Abstract

This study aimed to identify risk factors associated with corneal transplantation within five years among Thai patients with Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) and to evaluate whether isolated cataract surgery could defer the need for corneal transplantation. We retrospectively reviewed 900 patients (1,743 eyes) at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital between January 2017 and June 2023. Associations were assessed using logistic regression. Significant predictors of transplantation included advanced disease stage (Adamis’ grade ≥ 2; odds ratio [OR] = 6.40), reduced endothelial cell density (ECD ≤ 1600 cells/mm²; OR = 5.30), increased central corneal thickness (CCT ≥ 590 μm; OR = 2.64), and worse baseline best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA ≥ 0.3 logMAR; OR = 2.02). Among 274 phakic eyes undergoing isolated cataract surgery, preoperative ECD ≤ 1700 cells/mm² or CCT ≥ 550 μm were associated with postoperative progression. These thresholds should be regarded as exploratory, particularly in the cataract subgroup where event numbers were small and follow-up was short. Nevertheless, our findings may help improve risk stratification, guide preoperative counseling, and support efficient donor allocation in regions facing chronic shortages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) is a progressive disorder of the corneal endothelium marked by progressive cell loss and the guttae formation, leading to edema, subepithelial fibrosis, and eventual visual impairment1. It is shaped by genetic predispositions, oxidative stress, and environmental factors1. Clinically, FECD presents in two main forms: early-onset and late-onset, with the latter being more prevalent, typically manifesting in the fifth decade1,2. Prevalence varies by ethnicity and region, from 0.08% to 21.6% globally, and is higher in Caucasians than in Asians1,3,4,5. Among Asians, the prevalence is higher in Chinese Singaporeans (6.7%) than in Japanese (3.3–4.1%) and Indian populations (0.08%).4,6,7,8 In Thailand, genetic studies have demonstrated unique trinucleotide repeat (TNR) expansions in the transcription factor 4 (TCF4) gene, suggesting ethnicity-specific differences that distinguish Thai patients from other Asian and global populations9.

Corneal transplantation, including penetrating keratoplasty (PK) and endothelial keratoplasty (EK), remains the definitive treatment for advanced FECD10. Recent advancements in EK, particularly Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) and Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK), have shifted surgical trends away from PK due to EK’s superior outcomes, such as faster recovery and reduced complications10,11. Despite this, non-medical factors, such as limited surgical expertise and donor shortages, may affect the choice of surgical techniques and timing1.

Key clinical indicators for transplantation include deteriorating visual acuity, increased central corneal thickness (CCT), and worsening symptoms11. In Thailand, longer donor waiting times, averaging 3–4 years, often delaying interventions until advanced disease stages3. Understanding the risk factors influencing corneal transplantation within specific timeframes can optimize patient counseling and resource allocation, particularly in regions with prolonged waiting periods.

This study addresses the question: “What is the risk of corneal transplantation within the next five years?” defined as keratoplasty within five years of first documentation of FECD at our institution. This is particularly relevant in Thailand, where donor waiting times average 3–4 years. Early identification of high-risk patients can guide donor registration and prognosis discussions, providing clarity about outcomes and surgery timing. By analyzing key predictors, this research aims to optimize decision-making and improve FECD patient care in Thailand.

Conservative management, including cataract surgery or medical interventions, can delay transplantation in early FECD. Previous studies indicate cataract surgery alone can improve vision and defer corneal transplantation in low-risk patients, while high-risk patients may benefit more from combined procedures12,13. However, the long-term outcomes of such approaches remain understudied in Thai patients.

This study aims to investigate risk factors associated with corneal transplantation within five years and evaluate the impact of conservative management, particularly cataract surgery, in delaying surgical interventions. By identifying key predictors and management outcomes, this research seeks to enhance clinical decision-making, optimize donor registration practices, and improve care for FECD patients in Thailand.

Materials and methods

This single-center, retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Excellence Center for Cornea and Limbal Stem Cell Transplantation, Department of Ophthalmology, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by The Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand (IRB No. 0590/66; Certificate of Approval No. 1238/2023). The requirement for informed consent was waived by The Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of anonymized data.

