Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the expression levels of CD8+ and CD39+CD8+ T cells in both intratumoral (CK+) and stromal (CK−) regions, in conjunction with clinical parameters, to assess their potential impact on chemotherapy response and prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) patients. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) surgical specimens from 129 patients with EOC were used to construct tissue microarrays (TMAs) for assessing the expression of CD8+ and CD39+CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Cytokeratin (CK) immunolabeling was employed to distinguish epithelial tumor regions (CK+) from stromal regions (CK−) in EOC tissues. Independent prognostic factors were identified using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, and these variables were incorporated into nomogram models to predict overall survival (OS). Patients in the platinum-sensitive group exhibited significantly higher expression levels of stromal CD8+ cells and CD39+CD8+ T cells, which were strongly correlated with platinum sensitivity compared with the platinum-resistant group (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0004, respectively). Multivariate Cox regression analysis in the training cohort indicated that elevated stromal levels of CD39+ T cells and CD39+CD8+ T cells were independently associated with improved OS (HR = 2.587, p = 0.033; HR = 3.090, p = 0.008, respectively). Nomograms were developed to visually predict OS by integrating these biomarkers with relevant clinical indicators identified in the Cox regression analyses. Calibration curves demonstrated excellent concordance between predicted and observed survival outcomes. Elevated stromal levels of CD39+CD8+ T cells represent a promising prognostic biomarker for predicting platinum sensitivity and favorable prognosis in patients with advanced EOC. These findings may provide valuable insights into the tumor microenvironment and its role in modulating therapeutic responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) remains the most lethal gynecologic malignancy, with a mortality rate exceeding that of any other cancer in this category1. This is largely due to the absence of effective early detection strategies and the clinically silent nature of early-stage disease, resulting in most EOC cases being diagnosed at advanced stages2. Despite advances in diagnostics and therapy, the 5-year survival for stage III–IV EOC has remained below 40% over the past two decades1. This persistently low survival rate underscores the urgent need for a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying EOC progression and metastasis, which could facilitate the development of targeted interventions to improve patient outcomes.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) has increasingly been recognized as a key determinant influencing the progression of EOC and patient survival. Among the components of the TME, cytotoxic CD8⁺ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) serve as critical mediators of antitumor immunity. Numerous studies have demonstrated a strong association between the presence of CD8+ TILs and improved survival outcomes across a variety of malignancies, including ovarian cancer3,4,5. However, a major challenge in translating this knowledge into clinical practice lies in the substantial heterogeneity of TIL populations, both between and within tumors. This heterogeneity complicates the reliable identification of tumor-specific CD8+ lymphocytes. Notably, Evan et al.6 identified CD39 as a defining marker of tumor-specific CD8⁺ TILs, with higher frequencies associated with improved clinical outcomes in lung cancer. In contrast, bystander CD8+ TILs, which are not tumor-specific, lack expression of CD39. This finding suggests that CD39+CD8+ T cells constitute a more tumor-reactive subpopulation, highlighting them as a promising target for further investigation.

Standard treatment for advanced-stage EOC consists of cytoreductive surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy7. However, the prevalence of chemotherapy resistance often leads to disease recurrence and poor long-term outcomes, thereby contributing to the high mortality associated with EOC. This reality highlights an urgent need to identify reliable predictive and prognostic biomarkers for patients with advanced EOC.

Stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), including CD8⁺ subsets, have been investigated in ovarian and other solid tumors, with several reports linking higher stromal TIL densities to favorable outcomes8; however, the prognostic contribution of stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells remains incompletely characterized in EOC. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the expression of CD39+CD8+ T cells within epithelial ovarian tumor (CK+) and stromal (CK−) tissues. By correlating these expression patterns with clinical parameters, we sought to elucidate the role of this subpopulation in predicting chemotherapy response and determining prognosis in patients with EOC. Our findings aim to enhance the understanding of CD39+CD8+ T cells as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in the management of this malignancy.

Materials and methods

Patient information

Tissue specimens and clinical data were collected from 129 patients diagnosed with EOC who underwent surgical treatment from October 1, 2009, to November 30, 2015. Eligible patients were newly diagnosed and histologically confirmed as having EOC, and all received platinum-based chemotherapy following primary cytoreductive surgery. Patients were excluded if they had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery or if they had a history of other malignancies. All enrolled patients completed six to eight cycles of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy after primary surgery. After treatment, patients were monitored regularly for five years, with the last follow-up performed on July 31, 2021. The median follow-up duration among surviving patients was 70 months (range: 52–81 months).

