Abstract

Many researchers have proposed empirical excavatability classifications to easily and quickly assess rock masses. These classifications mostly apply to surface excavations, while those for underground excavations are limited. Updating the classifications proposed for underground excavations based on new data is important in terms of eliminating the deficiencies in this regard. This study determined the engineering properties (RMR, Q, GSI), rock material strengths, and in-situ excavation classes of 16 underground rock masses. The new data were compared with excavation classifications from various researchers and empirical classes. The study found that empirical classifications for surface conditions are not applicable for underground. Excavation is more challenging in underground conditions due to stress from overburden. While excavation classes align for good to very good rock masses in both conditions, there is no perfect match for medium, weak, and very weak rock masses for underground. The study suggests that for underground excavation classes (blasting, hammer&blasting, hammer, and digging), both RMR89 and Q values should be used together to differentiate between classes. When using GSI for classification, the Is(50) value of the rock material should also be considered. The σcm parameter is the most critical in evaluating rock mass excavatability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Selection of correct and economical equipment and excavation method in both underground and surface excavations depend on rock mass excavatability. Therefore, accurate and reliable studies to determine the characteristics of the rock masses have a significant effect on the cost of engineering projects. Within their study over 158 tunnels in 35 countries, Efron and Read1 also stated that geology and the excavation costs constitute the biggest costs in tunneling. Effective geotechnical evaluation of rock masses and rock materials leads to determine the appropriate excavation type; thus, the excavation costs would probably reduce and, the problems encountered during excavation can be minimized.

Many researchers have developed various empirical classification systems based on rock material and rock mass properties to determine the rock mass excavatability2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Some researchers17,18,19,20,21 used the empirical classification systems in their scientific researches.

When these classifications are examined, it is seen that different input parameters that affect the excavatability of rock masses are preferred. In their study, Gurocak and Yalcin21 categorized the input parameters used in the classifications proposed by different researchers, which has a wide range of use and divided into three categories;

Category-A. Engineering properties of the discontinuities,

Category-B. Engineering properties of the rock material,

Category-C. Engineering properties of the rock mass.

Bailey4, Abdullatif and Cruden7, Hoek and Karzulovic14, Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 used the parameters in the Category-C for their classification systems while Franklin et al.2, Scoble and Muftuoglu8, Smith9, Pettifer and Fookes13 used the parameters of Category A and B. Also, the parameters of Categories A, B and C were used in the excavatability classifications proposed by Weaver5, Kirsten6, Karpuz12, Hadjigeorgiou and Poulin22 and Ceylanoglu et al.15.

Functional parameters in the empirical classifications are generally similar. Therefore, for the same rock mass, the results obtained from the classifications must be compatible with each other. However, apart from the compatible results, the significant differences between the excavation types in the classifications for the same rock mass suggests that the classifications have limitations and should be carefully used. Another important case is the discrepancies between the in-situ excavation class and the results of the empirical classifications for the same rock mass. These differences, which show up in practice, indicate that the proposed classifications are not always appropriate for every rock mass, and it is important to select the most appropriate empirical classification when classifying rock masses. It should be remembered that choosing the most suitable classification is only possible by comparing the results obtained from the empirical classifications to the in-situ excavatability class of rock masses that have different engineering characteristics21.

Furthermore, it is crucial to determine for which type of excavation work (surface or underground excavations) these empirical classifications are suitable. For instance, classifications proposed by researchers2,5,6,8,9,12,13,15,22 using parameters categorized by Gurocak and Yalcin21, specifically those in categories A and B along with parameters from all three categories, rely on data collected from engineering experiences conducted on the surface, such as highway slopes, open-pit mines, and foundation excavations. However, using these excavatability classifications, which only assess the excavatability of rock masses for surface conditions, makes it nearly impossible to reliably predict the excavatability class of the rock mass for underground excavations. On the other hand, the most well-known empirical classifications that utilize rock mass properties such as Rock Mass Rating (RMR), Geomechanics (Q), and Geological Strength Index (GSI) as classification parameters are those proposed by Abdullatif and Cruden7, Hoek and Karzulovic14, and Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 for excavatability assessments.

In the classification proposed by Abdullatif and Cruden7, researchers used the Q and basic RMR89 values of the rock masses and identified three excavation classes as Digging, Ripping and Blasting. For the surface excavations, digging represents the excavations carried out by excavator bucket while ripping represents the excavations carried out by bulldozer rippers and blasting represents the explosive used excavations.

Hoek and Karzulovic14 used the uniaxial compressive strength of the rock mass (σcm) and GSI values in the proposed classification method and identified three excavation classes as Digging, Ripping and Blasting.

Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 used the GSI chart suggested by Marinos and Hoek23 to identify excavation class of rock masses. In this excavatability classification, the researchers proposed two different GSI scales to evaluate the rock masses according to point load index (Is(50)) (for Is(50) ≥ 3 MPa and Is(50) < 3 MPa conditions).

