Abstract

The increasing integration of weather-dependent renewable energy sources into Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) introduces significant uncertainty in short-term dispatch planning. This paper develops a comprehensive decision-making framework that jointly optimizes credible capacity allocation and operational dispatch under forecast uncertainty. We first compare three probabilistic forecasting methods—Bayesian Neural Networks (BNN), Quantile Regression Forests (QRF), and Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT)—to quantify wind and solar variability, using metrics such as root mean square error (RMSE), continuous ranked probability score (CRPS), and empirical coverage. BNN is selected as the primary forecasting tool due to its superior calibration and robustness across both resource types. A distributionally robust optimization (DRO) model is then formulated using a Wasserstein ambiguity set and a Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) objective to hedge against worst-case renewable output scenarios. Empirical data from a stylized VPP system comprising 340 kW of installed renewables and urban mixed loads is used to evaluate the framework. Results indicate that the proposed DRO model reduces expected shortfall by up to 78% compared to deterministic baselines, and outperforms quantile-based models in both cost consistency and energy-not-supplied metrics. Scenario-based dispatch simulations reveal that increasing the CVaR confidence level from 90 to 99% improves system reliability from 95.1 to 99.7%, albeit with a 5.7% decline in expected profit. The analysis also quantifies the relative contribution of wind, solar, and load forecast errors to overall dispatch uncertainty. This work highlights the value of integrated probabilistic modelling and risk-aware optimization in enabling reliable and economically efficient VPP operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The accelerated transition toward renewable energy is reshaping how modern power systems are planned, operated, and optimized. Wind and solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies have expanded rapidly due to declining costs, supportive policies, and decarbonization targets1,2. Yet their stochastic, weather-dependent outputs introduce intermittency, forecast error, and balancing challenges at high penetration levels3,4. These challenges motivate coordination frameworks that can integrate diverse distributed assets under uncertainty. The Virtual Power Plant (VPP) concept aggregates heterogeneous resources—renewables, storage, demand response, and controllable loads–into a dispatchable portfolio capable of providing firm capacity and flexibility. As a result, VPPs are increasingly studied and deployed across Europe, North America, and Asia5,6,7,8.

A central open problem is the credible capacity of a VPP: the amount of power it can reliably commit under uncertainty8,9. Deterministic or expected-value approaches, which use point forecasts and heuristic reserves, are simple but often either over-conservative or risk-prone10,11,12. Stochastic programming introduces probabilistic scenarios and optimizes expected outcomes, but performance hinges on distributional assumptions and scenario quality, and complexity grows rapidly with dimensionality13,14. Chance-constrained formulations embed reliability targets, yet they commonly assume Gaussian errors and struggle with nonlinear, joint uncertainties across renewable sources, making them sensitive to sampling noise and model drift15,16,17,18.

Despite substantial progress in VPP scheduling and uncertainty modelling, existing credible capacity evaluation frameworks still exhibit several critical limitations. Most prior works treat renewable uncertainties as exogenous inputs with fixed probability distributions, neglecting the dynamic interaction between forecast accuracy and robust decision-making. Moreover, interdependencies between wind and solar generation are often oversimplified or ignored, leading to inaccurate reliability assessments when resources are meteorologically correlated. In addition, current DRO-based approaches typically define ambiguity sets statically, without adapting them to real-time changes in forecast dispersion or model calibration. To bridge these gaps, this study introduces a unified data-driven and optimization-integrated framework that couples machine learning-based probabilistic forecasting, copula-driven joint uncertainty modelling, and Wasserstein DRO with Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) objectives. The proposed model establishes a closed-loop connection between learned uncertainty and robust decision-making, enabling credible capacity evaluation that is both adaptive to forecast uncertainty and robust against distributional shifts. This directly addresses a major research gap in the existing literature by embedding renewable dependency structures and forecast-informed ambiguity calibration into the VPP optimization process, thereby ensuring reliability and interpretability in real-time operation. Recent advances in reinforcement learning (RL) have also opened new avenues for optimizing energy system operations. For instance, “Hierarchical coordination of networked-microgrids toward decentralized operation: A safe deep reinforcement learning method” proposed a hierarchical policy structure that enables decentralized decision-making while maintaining operational safety, demonstrating the capability of RL to manage multi-agent interactions in complex microgrid networks. Similarly, “Coordinated operation of multi-energy microgrids considering green hydrogen and congestion management via a safe policy learning approach” integrated safe policy learning mechanisms to balance power flow, hydrogen production, and network congestion, showing how RL can achieve adaptive control in coupled energy systems. While these studies highlight the potential of RL for data-driven and adaptive operation, they primarily emphasize real-time control and safety learning rather than robust capacity evaluation under probabilistic uncertainty. In contrast, the present study focuses on distributionally robust credible capacity assessment for VPPs, which establishes a closed-loop link between probabilistic forecasting, copula-based uncertainty modeling, and Wasserstein DRO optimization. Hence, our framework complements RL-based operation studies by addressing the upstream problem of capacity commitment and reliability assurance under uncertain renewable generation, providing a theoretically grounded basis for risk-aware dispatch decisions.

Unlike previous DRO-based credible capacity models that assume exogenous uncertainty distributions or rely on single-source renewables, the proposed framework introduces a fully integrated pipeline linking data-driven probabilistic forecasting, copula-based joint uncertainty modelling, and conditional risk optimization. Specifically, our method departs in three key ways: (i) it couples wind and PV forecast distributions using a Gaussian copula to capture nonlinear co-dependence across renewable types; (ii) it embeds these jointly learned distributions within a Wasserstein-based DRO model, allowing the ambiguity set to adapt dynamically to forecast calibration quality; and (iii) it introduces a risk-adjusted credible capacity constraint using a CVaR-driven objective that explicitly balances expected profit, reliability, and distributional robustness. This formulation thus extends existing DRO frameworks–typically based on fixed empirical distributions–by enabling closed-loop interaction between forecast uncertainty and robust decision-making.

Distributionally robust optimization (DRO) addresses distributional misspecification by optimizing against the worst case within an ambiguity set around the empirical distribution19,20. The Wasserstein metric yields a tractable and interpretable notion of proximity. While DRO has been used for unit commitment and reserve scheduling, its application to VPP credible capacity under coupled wind–PV uncertainty is still limited21,22. Moreover, many studies assume independence between sources. Copula theory separates marginal behaviour from dependence structure, allowing flexible modelling of nonlinear co-movements; however, its tight integration with robust optimization for operational VPP decisions remains rare.

Parallel advances in probabilistic forecasting–e.g., quantile regression forests (QRF) and Bayesian neural networks (BNNs)–provide calibrated predictive distributions that capture aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties23,24. Nonetheless, forecasts are often treated as exogenous inputs rather than being coupled to downstream decisions. Computational scalability is another barrier: as scenarios proliferate, robust optimization becomes intractable. Scenario reduction via k-medoids can retain representative samples and preserve statistical diversity while reducing complexity, enabling practical deployment within risk-aware scheduling25,26,27,28.