The administered chemotherapy regimens consisted of paclitaxel (175 mg/m²) in combination with either carboplatin (area under the curve, 5) or cisplatin (75 mg/m²). Clinical outcomes were evaluated based on progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). PFS was defined as the time from the date of primary surgery to the first documented tumor recurrence. OS was defined as the time from surgery to death from any cause or to the date of last follow-up9. Progression-free interval (PFI) was defined as the time from completion of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy to radiographic or biochemical progression, or tumor recurrence10. For categorical analyses, the conventional 6-month cutoff was applied (PFI < 6 months = platinum-resistant; ≥6 months = platinum-sensitive). For exploratory Kaplan–Meier displays, we additionally categorized patients into three strata (< 6, 6–12, > 12 months), as indicated.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University (approval no. 2019MEC044). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Establishment of tissue microarrays (TMAs)

A total of 149 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) EOC samples were used to construct TMAs. However, due to the lack of available FFPE tissues in 16 cases and the loss to follow-up of 4 additional patients, laboratory analyses were ultimately performed on 129 patients. FFPE tissue blocks from all cases were independently reviewed by two pathologists to ensure diagnostic consistency. Representative areas of invasive carcinoma were identified and marked on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections. Guided by these reference sections, core tissue cylinders (0.6 mm in diameter) were extracted from the designated tumor regions using a tissue microarray instrument (Beecher Instruments, Silver Spring, MD, USA) and arrayed onto recipient paraffin blocks.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay

IHC was performed to assess the expression of CD8 and CD39 in TMA sections. FFPE TMA Sect. (4 μm) were deparaffinized in xylene (two changes, 10 min each) and rehydrated through graded ethanol solutions (100%, 95%, 80%, 70%; 2–3 min each) to distilled water. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was carried out in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) at 95–98 °C for 20 min, followed by bench cooling at room temperature for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min at room temperature. Sections were incubated with 5% normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 for 30 min at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-CD8 (ab217344, Abcam; 1:2000) and rabbit anti-CD39 (ab223842, Abcam; 1:1000). Immunoreactivity was visualized using a Dako Autostainer with the EnVision™ FLEX/HRP system and DAB chromogen, followed by hematoxylin counterstain, dehydration, clearing, and mounting. Quantitative analysis (cells/mm²) was performed with the Vectra platform.

Multiplexed Immunofluorescence assay

For multiplexed immunofluorescence (mIF), TMA slides were pretreated by heating at 63 °C for 1 h, followed by deparaffinization in xylene and rehydration through graded ethanol solutions (100%, 95%, 75%, and 50%). Antigen retrieval was performed in an EDTA buffer (pH 8.0). Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubating the slides in a blocking solution containing 0.3% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Tween-20 for 30 min.

The primary antibodies used included anti-CD8 (ab217344, Abcam; 1:2000 dilution), anti-CD39 (ab223842, Abcam; 1:1000), and anti-pancytokeratin (PA125, Baidao Medical Technology, China). After incubation with the primary antibodies, species-specific secondary antibodies (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) were applied, followed by staining with Opal™ fluorophore reagents (1:100, 6 min per cycle). Each staining cycle—comprising blocking, primary and secondary antibody incubation, and fluorophore application—was repeated five times. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Chromogenic IHC for CD8 and CD39 was performed as single-plex staining on adjacent serial FFPE sections, followed by DAB visualization and hematoxylin counterstaining. Positive cell densities (cells/mm²) were quantified digitally within annotated regions. Colocalization of CD8 and CD39 was evaluated exclusively using multiplex IF (see “Multiplex IF and Image Analysis”). Multiplex IF (DAPI/CK/CD8/CD39) was used to identify CD39⁺CD8⁺ double-positive cells within CK-segmented (CK⁺ and CK⁻) compartments.

