Abstract

The intestinal microbiota has been implicated in depression, and patients with periodontal disease show particularly high rates of depressive symptoms. This study explored the relationship between oral microbiota, depression severity, and systemic inflammatory factors. Thirty-two patients with depression were enrolled and divided into mild (n = 13; PHQ-9 ≤ 14) and major (n = 19; PHQ-9 > 14) depression groups. Significant differences in oral microbial diversity were found between groups. Alpha-diversity was higher in mild depression (Shannon, P = 0.01; Simpson, P = 0.03), although richness did not differ significantly (Chao1, P = 0.06; ACE, P = 0.06). Beta-diversity analysis revealed distinct microbial community structures (Unweighted UniFrac, P < 0.01; Weighted UniFrac, P < 0.01). Several bacterial taxa (e.g., Actinobacteria, Micrococcales, Micrococcaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Flavobacteriaceae, Rothia, Paraclostridium, Capnocytophaga, Haemophilus_parainfluenzae, and Neisseria_elongata) showed positive correlations with depression severity. In contrast, Xanthomonadales was negatively associated. No significant intergroup differences were observed in inflammatory factors. These findings suggest that oral microbiota composition and diversity are closely linked to depression severity, though the role of inflammatory factors remains unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is associated with diverse factors including lack of exercise, low educational level, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, family misfortune, viral infections and inflammatory processes1. The pathophysiology of depression involves impaired neuroplasticity, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and dopaminergic system, as well as increased neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability2. In addition, alterations in the gut microbiota, alpha- and beta-diversity, have been significantly correlated with depressive symptoms3. Individuals with mental disorders exhibit reduced richness and diversity of intestinal microbiota, along with decreased levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) of microbiota compared to healthy people4. However, Richardson found that higher microbial richness was associated with more severe depressive symptoms5. Typically, depressed patients harbor a higher abundance of pro-inflammatory microbiota and a reduced presence of anti-inflammatory, butyrate-producing microbiota. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), key components of Gram-negative bacterial membranes, activate the innate immune system and can induce depression-like behaviors3,6.

Several microbial species have been implicated in depression and inflammatory responses. For instance, Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium lactis potently alleviate depression-like behaviors by elevating brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) and serotonin levels in the brain, while reducing blood corticosterone and colonic inflammatory markers7. Lachnospiraceae is positively correlated with hippocampal BDNF expression. Conversely, it inhibits the growth of Helicobacteriaceae, Sutterellaceae, Enterobacteriaceae and Akkermansiaceae, all of which are associated with elevated hippocampal interleukin-1β (IL-1β)7. Lactococcus lactis significantly decreases tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels8.

Targeting the microbiota represents a promising therapeutic strategy for depression. Depression‑like behaviors can be induced by microbial dysbiosis and ameliorated by probiotic administration9. Antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis increases pathogenic bacteria, while reducing beneficial microbes. This shift promotes the production of harmful metabolites and inflammatory molecules, which can reach the brain via the bloodstream and vagus nerve10,11, ultimately affecting hippocampal neurogenesis and mood12. Transplantation of intestinal microbiota from depressed patients into mice elevates blood LPS levels and increases colonic expression of IL-1β and IL-613, while downregulating hippocampal BDNF and serotonin signaling, leading to depressive-like behaviors14. Conversely, fecal microbiota transplantation from healthy donors alleviates depressive behaviors and reduces inflammation in the colon and hippocampus13. Additionally, LPS treatment in mice increases the abundance of Escherichia coli, Clostridium, Salmonella, and Klebsiella, along with pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which are reversed by probiotic administration15. Probiotics can restore beneficial taxa including Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, thereby preventing and treating depression15.

The oral microbiota is predominantly composed of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria and Spirochaetes16. Although few studies have examined the oral microbiota-depression link, a high prevalence of depression is observed in patients with periodontal disease17, a condition linked to microbial dysbiosis and inflammatory cytokines18. The oral microbiota may influence neurological disorders by inducing systemic inflammation through dysbiosis19. Mental health disorders are linked to the oral microbiota by increasing pro-inflammatory cytokines in the saliva20. Depressed patients exhibit altered salivary microbial composition, including increased levels of Actinobacteria (phylum), Actionmycetales (order), Micrococcaceae (family), Rothia and Scardovia, as well as decreased levels of Fusobacteria (phylum), Fusobacteriales (order), Porphyromonadaceae, Fusobacteriaceae (family), Fusobacterium and Porphyromonas5.

