Abstract

We evaluated the clinical and cost effectiveness of an online sleep intervention (COSI) for parents of children with epilepsy. We conducted a multicentre, parallel-group, unblinded, randomised controlled trial. We recruited children aged 4–12 years with epilepsy and sleep problems through 26 UK outpatient clinics. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) via a computer-generated minimisation algorithm. The primary outcome was the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) at three months. Cost-effectiveness was estimated at six months. We conducted intention to treat analyses. 85 children were enrolled (42 SC; 43 SC + COSI). At three months, the adjusted mean CSHQ difference between arms was 3.00 (95% CI 0.06–5.93; p = 0.05), indicating significant superiority of SC. Children in the SC + COSI group showed a mean 16.5-minute reduction in sleep onset latency by actigraphy and parents increased their knowledge. Only 23 (53%) families accessed the core intervention materials. Incremental mean cost of SC + COSI was £1,232 (95% credibility interval £535–£3,455) with a mean incremental Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) of 0.00 (95% CI -0.03 to 0.04), yielding an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £433,167 per QALY gained a (0.04 probability of being cost-effective at the £30,000/QALY threshold). Improved objective sleep onset latency and enhanced parental knowledge suggest that the underlying behaviour change techniques hold value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and rationale

There is a movement towards a more holistic clinical approach to the management of childhood epilepsy, incorporating aspects that are important to children and their parents such as mental health and sleep1. This gradual broadening of emphasis presents a practical challenge because the NHS workforce is not equipped to meet the demands of managing these issues within current resources2. Sleep problems, in particular, represent a substantial and rising public health issue,3 and are common in children. Children’s sleep problems are associated with impairments in learning, behaviour, daytime functioning, and overall quality of life, as well as disruptions to their family’s sleep, functioning and relationships4. Sleep can be a source of considerable anxiety in children with epilepsy (CWE) because of the fear of seizures5. Unsurprisingly, parents report that sleep problems are 12 times more common in CWE, even in the absence of nocturnal seizures6. Furthermore, sleep disruption may also exacerbate seizure activity by affecting sleep architecture and quality, creating a vicious cycle sometimes leading to pseudo drug-resistance7. Sleep has been identified as a vital concern for young people with epilepsy1 and is recognised by people with lived experience as a research priority8. However, there exists an enormous imbalance between patient needs and children’s sleep-related healthcare provision in the UK2. Accessible and scalable approaches to address sleep problems in this population are therefore urgently needed, with the potential for substantial health and economic benefits.

Tailored sleep behaviour intervention methods are necessary for CWE because of specific clinical considerations5. In CWE, insomnia-related sleep problems typically include difficulty with sleep initiation (settling and falling asleep), maintenance (night or early morning wakings), short sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, and sleep-related anxieties. Several parent-implemented, face-to-face behavioural management techniques exist for treating behavioural insomnia in typically developing children9. These techniques have also been used successfully with children who have a range of neurodevelopmental disorders, including ADHD and autism but their use in CWE remains under-explored10. Interventions delivered online are now a well-proven strategy to improve access to services, particularly in mental health care. Behavioural sleep management is especially suited to eHealth adaptation because techniques can be standardised and delivered in modular form. Evidence supports the effectiveness of online sleep management programmes for typically developing children and some clinical populations11. With this rationale, we developed CASTLE Online Sleep Intervention (COSI) - an online, parent-directed, modular behavioural sleep intervention specifically for children with epilepsy5. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical and incremental cost-effectiveness of standard care (SC) plus COSI compared with SC alone for children with epilepsy in NHS context.

Hypothesis

SC + COSI will improve the mean total parent-reported child sleep problem [Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ)] score by 6.25 points from baseline to 3-months compared with SC alone in children with epilepsy aged 4–12 years.

