Abstract

Endodontic illnesses affect around 52% of the global population and are projected to rise by 4% by 2030. Endodontic problems necessitate precise classification for treatment planning and clinical decision-making. Radiographs and expert analysis are essential to conventional diagnostic techniques; hence, automated, data-driven alternatives are required to enhance accuracy and efficiency. A modified Swin transformer with non-overlapping local windows with shifted windows in alternating layers is employed to achieve hierarchical attention mechanisms. The fixed segments of the input image are linearly embedded and converted into token representations to execute self-attention using projected query, key, and value matrices, while shifting windows and hierarchical merging facilitate extensive contextual learning. The ultimate features are subjected to global average pooling and classification via a learnable head, constituting the essence of the proposed MSViT architecture. The selection of hyperparameters for the architecture and feature selection is executed using a hybrid approach of chaotic particle swarm optimization (CPSO) and sequential quadratic programming (SQP). The proposed model is trained and assessed using an improved version of the publicly available dataset known as the root canal dataset, which includes seven categories of endodontic disorders. The suggested model, optimized using CPSO-SQP, attains an average classification accuracy of 97.72%, a mean fitness value of 2.372 × 10–11, a mean precision of 0.9749, and a mean square error of 8.2 × 10− 04, with a computational time of 867.59 s at a learning rate of 0.0001. The suggested farmwork is evaluated against pre-trained models such as ResNet-101, VGGNet-19, InceptionV3, and EfficientNet-b0, in addition to a baseline strategy based on SA-SQP, GA-SQP, and other documented results. The proposed architecture enables to learn fine-grained anatomical and pathological features, essential for distinguishing endodontic diseases in an efficient and accurate manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Worldwide, endodontic disorders such pulpitis and apical periodontitis are common dental health concerns. A thorough assessment of over 32,000 patients found that 55.7% have at least one root-filled tooth, indicating a high endodontic load1. Apical periodontitis affects 52% of people worldwide, demonstrating its prevalence2. These high prevalence rates emphasize the necessity for appropriate endodontic diagnosis and treatment. Endodontic treatments are in high demand worldwide. The market was worth USD 1.06 billion in 2021 and is expected to reach USD 1.57 billion by 2030, expanding at 4%3. This growth is driven by rising dental disease rates, endodontic technology advances, and oral health awareness. North America dominates this market because to its superior healthcare infrastructure and dental health awareness4. These changes emphasize the need to invest in endodontic research and adapt new methods to meet worldwide demand.

Endodontic disease classification (EDC) focuses on how dental pulp and periapical tissues are affected and their severity. Reversible or irreversible pulpitis, necrotic pulp, and periapical disorders such granulomas, cysts, and abscesses are common classifications5. Clinicians use radiographs and clinical signs including pain, sensitivity, and edema to diagnose illness stage and kind. Periapical X-rays and Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) show internal structural deterioration, root canal infections, and apical lesions6. Correct classification is essential for treatment planning, including root canal therapy, extraction, and monitoring. Traditionally, endodontic disease prediction relied on manual diagnostic equipment and rule-based procedures and dental professionals’ experience. Standard methods include visual inspection, thermal and electric pulp testing, and radiographic image interpretation7. Logistic regression (LR), support vector machines (SVM), decision trees (DT), and random forest (RF) classifiers have been used to diagnose patients utilizing structured patient data, clinical symptoms, and radiographic characteristics8,9. Classical methods struggle with feature engineering, generalizability, and accuracy on complicated imaging data, paving the door for data-driven modern machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches in recent years10,11,12.

Radiographic images can now accurately detect and classify endodontic diseases such pulpitis, necrotic pulp, periapical abscesses, and granulomas using deep learning. DL models especially Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) can learn hierarchical features from raw input data without feature engineering, unlike previous approaches13,14. These models can classify endodontic diseases objectively and consistently by learning small visual patterns from annotated dental radiographs or CBCT scans6. Detecting early-stage disease symptoms by human observation is difficult, but this has greatly improved diagnostic performance. Researchers use transfer learning with pre-trained models like ResNet15, VGGNet16, InceptionV313, and EfficientNet17 to improve classification accuracy and overcome the lack of huge dental datasets. These architectures, trained on ImageNet, can be fine-tuned for dental image classification, offering robust feature extraction even with minimal endodontic data. When tailored to endodontic disease diagnosis, these pre-trained models surpass classical ML in accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity18. New techniques like Grad-CAM and attention processes improve model interpretability, providing visual explanations that match clinical diagnosis and boosting trust in AI-assisted decision-making19. The dataset used in the study of EDC is publicly available20 and its few samples are provided in Fig. 1.

The proposed AI system can support dentists and endodontists by assisting in early and accurate detection of root canal disorders, reducing diagnostic variability, and improving treatment planning efficiency. By providing automated classification, the system may serve as a second opinion tool to support less experienced practitioners, improve patient outcomes, and potentially reduce the need for invasive diagnostic procedures. Moreover, the proposed architecture is especially beneficial in settings with limited access to experienced specialists, offering a “second opinion” that enhances diagnostic confidence and consistency. Furthermore, the integration of this system into dental imaging workflows could streamline the diagnostic process, reduce variability across clinicians, and ultimately improve patient care and treatment outcomes.

The list of the abbreviations (Abbre) used in the research are provided in Table 1.

The main contribution introduced in this work are listed as follows:

-

A modified Swin based vision transformer (ViT) called as MSViT is developed that utilizes a hierarchical approach to feature extraction by employing shifted windows, allowing them to effectively capture both fine-grained local details and broader global structures in spectrograms.

-

Memetic approaches are formulated based on various global optimizers of ML with local search technique called as sequential quadratic programming (SQP) to train the hyper-parameters as well as feature selection of EDC problem dimensions.

-

These memetic approaches reduce the learnable parameters as well increase the fitness evaluation in a reasonable computational time by employing the fitness function in a semi-supervised manner.

-

The proposed results are compared with existed pre-trained models like ResNet-10115, VGGNet-1916, InceptionV313, and EfficientNet-b017 methods as well as formulated baseline technique based on GA-SQP and other reported results.

-

The reliability, stability, and computational complexity of the proposed architecture is established by performing Monte Carlo simulations based on 100 executable runs.

