Abstract

Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) bars and Unsaturated Polyester resin Concrete (UPC) offer superior corrosion resistance, making them viable alternatives to steel bars and traditional concrete in water-related projects. When both materials function as load-bearing components in water environment engineering, the performance of their bonding properties is of critical importance. This study examines the bond properties of GFRP bars-UPC under various aging conditions by establishing water environments at temperatures of 25 °C, 40 °C, and 60 °C. Central pull-out specimens of GFRP bars-UPC were subjected to these environments to evaluate their bond strength and bond-slip curves at various aging stages. The study reveals that the bond strength of GFRP bars-UPC diminishes as temperature and aging duration increase. Additionally, the relative slip values and residual bond stresses of aged specimens are lower compared to unaged specimens. The MBPE and continuous curve models accurately represent the bond-slip behavior of aging GFRP bars-UPC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reinforced concrete structures are widely used in water-related engineering projects. However, long-term exposure to aquatic environments frequently leads to corrosion of the embedded steel reinforcement, which in turn induces concrete cover deterioration and spalling1,2,3. This corrosion leads to structural damage, significantly impacting durability and resulting in considerable economic loss and safety risks. To address this issue, engineers frequently apply anti-corrosion measures to rebars, concrete, or structures, including epoxy coating or galvanization of rebars, adding corrosion inhibitors to concrete, or applying protective coatings to the water-facing surfaces of structures4,5. However, these methods often suffer from drawbacks such as complexity, poor effectiveness, and high costs. To fundamentally resolve corrosion issues in wet environments, researchers are increasingly exploring the use of corrosion-resistant reinforcements and concrete to replace traditional rebar and ordinary concrete6,7.

Glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars, composed of continuous fibers for load-bearing and resin as the matrix, provide benefits including corrosion resistance, high tensile strength, lightweight characteristics, insulation, and electromagnetic wave transparency8,9,10. Polymer concrete (PC) offers advantages over conventional concrete, including increased strength, reduced curing time, and improved corrosion resistance, leading to its widespread use in engineering projects11,12. There are various types of resins available, among which unsaturated polyester resin is particularly cost-effective, especially the unsaturated polyester resin concrete (UPC)13. Although FRP bars exhibit excellent durability, their mechanical properties and bond strength with concrete can deteriorate over time when exposed to aqueous environments in combination with ordinary concrete. This deterioration is primarily caused by the alkaline environment of the pore solution in ordinary concrete, which negatively impacts the performance of FRP bars14,15,16.Therefore, in water-related projects, the use of FRP bars and UPC as substitutes for steel reinforcement and conventional concrete, respectively, represents a viable and effective solution.

Researchers have extensively analyzed the bond performance of fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) bars with various concrete types, including ordinary17, recycled18,19,20,21, lightweight self-compacting22, air-entrained23, coral24,25, ultra-high performance26,27,28, and seawater sea-sand concrete29,30. On this basis, constitutive models describing the bond relationship between FRP bars and ordinary concrete have been established31. The bond behavior between FRP bars and concrete in humid aquatic environments requires considerable attention when using FRP-reinforced concrete structures32,33,34,35,36. For instance, Lu et al.37 investigated the bond performance between basalt fiber reinforced polymer (BFRP) bars and concrete with fly ash, concluding that the bond strength retention was about 48.0% after 50 years of seawater immersion. Saqib et al.38 examined the bond performance of BFRP bars with high-strength concrete in erosive environments by submerging pull-out specimens in alkaline and seawater solutions for three months. The study found that bond strength decreased post-immersion, with retention rates of 86% in alkaline solution and 82% in seawater. Altalmas et al.39 found that after 90 days of water exposure, the bond strength decreased by 25% for BFRP bars and 17% for GFRP bars when embedded in concrete. Discrepancies in bond durability results among different studies may be attributed to variations in bar properties used in each investigation. Dong et al.40 projected that over a 50-year design service life, the bond strength retention between BFRP bars and seawater sea-sand concrete would vary from 47 to 83% under various environmental conditions. Additionally, Belarbi et al.Research by41 demonstrated that environmental conditions, including freeze–thaw cycles, elevated temperatures (60 °C), and deicing salt solutions, notably diminished the bond strength between FRP bars and concrete.

