Abstract

Thermal damage during bone drilling remains a significant concern in orthopaedic and dental surgeries. Excessive heat generation at the bone–drill interface can result in thermal necrosis and compromise implant stability. While several strategies have been proposed to mitigate intraoperative thermal injury, however, quantitative evaluations of staged drilling techniques remain limited. This study investigates the efficacy of a two-stage drilling strategy in reducing heat generation during cortical bone drilling. The approach involves creating an initial (pre-drilled) hole, followed by final enlargement to the target diameter (pilot hole). A validated three-dimensional dynamic elastoplastic finite element (FE) model was developed to simulate the bone drilling process and compare the bone temperature of conventional single-stage versus two-stage drilling techniques. Thermal analyses were conducted incorporating variations in the pre-to-pilot hole diameter ratio, feed force, and drill rotational speed. Simulation results indicated that a diameter ratio of 0.78 reduced peak bone temperatures by up to 12 °C compared to single-stage drilling. Further reductions in thermal accumulation were observed with increased feed forces of 40 N and 60 N. Increasing drill rotational speed from 800 to 2000 rpm decreased peak cortical bone temperatures from 57 °C to 43 °C. These findings demonstrate that the two-stage drilling strategy may mitigate thermal bone damage. The two-stage approach provides a practical solution to enhance thermal safety during implant site preparation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drilling is a common procedure in orthopaedic surgery, widely employed for bone screw insertion, implant fixation, and tissue transplantation. However, the high-speed rotation of the drill bit generates substantial frictional energy, which is subsequently converted into heat. This thermal energy accumulates at the drilling interface, resulting in a localised temperature rise. Excessive thermal elevation can induce heat-related damage to bone tissue, including osteonecrosis, reduced osteocyte viability, and delayed healing1,2. Experimental studies have demonstrated that osteoclast apoptosis may occur when bone temperature exceeds 50 °C, while temperatures above 70 °C can cause irreversible protein denaturation, thereby inhibiting cellular regeneration and potentially compromising the structural integrity of the operative site3,4,5,6. Under high-speed and high-load drilling conditions, intramedullary temperatures may exceed the thermal tolerance thresholds of osteogenic cells7,8,9. Moreover, beyond thermal effects, drilling also induces mechanical vibrations and stress concentrations, which contribute to the formation of microcracks within the bone matrix10,11,12,13. These microstructural defects may further weaken the bone strength and hinder successful implant fixation. Given the combined thermal and mechanical challenges, minimising the adverse effects of bone drilling remains a key concern in both clinical orthopaedics and dentistry. Strategies to reduce heat generation and mechanical trauma during bone drilling can generally be classified into the following categories:

Drill design improvements The geometry of the drill bit plays a crucial role in minimising thermal effects during bone drilling. For instance, increasing the helix angle can enhance the evacuation of bone chips, thereby reducing frictional contact time and overall heat generation. Optimising the cutting-edge geometry—such as the point angle, rake angle, and tip configuration—can improve cutting efficiency, lower drilling resistance, and consequently reduce heat buildup at the bone–tool interface14. Additionally, incorporating multi-flute designs, like double or triple spiral flutes, helps to further reduce mechanical resistance and improve bone chip removal, which contributes to lower temperature rises during the drilling process15,16.

Adjustment of operating parameters Selecting appropriate drilling speed and applied pressure is crucial to minimising heat generation during the drilling process. Studies have shown that lower drilling speeds can significantly reduce frictional heat17. In general, a moderate rotational speed is recommended—drilling too fast can increase friction and temperature, while drilling too slowly can unnecessarily prolong the procedure. Gaspar et al.18 have suggested the optimal drilling speeds, which are typically in the range of 800 to 1200 revolutions per minute (rpm). Additionally, applying excessive feed pressure increases frictional resistance, which in turn leads to greater heat buildup19,20,21. Several researchers have reported that cortical bone temperatures are inversely related to drilling forces22,23,24,25. The thinning is effective in reducing the thrust force, and a quick helix is effective for reducing temperature rise and duration when drilling the cortical bone. Although the exact cause of this temperature reduction remains unclear, applying greater force may shorten the time required to penetrate the cortical bone26,27. Effective temperature control can therefore be achieved through careful regulation of the applied force and adherence to proper drilling techniques.

Cooling technologies Cooling technologies are generally categorised into external and internal methods. External cooling typically involves irrigating the drilling site with physiological saline or specialised cooling fluids, which are sprayed onto the bone surface to dissipate heat and reduce friction. Conversely, an alternative approach called “internal cooling” utilises specially designed drills whose structures include cooling channels inside themselves that deliver coolant directly to the drill bit–bone interface. This targeted approach enables more effective and precise heat dissipation, significantly lowering the risk of thermal damage to surrounding bone tissue22,23,24,25. Moreover, drill bit materials and surface coatings also play an important role in managing heat during bone drilling. Drill bits made from materials with high thermal conductivity—such as titanium alloys, ceramics, or those coated with diamond—enable more efficient heat dissipation, thereby reducing thermal accumulation. Additionally, specialised coatings like diamond coatings improve wear resistance and lower friction, which further helps to minimise heat generation during the drilling process26,27. As well as the intermittent or pulsed drilling techniques, using periodically withdrawing the drill bit from the drill-bone contact surface, allowing brief pauses for heat dissipation and reducing the rate of thermal accumulation. By interrupting continuous frictional contact, this method may effectively limit temperature rise and lower the risk of thermal injury to the surrounding bone tissue20,25.

Overall, cooling techniques have proven effective in mitigating temperature increases during bone drilling. However, further advancements in drill bit design, material selection, and the integration of cooling systems are necessary to optimise their performance. The combined application of these strategies can significantly reduce thermal damage, leading to improved surgical outcomes and lowering the risk of complications such as thermal necrosis, delayed healing, and bone fractures.