In the rest of the article, the earlier studies on the EDC problems as well ML and DL frameworks is organized in Section Related work and state of Art. However, the details regarding dataset and its associated difficulties, MSViT framework and its mathematical details and logical steps of the training protocols are given in Section Materials and methods. The Section Results and discussion provides the details regarding simulation setup, comprehensive results and their comparisons with pre-trained models like ResNet, VGGNet, InceptionV3 and EfficientNet. Finally, Section Conclusions summarizes the important points and suggests future research directions.

Related work and state of Art

Recent progress in biomedical informatics and computational medicine demonstrates the convergence of molecular biology, machine learning, and deep learning techniques for improving diagnosis and treatment. For instance, studies have shown the regulatory role of miRNAs in allergen expression21 and the role of innovation networks in advancing regional digital health systems22. Advanced transformer-based models have enabled effective classification of white patchy skin lesions23, angiogenesis regulation through long noncoding RNAs24, and dental plaque segmentation using cluster-enhanced frameworks25. Multi-view feature fusion has also been applied to predict protein subcellular localization26, while Janus hydrogels27 and novel hydrogel scaffolds28 have expanded opportunities in wound repair and dental pulp regeneration. Deep learning further enhances clinical applications, including melanoma detection with intensity-based approaches29, brain tumor classification using GAN-augmented Swin Transformers30, and hybrid encoder architectures for skin lesion segmentation31. In dental imaging, CNN models such as PDCNET improve periodontal disease classification32, and optimized metaheuristic approaches provide advanced solutions for chronic kidney disease detection33. Collectively, these studies reflect how interdisciplinary innovations are reshaping diagnostics, regenerative medicine, and healthcare analytics.

Furthermore, Clinical evaluations, intraoral radiographs, and pulp vitality tests have been used to diagnose reversible or irreversible pulpitis, pulp necrosis, and periapical periodontitis. Early computational models like LR and DT were applied to structured clinical data to improve consistency and reduce diagnostic subjectivity. Fuss et al.34 found that clinical and radiographic characteristics can detect apical periodontitis. These methods often lacked precision for critical clinical judgments. Shafiei et al.35 found that conventional models incorporating patient symptoms and radiographic assessments had prediction accuracies of 76%, but substantial inter-observer variability and manual feature selection prevented widespread clinical implementation. SVM, RF, and kth nearest neighbor (k-NN) were introduced to automate diagnosis as computational tools improved. These models improved moderately, diagnosing endodontic lesions from radiographs with 78–85% accuracy36. Uzun Ozsahin et al.37 detected periapical disease with 84.3% accuracy using an SVM classifier on digital periapical pictures. Despite improvements, these models needed substantial feature engineering and were susceptible to data imbalance and noise, limiting their real-world applicability. Most previous approaches had trouble processing complicated radiographic features and adapting to different imaging conditions. DL algorithms, which allow end-to-end feature extraction and outperform classical models in dental picture classification, have emerged due to these drawbacks.

Evolutionary algorithms have been used to optimize feature selection and model parameters in endodontic disease categorization to improve machine learning classifiers. Genetic Algorithms (GA) reduce dimensionality and improve classification accuracy by picking relevant features from dental radiographs and clinical data. L. Zhang et al.38 found that a GA-based feature selection method with a neural network diagnosed periapical lesions from panoramic radiographs with 90.2% accuracy. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) has been used to modify SVM and RF hyperparameters, improving accuracy by 6–8%39. These optimization techniques determine optimal parameter combinations to improve classifier learning and generalization. The Firefly Algorithm (FA) and Differential Evolution (DE) have optimized feature selection and model performance in medical imaging, including endodontic disease diagnosis. B. Sharma et al.40 identified apical periodontitis from CBCT scans with 91.4% accuracy using firefly-optimized ensemble learning. For high-dimensional datasets like dental radiographs, FA avoids local minima. J. Ramesh et al.41 used DE to optimize deep learning model parameters and achieved 93.7% classification accuracy on 2,000 annotated endodontic cases. These metaheuristic methods improve accuracy, model resilience, and computing efficiency, making them useful in endodontics computer-aided diagnosis systems.

Deep learning has revolutionized endodontic diagnoses, particularly in the classification of pulpitis, pulp necrosis, and periapical lesions using dental radiographs and CBCT images. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are a popular method for learning hierarchical features from image data without explicit feature engineering. CNN-based systems outperform classical machine learning models in diagnosis. Silva et al.42 found that a proprietary CNN model trained on periapical radiographs could diagnose periapical diseases with 91.6% accuracy, exceeding SVM and Random Forest, which reported 78–82% accuracy. Many research use transfer learning with pre-trained models like ResNet, VGG16, DenseNet, and EfficientNet to improve model performance and generalizability. These models, trained on ImageNet, can be fine-tuned for medical picture classification with limited annotated dental datasets. Lee et al.43 fine-tuned a pre-trained ResNet50 model on 2,000 annotated periapical radiographs and found 95.3% classification accuracy in discriminating normal tissues from infected ones. Transfer learning in dental diagnostics was validated by Kositbowornchai et al.44, who showed that a fine-tuned DenseNet model could diagnose apical lesions with 94.8% sensitivity and 96.1% specificity.

Recent improvements have added attention mechanisms and explainable AI tools like Grad-CAM to CNN architectures to improve model interpretability and clinical acceptance. Visual descriptions of root apex and pulp chamber areas match clinical diagnostic clues. Trust and transparency in AI-assisted endodontic systems require explainability. CNN-ViT hybrid models are also gaining popularity for extracting global context in high-resolution CBCT data. A Swin Transformer-based model classified complex root canal morphologies and pathological observations with 96.7% accuracy in Wang et al.45, demonstrating its potential in endodontic AI applications. Keeping in view the strengths and weakness of various stack of methods like classical, ML and DL technique, a hybrid approach is presented based on MSViT mimic with various global optimizers. The MSViT adopts a hierarchical feature extraction strategy using shifted window mechanisms while global optimizers involve GA, PSO, FA, DE hybrid with SQP that is a viable local search technique. The proposed framework is evaluated using publicly available root canal dataset (RCD)20 and the results are compared with baseline method, various pre-trained models and reported results on various performance indicators like mean accuracy, fitness value (fval), mean execution time (MET) in seconds and F1-score, respectively. The reliability, stability, and computational complexity are assessed through Monte Carlo simulations based on 100 independent executables.