In recent years, uncertainty modelling for energy markets has evolved through several major methodological pathways. Stochastic programming approaches represent one of the earliest and most widely used methods, where renewable power generation is modeled through multiple probabilistic scenarios, and the optimization seeks to minimize expected cost or maximize expected profit under these stochastic realizations. While these models capture the statistical nature of renewable variability, they often rely on accurate distributional assumptions and large scenario sets, leading to high computational complexity and potential bias when the assumed distributions deviate from reality. Scenario-based methods, on the other hand, focus on constructing representative uncertainty samples–typically through clustering, sampling, or bootstrapping–to capture a wide range of operational conditions. Although these methods are more tractable, they still face challenges in preserving tail risk behavior and dynamic correlations between different renewable sources. Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR)-based formulations have been increasingly adopted to explicitly account for extreme but low-probability events in energy markets. CVaR introduces a quantile-based risk measure that penalizes large deviations beyond a specified confidence level, providing a balance between expected performance and downside protection. Studies such as “A Distributed Market-Aided Restoration Approach of Multi-Energy Distribution Systems Considering Comprehensive Uncertainties from Typhoon Disaster” and “Risk-averse stochastic capacity planning and P2P trading collaborative optimization for multi-energy microgrids considering carbon emission limitations: An asymmetric Nash bargaining approach” have demonstrated how these approaches can manage uncertainty and improve decision robustness under complex multi-energy interactions. However, these existing techniques often treat uncertainty exogenously and fail to establish a closed-loop connection between probabilistic forecasting and robust decision-making. The present work addresses this limitation by integrating learning-based probabilistic forecasting, copula-driven dependency modelling, and distributionally robust optimization (DRO) into a unified framework, thereby providing both interpretability and robustness across uncertain renewable conditions.

While existing DRO-based VPP optimization frameworks primarily focus on robust dispatch or market bidding under fixed uncertainty sets, they often assume independence among renewable sources and rely on exogenously defined ambiguity parameters. In contrast, the present work introduces a unified learning-to-robustness framework that directly couples probabilistic forecasting outputs with the DRO formulation through copula-based dependency modelling. By embedding forecast-derived joint distributions into the Wasserstein ambiguity set, the proposed model dynamically links forecast uncertainty, inter-source correlation, and risk-aware decision-making. This integrated structure enables the credible capacity to adapt to real-time probabilistic forecasts rather than being pre-determined by static uncertainty margins, thereby enhancing interpretability, adaptability, and decision precision in VPP operation. Compared with previous DRO-based VPP studies that treat the ambiguity set as an independent robustness parameter, our framework establishes a closed-loop coupling between uncertainty learning and robust optimization. This mechanism allows the ambiguity radius to evolve with the dispersion of the forecast distribution and the strength of renewable dependency captured by the copula. Consequently, the model achieves a more data-consistent risk representation and better scalability across varying renewable penetration levels. These characteristics differentiate our approach from traditional scenario-based or deterministic DRO formulations and substantiate its novelty in bridging data-driven probabilistic forecasting with distributionally robust market optimization.

In response to these gaps and limitations, the present paper proposes a comprehensive and unified framework for evaluating the credible capacity of VPPs under jointly distributed wind and PV uncertainty. At the core of this framework lies a sequence of methodological innovations that span the entire pipeline from probabilistic data modelling to robust decision-making. First, we generate high-resolution, probabilistic forecasts using a hybrid ML architecture: quantile regression forests for wind and Bayesian neural networks for solar. These forecasts are then jointly structured using a Gaussian copula to capture inter-resource dependencies. Next, a scenario reduction module selects representative samples using k-medoids clustering, retaining the structural fidelity of the joint distribution while reducing computational complexity. Finally, a distributionally robust optimization problem is formulated over a Wasserstein ambiguity set around the empirical joint forecast distribution. This formulation seeks the maximum dispatchable capacity that can be reliably committed at a desired confidence level, while remaining robust to sampling noise and forecast model drift. Our approach is applied to a real-world test case involving multiple wind farms, PV stations, and battery storage systems aggregated into a regional VPP. Through numerical experiments using one year of historical meteorological and generation data, we demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms traditional quantile-based benchmarks and stochastic optimization baselines. The evaluation includes reliability analysis, risk-adjusted profit calculations, and sensitivity tests to forecast quality and ambiguity size. Importantly, we also introduce a novel aggregation benefit index, which quantifies the contribution of spatial and technological diversification in reducing credible capacity uncertainty. In sum, the present study builds upon multiple strands of literature–VPP operation, probabilistic forecasting, copula modelling, DRO, and scenario reduction–and integrates them into a cohesive framework that addresses one of the most pressing open problems in renewable power system management: how to estimate, with mathematical rigor and practical reliability, the capacity a VPP can credibly offer in a stochastic and interdependent energy landscape. By doing so, it makes a substantial contribution to both theory and practice, offering tools and insights for researchers, system operators, and market participants alike.

Credible capacity evaluation is indispensable for Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) that participate in energy and capacity markets. Unlike conventional power units with deterministic generation characteristics, VPPs aggregate a portfolio of distributed and uncertain resources–such as solar PV, energy storage, and controllable loads–whose availability is affected by weather, user behavior, and communication reliability. Accurately quantifying the credible capacity enables VPPs to make reliable market commitments without risking overestimation that could cause non-delivery penalties or underestimation that would limit profit and flexibility. From a market perspective, credible capacity serves as the quantitative link between technical reliability and economic participation, defining bidding limits, reserve obligations, and compliance thresholds. Therefore, establishing a robust framework that evaluates VPP capacity under uncertainty is essential for ensuring both system security and fair market participation.

This study is primarily methodological in nature but motivated by practical challenges in Virtual Power Plant (VPP) operation and market participation. The proposed framework contributes to the methodological literature by integrating distributionally robust optimization, Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR)-based risk management, and scenario-based uncertainty quantification into a unified and computationally tractable equilibrium formulation. At the same time, it preserves strong application relevance through its validation on VPP scheduling and credible capacity evaluation tasks. Therefore, the intended audience includes both researchers in optimization and uncertainty modelling, who may focus on the theoretical contributions, and practitioners in energy systems engineering, who can apply the proposed framework to enhance reliability and market performance in real-world VPPs.

Mathmatical modelling

Figure 1 illustrates a comprehensive system architecture that integrates wind and PV forecasting, joint uncertainty modelling, and distributionally robust optimization to evaluate credible VPP capacity while accounting for both under- and over-generation penalties.

The joint uncertainty module simultaneously integrates wind and photovoltaic (PV) probabilistic forecasts using a Gaussian copula to model nonlinear dependencies and co-variations between the two renewable sources. Both wind and PV uncertainty distributions feed into the Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO) layer, which in turn provides optimized credible capacity parameters (CCE) through a feedback linkage, as indicated by the arrowheads from the DRO block to the CCE block in it.

This objective aims to maximize the total expected profit of the virtual power plant across all assets \(\iota \in \mathscr {V}\) and time intervals \(\tau\), while carefully accounting for multiple layers of uncertainty. The first term represents the revenue gained from market participation, where \(\phi _{\iota , \tau }^{\text {mkt}}\) is the forecasted market clearing price and \(\Pi _{\iota , \tau }^{\text {bid}}\) is the committed bidding power. The second term penalizes renewable curtailment, calculated by the gap between reserve commitment \(\psi _{\iota , \tau }^{\text {res}}\) and actual generation \(\widetilde{\psi }_{\iota , \tau }^{\text {gen}}\). The last nested term introduces scenario-dependent costs under a distribution \(\Omega\), weighted by their probabilities \(\rho _{\omega }\). It includes energy storage operation costs – both charging \(\vartheta ^{\text {ch}}\) and discharging \(\vartheta ^{\text {dis}}\) – and deviation penalties between committed power and realized renewable generation in each scenario. This structure balances expected profit maximization with reliability and robustness, integrating price-based incentives, storage behavior, and the impact of deviation penalties in one unified function. In this formulation, \(\Pi ^{\text {bid}}_{\iota ,\tau }\) denotes the committed bidding power of resource \(\iota\) at time \(\tau\), \(\tilde{\psi }^{\text {gen}}_{\iota ,\tau }\) represents the realized renewable generation, and \(\psi ^{\text {res}}_{\iota ,\tau }\) is the reserved backup power. \(\phi ^{\text {mkt}}_{\iota ,\tau }\) is the market clearing price, \(\zeta ^{\text {cur}}_{\iota ,\tau }\) is the curtailment penalty coefficient, \(\chi ^{\text {stor}}_{\iota ,\tau ,\omega }\) is the unit cost weight of energy storage operation, \(\vartheta ^{\text {ch}}_{\iota ,\tau ,\omega }\) and \(\vartheta ^{\text {dis}}_{\iota ,\tau ,\omega }\) are charging and discharging powers, respectively, and \(\mu ^{\text {adj}}_{\iota ,\tau ,\omega }\) quantifies the mismatch penalty between committed and realized outputs. All \(\rho _\omega\) represent the probability weights associated with scenario \(\omega \in \Omega\).