Methods

Study design

This was a multicentre, parallel-group, unblinded randomised controlled trial with internal pilot conducted across 26 hospital paediatric outpatient clinics in the UK. The study was prospectively registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Registry (ISRCTN13202325, 9/9/2021). The study protocol has been published in the NIHR Library and in print12. Reporting follows guidance from the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 201013, CONSORT extension for non-pharmacological trials 201714 and Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022)15. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). The trial was approved by the Riverside Research Ethics Committee (IRAS ID 289580, REC 21/EM/0205 on 28/10/2021 with HRA approval 17/01/2022).

Patient and public involvement

The study was designed and conducted in collaboration with the research programme Advisory Panel (AP). The advisory panel (AP) consisted of three children with epilepsy, ten parents of children with epilepsy and one adult with epilepsy who has lived with epilepsy since childhood. Two of the AP were consulted at the grant application stage and were co-applicants on the programme grant. The AP advised on all aspects of the study design, including the outcome measures. Patient-facing documents were co-designed with the AP to ensure that the language and terminology used were suitable, consistent, and understandable. Strategies and materials for public dissemination were developed in collaboration with the AP.

Sample size

The trial aimed to recruit 110 participants, sufficient to detect a clinically meaningful difference of 6.25 with a standard deviation of 8.9 in 3-month CSHQ scores with 90% power at a 5% significance level, accounting for potential attrition of 10%. However, owing to diminished recruitment following the Covid-19 pandemic, 85 participants were randomised, which provided 80% power to detect change in the primary endpoint.

Participants

Children aged 4 to 12 years were recruited from 26 NHS outpatient paediatric epilepsy clinics across the United Kingdom between 30/8/2022 and 18/10/2023. Eligibility criteria included clinician-confirmed epilepsy and parent-reported sleep problems16. Exclusion criteria included children with moderate/severe learning disabilities or families without sufficient English to understand the intervention materials.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised with a 1:1 allocation ratio using a computer-generated minimisation algorithm with a random element of 0.8 balancing for site and sleep medication.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding was not feasible for participants, caregivers, or clinical outcome assessors. Statisticians were blinded until the point of analysis.

Interventions

Participants randomised to the control Standard Care (SC) group received usual care provided by their paediatric epilepsy services. Participants randomised to the experimental SC + COSI group received SC plus access to an online parent-directed behavioural sleep intervention. The COSI intervention is a self-paced, tailored, modular e-learning package incorporating sleep information (modules A-B) and 20 evidence-based behavioural sleep strategies (modules D-J)5. Through co-production with parents of children with epilepsy, adaptations were made to the content and presentation of standard intervention material to acknowledge and emphasise key seizure-specific issues to best meet parents of CWE’s needs5. Adaptations included embedding parent and child experiences in the intervention in short animations, adding information requested by parents, such as the links between sleep and seizures and managing child and parental anxieties around sleep, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, as well as developing functionality to personalise content delivery.

Assessment

Parent-reported and child-reported outcomes were assessed at baseline, three months and six months. Seizure outcomes were collected by clinicians at follow-up appointments and entered into a central, secure REDCAP database. A revised study design was implemented to extend the recruitment period, which ensured that every patient had primary outcome data collected at the three-month follow-up visit, but a subset of patients did not receive a six-month follow-up visit.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the total parent-reported child sleep problem score on the (CSHQ) at 3 months post-randomisation17.

Secondary outcomes

Children

Time to 6-month seizure remission; time to first seizure; total score on Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ); SleepSuite overnight memory consolidation assessment; actigraphy variables (total sleep time, sleep latency, sleep efficiency), Children with Epilepsy Quality of Life (CHEQOL): Parent and Child Questionnaire, total sickness-related school absence days.

Caregivers

Knowledge about Sleep in Childhood (KASC) scale score, Insomnia Severity Index (ISI); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), WHO-5 Well-Being Index, Parenting Self-Agency Measure (PSAM).

Health economic outcome

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), calculated using costs from the NHS and Personal Social Services perspective and QALYs derived from the Child Health Utility 9 Dimension Index (CHU9D).

