Abstract

There is significant interest in the development of robust and simplified processes for the production of battery materials, including Li(Ni\(_{0.8}\)Mn\(_{0.1}\)Co\(_{0.1}\))O\(_2\) (NMC811), which has demonstrated high energy capacity, thermal stability and excellent electrical conductivity. This study developed a flat-flame reactor to provide a flame environment for flame spray pyrolysis (FSP), starting from an aerosolised solution of a mixture of metal nitrates in water. Preliminary studies were conducted to confirm that the operating conditions produced suitable NMC materials with acceptable performance after annealing at 750 \(^{\circ }\)C. Multiple laser diagnostic techniques were applied to characterise the spatial distribution of reactants and products and capture the process of reaction. Phase Doppler particle analysis was used to capture the droplet characteristics of precursors, and Mie scattering was used to map the instantaneous spatial distribution of droplets. A range of excitation wavelengths was tested to detect the participating species. However, only the high-energy wavelengths below 400 nm were capable of eliciting any signal. Light from a 355 nm pulsed laser was used to excite phase-selective laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (PS-LIBS) to characterise the spatial distribution of the synthesised particles arising from mixing and reaction in the high temperature zone. The excited emission from the reaction zone was spectrally characterised, as was the corresponding time signature. Finally, simultaneous Mie scattering and PS-LIBS images were obtained to capture both droplet and synthesised particle distribution, capturing the emerging reaction process. The studies show, for the first time, how emissions from the formed particles can be used as a surrogate for the progress of reaction in similar FSP systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rechargeable batteries, particularly lithium-ion batteries, have become pivotal in the use of renewable, sustainable energy. The importance of cathodes in improving battery performance has become essential when a higher specific capacity and faster charging/discharging cycles are expected.

Lithium-nickel-manganese-cobalt oxide (NMC) materials are some of the most widely used materials, considering their high specific energy capacity and attractive cost1. In particular, nickel-rich cathode materials such as Li(Ni\(_{0.8}\)Mn\(_{0.1}\)Co\(_{0.1}\))O\(_2\) (NMC811) have attracted significant attention for industrial applications, as Ni-rich layer cathode allows for high theoretical energy density and ionic conductivity2.

To produce these battery cathode materials in an efficient, economical and environmentally friendly manner, various synthesis techniques have been applied, including co-precipitation3, sol-gel4,5, hydrothermal6, spray-pyrolysis7,8 and flame spray pyrolysis9,10. Some of these methods, including flame spray pyrolysis (FSP), provide a potential approach to produce NMC in a clean and high-throughput scalable manner. Investigations have shown FSP can yield single-crystal Ni-rich cathodes with superior structural stability2, yet also produces small and fragile particles which create lower cycling durability11. However, FSP requires that precursors be available in liquid form, produces agglomerates of less controllable quality, and requires additional long-term calcination and annealing to achieve the crystallisation of expected materials12.

Zang et al9. evaluated the techno-economic feasibility of producing NMC cathode materials via flame spray pyrolysis. Compared with a traditional carbonate co-precipitation pathway, they have shown that FSP could reduce the minimum sale price of cathode material by 17% and offer lower wastewater emissions. Zhang et al13. provided an example of the production of NMC811 cathode materials via FSP with the addition of urea to improve the process. Morphology, crystal characteristics and battery performance of calcinated particles were measured by SEM, XRD and electrochemical tests. The results of the electrochemical tests showed the capability of using flame spray pyrolysis to produce NMC materials that had equal battery performance compared with commercial materials13. The study also found that the addition of urea improved the uniformity of Li distribution and shortened the required calcination time after collection. Madero et al10. optimised a FSP reactor to enable low-temperature flame spray pyrolysis (LT-FSP) to produce NMC material. Li\(_{1.2}\)(Ni\(_{0.54}\)Mn\(_{0.13}\)Co\(_{0.13}\))O\(_2\) was synthesised under reactor temperatures of 800\(\sim\)1000 K and showed a good charging/discharging battery performance. A computational study comparing LT-FSP to a flame-assisted SP system (FSP) was also conducted to support the effect of uniform temperature distribution in LT-FSP on improving material performance.

There have been a number of studies targeting the process by which aerosolised precursors are transformed into oxides or NMCs, including measurements of temperature14,15, and emission studies of metal oxides16,17. Although Chrystie18 has pointed out the necessity of conducting laser diagnostic techniques on capturing the process of synthesis, especially in flame synthesis, there have been no in situ measurements on the local distribution of precursors and species affecting the process of flame spray pyrolysis for NMC synthesis. The main purpose of this study is to explore the possibilities of applying spectroscopic techniques to identify the spatial distribution of precursor and product surrogates in the synthesis of NMC811.

Recently, phase-selective laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (PS-LIBS) was developed as an in-situ laser diagnostic technique for capturing the solid phase of synthesised particles17,19,20. PS-LIBS is atomic emission spectroscopy generated from laser-induced nanoplasma, which requires an energy intensity of the order 1 GW/cm\(^2\) with a signal duration of the order of nanoseconds21,22. An Nd:YAG laser that can operate at the second (532 nm) or third (355 nm) harmonic modes can generally serve as the excitation source for PS-LIBS. The benefit of the PS-LIBS is the selective ionisation of the particle phase, which enables the flow structures of the particles to be imaged23.

In the present study, pulsed Mie scattering is used to capture spatial distributions of precursor solution droplets, and laser-induced emission from the solid phase, which we have associated with PS-LIBS, is used to capture spatial distributions of synthesised particles. The temporal and spectral characteristics of the PS-LIBS signal are captured to validate the type of signal being taken. Finally, Mie scattering and PS-LIBS were deployed simultaneously to understand the distribution of the droplets and synthesised particles. The aim is thus to apply multiple laser diagnostic methods to flame spray pyrolysis of NMCs, and investigate the physical process of spray evaporation and the emergence of synthesize particles process of cathode materials in a flame-assisted environment.

