Abstract

Air quality significantly impacts public health, industrial stability, and timely responses to environmental hazards, all of which are essential for sustainable development. Accurate forecasting of the Air Quality Index (AQI) is therefore crucial for effective environmental monitoring and management. In this study, we develop a hybrid deep learning model that integrates a Transformer encoder with a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) network. The model is trained and validated using daily air quality data collected from Shijiazhuang, Beijing and Tianjin, spanning November 2013 to February 2025. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed Transformer-BiLSTM model delivers stable and reliable predictive performance, with root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 3.0012 ug/m\(^3\), 1.7928 ug/m\(^3\), and 3.3646%, respectively. Compared with conventional baseline models, the hybrid model improves accuracy and generalization capability. This approach offers a reliable and interpretable tool for AQI forecasting and provides quantitative support for data-driven air pollution control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and significance

Air pollution has emerged as one of the most pressing global environmental challenges of the 21st century, with far-reaching implications for public health, economic development, and ecological sustainability. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 7 million premature deaths annually are attributable to the combined effects of ambient and household air pollution, positioning air quality management as a critical public health priority worldwide. The United Nations Environment Programme has consequently called upon all nations to implement comprehensive strategies to reduce air pollution and improve air quality standards.

With the rapid advancement of urbanization and industrialization, the surge in energy consumption and the continuous rise in motor vehicle ownership have led to a significant increase in the emission of air pollutants, and the concentration of PM2.5, O3 and other pollutants has exceeded the standard for a long period of time, which is a serious threat to the health of the residents and restricts the sustainable development of the city1. PM2.5, as the core component of the haze, not only damages the respiratory system and cardiovascular function, but also causes great social and economic losses by reducing visibility and affecting the traffic efficiency2. Air quality forecasting can be traced back to around the 1940s, when several developed countries began conducting research on pollution trend prediction. Accurate air quality prediction is a key prerequisite for the development of pollution prevention and control strategies and the assessment of health benefits, but the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of pollutant concentrations, and the complex coupling effects of meteorological conditions and regional transport make the traditional prediction models face serious challenges.

The Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, serving as the primary focus of this study, represents a particularly compelling case for air quality research. According to the China Ecological Environment Status Bulletin issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the annual average PM\(_{2.5}\) concentration in this region frequently exceeded twice the National Ambient Air Quality Standard (35 \(\mu\)g/m\(^3\)) during the 2013–2020 period. Epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated that such elevated pollution exposure levels constitute a significant environmental risk factor, contributing to increased incidence and severity of cardiovascular diseases, respiratory disorders, and various other health complications.

Evolution of AQI prediction methodologies

The historical development of air quality prediction methodologies reveals a progressive evolution from physically-based models to increasingly sophisticated data-driven approaches. Initial research efforts in the 1940s primarily focused on numerical methods rooted in atmospheric dynamics and environmental chemistry, which attempted to simulate pollutant dispersion and transformation processes through complex physicochemical models. While theoretically comprehensive, these approaches often proved computationally intensive and required detailed emission inventory data that limited their practical applicability.

Traditional statistical models

The limitations of purely physical models stimulated the development of statistical approaches that leveraged historical air quality data to identify patterns and relationships. Mani et al.3 developed Multi Linear Regression and ARIMA models to predict AQI in Chennai using pollutant data from CPCB sensors, demonstrating good predictive accuracy. Zhao et al.4 proposed a hybrid ARIMA model that integrates the Augmented Dickey–Fuller test, improved grid search, and entropy-based seasonal decomposition to enhance PM2.5 prediction accuracy in Beijing. Nevertheless, the proposed method is still predicated on linear modeling assumptions, which may limit its ability to effectively characterize the complex nonlinear and dynamic structures inherent in PM2.5 time series data. To address these limitations, Zhang et al.5 proposed a hybrid framework combining ARIMA with empirical wavelet transform (EWT). Liu et al.6 used complex network theory to study AQI patterns in the Yangtze River Delta, identifying key cities and regional structures.

Despite their theoretical elegance and interpretability, traditional statistical models faced inherent limitations in capturing the complex, nonlinear dynamics characteristic of atmospheric processes, particularly under rapidly changing meteorological conditions or unusual emission scenarios.

Machine learning approaches

The advent of machine learning methodologies marked a significant paradigm shift in AQI prediction, enabling more flexible modeling of complex, nonlinear relationships in air quality data7. Gupta et al.8 employed SVR, RFR, and CatBoost to predict AQI in Indian cities and showed that (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique)SMOTE improves prediction accuracy. Kulkarni et al.9 developed a multi-kernel SVM model that integrates meteorological, traffic, and industrial emission data to predict urban concentrations, achieving a 19.3% improvement in predictive accuracy compared to ARIMA. However, SVMs are limited in capturing long-term temporal dependencies. To address this issue, Pan et al.10 proposed an adaptive feature selection SVM model that utilizes a recursive feature elimination algorithm to dynamically identify key meteorological variables, improving the coefficient of determination (R2) for ozone prediction from 0.72 to 0.81. Nevertheless, machine learning models are constrained by their shallow architectures, which hinder their ability to effectively extract deeply coupled features from multimodal data sources (e.g., satellite remote sensing and ground-based monitoring). In addition, these models often exhibit a noticeable lag in responding to localized, sudden pollution events11.

While machine learning approaches demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional statistical methods, they remained constrained by their relatively shallow architectures, which limited their capacity to extract deeply coupled features from multimodal data sources and effectively model long-range temporal dependencies.

