Abstract

To enhance the reliability of cable force optimization in large-span cable-stayed bridges, this study presents a force optimization model that considers reliability indicators specific to these types of bridges. A structural surrogate model was established by employing a Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN) to accurately capture the mapping relationship between random variables and the structural response. Enhancements were introduced to address the limitations of the standard Seagull Optimization Algorithm (SOA) through refracted backpropagation learning and nonlinear convergence strategies. A combined force optimization method was devised by integrating the RBFNN and the improved SOA. An empirical analysis was performed on a large-span cable-stayed bridge to validate the feasibility of the proposed approach. The results demonstrated the RBFNN’s ability to effectively capture the nonlinear mapping between structural random variables and dynamic responses. The enhanced seagull algorithm exhibited substantial performance improvements compared to the original algorithm, providing better solutions for force optimization considering reliability indicators. Following optimization, although the overall trend of tension distribution remained similar to the original distribution, adjustments were made to specific tension points to varying degrees. Notably, the deflection of the main beam in the middle span was significantly improved, with a maximum reduction of approximately 36.21%. Furthermore, there was a slight improvement in the reliability indicators for tension, with a maximum increase of approximately 9%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Effective control of cable forces is crucial in the design, construction, and operation of large-span cable-stayed bridges1. Proper distribution of cable forces is essential to meet the stress and linearity requirements of the main beam in these structures2. Various methods have been proposed to adjust cable forces3. For example, researchers have developed the “feasible region” approach, which uses the stresses of the top and bottom plates to calculate cable forces and determine the optimal bridge configuration4. Other techniques include the influence matrix method5, positive installation iterative method6, stress balance method7and stress-free state method8. However, for large-span cable-stayed bridges with many cables or asymmetric heterogeneous structures, the computational complexity of these methods becomes prohibitively high9,limiting their practical application10.Fortunately, advances in computer technology have introduced new ways to adjust cable forces swiftly using optimization algorithms8. Current leading approaches for cable force optimization include simulated annealing algorithm11,genetic algorithms12, particle swarm optimization13, response surface methodology14 and neural networks15. These techniques convert the cable force optimization problem into a mathematical model16 considering various objective functions such as bending strain energy, linear elevations, tower deflection, and stress. Computers then rapidly solve these objective functions and decision variables17.

Current research primarily focuses on adjusting cable forces to meet construction safety requirements and ensure that stress and shape parameters align with the main bridge state18. These studies typically rely on deterministic models, often overlooking the uncertain factors present during the construction of cable-stayed bridges. During construction, these bridges remain in a cantilever state, exhibiting significantly lower stiffness compared to their fully completed form19. The construction force conditions are complex and characterized by numerous uncertainties. Consequently, the risk associated with cable stayed bridges during construction generally exceeds that during the operational phase, affecting both bridge completion and operational safety. Therefore, considering cable force reliability is crucial during cable optimization for cable-stayed bridges. This consideration helps achieve construction safety control goals, reduces the probability of structural failure, enhances bridge operational reliability, and lowers operational maintenance costs. To address these issues, this paper presents a cable optimization method that incorporates cable force reliability indicators. This method uses the Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN) to capture the structural response relationship and solves the cable optimization problem using the enhanced seagull optimization algorithm. Thus, the proposed method offers a novel solution to the cable optimization problem commonly encountered in cable-stayed bridges.

Solution of reliability index based on RBFNN

Implicit function fitting based on RBFNNs

Due to the structural complexity of large-span cable-stayed bridges, their functional functions often exhibit nonlinearity and multimodality, posing challenges in providing an explicit expression for the limit state equation. Existing first-moment and second moment methods are incapable of directly calculating the reliability of implicit functions. Although the Monte Carlo method is independent of explicit functions, it suffers from inefficiency in computing the reliability of complex structures due to the requirement of a significant number of data samples. As a result, it lacks practical value in engineering applications20. To tackle this issue, the present study employs the radial basis function neural network (RBFNN) to fit the response surface of the function. By eliminating the reliance on structural, functional functions, this method constructs a surrogate model of the function through training samples, demonstrating promising applicability in high-dimensional nonlinear models of complex structures21.

RBFNN is a neural network architecture with three layers of feedforward, including the input layer, hidden layer, and output layer22. In this architecture, the in-put layer transmits variables to the hidden layer, where they undergo a nonlinear transformation before being propagated to the output layer. Subsequently, the output layer is subjected to a normalization process23. The architecture diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

The accuracy of data fitting in the hidden layer of the RBFNN heavily relies on the choice of the mapping function. This paper employs the Gaussian radial basis function as the mapping function in the hidden layer, as it effectively addresses the challenge of “dimension catastrophe” that emerges when fitting intricate functions, thereby decreasing the computational burden. The Gaussian radial basis function finds extensive application in various areas like image recognition, damage modeling, and model prediction. Equation (1) presents its mathematical representation.

