Abstract

Sandwich cylindrical structures are widely used in various industries, including high-speed trains, automotive, and civil engineering applications. To improve their performance, integrating polymeric foam cores and various configurations of periodic stiffeners into sandwich cylindrical shells significantly enhances their noise-cancellation capabilities. This paper investigates, for the first time, the acoustic parameters of sound transmission loss (STL) and noise reduction (NR) in an infinitely long sandwich cylindrical shell reinforced with annular and axial stiffeners (rings and strings), considering the effects of open-cell and closed-cell foams. The cross-sectional architecture consists of three layers: a functionally graded (FG) outer layer, an FG polymeric foam core, and an isotropic inner layer. Fluid (air) fills the gaps between the layers, and the shell is submerged in an external fluid medium while subjected to excitation by a plane acoustic wave. The outer and inner layers are further strengthened by circumferential and axial stiffeners. The polymeric foam core plays a crucial role in absorbing and dissipating sound energy, significantly enhancing the structure’s acoustic insulation properties. Meanwhile, the ring and string stiffeners improve overall mechanical stiffness, ensuring structural integrity and reducing vibrations. To address this problem, the motion equations of the shell are derived using the first-order shear deformation theory (FSDT) and Hamilton’s principle. The Zener viscoelastic model, which accounts for the frequency-dependent variation of material properties, is employed to model the viscoelastic core. The acoustic parameters are calculated by incorporating boundary conditions and fluid–structure interaction effects. Among the various reinforcement configurations, the highest STL and NR are achieved when both the inner and outer layers are reinforced, significantly improving vibration damping and acoustic insulation. When only the outer layer is reinforced, the structure performs better in the mass-controlled region, while reinforcing only the inner layer leads to superior performance in the stiffness-controlled region. Furthermore, open-cell foam outperforms closed-cell foam at higher frequencies due to its superior damping properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In modern industrial applications, optimizing structural components is essential for enhancing performance, durability, and cost-effectiveness. Sandwich structures with polymeric foam cores, periodically reinforced by rings and strings, play a significant role in industries such as aerospace, mechanical engineering, and transportation1. These structures are extensively utilized in applications such as high-speed train body panels, pressure vessels, and reticulated shell cooling towers due to their lightweight design, high strength, and superior noise-damping properties2,3. NR is a critical challenge in these applications, as excessive noise can induce detrimental vibrations, potentially leading to structural failure and compromising safety and longevity. For example, in pressure vessels used for storing pressurized gases or fluids, dynamic pressures and flow turbulence generate noise that can cause harmful vibrations, threatening the vessel’s long-term integrity. Similarly, in high-speed trains, aerodynamic forces and structural vibrations can degrade passenger comfort and reduce structural performance. To address these challenges, integrating polymeric viscoelastic materials into composite structures has emerged as an effective strategy. These materials, combined with periodic reinforcements, improve load-bearing capacity, enhance vibration resistance, dissipate vibrational energy, and minimize noise transmission. This study focuses on advancements in NR techniques for cylindrical shells, highlighting the combined effects of reinforcements and viscoelastic materials in improving structural integrity and dynamic response. It emphasizes recent innovations and methodologies that contribute to progress in this field.

As some of the earliest works, many researchers have investigated the dynamic and acoustic response of ring-stiffened circular cylindrical shells4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Lee and Kim11 obtained the first exact solution for sound transmission through stiffened cylindrical shells, considering full coupling effects between the structure and acoustic media, by deriving the system equation using Love’s equations to describe shell motion and applying the virtual energy method. Kim et al.12 presented a theoretical approach for analyzing the coupled vibration characteristics of ring-stiffened cylindrical shells partially filled with an inviscid, incompressible fluid, incorporating bulging and sloshing modes and employing the Rayleigh–Ritz method based on Love’s thin shell theory to derive the frequency equation. Yan et al.13 formulated an analytical method to assess the radiated sound power characteristics of an infinitely submerged periodically stiffened cylindrical shell excited by a harmonic force, investigating the role of stiffeners in sound radiation across different frequency domains and proposing strategies for noise mitigation. Maxit and Ginoux14 developed a numerical model intended for forecasting the vibro-acoustic response of an externally fluid-loaded shell, which incorporates non-uniformly spaced stiffeners and transverse bulkheads. Using an analytical method grounded in periodic structure theory, Lee et al.15 explored the wave propagation responses of a thin cylindrical shell reinforced with periodically spaced ring frames and axial stringers. Cao et al.16 formulated an analytical model to explore the acoustic radiation from shear deformable laminated cylindrical shells subjected to initial axial loadings and equipped with doubly periodic rings. The model integrates the effects of shear deformation and rotary inertia of the rings, which interact with the shell through normal forces. An analytical method was developed by Liao et al.17 to study the sound radiation from a finite submerged cylindrical shell with periodic axial stiffeners under radial harmonic excitation. They derived and incorporated the additional impedance of the stiffeners into the vibration and sound radiation equations. Their results showed that shell vibration and sound radiation are governed by mechanical, radiation sound, and stiffener impedances. Numerical simulations indicated that axial stiffeners have a minor influence on radiated sound power, but structural damping greatly affects radiated power and radial quadratic velocity, offering guidance for NR strategies. Shen et al.18 developed an analytical periodic model to predict sound radiation from orthogonally stiffened laminated plates, considering flexural-torsion coupling effects. Their results showed significant influences of material properties and geometry on acoustic radiation. In another study, Shen et al.19 investigated sound transmission across stiffened composite sandwich panels using FSDT and space harmonic expansion, demonstrating stiffener and laminate layup effects on mid-high frequency performance. An improved wave finite element Method was proposed by Hong et al.20 to predict the band-gap behavior of periodically stiffened shell structures commonly found in transportation systems. It was demonstrated that out-of-plane vibrations within the target frequency range could be effectively reduced by adjusting the geometric parameters of the stiffeners. Dung et al.21 carried out an analytical investigation on the free vibration behavior of rotating functionally graded truncated conical shells reinforced with rings and stringers placed at varying intervals. They employed Donnell shell theory along with the smeared stiffener approach and incorporated the effects of both centrifugal and Coriolis forces in their analysis. The vibroacoustic response and acoustic scattering of an indefinitely long cylindrical shell featuring periodic lengthwise ribs were investigated by Tong et al.22,23. By modeling the ribs as elastic beams with longitudinal and flexural vibrations and using the Donnell equations to describe the motion of the shell, they found that the periodic ribs induce multi-order flexural Bloch waves that include supersonic components that radiate efficiently and cause acoustic radiation resonances in the far field. A semi-analytical approach to modeling the vibroacoustic response of submerged cylindrical shells with periodic axisymmetric stiffeners, subjected to excitation by a homogeneous and fully developed turbulent boundary layer, was introduced by Maxit et al.24. In a related study, Pan et al.25 implemented a symplectic wave-based approach to study the vibro-acoustic dynamics of submerged cylindrical shells with periodic ring stiffeners. Their research included the effects of hydrostatic pressure and the interaction between the acoustic environment and the shell structure. They found that hydrostatic pressure is necessary for accurate low-frequency near-field acoustic pressure analysis, but not for other conditions. Zarei et al.26 examined the vibrations of composite conical shells with bevel stiffeners using experimental, analytical, and numerical methods. They applied the smeared method to model stiffness variations and solved the governing equations with the Ritz method. In another work, Zarei et al.27 employed the vibration correlation technique to predict the buckling load of grid-stiffened composite conical shells without causing structural failure. Using filament winding, they fabricated the shell and measured its fundamental frequency under incremental axial compression. Yang and Seong28 derived the acoustic radiation efficiency of a submerged, finite-length cylindrical shell periodically stiffened with rings, assuming a finite vibration distribution and simple supported boundary conditions. They also compared the acoustic radiation efficiency of finite-length and infinite-length cylindrical shells as functions of frequency and length. Recently, Banijamali and Jafari29 analyzed the critical speeds and frequency response of rotating functionally graded conical shells with anisogrid stiffeners. Using the smeared method, they derived motion equations via Hamilton’s principle and solved them with the generalized differential quadrature method, accounting for shear deformation, rotational inertia, and Coriolis effects. In addition, Ansari et al.30 examined the vibrational behavior of truncated spherical shells reinforced with non-uniform grid stiffeners arranged in a truss-like configuration. The helical stiffeners, considered as elements that carry only axial forces, were incorporated into the model using an equivalent stiffness approach. Donnell’s shell theory was used to formulate the governing equations, and the Galerkin method was applied to determine the natural frequencies under various edge conditions, such as clamped, simply supported, and mixed boundaries. In a recent contribution to the field of semi-analytical modeling, Sun et al.31 proposed a framework to analyze the dynamics of cylindrical shells reinforced with orthogonal stiffeners. Their approach involved formulating displacement expressions through a semi-analytical technique, while employing Sanders’ shell theory to establish the mechanical behavior of the stiffening elements. They utilized Lagrange’s equations to derive the dynamic response of the complete system and determined the stiffness of the boundary springs through an inverse analysis method. Then, Esmaeilzadehazimi et al.32 studied ring-stiffened conical shells under fluid loading using a hybrid finite element method, incorporating exact solutions from Sanders’ shell equations. They derived an explicit expression for fluid pressure and investigated the effects of geometry, stiffeners, and boundary conditions on natural frequencies. Yu et al.33 employed a semi-analytical method to study the vibro-acoustic behavior of a coupled plate–cylindrical shell system with ring stiffeners in a light fluid. They analyzed structural intensity to trace vibration energy paths and showed that energy dissipation was mainly due to structural damping, while acoustic radiation had a minor role. Subsequently, Asadi et al.34 presented vibration models for ring-stiffened or supported cylindrical shells based on three-dimensional elasticity theory. The structures were divided into multiple subdomains depending on ring configuration. Governing equations were derived using Hamilton’s principle, and a two-directional generalized differential quadrature method was applied to solve them. Machine learning techniques were applied by Tabish et al.35 to predict failure modes and buckling strength of ring-stiffened cylindrical storage tanks under uniform external pressure.