COSI engagement assessments

Descriptive, e-learning data about parents’ use of the intervention website, including how many modules parents looked at and how many times they viewed each individual module. Parents were defined as COSI engagers if they accessed one or more of the modules that included advice about child sleep-behaviour change strategies (D-J), on one or more occasions.

COSI evaluation outcome

COSI was evaluated via an embedded online questionnaire, which became available 3 months after randomisation to the COSI arm of the trial. Families were prompted to complete this via a text message and, if required, by a phone call reminder after a week of non-completion. The evaluation questionnaire assessed the following aspects of COSI:

-

(i)

Functionality of website (e.g. the frequency with which families could access the different features of COSI such as viewing videos). Responses were on a 5-point scale of ‘never’ (0) to ‘always’ (4).

-

(ii)

Parental approval of COSI via the question “Would you recommend this sleep programme to other families who have children with epilepsy?”. Responses were on a 5-point scale of ‘never’ (0) to ‘always’ (4).

-

(iii)

Use of COSI content - for each of the 20 individual sleep management strategies included in COSI, parents reported if they had used the technique (yes/no response) and, if ‘yes’, how helpful they found this on a 5-point scale (0–4) from ‘very unhelpful’ to ‘very helpful’ or, if ‘no’, they indicated whether this was because they were already using this method, because they had unsuccessfully tried it in the past or because they chose not to.

Qualitative research assessments

The aim was to critically explore the experiences of children and parents/caregivers in relation to living with epilepsy, sleep (importance, challenges, management strategies), use of COSI and factors related to participation in the trial (e.g. why participate, challenges to sustaining participation, and use of actigraphs). A subset of families (maximum 60, split between the two groups) were invited to participate in remote audio or audio-video interviews within 3 weeks of completion of other data collection at 3 and 6 months after randomisation.

Internal pilot

Recruitment rate, consent rate, follow-up rate, intervention failure rate, and completeness of data for the primary outcome were assessed during a 6-month internal pilot. Pre-specified progression criteria for continuation to the full trial comprised: Green - Continue if at least 22 participants had been randomised; Amber - Implement additional recruitment strategies if number of participants randomised between 15 and 21; Red - If recruitment < 15 discuss ending the trial with the oversight committees.

Statistical methods

Baseline categorical data are presented using counts and percentages and continuous data presented as median with range. Primary outcome data were analysed using intention-to-treat (ITT) principles. Total CSHQ score was calculated using the 5-point scoring approach with higher score reflecting greater sleep problems. As the 22-item CSHQ tool had not been validated, the overall Cronbach alpha was calculated as measure of internal consistency and individual items that showed increase in Cronbach’s alpha on deletion and very low “Corrected Item-Total Correlation” (< 0.20) were omitted from the total score value (items 16,19,20) for the primary analysis. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the effect of alternative scoring approaches and to make comparisons with the more widely used 33-item CSHQ questionnaire18 (see Appendix 1, Supplementary Tables).

Continuous outcomes were compared at relevant time points (3 months or 6 months) using linear mixed effects regression models with fixed effects included for intervention, baseline measure, baseline sleep medication status (Y/N) and random effects for centre. Time to event outcomes were analysed using a Cox proportional hazards model including intervention, baseline sleep medication status (Y/N) and centre effects. Analyses were based on complete cases, which are unbiased when data is missing completely at random19. The adjusted treatment effect estimates (mean difference for continuous outcomes and hazard ratio for time to event outcomes) comparing SC + COSI against SC are presented with a 95% confidence interval with statistical tests conducted at the 5% two-sided significance level. Unadjusted analyses were examined for completeness. Analyses included patients with follow-up data captured within ± 1 month of the timepoint of interest. Owing to the revised study design, a subset of participants did not achieve a full 6 months of follow-up and sensitivity analyses were conducted that included participants with data collected at > 1 month after the timepoint of interest.

