Abstract

This study presents a framework for detecting polished asphalt pavement surfaces by integrating texture-based image analysis with interpretable Machine learning (ML). Polishing, caused by aggregate degradation and bitumen aging, alters surface texture and reduces skid resistance, posing a safety risk. A real-world dataset of 12,480 pavement images was analyzed using 24 texture features derived from the Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), capturing directional spatial patterns of surface roughness. Several ML models were trained and optimized with the Hyperopt framework, with a Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) achieving the highest classification accuracy of 96.1%. Feature contributions were interpreted using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), providing physical insight into texture-driven polishing mechanisms. Although a ResNet50-based CNN achieved slightly higher accuracy (98.7%), its high computational cost limits practical deployment. The proposed GLCM–ML approach offers an interpretable, efficient, and physics-aware tool for pavement condition monitoring, with potential to enhance predictive modeling of surface texture evolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development and maintenance of road networks are crucial for ensuring sustainable serviceability, enhancing connectivity between urban and rural areas, and fostering trade and investment. Enhanced road infrastructure increases accessibility, lowers transportation costs, and improves productivity, ultimately boosting economic output1. Pavement is a fundamental component of highway infrastructure, essential for ensuring the safety and efficiency of transportation systems2. Pavement Management System (PMS) is a critical component of transportation infrastructure, focused on systematically monitoring, assessing, and maintaining road surfaces to ensure safety, durability, and efficiency. Effective pavement management extends roadway lifespan, reduces repair costs, and enhances user satisfaction by ensuring good travel experiences3.With rising traffic volumes and environmental factors accelerating pavement deterioration, adopting advanced technologies and methodologies for pavement assessment and rehabilitation becomes essential4.

Asphalt pavements are susceptible to various types of distress that can undermine their structural integrity and serviceability. Key contributing factors include traffic loads, environmental conditions, material properties, and construction practices5. Flexible pavement distresses manifest in various forms, generally classified into two categories: cracking—encompassing fatigue, block, edge, longitudinal, reflection, and transverse cracking—and non-cracking distresses, including rutting, potholes, polished surfaces, raveling, and bleeding6. Therefore, Pavement Distress Detection (PDD) is crucial for maintenance planning, aiming to extend the service life of road infrastructure. PDD identifies and measures various types of pavement distresses, facilitating a reliable methodological approach to road maintenance management. Automatic and non-destructive distress detection is essential for effective pavement management7.

In recent years, numerous studies have employed ML and deep learning (DL) techniques in transportation and infrastructure, highlighting the growing significance of modern computational methods in engineering. For instance, a texture–image coupled fusion approach has been proposed for pavement skid resistance measurement, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrating image-based and computational models in pavement analysis8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Over the past decade, image processing technology has emerged as a transformative tool for assessing and maintaining road pavement infrastructure. By utilizing advanced algorithms and ML techniques, researchers and engineers can efficiently analyze images of pavement surfaces to detect distresses such as cracks, potholes, patch, and surface deformations, bleeding surpassing traditional methods15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Additionally, recent research over the past four years has investigated distresses related to changes in pavement texture, including bleeding and raveling20,22. Inadequate and delayed maintenance can accelerate the deterioration process; therefore, timely detection of each distress can significantly enhance pavement longevity and performance. However, the automatic detection of polished aggregates in asphalt pavement using computer vision remains an underexplored area in the field.

Polished aggregate defect refers to a surface condition in which the binder wears away, exposing coarse aggregate on the pavement. This occurs when aggregate particles in the asphalt surface are worn down under traffic, resulting in a smooth, shiny finish that significantly reduces skid resistance. This phenomenon is a critical concern in roadway design and maintenance due to its substantial impact on vehicle safety and performance. The reduction in friction increases the risk of accidents, particularly in wet conditions, emphasizing the need to study polished pavements to enhance highway safety. Research has shown that the type of aggregate and mix design significantly influence the rate of polishing and the overall performance of asphalt pavements. In this context, a laboratory-based close-range photogrammetric analysis on ring-shaped asphalt mixture specimens was conducted to investigate the relationship between surface texture and friction, providing valuable insights for skid resistance evaluation. Understanding the mechanisms and implications of polished asphalt pavements is therefore essential for developing effective maintenance strategies and improving long-term road safety[23-28].

Aggregate characteristics significantly influence the surface texture of pavement. This is a crucial factor in skid resistance. However, road surfaces are continuously exposed to traffic and harsh weather, leading to aggregate degradation and polishing, which accelerates the deterioration of surface friction. Aggregates that are less prone to abrasion and polishing typically demonstrate better friction performance in the field. Pavement texture comprises two components: Micro-texture and macro-texture. Micro-texture relates to the properties of aggregates, often expressed as Polished Stone Values (PSV), while macro-texture pertains to the surface texture of asphalt mixes29,30,31,32. Consequently, over time, the micro-texture and macro-texture of the pavement surface will degrade due to the types of materials used, traffic loads, and environmental factors. Analyzing the extent of wear on the actual road surface may help reduce the rate of accidents.

Image processing technology and ML methods enhance the accuracy of pavement condition assessments and enable real-time monitoring, facilitating timely maintenance interventions and optimal resource allocation33. As previously mentioned, polished pavement surfaces directly affect pavement texture. Therefore, combining texture-based image processing methods with ML can serve as an effective approach for the automatic detection of this damage.

Recent studies have shown the feasibility and high accuracy of image-based approaches for estimating pavement texture measures and Mean Texture Depth (MTD). Weng et al. (2022) proposed a rapid MTD estimation method using image-based multiscale features, introducing indices such as Maximum Particle Size Distribution (MPSD) and Relative Energy Distribution (RED) derived via multiscale segmentation and 2D-wavelet decomposition, and demonstrated good agreement with traditional measurements34. Moreover, several works have extended image-based analysis using ML and DL models: Gökalp et al. (2024) developed a 2-D image processing plus ANN approach for MTD estimation on chip-sealed samples, showing competitive results against sand-patch and hydrotimer methods, while Pan et al. (2023) proposed lightweight few-shot deep models for pavement texture classification under limited data scenarios35,36.