Studies have shown that the primary source of heat during bone drilling is concentrated at the tip of the drill bit28. This heat is primarily generated by shear deformation at the cutting tip and friction between the drill bit and the bone, with the location of heat generation varying depending on the drilling depth29,30. In the current technology for measuring bone temperature during drilling, the temperature is typically measured using thermocouples or infrared cameras. Thermocouples are positioned to monitor local temperatures around the drill hole, usually at depths of 0.5–1.0 mm; however, they do not provide a three-dimensional temperature profile. In contrast, infrared cameras can measure surface temperatures but are unable to capture internal temperature variations within the hole31,32,33. As a result, accurately measuring temperatures at the drill tip or hole edges during drilling remains a significant challenge. Furthermore, due to substantial biological variability between animal and human bones, conducting precise experimental studies across all relevant parameters is difficult. Consequently, numerically validated models have emerged as one of the most effective methods for evaluating heat distribution and determining optimal drilling parameters34,35,36,37,38,39.

An effective analytical model is essential for capturing variables that are difficult to measure directly during bone drilling and serves as a valuable tool for evaluating outcomes by parametrically varying geometric configurations, material properties, and drill bit designs. Such models help understand difficult-to-study parameters, such as friction between the bone and drill bit, residual stresses, heat distribution within bone tissue and their corresponding effects. This approach enables the assessment of thermal effects during drilling and identifies areas at higher risk of bone thermal necrosis by highlighting thermally affected zones. Research indicates that using a larger-diameter drill bit results in a higher temperature rise. While increasing the applied load (feed force) can effectively reduce the temperature rise in bone, the excessive load increases the risk of bone fracture around the drill hole19,21,39. Therefore, this study proposes a clinically feasible solution to reduce temperature rise and minimise the risk of thermal damage to bone tissue.

Clinically, bone screws with diameters of 2.7, 3.2, 3.5 and 4.5 mm are frequently used in orthopaedic and plastic surgeries. Insertion of bone screws typically requires the prior creation of a pilot hole, which guides the screw trajectory and facilitates its insertion. The pilot hole diameter is typically drilled 0.3–1.0 mm smaller than the thread diameter of the bone screw to optimise the mechanical interlocking between the bone screw and the surrounding bone. Studies have shown that drilling a 4.5 mm pilot hole can generate temperatures exceeding 47 °C, a critical threshold beyond which thermally induced osteonecrosis may occur, potentially compromising implant stability6. Because the drilling process inherently produces significant thermal energy, temperatures surpassing physiological tolerance can negatively impact bone viability and clinical outcomes. Therefore, effective thermal regulation during bone drilling is essential to ensure surgical success and the long-term stability of implants.

To address this issue, the present study employed a two-stage drilling protocol aimed at reducing thermal elevation during bone drilling. In the first stage, a smaller-diameter preliminary hole (Dpre) is drilled, followed by the creation of the final pilot hole (Dpilot) using a larger-diameter drill bit. We hypothesised that this two-stage drilling strategy can effectively minimise temperature rise, thus reducing the risk of thermal necrosis. To assess the thermal effects of this technique, a three-dimensional dynamic elastoplastic finite element model was developed to analyse the impact of the two-stage drilling method on bone temperature elevation and evaluate the thermal effects of this approach.

Construction of the model

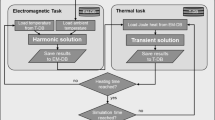

This study constructed a three-dimensional dynamic elastoplastic finite element model using ABAQUS software (Dassault Systèmes, ABAQUS Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) to investigate temperature rise in bone tissue during drilling. Since the thermal effects are primarily localised around the drilling site, the drilling process can be considered an axisymmetric behaviour, modelled using a cylindrical coordinate system. In this model, the coordinate origin is located at the cortical bone surface, with the x-axis (radial coordinate) representing the outward distance from the drill hole edge, whereas the z-axis denotes the depth relative to the bone surface. A simplified cylindrical geometry was used for the simulation. The model featured a drill hole with a depth of 4 mm, enclosed by bone material with a diameter and height of 8 mm. The geometric configuration and finite element mesh are illustrated in Fig. 1. The drill bit is made of stainless steel, with a point angle of 108° and 23° helix angle. The diameters are 3.2 mm and/or 4.5 mm. The bone structure was modelled as two distinct layers: an upper cortical bone layer with a thickness of 4 mm and a lower cancellous (spongy) bone layer, also 4 mm thick. The thickness of human cortical bone varies with anatomical location, age, sex, and individual differences, and no single fixed value can be defined. In general, the diaphysis of long bones (e.g., femur, tibia) exhibits the greatest cortical thickness, typically ranging from 4 to 8 mm, and reaching up to 8–10 mm at the midshaft of the femur. In the upper limb long bones (e.g., humerus, radius, ulna), cortical thickness is approximately 2–6 mm. The cortical layer of the skull is relatively thinner, usually between 5 and 12 mm. The vertebrae present the thinnest cortical bone, approximately 0.4–1 mm, with the majority of their structure composed of trabecular bone. The thickness of cortical bone influences the drilling temperature: greater cortical thickness leads to higher temperatures. However, once drilling advances from cortical into cancellous bone, the temperature decreases. In our model, both cortical and cancellous bone thicknesses were set at 4 mm, according to literature findings and clinical measurements40,41,42,43,44,45. Both the drill bit and the cortical bone were meshed using three-dimensional hexahedral eight-node elements.

In this model, a pre-drilled hole with a diameter of 2.5 mm (Dpre = 2.5 mm) was created in the initial stage. This was followed by pilot hole drilling using either a 3.2–4.5 mm diameter drill bit in the second stage. A surface-to-surface frictional contact was established between the drill bit and the bone tissue. In this configuration, the rigid surface of the drill bit was designated as the master surface, while the deformable bone surface was defined as the slave surface. The surface-to-surface contact discretisation method was used for the interaction calculation to prevent erroneous contact due to the penetration of slave nodes into the master surface.

During the drilling simulation, the temperature rise within the bone evolved. To capture this behaviour, the dynamic temperature-displacement analysis module in ABAQUS was utilised, incorporating an explicit time integration scheme to ensure computational efficiency and accuracy in transient thermal analysis. All nodes on the cylindrical surface of the bone model were fully constrained in all six degrees of freedom to simulate fixed boundary conditions. The drilling process was simulated in three sequential phases: cutting, retraction, and stationary. The material properties applied in the simulation are summarised in Table 137,38.

