Abstract

We modified the original statistical-physical hydraulic conductivity model proposed by Usowicz, based on averaging water flow through soil pores as a net of capillary tubes. Three division zones of the retention curve were distinguished, and five capillaries with medium radii were assigned: one capillary in both the boundary effect zone and the residual zone, and three capillaries in the transition zone. The sixth capillary covered the entire retention curve with a constant radius up to the residual zone, where the radius decreased to the minimum value with decreasing water content. The equivalent capillary lengths were determined from the measured saturated hydraulic conductivity values under the drying process and the number of parallel capillary connections from those under the wetting. The sixth capillary is responsible for flow processes through vapor and water films. This approach allowed the prediction of unsaturated hydraulic conductivity at a full range of water content. The model was validated using measured data of variously textured soils with different compaction and disturbance. The statistical parameters showed good agreement between the measured and model-predicted data. Further studies are intended to improve the model predictability of the hydraulic conductivity by including an additional domain for preferential water flow through macropores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Data on hydraulic conductivity govern water flow and use. Unsaturated hydraulic conductivity depends on the amount of water in the soil. Therefore, it is commonly expressed as a function of matric suction or volumetric water content1 and can vary in some orders of magnitude depending on the soil water status and the soil type2,3.

Reliable estimation of unsaturated soil hydraulic properties is crucial for addressing the rate at which water infiltrates soil water and moves to plant roots4,5,6, soil-atmosphere exchange7,8,9, designing capillary barriers10, estimations of slope stability under rainfall, and crop yield11. The unsaturated soil hydraulic properties help manage contaminant transport in vadose soil and other variably saturated flow systems12,13,14. The utility of these properties is highlighted by the fact that the majority of natural soils are predominantly unsaturated15,16,17.

Soil water retention and hydraulic conductivity curves for given soils are not unique. They exhibit different behaviors during the drying (desorption) and wetting (sorption) processes18, known as a hysteretic effect. A significant cause of hysteresis is the “ink-bottle effect” caused by pore structure heterogeneity19,20. This effect occurs because the matric suction value at filling of a given void with water during wetting is linked with the void radius, while the matric suction at water emptying during drying increases and is linked with the smaller radius of a narrow throat giving entry of air to the same void20,21. Then, water content and hydraulic conductivity can be higher during the drying than wetting process when plotted with matric suction. Other sources of hydraulic hysteresis include different contact angles, air entrapment, capillary condensation, and soil swelling and shrinking during drying and wetting2,22. The hysteretic hydraulic properties impact transient soil water flow processes and water redistribution processes, particularly at capillary tubes with smaller pore throats23 and low degrees of saturation with water when the soil pores contain mostly air and liquid soil water in the form of meniscus water bridges and thin liquid films around soil particles10,24,25. Though the hysteresis effect in the hydraulic conductivity–matric suction relationship is notable, it is generally considered negligible (e.g.,26). The hysteresis effect also influences other soil functions, including heat transfer27 and gas diffusion28,29.

In deformable soils, a vital factor besides matric suction influencing unsaturated hydraulic conductivity is the soil compaction level, the degree of soil disturbance (remolding), the hydro-mechanical properties of soils30,31, and pore connectivity17 induced by soil management practices. Associated alterations in matric suction and the volume and pore size and structure of soil, including the formation of ink-bottle pores, will affect unsaturated hydraulic conductivity differently along the drying and wetting paths. Recent results indicate that, in the case of continuous ink-bottle pores, the volumetric deformation during compaction mainly reduces the pore regions with a larger cross-sectional area designated as the pore body and much less those with a smaller cross-sectional area as the pore throat32. Such pore structure modification can result in a more apparent hysteresis effect. Despite their significance, the effects of soil compaction and disturbance on hysteretic hydraulic properties remain poorly understood17.

The direct field measurement of unsaturated hydraulic conductivity is difficult, as it involves water flow and changes in water content which alter matric suction and, ultimately, conductivity33,34. Therefore, there is a need for alternative predictive methods. Several prediction models for estimation of the hydraulic conductivity using a variety of statistical pore size distribution models, such as those developed by Burdine35 and Mualem36 have been used during the last decades to describe capillary conductivity that is not influenced by surface forces. They usually embrace retention regions between saturation and residual water content. Most capillary-based functions disregard the contribution of water stored and migrating in the soil through the adsorptive water film that dominates at a lower degree of soil saturation below residual water content and thus a higher matric suction range25,37,38. Only a few hydraulic models consider capillary and adsorption (non-capillary) water components. The recently developed modelling framework of Peters-Durner-Iden (PDI)39 predicts vapor, noncapillary, and capillary liquid conductivity as absolute values based on four retention curve parameters. This model accounts for an important characteristic, namely water path elongation due to pore tortuosity, pore wall surface roughness, and other factors, to efficiently parametrize the hydraulic conductivity curve across the soil water content spectrum. In the approach proposed by Lebeau and Konrad40, a statistically based model was used to determine the unsaturated conductivity of the water-filled capillaries, whereas a theoretical model—to predict the conductivity of the adsorbed water. Wen et al.34 proposed estimating the water permeability of unsaturated soil using only one parameter obtained by permeability tests of saturated soil with different porosities. Significance of these conceptual features in parametrizing soil hydraulic conductivity over the whole range of water status is comprehensively overviewed in Peters et al.41. So far, the modelling approaches were generally confined to the drying path42,43, and did not adequately address the hysteresis phenomena.

Therefore, in this paper, a modified statistical-physical model is proposed for the estimation of the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soil during drying and wetting processes for domains of capillary water and also for those of film water and water vapor below residual water content. To test and validate the model, we used the experimental data of Wayllace and Lu44 and Gallage et al.45, including water retention and hydraulic conductivity in saturated and unsaturated states during the processes of drying and wetting of various textured soils with different compaction levels and degrees of soil disturbance.

Statistical-physical model of hydraulic conductivity of soil

The soil hydraulic conductivity was evaluated using the statistical-physical model of soil conductivity developed by Usowicz46,47 and Usowicz et al.48.

Any system/medium within which there is a differentiated physical (scalar) field shows a tendency to reach a state of equilibrium (Fig. 1).

This is manifested by the flow of mass and energy from places with higher potential to areas with lower potential. As a result of this flow, the scalar field in the entire medium is equalized. Inside a system with a temperature gradient—∂ T/∂z or a pressure gradient—∂p/∂z, (p = ψ ·ρw, ψ—the potential of water in the medium, ρw—the density of water, the gradient of electric potential, ∂V/∂z, or the gradient of the concentration of the substance ∂c/∂z (Fig. a), each of these systems will tend to equilibrium. The laminar flow of liquids and gases (without mass turbulence) is described by the Darcy equation. A stimulus for this flow is pressure p. When concentration c is the stimulus, the flow is described by the Fick equation, whereas the Fourier equation is used when temperature is the stimulus. In turn, the Ohm equation or the Gauss equation relating the electric field to the electric charge describes the flow when voltage is its stimulus. For liquids, the average density of the flow stream qψ is proportional to the pressure gradient:

K is the specific liquid conductivity, also called the hydraulic conductivity coefficient. The stream of liquid Qψ flowing in the system is obtained by integrating the flow density over the cross-sectional area A:

Water flow in a porous medium

A simple principle called Darcy’s law describes the liquid flow in a porous medium. It states that the volumetric flow rate per unit area is proportional to the potential drop and reflects the resistance of the system to the water flow:

where Qψ is the volumetric flow rate, K is the hydraulic conductivity, the potential drop across the layer, A—is the area of the layer, l is its thickness, and R—is resistivity. An idealized model of the flow of a liquid in a porous medium is the Hagen-Poiseuille equation describing the laminar and stationary flow of a liquid through a simple capillary with a circular cross-section. The volume of the liquid that flows through a capillary tube with radius r and length l at time t is calculated from a formula that is connected with other properties of the system by the relation:

where r is the radius of the capillary, g is the acceleration due to gravity, and η is the liquid viscosity. This equation retains its structure for a Reynolds number of no more than 4. The last condition is met with the dispersion flow of a liquid in a porous medium.