Health economic evaluation

The cost-effectiveness analysis (Appendix 2) used patient-level data to compare SC + COSI with SC alone on an ITT basis, over the 6 ± 1 month trial period. All resource use was measured, irrespective of whether it was related to epilepsy. Within-trial resource use was obtained from routine Patient Level Information and Costing System (PLICS) data, trial case report forms, and resource use questionnaires that were administered at or shortly after baseline, randomisation, follow-up at 3 month (± 1-month), and follow-up at 6 month (± 1-month) post-randomisation visits. Unit costs were obtained from standard sources, valued in pound sterling (£) based on 2021-22 prices, and with inflation indices applied as necessary (Appendix 2). The cost of COSI was estimated as the cost of developing the intervention divided by the number of users. Utilities were estimated from responses to the CHU9D and applying UK tariffs.

Missing data were treated as missing at random and imputed using multiple imputation with chained equations with two-level predictive mean matching to create 70 complete data sets. The complete datasets were analysed using a multivariate Bayesian regression model, with a log-link function and hurdle Gamma distribution for costs and an identity link with Gaussian distribution for QALYs. The model included covariates for treatment allocation with random effects based on treatment site, use of sleep medication at baseline (binary), baseline costs, and baseline utility. Posterior draws from the joint distribution of incremental costs and QALYs were used to analyse uncertainties in the economic evaluation, presenting the probability that the SC + COSI was cost-effective across a range of willingness-to-pay thresholds. Sensitivity analyses were used to explore key cost drivers, the impact of different cost perspectives, varying the cost of COSI, and the inclusion of spillover utility for primary carers. The robustness of modelling assumptions and methods were assessed with respect to handling missing data, and the inclusion of participants who were randomised but too late to be followed up for the 6 ± 1 month trial period. The analysis was conducted in R (Version 4.4.1).

Protocol conduct

Three substantial amendments were made and 14 deviations from the protocol were recorded. The trial was conducted and reported according to the published protocol, which was approved by an independent programme steering committee and a data monitoring and ethics committee. The data monitoring and ethics committee reviewed trial data and conduct at regular intervals throughout the trial. The trial was prospectively registered with the ISRCTN (ISRCTN13202325) on 09/09/2021.

Role of funding source

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of any report or publication.

Results

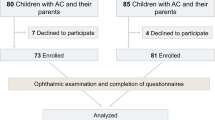

85 children were enrolled between 30.08.2022 and 18.10.2023, (42 SC; 43 SC + COSI). Eighty-five children were enrolled and randomised (42 to SC, 43 to SC + COSI). Participant flow is detailed in Fig. 1. Baseline characteristics of child participants are provided in Table 1. Groups were comparable at baseline regarding age, sex, ethnicity, diagnosis of epilepsy syndrome, and baseline sleep problem scores.

Outcomes and Estimation

Primary outcome

All 85 randomised participants completed the baseline CSHQ questionnaire but only 72 (85%) also completed the 3-month CSHQ form within the required ± 1 month follow-up window and were included in the primary analysis. Among the 34 participants who completed the baseline and 3-month CSHQ scores within the SC + COSI arm, 19 (56%) were COSI engagers. The mean CSHQ score at 3 months was lower in the SC compared to the SC + COSI groups (mean difference = 3.00(1.46); 95% CI: 0.06–5.93, p= (0.05)), Table 2.

Secondary outcomes

29 families provided complete actigraphy data at baseline and 3-month follow-up. Children in the SC + COSI group fell asleep on average − 16.35 min faster (95% CI: −30.63 to −2.07; p = 0.03) and 75% of these families were COSI engagers. Parental sleep knowledge improved significantly in the SC + COSI group, 2.03 (0.48) (95% CI: 1.01 to 3.05; p = < 0.001); no significant differences were observed in seizure control or other secondary outcomes (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6).

COSI engagement outcome

Of the 43 families assigned to the COSI arm, 33 logged-on. Ten of these only viewed the introductory modules (A & B). Twenty-three were COSI engagers (i.e. accessed behaviour-change content in modules D-J on one or more occasions), whilst 20 families did not engage with the core behaviour change material.

COSI evaluation

Twelve parents completed the evaluation questionnaire. However, one had not accessed any content and so their responses were excluded. The remaining 11 parents were COSI engagers.