Where, ui(x) is the output function of the hidden layer nodes; ci represents the center vector group of the Gaussian function; x is a set of input vectors; σ denotes the variance of the radial basis function.

To minimize the workload associated with neural network training, it is crucial to carefully select training data of superior quality. This study employed the uniform design function integrated within the DPS(Data Processing System)to iteratively generate more refined and consistent experimental design variables, as the uniform design method offers increased dimensionality and improved data uniformity. Within the MATLAB environment, the newrb function is specifically employed for the construction of the RBFNN, as demonstrated in Eq. 2.

Where,‘net’ refers to the output radial basis function network object, while ‘tr’ represents the training record structure containing relevant information about the training process. P represents the input vector matrix; T represents the output vector matrix; GOAL represents the mean squared error of the neural network; SPREAD is the spreading constant of the neural network, which controls the width of the Gaussian kernel function. The default value for SPREAD is 1, but it can be adjusted based on the desired mean squared error target, typically ranging from 0.5 to 4. MN represents the maximum number of neurons in the neural network. DF represents the number of neurons added between displays, with a default value of 25 in newrb.

The process of fitting the RBFNN function proceeds as follows: Initially, Latin hypercube sampling was applied to the initial finite element model to generate the initial training samples. Subsequently, the data was preprocessed to obtain input-output variable samples for the RBFNN. Finally, the RBFNN was utilized to fit the hidden function of the structure, and the resultant RBFNN structural surrogate model was outputted upon reaching the desired accuracy. If the desired accuracy was not achieved, training was continued for further fitting.

Solving the structural reliability index based on RBFNN

Reliability quantifies the probability of a structure successfully performing its intended function within a given time and space. Under specific circumstances, the reliability of a structure can serve as a quantitative measure of engineering structural safety. Introducing the concept of the structure’s functional function is essential for describing the reliability index of an engineering structure. Due to diverse main failure modes encountered by different structures under varying loading conditions, the corresponding functional functions vary accordingly. Assuming the presence of random variables X1, X2,…, Xn, which exert an influence on the structural reliability, the functional function of the structure can be defined as Z = G(X), as indicated in Eq. (3).

Based on the definition provided in Eq. (3), a structural function G(X) = 0 indicates that the structure is in a state of limit. On the other hand, when G(X) > 0, the structure is deemed to be in a state of reliability. Conversely, when G(X) < 0, the structure is considered to be in a state of failure.

Based on the principles of probabilistic statistics, the failure probability of the structure, denoted as Pf, is defined. The reliability index of the structure is then derived from the distribution function associated with this failure probability. Assuming that the random variables influencing the structural function are governed by a probability density function, fX(x), along with a cumulative distribution function, fX(x), the failure probability of the structure can be mathematically expressed as Eq. (4).

Obtaining the probability density function of the random variables that impact engineering structures is often difficult. Consequently, estimating the failure probability of a structure using Eq. (4) becomes challenging. To address this issue, the structural function is assumed to adhere to a normal distribution, namely Z ~ N(µz, σz). Hence, the re-liability index is defined by Eq. (5).

Where, β represents the reliability index; µz denotes the mean value; σz corresponds to the variance.

In accordance with the aforementioned theory, the RBFNN algorithm is employed to approximate the implicit function of the structure during its normal operational limit state. Subsequently, the reliability index of the structure is determined through an optimization process and the evaluation of unresolved data points. Figure 2 visually illustrates the procedure for calculating the structural reliability using RBFNN. The specific steps are as follows:

-

a.

Utilizing the original finite element model of the structure, the Latin hypercube sampling method was employed to generate a training dataset that encompasses both random variables and the corresponding structural response.

-

b.

The training samples of RBFNN were preprocessed to learn and fit the nonlinear mapping relationship between random variables and the structural response.

-

c.

The RBFNN model was evaluated to verify its adherence to the desired accuracy requirements for fitting. If the model meets the specified criteria, it is outputted. However, if the model failed to meet the requirements, additional training was performed to improve the fitting performance.

-

d.

The Monte Carlo simulation method was employed to perform importance sampling near the validation points and calculate the reliability index of the structure.