Nhat-Duc Hoang proposed an automated approach for detecting asphalt pavement raveling using image-based texture features combined with ML, demonstrating effective classification of raveling conditions across diverse samples37. In 2021, researchers proposed an approach combining 3D imaging with ML to automatically detect and classify asphalt pavement raveling, demonstrating improved accuracy and scalability compared to traditional inspection methods38.

Hoang Nhat-Duc and Tran Van-Duc evaluated several ML models for classifying asphalt pavement raveling, finding that advanced approaches like Histogram-Based Gradient Boosting Classification Machine HGBCM can achieve high accuracy and efficiency in image-based pavement assessment39. Additionally, researchers proposed a computer vision approach for detecting asphalt pavement segregation by combining texture analysis with ML techniques, including Attractive Repulsive Center-Symmetric Local Binary Pattern (ARCSLBP) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), demonstrating effective extraction of surface features and high classification accuracy40. Another study, For the automatic detection of raveled areas and the categorization of their severity, the employed texture descriptors include Local Binary Pattern (LBP), Center-Symmetric Local Binary Pattern (CSLBP), Completed Local Binary Pattern (CLBP), and Local Ternary Pattern (LTP)41.

Daneshvari et al. proposed a new approach LBP-GLCM texture analysis with an XGBoost classifier to detect raveling in asphalt pavements. By employing LBP-GLCM, the researchers extracted distinctive texture features that characterize raveling degradation patterns. These features were then used to train the XGBoost model, selected for its balance of accuracy and efficiency in handling high-dimensional data. The results show that the XGBoost classifier achieves high accuracy in raveling detection, outperforming traditional methods in both speed and reliability. This approach provides a cost-effective and scalable solution for automated pavement assessment, enhancing maintenance planning and improving road safety42.

In a separate study, the authors presented an innovative approach for detecting asphalt pavement bleeding, specifically addressing challenges associated with imbalanced datasets. They employed an anomaly detection framework that treats bleeding as a rare event within a majority of non-bleeding samples. This method effectively leverages image data to capture subtle visual features indicative of bleeding, overcoming traditional challenges related to insufficient or imbalanced data for training conventional ML models. The results show that the anomaly detection approach achieves robust detection accuracy, even with limited bleeding data, making it a promising solution for scalable and automated pavement condition monitoring in real-world applications characterized by data imbalance43.

In a recent study conducted in 2024, a hybrid approach was developed that combines texture analysis techniques with tree-based ensemble classifiers to detect two common forms of pavement distress: bleeding and raveling. Using 2D image data of asphalt surfaces, a set of texture features was extracted using Histogram Equalization (HE)-GLCM and LBP-GLCM. The results demonstrated the high accuracy of tree-based methods when combining the two feature sets, highlighting their effectiveness for automated pavement evaluation. This approach supports efficient and scalable monitoring systems, enabling timely maintenance interventions and improving pavement management strategies44. At the experimental scale, researchers investigated the evolution of aggregate texture, analyzed morphological characteristics, and evaluated wear resistance45,46.

Despite significant progress in image-based detection of common asphalt distresses—such as raveling, bleeding, segregation, and patching—the automated identification of pavement surface polishing at the field scale remains largely underexplored. This distress type, caused by the progressive smoothing of aggregate particles, leads to a substantial reduction in skid resistance and thereby poses a serious threat to traffic safety. However, due to its often subtle visual appearance, it is frequently overlooked in conventional inspections.

Previous research has primarily focused on general pavement surface conditions or coarse-level distress categories, whereas the subtle microtexture variations associated with surface polishing have received limited attention. Moreover, existing image-based approaches either depend on handcrafted texture features with limited interpretability or utilize DL models that act as “black boxes” and require extensive datasets. Consequently, there remains a lack of a reliable and explainable framework capable of detecting and interpreting polished asphalt surfaces under real-world conditions. To address this research gap, the present study aims to develop an interpretable, texture-based ML framework that can automatically identify surface polishing using field-acquired images. The specific objective is to achieve a reliable differentiation between polished and unpolished surfaces through statistical texture descriptors combined with explainable learning techniques.

The key contributions of this work are as follows:

-

Integration of texture analysis and ML: This research pioneers the application of image-based texture features in combination with advanced ML models to detect and classify surface polishing under field conditions.

-

Automated hyperparameter optimization: The Hyperopt framework is utilized to fine-tune model hyperparameters, improving predictive accuracy and generalization across varying pavement conditions.

-

Interpretable ML via SHAP analysis: Multiple ML algorithms are employed for classification, with SHAP used to interpret the role of each texture feature in model predictions, enhancing transparency and trustworthiness.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents the data collection procedure, image preprocessing, and texture analysis techniques. Section 3 discusses the ML models and their performance. Section 4 concludes the study with insights into future applications and potential improvements.

Data collection and methodology

In this section, the dataset preparation methods will be explained first. Next, the image processing approach based on GLCM texture analysis, along with the extracted features from the two classes of images under study, will be presented. The ML algorithms applied in this study will then be discussed. Following that, the optimizer (Hyperopt) used to determine the optimal hyperparameters for the models will be described. The SHAP analysis method employed to examine the impact of each feature will also be explained. Finally, the evaluation and validation criteria for assessing the accuracy of the models will be presented. In summary, the overall process and stages of the research are outlined in the flowchart in Fig. 1.

