Abstract

Probiotic fermentation with a defined consortium (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus) successfully transformed pumpkin juice into a functional beverage with enhanced bioactivity and appealing aroma. The fermented product achieved a high viable count of 7.37 log CFU mL−1, along with significant increases in vitamin C, total phenolics, flavonoids, and carotenoids compared to unfermented juice. Fermentation also imparted a distinct volatile profile enriched with esters and alcohols—such as phenylethyl alcohol, phenethyl acetate, and ethyl caprylate—which contributed intense fruity and floral notes, as confirmed by OPLS-DA and sensory evaluation. The resulting juice retained its original color (ΔE < 2) and developed desirable rheological behavior. Thus, accordingly the pumpkin juice fermented with the composite probiotics received the highest sensory evaluation. This study demonstrates that composite-culture fermentation effectively enhances the nutritional value, aroma, and sensory quality of pumpkin juice, highlighting its potential as a novel probiotic beverage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pumpkins (Cucurbita moschata) are renowned for their rich nutritional content, which includes polysaccharides, carotenoids, amino acids, and other essential nutrients1. Additionally, pumpkins hold significant medicinal value, facilitating growth and development while exhibiting diuretic and laxative properties. Pumpkins also exhibit notable antioxidant, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activities2. Due to their large production volume, there has been concern about resource wastage3. Meanwhile, the deep processing of pumpkins has gained considerable attention. Currently, the primary methods of preparing pumpkins involve frying, stir-frying, steaming, boiling, and drying to make pumpkin snacks, pumpkin puree, and other pumpkin-based foods. Furthermore, the monotonous and insipid “boiled flavor” derived from thermal processing exhibits relatively low acceptability among specific consumer groups4. Therefore, it is necessary to adopt new processing methods to enhance the utilization rate and nutritional quality of pumpkins, as well as to improve their undesirable flavor. Fresh pumpkins have a high water content, which is conducive to microbial growth and reproduction, leading to easy spoilage and significant waste of pumpkin resources. However, precisely due to this drawback, we can utilize microbial fermentation to combine the advantages of microorganisms and pumpkins, creating foods that are popular among the masses. Pumpkin was selected as the fermentation substrate not only for its abundant yield but also for its unique chemical composition, which possesses a rich and complex carotenoid matrix—an excellent target for microbial enzymatic hydrolysis—with the potential to release enhanced antioxidant activity during fermentation. Furthermore, pumpkin juice contains specific flavor precursor components, including unsaturated fatty acids and amino acids, all of these can be transformed via microbial activity, thereby driving significant flavor shifts toward more desirable fruity and sweet note.

Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms conferring health benefits to the host, naturally colonize human tissues such as the skin, oral cavity, and gastrointestinal tract. They are also extensively employed in the fermentation of fruit and vegetable juices as well as dairy products to enhance sensory qualities5 and extend shelf life6. In this study, a synergistic fermentation system using Saccharomyces cerevisiae and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) was developed to exploit their complementary metabolic features. LAB preferentially utilize readily fermentable sugars, leading to rapid acidification that lowers the pH. This acidic environment inhibits the growth of contaminating fungi and contributes to improved product stability7. Concurrently, S. cerevisiae metabolizes residual carbon sources and intermediate metabolites, thereby increasing substrate utilization efficiency and overall fermentation yield. Moreover, metabolic cross-feeding between the two groups enhances microbial proliferation: LAB supply amino acids and B-group vitamins that support S. cerevisiae growth, while S. cerevisiae hydrolyzes macromolecules into peptides and free amino acids, which in turn promote LAB activity. From a flavor perspective, LAB-induced acidification stimulates ester synthase activity in S. cerevisiae, promoting ester biosynthesis. Additionally, ethanol produced by S. cerevisiae can esterify with organic acids derived from LAB, further enriching the aromatic profile. The cooperative metabolism of both microorganisms also facilitates the production of functional compounds such as polyphenols, vitamins, and antimicrobial peptides8. This synergistic relationship, based on metabolic division of labor, accelerates substrate conversion and shortens the fermentation time. It also helps retain the nutritional and sensory attributes of the original juice matrix9. While mixed-strain fermentation has been applied in the fermentation of fruit and vegetable juices such as mango10, carrot9, and tomato11, fermentation research on pumpkin juice remains limited to single-strain fermentation. Furthermore, research on synergistic fermentation using the specific strain combination employed in our experiment—Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae—remains scarce. The present study reveals the unique microbial metabolism-driven flavor changes in pumpkin juice, as well as the study on rheological properties in fermented pumpkin juice, this characteristic has not been emphasized in studies on other fermented fruit and vegetable juices.

Due to the waste of pumpkin resources and advancements in fermentation technology, utilizing high-quality probiotics to ferment pumpkin can address the issue of pumpkin waste, make pumpkin products with desirable flavors more acceptable to the general public, and also promote economic development. Based on a survey of probiotic products, our study utilizes fresh pumpkin juice as the raw material and selects Lactobacillus helveticus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae for fermentation to produce a pumpkin juice beverage. Comparisons were made between the fermented pumpkin juice beverage, sterile pumpkin juice, and fresh pumpkin juice in terms of changes in physicochemical properties, bioactive compound content, and rheological characteristics, as well as differences in volatile flavor compounds. In this study, the feasibility of fermenting pumpkin juice with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, as well as the impact of fermentation on the nutritional properties of the pumpkin juice, were evaluated.

Material and methods

Reagents and standard

The freeze-dried powders of Lactobacillus helveticus (CICC 6024) Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus (CICC 20253) were obtained from Beina Biology—Hebei Provincial Industrial Microbial Species Engineering Technology Research Center (Hebei, China). While the Saccharomyces cerevisiae (CGMCC 2.3868) was purchased from Angel Yeast Co., Ltd. (Hubei, China). Plate Count Agar (PCA) medium, MRS solid medium, and MRS liquid medium were purchased from Huankai Microbiology Co., Ltd. (Guangdong, China). Rutin standard, gallic acid standard, L-ascorbic acid, Al(NO3)3·9H2O, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, n-hexane, and pectinase (30,000 u/g) were all purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 2,6-Dichlorophenolindophenol (C12H7Cl2NO2) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Na2CO3, NaNO2, NaOH, NaHCO3, phenolphthalein, kaolin, and oxalic acid solutions were all purchased from Fuchen Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (752N, Youke Instrumentation Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), refractometer (WZS50, Shanghai Yidian Physical Optics Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), pH meter (Leici, Shanghai Yitian Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) system (8090-7000E, Agilent Technologies Inc., USA), colorimeter (LS171, Linshang Technology Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China), rheometer (HR-2, Baosheng Industrial Development Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), autoclave (Gl100DWS, ZEALWAY Instrument Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China), constant temperature incubator (SPX-100B-Z, Boxun Industrial Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), high-speed centrifuge (HC-2062, Anhui Zhongke Zhongjia Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Anhui, China), and juicer (L18-P132, Joyoung Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The purity grade of the above chemical substances is ≥ 99%.

Sample preparation and fermentation

The selected pumpkins (purchased from the local market in Nanchang city, Jiangxi Province) were fresh, mature, and exhibited bright coloration with no signs of decay. After cleaning, peeling, and deseeding, the pumpkins were cut into uniformly thin slices of moderate size. The slices were steamed to achieve softening (which can effectively inactivate endogenous enzymes and soften plant tissues, significantly increase juice yield and promote the extraction of bound bioactive substances), cooled to room temperature, and combined with pure water in a 3:1 ratio (water to pumpkin). The mixture was juiced using a mechanical juicer. The resulting juice was filtered through an 8-layer gauze to obtain a clear filtrate, which was subsequently sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min and rapidly cooled to room temperature for further use.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae were retrieved from − 80 °C storage and thawed for resuscitation. The resuscitated Saccharomyces cerevisiae was inoculated into sterile, pre-cooled YPD medium and incubated statically at 28–30 °C for 8–12 h. Similarly, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains were thawed, resuscitated, and inoculated into sterile pre-cooled MRS medium. The inoculated MRS medium was gently mixed and incubated statically under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 12–24 h. Activation was confirmed by the development of turbidity in the bacterial suspension.

