Abstract

A series of novel methyl-1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole derivatives were synthesized, characterized through 1H and 13C NMR and mass spectroscopic techniques and evaluated for their in silico and in vitro antiproliferative activity against leukemia cancer cells sensitive (K562) or resistant to imatinib (K562-IM). Among the studied compounds, only compound 5, with a methyl alcohol at the 4-position of pyrazole ring, and compound 6, with a methyl carboxamide at the 4-position of pyrazole ring, induced a cytotoxic response in both the CML cell lines. Despite its higher cytotoxicity in both cell line, compound 6 was also highly cytotoxic in primary normal human fibroblasts. In contrary, the high cytotoxicity of compound 5 towards both IM sensitive and resistant cell lines (K562 and K562-IM, respectively) and its lower or no effect in primary normal cells (IC 50 higher than 50 µM), indicates that this compound is suitable for further biological studies. Further, the docking score, hydrogen bond interactions, RMSD, and binding free energy also identified compound 5 as the most balanced and promising candidate by demonstrating a strong and stable binding profile with low RMSD, adequate hydrogen bonding, and favorable binding free energy. On the other hand, BOILED-Egg analysis results highlight that the compounds possess good absorption characteristics and, except for compound 5, demonstrate limited risk of efflux-mediated resistance. Indeed, when compound 5 was combined with IM in K562-IM resistant cells, a higher decrease of cell viability was observed when compared to IM alone, suggesting one more time that this pyrimidine derivative is suitable for CML therapeutics alone or in combination with IM (in resistant patients) or be used as basis for the design of new anti-cancer agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a major health issue worldwide. It affects a significant portion of the population, and even with more awareness and treatment options, the numbers keep rising1. According to the WHO, cancer is one of the top causes of death globally2. In 2020, there were 19.3 million new cancer cases and about 10.0 million cancer deaths recorded. This number is expected to rise by 47% by 2040, reaching 28.4 million cases3. Sadly, these figures are likely to keep increasing due to a lack of effective and targeted cancer therapies. One rare type of bone marrow cancer is chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)4. It’s also called chronic granulocytic leukaemia. While it mostly affects older adults, people of other ages can also get it, although it’s rare in children. Most CML patients have a chromosomal change called the Philadelphia chromosome. This usually happens due to a translocation that fuses the Abelson murine leukaemia (ABL1) gene on chromosome 9 with the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene on chromosome 22. This fusion creates an oncoprotein known as BCR-ABL1, which leads to constant tyrosine kinase activity. This causes the cells to differentiate improperly, replicate without control, and resist apoptosis5.

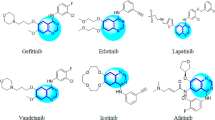

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) are specifically made to block the activity of this fusion oncoprotein and are the standard treatment for CML5,6. Although there are several FDA-approved pharmaceuticals featuring a pyrazole ring encompass Avapritinib, Asciminib, Crizotinib, Encorafenib, Erdafitinib, Pralsetinib, Pirtobrutinib, and Ruxolitinib, predominantly serving as protein kinase inhibitors for diverse oncological applications, Imatinib (IM) was the first TKI used in CML therapy. It binds to the ATP pocket in the kinase domain of the BCR-ABL1 protein and has over a 95% response rate. However, some CML patients develop resistance to IM, prompting the creation of second and third generation TKIs. Despite these advancements, the variety among CML patients and their resistance to multiple TKIs raise significant challenges, indicating a need for new therapies. IM (Fig. 1), a pyrimidine derivative, has spurred significant interest for the development of novel pyrimidines. Among the large number of heterocyclic compounds evaluated for anti-cancer activity against various types of cancer are the derivatives of pyrimidine which are used as privileged scaffolds in the discovery of anti-cancer drugs7. Pyrimidines are six-membered heterocycles with two nitrogen atoms in the position 1 and 3. They represent one of the most attractive pharmacophores for drug discovery with a wide range of pharmacological properties8, including antibacterial9, antiviral10, and anticancer agents11,12. Various derivatives of pyrimidine and pyrimidine-fused heterocyclic compounds with anticancer activity through multiple different mechanisms and targets have been reported to date13,14. Various derivatives of pyrimidine and pyrimidine-fused heterocyclic compounds with anticancer activity through multiple different mechanisms and targets have been reported to date15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

In the present work, we have synthesized and characterized novel pyrimidine-based scaffolds and their antiproliferative activities evaluated in two CML cell lines, one sensitive to IM (K562) and the other resistant to IM (K562-IM) and in normal primary human fibroblasts. Moreover, we have also analysed the effect of combining IM with the most cytotoxic compounds in the resistant cancer cell line, K562-IM. The molecular docking and dynamics along with binding free energy were carried out in complementing the experimental results.

