Abstract

ATP, a high-energy phosphate compound also known as adenosine triphosphate, serves as a direct energy source for living organisms. Proteins, composed of amino acids, are fundamental macromolecules and essential building blocks of life. The interaction between proteins and ATP is crucial for various biological processes, including movement, regulation, and metabolism. Predicting the interaction between proteins and ATP is of paramount importance, particularly in modelling their binding sites and conducting downstream studies; therefore, advancements in techniques hold significant value for disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and drug design. However, current research methods face numerous challenges, such as the need for various algorithms to extract multilevel features and then integrate them into one deep learning model, which is inflexible and may result in the loss of important information implied in sequences. In this study, we propose a novel Large Language Model (LLM)-based model, the pretrained fractional-order deep convolution neural network (PFDCNN), to predict protein–ATP binding sites through sequence information that is extracted from protein sequence features by a pretrained protein large language model; then, we employ a deep convolutional neural network with fractional-order backpropagation for prediction and modify the loss function to control the impact of data imbalance. We trained and tested our model on several protein–ATP binding site datasets, and the comparison results revealed that the PFDCNN exhibited excellent generalization ability, with accuracies of 0.99 and 0.984 and AUC values of 0.965 and 0.941, respectively, on two famous protein–ATP datasets, surpassing those of most existing protein binding site prediction models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interactions between proteins and ligands, including interactions between proteins and other substances such as nucleic acids and ATP, play crucial roles in the activities of organisms. ATP plays important roles in various motor, regulatory and metabolic processes in organisms as the main energy source combined with proteins. In the past, studies of protein and ATP binding sites have relied mainly on structural information of proteins or identification through biochemical experiments, but these methods have been limited by time and economic cost. In recent years, with the successful application of deep learning technology in computer vision, image recognition, and natural language processing, many studies have adopted many types of applications of deep learning algorithms to predict protein–ATP binding sites.

Evolutionary information based on sequences has become an indispensable predictive tool for protein-ATP binding prediction, continuously driving the advancement of this field. Since 2009, Chauhan’s team introduced ATPint [1], a series of sequence-based prediction methods have emerged continuously. ATPint established an effective prediction model by integrating position-specific scoring matrices (PSSM) with support vector machine (SVM) algorithms. In 2011, Chen et al. developed ATPsite [2] and NsitePred [3], which made progress in feature engineering. By introducing sequence features such as secondary structure, solvent accessibility, and residue conservation, they significantly improved the prediction accuracy. In 2013, Yu et al. optimized the model performance using the AdaBoost algorithm, they developed TargetATPsite [4], which innovatively applied residue evolutionary image sparse representation and integrated classification strategies. In the same year, Fang’s [5] team proposed the CLCLpred method, which achieved efficient prediction results by optimizing PSSM feature extraction and focusing on the conserved regions of the sequence. In 2018, Hu et al. developed the ATPbind system [9], which combined template-based predictors (S-SITE and TM-SITE) with sequence features (PSSM, predicted secondary structure, and solvent accessibility), and improved the model performance through a feature fusion strategy. Among them, the ATPseq component innovatively used the template prediction probability as a new feature input into the SVM classifier. In 2020, Song et al. [6] constructed a deep convolutional neural network model that integrated multi-scale feature extractors, and simultaneously utilized four features: PSSM, secondary structure, solvent accessibility, and One-Hot encoding, achieving breakthrough progress in prediction performance.

However, these methods still depend on one-hot encoding of protein sequences to extract sequence features. The secondary structure and solvent accessibility must be predicted by other algorithms (such as PSIPRED and ASAquick), which may result in the loss of important protein information and require complex manual design.

With the development of protein pretrained language models (pLMs) [12], one protein sequence could also be considered one language sentence, which can leverage the powerful ability of a large language model to extract information. Some representative models have achieved good performance in generating vector representations of proteins by capturing structural, functional and evolutionary information from large-scale protein sequences through self-supervised learning by methods such as the evolutionary scale model (ESM) [13] and ProtBert [14]. Some researches have been implemented based on these pretraining models such as: ATP-Deep [29], and E2EATP [30]. But these algorithms either not considering the data imbalance or not harnessing network to improve accuracy of prediction.