The inoculation ratio was determined as optimal based on preliminary single-factor tests and response surface methodology optimization, with the goal of maximizing viable bacterial count and overall product quality. The activated strains (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus) were inoculated into sterile pumpkin juice at a volume ratio of 1:1:2, with a total inoculation volume of 3%. The inoculated juice was incubated at 35 °C for 27 h under static conditions.

Total colony count

Referencing the methodology outlined by ISO 4833–1:2013 and Li et al.12, the viable bacterial count was determined using the plate dilution method.

pH, total acid content, total soluble solids

The pH value was directly measured using a pH meter.

Following the method described by AOAC 942.15 and Wang et al.13, the total acid content of the samples was determined using an acid–base titration method.

Following the method described by ISO 2173:2003, the soluble solids were determined using a handheld refractometer.

Color measurement

The color of the pumpkin juice was determined using a colorimeter. Method refer to Wang et al.14. The L*, a*, and b* values were measured, and these values were utilized in equations to calculate chroma (C*), hue angle (h°), total color difference (ΔE), browning index (BI), and yellowing index (YI).

Determination of vitamin C content, total phenol content, and flavonoid content

The vitamin C content was determined using the method described by AOAC 967.22 and Liu et al.15 which employed the 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) titration method.

The total phenolic content was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method. The experimental method and steps are slightly modified according to the experimental design based on Martín-Gómez et al.16. Specifically, 1 mL of sample solution was mixed with 1 mL of 95% ethanol, 5 mL of distilled water, and 0.5 mL of 10% Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. The mixture was shaken well and allowed to react for 5 min. Subsequently, 1 mL of 5% Na2CO3 solution was added, and the mixture was shaken well again. The solution was then allowed to stand at room temperature for 60 min. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer, with gallic acid serving as the standard.

The flavonoid content was determined using the aluminum chloride method. The experimental method and steps are slightly modified according to the experimental design based on Yin et al.17. Specifically, 5 mL of sample solution was mixed with 3 mL of anhydrous ethanol, followed by the addition of 1 mL of 5% NaNO2 solution and 1 mL of 10% AlCl3 solution. The mixture was shaken well and allowed to stand for 5 min. Then, 10 mL of 4% NaOH solution was added, and the mixture was thoroughly shaken again. The volume was adjusted to 25 mL with anhydrous ethanol, and the solution was shaken well and allowed to stand for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at 510 nm, with rutin serving as the standard.

Determination of carotenoid content

With slight modifications based on the experimental design, the method described by Suo et al.18 was followed. Specifically, 0.2 mL of pumpkin juice was pipetted and mixed with 8 mL of anhydrous ethanol and 6 mL of hexane. The test tubes were then sealed with tin foil and placed in a low-temperature shaker at 4 °C for 1 h. Afterward, 2 mL of distilled water was added, and the shaking was continued for an additional 5 min. Finally, all samples were allowed to stand for 10 min. Subsequently, the absorbance of the hexane phase samples was measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The values for β-carotene (λ = 450, E1cm 1% = 2560, M.Wt = 537) , α-carotene (λ = 444, E1cm 1% = 2800, M.Wt = 537) , β-cryptoxanthin (λ = 451, E1cm 1% = 2460, M.Wt = 553) , zeaxanthin (λ = 451, E1cm 1% = 2480, M.Wt = 569) , and lycopene (λ = 472, E1cm 1% = 3450, M.Wt = 537) were calculated using the equations:

In this formula, X—Carotenoid content, in unit of mg/L, Anm—The measured absorbance at the specified wavelength. M.wt—The molecular weight of the predominant carotenoid used as a standard, in unit of g/mol, V—The total volume of the extract, in unit of mL, m—The mass of the sample, in unit of g, E1cm1% —The specific absorptivity of the predominant carotenoid standard at the specified wavelength.

Rheological behavior

The measurement method was adapted slightly from Wang et al.14 for this experiment. Specifically, an HR-2 rheometer was used for the determinations. One milliliter of pumpkin juice sample was pipetted onto the base plate, with the gap size set at 0.056 mm and the temperature set at 25 ℃. In the study of steady flow, the shear rate range was set from 0.1 to 100 s−1, the frequency range was set from 0.1 to 10 Hz, and the rotor model is selected as Parallel plate rotor. These conditions were used to evaluate the shear stress, apparent viscosity, storage modulus, and loss modulus behavior of the pumpkin juice samples.

Extraction and analysis of volatile compounds

The experimental method and steps are slightly modified according to the experimental design based on Zhang et al.1. The volatile compounds were extracted via the HS-SPME technique. Five replicate experiments were conducted on pumpkin pulp. A 2 mL sample was accurately placed in a 20 mL vial. Subsequently, an internal standard of 1μL 3-nonanone (0.04 μg/μL, chromatographic ethanol as solvent) was added to the vial. Subsequently, the vial was immediately sealed and placed into a 45 ℃ water bath for equilibration and preheating for 10 min before extraction for 40 min. The extracted compounds were collected using an extraction needle (Perform an aging treatment at a high temperature of 270 °C for 1 h to remove any residues or contaminants on the extraction head.). Extraction was performed using an SPME fiber coated with divinylbenzene/carboxy/ polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS), purchased from Supelco (50/30 μm, USA)) into the gas chromatography injector. The extracted liquid was then injected into the GC–MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) inlet and desorbed for 6 min at 250 °C.

The chromatography conditions were J&WDB-5 quartz capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm). The temperature program was set as follows: initial column temperature of 45 °C held for 3 min, ramped at a rate of 5 °C/min to 140 °C, followed by a further increase at 10 °C/min to 220 °C, and maintained for 5 min. The injector temperature was maintained at 250 °C. Helium gas (99.999%) served as the carrier with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, and no split was applied during injection. Mass spectrometry was operated in electron impact (EI) mode at 70 eV, the transfer line temperature was set to 280 °C, while the ion source temperature was maintained at 230 °C, The mass scan range was m/z 35–350. Volatile compounds were identified by matching with the NIST library and confirmed by comparing their retention indices (RI), calculated using a C7–C40 n-alkane series under the same chromatographic conditions.

Sensory evaluation

Color, odor, taste, texture and Overall acceptability were selected as the evaluation criteria. The evaluation intensity ranged from 1 point (imperceptible) to 10 points (strongly perceptible). The sensory profile of the fermented pumpkin juice was assessed by a trained panel of 40 members (20 males and 20 females). This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangxi Science and Technology Normal University, no approval number has been given due to its low risk nature. Written informed consent was obtained from all panelists prior to their participation. Participants will be screened through questionnaires to exclude smokers, people with olfactory dysfunction and people allergic to the experimental samples, and then trained. The order of sample presentation to the panelists was randomized, and the panelists were required to rate the samples.

Analysis of data

All data are tested in three or more groups. The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The SPSS 22.0 software (Version 22.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was employed for the significance analysis (p < 0.05). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. The Origin 2021 software (OriginLab, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA) was utilized for graphing. TBTools were used for heat maps. The SIMCA 14.1 software (Umetrics, Malmö, Sweden) was applied to create a supervised model of orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS—DA) data, evaluating the relationships between multivariate data groups based on similarities and differences.

Results and discussion

Total bacterial count

The total bacterial count is used to assess the degree of bacterial contamination and the hygienic quality of pumpkin juice, reflecting whether the pumpkin juice meets hygienic standards during the fermentation process. The processing steps involved in pumpkin juice production have a certain impact on the total bacterial count in the juice. The total bacterial count shows remarkable differences under various treatment conditions. Fresh pumpkin juice, which has not undergone any processing, has a total bacterial count that represents the microbial flora present in the natural environment. However, once the pumpkin juice is sterilized by heat treatment, almost all of the natural microorganisms are inactivated. This effectively eliminates the native microbial load, creating a relatively clean starting point for subsequent fermentation. After subjecting pumpkin juice to high-pressure steam sterilization treatment, no bacterial growth was observed, indicating that the heat treatment was relatively effective in reducing contamination levels and eliminating the influence of contaminating microorganisms on subsequent fermentation of the pumpkin juice. Similar results were also reported by Laophongphit et al.19 in their study on heat-treated mango pulp. According to market requirements for the viable count of probiotic fermented foods, it is considered that only when the viable count exceeds 7 log CFU mL−1 can it fully exert beneficial effects on physical health20. In our study, the total number of colonies detected in the fermented pumpkin juice was 7.37 ± 0.02 log CFU mL−1 (Fig. 1D). This increase is a direct consequence of the proliferation of the inoculated beneficial microorganisms during the fermentation process. This indicates that the inoculated Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, utilized the nutrients in the pumpkin juice to generate energy for their growth and reproduction through reactions such as amino acid decarboxylation21 in the pumpkin juice. The growth of these bacteria in the pumpkin juice not only demonstrates the adaptability of the pumpkin juice to beneficial bacteria, but also suggests the potential probiotic functions of the fermented products, providing a basis for the development of it as a functional beverage.