Experimental

Materials and methods

All the chemicals and reagents were obtained from the commercial sources and used as received. The NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE NEO 400 MHz (Germany) and Varian Mercury 300 MHz spectrometer (USA) spectrometer. The ESI spectra were recorded on Shimadzu LCMS-SQ-2020-N series (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Japan) with ESI source and ionization.

Chemical synthesis

Synthesis of methyl-1-(2-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate (2)

To a solution of 2,4-dichloropyrimidine (50 mg, 0.21 mmol, 1 Eq) in DMF (2 mL) under argon atmosphere, methyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate (30 mg, 0.25 mmol, 1.2 Eq) and K2CO3 (58 mg, 0.42 mmol, 2 Eq) was added. The reaction mixture was refluxed at 80 °C for 4 h. The completion of reaction was monitored by TLC and the spots were visualized under UV light. The reaction mixture was quenched with ice cold water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layer was washed with water and brine solution, dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate, and concentrated to obtain the crude product. This was further purified through medium-pressured liquid chromatography (MPLC) to get the title compound, methyl 1-(2-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate as off white solid. Yield—15 mg; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3)—δ 9.06 (d, J = 0.6 Hz, 1H), 8.70 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H); LCMS m/z = 239 (M + H).

Synthesis of methyl 1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate (3)

To a solution of methyl-1-(2-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate (500 mg, 1 Eq) in DMF (10 mL) under argon atmosphere, methyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate (550 mg, 1.2 Eq) and K2CO3 (700 mg, 2 Eq) was added. The reaction mixture was heated at 80 °C for 4 h. The completion of reaction was monitored by TLC and the spots were visualized under UV light. The reaction mixture was quenched with ice cold water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layer was washed with water and brine solution, dried over sodium sulphate, and concentrated to get the crude, purified through MPLC to get the title compound methyl-1-(2-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate as off white solid. Yield—400 mg; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.99 (s, 1H), 8.51 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (br s, 2H), 6.77 (s, 1H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 6H); LCMS m/z = 324 (M + H).

Synthesis of 1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid (4)

To a solution of methyl-1-(2-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate (200 mg, 1 Eq) in THF: H2O (3:1 v/v) under argon atmosphere, lithium hydroxide (LAH) was added and stirred the reaction mixture at 25 °C for 24 h (the completion of reaction was monitored by TLC). The white precipitate was observed which was then filtered and dried to get the title compound 1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl) amino) pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid. Yield—150 mg; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.79 (s, 1H), 8.89 (s, 1H), 8.63 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 8.23–8.22 (m, 1H), 7.39 (s, 2H), 7.27 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H),6.68 (s,1H), 2.28 (s, 6H); LCMS m/z = 310 (M + H).

Synthesis of (1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl) methanol (5)

A solution of 1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid (50 mg, 1 Eq) in THF (2 mL) under argon atmosphere cooled to 0 °C, LAH (0.5 mL) was added dropwise and stirred the reaction mixture at room temperature for 1 h. The completion of reaction was monitored by TLC. The reaction mass was quenched with saturated solution of sodium sulphate and extracted with ethyl acetate, washed with brine solution, and dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate and concentrated to get the crude. Which was then purified by MPLC to get the title compound (1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methanol. Yield—30 mg; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.48–8.43 (m, 2H,), 7.79 (s, 1H), 7.29–7.22 (m, 4H), 7.12–7.09 (bs, 1H), 6.76 (bs, 1H), 4.68 (s, 2H), 2.34 (s, 6H); LCMS m/z = 295 (M + H).

Synthesis of 1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-N-methyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxamide (6)

To a solution of methyl 1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate (50 mg, 1 Eq) in THF (2 mL), 30% aqueous solution of methyl amine was added to the reaction mass (in seal tube) and heated to 70 °C for 4 h. The completion of reaction was monitored by TLC. The reaction was quenched with ice cold water, the solid obtained was filtered and dried under vacuum to get the title compound as white solid 6. Yield—30 mg; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD-d4) δ 8.99 (s, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.25 (m, 3H), 6.72 (s, 1H), 2.90 (s, 3H), 2.33 (s, 6H); LCMS m/z = 323 (M + H).