Seagull optimization algorithm based on Opposition-Based learning

Standard seagull optimization algorithm (SOA)

SOA is an intelligent optimization algorithm that leverages the migratory and foraging behaviors of seagulls within a population. Initially introduced by Gaurav Dhiman, this algorithm has undergone subsequent enhancements and refinements by numerous experts and scholars24.

SOA employs two fundamental processes in its evolution: global development and local search. Global development is achieved through the migration behavior observed in the seagull population. To prevent collisions during the migration process, an additional variable, SA, is introduced to update the positions of individual seagulls within the search space, denoted as Ps(t). This update is represented by Eq. (6):

Where, Cs(t) is the new position of an individual seagull; Cf is a constant additional variable; t represents the current iteration number of the algorithm; tmax is the maxi-mum iteration number set for the algorithm.

In addition to mitigating position collisions, each seagull within the population strives to relocate toward a more advantageous position for improved survival. This entails determining the direction between the seagull individual and the best performing individual. This relative direction, denoted by Ms(t), is precisely depicted by Eq. (8).

Where, CB is a random variable that balances global and local search; Pbs(t) represents the position of the best individual at the current iteration. rand[0,1] denotes a random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1.

Once the relative direction between the best and current individuals has been determined, each seagull within the population can update its initial position based on the optimal position direction. Consequently, it becomes crucial to ascertain the relative distance between the current and best individuals. This relative distance is represented by Ds(t), as illustrated below:

Seagull populations exhibit spiraling movements during seasonal migration and engage in predatory behavior towards other birds or organisms during flight. This predatory behavior is incorporated into the algorithm as a local search process, as depicted in Fig. 3.

This behavior can be represented in Cartesian coordinates as Eq. (11).

Where, r represents the motion radius of seagulls during spiral flight; α denotes the attack angle, with values uniformly distributed between [0, 2π]; u, v are constant parameters defining the shape of the seagull’s spiral flight.

Based on the principles, the final position of the seagull can be derived, as shown in Eq. (12).

Seagull optimization algorithm based on reverse Learning(RSOA)

Population diversity is a crucial factor influencing the performance of the intelligent swarm optimization algorithm, particularly during population initialization. Inadequate initialization strategies may necessitate more iteration steps in the algorithm’s early stages to achieve global development. The random nature of global development increases the likelihood of converging on local extrema, thereby impacting the algorithm’s subsequent local search capability. To circumvent the reduced convergence accuracy resulting from inappropriate population initialization strategies in the seagull optimization algorithm, this study proposes an Improved Seagull Optimization Algorithm Based on Reverse Learning (RSOA).The fundamental principle is illustrated in Fig. 4.

In Fig. 4, u and l represent the upper and lower boundaries of the search range symmetrically centered around the origin. If a scaling factor k is set as k = h/h*, then according to the principle of refraction and antagonistic learning, the positions of the new population can be expressed by Eq. (13)25.

Where, xij represents the position of the i-th individual seagull in the j-th dimension; xij* represents the new position of the i-th individual seagull in the j-th dimension after refraction and antagonistic learning; uj and lj are the upper and lower bounds of the search space in the j-th dimension.

The procedure for initializing the population using reverse refraction learning is as follows: firstly, randomly initialize the positions of seagull individuals within the search space; secondly, generate seagull population positions based on reverse refraction learning using Eq. (13); finally, calculate the fitness of both the new and old positions. The individuals with the highest fitness from the original seagull population are selected as the initial population.

In the standard SOA, the additional variable SA is a first order function that linearly decreases throughout the algorithm cycle. However, for high-dimensional optimization problems, there is a risk of insufficient early convergence speed, reducing the efficiency of the algorithm execution, as well as excessively fast convergence in later stages, which affects the local search capability. To address this, this paper introduced a non-linear convergence method based on sine improvement to enhance the additional variable SA of the SOA26. The improved formula is given by Eq. (15).

Where, Cf, max and Cf, min are the upper and lower limits of the control factor for the additional variable. In this paper, Cf, max and Cf, min are set as 2 and 0, respectively.

The curves representing the additional variable before and after improvement are illustrated in Fig. 5. From the figure, it was evident that during the early stages of algorithm iteration, the enhanced non-linear convergence curve, which is based on the sine function, achieved a quicker convergence. However, in the later stages of the algorithm, when the seagull population began to congregate around local extreme points, the non-linear additional variable reduced the convergence speed of the algorithm. The control algorithm emphasized local search to prevent the seagull flock from becoming trapped in local optima. The improved nonlinear additional variable significantly enhanced the algorithm’s search efficiency and convergence accuracy.