While these classifications are effective for engineers and researchers to determine the excavatability class of rock masses in both slopes and underground excavations and provide a qualitative estimate of excavatability, it’s important to note that these empirical classifications are proposed using data collected from surface excavations and slopes. Therefore, when these classifications are used for underground excavations, there may be a mismatch between the in-situ excavation class and the excavation class suggested by these classifications. Two factors contribute to this mismatch: overburden pressure and weathering caused by external factors on the surface. The rock mass excavated underground is under pressure due to overburden. The aperture of discontinuities could be closer in underground due to overburden, whereas the aperture of the same discontinuities could not always be as closed as on the surface or could be open due to soil loosening, and the degradation on the surface is generally greater than that underground. Consequently, a rock mass with the same structure may require blasting for excavation underground, while it can be excavated on the surface using a hydraulic hammer or ripper, thanks to the differences in overburden pressure and surface degradation. Therefore, classifications created with data gathered from surface excavations cannot be reliably used for underground excavations. Goodman24 stated that increasing cover load enhances normal stress on discontinuity surfaces, preventing sliding along these surfaces and thus limiting displacements that may occur along the discontinuity. As a result, he noted that during excavation, it becomes more difficult for rock masses to detach from their natural fracture surfaces, requiring more energy for the excavation to proceed under optimal conditions.

A significant study on underground excavations was conducted by Chaniotis et al.25. The researchers proposed a classification chart based on the original GSI proposed by Hoek and Marinos23 that could be used for underground excavations, taking into account the GSI value of the rock mass and providing the following definitions for excavation classes based on excavatability.

-

a.

10 < GSI < 25, can be easily excavated.

-

b.

For 25 < GSI < 35, excavation is mostly performed using digging methods (94% in total), while in some cases, a combination of digging and hydraulic breaker (5%), or only a hydraulic breaker (1%) may be required.

-

c.

For 35 < GSI < 45, excavation is possible with all methods.

-

d.

For 45 < GSI < 55, excavation is mostly carried out (90%) using the blasting method. Only 9% can be excavated with a hammer (or occasionally with blasting), while only 1% is excavated using a combination of a digger and a hammer. The use of diggers in such rock masses is almost impossible.

-

e.

For, 55 < GSI < 65, excavation is performed solely through blasting, and excavatability in such rock masses is very difficult.

The researchers’ recommendations for the excavatability classifications of rock masses, taking into account not only the GSI value but also the Is(50) value in determining the excavatability class, are as follows:

-

a.

As Is (50) increases, a successful excavation performance requires low GSI values. For excavation by digging, the upper limit for GSI is 35–40, and in this case, Is (50) should be < 1 MPa.

-

b.

In cases where Is (50) < 1.3 MPa and GSI is between 45 and 60, the rock mass is expected to be excavatable by hammer. However, as Is (50) increases, GSI should be < 40 for the rock mass to be excavatable with a hammer.

-

c.

The applicability of blasting is determined by the σci and the average discontinuity spacing of the rock mass. When the Discontinuity Spacing Index (If) is approximately 0.1 m and σci is approximately 12 MPa, the lower limit of GSI value for excavation by blasting is 45. For the determined GSI is 60, If is approximately 0.4 m, and the minimum σci is about 10 MPa.

-

d.

Blasting is used over a wide range of GSI values depending on the strength of the intact rock. Specifically, if GSI > 45 and 3 MPa > Is (50)) > 1.3 MPa, blasting should be used for these rock masses. If Is (50) > 3 MPa, blasting should be used even for lower GSI values (even as low as 30).

In their conclusion, the researchers highlighted that the ease of excavating a rock mass with high strength tends to increase as the overall rock mass quality decreases, as indicated by lower GSI values. Consequently, they propose the use of hydraulic hammers and even excavation with diggers, including controlled blasting, to facilitate the excavation process. Despite the study conducted by Chaniotis et al.25 not considering the overburden load, its recommendation for underground excavations is crucial in addressing a significant gap in this field.

Considering the information above, it is evident that using data from surface excavations to apply recommended excavatability systems for realistic and practical excavatability assessments of rock masses may not yield accurate results for underground excavations. Therefore, addressing this significant gap in the field could involve updating existing excavatability classifications using newly obtained data and making them applicable for underground excavations.

The main objectives of this study can be outlined as follows:

-

a.

Comparing excavation classes determined by different empirical classifications of rock masses to identify the compatibility or discrepancies among existing excavatability classifications.

-

b.

Investigating the applicability of empirically suggested excavatability classifications based on surface studies to underground excavations, utilizing data from surface studies.

-

c.

Utilizing newly gathered data from underground excavations to review limit values/excavation classes of existing empirical excavatability classifications, making these classifications applicable for underground excavations.

Thus, it will be ensured that the excavatability classifications recommended for surface conditions can also be used for excavations in underground conditions, and the excavation limits of the excavatability classifications recommended for underground excavations will be reviewed on the basis of new data. As a result, it will be possible to safely determine excavation classes in underground excavations.

Geotechnical properties of the rock masses

In this study, 16 different rock masses (Table 1), whose formation and lithological properties were examined by different researchers18,21,26,27,28,29 (Gurocak et al.26; Gurocak et al.18, 2008; Gurocak and Yalcin21; Alemdag et al.27; Erdem29; Kanik and Gurocak29 were selected and were characterized by RMR89, Q and GSI classification systems by using the geotechnical information of the rock masses. In the study, rather than using excavation classifications obtained through empirical approaches, the real (in-situ) excavation types applied in the tunnel face have been used.

To characterize the rock masses, scan line method was used in accordance with the ISRM30 suggestions. This method involved studying the number of joints per meter and determining engineering properties of these discontinuities, such as spacing, aperture, persistence, infilling, roughness, weathering, and water condition.

The equation (Eq. 1) proposed by Priest and Hudson31 was used to determine the Rock Quality Designation (RQD) values of the rock masses.

where;

RQD: Rock quality designation,

λ: number of joints per meter.