Data collection

The research began with field visits to asphalt pavement surfaces, where digital images were captured from two categories: Non-Polished surfaces, which represent typical fine and coarse textures, and Polished surfaces, which consist of areas worn down by prolonged traffic and lacking sufficient texture. High-resolution images were taken with a digital camera under controlled lighting conditions to minimize shadows and reflections, and were subsequently stored in a standardized format for further processing. The image collection process was carried out under cloudy weather conditions to minimize the impact of varying light on image quality. The identification of Non-Polished and Polished surfaces was performed during field observation based on visual texture characteristics such as aggregate exposure, reflectivity, and smoothness, which are consistent with typical indicators used in pavement surface evaluations (Fig. 2).

Figure 3 illustrates the geographical distribution of the surveyed pavement sections within the Seyed Khandan area of Tehran, Iran. The selected locations include several asphalt road segments along Resalat Highway (Fig. 3-B) and adjacent urban streets such as Ostadhassan Bana Street (Fig. 3-A) and Shariati Avenue (Fig. 3-C). The yellow-dashed rectangles (A, B, C) indicate the general areas where field image acquisition was conducted. The sub-frames labeled A1–A4, B1–B4, and C1–C4 provide enlarged overviews of representative zones within each corridor to depict surrounding traffic and site context. These zoomed areas are intended solely to illustrate the approximate sampling locations and urban environment, rather than to display surface texture details, which were captured separately through field photography.

Geographical overview of the pavement sampling sites in the Seyed Khandan area of Tehran, Iran. (A) Ostadhassan Bana Street, (B) Resalat Highway, and (C) Shariati Avenue. Yellow-dashed rectangles mark the general survey corridors, and red boxes (A1–A4, B1–B4, C1–C4) indicate zoomed sub-areas showing traffic and environmental context.

For this purpose, RGB images were captured at a resolution of 9 megapixels using a Galaxy S23 FE camera, positioned at a distance of 1 m. To ensure the reliability of the data, images of Non-Polished pavement surfaces—including newly constructed asphalt, low to moderate raveling, potholes, various types of cracks, traffic markings, and patches—were selected. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate a sample from the original collected image dataset, which was used for training and validating the computer vision approaches.

The images were cropped to a size of 250 × 250 pixels, and non-standard areas were removed. This size was selected to adequately capture local surface texture features, such as aggregate exposure and micro-texture, while keeping the input size manageable for the ML models. Using 250 × 250 pixels reduces computational complexity and training time without compromising classification accuracy. The total number of images generated by the expert was 12,480, which were classified into two categories: 6,240 images of Non-Polished surfaces and 6,240 images of Polished surfaces.

Feature extraction

This section outlines the methodology for extracting texture features from asphalt images using the GLCM. This robust statistical technique analyzes the spatial relationships of pixel intensities, offering critical insights into the texture characteristics of pavement surfaces.

Image preprocessing

Prior to GLCM analysis, the acquired images undergo preprocessing to enhance texture details and reduce noise. This includes: grayscale conversion images are converted to grayscale to simplify the analysis by focusing on intensity values. In the case where images are converted to grayscale, the three RGB channels are transformed into a single channel. This not only reduces the storage size and increases computational efficiency but also enables the GLCM analysis to be performed on grayscale images47.

GLCM features extraction

Since the surface coarseness of Non-Polished and Polished areas is expected to differ, this study utilizes GLCM features extracted from digital images. The GLCM is particularly suitable for this task, as this texture analysis method captures the spatial repetition of specific gray-level intensity patterns48.

Let r denote the distance (in pixels) between two pixel pairs, and θ represent the angular relationship between them. The GLCM, denoted as Pδ, is a statistical matrix that quantifies the probability of two pixels having intensity values i and j at a given spatial offset (r, θ). It is constructed by counting the frequency of co-occurring pixel intensities across the image at specified distances and angles49.

Following the recommendations of Haralick, Shanmugam, and Dinstein, the GLCM is typically computed for r = 1 (adjacent pixels) and θ = 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135° (four primary directions). From each GLCM, texture descriptors such as contrast, correlation, entropy, energy, homogeneity, and dissimilarity can be derived and used for texture classification (Tables 1 and 2)50.

The GLCM was used to quantify the spatial distribution of gray levels in pavement surface images. Let P(i, j) denote the normalized co-occurrence probability between gray levels i and j at a specified displacement vector. Here, i and j are the gray-level intensities of the reference and neighboring pixels, respectively, and G is the total number of gray levels considered in constructing the GLCM. In this study, the grayscale images were quantized into G = 256 Gy levels before feature extraction. Using these definitions, several statistical texture descriptors, including contrast, correlation, angular second moment, energy, homogeneity, and dissimilarity, were calculated as summarized in Table 1.

Table 2 presents GLCM feature values for two representative images from each class across four directions as illustrative examples. While no single feature shows a consistent difference between Non-Polished and Polished surfaces across all directions and samples, the combination of these descriptors enables the proposed GLCM-Hyperopt-BPNN model to effectively discriminate between the two texture types.

ML methods

In general, there are two types of learning: supervised and unsupervised. Unlike unsupervised learning, which utilizes unlabeled data, supervised learning uses labeled data to training. Supervised learning can be applied to tasks such as regression and classification. When there are exactly two classes, the task is referred to as binary classification, whereas if there are more than two classes, it is termed multi-class classification. The classification task involves deriving a hypothesis, or classifier, from a set of labeled data instances to accurately predict the labels of new, incoming data instances51,52.

In this research, we address the classification of two groups of images labeled as Non-Polished and Polished. Consequently, supervised learning algorithms are employed. Specifically, KNN, RF, ET, and BPNN classification models are utilized. A brief introduction to these methods is provided below. All models were trained using the Scikit-Learn (sklearn) package in Python with default settings.

K-nearest neighbors (KNN)

The KNN algorithm is a versatile technique applicable to both classification and regression tasks. However, in industrial applications, it is predominantly recognized for its effectiveness in solving classification problems. KNN identifies the k-nearest learning samples within the attribute space as input. By analyzing all data points, it determines the group to which a given data point belongs, making it a powerful tool for classification tasks. In fact, the KNN algorithm assigns new data points to a cluster based on the nearest k neighbors, determined using a predefined distance metric53.