The dynamic and vibrational responses of structures, including plates and cylindrical shells with viscoelastic layers and interfaces, have been widely studied by many scholars. For example, Barshinger and Rose36 analyzed the behavior of ultrasonic guided waves traveling through an elastic cylindrical shell coated with a viscoelastic material, aiming to develop tools for the nondestructive testing of coated piping and tubing. Chen and Lee37 studied the cylindrical bending behavior of a simply supported laminated plate exposed to static loading, incorporating the influence of viscous interfaces. Their method precisely addressed conditions at viscous interfaces using the power series expansion technique, showing the effectiveness of the state-space approach within small time intervals and facilitating step-by-step responses of the laminate. In another study, Chen et al.38 extended this method to explore the three-dimensional response of a simply-supported laminated cylindrical panel. Yan et al.39 explored the cylindrical bending response of a simply supported laminated cylindrical shell, focusing on viscoelastic interfaces by using the viscoelastic Kelvin–Voigt model. Altenbach and Eremeyev40,41 proposed a new plate theory using the direct approach to capture the viscoelastic behavior of open-cell and closed-cell foams in functionally graded material (FGM) plates. The research by Mohammadi and Sedaghati42,43 introduced a novel higher-order Taylor expansion technique for displacement fields within the viscoelastic core layer, providing insights into the damping properties and optimum vibrational status of sandwich cylindrical shells while addressing slippage between layers at the interfaces. Akbarov and Kepceler44 examined the dispersion characteristics of torsional waves in a sandwich cylindrical shell constructed using linear viscoelastic materials. In another study, Akbarov et al.45 studied the propagation of axisymmetric longitudinal fundamental waves in a bi-layered cylindrical shell constructed from linear viscoelastic materials using exact equations of linear viscoelasto-dynamics. Hosseini-Hashemi et al.46 developed a state-space approach to accurately examine the free vibrations of functionally graded viscoelastic (FGV) panels subjected to Levy-type boundary conditions. They employed an antisymmetric power law distribution function and the Zener relation to represent the material characteristics, particularly suitable for substances such as polymeric foams. The cylindrical panel’s geometry was modeled using Sanders’ shear deformation theory. In the following, the limited studies concerning the interaction between sound and structures containing polymer foam will be briefly discussed. Ayres and Gaunaurd47 conducted the first examination of acoustic scattering from a viscoelastic sphere, utilizing the Kelvin–Voigt model. Mofakhami et al.48 studied the NR of multilayered viscoelastic cylindrical shells containing air and subjected to sound waves. They employed the separation of variables technique, based on the three-dimensional theory of elasticity. Abid et al.49 proposed a method to predict the acoustic behavior of viscoelastic multilayered panels using the transfer matrix method. Larbi et al.50 introduced a finite element method for analyzing sound transmission through double-wall sandwich panels with a viscoelastic core, using the Rayleigh integral method. The research by Amirinezhad et al.51 focused on sound transmission through a polymeric foam plate submerged in fluid and subjected to acoustic wave excitation, using the FSDT. The plate’s viscoelastic behavior was simulated with the Zener model. Talebitooti et al.52 analyzed acoustic wave transmission through a cylindrical shell with a viscoelastic core, excited by an oblique plane wave, utilizing three-dimensional elasticity theory. The viscoelastic core’s frequency-dependent complex modulus was modeled using the Havriliak-Negami approach to simulate polymeric relaxation behavior. Reaei et al.53 formulated an analytical solution to determine the STL in a polymeric foam cylindrical shell, subjected to excitation by an acoustic plane wave, using the FSDT. Tarkashvand et al.54 presented a new method employing an FGV model to study the acoustic responses of a submerged sandwich shell in fluid. The structure, analyzed using elasticity theory and the transfer matrix function, included two isotropic shells and a core made of open-cell and closed-cell foams. The Zener model was used to characterize the viscoelastic properties of the foam.

In the context of fluid–structure–acoustic interaction, the noise attenuation characteristics of periodically stiffened sandwich cylindrical shells with viscoelastic polymeric foam cores remain largely underexplored, despite their relevance to automotive, civil infrastructure, and industrial machinery applications. This study addresses this gap by developing a comprehensive analytical framework capable of predicting the full frequency response of such structures, accounting for the coupled effects of periodic stiffeners (both axial and circumferential), FG face layers, and viscoelastic foam cores under fluid–structure interaction. The framework integrates the FSDT with the Zener viscoelastic model to evaluate key acoustic metrics, specifically STL and NR, for an infinitely long cylindrical sandwich shell submerged in a fluid medium and subjected to oblique acoustic excitation. The shell consists of an isotropic inner layer, a polymeric foam core with thickness-dependent properties modeled using a power-law distribution, and an FG outer layer. Orthogrid stiffeners are attached to both the inner and outer layers. The Zener model captures the frequency-dependent damping behavior of the foam core, while FSDT and Hamilton’s principle are employed to derive the governing equations of motion. The acoustic parameters are calculated by incorporating appropriate boundary conditions and fluid–structure interaction effects. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on flat panels or unstiffened shells, this work systematically investigates the influence of stiffener geometry, spacing, material composition, reinforcement configuration, and foam type (open-cell and closed-cell) on noise reduction performance. The results reveal new design strategies, demonstrating how specific combinations of core material and stiffener layout can be used to control sound transmission across a wide frequency range. These findings contribute to the theoretical modeling of sandwich shell systems submerged in fluid and offer practical guidance for designing lightweight, low-noise components in automotive systems, civil engineering structures, and industrial equipment.

Analytical framework for acoustic-structural simulation

System description

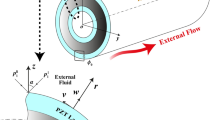

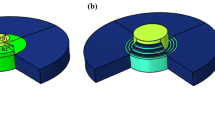

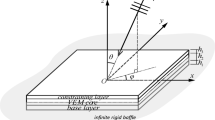

The general problem configuration and coordinate system are depicted in Fig. 1a. A polymeric foam core sandwich cylindrical shell of infinite length has an internal radius \({R}_{\text{in}}={R}_{6}-{h}_{6}/2\) and an external radius \({R}_{\text{ex}}={R}_{2}+{h}_{2}/2\). This shell includes a polymeric foam core layer with a thickness \({h}_{4}\), separated from the outer and inner layers by air gaps (see Fig. 1b). The outer layer consists of an FGM with a thickness of \({h}_{2}\), whereas the inner layer is composed of an isotropic material with a thickness of \({h}_{6}\). As illustrated in Fig. 1c, the inner and outer layers are reinforced with circumferential and axial stiffeners (rings and strings). This sandwich structure is completely submerged in a uniform inviscid fluid flow and excited by a sound wave with an incident angle ψ (\({0}^{^\circ }<\psi <{90}^{^\circ }\)) measured from the x-axis. The FG coating is composed of two materials: aluminum (Al) and zirconia (ZrO2). The mixing ratio varies continuously in the radial direction, with the exterior and interior surfaces enriched with Al and ZrO2, respectively. A cylindrical coordinate system \((r\text{, }\theta \text{, }z)\) is established to define the spatial orientation. Furthermore, the acoustic media parameters \({\rho }_{1}\), \({\rho }_{3}\), \({\rho }_{5}\), \({\rho }_{7}\) and \({c}_{1}\), \({c}_{3}\), \({c}_{5}\), \({c}_{7}\) represent the density and speed of sound outside, in between (air gaps), and inside the shells, respectively.