Synthesis of N-cyclohexyl-1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxamide (7)

To a solution of 1-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid (20 mg, 1 Eq) in DMF (2 mL) under argon atmosphere, the methyl amine (7.68 mg, 0.077 mmol,1.2 Eq, mukaiyama reagent (25 mg, 0.096 mmol, 1.5 Eq) and DIPEA (16.51 mg, 0.1 mmol, 2 Eq) was added and stirred the reaction mixture at room temperature for 12 h. The completion of reaction was monitored by TLC. The reaction was quenched with ice cold water and extracted with ethyl acetate, washed with brine solution, dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate and concentrated to get the crude compound, which was then purified through MPLC to get the title compound as white solid 7. Yield—15 mg; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.74 (s, 1H), 8.99 (s, 1H), 8.59–8.55 (m, 1H), 8.25–8.22 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.36 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.21 (m, 1H), 6.67–6.63 (m, 1H), 3.74–3.64 (m, 1H), 2.29–2.24 (m, 6H), 1.84–1.68 (m, 5H), 1.63–1.53 (m, 1H), 1.33–1.19 (m, 4H); LCMS m/z = 391 (M + H).

Molecular docking studies

Protein preparation

“ABL1 is a major therapeutic cancer target, and several inhibitors such as imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib have been developed to block its kinase activity. The crystal structure of ABL1 bound to imatinib (PDB ID: 2G2I) is particularly important in research, as it provides a high-resolution model of the active site in a drug-bound conformation, making it a widely used structure for molecular docking and rational ligand–protein interactions and provides a biologically relevant, ligand-bound structure of ABL1 that serves as a reliable model for docking studies. ABL1 structure (PDB ID: 2G2I), were downloaded from the RCSB PDB site [https://www.rcsb.org/] and prepared using the protein preparation workflow of Schrödinger Release 2024-322. The structures were pre-processed via assigning bond orders, adding hydrogens, and filling missing side chains using Prime. Protonation states for the ligands were generated at pH 7.4 ± 2.0. The protein’s hydrogen bond network was optimized using the H-bond assignment option. Finally, restrained minimization was performed to this structure, which allowed hydrogen atoms to be freely minimized, while allowing for sufficient heavy-atom movement to relax strained bonds, angles, and clashes. The minimized structure was used for docking analysis.

Molecular docking using Schrodinger

Docking grid was generated using receptor grid generation module of Schrodinger. The grid was defined using the co-crystallized ligand ADP. The potential of nonpolar atoms of the receptor was softened using the Van der Waals radius scaling with scaling factor 1.0 and partial charge cut-off 0.25. The Ligprep module of Schrödinger Release 2024–3 was used to convert 2D ligand structures to 3D structures. The target molecules were processed to assign the suitable protonation states at physiological pH 7.4 ± 0.0 using Epik. The prepared compounds were subjected to Ligprep. The Glide module of Schrödinger Release 2024-3 was used for docking. The prepared compounds were docked in ABL1 structures using Glide rigid protocol. The potential of nonpolar atoms of the ligand was softened using the Van der Waals radius scaling with scaling factor 0.80 and partial charge cut-off 0.15.

Molecular docking using Autodock

The ligand which were in SDF format was converted into PDB format using obabel tool. Molecular docking studies were performed using AutoDock 4.023 to predict the binding orientation and affinity of the molecules. The protein structure was prepared by removing water molecules, adding polar hydrogen atoms, and assigning Gasteiger charges. The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA), with default parameters for population size, mutation rate, crossover rate, and number of evaluations were used and the docking grid was generated using AutoGrid and finally autodock was performed.

Molecular dynamics

GROMACS 2024.424 was utilized for the molecular dynamic’s simulation. Energy minimization was performed using GROMACS 2024.4 with 50,000 steps (nsteps = 50,000), employing the steepest descent algorithm (steep) within a dodecahedral simulation box (distance = 2.0 nm) with extended simple point charge (SPC/E) water molecules25. The Amber ff99SB-ILDN force field26 was used to model the protein complex, while the target molecule topologies were generated using the Antechamber module within the AMBER22 suite27,28. Energy minimization of the system was carried out using the steepest descent algorithm for 50,000 steps to relieve any steric clashes. This was followed by two equilibration steps: a 1000 ps simulation under the NVT ensemble to stabilize the temperature at 300 K, and a 1000 ps NPT simulation to equilibrate the pressure at 1 atm. Subsequently, a production MD simulation was run for 100 ns to assess the dynamic behaviour and structural stability of the complex over time.

Binding free energy calculations

To further assess the binding stability of the complex, binding free energy was computed using the GMXPBSA module with MMPBSA.py29. Key output files from the simulation such as the .tpr file, index file, trajectory, and topology were used as inputs to generate the corresponding AMBER-compatible topology files.