It can be assumed that the porous medium will be mapped by a system (network) of more or less cylindrical connected channels. Capillary radius r can represent the elementary capillary formed between the soil particles and the average hydrodynamic radius relating to the entire system:

which is proportional to the space volume of the medium divided by the area size. Substituting this radius into the Hagen-Poiseuille equation leads to the Kozeny–Carman equation:

where k' and k—proportionality coefficients, the latter depends on the structure of the soil (e.g. on the tortuosity of channels), ϕ is the porosity, So is the specific surface area of the particles of the porous medium, i.e. their total area divided by their total volume, K'—the permeability of the medium. The k-factor and the magnitudes in parentheses in the Kozeny–Carman equation indicate that the liquid flow is determined by the nature of the porous network.

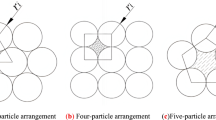

Looking at the porous medium as a network of connected capillaries allows the use of a statistical approach to describe the flow of liquids in a porous medium. The modified model uses the terms hydraulic resistance (Ohm’s law and Darcy’s law), two Kirchhoff’s laws, and multinomial distribution. Soil particles of different shapes and sizes, and pores between them, are characterized by a net of more or less cylindrically connected channels with various capillary radii. The connection points in the shape of spheres connect the capillaries horizontally and vertically. Soil particles and their configuration are pivotal for the pore distribution and the course of the water retention curve in soil. The statistical-physical model includes the pore space (Fig. 2a) as the capillary net (Fig. 2b) that is represented by parallel and serial connections of hydraulic resistors in the layer and between the layers (Fig. 2c), respectively.

Hydraulic resistance is an analog of electrical resistance described by Ohm’s law. When a system of resistors is connected in parallel, the total resistance is determined based on Kirchhoff’s first law. When a system of resistors is connected in series, we use Kirchhoff’s second law. Assuming that there are parallel connections in the u layer and that the system has n such layers that are connected in series, it is possible to calculate the resultant hydraulic resistance R of the entire system (Fig. 2c). The resistance of the layer is:

Summing up the resistances of individual layers according to Kirchhoff’s second law, we obtain the equivalent resistance for the whole system:

A porous medium consists of a solid phase, and its configuration determines the distribution of pores that affect the course of the water retention curve of the medium. The retention curve is an essential characteristic used in a statistical-physical model. It is known from the literature that the configuration of the solid phase is determined by the granulometric distribution, the content of organic matter, and the packing structure of particles (bulk density); therefore, these properties will determine the liquid flow in the medium. The influence of the density of the medium on the course of the water retention curve is vital and is conditioned by the type of porous medium and its specific surface area.

Description of the statistical-physical model of hydraulic conductivity

The statistical-physical model of hydraulic conductivity, in which the flow through the capillary system occurs in the layer, will be represented by parallel connections of hydraulic resistors and between layered connections of capillaries by series connections of resistors (Fig. 2 b, c). The hydraulic conductivity of the elementary capillary in the network was determined from the Hagen-Poiseuille equation:

On the other hand, the hydraulic conductivity of the entire porous medium was expressed by the mean hydrodynamic radius:

Substituting the above equations into the equation for total resistivity, the following expression is obtained:

Assuming that A corresponds to u, the mean areas πr2 and Aij equals πrij2, while at length l there are n unit connections, and after substituting them the following equation is obtained:

and after shortening

By rooting the above equation, we obtain the equation for the mean hydrodynamic radius squared:

Substituting r2 again into the equation for K with the mean hydrodynamic radius, the following equation is obtained:

Denoting the expression given below by means of aj:

Summing up aj, after j, we get the mean value:

\(\overline{a}\)—denotes the average value of aj.

The soil consists of various minerals, substances, and organic matter around which different-sized pores are formed in a specific unit of soil volume. Many similar pores, which are represented by capillaries, can be found. Assuming that in a unit volume of soil, there are x1 capillaries with radius r1, and length l1, x2 capillaries with radius r2 and length l2, etc., with the total number of capillaries being x1 + x2 + … + xk = u. Substituting the individual capillaries expressed by \(\frac{{r}_{ij}^{4}}{{l}_{ij}}\) in aj, we obtain:

With the pore distribution unchanged, the value \(\overline{a}\) will depend on the water content per unit volume of soil—θv, total porosity of the soil—ϕ, soil temperature—T, capillary radius—ri, the number of individual capillaries entering a given configuration—xi and the number of parallel connections between capillaries regarded as hydraulic resistors—u: thereby, the average hydraulic conductivity can be expressed by:

Since it is not possible to experimentally determine the distribution of capillaries in the tested soil, and thus the mean value \(\overline{a}\left( {\theta_{v} ,\phi ,T,r_{i} ,x_{i} } \right)\), this mean value can be replaced by the expected theoretical value \(\overline{m}\left( {\theta_{v} ,\phi ,T,r_{i} ,x_{i} } \right)\), which takes into account all possible capillary configurations and the probability of their occurrence:

The expected value is calculated from the general formula:\(\overline{m}\)

Substituting the expected value into the equation, the general form of the equation for the hydraulic conductivity of the medium is obtained:

where L is the number of all possible combinations of capillary arrangement, x1, x2 ,…, xk—the number of capillaries formed between the particles of the medium with capillary radii r1, r2 ,…, rk and lengths l1, l2,…, lk, where: \({\sum }_{i=1}^{k}{x}_{ij}=u\), j = 1.2,…,L, P(xij)—probability of occurrence of a given capillary configuration. The following condition must also be met: \({\sum }_{j=1}^{L}P\left(X={x}_{j}\right)=1\).

The probability of a given capillary configuration can be calculated from the multinomial distribution \(P\left({x}_{1j},\cdots ,{x}_{kj}\right)\):

where fi, i = 1, 2,…, k are the probabilities of capillary drawing in a single sample, which were determined based on the physical properties of the soil, i.e. retention curve and porosity.

Water flows in the soil during the drying and wetting processes

Depending on the flow direction in the soil, the free spaces between solid particles will be drained or wetted with water. The geometric distribution of the spaces in the soil determines the pore size distribution. If there is no change in the soil volume, the pore size distribution does not change, regardless of the drying or wetting process. This fact should be considered when modeling hydraulic conductivity in the soil. In the statistical-physical approach, the pore distribution is mapped by a network of connected capillaries and the probability of occurrence of a given configuration, including finding a specific capillary in a single sample. This means that the capillary radii and the water contents from the soil water retention curve during the drying or wetting processes will correspond to the given matric suction, and the water content will be related to the total porosity. On the other hand, the pore radii and the water contents during both drying and wetting will have a similar structure.

In the case of water-saturated soil, all or almost all free spaces are filled with water, while in the case of a complete lack of water, the entire space is filled with air. Each soil has its own/specific distribution of space that can be described by e.g. soil water retention curve, mercury intrusion porosimetry, and adsorption and desorption isotherms over a range of pore radii49.

The different course of the soil water retention curve during drying and wetting is mainly due to the diverse so-called "ink-bottle effect" and “raindrop” effects that describe how water behaves in soils, and they both include matric suction, pore radii, and contact angles. The pore distribution can be represented by a network of interconnected capillaries, each with a specific radius, length, and volume. In the presented statistical-physical model, the soil drying process begins with the state in which all capillaries are filled with water and the air volume is zero. Water loss, whether through evaporation, infiltration, or lateral flows in soil, will occur in areas where water is most weakly bound, i.e., in large pores. The water loss from the soil will be reflected in a decrease in the volume of water in the largest capillary. Consequently, the probability of finding water in this capillary in a single sample will decrease, and that of a capillary with air will increase. The remaining capillaries are still filled with water, and their probabilities of being found in a single sample equal the water contents in these capillaries. Further water loss from the next capillary will reduce the likelihood of finding a capillary from this area in a single sample. As in the first area, the total water loss in the second area will result in zero probability. However, the air volume will increase; thus, the likelihood of finding a capillary with air will increase. This procedure will be repeated in the following areas for the remaining capillaries. The course of the retention curve during wetting will be different from that during the drying process. If the capillary radii during wetting were the same as when drying the soil, the probabilities of finding individual capillaries in a single sample would be different. This is because selected capillary radii on the drying retention curve go to other areas of the retention curve during wetting. As a general rule, with the same soil water content, the matric suction will be higher during soil drying than during wetting. Re-selection of capillary radii and water volumes that are similar in water retention curves derived during the wetting and drying processes should be considered to ensure their optimal distribution.