Decision tree (DT)

A DT is a type of supervised ML model in which a series of Boolean (i.e., true or false) decisions are made to classify data into categorical bins. The supervised nature of the model means that, during training, each set of input variables (e.g., β, Hs, Tp, etc.) must be labeled with the expected output value. During training, the DT determines how to split each leaf into branches in a way that minimizes the Gini coefficient in each resulting leaf. The Gini coefficient quantifies the homogeneity of the values in each leaf during training54.

Extra trees (ET)

The Extremely Randomized Trees (Extra Trees) algorithm is an ensemble learning method that enhances classification performance by constructing multiple decision trees and aggregating their predictions. Unlike traditional RF, ET introduce additional randomness by selecting split points completely at random for each candidate feature, rather than choosing the best split based on criteria such as Gini impurity or entropy. This characteristic reduces variance while maintaining competitive accuracy, making the algorithm particularly robust against overfitting, especially when dealing with high-dimensional datasets. Furthermore, ET exhibit computational efficiency, as they do not require bootstrapping and instead utilize the entire training dataset for tree construction. These advantages make ET a valuable choice for classification tasks, particularly in domains requiring high interpretability and resilience to noise. The algorithm is often used as a classifier and is compared with other algorithms in various studies55,56.

Random forest (RF)

RF is a ML technique that integrates multiple DTs to enhance classification accuracy through ensemble learning. During the training process, it evaluates the significance of each feature in the decision-making process. The algorithm typically employs the bootstrap method to generate multiple training sets by sampling the data with replacement. Each decision tree is constructed using these samples, and the final classification result is determined through majority voting. Additionally, the algorithm assigns weights to features based on their importance in classification57,58.

Support vector machine (SVM)

The SVM algorithm is a powerful supervised learning method used for both classification and regression tasks. It works by identifying an optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between different classes in a high-dimensional feature space. SVM creates a multi-dimensional vector space, where each sample point is represented as a vector, and all vectors are separated by a hyperplane. The vectors closest to the hyperplane, known as support vectors, determine its position. The objective of SVM is to find a hyperplane that maximizes the margin between the support vectors of the training data58,59.

Backpropagation neural networks (BPNN)

The BPNN method was originally introduced by Paul Werbos in 1974 and later popularized by Rumelhart and McCelland in 198660. It is a widely used supervised learning algorithm for classification tasks, based on Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and inspired by the human brain. Its theoretical foundation lies in the universal approximation theorem, which states that a sufficiently deep neural network with nonlinear activation functions can approximate any continuous function. BPNN utilizes the backpropagation algorithm, which applies gradient descent to iteratively adjust neuron weights, minimizing the error between predicted and actual outputs. The network consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, with activation functions. Despite its strong learning capabilities, BPNN requires careful hyperparameter tuning, including learning rate selection and network architecture optimization, to prevent overfitting and ensure robust performance. Due to its flexibility and ability to learn intricate patterns, BPNN is widely applied to classification problems across various domains61,62. The hyperparameters for each classification algorithms (KNN, RF, DT, ET, SVM and BPNN) utilized in this study are provided in Table 5.

Hyperopt library

To achieve optimal performance in ML models, hyperparameter tuning is essential. Also known as hyperparameter optimization, this process involves testing various combinations of hyperparameters and evaluating their performance on a validation set. Common methods include grid search and random search algorithms63.

Hyperopt is a powerful Python library designed for optimizing hyperparameters in ML and DL models using Bayesian optimization, Tree-structured Parzen Estimators (TPE), and other global search algorithms. Unlike traditional grid or random search methods, Hyperopt efficiently explores the hyperparameter space by balancing exploration and exploitation, significantly reducing computational costs. Additionally, it supports parallel execution and integrates seamlessly with popular ML frameworks, making it well-suited for complex optimization tasks. Due to its adaptability and efficiency, Hyperopt is a valuable tool for enhancing model performance, particularly in high-dimensional search spaces, where optimal hyperparameter selection is crucial for achieving robust and reliable results in data-driven research. In this study, Hyperopt is employed to perform Bayesian optimization for various ML models. K-fold cross-validation is a widely used technique in ML to reduce the risk of overfitting, which occurs when a model performs well on the training data but poorly on new, unseen data. It is applied at this stage to determine and optimize the best hyperparameters for model evaluation64.

SHapley additive explanations (SHAP) analysis

SHAP, grounded in cooperative game theory, assigns Shapley values to individual features, providing a mathematically rigorous framework for evaluating their influence on classification outcomes. To enhance the interpretability of the developed ML models, SHAP analysis was employed to quantify the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions13,63,65. In this study, SHAP values were computed to identify the most influential features driving the proposed model’s decisions. The analysis was conducted using the SHAP Python library, with feature importance visualized through summary plots to provide deeper insights into feature interactions.

Evaluation criteria

After training, the model’s performance was evaluated using standard metrics. The confusion matrix is a method used to analyze the performance of a given algorithm. In this study, the performance and accuracy of classification models are evaluated and compared using metrics such as F1-Score, Precision, Recall, and Accuracy, as defined by Eqs. (1) to (4). These metrics are derived from four fundamental components: True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN). In this matrix, the actual class label refers to the true label of the data, and the predicted class label represents the classification output generated by the algorithm66,67.

Results and discussion

Feature extraction

This section of the research evaluates the performance of the proposed computer vision methods for identifying polished asphalt pavement surfaces. It begins with data collection, followed by the determination and extraction of features from the two target image classes. First, the RGB images are converted to grayscale, and then the GLCM method is applied to the grayscale images.

As previously noted, Class 0 refers to areas of asphalt pavement that are Non-Polished, including both fine and coarse textures. In contrast, Class 1 represents areas where the asphalt surface is visibly Polished, meaning the texture has been worn away, resulting in the absence of fine and coarse textures. This polished condition in Class 1 is hazardous, as it significantly reduces the surface’s skid resistance and increases the likelihood of accidents.