Deep learning and hybrid frameworks

Recent years have witnessed remarkable advances in air quality prediction through the application of deep learning techniques, which leverage hierarchical feature learning and end-to-end training paradigms12. Hou et al.13 proposed a hybrid model integrating Transformer and BiLSTM to identify parameters in nonlinear systems driven by fractional Brownian motion, demonstrating enhanced accuracy and computational efficiency. Méndez et al.14 reviewed 155 studies on machine learning methods for air quality forecasting, emphasizing the growing use of deep learning models. Gilik et al.15 developed a CNN-LSTM model for air quality prediction and achieved improved accuracy across several pollutants and cities. However, they did not address data imbalance, which can affect prediction performance. Bhardwaj and Ragiri16 employed a BiLSTM model to fuse historical meteorological series with pollutant data from adjacent monitoring stations. Cui et al.17 designed a spatiotemporal Transformer model that leverages multi-head attention to extract global spatiotemporal dependencies, reducing the RMSE of 7-day long-range ozone prediction by 22.6%.

Building on these efforts, recent studies have further explored advanced hybrid and lightweight architectures for AQI prediction. Sannasi et al.18 proposed a hybrid STGNN-TCN model combining spatio-temporal graph neural networks with temporal convolutional networks to jointly capture spatial and temporal dependencies. In a subsequent study, Sannasi et al.19 introduced an Iterative Skill Optimization recurrent network that leverages iterative training strategies to enhance predictive accuracy. Periasamy et al.20 developed an intelligent air quality monitoring system using quality indicators and a lightweight recurrent network with skip connections, incorporating transfer learning to improve performance across different urban environments. These approaches highlight the trend toward integrating global and local modeling, lightweight architectures, and transfer learning strategies to achieve more accurate, interpretable, and generalizable AQI predictions.

Research gaps and challenges

Despite these significant advancements, current AQI prediction approaches face several persistent challenges: Most existing models excel in either capturing long-range dependencies or modeling local temporal patterns, but rarely achieve both simultaneously in a unified framework. Many deep learning models exhibit reduced performance when applied to cities with different geographical characteristics, industrial structures, or meteorological conditions. The nature of complex deep learning models often limits their practical utility for environmental decision-making, where understanding feature contributions is crucial. Many state-of-the-art models require substantial computational resources, hindering their deployment in real-time monitoring systems or resource-constrained environments. Effectively integrating heterogeneous data sources, including meteorological information, satellite observations, and ground-based measurements, remains a significant technical challenge.

Contributions and novelty

Building on these advancements in hybrid and lightweight architectures, we propose a Transformer-BiLSTM model that simultaneously captures long-range dependencies via multi-head self-attention and short-term bidirectional temporal dynamics. This framework addresses key limitations of existing approaches by enabling unified global and local modeling, maintaining promising predictive performance across diverse cities, providing interpretable feature contributions, and supporting efficient real-time deployment. The model achieves predictive performance with RMSE = 3.0012, MAE = 1.7928, and \(\hbox {R}^2\) = 0.9694, outperforming representative recent studies, including ARIMA-CNN-LSTM (RMSE = 5.496, Duan et al.21), CNN-LSTM (RMSE = 24.23, Bekkar et al.22), CBAM-CNN-BiLSTM (RMSE = 18.90, Li et al.23), and EMD-Transformer (RMSE = 3.789, He et al.24) under comparable experimental settings. SHAP analysis identifies \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), and \(\hbox {O}_3\) as the most influential features, while the lightweight model (14.537MB, 1.361ms inference) ensures practical deployment.

Paper organization

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section “Models” provides a formal problem formulation and detailed description of the proposed Transformer-BiLSTM methodology. Section “Experiments” outlines the experimental design, including data sources, preprocessing procedures, and evaluation metrics. Section “Results” presents comprehensive experimental results and comparative analyses with baseline models, discusses the model’s generalization capability, feature importance patterns, and practical implications. Finally, Section “Discussion” and Section “Conclusion”concludes the paper and suggests promising directions for future research.

Models

Model framework

The Transformer-BiLSTM model effectively captures both long and short term dependencies in AQI by integrating the global modeling capability of the Transformer with the bidirectional temporal modeling strength of BiLSTM. The Transformer component captures global long-range dependencies, while the BiLSTM component, through bidirectional processing, extracts local temporal features—together improving the accuracy and robustness of AQI prediction. The overall process of using the Transformer-BiLSTM model, from data input to final AQI prediction, is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Step 1: This study was conducted based on the daily average concentrations of six major atmospheric pollutants and the daily AQI in Shijiazhuang, Beijing, and Tianjin from November 1, 2013, to February 28, 2025. The six pollutants include \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\) (\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)), \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\) (\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)), \(\hbox {SO}_2\) (\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)), \(\hbox {NO}_2\) (\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)), CO (mg/\(\hbox {m}^3\)), and \(\hbox {O}_3\) (\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)). The first 75% of the pollutant concentration and AQI data were used as the training set, while the remaining 25% were used as the test set.

Step 2: Data Processing: Due to the presence of missing values in the collected data and inconsistent measurement units across indicators, the input features were normalized to the range [\(-1\), 1]. Data filtering and denoising (removal of high-frequency noise from the original AQI sequences while preserving major trends), normalization (to improve neural network convergence and scale values to [\(-1\), 1], and the sliding-window method were employed to generate training and testing sequences for model training.The mathematical formulations for filtering and denoising, normalization, and sliding-window sequence construction are defined in Eqa. (1)–(3):

where, b and a denote the coefficients of a Butterworth filter, which are determined by the specified cutoff frequency and filter order. \(y_t\) denotes the filtered output, \(x_t\) denotes the original input signal, and the equation describes the filtering operation at time t.

where, \(x_t^{norm}\) denotes the normalized value at time t, mapping the original data to the interval [\(-1\), 1]; \(x_t\) denotes the original unnormalized value, while \(x_{max}\) and \(x_{min}\) denotes the maximum and minimum values of the input sequence.

where, \(x^{(i)}\) denotes the input data sequence within the i-th sliding window, spanning from time t to \(t + w - 1\) ,where w is the width of the sliding window. The corresponding target value \(y^{(i)}\) refers to the AQI at time \(t+w\), representing the next time step following the window.