Study population and data collection

Patients with a definite diagnosis of FECD who presented to the outpatient clinic between January 2017 and June 2023 were included. Exclusion criteria comprised: (i) prior keratoplasty; (ii) chronic use of topical Rho-kinase (ROCK) inhibitors; and (iii) any intraocular surgery or ocular laser performed before baseline, as surgical details were inconsistently available. Intraocular surgeries performed after enrollment (e.g., cataract or glaucoma procedures) were recorded as follow-up events for risk-factor analyses and are referred to in the Results as “interim intraocular surgery”. Data were obtained retrospectively from electronic medical records (EMR), the Thai Red Cross Eye Bank (TRCEB), and the Chulalongkorn Corneal Registration System (CUCRS).

Baseline demographics and clinical parameters were recorded at the first presentation, and follow-up visits were reviewed over five years. Collected data included demographics (age, gender, systemic comorbidities), clinical parameters (best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure (IOP), central corneal thickness (CCT), endothelial cell density (ECD)), and surgical interventions (types of corneal transplantation and combined surgeries). Anterior chamber depth (ACD) and axial length (AXL) were not routinely measured at baseline visits and were therefore unavailable for the overall analysis. Disease severity was graded using Adamis’ staging system14 based on slit lamp findings, pachymetry, and specular microscopy.

For the 5-year outcome analysis, we included only eyes with ≥ 5 years of follow-up from baseline. Eligible eyes either underwent keratoplasty within 5 years or completed 5 years of follow-up without surgery. Eyes with shorter follow-up or still awaiting donor allocation were excluded, as donor registration in this setting does not uniformly represent surgical indication or readiness. Patients are often preemptively registered because of prolonged donor waiting times, and surgical scheduling may subsequently be deferred or cancelled if corneal status remains stable. Excluding these eyes minimized potential misclassification and ensured accurate outcome assessment. All predictors were defined from baseline parameters at first presentation. Further details regarding operational definitions are available in our prior publication15.

Eligibility for corneal transplantation was determined by clinical assessment and logistical criteria, including donor availability, surgical readiness, patient willingness. Eyes indicated for keratoplasty were categorized into two groups: those that underwent corneal transplantation (“transplanted group”) and those in whom surgery was postponed or considered unnecessary (“nontransplanted group”). Comparative analyses between these two groups were then performed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics and clinical data. Parametric methods were justified by the large sample size based on the Central Limit Theorem, which supports approximate normality for statistical inference in sufficiently large datasets16. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate associations between risk factors and corneal transplantation within five years. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF) for clinically relevant variables (e.g., CCT, ECD, BCVA, and Age). All VIF values were below 1.2, indicating no significant collinearity. A time-to-event analysis was not performed because inconsistent documentation of timing of surgical indication and donor-related delays could violate proportional hazards assumptions. A fixed 5-year outcome framework was adopted to maintain analytic consistency and reduce bias from non-clinical factors. Eyes with unmeasurable or unreliable ECD due to confluent guttae or stromal edema were excluded from regression analyses but retained in descriptive summaries. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 900 patients (1,743 eyes) were analyzed, with a mean age of 63.8 ± 10.5 years. Most patients (77.2%) were female, and 67.0% resided in Bangkok. Systemic comorbidities included hypertension (38.6%) and diabetes mellitus (17.4%). Additional demographic and baseline clinical details are available in our previous publication15.

Factors associated with corneal transplantation within 5 years

A total of 1,198 eyes were included in the risk-factor analysis (215 underwent keratoplasty within 5 years and 983 completed 5-year follow-up without surgery). The remaining 545 eyes were excluded because they did not complete 5 years of follow-up or were still awaiting donor allocation at the end of the study period.

Among 1,198 eyes, several clinical parameters showed significant differences between the two groups. Interim intraocular surgery was more prevalent in the transplanted group (34.0%) than in the nontransplanted group (29.6%, p = 0.001). Mean BCVA at presentation was significantly worse in the transplanted group (0.66 LogMAR) compared to the nontransplanted group (0.24 LogMAR, p < 0.001). ECD was lower (1,406.9 cells/mm² vs. 2,182.3 cells/mm², p < 0.001), while CCT was higher in the transplanted group (618.5 μm vs. 556.8 μm, p < 0.001). Additionally, 55.3% of eyes in the transplanted group were classified as Adamis’ grade 2 or higher, compared to only 7.5% in the nontransplanted group (p < 0.001). For detailed comparisons, see Table 1.