The heat generated at the contact interface between the drill bit and the bone was conducted into both materials. The heat flux absorbed by the deformable slave surface (bone) was scaled by a heat partition factor, f, while the heat flux entering the rigid master surface (drill bit) was weighted by 1−f47. In this study, an initially equal heat distribution was assumed, and a heat partition factor of 0.5 was assigned. The Johnson-Cook damage criterion was employed to simulate material failure and damage evolution48,49. In this study, the damage initiation occurred when the equivalent plastic strain in an element reached 0.3 mm, and then the corresponding bone elements were removed from the model. This element removal was governed by a ductile failure strain threshold of 0.008. The criterion, previously validated in finite element simulations of bone cutting, was employed in this study to control element deletion during the drilling process.

As the drilling process progressed, the contact point between the drill bit and the bone continuously shifted. As a result, after the initial phase of drilling, the cooler surrounding bone tissue increasingly absorbed the generated heat, while the amount of heat transferred into the drill bit gradually decreased. This dynamic redistribution resulted in a time-dependent variation in the heat partition factor, which did not remain constant throughout the drilling process. The thermal interaction at the bone–drill interface was modelled using a surface-to-surface contact discretisation. Contact properties were defined accordingly, with frictional behaviour captured through a surface-to-surface contact formulation. A coefficient of friction of 0.3 was assumed to characterise the interaction between the drill bit and the bone surfaces47.

Bone drilling experiments

Experimental validation of the finite element (FE) model was conducted using fresh bovine cortical bone harvested from the mid-diaphysis of the tibia, which has been shown to closely replicate the mechanical and thermal properties of human cortical bone3,46,47,48,49. Specimens were obtained from a local slaughterhouse shortly after slaughter and were immediately preserved in saline solution, then stored at − 40 °C to maintain tissue integrity. Prior to experimentation, the specimens were fully thawed at room temperature for 24 h and maintained in saline solution to preserve hydration until testing. Quantitative 64-slice computed tomography (CT) was used to determine the mean apparent density of the bone specimen. Calibration was done using two known density phantoms (160 and 320 mg/cm2) to find the Hounsfield Unit (HU) value. The bone mineral density (BMD) of the specimen (identified from the HU value) was 1.64 g/cm2. Three commercially available drill bits with diameters of 2.5, 3.2 and 4.5 mm (Synthes, Switzerland) were used for the experimental validation of the model.

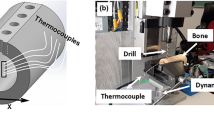

Before the experiment, the bone specimen was fully submerged in isotonic saline at room temperature for 12 h to ensure complete thawing. A pre-drilled hole was created in the first stage, followed by pilot-hole drilling in the second stage. Four thermocouples were strategically placed 0.5 mm from the lateral edge of the drill bit, circumferentially distributed at 90° intervals and positioned at two depths (2.0 mm and 4.0 mm). The thermocouple was positioned 0.5 mm from the drill hole wall to capture temperature changes in the region most susceptible to thermal injury. This location reflects the zone where heat generated during drilling is most likely to exceed critical thresholds and cause bone necrosis. At the same time, a slight offset from the hole wall prevented direct contact with the drill bit, thereby avoiding sensor damage or measurement artefacts. Furthermore, the 0.5 mm distance provides a practical and reproducible setup that has been widely adopted in bone drilling studies to represent local peak thermal exposure. The specific locations and depths are illustrated in Fig. 2. Thermal paste (silicon) was used to fill the thermocouple holes to minimise heat loss due to air gaps. The specimen was rigidly mounted at both ends on an x-y positioning stage, which served as the experimental platform.

(A) Diameters of the pre-drilled hole (Dpre), pilot hole (Dpilot). A small-diameter drill was first used to create an initial pre-drilled hole, followed by the second-stage drilling of the pilot hole, which began at the drill–bone contact point. (B) Positions of four thermocouple holes, at depths of z = 2 mm and z = 4 mm.

A commonly used battery-powered surgical handpiece (drill) (Synthes, Germany), operating at a constant rotational speed of 1200 rpm, was vertically mounted above the platform. Axial feed force was applied via an electro-mechanical testing system (Instron ElectroPuls E3000, USA), enabling precise regulation of drilling parameters and facilitating real-time thermal response monitoring. The complete experimental configuration is illustrated in Fig. 3.

To replicate physiological conditions, the laboratory air conditioning was set to 37 °C and maintained for approximately one hour before the experiment commenced. Ambient temperature and humidity were continuously monitored throughout the procedure. During the experiment, the room temperature was kept at 37 ± 1.0 °C, with a relative humidity of approximately 55%. Once the specified feed force was set, the drilling process commenced. Upon reaching the designated depth, the drill bit was retracted to its original position, and operation ceased. The specimen was subsequently allowed to cool naturally under ambient conditions. Temperature signals from the embedded thermocouples were continuously transmitted to a data acquisition system and stored for subsequent processing and analysis.

Validation of the FE model

A dynamic elastoplastic finite element (FE) model was developed in this study, comprising approximately 56,120 elements and 64,300 nodes. Convergence analysis, presented in Fig. 4, demonstrated that the simulated bone temperature stabilised when the number of elements reached 31,679, indicating sufficient mesh resolution for accurate thermal predictions.