Step 3: Model training: The proposed model is trained using mini-batch gradient descent. In each iteration, forward propagation is performed to generate predictions, followed by the computation of the mean squared error (MSE) loss. Subsequently, backpropagation is employed to update the model parameters. The AdamW optimizer is adopted to iteratively update the network weights, and a learning rate scheduler is utilized to gradually adjust the learning rate, thereby preventing convergence to local optima or unstable oscillations. The mathematical formulation of the MSE loss function is defined in Eq. (4):

where, \(y_i\) denotes the true AQI , \(\hat{y}_i\) denotes the predicted AQI, and n represents the number of samples.

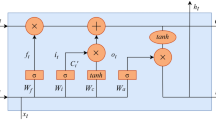

Step 4: Model Prediction: The Transformer-BiLSTM model integrates the Transformer and BiLSTM architectures to effectively model and forecast time series data. The overall architecture of the Transformer-BiLSTM model is illustrated in Fig. 2. The model comprises four core components: a positional encoding module (which injects position information into the sequence), a Transformer encoder layer (for capturing global temporal dependencies), a BiLSTM decoder layer (for learning local bidirectional patterns), and a fully connected output layer (for generating the final AQI predictions). These components collectively form the four main modules of the proposed model.

Step 5: Model Evaluation: The model performance was evaluated on both the validation and test datasets at each training epoch. The predicted AQI values were inverse-transformed to their original scale before being compared with the ground truth to calculate performance metrics, including the RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and \(R^2\). To quantitatively assess the AQI prediction performance, this study employed RMSE, MAE, and MAPE as the primary evaluation metrics. In addition, the predicted and actual AQI time series were plotted to provide a visual assessment of the model’s fitting accuracy and its ability to capture temporal trends. The mathematical formulations of RMSE, MAE, MAPE and \(R^2\) are formally defined in Eqs. (5)–(8):

where, \(y_i\) and \(\hat{y}_i\) denote the observed and predicted AQI values, respectively, n is the total number of samples, \(\sum _{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2\) represents the residual sum of squares (RSS), and \(\sum _{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \bar{y})^2\) denotes the total sum of squares (TSS).

Experiments

Experimental environment

All experiments were conducted on a workstation running Windows 11 (64-bit). The hardware was equipped with an Intel Core i7-13700K CPU (8 P-cores + 16 E-cores). The neural network models were implemented in Python 3.12 using the PyTorch 2.0.1 framework, while comparative models were constructed in MATLAB R2023a. A detailed summary of the hardware configuration is provided in Table 1.

Data sources and preprocessing

Data sources

The experimental data utilized in this study were collected from two publicly accessible sources: a historical weather data website (http://www.tianqihoubao.com) and the official air quality monitoring and analysis platform of the China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC) (https://www.cnemc.cn). Air quality monitoring data were collected from the historical weather database at (http://www.tianqihoubao.com), including daily average concentrations of PM2.5(\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)) , PM10(\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)) , SO2(\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)) , NO2(\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)) , CO(\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)) , and O3(\({\upmu }\)g/\(\hbox {m}^3\)). The daily Air Quality Index (AQI) data for each city were obtained from the official China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC) at (https://www.cnemc.cn). These data cover Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang for the period from November 1, 2013 to February 28, 2025. All modeling and experimental analyses in this study were conducted based on this dataset. The data source is open-access and publicly available without the need for registration. The study area includes the cities of Shijiazhuang, Beijing, and Tianjin, with Shijiazhuang located in Hebei Province. Figure 3 shows the location of the study area in China. The AQI provides a standardized measure of air pollution levels, helping to inform the public, guide environmental management, and support health protection. Figure 4 illustrates the trend of AQI changes in Beijing, Tianjin and Shijiazhuang in 2024, aiming to capture the fluctuation trends in air quality over the period.

Dataset 1—Beijing: From November 2013 to February 2025, Beijing’s \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {SO}_2\), \(\hbox {NO}_2\), CO, \(\hbox {O}_3\), and AQI data each had 18 missing values, with a mean AQI of 80.35. The dataset used in the experiments consisted of 4143 observations, with 4143 values for each of the six major pollutants and the AQI. This data was used for model development, with the first 75% of the pollutant concentration and AQI data serving as the training set, and the remaining 25% as the test set.

Dataset 2—Tianjin: From November 2013 to February 2025, Tianjin’s \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {SO}_2\), \(\hbox {NO}_2\), CO, \(\hbox {O}_3\), and AQI data each had 21 missing values, with a mean AQI of 85.71. The dataset used in the experiments consisted of 4140 observations, with 4140 values for each of the six major pollutants and the AQI. This data was used for model validation, with the first 75% of the pollutant concentration and AQI data serving as the training set, and the remaining 25% as the test set.

Dataset 3—Shijiazhuang: From November 2013 to February 2025, Shijiazhuang’s \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {SO}_2\), \(\hbox {NO}_2\), CO, \(\hbox {O}_3\), and AQI data each had 27 missing values, with a mean AQI of 105.60. The dataset used in the experiments consisted of 4134 observations, with 4,134 values for each of the six major pollutants and the AQI. This data was used for model validation, with the first 75% of the pollutant concentration and AQI data serving as the training set, and the remaining 25% as the test set. Figure 5 shows the trend of the monthly average AQI values for Beijing, Tianjin and Shijiazhuang in 2024.

Data preprocessing

The proportion of missing values in the original dataset was relatively small. Specifically, Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang contained 18, 21, and 27 missing daily records, corresponding to 0.43%, 0.51%, and 0.65% of the total samples, respectively. As the missing values appeared in consecutive periods and were relatively sparse, they were directly removed from the dataset to avoid interpolation bias. After removal, the effective dataset sizes were 4,143 samples for Beijing, 4,140 samples for Tianjin, and 4,134 samples for Shijiazhuang.