On the other hand, one important feature of any deep algorithm is the iteration of parameter optimization in backwards propagation, whereas the traditional method, which is a local optimization algorithm, usually adopts an integer order gradient to update parameters. However, with the development of fractional calculus, nonlocality and weak singularity have been introduced into the steepest descent method of neural networks, which introduces a fractional order gradient [32, 33]. Convolutional neural networks with fractional order gradients have been proven to exhibit outstanding convergence, high accuracy and the ability to escape local optima [20].

Therefore, in this study, we integrated a pretrained protein language model with a fractional order neural network to construct an LLM-based protein sequencing predictive model called the PFDCNN. This pretraining process relies on a large amount of unlabelled data and enables the model to capture intrinsic laws in the sequence through unsupervised learning; moreover, the extracted features undergo in-depth processing by a fractional-order neural network, which ultimately yields classification probabilities for ATP binding sites. Moreover, because protein–ATP binding site prediction is an imbalanced learning problem, the number of unbound residues is significantly greater than the number of bound residues. We proposed an improved loss function in the training model to correct the bias caused by imbalanced data. Afterwards, to optimize the performance of the PFDCNN, extensive training was conducted on a comprehensive protein–ATP binding dataset. Fine-tuning the fractional order of the neural network and selecting the pretrained model that yielded optimal results resulted in a significantly enhanced predictor.

The organizational structure of this article is as follow: firstly, we introduced the sources of database used for protein-ATP binding prediction. Then we exhibited the workflow of PFDCNN, selection of pretraining pLMs, different fraction-order CNNs, and the improved loss function. Next, we compared different construction structures of neural network propagation, fraction-order deep convolution neural network predictor, MOE-based predictor, and the Transformer-based predictor, resulting in our PFDCNN achieving the best prediction performances. Finally, we compared the existing predictors, including: ATPint [1], ATPsite [2], NsitePred [3], TargetATPsite [4], TargetATP [11], TargetS [11], TargetNUCs [25], ATPseq [9], and E2EATP [11], where PFDCNN model could achieve the highest AUC.

Method

Dataset

We adopted two ATP binding site datasets, ATP-227 [7] and ATP-388 [9], to train all the models and chose ATP-17 [7] and ATP-41 [9] for testing. The ATP-227 dataset comprises 227 nonredundant protein chains whose pairwise sequence identity is strictly less than 40%. The ATP-17 dataset, constructed by Chen et al. [10], consists of 17 ATP-binding protein chains released after March 10, 2010, and serves as an independent test set. In 2018, Hu et al. [9] compiled an initial dataset of 2,144 ATP-binding protein chains and applied CD-hit [10] to remove redundant sequences with > 40% similarity, resulting in a refined set of 429 nonredundant sequences. These sequences were further partitioned into a training subset (ATP-388, 388 sequences) and an independent test subset (ATP-41, 41 sequences) for model validation. The number and ratio of binding and nonbinding sites in these datasets are shown in Table 1.

Model architecture

The workflow of the PFDCNN is shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1, the original protein sequences were first inputted into the model and extracted through a transformer-based protein pre-training model to extract protein features. Then, these features are input into a Four-layer fractional convolutional neural network. The neural network model includes convolutional layers and BatchNorm layers, and applies the backpropagation method in fractional-order convolutional neural networks, which divides the gradients in backpropagation into two parts. During the parameter update stage of intra-layer communication, fractional gradients are used. To apply the chain rule, integer gradients are used for communication between different layers of the neural network to avoid the complex derivatives of composite functions. Finaly PFDCNN output the probability results. In the following sections, we detail the feature extraction process of the pretraining model and the fractional-order convolutional neural network. The whole flowchart of this article is shown in Fig. 2.