In soils with large free spaces and holes, e.g., left by roots and earthworms or resulting from the swelling and shrinkage of soil and roots, a preferential water flow during intensive rain may occur. In the statistical-physical model, this flow will be considered in intended studies by involving the radius and volume of the first largest capillary. The input data for preferential flow calculations can be derived from measurements or estimated with other indirect methods, e.g., image analysis of thin sections and computed tomography. Recent explorations using X-ray computed tomography (CT) helped to elucidate the relationship between three-dimensional pore/throat radii and CT-connected porosity and hydraulic properties (e.g.,50).

Taking into account the large free spaces (rpf—radius of the capillary and fpf—volumetric content of water in the preferential flow pf) for the preferential flow and the volume of the first capillary (r1—capillary radius from the retention curve), the equivalent radius of the capillary—req from these two areas can be calculated from the geometric mean: \({r}_{eq}={r}_{pf}^{{f}_{pf}}{r}_{1}^{1-{f}_{pf}}\). Furthermore, the sixth air capillary responsible for the flow through the water vapor path, water films, and salt concentration can be determined empirically or as a geometric mean of capillaries.

Materials and methods

The experimental data on water retention and hydraulic conductivity in saturated and unsaturated states during the processes of drying and wetting for calculations from the statistical-physical model of hydraulic conductivity of soils were derived from two publications44,45. Gallage et al.45 examined two sandy soils with different bulk densities, Edosaki and Chiba soils. The Edosaki soil (sand content 83.6% and finer particles 16.4%) was extracted from a natural slope in Ibaraki, Japan, and the Chiba soil (sand content 64.0% and finer particles 36.0%) was collected from a railway embankment in Chiba Prefecture, Japan. The two soils analyzed by Wayllace and Lu44 are Remolded Sandy Colluvium obtained from Vashon Advance Outwash sand collected from a coastal cliff near Edmonds, WA, and Remolded Silty Clay and Undisturbed Silty Clay from a side of a hillside prone to landslides near the San Francisco Bay Region in California. Soil water contents with different values of soil matric suction expressed in the water column height were calculated from the van Genuchten equation with the parameters given in these publications. From the Young–Laplace equation, equivalent capillary radii were calculated for selected heights \({r}_{i}=1491.3/h\) where h—the water column height in cm of H2O. Values of saturated and unsaturated hydraulic conductivities were used to test and validate the statistical-physical model. The input data to the statistical-physical model of hydraulic conductivity included soil water contents at different matric suctions. The suction range responsible for the water flow by hydraulic conduction was divided into several sub-areas (i). They differed depending on the drying or wetting process. The average radii of capillaries, ri,, and water content, Δθi, were calculated. The sixth air capillary (i + 1) is responsible for the water conductivity by vapor, water films, and other flow processes on soil solids. They can have a constant radius to a certain limit water content and a variable below the limit (residual) water content. For this work, it was assumed that, at the point of residual water content, the radius of the sixth air capillary (i + 1) corresponds to four times the matric suction value at residual water content. The radius of the sixth air capillary changes exponentially or linearly with the change in water content: (\({r}_{i+1}\left(\theta \right)=a{\bullet e}^{b\bullet \theta }{r}_{i+1}\left(\theta \right)=a\cdot \theta +b\) θ); a and b are the parameters of the equation. According to the assumption, the value of the sixth air capillary radius was constant up to the beginning residual zone (i + 1) and decreased with the soil water content in the residual zone. Consequently, the water flow by the vapor path will decrease, but will increase through the water films on the solid particles of the soil and other processes. Such an approach is a compromise between the sixth air capillary adopted in the statistical-physical model as a network of capillaries connected in parallel and series, and flow processes in the liquid and gas phases. The common factor that connects water flows in various processes on particle surfaces, between pores, and water vapor is the soil water potential, which reflects the individual processes and can be linked to the capillary size. This simplification results from the nature of the model, and finding a rigorous mathematical justification and incorporating it into the model needs further research.

Saturated and unsaturated hydraulic conductivity data in the drying and wetting processes

The measured data of hydraulic conductivity in the drying and wetting processes used to verify the statistical-physical model came from the same two publications44,45. In the first publication, Edosaki and Chiba soils with two bulk densities and measured saturated and unsaturated hydraulic conductivities were used to determine the equivalent length (l) and number (u) of capillaries. In the second publication, saturated hydraulic conductivity during the processes of drying and wetting was used to determine the equivalent length of capillaries and the number of parallel capillary connections for the following soils: a) Remolded Sandy Colluvium, b) Remolded Silty Clay, and c) Undisturbed Silty Clay. The measured unsaturated hydraulic conductivities were compared with the model-predicted values to assess the data compliance.

The differences between the measured and calculated hydraulic conductivities were evaluated based on root mean square residuals (RMSE) and maximum relative error (MRE). They were calculated as: \(\text{RMSE}=\sqrt{\frac{{\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{\left({f}_{mi}-{f}_{ci}\right)}^{2}}{k}}\), \(\text{MRE}=\underset{i=\text{1,2},\cdots ,n}{max}\left\{\left|\frac{{f}_{mi}-{f}_{ci}}{{f}_{mi}}\right|\cdot 100\%\right\},\) where fmi is the measured data, fci is the calculated data, k = n − 1 if n < 30 and k = n if n > 30, and n—is the number of data. Low RMSE values show that the model makes more accurate predictions and fits the data well, and low MRE means the estimated value is closer to the actual value, indicating greater precision. Regression analysis and the coefficient of determination were used to assess how closely the measured and model-predicted data agree.

Water retention curves: characteristic points and division areas

The water content in soil varies nonlinearly with the change in matric suction with inflections, mainly at the beginning and end of the course (Fig. 3). The course of these changes is described by a curve called the soil water retention curve, which is usually sigmoidal in shape. It presents the relationship between the water content and the matric suction of the soil. The shape and course of this relationship vary depending on the type of soil and due to the hysteresis phenomenon. The course of the retention curve during the drying and wetting processes is different, with higher water content values during drying for the same matric suction values. It has been assumed that three typical dividing zones can be distinguished in the retention curve, whose boundaries are determined by the intersection points of three lines fitted into the experimental data or by the theoretical retention curve described by different models/equations, e.g. Brooks Corey51, van Genuchten1, Kosugi52, Fredlund and Xing53, and other similar models. The first point is the intersection of the first line fitted into the initial part of the curve, close to the first bend, with the second line from the middle part fitting (embracing) within the boundaries of the first and second bend of the curve. The second point is the intersection of the second straight line with the third straight line fitted after the second bend of the retention curve. The first and second points are the dividing points of the areas for three zones on the retention curve, including the boundary effect zone, the transition zone with the inflection point, and the residual zone (Fig. 3). Individual zones can be assigned capillaries with appropriate radii and corresponding water volumes, which are responsible for the water flow by hydraulic conduction. Inflection points on the retention curve during drying separate the air entry value (AEV) and residual suction with residual water content (RWC). AEV corresponds to the suction value at which air enters the biggest soil pores. On the other hand, the point of suction in the residual state means the minimum water content, in which the increase in suction does not cause a noticeable change in the water content. In the case of the wetting curve, the suction point in the residual state is the point referred to as the water entry value (WEV), at which there is a significant increase in water content. As wetting progresses, the water content increases up to the inflection point on the retention curve, at which the air discharge pressure no longer allows a noticeable increase in the water content. The air expulsion discharge point indicates that there is residual air content in the soil. With zero suction, the water content is lower during wetting than with drying. The difference in the water content between drying and wetting is the residual air content in the wetting process. In contrast, the air discharge pressure is less than the air entry value.

Soil water retention curve: a) determination of characteristic points p1 (34.0, 0.364) and p2 (64.9, 0.090) from the intersection of lines fitted into selected areas of empirical data with the inflection point and regression equations, b) determination of the mean radii of capillaries ri and the corresponding water content Δθi, i = 1.2,…,5. The data used in the example are taken from the work of Brooks and Corey51.

Determination of water contents and suctions on the soil water retention curve for characteristic inflection points

The coordinates of two points at the intersection of lines fitted into the drying retention curve were determined from the equality of water content from equations one and two, the equality of values from equations two and three, and vice versa in the wetting process. As mentioned earlier, the first point of the intersection of lines is the point of the air entry value and the second point is the point of residual water content. In the wetting process, the point of residual water content from the drying process is called the starting point of water ingress. Each of these points occurs at a different matric suction, which can be determined from the middle equation for the transition stage and the inflection point, after substituting the water content at the points of intersection of the straight lines (Fig. 3). The determined water content and matric suction values at the intersection points of the straight lines will allow us to determine the water content in individual parts of the retention curve and the average capillary radii for these parts.