To reduce high-frequency noise, the raw time series were smoothed using a fifth-order Butterworth low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.1 Hz. The denoising effect was evident: the average standard deviation of pollutant concentration series decreased by 6.3% (Beijing), 5.9% (Tianjin), and 6.7% (Shijiazhuang), while preserving the overall seasonal and trend characteristics of the data.

The filtered data were then normalized using a MinMaxScaler to rescale the values into the range \([-1, 1]\), which improved numerical stability and accelerated model convergence during training. The normalized series was divided in chronological order into a training set (75%) and a test set (25%). Input-output sequences were generated using a sliding window approach, with an input length of 2 days and an output length of 1 day, resulting in 3107, 3105, and 3100 training samples for Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang, respectively.

To enhance model generalization and robustness, data augmentation was applied during training. Gaussian noise with \(\sigma = 0.02\) was added to 10% of the training sequences, and random masking with a probability of 0.1 was introduced. This augmentation strategy effectively increased the diversity of input patterns and reduced the risk of overfitting.

Finally, all processed sequences were converted into PyTorch tensors for model computation. The preprocessing workflow ensured that the dataset was clean, smoothed, normalized, and sufficiently diverse, making it reproducible and suitable for deep learning model development. The quantitative results of the data preprocessing procedures are summarized in Table 2.

Experimental design and hyperparameter optimization

Experimental framework

Figure 6 illustrates the comprehensive and systematic experimental framework adopted in this study to develop, evaluate, and interpret the proposed Transformer-BiLSTM model for AQI prediction. The entire process is structured into five cohesive phases, ensuring a rigorous and reproducible research methodology.

The framework commences with Data Collection and Preprocessing (Phase 1), where multi-source daily air quality data is gathered from publicly accessible historical weather and official monitoring platforms for three core cities: Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang. A standardized preprocessing pipeline is then applied, involving missing value handling, Butterworth filtering for noise reduction, Min-Max normalization, sequence construction via a sliding window, and data augmentation techniques to enhance model robustness.

The preprocessed data feeds into the Model Development and Training (Phase 2), which is the core of our approach. The novel Transformer-BiLSTM architecture is constructed, integrating a Transformer encoder for capturing global, long-range dependencies and a BiLSTM decoder for modeling local, bidirectional temporal patterns. A rigorous two-phase hyperparameter optimization strategy, combining Bayesian search with grid refinement, is employed to identify the optimal model configuration, which is then trained using the AdamW optimizer.

Subsequently, a Comprehensive Evaluation (Phase 3) is conducted to objectively validate the model’s performance. This involves a robust 5-fold time-series cross-validation protocol, a multi-metric assessment (RMSE, MAE, MAPE, \(R^{2}\)), and extensive comparisons against a suite of baseline and state-of-the-art models. Statistical significance tests are further performed to substantiate the performance improvements of our proposed model.

To ensure transparency and gain deeper insights, an Explainable AI and Extension Analysis (Phase 4) is undertaken. The SHAP framework is leveraged to quantify the contribution of each input pollutant, revealing \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), and \(\hbox {O}_3\) as the most influential features and highlighting city-specific variations. The model’s generalization capability and robustness are further scrutinized through tests across six additional Chinese cities with diverse environments and under varying data split ratios.

Finally, the framework concludes with a Deployment Assessment (Phase 5), where the model’s practical applicability is evaluated. Key operational metrics, including model size (14.537 MB), inference speed (1.361 ms), and memory usage (\(\sim\) 554 MB), are analyzed, confirming that the model is computationally efficient and sufficiently lightweight for potential deployment in real-world environmental monitoring systems. This end-to-end framework guarantees a thorough validation of the model’s accuracy, interpretability, generalizability, and practical utility.

Hyperparameter optimization strategy

We implemented a two-phase optimization procedure (Bayesian optimization followed by grid refinement) rather than arbitrary manual tuning, ensuring scientific and reproducible parameter selection. All models were optimized under identical computational resources and framework to guarantee fair comparison.

In the first phase, Bayesian optimization with the Optuna framework was applied to explore a predefined search space that included key architectural parameters (encoder layers [1–3], model dimension [128–320], attention heads [4–12], BiLSTM hidden size [2–32], and BiLSTM layers [1–3]) as well as training-related parameters (learning rate, dropout rate, batch size, and input window length).

In the second phase, grid refinement was conducted to investigate the most promising regions identified in the initial search. Model performance was evaluated using 5-fold time-series cross-validation, with RMSE as the primary evaluation criterion, complemented by MAE, MAPE, and \(R^2\) to provide a more comprehensive assessment.

The final configuration consisting of one Transformer layer (\(d_{\text {model}} = 250\)), 10 attention heads, a two-layer BiLSTM with hidden size of 2, and training parameters including a learning rate of 0.001, batch size of 16, dropout rate of 0.2, training epochs of 100 and input window length of 2.

Sensitivity analysis indicated that learning rate and BiLSTM hidden size had the most substantial impact on model performance. The entire optimization process was conducted under controlled random seed initialization to guarantee reproducibility. To ensure fair model evaluation and enhance predictive performance, the Transformer–BiLSTM model was optimized through a systematic hyperparameter search. Table 3 presents the optimized values for key parameters, which were subsequently adopted in the experimental analysis.

