’s κ = 0.857, P < 0.001). We developed a robust and interpretable nomogram for the preoperative prediction of submucosal fibrosis in EGC. This tool can aid endoscopists in risk stratification, operator selection, and complication avoidance during ESD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide1. Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as a gastric carcinoma limited to the gastric mucosa or submucosa regardless of lymph node metastasis2. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) provides a good long-term outcome, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 97.5%, lower morbidity, and an improved quality of life than surgical treatment3,4. The long-term survival of patients who undergo curative ESD is comparable to those who undergo surgery5. Furthermore, ESD prior to surgery for gastric cancer with submucosal invasion did not adversely affect clinical outcomes after additional surgery6. Consequently, ESD is now considered as a standard treatment for EGC in many guidelines and the use of gastric ESD is increasing in popularity worldwide7.

Despite its clinical efficacy, ESD remains technically demanding. Its success is influenced not only by operator experience and instrumentation, but also by tumor-specific characteristics such as submucosal fibrosis8,9,10. Submucosal fibrosis hinders submucosal lifting, prolongs dissection, increases the risk of incomplete resection, and elevates complication rates, including bleeding and perforation. Lesions with fibrosis often require advanced skills and strategies, making preoperative identification critical.

However, there is a lack of validated tools for the preprocedural prediction of submucosal fibrosis in EGC. Existing literature has described associated risk factors, but these findings have not been synthesized into an integrated, clinically actionable model. Furthermore, the correlation between endoscopic and histologic assessments of submucosal fibrosis remains incompletely characterized, limiting intraoperative decision-making.

To address these gaps, we conducted a retrospective study with four objectives:

-

(1)

To identify clinical predictors of submucosal fibrosis in EGC;

-

(2)

To develop and validate a nomogram-based predictive model for submucosal fibrosis;

-

(3)

To evaluate the relationship between ESD outcomes and the degree of submucosal fibrosis in EGC;

-

(4)

To assess the concordance between endoscopic and histologic fibrosis grading.

Results

Data normality

Data normality was assessed utilizing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. P values for all variables in the study groups were < 0.05, indicating a non-normal distribution. Consequently, nonparametric tests were used for subsequent analyses.

Baseline characteristics of patients

A total of 251 patients with 264 EGC lesions were enrolled, of whom 162 (61.36%) were male. The median age of the patients was 62.00 years (interquartile range (IQR): 56.00 ~ 68.00). Among the 264 EGC lesions, the distribution of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis was as follows: 170 (64.39%) with F0, 58 (21.97%) with F1, 36 (13.64%) with F2. The lesions were randomly divided into 184 EGC lesions in the training cohort and 80 EGC lesions in the validation cohort in a ratio of 7:3. The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1, and no significant differences in demographic and clinicopathological characteristics or ESD outcomes were found between the training cohort and validation cohort, indicating that the data of the training cohort and validation cohort were comparable. All patients with complications recovered with endoscopic intervention, without surgical intervention. No procedure-related deaths occurred.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

Factors associated with endoscopic submucosal fibrosis in the training cohort are presented in Table 2. Univariate analysis revealed that tumor location (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001), differentiation (P = 0.034), depth of invasion (P < 0.001) and macroscopic type (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with endoscopic submucosal fibrosis in the training cohort (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, tumor size greater than 30 mm (OR = 4.041, 95%CI: 1.412 ~ 11.560, P = 0.009), depressed-type tumor (OR = 3.713, 95%CI: 1.613 ~ 8.546, P = 0.002), submucosal invasion (OR = 4.804, 95%CI: 1.369 ~ 16.858, P = 0.014) and tumor location in the middle (OR = 11.630, 95%CI: 4.243 ~ 31.879, P < 0.001) and upper third (OR = 9.967, 95%CI: 3.589 ~ 27.685, P < 0.001) of the stomach independently predicted endoscopic submucosal fibrosis (Table 4).

Development of nomogram for predicting endoscopic submucosal fibrosis

A nomogram was developed based on the results of the multivariate analysis (Fig. 1). The nomogram incorporated independent risk factors, including tumor size greater than 30 mm, depressed-type tumor, submucosal invasion, and tumor location in the middle and upper third of the stomach. Each factor was assigned a score, and the sum of these scores corresponded to a total score that reflected the predicted probability of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis.