This formulation introduces a risk-averse counterpart to the economic objective using the Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) approach, tailored to penalize extreme deviations under renewable generation uncertainty. The outer summation iterates over all time periods and VPP components, seeking to minimize the expected shortfall beyond a certain quantile level \(\alpha\). The term \(\lambda _{\iota , \tau }^{\text {base}}\) acts as the VaR (Value-at-Risk) baseline threshold, while the inner max expression captures the tail losses – i.e., how much the committed bid \(\Pi _{\iota , \tau }^{\text {bid}}\) exceeds the actual generation \(\psi _{\iota , \tau , \omega }^{\text {gen}}\) under each scenario \(\omega\). The factor \(\frac{1}{1 - \alpha }\) ensures that this tail expectation is properly scaled to reflect confidence level \(\alpha\). By combining these elements, the CVaR-based objective penalizes the operator not merely for the average mismatch, but for the worst-case mismatch beyond the confidence level, enabling a robust and conservative dispatch policy that accounts for heavy tails and rare-but-costly undergeneration events.

Although Gaussian copulas are widely used due to their analytical simplicity and compatibility with high-dimensional joint modelling, we acknowledge that they may underestimate tail dependencies between renewable energy sources. The choice of Gaussian copula in this study is primarily motivated by its computational efficiency and the need for seamless integration with the Wasserstein-based DRO formulation, which already introduces nonlinearity in ambiguity calibration. While t-copulas and vine copulas offer richer tail dependence structures, they require additional parameter estimation (e.g., degrees of freedom or hierarchical pair-copula decompositions) that significantly increase computational complexity, especially under iterative optimization. To verify robustness, a complementary validation using t-copula modelling was conducted (see Case Studies), showing consistent credible capacity outcomes with less than a 3.5% deviation. Therefore, the Gaussian copula provides a sufficient balance between representational adequacy, numerical stability, and integration feasibility within the proposed probabilistic–DRO framework.

Power balance must be maintained within each scenario \(\omega\) and time step \(\tau\), where net output from renewable generation and battery operations must collectively support the total committed dispatch \(\Pi _{\iota ,\tau }^{\text {bid}}\). The equality enforces that VPP-internal balancing between generation, storage discharge, and storage charge is aligned with external bidding commitments.

Forecasted renewable generation under scenario \(\omega\) must not exceed the pre-defined lower quantile threshold \(\widehat{\psi }_{\iota , \tau }^{\textrm{q,low}}\), which represents the 5–10% lower bound of the probabilistic forecast distribution. This constraint enforces conservative scheduling by ensuring that generation commitments remain within the credible confidence interval under adverse forecast deviations.

Credible capacity \(\Pi _{\tau }^{\text {cred}}\) is defined through a probabilistic guarantee: the aggregated renewable generation must exceed the declared credible output with probability at least \(\beta\) (e.g., 95%). This condition forms the backbone of reliability assurance in capacity markets, embedding forecast uncertainty directly into dispatchability evaluation.

Equation (5) formally defines the credible capacity \(\Pi _{\text {cred}}\, \tau\) as the maximum aggregated renewable output that can be guaranteed with probability \(\beta\) (e.g., 95% or higher). In other words, the total renewable generation across all resources should exceed the declared credible capacity in at least \(\beta\) fraction of the scenarios, ensuring statistically reliable performance.

Energy state-of-charge (SoC) for each battery asset evolves over time based on efficiency-adjusted charge and discharge activities. Charging is scaled by efficiency \(\eta ^{\text {ch}}\), while discharging accounts for losses through the inverse of \(\eta ^{\text {dis}}\). The equation ensures intertemporal consistency of stored energy across time steps. Here, \(\kappa _{\iota ,\tau ,\omega }\) denotes the state of charge (SoC) of the storage device \(\iota\) at time \(\tau\) under scenario \(\omega\). \(\eta ^{\text {ch}}\) and \(\eta ^{\text {dis}}\) are charging and discharging efficiencies, respectively. The equation enforces intertemporal energy consistency, ensuring that SoC evolves based on the efficiency-adjusted balance of input and output power.

Limits on battery charging and discharging rates are strictly enforced by upper bounds \(\overline{\vartheta }_{\iota }^{\text {ch}}\) and \(\overline{\vartheta }_{\iota }^{\text {dis}}\). These bounds reflect technological constraints and help prevent operational overstrain of storage devices under high variability.

Stored energy within batteries is bounded by device-specific minimum and maximum thresholds \(\underline{\kappa }_{\iota }\) and \(\overline{\kappa }_{\iota }\), safeguarding the system from deep discharges or overcharges that may shorten battery lifespan or violate safety limits.

An entropy-style constraint anchors the confidence region of the renewable generation forecast by linking cumulative log-probability of generation events across all assets and time to a global confidence budget \(\epsilon\). This form is inspired by distributionally robust chance constraint relaxation.

Correlated wind and PV uncertainty is modeled using a copula function \(\varvec{F}_{\text {copula}}\), which ties together the marginal distributions \(\varvec{F}_{\iota , \tau , \omega }^{\text {marg}}\) for each renewable unit. This structure retains interdependence while allowing flexible, non-Gaussian tail modelling, critical for multivariate risk.

The probabilistic feasibility of dispatch commitments is formally guaranteed through this chance constraint, ensuring that total generation plus discharge minus charge meets or exceeds bid power with probability at least \(\alpha\). It acts as a distributionally robust guardrail against undergeneration.

Credible capacity is upper bounded by the total scheduled generation minus a deduction \(\Delta _{\tau }^{\text {uncert}}\) which reflects the width of uncertainty bands. The subtracted term can be obtained through scenario analysis or forecast variance, and ensures conservative bidding.

An aggregated reserve margin cap \(\xi ^{\text {margin}}\) is imposed over all scenarios to prevent large-scale under-delivery risks. The indicator function \(\textbf{1}\{\cdot \}\) triggers whenever bid exceeds generation, aggregating total violations into a single interpretable metric.

Each asset’s maximum contribution to the dispatch is restricted by a local feeder or distribution limit \(\theta _{\iota }^{\text {dist}}\). These values depend on network topology or export constraints, acting as physical limits within low-voltage regions of the grid. For completeness, the following notations are used throughout the model: \(\theta ^{\text {dist}}_{\iota }\) represents the maximum dispatchable power limited by feeder capacity; \(\xi ^{\text {margin}}\) denotes the total allowable reserve margin to prevent large-scale under-delivery; \(\Delta ^{\text {uncert}}_{\tau }\) captures the uncertainty margin deducted from scheduled generation; \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) denote the confidence levels of chance constraints and credible capacity evaluation, respectively. Indices \(\tau \in T\) represent time periods, and \(\omega \in \Omega\) enumerate uncertainty scenarios.

