Abstract

To establish an effective radiological risk stratification feature for metachronous metastasis of colon cancer. This retrospective, single-center study enrolled patients with stage II/III colon cancer who underwent curative surgery between December 2016 and September 2020. The ecological spatial characteristics of tumor habitats at the Class-level and Landscape–level were extracted by landscape pattern analysis. Univariate and multivariate COX regression analysis were used to determine the spatial characteristics related to metachronous metastasis and included in the prediction model, and the landscape score value was constructed to stratified the risk of metachronous metastasis. The predictive performance was evaluated using the time-dependent area under the ROC curve (AUC). Metachronous metastases occurred in 31 of 93 patients (median age, 61 years, [IQR, 51–65 years]). GYRATE-MD (HR: 1.67[95%CI: 1.14, 2.45]; P < 0.05) and CIRCLE-MD (HR: 0[95%CI: 0, 0.41]; P < 0.05) were significantly associated with metachronous distant metastasis. The COX regression prediction model based on ecological spatial characteristics showed that the area under the ROC curve was 0.78 (95%CI: 0.65, 0.91) in the training set and 0.78 (95%CI: 0.58, 0.97) in the validation set in two years after surgery. The prediction model of tumor ecological spatial characteristics from landscape pattern analysis is helpful for risk stratification of metachronous metastasis in patients with stage Ⅱ/Ⅲ colon cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The primary treatment options for patients with AJCC stage II/III colon cancer involve radical surgical resection and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for patients at high risk of metachronous metastasis1,2. However, there is controversy regarding the use of adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, particularly in finding the right balance between the benefits and risks, as well as determining the appropriate timing and duration of chemotherapy. Metachronous metastasis of colon cancer is associated with a poor prognosis, and ESMO recommends more aggressive postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with high risk of metachronous metastasis1. Therefore, accurately identifying patients at high risk of metachronous metastases is crucial in aiding these patients to opt for more aggressive chemotherapy regimens and to consider prolonging chemotherapy duration. Recently, the perception of tumours has evolved, increasingly viewing them as an “ecosystem” consisting of tumour, immune, and stromal cells, representing a complex intercellular network3,4.Therefore, the analysis of the internal relationship of tumor ecosystem is of great significance for understanding the biological behavior of tumor and improving the level of tumor treatment5,6.

The vascular microenvironment plays a crucial role in influencing metachronous metastasis7. Contrast enhanced CT scans provide insights into the tumor vascular microenvironment8. The arterial phase delineates the feeding vessels supplying blood to colon cancer, while the venous phase elucidates the presence of dysfunctional neovascularization and the dispersion of contrast agents within the interstitial space9. Hence, in this study, we used preoperative enhanced CT images of colon cancer to develope a landscape ecological map of the vascular microenvironment. Furtherly, the landscape ecological analysis was used to investigate the spatial characteristics of the vascular microenvironment in colon cancer to characterize the ecological relationship of the vascular microenvironment in the colon cancer ecosystem10, and further explore the relationship between it and metachronous metastasis.

Thus, our study aimed to develop and validate a ecological spatial model that employs landscape ecological spatial traits for individualized risk stratification associated with metachronous metastasis in patients with AJCC stage II/III colon cancer.

Materials and methods

Patient enrolment

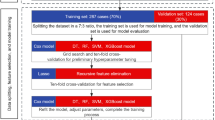

All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of the China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University waived the need of obtaining informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A total of 367 patients diagnosed colon cancer between December 2016 and September 2020 were included retrospectively. Inclusion criteria included: (a) patients with histopathologically confirmed colon adenocarcinoma undergoing radical resection, (b) preoperative enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning performed within 1 week prior to resection, and (c) no prior history of any other tumour. Exclusion criteria were: (a) distant metastases at the first diagnosis, (b) other concurrent neoplastic diseases at the initial examination, (c) Stage I, (d) recurrence or metastasis of the tumour within 6 months after the operation, (e) serious artifacts on the CT images, (f) the mismatch in tumour arterial and venous phase locations, (g) lost to follow-up, (h) incomplete clinical data(Fig. 1).

