Abstract

Nowadays, due to their exceptional strength, hardness, and resistance to wear, hardened AISI D2 and DC53 tool steels are frequently used in the tool and die-making business. But these materials are difficult to machine conventionally because they include metallic carbides that are abrasive and shorten the life of the cutting tool. Wire electric discharge machining (WEDM) is broadly used to obtain exact details on these hardened steels. However, differences in geometric attributes may result in differences in the machining process. The impact of machining parameters on linear cutting speed (CS) and volumetric material removal rate (MRR) for both flat and curved profiles is examined in this work. These parameters include peak current (IP), voltage (V), spark gap/pulse (P), and heat-treated material type (D2 and DC53). A Taguchi L18 orthogonal array is employed in the study to methodically evaluate performance disparities associated with various geometric characteristics. Understanding process physics is aided by energy dispersive X-ray analyses (EDX) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), while statistical variability and parameter importance are investigated using analysis of variance. An artificial neural network (ANN) is designed to predict output parameters and assess correlations between experimental and anticipated values in order to handle inconsistencies and complex interactions. Ultimately, the parameters are improved using a non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II), which leads to notable gains in CS and MRR for curved and flat profiles by 63.17%, 75.36%, 74.10%, and 73.38%, respectively, over unoptimized settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-alloy tool steel D2 is widely utilized in manufacturing dies and punches for the sheet metal forming industry, celebrated for its superior strength, corrosion, and wear resistance. However, the high chromium (11–12%) and carbon (1.55–1.75%) content in its composition make it less tough1,2. This reduced toughness is largely due to carbide chips in D-series electrode steels, which complicates conventional machining and shortens the lifespan of cutting tools. WEDM offers an effective solution by eliminating the need for direct physical interaction between the wire tool and the workpiece, making it suitable for adding intricate details to hardened D2 and DC53 tool steel, among other materials. This process ensures a burr-free machined surface and prevents tool damage. Tilekar et al.3 described DC53 as a modified version of traditional D2 tool steel, with 50% lower chromium and carbon content. The refinement of carbides in its microstructure provides enhanced toughness while maintaining hardness similar to D2. The newly developed DC53 steel surpasses SKD11 steel as a cold die material, offering exceptional toughness, wear resistance, and ease of machining. WEDM is commonly used for machining DC53 steel, as it precisely cuts conductive materials like DC53 using an electrically charged wire, ensuring high accuracy and minimal material waste. Key aspects of WEDM with DC53 steel include wire management, SR, MRR, and the effects of metallurgical and thermal changes on the machined surface. This technique is essential for creating operative machining plans and maximizing cutting factors to increase yield and the caliber of finished products4.

Manufacturers are facing growing market demands to produce precise, high-tech products using non-traditional methods. WEDM offers a solution by enabling the cutting of intricate metal shapes with exceptional accuracy. In WEDM, an electric arc forms between the base material (workpiece) and the wire tool, which discharges a significant amount of electricity, removing material from the workpiece5. The dielectric fluid is essential in this process, as it helps flush away the molten metal from the gap between the workpiece and the wire tool6,7. Precision is achieved in WEDM by numerically controlling the movement of the wire electrode holder, allowing for the creation of complex shapes, precise dimensions, and high-quality surfaces8. WEDM is particularly effective for machining hard materials and creating diverse profiles, making it suitable for D2, D3, and various tool and die steels. Performance parameters, including surface morphology, KW, and MRR including microstructural examination of the RLT and SR have been the subject of research. The wire selection in the WEDM process is important since it affects surface finish, dimensional accuracy, and CS9. While steel, Cu, and brass wires are commonly used, Mo wire stands out due to its high tensile strength and melting point, making it ideal for precision work10. Mo wire is also cost-effective due to its reusability and can withstand higher tensions11, reducing wire breakage and improving surface integrity compared to brass wire, particularly when machining titanium alloys12. Moreover, Mo wire has demonstrated better CS and SR compared to brass wire13. Different researchers conducted various studies in the context of WEDM of distinct materials for studying SR, KW, MRR, and dimensional accuracy.

Khan et al.14 conducted WEDM experiments on DC53 steel material using various processing parameters and found that PON was the most critical factor influencing responses, such as SR and MRR. Manjaiah et al.15 carried out a detailed MOO study for WEDM on AISI D2 steel and discovered a direct relationship between their findings and MRR, SR, and RLT. They reported that PON significantly impacted KW by 47.06%, MRR by 49.62%, and SR by 52.14%. Praveen et al.16 studied the influence of PON, POFF, and IP on SR and MRR during WEDM of Cu-Al-Mn ternary shape memory alloy. They observed superior surface quality at low energy input but encountered unwanted debris and blowholes at higher IP. Kanlayasiri et al.17 determined the WEDM of DC53 steel material by incorporating the distinct processing parameters in terms of SR. The authors claimed that the IP and PON were the most influential parameters for SR and also determined that the developed mathematical model for the evaluation of SR has an error of less than 7%. Natarajan et al.18 applied a Grey-based ANN model to reduce TM and enhance surface quality in WEDM. Using Taguchi design and ANOVA, they compared estimated and actual values, confirming the model’s predictive accuracy. Singh Nain et al.19 assessed the surface finish of Nimonic-90 using WEDM with ANN, genetic programming (GP), and SVM approaches. An exterior contact profilometer was applied to evaluate the superalloy’s surface quality, and the models provided accurate predictions of SR features. The GP PUK kernel model was particularly effective. Nain et al.20 also studied Udimet-L605 after WEDM, using advanced ML techniques to evaluate MRR and SR. Statistical analysis indicated that PON and the interaction of PON with POFF, VS, and WT significantly influenced SR, while PON, VS, and POFF were critical for MRR.

The literature reviewed indicates that numerous studies have been conducted on WEDM for various materials using different processing parameters. However, there is a gap in accurately correlating the discrepancies in the machining mechanism when the geometric features of the desired product are altered. Therefore, this study aims to assess and map the effects of machining parameters—such as IP, V, P, and MT on CS and MRR for complex profiles, including flat and curved features. This evaluation is particularly crucial for heat-treated D2 and DC53 steels, as it aids machinists in producing accurate and efficient dies. The study employs four distinct input parameters: IP in A, P in mu, V in Volts, and the type of material (D2 and DC53). To provide a comprehensive understanding of the process physics SEM has been utilized. Additionally, ANOVA was performed to identify the most significant input parameters affecting the response measures. Following this analysis, an ANN model was developed to predict output values and establish the relationship between experimental and forecasted data. Moreover, MOO using NSGA-II was conducted to determine the optimal set of processing parameters that enhance response measures. Ultimately, the study suggests the optimal set of parameters that resulted in improved values for CS for flat and curved surfaces, and MRR for flat and curved surfaces. To further highlight the novelty of work, the details are as follows:

-

There is a lack of detailed studies that address the difference in cutting performance between the tool steels DC53 and D2, particularly in terms of their physical properties.