Materials and methods

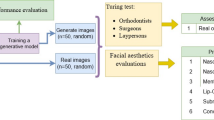

The section of the material and method is divided in three major components, in the first the details regarding dataset and its associated analogy is presented. The second component discuss the mathematical details of MSViT, however, in the last components the hybrid optimization techniques are presented which are employed for feature selection and obtaining the hyperparameters of MSViT architecture training, performance metrics and its logical steps used as protocol of learning. The overall workflow of the architecture is visually illustrated in Fig. 2.

Dataset details

The root canal data (RCD)20 on Kaggle is a public dataset of endodontics diagnostics and it can be valuable resource for benchmarking a DL architecture. This dataset contains annotated dental radiographs in grayscale format, specifically focusing on the identification of related pathologies such as vital asymptomatic (VA), hypersensitive dentin (HD), inflamed-reversible (IR), degenerating without area-irreversible (DAI), degenerating with area irreversible (DWAI), necrotic without area (NA) and necrotic with area (NWA), respectively. periapical lesions. The original RCD is composed of 425 images in which the standard dataset is divided in such a way that 297 images are used for training, 43 for testing and 85 for validation. Keeping in view the small size and imbalance dataset with respect to the number of endodontic classifications, the dataset is increased by applying the techniques of elastic deformation, rotation at different angles and employing the patch-based splitting. After data augmentation the large and balanced dataset is constructed and is called as enhanced RCD (ERCD) that have 1700 images with varying number of images in each disease class.

This augmentation improved class balance, increased variability, and reduced the effect of inter-class similarities, making the dataset more representative for training deep learning models. While not as large as multi-institutional datasets, the ERCD provided sufficient diversity to achieve high accuracy and generalization, and future work will focus on expanding towards larger, more diverse datasets. For evaluation purposes, the ERCD is split into 80% training and 20% testing. By the increase in dataset the problem of intra-class variation and inter-class similarity arises among the classification of DWAI and NWA. Its accessibility and structured format make it an excellent starting point for researchers exploring automated diagnosis in endodontics. The dataset is validated by the endodontists and prosthodontics practitioners in order to ensure the ground truth labels and also cross verified once mitigated from potential label noise.

Modified Swin vision transformer (msvit)

The Swin Transformer46 employs non-overlapping windows for local attention and shifted windows in subsequent layers to facilitate cross-window information flow, in contrast to Vision Transformers, which utilize global self-attention. This architecture streamlines processing while optimizing efficiency, rendering it suitable for high-resolution image and video tasks. The proposed DL architecture was selected because its compound scaling strategy balances depth, width, and resolution, allowing the model to capture both global patterns and fine structural details in endodontic radiographs. Combined with CPSO-SQP optimization for enhanced feature selection, the architecture is well aligned with the subtle morphological variations critical for accurate endodontic diagnosis. Additionally, by integrating the CPSO-SQP optimization framework, we enhanced feature selection and hyperparameter tuning, enabling the model to focus more effectively on clinically relevant regions. The input image \(\:Img\in\:{R}^{\mathcal{H}\times\:\varpi\:\times\:\mathbb{C}}\), where \(\:\mathcal{H}\), \(\:\varpi\:\) and \(\:\mathbb{C}\) representing height, width, and channel count respectively, is divided into fixed-size patches measuring \(\:\rho\:\times\:\rho\:\). The patches are further flattened and individually projected onto a D-dimensional embedding space via a trainable projection matrix. This procedure converts the image into a series of patch tokens, denoted as \(\:{\delta\:}_{0}=X\rho\:\), where \(\:\rho\:\) functions as the linear embedding operator, projecting each flattened patch into the model’s feature space, as articulated in Eq. (1).

where \(\:{x}_{1}\epsilon\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{\rho\:}^{2}.\mathbb{C}}\) is the flattened patch, \(\:E\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{\left(\rho\:.\mathbb{C}\right)\times\:d}\) is the patch embedding matrix, \(\:{E}^{positional}\) is the positional embedding, \(\:N=\frac{\mathcal{H}.\varpi\:}{{\rho\:}^{2}}\) is the total number of patches47.

MSViT performs self-attention operations within confined local windows of size N×N. To facilitate this, the query (Qe), key (K), and value (Val) matrices are computed by applying linear projections to the token embeddings. These matrices are then used to calculate the attention for each head, as described in the following expression:

where \(\:f(.)\), \(\:d\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are the log-sigmoid approximation function, head dimension and relative position bias matrix that is exploited to encode special position within the window, respectively.

To enable information exchange between neighboring windows, Swin introduce shifted window in alternate layers as given in relation (3)

In the next layer:

where W- \(\:{\Xi\:}\), SW- \(\:{\Xi\:}\), LayNor and \(\:{\Theta\:}\) are the window based self-attention, shifted window attention, layer normalization and feedforward network with nonlinear activation function. To build hierarchical representations, MSViT merges patches at the end of each stage as provided in relation (5).

where 4 neighboring tokens are concatenated and passed through a linear projection \(\:{W}_{merge}\) that reduces the special size and increase the feature dimension. \(\:H(.)\) is the concatenation function.

The final features are passed through global average pooling and then to a classification head as given below:

where \(\:{W}_{c}\:\)and \(\:{\beta\:}_{c}\) are the learnable parameters for classification. The proposed MSViT architecture is presented in Fig. 2 that takes patches of image as an input (\(\:{Img}_{pose}\)) and extract embeddings in the form of deep features. This input image is divided into patches and processed through self-attention layers as provided in MSViT.

where \(\:{\xi\:}_{SW}\) is the learned pose embedding vector.

The hyperparameters of MSViT and feature vector of endodontics dataset trained by MSViT are tuned with chaotic particle swarm optimization (CPSO) hybrid with SQP called CPSO-SQP. It learns spatial and temporal relationships of the feature vector followed by the dimensionality reduction. The explicit detail about the structure of the MSViT is given in Fig. 3 while the protocol used for computational process is given below:

Step1: Input data.

Consider the continuous pose images “\(\:Img\)” from the video frame.

Step 2: Pre-processing.

Pre-processing is performed based on normalization, resizing and extract the joint coordinates.

Step3: Applying proposed MSViT.

3(a): Convert \(\:Img\) into the M patches of size 32 × 32.

3(b): Flatten each patch and project into a feature space.

3(c): Add positional encoding to preserve spatial structure.

3(d): Pass patches through self-attention operations within confined local windows given in (2) and the results into the pose embedding.

Step4: Shifted window self-attention.