Sample matching

To mitigate the impact of baseline differences in demographic and clinical characteristics on the results, a propensity score matching (PSM) approach was employed to pair patients in the metastatic and non-metastatic groups11. The fundamental principle of propensity scoring is to substitute multiple covariates with a single score to achieve balance in the distribution of covariates between the metastatic and non-metastatic groups. To diminish bias against selection, confounders in non-metastatic studies are balanced akin to randomisation. We employed sample propensity matching using the MatchIt (version 4.5.5) R package, applying the ‘nearest’ method and a matching ratio of 2. Matching factors encompassed age, gender, CEA, CA199, tumour location, TNM stage, tumour differentiation grade, vascular invasion, and postoperative chemotherapy (yes or no)12,13,14. Ultimately, 93 patients were included, with 31 in the metastatic group and 62 patients in the non-metastatic group.

Data collection

Clinical, pathological, and imaging data were retrieved from electronic medical records. Postoperative follow-up was grounded on the patient’s fundamental status and tumour characteristics.Follow-up was performed every 3 months during the first 6 months after surgery and every 6 months thereafter. Follow-up extended from the surgery date to the last follow-up or end-point occurrence (metachronous metastasis). In this study, metachronous metastasis was defined as occurring after 6 months from the initial radical resection for colon cancer. Metastases were identified using enhanced CT, and two experienced imaging physicians(8years,12years) confirmed the presence of all metastases.

CT image acquisition

All arterial-phase and venous-phase CT images were extracted from a picture archiving and communication system (PACS; CAREstream Medical Ltd.) for subsequent image segmentation and analysis. Three types of multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners were employed in this study: 256-multidetector CT(Revolution, GE, USA), 64-multidetector CT(Discovery, GE, USA)and a third-generation dual-energy CT (SOMATOM Definition Force, Siemens, Germany). CT parameters: For 256-multidetector and 64-multidetector CT, the tube voltage is 120–140 kVp; the tube current is 100–280 mA; for dual-energy CT, the tube voltage is 120 kV and the tube current is CARE Dose 4D in automatic modulation mode; for other CT parameters, the two models were set the same, as follows: beam spacing, 0.6–1.07; matrix, 512 × 512 and Reconstruction thickness, 1 mm. A nonionic contrast agent (Ultravis 370, Bayer, Germany) was injected through the anterior elbow vein (flow rate, 4–5 mL/s), with the dose adjusted based on body weight (1.5 mL/kg). Scans were performed 25–30 and 70–80 s post-injection to acquire arterial and venous phase images.

Oncology ROI segmentation

The region of interest (ROI) was manually outlined on the enhanced CT images by one experienced radiologists(8 years) using the open-source ITK-SNAP software (version 3.8.0; www.itksnap.org). Perform registration of arterial and venous phase images before segmentation. And The ROI was delineated at the largest level of the tumor. She was unaware of the clinical and histopathological information of the colon rectal patients and determined the segmentation method before segmentation. The tumour segmentation process consisted of outlining the colonic tumour on each image and excluding peritumoral fat, adjacent air, bowel contents, and normal bowel wall tissue.

Habitat image generation and spatial relationship analysis

The arterial phase and venous phase images used to segment the images with ROI were imported into the open-source software nnFAE(version 0.1.0; https://github.com/salan668/FAE) for habitat generation15. For each tumour, the smallest voxel was grouped according to its similarity using k-means clustering, an algorithm that used the average Euclidean distance between individual voxels as a similarity measure. The final number of clusters was determined to be three. Finally, all voxels were grouped into three functionally consistent subregions. Consequently, three distinct tumour habitats of colon cancer were identified: Habitat1, Habitat2, and Habitat3. Landscape parameters for the created habitat map images were computed using ArcGIS (Version 10.1, Redlands, USA) and Fragstats (Version 4.2.1, Amherst, USA) software10,16. The overall process of vascular habitat imaging generation and spatial relationship analysis is shown in Fig. 2.The specific steps for the ecological spatial characteristics of habitats are shown in Appendix E1.