-

The cutting performance of both materials has not been fully optimized for high-speed machining, which points to a significant limitation within WEDM systems.

-

Approaches such as DOE, AI, and MOO have not been effectively utilized to uncover new process characteristics. Given the complex nature of the process, which involves thermal, electrical, surface melting, and solidification dynamics, traditional simulation methods fall short in providing a complete comparison of the cutting performance of these tool steels.

Materials and methods

In this investigation, AISI D2 and DC53 materials were employed for CNC WEDM (Model: DK7740A, produced by Suzhou Baoma Numerical Control Equipment Co., Ltd., in Suzhou) under different processing conditions. D2 steel, known for its high carbon content and air-hardening properties, provides excellent resistance to wear and abrasion. It can achieve hardness levels between 40 and 42 HRC and is suitable for heat treatment. When properly hardened, D2 steel shows minimal deformation and offers moderate corrosion resistance due to its high chromium content. DC53 is renowned for its remarkable hardness and durability. High-wear resistance and toughness applications are a good fit for this premium cold work die steel. DC53 has exceptional qualities due to its well-balanced composition, making it a great option for demanding industrial processes. It is specifically designed to be stable in high-pressure situations and to tolerate mechanical stress. Table 1 summarizes the chemical compositions of both materials2,21, while Table 2 offers comprehensive details on the mechanical and physical properties of D2 and DC5322,23. Both materials have a thickness of 10 mm, with a 70 mm diameter for each, as shown in Fig. 1. The entire framework of this current study has been illustrated in Fig. 2.

Materials for the workpiece used in WEDM are: (a, b) D2 steel, (c) DC53 steel24.

Heat treatment was used to raise the hardness of both metals in order to enhance the characteristics of DC53 and D2. Hardening was done as the initial stage in enhancing the qualities of both materials. This method of heating led to a hardness of 62 HRC for the materials D2 and DC53, which were then maintained at a temperature of 980 to 1020 °C for 12 min. However, tempering was applied to both materials in the second stage. During the tempering process, the workpieces were heated to between 600 and 610 °C for 20 min, achieving the necessary 40 HRC hardness. Table 3 compares the effects of hardening and tempering as well as the hardness results that were obtained.

Using SolidWorks software, a sophisticated profile for D2 and DC53 steel was created with flat, curved, and inclined surfaces. Figure 3a–c depict the intricate shape that was created with SolidWorks software and the actual machining setup for tool steel D2 and DC53. With a convex SR, the form consists of flat, curved, and inclined surfaces. The shape was created so that WEDM machining would be feasible. The intricate form used for this investigation was intended to test the limits of WEDM. The surfaces that are inclined, curved, and flat offer various machining challenges. Convex surface roughness presents another difficulty since it necessitates precise control of the WEDM process in order to prevent surface flaws.

Drawings in SolidWorks for D2 and DC53 steels (a) Dimensions of intricate profiles, (b) WEDM prototypes, (c, d) machined samples following the WEDM process24.

The DOE is a structured approach for analyzing how different parameters behave and impact process performance. It simplifies the understanding of the process and provides valuable insights into the variables influencing it. In this investigation, the processing parameters employed for the experimentations were IP at 2, 3, and 4 A, P at 50, 70, and 90 mu, voltage at 90, 95, and 100 V, and MT with D2 and DC53 steels, as outlined in Table 4. The experiments were designed using the Taguchi L18 Orthogonal Array. The Taguchi method is widely recognized by researchers as a reliable statistical technique for optimizing process variables, focusing on performance, cost, and quality. In addition, the Taguchi method is a useful design technique that rapidly determines the most important factors, saving time and resources and guaranteeing reliable and effective results25.

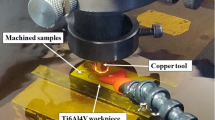

The goal of the experimental phase was to assess the effect of material attributes on WEDM performance and analyze input parameters for a WEDM. The experimental setup and generation of electric spark in the presence of dielectric are shown in Fig. 4a, b, whereas the front and top views of the generated profile through WEDM are displayed in Fig. 4c, d. Time and parameter observations were made, and the collected data underwent careful examination. For cutting D2 and DC53 materials, a 0.18 mm-diameter Mo wire electrode was utilized. In this study, four machining responses, such as CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat, and MRR_Curve, have been studied for flat and curved profiles. The response value of CS was measured using Eq. 1 for each profile (CS_Flat, and CS_Curve). The value of machine time was directly recorded from the control panel of the machine. Whereas, Eq. 2 was utilized to measure the response value of MRR for each profile26.

where in Eq. 2, n varies from 1 to 2, however, 1 represents the flat profile, 2 depicts the curve profile.

(a) The WEDM control unit, (b) The plasma channel creation and operating environment, (c, d) WEDM machined samples24.

Results and discussion

This part describes the findings of research in terms of four outputs (CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat, and MRR_Curve) against the given set of input parameters. The S/N ratios of all the response measures have been presented in the Table 5. To elaborate on the outcomes of the experimental data, parametric plots were made. The significance of the performance variable has also been evaluated via ANOVA. The impact of given factors on the responses is studied in the next section.

Analyzing the effect of process parameters

Cutting Speed at plane/flat geometric profile

Figure 5 displays how various parameters affect the CS on a flat surface during the WEDM process. The primary focus here is the effect of changing the material type on the CS of flat surfaces. As shown in Fig. 5, the DC53 steel consistently demonstrates a higher CS compared to D2 steel. This difference can be attributed to DC53’s superior thermo-mechanical properties14. Specifically, the CS for DC53 in WEDM is approximately 8.47% higher than that observed with D2. One key reason for this performance is the composition of DC53, which contains a higher percentage of carbon, chromium, and molybdenum by weight. These elements contribute to increased hardness, toughness, and resistance to wear, making DC53 better suited for operations that require enhanced CS. The fine and uniformly distributed carbides within DC53’s microstructure also play a role in its efficient performance. Moreover, DC53 generally exhibits higher thermal conductivity than D2, allowing it to dissipate heat more effectively during machining. This reduces the likelihood of thermal damage to both the workpiece and the cutting wire. SEM images of the machined surfaces, shown in Fig. 6a, b, further highlight the material differences. The surface of the WEDMed D2 steel features large micro-globules and relatively shallow craters, indicating a lower CS. In contrast, DC53 shows finer globules and broader craters, which reflect a more stable and efficient material removal process. These microstructural characteristics support the conclusion that DC53 offers improved machining performance and is well-suited for high CS applications.