Although FRP bars and different concrete types have been extensively researched, investigations into the bond performance of FRP bars with UPC are still scarce. Prior studies on the bond performance of steel rebars with UPC have shown notably greater bond strength than that of conventional concrete. For instance, Orsolya et al.42 found that polymer concrete significantly enhances the bond strength with steel bars compared to conventional concrete. Smooth steel bars in polymer concrete exhibit over ten times the bond strength of those in ordinary concrete, while ribbed steel bars need only a 40-mm bonding length. Douba et al.43 proposed that the incorporation of aluminum nanoparticles can enhance the bond strength between polymer concrete and steel by influencing the epoxy resin curing process. Li et al.44 examined the influence of bar diameter, type, surface morphology, and concrete cover thickness on the bond performance between FRP bars and UPC.

This study examines the bonding characteristics between GFRP bars and UPC under different aging conditions (25℃, 40℃, and 60℃) in a water environment. GFRP bars and UPC center drawing specimens were subjected to immersion in an aging water environment for different durations to analyze their bonding properties.

Experimental overview

Experimental materials

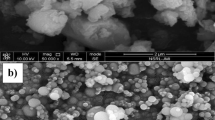

The raw materials and mix proportions for the UPC in this experiment matched those detailed in the authors’ prior study44. The GFRP bars are composed of vinyl resin-based reinforcement manufactured by Shandong Sford Industrial Co., LTD. The reinforcement has a diameter of 10 mm and exhibits a measured tensile strength of 979.76 MPa, along with an elastic modulus of 55.54GPa. Additionally, the surface of the reinforcement is ribbed with ribs spaced at intervals of 9 mm, featuring a rib width of 1 mm and a depth of 0.5 mm. The specific reinforcement utilized is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Specimen preparation

The specimens, intended for aging in a constant-temperature water bath, were sized at 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm to fit the experimental equipment, as illustrated in Fig. 2. To ensure precise analysis of bond strength degradation between GFRP bars and UPC, the specimen ends were fully encased in PVC pipes and sealed with hot-melt adhesive to prevent water ingress, which could influence the results. The bond length was established as 50 mm, equivalent to five times the bar diameter. Thirty pull-out specimens were prepared.

Aging conditions

This experiment utilized a constant-temperature water bath to simulate the aging environment, as shown in Fig. 3. Tap water was added to the water bath box, and temperatures were adjusted to 25 °C, 40 °C, and 60 °C. The specimens were immersed in the water, and pull-out tests were conducted at aging durations of 60, 120, and 180 days, comparing the results with those of unaged control specimens. During aging, the water bath box was sealed with plastic film to minimize water vapor and temperature loss.

Test procedure

The pull-out tests utilized a WAW-1000D electro-hydraulic servo universal testing machine. Two displacement meters, shown in Fig. 4, were used to measure the relative slip between the GFRP bars and UPC. Following preparation, tests were performed at a loading rate of 1 mm/min, as outlined in CSA S807 19.

Results and analysis

The failure mode observed in the central tensile pull-out test for GFRP bars with UPC was characterized by reinforcement dislodgement.

In this study, it is assumed that the adhesive stress is uniformly distributed throughout the bonding section. Therefore, the bond strength was calculated using formula 1 and the corresponding experimental results are presented in Table 1. The nomenclature for specimens in the table follows a format of temperature combined with aging period, such as T25-60d indicating an aging duration of 60 days at a temperature of 25℃ in a water bath. The control group represents specimens without undergoing accelerated aging.

The bond strength (MPa) is τ, P determined by the load magnitude (N), D is the bar diameter (mm), and L is the bond length (mm).

Effect of aging temperature on bond strength

The bond strength retention rate between GFRP bars and UPC at different temperatures is illustrated in Fig. 5. The graph indicates that bond strength consistently diminishes with rising temperatures. Following a 60-day aging period, the specimens demonstrated bond strength retention rates of 102.3%, 100.4%, and 98.6% at temperatures of 25℃, 40℃, and 60℃ respectively compared to non-aged specimens. The aged specimens demonstrated greater bond strength compared to the non-aged ones. The increased bond strength between GFRP bars and UPC is due to the greater expansion deformation of GFRP bars compared to UPC during temperature changes and water absorption in certain aging conditions, leading to a tighter bond. Similar experimental findings were also reported by Mohamed et al.45. After 120 days of aging in water at 25℃, 40℃, and 60℃, the bond strength retention rates are approximately 98.1%, 96.3%, and 94.7%, respectively. Subsequently, after an aging period of 180 days under similar conditions, the retention rates decrease to values around 96.4%, 94.2%, and 92.2% for temperatures of 25℃,40℃, and 60℃ respectively. As temperature rises, the softening and degradation of the resin in both GFRP bars and UPC are accelerated, resulting in reduced strength and stiffness. This deterioration negatively impacts the interfacial bond between the two materials, thereby further weakening the overall bond strength.