Overall, microbial communities are significantly associated with depression and represent a potential therapeutic target. However, data related to the oral microbiota in depression remain limited, particularly regarding its variation with depression severity. Given that the oral microbiota is more stable than the intestinal microbiota21, and serves as a major source of bacterial transmission to the gut22, along with the ease of non-invasive saliva sampling, this study aimed to investigate the associations between depression severity, oral microbiota, and inflammatory cytokines.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional observational study enrolled patients diagnosed with depression at Beijing Tiantan hospital between January and September 2020. Participants were classified into a mild depression group (Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9 score ≤ 14) or a major depression group (PHQ-9 score > 14). Inclusion criteria were: (1) diagnosis of depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-V criteria, (2) age between 18 and 90 years. Exclusion criteria were: (1) history of other psychiatric diseases, autoimmune diseases or oral cancer, (2) history of infection, dental ulcer, oral inflammation, or use of antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, or probiotics within one month; (3) use of antidepressants within the previous 6 months. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data and sample collection

Baseline data and samples were collected through face-to-face interviews. Information collected included age, gender, education level, body mass index (BMI), marital status, employment status, tobacco and alcohol consumption, physical activity (yes/no), dietary habits, family history of mental illness, medical history, duration of depression, and PHQ-9 score. The PHQ-9 was used to assess depression severity, with scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicating mild, moderate, moderately major, and major depression, respectively23. Due to the limited sample size, participants were divided into two groups: mild (PHQ-9 ≤ 14) and major (PHQ-9 > 14) depression24.

Fasting venous blood samples were obtained, and centrifuged immediately at 3000 rpm for 20 min. Plasma aliquots were stored at −80 °C until analysis. Cytokine levels including IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-17 A, IL-17 F, TNF-α, TNF-β, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were measured using flow cytometer at Tianjin Kuangbo Tongsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China).

Saliva samples were collected after an overnight fast and gargling twice with water. Participants accumulated saliva for 1 min before providing at least 2 mL of saliva. Samples were immediately frozen at −80 °C until processing. DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (Beijing Novogene Technology Co., Ltd., China). The V3-V4 regions of the 16 S rDNA gene were amplified by PCR and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform (https://cn.novogene.com/). Purification was performed using the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany). High-quality sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) based on 97% similarity to the SILVA 138 database (http://www.arb-silva.de/).

Microbial bioinformatics and statistical analysis

Oral microbial alpha-diversity was assessed using the ACE, Chao1, Shannon and Simpson indices. Beta-diversity was evaluated using Unweighted and Weighted UniFrac distances, Principal Co-ordinates Analysis (PCoA), Principle Component Analysis (PCA) and Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS). Differential abundance of taxa was compared from phylum to species level.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation or medians (interquartile range, IQR), and analyzed using Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables were presented as counts (percentages), and analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Alpha-diversity indices were compared using the Wilcoxon test. Beta-diversity was used to compare microbial community composition between different samples. Associations between cytokines and oral microbiota were evaluated using Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of thirty-two patients with depression were included in this study. Thirteen patients (41%) were classified with mild depression and nineteen (59%) with major depression. Baseline characteristics, including age, gender, BMI, and smoking, etc. were comparable between two groups. Both groups had a higher proportion of female participants. No significant differences were observed in cytokine levels or dietary habits between the groups (Tables 1 and 2).

Sequencing data and overall microbial composition

Sequencing of the V3-V4 regions of the 16 s rDNA gene from saliva samples yielded an average of 102,010 reads per sample. After quality control, 64,409 high-quality sequences were retained, with an effective rate of 63.16% (Supplementary Table 1). A total of 2,911 OTUs were identified at 97% similarity. Taxonomic annotation rates were as follows: 97.63% at kingdom level, 87.22% at phylum level, 86.53% at class level, 82.17% at order level, 71.83% at family level, 52.22% at genus level, and 13.67% at species level (SILVA 138 database). Rarefaction curves indicated adequate sequencing depth (Supplementary Fig. 1).