The relationship between IP and CS follows a linear pattern, as shown in Fig. 5. This pattern indicates that higher CS are achieved when the IP is increased from 2 to 4 A. As the IP rises, the amount of energy supplied to the machining process also increases. This added energy raises the temperature of the machining zone, which, in turn, enhances the CS. Further increases in CS are observed with higher IP, as the additional energy leads to more melting and vaporization of the workpiece material, facilitating smoother material removal and reducing machining time. Moreover, a higher IP promotes better drainage of molten material and debris from the machining zone, reducing electrode wear and improving machining stability. These factors collectively contribute to a higher CS. Similar conclusions have been supported by other researchers, such as Rajeev Kumar27, who noted that an increase in IP leads to higher CS due to the enhanced discharge energy. This greater energy boosts the cutting rate, further improving CS during WEDM operations. On average, the CS at 4 A is approximately 1% higher than that at 2 A.

The third key factor is the P, which defines the gap between the wire tool and the workpiece surface. Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between P and the CS of a flat surface. It is expected that increasing P, or widening the gap between the wire and the surface, leads to a reduction in CS28. This happens because of a decrease in spark density, increased discharge instability, lower MRR, and higher wire wear29. When the gap between the workpiece and the wire electrode is smaller, the electrical energy concentrates within a smaller volume of material during each discharge cycle, resulting in more intense localized heating and vaporization. This concentration of energy accelerates material erosion, leading to higher CS. Additionally, a smaller gap allows for more efficient heat dissipation into the surrounding material and dielectric fluid, reducing the risk of thermal damage to both the workpiece and the electrode. The effective heat dissipation enables higher CS by preventing excessive heat build-up. Moreover, a reduced gap between the wire and the workpiece promotes the formation of a stable and efficient plasma channel, as shown in Fig. 7. This enhances energy transfer and contributes to more effective material removal. Consequently, as the pulse magnitude increases, the CS decreases. The findings suggest that for cutting a flat surface using the WEDM method, a gap of 50 mu is optimal for achieving the highest CS.

Generation of plasma channel in WEDM, reused with permission from30.

The fourth factor is V, and its impact on the CS of the flat surface is shown in Fig. 5. The graph reveals a linear relationship, suggesting that as V increases, CS also increases. Existing studies indicate that a higher V leads to an increased MRR because of the higher discharge density between the wire and the target surface31. The strength of the electrical discharge between the wire electrode and the workpiece primarily depends on the voltage. As V rises, the electrical potential difference increases, resulting in a more powerful discharge. This enhanced discharge energy facilitates more efficient material removal, leading to a higher CS. Additionally, a higher voltage helps establish a more intense and stable plasma channel during the discharge process. This stable plasma channel provides a conductive path for the discharge current, which improves energy transfer to the workpiece and speeds up the material erosion. Consequently, this leads to an increase in CS. For comparison, the CS achieved at 100 V is 1.67 times greater than the CS observed at 90 V. Overall, DC53 material, an IP of 4 A, a P value of 50 mu, and 100 V are ideal levels for achieving a high CS of a flat surface when using the WEDM setup for machining.

Cutting Speed at curved geometric profile

The CS for a curved surface has also been assessed in relation to the parameters used during the WEDM process, as shown in Fig. 8. From this figure, it can be concluded that DC53 material produces a higher CS on curved surfaces compared to D2 material. This trend is consistent with the findings for flat surfaces, as seen in Fig. 5. The superior performance of DC53 is attributed to its enhanced properties, including high toughness, exceptional wear resistance, and the minimal residual stress it generates during the WEDM process. Additionally, the high toughness of DC53 helps reduce chipping effects during the cutting process, allowing the wire to move more smoothly through the material. Consequently, DC53 delivers a higher CS. To further analyze the material, EDX analysis was performed to determine the elemental composition of the D2 material after machining using the WEDM setup (refer to Fig. 9). The EDX spectrum in Fig. 9 shows a significant amount of iron (Fe) present on the surface of the D2 steel followed by the carbon.

The effect of IP on the CS of a curved surface is also illustrated in Fig. 8. It is evident that the CS increases when the IP is raised from 2 to 4 A. This trend mirrors the previous findings shown in Fig. 5. The increase in CS can be attributed to the higher number of discharges that occur as the IP increases. These additional discharges accelerate material removal, leading to a higher CS32. However, machining a curved surface is inherently more complex than machining a flat surface due to the need to handle direction changes. This added complexity requires more precise movement of the electrode, as well as adjustments in wire electrode vibrations and machining parameters, which may result in a slower CS. The frequent direction changes during machining a curved surface cause more wear on the electrode and require more frequent pauses for maintenance, further slowing down the process. Additionally, slower machining speeds might be necessary to manage localized areas of higher thermal energy along curved paths, which could cause accelerated electrode wear and increase the risk of thermal damage to the workpiece. To examine the surface texture of the machined areas, SEM analysis was performed at IP values of 2 A and 4 A, as shown in Fig. 10a and 9b. At 2 A, the SEM reveals the presence of µ-globules and shallow craters, indicating a relatively slower CS. In contrast, the SEM image at 4 A shows smaller globules and larger craters, suggesting some degree of material re-deposition due to melting. The observed changes in surface morphology at higher IP values, with smaller globules and larger craters, reflect improved material erosion efficiency and greater machining stability.

The influence of the third factor, P, on the CS of a curved surface is also depicted in Fig. 8. The gap between the wire electrode and the workpiece, referred to as P in WEDM, has an inverse relationship with CS. As shown by the decreasing curve, an increase in P magnitude leads to a reduction in CS on a curved surface. In this context, P refers to the distance between the wire and the cutting surface. When the gap between the wire and workpiece increases, the CS decreases28. A narrower gap, on the other hand, leads to more focused energy transfer and localized heating, resulting in higher CS and more efficient material erosion. However, a larger P indicates a wider gap between the wire and the workpiece during each discharge cycle. This larger separation reduces the intensity of the electrical discharge, leading to slower CS and less effective material removal. Research suggests that a larger gap also causes an arcing effect and increases wire wear, which impairs cutting performance and further reduces CS.

