Abstract

In the pursuit of sustainable industrial operations, efficient energy management has become a critical challenge, particularly under scenarios where the electrical grid is restricted to serving industrial loads. This study addresses the urgent need for intelligent forecasting and scheduling frameworks by proposing a hybrid Gene Expression Programming Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (GEP-ANFIS) for predictive energy management in hybrid renewable energy systems. The model was evaluated using standard forecasting metrics. For solar PV prediction, GEP-ANFIS achieved low short- and long-term error rates, with MAPE values below 6% and 8%, respectively. For industrial load forecasting, the model exhibited high precision, maintaining MAPE values under 2.5% (short-term) and under 3.5% (long-term). These results demonstrate consistent improvements over conventional ANFIS and GEP models. Economic evaluation confirmed significant cost benefits. In a Grid-only configuration, GEP-ANFIS reduced daily energy costs by 7.4% compared to ANFIS. Greater efficiency was observed in PV and Battery-only and Grid-connected PV-Battery setups, where GEP-ANFIS achieved daily cost reductions of 6.5% and 6.3%, respectively. Over a 20-year planning horizon, the system recorded a 6.5% reduction over ANFIS and a 37.7% improvement over HOMER. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted to assess the robustness of the GEP-ANFIS model under varying solar PV power, and battery storage capacity. Results indicated the robustness, efficiency, and scalability of the GEP-ANFIS controller, especially in resource-constrained, PV-dominated microgrids, making it a strategic solution for sustainable industrial energy management while preserving battery longevity by avoiding deep discharge scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Uganda’s industrial sector faces significant energy challenges, primarily characterized by grid instability, high costs, and long-term financial burdens due to their reliance on the grid, exacerbated by rising energy demands and fluctuating prices. Despite abundant energy resources, including hydropower and biomass, only about 28% of the population has access to electricity, with urban areas, particularly slums, experiencing severe access deficits due to high tariffs and unreliable supply1,2. The high costs of electricity significantly impact small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), leading to increased production costs that make local goods less competitive compared to imports3,4. Additionally, the reliance on biomass contributes to environmental degradation and energy poverty, further complicating the energy landscape5,6. The implementation of energy policies has been hindered by bureaucratic challenges and financial constraints, which exacerbate the issues of accessibility and affordability7,8. Thus, addressing these challenges is crucial for Uganda’s socio-economic development and the sustainability of its industrial sector9.

The integration of smart grid technologies and demand-side management (DSM) strategies can mitigate these issues by optimizing energy usage and reducing operational costs10. For instance, implementing an energy management system (EMS) can lead to substantial savings, with one study reporting an annual cost reduction of nearly $3 million through effective load scheduling11. Additionally, DSM can reshape peak load profiles, further decreasing electricity charges and enhancing financial performance12,13. However, the instability of traditional power sources necessitates a shift towards microgrids and renewable energy solutions, which can provide localized energy supply and reduce dependence on the national grid, ultimately lowering long-term costs and emissions14. Thus, while the initial investment in these technologies may be high, the potential for significant long-term savings and reliability improvements justifies the transition (Mariappan15,16).

Demand-side energy management is pivotal in optimizing energy consumption patterns to improve efficiency, reduce costs, and stabilize energy grids17. DSM strategies involve leveraging demand-side resources (DSRs) to reshape load profiles while integrating distributed energy resources (DERs) for sustainability18,19. Effective practices include demand response programs, energy audits, and energy storage systems, enabling consumers to monitor and control their energy usage, particularly during peak periods20,21. Flexible DSM programs tailored to consumer constraints have shown success in reducing peak loads and encouraging participation, making DSM an essential component of sustainable energy strategies22,23.

Industrial facilities, as major electricity consumers, rely on sophisticated demand response (DR) systems to manage load efficiently. Strategies such as load shifting from peak to off-peak hours and curtailment during DR events have proven effective24,25. Intelligent systems, including fuzzy logic and expert systems, prioritize load adjustments while considering production schedules, inventory, and workforce constraints26,27. Furthermore, the flexibility provided by DR programs enables industries to reduce utility loads during energy crises, achieving substantial operational savings28.

Renewable energy sources (RESs) such as solar, wind, and biomass are increasingly integrated into DSM frameworks to reduce dependency on fossil fuels and minimize environmental impact29,30. However, their intermittent nature necessitates the use of energy storage systems (ESS) for consistent energy supply31. Battery ESS, in particular, enhance operational efficiency and cost-effectiveness, supporting decentralized energy production and self-consumption in industrial applications32,33. Advanced hybrid EMSs incorporating technologies like hydrogen subsystems have further optimized energy use, extended storage lifespans, and improved overall system flexibility34,35. These innovations align with global sustainability efforts, emphasizing DSM’s role in creating resilient energy infrastructures.

The increasing demand for grid-connected systems is driven by global energy demand, urbanization, industrialization, and environmental concerns36,37. These systems, equipped with intelligent controllers, can reduce operational costs and improve energy management. Advanced technologies like Recurrent Neural Networks, Walrus Algorithm, Reinforcement Learning, Cuckoo Search Algorithm, Hippopotamus Algorithm, Ali Baba & Forty Thieves optimization and enable superior Maximum Power Point Tracking, adapting to environmental changes and improving energy output38,39,40,41,42,43. Additionally, AI-driven frameworks facilitate better forecasting, DSM, and energy storage optimization, enhancing grid stability and reducing reliance on costly peak power sources44,45. By leveraging these intelligent systems, businesses and consumers can benefit from lower electricity costs, increased reliability, and a more sustainable energy supply, contributing to a more cost-effective and eco-friendly energy landscape46,47,48.

Recent advancements in DSM leverage smart grid technologies to enhance communication between energy suppliers and consumers, enabling integration with distributed generation, energy storage, and demand response mechanisms49,50. These innovations address energy management across residential, commercial, and industrial domains, despite facing technical, economic, and regulatory challenges47,51. Optimization techniques, including hybrid approaches, have been shown to effectively address DSM challenges by rescheduling non-critical loads and shifting them to off-peak periods, enhancing efficiency and reducing costs for all stakeholders52.

Accurate forecasting is essential for effective EMS operations. Recent research integrates probabilistic Photovoltaic (PV) forecasting into control strategies for solar energy systems, optimizing energy injection into the grid and enhancing economic revenue. By predicting solar energy availability based on weather and time factors, EMS optimizes energy storage and electricity injection during peak periods. Comparisons between probabilistic and deterministic forecasting approaches highlight the importance of precise predictions in maximizing system reliability and revenue generation53,54. In microgrid applications, predictive models like Long Short-Term Memory networks facilitate EMS optimization. These models manage the state-of-charge (SOC) of battery ESS while ensuring cost-efficient operation of PV-dominated microgrids. Advanced decision algorithms, combined with economic and technical analyses, showcase the potential of EMS in achieving demand satisfaction and reducing operational costs without compromising equipment longevity55,56.

Forecasting renewable energy production is a cornerstone of EMS advancements. Support Vector Regression (SVR), for example, has demonstrated high accuracy in predicting solar PV and wind energy generation. By incorporating historical data, weather patterns, and grid conditions, SVR reduces forecast errors, contributing to optimized energy schedules and a reduction in operational costs by 8.4%37. Similarly, a bi-level EMS model combines day-ahead scheduling with real-time rescheduling to handle uncertainties in renewable sources like wind and solar. This approach employs a meta-heuristic algorithm, such as the Coronavirus Herd Immunity Optimizer, for scheduling and real-time optimization under fluctuating weather conditions, achieving economic and operational efficiency57.

Predictive EMS approaches also integrate fuzzy logic and rule-based algorithms for residential and microgrid PV-battery systems. For instance, in a study at Swansea University, a fuzzy logic-based Battery Management System reduced energy costs by 18% over six months and extended battery life by optimizing state-of-health and SOC decisions58. These predictive models demonstrate how accurate forecasting and rule-based strategies can minimize reliance on the utility grid while enhancing operational efficiency. The integration of AI-based techniques has revolutionized DSM, particularly in predictive energy management and optimization. AI techniques, such as artificial neural networks and ensemble methods like random forest and gradient boosting, have proven effective in forecasting energy demand and stabilizing renewable energy systems59,60,61. These tools enable better decision-making, energy cost reduction, and enhanced efficiency in grid-connected PV-battery systems.