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with Youden’s index was used to identify optimal thresholds for BCVA, ECD, and CCT. To enhance clinical applicability, the derived values were rounded to practical thresholds: BCVA ≥ 0.3 logMAR, ECD ≤ 1600 cells/mm², and CCT ≥ 590 μm These cut-offs showed moderate discriminative performance (AUC: BCVA 0.73, ECD 0.77, CCT 0.71), with sensitivities of 63–76% and specificities of 71–84% (Supplementary Table S1).

Univariable regression analysis showed significant associations between multiple factors and corneal transplantation. These included BCVA ≥ 0.3 logMAR (OR = 7.57, p < 0.001), Adamis’ grade ≥ 2 (OR = 15.22, p < 0.001), ECD ≤ 1600 cells/mm² (OR = 11.34, p < 0.001), and CCT ≥ 590 μm (OR = 5.97, p < 0.001). Female gender was protective in univariable analysis (OR = 0.64, p = 0.001). In the multivariable analysis, BCVA ≥ 0.3 logMAR (OR = 2.02, p = 0.033), Adamis’ grade ≥ 2 (OR = 6.40, p < 0.001), ECD ≤ 1600 cells/mm² (OR = 5.30, p < 0.001), and CCT ≥ 590 μm (OR = 2.64, p = 0.005) remained independently associated with corneal transplantation, while female gender was no longer statistically significant (OR = 1.10, p = 0.791). For a complete summary of risk factors, refer to Table 2.

Isolated cataract surgery

Among phakic eyes not undergoing transplantation, 20.4% (n = 274) underwent cataract surgery to improve vision. Table 3 presents the preoperative and postoperative characteristics of this cohort.

Analysis of isolated cataract surgery: disease progression based on Adamis’ grade

Progression based on Adamis’ grade occurred in 16 of 274 eyes (6.3%) within one year postoperatively. To ensure accurate associations, only eyes with both preoperative and postoperative data for ECD (n = 219) and CCT (n = 232) were included. ROC curve analysis was used to determine optimal preoperative thresholds associated with progression. The derived cut-offs were rounded to clinically practical values of ECD ≤ 1700 cells/mm² and CCT ≥ 550 μm. ROC analysis in this subgroup showed modest performance (Supplementary Table S2). Fisher’s exact test confirmed higher progression risk in eyes with preoperative ECD ≤ 1700 cells/mm² (OR = 18.77, p < 0.001) or CCT ≥ 550 (OR = 3.50, p = 0.040). For further details, refer to Table 4.

Discussion

This study provides essential insights into factors associated with corneal transplantation in FECD and contributes to risk stratification in practice. Beyond confirming known indicators (CCT, BCVA, clinical grade), our findings provide Thai-specific, ROC-derived thresholds from a large FECD cohort in Southeast Asia. We also demonstrate context-specific differences between thresholds for overall transplant risk versus post-cataract progression, which is relevant in settings with prolonged donor wait times. Consistent with previous findings by Goldberg et al. which was a retrospective study analyzing clinical records, we identified BCVA, advanced disease grade, and increased CCT as strong predictors of transplantation. However, while a mean BCVA of 20/60 was reported in transplanted patients, our findings suggest BCVA ≥ 0.3 (20/40), as a predictive cutoff, indicating possible differences in surgical thresholds17. Although BCVA was independently associated with transplantation, it is a non-specific marker influenced by cataract and corneal pathology and should be interpreted alongside corneal parameters rather than as a stand-alone predictor.

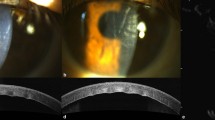

Our study found a mean CCT of 618.5 μm in the transplanted group vs. 556.8 μm in the nontransplanted group, aligning with previous report that surgical patients had greater CCT (635 μm vs. 592 μm, p < 0.001)17. In regression analysis, CCT ≥ 590 μm was independently associated with transplantation. ECD was significantly lower in the transplanted group compared with the nontransplanted group (1406.9 vs. 2182.3 cells/mm²). Multivariable regression analysis further identified ECD ≤ 1600 cells/mm² as predictive within five years, underscoring its importance in monitoring to enhance clinical decision. New technologies, such as Scheimpflug tomography, corneal densitometry, and ultrahigh-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), have been used to detect early corneal endothelium dysfunction by identifying subclinical corneal edema and irregularities in the Descemet membrane18,19. Integrating these new parameters could significantly enhance predictive factors for transplantation.