Protein sequence embedding for feature representation

In this study, we adopted three pretrained language models, ESM-1b, ESM-2, and ProBert, to generate vector representations of proteins by capturing structural, functional and evolutionary information from large-scale protein sequences through self-supervised learning. The description of architecture of ESM can be found in Supplementary.

Here, we adopt two versions of the ESM algorithm, ESM-1b and ESM-2. ESM-1b contains 33 layers (33 attention layers) with approximately 650 million parameters and uses standard self-attention mechanisms and fully connected layers. ESM-2 is upgraded to a more efficient transformer variant with 15 billion parameters and uses larger databases, UniRef50 and UniRef90 (approximately 138 million sequences) [21].

On the other hand, ProtBert employs a BERT-style [15]. bidirectional transformer architecture with a whole-word masking strategy. Like the ESM, it learns protein representations through a masked language modelling (MLM) task, with inputs such as multiple sequence alignment (MSA) consensus sequences to enhance homology information, and outputs amino acid-level embedding or sequence-level aggregation features. The model provides generic protein sequence representations, similar to BERT in natural language processing, without explicitly integrating functional labels.

Furthermore, the visualization of features extracted using ESM-1b, ESM-2 and ProtBert, which revealed the consistency of the embedding space of the pretrained models with the real biological properties of proteins by jointly encoding structural features (colour) and physicochemical features (size), was shown in SuppleFigure1, demonstrating that the pretrained model is effective at capturing the multiscale biomedical features of proteins. Coordinate axes were generated by a dimensionality reduction method (t-SNE/PCA) and represent the potential feature space learned by the model.

Fractional order convolutional network

Here, we adopt the fractional order gradient method using Caputo’s fractional derivative, which is defined as follows: \(_{t}^{{Caputo}} D_{t}^{\alpha } f(t)\) = \(\frac{1}{{\Gamma (n - \alpha )}}\int_{t}^{t} {(t - \tau )^{{n - \alpha - 1}} } f^{{(n)}} (\tau )d\tau\), \(n - 1 < \alpha < n,\;n \in N^{ + }\), and \(\Gamma (\alpha ) = \int_{0}^{\infty } {x^{{\alpha - 1}} } e^{{ - x}} dx\). Fractional order differentiation can then be defined as follows: \(x_{K + 1} = x_{K} - \eta {}_{{x_{0} }}^{Caputo} D{}_{{x_{K} }}^{\alpha } f(x)\). To ensure that the fractional order gradient converges to the true extreme point \(x^{*}\), consider the following iterative steps for the fractional order gradient method [16]:

where \({\text{n}} - 1 < \alpha < n,n \in N^{ + }\), \(\Gamma (\alpha ) = \int_{0}^{\infty } {x^{\alpha - 1} } e^{ - x} dx\) is the Gamma function, \(t_{0}\) is the initial value, \({}_{{t_{0} }}^{Caputo} D_{t}^{\alpha }\) is an operator for fractional order differentiation, and \(\alpha\) is the order of the fractional order.

We utilized the feature dimensions from the last hidden state output of the pretrained model as the input feature dimensions for our backbone model. For protein sequences of different lengths, we performed appropriate padding or truncation to ensure that all the input sequences were standardized to a fixed length, denoted s (where s represents the protein sequence length). This preprocessing step allows the model to handle protein sequences of different lengths while maintaining consistency and accuracy in classification results.

Afterwards, the fractional order gradient algorithm is applied in the back propagation stage of the convolutional layer [17]. The parameter update formula for the convolutional layer is as follows:

where \([l]\) is the number of layers, \(K\) is the number of iterations,\(w\) is the weight, \(b\) is the bias,\(\alpha\) is the fractional order, and \(L\) is the loss function.

Improved loss function

We innovatively fuse weighted cross-entropy and focus loss functions: weighted cross-entropy balances the optimization direction by adjusting the class weights, while focus loss strengthens the focus on difficult samples (binding sites).