-

(i)

Functionality: all elements of COSI functioned well (mean scores all ≥ 3.6, maximum 4.0).

-

(ii)

Parental Approval: The mean parental approval score was 3.6 (maximum 4.0), indicating families would strongly recommend COSI to other parents of children with epilepsy.

-

(iii)

Use of COSI: All 20 sleep behaviour change strategies were reportedly used (19/20 strategies were used by multiple families). Of the 94 reports of a strategy being used as a result of COSI, 81 (86.2%) of these were reported to be ‘helpful or ‘very helpful’. The other 13 (13.8%) uses were reported to have had no impact and none were reported to make sleep worse. Where strategies were not used and an explanation was given (n = 122) this was because families were already using this (n = 76), chose not to use it (n = 26) or had tried the strategy unsuccessfully in the past (n = 18).

Qualitative interview outcomes

Twenty-two families participated in interviews: 13 in the SC arm (7 boys, 6 girls; 4-13yrs, mean 9.3yrs) and nine in the SC + COSI arm, of which six families were categorized as COSI engagers (4 boys, 2 girls; 8-12yrs, mean 9.8yrs) and three as COSI non-engagers (1 boy, 2 girls; 10-13yrs, mean 11.3yrs). Two of the three COSI non-engagers cited family crises as reasons for non-engagement. Five COSI engager parents talked of being familiar with some aspects of COSI content, noting that suggested routines and practices were already “well ingrained” or had been “advised before”. Despite familiarity, benefits did accrue such as success using a “star chart to try to encourage him to sleep in his own bed” and introducing “wind down” time or the potential for introducing “more relaxation” practices. One boy thought COSI practices were “helping me a bit” and believed they would help his sleep “improve over the long-term”. Perceived gaps in COSI information included advice about managing “restless … tossing and turning” sleep.

Although COSI content was reported as “high quality”, one father reported feeling “overloaded with information”, some of which he felt conflicted with other sources. Time pressures and distractions affected engagement. Parental sleep disruption and tiredness was problematic for four COSI engager families - problems included falling asleep, staying asleep, waking up or restless sleep.

Health economic outcome

Fifty-eight participants (29 in each group) had 6 ± 1-month follow-up data prior to the trial closing and therefore included in the base case analysis; all 85 randomised participants were included in sensitivity analyses.(Appendix 2) There were missing cost and utility data at each timepoint, the proportions of missing data in the SC + COSI group were generally higher than in the SC group20. Most of the costs were associated with secondary care and COSI20 (Table 7). Unadjusted baseline costs were higher in the SC group and baseline utilities were similar in both groups20. In the adjusted, base case analysis, mean total within-trial costs were £2,021 [95% credibility interval (CrI): 1,352; 3,455] for the SC + COSI group and £1,232 [95% CrI: 535; 2,183] for the SC group. SC + COSI was associated with 0.42 [95% CrI: 0.39; 0.45] QALYs compared with 0.41 [95% CrI: 0.38; 0.45] for SC alone. SC + COSI was more costly than SC alone, with incremental costs of £1,232 [95% CrI: 535; 2,183] and there was a difference of 0.0028 [95% CrI: −0.0326; 0.0368] QALYs compared to SC alone. The resulting ICER is £433,167 per QALY gained (Table 7). At willingness to pay thresholds of £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY, SC + COSI had negative net monetary benefits (NMBs), and probabilities of 0.01 and 0.04, respectively, of being cost-effective (Fig. 2). The sensitivity analyses all supported the base case analysis, with the lowest ICER being £70,246 per QALY gained. SC + COSI was associated with negative NMB even when the cost of COSI was zero and was dominated by SC in two sensitivity analyses (Appendix 2).

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported in the trial.

Discussion

This is the first clinical trial of an online parent-directed behavioural sleep intervention for children with epilepsy and we tested the real-life feasibility of transferring the tools for management of sleep problems directly to parents/caregivers without any professional support. The intervention did not reduce parent-rated sleep problems in children with epilepsy in the NHS context. However, improved objective sleep onset latency and enhanced parental knowledge suggest that the underlying behaviour change techniques may have merit.