Algorithm performance testing

To verify the effectiveness of RSOA, we conducted algorithm performance testing by comparing it with the standard SOA and Improved Particle Swarm Optimization (IPSO)27. The population size (N) was set to 30, the algorithm dimensionality (D) was set to 30, and the maximum number of iterations (Tmax) was set to 500. The algorithm was independently executed 50 times. The central processor is an Intel Core i5-12400 F CPU@2.50 GHz, and the RAM is 16GB.

The performance of each algorithm was tested using 10 benchmark functions selected from CEC2019, with the basic information of these test functions shown in Table 128.

Table 2 presents the optimization results of the algorithms after 50 independent runs. From Table 2, it can be observed that for the unimodal test function F1, all algorithms converge to the theoretical optimal value, demonstrating high optimization stability. For the multimodal and multidimensional test function F2, as well as the hybrid and composite functions F3 to F10, the multi-strategy improved RSOA algorithm exhibits higher convergence accuracy and stronger optimization stability compared to other algorithms of the same type. This validates the effectiveness of the improvement strategies proposed in this study.

For a visual comparison of algorithm performance, Fig. 6 presents the convergence curves of each algorithm under different test functions.

From Fig. 6(a), it was observed that the IPSO exhibited slightly better convergence efficiency and accuracy than the SOA in the Sphere test function. However, the difference is not significant. All standard algorithms demonstrated similar convergence speeds throughout the algorithm iteration cycle. By observing the convergence curve of the improved hybrid strategy-based RSOA, a significant enhancement in its optimization capability was evident. Compared to other standard algorithms, the RSOA achieved the theoretical optimum after approximately 250 iterations, demonstrating significantly higher optimization speed and accuracy.

As shown in Fig. 6(b), for the multimodal test function Restringing, there was little difference in convergence accuracy and speed between the IPSO and SOA. Despite SOA getting entrapped in local optima prematurely, IPSO displayed a slower convergence speed. However, the RSOA demonstrated superior optimization stability. Initially, the algorithm swiftly converged to the global optimum with remarkable efficiency and eventually reached the theoretical optimum after approximately 400 iterations.

After analyzing the convergence curves of diverse test functions, it became apparent that the integration of mixed strategies exerted a positive influence on enhancing the SOA. The RSOA consistently upheld exceptional optimization performance across a range of test functions, surpassing comparable algorithms, thereby substantiating the efficacy of the improvement strategies.

Cable force optimization method based on RBFNN-RSOA under re-liability index control

Mathematical model of force optimization considering reliability index

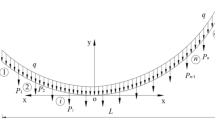

During the construction phase, cable-stayed bridges experience a combination of tensile, compressive, and bending forces. Excessive bending moments can adversely affect the structural linearity and stress distribution, emphasizing the importance of care-fully managing cable tensile forces. The bending strain energy of the main beam in cable-stayed bridges can be calculated using Eq. (16).

Where, li represents the unit length; Ei denotes the elastic modulus; Ii is the moment of inertia; MLi and MRi correspond to the bending moments at the left and right ends of the differential element, respectively.

While adjusting the cable force, it is also necessary to control the deflection of the towers in cable-stayed bridges. The deflection objective function of the tower is represented by Eq. (17).

Where, D represents the longitudinal displacement of the bridge; m is the number of offset measurement points on the bridge tower; δ signifies the displacement of the bridge tower.

Fluctuations in cable force exert a substantial influence on both the overall reliability of cable-stayed bridges and the reliability of their individual components. Focusing solely on the safety or uniformity of cable force in optimization does not provide an accurate portrayal of structural risks. To address this, the present study incorporates reliability as a constraint, requiring that the minimum reliability value of either the entire bridge or its individual components must meet prescribed criteria throughout the construction process. By referencing relevant codes and research findings, the constraint condition is expressed as Eq. (18). with the specific value β0 set at 3.728.

Where, σn, σm, and σf represent the stress values of the main beam, bridge tower, and cables, respectively. [σn], [σm], and [σf] denote the stress limits of the main beam, bridge tower, and cables, respectively.[σf] represents the cable force value considering a safety factor of 2.528.

The optimization model, derived from the objective function and constraints, can be defined as follows: minimize the bending strain energy of the main beam and the deflection of the bridge tower in a cable-stayed bridge, while simultaneously ensuring the reliability of the structural system, the stress reliability of the cables, and compliance with the stress limits of the cables. This mathematical formulation is expressed as Eq. (19).

