Abstract

This study introduces a non‑invasive approach for neurovisual classification of geometric shapes by capturing and decoding laser‑speckle patterns reflected from the human striate cortex. Using a fast digital camera and deep neural networks (DNN), we demonstrate that each visual stimulus - rectangle, triangle, mixed shapes, or blank screen, arouses a detectably distinct speckle pattern. Our optimized DNN classifier achieved near perfect recall (98%) for rectangles and high recall (91%) for triangles in single‑shape trials and sustained robust performance (82% recall) when multiple shapes appeared simultaneously. Circular stimuli produced subtler and less reliable speckle dynamics and were not classified with consistent accuracy. By leveraging low‑cost optics and scalable AI processing, this technique paves the way for real‑time, portable monitoring of visual cortex activity, offering transformative potential for cognitive neuroscience, brain-machine interfaces, and clinical assessment of visual processing. Future work will expand stimulus complexity, optimize model architectures, and explore multimodal neurophotonic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The occipital lobe, located at the posterior region of the human brain, contains the visual cortex, which is closest to the scalp1,2,3. This area is involved in the processing of visual information. It plays a pivotal role in visual perception, including processing of various visual features, such as color, shape, motion, and depth4,5,6. The surface of the occipital cortex, forming a part of the cerebral cortex, positioned near the back of the head, has a folded structure with ridges and grooves2,5,6.

The striate cortex, also known as the primary visual cortex or the V1, is located in the occipital lobe and is closest to the scalp among the visual cortical areas2,6,7,8. It is located toward the back of the occipital cortex near the occipital pole, which is the farthest point on the brain’s surface. V1 is responsible for the early stages of the visual stimuli processing, such as basic feature extraction and orientation tuning9,10. V1 receives input from the retina and plays a critical role in the initial visual processing, serving as a key entry point for visual information into the cortical visual system10,11,12,13,14.

Sensing the activity of the occipital lobe, particularly during visual processing, typically requires neuroimaging, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), or magnetoencephalography (MEG)5,15,16. These non-invasive methods allow observation of the neural activity in the occipital cortex. However, the methods are expensive, requiring specialized equipment, such as fMRI scanners or MEG systems, as well as trained professionals to operate and interpret the data17,18,19,20.

Investigation of the human brain and visual cortex activity using laser speckle pattern analysis has emerged as a promising non-invasive neuroimaging technique21,22,23,24,25,26.

Speckle patterns are generated by a laser beam reflected from a rough surface, such as human skin. The speckle patterns, captured from the brain surface by a fast digital camera and further processed, could infer information about the blood flow and brain activity21,22,23. This technique has been used to study visual cortex activity in response to visual stimuli, such as visual evoked potentials (VEPs), and has shown potential in providing high-resolution, real-time imaging of cortical dynamics related to visual processing24,25. Compared to other neuroimaging techniques, like fMRI or positron emission tomography (PET), the laser speckle imaging (LSI) is relatively cheaper and more efficient in terms of data acquisition and processing26,27,28,29,30. Spatiotemporal characteristics of backscattered speckle patterns, could gain insights into the dynamics of blood flow variation and neural activity in the visual cortex, providing a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of visual perception and cognitive processes23,31,32,33,34.

A speckle pattern is a physical phenomenon resulting from the self-interference of coherent light waves with the same frequency but varying phases and amplitudes. The resulting interference produces a seemingly random intensity distribution that is highly sensitive to the properties of the scattering medium. Predicting the exact speckle intensity is challenging, as it depends on factors such as surface roughness, wavelength, and illumination geometry. Of particular interest in this study are the speckle patterns captured from the far field by a defocused camera. These patterns encode information about surface micro vibrations and can be utilized for imaging both static and dynamic changes in the illuminated surface and superficial tissues35.This method is agnostic to a specific spatial speckle distribution but rather is related to dynamic changes in the pattern.

The work36 introduced a novel approach to extracting biomedical parameters by analyzing far-field speckle pattern dynamics. This method involves capturing speckle patterns using a defocused camera, where the tilting movement of the illuminated surface is translated into measurable displacements. These displacements can be efficiently extracted using correlation-based operations, enabling precise motion tracking.

The amplitude distribution of the speckles equals to the Fresnel integral performed over the random phase φ created by the surface roughness, Eq. (1):

where:

-

\(\:(x,y)\) are the coordinates in the transversal plane.

-

\(\:Z\) represents the axial coordinate.

-

\(\:\lambda\:\) is the optical wavelength.

-

\(\:\varphi\:(x,y)\) is the random phase introduced by surface roughness.

-

\(\:{Z}_{1}\) is the distance between the object and the imaging plane.

-

\(\:{A}_{m}\left({x}_{0},{y}_{0}\right)\:and\:\psi\:\left({x}_{o},{y}_{0}\right)\) define the amplitude and phase components of the speckle field.

The corresponding speckle intensity distribution, as recorded by the imaging sensor, is given by Eq. (2):

where:

-

\(\:h({x}_{0},{y}_{0})\) represents the spatial impulse response of the imaging system.

-

\(\:M\) is the inverse magnification factor of the imaging system.

-

\(\:({x}_{s},{y}_{s})\) are the coordinates in the sensor plane.

By leveraging these principles, Zalevsky et al.39 demonstrated the possibility for biometric authentication based on speckle pattern analysis. It allows to extract not only pulse rate, but also the heartbeat signature. This method exploits the unique vibrational signature induced by the cardiac activity, offering a non-contact means of physiological identification.