The other two parameters necessary for the characterization of rock masses are uniaxial compressive strength of rock material (σci) and Is (50). These parameters were determined through experiments conducted on cores prepared from block samples obtained during tunnel excavation, following the ISRM32 recommendations.

In addition, uniaxial compressive strength of the rock masses (σcm) was calculated by the Eqs. (2–4) of Hoek et al.33.

where;

σci: Uniaxial compressive strength of the rock material (MPa),

s and a: Hoek-Brown constants,

D: Disturbance factor,

The values for the parameters used in the characterization of rock masses are given in Table 2.

RMR Classification System, an empirical rock mass classification system, was first developed by Bieniawski34 and modified by the recommendations made by Bieniawski35 on the determination of the parameters of the classification and the scores of these parameters, was lastly revised by Celada et al.36. In this study, the 1989 version of the classification was used due to its broad acceptance and determined basic RMR89 scores of the rock masses.

The Q classification system, also known as NGI (Norwegian Geotechnical Institute) system, was proposed by Barton et al.37 and revised by Grimstad and Barton38, while the SRF (Stress Reduction Factor) and ESR (Excavation Support Ratio) parameters were rearranged by Barton and Grimstad39. Q value is calculated by the equation given below.

where;

RQD: Rock quality designation,

Jn: Joint set number,

Jr: Joint roughness number,

Ja: Joint alteration number,

Jw: Joint water reduction factor,

SRF: Stress reduction factor.

In this study, the RMR89 and Q values for rock masses have been calculated, and the results are presented in Table 3.

GSI, which was proposed by Hoek et al.40 and used to determine the rock mass constants (mb, s and a) by replacing RMR in the Hoek-Brown Failure Criteria, was initially associated with RMR and Q classification scores. The GSI was transformed into a system that is independent of the RMR and Q systems with the revisions made by Hoek and Brown41. GSI classification system consists of a chart that uses four rock groups: blocky, very-blocky, blocky/disturbed and seamy. After the recommendation of GSI as a classification system, Marinos and Hoek23 proposed a new classification of intact or massive rock group with foliation or lamination planes to the GSI classification. In the following years, Marinos and Hoek42, Marinos et al.43 and Hoek et al.44 revised the GSI system in their studies and proposed the version of the system used today.

The last study on the prediction of GSI was reported by Hoek et al.44. The researchers suggested some equations for GSI prediction. In this study, the GSI values of the rock masses were determined according to Eq. (6) proposed by Hoek et al.44 and the calculated GSI values of rock masses were given in Table 3.

Where;

GSI: Geological Strength Index.

JCond89: RMR89 joint condition rating.

Simple regression analyses have been performed to determine the relationships between the parameters RMR89, Q, GSI, and σcm that characterize the rock masses. The distribution graphs and correlation coefficients (R) for these analyses were presented in Fig. 1. According to the regression analyses, the R values ranged from 0.63 to 0.94. Very strong correlations exist between the parameter pairs rcm-RMR89, σcm-GSI, GSI-RMR89, and Q-GSI, while the correlations between the parameter pairs σcm-Q and Q-RMR89 are moderate.

One-way ANOVA tests were conducted to determine whether the correlations between σcm ile RMR89, Q and GSI parameters are statistically significant. The results of the ANOVA test are provided in Table 4.

According to the results of the ANOVA test, since the F value (128.99) > F critical (2.76), the null hypothesis (H0) is rejected, and with p < 0.05, it can be concluded that there is a statistically significant difference between the groups. This result indicates that the means of at least one group are significantly different from the others. To determine which groups have significant differences, a post-hoc test (Tukey’s HSD) has been applied (Table 5).

Tukey’s HSD results indicate that there is no statistically significant difference between Group-1 and Group-3, as well as between Group-2 and Group-4. However, significant differences were found in all other combinations (1–2, 1–4, 2–3, 3–4). The one-way ANOVA analysis revealed statistically significant differences between the groups (F = 128.99, p < 0.001). Following this result, the Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test showed that the groups can be divided into two clusters: Group 1 and Group 3 exhibited similar values, while Group 2 and Group 4 were also similar to each other but significantly different from the other two groups.

Determination of in-situ excavation classes of rock masses

In previous studies on the excavability of rock masses in surface and underground conditions, excavability classes were defined as digging, ripping, hammer, hammer&blasting and blasting. The in-situ excavation classes are defined as blasting, hammer & blasting, hammer, and digging in this study. For the underground conditions, digging represents the excavations carried out by the breaker of the excavator without hydraulic power. Hammer represents the excavation carried out by the hydraulic breaker of the excavator and blasting represents the explosive used excavations. The excavation class referred to as “ripping” for surface excavations is defined as “hammer” for underground excavations in this study. This adjustment is made because, technically, using a ripper for excavations in underground conditions is not feasible.

The methods used in the excavations carried out in 16 different rock masses in different projects were followed and the excavation classes of these rock masses were determined on site. Images of rock masses in different excavation classes during the excavations are given in Fig. 2, and in-situ excavation classes of rock masses are given in Table 6.

Assessment of rock masses based on empirical excavatability classifications

In this study, the excavation classes of the investigated rock masses were initially assessed by excavation classifying systems based on RMR, Q, σcm, and GSI those were proposed by Abdullatif and Cruden7, Hoek and Karzulovic14, Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 and Chaniotis et al.25. The in-situ excavation classes, determined through field studies of rock masses, were then compared with the outcomes of empirical classifications to assess their applicability for underground excavations.