Results

Overall model performance and statistical validation

Performance evidenced by cross-validation

We employed 5-fold time-series cross-validation to obtain robust performance estimates, avoiding randomness from single data splits. A complementary set of evaluation metrics (RMSE, MAE, MAPE, \(R^2\)) was used for comprehensive assessment from multiple perspectives including error magnitude, percentage error, and goodness-of-fit. The Transformer-BiLSTM model achieves consistently high \(R^2\) values across folds (0.9324–0.9694) and exhibits prediction errors concentrated near zero, indicating stable and accurate performance compared with other models. Figure 7 shows the error distributions of the models in the five-fold cross-validation. The performance of the Transformer-BiLSTM model is due to its complementary architecture: the Transformer captures long-range dependencies in AQI time series through self-attention, while the BiLSTM learns sequential patterns in both directions, enhancing the representation of temporal dynamics. In comparison, BiLSTM captures sequential information but is less effective at long-range dependencies. CNN-GRU extracts features via convolution, yet may not fully represent temporal relationships. Transformer-Linear lacks sequential modeling, limiting its handling of AQI dynamics. Wavelet-BiLSTM incorporates preprocessing but may be less effective than the Transformer-BiLSTM combination in capturing both long-range and sequential dependencies.

Statistical significance test

To verify whether the proposed model outperforms the baseline model, statistical analysis was conducted, and the results are presented in Table 4. The results of the significance test indicate that the differences between the proposed model and the baseline methods are statistically significant across all evaluation metrics. Specifically, the t-statistics for \(R^2\), RMSE, MAE, and MAPE correspond to p-values that are substantially lower than the 0.05 threshold (all \(p < 0.001\)), thereby confirming that the proposed model achieves statistically significant improvements in predictive performance compared with the baseline methods.

City-specific predictive performance

Performance in Beijing

To evaluate the performance of the Transformer-BiLSTM model for AQI prediction in Beijing, several baseline models were compared, including single models (Transformer, BiLSTM) and hybrid models (Wavelet–BiLSTM, Transformer–Linear). The performance comparison results of the models are summarized in Table 5. Model performance was assessed using RMSE, MAE, and MAPE, where lower values indicate closer agreement with observed AQI. Among the baseline models compared, the Transformer–BiLSTM model achieved the lower RMSE (3.0012 \(\upmu g / m^3\)), MAE (1.7928 \(\upmu g / m^3\)), and MAPE (3.3646%). Compared with recent deep learning model CNN-GRU, it reduced RMSE and MAE, reflecting improved predictive accuracy. As shown in Fig. 8, the proposed Transformer-BiLSTM model exhibits a high degree of agreement with the observed values, and its predictive accuracy is higher than that of the other models. To further illustrate the training process and convergence behavior of the proposed model, the evolution of the training and validation loss over epochs is depicted in Fig. 9. As shown, the loss decreases steadily and converges after a certain number of epochs, indicating stable and effective model training.

Performance in Tianjin and Shijiazhuang

The performance of the Transformer-BiLSTM model was evaluated for AQI prediction in Tianjin and Shijiazhuang. The predictive performance for Tianjin and Shijiazhuang is shown in Fig. 10. The specific values of each evaluation metric are presented in Table 6. In Tianjin, the model achieved an RMSE of 4.4785 \(\upmu g / m^3\), MAE of 3.1614 \(r\mu g / m^3\), MAPE of 4.6917%, and \(R^2\) of 0.9621; in Shijiazhuang, it achieved an RMSE of 5.1646 \(\upmu g / m^3\), MAE of 3.4057 \(\upmu g / m^3\), MAPE of 5.2489%, and \(R^2\) of 0.9324. Compared with baseline and recent deep learning models, including BiLSTM, Transformer–Linear, Wavelet–BiLSTM, and CNN-GRU, the Transformer–BiLSTM model demonstrates lower error metrics and higher \(R^2\) values, indicating more accurate predictions.

Figure 11 presents the performance of the proposed model in terms of three evaluation metrics—RMSE, MAE, and MAPE—in two cities, Tianjin and Shijiazhuang. In Tianjin, the RMSE values vary across different models, with a peak of 17.06 and a low of 6.05; MAE ranges from 3.90 to 13.18; and MAPE shows a maximum of 22.86 and a minimum of 6.43. In Shijiazhuang, RMSE reaches up to 23.06 and down to 7.02; MAE spans from 3.41 to 18.21; and MAPE has a highest value of 28.51 and a lowest of 7.62. Overall, the proposed model demonstrates varying predictive accuracy in the two cities, with performance fluctuations reflected by the differences in these error metrics. Such variations may be attributed to differences in local data characteristics or environmental factors.

Model interpretability: SHAP analysis

Identification of dominant pollutants

To enhance the interpretability of the proposed Transformer-BiLSTM model and quantitatively assess the contribution of each input feature to the AQI predictions, we employed SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). SHAP is a unified framework based on cooperative game theory that assigns each feature an importance value for a particular prediction. The mathematical formulations of SHAP values are formally defined in Eqs. (9)–(10).

The core idea of SHAP is to compute the Shapley value \(\phi _i\) for each feature i, which represents the average marginal contribution of that feature across all possible feature coalitions. For a given model f and instance x, the SHAP explanation model is defined as:

where g is the explanation model, \(z' \in \{0, 1\}^M\) represents the presence of simplified input features, M is the maximum coalition size, and \(\phi _i \in \mathbb {R}\) is the Shapley value for feature i. The Shapley value \(\phi _i\) is calculated as:

where N is the set of all input features, S is a subset of features excluding i, and \(f_x(S)\) denotes the model prediction for instance x using only the feature subset S.

The SHAP analysis results are illustrated in Fig. 12. The Transformer module primarily captures long-range temporal dependencies, enabling the model to account for sequential pollutant patterns, while the BiLSTM module effectively models short-term temporal variations and interactions among pollutants. Panels (a) and (b) correspond to Beijing, panels (c) and (d) to Tianjin, and panels (e) and (f) to Shijiazhuang. The SHAP summary plot illustrates the distribution of feature impacts on the model’s output, while the mean SHAP plot ranks features by their average contribution to predictions. When analyzing AQI prediction for Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang using the Transformer–BiLSTM model, \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), and \(\hbox {O}_3\) emerge as the most influential pollutants. Specifically, in Beijing, their mean |SHAP| values are approximately 0.52–0.56; in Tianjin, \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\) ranks highest with 0.72, followed by \(\hbox {O}_3\) (0.61) and \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\) (0.53); in Shijiazhuang, \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\) exhibits the largest contribution (0.85), followed by \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\) (0.67) and \(\hbox {O}_3\) (0.58). SHAP analysis of the Transformer–BiLSTM model for AQI prediction in these three cities reveals subtle differences in the most influential features.