The effect of V variations on the CS of a curved surface is also illustrated in Fig. 8. A positive correlation is observed when V increases within the range of 90–100 V. This finding aligns with existing literature, which confirms a direct relationship between V and CS19,31,33. In the WEDM process, V plays a crucial role in creating the electric field by energizing the dielectric medium. A higher V reduces the discharge delay time, allowing the electric field in the cutting zone to become stronger. Additionally, a higher voltage leads to a greater number of discharges per unit time, which accelerates the erosion of material particles and results in a higher CS. In conclusion, the ideal combination of parameters for achieving a high CS on a curved surface includes DC53 MT, an IP of 4 A, a P of 50 mu, and a V of 100 V.

Volumetric MRR at plane/flat geometric profile

Figure 11 illustrates the changes in parametric trends for MRR on a flat surface. The influence of each factor on the MRR response is assessed individually. For example, the effects of two materials, DC53 and D2, on MRR are discussed here. As shown in Fig. 11, DC53 outperforms D2 alloy in terms of MRR. This is attributed to the superior mechanical properties of DC53, such as higher hardness, wear resistance, and strength24. In fact, DC53 achieves 1.15 times the MRR value of D2 material. To further explore this, an EDX analysis was performed. The EDX plot in Fig. 12 reveals a significant presence of iron on the DC53 surface followed by the chromium (Cr). Based on these findings, DC53 proves to be a more effective material than D2 steel for achieving high MRR on a flat surface during the WEDM process.

The second major factor is IP, which plays a crucial role in determining the MRR during the WEDM process. Figure 11 shows a linear relationship between IP and MRR within the range of 2–4 A. This suggests that increasing the IP value leads to a corresponding increase in MRR. When the IP is set to a lower value (2 A), the energy delivered to the work surface is minimal due to fewer discharges occurring per unit time. As a result, the material erosion rate is lower. In contrast, when the IP is increased to 4 A, a higher spark density is generated, as more sparks are produced, leading to a higher MRR. Therefore, 4 A is considered the optimal IP value for achieving maximum MRR on a flat surface during the WEDM process.

Figure 11 also illustrates the relationship between P and MRR on a flat surface. A negative correlation can be seen between these two variables. The downward-sloping curve in Fig. 11 indicates that as the gap between the wire and the work surface increases, or when the P value is raised from 50 to 90 mu, the MRR decreases. This occurs because a larger pulse magnitude or wider gap reduces the energy delivered to the cutting zone. As a result, there is less material melting and vaporization, which leads to a lower MRR29. The surface characteristics of the machined profile at two different P settings (50 and 90 mu) are shown in Fig. 13a, b, respectively. Therefore, a smaller pulse value (50 mu) is preferable for achieving a higher MRR on a flat surface during the WEDM process.

The fourth factor, V, and its effect on MRR is shown in Fig. 11. The data reveals that MRR increases as the voltage rises from 90 to 100 V. This change is primarily due to the increased spark energy at higher voltage levels. A higher spark density leads to a greater number of material particles being removed from the target surface, resulting in a higher MRR34. As a result, MRR improves significantly. Moreover, at 100 V, the MRR is 1.57 times greater than that at 90 V. In conclusion, the optimal settings for achieving maximum MRR on a flat surface during the WEDM process are using DC53 material, with an IP of 4 A, a P of 50 mu, and a voltage of 100 V.

Volumetric MRR at curved geometric profile

The influence of processing parameters on the MRR of a curved surface during the WEDM process is also explored here. The parametric trends are presented in Fig. 14. As with previous results, the effects of two materials, D2 and DC53, on MRR are discussed first. From Fig. 14, it is evident that DC53 performs better than D2 due to its superior hardness and exceptional strength. EDX analysis for both materials is shown in Figs. 15a and 14b. The EDX plot in Fig. 15a reveals that iron (Fe) is the predominant element (by weight) in D2, followed by carbon . In contrast, the EDX analysis for DC53 in Fig. 15b shows that both Fe and Cr have higher weight percentages than in D2, contributing to the enhanced toughness, hardness, and wear resistance of DC53.

Figure 14 demonstrates a clear positive relationship between IP and MRR. As IP increases, so does the MRR. At lower IP levels, the spark intensity in the cutting zone is reduced, leading to less material removal from the surface. A higher MRR on the curved surface is observed when transitioning from machining a flat surface to a curved one. The curved path allows for more consistent electrode contact, which enhances energy transfer and optimizes material erosion processes such as melting and vaporization. However, the increased MRR on the curved surface results in a broader energy distribution and more aggressive material removal, which, in turn, increases the kerf width and consequently raises the MRR. As a result, the lowest MRR is observed at 2 A. In contrast, at higher IP values (4 A), the number of discharges per unit of time increases, amplifying the cutting process and leading to a significant rise in MRR35. Therefore, an IP of 4 A is considered the optimal setting for achieving maximum MRR during the WEDM process.

Similar to other parameters, P also exhibits an inverse relationship with MRR when machining a curved surface in the WEDM process (see Fig. 14). At a pulse value of 50 mu, a higher MRR is observed due to the smaller gap between the wire and the target surface36. However, as the pulse magnitude increases to 90 mu, the gap widens, which negatively impacts the cutting efficiency. This larger gap reduces the intensity of the discharges, limiting their ability to effectively reach the workpiece surface34. As a result, the material removal process becomes less efficient at higher pulse values. Therefore, a pulse value of 50 mu is the most suitable for achieving a higher MRR on a curved surface during the WEDM process.

The final factor is V, and its impact on MRR for a curved surface is shown in Fig. 14. As the voltage increases, the MRR also rises. This is due to the increased number of sparks generated on the processing surface, which is driven by the strengthening of the electric field. These sparks efficiently erode material particles, resulting in a higher MRR32. The surface texture of the machined profile at high voltage can be observed in Fig. 16. On the other hand, when a lower voltage is applied during the WEDM process, the opposite effect occurs. In conclusion, the optimal settings for achieving a high MRR in the WEDM process are: DC53 material, an IP of 4 A, a P of 50 mu, and a voltage of 100 V.