Governing equations of the periodically stiffened sandwich cylindrical shells with polymeric foam core

In this study, the FSDT is employed to model each three-layer cylindrical shell. This theory considers displacement fields based on stress–strain relations and incorporates the effects of inertia moments and shear stresses. From the perspective of the FSDT, lines perpendicular to the mid-surface of the shell remain straight after deformation but are not normal to the mid-surface. Consequently, transverse shear strains emerge in the equations. Therefore, the displacement fields based on FSDT can be expressed as follows46,55,56,57:

where t represents time; U, V, and W are the displacement components at any point in the axial, circumferential, and radial directions, respectively; u, v, and w are the displacements of the shell’s middle surface in the axial, circumferential, and radial directions, respectively; and \({\varphi }_{z}\), \({\varphi }_{\beta }\) denote the mid-surface transverse rotations about the z- and β- axes at r = R. The relationship between strain and displacement in cylindrical coordinates based on the FSDT and considering the displacement fields in Eq. (1) is expressed as follows56,58:

where \({\varepsilon }_{ij}\) (i, j = r, β, z) are strain tensor components. It is worth mentioning that in this theory, the strains perpendicular to the surface (in the r direction) are assumed to be zero (\({\varepsilon }_{r}=0)\). The connection between the components of stress and strain tensors is derived as follows53,56:

where \({\sigma }_{ij}\) (i, j = r, β, z) are stress tensor components, and \({Q}_{kl}\) \((k,l=1, 2, 4, 5, 6)\) are elastic coefficients that depend on frequency \((\omega )\) and the \(r\)-coordinate. These coefficients can be expressed based on the mechanical properties of materials as follows:

Here, \(E(r,\omega )\), \(G(r,\omega )\), and \(\vartheta (r,\omega )\) respectively represent the modulus of elasticity, shear modulus, and Poisson’s ratio. The resultant forces and moments of a structure are generally defined by integrating stress over the thickness of the structure. The resultant forces and moments for a cylindrical structure, considering the curvature effect \(r/R\), are expressed as follows46:

where \({N}_{ij}\) are the force resultant components, \({M}_{ij}\) are the moment resultant components, and \({Q}_{ij}\) are the resultants due to transverse shear forces. Additionally, \({f}_{c}\) is a shear correction factor used to improve the transverse shear rigidity of the shell in the FSDT56. It is worth mentioning that the radii of curvature in the z and β directions are not necessarily equal. Therefore, although \({\sigma }_{z\beta }={\sigma }_{\beta z}\), the force and moment resultants \({N}_{z\beta }\) and \(Mz\beta\) are not necessarily equal to \({N}_{\beta z}\) and \({M}_{\beta z}\). The resultant components of forces, moments, and shear forces for a general case are obtained as follows:

In this study, three types of materials are used for the layers: FGM, FGV, and isotropic materials. Additionally, isotropic materials have been considered for the reinforcements. Below, the mechanical properties of the materials and the governing relationships for each layer are explained. In FGMs, material characteristics vary smoothly and continuously from one surface to another, with metal and ceramic constituting the internal and external surfaces, respectively. The effective material properties, denoted by q, of FGMs are a function of the volume fraction of the constituents and material properties. This function, q, can be expressed as52:

where \({q}_{c}\) and \({q}_{m}\) represent the material properties of ceramic and metal, respectively, and \({V}_{c}\) and \({V}_{m}\) represent their volume fractions. It’s notable that \({V}_{c}+{V}_{m}=1\). For an FGM shell with a reference surface at its mid-surface and a uniform thickness \({h}_{2}\), the volume fraction relationship based on the power-law formulation can be written as follows:

where N is the power-law exponent and takes only positive values \((0\le N\le \infty )\). By considering \(N=0\), the FGM transforms into a pure ceramic material, while with \(N=\infty\), it transforms into a pure metal. By combining Eqs. (7) and (8), the following relationships for variations in properties in the thickness direction r can be obtained52:

where \({E}_{2}\), \({\rho }_{2}\), and \({\vartheta }_{2}\) denote the elastic modulus, mass density, and Poisson’s ratio of the FG layer, respectively. After determining the variations in mechanical properties along the thickness direction of the FG layer (Eq. (9)), by substituting Eqs. (9) and (3) into Eqs. (5), the resultant force and moment components for the FG layer are obtained, as presented in Appendix A.

A basic linear viscoelasticity principle states that the stress function is linearly dependent on the history of the strain function as a function of time, as follows:

where \({\sigma }_{4}\left(t\right)\), \({\varepsilon }_{4}(\tau )\), and \(\upeta(t)\) denote the stress, strain, and relaxation functions for the polymeric foam core, respectively. Various models can be used to approximate the behavior of viscoelastic materials. The most commonly used constitutive relations for viscoelastic materials, such as metallic and polymeric foams, are the simple viscoelastic models combined with homogeneous isotropic models. The Zener viscoelastic model, which is dependent on the thickness, is utilized as the best mathematical model for foams as the constitutive relation. Thus, a linear Zener model with three parameters, with constitutive Eq. (11) as shown in Fig. 2, has been considered. The relationship between stress and strain for the Zener model is expressed as follows53:

where \({E}_{\text{4,1}}\) is the instantaneous elastic modulus of the parallel spring element (providing the instantaneous/unrelaxed stiffness of the Zener model), \({E}_{4}\) is the elastic modulus of the series spring in the Maxwell arm, and \({\mu }_{4}\) is the damping coefficient of the dashpot in the Zener model. For the defined model, Eq. (11) can be equivalently expressed in differential form as follows59:

where \({T}_{4}\) is the relaxation time constant of the Maxwell arm (series spring and dashpot), \({T}_{\text{4,1}}\) is the relaxation time constant associated with the parallel spring, and \(T\) is the total relaxation time constant. Here, \({G}_{4}\) is the shear modulus of the spring in the Maxwell arm (in series with the dashpot), and \({G}_{\text{4,1}}\) is the shear modulus of the spring connected in parallel to the Maxwell arm. In vibroacoustic analysis, stress and strain are frequency-dependent and are defined as follows:

where \({\sigma }_{0}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{0}\) are the complex stress and strain amplitudes, respectively, and \(i=\sqrt{-1}\) is the imaginary unit. By substituting Eqs. (13) into (12), the bulk and shear complex modulus are described as follows:

where \(\omega\) is the frequency and \(\xi =\frac{{T}_{\text{4,1}}}{T}\). It’s important to note that, in expansion, such foams exhibit elastic behavior, thus the bulk modulus \({K}_{0}\) remains constant with respect to frequency. Additionally, it’s noteworthy that the Zener model reduces to the Kelvin and elastic models by setting \(\xi =0\) and \(\xi =1\), respectively. Using elasticity relations, the elasticity modulus and Poisson’s ratio can be obtained as follows46:

For polymeric foam materials, property variations based on the power-law distribution \({V}_{4}\left(r\right)\):

Here, \(g\) represents the index of the power law, and \(\alpha =\frac{{\rho }_{p}}{{\rho }_{s}}\) is the minimal relative density, where \({\rho }_{s}\) is the density of the solid polymer and \({\rho }_{p}\) is the minimum value of the density within the foam layer40. Thus, by incorporating Eq. (16) into Eqs. (15) and (14), variations of the mechanical properties for polymeric foam materials are formulated as follows46:

For \(\phi <1\), the foam is classified as closed-cell, while for \(\phi =1\), it is considered open-cell. It’s important to mention that, according to experimental results, Poisson’s ratio remains constant throughout the thickness60,61. After determining the variations in mechanical properties along the thickness direction of the polymeric foam layer (Eq. (17)), and following a similar procedure to the FG layer by substituting Eqs. (17) and (3) into Eq. (5), the resultant force and moment components for the polymeric foam layer are obtained.