The overall process of tumor habitat generation and extraction of ecological spatial features. A: Image acquisition, registration and segmentation of the region of interest. B: Cluster analysis was used to classify the voxels of the region of interest into 3 categories. C: The generation of three habitats, Habitat1, Habitat2, and Habitat3 are shown in red, green, and blue, respectively. D: Habitat images are presented in the original tumor images. E: Extraction of ecological spatial features of 3 tumor habitats and landscapes.The extracted spatial characteristics included patch area, edge and degree of aggregation, such as SHAPE, CIRCLE. F: Establishment of prediction model for metachronous metastasis of colon cancer.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using the R language (R version 4.1.1) and SPSS for Windows version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Results were presented as medians with IQRs for continuous variables, and frequencies or percentages for categorical variables. Differences in clinicopathological factors between the metastatic and no metastatic groups were assessed using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U for continuous variables. Patients were randomly divided into training and validation sets in a 7:3 ratio.

Univariate analyses in the training set, using Cox proportional hazard regression, examined the association between habitat ecological spatial characteristics and metachronous metastasis. Factors at p < 0.1 were included in the multivariate Cox regression analyses, and p < 0.05 indicated that the factor was an independent predictor of the outcome. Variables with p < 0.05 were used to construct a multivariate Cox regression model for metachronous metastasis prediction. Time-dependent ROC curves were plotted using timeROC (version 0.4) to assess changes in the predictive ability of the model over time. Based on the model built in the training set, 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted for the training and validation sets, respectively. The model’s discrimination was tested by the area under the ROC curve. The concordance index (C-index) was used to evaluate the predictive performance of Cox regression model. Appropriate cut-off values were selected in each model using the surv-cut point in R. Patients were categorized into high-risk and low-risk groups, and the different risk groups were assessed by Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test. The test level was set at P < 0.05.

Result

Study sample characteristics

Between December 2016 and September 2020, a total of 367 patients were diagnosed with colon adenocarcinoma. After exclusion of 200 patients, a total of 167 patients met the study criteria, and 93 patients were finally included in the study on the basis of propensity matching (occurrence of metachronous metastases: absence of metachronous metastases as 1:2). Of the 93 patients, 53 were males, and 40 were females(median age, 61 years; interquartile range [IQR], 51–65 years). The basic clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. Among the 31 patients who developed metachronous metastases, 24 had single-organ metastases, and 7 had multi-organ metastases. The liver is the organ with the most heterogeneous metastases (21 cases, 66%)(Table 1). The median time to the occurrence of metastases was 14 months (IQR,10–22 months).

Screening of ecological spatial features

Spatial characteristics were extracted in Class-levle and Landscape–level of each habitat. Spatial characteristics of each habitat were extracted separately for each patient, based on patch type and landscape. Multivariate analysis suggested that GYRATE-MD (HR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.14, 2.45, P < 0.05) and CIRCLE-MD (HR: 0, 95% CI: 0, 0.41, P < 0.05) in Habitat1 were significantly associated with metachronous metastasis, which could be an independent predictor of metachronous metastasis (Table 2). In the training set, the mean values of GYRATE-MD and CIRCLE-MD in the metastasis group were 6.98 and 0.53, respectively, while those in the non-metastasis group were 6.48 and 0.56. Characteristics related to Habitat2, Habitat3, and Landscape-level were excluded.

Evaluation and validation of Cox regression models

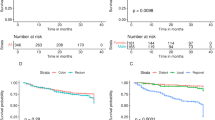

Time-dependent ROC curves were employed to assess the predictive capability of the COX regression model constructed using ecospatial features. Figure 3 illustrates the time-dependent ROC curves for diagnosing metachronous metastasis of colon cancer in both the training and validation sets.

