Abstract

Yam (Dioscorea spp.) is a tuber-producing crop and an important staple in the tropics and subtropics, valued for its nutritional, health and sociocultural relevance. However, there is limited awareness of its nutritional and health benefits among local communities in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), prompting its underutilization. This study aimed to (a) document the diversity of cultivated and semi-domesticated yam species in eastern DRC; (b) explore indigenous knowledge on their nutritional and health benefits; and (c) assess the nutrient composition and antioxidant activity of major yam species consumed in the region. Data collection involved ethno-botanical surveys, plant specimen collections, interviews with 123 community members, and physicochemical profiling using standard analytical methods. Ten yam species were documented in eastern DRC, including two domesticated species, with distribution patterns shaped by biophysical conditions and cultural factors. Species richness was higher in highland forest zones compared to lowland savannas. Local communities use yam to treat more than 15 health conditions, including stomach pains, food intoxications, skin wounds and infections, reproductive abnormalities, immune system deficiency, respiratory challenges, diabetics, etc. Physicochemical composition analysis revealed interspecific variations potentially contributing to their nutritional and therapeutic relevance by local communities. Notably, Dioscorea dumetorum tubers exhibited the highest protein content (8.7 g/100 g) and potassium concentration (240.2 mg/100 g), D. praehensilis was rich in carbohydrates (80.9 g/100 g), and D. bulbifera had highest calcium concentration (40.1 mg/100 g), underscoring the yam nutritional significance in the local diet. All yam species encompassed saponins, terpenoids, and alkaloids, though D. praehensilis and purple D. alata had the highest antioxidant activity that exceeded 90% inhibition level. These findings provide valuable insights on yam diversity and their potential to sustain nutritious healthy diets in eastern DRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Yam (Dioscorea spp.) is a generic name referring to approximately 600 species of the Dioscorea genus (Plum. ex L.), cultivated for its starchy underground or aerial tubers in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, and America1. Among these species, only 11 are cultivated for food and income, while others remain in wild undomesticated but often used by hunter-gathers to mitigate food shortages during lean periods and for traditional rituals and medicine2,3,4,5. Beyond its role as a staple food, substantial evidence highlights yam’s nutritional and therapeutic contributions to human health. It serves as an important source of dietary energy, dietary fiber, protein, vitamins (C and B), essential minerals (potassium, manganese, calcium, etc.), while maintaining a low fat content6,7,8. These nutrients support key physiological functions, including energy metabolism, nervous system health, muscle function, blood pressure, blood sugar level regulation, bone health, intestinal transit regulation, diabetics, and satiety7,9,10. Besides, yam is deeply embedded in cultural and spiritual traditions of societies who depends on it, often considered as a sacred crop symbolizing fertility, prosperity, and connection to the land2. Yam also contains bioactive phytochemicals with antioxidant activity, including polyphenols, sterols, diosgenin, flavonoids, saponins, alkaloids, and terpenoids. These compounds exhibit free radical scavenging activity, reducing oxidative stress and contributing to the prevention and treatment of a range of health conditions in traditional and modern medicines, depending on their specific chemical nature, concentration, and bioavailability10,11,12,13,14.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is a biodiversity hotspot15, home to over 10,000 plant species, including 23 Dioscorea species from different sections16. Several Dioscorea species serve as important food crops across various regions of DRC, cultivated for their starchy underground tubers and aerial bulbils17,18,19. However, research on Dioscorea species remains limited in eastern DRC, particularly in South-Kivu province, resulting in a poor valuation and understanding of yam species diversity in the region. This knowledge gap has led to species misidentifications among both farmers and the local scientific community, with different Dioscorea species and varieties often sharing the same vernacular names19. There is, therefore, an urgent need for comprehensive yam characterization to support ongoing genetic improvement efforts. Additionally, low awareness of the nutritional and health benefits of yam among the local urban and rural consumers poses a significant challenge to its wider production and utilization in eastern DRC. A World Food Program (WFP) initiative promoting indigenous foods in Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) countries highlighted the importance of nutritional education in increasing the awareness of such foods in local diet systems. However, for such efforts to be effective, messaging must be grounded on sound scientific knowledge, while being accessible and culturally relevant capable of stimulating positive behaviours at the local level20. Information on yam species richness, their nutritional, phytochemical, and antioxidant compositions would be necessary for biodiversity conservation efforts, plant breeding, awareness campaigns vis-à-vis yam nutritional and health benefits, and for processing and value addition initiatives.

This study, therefore, aimed at raising awareness on the nutritional and therapeutic benefits of major cultivated and wild yam species in eastern DRC. It specifically sought to (a) inventory cultivated and semi-domesticated yam species in South-Kivu; (b) document local knowledge on their nutritional and health benefits; and (c) assess nutrient composition and antioxidant activity of major local yam species.