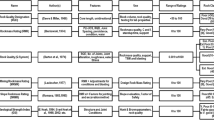

The excavatability classification of Abdullatif and Cruden7

The first empirical excavatability classification based on rock mass properties was proposed by Abdullatif and Cruden7, utilizing Q and basic RMR values. Researchers have suggested excavation classes as follows: digging for RMR < 30, ripping for 30 < RMR < 60, and blasting for RMR > 60. However, they noted that the relationships between rock mass Q values and excavatability are not highly consistent, revealing significant gaps between Q values for digging and ripping excavation classes. To address this deficiency, they emphasized the need for additional data. Additionally, an overlap is mentioned for rock masses with Q values of 3.2 and 5.2 in the ripping and blasting excavation classes. Considering the limit values provided by the researchers, the excavation classes and limit values are as presented in Table 7.

The rock masses in this study have been evaluated according to the excavatability classification proposed by Abdullatif and Cruden7, and the results are presented in Fig. 3.

Evaluation of the rock masses according to the excavation classification proposed by Abdullatif and Cruden7.

According to the Abdullatif and Cruden7 excavatability classification, the Codes 1, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10 ,12 and 16 are excavatable by ripping while the Codes 4, 5, 6, 11, 13 and 15 are excavatable by blasting (Fig. 3). The excavation classes of rock masses categorized as Codes 2 and 14 are determined as ripping based on RMR values. According to the Q values, it has been identified that two different excavation classes can be applied to each code. According to the Q value, the excavation class of Code 2 rock mass is digging or ripping, while the excavation class of Code 14 rock mass is ripping or blasting.

The excavatability classification of Hoek and Karzulovic14

In this classification, rock masses are divided into three excavatability classes: digging, ripping, and blasting. The limit values for these excavatability classes are as provided in Table 8.

Upon assessing the GSI and σcm values of rock masses are evaluated according to the limit values provided in Table 8, rock masses with Codes 2 and 10 drop to the digging excavatability class, rock masses with Codes 1, 7, 8, 9, and 12 drop to the ripping excavatability class, and rock masses with Codes 3, 4, 5, 6, and 15 drop to the blasting excavatability class.

According to the limits in Table 8, for the Codes 11, 13, 14 and 16, two different excavation classes were obtained. It is because of the unfitting of the parameters considering the range of GSI and σcm. In other words, GSI value fits to the range of an excavation class and the σcm value fits to the range of the other excavation class.

The excavatability classification of Tsiambaos and Saroglou16

The excavatability classification system proposed by Tsiambaos and Saroglou16, uses the GSI chart proposed by Marinos and Hoek23. The researchers proposed two different GSI scales to evaluate the rock masses according to Is(50) ≥ 3 MPa and Is(50) < 3 MPa conditions (Fig. 4) different excavatability classes as blasting, hammer&blasting, ripping and digging.

The GSI values of the rock masses were determined according to Marinos and Hoek23, while the Is(50) values were determined based on the method proposed by ISRM32. In this method, Is(50) is calculated using the equation provided below:

Where;

De: Equivalent core diameter (mm).

P: Failure load (N) .

The corrected point load index (Is(50)) is calculated using the following equation .

Where,

F: Size correction factor.

In accordance with the established classification, the excavatability class assigned to Code 2 rock masses is categorized as digging, while Codes 7, 8, 9, 10, and 12 rock masses are classified as ripping. Code 1 rock masses fall under the category of hammer & blasting, and Codes 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 13, 14, 15, and 16 rock masses are designated as blasting, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Evaluation of the rock masses according to the excavatability classification system proposed by Tsiambaos and Saroglou16.

The excavatability classification of chaniotis et al. 25

In the empirical excavatability classification proposed by Chaniotis et al.25 for underground excavations, the GSI value of the rock mass is taken into consideration. Utilizing the GSI range suggested by Marinos and Hoek23, the researchers recommended four excavation classes: blasting, hammer & blasting, digging & hammer, and digging. Upon evaluating the rock masses in this study based on the excavatability classification suggested by Chaniotis et al.25, the empirical excavation class for the rock mass with Code 2 is determined as digging, for Code 10 as digging & hammer, for Codes 7 and 9 as hammer & blasting, and the remaining 12 rock masses are classified as blasting (Fig. 5).

Evaluation of the rock masses according to the excavatability classification system proposed by Chaniotis et al.25

Comparison of emprical and in-situ excavation classes of rock masses

After determining the in-situ and empirical excavation classes of 16 different rock masses examined in this study, the in-situ and empirical excavation classes obtained are given in Table 9, and these excavation classes were compared in order to determine how compatible the empirical and in-situ excavation classes of rock masses are.

Comparison of empirical excavation classes of rock masses

As seen in Table 9, the excavation classes for the rock masses, based on data collected from the surface excavations, are as digging and ripping and generally align with the empirical classifications proposed by Abdullatif and Cruden7, Hoek and Karzulovic14, and Tsiambaos and Saroglou16. For instance, the rock masses coded as 7, 8, 9, and 12 are classified as ripping. For the rock mass coded as 2, Abdullatif and Cruden7 suggest ripping or digging, while Hoek and Karzulovic14 and Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 suggest digging. The excavation class for the rock mass coded as 1 is ripping according to Abdullatif and Cruden7 and Hoek and Karzulovic14, while Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 propose the excavation class for harder rock masses, Hammer&Blasting. A similar situation is observed for the results of the rock masses coded as 14 and 16. The most notable observation here is that the rock masses coded as 3, 4, 5, 6, and 15 are classified as blasting considering the excavation class in all three empirical classification systems. The common characteristics of these rock masses are; having good-very good rock mass properties, GSI values greater than 69, basic RMR89 values greater than 59, Q values greater than 1.5, and σcm values greater than 17 MPa. Hence, when a rock mass exhibits GSI > 69, RMR > 59, Q > 1.5, and σcm > 17, the excavatability of the mentioned rock mass can be assessed empirically within the blasting class.