The weighted cross-entropy loss function formula is defined as follows:

where N is the number of samples, \(y_{i}\) is the true label of the ith sample (0 or 1), \(p_{i}\) is the probability that the model predicts the \(i\) th sample to be in the positive category, and \(\omega_{0} ,\omega_{1}\) is the weight factor for positive and negative samples, respectively.

The formula for the focus loss function [18] is \(FL(p_{t} ) = - \alpha_{t} (1 - p_{t} )^{\gamma } \log (p_{t} )\), where \(p_{t}\) is the classification probability that the current sample belongs to a specific class, \(1 - p_{t}\) is a modulator, \(\alpha_{t}\) is a weight factor that balances positive and negative samples, which suppresses the imbalance in the number of positive and negative samples, and \(\gamma\) is a hyperparameter that regulates the weights of easy and difficult samples, which is used to control the degree of decay of the weights of the easy-to-categorize samples.

Here we improved the loss function as the total loss: \(Loss = L + FL\).

Evaluation metrics

The evaluation metrics used in this study include accuracy (Acc), sensitivity (Sen), specificity (Spe), precision (Pre), and the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC).

Results

To validate the learning effectiveness and convergence performance of the PFDCNN, we conducted an extensive training process on the three training sets (ATP-227, ATP-388, and PATP-1930) for 100 epochs and recorded the corresponding loss values at each epoch. We then plotted the loss convergence curve to visualize this process. As shown in Fig. 3, the loss convergence curve clearly demonstrates that the model’s loss value gradually decreases as the number of training epochs increases and eventually stabilizes. This trend indicates that our model converges effectively during training and does so relatively rapidly. These results not only validate the effectiveness of our model but also provide a solid foundation for subsequent research and applications. By demonstrating stable and efficient convergence, we ensure that the model is reliable and ready for deployment in tasks such as protein–ATP binding site prediction, protein function analysis, and drug design.

Pretraining model selection

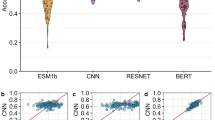

To study the effect of features extracted from different pretrained models on the training effect, the performances of three different pretrained models, ProtBert, ESM-1b, and ESM-2, were compared. The results, as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 4, indicate that ESM-2 is significantly better than the other two models, with a value as high as 0.965, and the accuracy (Acc) is also higher than that of the other two models, reaching 0.990. On the other hand, the sensitivity (Sen), accuracy (Acc), and MCC indices of ESM-1b are greater than those of the other two models. The specificity (Spe) of ProtBERT is only slightly higher than those of the other two methods. In summary, the effects of ESM-1b and ESM-2 are superior to those of ProtBert. Selecting disparate pretrained models can enhance the performance of our model, thus prompting our decision to employ ESM-2 as our pretrained model.

Fractional order selection

Since our model uses an iterative method based on fractional order gradients, our model has greater flexibility than the integer order gradient iterative method does, and we can select different fractional order gradients to tune the model to achieve the best performance. Table 3 shows the performance comparison of our model on the ATP-17 test set with different orders of fractional order gradients. We selected gradients with an order α between 0.65 and 1.3, with 0.05 as the interval, and all order accuracies reach 0.990 and greater, with the highest accuracy of 0.991 obtained at an order of 1.2, the highest AUC metric of 0.966 obtained at an order of 1.1, and the highest accuracy of 0.724 obtained at an order of 1.2, indicating that varying the fractional order improves our model performance relative to the integer order. We constructed a line graph of the AUC values for different fractional order orders, as shown in SuppleFigure 2, which reveals that the AUC values are relatively high, between 0.9 and 1.1, and the AUC values tend to decrease as the fractional order decreases to less than 0.75 or increases to greater than 1.25. Finally, the results of all the indicators are analysed comprehensively, and a fractional order of 0.9 is chosen for our model.

Improved loss function performance

To avoid the influence of severe class imbalance, we proposed one composite function by combining weighted cross-entropy loss function (L) and focus loss function (FL). Table 4 demonstrated the comparison between our composite loss function Total loss and the traditional loss function Cross-entropy, showing our improved loss function has achieved better sensitivity, specificity, precision and Mathews correlation coefficient among three training data sets: 227, 388 and 1930.