In silico drug-likeness analysis

Durggability was predicted using BOILED-EGG model. The SwissADME web tool was used to predict the BOILED-EGG (Brain or Intestinal Estimated permeation method). The method is based on two key physicochemical descriptors: lipophilicity (WLOGP) and polarity (topological polar surface area, TPSA)30,31. By plotting WLOGP against TPSA, molecules are positioned within a graphical representation resembling a boiled egg. The white region represents compounds predicted to have high probability of human intestinal absorption, whereas the yellow yolk identifies molecules likely to cross the BBB.

Biological methods

Cell cultures and cell cultures maintenance

The K562 cell line (CCL-243), characterized by the BCR-ABL1 e14a2 fusion transcript, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The imatinib-resistant K562 cell line (K562-IM) was obtained by incubating the K562 imatinib sensitive cell line with increasing concentrations of imatinib32. The characterization of the cell line, including confirmation of BCR-ABL1 mutation was previously described by us32. Human Primary dermal fibroblasts (PCS-201-010, ATCC) were also used as normal control cells. All cell lines were maintained at 37 °C, 5% (v/v) CO2 and 99% (v/v) relative humidity in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, ThermoFisher Scientific) and a mixture of 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific). The medium of K562-IM was also supplemented with 1 µM of imatinib to assure selective pressure throughout passages.

Cell viability

Cell viability assays were performed using K562, K562-IM cancer cell lines, as well as normal human primary fibroblasts. The 96-well plates were prepared with increasing concentrations of compounds, ranging from 0.1 to 50 µM or the equivalent percentage of DMSO (as vector control). The equivalent amount of DMEM supplemented with FBS and antibiotics was added to the control plate. Cancer cells were added to the 96-well plates at a final density of 1 × 104 cells/well, while normal human primary fibroblasts were seeded at a final density of 0.75 × 105 cells/mL. After 72 h of incubation in the presence or absence of the compounds (37 °C, 5% (v/v) CO2, 99% (v/v) relative humidity), 20 μL of Cell Titer 96® Aqueous one solution cell proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added. Metabolically active cells contain mitochondrial dehydrogenases that can reduce 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) to formazan. The absorbance of formazan is then measured at 490 nm in a microplate reader (Tecan Infinite M200, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland), and is directly proportional to the number of viable cells33. Negative controls contained DMEM medium with the same % (v/v) of DMSO, and positive controls contained 0.4 µM Dox. The cell viability vs concentration graphics were analyzed using Prism 8 software (GraphPad) to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of each complex for the respective cell line. For control purposes, it was used in all experiments (in each 96-well plate) a reference drug with known effect on CML cells to validate the assay (i.e. the assay was only considered valid if the cell viability was according to values obtained in previously published papers32): (i) in K562 cell line, the assay was only considered as valid, if 1 µM Imatinib resulted in around 30% viability; (ii) in K562-IM cell line, the assay was only considered as valid, if 1 µM Imatinib resulted in around 75% viability; (iii) in normal dermal fibroblasts, the assay was only considered as valid, if 0.4 µM Imatinib resulted in around 100% viability.

Combinatorial therapeutics

For combinatorial therapeutics, 96-well plates were prepared as described above using only K562-IM cell line and different settings of combinations: (1) 13.1 µM Imatinib, and increasing concentrations of compound 5, (2) 13.1 µM Imatinib and increasing concentrations of compound 6, (3) 13.1 µM Imatinib and equivalent percentage of volume of DMSO. To calculate the cell viability with each concentration of the compound, the Abs values were corrected to the Abs of the respective concentration in the control plate and then normalized to the Abs of cells treated with respective volume percentage of DMSO.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from at least three independent biological experiments. A Student’s t-test was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Differences between two values were considered statistically significant when the p value was less than 0.05.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

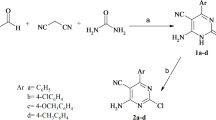

As depicted in Scheme 1, SNAr reaction was carried out between 2,4-dichloropyrimidine (1) and methyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate as well as ethyl 1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate to obtain 2, 2a and pyrimidine di-substituted with pyrazole methyl and ethyl ester, respectively (2b and 2c). Further, the second SNAr reaction was performed between the desired esters, 2 and 2a with 2,4-dimethylaniline to get intermediates 3 and 3a. These were then hydrolysed to obtain an active scaffold, 4. The acid amine coupling of 4 with coupling reagent, HATU and cyclohexyl amine to get desired target 7. The molecular structure of all the synthesized molecules were confirmed using 1H, 13C NMR and mass spectral techniques (Figures S1 to S11).

On the other hand, reduction of compound 3a was carried out using LAH to obtain target 5. Similarly, in the other case, compound 3a when treated with 30% aqueous solution of methyl amine in the heating condition, target 6 was obtained (Scheme 2). The structures of all the target compounds are depicted in Fig. 2.