City-specific feature importance patterns

For Beijing, \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), and \(\hbox {O}_3\) emerged as the dominant factors. As a megacity characterized by dense traffic emissions and extensive residential heating, Beijing experiences substantial releases of \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\) and \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\). Moreover, complex meteorological conditions, such as temperature inversions, hinder the dispersion of these particles and further influence \(\hbox {O}_3\) formation, thereby underscoring the critical role of these three pollutants in shaping AQI. In Tianjin, \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), \(\hbox {O}_3\), and \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\) were identified as the key contributors. The city’s strong industrial base and busy port activities generate substantial industrial emissions, elevating the concentrations of \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\) and \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\). Furthermore, its coastal–industrial environment modulates chemical reactions and pollutant dispersion, leading to a pronounced influence of \(\hbox {O}_3\). Together, these factors play a decisive role in determining the AQI of Tianjin. For Shijiazhuang, \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), and \(\hbox {O}_3\) were also the primary drivers. Intense local industrial emissions, particularly from heavy industries, release large quantities of \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\) and \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\). The basin-like topography of the region favors pollutant accumulation, while strong solar radiation and temperature conditions enhance photochemical reactions, thereby amplifying the role of \(\hbox {O}_3\).

Across the three cities, \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), and \(\hbox {O}_3\) consistently emerge as critical features. However, differences in their relative importance reflect variations in local emission sources (traffic, residential, and industrial), meteorological phenomena (e.g., temperature inversions), and geographic settings (coastal–industrial environment, basin topography). These findings underscore the necessity of developing city-specific air quality management strategies tailored to local conditions.

Generalization capability and robustness

Cross-city generalization

Cross-City Generalization experiments are necessary to evaluate whether a model trained in one region can reliably predict air quality in other regions with different emission sources, climatic conditions, and urban characteristics, which is critical for real-world deployment in regional air quality monitoring and early-warning systems. The model effectively learns the core determinants of AQI through its Transformer encoder, which captures long-range dependencies and recurring multi-day accumulation and dispersal patterns, and the BiLSTM decoder, which models short-term, bidirectional interactions among pollutants, such as the diurnal cycle of \(\hbox {O}_3\). The generalization experiments conducted across six geographically and climatically diverse Chinese cities—Chengdu, Xi’an, Shenyang, Wulumuqi, Shanghai, and Guangzhou demonstrate that the Transformer-BiLSTM model maintains promising predictive performance (\(R^2 > 0.92\) in five out of six cities). The locations of the six regions in China are shown in Fig. 13. This robust performance reflects the model’s intrinsic ability to capture universal temporal dynamics of key pollutants (\(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), \(\hbox {PM}_{10}\), \(\hbox {O}_3\), etc.) across regions with varying emission sources and meteorological conditions.

Its generalization is further supported by a focus on relative temporal patterns rather than absolute concentration values. The per-dataset normalization of input features to the range \([-1, 1]\) removes scale differences between cities, allowing the model to recognize critical temporal signatures, such as rapid increases in \(\hbox {PM}_{2.5}\), regardless of the baseline concentration.

Overall, these experiments confirm that the Transformer-BiLSTM model possesses strong out-of-the-box generalizability, effectively capturing transferable and normalizable temporal representations of air pollution dynamics across diverse geographical and climatic contexts. Detailed descriptions of the datasets and evaluation metrics are provided in Table 7, with city-specific predictive performance illustrated in Fig. 14.

Shenyang, with the smallest dataset (2148 samples) and a harsh winter climate, exhibited slightly lower performance (\(R^2 = 0.8687\)), reflecting the challenges posed by extreme environmental conditions and limited data. For the region with the largest dataset, the Transformer–BiLSTM model demonstrates the best prediction results (AQI Count = 4262, \(R^2\) = 0.9651). This observation aligns with the fundamental principle in machine learning that sufficient data can provide more comprehensive information about the target phenomenon (AQI variation in this case). Larger datasets enable the model to learn more nuanced patterns and relationships within the data, thereby enhancing its performance. This indicates that, while the Transformer–BiLSTM model has shown reasonable generalization ability, increasing data volume can still contribute to further improving its predictive performance, which is a valuable insight for future model optimization and application.

Robustness to data partitioning

In terms of robustness, particularly the stability of the model’s performance under changes in data split ratios, Fig. 15 provides direct evidence: when the split ratio between the training set and test set is adjusted (e.g., the proportion of the training set varies between 65 and 85%, and the corresponding proportion of the test set changes between 35 and 15%), the core prediction metrics (RMSE, MAE, MAPE) of the Transformer-BiLSTM model always remain within a narrow fluctuation range without significant performance fluctuations. This indicates that the model has low sensitivity to data partitioning strategies; even when the partition boundary between the training and test data is adjusted, it can still maintain stable prediction accuracy.

Deployment feasibility

Computational efficiency for practical applications

The model’s operational characteristics confirm its suitability for real-world deployment. The Transformer-BiLSTM model has a size of 14.537 MB, with an average inference time of 1.361 ms and memory usage of approximately 554 MB, indicating that the model is relatively lightweight and efficient for deployment. Besides, the model maintains good performance across different data partitions, with moderate variability, and can be deployed with low computational overhead.