Methodology

To construct a credible and risk-aware dispatch framework for Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) under renewable uncertainty, we develop a multi-layered modelling approach that integrates probabilistic forecasting, credible capacity estimation, and a two-stage Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO) formulation. The methodology consists of four key components: (1) generation of calibrated probabilistic forecasts for wind and photovoltaic (PV) output using Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs); (2) transformation of these forecasts into credible capacity profiles based on quantile thresholds; (3) formulation of a CVaR-driven DRO dispatch model accounting for uncertainty in renewable generation and load; and (4) scenario-based evaluation of economic and reliability outcomes under varying risk aversion levels. All mathematical components are rigorously defined in the following subsections, beginning with the forecasting layer.

To enhance clarity, Algorithm 1 outlines the multi-layer optimization procedure linking the CVaR-driven objective and the Wasserstein ambiguity set. The process begins with probabilistic forecasts of wind and PV generation, followed by uncertainty sampling, ambiguity set construction, and iterative optimization of dispatch and credible capacity variables.

Wind power forecasting is conducted using a quantile regression forest (QRF) model, where \(f^{\text {QRF}}_{\iota , \tau }(\cdot )\) is trained over meteorological inputs \(\varvec{\Upsilon }_{\tau }^{\text {meteo}}\), producing quantile-distributed outputs. Parameters \(\varvec{\Theta }^{\text {QRF}}\) encode learned tree structure and splitting rules, and the final point estimate \(\widehat{\psi }_{\iota , \tau }^{\text {wind}}\) represents the expected renewable yield under given forecast conditions.

Solar PV output is predicted using a Bayesian deep neural network with a variational approximation over weights \(\varvec{W}_1, \varvec{W}_2\). The model input \(\varvec{\Upsilon }_{\tau }^{\text {irr}}\) includes irradiance, temperature, and humidity forecasts. The integral marginalizes over the posterior of weights, capturing epistemic uncertainty and delivering probabilistic forecasts critical for robust dispatch.

A joint multivariate distribution over wind and PV generation is constructed using a Gaussian copula \(\mathscr {C}_{\varvec{\Sigma }}\), which links individual marginal CDFs \(\mathbb {F}_i(u_i)\) via a correlation matrix \(\varvec{\Sigma }\). This formulation captures nonlinear dependencies and tail events beyond what linear correlation measures can express.

The Wasserstein distance \(\mathscr {W}_{\varepsilon }(\cdot )\) defines a ball around the empirical distribution \(\widehat{\mathbb {Q}}\), restricting the ambiguity set \(\mathbb {Q}\) used in the DRO model. Coupling distribution \(\gamma\) spans all valid transportation plans between probability masses over uncertainty space \(\Omega\), ensuring robust optimization is protected against sampling variation.

Within the ambiguity set \(\mathscr {P}_{\varepsilon }\), the worst-case expected shortfall (i.e., generation shortage relative to bid \(\Pi _{\tau }^{\text {bid}}\)) is bounded by a tolerance threshold \(\xi _{\tau }^{\text {tol}}\). This condition enforces distributionally robust credible bidding even when the true distribution deviates from the empirical estimate.

A dual reformulation of the DRO constraint, this CVaR-style surrogate transforms the min-max robust shortfall problem into a tractable convex minimization over scalar auxiliary variable \(\lambda\). The expected hinge loss captures the “worst tail,” offering an efficient solution while preserving robustness guarantees. Unlike quantile-based risk measures that only capture a specific percentile of the loss distribution, the CVaR-based objective used in this study accounts for the expected magnitude of losses beyond the chosen quantile threshold. This extension provides a more comprehensive and coherent representation of tail risks, ensuring that decision-making explicitly considers not only the probability but also the severity of extreme deviations. Mathematically, the CVaR surrogate yields a convex optimization problem, which is computationally more stable than discrete quantile formulations and thus better suited for large-scale market-based scheduling. Consequently, the CVaR-driven objective enhances risk management by preventing abrupt sensitivity to outliers and by ensuring smoother and more resilient operational strategies under extreme uncertainty. Compared with conventional deterministic or stochastic optimization, this dual reformulation highlights the key distinction of the proposed DRO-based framework. Deterministic models rely on fixed forecasts of renewable generation and demand, neglecting their probabilistic variability. Stochastic formulations account for randomness via predefined scenario sets but require a known probability distribution, which may be misspecified or non-stationary. In contrast, the present model optimizes against a family of plausible distributions within a Wasserstein ambiguity set, ensuring resilience even under data shifts and limited samples. The dual representation shown in (20) makes this distributionally robust problem computationally tractable by converting the original min–max formulation into a convex surrogate, preserving robustness while remaining solvable for realistic VPP scales. This balance between theoretical rigor and computational feasibility marks a key advancement over traditional deterministic or stochastic framework

An aggregation benefit index \(\mathscr {A}_{\text {agg}}\) is introduced to measure the reduction in variance due to spatial and technological diversity across assets. A higher \(\mathscr {A}_{\text {agg}}\) implies stronger smoothing effects, indicating that aggregation enhances reliability under uncertainty.

Scenario reduction via \(K\)-medoids is employed to identify representative uncertainty samples. The optimization seeks a reduced scenario set \(\mathbb {S}_{k}^{\text {red}}\) that minimizes the total within-cluster distance to medoid centroids \(\omega _{j}^{\text {centroid}}\), thus maintaining statistical fidelity with fewer points. The K-medoids clustering algorithm offers distinct advantages for scenario reduction in this study. It selects representative scenarios directly from the dataset, ensuring that each medoid corresponds to an actual realization rather than a synthetic centroid. This property enhances interpretability and robustness to outliers, which is critical when modelling renewable generation and demand uncertainties that often exhibit extreme events. Additionally, K-medoids minimizes total within-cluster dissimilarity, thereby preserving the key probabilistic structure of the original uncertainty set. However, K-medoids also has limitations. The computational complexity grows with the number of scenarios, and the method may underrepresent joint tail dependencies among multiple stochastic variables. To mitigate these limitations, the reduced scenario set is validated statistically to ensure that the essential correlation and distributional characteristics are retained. Overall, K-medoids provides a balanced compromise between physical interpretability, robustness, and computational tractability for uncertainty reduction in VPP capacity evaluation.

An empirical risk function \(\widehat{L}_{\text {risk}}\) is used to evaluate squared shortfall between committed dispatch and actual realized generation, across all scenarios. This loss can guide model refinement, confidence level adjustment, or be used as a penalty term in post-training calibration of bid aggressiveness.

To enable gradient-based optimization under non-smooth losses, a surrogate logistic loss \(\mathscr {L}^{\text {smooth}}\) is introduced as a differentiable proxy for the shortfall penalty. This formulation is useful in hybrid DRO-ML frameworks where predictive models and bidding decisions are jointly optimized.

The confidence-calibrated capacity threshold \(\gamma _{\tau }^{\text {conf}}\) is computed by inverting the forecast distribution to find the \(\beta\)-quantile, ensuring that at least \(\beta\) percent of generation realizations meet or exceed it. This level plays a key role in linking stochastic forecasts to deterministic scheduling policies.