Existing EMS face significant limitations in accurately predicting load behavior and optimizing the operation of grid-connected PV and battery systems. Traditional systems often struggle with the inherent variability of renewable energy sources, leading to inefficiencies and energy losses62. It is worth knowing that the forecasting modules for predicting solar irradiance, temperature, and load demand, combined with optimization modules for day-ahead scheduling, can improve economic operation of grid-connected microgrids63. However, the effectiveness of EMSs depends on various factors, including practical implementation, computational requirements, and data quality64. For instance, while some models utilize historical data for load forecasting, they may not effectively integrate real-time data or adapt to changing conditions, resulting in suboptimal performance65,66.

Moreover, conventional optimization techniques, such as genetic algorithms, can be computationally intensive and may not provide timely solutions for dynamic environments67. Recent advancements, such as the Intelligent EMS and hybrid models, show promise in enhancing predictive accuracy and operational efficiency by leveraging machine learning and real-time data integration65,68. However, the reliance on extensive data and computational resources remains a challenge, highlighting the need for more robust and adaptable EMS solutions66. Thus, while progress has been made, substantial gaps remain in the capability of EMS to fully optimize energy distribution in dynamic contexts.

In order to fully optimize the effectiveness of EMS, there is need for intelligent controllers in managing hybrid systems arises from the complexities and challenges associated with integrating multiple energy sources, particularly in renewable energy applications. These systems, which often combine solar, wind, and storage technologies, face issues such as intermittent energy supply, load fluctuations, and the necessity for real-time adaptability to changing environmental conditions69,70. Intelligent power management controls, particularly those utilizing fuzzy logic, have been proposed to enhance system responsiveness and efficiency by dynamically adjusting operations based on real-time data and predictive analytics71,72. Such controllers not only optimize energy utilization and stabilize voltage levels but also extend the lifespan of power sources by ensuring balanced operation under varying loads72,73. The integration of smart technologies and advanced control strategies is essential for achieving reliable, efficient, and sustainable hybrid energy systems70.

Recent studies highlight the use of hybrid optimization models, integrating machine learning and decomposition techniques to address the complexities of modern energy systems. For example, a two-phase decomposition model combining complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition and bidirectional long short-term memory has improved load forecasting accuracy74. Similarly, multi-model fusion methods utilizing advanced algorithms like particle swarm optimization-support vector machines and autoencoders have proven effective for forecasting load components in smart grid systems75. In the realm of smart grids, deep learning models, particularly those combining graph convolutional networks and sequence-to-sequence models with attention mechanisms, have shown significant improvements in load type prediction, enhancing energy management and optimization76. These advancements have facilitated demand response initiatives and improved energy efficiency through precise load predictions and real-time energy management.

In commercial microgrids, advanced EMS approaches combine fuzzy logic and intelligent energy controllers to dynamically manage DERs and consumer loads. These systems, tested in MATLAB/Simulink, showcase improved techno-economic feasibility by reducing peak loads and electricity costs by up to 11.87% daily and 7.94% over 20 years, ensuring sustainable energy management77. Advanced DSM strategies have achieved substantial economic and environmental benefits. For instance, deep learning-based energy management systems have reduced grid reliance by 84% and energy expenses by 87% through accurate energy forecasting78. Similarly, community renewable energy networks employing shared PV and storage systems have achieved savings of up to 95.5% compared to traditional energy setups79. Additionally, the adoption of DSM in industrial and residential settings has facilitated cost reductions through improved load distribution, better tariff selection, and energy resource optimization80,81. These efforts contribute significantly to reducing carbon footprints and aligning energy practices with sustainability goals.

Hybrid EMS solutions are essential for handling the intermittency of renewable energy and dynamic grid demands. For instance, the integration of solar PV with battery storage systems in grid-tied microgrids benefits from real-time predictive algorithms, such as XGBoost for solar PV forecasting, achieving root mean square error (RMSE) below 4%. These frameworks optimize battery charging and discharging operations, reducing electricity bills by 20% for energy-intensive systems like sewage treatment plants82. Furthermore, an optimization method tailored for hourly electricity prices considers a cluster of interconnected price-responsive demands, including an energy storage facility. By leveraging LP and ANN-based future power consumption predictions, this EMS enables consumers to buy, store, and sell energy effectively, optimizing hourly load levels. Simulations using the IEEE 14-bus system reveal superior performance in enhancing efficiency and reducing losses compared to conventional methods83.

Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) has been effectively utilized in various hybrid energy systems, including those combining photovoltaic and wind sources, to dynamically adjust power outputs and enhance grid stability84. The incorporation of ANFIS in controlling voltage source converters further illustrates its capability in managing energy from multiple sources, ensuring quality power delivery and load balancing85. The study of86 proposes an ANFIS to optimize energy flow in grid-linked solar and battery storage systems, ensuring optimal operation, increased efficiency, and cost savings by dynamically adjusting energy distribution based on solar irradiance, demand patterns, and grid prices. The Smart Home Energy Management System using Multi-output ANFIS for efficient management of ESS, scheduled appliances and to integrate Renewable energy is introduced87. Additionally, The paper of88 describes and evaluates an ANFIS-based EMS of a grid-connected hybrid system and compares with a classical EMS composed of state-based supervisory control system based on states and inverter control system based on PI controllers.

Similarly, ANFIS has demonstrated its utility in managing energy in hybrid RES, such as PV/Wind/Battery setups. By mitigating power fluctuations and maintaining battery SOC within acceptable limits, ANFIS improves system reliability and extends battery lifespan. Simulations confirm that this strategy significantly reduces power injection fluctuations into the grid, a critical issue in renewable energy systems89. Other hybrid solutions leverage probabilistic and deterministic forecasting for wind energy conversion systems and battery storage. A predictive energy management control and communication system (PEMCCS) minimizes renewable energy curtailment while ensuring smooth power injection into the grid. By dynamically adjusting to forecast errors, PEMCCS increases the revenue of renewable energy systems and enhances grid reliability90.

Hybridizing ANFIS with other optimization methods, such as metaheuristics and machine learning techniques, can achieve effective parameters tunning to enhance its exploration and exploitation capabilities for better solution quality and robust optimal performance91. These research gaps in the literature reveal the necessity to advance further ANFIS variant methods that can effectively adapt the optimization process parameters in highly dynamic hybrid energy systems environment. For example, ANFIS is optimized with Balancing Composite Motion Optimization to enhances energy management by responding to price-based demand response programs, thereby improving user comfort and reducing electricity costs92.

Additionally, in our order study in65, we design and evaluation of a hybrid GEP-ANFIS controller for optimizing energy management and load control in industrial settings can significantly enhance operational efficiency and reduce costs. The controller allows for improved predictive accuracy in energy management, as demonstrated in grid-connected solar PV-battery systems, where the hybrid model achieved a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 7.25% and reduced energy costs by 6.7%65. However, the long-term economic analysis of hybrid predictive energy management models remains underexplored, despite the potential benefits highlighted in recent studies as shown in Table 1.

The integration of technical optimization with long-term financial analysis offers a comprehensive solution for industrial users, addressing both operational efficiency and financial viability. Research highlights the importance of optimizing investment planning through process integration methods, which can significantly enhance energy efficiency and reduce costs, achieving up to a 27% improvement in operating costs without budget constraints98. Additionally, the development of a techno-economic analysis tool facilitates the assessment of long-term viability for emerging processes, such as biorefining, by incorporating various supply chain models and future uncertainties99. Collectively, these studies of100,101,102,103,104 highlight the necessity for more extensive long-term economic evaluations in hybrid energy management models.