The characteristic two inflection points (p1,p2) were determined from the regression equations inside (Fig. 3a) after their comparison: − 0.00009x + 0.3674 = − 0.0089x + 0.6672, transformation 0.00881x = 0.2998 and division, x = 34.03 for p1 and similarly for p2 − 0.0089x + 0.6672 = − 0.0002x + 0.1025, − 0.0087x = − 0.5647, x = 64.9. After substituting the value of x into the second equation, we get the values of the water content for these points: y = − 0.0089 × 34.03 + 0.6672 = 0.3643 for p1 and y = − 0.0089 × 64.9 + 0.6672 = 0.0896 for p2.

Assuming that water retention curves are divided into k parts (Fig. 3b), the average radius of capillary ri, and the corresponding water content Δθi were determined for each such part. The parts may be equal or not or can be based on past experimental or predicted results by different water retention models. It has been proposed to divide the water retention curve into five parts, k = 5. Part one, i = 1, includes the boundary effect zone. The second, third, and fourth parts, i = 2, 3, 4, are within the transition zone with the inflection point, and the fifth part, i = 5, includes the residual zone. In the first part, water content Δθ1 is the difference between saturation θs and θ (hAEV) at the point of the air entry value hAEV on the measured or model water retention curve. The air entry value hAEV is the matric suction value at the intersection of the first and second lines. The second, third, and fourth parts cover the water content Δθ2, Δθ3, and Δθ4 between the water content at the air entry value hAEV, (θs – Δθ1) and the residual water content θRWC at the matric suction point, hRWC (the intersection of the second and third lines). Each part covers 1/3 of the transition zone. The water content in the transition zone equals: θ2,3,4 = θs—Δθ1—ΔθRWC. The water content in the individual parts equals: Δθ2, Δθ3, Δθ4 = (θs—Δθ1—ΔθRWC)/3. The fifth part of the water content Δθ5 equals the residual water content θRWC and includes the residual zone. For each part of the water content, the average capillary radius is calculated from \({r}_{k}=\frac{1}{n}{\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{r}_{i} k=\text{1,2},\dots 5\). The capillary radii were calculated from the initial height hp (in cm) to the final height hk in a separate portion of the water contents (Δθi) on the measured or model retention curve with a given step of matric suction, e.g. h = 1 cm H2O. The mean capillary radius r1 includes matric suction from h = 1 cm to the value hAEV at the air entry value with a step of 1 cm. Average capillary radii r2, r3, and r4, were calculated as in the first part. The mean radius of the second capillary, r2, is equal to the mean value of all capillary radii calculated with a step of 1 cm H2O from the value of matric suction at the air entry value hAEV to matric suction values h2 corresponding to the water content, θ2 = θs – Δθ1 – Δθ2. The third mean radius of the capillary, r3, is calculated from the suction h2 into h3 for the content θ3 = θs – Δθ1 – Δθ2 – Δθ3. The fourth mean capillary radius, r4, is calculated from the matric suction h3 into h4 for the content θ4 = θRWC. The fifth part is the residual water content θRWC = Δθ5, with the adopted capillary radius, r5, corresponding to the suction value h4 of the water column height for residual water content θRWC. With the reduction of the residual water content θRWC, the share of the fifth capillary will decrease and that of the sixth air capillary will increase in hydraulic conductivity. The wetting and drying curves are similarly divided to calculate water contents and average capillary radii. In this work, it was assumed that the radius of the sixth capillary is equal to 1/4 of the radius of the fifth capillary and does not change in the range of water content from saturation to residual water content. Below the residual water content, the capillary radius varies with the decreasing water content according to a given function to a capillary radius of 1.419E-03 µ m, which corresponds to matric suction h = 1.05092 × 106 cm or h = 1.03057 × 105 kPa.

Determination of the probability of finding a capillary in a single sample

The total soil porosity was determined from the results of bulk density and particle density or was equal to the saturated water content in the drying process. It is assumed that the total porosity equals the saturated water content and the maximum air content in the soil. In both the drying and wetting processes, each separated branch of the retention curve was divided by the total porosity (ϕ).The obtained values in the volume unit of fi, (m3 m−3), i = 1, 2,…, 6 are treated as probabilities of obtaining a result of type i in a single sample. So: f1 = Δθ1/ϕ, f2 = Δθ2/ϕ, f3 = Δθ3/ϕ, f4 = Δθ4/ϕ, f5 = Δθ5/ϕ, and f6 = (ϕ − θ)/ϕ, where Δθi are the water contents at individual matric suction points determined from the retention curve, θ is the current water content, and ϕ − θ is the air content. It should be noted that, at the zero matric suction during the drying process, the probability of finding an air particle in a single sample is zero, while in the wetting process, it will be equal to the ratio of residual air content to total porosity. Knowing that the flows in the path of vapor and water films are several orders of magnitude lower than the flows of water between solid particles, it can be concluded that the hydraulic conductivity in the wetting process will be significantly lower than in the drying process, which has also been confirmed experimentally (e.g.54).

The probability of a given capillary configuration in \(P\left({x}_{1j},\cdots ,{x}_{6j}\right)\) in the statistical-physical model of hydraulic conductivity can be calculated from a multinomial distribution limited to six elements:

where: x1, x2 ,…, x6—the number of capillaries formed between the particles of the medium, where: \({\sum }_{i=1}^{6}{x}_{ij}=u\), j = 1,2,…,L, fi, i = 1, 2,…, 6, are the probabilities of finding a capillary in a single sample.

Results

The mean capillary radii ri determined with the adopted procedure and corresponding water contents, Δθi, i = 1.2,…,5, and with linear equations fitted into individual zones with a boundary effect stage (p1), a transition stage with an inflection point, and a residual stage (p2) (Table 1) based on the experimental data in Gallage et al.45 and Wayllace and Lu44 will be presented below.

Determination of soil water contents and matric suctions as input data for the statistical-physical model

The numerical values of matric suction (h (in cm H2O) and water content (WC) are given in Table 2 and presented graphically at the intersection of the straight lines denoted as points p1 and p2 (Figs. 4 and 5, Table 1). The h values of the p1_ and p2_ points increased with the increasing bulk density in the Edosaki and Chiba soils. For the Edosaki soil, the matric suction values for the p1_ and p2_ points increased at drying with the increasing initial bulk density (from 1220 kg m−3 in _d1 to 1350 kg m−3 in _d2) from 14.36 to 21.19 and from 95.54 to 148.21, respectively (Fig. 4). The corresponding increases at wetting (from _w1 to _w2) due to the increasing initial bulk density were from 7.98 to 11.04 and from 102.86 to 114.57, respectively. For the Chiba soil, the matric suction values for p1_ and p2_ increased with the increasing bulk density (from 1250 kg m−3 in _d1 to 1420 kg m−3 in _d2) from 24.40 to 43.37 and from 266.2 to 475.15 cm H2O, respectively. The corresponding increases at wetting (from _w1 to _w2) due to the increasing initial bulk density were from 4.81 to 5.43 and from 101.06 to 215.94 cm H2O, respectively.

Drying and wetting retention curves of two sandy soils: Edosaki soil with initial dry density of 1220 kg m–3 (a) and with initial dry density of 1350 kg m–3 (b); Chiba soil with initial dry density of 1250 kg m–3 (c) and with initial dry density of 1420 kg m–3 (d) with medium capillary radii, ri and the corresponding water contents, Δθi, i = 1.2,…,5, and with linear equations fitted into the individual zones with a boundary effect stage, a transition stage with an inflection point, and a residual stage. The experimental data are derived from Gallage et al.45.

Drying and wetting retention curves of soils: (a) Remolded Sandy Colluvium, (b) Remolded Silty Clay and c) Undisturbed Silty Clay with mean capillary radii, ri and corresponding water contents, Δθi, i = 1.2,…,5, and with linear equations fitted into individual zones with a boundary effect stage, a transition stage with an inflection point, and a residual stage. The experimental data are derived from Wayllace and Lu44.

The WC water content (in m3 m−3) decreased at drying with the increasing bulk density for p1_ from 0.434 to 0.409 in the Edosaki soil and from 0.522 to 0.445 and from 0.418 to 0.415 in the Chiba soil, while at wetting it increased from 0.335 to 0.364 in the Edosaki soil (Tables 1, 2 and Fig. 4). However, the p2_ values increased with the bulk density in the Edosaki soil from 0.094 to 0.117 at drying and from 0.082 to 0.095 at wetting. The corresponding increases for the Chiba soil were from 0.211 to 0.228 and 0.195 to 0.224.