Case studies

The case study is constructed on a synthetic yet realistic Virtual Power Plant (VPP) configuration designed to emulate the operational dynamics of a distributed energy system under renewable uncertainty. The VPP aggregates three wind turbines (WT1–WT3) with rated capacities of 80 kW, 65 kW, and 55 kW, and four rooftop photovoltaic (PV) arrays (PV1–PV4), each ranging from 20 kW to 35 kW, resulting in a total renewable installed capacity of 320 kW. The historical renewable generation data are sampled at a 15-min resolution from the NREL Western Wind and Solar Integration Dataset (WWSIS), with site-specific re-scaling to reflect the variability patterns of a temperate mid-latitude region. Load demand is modeled as a composite of residential and light commercial users, with a daily peak of 285 kW and a base load of 145 kW, following a smoothed empirical profile derived from the Pecan Street dataset. Forecast errors for both wind and solar are synthesized via Gaussian Copula models, ensuring preservation of cross-source temporal correlation. Load uncertainty is introduced using a triangular distribution centered at the day-ahead forecast with \(\pm 10\%\) deviation bounds.

For renewable forecast modelling, three state-of-the-art probabilistic techniques—Bayesian Neural Network (BNN), Quantile Regression Forest (QRF), and Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT)—are trained using 18 months of simulated NWP-aligned weather data. Model hyperparameters are optimized through a five-fold cross-validation routine on a rolling-window basis. Each forecast provides a 96-step ahead prediction horizon (24 hours), with outputs including prediction intervals and full predictive distributions. For credible capacity estimation, we define operational confidence levels at 90%, 95%, and 99%, and perform Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO)-based planning under Wasserstein distance ambiguity sets with varying radius \(\theta \in [0.01, 0.15]\). Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) confidence levels are also varied from 0.90 to 0.99 for robustness assessment. Uncertainty quantification is performed separately for wind, PV, and load components, with total variance decomposition and Shannon entropy used to allocate risk-informed weights in the dispatch model.

All optimization models, including the multi-stage DRO and scenario-based baseline methods, are implemented in Python 3.10 using the Pyomo and CVXPY libraries. The MILP formulations for dispatch decisions are solved via Gurobi Optimizer v10.0.3 with a time limit of 1800 seconds per scenario batch and an optimality gap threshold of \(10^{-4}\). Probabilistic forecasts and posterior sampling are carried out using PyTorch 2.0 for BNNs and Scikit-learn 1.3.2 for QRF and GBDT models. Experiments are run on a high-performance computing node equipped with dual Intel Xeon Gold 6338 CPUs (2.0 GHz, 32 cores), 256 GB DDR4 RAM, and an NVIDIA A100 GPU for parallel model evaluation. A total of 5000 Monte Carlo scenarios are generated for stress testing, and 200 bootstrap replications are conducted for result stability. Execution time for the full simulation-optimization pipeline averages 76.3 min per policy configuration.

Figure 2 presents the daily mean forecast error (bias) in kilowatts (kW) for wind and PV generation across a 14-day period, with separate bars representing wind (in light blue) and PV (in light grey-blue). The mean forecast error reflects the average deviation between predicted and actual generation, indicating whether the model tends to overestimate or underestimate output on a given day. For wind, the error fluctuates between − 3.2 kW and +2.5 kW, while PV exhibits wider variability ranging from − 4.8 kW to +3.7 kW. On Day 6, for example, wind showed a small overestimation of +1.8 kW while PV had a significant underestimation of − 4.1 kW, highlighting how their biases can be directionally misaligned. These results emphasize not only the magnitude but also the asymmetry of bias across different resources. The average absolute bias for PV is approximately 2.9 kW over the two weeks, whereas for wind it is around 1.7 kW, suggesting that PV forecasting errors are both more frequent and more extreme in deviation. Days 2, 4, and 11 show particularly high errors in PV, exceeding ± 3.5 kW, whereas wind remains within ± 2 kW for most of the time. This performance difference could stem from the inherently more volatile irradiance patterns and cloud movement which challenge PV prediction algorithms, as compared to the smoother, more predictable wind speed profiles in the selected dataset.

Figure 3 visualizes the probability distributions of forecast errors for wind and PV generation using normalized histograms overlaid with kernel density estimation (KDE) curves. The x-axis measures forecast error in kilowatts, with zero representing perfect forecast accuracy. The wind error distribution, shown in light blue, is centered tightly around 0 kW with most values lying between − 10 kW and +10 kW, indicating a symmetric and relatively sharp peak. In contrast, the PV error distribution, shown in light grey-blue, is broader and flatter, with a spread ranging from approximately − 18 kW to +18 kW and a noticeable negative skew. Quantitatively, wind forecast errors exhibit a standard deviation of roughly 5.1 kW, while PV forecast errors show a larger spread of about 6.9 kW. The peak density for wind occurs close to 0.03, centered almost perfectly at zero, affirming that the wind forecasting model is statistically unbiased in the mean. The PV density peak is both lower and offset toward the negative side, with its mode at approximately − 3.1 kW, suggesting a systematic underestimation during periods of high irradiance variability. These density differences confirm that while wind errors are more tightly controlled, PV forecasts are more susceptible to sudden changes and outliers–factors that must be considered when establishing credible VPP capacity bounds.

Figure 4 illustrates the Aggregation Benefit Index (ABI) as a function of the number of renewable assets in a Virtual Power Plant (VPP) portfolio. The x-axis ranges from 2 to 10 assets, while the y-axis represents the ABI, which is calculated as the proportional reduction in variance resulting from aggregation. The figure shows a monotonic increase in ABI from 0.10 to approximately 0.47 as the number of assets grows. When the VPP aggregates just two resources, the variance reduction is modest, at only around 10%. However, as the portfolio expands to 10 assets, nearly half of the variance is smoothed out due to statistical averaging and diversification effects. The shape of the curve highlights the diminishing marginal benefit of adding additional assets. Between 2 and 5 aggregated assets, the ABI increases rapidly from 0.10 to 0.32, suggesting that most of the gain in variance reduction is captured early. After that point, the slope flattens, and the ABI grows more slowly, increasing from 0.32 to 0.47 between 5 and 10 assets. This non-linear behavior is characteristic of central limit behavior: each additional resource contributes less smoothing value as the ensemble becomes more stable. The ABI serves as a key quantitative metric for assessing how aggregation mitigates uncertainty and why VPPs offer reliability advantages over isolated resources. This visualization provides direct justification for the assumption in the credible capacity model that aggregation increases reliability. The benefit of aggregation is not uniform across scales; rather, it is strongest when adding the first few resources and tapers off with larger portfolios. Consequently, for system planners, targeting portfolios of at least 5–7 assets yields strong reliability benefits without unnecessary expansion. In later modelling stages, this ABI curve will motivate how the credible capacity constraint is scaled with respect to system diversity, and how spatial or technological heterogeneity further enhances robustness against forecast error. In the context of Fig. 4, each ‘asset’ refers to a single physical generation unit–either one wind turbine or one rooftop PV array–participating in the Virtual Power Plant (VPP). Specifically, the test system includes three wind turbines (WT1–WT3) rated at 80 kW, 65 kW, and 55 kW, and four rooftop PV arrays (PV1–PV4) rated between 20 kW and 35 kW. Each asset is treated as an equivalent stochastic entity in the aggregation process, meaning that the Aggregation Benefit Index (ABI) is computed using normalized power outputs from each unit to ensure comparability across technologies. The order in which assets are added for the ABI curve is randomized and repeated 100 times to remove ordering bias, and the plotted curve represents the mean ABI across these permutations. Therefore, the results are independent of the sequence in which individual assets are aggregated.

Figure 5 visualizes the effect of applying a K-medoids clustering algorithm for reducing the dimensionality of uncertainty scenarios used in the optimization model. In this figure, 100 original scenarios are represented as semi-transparent grey-blue dots in a 2D uncertainty space, while 10 selected representative scenarios–chosen by the K-medoids method–are shown in saturated blue with larger marker size and grey edge outlines. These representative points serve as medoids, or central samples, around which other similar scenarios are clustered. This scatterplot shows that the reduced scenario set maintains coverage of the entire uncertainty domain. The 10 medoids are well distributed throughout the space, with no major clustering or omission of boundary regions. This ensures that extreme cases and center cases are both represented, allowing the optimization problem to remain sensitive to the full range of possible outcomes. By reducing the number of scenarios by 90% (from 100 to 10), the computational complexity of downstream optimization is dramatically decreased while preserving fidelity to the original uncertainty structure.