The ROC curves were plotted to evaluate the predictive performance of the model, and the AUCs for the nomogram were 0.880 (95%CI: 0.828 ~ 0.932) in the training cohort (Fig. 2A) and 0.864 (95%CI: 0.786 ~ 0.941) in the validation cohort (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that the model has excellent predictive capability.

The calibration curves of the training cohort (Fig. 3A) and validation cohort (Fig. 3B) demonstrated excellent agreement between the observed and predicted values, with the P value for the H-L test of 0.113 (χ2 = 8.904) and 0.681 (χ2 = 0.770), respectively. Furthermore, the DCA curves of the training cohort (Fig. 4A) and validation cohort (Fig. 4B) showed good clinical utility, suggesting a positive net benefit.

ESD outcomes according to the degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis

ESD outcomes according to the degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis are shown in Table 5. The en bloc resection rate in the F2 group was significantly lower than in either the F1 group or the F0 group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A). As the endoscopic submucosal fibrosis became more severe, the curative resection rate decreased (P ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 5B), but the required procedure time increased (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5C). The immediate bleeding rate was significantly higher in the F2 group and the F1 group than in the F0 group (P < 0.001; P = 0.013) (Fig. 5D). Additionally, the perforation rates were significantly higher in the F2 group than in either the F1 group or the F0 group (P = 0.019; P = 0.001) (Fig. 5E). On the other hand, delayed bleeding was not related to the degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis (P = 0.296).

Agreement between endoscopic and histologic submucosal fibrosis

The results of a comparison between endoscopic and histologic classifications of submucosal fibrosis are summarized in Table 6. A total of 93.53% (159/170) of F0 cases showed no staining histologically (f0); 84.48% (49/58) of F1 cases showed mild staining histologically (f1); and 100% (36/36) of F2 cases showed severe staining histologically (f2). Overall percent agreement was 92.42% (244/264). There was a high degree of concordance (Cohen’s κ = 0.857, P < 0.001), which suggests that endoscopic assessment of submucosal fibrosis is an effective measure of submucosal fibrosis.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated submucosal fibrosis, one of the important indicators for the application of gastric ESD. Our research identified that several endoscopic findings including tumor size greater than 30 mm, location in the upper and middle thirds of the stomach, submucosal invasion and a depressed-type tumor were associated with a high risk of submucosal fibrosis in EGC. These findings indicate that technical difficulty may be encountered during ESD for such lesions. In addition, we created a predictive model comprising these factors. The advantage of this nomogram model is to convert the complex regression equation into a visual graph, which is more intuitive and operable, and easy to be applied in clinical practice. The model showed highly accurate prediction. This tool may support risk stratification, operator selection, and procedural planning for patients at high risk of submucosal fibrosis.

Tumor macroscopic type

We found that depressed-type tumors were more strongly associated with submucosal fibrosis than non-depressed lesions. Depressed-type tumors—particularly ulcerated lesions— can stimulate submucosal collagen deposition, and ongoing exposure to gastric secretions promotes intense inflammation, leading to submucosal adhesion and fibrosis; accordingly, submucosal adhesion or fibrosis is commonly encountered during ESD in ulcerated lesions11. Ohnita et al.12 reported that ulceration is a key factor contributing to incomplete resection of EGC during ESD. Moreover, previous studies13,14 have showed that ulceration significantly prolongs procedure time and increases the risk of perforation.

Tumor location

Tumor location in the upper or middle thirds of the stomach was identified as an independent predictor of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis in this study, consistent with previous studies10,15,16. The higher prevalence of submucosal fibrosis in these regions may be related to structural differences within the stomach. Medial and longitudinal oblique muscle fibers run along the inner aspect of the anterior and posterior gastric body, and perforating branches from these fibers form a distinctive submucosal vascular network. In addition, fibrosis can form a fascial-like sheath around the transverse neural plexuses9. Another potential explanation is that submucosal-invasive EGCs are more commonly observed in the upper and middle thirds, where the gastric wall—particularly the submucosa—is thinner, making lesions more prone to infiltration and subsequent fibrosis16. Moreover, in the cardia, reflux-related chronic injury and inflammation can promote submucosal collagen deposition and fibrosis. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms require further elucidation.