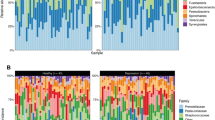

The dominant phyla across all samples were Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Fusobacteriota, and Actinobacteriota. The most abundant classes were Gammaproteobacteria, Bacteroidia, and Bacilli; the predominant orders were Bacteroidales, Burkholderiales, and Lactobacillales; the most common families were Prevotellaceae, Neisseriaceae, and Burkholderiaceae; the dominant genera were Prevotella, Neisseria, and Lautropia; and the most prevalent species were Prevotella_melaninogenica, Neisseria_mucosa, and Haemophilus_parainfluenzae (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Alpha- and beta-diversity analysis

Alpha-diversity, reflecting microbial diversity and evenness, was higher in the mild depression group than in the major depression group, as indicated by the Shannon (P = 0.01) and Simpson (P = 0.03) indices. The Simpson index of mild depression was closer to 1, indicating greater species evenness. The ACE and Chao1 indices, which estimate species richness, were also higher in the mild group, though not significantly (both P = 0.06). The PD whole tree index, representing phylogenetic diversity, did not differ between groups (P = 0.42). Good’s coverage index was near 1 in all samples, confirming sufficient sequencing depth (Fig. 1).

Beta-diversity analysis, reflecting differences in microbial community structure, revealed significant separation between the two groups. A higher Unweighted UniFrac distance indicates greater dissimilarity in species presence/absence between communities, suggesting divergent evolutionary histories. In addition, a higher Weighted UniFrac distance reflects greater differences in both species composition and their relative abundances. The mild depression group exhibited significantly higher Unweighted UniFrac distances but lower Weighted UniFrac distances compared to the major depression group (P < 0.01), suggesting that the mild depression samples harbored more distinct species, while the major depression group showed greater disparity in microbial abundance. In ordination analyses, including PCoA, PCA, and NMDS, closer sample distances indicate higher similarity in microbial composition and structure. PCoA based on Unweighted UniFrac distances showed that samples from the major depression group predominantly clustered in the negative quadrants of both coordinate axes, whereas mild depression samples clustered in the positive quadrants. PCA further indicated that species composition in the major depression group was more tightly clustered compared to the mild depression group. NMDS also confirmed distinct microbial community structures between the groups (Stress = 0.078, values < 0.2 indicate reliable representation) (Fig. 2).

Comparison of oral microbial community structure (beta-diversity) between mild depression (n = 13) and major depression (n = 19) groups. Analyses included Unweighted UniFrac, Weighted UniFrac, Principal Co-ordinates Analysis (PCoA), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS). The Unweighted UniFrac distance reflected differences in microbial presence/absence, while the Weighted UniFrac distance incorporated both phylogenetic composition and abundance. The first two principal coordinates (PC1, PC2) or multidimensional scaling axes (MDS1, MDS2) were shown, with percentages indicating the proportion of variance explained by each component. Statistical significance was assessed using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; P, P value.

Differential taxa and correlations with cytokines

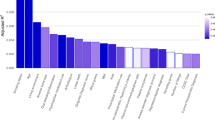

Compared to the mild depression group, the major depression group showed significantly higher relative abundances of the class Actinobacteria, order Micrococcales, families Micrococcaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Flavobacteriaceae, genera Rothia, Paraclostridium, and Capnocytophaga, and species Haemophilus_parainfluenzae and Neisseria_elongata. The mild depression group was enriched in the order Xanthomonadales (Fig. 3).