Experimental methodology

Multiple laser diagnostic methods were employed to measure different characteristics in the reaction zone of a flame spray synthesis reactor. The 2D spatial distribution of incoming droplets is measured using scattered light from a shaped laser beam. The size distribution of droplets is measured using phase Doppler particle anemometry (PDPA). Finally, point-wise and planar PS-LIBS at 355 nm was used to capture the emission of the synthesized particles. Further details of the techniques are detailed in each section.

Flame synthesis setup

The flame-assisted spray pyrolysis system is shown in Fig. 1, consisting of three parts: the central region formed of a laminar jet of reactants, a surrounding flat flame burner which produces hot products, and a particle collection system. The inner jet consists of an inner and outer diameter ID/OD=10/13 mm quartz tube, through which air and aerosolised precursors flow. The flat flame is stabilised at a 14-mm thick ceramic perforated plate through which the jet tube protrudes 6 mm above the surface of the flat burner. The precursor droplets are generated by an jet atomiser (Omron C28P) and carried to the central zone by air through the central 10 mm tube. The mean droplet diameter was measured as 3 \(\mu\)m (PDPA, discussed in A) carried by an air flow rate of 10 slpm as metered by mass flow controllers (Alicat MC series 20 slpm with ±0.6% accuracy). The carrier air provides plenty of excess oxygen (>100 times) for oxidation of the incoming metal precursors24.

The outer flame uses methane and air premixed in proportions of 2.85 and 27.15 SLPM, respectively, to produce a stoichiometric (\(\phi =1.0\)) laminar flat flame, with adiabatic temperature of (\(T_{ad}=2170\) K), stabilized above a porous ceramic plate with internal/external diameters of ID/OD = 14 mm/100 mm. The stoichiometric condition was chosen to deliver a higher gas temperature to minimise the necessary calcination time. Nevertheless, as shown elsewhere, much longer calcination times (hours) are still necessary to produce materials of sufficient quality for batteries13,24. An outer \(D=\)100 mm quartz tube shown in Fig. 1 was used to shield the reacting region during the long-term synthesis of sample collection but removed during the application of laser diagnostics.

The precursor solution was prepared by dissolving metal nitrates (\(\ge\)97% purity, Sigma-Aldrich), including lithium nitrate (\(\mathrm LiNO_3\)), nickel nitrate hexahydrate (\(\mathrm{Ni(NO_3)_2 \cdot 6H_2O}\)), manganese nitrate hexahydrate (\(\mathrm{Mn(NO_3)_2\cdot 6H_2O}\))), and cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (\(\mathrm{Co(NO_3)_2\cdot 6H_2O}))\) in pure deionized water, with molar ratios of 1.1:0.8:0.1:0.1 for NMC811 synthesis, shown in Table 1. The molar concentration of Li was 0.55 mol/L, corresponding to 10% in excess of stoichiometry, to compensate for the loss of Li during the synthesis process. The main source of lithium loss was the decomposition of lithium carbonate that failed to react with the nickel oxide structure, while another possible reason for the loss can be the thermal decomposition of Li\(_x\)Ni\(_{2-x}\)O\(_2\)25. Flow rates of precursors of the experimental test case are provided in Table 1.

To validate the feasibility of producing NMC811 material with useful battery performance, the synthesised particles produced by flame spray pyrolysis in the above setup were annealed into NMC crystal structures and tested as battery cathodes in a half-cell.

The present study is primarily focused on the results of the optical diagnostics of the process flow. Sample characteristics were only used to confirm that suitable properties were produced in the selected FSP process. Results of the materials and battery performance characteristics of synthesised particles and annealed particles are presented in B.

Mie scattering: droplet spatial distribution

A Nano L PIV laser was used to deliver 10±0.5 mJ/pulse at 532 nm wavelength. The laser beam was shaped into a sheet of 25 mm height \(\times\) 0.1 mm thickness at the central plane of the reactor by using one concave and two convex lenses, as shown in Fig. 2. The beam exiting the laser head (diameter \(\approx\) 4 mm) was expanded by a plano-concave cylindrical lens (\(f_1\) = −25 mm) and reshaped by a plano-convex cylindrical lens (\(f_2\) = 50.8 mm) into a 50 mm height \(\times\) 4 mm thickness laser sheet. Finally, the laser sheet was focused by a planoconvex cylindrical lens (\(f_3\) = 400 mm). The final laser sheet was clipped at the edges to create a nearly top-hat intensity profile with a remaining height of 25\(\times\) 0.1 mm for the Mie scattering measurement. A knife edge was used to obtain the energy profile at the middle point and both sides of the edge. The energy intensity ratio was around 0.7(bottom):1(middle):0.7(upper), which led to a slight non-uniformity of the signal intensity vertically.

Timing was controlled by the DaVis LaVision processor timing unit (PTU), externally triggered at 10 Hz, and issuing a pulse every third image, for compatibility with the slowest camera detailed below, operating at 10/3 Hz.

Optical arrangement for imaging of Mie scattering using 532 nm, and planar and pointwise LIBS using 355 nm excitation. The setup is timed by the PTU clocked by the laser. (a) Top-view of the optical arrangement; Camera 1: Andor iXon camera for Mie scattering; Camera 2: Nanostar intensified camera for LIBS. (b) Side-view of reacting zone across centreline. A: location of pointwise PS-LIBS measured by Andor Mechelle 5000 and PMT with 355 nm excitation.