Effect of aging duration on bond strength

Figure 6 illustrates the variation in bond strength retention rate of GFRP bar -UPC over different aging periods. The graph demonstrates a slight increase in bond strength within an aging period of 0 to 60 days when exposed to temperatures of both 25℃ and 40℃, while under other aging conditions, the bond strength gradually decreases with increasing duration. At 25℃, the bond strength retention rates between GFRP bars and UPC after 60, 120, and 180 days are approximately 102.3%, 98.1%, and 96.4% of the unaged specimens, respectively. In a water environment with an aging temperature of 40℃, the retention rates of bond strength after 60d, 120d, and 180d are recorded as 100.4%, 96.3%, and 94.2% respectively. In a 60℃ water environment, the bond strength between GFRP bars and UPC progressively decreased as aging time increased. The retention rates of bond strength after accelerated aging for 60d, 120d, and 180d are determined to be 98.6%, 94.7%, and 92.2% respectively due to progressive moisture accumulation in specimens over time resulting in increased erosion on both materials and their interface leading to diminished bond strength.

Effect of humid-heat aging on bond-slip behaviour

Figure 7 illustrates the bond-slip curves for representative specimens subjected to different aging environments. The bond-slip curves maintain their overall shape before and after aging, displaying three distinct stages: ascending, descending, and residual. During the initial loading stage, the bond stress increases rapidly while slip remains minimal. With increasing pull-out force, the bond-slip curve’s slope progressively diminishes. Upon attaining its maximum value, the bond-slip curve begins to decline during the pre-peak stage, referred to as the ascending segment. In this descending segment, there is a gradual decrease in bond stress accompanied by rapid relative slip incrementation. When reaching a certain extent of descent, slight fluctuations occur within a narrow range of bond stress values resulting in a sinusoidal decay shape resembling that of a sine wave-referred to as residual segment.

Figure 7 shows that aging leads to a decrease in both the relative slip associated with bond strength and the residual bond stress. To analyze these changes, the average relative slip values at peak bond strength and the average residual bond stresses for each test group are plotted in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively.

From Fig. 8, it is evident that the relative slip values at peak bond strength show considerable variation but generally exhibit a decline post-aging compared to unaged specimens. After 180 days of aging at 25 °C, 40 °C, and 60 °C, the average relative slip values decreased to 1.38 mm, 1.34 mm, and 1.21 mm, respectively, compared to the unaged specimen value of 1.62 mm. These findings are consistent with those reported by Ahmad et al.39 and Alaa et al.33. The aging-induced decrease in ductility of GFRP bars and UPC results in specimen failure at lower relative slip values.

Figure 9 demonstrates that aged specimens exhibit lower residual bond stress than unaged specimens. The erosive effects on the surface of GFRP bars and the GFRP-UPC interface during aging reduce frictional resistance, thereby decreasing residual bond stress.

Bond-slip constitutive model of GFRP bars-UPC interface after aging

Based on extensive experimental research and theoretical analysis, numerous scholars have developed bond constitutive relationships between reinforcing bars and conventional concrete. Prominent examples encompass the BPE model46, Malvar model47, MBPE model48, CMR model49, and continuous curve model50. The BPE model is designed to characterize the bond behavior between steel bars and concrete, but it is not applicable to FRP bars. The Malvar model, characterized by a higher number of fitting parameters and a more intricate formulation, is less frequently utilized. The CMR model fails to adequately address the constitutive relationship in the descending and residual sections, which restricts its practicality. The MBPE and continuous curve models are more commonly used to characterize the bond constitutive relationship between FRP bars and concrete. Key features of these two models are summarized below.

1. MBPE model

Cosenza et al.48 modified the BPE model and introduced a curve model that accurately represents the bond-slip characteristics of FRP bars and concrete. This model consists of three distinct sections: the ascending section, the descending section, and the residual section, as illustrated in Fig. 10. The mathematical expression for this model is as follows:

Here, τ and \(s\) denote the bond stress (MPa) and relative slip (mm), respectively; τ 1 and s1 signify the bond strength (MPa) and its corresponding slip (mm); τ 3 and s3 represent the residual section stress (MPa) and its associated slip (mm); α and p are test fitting parameters, determined by equating the areas under the ascending and descending sections of both the test and theoretical curves.