Model validation was conducted by comparing the FE simulation results with experimental data under two drilling scenarios. In the first case (Fig. 5A), drilling was performed using a 3.2 mm diameter bit under a feed force of 20 N, rotational speed of 1200 rpm, and bone density of 1.64 g/cm2. The temperature was recorded 0.5 mm from the hole edge at a depth of 4 mm. The simulation predicted a peak bone temperature of 49.5 °C, closely aligning with the experimental value of 48.2 °C. The corresponding times to peak temperature were 5.8 s (simulation) and 6.6 s (experiment), yielding maximum deviations of 1.3 °C and 0.8 s, respectively. In the second case (Fig. 5B), the simulated and measured peak temperatures were 53.6 °C and 52.2 °C, respectively, with the corresponding times to peak temperature recorded as 11.1 s and 11.9 s. The maximum discrepancies in this scenario were 1.4 °C for temperature and 0.8 s for time. In these two cases, the peak temperature in the simulation appears earlier than in the experiment. The observed discrepancy may be attributed to differences in material properties. The porcine femur used in the experiments exhibits anisotropic behaviour, whereas in the FE model, the bone was represented as an isotropic material. Moreover, the cooling effect of water content or blood in animal (or human) bone may partially dissipate the heat generated during drilling. In our experiments, the porcine femur contains a certain amount of moisture, leading to a relative humidity higher than that assumed in the simulation (no humidity). This moisture may lubricate the interface between the bone and the drill, thereby reducing frictional heat generation and limiting the temperature rise. These results collectively demonstrate the accuracy and robustness of the proposed dynamic FE model in predicting temperature evolution during bone drilling procedures.

Comparison of temperature elevation between the simulation model and experimental results. The model was validated at two different depths: (A) z = 2.0 mm; (B) z = 4.0 mm, under the conditions of a pre-drilled hole (Dpre = 2.5 mm) and a pilot hole (Dpilot = 4.5 mm) with a rotational speed of 2000 rpm. The blue solid line indicates the mean temperature from five drilling trials; the green and purple dashed lines represent the upper and lower bounds of temperature variation, respectively.

Results and discussion

This study investigates the thermal effects of a two-stage bone drilling procedure. In the first stage, a smaller-diameter drill was used to create a pre-drilled hole (Dpre), followed by a second stage in which a larger-diameter drill bit (Dpilot) completed the final drilling. The resulting bone temperatures were then compared with those generated by a conventional single-stage drilling process, in which the target hole is created directly without a pre-drilled guide.

Figure 6(A) compares the temperature-time curves for 3.2 mm bone drilling with and without a pre-drilled hole. The feed force was set at 20 N, and the drill’s rotational speed was 1200 rpm. In the first stage, a 2.5 mm pilot hole was drilled, and after a 15-second interval, a 3.2 mm drill bit was used to complete the final drilling (second stage), resulting in a pre-drilled-to-pilot diameter ratio of (Dpre/Dpilot = 0.78). The figure shows that the bone temperature distribution exhibited two peak values after pre-drilling. The first peak corresponded to the thermal rise induced by the 2.5 mm pilot hole drilling, while the second peak resulted from the subsequent drilling with the 3.2 mm drill bit. The results indicated that the maximum bone temperature reached 53 °C in the single-stage process, whereas the two-stage process reduced the temperature to 41 °C, achieving a 12 °C reduction. Figure 6(B) illustrates the effect of a 2.5 mm pre-drilled hole on temperature elevation during 4.5 mm bone drilling, with a pre-drilled-to-pilot diameter ratio of (Dpre/Dpilot = 0.55). The results showed that even with the 2.5 mm pre-drilled hole, the temperature rise remained high when the 4.5 mm drill was used in the second stage, indicating that this approach was ineffective in reducing bone temperature. Figure 6(C) depicts the temperature profile for 4.5 mm pilot hole drilling with a 3.2 mm pre-drilled hole, where the pre-drilled-to-pilot diameter ratio was (Dpre/Dpilot = 0.71). The results showed that at a depth of z=4 mm, the maximum bone temperature without pre-drilling reached 91 °C. However, with a 3.2 mm pilot hole, the maximum temperature dropped to 53 °C, effectively reducing the peak temperature by 38 °C. Studies have shown that bone temperatures exceeding 47 °C for more than 1 min may lead to thermal damage to bone tissue2. Although the two-stage approach in this case resulted in a peak temperature of 53 °C, the duration for which the temperature exceeded the critical threshold of 47 °C was limited to approximately 5 s. These findings indicate that the risk of significant thermal damage to bone tissue using the two-stage drilling procedure is minimal.

Comparison of drilling time versus bone temperature variation during pilot hole drilling with and without pre-drilling. (A) Pre-drilled hole: 2.5 mm; pilot hole: 3.2 mm (Dpre/Dpilot = 0.78); (B) Pre-drilled hole: 2.5 mm; pilot hole: 4.5 mm (Dpre/Dpilot = 0.55); (C) Pre-drilled hole: 3.2 mm; pilot hole: 4.5 mm (Dpre/Dpilot = 0.71).

Previous studies have demonstrated that cutting force decreases as the rake angle increases from negative to positive values50,51,52,53,54,55. Positive rake angles are typically incorporated into the cutting edges at the drill bit web, with the rake angle gradually diminishing toward the chisel edge. Larger rake angles facilitate smoother and more efficient cutting58,59,60. Clinically, most bone drills employ a positive-rake design, which has been shown to enhance cutting efficiency while minimising friction-induced temperature elevation in bone. Despite these advances, the effects of specific drill design features—such as thinning geometry, cutting force, and thermal response—remain underexplored. Ueda et al. reported that thinning-type drills effectively reduce thrust force, and that a steeper helix angle contributes to lower temperature rise and shorter drilling duration when penetrating cortical bone60. Sugita et al. further improved tool penetration by introducing an auxiliary cutting edge beneath the chisel edge, thereby reducing cutting force and shortening operation time. In conventional bone drilling, the chisel edge located at the drill tip centre primarily initiates bone penetration. Unlike the peripheral cutting edges, the chisel edge does not efficiently cut material; rather, it deforms and displaces bone. This mechanism generates substantial localised friction and resistance, which are primary contributors to heat accumulation at the drill tip. Moreover, the negative rake angle of the chisel edge amplifies compressive forces on the bone, increasing frictional energy and the risk of thermonecrosis, particularly in cortical bone where thermal conductivity is low.

A novel low-trauma, self-centring drill bit has been designed with a larger helix angle and a smaller web to facilitate chip evacuation and accelerate heat dissipation, thereby improving bone drilling performance54,55. This approach involves modifying drill geometry to reduce drilling temperature54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63. Although effective, it represents a novel drill configuration that has not yet been widely adopted in clinical practice. Similarly, Wang et al. developed a novel oscillating saw blade incorporating embedded flexible structures to reduce overall cutting forces and temperature rise56,57. This design also minimises tooth wear and suppresses crack propagation along the flute walls. In contrast to these two geometry-based methods, our approach employs an alternative strategy. In our study, we used two drill diameters commonly applied in clinical practice, sequentially from smaller to larger, to achieve a comparable reduction in drilling temperature.