To allow cross-window communication, Swin applies shifted windows in alternate layers by using relation (3) and (4), respectively.

Step5: Hierarchical Feature Learning.

At the end of each stage, 4 neighboring tokens are concatenated and linearly projected to down sample spatial dimensions and increase feature depth by using relation in (5).

Step6: Classification Layer.

The final features are passed through global average pooling and then to a classification head as given in (6).

Step7: Pose Embedding Extraction.

The Swin-based Vision Transformer outputs the learned pose embedding vector as provided in (7).

Step8: Store classification of dance.

Store the output of the final dance sequences and along with their classes to perform a true dance classification and display.

Step9: Compute reliability of the system.

Compare the actual and predicted results on various performance measures like mean accuracy, precision, F1- score and Recall based on 100 executable runs and perform statistical analysis by repeating Step-3 to Step9.

Hyperparamegter tuning and feature vector optimization through CPSO-SQP

CPSO, an improved version of PSO, uses chaos theory to improve global search and avoid premature convergence. In typical PSO, particles update their velocities and locations depending on individual and collective experiences to search the space. PSO can get stranded in local optima, especially in complicated or high-dimensional issues48. The approach uses chaotic sequences from nonlinear chaotic maps like the Logistic map, Tent map, or Lorenz system to handle this. These sequences infuse organized randomness into particle locations, velocities, and learning parameters. Chaos’s ergodicity, sensitivity to beginning conditions, and pseudo-randomness make the swarm more diverse and dynamic throughout search, improving exploration and optimization. CPSO has been used in engineering design, image processing, scheduling, and medical diagnostics. Its key advantage over traditional PSO is its ability to balance exploration (finding new areas) and exploitation (refining known good areas). Hybrid techniques like adaptive chaotic PSO and multi-chaotic PSO dynamically switch between chaotic maps or alter chaos intensity based on swarm performance. The standard PSO velocity and position updating equations49 are presented in Eq. (8) and Eq. (9) below:

where \(\:\kappa\:\) is the inertial weight and \(\:{C}_{1}\) & \(\:{C}_{2}\) are the balancing parameters for cognitive and social influences, \(\:rand1\left(\right)\) and \(\:rand2\left(\right)\) are coefficients generating the randomness in the search space. In (8), the first component “\(\:\kappa\:{V}_{i}\left(t\right)\)” deals with the previous velocity and weight factor while the second component “\(\:{C}_{1}rand1\left(\right)\times\:\left(LB-{X}_{i}\right)\)” provides the local intelligence and third “\(\:{C}_{2}rand2\left(\right)\times\:\left(GB-{X}_{i}\right)\)” explain the global convergence of the algorithm. Moreover, \(\:LB\) and \(\:GB\) are the local and global best candidate of the search space, respectively. The third components ensure the global convergence by avoiding the premature convergence. As the velocity updates the position of the particle will also change, consequently the mathematical relation explaining the position update is presented in (9).

where \(\:x\left(t\right)\) is the old and \(\:x\left(t+1\right)\) updated or current position of the particle in the swarm and \(\:V\left(t+1\right)\) is the updated velocity. The chaotic behavior is generated by introducing chaotic map based on logistic nature given in (10) in replacement of simple random functions like rand1(.) and rand2(.) of relation (8).

where \(\:\psi\:\) is the controlling parameter having the values varying values in the bound (3.57 to 4) while \(\:{\text{{\rm\:Y}}}_{t\:}\epsilon\:\left(\text{0,1}\right)\) is chaotic sequence value at iteration t. Therefore, the velocity updating equation is modified as follows in (11).

Such CPSO solves difficult nonlinear and multimodal optimization problems more reliably by increasing diversity and decreasing premature stagnation. Its low computational overhead makes it appealing for real-time and large-scale optimization where traditional metaheuristics fail.

One of the most powerful and extensively used optimization methods for nonlinear constrained optimization problems is SQP50. It solves quadratic programming subproblems that locally approximate the nonlinear problem iteratively. Each iteration, SQP builds a quadratic objective function model and a linear constraint model to find a search direction that enhances feasibility and optimality. The method is effective for situations when objective and constraint function gradients are available or can be calculated properly because it forms subproblems. SQP converges quickly and typically performs superlinearly toward the optimal solution by refining these approximations at each stage. In this article SQP is used as a hybrid approach in such a manner that the output of the selected feature vector is pass as a start point of SQP for further refinement, this natural mimic of CPSO and SQP is called as hybrid optimization and named CPSO-SQP. Keeping in view the stochastic nature of MSViT architecture and random nature of the CPSO-SQP algorithm Monte Carlo simulations are performed based on sufficient large number of independent runs “IR = 100” that guarantee the stability of the proposed farmwork. A comprehensive statistical analysis is performed for accuracy, sensitivity, fitness value and computational time based on various performance metrics like minimum (Min), Maximum (Max), mean ( \(\:\stackrel{-}{z}\) ), standard deviation (STD) and kurtosis (KUR), Mathew’s Correlation Coefficient (MaCC) and Cohen’s Kappa (CoK)51,52. The standard mathematical relations are exploited for these statistical parameters as given in relation (12) to Eq. 16, respectively. This would also help to ensure the applicability, reliability and stability of the proposed model.

where \(\:{z}_{i}\) is result of each individual run and IR is the total number of results stored in the database to perform the statistical analysis. The performance indicators like accuracy, error, sensitivity, specificity, False Positive Rate, F1 Score, are used49. The results of the proposed architecture and other state of art techniques are also computed using the same performance measure using the standard mathematical formulas given in the literature50, however the formula used for MaCC and CoK are given below:

.