Molecular docking results

To validate the docking protocol, the co-crystal ligand (ADP) of 2G2I PDB ID was docked in its binding site. The resulted pose showed RMSD of 2.5 Å with respect to the crystal pose due to the flexibility in the phosphate region. The docked pose of ADP retained hinge interactions with Glu316, Met318 along with the H-bond interactions with Asn322 and Gly250. Docking was performed to determine the plausible binding modes for compounds using ABL1 crystal structure bound to ADP (PDB ID: 2G2I). It is interesting to note that among all the compounds, compound 7 exhibited the most favorable docking score of − 6.67 kcal/mol, indicating a strong binding affinity. This was followed by compound 3 (− 5.63 kcal/mol), 6 (− 5.57 kcal/mol), 3a (− 5.55 kcal/mol), and 5 (− 5.51 kcal/mol), all of which demonstrated good docking scores below − 5.5 kcal/mol, reflecting their potential for stable interactions. In contrast, compound 2 through 2c and compound 4 showed relatively weaker binding affinities, with docking scores ranging from − 4.63 to − 5.07 kcal/mol and were therefore not considered for MD simulations. The docked pose of compound 6 showed H-bond interactions with Met318 (hinge) and Lys271, whereas compound 5 showed H-bond interaction with Glu286. Docking score for compound 6 and compound 5 were − 8.5 kcal/mol and − 7.8 kcal/mol, respectively. The binding poses for compounds 5 and 6 is shown in below Fig. 3.

Molecular dynamics analysis

The RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) plot (Fig. 4) provides insight into the structural stability of five different molecular dynamics (MD) simulations labeled as 3, 3a, 5, 6, and 7 over a 100-ns time frame. Compound 5, represented by the green line, exhibits the most stable behavior with RMSD values stabilizing between 0.25 and 0.35 nm and showing minimal fluctuations. This suggests that the structure remains highly stable throughout the simulation. Compound 3, shown in black, also demonstrates good stability, with RMSD values ranging from 0.25 to 0.35 nm and only moderate fluctuations, indicating a relatively stable conformation.

In contrast, compound 3a (red) shows higher RMSD values, ranging from approximately 0.45 to 0.65 nm, with noticeable fluctuations, suggesting that it is more flexible and undergoes significant conformational changes compared to its counterpart, compound 3. Compound 7, represented by the brown line, maintains RMSD values between 0.4 and 0.5 nm with moderate fluctuation, indicating a fair degree of stability but not as much as compound 3 or 5. Lastly, compound 6, depicted in blue, displays the highest RMSD values, ranging from 0.55 to 0.70 nm, along with substantial fluctuations throughout the simulation. Overall, compound 5 appears to be the most structurally stable. On the other hand, the average RMSD (Table 1) values obtained from the MD simulations provided insight into the structural stability of the complexes. Compound 5 and 3 showed the lowest average RMSD values, 0.284 nm and 0.288 nm respectively, indicating minimal conformational deviations and high structural stability. Compound 7 showed a slightly higher RMSD of 0.378 nm, suggesting reasonable stability. In contrast, compound 3a and 6 exhibited the highest RMSD values (0.558 nm and 0.560 nm), implying greater flexibility or reduced stability over the course of the simulation.

Furthermore, the hydrogen bond analysis (Fig. 5 and Table 1) revealed that Compound-Complexes 3a and 6 formed two strong hydrogen bonds each, which could enhance binding specificity and complex stability. Compound-Complexes 3, 5, and 7 formed one hydrogen bond each, which also supports stable ligand-receptor interactions, albeit slightly weaker than those with two bonds. Hydrogen bonding is a key contributor to the overall binding affinity and can influence the dynamic behaviour of the complex during simulation.

Binding free energy analysis

Binding free energy calculations (Table 1) post-MD simulation reinforced these observations. Compound 7 displayed the most favorable binding free energy of − 35.66 kcal/mol, followed by compound 3a (− 33.56 kcal/mol), suggesting strong binding even after dynamic fluctuations. Compound 5 maintained a good binding free energy of − 30.21 kcal/mol, and compound 3 was close behind with − 29.65 kcal/mol. Complex 6, however, showed a relatively lower binding free energy of − 23.41 kcal/mol, in line with its higher RMSD and lower stability. Finally, taking all parameters that is docking score, hydrogen bond interactions, RMSD, and binding free energy into consideration, compound 5 emerged as the most balanced and promising candidate. It demonstrated a strong and stable binding profile with low RMSD, adequate hydrogen bonding, and favorable binding free energy.