Additionally, ROC curves were constructed at time points of 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively, and Fig. 4 presents the area under the ROC curve (AUC) of the predictive model. In the training set, the AUC values at the 2-year time point (AUC, 0.78; 95% CI: 0.65, 0.91) exceeded those at the 1-year (AUC, 0.56; 95% CI: 0.33, 0.80) and 3-year (AUC, 0.73; 95% CI: 0.58, 0.89) time points. Calibration curves were plotted at the 2-year mark to represent the calibration of the model, and decision curves were generated to depict the clinical utility of the model are shown in Appendix E2. The C-index of the model in the training set and validation set was 0.71 and 0.65, respectively. To further validate the stability of the model, we performed a 5-fold cross-validation within the training set. The AUC values of all five groups exceeded 0.7 (Appendix E3), further attesting to the robustness and generalization ability of the model.

Patient stratification using the habitat risk score

To facilitate the application of this model by clinicians, we transformed the linear predicted values of the variables into a survival function using cph(Table 3). This enabled us to demonstrate the predicted probability, also known as the landscape score, of metachronous metastasis of the tumor at the particular time point of interest in the nomogram described in Appendix E4.

The probability of predicting metachronous metastasis in colon cancer patients at the 2-year postoperative time point using landscape scores is shown in Fig. 5. As the landscape score value increased, the probability of metachronous metastasis in patients showed an overall trend of gradual decrease (due to the small number of values less than 0.4, those with a score value of 0 to 0.4 were divided into a group, and then those with landscape score values of 0.4 to 0.6, 0.6 to 0.8, and 0.8 to 1 were divided into a group, respectively).

Subsequently, we stratified all patients in the validation and training sets for the risk of metachronous metastasis 2 years after radical surgery for colon cancer (cutoff value chosen as 0.53). 11 patients (12%, 11/93) were stratified into the high-risk group, and 82 patients (88%, 82/93) were stratified into the low-risk group.Survival comparisons between patients with colon cancer suggested a higher odds of metastasis in patients with high risk than in patients with low risk(P < 0.0001)(Fig. 6).

Discussion

Prediction of patients at high risk of metachronous metastasis from colon cancer can assist in the postoperative management of patients. In this study based on ecological spatial characteristics of stage AJCC II/III colon cancer, we constructed a ecological spatial model to risk-stratify high- and low-risk metachronous metastases, achieving optimal prediction at 2 years post-diagnosis with an area under the ROC curve of 0.78.

The tumour vascular microenvironment plays an important role in tumour growth and metastasis7. Previous studies have demonstrated that habitat imaging can reveal the spatial heterogeneity of the vascular microenvironment by constructing the vascular habitat of a tumor17, which has proven useful in predicting the prognosis of glioma by MRI imaging18,19. Also, the contrast-enhanced state of the tumour in enhanced CT images reflects the complex vascular characteristics within the tumour and can reflect the vascular microenvironment of the tumour at a macroscopic level8,9. We constructed a landscape image of the vascular microenvironment in colon cancer by utilizing contrast-enhanced CT images, comprising three distinct habitats. Habitat1 represents the vascular microenvironment of the tumour with high blood supply and neovascularisation, Habitat2 represents the vascular microenvironment of the tumour with high blood supply and low neovascularisation and Habitat3 represents the vascular microenvironment of tumours with low blood supply and high neovascularisation.

In natural ecology, the spatial relationship of ecological communities is an important factor influencing the behaviour of organisms20,21. Biologists commonly use landscape spatial pattern analysis to study both the structural composition and spatial relationships of ecological landscapes22. Tumour is a multi-component mixed ecosystem4, where the spatial relationships among diverse ecological communities are crucial in tumor evolution and development. We employed landscape spatial pattern analysis to explore the landscape patterns and ecological spatial relationships within the CT vascular habitat of colon cancer, aiming to explore its association with colon cancer metastasis.