Tumor size and submucosal invasion

Tumor size greater than 30 mm and the submucosal invasion were identified as independent predictors of submucosal fibrosis, corroborating previous findings9,10,17. Fibrosis is believed to arise from inflammation, tumor invasion, and the mass effect of the tumor18,19. As the tumor grows or invades the submucosa, fibrosis, referred to as “desmoplasia,” may develop around the tumor, potentially exacerbating the accompanying fibrosis. Therefore, it is crucial to assess the tumor size and depth of invasion for EGC by white-light endoscopy, magnifying endoscopy with NBI, chromoscopy, and EUS before ESD20.

Evaluate the agreement between endoscopic and histologic submucosal fibrosis

At present, few studies have constructed predictive models of submucosal fibrosis. Consistent with our findings, Zeng et al.16 developed a nomogram model for prediction of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis, but there may be a bias because the extent of the submucosal fibrosis was judged by the subjective assessment of the endoscopists. In our study, we attempted to objectively classify histologic submucosal fibrosis by MT stain and evaluated the agreement between endoscopic and histologic submucosal fibrosis, the results showed that the endoscopic classification directly reflects the histologic classification of submucosal fibrosis with a high degree of concordance.

ESD outcomes according to the degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis

Our results indicate that greater severity of submucosal fibrosis was associated with lower en bloc and curative resection rates, and with higher complication rates such as immediate bleeding and perforation as well as longer procedure times. Submucosal fibrosis often makes it difficult to identify the appropriate submucosal layer, and hinders adequate lifting during submucosal injections in ESD. Accordingly, when submucosal fibrosis is anticipated or detected, ESD should be performed with particular caution and, ideally, by experienced endoscopists.

Application of EUS

Makino et al.21 reported that EUS can be used to predict submucosal fibrosis in colorectal tumors before ESD procedures. However, EUS demonstrates only moderate sensitivity and specificity for predicting submucosal fibrosis. Further studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of EUS. Therefore, in our study, EUS was performed routinely before ESD to evaluate the depth of invasion rather than to predict submucosal fibrosis.

Assisted traction techniques and improved ESD methods

Submucosal fibrosis is one of the factors leading to ESD failure. When submucosal fibrosis occurs in EGC, assisted traction techniques (such as dental floss traction, pulley traction, snare traction, and magnetic anchor traction) and improved ESD methods can be helpful during the ESD procedure. Stier et al.22 proposed the “DeSCAR” technique, which was a hybrid method that involves ESD combined with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for localized removal of non-lifting tissue. This method can be effective for EGC with submucosal fibrosis. Tachikawa et al.23 reported that a large gastric tumor with extensive severe fibrosis was successfully resected using endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection (ESTD) with ring-thread counter traction. Accordingly, when the nomogram predicts a high probability of submucosal fibrosis, pre-procedural planning—including selection of traction methods and advanced techniques—can be undertaken to optimize ESD.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, we did not perform external validation using data from other institutions for this model, which limits external generalizability. Second, because there are no clear criteria for fibrosis, a subjective classification of a submucosal fibrosis from the observer’s point of view may have caused bias. To mitigate this, we assessed concordance between endoscopic and histologic grading and observed strong agreement. Third, our study was a single-center retrospective study and is limited by a small sample size. Fourth, we did not assess the impact of biopsy technique on submucosal fibrosis, including number of biopsies or biopsy site. The appropriate treatment method can differ depending upon the histological categorization, thus, biopsies are usually performed for the patients with EGC to confirm the histological differentiation before ESD in our institution. It is possible that further studies may delineate a relationship between biopsy technique and grade of submucosal fibrosis. Fifth, we included “History of previous gastrectomy or endoscopic submucosal dissection, and the lesion is located near the anastomotic site or wound site” as an exclusion criterion. We believe that there must be submucosal fibrosis at the anastomotic site and wound site after previous gastrectomy or endoscopic submucosal dissection (a determining factor). Because our research focuses on clinical and endoscopic risk factors (rather than determining factors), if “History of previous gastrectomy or endoscopic submucosal dissection, and the lesion is located near the anastomotic site or wound site” is included in the predictive model, its higher weight may mask the role of other features. Finally, in our study, ESD was completed by experienced endoscopists, and the method of ESD was roughly the same, additional factors that may affect ESD outcome and complications, including the expertize of the endoscopist and the method of ESD were not included.