To train the ML algorithms, field surveys were conducted to create an image dataset of pavement surfaces. The dataset included samples classified as Non-Polished (coded as Class 0) and Polished surfaces (coded as Class 1). It is important to note that the identification, labeling, and collection of images were performed during field visits by experts specializing in PMS.

According to the definition presented in Sect. 2, six indices—Contrast, Correlation, Energy, Homogeneity, ASM, and Dissimilarity—were extracted in four directions (θ = 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135°). A total of 6 × 4 = 24 features were extracted for each dataset, with the results presented as an example in Tables 3 and 4. These features represent the textural information of the pavement image.

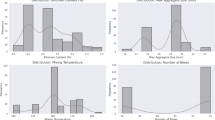

As shown in Tables 3 and 4, each feature exhibits variations. This difference is more pronounced in certain features or directions compared to others. A comparison of the sample results in these tables reveals that, in general, feature values differ between the two classes. The distribution of these texture features for both Non-Polished and polished pavement categories is illustrated in Fig. 6. Statistical summaries, including the mean and standard deviation of key GLCM-based descriptors (i.e., contrast, correlation, energy, and homogeneity), indicate observable but moderate differences between the two surface conditions, reflecting subtle yet meaningful changes in surface microtexture due to polishing. These subtle differences suggest that even minor changes in microtexture can be captured by the selected GLCM-based features, providing a basis for training ML models to differentiate Polished from Non-Polished surfaces.

These differences in feature values can be attributed to the inherent characteristics of the textures of the two surfaces, as well as the fundamental modifications made to the texture of the polished pavement surface. These modifications result in a substantial reduction in both macro- and micro-textures, which is reflected in pixel intensity values and, consequently, in the extracted texture-based features. Based on these values, it is predicted that these features will have the most significant impact on training the models and classifying the two classes under study.

Hyperopt- based model optimization

The Hyperopt-based optimized KNN, DTs, RF, ET, SVM, and BPNN models have been developed in the Python programming environment. Due to the significant differences in the values of the extracted features, this study standardizes them using the Z-score equation to prevent bias when evaluating features with varying magnitudes. The Z-score equation is defined as (Eq 5):

In this context, Xn denotes the normalized features, and X denotes the raw features, while \(\:\mu\:\) and STD represent the mean and standard deviation of the training features, respectively.

Subsequently, Hyperopt begins the search process to identify the optimal configuration of each model by generating hyperparameter values, as shown in Table 5. Additionally, the number of iterations for the search loop is set to 100. The dataset was divided into two subsets: 70% for training and 30% for testing. A 5-fold cross-validation procedure was applied to the training data to determine the optimal hyperparameters. As a result, the performance of each ML model gradually improves until the stopping condition is met. Once the search process concludes, the optimized hyperparameters for each ML model are ready to detect polished asphalt in new image samples. The test set was subsequently used to evaluate the model’s generalization performance and to ensure that overfitting had not occurred. Furthermore, Z-score normalization was employed to standardize the range of input features. In this way, the optimal hyperparameters are fixed and remain unchanged during the subsequent evaluation process. The optimal hyperparameters for each ML model are presented in Table 5.

Considering the optimal hyperparameter values obtained for each classification model used in this study, the next stage involved training the algorithms using these hyperparameters. The final results, including the accuracies achieved for each model, will be presented and interpreted in the next section.

Computational results and performance comparison of the model

As mentioned in the methodology section, this study aimed to identify the most effective model by evaluating six ML classifiers: SVM, RF, KNN, ETs, DT, and BPNN. These models were selected based on their demonstrated effectiveness in previous studies related to pavement distress classification and other classification tasks.

To reliably evaluate the predictive ability of the proposed computer vision model, the training and testing processes are repeated 30 times. This ensures that the model’s ability to classify asphalt is assessed through statistical measurements obtained from these independent iterations. In other words, this approach ensures that the entire dataset participates in both the training and testing processes.

In each run, the model is randomly fitted with 70% of the data and evaluated on the remaining 30%. During each run, precision, recall, and F-score values are computed for each class, as well as for the overall model performance. The statistical indicators related to these metrics (evaluation criteria) are then calculated and reported as the mean and standard deviation. The results of the evaluation criteria used in this study are presented separately for each model in Table 6.

The findings indicate that the accuracy of the applied models ranges from 87% to 96.10%. Among the models (Fig. 7) used for classifying the target classes, the least accurate in distinguishing Polished pavement surfaces from Non-Polished surfaces is the DT model, with an accuracy of 87.20%, while the highest accuracy is achieved by the BPNN model, at 96.10%. This confirms that the BPNN model demonstrates strong performance with acceptable accuracy, showing a significant improvement of more than 8% compared to the DT model in distinguishing polished surfaces.

Additionally, the results indicate that the SVM algorithm performs well, achieving an accuracy of 95.4%. However, it exhibits a slight performance difference when compared to the BPNN model. Based on accuracy rankings, the models from highest to lowest performance are as follows: BPNN, SVM, ET, KNN, RF, and DT.

As shown in Table 6, the proposed method, GLCM-Hyperopt-BPNN, proves to be both effective and efficient, as the evaluation metrics for both classes and overall performance exceed 95%. Furthermore, the deviation in F1-score values is minimal—less than 4%—indicating that the values range between 91% and 99%. This narrow range demonstrates the stability of the proposed method.

According to the obtained results, the GLCM feature extraction method, based on texture, was used to train classification models and identify polished surfaces. This approach proved particularly effective for the proposed BPNN and SVM models, as texture-based distinctions successfully separated the two classes, confirming the reliability of the model outputs.