Materials and methods

Study site

Ethno-botanical surveys were conducted in Kabare and Kalehe territories in the highlands of the South-Kivu province, eastern DRC (Table 1). These are territories neighboring the Kahuzi Biega National Park where autochthonous pygmies are located, an ethnic group depending on the forest for food, income, and medication21. In addition to autochthonous pygmies, other ethnic groups in the surveyed areas include Bashi, Bahavu, and Batembo all having yam as a cultural and social symbol. Administrative zones directly involved in the ethno-botanical study are Irhambi-Katana, Bugorhe, and Miti (Kabare) and Bitale, Kalima, Buloho, and Kalonge (Kalehe). Villages harboring autochthonous pygmies, among those surveyed, are Buyungule (Miti) and Cahoboka (Irhambi-Katana) in Kabare and Hembe (Bitale) in Kalehe territory. Regardless of the ethnic group, agriculture is the main economic activity in these areas, dominated by cassava, banana, common bean, sweet potato, and yam as staple crops while tea, coffee, and cinchona dominate industrial perennial crops19. Plant specimen collections were extended to other South-Kivu territories such as Walungu, Idjwi, Mwenga, Uvira, and Fizi (Fig. 1) to gain insights on yam diversity and spatial distribution across the province. For further details on these territories’ biophysical characteristics, see Mondo et al.19,22.

Yam tubers used for physicochemical analyses were collected from the Université Evangélique en Afrique (UEA) Experimental Site located at Kashusha (28°47’ 45.9” E, 02°19’0.02” S, at 1717 m above sea level), in Kabare territory, eastern DRC. This experimental site experiences a bimodal tropical mountain climate (Aw3) with a total rainfall amount of ~ 1500 mm and an average temperature of 19.2 °C for the 2023–2024 cropping season. The site soils are of ferralitic, humus-bearing and clayey nature, underlain by basaltic rocks. Further details on Kashusha soil characteristics are provided in Table S1. The soil is slightly acidic (5.6), which is correlated with a high organic matter content. The carbon content and the essential bases for plant growth are all within the acceptable range for yam cultivation. These bases are available in the soil solution due to a slightly higher cation exchange capacity compared to typical tropical soils. The soil texture is clay loam according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s textural triangle classification. Such soil texture is characterized by good water retention, ensuring adequate plant hydration. It also tends to retain nutrients better than other soil types, such as sandy soils, while maintaining ease of cultivation. The total nitrogen content remains slightly low. The calculation of the base saturation percentage (TSB) also indicates that the soil is moderately to fairly fertile (Table S1).

Methods

Inventory of yam species in eastern DRC

Plant materials were collected under the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing and were only used for research purposes. To inventory yam species across surveyed villages of eastern DRC, a 30-day field mission was conducted using two methods. Firstly, the taxonomic collection method, which involved visiting villages using a transect walk as defined by Dery et al.25, following horizontal axes. Plant specimen (made of tubers or plantlets) of wild and cultivated yams were collected for ex-situ characterization at the Lwiro Natural Science Research Centre (CRSN Lwiro), in Kabare territory. Herbarium samples were also collected using secateurs and transported to the laboratory in presses for drying, identification, and confirmation at the CRSN Lwiro herbarium. Formal identification of the plant material used in this study was undertaken by qualified personnel from the CRSN Lwiro herbarium (Mr. J.C. Ithe Mwanga-Mwanga) where voucher specimen of this material has been deposited in a publicly available herbarium. Provisional voucher/sample identifiers under which these specimens are deposited at the CRSN Lwiro Herbarium are as follows: LW_UEA5 for Dioscorea dumetorum (Kunth) Pax, LW_UEA2 for Dioscorea bulbifera L., LW_UEA1G for Dioscorea praehensilis Benth., LW_UEA1/MMP1 for Dioscorea minutiflora Engl., LW_UEA35 for Dioscorea quartiniana A.Rich., LW_UEA22 for Dioscorea schimperiana Hochst. ex Kunth, LW_UEA24 for Dioscorea semperflorens Uline, and LW_UEA75/24 for Dioscorea alata L. Updated scientific names and authors were verified for all species at https://powo.science.kew.org/. To these plant specimens were added those previously collected across all other South-Kivu territories19 that were being maintained at the UEA Experimental Site located at Kashusha.

Assessment of local knowledge on nutritional and health benefits of yams

Ethnobotanical surveys were conducted from October 2023 to January 2024, involving visiting and interviewing local ethnic communities about their knowledge on yam diversity (in terms of species), as well as its food, medicinal, or cultural importance. Formal and informal interviews were conducted with 123 community members with varying ethnic backgrounds. Respondents were sampled using a chain-reference sampling technique, also known as snowball sampling method26 while sample size was defined using a probabilistic saturation sampling method27. The study protocol was approved by the UEA Interdisciplinary Centre of Ethical Research (CIRE), Ref: CNES 039/DPSK/322PP/2023. We obtained verbal informed consent from all resource-persons and community members before interviews after ensuring the confidentiality in use of data collected and explaining the study objectives, as approved and directed by the above Institutional Review Board. Whenever possible, surveys were coupled with germplasm collection (including plantlets or tuber fragments) for ex-situ characterization. Collected planting materials were enveloped in paper bags with small air holes.