Where, X represents the optimal combination solution for cable force.

Cable force optimization model based on RBFNN-RSOA

The optimization of cable force in long-span cable-stayed bridges was approached through the combined utilization of RBFNN and RSOA algorithms. The process for calculating the cable force optimization model based on RBFNN-RSOA is depicted in Fig. 729,30,31.

-

a.

An initial dataset was generated by constructing a finite element model of the structure in ANSYS. Following data preprocessing, the RBFNN model was trained on the MATLAB platform to yield a network model that achieves the desired accuracy.

-

b.

Parameters related to the seagull optimization algorithm were initialized. The cable force combination vector was transformed into positional coordinates within the search space, and the population size and the maximum number of iterations were determined.

-

c.

Employing the RBFNN surrogate model, the fitness value of each seagull individual was computed, thus allowing for the recording of the global optimal position within the seagull population.

-

d.

Seagull migration and attack operations were subsequently executed.

-

e.

The algorithm verified whether the termination condition had been met. If this condition was satisfied, the global optimal position was output and decoded into the optimal combination of cable force. If not, the algorithm returned to step c.

Partial pseudocode is shown in Table 3:

Engineering case study

Engineering overview and the finite element model

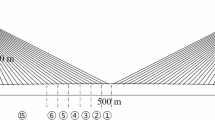

With the Nan Dongting Lake Bridge as the backdrop, the main span of the bridge measures (182 + 450 + 182) meters, making it a cable-stayed bridge featuring a double-tower, double-cable-plane semi-floating system. A total of 136 parallel inclined cables, made of steel wire with a tensile strength of 1770 MPa, are installed on the bridge. The inclined cables come in various specifications: PES7-85, PES7-109, PES7-127, PES7-151, and PES7-187. The main beam is an orthogonal anisotropic bridge deck pan-el shaped like a flat steel box beam, with a central height of 3 m and a width of 30.5 m (including the wind nozzle width). U-shaped stiffeners are positioned on the top and bot-tom plates of the bridge. The steel box beam is constructed with Q345D material, while the bridge towers are built using reinforced concrete with a concrete grade of C50. The layout of the bridge is shown in Fig. 8.

A parameterized finite element model was created using ANSYS software, while the Link10 finite element software was employed to simulate the cable system. The main beam was modeled using the BEAM188 element, and the bridge tower was represented by the SOLID65 element. To connect the cable and the “fishbone” main beam, a rigid MPC184 element was established. The constraints applied in other locations were implemented in accordance with the design drawings. The structure of the finite element model is depicted in Fig. 9. The ANSYS calculation results outlined in this paper primarily served to extract the structural response values of random variables.

Selection of random variables and determination of failure modes

Taking displacement failure as the main mode, the structural function of a long-span cable-stayed bridge was established. The function in the normal use limit state is shown in Eq. (20).

Where, [u] represents the displacement limit of the structure under the normal service limit state; U(x) denotes the maximum displacement response of the structure corresponding to the random variable.

Uncertain factors, such as material properties, load conditions, and construction errors, can impact the calculation results of the function. In this study, the elastic modulus of the inclined cable, the elastic modulus of the steel box beam, the weight, and the elastic modulus of the bridge tower concrete were treated as random variables, with structural deflection response as the output variable. The design variable ranges for the RBFNN are shown in Table 4.The parameter settings of the RBFNN are shown in Table 5.

Result analysis

To validate the fitting accuracy of the RBFNN, the finite element software was used to compute the response results of 20 validation samples. Figure 10 shows the fitting results of the RBFNN for 10 validation samples.To evaluate the accuracy of different surrogate models, the root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and mean relative error (MRE) were employed to assess the predictive performance of each model. The calculation formulas for these evaluation metrics are given in Eqs. (21)–(23).

Where,n is the total number of samples; yi is the true value; \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{y} _i}\) is the predicted value.

Within the statistical parameter interval, 20 validation samples were randomly selected. As shown in Fig. 10, the prediction results of the RBFNN demonstrate close agreement with the finite element computation results, while both the BP neural network and SVM model exhibit significant prediction deviations.Table 6 presents the accuracy validation results of different models. The data indicate that the RBFNN achieves a root mean square error (RMSE) of only 0.39, a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.30, and a mean relative error (MRE) of 2.16%. All accuracy metrics surpass those of comparable machine learning algorithms. From the accuracy indicators, it can be seen that RBFNN has achieved good fitting results, and the fitting accuracy can meet the requirements of acting as a surrogate model for cable force optimization.