In summary, it can be concluded that DC53 material is the most ideal for providing optimum results for each response parameter. Additionally, the values of IP (4 A), P (50 mu), and V (100 V) have been identified as the optimal settings for improving machining performance during the WEDM process. The main outcomes are also concluded in Table 6. Since, DC53 outperforms over D2 steel for all the responses because of its competitive hardness, toughness, and low thermal conductivity value. Additionally, machining of DC53 is nearly 40% faster than D2 steel, which significantly reduces processing time. Consequently, the overall manufacturing cost of DC53 is lower than that of D2 steel. Therefore, researchers have identified DC53 as a viable substitute for D2 steel37.

A graphical plot has also been made keeping an eye on the outcomes for both flat and curved surfaces. From Fig. 17, it can be perceived that, for a flat surface, there is a higher CS with lower MRR. Conversely, for curved surfaces, there is lower CS but higher MRR. The difference in outcomes can be attributed to the cutting dynamics. Minimal vibrations and a smoother cutting process are achieved when the wire cuts the object in a single direction, such as straight travel, on a flat surface. This leads to higher CS and lower MRR. In contrast, cutting a curved surface involves multi-directional movement, including both straight and curved paths. This introduces more vibrations, particularly on the curved surface. Additionally, the narrower kerf width on a curved surface leads to the removal of a larger amount of material, resulting in higher MRR and lower CS.

Significance analysis

To enhance the robustness of the research, ANOVA was performed on all four responses using the specified parameters. The analysis focused on p values and F-values, where the p value indicates the statistical relevance of the parameters, and the F-value reflects the percentage of contribution. To confirm the accuracy of the developed models, both adjusted and predicted R2 values were calculated.

Linear cutting speed

The results of the ANOVA analysis for the CS of both flat and curved surfaces are summarized in Table 7. It is evident that all the input variables have a significant impact, with p values less than 0.05. Among these variables, the influence of IP is the most substantial, accounting for 52.54% and 51.75% of the variations in CS_Flat and CS_Curve, respectively. The mathematical models for these responses are provided in Eqs. 3 and 4, which can be utilized to measure CS_Flat and CS_Curve. The adequacy of these models is confirmed by the R2 values presented in Table 7. The models are considered highly reliable due to their R2 values, which are close to 1.

Volumetric material removal rate

Table 8 presents the ANOVA results for MRR for both surface types. As observed with CS, all factors in the case of MRR exhibited significant effects, with p values less than 0.05. Among these factors, the influence of IP is dominant, contributing 59.95% to both MRR_Flat and MRR_Curve. Furthermore, the high R2 values for both responses indicate that the proposed models are reliable. The mathematical formulas for these models, given in Eqs. 5 and 6, can be applied to calculate MRR_Flat and MRR_Curve.

Development of an ANN model

Data for CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat, and MRR_Curve were collected during the WEDM process of selected materials by varying the processing parameters (IP, P, and V). Modelling such a complex set of outputs can be challenging. Therefore, an ANN, specifically a “multilayer perceptron”, serves as an effective tool to establish connections between the processing parameters and the resulting outputs, providing reliable predictions. This approach is particularly useful for uncovering intricate, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional input spaces, even when the system’s characteristics are not clearly defined. A substantial body of research has explored this method38. The ANN employed in this study is organized as depicted in Fig. 18.

The main advantage of applying optimization algorithms and ML methods lies in their enhanced predictive abilities. By using ML techniques before performing physical experiments, costs associated with machining, materials, and processing have been reduced39. In today’s manufacturing landscape, there is a growing trend to integrate ML techniques into production systems to boost efficiency and minimize material waste. A key factor in optimizing performance is striking the right balance between the complexity of the ANN design and its accuracy. The number of neurons in the hidden layer plays a crucial role in determining the model’s effectiveness; an optimal neuron count leads to more accurate predictions along the curve. However, a model with excessive complexity may struggle to generalize across different datasets. On the other hand, if the model lacks enough neurons within a reasonable range, its fit may suffer, and it could yield inaccurate results. Therefore, selecting the appropriate number of neurons is a critical decision, usually falling within 1–2.5 times the total number of input variables. A single hidden layer has been used. As it is mentioned that Taguchi L18 has been utilized for the DOE, therefore, 18 datapoints have been utilized for the training, testing and validation purposes. However, for the training of ANN modelling, the partitioning strategy of the data such as training 80%, testing 10%, and validation 10% has been utilized. MATLAB (R2018a) has been utilized on a Core-i7, 7th generation laptop for the modelling purposes. To evaluate the performance of ML models, metrics such as R2 and RMSE are particularly useful40. Below are the mathematical formulas for R2 and RMSE:

In this case, \({y}_{i}\) is the output variable’s actual value, whereas \({\widehat{y}}_{i}\) represents the output variable’s value predicted by the model; \({\overline{y} }_{i}\) is the output variable’s mean, and \(i\) = 1, 2, 3…, N denotes the overall count of observations. R2 is a scale of accuracy from zero to one, while RMSE assesses the error between the actual and model-predicted responses. The cumulative regression coefficient R value of the ANN modelling, as shown in Fig. 19, is 0.99472, demonstrating a strong correlation between the intended outcome and processing parameter values. R2 and RMSE are the two main measures used to evaluate the effectiveness of ML models40.

To investigate the relationships between the input variables (IP, P, V, and MT) and the output responses, line graphs were employed. To improve the accuracy of the response variables, an ANN model was created. In this research, the input variables IP, P, V, and MT were input into the ANN to predict the values for CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat, and MRR_Curve. The model was fine-tuned using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm, along with the minimization of the sum of squared errors, to optimize parameters like weights and biases in the feed-forward backpropagation ANN. The training process was halted early based on criteria including a minimum gradient threshold of 1.0 × 10–20, a maximum validation failure threshold of 6, and a limit of 10,000 training epochs.

Figures 20a–d illustrate the ANN models developed for WEDM processing of D2 and DC53 materials using a Mo wire electrode. The model’s performance was assessed by analyzing R2 and RMSE values, considering a range of hidden neuron layers from 3 to 10 and a LR between E−4 and E−1. In the training dataset, the ANN approach for CS_Flat, which used a nine-hidden-neuron layer (as seen in Fig. 20a), achieved an R2 value of 0.996. During testing and validation, the model accurately predicted CS_Flat with an R2 value of 1.0. The RMSE values for the hidden neuron layer during training and testing for CS_Flat were also low, recorded at 0.06 mm/min and 0.036 mm/min, respectively. Consequently, the ANN approach with nine hidden neurons and a LR of E−1 was found to be the most effective compared to other models for predicting CS_Flat.