We were addressing the question of whether sleep problems can be tackled in this population across the NHS without input from either specialist or non-specialist staff. We found that adding COSI to standard care did not improve subjective parent-reported child sleep problems compared to standard care alone and was not cost-effective. Uptake was low (53%) in line with other digital health interventions in mental health and might partially explain the lack of effectiveness21. Delivering the intervention to a child proxy (parent/caregiver) represents another potential source of effect dilution. Objectively though, the intervention brought forward child sleep onset by 16.35 min, a clinically significant improvement22. Caregivers who engaged with COSI would strongly recommend the intervention to other parents, and they found 86% of the techniques helpful or very helpful. COSI also improved parental knowledge. We conclude that the underlying behavioural change techniques are efficacious but at the population level an online parent-based intervention does not result in parent-reported improvements in child sleep problems. The trial informs public health strategy for managing sleep problems in children with complex needs and suggests alternative future implementation approaches such as sleep training of the clinical care team.

When behaviour-change techniques are translated to digital format, there is often a trade-off between one the one hand access and scalability and on the other hand low user engagement and inconsistent adherence - these latter are common issues in remote self-guided programmes21. With COSI, engagement (logging on) and attrition (progressing to and revisiting core modules) were equally problematic. Sometimes known as Eysenbach’s Law23, this feature of eHealth trials is a distinct characteristic. Additionally, web metrics alone do not reliably indicate how participants use behaviour change content, making it difficult to assess actual adherence – unfortunately evaluation questionnaires were only completed by 11 families. The subpopulation for whom the intervention brought forward child sleep onset were largely (75%) COSI engagers – a high level of dropout underestimates the effect of the intervention among users who continue to use it23. Digital interventions can improve specific objective measures and increase knowledge, yet they frequently fail to yield meaningful, sustained changes in subjective outcomes without direct human interaction21,24. Digital health researchers emphasise that blended approaches - combining digital tools with professional support - may enhance effectiveness, balancing scalability with the relational support that underpins more robust behaviour change21,24. Successful delivery of mental health assessment and intervention through paediatric epilepsy specialist nurses and graduate psychologists supports the feasibility and scalability of such a blended approach25.

We may ask why the evidence-based behavioural sleep interventions at the core of COSI were not effective for sleep problems in childhood epilepsy yet have proven effective in other paediatric populations, including those with neurodevelopmental disorders, and using varied delivery methods. Sleep disturbances are highly prevalent in children with epilepsy, arising from both neurological and psychosocial factors. The interaction between sleep and epilepsy is inherently bidirectional: poor sleep can lower seizure thresholds, while epileptic activity and its treatment can disrupt sleep continuity and quality. Furthermore, parental concerns, including heightened parental anxiety related to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP)26, may influence sleep behaviours and management practices within families. These factors underscore the need to consider epilepsy-specific influences when evaluating sleep interventions in this population. Parents whose children experienced either longstanding or mild sleep issues might have engaged less or exhibited ceiling or floor effects, highlighting the importance of patient selection. However, the severity of sleep problems in the trial was similar to that in other neurodevelopmental disorder research samples, suggesting low symptom severity is an unlikely explanation27.

Despite a lack of clinically significant change in the primary endpoint of subjective sleep problems, there were important findings in secondary outcomes. First, actigraphy-measured sleep-onset latency decreased by 16.35 min in the intervention group - a notable improvement given that a 10-minute difference is often considered clinically significant22. Sleep-onset latency is frequently cited as a problem in CWE and reported as a major concern for parents26. Interestingly, there seems to be little or no correlation between polysomnography or actigraphy measures with any subscale of the CSHQ28. Second, parents’ knowledge of child sleep improved significantly in the SC + COSI group. Previous studies show that increased parental sleep knowledge correlates with healthier child sleep habits, and such knowledge can be enhanced by both educational and behavioural interventions29. However, knowledge alone may not suffice for behaviour change.