Our study introduces a novel method for classifying visual forms, such as triangles, rectangles, and circles, by analyzing laser speckle patterns captured from the striate cortex in the occipital lobe using deep neural networks (DNN). This approach uses the distinct spatiotemporal features of speckle patterns, influenced by the blood flow variations and neural activity, during visual processing. By applying advanced image processing and deep learning techniques to the speckle pattern videos captured from the visual cortex, the study aims to identify neural activity corresponding to the perception of different geometric shapes. This method has potential applications as a non-invasive, real-time tool in cognitive neuroscience, visual perception research, and in the clinical study of visual processing disorders.

Results

Detection of speckle-based visual cortex reaction

This study represents the first experimental setup designed to classify the speckle patterns reflected from the human visual cortex in response to visual stimuli. The experimental framework, as seen in Fig. 1, aimed to validate whether the laser speckle pattern imaging, combined with DNN data processing, could reliably classify the neural-visual brain activity caused by the observation of different geometric shapes.

Schematic and experimental setup for neurovisual classification using backscattered laser speckle patterns. (a) illustrates the system workflow: a laser is directed at the primary visual cortex (V1) while the subject views geometric shapes displayed on a monitor. Backscattered laser light from V1 is captured by a camera and processed by a computer to generate speckle patterns. A confusion matrix quantifies the classification accuracy of different visual stimuli. (b) The experimental setup. Shows the actual implementation, including the laser source, camera, and subject positioned in front of the monitor displaying visual stimuli. The green laser dot on the subject’s head marks the targeted area of the visual cortex.

Before each recording session, participants were shown a blank screen (white or black) to establish a baseline speckle pattern, ensuring the stability of neural responses and minimizing external noise. The speckle patterns were continuously recorded as the tested subjects viewed different shape stimuli. The captured videos were processed and analyzed to determine whether distinct neural responses could be extracted for different visual stimuli.

The results confirmed that the visual cortex speckle pattern imaging classification could differentiate between a structured and blank screen visual input. The model successfully classified polygonal shapes with higher accuracy, while circular shapes posed a greater challenge with low accuracy, as shown in the confusion matrix, Fig. 2a. These findings validate the feasibility of using speckle-based imaging as a non-invasive technique to monitor visual cortex activity, setting the foundation for future advancements in the laser-based detection of neural activity.

Model performance visualizations for shape classification. (a) Confusion matrix illustrating the classification performance of the trained DNN across eight shape stimulus categories. The x-axis represents the predicted labels, and the y-axis represents the actual labels. Each cell displays both the percentage and absolute count of classified instances. Diagonal cells indicate correct classifications, while off-diagonal cells show misclassifications. Color intensity corresponds to classification confidence, with orange tones indicating high accuracy and blue tones indicating lower accuracy or misclassification. (b) Class-wise performance radar charts displaying five key metrics: Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Confidence, and Balanced Accuracy, for each shape class. These charts visually highlight the relative strengths and weaknesses of the model across categories, where larger filled areas represent stronger performance.

Single-shape classification

The research was subdivided into several tasks. The first task evaluated the model’s ability to classify speckle patterns generated from the neural responses to single-shape stimuli. Each video presented the participants with a sequence of TV screens containing one geometric shape. A single circle, triangle, or rectangle was consequently displayed on a blank background (white or black). This setup ensured that neural activity, detected through the speckle pattern classification, was primarily driven by shape recognition without interference from additional visual elements.

A sample set of the three video types shown to each participant is given in Fig. 3a. As evident from the results, circular stimuli produced minimal variation in the speckle patterns, resulting in 0% precision and recall, and thus complete classification failure for both circle and multi-circle classes. This outcome is clearly visible in both the confusion matrix (Fig. 2a) and the performance radar charts (Fig. 2b), which show all metrics flat at zero for those categories.

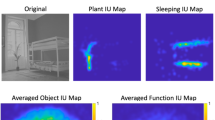

Shape Stimuli and Corresponding Correlation Metrics. (a) Correlation metric plot for single-shape stimuli, focusing on triangle stimuli, shows distinct temporal trends for Circle, Rectangle, and Triangle classes. Below, an example of a single red triangle used as the stimulus is displayed. (b) Correlation metric plot for multi-shape stimuli, with the triangle as a representative case, highlights overlapping patterns among modified shapes (M_Circle, M_Rectangle, M_Triangle). The bottom panel presents an example of multi-shape stimuli comprising triangles of various colors and orientations. (c) Correlation metric plot for mixed-shape stimuli demonstrates increased variability across all shape classes, including the baseline (White) and mixed shapes (Mix). The bottom panel depicts a sample of mixed shapes, including circles, rectangles, and triangles in multiple colors and sizes. The correlation metric represents the magnitude of speckle pattern fluctuations, with each curve corresponding to a shape class, observed over time (frames). This figure emphasizes the differences in neural responses elicited by varying visual stimuli conditions.

In contrast, rectangles and triangles yielded strong neural responses. Rectangle videos achieved 98% recall and 52.4% precision, leading to a confidence score of 0.724, although with relatively high complexity (0.476) due to the imbalance between precision and recall. Triangle videos achieved 90.9% recall and 55.6% precision, corresponding to a confidence of 0.712 and moderate complexity (0.353). The overall results are summarized in Table 1 and visualized in Fig. 2b, while the detailed per-subject results are provided in Table 2, highlight that polygonal shapes, especially rectangles and triangles, elicit more distinguishable speckle patterns compared to non-polygonal shapes like circles.