The number of different strains in fresh and fermented pumpkin juice. Total number of colonies in fresh pumpkin juice (A), Number of Saccharomyces cerevisiae colonies in fermented pumpkin juice (B), Number of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Lactobacillus helveticus colonies in fermented pumpkin juice (C), Total number of colonies in fermented pumpkin juice (D). (The error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent replicates (n = 3). Here, it is expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The characters a, b, c in the upper right corner of the data indicate that there is a significant difference (p < 0.05)).

As shown in Fig. 1, in the fermented pumpkin juice samples, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Lactobacillus helveticus was detected at 7.17 ± 0.02 log CFU mL−1 (Fig. 1C), Saccharomyces cerevisiae at 6.83 ± 0.02 log CFU mL−1 (Fig. 1B). This difference may be attributed to Lactobacillus helveticus’s superior fermentation capacity and faster growth rate compared to other strains, while Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus exhibited relatively lower viable counts due to strain competition or environmental adaptation differences. During the fermentation process, the compounds produced by Lactobacillus helveticus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, such as bacteriocins, may also contribute to inhibiting microbial growth through the synthesis of hydrogen peroxide by these strains22. On the one hand, microbial strains may use the abundant carbon and nitrogen sources in pumpkin juice to maintain their survival rate, on the other hand, they may produce flavor substances and nutrients through metabolism. Overall, this indicates that Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus can colonize and grow on pumpkin juice as the substrate, and pumpkin juice provides the necessary conditions for fermentation for the probiotics.

Effects of different treatment conditions on physicochemical properties and bioactive substances content of pumpkin juice

pH, total acid content (TA), total soluble solids (TSS)

Total soluble solids refer collectively to substances, including sugars (such as monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides), acids, vitamins, minerals, and other compounds that are soluble in water. Table 1 presents the changes in total soluble solids content, total acid (TA) content, and pH values of pumpkin juice beverages under different treatment conditions. The TSS content of the pumpkin juice was 3.50 ± 0.00 oBrix when fresh and decreased to 1.50 ± 0.00 oBrix after fermentation. The reduction in TSS may be related to the bioconversion of soluble solids into lactic acid and their consumption as carbon and nitrogen sources for bacterial growth and metabolism23. Similarly, Laophongphit et al.19 also suggested that the decrease in total sugar content is associated with the decline in soluble solids. In the fermentation process of Solanaceae plants24 and apricot juice25, a similar decline in total soluble solids (TSS) was observed. However, a study conducted by Wang et al.8 found that the production of extracellular polysaccharides in the later stages of fermentation led to a slight increase in the TSS content. It is noteworthy that, compared to fresh pumpkin juice, the TSS content increased to 4.00 ± 0.00 oBrix after sterilization. This finding differs from that of Demir and Kılınç26, who observed no significant changes in TSS content and pH value after heat treatment of pumpkin juice. The reason for the increase in soluble solids may be that the cell walls of the pumpkin were damaged during the sterilization process, releasing acidic substances and nutrients from the pumpkin cells.

The maximum total acid content of pumpkin juice is 3.76 ± 0.14 g L−1 (lactic acid) in fermented pumpkin juice, while the minimum total acid content of pumpkin juice is in fresh pumpkin juice (0.46 ± 0.06 g L−1 (lactic acid)). Significantly different pH (5.10 ± 0.00) from fresh pumpkin juice was detected in pumpkin juice sterilized by high-pressure steam, which may be due to the release of natural organic acids and fatty acids during heat treatment. Sun et al.6 found similar results after heat-treating pumpkin juice. In contrast, Demir and Kılınç26 concluded that the total acid content of heat-treated pumpkin juice was not significantly different from that of fresh pumpkin juice. Meanwhile, Fermentation significantly reduced pH from 6.01 ± 0.01 to 3.81 ± 0.01. This may be attributed to the production of acidic metabolic products such as lactic acid and acetic acid, as well as the hydrolysis of proteins into smaller fragments like peptides and amino acids during the fermentation process, which result in a decrease in pH and an increase in total acid content. The same results regarding the total acid content were found by Sun et al.25 in the fermentation of apricot juice with Lactobacillus plantarum. During the growth and cell community formation of probiotics, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus utilize carbohydrate metabolic pathways to produce lactic acid and carbon dioxide27. This process leads to the acidification of pumpkin juice, as evidenced by the observed decrease in pH and increase in total acid content in this study. Koh et al.28 and Li et al.12 also hold consistent viewpoints on this matter. The low pH resulting from acidification can reduce the activity of undesirable microorganisms and their proliferative capacity29, lower the conductivity for the growth of pathogenic bacteria30, and inhibit the growth and reproduction of putrefactive and pathogenic bacteria, thus improving the microbiological stability and shelf-life of the product during storage. Fonseca et al.31 demonstrated an antimicrobial effect resulting from an increase in the concentration of acidic compounds, such as acetic and capric acids, as well as undissociated organic acids, under low-pH conditions. Notably, the production of multiple organic acids (primarily lactic acid) may result in a significantly lower pH in fruit and vegetable juices32. In our study, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus demonstrated the ability to metabolize organic acids during fermentation. Maintaining the pH of ingested food at 3.5–4.5 helps to lower the pH of the gastrointestinal tract and enhances the stability of probiotics33. In this study, the pH value of fermented pumpkin juice was maintained at 3.81 ± 0.01, which had a positive impact on the stability of probiotics. In conclusion, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus utilized pumpkin juice, which contains soluble solids such as sugars, acids, and vitamins, resulting in a significant decrease in pH and a significant increase in total acid content in the pumpkin-juice environment, this plays a crucial role in enhancing product safety, extending shelf life, and improving flavor and texture.

Color

The changes in the color of pumpkin juice subjected to various treatments are presented in Table 1. Pumpkin juice remained bright yellow in the fresh state, with a corresponding L* (Lightness Index) value of 33.93 ± 0.02, a* (Red-green Chroma Index) value of 4.00 ± 0.02, and b* (Blue-yellow Chroma Index) value of 10.33 ± 0.05. These values served as the control group. After the sterilization treatment of the pumpkin juice, there was a significant decrease in the values of a*, b*, c*, BI, and YI, while the L* value did not change significantly. Additionally, h0 and ΔE increased significantly, indicating that the redness and yellowness of the pumpkin juice decreased, whereas the lightness remained unchanged. The heat treatment conditions can effectively inactivate oxidases such as PPO and POD, which is the key reason for the oxidation of polyphenols and color deterioration in fruit and vegetable matrix, while the low pH environment, as an auxiliary factor, further inhibits the possible non-enzymatic oxidation reactions. Compared to fresh pumpkin juice, the fermented pumpkin juice exhibited a significant reduction in a* values by 13.75%. Conversely, significant increases occurred in b*, c*, h0, ΔE, BI and YI. However, no significant changes were noted in L* values. Significant differences in all parameters, except for L* and BI, were observed among fresh pumpkin juice, sterilized pumpkin juice, and fermented pumpkin juice.

In our study, there were no significant differences in L* values between fresh pumpkin juice and either sterilized or fermented pumpkin juice. In contrast, the findings of Suo et al.34 demonstrated a significant increase in L* values following the fermentation of jackfruit juice with probiotics. This increase, according to Wu et al.35, may be attributed to the reduction in turbidity caused by the consumption of nutrients by probiotics. There was a significant difference in the L value between sterilized pumpkin juice and fermented pumpkin juice, indicating that the brightness of the pumpkin juice was enhanced after fermentation.