\(\:{P}_{e}=\:\left(\frac{\left(TP+FP\right)\left(TP+FN\right)+\left(FN+TN\right)\left(FP+TN\right)}{{\left(TP+TN+FP+FN\right)}^{2}}\right)\)The proposed training algorithm CPSO-SQP is give below in the form of pseudocode:

Results and discussion

The proposed farmwork based on MSViT optimized with CPSO-SQP is examined on enhanced RCD (ERCD) for classification of seven endodontic diseases. Each disease class like VA, HD, IR, DAI, DWAI, NA and NWA have 250,220,230,300,200,220 and 280 images, respectively. However, the total number of images in ERCD are 1700. The training to testing ratio is used as 80:20 with batch size of 32 and learning rate “α” is taken from [10− 02 to 10− 04]. The self-attention window size of 5 × 5 with 12 heads is exploited in the proposed DL network to examine endodontic diseases. In order to conduct the experiment, MATLAB R2024a is loaded on the hardware, which consists of an Intel i9-14900 K processor, 128GB of DDR5 RAM, 1 TB of NVMe storage, and an NVIDIA RTX 4080 graphics card that is specified. A rigorous approach based on CPSO-SQP is used to select the hyperparameter settings. This process involves carefully balancing underfitting, overfitting, and the effectiveness of the optimizers. The results are compared with ResNet-10115, VGGNet-1916, InceptionV313, and EfficientNet-b017 methods as well as formulated baseline technique based on GA-SQP. The hyperparameter values and settings exploited during the training process is tabulated in Table 2.

Furthermore, general as well as specific parameter values and configurations of CPSO and SQP used for optimizing feature weights are listed in Table 3.

Figure 4 shows the accuracy and loss function trends during MSW-ViT model training over 4800 iterations. In the upper subplot, accuracy rises steadily from 20% to sharply during training. This shows the model’s learning and convergence capacity as accuracy improves with tiny fluctuations, stabilizing over 97%. The loss curve in the lower subplot reveals a quick fall in the early iterations, followed by a gradual and smooth reduction that flattens out. This inverse relationship between accuracy and loss curves proves optimization stability. The convergence trend of increased accuracy and decreased loss shows that the MSW-ViT model has balanced learning precision and generalization, adjusting to the training data without overfitting.

The confusion matrix for classifying seven endodontic disease types using the MSW-ViT model tuned with the hybrid CPSO-SQP algorithm at α = 0.0001 is tabulated in Table 4. Class-wise performance is shown by the number and percentage of correctly and wrongly classified instances for each disease type. In the VA class, 196 occurrences (98.0%) were correctly identified, with only 0.5% misclassifications in other classes. HD had 97.727% accuracy, with just one incidence each misclassified into IR, DAI, DWAI, and NA (0.581% each). In 97.282% of cases, IR was accurately recognized, with slight misunderstanding with DAI (1.086%) and others (0.543%).

The model categorized DAI with 97.916% accuracy, misclassifying only four occurrences (0.416% each) above other categories. DWAI has 96.875% accuracy, with one sample misclassified into five other categories. Again, only a few misclassifications occurred while predicting the NA class. Finally, NWA obtained the greatest classification accuracy of 98.214%, showing the model’s significant discriminatory potential. The confusion matrix shows that MSW-ViT, optimized with the CPSO-SQP algorithm, performs well in all seven disease categories, with classification accuracies above 96% and low misclassification rates, proving the diagnostic framework’s viability and accuracy. Deep architectures are capable enough to perform the classification of different music categories as it inherently stores the features in the form of the vectors during the learning, therefore, it is worth to perform the accurate classification using proposed DL framework.

It is worth to mention that overall mean accuracy of the proposed architecture with CPSO-SQP is found to be 97.72% with a miscallaisifcation rate of 2.28% and a weighted F1- Score of 0.9772.

Moreover, the class-wise performance evaluation of the MSW-ViT model based on Precision, Recall, and F1-Score for the recognition of seven endodontic disease categories are presented in Table 5. The VA class achieved consistently high values across all metrics, with precision, recall, and F1-score all equal to 0.9800, indicating excellent and balanced recognition. For the HD class, the model performed similarly well with all three measures recorded at 0.9773. The IR class showed slightly varied values, with a precision of 0.9728 and a higher recall of 0.9835, resulting in a robust F1-score of 0.9781, reflecting the model’s effectiveness in capturing most true positives despite minor overprediction.

In the case of DAI, the precision was recorded at 0.9792 and recall at 0.9711, resulting in an F1-score of 0.9751, showing a slight trade-off between precision and recall. Similarly, the DWAI class achieved a precision of 0.9688 and a recall of 0.9810, yielding an F1-score of 0.9748, suggesting a higher sensitivity with slightly lower precision. The NA class had a precision of 0.9773 and recall of 0.9609, with an F1-score of 0.9690, indicating good but slightly imbalanced performance. Lastly, the NWA class achieved the highest overall performance, with precision at 0.9821, recall at 0.9865, and an F1-score of 0.9843, showcasing the model’s superior ability to accurately and consistently identify this class. Overall, the performance metrics confirm that the MSW-ViT model delivers highly reliable recognition across all categories, with F1-scores exceeding 0.96 for every class and particularly strong generalization for difficult-to-distinguish cases, reinforcing its effectiveness in multi-class endodontic disease classification. Keeping in view the black nature of proposed architecture various ablation studies has been made to see the effects of the variations due to learning rate, relaibility of the framework, feature chacarcterstics and computational cost.

Ablation Study-1: effect on the fitness value by the learning rate

The Fig. 5(a) shows how learning rates affect the CPSO-SQP algorithm’s fitness function across 100 separate runs. This plot compares three learning rates: α = 0.01 α = 0.01, α = 0.001 α = 0.001, and α = 0.0001 α = 0.0001, represented in blue, red, and yellow. High learning rates (α=0.01 α = 0.01) result in unstable fitness values, indicating uneven convergence and inferior performance. However, fitness improves significantly when learning rate lowers. While some variation remains, performance becomes more constant with α=0.001 and α = 0.001. Low learning rate (α=0.0001 α = 0.0001) yields the most consistent and optimal results, with fitness values in the lowest range across most runs, indicating solid convergence and minimal error. Lower learning rates improve the stability and accuracy of the CPSO-SQP algorithm, making α = 0.0001 and α = 0.0001 the most effective option examined.

Similarly, the Fig. 5 (b) plots the fitness function across 100 independent runs to evaluate the SQP algorithm under different learning rate settings. The maximum learning rate α = 0.01 leads to higher fitness values, indicating poor optimization and convergence instability. Lowering the learning rate to α = 0.001 increases performance, resulting in lower fitness values and reduced variance. The most stable and best results occur with a modest learning rate α = 0.0001, resulting in closely clustered fitness values throughout all runs. This suggests that the SQP method, fine-tuned with a low learning rate, minimizes the objective function more efficiently and consistently across executions.