CS_Curve of ANN models with three to ten hidden layer neurons is compared in Fig. 20b. In both training and testing, the models made comparable predictions. Because of its better R2 value in training of 0.999, however, in testing and validation, the R2 is equal to unity. Moreover, the lower RMSE for the training and testing datasets, which are 6.78E-03 mm/min & 0.0065 mm/min, respectively, the ANN approach with five neurons in the hidden layer and LR E−1 beat the other datasets in giving the best values.

An analysis of ANN approach with hidden layer neurons from 3 to 10 is shown in Fig. 20c, where the MRR_Flat of the WEDM process is evaluated. R2 values for training are greater than 0.99 for all generated models with good output-input mapping, however, R2 in testing and validation is equal to unity. The models generated by the validation dataset have different RMSE. The lowest RMSEtrain (0.747 cm3/min) and RMSEval (0.634 cm3/min) are found in the ANN approach with seven hidden layer neurons and LR E−1.

Figure 20d compares the ANN approach for MRR_curve with three to ten hidden layer neurons. The models generated predictions that were similar during training and testing. Despite having a higher R2 value of 0.999 during training, the R2 equals unity during testing and validation. Furthermore, the ANN approach with nine neurons in the hidden layer and LR E−3 outpaced the other datasets in providing the best values, as evidenced by the reduced RMSE for the training and testing datasets, which are 1.87E−04 cm3/min & 1.198 cm3/min, respectively. The best predicted model values of ANN for the output measures in terms of R2, and RMSE using LR and hidden neuron layer has been presented in Table 9.

Parametric optimization

NSGA-II is particularly suited for MOO problems, as it efficiently handles Pareto-optimal solutions while maintaining population diversity. Unlike RSM, which relies on predefined mathematical models and may struggle with highly nonlinear or discontinuous design spaces, NSGA-II is a robust, gradient-free approach capable of exploring complex, multi-model search spaces without requiring explicit functional approximations41. Compared to PSO, which is effective for single-objective optimization but may require modifications (e.g., weighted sum approaches) for multi-objective problems, NSGA-II inherently addresses competing objectives through non-dominated sorting and crowding distance metrics42. This ensures a well-distributed set of optimal solutions, which is critical for this study’s goals.

The first step in applying NSGA-II to solve a MOO problem is to create a population of potential solutions. A range of objective functions are used to evaluate the fitness of each solution. Then, using a non-dominated sorting procedure, the answers are arranged into several degrees of dominance. Iteratively, further fronts are found, and each solution within a front has its crowding distance computed to show how close it is to the objective space. Solutions with higher non-domination ranks and shorter crowding distances are preferred over those in denserly inhabited areas during the selection process. Crossover and mutation produce new solutions that open up new areas of the solution space for investigation. By producing a wide range of Pareto-optimal solutions that show trade-offs between conflicting goals, this technique helps decision-makers select the best course of action depending on their priorities. The procedure keeps on until the convergence criteria are met, or for a predetermined number of generations. Figure 21 shows the NSGA-II operating framework.

NSGA-II working schematic43.

This research focuses on determining the optimal solutions for CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat, and MRR_Curve by using NSGA-II to enhance the magnitudes of the input variables. The objective function is defined in Eq. 9, while the constraints applied to optimize the input variables are outlined in Eq. 10.

After successfully executing NSGA-II within the specified limits, a set of 18 combined solutions for both input and output variables was obtained, as detailed in Table 10. To optimize CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat, and MRR_Curve, NSGA-II suggests that the WEDM process should be conducted with process parameters set at IP = 3.99 A,P = 56.01 mu, V = 99.99 V, using DC53 material. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 22, the multi-objective function results in a CS_Flat of 2.797 mm/min, CS_Curve of 2.476 mm/min, MRR_Flat of 139.872 cm3/min, and MRR_Curve of 197.821 cm3/min when the constraints are applied.

For optimizing individual responses, the best input parameters have been identified through NSGA-II, which iterates over different combinations of process parameters to determine the most effective settings for each output variable. Table 11 presents the confirmatory experimental results that confirm the values for CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat, and MRR_Curve at the input settings suggested by NSGA-II in comparison to DOE un-optimized values.

Table 11 exhibits the WEDM results in terms of MRR_Flat, MRR_Curve, CS_Flat, and CS_Curve, which are derived from the contrast amongst the experimental findings and the NSGA-II proposed ideal settings. It’s evident from Table 11 that CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat and MRR_Curve improved by 63.17%, 75.36%, 74.10% and 73.38%, respectively, compared to the un-optimal settings of DOE.

Moreover, it is validated that the results suggested by the NSGA-II for this current study are better than the results from previous studies44,45 in terms of D2 and DC53 materials.

Conclusions

The performance of WEDM has been analyzed for tool steels D2 and DC53, focusing on CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat, and MRR_Curve at various processing parameter settings. To evaluate the responses, a Taguchi L18 experimental design was used. The output responses were examined through SEM and EDX analysis, alongside the underlying process mechanisms. An ANN-based model was then developed to improve the prediction accuracy of the response variables and explore their interdependencies. Following this, a MOO approach using the NSGA-II modelling technique was applied to determine the optimal combination of input and output factors. The results of this study led to several key conclusions.

-

In comparing flat and curved surfaces, it is evident that the curved surface exhibits a lower CS (2.46 mm/min) but a higher MRR (205.21 cm3/min). This is attributed to the increased vibrations and less kerf width resulting from the wire’s movement along both straight and curved paths during machining. Whereas the vice versa trend is observed for the flat surface. Furthermore, for a curved profile, the value of MRR is 45.35% greater and CS is 68.29% lesser compared to the responses observed in the case of a flat profile.

-

Amongst two materials, DC53 material consistently outperformed D2 material across all response parameters, owing to its superior mechanical properties. Therefore, the DC53 material has offered the high toughness and hardness that is comparable to D2 tool steel due to the carbide refinement in the microstructure.

-

Regarding the effect of IP on the output variables, the optimal value was found to be 4 A. Higher IP values increased spark density, leading to significant improvements in the response magnitudes. For all four responses (CS on flat and curved surfaces, MRR on flat and curved surfaces), the values at 4A are 105.69%, 105.84%, 120.56%, and 120.56% greater, respectively, than the values at 2 A.