In this study, a two-stage drilling strategy was implemented to investigate the thermal effects of a two-stage bone drilling procedure, in which two bone drills of different diameters were employed sequentially. In the first stage, a smaller-diameter drill was used to create a pre-drill hole (Dpre) and subsequently retracted upon reaching the target depth. In the second stage, a larger-diameter drill (Dpilot) was guided along the formed pre-drill hole to complete the drilling procedure. This sequential use of two drills with different diameters offers several clinical advantages: the predrilled hole created in the first stage facilitates the penetration of air or coolant into the cavity, while the prior removal of part of the cortical bone reduces the amount of material to be cut in the subsequent stage. Therefore, the two-stage drilling procedure can effectively reduce the heat generated during bone drilling.

Figure 7(A) presents bone temperature variations at different depths during second-stage drilling, where a 2.5 mm pre-drilled hole was followed by a 3.2 mm drill to complete the pilot hole. The results indicate that the two-stage drilling approach maintains cortical bone temperatures below 42 °C. Given that temperatures exceeding 45–50 °C can induce thermal damage2,3,6,7,8,9, these findings confirm that no excessive heating occurs within the cortical bone, suggesting that this technique effectively reduces the risk of thermal injury or necrosis. Figure 7B illustrates the temperature distribution at various depths for drilling with a 2.5 mm pre-drilled hole followed by a 4.5 mm pilot drill. The results show that bone temperatures exceeded 47 °C for more than 30 s. While the pre-drilled hole reduced the peak temperature by approximately 12 °C at a depth of z = 2 mm, it had minimal effect at z = 4 mm, indicating that the thermal mitigation was limited in deeper regions of the bone.

(A) Drilling with a 3.2 mm pilot hole following a 2.5 mm pre-drilled hole; (B) Drilling with a 4.5 mm pilot hole following a 2.5 mm pre-drilled hole.

Figure 8A illustrates the bone temperature distribution at various depths during drilling with a 4.5 mm drill following the creation of a 3.2 mm pre-drilled hole, under a feed force of 20 N and a rotational speed of 800 rpm. The results indicate that the maximum bone temperature remained below 57 °C but exceeded the critical threshold of 47 °C. Figure 8B presents the temperature distribution when the rotational speed was increased to 2000 rpm. Under these conditions, the maximum bone temperature decreased from 57 °C to 43 °C, and temperatures within a 4 mm depth remained below 47 °C. These results are consistent with previous studies, confirming that higher drilling speeds enhance cutting efficiency, reduce operation time, and mitigate heat generation and thermal propagation. Notably, this beneficial effect persists even when a pre-drilled hole is employed.

Figures 9(A) and 9(B) depict the bone temperature distribution at various depths during drilling with a 4.5 mm drill following a 3.2 mm pre-drilled hole, at a rotational speed of 800 rpm and feed forces of 40 N and 60 N, respectively. The results demonstrate that increasing the feed force effectively reduces bone temperature during drilling. Under both loading conditions, the maximum bone temperature remained below 50 °C, indicating that higher feed forces can contribute to thermal mitigation during the drilling process.

Various techniques have been employed to mitigate thermal effects during bone drilling, with their effectiveness influenced by surgical procedure, anatomical site, and individual patient-related factors. However, strategies aimed at minimising heat generation must consider trade-offs among procedural complexity, cost, and clinical efficacy. While advancements in drill bit design and cooling technologies are widely adopted, emerging drilling methods offer additional potential for improving thermal control in orthopaedic applications. Mathews et al. measured the maximum temperatures and the durations of temperatures in human-cadaver cortical bones. Their results showed the maximum temperatures and the durations of temperatures in excess of 55 °C during experimental insertion of external skeletal-immobilisation pins61. When drilling was performed without specific cooling measures, cortical temperatures frequently exceeded 100 °C. The applied drilling force was found to be a more critical determinant than drilling speed in influencing both the magnitude and duration of cortical temperature elevations. Increasing the applied force was associated with lower peak temperatures and shorter durations of temperature rise. Worn drills produced substantially greater temperature increases compared with new drills. Their research indicates that coolant application, feed rate, and feed force have a significant impact on bone temperature rise. In our study, a two-stage drilling technique was used, in which an initial smaller-diameter drill was used to create a pre-drilled hole, subsequently enlarged to the final pilot diameter. During the drilling, the coolant was not used in our study. It is hypothesised that friction between the drill bit and bone is the primary contributor to temperature rise. Previous studies have shown a positive correlation between drill bit diameter and heat generation3,8,15. In comparison, the smaller-diameter drill used in the initial stage generates less heat. Additionally, material removal during this first stage decreases the contact surface and friction encountered in the subsequent stage, leading to reduced overall heat accumulation.

Our previous research indicates that, when using a 3.5 mm drill bit at 800 rpm, the thermal affected zone (TAZ) extends approximately 0.3–0.8 mm, potentially overlapping with the cutting area of the second-stage drilling and reducing its effectiveness. This limitation underscores the importance of considering TAZ effects in multi-stage drilling protocols to minimise thermal damage and optimise clinical outcomes39. These findings indicate that a two-stage drilling technique can effectively lower bone temperature without requiring changes to drill design or the use of supplementary cooling systems. The two-stage drilling generally reduces peak temperatures; however, it does not fully eliminate the risk of thermal injury under all conditions. Further research and experimental validation are necessary to optimise this method and evaluate its clinical relevance.