Additionally, the variation in a* values may be attributed to the degree of thoroughness in removing the pumpkin peel during the sample preparation process. Compared with fresh pumpkin juice, the a* value of pumpkin juice subjected to sterilization and fermentation treatments decreased significantly, indicating a reduction in its redness intensity. This decrease might be attributed to the thermal treatment during sterilization, which caused the pigment in the cell vesicles of the pumpkin juice to overflow, thereby intensifying its greenness. our results share similarities with the findings of Sun et al.6, who observed that high temperature and prolonged heating resulted in lower a* and b* values, with a color shift towards greener and bluer hues. The significantly reduced red-green index after fermentation treatment suggests that this outcome is a consequence of microbial metabolic activities, substrate consumption, and product generation during the fermentation process. The decrease in the a* value of fermented pumpkin juice aligns with the findings of Mandha et al.10, who reported a similar decrease in a* values for juice fermented by Lacticaseibacillus casei and Pediococcus pentosaceus.

In the present study, the b* value of fermented pumpkin juice increased, indicating a shift in the color of fermented pumpkin juice towards yellow. Similarly, Mandha et al.10 reported a deepening of yellow color after the fermentation of mango juice, highlighting the potential for variations in color changes depending on the specific fruit and fermentation conditions. The yellowing of fermented pumpkin juice may be associated with the Maillard reaction36 and the degradation reaction of colored polymers37. At the same time, the production of certain colored compounds, such as total phenols and flavonoids, may also enhance the red and yellow tones in fermented pumpkin juice. The decrease in the b* value under sterilization conditions may be the result of the combined effects of several factors, including the degradation of carotenoids induced by high temperature, the breakdown of chlorophyll, or structural changes in anthocyanins.

The concurrent variations in a* and b* values significantly influence the magnitude of c*, h0 and BI parameters. In fermented samples, the elevation of both c* and h0 values indicates enhanced color saturation and a yellowish shift (60° < h0 < 90°, transitioning from orange to yellow), consistent with the observed b* value trends. Compared to fresh pumpkin juice, the fermented counterpart exhibited a chroma increase from 11.08 ± 0.04 to 11.38 ± 0.04, accompanied by a 3°–4° shift. These findings suggest that fermentation improves color vividness and purity through turbidity removal or pigment enrichmentl. Microbial metabolic activities, enzymatic reactions, and physical state modifications collectively optimize the color quality of pumpkin juice during fermentation.In contrast, sterilized samples demonstrated reduced c values alongside increased h0 values, likely attributable to thermal-induced binding between pigment compounds and pumpkin cell wall matrices. This process resulted in a brighter yellow hue but compromised color saturation. Collectively, our results reveal distinct color modifications under different processing conditions: sterilization caused degradation of the original vibrant coloration, whereas mixed bacterial strain fermentation can improve the color quality of pumpkin juice, thus enhancing the visual appeal.

In our study, compared with fresh pumpkin juice, the BI value of sterilized pumpkin juice decreased significantly, while that of fermented pumpkin juice increased markedly. This may be attributed to the fact that sterilization inactivated enzymes and microorganisms through high temperature, thereby interrupting enzymatic browning and the microorganism-driven Maillard reaction, resulting in a notable decrease in the BI value. In contrast, fermentation accumulated reducing sugars and amino acids through microbial metabolism and might directly participate in melanin synthesis, reactivating the browning reaction and leading to a significant increase in the BI value. These findings indicate that heat treatment and strain fermentation exert substantial impacts on the browning of pumpkin juice.

The YI value was primarily influenced by the L* value and b* value. The YI value of pumpkin juice after sterilization treatment decreased significantly, which could be attributed to the fact that heat treatment disrupted the cells of pumpkin juice, causing the cleavage of melanin polymers and the release of melanin, thereby masking the yellow color of the pumpkin juice. After fermentation, the YI value increased significantly, indicating an enhancement in the yellow hue of the pumpkin juice samples. This was mainly attributed to the component transformation and alteration in light absorption properties triggered by microbial metabolic activities, particularly processes such as carotenoid degradation, accumulation of Maillard reaction by-products, and oxidative polymerization of phenolic substances.

The variation in the ΔE value is concurrently influenced by changes in the L, a, and b* values. Although both sterilized and fermented pumpkin juices exhibited no significant alterations in the L* value and a notable increase in the a* value, the b* value demonstrated distinct trends, ultimately contributing to variations in the total color difference. In this study, the ΔE values of pumpkin juice samples subjected to sterilization and fermentation treatments were both significantly higher than those of fresh pumpkin juice, with ΔE of 0.87 ± 0.02 for sterilized pumpkin juice and ΔE of 0.66 ± 0.03 for fermented pumpkin juice. The sterilized and fermented pumpkin juices showed no perceptible differences in human sensory evaluation, as indicated by their ΔE values being below the visually detectable threshold (ΔE < 2)38. This suggests that probiotic fermentation does not significantly compromise the inherent color of pumpkin juice and it can well maintain the original color. Fermented pumpkin juice retains most of the color characteristics of fresh pumpkin juice, a finding consistent with the results reported by Patelski et al.38. This phenomenon may be attributed to the ability of lactic acid bacteria and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to sequester residual oxygen in the beverage, thereby preventing the auto-oxidation processes that lead to color degradation28. The findings of Fonseca et al.31 regarding the fermentation of passion fruit juice are consistent with our results, demonstrating minimal color changes (ΔE < 2) and preservation of the original color attributes. However, studies by Kardooni et al.20 and Degrain et al.24 reported significant color differences after fermentation, which may be attributed to the substantial production of colored compounds during the fermentation process.

Vitamin C content, total phenolic content, and flavonoid content

Vitamins, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids are closely associated with antioxidant activity. Specifically, these substances can act as free radical scavengers, donating electrons or hydrogen atoms to neutralize free radicals and thus prevent oxidative damage to cells. The higher the content of these substances, the more effectively they can combat oxidative stress, resulting in higher antioxidant activity. There were significant differences in vitamin C content, total phenolic content, and flavonoid content under different treatment conditions. As shown in Table 2, Vitamin C is a water-soluble antioxidant capable of scavenging free radicals, and the increase in vitamin C content in the fermented samples could also explain the enhanced antioxidant properties. Lactobacillus helveticus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus may indirectly increase the vitamin C content by converting the vitamin C precursor in the culture medium, this resulted in an increase of 23.45% in the vitamin C content of the fermented pumpkin juice compared to the fresh pumpkin juice (2.26 ± 0.18 mg/100 mL). This finding aligns with the results reported by Wang et al.13, who also observed that fermentation promotes the production of vitamin C. However, this finding contradicts the results of Liu et al.13, who reported the vitamin C content of Rosa roxburghii Tratt and coix seed beverage decreased with fermentation. Compared to fresh pumpkin juice, after the heat treatment during the sterilization process, the vitamin C content in the pumpkin juice decreased by 53.10%. On one hand, high-pressure steam sterilization disrupts the chemical bonds within vitamin C molecules through oxidation reactions, thereby converting them into other chemical substances. On the other hand, elevated temperatures induce the degradation of vitamin C.

The total phenolic and flavonoid contents of pumpkin juice fermented by Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus showed a significant increase, and the finding is consistent with the results of the study by Yang et al.39 on fermenting peony flowers with lactic acid bacteria. After fermentation with the composite strains, the total phenol content increased from 70.77 ± 1.19 mg GAE/100 mL (fresh pumpkin juice) to 106.31 ± 1.69 mg GAE/100 mL, which was 1.5 times the level before fermentation. The observed increase in total phenol content after fermentation may be attributed to the documented ability of the employed microorganisms (Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) to biotransform polyphenols. It is a plausible mechanism that microbial enzymes hydrolyze bound forms of polyphenols, such as glycosides, esters, and polymers40, thereby promoting the liberation of free phenolic compounds and small-molecule polyphenol monomers from the pumpkin matrix41. Additionally, microorganisms could utilize glucose via the shikimate pathway to produce phenylalanine, a precursor for phenolic compounds42. Conversely, Martín-Gómez et al.16, have reported a decrease in phenolic and flavonoid content after fermentation. This apparent discrepancy could be explained by several factors. On one hand, the same strains capable of releasing phenolics also produce enzymes—including decarboxylases, glycosyltransferases, and reductases43—which can further metabolize or transform these compounds, potentially leading to a net reduction in their content and altered oxidative activity. On the other hand, the decrease observed in other systems might result from competing processes such as the oxidation, condensation, and polymerization of polyphenols44 or their adsorption to microbial cell walls45. However, several studies have indicated that there is no significant change in total phenol and total flavonoid contents after fermentation. This may be ascribed to a balance between the loss and increase of phenolic and flavonoid compounds during the probiotic fermentation process. The increase in total phenolic content in sterilized pumpkin juice to 83.59 ± 1.77 mg GAE/100 mL as compared to fresh pumpkin juice may be due to the fact that high temperatures disrupt cell structures, promoting the release of phenolics, and that thermal effects inhibit the activity of phenol-degrading enzymes.