Table 6 compares fitness values from SQP and PSO-SQP optimization techniques at various learning rates (α = 0.01, α = 0.001, and α = 0.0001). Standard statistical indicators like Min, Max, mean, STD, and kurtosis are used to evaluate each approach. All learning rates show that PSO-SQP outperforms the standalone SQP algorithm. PSO-SQP outperforms SQP at the lowest learning rate (α=0.001 α = 0.0001), with a minimum value of 4.32 × 10−12 and a mean value of 3.40 × 10−11, indicating greater fitness. Higher learning rates lead to lower fitness values for both methods, peaking at α=0.01 and α = 0.001. Even at this suboptimal rate, PSO-SQP outperforms SQP in average fitness and variability.

Both approaches have stable kurtosis values across learning rates, indicating similar fitness distribution morphologies. However, PSO-SQP has a slightly greater kurtosis at α=0.01 and α = 0.001, indicating sharper fitness peaks. This investigation demonstrates that the hybrid PSO-SQP strategy yields higher average optimization outcomes and more consistent convergence, even with a small learning rate (α=0.0001).

Ablation Study-2: reliability of SQP and CPSO-SQP on MSW-ViT architecture

The reliability of SQP and CPSO-SQP is presented in Fig. 6 that compares the fitness curves of the SQP and CPSO-SQP algorithms over 100 separate runs to highlight their fitness function minimization optimization performance. The plot shows that CPSO-SQP has lower fitness values than traditional SQP in most runs. The SQP curve starts at higher fitness values (10− 03) and gradually descends, although convergence is limited and unstable. However, the CPSO-SQP curve begins with higher fitness levels and gradually decreases to 10− 06, showing more successful and persistent convergence.

CPSO-SQP performs better because particle swarm optimization integrates chaotic dynamics and global search, which boost exploration and reduce premature convergence. The chart shows that CPSO-SQP maximizes optimization and is more durable and reliable across numerous executions.

Ablation Study-3: computational cost of MSW-ViT architecture

Figure 7 shows the computational cost, in seconds, for the SQP, PSO, and CPSO-SQP algorithms over 100 separate runs, revealing their efficiency and resource needs. The SQP algorithm has the lowest computational time, 300–500 s. As a gradient-based method, SQP is computationally less demanding but may sacrifice solution quality for speed. The orange and yellow curves, representing PSO and CPSO-SQP, have higher computing costs, often 700–1000 s. CPSO-SQP has the biggest runtime variability due to the computational complexity of integrating chaotic behavior into PSO. These metaheuristic-based approaches take longer to run, but their improved optimization accuracy and robustness shown in earlier figures justify it in complicated problems. SQP is faster but less precise, while CPSO-SQP optimizes better but takes longer.

Ablation Study-4: feature interference characterization

Figure 8 shows a 3D depiction of the specified feature space for seven endodontic disease groups plotted along Feature X, Feature Y, and Feature Z. Each data point represents a feature vector for one of the illness categories VA, HD, IR, DAI, DNAI, NA, and NWA coded with colors for visual distinction. The 3D point distribution suggests that the selected features give good class separability with minimum cluster overlap. In particular, NWA and NA appear to occupy different feature space regions, showing substantial discrimination. Meanwhile, IR and HD classes are spatially close, suggesting feature similarity that could make classification difficult. This spatial representation shows that the selected 3D characteristics capture the data’s structure, allowing the MSW-ViT model to accurately identify multiple disease categories. The visualization supports the feature selection strategy’s class separability and model interpretability improvements. The graph illustrates the multi-dimensional relationships among categories, elucidating feature grouping, separability, and dataset patterns. Classification tasks in DL benefit from the investigation of feature space distribution for feature selection, dimensionality reduction, and model training.

Discussion on the results of proposed architecture

Table 7 provides a comprehensive comparison of the proposed MSW-ViT model, optimized with CPSO-SQP, against several pre-trained models and baseline optimization techniques, based on key performance indicators such as fval, MSE, mAcc and mAP. Among the pre-trained models, InceptionV3 and EfficientNet-b0 outperform traditional architectures like ResNet-101 and VGGNet-19, with InceptionV3 achieving a mean accuracy of 90.03% and a mAP of 0.9282, and EfficientNet-b0 slightly higher at 90.79% accuracy and 0.9342 mAP. However, their fitness values and MSE remain significantly higher than the proposed hybrid optimization approaches. The models incorporating hybrid optimization show progressive improvements. SA-SQP and GA-SQP improve mean accuracy to 91.23% and 93.28%, respectively, with corresponding reductions in MSE and better fitness values. Notably, the proposed CPSO-SQP optimized MSW-ViT achieves the best overall performance, with a remarkably low fitness value of (2.37 × 10− 11), a minimal MSE of 0.00082, a mean accuracy of 97.72%, and a mean average precision of 0.9749. This confirms the effectiveness of the hybrid chaotic optimization strategy in achieving superior classification accuracy and precision compared to both pre-trained deep models and other baseline techniques.

The performance of PSO-SQP, while also strong (94.89% accuracy and 0.9643 mAP), is slightly lower than CPSO-SQP, reinforcing the advantage of incorporating chaos and hybridization in the optimization process. Overall, the table highlights the superiority of the proposed CPSO-SQP approach in endodontic disease recognition.

Moreover, a comparative analysis of the proposed MSW-ViT model optimized with CPSO-SQP against various pre-trained models and baseline techniques, focusing on model depth, memory consumption, number of parameters, and input image size presents in Table 8. Among the pre-trained architectures, VGGNet-19 has the highest parameter memory footprint at 548 MB and the largest parameter count of 144 million, indicating a significant computational load despite its relatively shallow depth of 19 layers. In contrast, EfficientNet-b0 stands out as the most lightweight pre-trained model, with only 5.3 million parameters and 20 MB of memory usage, while still operating with a depth of 82 and maintaining an input size of 224 × 224. ResNet-101 and InceptionV3, though deeper and moderately optimized, also require higher memory (171 MB and 91 MB respectively), making them more demanding in terms of computational resources.

Shifting focus to the baseline optimization approaches, both SA-SQP and GA-SQP models operate with a uniform depth of 64 layers and significantly reduced memory and parameter profiles, ranging from 23 to 27 MB and around 5 million parameters, using smaller input sizes of 96 × 96 pixels. Most notably, the proposed CPSO-SQP model achieves the best efficiency, requiring just 17 MB of memory and utilizing only 4.1 million parameters, making it the most lightweight and computationally efficient model in the comparison. The PSO-SQP variant follows closely with 18 MB and 4.7 million parameters. This demonstrates the proposed framework’s significant advantage in reducing both model size and resource consumption without compromising accuracy, making it particularly suitable for deployment in resource-constrained clinical environments or edge devices.