Differentially abundant bacterial taxa between patients with mild depression (n = 13) and major depression (n = 19). Bacterial taxa showing significant differences in relative abundance between groups at different taxonomic levels (class to species). Statistical significance was determined using the Wilcoxon test. PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Correlation analysis between microbial taxa and inflammatory cytokines revealed that family Peptostreptococcaceae was negatively correlated with IL-1β (R = −0.40, P = 0.02), IFN-γ (R = −0.45, P = 0.01), and IL-4 (R = −0.48, P = 0.005). The genus Paraclostridium was negatively correlated with IFN-γ (R = −0.41, P = 0.01) and TNF-β (R = −0.36, P = 0.03). However, these associations did not remain significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (adjusted significance threshold P < 0.004; Table 3).

Discussion

Our findings suggested a potential association between oral microbiota composition and depression severity, although no significant correlation was observed with systemic inflammatory cytokines. Specifically, we found that depression severity was negatively correlated with both microbial diversity and evenness in the oral cavity. Significant differences in microbial community structure were identified between patients with mild and major depression. Several taxa were up-regulated in the major depression group, including members of the class Actinobacteria, order Micrococcales, families Micrococcaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Flavobacteriaceae, genera Rothia, Paraclostridium, and Capnocytophaga, as well as species Haemophilus_parainfluenzae and Neisseria_elongata. In contrast, the order Xanthomonadales was more abundant in mild depression.

Poor oral hygiene has been proposed as a risk factor of systemic inflammation and depression25. Consistent with previous studies, we observed significant alterations in the salivary microbiota of major depression individuals. Specifically, both alpha- and beta-diversity of the oral microbiota were associated with depressive severity. A large-scale study involving 2,593 participants reported a negative correlation between gut microbial alpha-diversity and depressive symptoms26. Zeng et al. observed that healthy individuals exhibited higher Shannon, Chao, and ACE indices, along with a lower Simpson index of oral microbiota, compared to those with depression27. Zhang et al. also documented a negative association between oral microbial alpha-diversity and depression severity24. In our cohort, the mild depression group showed higher Shannon and Simpson indices than the major depression group, suggesting that microbial diversity patterns may vary not only between healthy and depressed individuals, but also across different levels of depression severity. Furthermore, previous reports have demonstrated differences in beta-diversity between healthy and depressed individuals27, as well as between mild and major depression subgroups24, which is consistent with our observation of distinct bacterial community structures between mild and major depression.

Certain oral microbiota, microbial structural components such as LPS, and metabolites including SCFAs and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) may contribute to depression through the induction of inflammatory responses25,28. Patients with depression have been shown to harbor fewer SCFA-producing bacteria29. Unlike intestinal microbiota, oral microbes may directly access the CNS via the trigeminal and olfactory nerves30. Enrichment of Actinobacteria (class)31 and Rothia (Genus) in the intestine has been significantly correlated with depressive symptoms26. Similarly, we observed an increase in oral Rothia (Genus) among patients with major depression. Rothia is positively associated with IL-832 and LPS33, and negatively correlated with BDNF, potentially influencing depressive pathogenesis34. Rothia antigens provoke immune activation, including the stimulation of lymphocytes and macrophages, as well as the promotion of B-cell differentiation, proliferation, and TNF-α production35. LPS triggers innate immune responses via Toll-like receptor 4 expressed on monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells, leading to the release of cytokines, chemokines, and interferons36. LPS can also migrate along neural pathways, accumulate in emotion-regulating brain regions, and disrupt BBB integrity30. Activation of the LPS-triggered NF-kB pathway up-regulates inflammatory cytokines37 and elevates hippocampal TNF-α, IL-1β, and corticosterone38. This cascade subsequently activates the indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase pathway and enhances glutaminergic transmission, consequently promoting depressive symptoms39. Elevated levels of anti-LPS IgM and IgA have been detected in depressed patients40. In animal models, LPS administration increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus8, inducing depressive behaviors in both animals and humans41,42. On the other hand, antidepressant treatment can reduce LPS-induced IL-6 and IL-1β in the hippocampus43.