Limitations

There were several limitations of the trial. First, the originally intended sample size was not attained owing to clinical disruption during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Loss of statistical power may theoretically have contributed to inability to demonstrate an effect. Second, while the trial correctly employed an intention-to-treat analysis, (non)adherence measures such as the relative risk of dropping out or of stopping the use of an application, as well as a “usage half-life”, and models reporting demographic and other factors predicting usage discontinuation might have been helpful to modify further iterations of this digital intervention21. Third, there were incomplete data which increased the uncertainty of health economic outcomes and decreased the statistical power of secondary outcomes because the burden of online trial participation may have been excessive for some participants. Fourth, although we used a shorter unvalidated version of a common sleep problems questionnaire, calculations of Cronbach’s alpha and sub-analyses of items common to both short and long instruments (Appendix 1) revealed no significant differences between treatment groups. Last, the lack of blinding could have introduced bias in reporting outcomes although this might be expected to be in favour of the intervention, which was not apparent.

In summary, this web-based intervention for parents of children with epilepsy did not lead to improvements in parent-reported child sleep problems and was not cost-effective. Nevertheless, significant benefits were observed in objective sleep onset latency and in parents’ knowledge of child sleep – benefits seen mostly in a sub-population of COSI engagers. However, the trial faced real-life challenges common in eHealth including poor uptake, high attrition, and uncertainty regarding how fully participants engaged with digital content. The trial findings suggest that sleep problems in childhood epilepsy cannot be tackled across the NHS using online parent-directed resources and standard care alone. Since specialist sleep psychologists will remain scarce in the foreseeable future, training of other non-sleep staff already working with these families, such as epilepsy specialist nurses, in combination with digital tools, may provide an approach to enhance effectiveness - blending technical guidance with motivational support. The evaluation of such a model could be a focus for future research.

Data availability

Quantitative data are available to share with qualified researchers. All requests for data will be reviewed by the CASTLE data access committee, to verify whether the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. Requests for access to the participant-level data from this study can be submitted via email to the corresponding author with detailed proposals for approval. A signed data access agreement with the CASTLE team is required before accessing shared data. Datasets are hosted on the secure FigShare platform. In line with the ethical approval of the study and to protect the identity of research participants, qualitative data (identifiable interviews) will not be available for sharing. King’s College London will consider all data sharing requests and review the requirements both from a practical logistical perspective and in consideration and compliance with GDPR and current Data Protection legislation. All data sharing arrangements will be discussed with our collaborators and with our Information Governance Data Controller utilising a Data Protection Impact Assessment and Data Sharing Agreement(s) to be put in place with the Requester. We will also request acknowledgement of the Terms of the original funding from NIHR.

References

Crudgington, H. et al. Core health outcomes in childhood epilepsy (CHOICE): development of a core outcome set using systematic review methods and a Delphi survey consensus. Epilepsia 60, 857–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.14735 (2019).

Cook, G. et al. A cross-sectional survey of healthcare professionals supporting children and young people with epilepsy and their parents/carers: which topics are Raised in clinical consultations and can healthcare professionals provide the support needed? Epilepsy Behav. 149, 109543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109543 (2023).

The Lancet Diabetes. Sleep: a neglected public health issue. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 12, 365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00132-3 (2024).

Owens, J. A. & Mindell, J. A. Pediatric insomnia. Pediatr. Clin. North. Am. 58, 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.011 (2011).

Wiggs, L., Cook, G., Hiscock, H., Pal, D. K. & Gringras, P. Development and evaluation of the CASTLE trial online sleep intervention for parents of children with epilepsy. Front. Psychol. 12, 679804. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.679804 (2021).

Gutter, T., Brouwer, O. F. & de Weerd, A. W. Subjective sleep disturbances in children with partial epilepsy and their effects on quality of life. Epilepsy Behav. 28, 481–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.06.022 (2013).