In comparing the excavation class results suggested by Chaniotis et al.25 based on underground excavation data with the other empirical classification, it is noteworthy that the excavation classes of rock masses coded as 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 15 overlap, whereas for the remaining rock masses, the empirical excavation classes are one level harder. For instance, while other classifications categorize rock masses coded as 1, 7, 8, 9, and 12 as ripping, Chaniotis et al.25 classifies these rock masses as blasting or hammer&blasting. The GSI values for these rock masses range from 40 to 56.5, RMR values from 38 to 59, Q values from 1 to 4.08, and σcm values from 0.15 to 3.56 MPa. The difference of “providing one level harder excavation class than the others” of the empirical excavation class of the rock masses according to the Chaniotis et al.25 classification can be attributed to the fact that the classification was proposed based on underground excavation data.

In the overall assessment of empirical findings, it is generally observed that the excavation classes proposed for the surface excavations largely overlap, but the alignment of classifications recommended for underground excavations of the same lithology with the surface excavation type cannot be asserted to be acceptable. Consistent results are obtained as better the rock mass class is in underground excavations, but there is not a complete alignment when the rock mass class gets weaker. This lack of alignment is attributed to the increasing difficulty of rock excavation due to the in-situ stresses related to overburden. As a result, the excavation classes suggested by Abdullatif and Cruden7, Hoek and Karzulovic14 (2000), and Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 correspond to the upper excavation class for the underground excavations.

Comparison of empirical and in-situ excavation classes of rock masses

The accuracy of empirical excavation classes for rock masses can only be determined through a comparison between empirical excavation classes and in-situ excavation classes. In this study, the in-situ excavation class of the 16 rock masses that constitute the database was determined during tunnel excavation (Table 9) and compared with empirically determined excavation classes. As seen in Table 9, according to the classification of Abdullatif and Cruden7, the excavation classes of rock masses coded as 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 13, and 15 are consistent with both empirical and in-situ classifications, and they are categorized as blasting. The situation is similar for rock mass Code 10, with the excavation class being hammer (for surface ripping). However, there are differences in other excavation classes. Indeed, for rock masses coded as 1, 14, and 16, which have an empirical excavation class of ripping, their in-situ excavation class is blasting. The in-situ excavation class for rock masses coded as 7, 8, 9, and 12, with an empirical excavation class of digging/ripping, is hammer&blasting. As for the rock mass Code 2, with an empirical excavation class of digging/ripping, the in-situ excavation class is digging.

According to the classification of Hoek and Karzulovic14 rock masses coded as 3, 4, 5, 6, and 15 can be excavated by blasting, as it is same for the in-situ excavation classes. There is a complete alignment for rock mass Code 2, where both the empirical and in-situ excavation classes are digging. However, for rock mass Code 1, with the empirical excavation class being ripping, its in-situ excavation class is blasting, and for rock masses coded as 7, 8, 9, and 12, with the empirical excavation class being ripping, the codes’ in-situ excavation class is hammer&blasting. The in-situ excavation classes for rock masses coded as 11, 13, 14, and 16, with the empirical excavation class being ripping&blasting, are determined as blasting. While the empirical excavation class for rock mass Code 10 is digging, its in-situ excavation class is determined as hammer.

According to the evaluation based on another empirical classification proposed by Tsiambaos and Saroglou16, for the rock masses coded as 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 13, 14, 15, and 16, with the empirical excavation class being blasting, their in-situ excavation classes are also blasting, and the excavation classes are fully compatible. For the rock mass Code 2, both the empirical and in-situ excavation classes are similar and are digging. The in-situ excavation class for the rock mass Code 10, with the empirical excavation class being ripping, is hammer; and for the rock masses coded as 7, 8, 9, and 12, the codes’ in-situ excavation class is hammer&blasting. For the rock mass Code 1, while the empirical excavation class is hammer&blasting, the in-situ excavation class is blasting.

It is observed that the in-situ excavation classes of the rock masses are more consistent with the classification suggested by Chaniotis et al.25 for underground excavations rather than with other empirical classifications. Especially for the rock masses coded as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 13, 14, 15, and 16, both the in-situ and empirical excavation classes are blasting, indicating a complete alignment. However, for the rock masses coded as 7, 8, 10, and 12, the relationship between the empirical excavation class and the in-situ excavation class is either one level lower or one level higher based on the characteristics of the rock mass. For example, while the empirical excavation class for the rock masses coded as 8 and 12 is blasting, the codes’ in-situ excavation classes are hammer&blasting. For rock mass Code 10, with the empirical excavation class being digging&hammer, its in-situ excavation class is hammer.

In a general assessment, it can be stated that a consistency exists between empirical and in-situ excavation classes for good-very good (partly fair) rock masses in both surface and underground conditions. This consistency extends to very weak rock masses as well. However, for weak and fair rock masses, the consistency between empirical and in-situ excavation classes cannot be conclusively asserted. Specifically, for a rock mass with the excavation class ripping for surface conditions, the excavation class in underground excavations corresponds to blasting, hammer&blasting, or hammer for the same rock mass. In other words, the excavation class of a rock mass for underground is in upper level than the surface excavation class of the same rock mass.