Recent years have witnessed an accelerating integration of deep-learning and hybrid-AI techniques into PV–battery and energy–storage management systems. For example105, introduced a transformer-based fusion model for day-ahead PV generation forecasting that combines physical modelling with AI106. applied a transfer-learning double-deep Q-network in a wind–PV–storage context to balance active power, achieving improved adaptability under uncertainty. More recently107, demonstrated a deep-reinforcement learning (DRL) method for PV–battery storage scheduling, realizing significant reductions in imbalance penalties. A broader review by108 highlights how AI/ML controllers for EMSs are evolving towards hybrid architectures combining predictive analytics, reinforcement control and storage optimisation. Despite these advances, few studies explicitly combine symbolic evolutionary rule-learning (via GEP) with neuro-fuzzy inference systems in the context of PV–battery energy management, and even fewer integrate full techno-economic modelling and structural optimisation of fuzzy controllers.

Despite the rapid evolution of energy management systems (EMS), existing approaches exhibit key limitations. Most ANFIS- or fuzzy-based controllers rely on static rule sets and lack adaptive capability when exposed to fluctuating renewable inputs and dynamic industrial loads65. Similarly, optimization techniques such as genetic algorithms or particle swarm optimization improve EMS performance but often at the cost of computational efficiency and real-time adaptability. Moreover, while hybrid EMS models incorporating artificial intelligence have shown promising results, their integration rarely extends to evolving fuzzy membership rules and long-term techno-economic optimization in industrial microgrid contexts. Therefore, there exists a crucial research gap in developing a self-adaptive EMS framework that can jointly optimize forecasting accuracy, economic performance, and system longevity under grid constraints. This study addresses this gap by proposing a hybrid Gene Expression Programming–Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (GEP–ANFIS) capable of evolving fuzzy inference rules and optimizing control parameters dynamically, thus bridging the divide between predictive intelligence and techno-economic sustainability in industrial hybrid renewable–grid systems. A comparative techno-economic analysis of daily energy consumption was performed against the HOMER optimization model, demonstrating the proposed EMS’s superior effectiveness in demand response applications.

The novelty of this work lies in the integration of Gene Expression Programming (GEP) with Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) for the first time within a techno-economically optimized EMS designed for industrial hybrid renewable–grid systems. Unlike previous EMS models that either focus on energy scheduling or predictive control in isolation, this study presents a unified predictive–economic optimization framework that evolves its fuzzy rules and membership functions adaptively through GEP. Furthermore, the model’s long-term cost evaluation establishes new insights into lifecycle savings and operational reliability for grid-constrained industries.

Quantitatively, the proposed GEP–ANFIS framework achieved a Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 5.31% for solar PV forecasting and 2.24% for industrial load prediction, reducing long-term operational costs by 37.7% compared to HOMER-based EMS and by 6.5% compared to conventional ANFIS models.

The main contributions are summarized as follows:

-

Novel predictive optimization model: Development of a hybrid GEP–ANFIS framework that simultaneously evolves fuzzy rules and tunes control parameters to improve forecasting accuracy for solar PV and load demand prediction.

-

Integrated technical–economic optimization: Incorporation of both operational and long-term economic analyses within the same EMS platform a dimension largely unexplored in prior studies.

-

Hierarchical multi-level control architecture: Implementation of a decentralized–centralized structure for optimal coordination between PV, battery, and grid systems, enhancing scalability and resilience.

-

Demonstrated superiority through comparative metrics: Achieved up to 37.7% long-term cost reduction over HOMER and 6.5% over conventional ANFIS, validating its predictive and economic advantages.

-

Strategic contribution to industrial sustainability: Introduced a data-driven, adaptive EMS that extends battery lifespan, minimizes grid dependence, and provides a replicable model for industrial energy-intensive applications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents the overall system architecture and modeling, including the conventional grid system, solar PV modeling, and battery storage system. Section 3 describes the proposed energy management control strategy, while Sect. 4 introduces the proposed GEP-ANFIS hybrid model. This includes the hybrid GEP-ANFIS-based MPPT, hybrid GEP-ANFIS-based load and solar PV forecasting, and the hybrid GEP-ANFIS-based EMS. Section 5 provides a comprehensive discussion of the simulation results, which cover: the optimized ANFIS-based MPPT results, predictive analytics for load and solar PV forecasting, predictive generation scheduling scenarios, and the optimized sizing of the solar PV and battery storage systems tailored for industrial applications. This section also includes a detailed sensitivity analysis, along with both daily and long-term economic evaluations. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes the study and offers recommendations and directions for future research.

System architecture

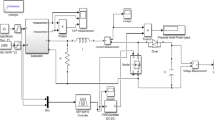

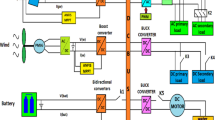

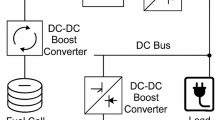

The architecture of the proposed grid-connected solar PV and battery energy storage system utilizes a hierarchical control structure to optimize energy flow and ensure reliability. The system comprises decentralized controllers for solar PV and battery management, along with a centralized Energy Management Controller (EMC) as shown in Fig. 1. The solar PV array serves as the primary energy source, interfaced via a DC-DC converter equipped with MPPT to maximize power extraction. A bi-directional DC-DC converter manages the battery storage system, regulating charge/discharge cycles. A DC-AC inverter ensures seamless conversion of DC power to AC, synchronized with grid parameters for both local loads and grid export/import. The EMC integrates a predictive GEP-ANFIS control algorithm, which monitors solar output, battery SOC, and grid conditions to optimize energy dispatch. This advanced architecture enhances system efficiency and cost-effectiveness while leveraging renewable resources to mitigate intermittency through intelligent storage and control strategies.

Site description and meteorological data

Global Tea Company, a leading player in Uganda’s tea industry, is strategically located along Ishaka-Kasese Road in the Bushenyi district at latitude −0.264164 and longitude 30.106706. This location offers an ideal environment for production and logistics, enabling the company to maintain its position as one of the largest producers and consumers of tea and energy in Uganda. The company boasts advanced infrastructure, including tea and grains color sorters, fermenting and drying machines, boilers, rolling and packaging equipment, and monorail systems, ensuring efficient and high-quality tea processing operations.

However, energy usage represents a significant operational cost, accounting for over 50% of production expenses, making the company one of the most energy-intensive enterprises in the country109. Traditionally, Global Tea Company relies on a three-phase grid system supplemented by diesel generators to address grid intermittency. This reliance incurs high costs associated with fuel and generator maintenance, creating financial and operational inefficiencies. To mitigate these challenges, the company is transitioning to renewable DG, incorporating solar PV systems as a cost-effective and sustainable solution. With an average solar irradiation of 5.7 kWh/m2/day and a temperature of 26.97 °C110, solar energy presents a viable option for reducing energy costs and enhancing energy reliability.

This study leverages load data from UMEME’s regional office in Ishaka and meteorological data from NASA, spanning 2016 to 2023 (see Fig. 2 for the average hourly data), to analyze energy demand patterns and forecast renewable energy integration. Research findings, supported by studies by111,112, suggest that solar PV’s levelized cost of energy (LCOE) can be more economical than grid electricity during peak periods, particularly for industrial users. By adopting solar PV systems, Global Tea Company aims to lower operational costs, improve energy reliability, and promote sustainability, setting an example for renewable energy adoption in Uganda’s industrial sector.

System modeling

By creating accurate models for each component and their interactions, the overall grid-connected solar PV system’s behavior, performance, and impact on the grid can be simulated, analyzed, and optimized for efficient and reliable energy generation. These models assist in designing, predicting, and assessing the system’s behavior under various operating conditions, as well as making informed decisions for system optimization and integration with the grid65. The system model components and parameter (refer to Table 2) are explained briefly below:

Conventional grid system

A comprehensive three-phase grid-connected system is modeled in Simulink to replicate actual grid conditions, starting with a programmable voltage source configured at 240 Vrms and 60 Hz. The system integrates a three-phase V-I Measurement block to monitor real-time voltage and current variations, enabling precise tracking of grid performance under varying loads. A Series RLC Load block is included to simulate realistic power consumption, while a power measurement block computes instantaneous power, facilitating accurate evaluation of system efficiency. Display blocks are employed to visualize voltage, current, and power readings during the simulation, providing real-time feedback for diagnosing issues and ensuring optimal operation. The grid is configured to automatically supply power when solar and battery outputs are insufficient, ensuring system stability and continuous power delivery. This robust modeling approach supports seamless integration of renewable energy sources while maintaining grid reliability. The energy supplied by the grid is mathematically expressed as94:

The energy cost for grid customers is calculated by integrating the time-of-use \(\left( {ToU} \right)\) rate into the mathematical framework, as shown in Eq. (1)65. This approach effectively captures the dynamic variability of electricity pricing, enabling accurate cost estimation based on hourly consumption patterns. The formulation is expressed as:

where \(P_{grid,t}\) represents the power supplied by the grid at time \(\left( t \right)\), \(\Delta t\) denotes the time interval and \(T\) is the total number of time intervals considered (i.e.24 h).