Discussion

In-depth discussion on model superiority and mechanisms

The experimental results consistently demonstrate that the proposed Transformer-BiLSTM model outperforms all baseline models across multiple cities and evaluation metrics. This superior performance can be attributed to the model’s unique architectural design, which effectively addresses the inherent challenges in AQI time series forecasting.

Comparative analysis of model architectures

The AQI sequence is characterized by complex temporal dependencies, including both long-range global trends (e.g., seasonal patterns, multi-day pollution cycles) and short-term local fluctuations(e.g., diurnal variations, sudden emission changes). Traditional models and single-architecture deep learning models often fail to capture this multi-scale nature simultaneously.

BiLSTM: The BiLSTM model captures bidirectional short-term dependencies effectively. However, its sequential processing nature and tendency to forget information over very long sequences limit its ability to model prolonged, global trends. This explains its higher RMSE and MAE compared to our hybrid model.

Transformer: The Transformer encoder excels at capturing long-range dependencies through its self-attention mechanism, which allows any position in the sequence to directly attend to any other position. However, the standard Transformer architecture is less adept at modeling the precise sequential order and short-term, point-to-point relationships due to its position encoding, which can be insufficient for highly auto-regressive series like AQI.

CNN-GRU and Wavelet-BiLSTM: While CNN-GRU utilizes convolutional layers for feature extraction, it may not fully leverage global context. The Wavelet-BiLSTM model incorporates frequency-domain analysis but might suffer from information loss during the decomposition and reconstruction phases, and its fixed wavelet basis may not be optimal for the non-stationary AQI data.

Synergistic module contribution in transformer-BiLSTM

The proposed hybrid model overcomes these limitations through a synergistic combination where each module plays a distinct and complementary role:

Transformer Encoder as the Global Context Extractor: The Transformer encoder layer acts as a powerful global context extractor. By computing attention weights across the entire input sequence, it identifies which historical time steps (e.g., from 3 days ago, 1 week ago) are most relevant for predicting the future AQI value. This is crucial for capturing phenomena such as the cumulative effect of sustained pollutant emissions or the influence of a large-scale, multi-day meteorological event. The multi-head attention mechanism (with 10 heads in our final configuration) allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces, potentially correlating different pollutants’ long-term behaviors.

BiLSTM Decoder as the Local Temporal Dynamics Model: The BiLSTM decoder layer serves as a refined local temporal dynamics model. It processes the sequence enriched with global context from the Transformer. Its bidirectional nature enables it to incorporate contextual information from both past and future within a local window, refining the predictions by understanding the immediate rising or falling trends. Furthermore, the LSTM’s gating mechanisms (input, forget, and output gates) are highly effective at learning the short-term, sequential patterns and abrupt changes that are common in AQI data, such as a sudden drop in pollution after a heavy rain.

Complementary Integration: The key to the model’s success lies in this complementary integration. The Transformer encoder first distills the long-range, global dependencies from the raw input sequence, producing a sequence of feature vectors that are globally aware. This sequence is then fed into the BiLSTM decoder, which acts on this enriched representation to model the fine-grained, local temporal dynamics leading to the final prediction. This pipeline allows each component to focus on its strength: the Transformer on “what” long-term events are important, and the BiLSTM on “how” the immediate sequence of events unfolds to reach the target value. This division of labor mitigates the BiLSTM’s long-range dependency problem and compensates for the Transformer’s potential weakness in local sequential modeling.

The performance gain of the Transformer-BiLSTM model is not accidental but is a direct consequence of its principled architectural design. The empirical evidence strongly suggests that the Transformer module is primarily responsible for capturing long-range, global dependencies, while the BiLSTM module enhances the prediction by modeling precise short-term, bidirectional temporal patterns. Their sequential integration creates a more comprehensive temporal representation than any single model can achieve, thereby providing a robust and accurate solution for AQI forecasting.

Conclusion

This study proposed a hybrid Transformer–BiLSTM model for AQI prediction, aiming to capture both long-range dependencies and short-term temporal dynamics. Extensive experiments using data from Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang demonstrated that the proposed model outperformed other approaches. As shown in Table 8, the proposed Transformer-BiLSTM model achieves the lowest RMSE of 3.0012 among representative recent works, substantially outperforming ARIMA–CNN–LSTM (5.496), CNN–LSTM (24.23), CBAM-CNN-BiLSTM (18.90), and EMD-Transformer (3.789). These results demonstrate the promising predictive accuracy of our hybrid model for AQI forecasting across multiple urban environments.

Despite these promising results, this work has several limitations. The AQI data were collected from fixed monitoring stations, which may not fully represent the spatial heterogeneity of pollutant distributions. In addition, only pollutant concentration data were considered, while other potentially important sources of information such as meteorological forecasts, traffic emissions, and satellite-based remote sensing were not incorporated.

Future research will address these limitations by: (i) integrating multi-source heterogeneous data (meteorological, remote sensing, and socio-economic factors) to further enhance predictive accuracy and generalization; (ii) improving computational efficiency and model compression to enable real-time deployment in large-scale monitoring systems; (iii) extending explainability analysis, such as causal inference and interpretable attention mechanisms, to provide actionable insights for environmental policy; and (iv) validating the framework across broader spatial scales, including cross-regional and cross-country scenarios, to assess its universality.

These directions will help establish the Transformer–BiLSTM model as a more powerful, interpretable, and deployable tool for intelligent air quality prediction and management.

Enhanced quantitative results

Compared with the best baseline model (CNN–GRU), the proposed Transformer–BiLSTM reduced RMSE by 40.2% in Beijing, 25.9% in Tianjin, and 26.5% in Shijiazhuang. Furthermore, in the generalization experiments across six additional representative Chinese cities, the proposed model consistently achieved \(R^2 > 0.86\), highlighting its robustness and applicability in diverse environments. The results of the statistical significance test (all \(p < 0.01\)) further confirm the superiority of our method over baseline approaches. These quantitative improvements strengthen the validity and generalization capability of the proposed framework.