Protein sequence–ATP binding prediction

To fully validate the performance of the PFDCNN, we tested two independent protein sequences, protein 3LGXA and protein 3K5HA, and visualized the test data to generate Fig. 5, during which we compared the model prediction results with the real tags one by one. The comparison results presented in Fig. 6 indicate that our model has excellent prediction ability, which verifies its good performance in protein sequence analysis tasks. The green stars represent the actual protein–ATP binding sites, and the red stars indicate the binding residues predicted by the model. The predicted probability curves of the model are shown in blue. ‘Residue index’ refers to the residue index in the query protein sequence. The ‘predicted probability value’ indicates the probability that each residue in the query protein belongs to the ATP binding residue category.

In the prediction phase, our model uses a fractional deep convolutional neural network (FDCNN); we design three kinds of predictors, a deep convolutional neural network, a network based on a transformer module that contains two transformer–encoder layers and two layers of off-line transformation and uses a GELU activation function to perform the prediction, and a network based on DeepSeek [19]. The DeepSeek architecture uses the MOE technique, knowledge distillation technique and so forth, and we improve the transformer module on the basis of these techniques using an MOE architecture containing two expert layers and a knowledge distillation technique. The results show that the FDCNN outperforms the other two predictors for the following reasons. First, in protein sequence analysis, local sequence information is crucial for binding site prediction, and the FDCNN can efficiently capture these local features, such as specific combinations and alignments of amino acid residues, to more accurately predict binding sites. Second, the FDCNN can capture the spatial hierarchy information in protein sequences and gradually extract higher-level feature representations through layer-by-layer convolution and pooling operations. In contrast, the attention mechanism in the transformer model is powerful, but its complexity may result in an additional computational burden, while the FDCNN avoids this problem by directly extracting local features through a convolution operation. In addition, the feed-forward neural network in the transformer requires complex linear and nonlinear transformations, whereas the FDCNN can extract and integrate key information more directly through convolution and pooling operations. As a result, the FDCNN achieves better performance and higher accuracy in the protein binding site prediction, providing a superior solution for protein function analysis and drug design, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

Furthermore, we evaluated the prediction performance of existing sequence-based protein–ATP binding site predictors: ATPint [1], ATPsite [2], NsitePred [3], TargetATPsite [4], TargetATP [8], TargetS [8], TargetNUCs [25], ATPseq [9], and E2EATP [11]. First, we compared the performances of the models whose test dataset is ATP-17, whose corresponding training dataset is ATP-227, as shown in Table 5. The performances of the models whose test dataset is ATP-41 are shown in Table 6, whose training dataset is ATP-388. Moreover, we added the performance of our model PFDCNN, trained in ATP-1930. On dataset ATP-17 (Table 5), our model achieved the highest AUC, accuracy (Acc), specificity (Spe), and precision (Pre) scores. Specifically, the AUC, Acc, and Spe values were 0.965, 0.990, and 0.997, respectively. These results underscore the superior performance of the PFDCNN in predicting protein–ATP binding sites. By leveraging advanced feature extraction techniques and deep learning architectures, it achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple evaluation metrics, setting a new benchmark in the field. Moreover, on the ATP-41 dataset, as shown in Table 6, our model achieves an AUC of 0.941, an accuracy (Acc) of 0.984, and a specificity (Spe) of 0.999 when trained on the ATP-388 dataset. These metrics represent improvements of 1.8%, 1.2%, and 1%, respectively, over those of E2EATP, which also uses a pretrained protein language model as a feature extractor, demonstrating its robustness and accuracy across different test datasets.