Figure 11 shows the locally fitted response surface of the RBFNN surrogate model. From Fig. 11, it can be observed that the response surface is relatively smooth. As the elastic modulus of the stay cable or steel box girder increases, the attenuation of the main girder’s deflection deformation gradually decreases, revealing the coupled influence of their elastic module on the structural stiffness. The RBFNN surrogate model effectively captures the structural response patterns, providing a precise basis for response prediction in the optimization of cable forces for cable-stayed bridges.

By utilizing the response surface fitted by RBFNN as a surrogate model, the RSOA was employed to determine the optimal combination of cable forces based on the previously constructed optimization model for long-span cable-stayed bridges. The population size was set to 30, and the maximum number of iterations was set to 500 in the algorithm. The Pareto frontier distributions of the dual objectives are presented in Fig. 12. From Fig. 12, it can be observed that RSOA exhibited higher convergence accuracy in the Pareto distribution compared to both the original and improved SOA. This validates the effectiveness of the implemented improvement measures.

Table 7 presents a comparison of the efficiency of different models in cable force optimization. From Table 7, it can be seen that under the premise of using the RSOA algorithm for cable force optimization, the single iteration time of the RBFNN-based model is only 12.54 s, which is 86% lower than that of the FEM-based model. This demonstrates a significant improvement in the efficiency of cable force optimization.

Since the left and right pylons of the cable-stayed bridge are symmetrically arranged along the mid-span, and the mechanical characteristics of the front and rear double cable planes are identical, the structural analysis is conducted for the left single cable plane. The initial cable forces are determined based on the principle of minimizing the bending moment of the main girder under dead load. A finite element model of the cable-stayed bridge is established to simulate the structural dead load, and the cable forces are iteratively adjusted until the bending moment distribution at the mid-span section of the main girder becomes uniform. The optimized cable forces obtained through the RSOA algorithm are shown in Fig. 13.From Fig. 13, it is evident that the distribution trend of the optimized cable forces closely aligns with the original distribution. The maximum cable force decreased from 3266 kN to 3105 kN, while the minimum cable force increased from 1311 kN to 1350 kN. The cable force range decreased from 1955 kN to 1755 kN, indicating enhanced uniformity in cable forces.

The changes in the deflection of the main beam before and after optimization are depicted in Fig. 14. It is evident that the deflection of each controlled section significantly decreased after optimization, leading to a noticeable improvement in the overall profile of the main beam. The most substantial reduction in deflection was observed at the midspan of the main beam, where the deflection peak decreased from 0.116 m to 0.074 m, representing a maximum reduction of approximately 36.21%. Similarly, at the midspan of the edge span, the deflection was reduced from 0.089 m to 0.059 m, with a maximum reduction of approximately 33.71%. By observing the change pattern and distribution of the overall deflection of the main beam before and after optimization, it was concluded that increased tension after optimization exhibited a good control effect on the deflection of the main beam. This verifies the effectiveness of the linear control objective function in controlling the deflection of the main beam.

Due to the symmetrical distribution of the bridge structure, Fig. 15 presents the tower displacement results before and after optimization on one side of the bridge tower. As shown in Fig. 15, the tower displacement increases with the height of the tower. However, the tower displacement calculated based on the optimized cable forces is significantly improved. The displacement at the top of the tower is reduced from 35.91 cm to 16.64 cm, a decrease of approximately 53.67%, which verifies the effectiveness of the tower displacement control objective function.

The calculation results of the reliability indices for stay cables before and after optimization are shown in Fig. 16. As can be observed from Fig. 16, the reliability indices of most stay cables have improved to varying degrees after optimization. Specifically, the reliability index of stay cable L9 increased from 4.21 to 4.59, representing an improvement of 9.0%. On average, the reliability of each stay cable increased by approximately 3%, with mid-span cables showing significant improvement, while the reliability of support-point cables only slightly increased. These results verify the effectiveness of the cable force optimization scheme considering reliability indices, thereby enhancing the overall safety margin of the cable-stayed bridge structure.

Table 8 presents the measured results of the first four modal shapes of the bridge after cable force optimization. As can be seen from Table 8, as the modal order increases, the bridge’s vibration modes transition from longitudinal floating to vertical and lateral bending, with the vibration frequency gradually increasing. This reflects the vibration characteristics and frequency distribution patterns of the bridge’s various modal orders.

Discussion

Based on the improved seagull optimization algorithm and RBF neural network, this paper proposes a cable force optimization method for long-span cable-stayed bridge, which effectively improves the efficiency of solving the cable force optimization problem of cable-stayed bridge, and ensures that the internal force and linear distribution of the optimized cable-stayed bridge are more reasonable. However, at present, the modeling process of RBF neural network is a little cumbersome, and a more convenient proxy model construction method of cable-stayed bridge can be sought in the future.