BOILED-Egg model

The BOILED-egg analysis of the tested compounds shows that all the molecules are positioned within the white region, which indicates a high probability of gastrointestinal absorption. This suggests that the compounds are suitable for oral administration and have favourable physicochemical properties for passive uptake through the intestinal membrane. None of the compounds fall within the yellow region, meaning they are not predicted to cross the blood–brain barrier (Fig. 6). For leukaemia therapy, this is generally advantageous because central nervous system penetration is not required unless specifically targeting CNS leukaemia. Among the tested compounds, compound 5 is identified as a P-glycoprotein substrate (PGP+), implying that it may be actively effluxed out of cells, potentially reducing its intracellular concentration and therapeutic effectiveness. In contrast, the other compounds (3, 3a, 6, and 7) are not predicted to be P-glycoprotein substrates (PGP-), which is favourable as they are less likely to encounter efflux-related resistance mechanisms. The TPSA values of all molecules fall between 70 and 90 Å2, a range considered optimal for balancing polarity and permeability, while their WLOGP values of approximately 2 to 4 indicate an ideal lipophilicity for oral absorption. Taken together, these results highlight that the compounds possess good absorption characteristics and, except for compound 5, demonstrate limited risk of efflux-mediated resistance. Therefore, they appear promising for systemic treatment of leukaemia, although additional studies on metabolic stability, solubility, and toxicity are necessary to confirm their suitability as drug candidates.

Biological assays

Cell viability

Two CML cell lines, K562, an imatinib sensitive CML model with the e14a2 BCR-ABL1 fusion transcript and K562-IM, an imatinib resistant line derived from K562 cells, and normal dermal fibroblasts were used to access the cytotoxicity of the compounds. After 72 h of incubation with increasing concentrations of the compounds, cells were incubated with [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] (MTS) and the percentage of viable cells relative to cells incubated with vector control (DMSO) measured. As observed in Table 2 and in Fig. 7, compound 5, with a methyl alcohol at the 4-position of the pyrazole ring, and compound 6, with a methyl carboxamide at the 4-position of pyrazole ring, present the highest cytotoxicity in both CML cell lines in comparison of the remaining compounds. Moreover, compound 6 present a higher cytotoxicity (lowest IC50 values) in both tested tumor cell lines. However, contrary to all compounds that showed no modifications in cell viability until 50 µM, compound 6 shows an IC50 of 17.4 ± 8.0 µM for normal human fibroblasts (Table 2), suggesting that this compound does not have a high selectivity towards CML cancer cells. Regarding compound 5, it is possible to observe a higher IC50 in K562-IM cells compared to the sensitive parental cell line (Table 2).

Cytotoxicity of compounds in CML imatinib sensitive (K562) and resistant (K562-IM) cell lines and normal dermal fibroblasts after 72 h incubation. Cytotoxicity of compounds 2, 2a, 2b, 2c, 3, 3a, 4 and 7 in (A) K562 cell line and (B) K562-IM cell line. Cytotoxicity of compounds 5 and 6 in (C) K562 cell line, (D) K562-IM cell line and (E) normal dermal fibroblasts. *p value < 0.05 relative to respective cells treated with DMSO.

Combination strategy with IM and compounds 5 and 6

Imatinib (IM) is the first and most used TKI in CML therapy. However, some patients develop IM resistance mechanisms decreasing its therapeutic effectiveness. Considering that, we have further explored the therapeutic potential of the combination of IM with compound 5 or 6 in K562-IM. K562-IM cells were simultaneously incubated with IM (at the concentration of 13.1 µM) and with increasing concentrations of compounds 5 or 6. After 72 h of incubation, the cell viability was evaluated as described above. Results showed that the combination therapy of IM and compounds led to a more than 10% loss of cell viability relative to cells only treated with IM (Fig. 8). Interestingly, when cells were exposed to higher concentrations of compound 5 (more than 25 µM), no further loss in cell viability was observed, suggesting a receptor saturation pattern (Fig. 8)34.

On the other side, the difference of cell viability was more accentuated as the concentration of compound 6 increased (Fig. 8), which is in line with its higher cytotoxicity previously observed (Fig. 7).

These results suggest an improvement of the therapeutic outcome in K562-IM when compounds and IM are administrated simultaneously, when compared to IM alone. However, when we compare these combinatorial results (Fig. 8) with the K562-IM cell viability results for compound 5 or 6 alone (Fig. 7), a lower therapeutic effect is observed for the combination strategy. Indeed, when K562-IM cell was incubated with IM + compound 5 a 50% maximum reduction of cell viability was observed (final value of 50% of cell viability at 75 µM) (Fig. 8), while a reduction of 80% of cell viability was observed when compound 5 was added alone (at the same concentration − 75 µM) (Fig. 7).