Conclusions

Drawing from the results shown in various tables and figures, the following conclusions are made in light of the extensive simulation and ablation investigations conducted in the preceding section:

-

The proposed architecture provides a mean accuracy of 97.72%, when it comes to the pre-trained models, InceptionV3 and EfficientNet-b0 perform better than standard architectures such as ResNet-101 and VGGNet-19. InceptionV3 achieves a mean accuracy of 90.03% and a mAP of 0.9282, while EfficientNet-b0 achieves a slightly higher accuracy of 90.79% and a mAP of 0.9342.

-

The performance of PSO-SQP is superior to that of SQP when it comes to the lowest learning rate (α=0.001 α = 0.0001). It has a minimum value of 4.32 × 10-12 and a mean value of 3.40 × 10-11, which indicates that it is more fit. The fitness values for both approaches are reduced when the learning rates are increased, with the maximum values occurring at α=0.01 and α = 0.001.

-

The mean accuracy of the suggested architecture with CPSO-SQP was determined to be 97.72%, with a misclassification rate of 2.28% and a weighted F1- Score of 0.9772.

-

In conclusion, the CPSO-SQP optimized MSW-ViT model demonstrates clear superiority over both pre-trained deep networks and traditional optimization methods by achieving the highest accuracy, lowest MSE, and most optimal fitness value, validating the strength of hybrid chaotic optimization for precise and efficient endodontic disease classification.

-

The SQP algorithm achieves the lowest computational time (300–500 s) due to its gradient-based efficiency but may compromise solution quality. In contrast, PSO and CPSO-SQP incur higher computational costs (700–1000 s), with CPSO-SQP exhibiting the greatest runtime variability, attributed to the added complexity of chaotic integration.

-

The suggested CPSO-SQP optimized MSW-ViT model achieved improved accuracy with the lowest memory footprint and parameter count, outperforming standard optimization approaches and pre-trained architectures. The combination of chaotic dynamics with hybrid optimization provides great diagnostic precision and computing economy, making it appropriate for endodontic disease identification in resource-constrained clinical settings.

-

The AI architecture is providing the decision based on the characteristics of feature of various diseases and test / validate it on a reasonable amount of the dataset. The output is interpretable in a sense that when the clinical experts get the initial diagnostics from the AI model, they can study respective feature vectors only to make the final decision.

-

In future, one may investigate the hardware implementation on the nano chips should be performed for real time applications and useability in the industry. Moreover, one can also include benchmarking on other dental imaging hardware, include comprehensive clinical setting and generalization of workflow integration for complete clinical utility.

Limitation of proposed architecture

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations. First, the dataset was derived from a single publicly available source and augmented to increase sample size, which may limit its diversity and generalizability. Second, the model outputs were not accompanied by interpretability features such as saliency maps or Grad-CAM visualizations, which are important for clinician trust and understanding of AI decisions. Finally, the inference latency and hardware compatibility, or usability in real dental workflows may cause difficulty in directly adopting the proposed framework.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at : https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/lokisilvres/dental-disease-panoramic-detection-dataset.

References

Mannocci, F. et al. Present status and future directions: the restoration of root filled teeth. Int. Endod J. 55, 1059–1084 (2022).

Tibúrcio-Machado, C. S. et al. The global prevalence of apical periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod J. 54 (5), 712–735 (2021).

Duncan, H. F. et al. Treatment of pulpal and apical disease: the European society of endodontology (ESE) S3-level clinical practice guideline. Int. Endod J. 56, 238–295 (2023).

Committee on an Oral Health Initiative. Advancing Oral Health in America (National Academies, 2012).

Abbott, P. V. Classification, diagnosis and clinical manifestations of apical periodontitis. Endod Top. 8 (1), 36–54 (2004).

Lo, R. et al. Accuracy of periapical radiography and CBCT in endodontic evaluation. Int. J. Dent. 2018 (1), 2514243 (2018).

Mejàre, I. A. et al. Diagnosis of the condition of the dental pulp: a systematic review. Int. Endod J. 45 (7), 597–613 (2012).

Tumbelaka, B. Y., Oscandar, F., Baihaki, F. N., Sitam, S. & Rukmo, M. Identification of pulpitis at dental X-ray periapical radiography based on edge detection, texture description and artificial neural networks. Saudi Endodontic J. 4 (3), 115–121 (2014).

Price, J. B. Digital imaging. in Clinical Appl. Digit. Dent. Technology, 1 1–27. (2023).

Raja, M. A. Z., Khan, J. A., Ahmad, S. I. & Qureshi, I. M. Numerical treatment for Painlevé equation I using neural networks and stochastic solvers, in Innovations in Intelligent Machines-3: Contemporary Achievements in Intelligent Systems, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 103–117. (2013).

Farooq, S. Diagnosis of Dental Caries-Old and the New (OrangeBooks Publication, 2022).

Raja, M. A. Z., Khan, J. A., Zameer, A., Khan, N. A. & Manzar, M. A. Numerical treatment of nonlinear singular Flierl–Petviashivili systems using neural networks models. Neural Comput. Appl. 31, 2371–2394 (2019).

Chen, H., Li, H., Zhao, Y., Zhao, J. & Wang, Y. Dental disease detection on periapical radiographs based on deep convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 16, 649–661 (2021).

Ramezanzade, S. et al. The efficiency of artificial intelligence methods for finding radiographic features in different endodontic treatments-a systematic review. Acta Odontol. Scand. 81 (6), 422–435 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. ResNet-Transformer deep learning model-aided detection of dens evaginatus. Int J. Paediatr. Dent,35 (4), 708–16. (2024).

Wu, P. Y. et al. Precision medicine for apical lesions and Peri-Endo combined lesions based on transfer learning using periapical radiographs. Bioengineering 11 (9), 877 (2024).

Fang, F., Gao, B., He, T. & Lin, Y. Efficacy of root Canal therapy combined with basic periodontal therapy and its impact on inflammatory responses in patients with combined periodontal-endodontic lesions. Am. J. Transl Res. 13 (12), 14149 (2021).

Qu, Y. et al. Machine learning models for prognosis prediction in endodontic microsurgery. J. Dent. 118, 103947 (2022).