Assessment of phytochemical compositions of major yam species

Plant material. Laboratory assays involved five cultivars from four yam species that are local to the South-Kivu province. Of these four yam species, two were semi-domesticated, namely D. praehensilis Benth., locally known by its generic name as Birongo (represented by the Kanyaburhole variety) and D. bulbifera L. (represented by the wild Mange variety, for which underground and aerial tubers were collected). The two cultivated yam species included D. alata L. (represented by white and purple Kitende varieties) and D. dumetorum (Kunth) Pax, known locally as Maliga. Further details on used plant materials are provided in Table 2. These plant materials were sampled from the yam germplasm maintained at the UEA experimental site with a backup at the CRSN Lwiro. Planting at the Kashusha site was done in November 2023. Recommended field management was followed, including ridging, individual plant staking, fertilizer application, supplemental irrigation, regular weeding, etc. while sample materials (tubers) used for analyses were harvested in late May 2024.

Sample preparation. All collected tubers were weighed, peeled, cut into slices, and then dried in an electric dryer. Dry slices were ground using a blender. The powder obtained was stored in hermetically sealed jars (tightly closed plastic boxes) at room temperature and in a dry place. This powder was thereafter shipped to Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT)’s Food Technology laboratory, in Kenya, for physicochemical analyses.

Physicochemical analyses. Proximate analyses and energetic values (moisture, protein, fat, crude fiber, total available carbohydrates, and ash) were determined according to the methods by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists28. Mineral contents (zinc, potassium, magnesium, iron, and calcium) were determined by dry ashing and atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS) (Shimadzu AA-7000), according to AOAC29 and Osborne and Voogt30. The β-carotene content was determined from approximately 2 g of fresh tubers following analytical methods suggested by Barba et al.31. Qualitative phytochemical analyses included tests for the presence of alkaloids, terpenoids (Salkowski test), and saponins. Among quantitative phytochemicals, condensed tannins were assayed according to the vanillin-hydrochloric acid method32,33 while flavonoids were determined using the method of Harborne and Williams34 and the aluminum chloride colorimetric method35 for qualitative and quantitative analyses, respectively. On the other hand, the total polyphenol was determined using the method of Waterman and Mole36, with slight modification. The radical scavenging activities of the plant extracts against 2, 2-Diphenyl-1-picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) radical (Sigma-Aldrich) were determined by UV spectrophotometer at 517 nm37. The following concentrations of the extracts were prepared, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 2.0 and 5 mg/mL in methanol (Analar grade). Vitamins C were used as the antioxidant standard at concentrations of same as the extract concentrations. More detailed methodology on physicochemical analyses is provided as Supplementary File 1.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed for data collected from the ethnobotanical surveys; qualitative and quantitative data were summarized as frequencies and means ± standard deviations, respectively. ArcGIS 10.7 Esri-TM software was used to map yam species’ spatial distribution across surveyed areas of the South-Kivu province. Floristic similarity and diversity indices (Shannon-Weiner (H’), Pielou’s evenness or equitability (J), and Dominance (D)) across surveyed territories were computed using Paleontological statistics software (PAST38. Alternative to Student’s t test, the Wilcoxon non-parametric test was applied to assess differences in diversity between Kabare and Kalehe, two locations covered by the taxonomic collection method. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was applied on physicochemical data to determine significant differences among yam species for all quantitative variables. Means of physicochemical data were separated using post-ANOVA Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at 5% p-value significance level, using R 4.1.239.

Results and discussion

Domesticated and semi-domesticated yam species in eastern DRC

Through extensive surveys and field observations across the study area, we collected 515 morphotypes representing 10 different Dioscorea species, of which Dioscorea dumetorum (Kunth) Pax (39.6%), D. praehensilis Benth. (18.8%), D. bulbifera L. (18.2%), and D. quartiniana A.Rich. (8.7%) were the most predominant. Other yam species identified in South-Kivu are D. alata L., D. minutiflora Engl., D. schimperiana Hochst. ex Kunth, D. semperflorens Uline, D. triphylla G.W.Schimp. ex A.Rich., and D. paleata Burkill. Morphological features of inventoried yam species are provided at Fig. 2. Taxonomic diversity analysis in Kabare and Kalehe revealed moderate diversity based on the Shannon-Wiener index (H’=1.78–2.02); with a Dominance index (D) varying between 0.15 and 0.25 and a Pielou equitability index (J) of 0.74 to 0.88, indicating well-balanced species distribution. No significant differences existed between Kabare and Kalehe (p = 0.096), implying that species were evenly distributed across both sites. At the provincial scale, species richness was highest in forest zones compared to savanna ecosystems (Fig. 3). This diversity in consumed yam species is likely linked to the region’s ethnic heterogeneity and diverse biophysical landscapes19, to the extent that, some species are exhibiting narrow distribution and are being consumed exclusively by specific communities. For instance, D. dumetorum is mostly cultivated by the Bashi, Bahavu, and Batembo ethnic groups in highlands and forest areas, while D. alata is predominant among the Babembe and Bafuliru ethnic groups in the lowland savannas of Uvira and Fizi (near the Lake Tanganyika). Meanwhile, wild and semi-domesticated yams such as D. bulbifera and D. praehensilis are predominantly consumed by Batwa pygmies living close by the Kahuzi Biega National Park21.