The MBPE model is notable for its straightforward design and limited fitting parameters. Despite the linear depiction of the model’s descending and residual segments not aligning with the test curve, its simplicity has enabled widespread use.

2. Continuous curve model

Gao et al.50 introduced a continuous curve model to overcome the limitations of discontinuous curves and inadequate fit with experimental data in the constitutive model of FRP bar and concrete. The model, depicted in Fig. 11, is defined by the following equation.

Ascending section,

Descending section ,

Residual section ,

There, τu is the bond strength (MPa); τr is the residual bond stress (MPa); su is the slip value corresponding to the bond strength (mm); sr represents the slip when the residual bond strength is just reached (mm).

The continuous curve model exhibits the following characteristics: a) It contains no fitting parameters; b) The constitutive relationship curve is continuous; c) The slope at the initial point of the ascending segment approaches infinity; d) The descending segment is a curve that closely aligns with the experimental curve, although the expression is complex; e) The residual segment is a horizontal straight line, which does not match the experimental curve.

The bond-slip relationship between FRP bars and ultra-performance concrete is typically developed by refining existing models using experimental data. To date, there has been a notable absence of comprehensive studies on the bond-slip constitutive relationship of FRP bars-UPC. As depicted in Fig. 7, the bond-slip curve of GFRP bars-UPC exhibits minimal changes before and after aging. This study evaluates the MBPE and continuous curve models against experimental curves obtained after aging at three different temperatures for 180 days, to determine their effectiveness in characterizing the bond-slip behavior of GFRP bars-UPC post-aging. The comparison of the curves generated by both models with the experimental data is illustrated in Fig. 12.

Figure 12 shows that the ascending segments of the test curve align closely with those of the two model curves. However, the linear descending segment of the MBPE model exhibits a marginally lower degree of congruence with the test curve when compared to the continuous curve model. Nevertheless, the simplicity of the MBPE model facilitates the derivation of an analytical solution. The residual section reveals notable differences between the curves of the two models and the experimental curves.

Conclusions

This study conducted pull-out tests on GFRP bar-UPC specimens after aging treatment. The primary research findings are summarized as follows:

1. Increasing the aging temperature accelerates the reduction in strength of GFRP bars and UPC, which directly impacts their interface bonding and subsequently decreases bond strength. Aged specimens exhibit greater bond strength compared to unaged ones. This is primarily due to the fact that, in certain aging environments, GFRP bars exhibit greater expansion deformation compared to UPC under conditions of temperature changes and water molecule absorption, leading to a tighter bond and thus higher bond strength.

2. The bond strength generally decreases with the increase in aging duration (with the exception of specimens aged at 25 °C and 40 °C for up to 60 days). This phenomenon results from the gradual water accumulation in the specimens over time, which enhances the erosion of the materials and their interface. As a result, the mechanical interlocking between the two materials is weakened, leading to decreased bond strength.

3. Prior to and following the aging process, the bond-slip curve of GFRP bars-UPC demonstrated minimal alterations, preserving its distinct ascending, descending, and residual segments. The MBPE model and the continuous curve model accurately represent both the ascending and descending segments of the bond-slip curve for aged GFRP bars-UPC.

4. After aging, the bond strength slip values between GFRP bars and UPC show greater variability, with aged specimens typically having lower values than unaged ones. This phenomenon is due to the reduced plasticity of GFRP bars and UPC following aging. Consequently, the specimens are more prone to damage with a smaller relative slip. The residual bond stress in most aged specimens decreases due to surface erosion of the GFRP bars and at their interface with UPC, resulting in diminished frictional forces.

Data availability

Some or all data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hu, Y. H. et al. A fluid-solid-chemical coupled fractal model for simulating concrete damage and reinforcement corrosion. Chem. Eng. J. 442, 136045 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Chloride distribution and steel corrosion in a concrete bridge after long-term exposure to natural marine environment. Materials 13(17), 3900 (2020).

Cui, Z. & Alipour, A. Concrete cover cracking and service life prediction of reinforced concrete structures in corrosive environments. Construct. Build. Mater. (2018).

Jiang, L., Huang, G., Xu, J., Zhu, Y. & Mo, L. Influence of chloride salt type on threshold level of reinforcement corrosion in simulated concrete pore solutions. Constr. Build. Mater. 30, 516–521 (2012).