The stress–strain relation for ring and string stiffeners can be derived as follows62,63:

where the indices \(r\) and \(s\) refer to the circumferential (ring) and axial (string) reinforcements, respectively. The terms \({\sigma }_{\beta \beta }^{r}\), \({\sigma }_{\beta r}^{r}\) , \({\sigma }_{zz}^{s}\), and \({\sigma }_{zr}^{s}\) represent the stress components, while \({E}^{r}\) and \({E}^{s}\) denote the elasticity modulus, and \({G}^{s}\) and \({G}^{r}\) are the shear moduli for the ring and string reinforcements, respectively. Based on these relations, the stress and moment resultants for the stiffeners can be expressed as follows62,63:

Rings and strings at the inner surface of the FG layer:

Rings and strings at the outer surface of the isotropic layer:

In these equations, \({D}_{ri}\) and \({D}_{si}\) are the widths, \({h}_{ri}\) and \({h}_{si}\) are the heights, and \({B}_{ri}\) and \({B}_{si}\) are the center-to-center spacings of the ring and stringer stiffeners, respectively. These parameters are depicted in Fig. 3 for the rings and strings attached to the inner isotropic layer. Additionally, these parameters are defined similarly for the outer FG layer.

To derive the governing equations of motion in the FSDT, Hamilton’s principle has been employed. Therefore, considering the assumptions, the kinetic energy \((T)\), the strain energy \((S)\), and the work applied by an external force \(({W}_{e})\) can be obtained as follows53,62,64:

where \({\rho }_{s1}\) and \({\rho }_{s2}\) are the material densities of the outer and inner strings, respectively; \({\rho }_{r1}\) and \({\rho }_{r2}\) are the material densities of the outer and inner rings, respectively; \({S}^{s1}\) and \({S}^{s2}\) are the strain energies contributed by the outer and inner strings, respectively; \({S}^{r1}\) and \({S}^{r2}\) are the strain energies contributed by the outer and inner rings, respectively; \({T}^{s1}\) and \({T}^{s2}\) are the kinetic energies of the outer and inner strings, respectively; and \({T}^{r1}\) and \({T}^{r2}\) are the kinetic energies of the outer and inner rings, respectively. By substituting the stress resultants Eqs. (5) into Eqs. (21), the equation of motion for a cylindrical layer can be expressed as59,65,66,67:

where \({q}_{r}\), \({q}_{\beta }\), and \({q}_{z}\) represent the external forces per unit area along the respective coordinate axes, while \({I}_{i}\) denotes the mass moment of inertia of the single-layer shell. These quantities are calculated as follows:

where \({P}^{R}\), \({P}^{I}\), and \({P}^{T}\) denote the incident wave pressure, the reflected wave pressure, and the transmitted wave pressure, respectively. For reinforcements, by substituting the stress resultants Eqs. (19) and (20) into Eqs. (21), the equations of motion for the reinforcements are obtained as follows62:

where \({I}_{i}^{sr}\) is the inertia moment of the stiffener, which can be calculated as:

Acoustic equations and problem-solving approach

The acoustic equations that govern the propagation of sound waves in the external, interlayer, and internal spaces are formulated to account for wave dynamics in each region. These equations incorporate the influence of sound speed, pressure variations, and time-dependent terms to describe the behavior of incident, reflected, and transmitted acoustic waves68. They can be mathematically expressed as follows69:

where \({V}_{1}{\prime}\), \({V}_{3}{\prime}\), and \({V}_{5}{\prime}\) represent the velocity of the fluid medium in the external environment, the first internal air gap (between the FG layer and the foam core), and the second internal air gap (between the foam core and the inner isotropic layer), respectively. The operator \({\nabla }^{2}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}}{{\partial r}^{2}}+\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial }{\partial r}+\frac{1}{{r}^{2}}\frac{{\partial }^{2}}{{\partial \theta }^{2}}+\frac{{\partial }^{2}}{{\partial z}^{2}}\) denotes the 3D Laplacian in the cylindrical coordinates. As previously mentioned, the structure is subjected to plane-waves inclined. Therefore, the wave numbers in the axial and radial directions can be defined as follows69:

where \({M}_{1}\) represents the Mach number, \({k}_{i}(i=\) 1, 3, 5, 7) are the wave numbers within the structure, \({k}_{ir}\) and \({k}_{iz}\) denote the wave numbers in the radial and axial directions, respectively. Figure 4 illustrates the acoustic pressures applied to each layer of the sandwich structure. The wave pressure terms in Eqs. (26) are defined as follows69,70:

where \({P}_{0}\) is the amplitude of the indicated wave pressure, \(n\) indicates the circumferential mode number, \({H}_{n}^{1}\) and \({H}_{n}^{2}\) are the first and second kinds of Hankel function of order \(n\), respectively, \({J}_{n}\) is the first kind of Bessel function of order \(n\). Additionally, \({\varepsilon }_{n}\) represents the Neumann factor and is expressed as follows:

The displacement and rotation terms of the structure can be considered as infinite series53:

Given that the length of the cylindrical structure is assumed to be infinite, no boundary conditions are considered in the longitudinal direction of the cylinder. Therefore, considering the coupling between the fluid medium and the cylindrical shell, the boundary conditions in the radial direction are expressed as follows69:

Therefore, by substituting the above relations into Eqs. (22) to (30), the equations of motion, considering the three shells and coupling the equations of the stiffeners and the outer shell, are obtained in the following matrix form:

where \({\left[B\right]}_{21\times 21}\) is the coefficient matrix, \({\left\{Y\right\}}_{21\times 1}\) is the vector of applied acoustic forces, and \({\left\{X\right\}}_{21\times 1}\) is the vector representing the unknowns, which includes 9 displacement components, 6 rotational components about the z and β axes of the cylindrical structure, and 6 amplitudes of the reflected and transmitted pressures. The terms of the unknown vector are as follows:

The equations of motion are given in Appendix B.

Sound transmission loss and noise reduction calculation

The STL coefficient is defined as the ratio of the power of the incident sound wave to the power of the transmitted sound wave per unit length of the shell, as follows71,72:

where \({W}^{I}\) and \({W}^{T}\) represent the power of the incident and transmitted sound waves, respectively, and are computed as follows:

Considering \(={R}_{6}\),

where \(Re\{\cdot \}\) denotes the real part and the superscript * indicates the complex conjugate of the argument. Thus, substituting Eqs. (35) and (36) into Eq. (34), the TL is expressed as follows:

It should be stated that \({W}_{6n}\) represents the radial displacement of the neutral surface of the inner layer (isotropic). Additionally, NR can be defined as follows73:

To calculate NR, the inner cavity is considered as a resonant medium. Internal cavity resonances significantly influence the acoustic behavior of closed structures, such as cylinders. By thoroughly analyzing these resonances, it becomes possible to enhance noise transmission characteristics, resulting in improved sound control and overall performance of the structure. Therefore, the sound pressure in the internal cavity (\({P}_{7}^{T}\)) can be expressed in the following form:

By substituting Eqs. (28) and (39) into Eq. (38), the NR can be obtained as follows:

where \({R}_{6i}\) represents the inner shell radius (isotropic) at its inner surface.

Numerical results and discussion

In this section, we begin by validating the proposed analytical approach. For this purpose, the validation is performed by comparing our results with two studies: Magniez et al.74 and Sastry and Munjal73. Subsequently, new numerical results based on sound-structure coupling simulations are discussed. We have developed an analytical model to examine various acoustic parameters, including NR and STL. This model is versatile and can accommodate changes such as variations in layer materials and reductions in the number of layers. To demonstrate the accuracy of the proposed analytical approach, we approximated a cylindrical sandwich shell with annular and axial reinforcements as a single-layer cylindrical shell made of isotropic material. Essentially, the complex structure of the cylindrical shell with multiple layers and reinforcements has been simplified for analytical purposes. In all subsequent analyses, air is assumed as the external fluid for calculating the TL parameter, while water is considered the external fluid for calculating the NR parameter.