In the Remolded Sandy Colluvium, the Remolded Silty Clay, and the Undisturbed Silty Clay, the matric suctions h (in cm H2O) for p1_ and p2_ in the drying course were 30.06 and 159.11, 179.27 and 2636.02, and 33.63 and 1363.46, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 5). The corresponding matric suction in the wetting course were lower, namely 14.85 and 54.74, 15.40 and 264.33, and 32.05 and 1270.76. For these soils, the WC water content (m3 m−3) was generally lower during wetting in p1_ and p2_ (0.284 and 0.024, 0.321 and 0.145, and 0.327 and 0.143) than during drying (0.386 and 0.022, 0.472 and 0.201, and 0.434 and 0.186). For all soil specimens and their bulk densities, the matric suction at the p1_ point was greater during drying than wetting, but was lower for the p2_ point, except for p2_E_w1.

The exact values of the capillary radii (ri, i = 1.2,…,6) with the corresponding water/air contents (WC_) and probabilities (P_) are summarized in Table 2. For visual comparison of the soils, the data from Table 2 are depicted in Fig. 6.

Capillary radii (r1, …, r5) and (r6) with water content (WC_) and air content, a, c); Capillary radii with probability (P_) of finding a capillary in a single sample b, d). Explanation of symbols: (a) Edosaki soil with initial dry bulk density of 1220 kg m–3 (drying – E_d1, wetting – E_w1) and with initial dry bulk density of 1350 kg m–3 (drying – E_d2, wetting – E_w2); Chiba soil with initial dry bulk density of 1250 kg m–3 (drying – Ch_d1, wetting – Ch_w1) and with initial dry bulk density of 1420 kg m–3 (drying – Ch_d2, wetting – Ch_w2) and (b) Remolded Sandy Colluvium (drying – RSC_d1, wetting – RSC_w1), Remolded Silty Clay (drying – RSC_d2, wetting – RSC_w2), Undisturbed Silty Clay (drying – USC_d1, wetting – USC_w1).

In general, the average capillary radii of r1 to r6 (in µm) in the wetting process were greater than those in the drying process in both the Edosaki (506.6 to 1.39 vs. 329.9 to 1.33) and Chiba soils (681.0 to 0.86 vs. (227.6 to 0.57) at low bulk densities d1/w1 (Fig. 6a). Also at higher densities d2/w2, the average capillary radii of r1 to r6 were in most cases greater at wetting than drying for both the Edosaki soil (409.4 to 0.84 vs. 258.9 to1.05) and the Chiba soil (608.9 to 0.59 vs. 153.6 to 0.34). In the Edosaki soil, the capillary radii in the wetting process were higher than in the drying process by 1.62 to 1.04 times and by 1.78 to 0.8 times at higher densities, depending on the compared capillary radius. For the Chiba soil, the capillary radii at the wetting process were higher than in the drying process by 4.51 to 1.51 times at low density and by 6.03 to 1.73 times at high density, depending on the compared capillary radius. The differences between the wetting and drying processes were the highest with r2 and the lowest with r6 in both soils.

In Remolded Silty Clay, the average capillary radii of r1 to r6 varied (in µm) from 315.1 to 0.48 during the wetting process and from 48.3 to 0.1 during the drying process (Fig. 6c). As in the Edosaki and Chiba soils, the highest differentiation was found in r2 (15.38 times), and the smallest differences were recorded in r6 (4.31 times). In Remolded Sandy Colluvium, the mean capillary radii from r1 to r6 ranged from 329.9 to 3.36 µm at wetting and from 198.6 to 0.72 μm in the drying process, and the differences varied from 1.66 to 4.64 times. For the Undisturbed Silty Clay, the ranges of changes in the radii were similar at wetting (189.1 to 0.19 μm) and drying (184.8 to 0.20), and thus the differences were slight (from 1.0 to 1.16 and from 1.16 to 0.97 times) with a round-trip drop from the r3 radius.

The water contents in the capillaries from r1 to r5 for all soil specimens were lower in the wetting process than in the drying process from 0.517 to 0.983 times (from 0.029 for r1 in WC_Ch_d1 to 0.228 m3 m−3 for r5 in WC_Ch_d2), except r5 for Remolded Sandy Colluvium, where it was slightly higher (1.083 times; 0.022 m3 m−3), and for the Edosaki and Chiba soils, this differentiation decreased for the higher bulk densities (Table 2). The water contents for the r2, r3, and r4 radii were the same but different in each soil. In the Edosaki soil at drying (r1, r2-r4, r5), they were 0.032, 0.105, and 0.094 (in m3 m−3) for the density of 1220 kg m−3 and 0.026, 0.09, and 0.117 for the density of 1350 kg m−3. The corresponding values at wetting were 0.022, 0.081, and 0.82 m3 m−3 and 0.025, 0.085, and 0.095. In the Chiba soil, the water contents at drying were 0.029, 0.096, and 0.211 with the 1250 kg m−3 bulk density and 0.020, 0.068, and 0.228 with the 1420 kg m−3 bulk density. The corresponding values at wetting were 0.015, 0.70, and 0.195 and 0.019, 0.061, and 0.224. For Remolded Sandy Colluvium, the water content in capillaries r1, r2-r4, and r5 in the drying and wetting processes were 0.033, 0.112, and 0.022 and 0.028, 0.079, and 0.024 m3 m−3, respectively. In the Remolded Silty Clay and the Undisturbed Silty Clay, the water contents in these capillaries were similar at both drying: 0.030, 0.083, and 0.201 and 0.023, 0.077, and 0.186, respectively, and at wetting: 0.020, 0.055, and 0.145 and 0.017, 0.057, and 0.143 m3 m−3. The reduction of the water content in capillaries r1 to r5 in the wetting process resulted in increased air content in sixth air capillary. The air content decreased from 0.095 m3 m−3 (in WC_E_w1 at bulk density 1220 kg m−3) to 0.04 m3 m−3 (in WC_E_w2 at bulk density 1350 kg m−3) in the Edosaki soil and from 0.108 m3 m–3 (in WC_Ch_w1) at density 1220 kg m–3) to 0.027 m3 m–3 (in WC_Ch_w2) at density1420 kg m−3) in the Chiba soil. In the case of the Remolded Sandy Colluvium, the Remolded Silty Clay, and the Undisturbed Silty Clay, the air contents (in r6) were 0.100, 0.110, and 0.150 m3 m−3, respectively. The probabilities reflect the water content of the individual capillaries, and the changes were the same as the water content (Fig. 6 b,d).

The radii of the sixth air capillary in the drying and wetting courses were equal to 1/4 of the r5 radii and remained constant from full soil water saturation to the residual water content in all soils (Fig. 7). Below the residual water content, the r6 radii decreased with the decreasing soil water content to 1.491E-3 µm for all soils, except for the Undisturbed Silty Clay USC_d1 and w1, where it was decreased to 3.728E-3 µm. In the Edosaki and Chiba soils, the constant radii in the drying course decreased with the increasing density from 1.33 to 1.05 and from 0.54 to 0.34 µm, respectively (Fig. 7a). In the wetting course, they decreased with the increasing density from 1.39 to 0.84 µm in the Edosaki soil and from 0.86 to 0.59 µm in the Chiba soil. In Remolded Sandy Colluvium, the r6 radius was lower in the drying course (0.72 µm) than in the wetting course (3.36 µm) (Fig. 7b). In the Remolded Silty Clay and the Undisturbed Silty Clay, the radii of R6 were 0.11 and 0.20 µm, respectively, in the drying course and 0.48 and 0.19 µm, respectively, in the wetting process.

Capillary radius with air (y = r6) as a function of water content (x = WC) below the residual value (RWC) with exponential and linear equations. Explanation of symbols in the figure, (a) Edosaki soil with initial dry density of 1220 kg m–3 (drying – E_d1, wetting – E_w1) and with initial dry density of 1350 kg m–3 (drying – E_d2, wetting – E_w2); Chiba soil with initial dry density of 1250 kg m–3 (drying – Ch_d1, wetting – Ch_w1) and with initial dry density of 1420 kg m–3 (drying – Ch_d2, wetting – Ch_w2) and (b) Remolded Sandy Colluvium (drying – RSC_d1, wetting – RSC_w1), Remolded Silty Clay (drying – RSC_d2, wetting – RSC_w2), Undisturbed Silty Clay (drying – USC_d1, wetting – USC_w1).