The cytotoxicity of compound 5 towards both IM sensitive and resistant cell lines (K562 and K562-IM, respectively); the IC50 higher than 50 µM in normal cells, and the improved cytotoxicity when combined with IM in K562-IM resistant cells compared to IM alone, suggest that this pyrimidine derivative is suitable for CML therapeutics or to be used as basis for the design of new anti-cancer agents.

Conclusion

To sum up, among the synthesized targets, compound 6 bearing methyl caboxamide at the 4-position of pyrazole ring showed the most cytotoxic activity against CML imatinib sensitive (K562) and imatinib resistant (K562-IM) cell lines with IC50 value of 16.8 and 14.0 µM, respectively. It is worth to mention that compound 4 bearing a carboxylic acid moiety and compound 7 bearing a cyclohexyl carboxamide moiety at the 4-position of the pyrazole ring showed no biological activity. However, it also presented an IC50 value of 17.4 µM in normal dermal Fibroblasts, suggesting low specificity towards tumor cells. Compound 5, having methyl alcohol at the 4-position of the pyrazole ring also presented toxicity in both CML cells, and no toxicity in Fibroblasts. Importantly, both compounds presented improved cytotoxicity when combined with IM compared to IM alone, but this combination strategy does not seem to be more effective compared to both compounds 5 and 6 alone. Compound 5 emerged as the most balanced and promising candidate. It demonstrated a strong and stable binding profile with low RMSD, adequate hydrogen bonding, and favorable binding free energy. These results demonstrate the potential of compound 5 for further biological studies or as a model for the design of new anti-cancer agents.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included within the article and supporting information.

Change history

05 February 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-39213-z

Abbreviations

- DMF:

-

N,N-Dimethylformamide

- HATU:

-

Hexafluorophosphate Azabenzotriazole Tetramethyl Uronium

- DIPEA:

-

N,N-Diisopropylethylamine

- LAH:

-

Lithium aluminium hydride

- THF:

-

Tetrahydrofuran

- MTS:

-

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium

- IM:

-

Imatinib

References

Colditz, G. A. & Emmons, K. M. The role of universal health coverage in reducing cancer deaths and disparities. Lancet 388, 638–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30376-2 (2016).

Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Weiderpass, E. & Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 127, 3029–3030. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33587 (2021).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer. J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Brody, T. Chapter 17—Hematological cancers. In Clinical Trials, 279–325. (Academic Press, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-391911-3.00017-7

Abdulmawjood, B., Costa, B., Roma-Rodrigues, C., Baptista, P. V. & Fernandes, A. R. Genetic biomarkers in chronic myeloid leukemia: What have we learned so far?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(22), 12516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222212516 (2021).

Kantarjian, H. et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 2542–2551. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa055104 (2006).

Kilic-Kurt, Z., Ozmen, N. & Bakar-Ates, F. Synthesis and anticancer activity of some pyrimidine derivatives with aryl urea moieties as apoptosis-inducing agents. Bioorg. Chem. 101, 104028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104028 (2020).

He, Z.-X. et al. Pyrimidine: A promising scaffold for optimization to develop the inhibitors of ABC transporters. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 200, 112458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112458 (2020).

Shaaban, O. G. et al. Synthesis and molecular docking study of some 3,4-dihydrothieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives as potential antimicrobial agents. Bioorg. Chem. 88, 102934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.102934 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. 6-Arylthio-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones potently inhibited HIV reverse transcriptase-associated RNase H with antiviral activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 156, 652–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.07.039 (2018).

Ma, L. Y. et al. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship of novel LSD1 inhibitors based on pyrimidine-thiourea hybrids as potent, orally active antitumor agents. J. Med. Chem. 58, 1705–1716. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00037 (2015).

Prachayasittikul, S. et al. Roles of pyridine and pyrimidine derivatives as privileged scaffolds in anticancer agents. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 17, 869–901. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389557516666160923125801 (2017).

Pike, K. G. et al. Optimization of potent and selective dual mTORC1 and mTORC2 inhibitors: The discovery of AZD8055 and AZD2014. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23, 1212–1216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.01.019 (2013).

Gao, Y., Dickerson, J. B., Guo, F., Zheng, J. & Zheng, Y. Rational design and characterization of a Rac GTPase-specific small molecule inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7618–7623. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0307512101 (2004).

Rangaswamy, S. et al. Design and synthesis of oxazole-linked pyrazole chalcone derivatives: In-vitro anticancer evaluation and In-silico molecular docking studies. Chem. Select 8, e202302395 (2023).

Ahsan, Md. J. et al. Synthesis, antiproliferative activity, and molecular docking studies of curcumin analogues bearing pyrazole ring. Med. Chem. Res. 24, 4166–4180 (2015).