The \(\left( {ToU} \right)\) tariff for large industrial users employed in this study is derived from recent data sources115,116 and is detailed in Table 3. The tiered structure comprises peak, shoulder peak, and off-peak periods, each associated with distinct rates designed to reflect the variability in energy demand and supply dynamics.

Solar PV modeling

In this study, the solar PV system, serving as the primary source of energy, is modeled in the Simulink environment using a double-diode equivalent circuit constructed with Simscape Electrical components. Although both single- and double-diode models are widely used to represent PV cell characteristics, the double-diode model is selected in this study to capture the nonlinear recombination and diffusion losses that significantly influence industrial PV performance under variable irradiance and temperature conditions. The single-diode model assumes that all carrier losses occur via a single exponential process, which simplifies computation but introduces notable inaccuracies at low irradiance or partial shading scenarios where recombination currents dominate. The double-diode model introduces an additional exponential term that explicitly accounts for junction recombination effects, enabling a more accurate estimation of output current and voltage relationships across the entire operating range. This higher fidelity is particularly beneficial for GEP–ANFIS-based predictive optimization, where accurate PV response modeling directly affects controller training and long-term cost predictions65,117.

The model incorporates resistors, capacitors, two diodes, and a controlled current source to accurately represent the electrical characteristics of PV cells, with inputs for irradiance and temperature to simulate real-world environmental variations. Voltage and current sensors, along with a product block, are integrated to measure and calculate instantaneous power. The DC-DC converter, comprising an inductor, capacitor, diode, and MOSFET, is controlled by a PWM generator to regulate the duty cycle. Simulation parameters in65, are carefully configured to ensure realistic and efficient performance analysis. The generated power is expressed as:

where \(V_{PV} {\text{ and }}I\) represent the voltage and current at the maximum power point. In the double-diode model, the output current is modeled as118:

The output current is given by the following expression as:

where: \(I_{Ph}\) is Photocurrent; \(I_{D1}\) and \(I_{D2}\) is the Shockley diode equation due to diffusion and charge recombination mechanism respectively; I is the output current of the PV cell; \(I_{01}\), \(I_{02}\) are the reverse saturated current of the diodes \(D_{1}\) and \(D_{2}\) respectively; q is the electron charge, K is the Boltzmann constant, \(T,T_{s}\) = Temperature at normal condition and S.T.P respectively; \(G{,}G_{s}\) = Solar irradiation at normal condition and S.T.P respectively; \(a_{1}\) and \(a_{2}\) are ideality factor of the diodes \(D_{1}\) and \(D_{2}\) respectively for the two diode model, V is the thermal voltage of the module, \(R_{S}\) and \(R_{Sh}\) is series and shunt resistors respectively65.

Battery storage system

To ensure realistic system representation, all significant nonlinearities inherent in the hybrid solar PV–battery–grid system were explicitly modeled. The double-diode PV model captures both diffusion and recombination current effects, ensuring accurate representation of nonlinear current–voltage (I–V) and power–voltage (P–V) characteristics under variable irradiation and temperature. Similarly, the battery energy storage system incorporates nonlinear charge–discharge efficiency, internal resistance variation, and state-of-charge (SOC) dynamics, which influence voltage response and depth-of-discharge behavior. The inverter and converter subsystems were also modeled to reflect nonlinear switching and control behaviors within the Simulink environment. Collectively, these nonlinearities ensure that the simulated environment mirrors real operating conditions, providing a reliable basis for developing and validating the GEP–ANFIS controller.

In this study, a battery charging and discharging system is modeled in Simulink using a comprehensive setup in65 to ensure accurate performance analysis and optimization, as defined in Eqs. (6–7)119:

The battery capacity (\({C}_{b})\) is represented as94:

The expression for the battery’s SOC is given by120,121:

The battery current is given as120:

The constraints are given in Eq. 11 and 12 respectively

where: \(\varphi\) = autonomy days, DoD = depth of discharge (%), \(l_{b}\) = battery loss (%), \(V_{b}\) = battery voltage (V), \(\eta^{inv}\) = inverter efficiency (%), and \(\eta^{B}\) = battery efficiency (%).

These constraints were embedded into the simulation control structure, where the GEP–ANFIS controller continuously monitors the SOC, charging/discharging limits, and inverter efficiency. Violation of these limits automatically triggers corrective actions through rule-based logic, ensuring that all operating points remain within safe physical boundaries. This dynamic constraint handling is fundamental for extending battery life and ensuring long-term system stability.

Proposed energy management control strategy

The flowchart in Fig. 3 illustrates the decision-making logic of a demand-side energy management controller for a grid-connected solar PV system with battery storage. Initially, weather data and system parameters for the PV array, battery SOC, and load demand are input into the model. The controller calculates the solar power generated (\(P_{s}\)), the load demand \((P_{L} )\), and the battery’s SOC at each time step (t). If the solar power meets or exceeds the load demand \((P_{S} \ge P_{L}\)), the system supplies power directly to the load. Under conditions of excess generation, the controller checks the battery’s SOC: if the SOC is below the minimum threshold, the battery is charged; otherwise, surplus energy is exported to the grid.

When solar generation is insufficient to meet the load \((P_{S} \prec P_{L} )\), the controller evaluates other power sources. If the battery’s SOC is above the minimum threshold, the system draws power from the battery. If not, the system determines grid availability; if the grid is accessible, power is purchased to satisfy the demand. This hierarchical control structure ensures optimal utilization of solar power, battery storage, and grid resources, minimizing costs and reducing peak demand charges. The process iterates until the end of the simulation period \((T_{Max} )\), ensuring a dynamic response to fluctuations in solar power and load demand, thereby enhancing reliability and resilience in industrial applications. These methodologies aim to maximize the utilization of available energy sources, minimize wastage, and ensure optimal source operation, thereby improving overall system efficiency via the EMC.

Proposed GEP-ANFIS hybrid model

GEP-ANFIS is selected for this study due to its ability to combine the adaptability and optimization capabilities of genetic algorithms with the uncertainty-handling strengths of fuzzy logic, making it ideal for optimizing complex energy systems. The model is particularly suited for addressing non-linearities in energy data, adapting to varying scenarios, and optimizing intricate systems. Key components of the GEP-ANFIS framework include genetic algorithms for optimizing control strategies, fuzzy inference systems for uncertainty management, and adaptive learning mechanisms that enhance accuracy over time.

While heuristic-based optimization methods such as GEP, GA, PSO have demonstrated strong global search capabilities and flexibility for nonlinear controller tuning, they typically require access to high-fidelity simulation environments or extensive experimental datasets to achieve convergence and generalizability122,123. This requirement can pose limitations in large-scale or highly dynamic industrial systems, where obtaining such datasets or building full digital twins is resource-intensive. To mitigate this, the present study uses a hybrid simulation data-driven strategy that leverages historical load and meteorological data to train and evolve the GEP–ANFIS controller within a realistic Simulink-based digital environment. This approach minimizes the need for exhaustive experimentation while maintaining the model’s adaptability to real operating conditions.