Historical account suggests that D. alata was introduced to Africa via Madagascar and Zanzibar coast by invading or colonizing Asiatics16, which could explain its presence in regions adjacent to the Lake Tanganyika, a historical trade and migration route in the DRC. Notably, an unexpected discovery of a yellow flesh D. alata landrace, locally called “Bigedja” on Idjwi Island in the Lake Kivu, raises questions about alternative introduction pathways. This variation in yam diversity across ethnic groups and agroecological zones underscores the importance of tailoring promotion efforts to local needs and preferences and environmental conditions. The only species widely known and consumed by all ethnic groups is D. dumetorum though ethnic groups seemed attached to particular landraces, making that D. dumetorum landraces are often designated by the origin or the ethnic group that maintain them19. Given this diversity, molecular fingerprinting is essential to ascertain species identity and refine genetic relationships among species and landraces grown by ethnic groups across the South-Kivu province.

Morphological differences among some yam species inventoried in South-Kivu: (A) D. dumetorum, (B) D. bulbifera, (C) D. paleata, (D) D. semperflorens, (E) D. schimperiana, (F) D. minutiflora, (G) D. quartiniana, (H) D. praehensilis, (I) D. dumetorum, (J) Pink and (K) white D. praehensilis, (L) D. bulbifera underground tuber, (M), (N), (O) purple, yellow, and white D. alata, respectively.

Socio-demographic information

The socio-economic characteristics of the surveyed population are detailed in Table S2. The surveyed population was dominated by men (60%) and middle-aged adults (40%), with farming as primary economic activity (95%), although some engaged in non-farm income-generating activities such as handicrafts and petty trading. The surveyed population had low levels of formal education, with over 85% having never attended school and 12% reaching only primary education level. Household sizes were typically large with 5–10 family members and nearly all participants lived far below the international poverty line, earning less than 1$ income a day. Most community members were affiliated with local community associations.

Yam consumptions in households were primarily derived from farming (62%), with smaller contributions from local markets (13%), forests (7.5%), or combination of both forests and farming (15%). When cultivated, yam is predominantly intercropped with other staple crops such as cassava, beans, taro, sweet potatoes, and maize, highlighting the yam integration into traditional agroecosytems19. Yam is mainly consumed boiled, the cooking time varying with species. It is noteworthy that though local communities are less aware of anti-nutritional factors in yam, cooking time varies with species. For instance, it takes hours to cook D. dumetorum while local D. alata varieties are safe to eat in less than an hour since the population perceives them less poisonous.

Local knowledge on nutritional and health benefits

Local knowledge on nutritional and health benefits of yam was mainly assessed among autochthonous Pygmies and other ethnic groups residing near Kahuzi Biega National Park in Kabare and Kalehe territories. Despite the cultivation and consumption for food, only one-third (33%) of respondents were aware of the therapeutic benefits of yam, most associating it primarily with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stomach ache treatment. Local communities use yams to treat more than 15 health conditions, including stomach pains and food intoxications, skin wounds and infections, glycemic index, reproductive abnormalities, immunity system deficiency, respiratory challenges, diabetics, etc. though the effectiveness vary with used yam species and treatment procedures (Table 3). Yam plant parts involved in traditional medicine are boiled tubers, boiled leaves, and crushed leaf juice.

A recent study that listed yam among non-timber forest products in South-Kivu highlands reported that a third of the population around the Kahuzi Biega National Park use yam to improve digestion, to prevent prostatitis or as an anti-malaria treatment, while more than half knew yam as a type 2 diabetes’ prevention measure21. These anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial potentials, and their involvement in treating dozens of health conditions were also reported by several scholars8,9,10,12,13,14,40. It is noteworthy that traditional medicine is often the only healthcare available in some remote areas of South-Kivu where resource-poor households cannot afford modern medical expenses21. Of the ten listed yam species, D. dumetorum and D. bulbifera were more popular in traditional pharmacopeia in which different plant parts are used such as leaves, tubers, or bulbils either fresh, boiled, crushed, peeled, or incinerated. Even within a species, specific cultivars were recommended for particular health conditions (Table 3). This was particularly the case for D. dumetorum for which the yam origin was the main selection criterion, the origin being tightly associated with the genetic background of the cultivar being maintained by a particular ethnic group. Such effect of the genotype on D. dumetorum antidiabetic and antioxidant profiles was also reported by Aiyedun et al.41 in Nigeria. Laboratory experiments are necessary to confirm these perceptions by South-Kivu communities to determine bioactive compounds holding curative power for each species, to improve success rate of traditional medicine, to mitigate safety issues.

Yam is also used in traditional rituals; for the Batwa pygmies, yams are seen as a means of communicating with their ancestors. They prepare wild yams and eat them in their traditional caves. For the Bashi tribe, boiled yams are used as a means of defense and to have the power to win a trial. Therefore, in some conservative zones, people carrying yams are not allowed to visit prisoners worrying that it will confer them supernatural power for release. For the Tembo tribe, the dry yam vine is used in the enthronement of the king to symbolize strength and power. Culturally yams are used to welcome high profile visitors across ethnic groups. Some wild yams such as D. praehensilis are believed to protect against witchcraft. Use of yam for rituals have been widely reported by the literature2.