While deep transfer learning allows knowledge to be transferred from a source domain to a pre-trained deep neural network—reducing the required target-domain data and training time—it generally improves overall performance. To evaluate CNN performance, several models were applied, with ResNet-50 achieving the best accuracy (Table 7). The CNN model showed less than 3% difference in accuracy compared to the proposed GLCM-Hyperopt-BPNN method.

To evaluate and compare the performance of CNN methods, several models were applied, with ResNet-50 achieving the highest accuracy (Table 7). The results show that the CNN model’s accuracy differs by less than 3% from that of the proposed GLCM-Hyperopt-BPNN method. Despite requiring considerably less computational resources and training time than CNN-based DL methods, the GLCM-Hyperopt-BPNN approach achieved comparable and satisfactory performance in classifying the target classes. This demonstrates its practical efficiency while maintaining competitive accuracy, with actual performance exceeding 95%. Considering both computational costs and the need for high-performance systems, the GLCM-Hyperopt-BPNN model emerges as the most suitable and optimal algorithm for this study.

Feature analysis

The SHAP summary violin plot presented in Fig. 8 illustrates the influence of various features on the output of the GLCM-Hyperopt-BPNN model. The x-axis represents the SHAP values, indicating both the magnitude and direction of each feature’s impact on the model’s predictions. Features with SHAP values to the right of zero contribute positively to the prediction, while those to the left have a negative effect.

This analysis provides a comprehensive interpretability framework for assessing the influence of textural features in classifying polished versus normal asphalt pavement surfaces. Among the most influential features, Homogeneity at angles 0°, 45°, and 90° exhibits the highest positive SHAP values corresponding to greater feature magnitudes, indicating a strong association with the polished surface class. This observation aligns with the physical characteristics of polished pavements, which typically display more uniform texture patterns due to aggregate wear. Moderate contributions from Correlation metrics suggest the model’s sensitivity to directional texture alignment. Features computed at 135°, including ASM and Energy, demonstrate minimal impact.

These results underscore the pivotal role of GLCM-derived textural Homogeneity and Dissimilarity in accurately distinguishing pavement surface conditions within ML-based assessment models.

To further validate the consistency between global and local interpretability, local SHAP analysis was performed on randomly selected samples from each class (Figs. 9 and 10). The local SHAP force plots complement the global SHAP summary (violin) plot by visualizing how individual features contribute to specific model predictions. For example, in Fig. 9, model outputs of f(x) = 0.14 and f(x) = 0.10 are substantially below the base value of 0.39, indicating strong confidence in classifying these samples as Non-Polished pavements. In contrast, Fig. 10 shows outputs of f(x) = 0.95 and f(x) = 0.96, clearly above the base, reflecting high-confidence predictions for the Polished surface class.

Consistent with the global SHAP analysis, features such as Homogeneity and Dissimilarity at 0°, 45°, and 90°, along with Correlation at 45°, emerged as the most influential contributors, collectively driving the model’s predictions toward the Polished class. Although the magnitude and direction of SHAP values vary across individual instances, the consistently high importance of these directional texture features reinforces their reliability as discriminative indicators. This agreement between local and global interpretability demonstrates the robustness and transparency of the model’s decision-making process.

Moreover, the SHAP-based analysis provides a clear physical interpretation aligned with the actual texture structure of pavement surfaces. Polished surfaces exhibit smoother and more uniform patterns, whereas Non-Polished surfaces are relatively rougher with stronger gray-level variations. Accordingly, Homogeneity plays a dominant role in distinguishing these conditions by reflecting the uniformity of pixel intensity. Dissimilarity and Correlation also contribute notably, indicating that both gray-level differences and directional relationships between texture elements are essential for characterizing surface conditions. Overall, these results emphasize that directional texture metrics are robust and physically meaningful indicators for ML-based pavement surface assessment.

Conclusion

Asphalt surface polishing significantly reduces skid resistance and poses safety risks, highlighting the need for timely and accurate detection. This study proposed a computer vision-based framework integrating texture feature extraction and ML for automated identification of Non-Polished and Polished asphalt surfaces. The analysis demonstrated that Homogeneity features were most influential in distinguishing surface types, aligning with physical characteristics of pavement wear. The proposed GLCM–BPNN model achieved optimal classification performance, demonstrating the effectiveness of the developed framework. The BPNN and SVM classifiers delivered strong performance, outperforming other models such as RF, KNN, DTs, and ET. While a CNN-based model (ResNet50) achieved slightly higher accuracy, the proposed GLCM–ML framework offers comparable performance with significantly lower computational cost, making it practical for large-scale field applications.

The proposed method has several practical applications. Road maintenance agencies can employ it for rapid and automated detection of Polished and Non-Polished (normal) asphalt surfaces, enabling data-driven decisions for maintenance planning and safety interventions. Contractors and engineers can use it to evaluate pavement surface conditions over time and identify early signs of polishing or surface wear. Furthermore, the approach can be integrated into intelligent road management systems to continuously monitor surface conditions and predict potential hazards, such as slipperiness. These applications highlight the method’s potential to enhance operational efficiency, minimize the need for manual inspections, and deliver quantitative and reproducible outcomes for pavement management. Future research will aim to improve system robustness by incorporating advanced texture analysis techniques, expanding the dataset to include diverse lighting and weather conditions, and leveraging large-scale image databases to enhance model generalization and noise resistance under real-world scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Duranton, G. & Turner, M. A. Urban growth and transportation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 79, 1407–1440 (2012).

Banister, D. Unsustainable Transport (Routledge, 2005). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203003886

Shahin, M. Y. Pavement Management for Airports, Roads, and Parking Lots (Chapman & Hall, 1994).

Bhandari, S., Luo, X. & Wang, F. Understanding the effects of structural factors and traffic loading on flexible pavement performance. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 12, 258–272 (2023).

Haas, R. & Hudson, W. Pavement Asset Management (Wiley, 2015).