Multi-shape classification

The second task tested the model’s ability to classify speckle patterns corresponding to visual stimuli containing multiple instances of the same geometric shape. In each video, participants were shown several copies of a single shape, either triangles, rectangles, or circles, randomly positioned across the screen. This setup was designed to examine whether the repetition of a shape altered neural responses and whether the model could still differentiate between shape categories when multiple instances were simultaneously introduced. The random positioning ensured that the entire visual field was engaged, reducing potential biases related to the spatial location.

A sample set of these videos is shown in Fig. 3b. The results demonstrate varying levels of classification success across shape categories. As detailed in Table 1 and visualized in Fig. 2a and b, the multi-rectangle class achieved relatively strong performance, with 58.3% recall, 98% precision, a confidence of 0.763, and moderate complexity (0.417), indicating a higher rate of false negatives than positives.

In contrast, the multi-triangle class exhibited severe performance degradation, with only 8.3% recall and 50% precision, yielding a confidence score of 0.204 and moderate complexity (0.417). The radar chart in Fig. 2b confirms that this class lies in a low-confidence region, despite some precision.

As in the single-shape task, multi-circle classification entirely failed, showing 0% precision and recall, and no measurable complexity or confidence, highlighting the absence of distinguishable neural activation for circular stimuli even in repeated patterns.

These results suggest that while the model can generalize across repeated polygonal shapes like rectangles, it struggles with both low-saliency shapes (e.g., circles) and the added temporal variance introduced by randomly placed stimuli.

Mixed-shape classification

The third task assessed the model’s ability to classify speckle patterns generated from visual stimuli containing multiple geometric shapes presented simultaneously in each screen frame. Unlike previous tasks, where stimuli consisted of either a single shape or multiple instances of the same shape, this task introduced frames in which a random number of circles, triangles, and rectangles appeared together in random positions. This setup aimed to evaluate the neural response to complex visual scenes where different shapes coexisted within a single stimulus, testing the model’s capacity to generalize across varying shape compositions.

A sample set of these videos is shown in Fig. 3c. As expected, the speckle signals generated from blank-screen videos without shapes differ significantly from those of the mixed-shape videos. The presence of multiple shape types in each frame introduced additional complexity, requiring the model to distinguish the overlapping neural responses.

Test results showed that blank-screen videos were classified with 99% recall, confirming the model’s ability to reliably detect the absence of structured visual information. Mixed-shape videos also achieved strong performance, with a recall of 81.8% and precision of 99%, as summarized in Table 1. These findings suggest that while the neural response to complex visual stimuli introduces variability, the model was still able to extract distinguishing features from the speckle pattern data, likely leveraging shape-specific neural signals captured in previous tasks.

General observations

Before each recording session, the participants were shown both a white screen and a black (dark) screen to calibrate the session. This step ensured a stable baseline for neural activity assessment, minimizing variability in the speckle patterns caused by environmental factors or physiological fluctuations. The white-screen calibration also helped normalize the data, allowing for more accurate comparisons between shape-induced neural responses across different trials. To assess generalization, a leave-one-subject-out (LOSO) evaluation strategy revealed consistent patterns across participants.

We found that the overall model’s classification performance consistently favored polygonal shapes, particularly rectangles and triangles, which achieved high recall and confidence scores in both single-shape and multi-shape tasks (see Table 1; Fig. 2). Notably, the Mix class exhibited the best overall performance, with perfect precision, high recall (81.8%), and low complexity, indicating well-balanced, reliable predictions in complex visual scenes.

In contrast, the model completely failed to classify circle and multi-circle stimuli, with 0% precision and recall, suggesting these shapes elicited negligible or non-distinct speckle responses from the visual cortex. This trend is evident in the confusion matrix (Fig. 2a) and confirmed by the flat radar charts (Fig. 2b), where no performance metric was registered for circular categories. These findings reinforce the hypothesis that non-polygonal stimuli, such as circles, may not generate strong or differentiable neural signals in the primary visual cortex (V1), and may even be perceived similarly to the blank (white screen) condition by the model. This suggests that edge-based or angular visual features are more effectively captured through speckle-based imaging of cortical activity. Further investigation is needed to explore this potential link and to better understand how the brain encodes different geometric forms.

The classification performance for mixed-shape and blank-screen (white and black) videos was notably high, indicating that the model effectively differentiated between the presence or absence of structured visual stimuli. However, the relatively poor performance on multi-triangle and multi-circle stimuli suggests that increased complexity in the neural response may reduce classification accuracy.

These findings underscore the potential of laser speckle pattern imaging in sensing the neural dynamics related to shape recognition. However, further research is needed to refine classification models, improve sensitivity to non-polygonal shapes, and explore how neural processing of complex visual stimuli influences speckle pattern response. Future work should also investigate the role of higher-order visual processing mechanisms and their effect on the speckle patterns to enhance the robustness and interpretability of this approach.

Discussion

Role of blank-screen stimuli

The blank screen stimuli provide a critical reference point for measuring neural responses and activity in the visual cortex, forming a baseline of visual stimulation. This allows us to isolate and investigate the specific effects of visual stimuli. For example, Olman et al.37employed a white screen condition in the diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) experiments to explore the structural organization of the human visual cortex in individuals with and without visual experience. The findings demonstrated that the visual experience significantly shapes the functional connectivity of the visual cortex. Similarly38, used a white screen condition in fMRI experiments to study neural dynamics associated with the visual hallucinations in schizophrenia. They observed abnormal neural responses in the visual cortex during hallucinations compared to the white-screen condition, offering insights into the neural mechanisms underlying these phenomena.