Physicochemical compositions of major yam species

Proximate composition and energy content

The physicochemical composition of yams varied significantly across species (p < 0.01, Table 4), with distinct differences observed in moisture, ash, protein, fiber, fat, carbohydrate, and energy. Dioscorea dumetorum exhibited the highest protein content (8.7 g/100 g), followed by purple D. alata (6.2 g/100 g) whereas white D. alata had the lowest protein content (4.3 g/100 g). Ash content was highest in white D. alata (2.9 g/100 g), followed by D. bulbifera’s underground (2.6 g/100 g) and aerial bulbils (2.3 g/100 g), while D. dumetorum had the lowest (2.0 g/100 g). Fiber content was the highest in D. dumetorum (4.2 g/100 g), followed by D. bulbifera aerial bulbils (3.4 g/100 g), whereas D. praehensilis had the lowest (1.2 g/100 g). Fat content was the highest in D. praehensilis (1.9 g/100 g) and purple D. alata (1.8 g/100 g). In terms of carbohydrate, D. praehensilis had the highest content (80.9 g/100 g), followed by white D. alata (79.4 g/100 g) and D. bulbifera underground tubers (78. 9 g/100 g). Energy content was also the highest in D. praehensilis (358.23 Kcal/100 g) and white D. alata (349.06 Kcal/100 g).

This richness of yams in proteins, fiber, and energy qualify them as nutritious healthy foods. For instance, yam contents in proteins and carbohydrates are superior to values reported by Irakiza et al.42 for cassava, the major tuber crop in eastern DRC. High fiber content highlights yam importance for digestive health, as fiber improves intestinal function and helps regulate intestinal transit. Yam low fat could explain its potential to regulate glycemic index and blood sugar among insulin-dependent patients40.

Mineral composition of yams

Except for the zinc, other mineral and β-carotene contents differed significantly among yam species (p < 0.01, Table 5). Dioscorea dumetorum exhibited the highest potassium content (240.2 mg/100 g), whereas D. bulbifera underground tubers had the lowest (107.4 mg/100 g). The highest magnesium content was recorded on D. praehensilis (125.9 mg/100 g) and D. dumetorum (121.84 mg/100 g) while white D. alata had the lowest amount (71.0 mg/100 g). A similar trend was observed for iron concentration; with D. praehensilis having the highest level (5.2 mg/100 g), followed by D. bulbifera aerial bulbils (5.2 mg/100 g), whereas white D. alata had the lowest (3.9 mg/100 g). The calcium content was highest in D. bulbifera underground tubers (40.1 mg/100 g), followed by the white D. alata (31.8 mg/100 g), while purple D. alata had the lowest calcium content (11.2 mg/100 g). In terms of β-carotene, D. bulbifera underground tubers (1.9 mg/100 g) and purple D. alata (1.8 mg/100 g) contained the highest levels, whereas D. praehensilis had the least amount (0.5 mg/100 g). High contents in iron, zinc, and β-carotene as compared to cassava showed yam potential to alleviate hidden hunger that constitutes a major public concern, especially among women and children, in eastern DRC21,42. Besides, its high content in potassium contributes to its potential in regulating glycemic index and blood sugar among insulin-dependent patients40. Differences in mineral compositions among species show that each yam species has a unique mineral profile, which may influence their nutritional and therapeutic use. Yam species richness in potassium and magnesium, such as D. dumetorum and D. praehensilis, may be particularly beneficial for cardiovascular health. Similarly, species with high iron contents, such as D. praehensilis could prevent anemia43.

Qualitative phytochemical composition of yams

Qualitative phytonutrient composition analyses showed high levels of alkaloids, terpenoids, and saponins in all test yam species though each species had a unique profile of bioactive compounds, which may influence their potential use in nutrition and medicine. Saponins and terpenoids were in largest amounts in purple D. alata and D. dumetorum and lowest in D. bulbifera underground tubers. These yam species rich in saponins and terpenoids could be particularly beneficial for their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties8,10,40. Purple D. alata had as well the highest amounts of alkaloids while all other species had this phytochemical in moderate amounts. Richness in alkaloids could confer purple D. alata interesting pharmacological applications. It is noteworthy that the balance between these bioactive compounds is crucial to maximizing health benefits, implying that diversified consumption of different yam species could offer a full range of nutrients and bioactive compounds, contributing to better overall health44. Other bioactive compounds with health benefits found in yams include Diosgenin, Dioscin, Protodioscin, Gracillin, Protogracillin, etc14., though they were not assessed in this study.