High-resolution imaging of H&E-stained and immunofluorescence-stained sections was performed using the Vectra Polaris Automated Quantitative Pathology Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Multiplexed quantitative Immunofluorescence (QIF)

Quantitative assessment of fluorescent signal intensity was conducted using the automated quantitative analysis (AQUA) method, as previously described11. TMA cores (4-µm FFPE) were scanned on a Vectra Polaris imaging system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) using a 20× objective (NA 0.75; 0.5 μm/pixel). For each case, the entire core area was analyzed without manual field selection; therefore, cell counts represented whole-core measurements rather than sampled fields. Tissue segmentation was performed using cytokeratin (CK) to define CK⁺ epithelial and CK⁻ stromal compartments. Single-cell segmentation (based on DAPI nucleus expansion) and phenotype classification (CD8, CD39, CK) were performed in inForm software (Akoya Biosciences, Marlborough, MA, USA), using reviewer-approved thresholds applied uniformly across the batch. Output parameters included cell density (cells/mm²) for CD8⁺, CD39⁺, and CD39⁺CD8⁺ double-positive populations, as well as quantitative immunofluorescence (QIF) intensity values (arbitrary units). Batch effects were monitored using control cores and normalized on a per-slide basis as needed. The analyzed region areas (mm²) used as denominators were exported directly from inForm. QIF for each marker was calculated as the mean per-cell fluorescence intensity within phenotyped cells and aggregated as density (cells/mm²) and normalized intensity (arbitrary units) within CK-segmented compartments.

QIF scores for each fluorescence channel were further calculated using TissueFAXS software (TissueGnostics, Vienna, Austria). Scores were obtained by dividing the total pixel intensity of the target TIL marker within each compartment by the respective area. Only slides containing more than three cytokeratin-positive fields of view (FOVs) were included in the analysis. The results were independently reviewed and verified by two pathologists to ensure analytical reliability.

Random grouping and construction of the nomogram model

Random grouping of patients was performed using R software (version 4.2.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Patients were randomly assigned into training (70%) and validation (30%) cohorts. X-tile software (version 3.6.1, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA)12 was utilized to determine optimal cutoff points and stratify survival variables into low- and high-risk groups. To identify independent prognostic factors from the clinical data, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed. Variables with clinical or statistical significance identified in these analyses were subsequently incorporated into the development of nomogram models. The nomograms were developed using several R packages, including rms, Hmisc, lattice, survival, Formula, foreign, and ggplot2.

The predictive performance of the nomogram models was evaluated using multiple validation approaches. Calibration curves were generated to assess model calibration, whereas the concordance index (C-index) and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were calculated to evaluate discriminative ability. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed to evaluate the clinical net benefit and utility of the nomograms. All analyses were conducted separately in the training and validation cohorts to ensure the robustness, generalizability, and reliability of the prognostic models.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). To compare differences in baseline characteristics between the training and validation cohorts, either the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was applied, depending on variable distribution. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to visualize survival outcomes, and the log-rank test was used to compare survival differences between groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to identify prognostic factors and to inform the construction of nomogram models. Variables with a p value < 0.05 in the multivariate analysis were considered independent prognostic indicators for EOC. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline clinical characteristics of the 129 EOC patients. The median age of the cohort was 62 years (range, 33–89 years). According to FIGO staging, 119 patients (92.2%) were classified as stage III, and 10 patients (7.8%) as stage IV. With respect to histopathological subtype, 88 patients (68.2%) had high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), 33 patients (25.6%) had endometrioid carcinoma, and 8 patients (6.2%) had other histological types. No significant differences were observed between the training and validation cohorts for any variables, indicating that all variables listed in Table 1 were appropriate for subsequent analyses.