Chu, C., Wang, L. & Xiong, H. A review on pavement distress and structural defects detection and quantification technologies using imaging approaches. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (English Edition). 9, 135–150 (2022).

Guerrieri, M. & Parla, G. Flexible and stone pavements distress detection and measurement by deep learning and low-cost detection devices. Eng. Fail. Anal. 141, 106714 (2022).

Mozaffari, L., Mozaffari, A. & Azad, N. L. Vehicle speed prediction via a sliding-window time series analysis and an evolutionary least learning machine: A case study on San Francisco urban roads. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 18, 150–162 (2015).

Pompigna, A. & Mauro, R. Smart roads: A state of the Art of highways innovations in the smart age. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 25, 100986 (2022).

Garita-Durán, H., Stöcker, J. P. & Kaliske, M. Deep learning-based system for automated damage detection and quantification in concrete pavement. Results Eng. 25, 104546 (2025).

Jiang, J., Ketabdari, M., Crispino, M. & Toraldo, E. Estimating vehicle braking distance over wet and rutted pavement surface through back-propagation neural network. Results Eng. 21, 101686 (2024).

Jimenez Rios, A., Ben Seghier, M. E. A., Plevris, V. & Dai, J. Explainable ensemble learning framework for estimating corrosion rate in suspension Bridge main cables. Results Eng. 23, 102723 (2024).

Khadijeh, M., Kasbergen, C., Erkens, S. & Varveri, A. Combining deep neural networks and Gaussian processes for asphalt rheological insights. Results Eng. 26, 105629 (2025).

Zhong, J. et al. Texture-image coupled fusion analysis for pavement skid resistance measurement. Measurement 256, 118272 (2025).

Medina, R. LIamas, J. Zalama, E and. Gómez-García-Bermejo, J. Enhanced automatic detection of road surface cracks by combining 2D/3D image processing techniques. International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 7025156778–782, (2014)

Shang, J., Zhang, A. A., Dong, Z., Zhang, H. & He, A. Automated pavement detection and artificial intelligence pavement image data processing technology. Autom. Constr. 168, 105797 (2024).

Jing, J. et al. Self-adaptive 2D–3D image fusion for automated pixel-level pavement crack detection. Autom. Constr. 168, 105756 (2024).

Xing, C. et al. A lightweight detection method of pavement potholes based on binocular stereo vision and deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 436, 136733 (2024).

Hoang, N. D. Image processing based automatic recognition of asphalt pavement patch using a metaheuristic optimized machine learning approach. Adv. Eng. Inform. 40, 110–120 (2019).

Ranjbar, S., Nejad, F. M. & Zakeri, H. Image-based severity analysis of asphalt pavement bleeding using a metaheuristic-boosted fuzzy classifier. Autom. Constr. 166, 105797 (2024).

Ranjbar, S., Moghadas Nejad, F. & Zakeri, H. Image-based severity analysis of asphalt pavement bleeding using a metaheuristic-boosted fuzzy classifier. Autom. Constr. 166, 105655 (2024).

Nasertork, A., Ranjbar, S., Rahai, M. & Moghadas, F. Pavement raveling inspection using a new image texture-based feature set and artificial intelligence. Adv. Eng. Inform. 62, 102665 (2024).

Zhong, J. et al. An investigation of texture–friction relationship with laboratory ring-shaped asphalt mixture specimens via close-range photogrammetry. Constr. Build. Mater. 442, 137508 (2024).

Zong, Y. et al. Effect of morphology characteristics on the Polishing resistance of coarse aggregates on asphalt pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 341, 127755 (2022).

Kane, M., Lim, M., Tan, M. & Edmondson, V. A new predictive skid resistance model (PSRM) for pavement evolution due to texture Polishing by traffic. Constr. Build. Mater. 342, 128052 (2022).

Wang, D., Liu, P., Xu, H., Kollmann, J. & Oeser, M. Evaluation of the Polishing resistance characteristics of fine and coarse aggregate for asphalt pavement using Wehner/Schulze test. Constr. Build. Mater. 163, 742–750 (2018).

Pomoni, M., Plati, C., Kane, M. & Loizos, A. Polishing behaviour of asphalt surface course containing recycled materials. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 11, 711–725 (2022).

Yun, D., Tang, C., Gao, J., Ran, M. & Zhou, X. Effect of asphalt mixture gradation characteristics on long-term skid resistance under high temperature and heavy load. Constr. Build. Mater. 441, 137386 (2024).

Descantes, Y. & Hamard, E. Parameters influencing the polished stone value (PSV) of road surface aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 100, 246–254 (2015).

Guo, F. et al. Study on the skid resistance of asphalt pavement: A state-of-the-art review and future prospective. Constr. Build. Mater. 303, 124411 (2021).

Zhan, Y. et al. Effect of aggregate properties on asphalt pavement friction based on random forest analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 292, 123467 (2021).

Guide for Pavement Friction. Transportation Research Board & Washington, D. C. [ (2009). https://doi.org/10.17226/23038]

Zhang, A. A. et al. Intelligent pavement condition survey: overview of current researches and practices. J. Road. Eng. 4, 257–281 (2024).

Weng, Z. et al. Pavement texture depth Estimation using image-based multiscale features. Autom. Constr. 141, 104404 (2022).

Gökalp, İ., Uz, V. E., Barstuğan, M. & Balcı, M. C. Image processing and artificial neural network based determination of surface mean texture depth on lab-controlled chip seal pavement samples. Sci. Rep. 14, 27885 (2024).

Pan, S. et al. Automatic pavement texture recognition using lightweight few-shot learning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 381, 20220209 (2023).

Hoang, N. D. Automatic detection of asphalt pavement raveling using image texture-based feature extraction and stochastic gradient descent logistic regression. Autom. Constr. 105, 102843 (2019).

Hsieh, Y. A. & Tsai, Y. Automated asphalt pavement raveling detection and classification using convolutional neural network and macrotexture analysis. Transp. Res. Rec. 2675, 984–994 (2021).