The Mie-scattered light was captured by an unintensified Andor iXon Camera (Camera 1), using a lens with a focal length of 105 mm and a \(532\pm 10\) mm band-pass filter. The imaged region is captured by a sensor of 1024 \(\times\) 1024 pixels, with a nominal pixel resolution of 25 \(\mu\)m/pixel. The camera shutter time was set to the minimum possible of 20 \(\mu\)s. Five background images were subtracted with the flame on and droplets off. Mie scattering images were obtained repetitively at different heights by tuning the height of the flame, and 500 images were collected for each 25 mm tall region, spanning the height above the burner exit (HAB) from 20 to 120 mm.

Phase-selective laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy

A preliminary series of tests was performed by scanning a laser beam produced by an optical parametric oscillator system (Coherent Horizon, tunable wavelength from 192 to 2750 nm), pumped by a tripled harmonic beam (355 nm) of a Nd:YAG laser (Coherent Surelite-III) with a pulse energy of 130 mJ, over a control volume in the area of point A in the diagram (Fig. 2) corresponding to the product region, and collecting the resulting light using a spectrometer. The scan tests showed no signal above the background baseline, except for excitation near and below the level of 355 nm, and then, the excitation seems not to be sensitive to the wavelength. Therefore, we have chosen to use light from a 355 nm beam by using a tripler on a 1064 nm laser to enable imaging of the selected synthesised region.

Laser setup

The same pulsed Nd:YAG laser (Coherent Surelite-III) with a wavelength tripler delivering 355 nm wavelength light provided approximately 130 mJ/pulse at a fixed repetitive rate of 10 Hz to produce a laser sheet across the reactant and product region. The 4 mm diameter beam was shaped into a sheet of \(\sim\)0.1 mm \(\times\)20 mm using the same group of lenses described above, one plano-concave (\(f_1=-25\) mm) and two convex UV-lenses (\(f_2=50.8\) mm and \(f_3\) = 400 mm). The position of the second lens (\(f_2=50.8\)) was slightly tuned to modify the final sheet into 20 mm height, which was clipped into the desired size (\(\sim\) 0.1 mm \(\times\) 12 mm) by blocks, with a final energy of 70 mJ per pulse, corresponding to 0.972 GW/cm\(^2\). By moving the reactor vertically, the 12 mm height frame was moved to scan the resulting signal of the synthesised particles from the bottom to the tip of the region in Fig. 2.

In all following experiments, including a local measurement for the spectral and temporal characteristics and a 2D PS-LIBS measurement for spatial distribution, the 355 nm laser setup was kept the same for a consistent configuration.

Local pointwise spectrum and signal duration measurement

The emission from the reaction region named in Fig. 2(b) as point A was excited by a 355 nm laser beam, using a spherical convex lens with focal length \(f=180\) mm. The resulting emitted spectrum from the target region (a cylindrical spot with a diameter of 3 mm and a thickness of the laser sheet\(\sim 0.1\) mm, calibrated by a fibre-based bulb) was measured using a high-resolution, wide-range Andor Mechelle 5000 spectrograph (200–975 nm calibrated by a series of fixed-wavelength light sources). A total of 200 spectral shots were hardware-accumulated onto a single spectrum in the range of 300–900 nm, after subtracting baseline emissions taken with flame on, but laser excitation off.

Time characteristics of the signal at selected wavelengths were measured from the laser pulse arrival time using a photomultiplier module (PMT, Hamamatsu, H10721-20), outfitted with a variable voltage for amplification (Hamamatsu, C10709, 2.8 to 5.0 V). Different filters (\(450\pm 20\) nm and \(670\pm 10\) nm) were used to collect specific ranges of luminescent excited emissions, once the peaks in the spectrum were identified. A silicon photodetector (Thorlabs, DET10A), was used as a trigger for the light from the pulsed laser to provide a reference time and trigger for the PMT signal, both collected using an oscilloscope (Tektronix DPO, 100 MHz, 2.5GS/s). A pulse detector, Thorlabs DET10A (1 ns rise time), was used to capture the residence of the 355 nm laser beam as a reference time by pointing it towards the laser source.

2D PS-LIBS imaging

A Nanostar intensified CCD (ICCD) (Camera 2) camera was used to detect the emission from the reacting zone at a recording frequency set to 10/3 Hz (limited by the camera chip acquisition rate). A 400 nm long-pass filter was set in front of the camera lens. The ICCD sensor was not sensitive to signals with wavelengths larger than 600 nm, so the wavelength range collected was in the range of 400 to 600 nm. The visible lens objective with a focal length of 60 mm was doubled to 120 mm by adding a teleconverter, with a maximum aperture of f/2.8 mm. The imaged region was collected over 1280 \(\times\) 1024 pixels, with a pixel resolution of 23.4 \(\mu\)m/pixel, covering a height of 24 mm by a width of 30 mm. Five background images were acquired at steady laminar conditions, without the addition of precursor droplets and averaged to be subtracted using the Nanostar ICCD camera. The background electronic noise was found to be negligible compared to the fluctuation in the signal. The camera intensifier was gated over 10 \(\mu\)s, starting at the time when the 355 nm laser was excited, and the gain ratio was set to 30/99. A total of 1000 images were collected stepwise for every 12 mm height above the burner (HAB), from HAB=20 to 120 mm.

Simultaneous 2D Mie/PS-LIBS

The setup in Sec. "Phase-selective laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy" for PS-LIBS measurements was combined with the Mie scattering setup described in Sec "Mie scattering: Droplet spatial distribution" to deliver simultaneous measurements described in Fig. 3. An Andor iXon camera (Camera 1) was used to capture Mie scattering at 10/3 Hz as described above, with a \(532\pm 10\) mm band-pass filter in front of the camera. The Nanostar ICCD camera (Camera 2) was used to capture the PS-LIBS signal at 10/3 Hz. A 500 nm short-pass filter was set in front of Camera 2 to exclude the Mie scattering signal.