Platinum response

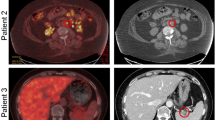

Based on the PFI, patients were classified into platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant groups. A total of 113 (87.6%) were classified as platinum-sensitive, whereas 16 patients (12.4%) were platinum-resistant. The association between CD39⁺, CD8⁺, and CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cell densities within CK-segmented regions and platinum response is shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1 summarizes immunofluorescence (IF)-derived densities. Panels a–c depict total-core values irrespective of CK compartment, whereas panels d–i present quantification restricted to CK⁺ (tumor epithelium) or CK⁻ (stroma) compartments following CK-based segmentation. No significant differences were observed between platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant groups for total CD39⁺ (P = 0.173), total CD8⁺ (P = 0.120), total CD39⁺CD8⁺ (P = 0.310), CD39⁺ in CK⁻ (P = 0.167), CD39⁺ in CK⁺ (P = 0.170), CD8⁺ in CK⁻ (P = 0.651), or CD39⁺CD8⁺ in CK⁺ (P = 0.176). In contrast, CD8⁺ T cell density in CK⁺ compartments was significantly higher in the platinum-sensitive group (P < 0.0001), and CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cell density in CK⁻ compartments was also significantly elevated in the sensitive group (P = 0.0004). Representative multiplex immunofluorescence images (Fig. 2a–b) illustrate abundant stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells in platinum-sensitive tumors compared to platinum-resistant tumors. Quantitative validation confirmed significantly higher CD39⁺CD8⁺ cell density in the CK⁻ region among platinum-sensitive patients (P = 0.0004). These findings were corroborated by quantitative IF, showing higher stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ densities in platinum-sensitive compared with resistant tumors (Supplementary Fig. S1). Moreover, stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ densities remained consistently higher in sensitive cases, whereas stromal CD39⁺ (all cells) exhibited a broad distribution with overlapping ranges (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Groupwise comparison of immune cell densities (cells/mm²) by platinum response. Bar plots show mean ± SD for total counts and for CK-stratified regions. Platinum-resistant (n = 16) vs. platinum-sensitive (n = 113); two-sided Mann–Whitney U tests; exact P-values shown above panels. Quantification from multiplex immunofluorescence (IF) with CK-based segmentation. Panels a–c show total-core densities regardless of CK compartment. Panels d–i show densities within CK-defined regions (CK⁻ = stroma; CK⁺ = tumor epithelium). Bars denote mean ± SD; P values by Mann–Whitney test. *** p < 0.001.

Representative multiplex IF images and quantitative validation. (a) High expression: representative images of CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells in the CK⁻ region in the platinum-sensitive group (yellow and green; Scale bar = 100 μm); (b) Low expression: representative images of CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells in the CK⁻ region in the platinum-resistant group (yellow and green; Scale bar = 100 μm). Group sizes: resistant n = 16, sensitive n = 113.

Optimal cut-off values and Cox regression analysis of the training group

Ninety-one patients were randomly assigned to the training cohort, while 38 patients were included in the validation cohort. Table 2 presents the optimal cut-off points for variables in the training cohort, as determined by X-tile software. For subsequent analyses, the optimal thresholds determined by X-tile were: CD8⁺ density ≤ 79 vs. > 79 cells/mm², CD39⁺ density in the CK⁻ (stromal) region ≤ 1.78 vs. > 1.78 (arbitrary units, QIF), and CD39⁺CD8⁺ density in the CK⁻ region ≤ 18 vs. > 18 cells/mm². These cut-offs were applied consistently in Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression analyses. Based on these thresholds, patients were classified into low and high expression groups for univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. Clinically and statistically significant variables were subsequently incorporated into the development of nomogram models. Cox regression analysis revealed that age, tumor residual size, and PFI were significantly associated with PFS (Table 2). For OS, platinum response, tumor residual size, PFI, stromal CD39⁺ (CK⁻), and stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ (CK⁻) were significant predictors (Fig. 4a; Table 2). Kaplan–Meier survival curves for OS are shown in Fig. 3. Platinum sensitivity was associated with longer OS (P < 0.0001, Fig. 3a). Endometrioid histology conferred improved OS compared with HGSOC (P = 0.012, Fig. 3b). Residual disease > 1 cm predicted worse OS (P = 0.0026 and P = 0.003, Fig. 3c–d). Stratification by PFI at 6 months also discriminated OS (P = 0.0015 and P < 0.0001, Fig. 3e–f). Using X-tile-derived thresholds, low versus high CD8⁺ (≤ 79 vs. > 79 cells/mm²) predicted OS (P = 0.044, Fig. 3g). Similarly, low versus high stromal CD39⁺ (≤ 1.78 vs. > 1.78, QIF) (P = 0.016, Fig. 3h) and stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ (≤ 18 vs. > 18 cells/mm²) (P = 0.031, Fig. 3i) were predictive of OS.