In addition, we found that Paraclostridium (Genus) and Capnocytophaga (Genus) were more abundant in the major depression group. Paraclostridium has been linked to reduced gut microbial diversity, elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1, IL-17, IL-6), and decreased SCFA levels44. Conversely, microbial SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate) exert anti-inflammatory effects by elevating IL-10, reducing TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-645, and expanding Th17 cells, then impair intestinal barrier function35,46, reverse BBB impairment, and restore microglial function47. Propionate, in particular, mitigates LPS-induced barrier damage by suppressing oxidative and inflammatory stress28. SCFAs also participate in enteroendocrine signaling via receptor binding and neuropeptide stimulation48. Fluoxetine has been shown to modulate gut microbiota and increase SCFA production49. Previous studies have also reported an elevated abundance of Capnocytophaga in patients with depression50, a genus that has been further associated with IL-17 levels51. IL-17 inhibition can alter oral microbiota and reduce inflammation, suggesting that IL-17 may contribute to oral dysbiosis51. Haemophilus parainfluenzae, an opportunistic pathogen with anti-proliferative properties52, is also more prevalent in major depression5. Although the genus Neisseria has been positively correlated with depression25,53, some studies reported reduced abundance of Haemophilus, Rothia and Neisseria (species) in depressed young adults25, indicating that age may influence oral microbial composition. Most Neisseria and Haemophilus species are LPS produced Gram-negative bacteria, though the immunogenicity of LPS varies across bacterial strains36. Our results align with Zeng et al., who reported higher levels of Haemophilus and Neisseria in depressed individuals compared to controls27.

Despite meta-analyses providing strong evidence for elevated pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in major depressive disorder54, we found no significant differences in inflammatory markers between mild and major depression, nor correlations between cytokines and oral microbiota. This discrepancy may stem from our limited sample size or reflect dynamic immune regulation during depression onset and progression.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The small sample size may have limited statistical power and generalizability. The absence of a healthy control group and multivariate adjustments also restricts the interpretation of findings. The composition of the oral microbiota may differ between healthy individuals and those with depression, as well as between patients with mild and major depression. Future research should further investigate these associations. Furthermore, we did not collect data on oral hygiene, periodontal health, or medication use, which may confound oral microbial composition. Although we excluded participants with oral cancer, recent dental ulcer, oral infections or inflammation, unmeasured confounding factors cannot be ruled out. Finally, key mediators such as BDNF, LPS, and SCFAs were not quantified, which should be incorporated in future studies.

Conclusion

In summary, this study indicates that oral microbial diversity, evenness, and community structure are associated with depression severity. However, the role of systemic inflammatory cytokines in this relationship remains unclear and warrants further investigation in larger and well-controlled cohorts.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by Fei Liu (liufeifay@163.com), without undue reservation.

References

Sumala, S. et al. The association of HHV-6 and the TNF-α (-308G/A) promotor with major depressive disorder patients and healthy controls in Thailand. Viruses 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/v15091898 (2023).

Mousten, I. V., Sørensen, N. V., Christensen, R. H. B. & Benros, M. E. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in patients with unipolar depression compared with healthy control individuals: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 79, 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0645 (2022).

Winiarska-Mieczan, A. et al. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects of Polyphenols-Polyphenols as an element of diet therapy in depressive disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032258 (2023).

Jiang, H. Y. et al. Altered gut microbiota profile in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J. Psychiatr Res. 104, 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.07.007 (2018).

Richardson, B. N. et al. Oral Microbiome, mental Health, and sleep outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observational study in Chinese and Korean American immigrants. OMICS 27, 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2022.0182 (2023).

West, C. L. et al. Identification of SSRI-evoked antidepressant sensory signals by decoding vagus nerve activity. Sci. Rep. 11, 21130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00615-w (2021).

Ma, X. et al. Lactobacillus casei and its supplement alleviate Stress-Induced depression and anxiety in mice by the regulation of BDNF expression and NF-κB activation. Nutrients 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112488 (2023).

Ramalho, J. B. et al. Beneficial effects of Lactococcus lactis subsp. Cremoris LL95 treatment in an LPS-induced depression-like model in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 426, 113847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2022.113847 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Antibiotics-induced intestinal dysbacteriosis caused behavioral alternations and neuronal activation in different brain regions in mice. Mol. Brain. 14, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13041-021-00759-w (2021).