According to Yang et al.30, an increase in total flavonoid content can enhance the antioxidant activity in fermentation samples. The flavonoid content increased from 0.01 ± 0.00 mg RE/mL before fermentation to 0.05 ± 0.00 mg RE/mL, representing a fivefold increase compared to the pre-fermentation level. This finding is consistent with that of Yin et al.17, who used Rhizopus oligosporus to ferment sweet potato pomace. Wang et al.13 suggested that the increase of soluble flavonoids may be due to the release of insoluble bound flavonoids from pumpkin cell walls into free flavonoids under the action of enzymes. Moreover, the change in flavonoid content might be related to the inherent instability of flavonoids, some of the phenolics in the pumpkin juice may be converted to flavonoids, which could account for the increase in flavonoid content observed in our study. Different studies have reported varying trends in flavonoid and phenolic content during fermentation. For example, Wang et al.8 found that when probiotics were used to ferment pear juice, the total phenolic content increased while the flavonoid content decreased. Similarly, Wu et al.35 observed a gradual decrease in total phenolic and flavonoid content in grape juice during Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation. The decrease in flavonoid content may be attributed to the depletion or conversion of flavonoids by the growth and metabolic activities of the microorganisms. The increase in flavonoid content in pumpkin juice after sterilization, similar to the increase in total phenol content, may be attributed to the combined effects of physical release, chemical transformation, and enzyme inhibition. In conclusion, fermentation with mixed strains resulted in a significant increase in the vitamin C, total phenolic, and flavonoid content of pumpkin juice, thereby enhancing the bioactivity of the juice and improving its antioxidant properties.

Carotenoid content

Carotenoids, primarily β-carotene, serve as the main pigments responsible for the orange and yellow coloration of pumpkin46. As shown in Table 2, the carotenoid profiles of pumpkin juice varied significantly across different treatments. In fresh juice, the α-carotene content was 0.62 ± 0.00 mg/L, which decreased to 0.43 ± 0.00 mg/L after heat treatment, likely due to thermal degradation. In contrast, fermentation for 27 h increased the α-carotene content to 0.82 ± 0.00 mg/L. This enhancement may be attributed to microbial enzymatic activities—such as the action of pectinases and cellulases—that disrupt plant cell walls, facilitating the release of bound carotenoids47. At the same time, microbial β-glucosidase may hydrolyze the glycosidic bonds of carotenoid esters to convert the bound state to free state23, thus increasing its content and bioavailability. Both α- and β-carotene function as vitamin A precursors and contribute to the synthesis of coenzyme Q10, a compound involved in antioxidant and anti-aging processes in humans48. Consistent with our findings, Xu et al.9 reported stronger Raman spectral signals for carotenoids and β-carotene in fermented carrot juice compared to unfermented samples.

The content of β-carotene, slightly higher than that of α-carotene, also followed a similar trend: 0.70 ± 0.00 mg/L in fresh juice, 0.47 ± 0.01 mg/L after sterilization, and 0.91 ± 0.00 mg/L after fermentation. These results align with studies by Xu et al.9 and Mantzourani et al.49, who observed increased β-carotene levels post-fermentation. However, Contrary to our findings, Szutowska et al.50 showed that curly kale juice fermented with LAB strains reduced the amount of lutein and beta-carotene, respectively. The reduction in carotenoids after sterilization, as observed in our study and supported by Laophongphit et al.19, may be attributed to the highly unsaturated structure of carotenoids, which renders them susceptible to oxidation and thermal degradation. Gies et al.51 similarly noted carotenoid loss following heat treatment but found no adverse effects from fermentation.

β-Cryptoxanthin, a carotenoid with demonstrated anticancer, cardiovascular-protective, and immunomodulatory functions52, increased by 29.33% after fermentation but decreased by 33.33% after sterilization compared to fresh juice. Zeaxanthin and its isomer lutein, both potent antioxidants essential for retinal health and obtained solely through diet53, were also influenced by processing. The zeaxanthin content in fresh juice was 0.76 ± 0.00 mg/L, which decreased to 0.51 ± 0.00 mg/L after sterilization but increased to 0.99 ± 0.01 mg/L after fermentation. No significant difference was observed between zeaxanthin and β-cryptoxanthin contents. While heat treatment likely induced the loss of both carotenoids, fermentation appears to promote their accumulation through microbial regulation of enzymatic activities and metabolic pathways23.

Lycopene, commonly found in red plant tissues and known for its health benefits, is catalyzed by lycopene cyclase to form β-carotene54. In this study, lycopene content was 0.44 ± 0.00 mg/L in fresh juice, decreased to 0.29 ± 0.00 mg/L after sterilization—likely due to oxidative decomposition—and increased to 0.57 ± 0.01 mg/L after fermentation. This increase suggests that microbial activity may facilitate the release of lycopene from plant matrices32, a finding consistent with reports that fermentation improves lycopene bioaccessibility in tomato juice11.

Overall, sterilization reduced carotenoid content, whereas fermentation increased it—a trend partially consistent with Janiszewska-Turak et al.55, who reported heat-induced carotenoid loss but only a slight decrease during fermentation. The discrepancy may stem from differences in microbial strains or raw materials. Our study demonstrates that fermentation not only preserves but enhances carotenoid levels in pumpkin juice.

Effects of different treatment conditions on rheological properties of pumpkin juice

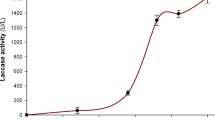

The changes in rheological properties of pumpkin juice samples with different treatments are shown in Fig. 2, which indicates that the shear stress and apparent viscosity of the pumpkin juice changed significantly under various treatment conditions. In fresh pumpkin juice, when the shear rate was increased from 0.1 to 100 s−1, the trend of shear stress change was not evident. The shear stress of sterilized pumpkin increased from 1.60 to 3.42 Pa with the change of shear rate, while that of fermented pumpkin increased significantly from 2.39 to 4.08 Pa with the increase of shear rate, and the shear stress of both pumpkin changed significantly. Still, the apparent viscosity of all the samples showed a decreasing trend. The apparent viscosity of fresh pumpkin juice decreased from 1.95 Pa.s to near 0, while that of sterilized pumpkin juice decreased from 2.69 to 0.03 Pa.s, and that of fermented pumpkin juice decreased from 3.78 to 0.04 Pa.s. Ultimately, the apparent viscosity of all samples stabilized. The viscosity of pumpkin juice decreased with the increase in shear rate and then levelled off at a specific shear rate, which showed the phenomenon of shear thinning. The reason for this may be that when the shear rate is suddenly increased, the molecular structure of the pumpkin juice is disrupted, and the intermolecular bonding becomes weaker, leading to a decrease in viscosity. The shear stress of pumpkin juice was significantly lower for fresh samples than for sterilized and fermented samples. There was also a significant difference between sterilized and fermented samples. Still, they had the same trend (Fig. 2A). Similar to the shear stress results, the apparent viscosity of the fresh pumpkin juice samples was significantly lower than that of the sterilized and fermented samples. There were also differences between the sterilized and fermented samples. Still, they had the same trend (Fig. 2B). The heat treatment of sterilized samples resulted in significantly higher shear stress and apparent viscosity than fresh pumpkin juice, probably due to the increase in the interaction forces between internal molecules of the pumpkin juice after heat treatment. This study aligns with the findings of Siddique et al.56, who concluded that heat treatment increases the viscosity of beverages and suggested that a high content of soluble solids also affects beverage viscosity. However, our findings differ from those of Manzoor et al.57, who used heat treatment on sugarcane juice, which resulted in an increase in shear stress but a decrease in apparent viscosity after heat treatment. In this study, the heat treatment during sterilization induced an increase in viscosity, which may be attributed to the high pectin content in pumpkin. The pectin molecular chains likely formed three-dimensional network structures through hydrogen bonding or calcium ion bridging during thermal sterilization58. This crosslinking effect significantly enhanced the viscoelasticity of the solution, resulting in elevated viscosity. Simultaneously, particulate components in pumpkin juice, such as pulp fibers and cell debris, may undergo flocculation upon heating due to protein denaturation or alterations in surface charge59. The flocculated particles formed larger aggregates through physical entanglement, increasing fluid resistance and thereby raising the viscosity. The highest shear stress (4.08 Pa) and apparent viscosity (3.78 Pa.s) of pumpkin juice fermented with composite strains indicated that probiotic fermentation increased the shear stress and apparent viscosity of pumpkin juice, probably due to the combination of several factors such as the production of microbial metabolites (such as polysaccharides and gases), the accumulation of organic matter, and the temperature change. This result is in agreement with the findings of Dan et al.5. Their study revealed that the percentage of Lactobacillus bulgaricus added had a significant impact on the viscosity of yoghurt.