To strengthen our control conditions, we included both a white blank screen and a black (dark) blank screen. Blank black screen baselines are commonly used in vision neuroscience39, studies show that V1 neurons often respond differently to dark versus bright stimuli, with OFF responses dominating for dark stimuli and ON responses for bright ones39. Research on black versus white blank screen luminance in human psychophysics also shows that blank screen color (black vs. white) can affect masking and scene recognition thresholds, suggesting that baselines are not interchangeable40.

In our study, the performance of the model in identifying both white and black blank-screen videos (as shown in Fig. 2) confirms its ability to reliably classify visual stimuli lacking complex features. The addition of black-screen controls helps to minimize, but not fully exclude, potential luminance and back-scatter effects. While these results increase confidence that observed dynamics arise primarily from neural responses rather than display light leakage, laser-off and phantom-head controls remain necessary for definitive validation.

This finding emphasizes the importance of using both white and black blank screen control conditions to elucidate the specific effects of structured visual stimuli on the neural activity captured via speckle imaging.

Impact of color, size and position on visual processing

The manipulation of color and screen position stimuli is crucial for investigating how these visual features are processed and encoded by the visual cortex. Both features play an important role in object recognition, spatial awareness, and scene analysis. For example, research41has revealed that distinct regions of the visual cortex are activated by different colors, suggesting specialized color-processing mechanisms. Additionally42, found that the spatial position of a stimuli influences neural responses, with specific regions of the visual cortex exhibiting sensitivity to stimuli location. We systematically varied the stimuli like color, shape, size, and position (Fig. 3). The results (Fig. 2) demonstrate how these features influenced the model’s classification accuracy. These variations provide a window into the neural mechanisms that integrate fundamental aspects of perception, advancing our understanding of visual processing.

Integration of mixed visual features

Investigating the combined processing of mixed multiple shapes, colors, and positions, enables the study of how the visual cortex integrates complex visual information. It was found43,44 that selective neural responses in the visual cortex can arise from specific combinations of shape and color, as well as the spatial relationships between stimuli. The improved classification recall for mixed multi-shape videos (80%, as shown in Table 1) suggests that the model was able to classify better the underlying patterns of integration within these stimuli. The achieved high recall for rectangle videos (98%) and triangle videos (90%) further indicates potential biases or specialized processing of polygonal shapes.

Analyzing the processing of multiple different shapes and positions on the screen provides critical insights into the visual cortex response to naturalistic visual stimuli. Studies45,46 highlighted the role of context and spatial relationships in shaping neural responses to complex objects. By systematically presenting combinations of stimuli, our study provides preliminary evidence that the DNN model, despite its simplicity, reflects some aspects of the visual cortex’s integration of complex visual scenes. This is particularly evident in its ability to distinguish mixed-shape and white-screen videos with 99% recall, as shown in Table 1, while the model struggled with other categories.

Observations on polygonal shape processing

The performance of the speckle-based DNN model across different shapes and subjects has been evaluated using detailed metrics, as shown in Tables 1 and 2, and visualized in Fig. 4. To examine these results to understand the model’s strengths and limitations, Fig. 4 presents two heatmaps that compare F1-Scores and Confidence levels across the eight subjects (S01–S08) for various shape classes; circle, multi-circle, multi-rectangle, multi-triangle, mix, rectangle, triangle, and white, including results from both white and black (dark) screen backgrounds. The F1-Score, which balances precision and recall, and the confidence, calculated as their average, provide a clear picture of how well the model performs. The Mix class shows high F1-Scores (0.855–0.920) and confidence levels (0.861–0.921) across all subjects, indicating strong ability to classify complex, multi-shape stimuli. Similarly, multi-rectangle performs well with F1-Scores (0.681–0.770) and confidence (0.718–0.786), suggesting effective recognition of multi-rectangle patterns.

Performance Metrics Across Subjects and Shapes (All Backgrounds). (a) F1-Score heatmap showing the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall for each subject and shape class, computed over trials including both white and black screen (dark) background conditions. (b) Confidence heatmap, displaying the average of Precision and Recall similarly across all background types. Values are derived from subject-wise classification data (Table 2), with color intensity indicating metric magnitude (scale: 0–0.8). Higher values reflect better model performance.

In contrast, circle and multi-circle exhibit very low F1-Scores (up to 0.048) and confidence (up to 0.048), confirming the model’s difficulty with circular shapes. This supports the idea that smooth contours may not produce enough distinct speckle dynamics at the V1 level for accurate classification. Intermediate performance was observed for Rectangle and Triangle classes, with F1-Scores ranging between 0.646 and 0.751 and confidence values between 0.668 and 0.768. The White screen condition yielded moderate F1-Scores (0.515–0.625) and confidence values (0.584–0.673). The addition of the Black screen background produced comparable results, with F1-Scores (0.523–0.627) and confidence (0.544–0.641), demonstrating that the model can differentiate between visual absence under dark versus white backgrounds. This confirms that performance is not simply driven by trivial luminance differences or leakage from the display. Nevertheless, these findings cannot substitute for direct physical controls, which will be included in future experimental refinements.

The multi-triangle class presents a challenge, with lower F1-Scores (0.028–0.204) and confidence (0.083–0.248), indicating difficulties in detecting multi-triangle patterns. This could be due to overlapping speckle signals or insufficient training data. Comparing these findings with the aggregated results in Table 1, most classes align well, though circle and multi-circle show some discrepancies, suggesting a need for refined aggregation methods or additional data.