Phytonutrient composition of yams

Quantitative phytochemical compositions varied significantly with yam species (p < 0.001, Table 6), prompting an influence on their nutritional and health benefits. Flavonoid contents were highest in purple D. alata (0.96 mg/100 g), followed by D. dumetorum (0.85 mg/100 g) while D. bulbifera underground tubers had the lowest concentration (0.23 mg/100 g). The trend was similar for phenols as purple D. alata (0.99 mg/100 g) and D. dumetorum (0.61 mg/100 g) outperformed other species, with D. bulbifera aerial and underground tubers recording the lowest amounts (0.33 mg/100 g). It is noteworthy that species rich in flavonoids and phenolic compounds, such as purple D. alata, could offer better protection against cardiovascular disease and oxidative stress. However, species with high tannin content, such as D. bulbifera aerial bulbils (252.14 mg/100 g) and white D. alata (252.01 mg/100 g), may require specific preparation to minimize the potential tannins effects on essential minerals’ bioavailability43.

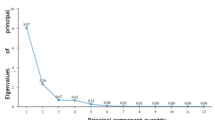

Free radical scavenging activity

Test yam species had varying antioxidant capabilities (Fig. 4). For instance, D. praehensilis and purple D. alata had very high antioxidant activities, almost reaching the level of vitamin C, with inhibition levels exceeding 90% at higher concentrations. Such species, with higher inhibition levels, could be valuable natural sources of antioxidants for food or medical applications45. Dioscorea bulbifera aerial bulbils and D. dumetorum had moderate antioxidant activity while white D. alata and D. bulbifera underground tubers showed lower inhibitions, indicating a lesser capacity to neutralize free radicals.

Summary results of yam diversity, nutritional and health benefits in eastern DRC. Dd: D. dumetorum, Dpr: D. praehensilis, Db: D. bulbifera, Dq: D. quartiniana, Da: D. alata, Dse: D. semperflorens, Dsc: D. schimperiana, Dm: D. minutiflora, Dpa: D. paleata. Letters in brackets refer to D: domesticated, SD: semi-domesticated and W: wild.

Study limitations and prospects

Identification of species were based on morphological features that may lead to misclassification of species with limited distinctive morphological characteristics. Molecular fingerprinting is essential to ascertain species identity and refine genetic relationships among species and landraces grown by ethnic groups across the South-Kivu province. Future studies should complement perceptions of local communities on health benefits by laboratory experiments to determine bioactive compounds holding curative power for each species, to improve success rate of traditional medicine, and to mitigate safety issues. Special attention should be oriented towards the effectiveness of local yam species to treat chronic diseases such as diabetes and high blood pressure, a major public health concern in eastern DRC46. Investigating additional agroecological zones with different ethnic groups could enrich the list of consumed yam species and related nutritional, health, and cultural significance. Due to limited funds, the physicochemical composition analysis was only performed on the four most popular yam species.

Conclusions

This study associated field observations, local knowledge, and laboratory essays to generate sound scientific knowledge on yam diversity, nutritional and health benefits of yam in eastern DRC. We documented 10 cultivated and semi-domesticated yam species consumed in eastern DRC, with distribution patterns shaped by biophysical conditions and cultural factors. These species are not only sources of food and income, but also play an important role in traditional medicine as they are involved in treating dozens of health conditions (Fig. 5). Physicochemical analyses showed that local yam species are valuable sources of nutrients and bioactive compounds that contribute to nutritious healthy diets in the region. However, nutritional and health benefits differ with yam species; implying that diversifying consumption with different yam species could offer a full range of nutrients and bioactive compounds to contribute to better overall health. While purple D. alata and D. dumetorum are particularly rich in bioactive compounds and secondary metabolites with limited anti-nutritional factors, D. praehensilis and purple D. alata demonstrated highest antioxidant activity. These potentials positioned these yam species as valuable inputs for pharmaceutical applications. Additional investigations are necessary to (1) extent physicochemical analyses to other identified yam species and varieties within species in the region; (2) extract bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical use; (3) assess local yam processing methods’ impacts on yam nutritional value, phytonutrient content, and antioxidant activity; and (4) develop domestication protocols for more promising wild and semi-domesticated yam species to ease pressure on natural forest reserves.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variance

- AOAC:

-

Association of Official Analytical Chemists

- CRSN:

-

Centre de Recherche en Sciences Naturelles

- DRC:

-

Democratic Republic of Congo

- LSD:

-

Least Significant Difference

- UEA:

-

Université Evangélique en Afrique

References

Coursey, D. G. Yams. An account of the nature, origins, cultivation and utilisation of the useful members of the Dioscoreaceae. Rhind, D., Ed.; Longmans, Green and Co LTD: London, UK. (1967).

Obidiegwu, J. E. & Akpabio, E. M. The geography of Yam cultivation in Southern nigeria: exploring its social meanings and cultural functions. J. Ethnic Foods. 4 (1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2017.02.004 (2017).

Darkwa, K., Olasanmi, B., Asiedu, R. & Asfaw, A. Review of empirical and emerging breeding methods and tools for Yam (Dioscorea spp.) improvement: status and prospects. Plant. Breed. 139 (3), 474–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbr.12783 (2020).

Adewumi, A. S. et al. Farmers’ perceptions on varietal diversity, trait preferences and diversity management of bush yam (Dioscorea praehensilis Benth.) in Ghana. Scientific African, 12, p.e00808. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00808

Condé, N. et al. The biocultural heritage and changing role of Indigenous Yams in the Republic of Guinea, West Africa. Plants People Planet. 7 (3), 719–733. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10498 (2024).