Conclusions

This paper presents a force optimization model that considers the reliability index for cable-stayed bridges. The model is based on the RBFNN response surface method and the improved seagull algorithm. It effectively addresses the force optimization problem in symmetrical large-span cable-stayed bridges. In the specific context of a symmetrical large-span cable-stayed bridge project, an implicit functional approximation model is established using the RBFNN. The cable forces of the cable-stayed bridge are then optimized using the improved seagull mixed strategy optimization algorithm. The findings of this research can be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

A method for establishing a proxy model for large-span cable-stayed bridges based on RBFNN is proposed. This method accurately approximates the hidden function of the structure. Compared to the actual finite element model, the maximum relative error of the 20 test sets is only 1.32%, indicating good fitting performance.

-

(2)

The Seagull Optimization Algorithm (SOA) is enhanced by incorporating refraction reverse learning for initializing the population and employing a non-linear flight strategy. The effectiveness of the improved strategy is verified through tests using the Sphere and Restringing benchmark functions. The test results demonstrate that the RSOA outperforms both SOA and IPSO in terms of convergence speed and accuracy, validating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

-

(3)

RSOA demonstrates good adaptability in solving force optimization problems for cable-stayed bridges. Compared to SOA, RSOA exhibits better convergence effectiveness on the Pareto front and successfully addresses the force optimization problem for cable-stayed bridges while considering the reliability index.

-

(4)

Based on the engineering context of the long-span cable-stayed bridge, the findings indicate that the optimized combination of cable forces for the bridge exhibits some level of fluctuation compared to the original combination. However, the overall distribution trend of the cable forces remains largely consistent. Following the optimization process, a notable improvement in the vertical deflection of the main beam is observed. Specifically, the peak deflection at the midspan is reduced from 0.116 m to 0.074 m, representing a reduction of approximately 36.21%. Moreover, the reliability of the mid-span cable stays has significantly increased, while the improvement in the reliability of the anchor cable stays is relatively modest, with an average increase of about 3% for each cable stay. These outcomes affirm the effectiveness of the employed method.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lu, H., Fu, W., Chen, Y., Li, B. & Li, Y. Fast Cable-Force measurement for Large-Span Cable-Stayed bridges based on the alignment recognition method and Smartphone-Captured video. Buildings 14, 1941 (2024).

Li, X., Huang, X., Ding, P., Wang, Q. & Wang, Q. Research on an intelligent identification method for Cable-Stayed force with a damper based on microwave radar measurements. Buildings 14, 568 (2024).

Negrao, J. H. & J O, Simes, L. M. C. Cable Stretching Force Optimization in Cable-Stayed Bridges. //WCSMO-2 - The Second World Congress of Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization.1997.

Bin & Sun Xiao R.Optimization of dead load state in Earth-Anchored Cable-Stayed bridges. J. Harbin Inst. Technology: Engl. 22, 87–94 (2015).

Hassan, M. M., Nassef, A. O. & Damatty, A. A. E. Determination of optimum post-tensioning cable forces of cable-stayed bridges. Eng. Struct. 44, 248–259 (2012).

Danhui, D., Yanyang, C. & Bin, X. A PSO driven intelligent model updating and parameter identification scheme for Cable-Damper system. Shock Vib. 2015, 1–14 (2015).

Schemmann, A. G. & Smith, H. A. Vibration control of cable-stayed bridges—part 2: control analyses. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 27, 811–824 (1998).

Wang, Z. et al. Multiobjective optimization of cable forces and counterweights for universal cable-Stayed bridges. J. Adv. Transp. 1, 6615746 (2021).

Peng, Z. New Methods for Cable Adjustment Design of Prestressed Concrete Cable-stayed Bridge (Urban Roads Bridges & Flood Control, 2020).

Santos, C. A. N. et al. Structural optimization of Two-Girder composite Cable-Stayed bridges under dead and live loads. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 47, 939–953 (2019).

Martins, A. M., Simões, L. M. & Negrão, J. H. Cable stretching force optimization of concrete cable-stayed bridges including construction stages and time-dependent effects. Struct. Multidisciplinary Optim. 51, 757–772 (2015).

Yang-Yong, Z. Optimization of cable force for cable-Stayed bridges with ultra Kilometer span under dead loads. J. South. China Univ. Technology(Natural Sci. Edition). 37, 142–146 (2009).