Evaluation of in-situ excavation classes, rock mass properties and strength

The findings of this study reveal that there is not a perfect consistency between empirical excavation classes and in-situ excavation classes. Moreover, it is observed that several existing empirical classification systems designed for surface excavations lack reliability when applied to underground excavation scenarios. Consequently, there is a need to systematically assess the correlations between in-situ excavation classes and rock mass properties. This is particularly important in light of newly acquired data. Furthermore, it is imperative to reconsider the limit values of empirical excavatability classifications based on the obtained results.

The study has investigated the relationships between rock mass properties, namely GSI, basic RMR89, and Q values, and their associations with in-situ excavation classes. The outcomes of these evaluations are comprehensively presented in Table 10.

According to the limit values provided in Table 10, the parameter that best defines excavation classes is GSI. Considering the GSI value of the rock mass and the structure/surface condition features, when GSI > 55 and for good-very good/blocky-massive rock mass, the excavation class is blasting; when 40 < GSI < 55 and for fair-poor/blocky-very blocky rock mass, the excavation class is hammer&blasting; when 30 < GSI < 40 and for poor/very blocky rock mass, the excavation class is ripping; and when GSI < 30 and for poor-very poor/blocky disturbed seamy rock mass, the excavation class is digging. In the evaluation of RMR89 and Q values, in contrast to GSI, it is evident that there lacks a detailed and inclusive correspondence encompassing all excavation classes. Specifically, for the good-very good rock mass class, corresponding to basic RMR89 > 55, the excavation class is blasting; for the fair rock mass class with 40 < basic RMR89 < 55, the excavation class is hammer&blasting; for the poor-very poor rock mass class and basic RMR89 < 40, the excavation class is either hammer or digging, and it is not clear which basic RMR89 value corresponds to the boundary that distinguishes these two excavation classes.

The evaluation based on the Q value reveals a parallel scenario to that observed with the basic RMR89. For Q > 1 (poor/fair/good rock class), the excavation class comprises either blasting or hammer&blasting, for 1 > Q > 0.2 (very poor rock class), it is hammer, and for Q < 0.2 (extremely poor-exceptionally poor), it is digging. It is noteworthy that, upon consideration of the basic RMR89 and Q values of rock masses, it is not possible to provide upper and lower limit values for the excavation classes of blasting and hammer&blasting, as well as for hammer and digging.

Although it may seem possible to determine excavation classes by considering the GSI value, the crucial point not to be overlooked is the impact of rock material strength (σci or Is (50)) over the excavatability of the rock mass. In numerous studies on excavatability and in various excavation classifications, it is emphasized that when determining the excavation class, not only rock mass properties such as GSI, RMR, or Q but also the strength of the rock material or mass should be taken into account.

In this study, when the in-situ excavation classes of rock masses are compared with Is (50) and σcm values, it is observed that Is (50) alone cannot define the excavation class (Table 2), but σcm values can be a parameter used for excavation classes (Table 11). Indeed, Hoek and Karzulovic14 have used σcm as a parameter in their proposed excavatability classification based on the σcm and GSI values of the rock mass. According to the results of this study, it is possible to determine the excavation classes of rock masses based on σcm values.

As in the classification proposed by Tsiambaos and Saroglou16, when the GSI and Is(50) values are evaluated together, the excavation classes and limit values are as shown in Table 12.

From the Table 12, it is observed that as the strength of the rock material increases for excavation classes such as blasting, hammer&blasting, and hammer, the GSI value should be lower to be able to use the same excavation class. In other words, for a rock mass with Is(50) ≥ 3 MPa and GSI = 60, blasting is required, whereas if Is(50) < 3 MPa, the excavation class becomes hammer&blasting. Therefore, two parameters work together and to be able to perform same excavation type, either the strength should increase as GSI decreases or the strength should decrease as GSI increases. In the condition GSI < 30, the excavation class is digging for all rock masses regardless of strength.

Conclusions

In this study, the excavatability of rock masses has been assessed for underground excavations using empirical and in-situ excavation data. The excavatability classification systems previously proposed by different researchers, including Abdullatif and Cruden7, Hoek and Karzulovic14, and Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 for surface excavations, as well as those proposed by Chaniotis et al.25 for underground excavations, have been reevaluated with new data. As a result of the conducted evaluations, it has been determined that, despite the general compatibility among the classifications proposed for surface conditions, they do not accurately reflect the excavation classes in underground excavations. For instance, a rock mass classified as ripping in the empirical classifications of Abdullatif and Cruden7, Hoek and Karzulovic14, and Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 is observed to be classified as hammer&blasting or hammer for underground conditions. In other words, transitioning from surface to underground conditions results in upper class of excavation, even though the geotechnical properties remain unchanged. This is attributed to the compression regime in the rock mass induced by stresses from overburden, leading to the closure of discontinuities and an increase in the shear strength of the discontinuities, resulting in increased excavation difficulty. Therefore, the upper and lower limit values of excavation classes from the proposed empirical classifications for surface conditions will not be applicable to underground excavations. It has been identified that a reassessment of these values is needed using data compiled from underground conditions.

In this study, rock mass characteristics, rock material strengths, excavations performed in tunnels, and in-situ excavation classes were determined. The obtained data were used to re-evaluate the limit values for excavation classes, as shown in Tables 10, 11 and 12.