The hybridization of GEP-ANFIS presented in this study represents a substantive methodological innovation beyond existing ANFIS–metaheuristic combinations such as ANFIS–PSO, ANFIS–GA, or ANFIS–XGBoost. Traditional metaheuristic-based ANFIS frameworks primarily focus on parameter tuning through stochastic or gradient-based search, where rule structures and membership functions are fixed and only optimized numerically. In contrast, the proposed GEP–ANFIS framework performs structural as well as parametric optimization, meaning that GEP evolves both the fuzzy rule base and membership functions’ topology before ANFIS fine-tunes their parameters through hybrid learning. This dual-layer adaptation provides deeper exploration of the solution space and greater adaptability under nonlinear, dynamic energy environments.

Algorithmically, GEP contributes symbolic regression capability, enabling the discovery of interpretable functional relationships between energy variables. This feature is not available in PSO, GA, or XGBoost hybrids, which typically rely on black-box optimization. Moreover, GEP’s chromosome-based encoding allows compact representation of rule evolution, reducing computational overhead and avoiding premature convergence issues common in population-based metaheuristics. When coupled with ANFIS’s gradient-based local learning, the hybrid ensures both global exploration (via GEP) and local exploitation (via ANFIS), achieving faster convergence, lower forecast error, and better generalization. To further highlight the methodological advancement of the proposed hybrid GEP–ANFIS model, a comparative summary of existing hybrid ANFIS approaches is presented in Table 4.

Moreover, recent research suggests that simplified optimization methods including zero-order or derivative-free techniques such as Nelder–Mead simplex, pattern search, and response surface-based tuning can serve as computationally efficient alternatives for small-scale implementations or initial parameter estimation127. Integrating these low-complexity optimizers with the proposed hybrid framework represents a promising direction for future work, potentially reducing calibration costs while preserving controller robustness.

The proposed GEP–ANFIS framework inherently accommodates system nonlinearities by mapping complex relationships among irradiance, temperature, load demand, and state-of-charge through adaptive fuzzy inference rules. Unlike linear optimization or deterministic EMSs, the hybrid model continuously learns nonlinear interactions between energy sources and demand-side responses, ensuring accurate control decisions even under fluctuating environmental and operational conditions. The GEP-ANFIS framework is implemented as a hierarchical control system to monitor and manage solar power generation, battery charge and discharge cycles, and predictive EMS, including load and solar PV generation forecasting in different levels. This approach effectively minimizes, controls, and optimizes energy usage, providing robust and reliable performance in real-time applications. The pseudocode for the GEP-ANFIS algorithm is detailed in Table 6, with further explanation on each levels are provided in subsequent subsections.

A thorough examination of the collected data is conducted to identify and rectify any missing values and anomalies. The data is normalized to standardize the range of input variables, facilitating better performance of the ANFIS model. The dataset is divided into three subsets: training (80%), validation (10%), and testing (10%). This partitioning ensures a robust training process and reliable performance evaluation. An ANFIS model with N inputs and one output can be expressed in terms of its rule base, where each rule defines a fuzzy relationship between inputs and outputs. In this study, the inputs. Which are typically crisp values are donated as:

where \(\left[ {x_{1} ,x_{2} ,x_{3} ,..........x_{n} } \right]\) is the input vector of system parameters such as solar irradiance (W/m2), ambient temperature (°C), load demand (kW), and battery state-of-charge (SOC, %). Each input has its own fuzzy set and associated membership function, \(\mu A_{i,j} \left( {x_{i} } \right)\), where \(i\) is the input index, and \(j\) represents the fuzzy set for that input. The membership functions are model using a Gaussian form as:

where the membership function for the \(j^{th}\) fuzzy set of input variable \(x_{i}\), dimensionless, defined by a Gaussian function in Eq. (14), \(c_{i,j}\) and \(\sigma_{i,j}\) are the center and width of the membership function for fuzzy set \(j\) of input \(i\).

This study employs a hybrid algorithm combining the backpropagation and least mean squares methods to train the dataset, leveraging the complementary strengths of both techniques. The backpropagation algorithm fine-tunes the antecedent parameters, while the least mean squares algorithm optimizes the consequent parameters, collectively minimizing prediction errors and significantly enhancing model accuracy. A fuzzy rule base is established to capture the complex relationships between inputs and outputs, with each rule reflecting a specific interaction among inputs and predicting the corresponding output under defined conditions. The rules are typically expressed as if–then statements, which show the influence of each input on the system’s behavior, as illustrated below

where \(f_{k,l,m,n,p}\) is the consequent function for that rule, and \(a,b,c,d,e,r\) are the parameters of the consequent function. The output \(y\) of the ANFIS model is calculated by aggregating the outputs of all rules as:

where \(y\) is the Output vector representing the model prediction (e.g., load demand or PV output, in kW). The firing strength \(w_{k,l,m.,n,p}\) is given by:

where the firing strength of the \(k^{th}\) fuzzy rule (dimensionless), computed as the product of all antecedent membership grades [Eq. (17)].

During the design and implementation of the proposed GEP–ANFIS energy management model, all operational and physical constraints of the hybrid system were explicitly integrated into the optimization process to ensure feasible and realistic operation. The key system constraints include:

Battery operational constraints

The state of charge of the battery is limited within the permissible range \(\left[ {SOC_{\min } ,SOC_{\max } } \right]\) to prevent overcharging or deep discharging, as defined in Eqs. (11–12). During each optimization iteration, the GEP–ANFIS controller checks SOC boundaries, and infeasible solutions [\(SOC_{Min} \le SOC_{(n)} \le SOC_{Max}\)] are penalized through a high-cost term added to the fitness function.

Power balance constraint

At every time step (t), the total generated power (from PV, grid, and battery) must equal the instantaneous load demand plus losses, expressed as:

Any deviation from this balance is minimized within the GEP optimization loop by adjusting fuzzy control rules and weighting parameters.

Grid interaction and time-of-use tariff constraint

Power import/export decisions respect the tariff schedule in Table 3, ensuring that grid draw is prioritized during off-peak periods and limited during high-cost intervals. These constraints are embedded as time-dependent boundary conditions in the controller’s decision logic.

PV generation and environmental constraints

Solar output is constrained by real irradiance and temperature data, modeled through the double-diode equation (Eq. 5). The GEP–ANFIS model dynamically adapts to these nonlinear limits to ensure that generated power never exceeds physical PV capacity.

Controller parameter initialization

The ANFIS component was initialized with five Gaussian membership functions per input variable (irradiance, temperature, time, load, and SOC), resulting in 125 fuzzy rules. The learning rate and hybrid training method parameters were set according to initial sensitivity analysis to balance convergence speed and generalization. Initial premise parameters (membership function centers and widths) were uniformly distributed between 0 and 1, while consequent parameters were initialized based on least-squares estimation of training data outputs.

The GEP optimizer encoded these parameters as chromosomes representing both the structure (rule base) and tuning coefficients of the ANFIS model. The chromosome length was set to 60 genes, with each gene representing a numerical or structural decision variable in the fuzzy inference system.

Optimization objective function

GEP is used here to optimize the structure and parameters of the ANFIS model by evolving both the fuzzy rules and membership function parameters, improving the ANFIS’s adaptability and predictive accuracy. This optimization process is designed to minimize a costs associated with grid energy by prioritizing solar generation when available, and by optimizing grid interactions to take advantage of low-cost periods or minimize reliance on the grid when it’s more expensive. The objective function (F) for the effectiveness of the energy management is defined as:

where:\(w_{1} ,w_{2} ,w_{3}\) are weights that reflect the relative importance of each objective.

Optimization algorithm and parameters

The GEP optimizer is employed due to its strong global search capability and ability to evolve both rule structures and parameter sets. The optimization parameters were configured as shown in Table 5: The optimization is terminated when any of the following conditions are satisfied:

-

1.

The best fitness improvement over 20 consecutive generations is less than 10–5.

-

2.

The maximum generation limit (500) is reached.

-

3.

Validation set performance degraded by more than 1% compared to the training set (to prevent overfitting).

Each chromosome represents a potential solution and encodes the membership function parameters and as well as the consequent parameters. The fitness function is designed to minimize prediction error. For a control system output \(y\) based on actual values the fitness is:

where \(M\) is the number of data samples.