Soriano, C. & Alfantazi, A. Corrosion behavior of galvanized steel due to typical soil organics. Constr. Build. Mater. 102, 904–912 (2016).

Ahmed, A., Guo, S., Zhang, Z., Shi, C. & Zhu, D. A review on durability of fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) bars reinforced seawater sea sand concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 256, 119484 (2020).

Zhou, W., Feng, P. & Yang, J.-Q. Advances in coral aggregate concrete and its combination with FRP: A state-of-the-art review. Adv. Struct. Eng. 24(6), 1161–1181 (2021).

Yanan, S., Zuquan, J., Xiaoying, Z. & Deju, Z. Experimental and molecular dynamics study on the deterioration mechanism of GFRP bars in distilled water and salt solution environments. J. Build. Eng. 60, 105224 (2022).

ACI 440.1R-15. Guide for the Design and Construction of Concrete Reinforced with FRP Bars. (American Concrete Institute, 2015).

Zhou, J., Chen, X. & Chen, S. Durability and service life prediction of GFRP bars embedded in concrete under acid environment. Nucl. Eng. Des. 241(10), 4095–4102 (2011).

Hashemi, M. J., Jamshidi, M. & Aghdam, J. H. Investigating fracture mechanics and flexural properties of unsaturated polyester polymer concrete (UP-PC). Constr. Build. Mater. 163, 767–775 (2018).

Yeon, K.-S., Choi, Y.-S., Kim, K.-K. & Yeon, J. H. Flexural fatigue life analysis of unsaturated polyester-methyl methacrylate polymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 140, 336–343 (2017).

Yang, G. et al. Unsaturated polyester resin concrete: A review. Construct. Build. Mater. 228, 116709 (2019).

Arczewska, P., Polak, M. A. & Penlidis, A. Degradation of glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars in concrete environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 293, 123451 (2021).

Hosseini, S.A. et al.. Bond behaviour of lap spliced GFRP bars in concrete members: A state-of-the-art review and design recommendations. Construct. Build. Mater. 411, 134714 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Long-term bond performance of fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) bars to concrete in marine environments: a comprehensive review. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 25(3) (2025).

Veljkovic, A., Carvelli, V., Haffke, M. M. & Pahn, M. Concrete cover effect on the bond of GFRP bar and concrete under static loading. Compos. Part B Eng. 124, 40–53 (2017).

Shengwei, L. et al. Experimental and theoretical study on bonding performance of FRP bars-Recycled aggregate concrete. Construct. Build. Mater. 361, 129614 (2022).

Liu, H. X., Yang, J. W. & Wang, X. Z. Bond behavior between BFRP bar and recycled aggregate concrete reinforced with basalt fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 135, 477–483 (2017).

Ma, Q. et al. Experimental investigation of bond performance between BFRP and different strength recycled-aggregate concrete. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 37(18), 2587–2607 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Experimental and theoretical study on bonding performance of FRP bars-Recycled aggregate concrete. Construct. Build. Mater. 361, 129614 (2022).

Mehany, S., Mohamed, H. M., El-Safty, A. & Benmokrane, B. Bond-dependent coefficient and cracking behavior of lightweight self-consolidating concrete (LWSCC) beams reinforced with glass- and basalt-FRP bars. Constr. Build. Mater. 329, 127130 (2022).

Solyom, S. et al. Bond of FRP bars in air-entrained concrete: Experimental and statistical study. Construct. Build. Mater. 300, 124193 (2021).

Yang, S. et al. Study on bond performance between FRP bars and seawater coral aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 173, 272–288 (2017).

Wen, Z., Peng, F., Hongwei, L. & Peizhao, Z. Bond behavior between GFRP bars and coral aggregate concrete. Compos. Struct. 306, 116567 (2023).

Xiao, J. et al. Research on the bond performance between glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars and ultra-high performance concrete(UHPC). J. Build. Eng. 98, 111340 (2024).

Ke, Lu. et al. Bond-slip and bond strength models for FRP bars embedded in ultra-high-performance concrete: A critical review. Structures 64, 106551 (2024).

Xiao, J. et al. Research on the bond performance between glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars and ultra-high performance concrete(UHPC). J. Build. Eng. 98, 111340 (2024).

Cui, Y. et al. Experimental and finite element study of bond behavior between seawater sea-sand alkali activated concrete and FRP bars. Construct. Build. Mater. 424, 135919 (2024).