Sanginga, N. & Mbabu, A. October. Root and tuber crops (cassava, yam, potato and sweet potato). In proceedings of the an action plan for African Agricultural Transformation Conference, Dakar, Senegal 21–23 (2015).

Ampofo, D., Agbenorhevi, J. K., Firempong, C. K. & Adu-Kwarteng, E. Glycemic index of different varieties of Yam as influenced by boiling, frying and roasting. Food Sci. Nutr. 9 (2), 1106–1111. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.2087 (2021).

Lebot, V., Lawac, F. & Legendre, L. The greater Yam (Dioscorea Alata L.): A review of its phytochemical content and potential for processed products and biofortification. J. Food Compos. Anal. 115, 104987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2022.104987 (2023).

Obidiegwu, J. E., Lyons, J. B. & Chilaka, C. A. The Dioscorea genus (Yam)—An appraisal of nutritional and therapeutic potentials. Foods 9 (9), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091304 (2020).

Aiyedun, P. O. et al. Phytoecdysteroids from Dioscorea dumetorum (Kunth) Pax. And their antioxidant And antidiabetic activities. Fitoterapia 177, 106103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2024.106103 (2024).

Boudjada, A. & Rhouati, S. Etude phytochimique de deux espèces Crataegus azarolus L. (Rosaceae) et Dioscorea communis L.(Dioscoreaceae). Doctoral Dissertation, Université Frères Mentouri-Constantine 1, Algeria. (2018). http://archives.umc.edu.dz/handle/123456789/8146

Kundu, B. B. et al. Dioscorea bulbifera L.(Dioscoreaceae): A review of its ethnobotany, Pharmacology and conservation needs. South. Afr. J. Bot. 140, 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2020.07.028 (2021).

Sharma, S., Kaul, S. & Dhar, M. K. A systematic review on ethnobotany, phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Dioscorea bulbifera L.(Dioscoreaceae). South. Afr. J. Bot. 170, 367–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2024.05.014 (2024).

Suvathika, G. et al. Evaluation and identification of nutritional factors, cytotoxic condition, and Protodioscin in Dioscorea Alata tuber. South. Afr. J. Bot. 178, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2025.01.010 (2025).

Counsell, S. Forest governance in the Democratic Republic of Congo. An NGO perspective. Recommendations for a Voluntary Partnership Agreement with the EU. Moreton in Marsh, FERN. (2006).

Burkill, I. H. Notes on the genus Dioscorea in the Belgian congo. Bull. Du Jardin Botanique De l’Etat Bruxelles/Bulletin Van Den Rijksplantentuin Brussel. 15 (4), 345–392 (1939).

Bukatuka, F. et al. Bioactivity and nutritional values of some Dioscorea species traditionally used as medicinal foods in Bandundu, DR congo. Eur. J. Med. Plants. 14 (1), 1–11 (2016). http://science.oadigitallibraries.com/id/eprint/871/

Adejumobi, I. I. et al. Diversity, trait preferences, management and utilization of Yams landraces (Dioscorea species): an orphan crop in DR congo. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 2252. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06265-w (2022).

Mondo, J. M. et al. Farming practices, varietal preferences, and land suitability analyses for Yam production in Eastern DR congo: implications for breeding initiatives and food sovereignty. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 8, 1324646. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1324646 (2024).

Mondo, J. M. Southern Africa Development Community Indigenous Food Development Programme–Scoping Study on Indigenous Foods in DR Congo. Technical Report, WFP & FANRPAN. 56p. (2024).

Mondo, J. M. et al. Utilization of non-timber forest products as alternative sources of food and income in the Highland regions of the Kahuzi-Biega National Park, Eastern Democratic Republic of congo. Trees Forests People. 16, 100547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2024.100547 (2024).

Mondo, J. M. et al. Crop calendar optimization for climate change adaptation in yam farming in South-Kivu, eastern DR Congo. PloS One, 19(9), p.e0309775. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309775

Mondo, J. M. et al. Neglected and underutilized crop species in Kabare and Walungu territories, Eastern DR congo: Identification, uses and socio-economic importance. J. Agric. Food Res. 6, 100234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100234 (2021).

Mugumaarhahama, Y. et al. Socio-economic drivers of improved sweet potato varieties adoption among smallholder farmers in South-Kivu Province, DR Congo. Scientific African, 12, e00818. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00818

Dery, B. B. Indigenous Knowledge of Medicinal Trees and Setting Priorities for their Domestication in Shinyanga Region, Tanzania (World Agroforestry Centre, 1999).

Etikan, I., Alkassim, R. & Abubakar, S. Comparision of snowball sampling and sequential sampling technique. Biometrics Biostatistics Int. J. 3 (1), 55. https://doi.org/10.15406/bbij.2015.03.00055 (2016).