Initially, the results obtained from this analytical model are compared with those derived from the model by Magniez et al.74. The structure studied in their work is a single-layer isotropic cylindrical shell made of aluminum, excited by an oblique sound wave with an incidence angle of \(\psi = 45^\circ\). As shown in Fig. 5a, the comparison confirms the validity of the problem-solving procedure. Moreover, as illustrated in this figure, the three important frequencies including the ring (\({f}_{r}\)), critical (\({f}_{c}\)), and coincident (\({f}_{coin}\)), which are obtained from the analytical method, have been accurately predicted by these two models. The ring frequency is defined as the frequency at which the wavelength of a circumferential wave equals the wavelength of a longitudinal wave in the shell. In other words, at this frequency, the circumference of the shell equals the wavelength of a longitudinal wave. This frequency can be calculated as follows:

Comparison of sound transmission loss and noise reduction for a single-layer hollow cylinder subjected to an oblique plane wave between the present study and (a) Magniez et al.74, (b) Sastry and Munjal73; and (c) and (d) comparison of sound transmission loss for a double-walled shell between the present work and both the theoretical and experimental models presented by Lee and Kim69.

The critical frequency is the frequency at which the circumferential wavenumber of the shell equals the trace wave number in the radial direction. In other words, this frequency results from spatial matching in the radial direction between the wave vector due to excitation and the circumferential wavenumber of the shell. It is calculated as follows:

The coincidence frequency is related to the equality of the circumferential wavenumber of the shell and the trace wave number in the radial direction. Alternatively, it can be described as the frequency at which the phase velocity of the sound waves matches the phase velocity of the bending waves in the shell wall. It is expressed by the following relation:

Another validation is also performed for the NR parameter. The NR results of this study are compared with those obtained by Sastry and Munjal73 for a single-layer elastomer cylindrical shell with infinite length subjected to an acoustic plane wave, as illustrated in Fig. 5b. The agreement observed confirms the validation of the problem-solving procedure. The material and fluid specifications used in the simulations are provided in Table 1, and these values are applied to all simulations unless otherwise specified. Additionally, the spacing between the ring and string stiffeners is set to \({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = 50 mm, and the widths of the ring and string stiffeners are set to \({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 5 mm.

Figure 5c compares the analytical model developed in this study with both the theoretical and experimental results reported by Lee and Kim69. The verification is conducted for a double-walled shell using the dataset provided in their research. The findings reveal a strong correlation between the two analytical models, particularly in frequency regions where transmission loss decreases. However, some discrepancies exist between these theoretical predictions, which can be attributed to several factors. First, while Lee and Kim employed Classical Shell Theory in their analysis, the present study utilizes FSDT, which accounts for transverse shear deformation effects. Second, certain approximations and numerical uncertainties in Lee and Kim’s work contribute to the observed deviations. Furthermore, when both theoretical models are compared with experimental measurements, the present approach shows better agreement with the experimental data, particularly in the higher-frequency range. This improved accuracy highlights the effectiveness of the methodology adopted in this study. Nonetheless, some differences persist between the theoretical predictions and the experimental observations. These deviations can largely be attributed to the impact of boundary conditions in the experimental setup, which introduce additional sources of error. In practice, achieving an experimental configuration that perfectly simulates an infinitely long cylindrical shell is challenging, further contributing to the observed discrepancies. Figure 5d compares the analytical model developed in this study with the analytical results reported by Lee and Kim69. The verification is performed for a double-walled shell. For this validation, the polymeric foam layer was assumed to be negligibly thin, and the width and height of the ring and stringer stiffeners were set to zero. The outer layer’s radius was taken as 0.1 m, while the inner layer’s radius was 0.09 m. The thickness of both layers, as well as the air gap, was set to 1 mm. Additionally, the fluid and material properties of the shells were adopted as reported in the table provided in their paper. Our results show good agreement with those of the double-walled shell analyzed by Lee and Kim.

As seen in the previous sections, all equations are in series form. Therefore, it is essential to ensure that a sufficient number of modes are included in the analysis and to demonstrate that the solution converges. To achieve this, STL is analyzed as a function of the mode number. The mode convergence diagram at various frequencies (\(f=\) \(500\), 1000, 3000, 6000 Hz) for a periodically stiffened sandwich cylindrical shell with a polymeric foam core is shown in Fig. 6. Detailed specifications of the shells are provided in Table 1. Notably, as the frequency increases, the number of modes required for convergence also increases.

As shown in Fig. 7, the effects of spacing (\({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = 10, 25, 50 mm) between circumferential (ring) and longitudinal (string) stiffeners on STL and NR are examined. In this analysis, the widths \({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 5 mm and thicknesses \({h}_{ri}={h}_{si}\) = 1 mm of the stiffeners are considered. Adjusting the spacing between the stiffeners affects the number of rings and strings, which in turn influences structural stiffness. As the number of stiffeners increases, the overall stiffness of the structure is enhanced. Ring stiffeners function like belts, enhancing circumferential stiffness and reinforcing the structure, while string stiffeners increase bending stiffness. The figure illustrates that increased structural stiffness leads to higher STL and improved NR over a range of frequencies. This phenomenon occurs because adding ring and string stiffeners increases the stiffness and mass per unit length of the structure. Therefore, in the stiffness-controlled (\(0<f<746.8 \text{Hz}\)) and mass-controlled (\(746.8<f<5361.2 \text{Hz}\)) regions, an increase in STL and an improvement in NR can be observed. This increase in STL is especially pronounced at \(1<f<10 \text{Hz}\) and \(400<f<6000 \text{Hz}\). A common challenge in various industries is the transmission of noise at low frequencies, as long wavelengths result in greater noise penetration through the structure75. The figure shows that increasing the number of rings and strings helps alleviate this issue to some extent. For example, at a frequency of 5 Hz, reducing the distance between the rings and strings from 50 to 10 mm (increasing the number of reinforcements) results in a 6.35 dB increase in STL. Additionally, increasing the number of reinforcements causes dip frequencies to shift to higher values. Specifically, reducing the distance between the rings and strings from 50 to 10 mm raises the dip frequency from 8.25 Hz to 10 Hz. It is also observed that at frequencies above 400 Hz, reducing the distance between the rings and strings from 50 to 10 mm results in a significant increase in STL. In summary, increasing the number of stiffeners increases the structural stiffness, thereby improving STL and NR.

As shown in Fig. 8, the effects of varying the widths (\({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 1, 5, 10 mm) of ring and string stiffeners on STL and NR are examined. In this analysis, the spacings \({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = 50 mm and thicknesses \({h}_{ri}={h}_{si}\) = 1 mm of the stiffeners are considered. Changes in the widths of the stiffeners alter the stiffness and mass distribution of the structure. Increasing the width of the stiffeners raises both the overall stiffness and mass per unit length of the structure. Put simply, increasing the width of both ring and string stiffeners significantly improves circumferential and longitudinal stiffness, enhancing the structure’s resistance to vibrational energy transmission. The figure shows that the added stiffness from wider stiffeners results in higher STL and improved NR over a range of frequencies. Thus, in the stiffness-controlled (\(0<f<746.8 \text{Hz}\)) and mass-controlled (\(746.8<f<5361.2 \text{Hz}\)) regions, increases in STL and NR are observed. Similar to the effect of increasing the number of rings and strings, this rise in STL is especially pronounced in the frequency ranges \(1<f<10 \text{Hz}\) and \(400<f<6000 \text{Hz}\). At a frequency of 5 Hz, expanding the width of the rings and strings from 1 to 10 mm results in a 4.4 dB increase in STL. Additionally, an increase in the width of the stiffeners causes dip frequencies to occur at higher values. Specifically, increasing the width of the rings and strings from 1 to 10 mm raises the dip frequency from 8 to 8.75 Hz. It is also observed that at frequencies above 400 Hz, increasing the width of the stiffeners from 1 to 10 mm results in a significant increase in STL. For example, by optimizing the spacing and width of stiffeners in vehicle chassis and body panels, manufacturers can effectively reduce road noise and vibrations, leading to quieter cabin environments and improved driver comfort. Similarly, enhancing the design of stiffeners in high-speed trains can mitigate vibration and noise from the tracks, resulting in greater passenger comfort and potentially extending the lifespan of railway infrastructure.

In Fig. 9, the effects of different thicknesses (\({h}_{ri}={h}_{si}\) = 0.2, 0.6, 1 mm) of ring and string stiffeners on STL and NR are explored. The analysis includes stiffener spacings \({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = 50 mm and widths \({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 5 mm. Increasing the thickness of the stiffeners increases the structure’s overall stiffness and mass per unit length. Specifically, a greater thickness of both ring and string stiffeners significantly boosts circumferential and longitudinal stiffness, which improves the structure’s ability to resist vibrational energy transmission. As shown in Fig. 9a and b, this increased structural stiffness leads to higher STL and improved NR across a range of frequencies. A notable observation from Fig. 9a is that increasing the thickness of the stiffeners causes the dip frequencies to shift toward higher values.