Zhang, P.-F. et al. Bond strength prediction of FRP bars to seawater sea sand concrete based on ensemble learning models. Eng. Struct. 302, 117382 (2024).

Wu, L., Xu, X., Wang, H. & Yang, J.-Q. Experimental study on bond properties between GFRP bars and self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 320, 126186 (2022).

Yan, F. & Lin, Z. Bond durability assessment and long-term degradation prediction for GFRP bars to fiber-reinforced concrete under saline solutions. Compos. Struct. 161, 393–406 (2017).

Taha, A., Alnahhal, W. & Alnuaimi, N. Bond durability of basalt FRP bars to fiber reinforced concrete in a saline environment. Compos. Struct. 243, 112277 (2020).

Chang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, M., Zhou, Z. & Jinping, Ou. Bond durability and degradation mechanism of GFRP bars in seawater sea-sand concrete under the coupling effect of seawater immersion and sustained load. Constr. Build. Mater. 307, 124878 (2021).

Wu, L. et al. Investigation on bond durability of GFRP bar/engineered cementitious composite under alkaline-saline environments. J. Build. Eng. 77, 107343 (2023).

Machello, C. et al. FRP bar and concrete bond durability in seawater: A meta-analysis review on degradation process, effective parameters, and predictive models. Structures 62, 106231 (2024).

Zhongyu, L. et al. Bond durability of BFRP bars embedded in concrete with fly ash in aggressive environments. Compos. Struct. 271, 114121 (2021).

Hussain, S. et al. Bond performance of basalt FRP bar against aggressive environment in high-strength concrete with varying bar diameter and bond length. Construct. Build. Mater. 349, 128779 (2022).

Altalmas, A. et al. Bond degradation of basalt fiber-reinforced polymer (BFRP) bars exposed to accelerated aging conditions. Construct. Build. Mater. 81,162–171 (2015).

Zhi-Qiang, D. et al. Long-term bond durability of fiber-reinforced polymer bars embedded in seawater sea-sand concrete under ocean environments. J. Compos. Construct. 22(5) (2018).

Belarbi, A. & Wang, H. Bond durability of FRP bars embedded in fiber-reinforced concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 16(4), 371–380 (2012).

Orsolya, I. N., Eva, L. & Gyorgy, F. Bond of reinforcement in polymer concrete. Period. Polytech.-Civ. Eng. 58(2), 137–141 (2014).

Douba, A. et al. The significance of nanoparticles on bond strength of polymer concrete to steel. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 74, 77–85 (2017).

Wenchao, L. et al. Experimental study on the bond performance between fiber-reinforced polymer bar and unsaturated polyester resin concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 6676494 (2021).

Hassan, M., Benmokrane, B., ElSafty, A. & Fam, A. Bond durability of basalt-fiber-reinforced-polymer (BFRP) bars embedded in concrete in aggressive environments. Compos. B Eng. 106, 262–272 (2016).

Eligehausen, R. et al.. Local bond stress-slip relationships of deformed bars under generalized excitations. Eng. Res. Ctr. 83, 69–80 (1983).

Malvar L J. Bond stress-slip characteristics of FRP rebars. In Report TR-2013-SHR, Naval Facilities Engineering. (Service Control, Port Hueneme, 1994).

Cosenza, E. et al. Bond characteristics and anchorage length of FRP rebars. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advanced Composites Materials in Bridge Structures (El-Badry, M. Ed.) (1996).

Cosenza, E., Manfredi, G. & Realfonzo, R. Beravior and modeling of bond of FRP rebars to concrete. J. Compos. Construct. 1(2), 40–51 (1997).

Danying, G. & Brahim, B. Bonding mechanism and calculating method for embedded length of fiber reinforced polymer rebars in concrete. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2000(11), 70–78 (2000).

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province, grant number 2024TSGC0668.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Wenchao Li; methodology, Wenchao Li and Wenming Cao; software, Mingxin Liu; validation, Wenchao Li; formal analysis, Wenchao Li and Wenming Cao; investigation, Wenming Cao; resources, Yuzhao Jiao; data curation, Wenchao Li ; writing—original draft preparation, Wenchao Li ; writing—review and editing, Wenchao Li and Wenming Cao; supervision, Guangfa Zhou. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Cao, W., Liu, M. et al. Durability assessment of the bonding performance between GFRP rebars and UPC in aquatic environments. Sci Rep 15, 42250 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26419-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26419-w