Finally, to avoid the limitations and particularities of fixed partitioned datasets, we employed tenfold cross-validation to conduct experiments on two different training datasets, providing a comprehensive understanding of its performance. For each validation result, we calculated multiple evaluation metrics and ultimately used the average values of these metrics for the final assessment of the model’s performance. As shown in Table 7, on the training datasets ATP-227 and ATP-388, our model achieved average accuracy (Acc) values of 0.982 and 0.989, respectively, while the average area under the ROC curve (AUC) reached 0.933 and 0.950, respectively. The distribution of the tenfold cross-validation results is shown in Fig. 8. These results clearly demonstrate that our model exhibits excellent performance on both datasets, highlighting its robustness and generalizability. By leveraging cross-validation and rigorous evaluation, we ensured that the model is well suited for real-world applications in protein–ATP binding site prediction.

Discussion

The binding of ATP to proteins is intimately involved in the physiological regulation of the human body, and abnormal changes in the binding site is a key factor causing many major diseases. Taking cardiovascular diseases as an example, the binding of ATP to and dissociation of ATP from the head of myosin is the energy-driven basis for myocardial contraction and diastole. When the ATP binding site of myosin is mutated, myocardial contraction is abnormal, leading to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In this study, the PFDCNN model accurately predicted the ATP binding site, which can be used to identify key mutations at the early stage of diseases and provide an important basis for early diagnosis of diseases. In tumour therapy, protein kinases are important regulatory targets for tumour cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and their activities are highly dependent on ATP binding [22]. For example, the ATP binding site of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase region is the target of gefitinib and other targeted drugs [23], and the PFDCNN model can accurately predict the structural characteristics of the binding site, assisting drug developers in designing inhibitors with greater specificity and affinity, increasing drug efficacy, and reducing toxicity and side effects on normal cells. In addition, in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, abnormal binding of α-synuclein to ATP promotes protein misfolding and aggregation, which leads to neuronal death [24]. The use of this model to predict binding sites can aid in understanding the pathogenesis of diseases and provide theoretical support for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Currently, in protein–ATP binding site prediction, manual feature extraction-based models rely on researchers to manually construct features on the basis of biophysical and chemical properties (e.g., solvent accessibility and charge distribution), which is an empirically driven approach with significant drawbacks. On the one hand, the feature design process requires much time and expertise, and it is difficult to avoid subjective bias, resulting in redundant features or missing key information; on the other hand, the nonlinear and high-order interaction patterns in protein sequences are difficult to fully capture by manually designed features, which severely limits the performance of the models. Although end-to-end learning models can automatically extract features, they rely on large-scale deep learning architectures and consume massive amounts of computational resources during the training process, and their performance is highly dependent on high-quality labelled data. In practical research, datasets that meet these requirements are often difficult to obtain, which restricts their wide application.

The PFDCNN model proposed in this study achieves innovative breakthroughs in terms of several aspects. At the feature extraction level, the model takes the original protein sequence as input and automatically mines key information related to ATP binding with the help of pretrained models (e.g., ProtBert, ESM-1b and ESM-2), which is a process that is completely free from tedious manual feature engineering. A systematic comparison of the three pretraining models reveals that ESM-2 has the best performance in terms of all the evaluation indices, so it provides a valuable reference for the selection of pretraining models for subsequent studies. In terms of the optimization algorithm, the fractional order gradient method is introduced to replace the traditional integer order gradient descent algorithm to innovate the model optimization process from a mathematical perspective. Through detailed exploration of the fractional orders from 0.65 to 1.3, 0.9 is identified as the optimal fractional order, which significantly increases the optimization efficiency and prediction accuracy of the model. The experimental data show that on the two independent test datasets, the AUC indices of the PFDCNN model reach 0.965, 0.941 and 0.953, which are far better than those of the existing sequence-based prediction models, fully verifying its great advantage in terms of prediction accuracy. In terms of model architecture, in the innovative fusion of a pretrained model and a deep convolutional neural network, the former is responsible for advanced semantic feature extraction, and the latter completes feature abstraction and classification, which not only avoids the drawbacks of manual feature extraction but also reduces the dependence on large-scale data and achieves highly efficient and accurate prediction.