Overall survival (OS) by clinicopathologic and immune variables. Kaplan–Meier curves with log-rank P-values and numbers at risk below each plot: (a) platinum response (resistant vs. sensitive; n per group noted); (b) pathology; (c–d) residual disease size; (e–f) PFI categories; (g) total CD8⁺ count (cutoff, see Methods); (h) stromal CD39⁺ count; (i) stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells. Cutoffs were pre-specified as described in Methods. CD39, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1; CK, cytokeratin; OS, overall survival.

Hazard ratio of EOC in the training group and nomogram model for OS of EOC. A) Hazard ratio of EOC in the training group; B) Nomogram model for OS of EOC. CD39, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1; CI, confidence interval; CK, cytokeratin; EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

Moreover, higher stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cell densities in CK⁻ compartments were strongly associated with platinum sensitivity. Both platinum sensitivity and elevated stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ densities correlated with improved OS. Collectively, these findings suggest that high stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cell levels in EOC tumors are associated with both platinum sensitivity and improved OS. Finally, these variables were incorporated into the nomogram model for the training cohort (Table 2; Fig. 4a). Although no baseline difference in stromal CD39⁺ expression was observed between platinum-sensitive and resistant groups (Fig. 1), multivariate analysis demonstrated that higher stromal CD39⁺ densities were independently associated with improved OS. Notably, the absence of a baseline group difference does not preclude prognostic relevance. In multivariable Cox models adjusting for clinicopathologic factors, higher stromal CD39⁺ and CD39⁺CD8⁺ densities were associated with improved OS (Fig. 4a, Forest plot), indicating prognostic rather than solely group-discriminative relevance.

Nomogram model construction and validation

The predictive performance of the nomogram models was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), decision curve analysis (DCA), and calibration plots. Clinical variables identified via multivariate Cox regression were incorporated into the nomogram for the training cohort (Fig. 4b). Platinum response and tumor residual size, established prognostic factors for EOC, were included in the nomogram. Details of the point assignment and scale labels in the nomogram are presented in Table 3. In the multi-time ROC analysis, the 1-year (Fig. 5a), 3-year (Fig. 5b), and 5-year (Fig. 5c) AUCs of the nomogram exceeded those of other independent prognostic factors, suggesting that the nomogram provides a more accurate prognostic tool for EOC patients. Time-dependent ROC curves were used to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the nomogram in the training cohort. The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year AUCs were 0.949, 0.835, and 0.830, respectively (Fig. 6a), with a C-index of 0.756. Calibration curves demonstrated good agreement between predicted and observed survival probabilities (Fig. 6b). Decision curve analysis (DCA) demonstrated clinical benefit of the nomogram in predicting OS (Fig. 6c).

The AUCs at 1, 3, and 5 years of nomogram model and other independent prognostic factors of EOC. (a) The 1-year AUCs of nomogram model and other independent prognostic factors of EOC; (b) The 3-year AUCs of nomogram model and other independent prognostic factors of EOC; (c) The 5-year AUCs of nomogram model and other independent prognostic factors of EOC. AUC, area under the curve of receiver operating characteristics (ROC); CD39, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1; CK, cytokeratin; EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer.

The validations of nomogram model and risk stratification of EOC. (a, d) The AUCs at 1, 3, and 5 years of the training group and validation group; (b, e) The calibration curves at 1, 3, and 5 years of the training group and validation group; (c, f) The DCAs of the training group and validation group; (g) Survival curve analysis of risk stratification; (h) The AUCs at 1, 3, and 5 years of risk stratification in the training group. AUC, area under the curve of receiver operating characteristics (ROC); DCA, decision curve analysis; EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; OS, overall survival.

In the validation cohort, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year AUCs were 0.700, 0.793, and 0.821, respectively (Fig. 6d), with a C-index of 0.735. Calibration curves also demonstrated good agreement between predicted and observed outcomes (Fig. 6e). DCA curves again demonstrated that the nomogram provided clinical benefit for EOC patients (Fig. 6f). Using X-tile to determine optimal cut-off points for nomogram scores, Kaplan–Meier survival curves for OS showed a significant difference between low-risk (score ≤ 100) and high-risk (score > 100) groups (P < 0.0001, Fig. 6g).

In the validation group, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year AUCs were 0.700, 0.793, and 0.821, respectively (Fig. 6d), and the C-index was 0.735. The calibration curves also showed good agreement between the predicted outcomes and actual observations (Fig. 6e). The DVA curves again demonstrated that the nomogram model provided greater benefit for EOC patients (Fig. 6f).