The persistent inability to classify circular stimuli can be attributed to several interrelated factors; First, circular stimuli offer minimal edge-based transitions across frames, unlike polygons, and our SHAP saliency analysis confirms near‑zero temporal importance for circle sequences, whereas polygons show distinct high-SHAP peaks aligned with shape transitions. Second, numerous neurophysiological studies have demonstrated that V1 neurons (including simple, complex, and end‑stopped types) are strongly tuned to oriented edges, corners, and junctions, while responding weakly to smooth or isotropic contours (e.g. complex pattern selectivity in macaque V1; curvature analysis of human visual areas)47,48,49. Third, in low-signal experimental conditions a circle may appear more like a uniform white screen, which is consistent with the frequent misclassification of circle trials as White in the confusion matrix (Fig. 2a). Lastly, each stimulus class had equal trial counts, so class imbalance cannot account for the drop in circle performance.

Importantly, our choice to use a Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO) cross-validation protocol was motivated not only by the need to prevent data leakage, but also by the presence of natural inter-subject differences, such as scalp geometry, hair density, and subtle variations in laser-camera alignment. These physiological and experimental variations create meaningful differences in speckle signal characteristics between individuals. By holding out each participant entirely during testing, we ensure that our performance metrics reflect true inter-subject generalization, rather than overfitting to participant-specific signal idiosyncrasies.

Future directions

While this study provides foundational insights into the visual processing using speckle-pattern AI analysis, there are several avenues for future exploration to extend and enhance the findings.

Advanced analysis of color and shape

Future research could explore a more detailed analysis of the interactions between color and shape. By investigating how combinations of specific colors and geometric forms influence neural responses, researchers could gain deeper insights into the specialized processing mechanisms of the visual cortex. For example, examining the role of color contrast, saturation, and shape complexity might uncover nuanced patterns of neural activity that are not yet fully understood.

Adoption of more complex models

The use of more advanced machine learning architectures, such as transformers50, could significantly improve the classification and analysis of visual stimuli. Transformers, known for their ability to capture long-range dependencies and complex patterns, may offer a more nuanced understanding of how the visual cortex integrates multiple visual features. While not adopted in the current study due to data limitations and overfitting risk, this remains a promising avenue for future work. By leveraging these models, researchers could potentially uncover subtle correlations between neural signals and visual stimuli that simpler models might overlook.

Temporal dynamics and motion analysis

Incorporating temporal dynamics into the analysis, such as investigating how neural responses evolve over time in response to the moving stimuli, could provide valuable insights into the processing of dynamic visual environments. Motion analysis, coupled with speckle-pattern imaging, may help elucidate how the visual cortex integrates spatial and temporal information to construct a coherent perception of the environment.

Integration of multisensory inputs

Expanding the scope of research to include multisensory stimuli, such as visual stimuli combined with auditory or tactile inputs, could offer a broader perspective on how the brain integrates information across different sensory modalities. Understanding how the visual cortex interacts with other sensory regions may shed light on the complex interplay of neural networks during perception.

Expanding the experimental stimuli

Taken together, these research findings suggest that our speckle‑based DNN approach inherently favours edge-derived neural encoding over smooth contour processing; circular shapes likely fail to produce sufficiently distinctive speckle dynamics at the V1 level. Future studies could explore radial‑frequency distorted circles or stimuli with higher curvature to probe whether they elicit detectable speckle signals, or whether higher visual areas (e.g., V4 curvature domains) would be necessary for accurate classification51.

Incorporating more complex visual stimuli, such as natural scenes, textures, or three-dimensional shapes, could reveal how the visual cortex processes real-world stimuli. These experiments would bridge the gap between controlled laboratory tasks and naturalistic visual experiences, offering a more comprehensive understanding of neural processing.

To further affirm the robustness of the experimental setup and address potential concerns regarding signal contamination, future investigations should include additional control conditions. Specifically, these may encompass: (1) laser-off trials (with the screen active but the laser deactivated) to verify that ambient or screen light does not influence the speckle signal; and (2) phantom-head tests (employing a rubber or foam model approximating human head geometry) to exclude optical leakage from the monitor. These controls would reinforce that the observed speckle patterns originate exclusively from coherent backscattered dynamics within biological tissue, thereby enhancing the methodological reliability as outlined in the current study.

By pursuing these directions, future research could deepen our understanding of the visual cortex’s function, enhance the capabilities of the AI-powered speckle-pattern analysis, and expand its applications in both fundamental neuroscience and clinical practice.

Methods

Experimental setup

The experimental setup, Fig. 1a, comprises a green laser (770 µW, 532 nm), Basler saA1300- 200 μm area scan camera to capture the speckle patterns reflected from the laser-illuminated visual cortex of a tested individual, a TV screen to generate the visual stimuli, and a computer. Data was collected from eight healthy participants, ages 26–75, including six males and two females, in a light-isolated laboratory environment to eliminate external optical and acoustic noise. Each subject was seated at a distance of 50 cm from the camera and 120 cm from the TV screen, as shown in Fig. 1b. A custom-fitted headset stabilized each subject’s head, positioning the occipital region, where the primary visual cortex (V1) is located, directly toward the sensor. This ensured consistent optical alignment within sessions and reduced motion artifacts.