Coolant or saline irrigation is a widely used method to manage heat generation during bone drilling63,64,65,66,67,68. Typically, coolant is applied to the bone surface before drilling and intermittently throughout the procedure. However, research has shown that this technique offers only limited effectiveness in controlling temperature rise64,65,66,67, largely because most of the frictional heat is generated at the rotating drill tip during bone cutting. Bone chips produced by the drill’s flank often travel along the flutes, obstructing coolant access to the drill hole and thereby reducing cooling efficiency. To overcome this limitation, some researchers have designed hollow bone drills with apertures at the tip, allowing for direct coolant delivery to the drilling site and enhanced thermal regulation24,25. Several studies have suggested pre-cooling the drill bit or using low-temperature coolant as strategies to improve thermal regulation during bone drilling65,66,67,68,69. However, these approaches require additional preoperative preparation and specialised equipment, and may still fail to provide consistent temperature control throughout the procedure. In clinical settings, the drill bit often warms up before use, making it difficult to maintain its pre-cooled state. Furthermore, limited coolant penetration into the drill hole significantly reduces its cooling efficacy. In this study, a two-stage drilling strategy was introduced. In the initial stage, a pre-drilled hole facilitated improved coolant access to the inner drilling site, ensuring the presence of coolant during the subsequent pilot drilling phase. This not only enhanced lubrication at the drill–bone interface but also effectively reduced frictional heat generation. By integrating the two-stage drilling approach with conventional irrigation, effective thermal management was achieved without requiring additional equipment. Although the present model did not incorporate fluid–structure interaction effects between the coolant and bone, a conservative modelling framework was adopted to evaluate and minimise the risk of thermal damage to bone tissue.

The two-stage drilling approach was found to be effective in reducing bone temperature elevation, particularly when the diameter ratio between the pre-drilled hole and the pilot hole (Dpre/Dpilot) exceeded 0.75. This parameter played a critical role in thermal mitigation. The underlying mechanism lies in the segmentation of the drilling process, which limits energy conversion and heat accumulation during each phase. The initial pre-drilled hole served as a thermal channel, promoting more effective heat dissipation and preventing excessive localised temperature spikes. Moreover, partial bone removal in the first stage reduced drilling resistance and decreased the contact surface area during the second stage, thereby limiting additional heat generation. Consequently, maintaining an optimal ratio between the pre-drilled and pilot hole diameters is critical for minimising peak bone temperatures and lowering the risk of thermally induced tissue damage during bone drilling. In addition to employing a two-stage drilling technique, the selection of appropriate drilling parameters is critical for controlling thermal elevation in bone. Previous studies have demonstrated that increasing either the rotational speed or the feed force can attenuate temperature rise during drilling. Elevated rotational speeds reduce the duration of cutting, thereby enhancing heat dissipation. Similarly, higher feed forces or feed rates shorten the overall drilling time, which limits heat accumulation and reduces frictional interaction between the drill bit and bone tissue. However, the optimisation of these parameters must be customised based on bone quality and surgical objectives. Excessive rotational speed may cause thermal necrosis, while overly aggressive feed forces can lead to microfractures in the surrounding cortical structure. Consequently, further studies are warranted to determine the optimal parameter set, taking into account bone heterogeneity, procedural goals, and overall drilling efficiency.

This study has several limitations. First, in clinical practice, bone drilling is performed by the surgeon, with feed force and feed rate adjusted based on real-time conditions. However, in this study, feed forces (20, 40, and 60 N) were kept constant during the drilling process, which may have introduced discrepancies compared to actual clinical scenarios. Second, although coolant is commonly applied during bone drilling, typically by spraying, the pre-drilled hole may cause coolant to flow into it, providing cooling as well as lubrication to reduce frictional heat. This effect was not considered in the present study. Third, bone density has a significant influence on drilling temperature. This study considered only a single bone density, which limits the generalizability of the proposed model to conditions involving variable bone densities. Fourth, the effectiveness of the proposed strategy may depend on drill size, feed rate, rotational speed, and bone properties. Future studies are needed to optimise these parameters and further reduce the risk of thermal damage. Finally, the finite element (FE) model used in this study did not account for bone moisture and blood perfusion, which may have resulted in simulated temperatures higher than those observed under physiological conditions. Future work could incorporate anatomically realistic geometries and physiological factors to validate and extend our findings.

Conclusions

This study developed a two-stage bone drilling procedure in an attempt to reduce the heat generation during the bone drilling process. A validated three-dimensional dynamic elastoplastic finite element model was used to analyse heat transfer during bone drilling, addressing the limitations of conventional experimental methods in capturing interface temperatures. Our results demonstrated that employing a two-stage drilling protocol, particularly when the diameter ratio between successive drilling steps exceeded 0.78, significantly reduced peak temperatures, thereby mitigating the risk of thermal-induced bone damage. Additionally, the optimisation of drilling parameters, including spindle speed and feed force, further reduced thermal exposure. These findings contribute to enhancing surgical safety and offer valuable insights for future surgical optimisations and the development of advanced surgical instruments. Despite a slight increase in operative time, the two-stage drilling procedure offers a simple, safe, and clinically feasible strategy to reduce the risk of thermal necrosis and can be readily adopted in surgical practice. Future work will focus on the experimental study of the optimised two-stage drilling protocols in vitro and/or in vivo environments to further substantiate their clinical applicability.

Data availability

Data are contained within the article.

References

Karmani, S. The thermal properties of bone and the effects of surgical intervention. Curr. Orthop. 52, 20–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cuor.2005.09.011 (2006).

Eriksson, A. R. & Albrektsson, T. Temperature threshold levels for heat-induced bone tissue injury: a vital-microscopic study in the rabbit. J. Prosthet. Dent. 50, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(83)90174-9 (1983).

Hillery, M. T. & Shuaib, I. Temperature effects in the drilling of human and bovine bone. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 92, 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-0136(99)00155-7 (1999).

Krause, W. R. Orthogonal bone cutting: saw design and operating characteristics. J. Biomech. Eng. 109, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3138679 (1987).

Biyikli, S. & Modest, M. F. Energy requirements for osteotomy of femora and tibiae with a moving CW CO₂ laser. Lasers Surg. Med. 7, 512–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.1900070614 (1987).

Augustin, G. et al. Thermal osteonecrosis and bone drilling parameters revisited. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 128, 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-007-0427-3 (2008).