Experimental setup for simultaneous Mie scattering and PS-LIBS signal collection, including triggering scheme for two cameras and Nano L PIV laser, using the clock master from the Surelite laser CL1: concave cylindrical lens; CL2 and 3: convex cylindrical lens. Camera 1: Andor iXon camera for Mie scattering; Camera 2: Nanostar camera for PS-LIBS.

The 355 nm Surelite-III laser acted as a master to trigger Cameras 1 and 2, as well as the Q-switch timing of the Nano L PIV laser. The Surelite laser provided 10 Hz 355 nm laser pulses and triggered the processor timing unit to send a new triggering signal every third pulse at 10/3 Hz. A Lavision Programmable Timing Unit (PTU) was used to conduct the signal synchronisation and take 48 pairs of images for each run at different HABs.

Results

Spectral and temporal measurements

Figure 4 presents the results of spectral measurements for excitation at 355 nm, collected at location ’A’ in Fig. 2(b). The background emission was measured to be negligible without excitation at 355 nm. Five spectra were acquired and averaged with droplets on and laser off for each condition as the background, and subtracted in the data processing procedure. No baseline broadband spectrum was detected. This allows the exclusion of either bremsstrahlung radiation26, as well as laser-induced incandescence.

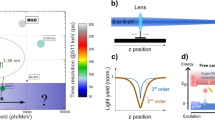

High-resolution spectral measurements of light intensity obtained at location ’A’ (Fig. 3(b)) for 355 nm-excited emission in the range of 350 to 850 nm. Emission spectrum for nickel nitrate solution (a); lithium nitrate (b); mixed NMC precursor with dashed lines corresponding to peaks in two nitrate solutions (c). (d) inset: detail of emission for NMC solution in the wavelength region of 420\(\sim\)550 nm; green and red dashed lines: peaks corresponding to top and middle plots, respectively. Markers *: Li I; **: Ni I; *** Co II.

The intensity measured in each subplot was normalised separately to its own maximum for visibility. To characterise the likely source of these two groups of peaks, two reference measurements were conducted by using single metal nitrate solutions, namely lithium nitrate and nickel nitrate. The emission spectra for the two reference solutions are plotted in Fig. 4 for (nickel)(a) and (lithium)(b) nitrate. Dashed lines with corresponding colours are also plotted in the emission spectrum of the NMC solution for ease of comparison. The overlap between coloured dashed lines and peaks in the emission of NMC precursor in Fig. 4 shows that the excited lines coincide with the spectra produced by Li and Ni individually. This is expected, as Li and Ni are added to the solution in a proportion of 55:40 (Table 1) and have larger proportions than other metals’ proportions in synthesised particles. The spectral location of peaks for Ni in the range of 440 to 550 nm is supported by previous experimental measurements27,28,29. The three peaks at 610, 670 and 690 nm are associated with Li atomic lines30. Oddly, although the latter peaks do appear in the pure lithium nitrate experiment, the extra peaks at 610 and 630 nm appear only in the NMC plots (Fig. 4(c)), even though those are both two strong lines of Li and Ni atomic spectroscopy31.

Two groups of peaks were detected in the green (430\(\sim\)550 nm) and red wavelength regions (610\(\sim\)700 nm) and listed in Table 2. The centre wavelength and FWHM of the major peaks were compared with potential lines (the rightmost column) extracted from the NIST database30,32. Based on observed wavelengths and the proportion of the NMC (Li, Ni, Mn, Co), the wavelengths were estimated for the potentially released ions, according to the Rydberg-Ritz wavelengths closest to observed wavelengths, and the estimated line origins are identified and indicated directly on Fig. 4. The signal in the green region (400\(\sim\)550 nm) appears to be much smaller than that in the red region (610\(\sim\)670 nm), which is consistent with the relative intensity of Li (3600 at 670 nm) and Ni(\(<110\) at 440\(\sim\)547 nm) on the NIST database. We note that the intensified camera used for imaging in the next section is optimised for the lower wavelengths and is unable to detect signals in the longer range for imaging purposes.

Given the high energies per pulse used (6 J/cm\(^2\), 0.972 GW/cm\(^2\) estimated by the FWHM of the laser pulse in Fig. 5), it is suggested that nanoparticles undergo ablation into free atoms. Upon direct absorption of laser photons, electrons are excited into the conduction band, initiating the ablation process and resulting in the formation of nano-plasmas. However, under these excitation conditions, impact ionisation of the surrounding gas phase is unlikely to occur, as this process typically requires a more energetic wavelength33. Consequently, this enables a phase-selective breakdown21. The phase-selective signals are shown in the next section, where the instantaneous contour of the droplet region is captured.

Time history of excited emission measured at two different wavelengths, relative to the arrival time of the exciting 355 nm laser beam. Blue: normalised time history for 355 nm collected by photon detector; red and orange lines: normalised signal intensity obtained at two different filter wavelength ranges, as collected by the PMT.

A comparison with database candidate lines was able to identify the origin of the observed emissions, with the exception of 630.6 nm lines from potential metal lines of NMC precursors. The deviation of 0.9 nm between this observed line and the closest line for Ni at 631.466 nm is significantly larger than the resolution of the Andor Mechelle 5000 spectrometer (0.1 nm) and the FWHM of the detected peak (0.41 nm). Further studies are clearly necessary to clarify the identity of this extra line.