In the process of determining the excavation class of the rock mass using solely basic RMR89 or Q values, the clear limit of the boundaries among the four primary excavation classes, ranging from digging to blasting based on excavation difficulty, poses a challenge. Indeed, assessing the excavation class of the rock mass using only the basic RMR89 value fails to differentiate between the digging and hammer excavation classes, while using the Q value does not allow distinguishing between the blasting and hammer&blasting excavation classes (Table 10). However, through the combined usage of basic RMR89 and Q values, the determination of the excavation classes for underground rock masses becomes feasible. As illustrated in Table 13, for basic RMR89 > 55 and Q > 1, the excavation class is defined as blasting; for 40 < basic RMR89 < 55 and Q > 1, it is hammer&blasting; for basic RMR89 < 40 and 1 > Q > 0.2, it is hammer; for basic RMR89 < 40 and 0.2 < Q, it is defined as digging.

When only the σcm value is used as a defining parameter, it is possible to represent all excavation classes, and the rock mass can be classified into four excavation classes in terms of excavatability. This is because both the strength of the rock material (σci) and the GSI value are utilized in the calculation of this parameter (Eqs. 2, 3, and 4). Thus; the excavation class is actually determined based on GSI and σci values. In Table 11, σcm values defining the blasting, hammer&blasting, hammer, and digging excavation classes are provided.

The predominant parameter for determining the excavation classes of rock masses is GSI. Nevertheless, research suggests that assessing the excavatability of rock masses solely based on the GSI value is inadequate, and the rock material’s strength should also be taken into consideration. Consequently, Tsiambaos and Saroglou16 incorporated the Is (50) value when using the GSI value to delineate excavation classes, establishing lower and upper limit values for excavation classes under the conditions of GSI value Is(50) ≥ 3 MPa and Is(50) < 3 MPa. In this study, the GSI values of rock masses were reassessed for underground conditions, considering the conditions of Is(50) ≥ 3 MPa and Is(50) < 3 MPa, and the obtained results are detailed in Table 13.

With the new data obtained from this study, the redefined limit values for excavation classes in underground conditions are presented in Table 13. These values take into account rock mass properties such as RMR89 and Q, as well as σcm and GSI values, along with in-situ excavation classes. Engineers can use these values to determine the excavation classes of rock masses in underground excavations. However, it is essential to note that the excavation classes and limit values provided in Table 13 may undergo reassessment with the addition of new data. This process can contribute to the development of more reliable excavatability classifications specifically tailored for underground conditions.

Also, this study has been conducted using data from a limited number of rock masses to determine the excavation classes of rock masses in underground excavations, which can be considered a significant gap in the literature. In this way, an important gap has been partially addressed. Further studies should be conducted on this topic, and the results of this study will provide a valuable database for future research.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Efron, N. & Read, M. Analysing International Tunnel Costs: an Interactive Qualifying Project (Report, 2012).

Franklin, J. A., Broch, E. & Walton, G. Logging the mechanical character of rock. Trans. Institution Min. Metall. 80A, 1–9 (1971).

Atkinson, T. Selection of open-pit excavating and loading equipment. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. 80, 101–129 (1971).

Bailey, A. D. Rock types and seismic velocities versus rippability. Highway Geology Symposium, Proceedings. 135–142 (1975).

Weaver, J. M. Geological factors significant in the assessment of rippability. Civil Eng. South. Afr. 17, 313 (1975).

Kirsten, H. A. D. A classification system for excavation in natural materials. Civil Eng. South. Afr. 24, 293–308 (1982).

Abdullatif, O. & Cruden, D. M. The relationship between rock mass quality and ease of excavation. Bull. Int. Assoc. Eng. Geol. 183–187 (1983).

Scoble, M. J. & Muftuoglu, Y. V. Derivation of a diggability index for surface mine equipment selection. Min. Sci. Technol. 1, 305–322 (1984).

Smith, H. J. Estimating rippability of rock mass classification. In: The 27th U.S Symposium on Rock Mechanics, Proceedings. University of Alabama. 443–448 (1986).

Singh, R. N., Denby, B. & Egretli, I. Development of a new rippability index for Coal Measures excavations. In: Proceedings of the 28th U.S. Symposium on Rock Mechanics Tucson, AZ. (1987).

Bozdag, T. Indirect rippability assessment of coal measure rocks. MSc Thesis. (1988).

Karpuz, C. A classification system for excavation of surface coal measures. Min. Sci. Technol. 11, 156–163 (1990).

Pettifer, G. S. & Fookes, P. G. A revision of the graphical method for assessing the excavatability of rock. Q J Eng Geol.144–164 (1994).

Hoek, E. & Karzulovic, A. Rock mass properties for surface mines. slope stability in surface mining. society for mining, Metallurgical and Exploration (SME), 59–70 (2000).

Ceylanoglu, A., Gul, Y. & Akin, A. Kazılabilirlik ve riperlenebilirlik sınıflama Sistemlerinin incelenmesi ve Yeni Bir sınıflama Sisteminin önerilmesi. Madencilik Dergisi. 46 (2), 13–27 (2007).

Tsiambaos, G. & Saroglou, H. Excavatability assessment of rock masses using the geological strength index (GSI). B Eng. Geol. Environ. 69 (1), 13–27 (2010).

Kentli, B. & Topal, T. Assessment of rock slope stability for a segment of the Ankara-Pozanti motorway. Turk. Eng. Geol. 74 (1e2), 73–90 (2004).