The values of the regression coefficients (a) in the linear equation, according to which the capillary radii decreased with the water content, were greater in the wetting than drying courses for all soils and decreased with the increasing density for the Edosaki and Chiba soils (Fig. 7).

Comparison of measured and modeled hydraulic conductivities during the drying and wetting processes

Figure 8 presents the calculated hydraulic conductivity and experimental data over the range from a dry state to water saturation with a linear change in the sixth air capillary radius below the residual water content (Fig. 7). The solid line is the soil drying, the dotted line is wetting, and the measured data points are denoted by + during drying and ° during wetting; ◊ and △ represent saturated hydraulic conductivity during drying and wetting, respectively. Saturated hydraulic conductivity for the Edosaki and Chiba soils was higher at the smaller vs. higher initial bulk density in the drying course, while the conductivity during wetting was similar, irrespective of bulk density (Table 3, h = 1 cm and Fig. 8 a,b,c,d). The courses of unsaturated hydraulic conductivity during drying and wetting were similar in the Edosaki and Chiba soils and the Undisturbed Silty Clay (Fig. 8g). The diminution in the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity with the decreasing water content was slower at the lower than higher initial soil density for the Edosaki and Chiba soils. Also, the differences in water contents at saturated hydraulic conductivity in the wetting process were higher at the lower than higher soil bulk densities.

Hydraulic conductivity with water content during drying and wetting (Edosaki sand with bulk density of 1220 (E_d1, E_w1) and 1350 kg m–3 (E_d2, E_w2); Chiba soil with bulk density of 1250 (Ch_d1, Ch_w1) and 1420 kg m–3 (Ch_d2, Ch_w2); Remolded Sandy Colluvium (RSC_d1, w1), Remolded Silty Clay (RSC_d2, w2), and Undisturbed Silty Clay (USC_d1, w1). Denoted by: c calculated, m measured, s saturated, + measured hydraulic conductivity in the drying process, ° measured hydraulic conductivity in the wetting process, ◊ measured saturated hydraulic conductivity in the drying process, Δ measured saturated hydraulic conductivity in the wetting process. The experimental data are derived from Gallage et al.45 and Wayllace and Lu44.

However, in Remolded Sandy Colluvium and Remolded Silty Clay, the conductivity curves were spaced apart, and the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity in the wetting course decreased more slowly than in the drying course (Fig. 8e,f). In all soils, the calculated and measured saturated hydraulic conductivities were in satisfactory agreement during drying and wetting (Fig. 8 and Table 3; see results at h = 1 cm).

The R2 values for the Edosaki and Chiba soils ranged from 0.912 to 0.991, and the regression coefficients (a) were in the range from 0.646 to 0.997 at different densities during drying and wetting except the Chiba soil during wetting at the higher density (Fig. 7d), where the agreement was less satisfactory (R2 = 0.617, and regression coefficient a = 1.753) (Table 3). It should be noted that the calculated hydraulic conductivity coincided well with the measured data across the whole water range at drying, whereas good agreement during drying was only observed at water saturation and deviated in the unsaturated conditions. It can be presumed that small changes in the measured unsaturated hydraulic conductivity values (Fig. 8d) at the lower water content and the higher bulk density were probably a consequence of preferential flow, which was not included in the presented wetting retention curve (Fig. 6d).

The assumption that the equivalent capillary lengths were the same in both the drying and wetting processes but different for the different soils and densities was confirmed by the results of the calculations. The equivalent capillary lengths were higher in soils with higher clay fraction content. The equivalent capillary length of the Edosaki soil containing 83.6% of the sand fraction was longer l = 1000 at the higher density (1350 kg m−3) than at the lower density (1220 kg m−3) l = 665 (Table 3). In the case of the Chiba soil, with 64.0% sand content, the lower equivalent length l = 830 was recorded at the higher density (1420 kg m−3) and a greater value l = 1090 was noted at the lower density (1250 kg m−3). The higher equivalent lengths occurred in the Remolded Sandy Colluvium RSC1 l = 3950, the Remolded Silty Clay RSC2 l = 6500, and the Undisturbed Silty Clay USC1 l = 315,000. The mean number of water flow paths characterized by the number of parallel capillary connections (u) was lower at wetting (u mostly from 3 to 5) than during drying (u = 7) and was generally smaller for soils with higher content of sand fractions.

For the Edosaki soil, the RMSE values between the measured and model-predicted results at the same lower bulk density were higher during drying (3.04E-06 m s−1) than wetting (2.74E-06 m s–1) processes, and during drying, it was smaller at the higher than lower bulk density. The RMSE for the Chiba soil was smaller at the higher (3.56E-07 m s−1) than lower bulk density (1.65E-06 m s−1) during drying. At the higher density, it was higher during wetting (1.98E-06 m s−1) than drying (3.56E-07 m s−1). The MRE values for the Edosaki soil with the lower bulk density were 73.0% during drying and slightly lower during wetting at the lower bulk density and drying at the higher bulk density (68.8–70%). The highest MRE value for the Chiba soil was recorded at the higher bulk density during wetting (94.3%) and decreased consecutively at the lower bulk density (80.6%) and at the higher bulk density during drying (41.5%). In general, the regression coefficients were close to unity during the drying process and were less than or greater than unity during wetting in the Edosaki and Chiba soils (Table 3).

Discussion

Effect of drying and wetting on hydraulic soil properties

Our results showed that the water contents at which the hydraulic conductivity reached maximum values were greater at the drying than the wetting process, irrespective of the tested soil specimen (Fig. 8). This can be ascribed to the ink-bottle effect and the presence of entrapped air that blocks wetting and water movement45,55. The most pronounced blocking effect observed in Remolded Sand Colluvium and Silty Clay can be explained by volumetric deformation and formation of a heterogeneous pore structure32 during remolding, leading to the strengthening ink-bottle effect. A more noticeable effect of remolding was observed in the more finely textured Silty Clay than Sand Colluvium. This may result from additional soil deformation in the former by clay swelling and associated reduction in the pore volume for water storage and movement. Furthermore, the deformation of the soil structure due to remolding resulted in hysteretic behavior of unsaturated hydraulic conductivity to a greater extent at a higher-than-low water content range (Fig. 8e,f). This differentiation implies that a larger degree of hysteresis of the hydraulic conductivity was dominated by capillary conductivity and adsorption at a low water content range. In contrast, there was no visible hysteretic effect in the saturated hydraulic conductivity; hence, it can be regarded as slightly variable or even constant for a particular soil type and structural state.

Capillary length (l) and number of parallel connections (u)

The output data of the modified statistical-physical model confirmed the assumption that the equivalent capillary lengths were the same in both the drying and wetting processes and, at the same time, well predicted their changes caused by the initial soil bulk density. The effect of the initial bulk density on the equivalent capillary length was related to the soil type. In the sandier Edosaki soil (83.6% sand fraction), the increase in the initial bulk density resulted in a greater equivalent capillary length (from 665 to 1000), while in the more finely textured Chiba soil (64% of sand), it led to capillary length reduction from 1090 to 830. Furthermore, in soils with higher initial bulk density, especially in the Chiba soil, the water retention curve during drying shifted toward high 1.419E-03 suctions, including the characteristic points of the air entry value and residual water content (Fig. 4). The water content and matric suction values at these points help to determine the average capillary radii in the main parts of the retention curve with the statistical-physical model. The data also well forecast a massive reduction of capillary length by remolding (from 315,000 up to 6500) of the Undisturbed Silty Clay and reflect a reduction of pore tortuosity. Such a significant decrease can be induced by the disruption of the aggregate structure and shearing during remolding. Furthermore, the data on capillary properties are used in assessing Darcy flux, soil water storage, capillary matric potential, capillary rise, and redistribution of water during infiltration and drainage56,57. It is worth noticing that the effect of remolding in the silty clay resulted in higher hydraulic conductivity during the wetting process over the whole water content range (Fig. 8f). These results indicate that remolding the fine-textured silty clay strengthens the hysteresis of both water retention and hydraulic conductivity curves. Air trapped in soil as well as soil expansion and contraction can be potential sources of the hysteresis of hydraulic properties (e.g.58).