While female gender appeared protective in univariable analysis, it was not significant in multivariable models. In contrast, a previous study found male sex associated with higher transplantation rates17. These differences may stem from population-specific variations in disease progression or differences in access to treatment. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension were common in our cohort but not predictive after regression, consistent with prior inconclusive findings20,21. Future research comparing systemic comorbidities across populations may provide further insight into their role in FECD progression and management.

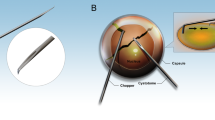

In our study, cataracts played a major role in contributing to vision loss, aligning with prior studies supporting its role as a standalone intervention in select cases12,22. However, preoperative risk stratification remains essential, as advanced imaging can detect subclinical edema and predict post-cataract surgery decompensation risk23,24. Our findings suggest that ECD ≤ 1700 cells/mm² and CCT ≥ 550 μm before cataract surgery predict higher progression risk, whereas previous studies have suggested lower thresholds, ECD < 1000 cells/mm² and CCT > 640 μm12,25,26. Seitzman et al. further noted that patients with CCT between 600 and 640 μm could undergo cataract surgery cautiously if no epithelial edema was present, while those with CCT > 640 μm were more likely to require keratoplasty26.

Our cut-off values associated with progression differ by management context. In the overall FECD cohort, ECD ≤ 1600 cells/mm² and CCT ≥ 590 μm predicted transplantation within five years. In contrast, after isolated cataract surgery, higher ECD (≤ 1700 cells/mm²) and lower CCT (≥ 550 μm) thresholds predicted progression. This discrepancy likely reflects phacoemulsification-related endothelial cell loss, together with inter-patient variability in susceptibility. Surgical decision-making may also have influenced subgroup definitions. In our setting, long donor waiting times limited the use of staged keratoplasty (cataract surgery followed later by transplant), leading to a higher tendency to perform triple procedures in higher-risk eyes. Together, these findings emphasize the importance of context-specific thresholds and tailored preoperative evaluation, particularly in borderline candidates.

The differences between our findings and prior reports may reflect variations in surgical techniques, postoperative management, and baseline characteristics. While pachymetry is widely used for risk assessment, it may not fully predict decompensation risk. Corneal tomography could enhance risk stratification by detecting subclinical edema, particularly for patients in the 600–640 μm range23,27. Prospective studies incorporating ocular biometry (e.g., ACD and AXL) may further refine risk stratification in this setting.

The decision between isolated phacoemulsification, sequential EK, or combined procedures depends on disease severity, donor availability, and patient factors13,22,28,29. In Thailand, long donor wait times necessitate careful counseling to balance delaying keratoplasty when appropriate while ensuring timely intervention for advanced cases. Cataract surgery should be considered integral to FECD management, offering a viable option for patients not yet requiring endothelial transplantation.

Finally, donor shortage remains a major barrier in Thailand as well as other developing countries30,31. A global survey reported 12.7 million individuals await corneal transplantation, with one available graft for every 70 patients in need30. While early donor registration may help, over-registration can strain the eye banking system. Refining allocation criteria using predictive models could help prioritize high-risk patients, optimize resource distribution, and reduce waiting times3,30. Patient preferences and socioeconomic factors also influence surgical decisions and should be considered in future planning.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective design introduces potential bias from missing data and variability in documentation. Restricting analysis to eyes with complete 5-year follow-up ensured consistency but may have underrepresented some subgroups. The timing of surgical indication and transplantation was inconsistently documented, and donor allocation delays often influenced surgery scheduling. Therefore, a survival analysis was not performed, as these factors could violate proportional hazards assumptions and bias time-to-event estimates. The fixed 5-year outcome framework was used to maintain analytic consistency and minimize bias from such non-clinical factors. The findings are specific to a Southeast Asian population and may not be fully generalizable, as surgical decision-making and donor availability vary across healthcare systems. Exclusion of eyes with unmeasurable ECD created stricter analytic criteria and may have underestimated risk in advanced disease, so the derived cut-offs apply mainly to eyes with measurable ECD. Cataract grading was unavailable, meaning BCVA may reflect both corneal and lenticular contributions, and reliance on clinical judgment may have introduced selection bias. Excluding eyes awaiting donor allocation may also have introduced selection bias, though this criterion was applied to avoid misclassification of surgical outcomes. ROC-derived thresholds showed only moderate discriminative performance and should therefore be regarded as exploratory. The cataract subgroup analysis was limited by the small number of progression events (n = 16) and the relatively short one-year follow-up, reducing statistical power and long-term generalizability. Finally, ocular biometric parameters such as ACD and AXL were not routinely available, representing another area for future study.