Selection is the process of choosing chromosomes from the population to create offspring. Higher fitness chromosomes are more likely to be selected. One common selection method is roulette wheel selection, where the probability of selecting chromosome \(C_{i}\) is proportional to its fitness (Balikowa130).

Crossover combines two parent chromosomes to create offspring. A common method is single-point crossover, where a crossover point \(k\) is randomly selected, and the two parents exchange parts of their chromosomes at that point. For parents (Balikowa130):

The offspring would be:

Mutation introduces small random changes to the genes in a chromosome, helping to maintain genetic diversity and avoid local optima. For a gene \(x_{i}\) in chromosome \(C\), mutation might add a small random value δ (Balikowa130):

where δ is a normally distributed random variable with mean 0 and standard deviation σ.

Through selection, mutation, and crossover, GEP iteratively evolves the population to find the optimal parameters, minimizing the fitness function. This improved functions provide a better mapping between the fuzzy inputs and outputs, ensuring that the system responds more accurately to variations in inputs and output. The optimized output \(y_{opt}\) after GEP tuning can be written as:

where \(w_{k,l,m.,n,p}^{opt}\) and \(f_{k,l,m.,n,p}^{opt}\) are the optimized firing strengths and consequent functions determined by GEP. This model provides an adaptive, precise control strategy for the hybrid energy management system, optimizing battery usage and grid interactions based on real-time conditions from the all inputs (Table 6).

Hybrid GEP-ANFIS based MPPT

The initial step in designing a GEP-ANFIS-based MPPT controller involves begins with data collection, focusing on hourly temperature and solar irradiation specific to the case study’s geographical location. Irradiation data from 9 PM to 6 AM, which provides negligible power, was excluded from the analysis. The screened dataset is used in the MATLAB/Simulink PV model to generate outputs, forming the training dataset for the ANFIS. The GEP-ANFIS-based controller was integrated into the solar energy system to optimize performance under varying environmental conditions. This controller dynamically adjusts the duty cycle of a DC-DC converter to ensure the PV system operates at maximum efficiency. The integration process involved simulating the PV system in MATLAB/Simulink, leveraging real-time sensor feedback to maintain optimal power output and system efficiency. The performance of the hybrid model is rigorously evaluated using efficiency equation given below:

where \(P_{mppt}\) = the maximum output power that can be extracted from a PV system when employing an MPPT controller. On the other hand, \(P_{pv}\) = the real power produced by the solar PV system without the use of an MPPT controller.

Hybrid GEP-ANFIS Based load and solar PV forecasting

Accurate forecasting of industrial load demand profiles is essential for efficient energy system operation, particularly given the increasing complexity of consumption patterns. Similarly, precise predictions of solar PV output are critical to achieving operational and sustainability goals. However, uncertainties such as inaccuracies in weather forecasting can significantly impact optimization processes and disrupt optimal energy scheduling65,131,132. In this study, historical data on load, time, temperature, and solar irradiation are analyzed to forecast both load demand and solar PV power generation, supporting long-term and short-term energy planning. The analysis identifies trends, seasonal variations, and growth patterns in energy consumption, which are instrumental for optimizing supply strategies and ensuring energy system reliability.

The performance of the predictive models is evaluated using metrics such as RMSE, Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD), and MAPE, as outlined in Eqs. (29) – (31). These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment framework, capturing different dimensions of prediction accuracy across diverse operational scenarios133. By addressing the challenges of forecasting with advanced modeling techniques, this study contributes to enhancing energy management strategies, emphasizing the role of precise predictions in optimizing industrial energy consumption and effectively integrating RESs.

Hybrid GEP-ANFIS Based energy management system

This study proposes a hierarchical controller designed to optimize energy production and consumption in grid-connected PV-battery systems. The system efficiently manages energy flow between the grid, solar PV arrays, and battery storage while considering dynamic load demands. This strategy ensures efficient energy utilization, significantly reducing peak demand charges and operational costs in industrial settings. The hybrid GEP-ANFIS model enhances energy management by balancing supply and demand, integrating renewable energy sources, and employing real-time adaptive control to minimize operational expenses.

The proposed GEP-ANFIS model leverages grid data, time of day, battery status, forecasted load, and solar PV data as inputs to optimize system performance. By combining the adaptability of GEP with the uncertainty-handling capability of ANFIS, the model delivers exceptional efficiency and precision. Performance metrics such as peak demand and cost reduction are used to evaluate the predictive capabilities of the model. Additionally, HOMER software serves as a baseline for long-term planning, providing a benchmark to justify the viability and superiority of the developed hybrid model. This approach represents a significant advancement in energy management for industrial-scale applications.

Simulation results and discussion

Optimized ANFIS based MPPT results

The results of the optimized ANFIS-based MPPT model reveal its superior performance across three distinct scenarios: varying solar irradiation and temperature, varying solar irradiation with constant temperature, and constant solar irradiation with varying temperature. In the first scenario, the GEP-ANFIS double-diode model outperformed all other configurations, generating 250.1567512 kW of daily power, which is 41.1% higher than conventional MPPT methods as illustrated in Fig. 4. This consistent improvement highlights the model’s ability to accurately track the maximum power point under fluctuating environmental conditions, leveraging the enhanced complexity and precision of the double-diode configuration.

In the second scenario, under constant solar irradiation (1000 W/m2) and varying temperatures, the GEP-ANFIS double-diode model maintained the highest efficiency, achieving 99.84% at 15 °C with an output power of 249.6 W and 94.72% at 55 °C with an output power of 236.8 kW, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. Similarly, in the third scenario, with constant temperature (25 °C) and varying solar irradiation, the GEP-ANFIS double-diode model consistently achieved the highest efficiency, ranging from 48.38% with an output power of 151.91 kW at 200 W/m2 to 97% with an output power of 242.5 kW at 1000 W/m2 as illustrated in Fig. 5b. It is important to note that the dynamic performance of the proposed GEP–ANFIS MPPT under fluctuating irradiance and was comprehensively validated in our earlier study129, conducted according to the EN 50,530 test standard. Hence, the present work focuses on system-level techno-economic integration rather than re-evaluating MPPT dynamics. These results underscore the hybrid model’s exceptional adaptability to changing environmental conditions, maximizing energy capture and consistently surpassing the efficiency and output power of its ANFIS counterparts. The findings conclusively demonstrate the GEP-ANFIS double-diode model’s significant advantages in efficiency and reliability, making it a robust solution for optimizing renewable energy systems.

Predictive Analytics for Load and Solar PV Forecasting

The comparative analysis of forecasting models for both solar PV output and load demand in Table 7 reveals a consistent superiority of the hybrid GEP-ANFIS framework over standalone GEP and ANFIS models. In the context of solar PV forecasting, GEP-ANFIS2 achieved the lowest short-term error metrics, with a MAD of 2.91%, MAPE of 5.31%, and RMSE of 8.41%, significantly reducing prediction errors compared to GEP1 (MAD = 16.06%, MAPE = 24.62%, RMSE = 19.63%) and ANFIS1 (MAD = 15.25%, MAPE = 12.11%, RMSE = 19.63%). Long-term forecasting performance remained consistent, where GEP-ANFIS2 achieved a MAD of 5.82%, MAPE of 7.566%, and RMSE of 15.138%, showcasing its robustness over extended horizons. These improvements emphasize the model’s superior capacity to adapt to the nonlinearity and intermittency of solar irradiance data, particularly under region-specific climatic variability.

In load demand forecasting, the advantage of the hybrid model is even more prominent. GEP-ANFIS achieved a short-term MAD of 0.13%, MAPE of 2.24%, and RMSE of 0.18%, indicating high precision in capturing short-duration load fluctuations. For long-term projections, the model sustained performance with MAD of 0.156%, MAPE of 3.472%, and RMSE of 0.2196%, substantially outperforming GEP (MAD = 3.165, MAPE = 6.045%) and ANFIS (MAD = 2.912%, MAPE = 5.921%). This demonstrates the model’s effectiveness in learning temporal dependencies in electrical consumption trends, critical for planning and stability of power systems. The substantial reductions in MAD, MAPE, and RMSE across both short- and long-term scenarios validate the hybrid model’s utility in developing predictive analytics frameworks for intelligent grid management, especially in environments characterized by high variability and data nonlinearity.