Risk stratification in EOC patients

Using X-tile to determine optimal cut-off points for nomogram scores, Kaplan–Meier survival curves for OS showed a significant difference between low-risk (score ≤ 100) and high-risk (score > 100) groups (P < 0.0001, Fig. 6g). The AUCs at 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.838, 0.628, and 0.591, respectively (Fig. 6h), with a C-index of 0.759.

Discussion

TILs, comprising lymphocytes located within tumor cell nests and surrounding malignant cells, are pivotal contributors to antitumor immunity, and their presence within the TME has demonstrated substantial predictive and prognostic value13,14,15. Multiple studies have investigated stromal TILs in ovarian cancer and other malignancies, consistently associating higher stromal CD8⁺ T-cell densities with improved survival or enhanced treatment responses8,16,17. Our findings expand upon existing literature by focusing on the CD39⁺ subset of stromal CD8⁺ T cells, which are often enriched for tumor-reactive phenotypes, and demonstrate that increased stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T-cell density is associated with greater platinum sensitivity and improved OS in EOC.

Among these, CD8⁺ TILs have consistently been associated with favorable prognostic outcomes and improved clinical responses across a range of therapeutic modalities. This study examined the expression levels of CD8⁺ and CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells within intratumoral (CK⁺) and stromal (CK⁻) regions and evaluated their associations with clinical parameters to determine their impact on chemotherapy response and prognosis in EOC. A notable finding was the robust association between elevated stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T-cell expression and enhanced sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy, which was accompanied by improved clinical outcomes. These findings highlight the potential utility of stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells as predictive biomarkers of platinum therapy response and patient prognosis.

Stromal TILs, defined as lymphocytes localized within the tumor stroma without direct infiltration into tumor cell nests, have been a major focus of prognostic investigation, particularly in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) treated with anthracycline-based adjuvant chemotherapy13,18. Although not comprehensive, the existing evidence underscores several key observations. Systematic reviews have demonstrated that elevated CD8⁺ TIL densities are associated with improved OS and PFS across a variety of solid tumor types13,14,15.

In the context of EOC, increased infiltration of CD8⁺ TILs has been associated with improved survival4,19,20,21. A large-scale cohort study involving 3,196 patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) demonstrated that CD8⁺ TILs within tumor islets were significantly associated with prolonged OS, independent of residual disease after cytoreductive surgery, standard treatment modalities, or BRCA1 germline mutation status3.

Despite these findings, most studies examining spatial heterogeneity within tumors have primarily focused on intraepithelial CD8+ TILs. The role of stromal CD8+ TILs in tumor progression and immune-mediated disease control remains unclear, largely due to inconsistent functional evidence. For example, Yun et al.22 reported that elevated stromal CD8⁺ TIL densities were correlated with improved survival among EOC patients. Similarly, Weimin et al.23 identified a positive association between stromal CD8⁺ T cells, chemotherapy responsiveness, and patient survival. Our findings are consistent with these reports, demonstrating that increased stromal CD8⁺ T-cell expression serves as a significant determinant of platinum sensitivity and patient prognosis.

Within the tumor stroma, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) play a critical role in modulating platinum accumulation within tumor cell nuclei, thereby influencing chemoresistance. However, CD8+ T cells can counteract this effect by reprogramming fibroblast metabolism, thereby enhancing platinum sensitivity and influencing clinical prognosis23. Previous studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between stromal fibroblast density and patient survival, whereas stromal CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration is positively correlated with favorable clinical outcomes23.

Despite these observations, conflicting evidence has been reported. For instance, Tao et al.24 reported no significant association between PFS, OS, and stromal CD8+ TIL density in advanced EOC. Notably, Tao et al.’s analysis focused on metastatic (omental) rather than primary (ovarian) tumor sites, underscoring the need for further investigation to validate the prognostic relevance of stromal CD8⁺ TILs in EOC progression.