The variation of energy storage modulus and loss modulus of different treated pumpkin juices is shown in Fig. 2. The fermented pumpkin juice (Fig. 2C), compared to fresh pumpkin juice, showed a significant increase in energy storage modulus at the same frequency (from 3.47 to 4.66 Pa). Whereas the loss modulus of the other treated pumpkin juice samples showed a significant increasing trend with increasing frequency compared to the fresh samples. The loss modulus of sterilized pumpkin juice increased from 2.28 Pa to 4.14 Pa, while that of fermented pumpkin juice increased significantly from 3.10 Pa to 5.04 Pa. At the same frequency, the energy storage modulus and loss modulus were the highest in the fermented samples, followed by the sterilized and fresh samples. As shown in Fig. 2D, The energy storage modulus and loss modulus of the fermented and sterilised samples were also significantly different, and both exhibited similar trends with increasing frequency, implying that pumpkin juice possesses significant viscoelastic properties and its internal structure and dynamic behaviour are relatively complex. The complex changes in the rheological properties of fruit and vegetable juices during processing also depend mainly on their variety and the concentration of fruit and vegetable juices60.

Effects of different treatment conditions on volatile components of pumpkin juice beverage

GC–MS analysis

The aromatic components of fresh pumpkin juice, sterilised pumpkin juice, and fermented pumpkin juice were extracted using headspace extraction and analysed by GC–MS. The volatile aromatic compounds were discussed and analysed using retention indices on the HP-5MS column in comparison with the library and its mass spectrum, as shown in Table 3. A total of 35 aroma substances were identified, which can be classified into five categories: 9 esters, 8 aldehydes, 5 ketones, 5 acids, 5 alcohols and 3 other substances. The cluster heat map is shown in Fig. 3A. According to the clustering algorithm, the 9 samples were divided into 3 groups: fresh pumpkin juice, sterilised pumpkin juice, and fermented pumpkin juice. Among them, fresh pumpkin juice and sterilized pumpkin juice could be clustered into one category, indicating a high degree of correlation between the two. This shows a certain degree of similarity in the types and contents of the standard components between fresh pumpkin juice and sterilised pumpkin juice. However, there are specific differences between these two types of juice and fermented pumpkin juice. Fermented pumpkin juice was clustered into a separate category, indicating significant differences between fermented pumpkin juice and the other two treatment conditions. The classification was conducted based on the volatile substances present in pumpkin juice. As shown in Fig. 3B, C, D, E, F, G represent the number and concentration of volatile compound types identified by GC–MS in different treatment groups. As shown in Fig. 3B, we can understand that 13 kinds of volatile compounds were detected in fresh pumpkin juice, 13 kinds of volatile compounds were detected in sterilized pumpkin juice, and 25 kinds of volatile compounds were detected in fermented pumpkin juice. Among them, only 5 kinds of volatile compounds were shared under the three treatment conditions, while 18 kinds of substances were only found in fermented pumpkin juice. As shown in Fig. 3C and D, there were significant differences in the types of volatile compounds identified by GC–MS among the different groups, and the concentration differences were also substantial. Compared to fresh pumpkin juice, sterilized pumpkin juice showed a significant increase in both the variety and content of aldehydes by 7.7% and 53%, respectively, while the types and levels of acids decreased by 15.4% and 35%. Regarding the change of volatile compound content, the ketone content decreased by 20% after pumpkin juice fermentation. The elevated sterilization temperature effectively reduced acidic compounds while promoting the growth of aldehyde species. In contrast, Compared with the fresh group, the amount and content of ester substances in fermented pumpkin juice were the highest, accounting for 36% and 43% of the volatile compounds in fermented pumpkin juice respectively, while the types and contents of aldehyde substances were significantly reduced, especially by 22%. Similarly, the alcohol content of fermented pumpkin juice was the highest under all three treatments. The abundance of esters and alcohols and the decrease of acids and aldehydes indicate that fermentation enhances the taste of pumpkin juice, making it richer and more intense. Figure 3E, F, G shows the contents of all compounds detected in fresh pumpkin juice, sterilized pumpkin juice and fermented pumpkin juice respectively. Different colors represent different kinds of substances, and the larger the circle, the higher the content of the compound.

Analysis of information on the volatile components of pumpkin juice under different treatment conditions using the GC—MS coupling technique. Heat map (A), Upset plot (B), A circular chart of the proportion of species (C), Content percentage bar stacking chart (D), Bubble pool plots (E–G), PCA (H), Plot of OPLS-DA Biplot (I); Plot of cross validation of 200 substitution test (K); VIP (Variable Importance for the Projection) plot (J), Sensory evaluation radar chart (L). Note: 1. (E–G): The bubble pool plots represent the classification of volatile substances detected by GC—MS. Fresh pumpkin juice (E), Sterilized pumpkin juice (F), Fermented pumpkin juice (G). The colors of the bubbles represent different categories, the sizes of the bubbles and the corresponding numerical values indicate the specific substance contents. 2. (J): The red part represents the key differential compounds with VIP > 1. Compound numbers correspond to Table 3 sensory evaluation analysis chart

Esters are the most diverse compounds found in pumpkin and provide a fruity, rich flavor to pumpkin juice. Esters are formed from alcohols and acids by lactose fermentation or amino acid degradation or by alcohol acetyltransferase biosynthesis on higher alcohols and acetyl coenzyme A substrates61. After fermentation treatment, both the variety and content of ester compounds increased. Four characteristic esters—Octanoic acid, ethyl ester, phenethyl acetate, and Nonanoic acid, ethyl ester—were newly identified in the fermented juice. Additionally, esters such as Octanoic acid, ethyl ester (20.66 ± 0.53 ug/mL), phenethyl acetate (26.11 ± 2.20 ug/mL), and Nonanoic acid, ethyl ester (10.51 ± 0.31 ug/mL) were exclusively detected in the fermented juice. Suffys et al.62 detected the same volatiles in Hakko Sobacha probiotic beverages. Ethyl octanoate, a metabolite derived from ethanol during fermentation, imparts a brandy-like aroma and contributes a pineapple-like flavor to fermented pumpkin juice. Phenethyl acetate is an ester compound produced through the reaction of 2-phenylethanol with acetyl-CoA63. It exhibits a floral rose-like aroma with notes of apple, cocoa, and whiskey. In the study by Holt et al.64, both ethyl octanoate and phenethyl acetate were detected and found to interact with other compounds in beer, contributing to their aromatic profile. Branched-chain esters such as ethyl caprate, which exhibit unique green and fruity aromas, are primarily derived from amino acid metabolism. Amino acids undergo transamination to form branched-chain keto acids, which are then converted into branched-chain alcohols and acyl-CoA through decarboxylation or dehydrogenation reactions. Finally, these intermediates are catalyzed by relevant enzymes to form branched-chain esters65. In the study by Wang et al.8, it was also suggested that an increase in acids and alcohols leads to an increase in the corresponding esters and that an increase in ester content produces more intense fruity and floral aromas. During fermentation, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus can produce a series of key extracellular enzymes with relatively high activity, such as β-glucosidase, lipase, protease and carbon–sulfur cleavage enzymes66, which can promote the release of esters and alcohols, thus leading to an increase in the ester content of pumpkin juice. Similar conclusions have been reached in the study of probiotic fermented carrot juice by Aihaiti et al.67.