Arun, B., Brahmaiah, M., Sreenivasulu, R., Sravani, D., Dodda, S., Kapavarapu, R. K. & Krishnaswamy, S. Rational design and synthesis of 1,2,3-triazole incorporated oxazolo[5,4-d] pyrimidine derivatives: In-vitro cytotoxicity and In-silico molecular docking simulations. Polycyclic Aromatic Compd. (2025).

Babu, V. R. et al. Design, synthesis, anticancer evaluation and molecular docking studies of different aryl derivatives of azaindole-pyrimidine-1,3,4-oxadiazoles. Synth. Commun. 55, 405–421 (2025).

Devi, E. R. et al. Design, synthesis, in-vitro and in-silico anticancer studies on amide derivatives of 1,3,4-oxadiazole-isoxazol-pyridine-benzimidazole. Chem. Pap. 79, 1385–1405 (2025).

Raghavender, G., Chandrasekhar, C. H., Kapavarapu, R. K. & Sreenivasulu, R. Synthesis of amide derivatives of pyrimidine-triazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-7-yl)thiazoles: in vitro anticancer evaluation and in silico molecular binding studies. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. (2024).

Bandaru, C. M. et al. Design, synthesis, anticancer evaluation and molecular docking studies of thiazole-pyrimidine linked amide derivatives. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 42, 5368–5384 (2022).

Zardecki, C., Dutta, S., Goodsell, D. S., Voigt, M. & Burley, S. K. RCSB protein data bank: A resource for chemical, biochemical, and structural explorations of large and small biomolecules. J. Chem. Educ. 93, 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00404 (2016).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30(16), 2785–2791. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21256 (2009).

Pronk, S. et al. Gromacs 45: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 29(7), 845–854. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055 (2013).

Wu, Y., Tepper, H. L. & Voth, G. A. Flexible simplepoint-charge water model with improved liquid-state properties. J. Chem. Phys. 124(2), 024503. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2136877 (2006).

Lindorff-Larsen, K. et al. Improved side-chaintorsion potentials for the amber ff99sb protein force field. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 78(8), 1950–1958. https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.22711 (2010).

Case, D. A. et al. The amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 26(16), 1668–1688. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20290 (2005).

Salomon-Ferrer, R., Gotz, A. W., Poole, D., Le Grand, S. & Walker, R. C. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with amber on gpus. 2. Explicit solvent particlemesh ewald. J Chem Theory Comput 9(9), 3878–3888. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct400314y (2013).

Miller, B. R. III. et al. MMPBSA. py: An efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8(9), 3314–3321. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct300418h (2012).

Daina, A. & Zoete, V. A BOILED-Egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small molecules. ChemMedChem 11(11), 1117–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.201600182 (2016).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42717 (2017).

Abdulmawjood, B., Roma-Rodrigues, C., Baptista, P. V. & Fernandes, A. R. Tackling imatinib resistance via Au-nanoconjugates using A Cml resistant cell line. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 41, 2300090. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppsc.202300090 (2024).

Das, K. et al. EPR and electrochemical interpretation of bispyrazolylacetate anchored Ni(II) and Mn(II) complexes: Cytotoxicity and anti-proliferative activity towards human cancer cell lines. New J. Chem. 42, 9126–9139. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8NJ01033A (2018).

Attie, A. D. & Raines, R. T. Analysis of receptor-ligand interactions. J. Chem. Educ. 72(2), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed072p119 (1995).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the Director, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Mysuru Campus for providing the infrastructure facilities. This work was financed by national funds from FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., in the scope of the project https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/04378/2020 and https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04378/2020 of the Research Unit on Applied Molecular Biosciences—UCIBIO and the project LA/P/0140/2020 of the Associate Laboratory Institute for Health and Bioeconomy—i4HB. The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-734), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for their support.

Funding

Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-734), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.K.V., P.M.S., S.P.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis; R.K.V., A.P.C., C.R.R., P.V.B., A.R.F., S.P.K.: Data curation, Investigations, Formal analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation. M.I., V.S., E.S., S.P.K.: Visualization, Project administration, validation. S.P.K.: Resources, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional Information

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Alexandra R. Fernandes and Shiva Prasad Kollur were omitted as corresponding authors. Correspondence and requests for materials should also be addressed to ma.fernandes@fct.unl.pt and shivachemist@gmail.com.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajasheker, K.V., Pallavi, M.S., Arun, P.C. et al. Chemical synthesis, bioinformatics and antiproliferative studies of novel pyrimidin-4-yl-1H-pyrazole derivatives in chronic myeloid cancer cells. Sci Rep 16, 2229 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26292-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26292-7