Conclusion

This study found that advanced Adamis’ grade, lower ECD (≤ 1600 cells/mm²), higher CCT (≥ 590 μm), and worse baseline BCVA (≥ 0.3 logMAR) were associated with corneal transplantation in Thai FECD patients. In appropriately selected early-stage cases, cataract surgery may defer transplantation, though patients with ECD ≤ 1700 cells/mm² and CCT ≥ 550 μm were at higher risk of disease progression. These thresholds should be regarded as exploratory, particularly given the study’s retrospective design and subgroup limitations. Long donor waiting times remain a major challenge, necessitating improved risk stratification and donor allocation strategies. Optimizing diagnostic tools and resource distribution could enhance patient care and surgical outcomes, ultimately improving FECD management in Thailand and beyond.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ong Tone, S. et al. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: the vicious cycle of Fuchs pathogenesis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 80, 100863 (2021).

Hamill, C. E., Schmedt, T. & Jurkunas, U. Fuchs endothelial cornea dystrophy: A review of the genetics behind disease development. Semin Ophthalmol. 28 (5–6), 281–286 (2013).

Soh, Y. Q., Kocaba, V., Pinto, M. & Mehta, J. S. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy and corneal endothelial diseases: East Meets West. Eye 34 (3), 427–441 (2020).

Das, A. & Chaurasia, S. Clinical profile and demographic distribution of fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy: an electronic medical record–driven big data analytics from an eye care network in India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 70 (7), 2415 (2022).

Eghrari, A. O. et al. Prevalence and severity of Fuchs corneal dystrophy in Tangier Island. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 153 (6), 1067–1072 (2012).

Kitagawa, K. et al. Prevalence of primary cornea guttata and morphology of corneal endothelium in aging Japanese and Singaporean subjects. Ophthalmic Res. 34 (3), 135–138 (2002).

Higa, A. Prevalence of and risk factors for cornea guttata in a Population-Based study in a Southwestern Island of japan: the Kumejima study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 129 (3), 332 (2011).

Nagaki, Y., Hayasaka, S., Kitagawa, K. & Yamamoto, S. Primary cornea guttata in Japanese patients with cataract: specular microscopic observations. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 40 (4), 520–525 (1996).

Okumura, N. et al. Trinucleotide repeat expansion in the transcription factor 4 (TCF4) gene in Thai patients with Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Eye 34 (5), 880–885 (2020).

Matthaei, M. et al. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: Clinical, Genetic, Pathophysiologic, and therapeutic aspects. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 5 (1), 151–175 (2019).

Kocaba, V., Oellerich, S. & Melles, G. R. J. Toward a paradigm shift in the therapeutic approach to Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 139 (4), 431 (2021).

Moshirfar, M., Huynh, R. & Ellis, J. H. Cataract surgery and intraocular lens placement in patients with Fuchs corneal dystrophy: a review of the current literature. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 33 (1), 21–27 (2022).

Romano, V. et al. Combined or sequential DMEK in cases of cataract and Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) [Internet]. 2024 Feb [cited 2024 Aug 1];102(1). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.15691

Adamis, A. P., Filatov, V., Tripathi, B. J. & Tripathi, R. C. Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy of the cornea. Surv. Ophthalmol. 38 (2), 149–168 (1993).