Hao, W. Z., Li, X. J., Zhang, P. W. & Chen, J. X. A review of antibiotics, depression, and the gut Microbiome. Psychiatry Res. 284, 112691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112691 (2020).

Joo, M. K., Shin, Y. J. & Kim, D. H. Cefaclor causes vagus nerve-mediated depression-like symptoms with gut dysbiosis in mice. Sci. Rep. 13, 15529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42690-1 (2023).

Nan, N. et al. The Microbiota-Dependent Treatment of Wuzhuyu Decoction for Chronic Migraine Model Rat Associated with Anxiety-Depression Like Behavior. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2302653. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/2302653 (2023).

Yoo, J. W. et al. The Alleviation of Gut Microbiota-Induced Depression and Colitis in Mice by Anti-Inflammatory Probiotics NK151, NK173, and NK175. Nutrients. 14. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102080

Joo, M. K. et al. Patient-derived Enterococcus mundtii and its capsular polysaccharides cause depression through the downregulation of NF-κB-involved serotonin and BDNF expression. Microbes Infect. 25, 105116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2023.105116 (2023).

Sushma, G. et al. Bifidobacterium Breve Bif11 supplementation improves depression-related neurobehavioural and neuroinflammatory changes in the mouse. Neuropharmacology 229, 109480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2023.109480 (2023).

Verma, D., Garg, P. K. & Dubey, A. K. Insights into the human oral Microbiome. Arch. Microbiol. 200, 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-018-1505-3 (2018).

Simon, G. E. & VonKorff, M. Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch. Fam Med. 4, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1001/archfami.4.2.99 (1995).

Kim, Y. R., Son, M. & Nam, S. H. Association between depressive mood and chronic periodontitis among senior residents using the National health insurance Service-Senior cohort database. J. Periodontol. 94, 742–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/jper.22-0460 (2023).

Nicholson, J. S. & Landry, K. S. Oral Dysbiosis and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Correlations and Potential Causations. Microorganisms. 10. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10071326

Simpson, C. A. et al. Oral Microbiome composition, but not diversity, is associated with adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms. Physiol. Behav. 226, 113126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113126 (2020).

Costello, E. K. et al. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326, 1694–1697. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1177486 (2009).

Schmidt, T. S. et al. Extensive transmission of microbes along the Gastrointestinal tract. Elife 8 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.42693 (2019).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Zhang, C. et al. Association of oral Microbiome diversity with depression status: NHANES 2009–2012. J. Public. Health Dent. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphd.12671 (2025).

Wingfield, B. et al. Variations in the oral Microbiome are associated with depression in young adults. Sci. Rep. 11, 15009. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94498-6 (2021).

Radjabzadeh, D. et al. Gut microbiome-wide association study of depressive symptoms. Nat. Commun. 13, 7128. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34502-3 (2022).

Zeng, Y. et al. Oral microbiota among treatment-naïve adolescents with depression: A case-control study. J. Affect. Disord. 375, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.089 (2025).

Hoyles, L. et al. Microbiome-host systems interactions: protective effects of propionate upon the blood-brain barrier. Microbiome 6, 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0439-y (2018).

Valles-Colomer, M. et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x (2019).

Singh Solorzano, C. et al. From gums to moods: exploring the impact of the oral microbiota on depression. Brain Behav. Immun. Health. 48, 101057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2025.101057 (2025).

31 Tsai, W. H. et al. Suppressive effects of Lactobacillus on depression through regulating the gut microbiota and metabolites in C57BL/6J mice induced by ampicillin. Biomedicines 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11041068 (2023).

32 Wu, B. G. et al. Severe obstructive sleep apnea is associated with alterations in the nasal Microbiome and an increase in inflammation. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 199, 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201801-0119OC (2019).

Yang, T. et al. Ellagic acid improves antioxidant capacity and intestinal barrier function of Heat-Stressed broilers via regulating gut microbiota. Anim. (Basel). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12091180 (2022).

Zhu, J. P. et al. Baihe Jizihuang Tang ameliorates chronic unpredictable mild Stress-Induced Depression-Like behavior: integrating network Pharmacology and Brain-Gut axis evaluation. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2021 (5554363). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5554363 (2021).