Aldehydes are also important volatile substances in pumpkin juice. As shown in Table 3, the total relative content of aldehydes in pumpkin juice after fermentation decreased significantly, which may be because aldehydes were converted into other substances during the fermentation process by probiotics. The most representative compounds in pumpkin juice are benzaldehyde, benzaldehyde and nonaldehyde, which can be converted to each other through α-or β-oxidation68. In our study, compared with fresh pumpkin juice, no cassia bark aldehydes and phenylacetaldehyde were detected in fermented pumpkin juice. This may be because the aldehydes are first oxidized into corresponding carboxylic acids, which then undergo esterification with alcohols to form esters. This is closely related to the increase of ester compounds during the fermentation process. According to the studies conducted by Dan et al.5 and Rajendran et al.63, benzaldehyde was detected after microbial fermentation. In our research, although significant amounts of benzaldehyde (18.68 ± 4.27 ug/mL), phenylacetaldehyde (20.81 ± 0.29 ug/mL), and nonanal (27.35 ± 1.98 ug/mL) were produced during the heat treatment process, their concentrations were substantially reduced following fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. The significant formation of aldehydes during the heat treatment process may be attributed to the decarboxylation of amino acids induced by heating69, resulting in the generation of substantial aldehyde compounds. The reduction in benzaldehyde levels following fermentation is likely due to its conversion into alcohols and acids during the fermentation process70. The decrease in aldehyde content may be due to their non-enzymatic browning reaction with amino acids71. The findings of Yang et al.30 also demonstrated a reduction in aldehyde levels following fermentation. Although nonanal imparts a fresh floral and citrus aroma to pumpkin juice1, excessive concentrations of nonanal and benzaldehyde may pose health risks65. Thus, fermentation effectively reduced their concentrations. However, in the study by Li et al.12, elevated nonanal levels were observed in Lactobacillus acidophilus fermented jujube juice, contributing to citrus and cherry-like odor characteristics. In the study of Zhou et al.72, benzaldehyde and hexanal in soy whey form a characteristic bean odor, which is weakened by the addition of carrots.

Most ketones are produced via the microbial oxidation or decarboxylation pathway of fatty acids73. The total relative content of ketone volatiles in fermented pumpkin juice was drastically reduced by 19%, and the reduction of ketones may be due to the conversion of acids through lipid oxidation. In our study, the concentrations of ketones significantly decreased after heat treatment and probiotic fermentation. Although these compounds contribute to floral and fruity aromas in fermented samples, their reduction may be attributed to their conversion into β-carotene63. Fonseca et al.31 also suggested that fermentation can diminish the floral and fruity notes associated with ketones. However, the results of Wang et al.74 indicated a significant increase in total ketone content after fermentation, which may be attributed to the acidic environment induced by the mixed fermentation of probiotics, leading to the inhibition of β-oxidation-related enzymes. In fermented pumpkin juice, the variety of ketones is more abundant, adding more delicate and mellow milk and fruit aromas to the flavor of pumpkin juice. 2-Nonanone and 2-tridecanone were newly generated, contributing typical fruity aromas to the juice. Similarly, Chen et al.75 detected only nonanone in fermented apple juice using different lactic acid bacteria. However, in the study by Dan et al.5, 2-nonanone was detected in all samples and controls, imparting “buttery, creamy, and vanilla” flavors to yogurt.

In our study, certain compounds, such as acids, increased after fermentation. Acids synthesized from sugars via the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway63, can impart fruity and caramel-like flavours to pumpkin juice. The content of octanoic acid was detected in fermented pumpkin juice as 13.83 ± 2.16 ug/mL, similarly, In a study by Liu et al.15, octanoic acid was found to significantly contribute to the overall aroma profile of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus-fermented milk. The nonanoic acid (18.64 ± 0.43 ug/mL) and Propanedioic acid (11.72 ± 0.42 ug/mL) in fresh pumpkin juice give the pumpkin juice a cheesy aroma. Some people use Lactobacillus Swiss to ferment acid jujube juice, which provides the prominent acidity12. The type and content of alcohol compounds in fermented pumpkin juice increased significantly, among which the content of phenylethanol was increased to 29.88 ± 1.18 mg/mL. Phenylethanol was synthesised through the catabolic synthesis of amino acids leucine or phenylalanine63, which contributed to the rose flavour and honey flavour of pumpkin juice. Nonanol (11.7 ± 0.92 ug/mL), which was given a sweet waxy, floral and citrus aroma to fresh pumpkin juice, was not detected in fermented pumpkin juice, while 3-Methyl-1-butanol (17.35 ± 0.36ug/mL) was only detected in fermented pumpkin juice to give fermented pumpkin juice fruit and fermentation aroma. Alcohols, as crucial components in fermentation, can be synthesised through multiple metabolic pathways, including amino acid metabolism, glycolysis, methyl ketone reduction, and the degradation of linoleic and linolenic acids29. The increased concentration of alcohols not only enhances the metabolic transformation of esters but also leads to a reduction in aldehyde content.

An OPLS-DA model was constructed based on the contents of 35 volatile components in pumpkin juice. As shown in Fig. 3H, Distinct clustering patterns were observed, where fresh, sterilised, and fermented pumpkin juices formed three separate groups, with all samples tightly aggregated within their respective categories, revealing significant divergence in volatile profiles among the different processing stages. The established OPLS-DA model demonstrates excellent fitting parameters: R2x reaches 0.992 (a higher value indicates greater stability), while R2y stands at 0.967 (indicating stronger explanatory power). All reliability indices (Q2) remain within the 95% confidence interval, with Q2 exceeding 0.5 (signifying robust predictive performance). This result is consistent with that of Fig. 3A. The model validation results shown in Fig. 3 K demonstrate robust reliability through 200 permutation tests. Critical diagnostic parameters revealed: (1) The Q2 regression line intersects the vertical axis at Y < 0; (2) These validation metrics confirm the absence of overfitting and establish the model’s statistical validity1, as evidenced by the negative intercept and complete separation of actual Q2 from permuted distributions. According to Fig. 3I, the points farther from the origin indicate a greater contribution of the variable to the principal component, meaning that this variable has a greater influence in differentiating samples. In fresh pumpkin juice samples, propanedioic acid and 1-Nonanol contribute the most. In sterilized pumpkin juice samples, nonanal, benzeneacetaldehyde, and benzaldehyde make the most significant contributions. In fermented pumpkin juice samples, substances such as phenethyl acetate and ethyl caprylate, contribute the most. As shown in Fig. 3J, the variable importance in the projection (VIP) plot was used to identify the differential flavour components among fresh pumpkin juice, sterilised pumpkin juice, and fermented pumpkin juice. VIP value is mainly used to evaluate the contribution of each independent variable to the prediction ability of the model. The higher the VIP value, the greater the importance of the variable to the model. The components (VIP > 1, p < 0.05) were considered to have significant differences at the compound level. A total of 12 differential components were identified based on the criterion of VIP > 1, including ethyl caprylate, phenylethyl alcohol, phenethyl acetate, benzeneacetaldehyde, nonanoic acid, and nonanal, among others. These components play a significant role in distinguishing between the different states of pumpkin juice. The change in components with high VIP values indicates that key volatile compounds in fresh pumpkin juice—including benzaldehyde, phenylacetaldehyde, and nonanal—cease to be the major components in fermented pumpkin juice. In contrast, essential components like ethyl nonanoate, ethyl octanoate, and phenylethyl acetate in fermented pumpkin juice likely originate from the conversion of aldehydes. Ethyl nonanoate, characterized by coconut and fruity aromas, is formed via the esterification reaction between nonanoic acid and ethanol. Ethyl octanoate, which exhibits fruity and waxy aromas, is synthesized through the esterification of octanoic acid with ethanol64. Similarly, phenethyl acetate—possessing honey and rose-like aromas—is also produced by the esterification of acetic acid and phenethyl alcohol63. Notably, the precursors of these respective acids and alcohols may correspond to their homologous aldehydes. Aldehydes can be reduced to alcohols by alcohol dehydrogenase or oxidized into acids by aldehyde dehydrogenase, while esters are formed through the condensation of alcohols and acids76. This mechanism likely explains why pumpkin juice shows a significant decrease in aldehydes after fermentation, while the levels of esters and alcohols increase. This demonstrates that fermentation possesses the potential to transform aldehydes into desirable alcohols and esters.