Zhang, H. H. et al. Optimization of cable force adjustment in cable-Stayed Bridge considering the number of stay cable adjustment. Adv. Civil Eng. 1, 4527309 (2020).

Guo, J., Yuan, W., Dang, X. & Alam, M. S. Cable force optimization of a curved cable-stayed Bridge with combined simulated annealing method and cubic B-Spline interpolation curves. Eng. Struct. 201, 109813 (2019).

Kang Chunxia, D., Shichao, W. & Xiaoguang Comparative analysis and research on calculation methods of reasonable construction state of Cable-stayed Bridge. J. Railway Sci. Eng. 14, 87–93 (2017). (In Chinese).

Zhan Yulin, H. et al. Cable force optimization of Special-shaped cable-stayed bridges based on response surface method and particle swarm optimization. Bridge Construction 52, 16–23 (2022).

Zhang Dong, X. et al. Research on cable force optimization of Multi-tower cable-stayed Bridge based on BP neural Network-GSL&PS-PGSA. Highway Eng. 47, 34–39 (2002). (In Chinese).

Shao, Bilin & Pei Mingyang. Construction reliability optimization based on improved particle swarm optimization. Chin. J. Civil Eng. Manage. 38, 29–34 (2021). (In Chinese).

Yang Yaxun, Z. et al. Cable force optimization of tied arch Bridge based on improved particle swarm optimization. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 41, 68–73 (2022). (In Chinese).

Bjerager, P. On computation methods for structural reliability analysis. Struct. Saf. 9, 79–96 (1990).

Rai, S., Veeraraghavan, M. & Trivedi, K. S. .A survey of efficient reliability computation using disjoint products approach. Networks 25, 147–163 (2010).

Tudu, B. et al. Electronic nose for black tea quality evaluation by an incremental RBF network. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 138, 90–95 (2009).

Hu, H., Song, Y., Fan, P., Diao, C. & Cai, N. A backstepping controller with the RBF neural network for Folding-Boom aerial work platform. Complexity 1, 4289111 (2022).

Gaurav, D. & Vijay, K. Seagull optimization algorithm: theory and its applications for large-scale industrial engineering problems. Knowl. Based Syst. 165, 169–196 (2019).

LI, A. L. et al. Sparrow search algorithm combining sine-cosine and cauchy mutation. Comput. Eng. Appl. 58, 91–99 (2022). (In Chinese).

LIU, L. & HE, Q. An feature selection method based on improved grasshopper optimization algorithm. J. Nanjing Univ. (Natural Science). 56, 41–50 (2020). (In Chinese).

Sinha, A. & Jana, J. (ed P, K.) Improved affinity propagation clustering algorithms: a PSO-based approach. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 67 2 1–31 (2024).

Yufang, L. I. A. O. et al. Construction line prediction method of arch Bridge multi-stage hoisting and fastening based on IGOA-ELM. J. Highway Transp. Sci. Technol. 39, 95–105 (2012). (In Chinese).

Chen Ming, G. & Weiqi Zeng Yalin research on time-varying reliability of cable-stayed Bridge cables based on U-Kriging model [J]. Highway Eng. 49 (05), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.19782/j.cnki.1674-0610.2024.05.007 (2024).

Liu & Sikai Wang Hui improvement and experiment of SSA algorithm based on collaborative reverse learning and dynamic hierarchical management strategy [J]. Mech. Des. 42 (08), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.13841/j.cnki.jxsj.2025.08.014 (2025). 2025.08.014.

Ríos, G. M. et al. Augmented reality for learning algorithms: evaluation of its impact on students’emotions. Using Artif. Intelligence[J] Appl. Sci. 15 (14), 7745–7745 (2025).

Funding

This research was funded by National Key R&D Program (2017YFE0103000)、Guangxi Science and Technology Plan Project (Guike AB18221034) and Nanning Excellent Youth Science and Technology Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talent Cultivation Project (RC20190209).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z.(Dan Zhao). and H.W.(Hua Wang); methodology, D.Z.(Dan Zhao) and M.Y.(Mengsheng Yu); software, D.Z.; validation, H.W. and M.Y.; formal analysis, H.W.; investi-gation, D.Z., H.W. and M.Y.; writing-original draft preparation, D.Z.; writing--review and editing, D.Z., and H.W.; visualization, D.Z.; supervision, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, D., Wang, H. & Yu, M. Optimization of cable tension in large-span cable-stayed bridges based on RBF neural network and improved sea-gull algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 42725 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26763-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26763-x