Möhlhenrich, S. C., Modabber, A., Steiner, T., Mitchell, D. A. & Hölzle, F. Corrigendum to heat generation and drill wear during dental implant site preparation: systematic review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 54, 117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.11.005 (2016).

Mishra, S. K. & Chowdhary, R. Heat generated by dental implant drills during osteotomy—a review. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 14, 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13191-014-0350-6 (2014).

Tehemar, S. H. Factors affecting heat generation during implant site preparation: a review of biologic observations and future considerations. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 14, 1 (1999).

Carter, D. R., Caler, W. E., Spengler, D. M. & Frankel, V. H. Fatigue behavior of adult cortical bone: the influence of mean strain and strain range. Acta Orthop. Scand. 52, 481–490. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453678108992136 (1981).

Vashishth, D., Behiri, J. C. & Bonfield, W. Crack growth resistance in cortical bone: concept of microcrack toughening. J. Biomech. 30, 763–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290( (1997). 97)00029 – 8.

Burr, D. B. et al. Does microdamage accumulation affect the mechanical properties of bone? J. Biomech. 31, 337–345 (1998). 10.1016/S0021-9290(98)00016 – 5.

Barak, M. M., Currey, J. D., Weiner, S. & Shahar, R. Are tensile and compressive young’s moduli of compact bone different? J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.03.004 (2009).

Lee, J., Rabin, Y. & Ozdoganlar, O. B. A new thermal model for bone drilling with applications to orthopaedic surgery. Med. Eng. Phys. 33, 1234–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2011.05.014 (2011).

Akhbar, M. F. A. & Sulong, A. W. Surgical drill bit design and thermomechanical damage in bone drilling: a review. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 49, 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-020-02600-2 (2021).

Bertollo, N., Gothelf, T. K. & Walsh, W. R. 3-Fluted orthopaedic drills exhibit superior bending stiffness to their 2-fluted rivals. Injury 39, 734–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2007.11.286 (2008).

Singh, T. S. P., Yusoff, A. H. & Chian, Y. K. How safe is high-speed burring in spine surgery? Spine 40, E866–E872. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000985 (2015).

Gaspar, J., Borrecho, G., Oliveira, P. & Salvado, F. Martins Dos Santos, J. Osteotomy at low-speed drilling without irrigation versus high-speed drilling with irrigation. Acta Med. Port. 26, 231–236 (2013).

Lee, J., Gozen, B. A. & Ozdoganlar, O. B. Modeling and experimentation of bone drilling forces. J. Biomech. 45, 1076–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.12.012 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Experimental investigations on microcracks in vibrational and conventional drilling of cortical bone. J. Nanomater. 2013, 845205. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/845205 (2013).

Xu, L. et al. Drilling force and temperature of bone under dry and physiological drilling conditions. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 27, 1240–1248. https://doi.org/10.3901/CJME.2014.0912.151 (2014).

Matthews, L. S. & Hirsch, C. Temperatures measured in human cortical bone when drilling. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 54, 297–308 (1972).

Brisman, D. L. The effect of speed, pressure, and time on bone temperature during the drilling of implant sites. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 11, 35–37 (1996).

Liao, Z., Axinte, D. & Gao, D. On modelling of cutting force and temperature in bone milling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 266, 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2018.11.043 (2019).

Wang, H., Satake, U. & Enomoto, T. Modeling of oscillating bone sawing forces with instantaneous cutting speed and depth of cut. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 324, 118225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2023.118225 (2024).

Sener, B. C., Dergin, G., Gursoy, B., Kelesoglu, E. & Slih, I. Effects of irrigation temperature on heat control in vitro at different drilling depths. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 20, 294–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01643.x (2009).

Al-Dabag, A. N. & Ahmed, A. S. Effect of cooling an irrigation solution during Preparation of implant site on heat generation using elite system for implant. Al-Rafidain Dent. J. 10, 260–264 (2010).

Augustin, G. et al. Temperature changes during cortical bone drilling with a newly designed step drill and an internally cooled drill. Int. Orthop. 36, 1449–1456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-012-1491-z (2012).

Jochum, R. M. & Reichart, P. A. Influence of multiple use of Timedur-titanium cannon drills: thermal response and scanning electron microscopic findings. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 11, 139–143 (2000).

Alam, K., Mitrofanov, A. V. & Silberschmidt, V. V. Measurement of surface roughness in conventional and ultrasonically assisted bone drilling. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. 1, 312–320 (2009).

Maani, N., Farhang, K. & Hodaei, M. A model for the prediction of thermal response of bone in surgical drilling. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 6, 041005. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4026315 (2014).

Stephenson, D. A. & Agapiou, J. S. Calculation of main cutting edge forces and torque for drills with arbitrary point geometries. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 32, 521–538 (1992). 10.1016/0890–6955(92)90043-G.

Davidson, S. R. & James, D. F. Drilling in bone: modeling heat generation and temperature distribution. J. Biomech. Eng. 125, 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1535190 (2003).

Wills, D. J., Prasad, A., Gilmer, B. B. & Walsh, W. R. The thermal profile of self-tapping screws. Med. Eng. Phys. 100, 103754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2022.103754 (2022).

Wootton, R., Reeve, J. & Veall, N. The clinical measurement of skeletal blood flow. Clin. Sci. Mol. Med. 50, 261–268 (1976).

Augustin, G. et al. Cortical bone drilling and thermal osteonecrosis. Clin. Biomech. 27, 722–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.10.010 (2012).

Li, X., Zhu, W., Wang, J. & Deng, Y. Optimization of bone drilling process based on finite element analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 105, 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.07.125 (2016).

Sezek, S., Aksakal, B. & Karaca, F. Influence of drill parameters on bone temperature and necrosis: a FEM modelling and in vitro experiments. Comput. Mater. Sci. 60, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2012.03.051 (2012).

Alam, K., Mitrofanov, A. V. & Silberschmidt, V. V. Thermal analysis of orthogonal cutting of cortical bone using finite element simulations. Int. J. Exp. Comput. Biomech. 1, 236–251. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJECB.2010.035345 (2010).