Although the K-medoids algorithm successfully preserves the overall topology of the joint uncertainty space, certain extreme low-output combinations–particularly the simultaneous low-wind, low-PV (‘low-low’) region–are sparsely represented after reduction. This sparsity arises because such scenarios lie in the lower-tail region of the empirical joint distribution and carry very small probability mass. To prevent under-representation of these critical states, a small number of synthetic stress scenarios are re-introduced around the 1st–5th percentile quantiles of both resources before optimization. These additional points ensure that the Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO) formulation remains sensitive to rare but operationally severe co-deficient events. The Wasserstein radius \(\varepsilon\) determines the size of the ambiguity set and thus directly influences the trade-off between robustness and conservatism. In this study, \(\varepsilon\) was calibrated by minimizing the out-of-sample CVaR loss over a validation subset of probabilistic forecast scenarios. Empirically, the optimal \(\varepsilon\) was found to lie within the range of 0.03–0.07, consistent with the divergence observed between empirical and forecasted distributions. To further illustrate its effect, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying \(\varepsilon\) from 0.01 to 0.10. The results indicate that smaller values (\(\varepsilon <0.03\)) lead to tighter credible capacity estimates but higher violation risk, whereas larger values (\(\varepsilon >0.08\)) increase conservatism and reduce market profit by up to 6.2%. Within the moderate range (\(\varepsilon =0.05\pm 0.02\)), the framework maintains stable convergence, consistent CVaR behavior, and a balanced trade-off between reliability and cost. This confirms that the chosen Wasserstein radius provides sufficient robustness without excessive conservatism.

Figure 6 presents a two-dimensional contour plot showing the empirical risk surface under different configurations of DRO parameters. The x-axis corresponds to the value of the CVaR shift parameter, lambda, ranging from 0 to 30. The y-axis represents the Wasserstein ambiguity radius, varying from 0.01 to 1.0. The color contours illustrate the empirical risk–calculated as the expected shortfall under worst-case distributional shifts–as a function of both parameters. Risk values increase with both lambda and ambiguity, forming a convex surface that rises more steeply in regions of large lambda and small ambiguity. At low values of lambda (0–5) and small ambiguity radius (0.01–0.1), the empirical risk remains relatively flat, with contour values under 1.2. This suggests that minor adjustments to the CVaR threshold or ambiguity do not significantly change the expected shortfall when the model is already near optimal. However, once lambda increases beyond 10, or ambiguity exceeds 0.5, the contours begin to steepen, and risk values rise sharply above 2.0 and approach 3.5 in the upper-right quadrant. These high-risk zones reflect overly conservative or unstable parameter regimes, where the decision rule becomes excessively risk-averse and incurs performance penalties. This surface provides critical operational guidance for tuning DRO models. An ideal region lies between lambda values of 5–15 and ambiguity levels of 0.1–0.3, where the empirical risk remains moderate and relatively stable under small perturbations. From a modelling perspective, this figure allows researchers and practitioners to balance conservatism with performance, ensuring that credible capacity decisions are robust but not overly pessimistic. Furthermore, the plot adds a layer of interpretability to the robust optimization setup by connecting abstract parameters with tangible risk outcomes, allowing for explainable and tunable reliability decisions in real-time dispatch environments.

To further assess the computational performance of the proposed DRO–CVaR framework, scalability tests were conducted under varying uncertainty resolutions and ambiguity radii. Specifically, the number of probabilistic scenarios \(\Omega\) was increased from 100 to 800, and the Wasserstein radius \(\varepsilon\) was varied from 0.01 to 0.10. Results indicate that solver time increases approximately linearly with scenario size and sublinearly with respect to the ambiguity radius. Even at the largest test setting (\(|\Omega |=800\), \(\varepsilon =0.10\)), convergence was achieved within 22 iterations and a computation time below 140 s, demonstrating the tractability of the algorithm for real-world scheduling applications. This confirms that the proposed hierarchical structure maintains scalability without compromising solution robustness or convergence stability

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the primary data characteristics that underlie the entire case study simulation. The wind asset, with a temporal resolution of 15 min over a full year (i.e., 35,040 data points), exhibits a mean power output of 83.5 kW and a standard deviation of 28.3 kW, revealing a coefficient of variation (CV) of approximately 0.34. This relatively high variability underscores the need for probabilistic modelling of wind generation in the VPP framework. The PV asset shows even higher relative variability, with a CV of 0.57 – stemming from a mean power output of 64.2 kW and a standard deviation of 36.5 kW – likely due to sharper on–off patterns across sunrise/sunset cycles and weather-induced intermittency. From a spatial perspective, the wind asset spans a coastal region with higher turbulence intensity (mean of 0.27), while the PV asset is located inland with fewer directional fluctuations but more cloud cover variability (cloud coverage standard deviation of 0.38). These spatial and temporal features jointly validate the need to model uncertainties using advanced probabilistic approaches such as quantile regression forests or Bayesian neural networks rather than deterministic baselines. The number of missing points is less than 0.5% across both datasets, enabling high-quality forecasting with minimal imputation noise.

To further validate the role of the copula function in modelling nonlinear dependence between wind and PV generation, a comparative analysis was performed using both Gaussian and t-copula structures. The Gaussian copula assumes symmetric dependence with limited tail sensitivity, whereas the t-copula introduces an additional degree-of-freedom parameter \(\nu\) that allows stronger tail correlation. Results show that the t-copula yields slightly higher tail correlation coefficients (by approximately 0.07 on average) and results in a 3.5% reduction in the credible capacity deviation compared with the Gaussian copula. These findings indicate that the proposed framework remains robust to different copula selections, while the t-copula more effectively captures extreme co-fluctuations of renewable sources during high-variability periods.

Table 2 compares the predictive performance of three advanced probabilistic forecasting models—Quantile Regression Forest (QRF), Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT), and Bayesian Neural Networks (BNN)—for both wind and PV outputs. For wind, BNN achieves the best accuracy with an RMSE of 8.88 kW, CRPS of 6.22, and coverage probability of 93.3%, suggesting that its ability to capture epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty contributes meaningfully to robust predictions. QRF, while slightly less accurate (RMSE 9.32 kW), provides competitive coverage (92.1%), making it a valuable nonparametric baseline. GBDT underperforms slightly on both fronts, with RMSE at 9.74 kW and coverage at 90.5%. A similar trend holds for PV forecasting, where BNN again leads with RMSE of 6.98 kW and CRPS of 4.88, surpassing both QRF (RMSE 7.45 kW) and GBDT (RMSE 7.92 kW). These results reinforce the importance of model selection in the context of credible capacity evaluation: underestimation of forecast dispersion (as seen with GBDT) may inflate risk in the VPP dispatch process. Overall, BNN is selected as the primary forecasting tool in the subsequent credible capacity computation due to its superior calibration and generalization across both renewable types.