Gurocak, Z., Alemdag, S. & Zaman, M. M. Rock slope stability and excavatability assessment of rocks at the Kapıkaya dam site, Turkey. Eng. Geol. 96, 17–27 (2008).

Alemdag, S., Kaya, A., Gurocak, Z. & Dag, S. Excavatability properties of rock masses having different weathering degrees: an example of Gumushane Granitoid, Gumushane, NE Turkey. J. Geol. Eng. 35 (2), 133–149 (2011).

Kaya, A., Bulut, F. & Alemdag, S. Applicability of excavatability classification systems in underground excavations: a case study. Sci. Res. Essays. 6 (25), 5331–5341 (2011).

Gurocak, Z. & Yalcin, E. Excavatability and the effect of weathering degree on the excavatability of rock masses: an example from Eastern Turkey. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 118, 1–11 (2016).

Hadjigeorgiou, J. & Poulin, R. Assessment of ease of excavation of surface mines. J. Terramechanics. 35, 137–153 (1998).

Marinos, P. & Hoek, E. ‘GSI: A geologically friendly tool for rock mass strength estimation’, In: GeoEng2000: An International Conference on Geotechnical & Geological Engineering, International Society for Rock Mechanics, Melbourne.1422–1442 (2000).

Goodman, R. E. Introduction to Rock Mechanics. 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., New York, 562 p (1989).

Chaniotis, N., Saroglou, H. & Tsiambos, G. Excavatability of Rock Masses in Tunneling. 7th International Symposium on Tunnels and Underground Structures in SEE 2017, Sheraton, Zagreb, Croatia, (2017).

Gurocak, Z., Pranshoo, S. & Zaman, M. M. Empirical and numerical analyses of support requirements for a diversion tunnel at the Boztepe dam site, Eastern Turkey. Eng. Geol. 91, 194–208 (2007).

Alemdag, S., Gurocak, Z., Solanki, P. & Zaman, M. M. Estimation of bearing capacity of basalts at Atasu dam Site, Turkey. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 67 (1), 79–85 (2008).

Erdem, O. Yoncalı Barajı (Malatya) İsale Tüneli Güzergâhindaki Kaya Kütlelerinin Kazilabilme Özellikleri. MSc. Thesis (in Turkish). (2018).

Kanik, M. & Gurocak, Z. Importance of numerical analyses for determining support systems in tunneling: A comparative study from the Trabzon-Gumushane tunnel, Turkey. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 143, 253–265 (2018).

ISRM (International Society for Rock Mechanics). Suggested methods for the quantitative description of discontinuities in rock masses. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 16 (2), 22 (1978).

Priest, S. D. & Hudson, J. A. Discontinuity spacing in rock. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 13, 135–148 (1976).

ISRM (International Society for Rock Mechanics). The complete ISRM suggested methods for rock characterization. In: Ulusay R, Kazan Hudson JA (Eds.), Testing and Monitoring. Offset Press, Ankara; (2007). 628 s.

Hoek, E., Carranza-Torres, C. T. & Corkum, B. Hoek-Brown failure criterion-2002 edition. In: Proceedings of the 5th North American Rock Mechanics Symposium, 267–273 (2002).

Bieniawski, Z. T. Engineering classification of jointed rock masses. Trans. South. Afr. Institution Civil Eng. 15, 335–344 (1973).

Bieniawski, Z. T. Engineering Rock Mass Classifications 238 (Wiley, 1989).

Celada, B., Tardaguila, I., Varona, P., Rodriguez, A. & Bieniawski, Z. T. Innovating Tunnel Design by an Improved Experience-based RMR System (World Tunnel Congress, 2014).

Barton, N., Lien, R. & Lunde, J. Engineering classification of rock masses for the design of tunnel support. Rock. Mech. 6, 189–239 (1974).

Grimstad, E. & Barton, N. Updating The Q-System for NMT, International Symposium on Sprayed Concrete-Modern Use of Wet-Mix Sprayed Concrete for Underground Support, May, Norwegian Concrete Association, Oslo, Proceedings book, 44–66 (1993).

Barton, N. & Grimstad, E. The Q-System following Twenty years of application in NTM support selection. Geomechanic Colloquy. 6 (94), 428–436 (1994).

Hoek, E., Kaiser, P. K. & Bawden, W. F. Support of Underground Excavations in Hard Rock (Balkema, 1995).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. T. Practical estimates of rock mass strength. Int J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci Geomech. Abstr. 27 (3), 227–229 (1997).

Marinos, P. & Hoek, E. Estimating the geotechnical properties of heterogeneous rock masses such as flysch’. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 60, 85–92 (2001).

Marinos, P., Marinos, V. & Hoek, E. Geological strength index (GSI). A characterisation tool for assessing engineering properties for rock masses. In: (ed Romana, Perucho, O.) Underground Works Under Special conditions., Lisbon. 13–21. (Taylor and Francis, (2007).

Hoek, E., Carter, T. G. & Diederichs, M. S. Quantification of the Geological Strength Index chart. 47th US Rock Mechanics and Geomechanics Symposium. San Francisco, USA. (2013).

Funding

This study has been supported by the Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University Development Foundation (Grant number: 02025007001587).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.G.: Conceptualization, validation, writing—original draft preparation, project administration. M.K. and S.A.: methodology, data curation, supervision, investigation. A.K.: Visualization, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gurocak, Z., Kaya, A., Kanik, M. et al. Re-evaluation of excavation class limits for underground excavations based on new data. Sci Rep 15, 41731 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25859-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25859-8