Wannapanich, T., Puangsricharern, V., Satitpitakul, V., Kittipibul, T. & Suphapeetiporn, K. Demographic profile and clinical characteristics of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy in Thai patients: A retrospective cohort in a tertiary referral center. Clin. Ophthalmol. 19, 45–57 (2025).

Rosner, B. Fundamentals of biostatistics. 8th edition. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. p 927 (2016).

Goldberg, R., Raza, S., Walford, E., Feuer, W. & Goldberg, J. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: clinical characteristics of surgical and nonsurgical patients. Clin. Ophthalmol. 8, 1761–1766 (2014).

Han, S. B., Liu, Y. C., Liu, C. & Mehta, J. S. Applications of imaging technologies in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: A narrative literature review. Bioengineering 11 (3), 271 (2024).

Augustin, V. A. et al. Scheimpflug versus optical coherence tomography to detect subclinical corneal edema in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Cornea 41 (11), 1378–1385 (2022).

Zwingelberg, S. B. et al. The influence of obesity, diabetes mellitus and smoking on Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD). Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 11596 (2024).

Nealon, C. L. et al. Association between Fuchs endothelial corneal Dystrophy, diabetes Mellitus, and Multimorbidity. Cornea 42 (9), 1140–1149 (2023).

Ali, M., Cho, K. & Srikumaran, D. Fuchs dystrophy and cataract: Diagnosis, evaluation and treatment. Ophthalmol. Ther. 12 (2), 691–704 (2023).

Arnalich-Montiel, F., Mingo-Botín, D. & De Arriba-Palomero, P. Preoperative risk assessment for progression to Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty following cataract surgery in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 208, 76–86 (2019).

Van Cleynenbreugel, H., Remeijer, L. & Hillenaar, T. Cataract surgery in patients with fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy. Ophthalmology 121 (2), 445–453 (2014).

Yamazoe, K. et al. Outcomes of cataract surgery in eyes with a low corneal endothelial cell density. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 37 (12), 2130–2136 (2011).

Seitzman, G. D., Gottsch, J. D. & Stark, W. J. Cataract surgery in patients with fuchs’ corneal dystrophy. Ophthalmology 112 (3), 441–446 (2005).

Sun, S. Y., Wacker, K., Baratz, K. H. & Patel, S. V. Determining subclinical edema in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: revised classification using Scheimpflug tomography for preoperative assessment. Ophthalmology 126 (2), 195–204 (2019).

Mukhija, R., Henein, C., Lee, H., Phee, J. & Nanavaty, M. Outcomes of descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty performed in combination with, before, or after cataract surgery in fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy: A review of the literature and meta-analysis. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 71 (3), 707 (2023).

Chou, W. Y., Kuo, Y. S. & Lin, P. Y. Cataract surgery in patients with fuchs’ dystrophy and corneal decompensation indicated for descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 8500 (2022).

Gain, P. et al. Global survey of corneal transplantation and eye banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 134 (2), 167 (2016).

Tan, D. T., Dart, J. K., Holland, E. J. & Kinoshita, S. Corneal transplantation. Lancet 379 (9827), 1749–1761 (2012).

Acknowledgements

a. Funding/Support: We gratefully acknowledge the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund (Ratchadapisek Sompoch Endowment Fund) grant number GA68/019. We sincerely appreciate the invaluable support of the Thai Red Cross Eye Bank, under the Thai Red Cross Society, for their provision of crucial data. b. Financial Disclosures: No financial disclosures. c. AI Assistance Disclosure: The authors used ChatGPT-4o (OpenAI), an AI-based language model, solely for English editing to improve clarity and readability. The AI was not involved in data analysis, interpretation, or content generation beyond linguistic refinement. The authors take full responsibility for the originality, accuracy, and integrity of the content presented in this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W. and V.P. contributed equally to all aspects of this study, including study conception and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the submitted version.V.S. contributed to preliminary data analysis and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.T.K. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript.K.S. provided supervision regarding methodology and data interpretation and contributed to manuscript review and approval.All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wannapanich, T., Puangsricharern, V., Satitpitakul, V. et al. Risk factors for corneal transplantation in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy from a large Thai cohort. Sci Rep 15, 42355 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26423-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26423-0