Figure 10 explores the effects of different materials (steel, aluminum, and elastomer) of ring and string stiffeners on STL and NR. The analysis incorporates stiffener spacings \({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = 50 mm and widths \({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 5 mm and thicknesses \({h}_{ri}={h}_{si}\) = 1 mm. When the stiffeners are made of steel, the overall stiffness and mass per unit length of the structure increase compared to when the structure is reinforced with aluminum and elastomer stiffeners. Consequently, as expected, the reduction in sound transmission and noise is more significant in this case than in the other two scenarios. When elastomers are used as stiffeners, the reduction in sound transmission and noise is minimal in the stiffness-controlled region. However, at higher frequencies, particularly in the mass-controlled region, elastomers perform comparably to aluminum due to their superior damping properties. This high damping capacity allows elastomers to effectively reduce vibration amplitudes, enhancing their ability to dissipate sound energy as frequency increases. Although the mass of a material generally governs sound transmission in the mass-controlled region, elastomers offset this effect through their damping characteristics, making them a valuable choice for applications focused on high-frequency sound attenuation. Consequently, the balance between mass and damping properties is essential in shaping the sound transmission behavior of the reinforced cylindrical shell. At a frequency of 5 Hz, changing the material from elastomer to steel results in a 2.31 dB increase in STL. Additionally, this change leads to an increase in the dip frequency magnitude from 8 to 8.25.

The results presented in Fig. 11 analyze four configurations: Case 1, where both the inner isotropic cylinder and the outer FG cylinder are reinforced with rings and strings (\({h}_{ri}={h}_{si}\) = 1 mm, \({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = 10 mm, \({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 10 mm); Case 2, where only the outer FG cylinder is reinforced (\({h}_{r1}={h}_{s1}\) = 1 mm, \({B}_{r1}={B}_{s1}\) = 10 mm, \({D}_{r1}={D}_{s1}\) = 10 mm); Case 3, where only the inner isotropic cylinder is reinforced (\({h}_{r2}={h}_{s2}\) = 1 mm, \({B}_{r2}={B}_{s2}\) = 10 mm, \({D}_{r2}={D}_{s2}\) = 10 mm); and Case 4, where neither cylinder is reinforced (\({h}_{ri}={h}_{si}\) = \({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = \({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 0). The results show that Case 1 provides the highest STL and NR due to the enhanced stiffness and minimized vibrations from dual reinforcement. In contrast, Case 4, with no reinforcement, has the lowest STL and NR, demonstrating the importance of structural stiffening. In Fig. 11a, it is evident that, in the stiffness-controlled region, Case 3 outperforms Case 2 in vibration damping and acoustic insulation. However, in the mass-controlled region, Case 2 delivers superior performance. Examining Fig. 11b reveals that, at nearly all dimensionless frequencies, the NR in Case 2 exceeds that in Case 3. The NR is a more accurate indicator of overall noise control in practical applications, as it accounts for cavity resonance effects that significantly influence sound reduction in real-world environments. A notable observation in Fig. 11a is that dual reinforcement (Case 1) shifts the dip frequencies to higher values compared to the other cases, a favorable effect resulting from the combined enhancement of stiffness and vibration reduction. This shift in dip frequencies indicates improved acoustic insulation performance. This analysis is particularly critical for applications in the aeronautics and automotive industries, where sound insulation and vibration control are essential for operational efficiency and passenger comfort. For example, in airplane cabin design, dual-reinforced cylindrical shells can significantly reduce noise levels and enhance passenger experience.

Acoustic performance analysis of a periodically stiffened sandwich cylindrical shell with a polymeric foam core under different reinforcement configurations. (a) sound transmission loss for four cases: Case 1 (both inner and outer cylinders reinforced), Case 2 (outer FG cylinder reinforced), Case 3 (inner isotropic cylinder reinforced), and Case 4 (no reinforcement). (b) noise reduction for the same cases.

Figure 12 illustrates the impact of stiffeners on the acoustic pressure distribution inside the inner cavity of the sandwich cylindrical shell under resonance conditions at frequencies of 450 Hz, 1000 Hz, and 4000 Hz. The results are presented for both stiffened and unstiffened configurations. The comparison reveals that the inclusion of stiffeners significantly influences the pressure distribution within the cavity, demonstrating their effectiveness in altering the acoustic response of the structure. At 450 Hz, the pressure distribution exhibits localized high-intensity regions in both configurations. However, the stiffened structure shows a reduction in maximum pressure amplitude compared to the unstiffened case. This indicates that the added stiffness modifies the structural response, leading to a suppression of resonance-induced pressure amplification. At 1000 Hz, the acoustic field is characterized by concentric wavefronts, with a notable difference in pressure levels between the two configurations. The stiffened structure exhibits a significantly lower pressure amplitude, suggesting that stiffeners enhance the shell’s ability to attenuate sound waves at mid-range frequencies. The difference in pressure amplitude between the two cases is more pronounced at this frequency compared to 450 Hz. At 4000 Hz, the acoustic field exhibits intricate wave interference patterns, and the stiffened structure shows a remarkable reduction in maximum pressure amplitude. This indicates that the stiffeners remain highly effective even at high frequencies, significantly mitigating acoustic pressure. The substantial reduction in amplitude suggests that the structural reinforcement enhances the overall acoustic performance of the shell across a wide frequency range. These results demonstrate that stiffeners modify the vibrational characteristics of the shell by introducing additional constraints that alter wave propagation and reflection within the cavity. Their influence is particularly pronounced at all examined frequencies, effectively suppressing resonance-induced acoustic pressure and improving the noise control characteristics of the system. These findings underscore the importance of structural reinforcement in controlling the acoustic environment within sandwich cylindrical shells submerged in fluid media.

Effect of stiffeners on acoustic pressure inside the inner cavity under resonance conditions at 450 Hz, 1000 Hz, and 4000 Hz. Stiffened structure: \({h}_{ri}={h}_{si}\) = 1 mm, \({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = 10 mm, \({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 10 mm. Unstiffened structure: \({h}_{ri}={h}_{si}\) = \({B}_{ri}={B}_{si}\) = \({D}_{ri}={D}_{si}\) = 0.

The results presented in Fig. 13 examine the effect of the FG layer’s thickness (\({h}_{2}\)) on the acoustic performance of the sandwich structure for three thickness values: \({h}_{2}\)= 1 mm, \({h}_{2}\)= 2 mm, and \({h}_{2}\)= 3 mm. Figure 13a and b demonstrate that increasing the FG layer thickness enhances the STL and NR. Figure 13a clearly shows that increasing the thickness of the FG outer layer enhances the STL, particularly in the low to mid-frequency range (stiffness-controlled region). For example, in the frequency band from approximately 10 Hz to 200 Hz, the configuration with \({h}_{2}\) = 3 mm consistently exhibits higher STL values compared to the 1 mm and 2 mm cases. This improvement is attributed to the increased mass and stiffness introduced by the thicker FG layer, which contributes to higher acoustic impedance and more effective sound energy reflection. Several noticeable dips in STL appear in the low-frequency range, notably around 8 to 10 Hz and in the 30 to 100 Hz interval. These dips are indicative of structural resonance or coupling effects between the incident wave and the dynamic response of the shell. As the FG thickness increases, these dips shift toward lower frequencies, which suggests a reduction in the system’s natural frequencies due to the added mass and modified stiffness distribution introduced by the thicker FG layer. In the high-frequency region, particularly above 1 kHz, the STL curves become increasingly oscillatory. This behavior is characteristic of fluid-loaded, multi-layered cylindrical shells and results from complex wave interactions, such as internal reflections, interfacial scattering, and mode conversions within the layered media. Despite these fluctuations, the overall STL performance continues to improve with FG thickness, indicating that the outer graded layer remains effective in enhancing acoustic insulation even at higher frequencies.

The results presented in Fig. 14 investigate the effect of the power-law index (N) on the acoustic performance of the sandwich structure, where the FG material properties vary through the radial thickness as described in Eq. (8). Figure 14a shows that when the FG material properties are fully ceramic (N = 0), the structure achieves the highest STL, as the superior stiffness and acoustic impedance of ZrO2 minimize sound transmission. Conversely, when the FG material properties are fully metallic (N = ∞), the STL reaches its lowest value due to aluminum’s lower stiffness and density. Similarly, Fig. 14b demonstrates that the NR is also maximized for N = 0 and minimized for N = ∞. For the intermediate case (N = 1), the STL and NR lie between these two extremes, reflecting the gradual transition in material properties through the thickness.