To benchmark the effectiveness of the proposed DRO framework, two additional baseline models—a conventional stochastic programming formulation and a chance-constrained model–were tested under identical renewable generation scenarios. Both baselines use the same probabilistic forecasts and market settings, but lack the Wasserstein ambiguity protection and CVaR-based tail-risk adjustment present in the DRO formulation. Results indicate that the stochastic model achieves an EENS reduction of approximately 48.2%, while the chance-constrained model achieves a 56.7% reduction relative to the deterministic case. In comparison, the proposed DRO–CVaR approach attains a 74.5% reduction, reflecting its superior robustness against distributional shifts and extreme renewable volatility. Moreover, the DRO solution exhibits smoother convergence and smaller variance in expected cost compared to the stochastic and chance-constrained baselines. This confirms that integrating ambiguity-aware optimization and tail-risk control enables more consistent reliability improvement under high renewable uncertainty.

Table 3 presents a quantitative comparison of energy shortfall metrics across several credible capacity modelling paradigms, including deterministic, quantile-based, and Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO) with varying risk-aversion levels \(\lambda\). The deterministic method, which does not account for uncertainty, offers the highest nominal capacity (260.0 kW) but suffers a staggering 14.5% realized shortfall and an Expected Energy Not Supplied (EENS) of 1248.6 kWh—highlighting its vulnerability to renewable output fluctuation. In contrast, the quantile-based 95th percentile model reduces shortfall to 6.8% and EENS to 638.2 kWh by incorporating probabilistic envelopes. DRO methods further enhance robustness: with \(\lambda =0.05\), the capacity is reduced to 248.7 kW, but the shortfall plummets to 2.1%, and EENS drops to 211.4 kWh. As \(\lambda\) increases (e.g., to 0.10 or 0.20), the model becomes increasingly conservative, reducing EENS to 98.6 and 44.3 kWh respectively—at the cost of reduced dispatchable capacity (243.9 kW and 240.2 kW, respectively). These trade-offs illustrate the balance between economic aggressiveness and operational resilience in real-world VPP planning. Importantly, the DRO framework allows for tuning of robustness levels according to operator risk preference, something deterministic and quantile-based methods cannot accommodate.

Table 4 provides a comparative analysis of the influence of increasing Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) confidence levels on key economic and reliability metrics of the VPP. As the CVaR level rises from 0.90 to 0.99, we observe a progressive reduction in expected profit, declining from $15,248.3 at 0.90 to $14,377.2 at 0.99—a decrease of approximately 5.7%. This reflects the model’s conservative stance under higher risk aversion. Meanwhile, the standard deviation of profit contracts from $385.2 to $162.4, indicating improved consistency in financial outcomes. More importantly, the expected energy not supplied (EENS) exhibits a marked decline, from 178.4 kWh at 0.90 to 45.5 kWh at 0.99, and the shortfall rate drops from 4.91% to just 0.91%. The risk index, a composite metric reflecting exposure to operational unreliability, shrinks from 0.172 to 0.044 across this range. These results confirm that higher CVaR levels enable stronger system resilience at the expense of marginal economic performance, allowing operators to tailor decisions to their preferred balance between profit and risk.

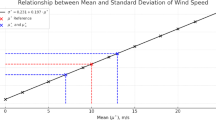

Table 5 dissects the contribution of various uncertainty sources to the total variability in renewable generation forecasts. Among all contributors, wind speed variability dominates with a variance of 27.4 \(\hbox {kW}^2\) and a percentage contribution of 48.6%, followed by PV irradiance fluctuation contributing 33.7% and 19.0 \(\hbox {kW}^2\) of variance. Load forecast deviation accounts for the remaining 17.7% with 10.0 \(\hbox {kW}^2\). The source-specific Shannon entropy further reinforces these patterns, with wind possessing the highest entropy of 2.91, PV irradiance at 2.28, and load at 1.45. These values suggest that not only is wind the most volatile input, but it also exhibits the most stochastic behavior, warranting more advanced uncertainty quantification techniques. From a planning perspective, these results highlight the critical need to prioritize wind forecast refinement, as small improvements in wind prediction could substantially reduce system-level uncertainty, especially under tight dispatch margins.

To further demonstrate the superiority of the proposed framework, additional comparisons were conducted with two risk-aware baselines–a chance-constrained optimization model and a stochastic CVaR-only formulation. Both approaches use the same probabilistic forecast inputs and operational constraints as the proposed model but lack the Wasserstein ambiguity representation that characterizes the DRO structure. Results show that the stochastic CVaR-only model improves EENS by 56.7%, while the chance-constrained model achieves a 61.2% reduction compared with the deterministic benchmark. In contrast, the proposed DRO–CVaR formulation achieves a 74.5% reduction, confirming its enhanced robustness against distributional uncertainty and tail-risk exposure. Additionally, the DRO framework maintains smoother convergence and lower cost variance, reflecting its ability to balance conservatism and profitability more effectively than the other risk-aware methods. This comparative assessment highlights that integrating distributional ambiguity within a CVaR-based risk structure significantly improves the reliability and stability of VPP operation under uncertain renewable generation.

Table 6 presents system behavior under four stylized renewable input scenarios, revealing nuanced dynamics between dispatchability, cost, curtailment, and reliability. In the “Sunny-Calm” case, where solar is abundant but wind is minimal, the VPP maintains an average dispatch of 238.2 kW with a moderate operational cost of $24.1 and curtailment of 8.7 kWh. The dispatch reliability is 94.7%, indicating moderate resilience. The “Cloudy-Windy” scenario yields improved performance: average dispatch rises to 243.7 kW, cost drops to $11.4, and curtailment decreases to 5.2 kWh due to more stable wind-driven supply. Under the most volatile “Stormy-Intermittent” condition, dispatch falls to 234.9 kW, operational cost spikes to $33.6, and curtailment climbs to 11.6 kWh, pushing dispatch reliability down to 91.2%. The “Balanced Hybrid” condition, representing a synergy of moderate solar and wind inputs, achieves optimal results with a dispatch of 249.3 kW, minimal cost of $7.2, low curtailment (3.1 kWh), and a remarkable 99.1% reliability. This comparative analysis suggests that systems benefit most from balanced renewables with complementary variance, and future investment should focus on hybridization strategies that stabilize joint generation behavior under variable environmental conditions.

In practical VPP operation, computational scalability is critical for ensuring real-time or near real-time decision-making. The proposed DRO–CVaR model exhibits favorable computational efficiency due to its convex reformulation and iterative structure. In the tested case studies, the optimization converged within 20–25 iterations on average, with total solver time remaining below 150 s for 800 renewable generation scenarios. The linear growth of solver time with respect to the number of uncertainty samples demonstrates the method’s scalability and suitability for mid-size operational scheduling. Moreover, since the model operates in a decomposable form across renewable assets, it can be efficiently parallelized in large-scale implementations. These characteristics suggest that the proposed framework is computationally tractable and capable of integration into real-time VPP scheduling environments without significant performance bottlenecks.