The emitted signal duration was measured for the full NMC solution case by a Hamamatsu PMT over selected frequency ranges, as presented in Fig. 5. The emitted signal in the green and red wavelength regions was collected by the oscilloscope over two different wavelength regions centred at 450 and 670 nm, respectively, in two different sets of experiments. Signal lifetimes are of the order of the laser excitation lifetime, which is consistent with the excitation/de-excitation of electronic levels, and does not support the hypothesis of laser-induced incandescence, which is typically broadband and longer lived (hundreds of nanoseconds) for the expected nano-sized particles19.

Figure 6 shows a composite of the ensemble averages of Mie scattering and PS-LIBS images acquired separately. Fig. 6(a) shows the ensemble average of the 1000 Mie scattering signal images taken within four experiment runs where each run captured 200 images for a region of \(25\times 25\) mm. The Mie scattering images capture the spatial location of non-vaporised solution droplets. The Mie scattering intensity is corrected by dividing by the average relative energy profile calibrated in advance. Mie scattering signals are often scaled with the number of particles and the square of the particle diameter in the relevant size range. It is expected that evaporation takes place at the edges of the droplet column, decreasing both the number and size of droplets until they disappear at the top edge.

Conversely, Fig. 6(b) shows the ensemble average of the PS-LIBS images acquired for 10 identical experimental runs, where each run captured 1000 images for a region of 25 mm wide and 12 mm height, using a 400 nm long-pass filter. The narrow height band was necessary to allow sufficient energy fluence for detectable signals from PS-LIBS. The beam profile of the incoming light is not perfectly flat, leading to the striped behaviour on the edge. The images represent the signal obtained from nickel emission, as indicated in Fig. 4. The composite images show that the signal is largest just outside of the droplet vaporisation region: the precursor reactants are formed, either from calcined droplets or vaporised precursors, leading to PS-LIBS signal from the atomic lines associated with the metal, or possibly their oxides. The behaviour of simultaneous single-shot distributions of Mie and PS-LIBS signals is discussed in the next section.

Simultaneous Mie/PS-LIBS results

Figure 7 shows simultaneous images of Mie scattering (left) from incoming droplets and PS-LIBS signal (middle) associated with synthesised particles, for three different non-overlapping heights. Contours of the 10% (of the global maximum signal) region for Mie scattering (blue) and the 10% contours (red) of PS-LIBS are extracted after applying a 8\(\times\)8 px\(^2\) moving mean filter for smoothed contours.

The results show that PS-LIBS signals are only observed in the outer zone of the Mie scattering region, a pattern which can also be found in all 48 pairs of images for each height provided in the supplementary documents. This is consistent with the vaporisation and synthesis of the PS-LIBS-containing particles or vapour. There is no clear separation between the droplet region and particle region: once droplets are vaporised, synthesised particles are formed. At the bottom two heights (HAB1 and HAB2), the flow is laminar and the reaction layer containing particles has a thickness of the order of 1 mm. This suggests that the particles are formed, and do not diffuse very quickly, giving rise to a layer of incipient product particles from which the signal arises. At the higher HAB3, a flow instability arises owing to the velocity and density difference between the inner and outer flows, leading to the formation of vortices engulfing the high-temperature particle formation zone. For example, region A in Fig. 7 contains particles formed at the interface, which accumulate in a region that coincides with the negative of the droplet pattern, as the vortex wraps around and forms a recirculation zone. Recirculation zones are associated with longer residence times for the particles, which do not leave the region; we observe that there is evidence of particle clumping, suggesting agglomeration owing to higher residence time. Conversely, comparing the pattern of region B with low droplet concentration and a thin layer of particles indicates a region where the inner layer is expanding, and no recirculation zone appears, only a thin layer of particles. This is a familiar pattern from soot formation in flames34, and the process here appears to be similar.

Conclusions

A flame spray pyrolysis reactor has been built for producing battery materials of NMC811 starting from aerosolised droplet precursors delivered in a stream of micrometre-sized droplets intersecting high-temperature gases provided by the flame. Optical detection and imaging using Mie scattering of droplets and PS-LIBS of synthesised products have been employed to identify the spatial distribution and emission characteristics. The materials produced had been shown to have suitable electrochemical properties to work as Li-ion battery cathodes.

The measurements show how droplets disappear as they cross the flame, giving rise to PS-LIBS from the metals released in the process. A 355 nm blue laser was used to excite PS-LIBS of different metal ions, including well-defined lines identified with Ni and Li atoms, over the visible range, and offering lifetimes of the order of 10 ns.

Simultaneous Mie/PS-LIBS measurements of droplets and products showed that the particle products form immediately once in contact with the hot gases. A wider spatial distribution arises in regions where hot gases are entrained, suggesting that longer local residence times lead to the production and/or agglomeration of synthesis particles.

The present work has shown that it is possible to apply an image detection technique for particle formation associated with metal-containing species for FSP, clarifying where the products are formed and distributed, starting from initial aerosolised droplets. Significant further work is necessary to understand the details of particle calcination and stimulated emissions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Malik, M., Chan, K. H. & Azimi, G. Review on the synthesis of linixmnyco1-x-yo2 (nmc) cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Today Energy 28, 101066 (2022).

Chen, Y.-S., Dominko, R., Marczewski, M. & Wieczorek, W. Optimizing high-energy lithium-ion batteries: a review of single crystalline and polycrystalline nickel-rich layered cathode materials: performance, synthesis and modification. Appl. Phys. A 130, 740 (2024).

Pollen, H. N., Tolchard, J. R., Svensson, A. M. & Wagner, N. P. A single-pot co-precipitation synthesis route for ni-rich layered oxide materials with high cycling stability. ChemElectroChem 9, e202200859 (2022).