Nhat-Duc, H. & Van-Duc, T. Comparison of histogram-based gradient boosting classification machine, random forest, and deep convolutional neural network for pavement raveling severity classification. Autom. Constr. 148, 104767 (2023).

Hoang, N. D. & Tran, V. D. Computer vision based asphalt pavement segregation detection using image texture analysis integrated with extreme gradient boosting machine and deep convolutional neural networks. Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation 196, 111207 (2022).

Nhat-Duc, H. & Van-Duc, T. Computer vision-based severity classification of asphalt pavement raveling using advanced gradient boosting machines and lightweight texture descriptors. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civil Eng. 47, 4059–4073 (2023).

Daneshvari, M. H., Nourmohammadi, E., Ameri, M. & Mojaradi, B. Efficient LBP-GLCM texture analysis for asphalt pavement raveling detection using eXtreme gradient boost. Constr. Build. Mater. 401, 132731 (2023).

Daneshvari, M. H., Mojaradi, B., Ameri, M. & Nourmohammadi, E. Automation detection of asphalt pavement bleeding for imbalanced datasets using an anomaly detection approach. Measurement: J. Int. Meas. Confederation. 235, 114987 (2024).

Daneshvari, M. H., Mojaradi, B., Ameri, M. & Nourmohammadi, E. Hybrid texture analysis of 2D images for detecting asphalt pavement bleeding and raveling using tree-based ensemble methods. Alexandria Eng. J. 107, 150–164 (2024).

Lei, J. et al. Research on the evolution law of aggregate micro-texture during long-term wearing of asphalt pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 444, 137846 (2024).

Lei, J., Zheng, N., Chen, X., Bi, J. & Wu, X. Research on the relationship between anti-skid performance and various aggregate micro texture based on laser scanning confocal microscope. Constr. Build. Mater. 316, 125984 (2022).

McKnight, J., Bedle, H. & Saneiyan, S. Improving electrical resistivity tomography interpretation with Gray level co-occurrence matrix textural attributes. Sci. Rep. 15, 30868 (2025).

Cao, M. T., Nguyen, N. M., Chang, K. T. & Tran, X. L. Hoang, N. D. Automatic recognition of concrete spall using image processing and metaheuristic optimized logitboost classification tree. Adv. Eng. Softw. 159, 103031 (2021).

Tomita, F. & Tsuji, S. Computer Analysis of Visual Textures (Springer Science + Business Media, 1990).

Haralick, R. M., Shanmugam, K. & Dinstein, I. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybernetics. SMC-3, 610–621 (1973).

Kumar, G., Banerjee, R., Singh, K. & Choubey, D. Arnaw. Mathematics for machine learning. J. Math. Sci. Comput. Math. 1, 229–238 (2020).

Berry, M. W., Mohamed, A. & Yap, B. W. Unsupervised and Semi-Supervised Learning. Springer, Cham, 22475-2 (2019)

Altman, N. S. An Introduction To Kernel and Nearest Neighbor Nonparametric Regression (Springer, 1992).

Breiman, L., Friedman, J. H., Olshen, R. A. & Stone, C. J. Classification and Regression Trees (Routledge, 2017).

Simm, J., Magrans de Abril, I. & Sugiyama, M. Tree-based ensemble multi-task learning method for classification and regression. IEICE. Trans. Inf. Syst. E97.D, 1677–1681 (2014).

Shang, H. et al. A hybrid cloud detection and cloud phase classification algorithm using classic threshold-based tests and extra randomized tree model. Remote Sensing of Environment 302,113957 (2024).

Ho, T. K. Random decision forest. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, (1995).

He, Q. et al. Evaluation of landslide susceptibility of mountain highway based on RF and SVM models. Sci. Rep. 15, 24991 (2025).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Mislan, H., Haviluddin, Hardwinarto, S., Aipassa, M. & Sumaryono & Rainfall monthly prediction based on artificial neural network: A case study in Tenggarong Station, East Kalimantan – Indonesia. Procedia Comput. Sci. 59, 142–151 (2015).

Wu, D. et al. Prediction of polycarbonate degradation in natural atmospheric environment of China based on BP-ANN model with screened environmental factors. Chem. Eng. J. 399, 125878 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. Intelligent prediction model of a polymer fracture grouting effect based on a genetic algorithm-optimized back propagation neural network. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 148, 105781 (2024).

Ruan, S. et al. Multifactor interpretability method for offshore wind power output prediction based on TPE-CatBoost-SHAP. Comput. Electr. Eng. 123, 110081 (2025).

Hanifi, S., Cammarono, A. & Zare-Behtash, H. Advanced hyperparameter optimization of deep learning models for wind power prediction. Renew. Energy. 221, 119700 (2024).

Bacanin, N. et al. Multivariate energy forecasting via metaheuristic tuned long-short term memory and gated recurrent unit neural networks. Inf. Sci. 642, 119122 (2023).

Luque, A., Carrasco, A., Martín, A., e las Heras, A. & d The impact of class imbalance in classification performance metrics based on the binary confusion matrix. Pattern Recognit. 91, 216–231 (2019).

Saifullah, S., Fauziyah, Y. & Aribowo, A. S. Comparison of machine learning for sentiment analysis in detecting anxiety based on social media data. J. Inf. 15, 45 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mansour Fakhri supervised the research and provided overall guidance. Seyed Vahid Pourjafar conceived, designed, and conducted the study, performed data handling, data analysis, preprocessing, and drafted the manuscript. Mohammad Hassan Daneshvari contributed to programming, data analysis, image processing, machine learning, and assisted with manuscript revision. All authors discussed the results, reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fakhri, M., Pourjafar, S.V. & Daneshvari, M.H. Texture-based image analysis and explainable machine learning for polished asphalt identification in pavement condition monitoring. Sci Rep 15, 43167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27203-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27203-6