CD39, also known as nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (NTPDase 1), functions as the rate-limiting ectoenzyme catalyzing the hydrolysis of ATP to AMP25. CD39 has been implicated in diverse immune cell functions, particularly within the TME, where it is predominantly expressed on CD8+ T cells26,27. In bladder cancer, CD39+CD8+ T cells exhibit potent cytotoxic activity and produce higher levels of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)28. Similarly, in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), CD39+CD8+ TILs recognizing high-affinity neoantigens exhibit superior antitumor activity compared with their CD39⁻CD8⁺ counterparts29. A higher frequency of CD39+CD8+ TILs has also been associated with improved OS in HCC29 and rectal adenocarcinoma30.

These findings establish CD39 as a novel biomarker for identifying neoantigen-specific CD8⁺ T cells rather than bystander CD8⁺ T cells4,26,27,28. Nevertheless, data on the role of CD39+CD8+ TILs in EOC remain limited. Our study demonstrated that stromal CD39+CD8+ T cells were more abundant in platinum-sensitive patients and were correlated with prolonged OS. We also constructed predictive nomograms that integrated stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T-cell levels with clinical variables such as age, residual tumor size, platinum response, and progression-free interval. These nomograms showed high predictive accuracy for PFS and OS, as verified through calibration curves.

Despite these contributions, our study has several limitations. First, we did not assess the association between CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells in cytokeratin-negative (CK⁻) regions and specific histologic subtypes of EOC. Given the molecular heterogeneity of EOC subtypes, future multi-center studies with larger cohorts are warranted to validate these observations. Second, as this was an observational study, functional assays were not conducted. Mechanistic investigations are essential to elucidate the specific role of stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells in the immunoregulation of EOC. Third, CD39 is expressed by multiple stromal populations (e.g., endothelial cells and fibroblasts) in addition to T cells; thus, CD39⁺ expression within the stroma represents a composite signal, whereas CD39⁺CD8⁺ expression is specific to CD8⁺ T cells. Future studies will incorporate additional lineage markers (e.g., CD45, FOXP3, α-SMA) and spatial analyses to delineate the cellular origins of stromal CD39. Fourth, germline and somatic BRCA1/2 or TP53 mutational data were not available in this study; consequently, correlations between mutational status and stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells could not be assessed. Future prospective cohorts will include targeted sequencing to facilitate these analyses. Notably, previous studies in HGSOC have shown that favorable associations between CD8⁺ TILs and survival persist independent of BRCA1 germline status3.

This study offers important insights into the role of stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells within the TME of EOC, highlighting their association with platinum sensitivity and patient prognosis. Our findings suggest that stromal CD39+CD8+ T cells constitute a promising biomarker for predicting favorable OS in patients with advanced EOC. Although CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells have been linked to T-cell dysfunction in several solid tumors, their prognostic significance appears to be context dependent. In our EOC cohort, a higher density of stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells was correlated with platinum sensitivity and longer OS, consistent with the concept that CD39 marks tumor-reactive CD8⁺ T cells. Importantly, our findings are prognostic in nature and do not imply that patients experiencing relapse should receive additional chemotherapy solely based on elevated CD39⁺CD8⁺ T-cell levels. From a therapeutic standpoint, our findings support the CD39/CD73-mediated conversion of ATP to adenosine as a biologically relevant pathway in EOC. Determining whether therapeutic benefit arises from reinvigorating CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells or modulating extracellular adenosine will require further mechanistic and clinical investigations. Collectively, these observations identify stromal CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells as a prognostic biomarker in EOC and highlight the adenosine axis as a potential therapeutic target worthy of prospective evaluation, rather than suggesting the direct depletion of CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cells. Further research integrating functional analyses will be crucial for elucidating the underlying mechanisms of CD39⁺CD8⁺ T cell–mediated immune responses in EOC.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 (1), 12–49 (2024).

Kuroki, L. & Guntupalli, S. R. Treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. Bmj 371, m3773 (2020).

Goode, E. L. et al. Dose-Response association of CD8 + Tumor-Infiltrating lymphocytes and survival time in High-Grade serous ovarian cancer. JAMA Oncol. 3 (12), e173290 (2017).

Sato, E. et al. Intraepithelial CD8 + tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102 (51), 18538–18543 (2005).

Palucka, A. K. & Coussens, L. M. The Basis Oncoimmunology Cell., 164(6): 1233–1247. (2016).