Kızıltaş-Yavuz, N. et al. Synthesis, structural, magnetic and electrochemical properties of LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2 prepared by a sol-gel method using table sugar as chelating agent. Electrochimica Acta 113, 313–321 (2013).

Engün, S., Dermenci, K. B., Savacı, U., Erdoğan, C. C. & Turan, S. Unveiling the enhanced electrochemical performance of lini0.5mn0.3co0.2o2 sol-gel coated with li-la-zr-o based gel. J. Alloy. Compd. 957, 170466 (2023).

Li, L. et al. A hydrolysis-hydrothermal route for the synthesis of ultrathin lialo 2-inlaid lini 0.5 co 0.2 mn 0.3 o 2 as a high-performance cathode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 894–904 (2015).

Li, Y., Li, X., Wang, Z., Guo, H. & Wang, J. Spray pyrolysis synthesis of nickel-rich layered cathodes LiNi1- 2xCoxMnxO2 (x= 0.075, 0.05, 0.025) for lithium-ion batteries. J. energy chemistry 27, 447–450 (2018).

Angel, S. et al. Spray-flame synthesis of lafexco1–xo3 (x = 0.2, 0.3) perovskite nanoparticles for oxygen evolution reaction in water splitting: Effect of precursor chemistry (acetates and nitrates). The J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 2564–2576 (2023).

Zang, G., Zhang, J., Xu, S. & Xing, Y. Techno-economic analysis of cathode material production using flame-assisted spray pyrolysis. Energy 218, 119504 (2021).

Madero, J. E., Li, J., Shen, K.-Y., Wojtak, J. & Axelbaum, R. L. An approach to low-temperature flame spray pyrolysis for the synthesis of temperature-sensitive materials: Application to Li1. 2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 5, 100020 (2021).

Ju, S. H., Kim, J. H. & Kang, Y. C. Electrochemical properties of LiNi0.8Co0.2-xAlxO2 (\(0<x<0.1\)) cathode particles prepared by spray pyrolysis from the spray solutions with and without organic additives. Met. Mater. Int. 16, 299–303 (2010).

Trommer, R. M. Flame spray technology : Method for production of nanopowders (2015).

Zhang, J., Muldoon, V. L. & Deng, S. Accelerated synthesis of Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 cathode materials using flame-assisted spray pyrolysis and additives. J. Power Sources 528, 231244 (2022).

Karaminejad, S., El Moussawi, A., Dreier, T., Endres, T. & Schulz, C. Multi-line oh-lif for gas-phase temperature and concentration imaging in the spraysyn burner. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 16, 100222 (2023).

Prenting, M. M., Bin Dzulfida, M. I., Dreier, T. & Schulz, C. Characterization of tracers for two-color laser-induced fluorescence liquid-phase temperature imaging in sprays. Exp. Fluids 61, 1–15 (2020).

Jüngst, N., Suedholt, B. A., Smallwood, G. J., Schulz, C. & Kaiser, S. A. Laser-induced emission from iron oxide nanoparticles in spray-flame synthesis: in situ high-speed microscopy. Appl. Phys. B 130, 63 (2024).

Stodt, M. F. et al. Phase-selective laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy in flame spray pyrolysis for iron oxide nanoparticle synthesis. Proc. Combust. Inst. 38, 1711–1718 (2021).

Chrystie, R. S. M. A Review on 1-D Nanomaterials: Scaling-Up with Gas-Phase Synthesis. The Chem. Rec. 23, e202300087 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Li, S., Ren, Y., Yao, Q. & Law, C. K. Two-dimensional imaging of gas-to-particle transition in flames by laser-induced nanoplasmas. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 023115. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4861904 (2014).

Ren, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, S. & Law, C. K. Doping mechanism of vanadia/titania nanoparticles in flame synthesis by a novel optical spectroscopy technique. Proc. Combust. Inst. 35, 2283–2289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proci.2014.05.025 (2015).

Ren, Y., Zhang, Y. & Li, S. Simultaneous single-shot two-dimensional imaging of nanoparticles and radicals in turbulent reactive flows. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 044002. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.13.044002 (2020).

Xiong, G., Li, S., Zhang, Y., Buckley, S. G. & Tse, S. D. Phase-selective laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy of metal-oxide nanoparticle aerosols with secondary resonant excitation during flame synthesis. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 31, 482–491. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5JA00186B (2016).

Kennedy, C. Flame Spray Pyrolysis: Advanced Characterisation via In-Situ Diagnostics. Ph.D. thesis, University of Sydney (2024).

Almazrouei, M. et al. Synthesis pathway of layered-oxide cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries by spray pyrolysis. ACS Appl. Mater. & Interfaces 16, 33633–33646 (2024).

McCalla, E., Carey, G. & Dahn, J. Lithium loss mechanisms during synthesis of layered Li\(_x\)Ni\(_{2-x}\)O\(_2\) for lithium ion batteries. Solid State Ionics 219, 11–19 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Novel low-intensity phase-selective laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy of tio2 nanoparticle aerosols during flame synthesis. Combust. flame 160, 725–733 (2013).

Gottwald, U. & Monkhouse, P. Preparatory study for detection of nickel in industrial flue gas by excimer laser-induced fragmentation fluorescence spectroscopy. Appl. spectroscopy 57, 117–123 (2003).

Wang, L., Zhen, J., Gao, J., Zhang, Q. & Chen, Y. Spectroscopy of nickel monosulfide in 450–560 nm by laser-induced fluorescence and dispersed fluorescence techniques. Chem. Phys. Lett. 493, 245–250 (2010).

Mishra, K. & Gopal, R. Detection of nickel-induced stress using laser-induced fluorescence signatures from leaves of wheat seedlings. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 29, 157–173 (2008).