Conclusion

In summary, we identified the risk factors reflected in endoscopic findings of EGC and constructed a visually informative nomogram. Also, we assessed the ESD outcomes according to the degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis and evaluated the relationship between endoscopic and histologic grading. A key strength of this study was the integration of clinical, pathological, and endoscopic variables. The resulting nomogram enables the preoperative prediction of submucosal fibrosis in individual patients, supporting informed and personalized decision-making by clinicians.

Methods and materials

Study design and patients

This retrospective cohort study included consecutive patients diagnosed with EGC who underwent ESD at Fuding Hospital, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine between January 2012 and December 2024. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuding hospital (Approval No: 2024[062]), and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. All procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

ESD indications were based on established guidelines24, including:

-

(1)

UL0 cT1a differentiated-type carcinomas;

-

(2)

UL1 cT1a differentiated-type carcinomas with a tumor diameter ≤ 3 cm;

-

(3)

UL0 cT1a undifferentiated-type carcinomas with a tumor diameter ≤ 2 cm.

Exclusion criteria included:

-

(1)

Absence of postoperative follow-up at our center;

-

(2)

Incomplete clinical data (> 10% missing);

-

(3)

Incomplete ESD, precluding evaluation of submucosal fibrosis.

-

(4)

History of previous gastrectomy or endoscopic submucosal dissection, and the lesion is located near the anastomotic site or wound site.

After screening, 264 lesions from 251 patients were included.

Preparation for ESD

Preoperative examinations included a comprehensive assessment of their general condition. This included routine blood tests, coagulation function analysis, blood biochemistry tests, and an electrocardiogram. In addition, all patients underwent a series of diagnostic endoscopic and imaging procedures: white light endoscopy, magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (NBI), chromoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan and preoperative biopsy. These assessments were conducted to evaluate the histological type, depth of tumor invasion before ESD, and determine the appropriate therapeutic strategy. In cases where deep submucosal invasion was strongly suspected, surgical resection was recommended instead of ESD.

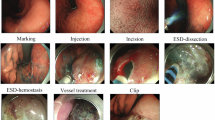

ESD procedure

All patients were placed in the left lateral decubitus position and examined with a standard single-channel endoscope (GIF-H260Z or GIF-Q260J, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), with carbon dioxide insuffation. A disposable distal transparent cap (D−201−11804, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was mounted on the tip of the endoscope. The ESD procedure was performed mainly with a dual knife (KD−650 L, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or an IT knife (KD−611 L, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The ESD procedure was conducted in the sequence of marking, submucosal injection, circumferential incision, and submucosal dissection. Bleeding or exposed vessels were controlled with hemoclips (ROCC-D−26−195, Micro-Tech, Nanjing, China) or hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper, FD−410LR, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a soft coagulation mode. A high-frequency generator (VIO 200D, ERBE, Tubingen, Germany) was used during incision of the mucosa.

Drugs that can increase the bleeding tendency, such as aspirin and warfarin, were discontinued 1 week before ESD. These drugs were restarted about 1 week after ESD if postoperative complications, such as bleeding, did not occur. All patients were administered proton pump inhibitors for 4 to 8 weeks after ESD. ESD procedures were performed by four experienced endoscopists with ≥ 500 ESD cases each, ensuring expertise in advanced therapeutic endoscopy.

Definitions

Comorbidities include cardiovascular diseases, renal diseases, diabetes, and liver cirrhosis. Procedure time was defined as the period from the start of the initial injection to the removal of the lesion. En bloc resection was defined as tumor removal in a single piece without fragmentation. When the lesion was resected en bloc, the following conditions: (1) predominantly differentiated-type, pT1a, UL0, HM0 VM0, Ly0, V0, regardless of size; (2) long diameter ≤ 2 cm, predominantly undifferentiated-type, pT1a, UL0, HM0, VM0, Ly0, V0; or (3) long diameter ≤ 3 cm, predominantly differentiated-type, pT1a, UL1, HM0, VM0, Ly0, V0, was considered for curative resection24. The macroscopic type was based on the Paris classification25 as protruding (I), non-protruding and non-excavated (II), or excavated (III). Type II lesions were subclassified as slightly elevated (IIa), flat (IIb), or slightly depressed (IIc). We generally divided all lesions into two groups: depressed type (IIc and III) and non-depressed type (I, IIa and IIb). The location of EGC was classified into the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the stomach2. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classifications26, patients were categorized into differentiated (papillary, well, and moderately differentiated) and undifferentiated (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or signet ring cell carcinoma) types. Perforation was defined as the intraoperative occurrence of an immediately recognizable hole in the gastric wall or as the presence of free air confirmed on postoperative abdominal X-ray or CT scan. Immediate bleeding was defined as spurting or oozing of blood from a vessel during the ESD procedure. Delayed bleeding was defined as clinical evidence (such as hematemesis or melena) of postoperative bleeding that required emergency endoscopy.