Despite the excellent performance of the PFDCNN model, there is still space for improvement. At the data level, the existing training dataset lacks species diversity, and there is a lack of samples of rare species and proteins with unknown functions, which limits the generalizability of the model when dealing with such data. In the model construction, only protein sequence information is used, but multimodal data such as 3D structure or dynamic conformation data are not integrated, which makes it difficult to completely portray the real characteristics of the binding site. Compared with the current state of research, although some studies have attempted to combine pretrained models and traditional deep learning architectures, there are still obvious gaps in terms of optimization algorithm innovation and model interpretability. For example, some studies follow traditional integer-order gradient optimization, which leads the models to fall into local optima; most models lack effective visualization and interpretation mechanisms, which makes it difficult for biologists to understand the prediction results. However, in the field of single-cell sequence analysis, many successful deep learning models and architectures are worthy of our study. Such as: a multiview graph attention network was used to infer gene regulatory network, which can simultaneously utilize local feature information and high-order neighbor feature information of nodes [26]. Moreover, Lan Ye et al., proposed a model based on attention autoencoder and zero-inflated layer to fully exploit cellular features [27]. Simultaneously, Wenzheng Bao et al. proposed a novel feature reconstruction method to analyze unilateral complete cleft lip [28]. All of these above methods provided us multiple approaches to integrate multimoding data sets to achieve higher accuracy prediction of binding sites. Therefore, future research can focus on constructing multimodal data fusion models, exploring adaptive adjustment strategies for fractional-order parameters, and strengthening the validation of the generality of the models in cross-species and cross-functional class protein prediction to further promote the technological development of this field.

Conclusion

This study proposes an innovative deep learning model, the PFDCNN, for the prediction of protein-ATP binding sites. The model combines protein pretrained language models and fractional order techniques, thus addressing the limitations of previous protein sequence-based prediction methods. These methods rely on time-consuming and cumbersome hand-crafted features, whereas structure-based methods are limited by the availability of accurate protein structural information, which is lacking for many proteins. The PFDCNN model overcomes these limitations by employing a protein pretrained language model as a feature extractor and utilizing only the raw protein sequence information as input, which eliminates the need for complex feature engineering. This approach enables the automatic generation of the feature embedding of protein sequences, effectively capturing key information related to ATP binding. In the feature processing stage, the PFDCNN employs a deep convolutional neural network to further process the features extracted from the pretrained model and outputs the classification probabilities. In addition, the incorporation of the fractional order technique within the backpropagation stage of the model has been demonstrated to enhance the generalization capability and flexibility of the model. Through a series of comparative experiments, the efficacy of the PFDCNN model for protein–ATP binding site prediction has been substantiated, resulting in a substantial increase in prediction accuracy compared with that in previous studies. These findings offer significant advancements in the field, providing researchers with a robust tool for protein–ATP binding site research and laying the foundation for future advancements in protein binding site prediction. Moving forwards, we aim to enhance the pretrained model and investigate alternative deep neural network models to further enhance prediction performance.

Data availability

The datasets and codes used and generated in this study are all available at [https://github.com/Yswangustb/PFDCNN].

References

Ahmad, S. & Sarai, A. PSSM-based prediction of DNA binding sites in proteins. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 33 (2005).

Wang, L. & Brown, S. J. BindN: A web-based tool for efficient prediction of DNA and RNA binding sites in amino acid sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W243–W248 (2006).

Chen, K., Mizianty, M. J. & Kurgan, L. Prediction and analysis of nucleotide-binding residues using sequence and sequence-derived structural descriptors. Bioinformatics 28(3), 331–341 (2012).

Yu, Y. et al. TargetATPsite: Predicting ATP-binding residues in proteins by sparse representation of residue evolutionary images and ensemble classifiers. Bioinformatics 30(14), i433–i440 (2014).

Fang, C., Noguchi, T. & Yamana, H. Simplified sequence-based method for ATP-binding prediction using contextual local evolutionary conservation. Algorithm Mol. Biol. 9(1), 7 (2014).