Schirò, G., Iacono, S. & Balistreri, C. R. The role of human microbiota in myasthenia gravis: A narrative review. Neurol. Int. 15, 392–404. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint15010026 (2023).

Oliveira, J. & Reygaert, W. C. Gram-Negative Bacteria (StatPearls, 2023).

Goeteyn, E. et al. Commensal bacteria of the lung microbiota synergistically inhibit inflammation in a three-dimensional epithelial cell model. Front. Immunol. 14, 1176044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1176044 (2023).

Majidi, J., Kosari-Nasab, M. & Salari, A. A. Developmental Minocycline treatment reverses the effects of neonatal immune activation on anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, hippocampal inflammation, and HPA axis activity in adult mice. Brain Res. Bull. 120, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.10.009 (2016).

Roman, M. & Irwin, M. R. Novel neuroimmunologic therapeutics in depression: A clinical perspective on what we know so Far. Brain Behav. Immun. 83, 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.09.016 (2020).

Evrensel, A. & Tarhan, K. N. Emerging role of Gut-microbiota-brain axis in depression and therapeutic implication. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 106, 110138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110138 (2021).

Sandiego, C. M. et al. Imaging robust microglial activation after lipopolysaccharide administration in humans with PET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 112, 12468–12473. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1511003112 (2015).

O’Connor, J. C. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol. Psychiatry. 14, 511–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4002148 (2009).

An, Q. et al. Scaffold hopping of agomelatine leads to enhanced antidepressant effects by modulation of gut microbiota and host immune responses. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 192, 172910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2020.172910 (2020).

Kutsuna, R., Tomida, J., Morita, Y. & Kawamura, Y. Paraclostridium bifermentans exacerbates pathosis in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. PLoS One. 13, e0197668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197668 (2018).

Naveed, M. et al. Gut-brain axis: A matter of concern in neuropsychiatric disorders…! Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 104, 110051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110051 (2021).

Maslowski, K. M. et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 461, 1282–1286. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08530 (2009).

Rea, K., Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. The microbiome: A key regulator of stress and neuroinflammation. Neurobiol. Stress. 4, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2016.03.001 (2016).

Rieder, R., Wisniewski, P. J., Alderman, B. L. & Campbell, S. C. Microbes and mental health: A review. Brain Behav. Immun. 66, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2017.01.016 (2017).

Egerton, S. et al. Investigating the potential of fish oil as a nutraceutical in an animal model of early life stress. Nutr. Neurosci. 25, 356–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415x.2020.1753322 (2022).

Saxena, R. et al. Assessing the effect of smokeless tobacco consumption on oral Microbiome in healthy and oral cancer patients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 841465. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.841465 (2022).

Graves, D. T., Corrêa, J. D. & Silva, T. A. The oral microbiota is modified by systemic diseases. J. Dent. Res. 98, 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034518805739 (2019).

Baraniya, D. et al. Screening of Health-Associated oral bacteria for anticancer properties in vitro. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 575656. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.575656 (2020).

Skallevold, H. E., Rokaya, N., Wongsirichat, N. & Rokaya, D. Importance of oral health in mental health disorders: an updated review. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 13, 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobcr.2023.06.003 (2023).

Tanaka, M. et al. Immune influencers in action: metabolites and enzymes of the Tryptophan-Kynurenine metabolic pathway. Biomedicines 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9070734 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the clinicians and patients involved in this project.

Funding

This study was funded by the Youth Research Funding from Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. 2018-YQN-18), the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (No. 2024-1-4112), the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (NO. L243035), and the National Key Research & Development Program of China (NO. 2016YFC1307200, No. 2020YFC2005304, No. 2022YFC2503904).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. L. collect the data and write the original draft, Y. Y. design the work, N. Z. administrate the project, S. W. collect the data, CX. W. review the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed informed consent prior to participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F., Yang, Y., Zhang, N. et al. The association of depression and oral microbiota. Sci Rep 15, 42434 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26526-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26526-8