Following the COX regression analysis of ecological spatial characteristics in our study, two characteristics—GYRATE-MD and CIRCLE-MD—were identified as correlated with metachronous metastasis in Habitat1. Habitat1 is characterized by a significant increase in tumour blood supply and neovascularization, which is indicative of the tumour’s high oxygen demand and disorganized neovascularization. This aberrant vascular system in the tumour results in a hypoxic microenvironment, which in turn promotes tumour cell metastasis23,24,25. GYRATE, representing the radius of gyration, reflects landscape continuity and the extent of a patch. In ecological terms, an increase in patch extension correlates with a higher success rate in species dispersion26.The mean value of the GYRATE indicator in the metastatic group was 6.98, which exceeded the 6.48 in the non-metastatic group (HR: 1.67,95% CI: 1.14,2.45, P < 0.05). In the context of larger patch extension, tumor cells in the metastatic group have a higher likelihood of distant metastasis.CIRCLE represents the related circumscribing circle used to differentiate the patch shape. A smaller value indicates a more rounded plaque shape, which may reduce interactions with the surrounding environment and lead to the accumulation of material within the plaque27. The CIRCLE indicator for the metastasis group was 0.53, lower than the non-metastasis group’s 0.56 (HR: 0, 95% CI: 0, 0.41, P < 0.05), indicating the plaques were closer to round. The tumor microenvironment of colon cancer is prone to producing lactic acid28,29, which is actually an important factor for tumor metastasis30. Consequently, we think that the patches in the metastatic group facilitate the accumulation of lactic acid, potentially driving tumor progression and metastasis.

We attained risk stratification for metachronous metastasis of colon cancer by investigating the spatial characteristics of its vascular habitat, yielding an area under the ROC curve of 0.78.In the research on predicting metachronous metastasis of colon cancer, Li Y. et al. used the radiomics to explore the venous phase of colon cancer on contrast-enhanced CT, achieving an AUC value of 0.7931. Our predictive efficacy was comparable. However, radiomics lacks biological interpretability and is difficult for clinicians to understand, which is not conducive to clinical application. In our study, we analysed the ecospatial characteristics of colon cancer habitats and linked them to the vascular microenvironment of the tumour.This approach illuminates the influence of the structural pattern of the colon cancer landscape on the tumour microenvironment, offering greater applicability in clinical settings.

Some limitations persist in this study. Firstly, as a single-centre retrospective study, there exists a potential for bias, but we introduce a novel method to investigate macroscopic spatial heterogeneity within tumours, offering a new perspective in tumour ecology research. Secondly, as unavoidable intestinal peristalsis make some patients excluded due to mismatched tumour images between arterial and venous phases, indicating a need for more precise image alignment techniques in larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Constructing ecological spatial characteristics of CT landscapes of vascular microenvironment of colon cancer based on landscape pattern analysis method can be used to risk stratify metachronous metastasis of stage II/III colon cancer

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Argilés, G. et al. Localised colon cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 31, 1291–1305 (2020).

Benson, A. B. et al. Colon Cancer, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 19, 329–359 (2021).

McAllister, S. S. & Weinberg, R. A. Tumor-Host interactions: A Far-Reaching relationship. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4022–4028 (2010).

Chen, X. & Song, E. The theory of tumor ecosystem. Cancer Commun. 42, 587–608 (2022).

Daoust, S. P., Fahrig, L., Martin, A. E. & Thomas, F. From forest and agro-ecosystems to the microecosystems of the human body: what can landscape ecology tell Us about tumor growth, metastasis, and treatment options? Evol. Appl. 6, 82–91 (2012).

Alfarouk, K. O., Ibrahim, M. E., Gatenby, R. A. & Brown, J. Riparian ecosystems in human cancers. Evol. Appl. 6, 46–53 (2012).

Quail, D. F. & Joyce, J. A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med. 19, 1423–1437 (2013).

Tsurumaru, D. et al. Histopathologic diversity of gastric cancers: relationship between enhancement pattern on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT and histological type. Eur. J. Radiol. 97, 90–95 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Extent of enhancement on multiphase contrast-enhanced CT images is a potential prognostic factor of stage I–III colon cancer. Eur. Radiol. 29, 1114–1123 (2018).

Kupfer, J. A. Landscape ecology and biogeography: rethinking landscape metrics in a post-FRAGSTATS landscape. Progress Phys. Geography-Earth Environ. 36, 400–420 (2012).

Abadie, A. & Imbens, G. W. Matching on the estimated propensity score. Econometrica 84, 781–807 (2016).

Hao, M. et al. Predicting metachronous liver metastasis in patients with colorectal cancer: development and assessment of a new nomogram. World J. Surg. Oncol. 20, 80 (2022).