-

Pulse also played a crucial role in determining the responses, with a lower magnitude (50 mu) yielding outstanding results. This value minimized arcing effects and wire wear, resulting in improved responses. At a pulse of 50 mu, the MRR values for flat and curved profiles are 43% and 43.34% higher as compared to the response values at a higher level of pulse, such as 90 mu. For CS on flat and curved profiles, these percentages change to 49.77% and 49.58%, respectively.

-

High voltage values (100 V) led to enhancements in all output parameters. The increased voltage strengthened the electric field in the cutting zone, facilitating rapid erosion of work particles and overall improvement in responses. It is further foreseen that magnitude of four responses, such as CS on flat and curve surfaces, MRR on flat and curve profiles, at 100 V are 67.15%, 67.13%, 56.85%, and 57.13% larger than that of the values at 90 V.

-

The ANOVA analysis proves the significance of design parameters for all the responses, having p value smaller than 0.05. Moreover, R2 values confirmed the high reliability of the proposed models.

-

Responses have been trained, tested, and validated using the ANNs, especially when R2 and RMSE metrics are involved. The hidden layer’s neuron count has ranged from three to ten. R2 values for all response measures during training showed a high degree of prediction accuracy, surpassing 0.99, indicating a significant correlation between the input and output variables. R2 did, however, approach one throughout testing and validation. Furthermore, the RMSE error, a measure of the variation between experimental and anticipated values, has been computed and presented using line charts, indicating a negligible disparity.

-

After MOO using NSGA-II, it is revealed that CS_Flat, CS_Curve, MRR_Flat and MRR_Curve improved by 63.17%, 75.36%, 74.10% and 73.38%, respectively, compared to the un-optimal settings of DOE.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WEDM:

-

Wire electric discharge machining

- EWR:

-

Electrode wear rate

- CS:

-

Cutting speed

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- PON :

-

Pulse on time

- CS_Flat:

-

Cutting speed for flat surface

- MRR_Flat:

-

MRR for flat surface

- RLT:

-

Recast layer thickness

- CCD:

-

Central composite design

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- KW:

-

Kerf width

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- RLT:

-

Recast layer thickness

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

- GRA:

-

Grey relational analysis

- 2FI:

-

Two-factor interaction

- SRV:

-

Servo reference voltage

- DFA:

-

Desirability function analysis

- RMSE:

-

Root-mean-square-error

- MOO:

-

Multi objective optimization

- SR:

-

Surface roughness

- OC:

-

Overcut/dimensional inaccuracy

- MRR:

-

Material removal rate

- SV :

-

Spark voltage

- POFF :

-

Pulse off time

- CS_Curve:

-

Cutting speed for curve surface

- MRR_Curve:

-

MRR for flat surface

- RSM:

-

Response surface methodology

- R2 :

-

Coefficient of determination

- EBPTA:

-

Error back propagation training algorithm

- IP :

-

Peak current

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- ELM:

-

Extreme learning machine

- WFR :

-

Wire feed rate

- WT :

-

Wire tension

- PC:

-

Power consumption

- NSGA-II:

-

Non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm

- Mo:

-

Molybdenum

- TM :

-

Machining time

- LR :

-

Learning rate

References

Nas, E., Özbek, O., Bayraktar, F. & Kara, F. Experimental and statistical investigation of machinability of AISI D2 steel using electroerosion machining method in different machining parameters. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1241797 (2021).

Majhi, S. K., Mishra, T. K., Pradhan, M. K. & Soni, H. Effect of machining parameters of AISI D2 tool steel on electro discharge machining. Int. J. Current Eng. Technol. 4, 19–23 (2014).

Tilekar, S., Das, S. S. & Patowari, P. K. Process parameter optimization of wire EDM on aluminum and mild steel by using Taguchi method. Proc. Mater. Sci. 5, 2577–2584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mspro.2014.07.518 (2014).

Nawaz, Y. et al. Parametric optimization of material removal rate, surface roughness, and kerf width in high-speed wire electric discharge machining (HS-WEDM) of DC53 die steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 107, 3231–3245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-05175-3 (2020).

Ponappa, K. et al. The effect of process parameters on machining of magnesium nano alumina composites through EDM. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 46, 1035–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-009-2158-9 (2010).

Afridi, S. A., Younas, M., Khan, Z. & Khan, A. M. Investigating wire electric-discharge machining (WEDM) parameters for improved machining of D2 steel: A multi-objective optimization study. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-024-01203-4 (2025).

Kumar, S., Jayswal, S. C. Machining performance analysis of wire-EDM for machining of titanium alloy using multi-objective optimization and machine learning approach. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E: J. Process Mech. Eng. 09544089241288009. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089241288009 (2024)

Ukey, K., Rameshchandra Sahu, A., Sheshrao Gajghate, S., et al. Wire electrical discharge machining (WEDM) review on current optimization research trends. Mater. Today: Proc. S2214785323034958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.06.113 (2023)

Maher, I., Sarhan, A. A. D. & Hamdi, M. Review of improvements in wire electrode properties for longer working time and utilization in wire EDM machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 76, 329–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-014-6243-3 (2015).

Manoj, I. V., Joy, R. & Narendranath, S. Investigation on the effect of variation in cutting speeds and angle of cut during slant type taper cutting in WEDM of Hastelloy X. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 45, 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-019-04111-2 (2020).

Mouralova, K. et al. Machining of pure molybdenum using WEDM. Measurement 163, 108010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108010 (2020).

Carlini, G. C. et al. WED-machining performance by reciprocating molybdenum wire on Inconel 718 with water or hydrocarbon dielectrics. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 119, 1853–1866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-021-08386-4 (2022).

Thiagarajan, C., Sararvanan, M. & Senthil, J. Performance evaluation of wire electro discharge machining on D3-tool steel. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 118, 943–949 (2018).

Khan, S. A. et al. A detailed machinability assessment of dc53 steel for die and mold industry through wire electric discharge machining. Metals 11, 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/met11050816 (2021).

Manjaiah, M., Laubscher, R. F., Kumar, A. & Basavarajappa, S. Parametric optimization of MRR and surface roughness in wire electro discharge machining (WEDM) of D2 steel using Taguchi-based utility approach. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 11, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40712-016-0060-4 (2016).

Praveen, N. et al. Effect of pulse time (Ton), pause time (Toff), peak current (Ip) on MRR and surface roughness of Cu–Al–Mn ternary shape memory alloy using wire EDM. J. Market. Res. 30, 1843–1851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.03.122 (2024).