Figure 15 illustrates the influence of the edge material coefficient (\(\phi\)) on wave propagation in a sandwich cylindrical shell with a polymeric foam core. The values \(\phi\) = 0.5 and \(\phi\) = 1 represent closed-cell and open-cell foam structures, respectively. As \(\phi\) increases, the foam transitions from a predominantly closed-cell configuration to a fully open-cell structure. At low frequencies (Fig. 15a), the closed-cell foam demonstrates higher STL compared to the open-cell foam. This behavior is attributed to the stiffer and more enclosed structure of closed-cell foams, which provides better impedance mismatch and thus more effectively blocks low-frequency sound transmission. In contrast, at higher frequencies, the open-cell foam exhibits superior STL performance. This enhancement is due to the structural characteristics of the open-cell configuration, where interconnected pores and reduced stiffness facilitate internal mechanical damping. The open-cell network enables localized deformation and vibration of the foam structure, which dissipates acoustic energy through microstructural vibration modes and frictional losses within the material’s internal structure. These micro-vibrations act as distributed damping mechanisms, particularly effective at attenuating high-frequency acoustic waves. Figure 15b further shows that the choice between closed-cell and open-cell foam has minimal effect on NR at low dimensionless frequencies. However, the open-cell foam achieves noticeably improved NR performance at higher frequencies. This is again due to the foam’s ability to engage more effectively with high-frequency structural vibrations, leading to greater energy dissipation. These results emphasize that open-cell foams enhance high-frequency noise reduction by promoting internal structural vibration dissipation mechanisms, which are less active in closed-cell configurations. Therefore, selecting open-cell foam in multilayer sandwich designs is advantageous when high-frequency acoustic attenuation is a primary design objective.

In this study, the parameter g in the power-law distribution function (r) (as defined in Eq. (16)) significantly influences the variation of mechanical properties through the thickness of polymeric foam materials. When g = 0, the foam distribution is uniform, resulting in the highest values of Young’s modulus and density. As shown in Fig. 16a, g has a negligible effect on TL at frequencies below 6.5 Hz. However, at frequencies above this threshold, an increase in g leads to a decrease in TL across most frequencies. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 16b, g has little impact on NR up to a dimensionless frequency of 12. Beyond this point, increasing g generally results in a reduction of NR across most dimensionless frequencies. As g increases, the overall stiffness and density of the foam material decrease, directly impacting its mechanical performance. This reduction in stiffness and density leads to lower values of NR and STL across most frequency ranges, as illustrated in Fig. 16. Additionally, Fig. 17 demonstrates the effect of minimal relative density (\(\alpha\)) on STL and NR in a sandwich shell with a polymeric foam core, for \(\alpha\) values of 0.05, 0.45, and 0.85. As shown in Fig. 17a, \(\alpha\) has little impact on STL at frequencies below 8 Hz. However, above this frequency, an increase in \(\alpha\) results in a rise in STL across most of the frequency range. Similarly, Fig. 17b indicates that \(\alpha\) does not significantly affect NR up to a dimensionless frequency of 12. After this point, increasing \(\alpha\) generally leads to higher NR values across the majority of dimensionless frequencies. The increase in \(\alpha\) leads to greater stiffness and density of the foam material, which directly influences its mechanical performance.

The results presented in Fig. 18 investigate the influence of foam thickness (\({h}_{4}\)) on the acoustic performance of the sandwich cylindrical shell, where the foam is assumed to be open-cell. Figure 18a shows that increasing foam thickness leads to higher STL in both the stiffness-controlled and mass-controlled regions, demonstrating that thicker open-cell foam enhances sound insulation across these frequency ranges. This improvement is attributed to the larger volume of foam, which increases the path length for sound waves and enhances sound dissipation. Additionally, the thicker foam increases the overall stiffness and weight of the structure, which influences both its acoustic response and mechanical behavior under dynamic conditions. Figure 18b reveals a similar trend for NR, where thicker foam layers result in greater NR at dimensionless frequencies above 2.5. The effect of foam layer thickness becomes more apparent at these higher frequencies due to the foam’s ability to absorb and dissipate sound energy through internal friction, which is more effective at higher frequencies where sound waves interact more significantly with the foam’s cellular structure. These findings highlight the importance of selecting an appropriate foam thickness to optimize the acoustic insulation of sandwich cylindrical shells with open-cell foam for specific applications, particularly those requiring high sound attenuation while considering the mechanical performance of the structure.

Figure 19 presents the influence of polymeric foam thickness on the acoustic pressure inside the inner cavity of the sandwich cylindrical shell under resonance conditions at three distinct frequencies: 450 Hz, 1000 Hz, and 4000 Hz. The results indicate that increasing the thickness of the polymeric foam core significantly alters the acoustic response of the structure, particularly in terms of pressure attenuation. At 450 Hz, the pressure distribution for the thin polymeric foam configuration exhibits high-intensity localized regions. When the foam thickness increases to 3 cm, a noticeable reduction in maximum pressure amplitude is observed. The presence of a thicker foam layer appears to enhance energy dissipation, effectively reducing the acoustic pressure within the cavity. At 1000 Hz, the acoustic field is characterized by concentric wavefronts in both configurations. The thick polymeric foam results in a substantial decrease in the overall pressure amplitude compared to the thin foam case. This suggests that the increased thickness of the foam core enhances its ability to absorb and dissipate acoustic energy, leading to improved noise reduction within the cavity. At 4000 Hz, the acoustic field exhibits intricate wave patterns due to the higher frequency of excitation. The comparison between the two configurations reveals a dramatic reduction in the maximum pressure amplitude when the polymeric foam thickness is increased. The maximum amplitude decreases from approximately 3e−5 for the thin foam case to below 9e−7 for the thick foam case, demonstrating the effectiveness of a thicker polymeric foam layer in mitigating high-frequency acoustic pressure. These findings suggest that increasing the thickness of the polymeric foam core plays a critical role in controlling the acoustic environment inside the cylindrical shell. The enhanced energy dissipation and wave attenuation capabilities of a thicker foam layer lead to a significant reduction in acoustic pressure across all examined frequencies. This highlights the importance of optimizing the foam thickness in sandwich cylindrical shells to achieve superior noise reduction performance in submerged structures.

To investigate the influence of external mean flow on the acoustic performance of the sandwich structure, the Mach number is used as the control parameter. Figure 20a and b illustrate the variations in STL and NR with respect to frequency at two Mach numbers: \({M}_{1}\) = 0 (no flow) and \({M}_{1}\) = 0.6 (subsonic flow). In Fig. 20a, below the ring frequency (stiffness-controlled region), the STL exhibits a decreasing trend with some fluctuations when the Mach number increases from \({M}_{1}\) = 0 to \({M}_{1}\) = 0.6. This behavior is consistent with the findings of Sgard et al.76, who noted that the presence of mean flow introduces negative stiffness effects and radiation damping, leading to a reduction in sound insulation capability. These phenomena arise due to the additional aerodynamic forces acting on the structure, which alter its vibrational characteristics and radiative properties. In the mass-controlled region, however, the influence of the external flow is reversed, as shown by a modest increase in STL with increasing Mach number. This improvement can be attributed to the additional inertia effect introduced by the flowing air, which enhances the resistance to sound wave transmission through the structure. The results demonstrate the dual impact of external flow, where it degrades STL in the stiffness-controlled region but slightly enhances it in the mass-controlled region. Figure 20b further highlights the effect of external flow on NR. Across almost all dimensionless frequencies examined, the NR parameter increases with rising Mach numbers. This enhancement is likely due to the interaction between the structure’s vibration modes and the aerodynamic damping introduced by the mean flow, which dissipates more energy and suppresses noise transmission. The results suggest that at higher Mach numbers, the dynamic interaction between the external flow and the sandwich structure improves its overall noise reduction performance. These findings underscore the importance of considering mean flow effects in the design of structures exposed to aerodynamic environments, as they significantly influence both STL and NR, particularly in stiffness- and mass-controlled frequency regions.