Sensory evaluation

As shown in Fig. 3L, the mean score of color in the pumpkin juice samples was in descending order of composite strain fermented pumpkin juice, fresh pumpkin juice, and sterilized pumpkin juice, which is consistent with the result of the most significant color change in the sterilized pumpkin juice in the color assay. Wang et al.8 fermented pear juice using a mixture of three lactic acid bacteria, including Lactobacillus helveticus, which induced a slight colour difference that was likewise well accepted by the panellists. In terms of odour, it was observed that the panellists preferred the odour of fermented pumpkin juices, which is related to the fact that they are the richest in volatile substances, especially their unique aromatics. Furthermore, fresh and fermented pumpkin juices are flavoured to the highest degree because the original pumpkin flavour is preserved in both types of juice. Sun et al.6 used five species of Lactobacillus to ferment pumpkin juice and found that Lactobacillus helveticus fermented pumpkin juice samples had the most favourable odor and taste. In addition, the average score for the texture of fermented pumpkin juice was lower than that of fresh pumpkin juice. This might be because the fermentation strain grows and multiplies in the pumpkin juice, causing the overall texture of the pumpkin juice to appear less clear visually, which is unappealing to people. Fermented pumpkin juice became the most accepted product due to its pleasant smell and taste. The pleasant “fruit” and “sweet” attributes driven by the aforementioned esters show a strong positive correlation with overall acceptability scores in sensory evaluations. Fermented juices containing the highest concentrations of these pleasurable esters also achieved the highest preference ratings. Conversely, unfermented juices and sterilized juices with higher levels of “green grassy” and “irritating” aldehydes demonstrated significantly lower acceptability scores. This indicates that the metabolic activities of fermentation agents not only alter chemical components but also highlight flavor profiles that are more appealing subjectively to consumers. Therefore, the transition from plant-based aromas to fruit-flower scents is not merely a chemical observation but fundamentally contributes to the enhancement of product sensory acceptability. Ge et al.77 also observed higher overall ratings because the co-fermentation of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Lactobacillus plantarum resulted in yoghurts with a more desirable texture and viscosity.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that composite strain fermentation (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus helveticus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus) profoundly and favorably modifies the quality profile of pumpkin juice. In contrast to fresh and sterilized juice, fermentation significantly enhanced the functional properties of the product. This was evidenced by a substantial increase in bioactive compounds, including total phenolics, flavonoids, and carotenoids, alongside the attainment of a high viable count of 7.37 log CFU/mL, establishing its potential as a probiotic beverage. The composite strain utilized some of the soluble solids in the pumpkin juice for its growth and reproduction. It caused a decrease in the pH value and an increase in the total acid content. Additionally, the change of the pumpkin juice’s color was within an acceptable range. Critically, fermentation induced a fundamental shift in the volatile profile. The marked reduction in undesirable aldehydes and ketones, coupled with a significant increase in pleasant esters and alcohols—driven by microbial metabolic pathways—effectively enhanced the fruity and sweet aroma while mitigating off-flavors. Furthermore, the development of shear-thinning behavior and storage and loss modulus provided a desirable rheological texture. In summary, this work provides a solid foundation for developing fermented pumpkin juice as a novel functional food. The process not only adds value to pumpkin resources but also successfully improves the juice’s nutritional value, aroma, and sensory characteristics. For future commercial needs, subsequent research must focus on validating the product’s shelf-life, encompassing the stability of probiotic viability and key flavor compounds under refrigerated storage conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zhang, M. et al. Dynamic effects of ultrasonic treatment on flavor and metabolic pathway of pumpkin juice during storage based on GC–MS and GC-IMS. Food Chem. 2024, 142599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem (2025).

Shajan, A. E., Dash, K. K., Bashir, O. & Shams, R. Comprehensive comparative insights on physico-chemical characteristics, bioactive components, and therapeutic potential of pumpkin fruit. Fut. Foods 9, 100312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fufo.2024.100312 (2024).

Gavril, R. N. et al. Pumpkin and pumpkin by-products: A comprehensive overview of phytochemicals, extraction, health benefits, and food applications. Foods 13, 2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13172694 (2024).

Santos, L. C. et al. Study of heat treatment in processing of pumpkin puree (Cucurbita moschata). J. Agric. Sci. 9, 234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2022.102337 (2017).

Dan, T. et al. Influence of different ratios of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus on fermentation characteristics of Yogurt. Molecules 28, 2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28052123 (2023).

Sun, X. et al. Effects of lactic acid bacteria fermentation on chemical compounds, antioxidant capacities and hypoglycemic properties of pumpkin juice. Food Biosci. 50, 102126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2022.102126 (2022).

Yang, Y., Zhang, R., Zhang, F., Wang, B. & Liu, Y. Storage stability of texture, organoleptic, and biological properties of goat milk yogurt fermented with probiotic bacteria. Front. Nutr. 9, 1093654. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.1093654 (2023).

Wang, L., Zhang, H. & Lei, H. Phenolics profile, antioxidant activity and flavor volatiles of pear juice: influence of lactic acid fermentation using three lactobacillus strains in monoculture and binary mixture. Foods 11, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods1101001 (2021).

Xu, Y., Hlaing, M. M., Glagovskaia, O., Augustin, M. A. & Terefe, N. S. Fermentation by probiotic Lactobacillus gasseri strains enhances the carotenoid and fibre contents of carrot juice. Foods 9, 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121803 (2020).

Mandha, J., Shumoy, H., Matemu, A. O. & Raes, K. Evaluation of the composition and quality of watermelon and mango juices fermented by Levilactobacillus brevis, Lacticaseibacillus casei and Pediococcus pentosaceus and subsequent simulated digestion and storage. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 57, 5461–5471. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.15878 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. Fermentation of tomato juice improves in vitro bioaccessibility of lycopene. J. Funct. Foods 71, 104020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2020.104020 (2020).

Li, T. et al. Biotransformation of phenolic profiles and improvement of antioxidant capacities in jujube juice by select lactic acid bacteria. Food Chem. 339, 127859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127859 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Evaluation of chemical composition, antioxidant activity, and gut microbiota associated with pumpkin juice fermented by Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Food Chem. 401, 134122 (2023).

Wang, J., Wang, J., Vanga, S. K. & Raghavan, V. High-intensity ultrasound processing of kiwifruit juice: Effects on the microstructure, pectin, carbohydrates and rheological properties. Food Chem. 313, 126121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126121 (2020).

Liu, A. et al. Aroma classification and characterization of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus fermented milk. Food Chem. X 15, 100385. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOCHX.2022.100385 (2022).

Martín-Gómez, J., García-Martínez, T., Varo, M. Á., Mérida, J. & Serratosa, M. P. Phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity and color in the fermentation of mixed blueberry and grape juice with different yeasts. LWT 146, 111661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111661 (2021).

Yin, L. et al. Analysis of the nutritional properties and flavor profile of sweetpotato residue fermented with Rhizopus oligosporus. LWT 174, 114401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2022.114401 (2023).

Suo, G., Zhou, C., Su, W. & Hu, X. Effects of ultrasonic treatment on color, carotenoid content, enzyme activity, rheological properties, and microstructure of pumpkin juice during storage. Ultrason. Sonochem. 84, 105974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105974 (2022).

Laophongphit, A., Wichiansri, S., Siripornadulsil, S. & Siripornadulsil, W. Enhancing the nutritional value and functional properties of mango pulp via lactic acid bacteria fermentation. LWT 197, 115878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2024.115878 (2024).

Kardooni, Z., Alizadeh Behbahani, B., Jooyandeh, H. & Noshad, M. Probiotic viability, physicochemical, and sensory properties of probiotic orange juice. J. Food Meas. Charact. 17, 1817–1822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-022-01771-x (2023).