Recent modeling developments help evaluate soil structure and the hysteresis effect induced by management practices and resulting changes in the relationship between pore size and suction. For example, the Peters–Durner–Iden (PDI) model system59,60 for predicting vapor, non-capillary, and capillary liquid conductivity parameters in combination with the approach developed by Tian et al.61,62 to predict the effects of soil structure deformation in compacted soil. The model proposed by Gao et al.63 helps assess hydraulic properties at various densities or void ratios and to separate deformation and hysteresis effects. In remolded compared to undisturbed soil hysteresis can be developed by lower suction under the same moisture64, and this effect can differ depending on soil type. These approaches create a new opportunity for forecasting soil hydraulic behaviour based on experimental data.

Advantages and limitations of the statistical-physical model and further studies

One advantage of the statistical-physical model is its ability to accurately predict the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils at low values of the degree of saturation, including the conductivity domains of film water adsorbed at the surface of solid particles and water vapor diffusing through the gas-filled pore space (e.g.,47,48). This ability may result from the improvement of the model by incorporating an additional sixth air capillary, into three precisely defined zones on the retention curve, which is responsible for the flow processes through vapor and water films. This improvement, along with the original version of the statistical-physical model for predicting the domain of capillary conductivity46, makes the updated model more suitable for predicting overall hydraulic conductivity across the entire range of measured water contents during both the drying (desorption) and wetting (sorption) processes. In soil water physics, the van Genuchten–Mualem (VGM) model is often used as the reference model for parametrization of hydraulic properties. The VGM single-domain or two-domain models, as well as the statistical-physical model, encompass flow through matrix pores or through matrix pores and macropores. The VGM model and the statistical-physical model scale to saturated hydraulic conductivity using soil retention curve models. In the statistical-physical model, hydraulic conductivity is averaged by considering all combinations of matrix pores and macropores and taking into account the probabilities of occurrence of a given pore and macropore configuration. Furthermore, two parameters are obtained, which can be attributed to pore tortuosity, described by the equivalent capillary length and the number of degrees of freedom, which can reflect the average number of water flow channels between pores or macropores, as well as those that can reflect blocking of water flow by trapped air during soil wetting. In the VGM model approach, the matrix and preferential flow are averaged by adding the appropriate hydraulic conductivities with assigned weights corresponding to individual conductivities. This approach enhances the model’s applicability for soils exhibiting hysteretic behavior of hydraulic properties. From calculations and comparisons of hydraulic conductivity values performed during the wetting and drying processes, we observed that the air capillary radius is close to four times the value of the matric suction at residual water content. This observation was satisfactorily validated and allowed for the reduction calculations of hydraulic conductivity at low soil water content. However, further in-depth research is required to justify weather this observation is universal.

It should be noted that the measured datasets for validation, e.g., Edosaki, Chiba, and silty clay soils, were mostly based on water contents higher than approximately 0.2 m3 m⁻3, which does not cover the adsorption-dominated range. The model performance in a wider range of water contents was satisfactory when using only the data during the drying process for both sandy soil and parent materials46,47.

The model output data revealed that the mean number of water flow paths characterized by the number of parallel capillary connections (u) (degrees of freedom, coordination number) was higher at drying (u = 7) than at wetting (u mostly from 3 to 5) at the same equivalent capillary lengths l calculated with the statistical-physical model. This implies that soil air reduces the number of parallel connections u and provides resistance to water movement during wetting. Also, the smaller number of parallel connections in soils with higher content of sand fractions can be attributed to large air pores in coarser-textured soils.

Although this model contributes to the prediction of overall conductivity by incorporating the domains of the capillary and vapor at a low degree of saturation conductivity, it needs further improvements. The model predictability of hydraulic conductivity could be improved in further studies by adding domain for non-Darcian flow (preferential) through macropores that affect water and air movement and plant root growth and are a key feature of soil quality (e.g.,67).

Some authors suggest that dual-permeability models separating the matrix from the macropore flow could be helpful65,66,68,69. Recently, Wang et al.70 showed that introducing a fixed non-zero matric potential to overcome the abrupt drop of hydraulic conductivity near saturation slightly improved the prediction of conductivity. Studies on the granite residual soil with a rich pore network showed that the reduction in the number of large connected pores with diameters exceeding 200 μm71 and removing pores 100–300 μm72 leads to the interruption of the previously robust preferential streamlines73. We intend in further study to use the statistical-physical model with consideration of the hydraulic conductivity by fitting the matrix and other structural domains in soils with bi-modal water retention curves (e.g.,74,75).

Summary and conclusions

The statistical-physical model of hydraulic conductivity is based on the averaging of water flow through soil pores as a net of capillary tubes using multinomial distribution. The original version of the model46,47 was modified in this work by fitting the capillaries into three precisely defined zones on the retention curve. One capillary was fitted into both the boundary effect and the residual zones with low dynamics of changes and three capillaries—into the transition zone with high dynamics. The sixth air capillary covered the entire retention curve with a constant radius to the residual zone and a varying radius with the decrease in water content to the minimum value. Such division was used for water retention curves during both the drying and wetting processes. The capillary length and the number of parallel capillary connections (flow paths) were determined from the equal values of measured and calculated saturated hydraulic conductivity from the drying and wetting processes, respectively. The sixth air capillary is responsible for the flow processes in capillary and adsorptive-dominant regions. The model was tested and validated during drying and wetting processes using measured data of variously textured soils with different compaction levels and soil disturbance. The statistical parameters showed good agreement between the measured and model-predicted data. The number of parallel capillary connections (u) (degrees of freedom, coordination number) was higher during drying (u = 7) than wetting (u mostly from 3 to 5) at the same equivalent capillary lengths. The smaller number of parallel capillary connections (flow paths) in the wetting process was ascribed to the reduction of water flow paths by air blocking. The u values decreased in soils with higher sand content. This predictability of the modified statistical-physical model enlarges its applicability to describe the effects of soil compaction, land use, and tillage management practices on soil hydraulic properties during drying and wetting processes. The main advantage of the modification is the ability to predict accurately the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils at the full range of water content. Further studies are needed to improve the model predictability of the hydraulic conductivity considering preferential water flow through macropores.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

van Genuchten, MTh. A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 44, 892–898 (1980).

Kutílek, M. & Jendele, L. The structural porosity in soil hydraulic functions—A review. Soil Water Res. 3(Special issue 1), S7–S20 (2008).

Usowicz, B., Lipiec, J. & Siczek, A. Fitting the van Genuchten model to the measured hydraulic parameters in soils of different genesis and texture at the regional scale. Int. Agrophys. 38, 373–382. https://doi.org/10.31545/intagr/191380 (2024).

Kirkham, M. B. Principles of Soil and Plant Water Relations 500 (Elsevier Academic Press, 2005).

Gliński, J. & Lipiec, J. in Soil Physical Conditions and Plant Roots, 260 (1st Edn, CRC Press, 1990). Reissued 2018 by CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group ISBN 13: 978-1-351-07670-8 (ebk) (2018).

Hessel, R. et al. Soil-improving cropping systems for sustainable and profitable farming in Europe. Land 11, 780. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11060780 (2022).

Vanderlinden, K. et al. Water retention and field soil water states in a vertisol under long-term direct drill and conventional tillage. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 72(2), 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12967 (2020).

Haruna, S. I., Ritchey, E., Mosley, C. & Ku, S. Effects of cover crops on soil hydraulic properties during commodity crop growing season. Soil Use Manag. 39(1), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12803 (2023).

Krzyszczak, J. et al. Assessment of soil water retention characteristics based on VNIR/SWIR hyperspectral imaging of soil surface. Soil Till. Res. 233, 105789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105789 (2023).

Scarfone, R., Wheeler, S. J. & Lloret-Cabot, M. Conceptual hydraulic conductivity model for unsaturated soils at low degree of saturation and its application to the study of capillary barrier systems. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 146(10), 04020106. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0002357 (2020).

Kalumba, M., Bamps, B., Nyambe, I., Dondeyne, S. & van Orshoven, J. Development and functional evaluation of pedotransfer functions for soil hydraulic properties for the Zambezi River basin. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 72(4), 1559–1574. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.13077 (2021).

Zhuang, L., Bezerra Coelho, C. R., Hassanizadeh, S. M. & vanGenuchten, MTh. Analysis of the hysteretic hydraulic properties of unsaturated soil. Vadose Zone J. https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2016.11.0115 (2017).

Paltineanu, C., Dumitru, S. I. & Lăcătusu, A. R. Assessing land susceptibility for possible groundwater pollution due to leaching—A case study on România. Carpath. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 17(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.26471/cjees/2022/017/199 (2022).