Eswar, S. et al. Evaluation of cortical thickness and cortical thickness index in the proximal femur-CT, dual energy absorptiometry (DXA), trabecular bone score (TBS). PLoS One. 20, e0312420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0312420 (2025).

Hulme, P. A., Boyd, S. K. & Ferguson, S. J. Regional variation in vertebral bone morphology and its contribution to vertebral fracture strength. Bone 41, 946–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.019 (2007).

Zellner, A. A. A computed tomography–based morphometric analysis of thoracic pedicles in a European population. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-024-05171-3 (2024).

Lillie, E. M., Urban, J. E., Weaver, A. A., Powers, A. K. & Stitzel, J. D. Estimation of skull table thickness with clinical CT and validation with micro CT. J. Anat. 226, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12259 (2014).

Majed, A. et al. Cortical thickness analysis of the proximal humerus. Shoulder Elb. 11, 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758573217736744 (2019).

Tingart, M. J., Apreleva, M., von Stechow, D., Zurakowski, D. & Warner, J. J. The cortical thickness of the proximal humeral diaphysis predicts bone mineral density of the proximal humerus. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 85, 611–617. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.85b4.12843 (2003).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Assessment of thermal necrosis risk regions for different bone qualities as a function of drilling parameters. Comput. Methods PrograSms Biomed. 162, 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.05.018 (2018).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Evaluation of the parameters affecting bone temperature during drilling. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 55, 1949–1957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-017-1644-8 (2017).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Assessment of thermal osteonecrosis during bone drilling using a three-dimensional finite element model. Bioeng. (Basel). 11, 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11060592 (2024).

Remache, D., Semaan, M., Rossi, J. M., Pithioux, M. & Milan, J. L. Application of the Johnson-Cook plasticity model in the finite element simulations of the nanoindentation of the cortical bone. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 101, 103426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2019.103426 (2020).

Bachus, K. N., Rondina, M. T. & Hutchinson, D. T. The effects of drilling force on cortical temperatures and their duration. Med. Eng. Phys. 22, 685–691 (2000). -4533(01)00016 – 9.

Komanduri, R. & Hou, Z. B. Analysis of heat partition and temperature distribution in sliding systems. Wear 251, 925–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1648(01)00707-4 (2001).

Mellal, A., Wiskot, H. W., Botsis, J., Scherrer, S. S. & Belser, U. C. Stimulating effect of implant loading on surrounding bone: comparison of three numerical models and validation by in vivo data. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 15, 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01000.x (2004).

Eriksson, R. A. & Albrektsson, T. The effect of heat on bone regeneration: an experimental study in the rabbit using the bone growth chamber. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 42, 705–711 (1984). 10.1016/0278–2391(84)90417-8.

Shu, L. et al. A novel self-centring drill bit design for low-trauma bone drilling. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 154, 103568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2020.103568 (2020).

Bai, W. et al. Design of a self-centring drill bit for orthopaedic surgery: a systematic comparison of the drilling performance. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 123, 104727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104727 (2021).

Han Wang, U. & Satake, T. Enomoto Surgical oscillating saw blade to suppress forces in bone cutting. 71(1), 73–76 (2022).

Wang, H., Satake, U. & Enomoto, T. A novel flexible-structured saw blade for bone cutting: reducing ploughing and promoting chip evacuation. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 344, 119000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2025.119000 (2025).

Tool Engineer Editorial Department. All about Tools for Hole Processing 6–68 (Taiga Publication Co., Ltd., 1991).

Günay, M., Korkut, I., Aslan, E. & Seker, U. Investigation of the effect of rake angle on main cutting force. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 44, 953–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2004.07.007 (2005).

Ueda, T. et al. The effect of drill design elements on drilling characteristics when drilling bone. J. Biomech. Sci. Eng. 5, 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1299/jbse.5.399 (2010).

Sugita, N., Oshima, M., Kimura, K., Arai, G. & Arai, K. Novel drill bit with characteristic web shape for high efficiency and accuracy. CIRP Ann. 67(1), 69–72 (2018).

Matthews, L. S., Green, C. A. & Goldstein, S. A. The thermal effects of skeletal fixation pin insertion in bone. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 66, 1077–1083. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-198466070-00015 (1984).

Lavelle, C. & Wedgwood, D. Effect of internal irrigation on frictional heat generated from bone drilling. J. Oral Surg. 38, 499–503 (1980).

Haider, R., Watzek, G. & Plenk, H. Effect of drill cooling and bone structure on IMZ implant fixation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 8, 83–91 (1993).

Benington, I. C., Biagioni, P. A., Briggs, J., Shearidan, S. & Lamey, P. J. Thermal changes observed at implant sites during internal and external irrigation. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 13, 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130309.x (2002).

Shakouri, E., Haghighi Hassanalideh, H. & Gholampour, S. Experimental investigation of temperature rise in bone drilling with cooling: A comparison between modes of without cooling, internal gas cooling, and external liquid cooling. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 232, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954411917742944 (2018).

Abdul-Rashid, M. L., Tan, H. L. & Pancharatnam, D. Assessment of coolant delivery techniques for irrigation during bone drilling: a cadaveric observation. Malays Orthop. J. 14, 206–207. https://doi.org/10.5704/MOJ.2011.037 (2020).

Strbac, G. D. et al. Thermal effects of a combined irrigation method during implant site drilling. A standardized in vitro study using a bovine rib model. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 25, 665–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12032 (2014).

Han, Y., Cai, C., Lv, Q., Song, Y. & Zhang, Q. Effect of process parameters on the temperature changes during robotic bone drilling. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 236, 1129–1138. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544119221106825 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by E-Da Hospital (grant numbers EDAHI-113003 and EDAHP-113027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Y.-C.C.; Methodology, Software, Data acquisition and Curation, H.-Y.H. and Y.-Y.H.; Conceptualisation and supervision, Y.-K.T. and C.-Y.Y; Conceptualisation and Experiments, Y.-H.K; Software and formal analysis, C.-K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, YC., Hsiao, HY., Tu, YK. et al. Heat reduction during bone drilling using a two-stage drilling strategy. Sci Rep 15, 42344 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26395-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26395-1