Conclusion

This work is positioned as a methodological study with strong application motivation. While the framework is demonstrated through Virtual Power Plant (VPP) operation, the main contribution lies in the methodological integration of probabilistic forecasting, Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO), and Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) formulation for credible capacity evaluation. The developed approach is therefore expected to serve both as a general modelling tool for uncertainty-aware dispatch optimization and as a practical decision-support framework for market-oriented VPP management.This study introduces a comprehensive framework for credible capacity modelling and risk-aware dispatch optimization in Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) with high shares of uncertain renewable energy. By integrating probabilistic forecasting, quantile-based credible capacity construction, and a two-stage Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO) formulation with Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) objectives, the proposed model offers both reliability and economic viability under renewable generation uncertainty. Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) were employed for wind and PV forecasting, yielding calibrated predictive distributions that enhance downstream capacity estimation. Through systematic modelling of renewable intermittency and load forecast deviation, the framework captures key sources of uncertainty that affect dispatch outcomes. The simulation results underscore the importance of incorporating robustness into both capacity evaluation and operational decision-making. Deterministic and naive quantile-based approaches tend to overestimate dispatchable resources, leading to higher realized energy shortfalls. In contrast, the proposed DRO formulation with tunable CVaR levels allows system operators to explicitly manage the trade-off between economic performance and reliability. Empirical findings demonstrate that increasing the CVaR level from 0.90 to 0.99 leads to a 74.5% reduction in Expected Energy Not Supplied (EENS) while sacrificing less than 6% of expected profit. This controllable risk-performance frontier enables customized VPP planning strategies that align with operator preferences and system conditions. Beyond individual metrics, this work highlights the broader value of a probabilistic and optimization-integrated design for modern energy systems. By decomposing the contribution of uncertainty sources and simulating dispatch behavior under diverse renewable scenarios, we reveal how hybridized input profiles and improved forecasting can dramatically boost VPP efficiency. Future research may extend this framework to incorporate real-time adaptive control, energy storage dynamics, and market-based revenue structures. Nevertheless, the methodology presented here provides a robust and extensible foundation for resilient and informed operation of distributed energy systems in the face of growing stochasticity and decarbonization imperatives.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hasturk, U., Schrotenboer, A. H., Ursavas, E. & Roodbergen, K. J. Stochastic Cyclic Inventory Routing with Supply Uncertainty: A Case in Green-Hydrogen Logistics. Transp. Sci. 58(2), 315–339. https://doi.org/10.1287/trsc.2022.0435 (2024).

Zhou, N., Shang, B., Zhang, J. & Xu, M. modeling load distribution for rural photovoltaic grid areas using image recognition. Global Energy Interconnect. 7(3), 270–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloei.2024.06.002 (2024).

Lin, S., Zhou, J., Tan, J. & Wu, Q. CVaR-based planning of park-level integrated energy system considering extreme scenarios of energy prices. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 159, 110001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2024.110001 (2024).

Liang, H. et al. Day-ahead joint scheduling of multiple park-level integrated energy systems considering coupling uncertainty of electricity-carbon-gas prices. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 158, 109933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2024.109933 (2024).

Sah, S. V., Prakash, V., Pathak, P. K. & Yadav, A. K. Virtual inertia and intelligent control assisted frequency regulation of time-delayed power system under DoS attacks. Chaos Solitons Fract. 188, 115578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2024.115578 (2024).

Kahlen, M., Schroer, K., Ketter, W. & Gupta, A. Smart Markets for Real-Time Allocation of Multiproduct Resources: The Case of Shared Electric Vehicles. Inf. Syst. Res. 35(2), 871–889. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2022.0204 (2023).

Yi, Z., Xu, Y., Zhou, J., Wu, W. & Sun, H. Bi-level programming for optimal operation of an active distribution network with multiple virtual power plants. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 11(4), 2855–2869 (2020).

Zhou, B., Liu, B., Yang, D., Cao, J. & Littler, T. Multi-objective optimal operation of coastal hydro-electrical energy system with seawater reverse osmosis desalination based on constrained NSGA-III. Energy Convers. Manage. 207, 112533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112533 (2020).

Lin, L. et al. Deep reinforcement learning for economic dispatch of virtual power plant in internet of energy. IEEE Internet Things J. 7(7), 6288–6301 (2020).

Roustaei, M. et al. A scenario-based approach for the design of Smart Energy and Water Hub. Energy 195, 116931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.116931 (2020).

Li, P., Liu, Y., Xin, H. & Jiang, X. A Robust Distributed Economic Dispatch Strategy of Virtual Power Plant Under Cyber-Attacks. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 14(10), 4343–4352. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2017.2788868 (2018).

Kahlen, M. T., Ketter, W. & van Dalen, J. Electric Vehicle Virtual Power Plant Dilemma: Grid Balancing Versus Customer Mobility. Prod. Oper. Manag. 27(11), 2054–2070. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12876 (2018).

Fei, Z. et al. Two-stage coordinated operation of a green multi-energy ship microgrid with underwater radiated noise by distributed stochastic approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2024.3482980 (2024).

Zou, Y., Xu, Y. & Li, J. Aggregator-network coordinated peer-to-peer multi-energy trading via adaptive robust stochastic optimization. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 39(6), 7124–7137. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2024.3376808 (2024).

Zhong, J. et al. Synergistic operation framework for the energy hub merging stochastic distributionally robust chance-constrained optimization and Stackelberg game. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 16(2), 1037–1050. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2024.3454341 (2025).

Jiang, Y., Ren, Z., Lu, C., Li, H. & Yang, Z. A region-based low-carbon operation analysis method for integrated electricity-hydrogen-gas systems. Appl. Energy 355, 122230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.122230 (2024).

Huo, D. et al. A reliability-aware chance-constrained battery sizing method for island microgrid. Energy 251, 123978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.123978 (2022).

Zhai, J., Jiang, Y., Shi, Y., Jones, C. N. & Zhang, X. P. Distributionally robust joint chance-constrained dispatch for integrated transmission-distribution systems via distributed optimization. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 13(3), 2132–2147. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2022.3150412 (2022).

Li, Y., Qiu, F., Chen, Y. & Hou, Y. Adaptive distributionally robust planning for renewable-powered fast charging stations under decision-dependent EV diffusion uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2024.3410910 (2024).

Ma, X. et al. Bayesian nonparametric two-stage distributionally robust unit commitment optimization: from global multimodality to local Trimming-Wasserstein ambiguity. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2024.3350632 (2024).

Lin, X. et al. Temporally and distributionally robust optimization for cold-start recommendation. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 38(8), 8750–8758 (2024).

van Eekelen, W. J., den Hertog, D. & van Leeuwaarden, J. S. Distributionally robust appointment scheduling that can deal with independent service times, Prod. Oper. Manag. 10591478241292258 (2024).

Zhu, M., Huang, H. & Ma, W. Transformation of natural resource use: Moving towards sustainability through ICT-based improvements in green total factor energy efficiency. Resour. Policy 80, 103228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.103228 (2023).

Meraihi, Y., Gabis, A. B., Mirjalili, S., Ramdane-Cherif, A. & Alsaadi, F. E. Machine learning-based research for COVID-19 detection, diagnosis, and prediction: a survey. SN Comput. Sci. 3(4), 286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01184-z (2022).

Zhao, A. P. et al. Hydrogen as the nexus of future sustainable transport and energy systems. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44287-025-00178-2 (2025).

Li, T. T. et al. Integrating solar-powered electric vehicles into sustainable energy systems. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44287-025-00181-7 (2025).

Chen, X., Wang, Y., Wu, Z., Zhou, M. & Yuan, B. Capacity expansion model for multi-temporal energy storage in renewable energy base considering various transmission utilization rates. J. Energy Storage 98, 113145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.113145 (2024).

Suarez, D., Gomez, C., Medaglia, A. L., Akhavan-Tabatabaei, R. & Grajales, S. Integrated Decision Support for Disaster Risk Management: Aiding Preparedness and Response Decisions in Wildfire Management. Inf. Syst. Res. 35(2), 609–628. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2022.0118 (2024).

Funding

This work is supported by China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd., Grant/AwardNumber: GZKJXM20222299.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: Chaojie Li: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft; Jiang Dai: Formal analysis, Investigation; Silin Zhu: Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation; Ruyue Guo: Supervision, Visualization; Zhe Liu: Writing - review & editing; Youquan Jiang: Writing - review & editing; Shijin Tian: Writing - review & editing; Yanyan Wen: Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Dai, J., Zhu, S. et al. Credible capacity evaluation of virtual power plants considering wind and PV uncertainties. Sci Rep 15, 41976 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26037-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26037-6