Pires, A. Échantillonnage et recherche qualitative: essai théorique et méthodologique. In La recherche qualitative. Enjeux épistémologiques et méthodologiques, Gaëtan Morin, Montréal, Canada, 169, 113. (1997). Available at: http://classiques.uqac.ca/

AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. 17th Edition, Association of the Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) International, Gaithersburg. (2003).

AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 14th Edition, AOAC, Arlington. (1984).

Osborne, D. R. & Voogt, P. I. The Analysis of Nutrients in Foods (Academic, 1978).

Barba, A. O., Hurtado, M. C., Mata, M. S., Ruiz, V. F. & De Tejada, M. L. S. Application of a UV–vis detection-HPLC method for a rapid determination of lycopene and β-carotene in vegetables. Food Chem. 95 (2), 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.028 (2006).

Burns, R. E. Method for Estimation of tannin in grain sorghum 1. Agron. J. 63 (3), 511–512. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1971.00021962006300030050x (1971).

Price, M. L., Van Scoyoc, S. & Butler, L. G. A critical evaluation of the Vanillin reaction as an assay for tannin in sorghum grain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 26 (5), 1214–1218. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf60219a031 (1978).

Harborne, J. B. & Williams, C. A. A chemotaxonomic survey of flavonoids and simple phenols in leaves of the Ericaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 66 (1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.1973.tb02159.x (1973).

Jagadish, L. K., Krishnan, V. V., Shenbhagaraman, R. & Kaviyarasan, V. Comparitive study on the antioxidant, anticancer and antimicrobial property of agaricus bisporus (JE Lange) Imbach before and after boiling. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 8 (4), 654–661 (2009).

Waterman, P. G. & Mole, S. Analysis of Phenolic Plant Metabolites (Blackwell Scientific Publications. Methods in Ecology, 1994).

Molyneux, P. The use of the stable free radical diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) for estimating antioxidant activity. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 26 (2), 211–219 (2004).

Hammer, Ø. & Harper, D. A. Past: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica, 4(1), p.1. (2001). https://doc.rero.ch/record/15326/files/PAL_E2660.pdf

R Core Team. R Core team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. (2020). Available at: https://www.r-project.org/

Lebot, V., Abraham, K. & Melteras, M. The lesser Yam Dioscorea esculenta (Lour.) burkill: a neglected crop with high functional food potential. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 72 (5), 5071–5091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-024-02296-6 (2025).

Aiyedun, P. O. et al. Antidiabetic and antioxidant profiling of 67 African trifoliate Yam accessions by planar on-surface assays versus in vitro assays. Fitoterapia 180, 106299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2024.106299 (2025).

Irakiza, P. N. et al. Fortification with mushroom flour (Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm) and substitution of wheat flour by cassava flour in bread-making: nutritional and technical implications in Eastern DR congo. Agric. Food Secur. 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00301-0 (2021).

Argaw, S. G., Beyene, T. M., Woldemariam, H. W. & Esho, T. B. Physico-chemical and functional characteristics of flour of Southwestern Ethiopia aerial and tuber Yam (Dioscorea) species processed under different drying techniques. J. Food Compos. Anal. 119, 105269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2023.105269 (2023).

Polycarp, D., Afoakwa, E. O., Budu, A. S. & Otoo, E. Characterization of chemical composition and anti-nutritional factors in seven species within the Ghanaian Yam (Dioscorea) germplasm. Int. Food Res. J. 19 (3), 985–992 (2012).

Padhan, B. & Panda, D. Potential of neglected and underutilized Yams (Dioscorea spp.) for improving nutritional security and health benefits. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 496. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00496 (2020).

Mondo, J. M. et al. Yam urban market characteristics and consumer preferences in Bukavu City, Eastern DR congo. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 9, 1553876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1553876 (2025).

Acknowledgements

“Amisi Kakozi, Henri Matiti, Jacques Kihye, Paterne Mitima, and Ghislain Kyambikwa are acknowledged for their active participation in data collection. Authors are also thankful to local communities that willingly provided part of the information presented in this manuscript.”

Funding

The funding support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) through RTB Breeding project of the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) (INV-003446) is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to this original research. JMM and AA designed the study, conducted data analyses and drafted the original manuscript, AZB and J-CMM conducted taxonomic and ethno-botanical surveys, JI, ERM, D-GB conducted laboratory assays for physicochemical analyses, GBC, PAA and PA participated in write-up and revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the UEA Interdisciplinary Centre of Ethical Research (CIRE), Ref: CNES 039/DPSK/322PP/2023. We obtained verbal informed consent from all resource-persons and community members before interviews after ensuring the confidentiality in use of data collected and explaining the study objectives, as approved and directed by the above Institutional Review Board. Additionally, consent was secured from the informants for the publication of the individual data gathered from them. Plant materials were collected under the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing and were only used for research purposes.

Consent for publication

“Not applicable”. There is no third party data. It is our original research data, all concerned individual authors have agreed to the publication of the outcome of this study as stated above under ethical consideration and authors’ contribution.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mondo, J.M., Balezi, A.Z., Ishara, J. et al. Nutritional and health benefits of wild and cultivated yam (Dioscorea spp.) species consumed in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Sci Rep 15, 42131 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26046-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26046-5