Song, J. et al. Prediction of protein-ATP binding residues based on ensemble of deep convolutional neural networks and LightGBM algorithm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(2), 939 (2021).

Chen, K., Mizianty, M. J. & Kurgan, L. ATPsite: Sequence-based prediction of ATP-binding residues. Proteome Science 9(Suppl 1), S4 (2011).

Yu, D.-J. et al. Improving protein-ATP binding residues prediction by boosting SVMs with random under-sampling. Neurocomputing 104, 180–190 (2013).

Hu, J., Li, Y., Zhang, Y. & Yu, D.-J. ATPbind: Accurate protein-ATP binding site prediction by combining sequence-profiling and structure-based comparisons. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 501–510 (2018).

Li, W. & Godzik, A. Cd-hit: A fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22, 1658–1659 (2006).

Rao, B., Yu, X., Bai, J. & Hu, J. E2EATP: Fast and high-accuracy protein-ATP binding residue prediction via protein language model embedding. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 64, 289–300 (2024).

Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 5998–6008 (2017).

Lin, Z., Akin, H. & Rao, R. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 379, 1123–1130 (2023).

Elnaggar, A., Heinzinger, M. & Dallago, C. ProtTrans: Toward understanding the language of life through self-supervised learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 7112–7127 (2021).

Devlin, J.: BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. ArXiv, arXiv:1810.04805 (2019).

Chen, Y. Q., Gao, Q., Wei, Y. H. & Wang, Y. Study on fractional order gradient methods. Appl. Math. Comput. 314, 310–321 (2017).

Sheng, D., Wei, Y., Chen, Y. & Wang, Y. Convolutional neural networks with fractional order gradient method. Neurocomputing 408, 42–50 (2020).

Lin, T.-Y., Goyal, P. & Girshick, R. B. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 318–327 (2020).

Guo, D., Yang, D., et al.: DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv,, arXiv:2501.12948v1 (2025).

Chen, B. P. et al. Fractional-order convolutional neural networks with population extremal optimization. Neurocomputing 477, 36–45 (2022).

He, Y. et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 425 (2021).

Murphrey, M.B., Quaim, L., Rahimi, N., et al.: Biochemistry, epidermal growth factor receptor. StatPearls Publishing (2025).

Calabresi, P. et al. Alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies: from overt neurodegeneration back to early synaptic dysfunction. Cell Death Dis 14, 176 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. KNN-based dynamic query-driven sample rescaling strategy for class imbalance learning. Neurocomputing 191, 363–373 (2016).

Yuan, L. et al. scMGATGRN: A multiview graph attention network–based method for inferring gene regulatory networks from single-cell transcriptomic data. Brief. Bioinform. 25(6), bbae526 (2024).

Yuan, L., Xu, Z., Meng, B. & Ye, L. scAMZI: Attention-based deep autoencoder with zero-inflated layer for clustering scRNA-seq data. BMC Genomics 26(1), 350 (2025).

Chen, B., Li, N. & Bao, W. CLPr_in_ML: Cleft lip and palate reconstructed features with machine learning. Curr. Bioinform. 20(2), 15 (2025).

Wu, J. S. et al. Prediction of protein-ATP binding residues using multi-view feature learning via contextual-based co-attention network. Comput. Biol. Med. 172, 108227 (2025).

Bai, J. et al. E2EATP: Fast and high-accuracy protein–ATP binding residue prediction via protein language model embedding. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 64(1), 289–300 (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 3161194).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and M.G. conceived and designed the graph network model and implemented the simulation study and real dataset analysis; J.Y. and Y.T. wrote the codes for the experiments; and Y.W. and Y.T. wrote the entire manuscript. All the authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take responsibility for it. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, M., Tu, Y., Yu, J. et al. Accurate prediction of protein–ATP binding sites based on a protein pretrained large language model and a fractional-order convolutional neural network. Sci Rep 15, 41886 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25830-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25830-7