In each single continuous speckle pattern recording session, the tested subject watched eight randomized visual stimulus videos, with a fixed break between the videos. The length of each video is 100 s, with a refresh rate of one TV image per second.

The first video generated a blank screen only (white or black). The use of a blank screen as a control condition of the visual cortex experiments plays a critical role in establishing a baseline state for visual processing39,40,52,53.

The second, third, and fourth videos contained a single shape: a circle, a square, and a triangle, respectively. Every second, the color of the shape and its position on the screen changed.

The following three videos contained the same shapes in the same order, only this time each screen contained several instances of the same shape appearing in different locations and in different colors.

The eight videos contained all 3 shapes in each frame of the screen, in several instances, in different colors and positions.

A high-speed digital camera with defocused optics recorded the temporal changes of the speckle patterns, captured from the visual cortex, for 100 s of each sampling. The sampling rate was set to 200 frames per second (FPS) under the spatial resolution of 64 × 64 pixels. Data collection was performed on separate dates, with each subject recorded eight times in one continuous session. The dataset contained roughly 3.3 million frames, recorded from eight participants. Each video included metadata such as subject ID, stimulus type, and session timing. To ensure strict separation between training and testing data, we implemented a LOSO cross-validation protocol. In this approach, the model is trained on data from seven participants and evaluated on the held out eighth participant, iteratively covering all participants. This strategy prevents any frame-level overlap across training and test sets, eliminates data leakage from temporally adjacent recordings, and offers a robust measure of inter-subject generalization. Performance metrics including precision, recall, confidence, and complexity were computed for each fold.

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bar-Ilan University. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study and to permit publication of anonymized experimental images. No personal names or other identifying information are included in any figure, table, or text. The experiments were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and safety regulations.

Data preprocessing

The captured frames were extracted from each recorded video and saved as PNG files to preserve quality and prevent data loss. Each frame has a spatial resolution of 64 × 64 pixels and processed into spatio-temporal tensors for model input. For each pair of consecutive frames, we computed a two-dimensional linear cross-correlation, producing a correlation image \(\:{C}_{t}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{64\times\:64}\) that encodes local speckle displacement and preserves the spatial topology of the sensor plane. Each correlation map was normalized on a per-frame basis using the \(\:{\text{L}}_{1}\) (Manhattan) norm to reduce session-level amplitude variability while retaining relative spatial contrast, as expressed in Eq. (3) below:

The sequence of normalized maps is therefore represented as a four-dimensional tensor of shape \(\:(T,\text{\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.05em}}C=1,\text{\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.05em}}H=64,\text{\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.05em}}W=64)\), where \(\:T\) denotes the number of temporal samples (after any optional temporal down-sampling, e.g. uniform subsampling by a fixed stride). Preserving the two-dimensional spatial structure for every time step allows the subsequent model to exploit local spatial features (edges, corners, localized motion) together with their temporal evolution. Metadata (subject ID, session date, stimulus type) are retained to implement LOSO evaluation and to prevent any inadvertent mixing of frames between training and test folds.

Model

We propose an approach to process a normalized sequential speckle pattern image array using a 2D ConvLSTM layer54. This architecture integrates a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)55 layer with 2D convolution operations, allowing the model to capture both spatial and temporal dependencies within the speckle patterns. Unlike traditional LSTM layers, which transform inputs into 1D feature vectors, the ConvLSTM retains the original spatial dimensions, preserving important structural information, as shown in Fig. 5. The ConvLSTM layer is governed by the following equations:

DNN classifier architecture. A conceptual representation of the proposed neural network architecture for processing sequential speckle images using 2D ConvLSTM layers. The input to the network consists of stacks of sequential speckle signal, preserving the spatial and temporal information. Each stack is fed into a ConvLSTM cell, which integrates convolutional operations with LSTM-based temporal processing to retain the two-dimensional spatial structure of the input. The ConvLSTM layer outputs feature maps that are subsequently processed by fully connected (dense) layers for the classification task.

where:

-

\(\:*\) represents the convolution operation, which extracts spatial patterns from the input images.

-

\(\:\circ\:\) denotes the Hadamard product (element-wise multiplication), which ensures that gating mechanisms operate independently at each spatial location.

-

\(\:{X}_{t}\) is the input signal at time \(\:t\).

-

\(\:{H}_{t}\) is the hidden state (output of the ConvLSTM at time \(\:t\)).

-

\(\:{C}_{t}\) is the cell state, responsible for long-term memory retention.

-

\(\:{i}_{t},{f}_{t},\:{o}_{t}\) represent the input, forget, and output gates, respectively, controlling the flow of information.

-

\(\:\sigma\:\) is the sigmoid activation function, which scales values between 0 and 1 to regulate the influence of each gate.

-

\(\:tanh\) is the hyperbolic tangent activation function, which ensures non-linearity in the memory updates.

The ConvLSTM operates on 2D tensors, where the last dimension corresponds to the spatial dimensions of the preprocessed speckle signal. This allows the model to learn localized temporal changes in the speckle pattern without losing important details. Since ConvLSTM layers process spatially structured data, padding is applied before convolution to ensure that the hidden states maintain the same spatial dimensions as the input speckle images. This preserves the full field-of-view while allowing the model to extract meaningful features from the recorded speckle signals.

The classifier ingests sequences of 64 × 64 normalized correlation maps and processes them with stacked 2D ConvLSTM layers, with a of kernel size 3 × 3, to jointly model spatial structure and temporal dependencies. The ConvLSTM layers operate on 2D feature maps and therefore retain spatial dimensions across time, that is, they maintain the H×W layout (64 × 64) while evolving hidden and cell states temporally. After N recurrent blocks we apply global average pooling across spatial dimensions followed by two fully connected layers (256 units, ReLU) and a final SoftMax layer for multi-class classification.