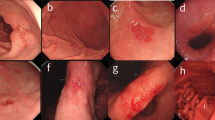

Based on findings obtained by injecting indigo carmine solution into the submucosal layer, the degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis was divided into three types (F0-F2; Fig. 6): F0 (no fibrosis), which appeared as a blue transparent layer; F1 (mild fibrosis), which appeared as a white web-like structure in the blue submucosal layer; and F2 (severe fibrosis), which appeared as a white muscular-like structure without a blue transparent submucosal layer9,10,27. Four experienced endoscopists independently reviewed fibrosis grades in a double-blind manner, with no access to patient demographics or histopathologic results.

Degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis in early gastric cancer. (A,B) F0 (no fibrosis), which appears as a blue transparent layer. (C,D) F1 (mild fibrosis), which appears as a white web-like structure in the blue submucosal layer. (E, F) F2 (severe fibrosis), which appears as a white muscular structure without a blue transparent layer in the submucosal layer.

Histopathological assessment

Endoscopically resected specimens were fixed in formalin, serially sectioned at 2-mm intervals and embedded in paraffin, with sections centered on the portion of the lesion closest to the margin and the site of deepest invasion. The slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Differentiation, depth of invasion, submucosal fibrosis, lymphatic and vascular involvement, and tumor involvement at the lateral and vertical margins were assessed histologically.

Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining was used to evaluate histologic submucosal fibrosis and the collagen was stained blue (Fig. 7). First, the intensity of fibrosis was scored as 0 (no fibrosis, nearly normal appearance), 1 (weak fibrosis), or 2 (dense fibrosis). Then, the extent of the fibrosis was scored as 0 (0 ~ 10%), 1 (11 ~ 50%), or 2 (51 ~ 100%) based on the percentage of the total area. The final fibrosis score was calculated as the sum of the scores for the extent and intensity, as follows: 0 was defined as f0 (no fibrosis), 1 and 2 were defined as f1 (mild fibrosis), and 3 and 4 were defined as f2 (severe fibrosis)9,10,28,29. Two experienced pathologists independently reviewed fibrosis grades in a double-blind manner, without access to patient demographics or endoscopic results.

Data collection

The demographic characteristics (including age, sex, comorbidities and antithrombotic drugs use), clinicopathological characteristics (including tumor size, macroscopic type, tumor location, endoscopic submucosal fibrosis, and histopathological assessment) and the outcomes of ESD (including procedure time, en bloc resection rate, curative resection rate and complication rate) were collected.

Statistical analysis

All lesions were randomly divided into 184 EGC lesions in the training cohort and 80 EGC lesions in the validation cohort in a ratio of 7:3. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normal distribution of variables. Non-normally distributed data were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables were demonstrated as number with percentage and compared using the Chi-square (χ2) or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables were compared between groups using the Mann-Whitney U-test or Kruskal-Wallis H test. Univariable analysis was conducted to identify the factors associated with submucosal fibrosis in EGC. For the multivariable analysis, we included only those variables with P values < 0.05 in the univariate analysis as the independent influencing factors, which were utilized to construct a nomogram prediction model. The results were presented as odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and P value. We constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and calculated areas under the curves (AUCs) for the training and validation cohorts. The discriminatory capacity of the model was evaluated using AUCs. The calibration of the nomogram was evaluated by the calibration curves and the Hosmer-Lemeshow (H-L) test. The net benefit ratio of the model across various threshold probabilities was evaluated by the decision curve analysis (DCA). The kappa statistic was used to measure the agreement between endoscopic and histologic submucosal fibrosis.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249 (2021).

Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 3rd english edition. Gastric Cancer. 14 (2), 101–112 (2011).

Kim Y I, Kim Y W, Choi I, J. et al. Long-term survival after endoscopic resection versus surgery in early gastric cancers. Endoscopy 47 (4), 293–301 (2015).

Tae, C. H. et al. Comparison of subjective quality of life after endoscopic submucosal resection or surgery for early gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 10 (1). (2020).