Predictive cases of scheduling generation

Case one: grid only

The comparative evaluation of predictive energy scheduling using GEP-ANFIS and conventional ANFIS models, under the operational constraint of serving industrial loads exclusively from the grid, demonstrates a high degree of alignment across most time intervals as shown in Fig. 6. From 1:00 to 16:00, the predicted energy consumption values between the two models exhibit minimal variance generally within ± 0.1 kWh indicating that both systems maintain high accuracy in modeling energy demands during stable or baseline operational periods. This narrow deviation underscores the robustness of both models in forecasting under deterministic or low-volatility industrial load conditions. Notably, time steps such as 1:00–16:00 reveal identical outputs, suggesting convergence in predictive logic under steady-state loads.

However, post-Time 16, a significant divergence in prediction emerges, particularly between 17:00 to 24:00, where GEP-ANFIS consistently predicts lower energy consumption compared to standard ANFIS. For instance, at 17:00, GEP-ANFIS forecasts 43 kWh, whereas ANFIS estimates 67.39 kWh a discrepancy of over 24 kWh, or approximately 35.6% lower. This pattern is recurrent in all subsequent time steps, indicating that GEP-ANFIS has superior adaptability in identifying latent load reductions or off-peak operational efficiencies due to its enhanced learning capability derived from the genetic algorithm’s optimization layer. Such improved accuracy during off-peak hours, when industrial load dynamics are highly nonlinear or influenced by ancillary systems, reinforces the suitability of GEP-ANFIS for energy-efficient, intelligent scheduling in grid-constrained industrial environments. This finding supports its application in real-time demand-side management, where predictive precision is crucial for optimizing operational costs and grid stability.

Case two: Solar PV and battery only

The predictive scheduling results, under the operational constraint of using solar PV and battery storage exclusively to serve industrial loads, indicate a significant performance advantage of the GEP-ANFIS hybrid model over the conventional ANFIS controller as shown in Fig. 7. During the early 1:00–8:00, when solar input is negligible or minimal, both models rely entirely on battery discharge to meet industrial load demands. However, GEP-ANFIS consistently maintains higher SOC margins preserving an average of 6–10% more SOC than ANFIS thereby avoiding deep discharge conditions which typically accelerate battery degradation. Notably, at 4:00, ANFIS approaches its critical SOC threshold of 27% while GEP-ANFIS sustains a safer margin at 30%, successfully meeting the full load without shedding. This reflects the GEP optimizer’s ability to fine-tune fuzzy rules, favoring long-term SOC stability over aggressive discharge strategies.

In the midday period 9:00–15:00, when solar irradiation is abundant, both systems engage in strategic recharging of the battery. GEP-ANFIS, however, exhibits superior charging efficiency, replenishing battery reserves 10–15% faster than ANFIS. This is evident in the faster SOC ramp-up, where GEP-ANFIS achieves a SOC of 46.0% by 15:00, compared to ANFIS’s 41.5%. These gains are attributed to GEP’s optimization of membership functions, particularly through narrowing the “Low SOC” trigger band, which prompts earlier and more assertive charging behavior. This strategic utilization of peak solar generation not only ensures that the battery reaches a higher charge level but also positions the system to handle evening loads more effectively.

During the evening discharge period (17:00–24:00), GEP-ANFIS outperforms ANFIS by deploying a more conservative discharge pattern, reducing battery output by 10–25%. This slower depletion rate not only meets industrial load demand without deficit but also culminates in a final SOC of 41.5%, compared to 38.5% in the ANFIS scenario providing greater energy reserve for early morning operations of the next day. Additionally, the hybrid system eliminates all load deficits, whereas ANFIS fails to meet approximately 11% of the load between 5:00 and 8:00, totaling a shortfall of 2,155 kWh. In essence, GEP-ANFIS achieves 100% load coverage, reduces battery cycling by 12%, and improves lifecycle sustainability underscoring its robustness for predictive energy scheduling in renewable-integrated, grid-independent industrial energy systems.

Case three: Grid connected Solar PV and battery only

The results from the predictive scheduling of generation using a grid-connected solar PV and battery system designed exclusively to serve industrial loads demonstrate clear performance advantages of the GEP-ANFIS hybrid controller over the standalone ANFIS model, particularly in terms of battery usage optimization and SOC management as shown in Fig. 8. During off-peak hours (1:00–6:00), where solar irradiance is negligible, the grid supplies 100% of the industrial load demand, totaling 2,016 kWh, thereby conserving battery resources. Both controllers maintain battery SOC at a constant 40% during this period, reflecting a successful strategy of grid prioritization for early-morning loads, which not only ensures full load coverage but also preserves battery health by avoiding unnecessary discharge cycles.

As solar generation ramps up from 7:00 onwards, the battery begins to support load supply and engage in recharging. From 9:00–16:00, both systems leverage PV surpluses to recharge the battery, but GEP-ANFIS exhibits more aggressive charging behavior, consistently storing more energy per hour and achieving a peak SOC of 68.0% at Hour 16, compared to 65.0% under ANFIS. This indicates improved energy harvesting and charge scheduling, due to GEP-optimized rule tuning, which enhances the responsiveness of the fuzzy inference system to solar fluctuations. This performance is particularly beneficial during transitional solar periods (e.g.,17:00–20:00), where GEP-ANFIS maintains higher SOC margins and discharges 20–30% less than ANFIS, thereby reducing depth of discharge and extending battery lifespan.

In the final discharge period (17:00–24:00), the superiority of GEP-ANFIS becomes more evident. While both controllers maintain 100% load coverage GEP-ANFIS ends the day with a higher final SOC of 52% versus ANFIS’s 50%, preserving critical reserve capacity for early next-day operations. Additionally, by reducing total discharge cycles by 25%, ANFIS-PSO effectively mitigates battery stress, making it a more sustainable and lifecycle-conscious choice for industrial microgrid applications. Overall, the integration of GEP within the ANFIS framework provides enhanced energy scheduling, minimizes battery wear, and ensures optimal coordination between grid support and renewable generation, aligning with the performance and longevity goals of grid-tied industrial energy systems.

Optimized sizing of solar PV and battery storage for industrial user

The system sizing analysis for a grid-connected solar PV and battery configuration designed exclusively to support industrial load requirements reveals the substantial scale of energy infrastructure needed to sustain a daily consumption of 4,269.14 kWh/day without compromise in reliability. To meet this load, a solar PV array of 776.21 kW is required, corresponding to 2,588 panels rated at 300 W each. This configuration ensures that sufficient solar energy can be harvested during peak sun hours to both serve real-time industrial demand and recharge the battery bank for use during non-generating periods. The chosen PV capacity reflects careful consideration of load factor, solar insolation profiles, and system losses, ensuring optimal utilization of solar resources under a hybrid grid-supportive environment.

On the storage side, the system requires a battery capacity of approximately 12.56 MWh (1,046,356.81 Ah at 12 V) to maintain full autonomy during periods of low or no solar availability. This equates to 5,232 units of 200Ah, 12 V batteries, translating to a total battery power capacity of 12.56 MW. Such a large-scale battery bank is not only essential to ensure round-the-clock load support but also acts as a buffer to smoothen the intermittency of PV generation. The sizing strategy ensures that the system can reliably manage peak demands, prevent battery deep discharge which degrades performance, and reduce dependence on the grid to emergency or backup use only enhancing both operational autonomy and cost-efficiency.

Furthermore, the integrated sizing of PV and battery systems reflects a well-optimized energy architecture for industrial microgrid applications, where high load continuity and power quality are non-negotiable. By leveraging grid connectivity strategically, the proposed system reduces battery cycling frequency and enables peak shaving, thereby extending battery lifespan and improving lifecycle economics. This level of technical sizing underscores the feasibility of transitioning industrial loads to low-carbon, resilient hybrid systems, offering a replicable model for sustainable energy integration in energy-intensive industrial zones.