The training was implemented in TensorFlow, with additional details including categorical cross-entropy as the loss function and dropout to mitigate overfitting. The Adam optimizer was used, with β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, a batch size of 64, and a learning rate of 0.001. The training was performed on a single 2080Ti GPU and took approximately 50 epochs to converge.

Conclusion

This study highlights the potential of laser speckle pattern imaging as a non-invasive, cost-effective technique for exploring neurovisual processing of geometric shapes within the human visual cortex using AI video processing. The approach demonstrated notable success in identifying polygonal shapes with sharp edges, such as triangles and rectangles, as evidenced by the high recall rates and classification accuracy as shown in Fig. 2. However, the model’s failure in accurately classifying circular shapes and its apparent bias toward polygonal shapes highlight the inherent complexity of visual processing mechanisms. These biases may reflect specialized neural dynamics or processing preferences within the visual cortex, warranting further investigation.

The findings emphasize a promise of this technique in advancing our understanding of visual perception, particularly in isolating the neural responses to specific geometric features. The results also highlight the importance of the experimental design, as observed in the systematic manipulation of visual stimuli presented in Fig. 3, and the reliability of the accuracy metrics illustrated in Table 1. Also, challenges such as data variability, the presence of noise, and the need for improved classification algorithms point to the areas requiring further refinement.

This study provides a foundational framework for using speckle pattern imaging combined with AI data processing to explore the dynamics of shape recognition and neural integration in the visual cortex. Future research should focus on optimizing the methodology, improving data analysis, and expanding the experimental scope to include more complex and diverse models and visual stimuli. By addressing these challenges, this technique could offer profound insights into the mechanisms underlying visual perception and contribute to a deeper understanding of the neural activity in humans.

Data availability

The data generated to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code is available at https://github.com/zeevikal/visual-cortex-speckle.

References

Huff, T., Mahabadi, N. & Tadi, P. Neuroanatomy, Visual Cortex. (2023).

Nehmad, O. D. The end in sight: a look at the occipital lobe. Clin. Eye Vis. Care. 10, 125–133 (1998).

Grill-Spector, K., Kourtzi, Z. & Kanwisher, N. The lateral occipital complex and its role in object recognition. Vis. Res. 41, 1409–1422 (2001).

Rehman, A. & Al Khalili, Y. Neuroanatomy, Occipital Lobe. (2023).

De Moraes, C. G. Anatomy of the visual pathways. J. Glaucoma. 22, S2–S7 (2013).

Baker, C. M. et al. A connectomic atlas of the human Cerebrum—Chapter 9: the occipital lobe. Operative Neurosurg. 15, S372–S406 (2018).

Braddick, O. Occipital Lobe (Visual Cortex): Functional Aspects. in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 10826–10828Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/03470-7 (2001).

DeYoe, E. A. et al. Imaging of the functional and dysfunctional visual system. Seminars Ultrasound CT MRI. 36, 234–248 (2015).

Leopold, D. A. Primary visual cortex: awareness and blindsight. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35, 91–109 (2012).

Tootell, R. B. H. et al. Functional analysis of primary visual cortex (V1) in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 811–817 (1998).

Siu, C. & Murphy, K. The development of human visual cortex and clinical implications. Eye Brain Volume. 10, 25–36 (2018).

Zhong, H. & Wang, R. Neural mechanism of visual information degradation from retina to V1 area. Cogn. Neurodyn. 15, 299–313 (2021).

Lee, T. S., Mumford, D., Romero, R. & Lamme, V. A. F. The role of the primary visual cortex in higher level vision. Vis. Res. 38, 2429–2454 (1998).

Van Essen, D. C., Anderson, C. H. & Felleman, D. J. Information Processing in the Primate Visual System: An Integrated Systems Perspective. Science (1979). 255, 419–423 (1992).

Bridge, H. Mapping the visual brain: how and why. Eye 25, 291–296 (2011).

Miki, A. et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of the visual system. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 12, 423–431 (2001).

Athertya, J. S. et al. Accelerated quantitative 3D UTE-Cones imaging using compressed sensing. Sensors 22, 7459 (2022).

Wood, R., Bassett, K., Foerster, Spry, C. & Tong, L. 1.5 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scanners compared with 3.0 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scanners: systematic review of clinical effectiveness. CADTH Technol. Overv. 2, e2201 (2012).

Balchandani, P. & Naidich, T. P. Ultra-High-Field MR neuroimaging. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, 1204–1215 (2015).

Wintermark, M., Sanelli, P. C., Anzai, Y., Tsiouris, A. J. & Whitlow, C. T. Imaging evidence and recommendations for traumatic brain injury: advanced Neuro- and neurovascular imaging techniques. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, E1–E11 (2015).

Draijer, M., Hondebrink, E., van Leeuwen, T. & Steenbergen, W. Review of laser speckle contrast techniques for visualizing tissue perfusion. Lasers Med. Sci. 24, 639–651 (2009).

Boas, D. A. & Dunn, A. K. Laser speckle contrast imaging in biomedical optics. J. Biomed. Opt. 15, 011109 (2010).

Dunn, A. K. Laser speckle contrast imaging of cerebral blood flow. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 40, 367–377 (2012).

Kwong, K. K. et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 89, 5675–5679 (1992).