Zaidel, A. Tables of spectral lines (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Radziemski, L. J., Engleman, R. Jr. & Brault, J. W. Fourier-transform-spectroscopy measurements in the spectra of neutral lithium, i 6 and i 7 (li i). Phys. Rev. A 52, 4462 (1995).

Meggers, W. F. Tables of Spectral-Line Intensities: Part 1: Arranged by Elements, vol. 145 (National Bureau of Standards, 1975).

Zhang, Y., Li, S., Ren, Y., Yao, Q. & Tse, S. D. A new diagnostic for volume fraction measurement of metal-oxide nanoparticles in flames using phase-selective laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Proc. Combust. Inst. 35, 3681–3688 (2015).

Geigle, K. P., Hadef, R., Stöhr, M. & Meier, W. Flow field characterization of pressurized sooting swirl flames and relation to soot distributions. Proc. Combust. Inst. 36, 3917–3924 (2017).

Hou, D., Wang, G., Gao, J. & Luo, K. H. Molecular dynamics study on evaporation of metal nitrate-containing nanodroplets in flame spray pyrolysis. Nanoscale 15, 5877–5890 (2023).

He, R. & Luo, K. H. Atomistic insights into role of urea additive in lithium nanoparticles formation. Chem. Eng. J. 497, 154822 (2024).

Abram, C. et al. Flame aerosol synthesis and electrochemical characterization of Ni-rich layered cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2, 1319–1329 (2019).

Wu, F. et al. Effect of Ni2+ content on lithium/nickel disorder for Ni-rich cathode materials. ACS applied materials & interfaces 7, 7702–7708 (2015).

Toby, B. H. & Von Dreele, R. B. What’s new in gsas-ii. Powder Diffr. 29, S2–S6 (2014).

Friedrich, F. et al. Capacity fading mechanisms of NCM-811 cathodes in lithium-ion batteries studied by X-ray diffraction and other diagnostics. J. The Electrochem. Soc. 166, A3760–A3774 (2019).

Roitzheim, C. et al. All-solid-state Li batteries with NCM-Garnet-Based composite cathodes: The impact of NCM composition on material compatibility. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5, 6913–6926 (2022).

Huang, Z.-D. et al. Microscopically porous, interconnected single crystal LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 cathode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 10777–10784 (2011).

Zhao, J. et al. In situ probing and synthetic control of cationic ordering in Ni-Rich layered oxide cathodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1601266 (2017).

Qian, G. et al. Single-crystal nickel-rich layered-oxide battery cathode materials: synthesis, electrochemistry, and intra-granular fracture. Energy Storage Mater. 27, 140–149 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Turn “waste” into wealth: A facile reviving strategy for degraded ni-rich lini0. 8co0. 1mn0. 1o2 cathodes. Ind. & Eng. Chem. Res. 61, 141–151 (2021).

Babulal, L. M. et al. Enhanced performance of a ni-rich lini0. 8co0. 1mn0. 1o2 cathode material formed through taylor flow synthesis and surface modification with li2moo4. Chem. Eng. J. 413, 127150 (2021).

Hong, C. et al. Revealing the correlation between structural evolution and li+ diffusion kinetics of nickel-rich cathode materials in li-ion batteries. J. materials chemistry A 8, 8540–8547 (2020).

Nanthagopal, M. et al. Nitrogen-doped carbon-coated li [ni0. 8co0. 1mn0. 1] o2 cathode material for enhanced lithium-ion storage. Appl. Surf. Sci. 492, 871–878 (2019).

Shen, Y. et al. A highly promising high-nickel low-cobalt lithium layered oxide cathode material for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 597, 334–344 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Sulki Park for assistance with battery performance testing.

Funding

Yutao Zheng and Lee Weller are both funded under EPSRC UK Award EP/T015845/1 for Mechanisms and Synthesis of Materials for Next-Generation Lithium Batteries using Flame Spray Pyrolysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., L.W. and J.W. conducted experiments. Y.Z. and S.H. wrote the main manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Jili Wei is currently employed by Springer Nature at the time of submission of the article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

A Phase Doppler Particle Anemometer (PDPA) measurements

Droplet measurements were undertaken at 20 mm above the exit of the central tube using a PDPA (Dantec Dynamics), deploying two crossed beams of a 514.5 nm cw laser at a 500 mm focal length transmitting probe. Data rates were of the order of \(10^3\) to \(10^4\) data points per second, which were sufficient to yield droplet size distributions.

Figure 8 shows the detected size distribution of droplet diameter pdf(d) and velocity pdf\((u_d)\) collected by PDPA above the exit under the mass flow rate of the jet in Table 1. The apparent mode of the diameter of droplets was around 2.3 \(\mu\)m, with a corresponding mean diameter (d1) of 3 \(\mu\)m and the corresponding Sauter mean diameter (SMD) of droplets of 5.60 \(\mu\)m. However, the true mode of the droplets is likely significantly smaller, as the sensitivity of the PDPA decreases quickly below 1 \(\mu\)m. This means that the SMD is not likely to be much affected, but the mode and first moment are somewhat overestimated. The measured mean velocity of droplets was around 1.7 m/s, which is slightly smaller than the mean bulk velocity of the gas phase (2 m/s). PDPA measurements downstream of the droplet region showed no significant signal, indicating that the synthesised particle diameters are too small to be measurable using the PDPA technique.

B Sample characteristics and battery performance

Around 0.8\(\sim\)1 g synthesised micro-particles were collected by a glass fibre filter for 1.5 hrs (Whatman GF/F, 110 mm diameter), shown in Fig. 1. The collected material was placed in an alumina crucible and annealed in a tube furnace. The furnace temperature was increased to the target temperature at a ramping rate of 5 \(^\circ\)C/min to the final temperature (750 to 850 \(^\circ\)C), maintained for 9 h, after which the sample was removed and allowed to cool naturally.