Ennab, M. & Mcheick, H. Advancing AI interpretability in medical imaging: A comparative analysis of Pixel-Level interpretability and Grad-CAM models. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 7 (1), 12 (2025).

Alam, B. M. S. & Data, R. C. kaggle, [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/bmshahriaalam/root-canal-data (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Regulatory roles of three MiRNAs on allergen mRNA expression in tyrophagus putrescentiae. Allergy 77 (2), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.15111 (2022).

Hu, F. et al. Innovation networks in the advanced medical equipment industry: supporting regional digital health systems from a local–national perspective. Front. Public. Health. 13, 1635475. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1635475 (2025).

Li, Z. & others White patchy skin lesion classification using feature enhancement and interaction transformer module. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 107, 107819 (2025).

Bao, M. et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00657 acting as a miR-590-3p sponge to facilitate low concentration oxidized low-Density Lipoprotein–Induced angiogenesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 93 (4), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.117.110650 (2018).

Song, W. & others Centerformer: a novel cluster center enhanced transformer for unconstrained dental plaque segmentation. IEEE Trans. Multimedia, 26 10965–10978. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2024.3428349(2024).

Li, B. et al. Prediction of protein subcellular localization based on fusion of Multi-view features. Molecules 24 (5), 919. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24050919 (2019).

Xu, S. L. et al. Double-sided protector’ Janus hydrogels for skin and mucosal wound repair: applications, mechanisms, and prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 23 (1), 387 (2025).

Guo, L., Li, X., Wu, J., Xu & Y., & Recent advancements in hydrogels as novel tissue engineering scaffolds for dental pulp regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 264, 130708 (2024).

Ahmed, A. et al. Efficient Melanoma Detection Using Pixel Intensity–Based Masking and Intensity–Weighted Binary Cross–Entropy. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 35 (5), e70179 (2025).

Almuhaimeed, A. et al. Brain tumor classification using GAN-augmented data with autoencoders and Swin Transformers. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 12 (12), 1635796 (2025).

Ahmed, A., Sun, G., Bilal, A., Li, Y. & Ebad, S. A. A hybrid deep learning approach for skin lesion segmentation with dual encoders and Channel-Wise attention. IEEE Access 13, 42608–42621 (2025).

Bilal, A. et al. PDCNET: Deep convolutional neural network for classification of periodontal disease using dental radiographs. IEEE Access 12 150147–150168. (2024).

Bilal, A. et al. Advanced CKD detection through optimized metaheuristic modeling in healthcare informatics. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 12601 (2024).

Fuss, M., Lustig, S., Dula, B. & Stover, E. M. Prevalence of periapical lesions in patients undergoing endodontic therapy. J. Endod. 27 (8), 509–512 (2001).

Shafiei, F., Hasheminia, M. M. & Faghihi, M. J. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical and radiographic findings in determining the pulp status of human teeth. Iran. Endod J. 13 (3), 323–328 (2018).

Torabinejad, H. & Kutsenko, M. Accuracy of data mining in classifying endodontic disease using radiographic images. J. Dent. Res. 93 (7), 737–743 (2014).

Ozsahin, D. U., Sharma, D. & Uzun, N. Artificial intelligence-based classification of dental periapical lesions in radiographs. Comput. Biol. Med. 137, 104794 (2021).

Zhang, L., Gao, Y. & Zhao, H. Genetic algorithm-based feature selection for neural network diagnosis of endodontic lesions. Expert Syst. Appl. 89, 190–198 (2017).

Patel, M. & Saxena, A. Particle swarm optimization tuned SVM for endodontic disease prediction. Procedia Comput. Sci. 132, 963–970 (2018).

Sharma, B., Singh, D. & Rajan, K. Firefly algorithm-based ensemble classification for CBCT-based diagnosis of apical periodontitis. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 68, 102624 (2021).

Ramesh, J., Thomas, A. & Kumar, S. K. Differential evolution optimized CNN for dental disease classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 113, 107904 (2021).

Silva, F., de Oliveira, J. & Lima, M. A. Automatic detection of periapical lesions in digital radiographs using deep convolutional neural networks. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 28, 1–8 (2020).

Lee, C., Kim, S. & Lee, D. Endodontic disease classification using transfer learning with ResNet on dental radiographs. Comput. Biol. Med. 124, 103943 (2020).

Kositbowornchai, S., Plermkamon, A. & Sookkorn, N. Apical lesion detection using densenet with transfer learning on dental radiographic images. Imaging Sci. Dent. 51 (3), 145–152 (2021).

Wang, X., Zhang, Y. & Liu, L. Swin transformer for CBCT-based endodontic disease classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 27 (1), 55–63 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 10012–10022 (2021).

Khan, J. A., Zahoor, R. M. A. & Qureshi, I. M. Swarm Intelligence for the Solution of Problems in Differential Equations. in Second International Conference on Environmental and Computer Science 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECS.2009.85 (Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2009).

Zaman, F., Qureshi, I. M., Khan, J. A. & Khan, Z. U. An Application of Artificial Intelligence for the Joint Estimation of Amplitude and Two-Dimensional Direction of Arrival of Far Field Sources Using 2-L-Shape Array. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2013 (1), 593247 (2013).

Raja, M. A. Z., Khan, J. A. & Qureshi, I. M. Swarm intelligence optimized neural networks in solving fractional system of Bagley-Torvik equation. Eng. Intell. Syst. 19 (1), 41–51 (2011).

Basharat, M., Khan, J. A., Abdo, H. G. & Almohamad, H. An integrated approach-based landslide susceptibility mapping: case of Muzaffarabad region, Pakistan. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk. 14 (1), 2210255 (2023).

Raja, M. A. Z., Khan, J. A., Ahmad, S. I. & Qureshi, I. M. Solution of the Painlevé equation-I using neural network optimized with swarm intelligence. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2012, 1–10 (2012).

Khan, J. A., Raja, M. A. Z. & Qureshi, I. M. Hybrid evolutionary computational approach: application to Van der pol oscillator. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 6 (31), 7247–7261 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YuanYuan Chen, Zhi Jian Su, and Rui Zhang contributed equally to the conceptualization, methodology design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. ShiLu Huang provided critical supervision, project administration, and final review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Su, Z.J., Zhang, R. et al. AI meets endodontics a deep learning approach to precision diagnosis. Sci Rep 15, 42727 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26768-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26768-6