Franceschini, M. A., Toronov, V., Filiaci, M. E., Gratton, E. & Fantini, S. On-line optical imaging of the human brain with 160-ms Temporal resolution. Opt. Express. 6, 49 (2000).

Soekadar, S. R., Kohl, S. H. & Mihara, M. Lühmann, A. Optical brain imaging and its application to neurofeedback. Neuroimage Clin. 30, 102577 (2021). von.

Giannoni, L., Lange, F. & Tachtsidis, I. Hyperspectral imaging solutions for brain tissue metabolic and hemodynamic monitoring: past, current and future developments. J. Opt. 20, 044009 (2018).

Ayaz, H. et al. Optical imaging and spectroscopy for the study of the human brain: status report. Neurophotonics 9(S2), p.S24001 (2022).

Kalyuzhner, Z. et al. Remote photonic detection of human senses using secondary speckle patterns. Sci Rep. 12(1), p.519 (2022).

Segal, N. et al. AI-powered remote monitoring of brain responses to clear and incomprehensible speech via speckle pattern analysis. J Biomed. Opt 30(6), pp.067001–067001 (2025).

Liu, Q., Wang, Z. & Luo, Q. Temporal clustering analysis of cerebral blood flow activation maps measured by laser speckle contrast imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 10, 024019 (2005).

Hong, J., Wang, Y., Chen, X., Lu, J. & Li, P. Fluctuations of Temporal contrast in laser speckle imaging of blood flow. Opt. Lett. 43, 5214 (2018).

Liu, Q. et al. Monitoring acute stroke in mouse model using laser speckle Imaging-Guided Visible-Light optical coherence tomography. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 65, 2136–2142 (2018).

Li, P., Ni, S., Zhang, L., Zeng, S. & Luo, Q. Imaging cerebral blood flow through the intact rat skull with Temporal laser speckle imaging. Opt. Lett. 31, 1824 (2006).

Dainty, J. C. Laser Speckle and Related Phenomena. 9 (Springer science & business Media, 2013).

Zalevsky, Z. et al. Simultaneous remote extraction of multiple speech sources and heart beats from secondary speckles pattern. Opt. Express. 17, 21566 (2009).

Olman, C. A. et al. Layer-Specific fMRI reflects different neuronal computations at different depths in human V1. PLoS One. 7, e32536 (2012).

Horga, G., Schatz, K. C., Abi-Dargham, A. & Peterson, B. S. Deficits in predictive coding underlie hallucinations in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 34, 8072–8082 (2014).

Xing, D., Yeh, C. I. & Shapley, R. M. Generation of Black-Dominant responses in V1 cortex. J. Neurosci. 30, 13504–13512 (2010).

Freeman, T., Loschky, L., Ringer, R., Kridner, C. & Black White, or neutral Gray blank screens have differential effects on scene gist masking. J. Vis. 10, 1251–1251 (2010).

Zeki, S. & Bartels, A. The clinical and functional measurement of cortical (in)activity in the visual brain, with special reference to the two subdivisions (V4 and V4α) of the human colour centre. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 354, 1371–1382 (1999).

Serences, J. T. & Boynton, G. M. Feature-Based attentional modulations in the absence of direct visual stimulation. Neuron 55, 301–312 (2007).

Murray, S. O., Kersten, D., Olshausen, B. A., Schrater, P. & Woods, D. L. Shape perception reduces activity in human primary visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 15164–15169 (2002).

Lescroart, M. D., Stansbury, D. E. & Gallant, J. L. Fourier power, subjective distance, and object categories all provide plausible models of BOLD responses in scene-selective visual areas. Front Comput. Neurosci. 9, p.135 (2015).

Konkle, T. & Oliva, A. Canonical visual size for real-world objects. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 37, 23–37 (2011).

Eger, E., Henson, R., Driver, J. & Dolan, R. Mechanisms of Top-Down facilitation in perception of visual objects studied by fMRI. Cereb. Cortex. 17, 2123–2133 (2007).

Tang, S. et al. Complex pattern selectivity in macaque primary visual cortex revealed by Large-Scale Two-Photon imaging. Curr. Biol. 28, 38–48e3 (2018).

Yue, X., Robert, S. & Ungerleider, L. G. Curvature processing in human visual cortical areas. Neuroimage 222, 117295 (2020).

Papale, P. et al. V1 neurons are tuned to perceptual borders in natural scenes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 121, (2024).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention Is All You Need. (2017).

Tang, R. et al. Curvature-processing domains in primate V4. Elife. 9, (2020).

Vijn, P. C. M., van Dijk, B. W. & Spekreijse, H. Visual stimulation reduces EEG activity in man. Brain Res. 550, 49–53 (1991).

Schmidt, T. T. & Prein, J. C. The Ganzfeld experience—A stably inducible altered state of consciousness: effects of different auditory homogenizations. Psych J. 8, 66–81 (2019).

Shi, X. et al. Convolutional LSTM network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015-Janua, 802–810 (2015).

Greff, K., Srivastava, R. K., Koutník, J., Steunebrink, B. R. & Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A search space odyssey. Trans. NEURAL NETWORKS Learn. Syst. 1, 1–11 (2015). arXiv:1503.04069

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.K created the models and conducted the training. All authors contributed to the design of the study, conducting the tests, interpreting the results, and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalyuzhner, Z., Agdarov, S., Beiderman, Y. et al. Visual cortex speckle imaging for shape recognition. Sci Rep 15, 42690 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26723-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26723-5