Simoni, Y. et al. Bystander CD8(+) T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature 557 (7706), 575–579 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. Choosing the right timing for interval debulking surgery and perioperative chemotherapy May improve the prognosis of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a retrospective study. J. Ovarian Res. 14 (1), 49 (2021).

Ölmez, F. et al. High expression of CD8 in the tumor microenvironment is associated with PD-1 expression and patient survival in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Turk. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 19 (3), 246–256 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. The effect of polymorphisms in PD-1 gene on the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer and patients’ outcomes. Gynecol. Oncol. 144 (1), 140–145 (2017).

da Costa, A. A. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery and the risk of platinum resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 22 Suppl 3, S971–S978 (2015).

Dolled-Filhart, M. et al. Automated analysis of tissue microarrays. Methods Mol. Biol. 664, 151–162 (2010).

Camp, R. L., Dolled-Filhart, M. & Rimm, D. L. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin. Cancer Res. 10 (21), 7252–7259 (2004).

Buisseret, L. et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte composition, organization and PD-1/ PD-L1 expression are linked in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 6 (1), e1257452 (2017).

Brummel, K. et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes: from prognosis to treatment selection. Br. J. Cancer. 128 (3), 451–458 (2023).

Yao, W. et al. The prognostic value of Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 7525 (2017).

Miceska, S. et al. Association of Tumor-Infiltrating lymphocytes and inflammation status with survival outcome in patients with High-Grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Cancers (Basel), 17(14). p. e2269 (2025).

Gooden, M. J. et al. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer. 105 (1), 93–103 (2011).

Loi, S. et al. Tumor-Infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis: A pooled individual patient analysis of Early-Stage Triple-Negative breast cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 37 (7), 559–569 (2019).

Cao, G. et al. Tumor immune microenvironment changes are associated with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and long-term survival benefits in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: A pilot study. Front. Immunol. 14, 1022942 (2023).

Hamanishi, J. et al. The comprehensive assessment of local immune status of ovarian cancer by the clustering of multiple immune factors. Clin. Immunol. 141 (3), 338–347 (2011).

Barnett, J. C. et al. Ovarian cancer tumor infiltrating T-regulatory (T(reg)) cells are associated with a metastatic phenotype. Gynecol. Oncol. 116 (3), 556–562 (2010).

Xu, Y. et al. Higher numbers of T-Bet + Tumor-Infiltrating lymphocytes associate with better survival in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 41 (2), 475–483 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Effector T cells abrogate Stroma-Mediated chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Cell 165 (5), 1092–1105 (2016).

Zhang, T. et al. Lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration in omental metastases indicates poor prognosis in advance stage epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Int. Med. Res. 49 (12), 3000605211066245 (2021).

Allard, B. et al. The adenosine pathway in immuno-oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17 (10), 611–629 (2020).

de Tallón, P. et al. CD39(+)PD-1(+)CD8(+) T cells mediate metastatic dormancy in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 769 (2021).

Zhao, H. et al. What else can CD39 tell us? Front. Immunol. 8, 727 (2017).

Zhu, W. et al. CD8 + CD39 + T cells mediate Anti-Tumor cytotoxicity in bladder cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 14, 2149–2161 (2021).

Liu, T. et al. High-affinity neoantigens correlate with better prognosis and trigger potent antihepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) activity by activating CD39(+)CD8(+) T cells. Gut 70 (10), 1965–1977 (2021).

Duhen, T. et al. Co-expression of CD39 and CD103 identifies tumor-reactive CD8 T cells in human solid tumors. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 2724 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families, and the investigators who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province [grant number: H2020206385]; and the Scientific Research Fund of Hebei Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission [grant number: 20200099].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yan Li, Shan Kang, and Hai-Yan Sun designed the study and carried out the experiments. Hai-Yan Sun, Jian-Lei Wu and Xue-Ping Li recruited the patients and collected the data. Hai-Yan Sun, Yue-Ping Liu and Yan Li analyzed the data and prepared draft figures and tables. All authors were involved in writing the paper and provided final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University (NO. 2019MEC044), and informed consent was obtained from all of the recruited subjects according to the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, HY., Kang, S., Wu, JL. et al. Prognostic value of stromal CD39+CD8+ T cells in predicting platinum sensitivity and survival outcomes in epithelial ovarian cancer. Sci Rep 15, 42369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26383-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26383-5