Figure 21 presents the influence of the Mach number on the acoustic pressure distribution inside the inner cavity of the sandwich cylindrical shell at three resonance frequencies. The comparison is made between a stationary medium (\({M}_{1}\) = 0) and a moving medium with a flow velocity corresponding to \({M}_{1}\) = 0.6. The results highlight the impact of uniform flow on the acoustic response, particularly in modifying the pressure distribution and intensity. At 450 Hz, when the Mach number increases from \({M}_{1}\) = 0 to \({M}_{1}\) = 0.6, a noticeable increase in the maximum pressure amplitude is observed. The pressure field remains concentrated in localized regions, but the intensity grows significantly in the presence of flow. This suggests that fluid motion enhances the resonance effects at lower frequencies, leading to stronger acoustic responses. At 1000 Hz, the acoustic field retains its characteristic concentric wavefronts. However, in the \({M}_{1}\) = 0.6 case, the pressure levels are generally higher than in the stationary medium. The presence of flow appears to reinforce the standing wave patterns inside the cavity, amplifying the pressure amplitudes. At 4000 Hz, the interaction between the acoustic waves and the flow becomes more complex, resulting in a shift in the pressure distribution. While the overall structure of the wavefronts remains similar between \({M}_{1}\) = 0 and \({M}_{1}\) = 0.6, the pressure amplitude increases noticeably in the moving medium. The maximum amplitude rises from approximately 3e−5 in the stationary case to 6e-5 in the flow case, demonstrating the amplifying effect of the Mach number at higher frequencies. These results indicate that increasing the Mach number intensifies the acoustic pressure inside the cavity across all examined frequencies. The flow-induced amplification of pressure suggests that the interaction between the moving fluid and the acoustic field plays a significant role in modifying resonance conditions. This highlights the importance of considering the effects of uniform flow when analyzing submerged structures exposed to acoustic excitations.

Conclusions and perspective

This study presents a novel analytical framework for evaluating the noise reduction performance of periodically stiffened sandwich cylindrical shells, specifically addressing the gap in understanding their behavior under fluid–structure–acoustic interaction. By integrating the FSDT with the Zener viscoelastic model and employing Hamilton’s principle, the work systematically derives and solves the governing equations for an infinitely long shell composed of an FG outer layer, a viscoelastic polymeric foam core, and an isotropic inner layer. The influence of ring and string stiffeners, along with core foam type (open-cell vs. closed-cell), is thoroughly investigated to quantify key acoustic metrics, namely STL and NR. Unlike previous studies focused on flat or unstiffened configurations, this work captures the combined effects of reinforcement configuration, foam architecture, and frequency-dependent damping, revealing optimal design strategies for enhancing acoustic insulation across a broad frequency range.

This study is based on a set of simplifying assumptions that enable analytical tractability but introduce certain limitations. The surrounding medium is modeled as an ideal, inviscid fluid, neglecting viscous and thermal dissipation effects. Acoustic excitation is assumed to be an obliquely incident plane wave, excluding complex wavefronts encountered in practical environments. The fluid domain is assumed to be infinite. A steady, uniform subsonic flow is assumed, without accounting for turbulence or boundary layer effects. The viscoelastic core behavior is represented using the Zener model, which captures frequency-dependent damping but neglects nonlinearities such as amplitude dependence and thermal sensitivity. The shell is considered infinitely long, thereby disregarding edge reflections and finite-length effects. A summary of the most important results is as follows:

-

Effect of stiffener design parameters

Increasing the number of ring and string stiffeners significantly enhances structural stiffness, leading to improved STL and NR, particularly at low frequencies where noise penetration poses significant challenges. For instance, increasing the number of stiffeners resulted in a 6.35 dB improvement in STL and shifted dip frequencies to higher values, indicating enhanced acoustic insulation. Similarly, modifying the width and thickness of stiffeners also contributed to higher stiffness and mass per unit length, further improving STL and NR performance.

-

Material composition of stiffeners

The choice of stiffener material impacts acoustic performance significantly. Steel stiffeners, due to their higher stiffness and mass, provided the greatest reduction in sound transmission and noise. Elastomers showed minimal impact in the stiffness-controlled region but performed comparably to aluminum at higher frequencies in the mass-controlled region, thanks to their superior damping properties. This damping allowed elastomers to reduce vibration amplitudes and dissipate sound energy effectively. At 5 Hz, replacing elastomers with steel increased STL by 2.31 dB and slightly raised the dip frequency magnitude from 8 to 8.25.

-

Influence of core foam properties

The polymeric foam core’s characteristics, including thickness, cell type (open-cell vs. closed-cell), and material distribution parameters, played a pivotal role in sound energy dissipation and acoustic performance. Thicker foam layers provided enhanced STL and NR by increasing the path length for sound waves and improving overall structural stability. Open-cell foam was particularly effective at higher frequencies due to its ability to dissipate sound energy through internal friction, while closed-cell foam exhibited better performance at lower frequencies because of its denser structure, which improved stiffness. Additionally, the distribution parameter g, governing the variation of mechanical properties within the foam, significantly influenced its acoustic behavior. At higher values of g, the foam’s stiffness and density decreased, leading to lower STL and NR across most frequencies. Conversely, lower values of g produced a denser and stiffer foam, yielding improved acoustic performance. Similarly, the relative density parameter α, which defines the foam’s minimum density, demonstrated its importance in acoustic performance. As α increased, both STL and NR improved, particularly at higher frequencies, due to the enhanced stiffness and mass per unit volume of the foam core. These findings highlight the critical role of carefully selecting and optimizing foam parameters such as thickness, g, and α to achieve desired acoustic insulation levels while maintaining structural performance. Such adaptability makes the proposed design suitable for a wide range of industrial applications.

-

Impact of functionally graded materials

The FG outer layer demonstrated remarkable potential for tailoring acoustic performance. When the material composition transitioned from metallic to ceramic, STL and NR improved significantly due to the higher stiffness and impedance of ceramics. Increasing the thickness of the FG layer further amplified these benefits, particularly in the stiffness-controlled frequency region.

-

Reinforcement configurations

Dual reinforcement of the inner isotropic and outer FG layers provided the highest STL and NR, effectively minimizing vibrations and enhancing noise insulation. This configuration also shifted dip frequencies to higher values, highlighting its efficiency in addressing noise transmission challenges in industrial applications.

-

External factors

The presence of external mean flow (represented by Mach number) influenced acoustic performance. At low frequencies, external flow reduced STL due to aerodynamic damping effects, while at higher frequencies, STL slightly improved due to increased inertia. NR consistently improved with rising Mach numbers, demonstrating the system’s potential for environments with fluid-structure interaction.

This research offers practical solutions for industries where noise reduction and vibration control are critical. The proposed sandwich cylindrical shells, reinforced with ring and string stiffeners and filled with polymeric foam, provide excellent acoustic insulation and structural stability. These features make the design ideal for applications such as high-speed train fuselages, where the reinforcement reduces noise and vibrations, creating quieter and more comfortable cabins. In the automotive industry, the integration of polymeric foam and reinforcements can be applied to vehicle panels and chassis, effectively reducing road noise and vibrations for a more comfortable driving experience. High-speed trains can also benefit from this design, as it mitigates noise and vibrations from tracks, ensuring passenger comfort and extending the lifespan of train components.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [AT], upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \({c}_{1}\) :

-

Speed of sound in the external fluid

- \({c}_{3}\) :

-

Speed of sound in the outer air gap

- \({c}_{5}\) :

-

Speed of sound in the inner air gap

- \({c}_{7}\) :

-

Speed of sound in the internal fluid

- \(E\) :

-

Elastic modulus

- \({f}_{c}\) :

-

Shear correction factor

- \(G\) :

-

Shear modulus

- \({G}_{4},{G}_{\text{4,1}}\) :

-

Shear moduli of the polymeric foam

- \({h}_{2}\) :

-

Thickness of the outer FG layer

- \({h}_{4}\) :

-

Thickness of the polymeric foam core

- \({h}_{6}\) :

-

Thickness of the inner isotropic layer

- \({M}_{ij}\) :

-

Bending moment resultants

- \({N}_{ij}\) :

-

Membrane (force) resultants

- \({Q}_{ij}\) :

-

Transverse shear force resultants

- \({R}_{2}\) :

-

Radius to the center of the outer FG layer

- \({R}_{6}\) :

-

Radius to the center of the inner isotropic layer

- \({R}_{\text{in}}\) :

-

Internal radius of the cylindrical shell

- \({R}_{\text{ex}}\) :

-

External radius of the cylindrical shell

- t :

-

Time

- T :

-

Total relaxation time constant