Lee, S. et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery in early gastric cancer meeting expanded indication including undifferentiated-type tumors: a criteria-based analysis. Gastric Cancer. 21 (3), 490–499 (2018).

Kuroki, K. et al. Preceding endoscopic submucosal dissection in submucosal invasive gastric cancer patients does not impact clinical outcomes. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 990 (2021).

Japanese Gastric Cancer. Treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer 20 (1), 1–19 (2017).

Kim, J. H. et al. Risk factors associated with difficult gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: predicting difficult ESD. Surg. Endosc. 31 (4), 1617–1626 (2017).

Jeong, J. Y. et al. Does submucosal fibrosis affect the results of endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric tumors?. Gastrointest. Endosc. 76 (1), 59–66 (2012).

Higashimaya, M. et al. Outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm in relationship to endoscopic classification of submucosal fibrosis. Gastric Cancer. 16 (3), 404–410 (2013).

Ma, X. et al. Risk factors and prediction model for Non-curative resection of early gastric cancer with endoscopic resection and the evaluation. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 637875 (2021).

Ohnita, K. et al. Factors related to the curability of early gastric cancer with endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg. Endosc. 23 (12), 2713–2719 (2009).

Fujishiro, M. et al. Successful nonsurgical management of perforation complicating endoscopic submucosal dissection of Gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasms. Endoscopy 38 (10), 1001–1006 (2006).

Isomoto, H. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut 58 (3), 331–336 (2009).

Konuma, H. et al. Procedure time for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection according to location, considering both mucosal circumferential incision and submucosal dissection. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 9183793. (2016).

Zeng, Y. et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for submucosal fibrosis in patients with early gastric cancer undergoing endoscopic submucosal dissection: experience from a large tertiary center. Ann. Med. 56 (1). (2024).

Huhl, C. W., et al. Predictive factors of submucosal fibrosis before endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial squamous esophageal neoplasia. Clin. Translational Gastroenterol. 9 (6). (2018).

Hayashi, N. et al. Predictors of incomplete resection and perforation associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Gastrointest. Endosc. 79 (3), 427–435 (2014).

Matsumoto, A. & Tanaka, S. Outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors accompanied by fibrosis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 45 (11), 1329–1337 (2010).

Zhou, Y. & Li, X. B. Endoscopic prediction of tumor margin and invasive depth in early gastric cancer. J. Dig. Dis. 16 (6), 303–310 (2015).

Makino, T. et al. Preoperative classification of submucosal fibrosis in colorectal laterally spreading tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography [J]. Endoscopy Int. Open. 03 (04), E363–E7 (2015).

Stier, M. W., Chapman, C. G., Kreitman, A., et al. Dissection-enabled scaffold-assisted resection (DeSCAR): a novel technique for resection of residual or non-lifting GI neoplasia of the colon (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 87 (3), 843–851 (2018).

Tachikawa, J. et al. Endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection with ring-thread countertraction for a large gastric tumor with extensive severe fibrosis. VideoGIE 6 (1), 11–13 (2021).

Ona, H. et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer (second edition). Dig. Endosc. 33 (1), 4–20 (2021).

The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic. Lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest. Endosc. 58 (6 Suppl), S3–43 (2003).

Nagtegaal I D, Odze R D, Klimstra D, et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 76 (2), 182–188 (2020).

Kuroha, M. et al. Factors associated with fibrosis during colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: does pretreatment biopsy potentially elicit submucosal fibrosis and affect endoscopic submucosal dissection outcomes?. Digestion 102 (4), 590–598 (2021).

Chiba, H. et al. Predictive factors of mild and severe fibrosis in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig. Dis. Sci. 65 (1), 232–242 (2019).

Lee S P et al. Effect of submucosal fibrosis on endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal tumors: pathologic review of 173 cases. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 30 (5), 872–878 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1. L. designed the study and wrote the manuscript; Y-W. L. and D-D. Z. collected the data and images; S-Y. Z. analyzed the data; Y-L. W. supervised the implementation of the whole process. All authors approved the final manuscript and believe that the manuscript represents honest work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Zhang, SY., Li, YW. et al. A nomogram to predict submucosal fibrosis in early gastric cancer undergoing endoscopic submucosal dissection. Sci Rep 15, 41719 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25725-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25725-7