Kanlayasiri, K. & Boonmung, S. Effects of wire-EDM machining variables on surface roughness of newly developed DC 53 die steel: Design of experiments and regression model. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 192–193, 459–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.04.085 (2007).

Natarajan, M. et al. Assessment of machining of hastelloy using WEDM by a multi-objective approach. Sustainability 15, 10105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310105 (2023).

Singh Nain, S. et al. Use of machine learning algorithm for the better prediction of SR peculiarities of WEDM of Nimonic-90 superalloy. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0013.1422 (2019).

Nain, S. S., Garg, D. & Kumar, S. Modeling and optimization of process variables of wire-cut electric discharge machining of super alloy Udimet-L605. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 20, 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2016.09.023 (2017).

Singh, V., Bhandari, R. & Yadav, V. K. An experimental investigation on machining parameters of AISI D2 steel using WEDM. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 93, 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-8681-6 (2017).

Terčelj, M., Turk, R., Kugler, G. & Peruš, I. Neural network analysis of the influence of chemical composition on surface cracking during hot rolling of AISI D2 tool steel. Comput. Mater. Sci. 42, 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2007.09.009 (2008).

Wang, Z. et al. Achieving high hardness and wear resistance in phase transition reinforced DC53 die steel by laser additive manufacturing. Surf. Coat. Technol. 462, 129474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.129474 (2023).

Hassan, S. et al. Parametric analysis and multi-objective optimization for machining complex features on D2 and DC53 steels for tooling applications. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 33, 12109–12123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-024-09828-2 (2024).

Lin, K.-W. & Chang, Y.-C. Use of the Taguchi method to optimize an immunodetection system for quantitative analysis of a rapid test. Diagnostics 11, 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11071179 (2021).

Seshaiah, S. et al. Optimization on material removal rate and surface roughness of stainless steel 304 wire cut EDM by response surface methodology. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6022550 (2022).

Kumar, R. Effect of peak current on the performance of WEDM. IOSR 03, 22–28. https://doi.org/10.9790/1684-15010030322-28 (2016).

Azam, M. et al. Parametric analysis of recast layer formation in wire-cut EDM of HSLA steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 87, 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-8518-3 (2016).

Saha, P. et al. Multi-objective optimization in wire-electro-discharge machining of TiC reinforced composite through Neuro-Genetic technique. Appl. Soft Comput. 13, 2065–2074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2012.11.008 (2013).

Zhu, X., Li, G., Mo, J. & Ding, S. Electrical discharge machining of semiconductor materials: A review. J. Market. Res. 25, 4354–4379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.06.202 (2023).

Singh, M. A. et al. Influence of open voltage and servo voltage during Wire-EDM of silicon carbides. Proc. CIRP 95, 285–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2020.02.305 (2020).

Naeim, N., AbouEleaz, M. A. & Elkaseer, A. Experimental investigation of surface roughness and material removal rate in wire EDM of stainless steel 304. Materials 16, 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16031022 (2023).

Dabade, U. A. & Karidkar, S. S. Analysis of response variables in WEDM of Inconel 718 using Taguchi technique. Proc. CIRP 41, 886–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.01.026 (2016).

Jesudas, T. & Arunachalam, R. Study on influence of process parameter in micro-electrical discharge machining (μ-EDM). Eur. J. Sci. Res. 59, 115–122 (2011).

Bhaumik, M. & Maity, K. Effect of different tool materials during EDM performance of titanium grade 6 alloy. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 21, 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2018.04.018 (2018).

Ishfaq, K. et al. Optimization of WEDM for precise machining of novel developed Al6061-7.5% SiC squeeze-casted composite. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 111, 2031–2049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-06218-5 (2020).

Hassan, S. et al. Investigation on tool wear mechanisms and machining tribology of hardened DC53 steel through modified CBN tooling geometry in hard turning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 127, 547–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-11528-5 (2023).

Kumar, B. K. & Das, V. C. Study and optimisation of WEDM parameters of AISI P20+Ni using RSM and hybrid deep neural network. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 9, 1299–1327. https://doi.org/10.1080/2374068X.2022.2116533 (2023).

Biswas, S. et al. Multi-material modeling for wire electro-discharge machining of Ni-based superalloys using hybrid neural network and stochastic optimization techniques. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 41, 350–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirpj.2022.12.005 (2023).

Suvarna, M. et al. Predicting biodiesel properties and its optimal fatty acid profile via explainable machine learning. Renew. Energy 189, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.02.124 (2022).

Raj, A. et al. Performance analysis of WEDM during the machining of Inconel 690 miniature gear using RSM and ANN modeling approaches. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 62, 20220288. https://doi.org/10.1515/rams-2022-0288 (2023).

Adedeji, W. O. et al. Optimization of the wire electric discharge machining process of nitinol-60 shape memory alloy using Taguchi-Pareto design of experiments, grey-wolf analysis, and desirability function analysis. IJIEM 4, 28. https://doi.org/10.22441/ijiem.v4i1.18087 (2023).

Sana, M. et al. Sustainable electric discharge machining using alumina-mixed deionized water as dielectric: Process modelling by artificial neural networks underpinning net-zero from industry. J. Clean. Prod. 441, 140926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140926 (2024).

Goyal, A., Gautam, N. & Pathak, V. K. An adaptive neuro-fuzzy and NSGA-II-based hybrid approach for modelling and multi-objective optimization of WEDM quality characteristics during machining titanium alloy. Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 16659–16674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-06261-7 (2021).

Afridi, S. A., Younas, M., Khan, Z. & Khan, A. M. Investigating wire electric-discharge machining (WEDM) parameters for improved machining of D2 steel: A multi-objective optimization study. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 26, 817–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-024-01203-4 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support from Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-702), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The authors appreciate the support from Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025–702), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sana Hassan involved in conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, formal analysis. Muhammad Asad took part in methodology, visualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft. Muhammad Sana involved in methodology, software, visualization, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. Anamta Khan executing machine learning and NSGA-II optimization. Muhammad Umar Farooq took part in conceptualization and writing—review & editing. Saqib Anwar involved in methodology, writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed and agreed with the final revision of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed upon the current version of the submission for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sana, M., Asad, M., Khan, A. et al. Geometric influence and multi-objective optimization of WEDM for hardened tool steels using ANN and NSGA-II. Sci Rep 15, 41723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26450-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26450-x