Usowicz, B. & Lipiec, J. Modeling the hydraulic conductivity of two soils amended with biochars using a statistical-physical model. Int. Agrophys. 39, 413–425. https://doi.org/10.31545/intagr/205565 (2025).

van Genuchten, M. T. & Pachepsky, Y. A. Hydraulic properties of unsaturated soils. In Encyclopedia of Agrophysics (eds Gliński, J. et al.) 368–376 (Springer, 2011).

Ng, C. W. W., Zhou, C. & Chiu, C. F. Constitutive modelling of state-dependent behaviour of unsaturated soils: An overview. Acta Geotech. 15, 2705–2725 (2020).

Mirghafari, R., Sajjadian, S. S., Nikooee, E., Habibagahi, G. & Raoof, A. A pore network modeling approach to bridge void ratio-dependent soil water retention and unsaturated hydraulic conductivity curves. Eng. Rep. 6(12), e13012. https://doi.org/10.1002/eng2.13012 (2024).

Chen, H., Chen, K. & Yang, M. A new hysteresis model of the water retention curve based on pore expansion and contraction. Comput. Geotech. 121, 103482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2020.103482 (2020).

Al-Mahbashi, A. M., Elkady, T. Y. & Al-Shamrani, M. A. Hysteresis soil-water characteristic curves of highly expansive clay. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 22(9), 1041–1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2016.1229232 (2016).

Ahmed, G., Koursari, N., Kuchin, I. V. & Starov, V. M. Hysteresis of contact angle of sessile droplets on deformable substrates: influence of disjoining pressure. Colloids Surf. A 546, 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.03.006 (2018).

Haines, W. B. Studies in the physical properties of soil. V. The hysteresis effect in capillary properties, and the modes of moisture distribution associated there with. J. Agric. Sci. 20(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002185960008864X (1930).

Klausner, Y. Fundamentals of Continuum Mechanics of Soils (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Ming, F., Zhang, M., Pei, W. & Chen, L. A new hydraulic conductivity model of frozen soil considering the hysteresis effect based on fractal theory. Geoderma 442, 116790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2024.116790 (2024).

Rudiyanto, et al. A complete soil hydraulic model accounting for capillary and adsorptive water retention, capillary and film conductivity, and hysteresis. Water Resour. Res. 51, 8757–8772. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR017703 (2015).

Tokunaga, T. K. Hydraulic properties of adsorbed water films in unsaturated porous media. Water Resour. Res. 45, W06415 (2009).

Mualem, Y. A modified dependent-domain theory of hysteresis. Soil Sci. 137, 283–291 (1984).

Jeong, N., Choi, D. H. & Lin, C. L. Estimation of thermal and mass diffusivity in a porous medium of complex structure using a lattice Boltzmann method. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 51, 3913–3923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2007.11.045 (2008).

Voller, V. R. A direct simulation demonstrating the role of spacial heterogeneity in determining anomalous diffusive transport. Water Resour. Res. 51, 2119–2127 (2015).

Feng, S. J., Chen, H., Zheng, Q. T. & Chen, H. X. Fractal analytical solution of gas diffusivity in heterogeneous porous media over the entire saturation range. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 188, 122652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.122652 (2022).

Al-Dakheeli, H. & Bulut, R. Interrelationship between elastic deformation and soil-water characteristic curve of expansive soils. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 145(4), 04019,005. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0002020 (2019).

Birle, E., Heyer, D. & Vogt, N. Influence of the initial water content and dry density on the soil-water retention curve and the shrinkage behavior of a compacted clay. Acta Geotech. 3(3), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-008-0059-y (2008).

Chen, K., Zhou, A. & Liang, F. Modelling the evolution of water retention hysteresis loops during soil deformation based on the ink-bottle effect. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.3683 (2024).

Karim, M. R., Hughes, D. & Rahman, M. M. Unsaturated hydraulic conductivity estimation—A case study modelling the soil-atmospheric boundary interaction. Processes 10, 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10071306 (2022).

Wen, T., Shao, L. & Guo, X. Permeability function for unsaturated soil. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 25(1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2018.1515666 (2021).

Burdine, N. T. Relative permeability calculations from pore size distribution data. Trans. Am. Inst. Min. Metall. Pet. Eng. 198, 71–78. https://doi.org/10.2118/225-g (1953).

Mualem, Y. A new model for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated porous media. Water Resour. Res. 12, 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR012i003p00513 (1976).

Peters, A. & Durner, W. A simple model for describing hydraulic conductivity in unsaturated porous media accounting for film and capillary flow. Water Resour. Res. 44, W11417. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR007136 (2008).

Tuller, M. & Or, D. Water films and scaling of soil characteristic curves at low water contents. Water Resour. Res. 41, W09403. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005WR004142 (2005).

Peters, A., Iden, S. C. & Durner, W. Prediction of absolute unsaturated hydraulic conductivity–comparison of four different capillary bundle models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 27(24), 4579–4593. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-27-4579-2023 (2023).

Lebeau, M. & Konrad, J.-M. A new capillary and thin film flow model for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated porous media. Water Resour. Res. 46, W12554. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009092 (2010).

Peters, A., Durner, W. & Iden, S. C. The PDI model system for parameterizing soil hydraulic properties. Vadose Zone J. 23, e20338. https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20338 (2024).

Agus, S. S., Leong, E. C. & Rahardjo, H. Estimating permeability functions of Singapore residual soils. Eng. Geol. 78, 119–133 (2005).

Tuller, M. & Or, D. Unsaturated hydraulic conductivity of structured porous media. Vadose Zone J. 1, 4–37. https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2002.1400 (2002).

Wayllace, A. & Lu, N. A transient water release and imbibition method for rapidly measuring wetting and drying soil water retention and hydraulic conductivity functions. Geotech. Test. J. 35(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ103596 (2012).

Gallage, C., Kodikara, J. & Uchimura, T. Laboratory measurement of hydraulic conductivity functions of two unsaturated sandy soils during drying and wetting processes. Soils Found. 53(3), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2013.04.004 (2013).

Usowicz, B. Statistical-physical models of mass and energy transfer in porous medium. Acta Agrophys. 29, 1–112 (2000) ((in Polish with English summary)).

Usowicz, B. Statistical approach for hydraulic conductivity of porous medium. Acta Agrophys. 53, 177–187 (2001) ((in Polish with English summary)).

Usowicz, B., Lipiec, J., Marczewski, W. & Ferrero, A. Thermal conductivity modelling of terrestrial soil media—A comparative study. Planet. Space Sci. 54, 1086–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2006.05.018 (2006).

Hajnos, M., Lipiec, J., Świeboda, R., Sokołowska, Z. & Witkowska-Walczak, B. Complete characterization of pore size distribution of tilled and orchard soil using water retention curve, mercury porosimetry, nitrogen adsorption, and water desorption methods. Geoderma 135, 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2006.01.010 (2006).

Wen, T., Chen, X., Luo, Y., Shao, L. & Niu, G. Three-dimensional pore structure characteristics of granite residual soil and their relationship with hydraulic properties under different particle gradation by X-ray computed tomography. J. Hydrol. 618, 129230 (2023).

Brooks, R.H. & Corey, A.T. Hydraulic properties of porous media. Hydrology papers, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, 3, 1–27 (1964).

Kosugi, K. Lognormal distribution model for unsaturated soil hydraulic properties. Water Resour. Res. 32, 2697–2703. https://doi.org/10.1029/96WR01776 (1996).

Fredlund, D. G. & Xing, A. Equations for the SWRC. Can. Geotech. J. 31, 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1139/t94-06 (1994).

Arrey, I. A., Odiyo, J. O., Makungo, R. & Katak, M. O. Effect of hysteresis on water flow in the vadose zone under natural boundary conditions, Siloam Village case study, South Africa. J. Hydroinform. 20, 88–99. https://doi.org/10.2166/hydro.2017.091 (2018).

Tan, Q. et al. Hysteresis of water retention curve of the capillarimetric diapason in saline soils. Eurasian Soil Sci. 57, 1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1064229323603426 (2024).

Kroes, J., Supit, I., van Dam, J., van Walsum, P. & Mulder, M. Impact of capillary rise and recirculation on simulated crop yields. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 2937–2952. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-2937-2018 (2018).

Aldrees, A. & Nachabe, M. Capillary length and field capacity in draining soil profiles. Water Resour. Res. 55, 4499–4507. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR024288 (2019).