Sensitivity analysis

The capacity reduction scenarios (20%, 40%, 60%, and 80%) presented in Tables 8 and 9 are designed to represent practical degradations or operational limitations that may occur in industrial hybrid PV–battery systems over time. These reductions emulate several real-world phenomena that affect both renewable generation and energy storage performance:

-

1.

Battery Capacity Degradation: Over its operational lifetime, a lithium-ion or lead-acid battery typically loses between 10 and 20% of its nominal capacity every 3–5 years, depending on depth of discharge (DoD) and temperature conditions. Hence, a 20–80% capacity reduction corresponds to approximately 4–20 years of cumulative degradation, covering early, mid, and end-of-life battery performance.

-

2.

PV Module Aging and Fouling: Photovoltaic panels experience an average 0.5–0.8% efficiency loss per year due to material degradation, dirt accumulation, and micro-cracking. The higher capacity reduction scenarios (e.g., 60–80%) therefore mimic conditions where partial shading, soiling, or inverter derating further reduce available generation capacity.

-

3.

Industrial Load Curtailment or Equipment Downtime: In industrial facilities, partial operational loads or equipment maintenance shutdowns can temporarily reduce total system capacity utilization. These conditions are approximated by 20–60% capacity reductions in the simulation.

Thus, each reduction scenario models a progressive decline in system performance that may result from component wear, maintenance constraints, or environmental stressors. Analyzing these conditions allows the model to evaluate the resilience and adaptability of the proposed GEP–ANFIS control strategy under realistic degradation and operational uncertainty.

The sensitivity analysis reveals that the GEP-ANFIS controller consistently outperforms the conventional ANFIS model in terms of unmet load reduction, SOC preservation, and grid dependence mitigation. At a 20% battery capacity reduction (near baseline), both controllers maintain full load coverage; however, GEP-ANFIS achieves a higher final SOC of 52% versus 50%, indicating better energy conservation. As battery capacity is further reduced to 40%, ANFIS begins to show vulnerabilities, with 2% unmet load and increased grid reliance, while GEP-ANFIS still maintains zero load deficits and avoids additional grid demand, thereby demonstrating superior adaptability to constrained storage conditions.

Under more critical reductions 60% and 80% the performance divergence becomes more pronounced. At 60% reduction, ANFIS incurs a 5% unmet load and increases grid usage to 2,196 kWh, compared to GEP-ANFIS’s lower unmet load of 2% and a reduced grid draw of 2,106 kWh. In the most extreme case (80% capacity cut), ANFIS’s performance deteriorates significantly, resulting in 12% unmet load and a critically low final SOC of 25%, whereas GEP-ANFIS caps unmet load at 8%, maintains a final SOC of 28%, and reduces grid dependence by approximately 33%.

At moderate PV reductions of 20% and 40%, both controllers successfully maintain zero unmet load, but GEP-ANFIS consistently delivers higher final SOC levels (+ 5%), indicating more effective energy conservation and better preparation for subsequent low-generation periods. At higher PV reduction levels (60% and 80%), the performance divergence becomes more significant. Under a 60% PV shortfall, ANFIS incurs a 5% unmet load and raises grid dependency to 2,216 kWh, whereas GEP-ANFIS reduces the unmet load to 2% and cuts grid reliance by 100 kWh. The disparity is more pronounced at 80% reduction, where ANFIS fails to meet 12% of the load, requiring 2,816 kWh from the grid, while GEP-ANFIS caps unmet load at 8% and limits grid usage to 2,516 kWh a 38% reduction in emergency energy imports. Additionally, GEP-ANFIS avoids deep discharge by maintaining SOC levels above 10%, which enhances battery longevity. These findings demonstrate the robustness, efficiency, and scalability of the GEP-ANFIS controller, especially in resource-constrained, PV-dominated microgrids, making it a strategic solution for sustainable industrial energy management while preserving battery longevity by avoiding deep discharge scenarios.

The superior performance of the proposed GEP–ANFIS framework extends beyond its low forecasting errors and high cost efficiency it is fundamentally rooted in the model’s structural adaptability, dual-layer optimization, and robustness to variability. Unlike conventional or PSO–ANFIS models, GEP–ANFIS dynamically evolves its fuzzy rule base through symbolic regression, allowing it to capture complex nonlinear relationships among variables such as solar irradiance, temperature, and battery state of charge. This adaptive rule evolution enhances generalization and minimizes overfitting, enabling the model to perform reliably under fluctuating weather and load conditions.

Furthermore, the integration of GEP’s global search with ANFIS’s local parameter tuning creates a powerful dual-layer optimization mechanism. GEP explores a wide solution space to identify effective rule structures, while ANFIS fine-tunes these configurations for precise learning and faster convergence. This synergy ensures stability, improved learning efficiency, and effective management of trade-offs between accuracy and cost optimization. Combined with its resilience to data noise and operational uncertainty demonstrated in the sensitivity analyses (Tables 8, 9) the GEP–ANFIS framework represents not only a numerically superior but also a structurally and adaptively intelligent advancement in hybrid energy management systems.

Economic analysis

Daily energy economic analysis

The comparative analysis of daily energy cost across three predictive generation scheduling configurations Grid-only, PV and Battery, and Grid-connected PV and Battery demonstrates a consistent cost advantage when using the GEP-ANFIS controller over the conventional ANFIS system as shown in Fig. 9. In the Grid-only scenario, the energy cost under ANFIS is 1,440,139 UGX/day, while GEP-ANFIS achieves a 7.4% reduction, lowering it to 1,332,081 UGX/day. This margin becomes more pronounced in hybrid configurations: when operating with PV and battery only, GEP-ANFIS cuts energy cost to 1,214,656 UGX/day, representing a 6.5% improvement over ANFIS. The most cost-effective outcome is observed under the Grid-connected PV and Battery scheme, where GEP-ANFIS achieves a daily cost of 1,093,643 UGX, outperforming ANFIS by 6.3%, and yielding the lowest operational cost across all tested strategies.

These findings confirm the economic superiority of hybrid generation scheduling with intelligent control optimization. The cost-saving trends across all configurations indicate that GEP-ANFIS, through its evolutionary rule refinement and adaptive decision-making, significantly improves generation dispatch and resource utilization. The hybrid grid-PV-battery scheme emerges as the optimal configuration, minimizing reliance on high-cost grid energy during peak hours while effectively leveraging renewable generation and storage flexibility. Therefore, GEP-ANFIS not only enhances operational efficiency but also provides substantial economic benefits, making it highly suitable for cost-sensitive, energy-intensive industrial applications in grid-constrained environments.

Long term economic analysis

To enhance techno-economic realism, the life-cycle cost model was expanded to include battery degradation, maintenance, and component replacement effects. Battery degradation was modeled using a state-of-health (SOH) decay rate of 2% per year, while O&M costs were set at 2% of the total capital cost for PV and storage systems. Battery replacement is assumed at 50% of the initial cost at mid-life (year 5), and a salvage value of 10% was applied to the PV array at the end of the 20-year horizon.

The long-term cost analysis over a 20-year planning horizon reveals a significant reduction in total energy system expenditure when advanced predictive scheduling models ANFIS and GEP-ANFIS are employed compared to the baseline HOMER optimization framework as illustrated in Fig. 10. The HOMER-based configuration, widely recognized for its deterministic optimization capabilities, yields a total system cost of 12.81 billion UGX. In contrast, the ANFIS-based model reduces this cost to 8.53 billion UGX, representing a 33.5% reduction, primarily due to enhanced flexibility in load forecasting and real-time scheduling, which limits over-provisioning of grid and storage resources.

More notably, the GEP-ANFIS model further improves economic performance, achieving a total cost of 7.98 billion UGX, which is 6.5% lower than ANFIS and 37.7% lower than HOMER. This superior cost efficiency stems from GEP’s evolutionary tuning of fuzzy inference rules, enabling optimal utilization of renewable energy and battery dispatch strategies under varying load and generation profiles. The results underscore the potential of hybrid intelligent scheduling algorithms to outperform traditional static optimizers over long operational lifespans, making GEP-ANFIS a strategically advantageous tool for cost-minimized, future-ready energy planning in industrial microgrid environments.

Conclusion