Data availability

The experimental data utilized in this study were collected from two publicly accessible sources: a historical weather data website (http://www.tianqihoubao.com) and the official air quality monitoring and analysis platform of the China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC) (https://www.cnemc.cn). The dataset comprises daily air quality records, including corresponding AQI values, for the cities of Shijiazhuang, Beijing, and Tianjin, covering the period from November 1, 2013, to February 28, 2025.

References

Huang, Y., Zhang, X. & Li, Y. A novel hybrid model for PM2.5 concentration forecasting based on secondary decomposition ensemble and weight combination optimization. IEEE Access 11, 119748–119765 (2023).

Amnuaylojaroen, T. & Parasin, N. Pathogenesis of PM2.5-related disorders in different age groups: children, adults, and the elderly. Epigenomes 8(2), 13 (2024).

Mani, G. et al. Prediction and forecasting of air quality index in Chennai using regression and ARIMA time series models. J. Eng. Res. 10, 179–194 (2022).

Zhao, L., Li, Z. & Qu, L. Forecasting of Beijing PM2.5 with a hybrid ARIMA model based on integrated AIC and improved GS fixed-order methods and seasonal decomposition. Heliyon 8, 12 (2022).

Zhang, X., Jiang, X. & Li, Y. Prediction of air quality index based on the SSA-BiLSTM-LightGBM model. Sci. Rep. 13, 5550 (2023).

Liu, J.-B., Zheng, Y.-Q. & Lee, C.-C. Statistical analysis of the regional air quality index of Yangtze River Delta based on complex network theory. Appl. Energy 357, 122529 (2024).

Udristioiu, M. T., Mghouchi, Y. E. & Yildizhan, H. Prediction, modelling, and forecasting of PM and AQI using hybrid machine learning. J. Clean. Prod. 421, 138496 (2023).

Gupta, N. S. et al. Prediction of air quality index using machine learning techniques: a comparative analysis. J. Environ. Public Health 2023, 4916267 (2023).

Kulkarni, M., Raut, A., Chavan, S., Rajule, N. & Pawar, S. Air quality monitoring and prediction using SVM. In Proc. 2022 6th Int. Conf. on Computing, Communication, Control and Automation (ICCUBEA) 1–4 (2022).

Pan, Q., Harrou, F. & Sun, Y. A comparison of machine learning methods for ozone pollution prediction. J. Big Data 10, 63 (2023).

Chen, J., Li, D., Huang, R., Chen, Z. & Li, W. Aero-engine remaining useful life prediction method with self-adaptive multimodal data fusion and cluster-ensemble transfer regression. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 234, 109151 (2023).

Sarkar, N., Gupta, R., Keserwani, P. K. & Govil, M. C. Air quality index prediction using an effective hybrid deep learning model. Environ. Pollut. 315, 120404 (2022).

Hou, W. & Ma, S. Deep learning for parameter identification of nonlinear dynamical system driven by fractional Brownian motion. Nonlinear Dynamics 1–20 (2025).

Méndez, M., Merayo, M. G. & Núñez, M. Machine learning algorithms to forecast air quality: a survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56(9), 10031–10066 (2023).

Gilik, A., Ogrenci, A. S. & Ozmen, A. Air quality prediction using CNN+LSTM-based hybrid deep learning architecture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1, 1–19 (2022).

Bhardwaj, D. & Ragiri, P. R. A deep learning approach to enhance air quality prediction: Comparative analysis of LSTM, LSTM with attention mechanism and BiLSTM. In Proc. 2024 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP) 1–8 (2024).

Cui, B. et al. Deep learning methods for atmospheric PM\(_{2.5}\) prediction: A comparative study of transformer and CNN-LSTM-attention.. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 14(9), 101833 (2023).

Sannasi, P., Subramanian, P. & Surendran, R. STGNN-TCN: Hybrid model for spatiotemporal air quality prediction based on spatio-temporal graph neural networks and temporal convolutional networks. In Proc. 2025 Third International Conference on Augmented Intelligence and Sustainable Systems (ICAISS) 993–999. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAISS61471.2025.11042243 (IEEE, 2025).

Sannasi, P., Subramanian, P. & Surendran, R. Iterative skill optimization based recurrent network for air quality forecasting. In Proc. 2025 International Conference on Electronics and Renewable Systems (ICEARS) 1289–1294. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEARS64219.2025.10941077 (IEEE, 2025).

Periasamy, S., Subramanian, P. & Surendran, R. An intelligent air quality monitoring system using quality indicators and transfer learning based Lightweight recurrent network with skip connection. Glob. NEST J. 26(5), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.30955/gnj.006096 (2024).

Duan, J., Gong, Y., Luo, J. & Zhao, Z. Air-quality prediction based on the ARIMA-CNN-LSTM combination model optimized by dung beetle optimizer. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 12127. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38810-z (2023).

Bekkar, A. et al. Air-pollution prediction in smart city, deep learning approach. J. Big Data 8(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00483-y (2021).

Li, D., Liu, J. & Zhao, Y. Prediction of multi-site \(\text{ PM}_{2.5}\) concentrations in Beijing using CNN-BiLSTM with CBAM. Atmosphere 13(3), 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13030401 (2022).

He, Z. & Guo, Q. Comparative analysis of multiple deep learning models for forecasting monthly ambient \(\text{ PM}_{2.5}\) concentrations: A case study in Dezhou City, China. Atmosphere 15(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15010094 (2024).

Funding

This research is supported by the National Statistical Science Research Project (2024LY095) and the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2025JC-YBMS-670).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; methodology, X.L.; formal analysis, K.S.; data curation, K.S.; supervision, K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, S.W. and K.H.G. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Su, K., Wang, S. et al. Intelligent prediction of air quality index based on the transformer-BiLSTM model. Sci Rep 15, 41838 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25865-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25865-w