Shida, D. et al. Prognostic impact of primary tumor location in stage III colorectal cancer-right-sided colon versus left-sided colon versus rectum: a nationwide multicenter retrospective study. J. Gastroenterol. 55, 958–968 (2020).

Lu, Z. et al. A nomogram prediction model based on clinicopathological combined radiological features for metachronous liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. J. Cancer. 15, 916–925 (2024).

Song, Y. et al. FeAture explorer (FAE): A tool for developing and comparing radiomics models. Plos One. 15, 10 (2020).

Zhao, Q. J., Wen, Z. M., Chen, S. L., Ding, S. & Zhang, M. X. Quantifying land Use/Land cover and landscape pattern changes and impacts on ecosystem services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 21 (2020).

Gatenby, R. A., Grove, O. & Gillies, R. J. Quantitative imaging in cancer evolution and ecology. Radiology 269, 8–15 (2013).

Kim, M. et al. Vessel size and perfusion-derived vascular habitat refines prediction of treatment failure to bevacizumab in recurrent glioblastomas: validation in a prospective cohort. Eur. Radiol. 33, 4475–4485 (2022).

Verma, R. et al. Tumor Habitat–derived radiomic features at pretreatment MRI that are prognostic for Progression-free survival in glioblastoma are associated with key morphologic attributes at histopathologic examination: A feasibility study. Radiology: Artif. Intell. 2, e190168–e190180 (2020).

Bar-Massada, A., Wood, E. M., Pidgeon, A. M. & Radeloff, V. C. Complex effects of scale on the relationships of landscape pattern versus avian species richness and community structure in a woodland savanna mosaic. Ecography 35, 393–411 (2012).

Holt, A. R., Gaston, K. J. & He, F. L. Occupancy-abundance relationships and Spatial distribution: A review. Basic Appl. Ecol. 3, 1–13 (2002).

Tischendorf, L. Can landscape indices predict ecological processes consistently? Landscape Ecol. 16, 235–254 (2001).

Zhong, H. et al. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in common human cancers and their metastases. Cancer Res. 59, 5830–5835 (1999).

Lee, S. T. et al. Prevalence of hypoxia and correlation with glycolytic metabolism and angiogenic biomarkers in metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 48, 1585–1592 (2020).

Qian, J. & Rankin, E. B. Hypoxia-Induced phenotypes that mediate tumor heterogeneity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1136, 43–55 (2019).

Yang, C., Zhan, Z., Zong, S. & Ren, L. The relationship between landscape patterns and populations of Asian longhorned beetles. Forests 13, 12 (2022).

Mirzaei, M. et al. Configurationally analysis of relationships between land-cover characteristics and river water quality in a real scenario. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 18, 1877–1892 (2020).

Lu, C. W., Lin, S. C., Chen, K. F., Lai, Y. Y. & Tsai, S. J. Induction of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-3 by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 promotes metabolic switch and drug resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28106–28114 (2008).

Chiche, J., Brahimi-Horn, M. C. & Pouysségur, J. Tumour hypoxia induces a metabolic shift causing acidosis: a common feature in cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 14, 771–794 (2010).

Roland, C. L. et al. Cell surface lactate receptor GPR81 is crucial for cancer cell survival. Cancer Res. 74, 5301–5310 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Assessment of primary colorectal cancer CT radiomics to predict metachronous liver metastasis. Front. Oncol. 12, 861982 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciate Min Zhao, Master, from GE Healthcare, Beijing, China, for her assistance in the data processing and statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Yunxi Li, Mingxin Chen, Wei Wang, Mengchao Zhang participated in the material preparation, data collection and analysis. Yunxi Li, Mingxin Chen, Yang Song, Mengchao Zhang contributed to data interpretation. Yunxi Li, Mingxin Chen drafted the initial manuscript, which was further revised by Mengchao Zhang and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This retrospective clinical study received approval from the ethics committee of our hospital, with a waiver for written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Chen, M., Wang, W. et al. Risk stratification for metachronous metastasis in colon cancer based on landscape ecological analysis. Sci Rep 15, 44251 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26983-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26983-1