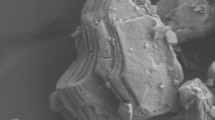

Particle morphology and crystal characteristics were characterised before and after calcination using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), and elemental composition was obtained via energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). The lithium signal could not be obtained given the limited voltage range of the beam (15 kV).

Phase identification of the immediately collected synthesised samples, and annealed samples were measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD). A Cu source was used, and the \(k\beta\) was removed via a Nickel Filter before the detector, leaving only the \(k\alpha 1\) (1.54060 Å) and \(k\alpha 2\) (1.54443 Å) wavelengths. XRD results were processed by software GSAS-II to acquire crystal characteristics of the synthesised sample.

B.1 SEM results

Figure 9 shows SEM images of the collected samples for the test case in Table 1 before calcination, shown at two different magnifications. Two different structures of samples arise, pure spheres and folded spheres. Prior to calcination, there are a number of smooth spheres of the order of 3 \(\mu\)m in diameter, a dimension close to the mode of maximum pdf of droplet sizes in Fig. 8. The molecular dynamic simulation work by Luo et al35,36. suggests that metal nitrates, except for Li, form an empty shell during calcination after the water evaporates, owing to differential diffusion, reaction and thermodynamic properties, and that is consistent with the observations. For calcinated samples, Fig. 9(b) shows that the larger spheres are coated with smaller crystal structures, probably lithium compounds that have precipitated. The shell in turn may inhibit the further evaporation of the remaining water, which may collapse to irregular shapes when particles pass through the flame.

SEM images of synthesised samples of the case in Table 1 before and after calcination. Left column: synthesised particles before calcination (a) (c) magnified 6 times; right column: synthesised particles after calcination (a) (d) magnified 6 times.

B.2 EDX results

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was used to measure the ratio of metal (Ni, Mn and Co) in the synthesised samples and calcinated samples, and compared with the target ratio of 8:1:1, shown in Table 3. In general, the measured ratio of Ni:Co:Mn is close enough to the expected ratio of 8:1:1 within an acceptable error. Table 3 also shows that the proportion of Mn appears to increase after the calcination process, which results from that the annealing process increases the Mn content at the surface by diffusion within the particle37.

B.3 XRD results

XRD results for calcinated samples are able to reveal the crystal structures, such as the crystal size, levels of the mixing between different metals and mean d-spacing between different layers. Figure 10 shows XRD results of synthesised samples and calcinated samples for the test case. After 9 h of calcination, peaks of NMC811 begin to appear, implying the formation of a layered crystalline structure. Two peak pairs (006)/(012) and (018)/(110) split, suggesting cation ordering and a full lithiation process under high temperature.

The ratio of peaks I(003)/I(104) represents the cation mixing level of \(\mathrm Li^+/Ni^{2+}\), and a higher ratio corresponds to a higher mixing level, leading to a more uniform layer distribution between \(\mathrm Li\) and \(\mathrm Ni\). Ni atoms can occupy the Li layer since \(\mathrm {Ni^{2+}}\) and \(\mathrm {Li^+}\) share similar atomic radii, resulting in the formation of disordered phases. \(\mathrm I(003)/I(104)\) reaches 1.43 in the test case, which is an acceptable level of good battery performance13,38. A high value of peak ratio (003)/(104) means a low ion exchange level of \(\mathrm {Ni^{2+}}\) and \(\mathrm {Li^+}\) in layered structure metal oxides, which is conducive to good cycling performance.

Rietveld refinement was conducted to refine the crystal characteristics of calcinated samples through GSAS-II. Structural parameters of calcinated crystals calculated by using Rietveld refinement via GSAS-II39 are presented in Table 4. The XRD patterns in Fig. 10 show that the diffraction peaks of calcinated samples can be indexed based on the hexagonal \(\alpha\)-NaFeO\(_2\) type, defining a metal oxide layered structure with an R-3mH(#166) space group with no impurity phases40,41.

The ratio of lattice parameters c to a (c/a) is commonly used to indicate the tetragonal distortion of the NMC samples42. A larger value of c/a indicates a better ordering of the hexagonal layered structure43, indicating higher purity44 and a better expected battery performance13.

B.4 Battery performance

The charging and discharging process of the battery test has been conducted on the calcinated sample of the test case. The performance curves are shown in Fig. 11.

Three characteristics of battery performances for the Case in Table 1 in the first and second cycles with a charge/discharge rate of 0.1 C are listed in Table 5. The charging and discharging capacity of the first order has reached the level of a commercial NMC811 battery45,46. However, the Coulombic Efficiency (CE), defined as the ratio of discharging capacity to charging capacity, is only 80.9%. The low CE value is dominated by the slow Li-ion diffusion kinetics of the H1 phase in highly lithiated states47, which is mainly caused by insufficient lithium vacancies and narrow layer space. Therefore, the working voltage of the NCM811 electrode quickly reaches the cut-off voltage at the end of discharge, and there is not enough time for the full recovery of the H1 phase, leading to a loss of discharge capacity and low initial CE.

Nevertheless, the battery performance is sufficient to show the feasibility of producing NMC electrode materials with performance comparable with commercial materials, which show charge capacity of the first cycle in the range of 195\(\sim\)206 mAh/mg45,46,48,49. Further analysis using laser diagnostics is representative of future FSP processes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Wei, J., Weller, L. et al. Laser diagnostic investigation on flame-assisted spray synthesis of NMC811 battery materials. Sci Rep 15, 42426 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26673-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26673-y