Nunes, M. L. Sleep and epilepsy in children: clinical aspects and polysomnography. Epilepsy Res. 89, 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.10.016 (2010).

Cadwgan, J. et al. UK research priority setting for childhood neurological conditions. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 66, 1590–1599. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.16021 (2024).

Mindell, J. A. et al. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep 29, 1263–1276 (2006).

Tsai, S. Y., Lee, W. T., Lee, C. C., Jeng, S. F. & Weng, W. C. Behavioral-educational sleep interventions for pediatric epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep 43 https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz211 (2020).

Mindell, J. A. et al. Long-term efficacy of an internet-based intervention for infant and toddler sleep disturbances: one year follow-up. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 7, 507–511. https://doi.org/10.5664/JCSM.1320 (2011).

Al-Najjar, N. et al. Changing agendas on sleep, treatment and learning in epilepsy (CASTLE) Sleep-E: a protocol for a randomised controlled trial comparing an online behavioural sleep intervention with standard care in children with Rolandic epilepsy. BMJ Open. 13, e065769. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065769 (2023).

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D. & Group, C. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340, c332. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c332 (2010).

Boutron, I. et al. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: A 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0046 (2017).

Husereau, D. et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMJ 376, e067975. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-067975 (2022).

Hiscock, H. et al. Impact of a behavioural sleep intervention on symptoms and sleep in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and parental mental health: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 350, h68. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h68 (2015).

NICHD SECCYD-Wisconsin. NICHD SECCYD-Wisconsin Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (Abbreviated), (2016). https://njaap.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Childrens-Sleep-Habits-Questionnaire.pdf

Owens, J. A., Spirito, A. & McGuinn, M. The children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep 23, 1043–1051 (2000).

Gelman, A. & Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Pal, D. K. et al. Changing Agendas on Sleep, Learning and Treatment in Childhood Epilepsy (CASTLE). NIHR Journals Library in press (2025).

Schwartz, D. G. et al. Apps don’t work for patients who don’t use them: towards frameworks for digital therapeutics adherence. Health Policy Technol. 13, 100848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2024.100848 (2024).

Galland, B. C. et al. Establishing normal values for pediatric nighttime sleep measured by actigraphy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep 41 https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy017 (2018).

Eysenbach, G. The law of attrition. J. Med. Internet Res. 7, e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11 (2005).

Baumel, A. & Kane, J. M. Examining predictors of real-world user engagement with self-guided ehealth interventions: analysis of mobile apps and websites using a novel dataset. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e11491. https://doi.org/10.2196/11491 (2018).

Bennett, S. D. et al. Clinical effectiveness of the psychological therapy mental health intervention for children with epilepsy in addition to usual care compared with assessment-enhanced usual care alone: a multicentre, randomised controlled clinical trial in the UK. Lancet 403, 1254–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02791-5 (2024).

Cook, G., Gringras, P., Hiscock, H., Pal, D. K. & Wiggs, L. No one’s ever said anything about sleep’: A qualitative investigation into mothers’ experiences of sleep in children with epilepsy. Health Expect. 26, 693–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13694 (2023).

Holingue, C. et al. Links between parent-reported measures of poor sleep and executive function in childhood autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sleep. Health. 7, 375–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2020.12.006 (2021).

Markovich, A. N., Gendron, M. A. & Corkum, P. V. Validating the children’s sleep habits questionnaire against polysomnography and actigraphy in school-aged children. Front. Psychiatry. 5, 188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00188 (2014).

McDowall, P. S., Galland, B. C., Campbell, A. J. & Elder, D. E. Parent knowledge of children’s sleep: A systematic review. Sleep. Med. Rev. 31, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.01.002 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the families who participated in the trial, previous trial and programme managers, graduate researchers, families who were members of our Patient and Public Involvement Research Advisory Panel, the independent data monitoring and safety monitoring committee, and the programme steering committee. Our thanks to the dedicated research staff at the NHS recruitment sites: Hassan Al-Moasseb (PI), Diana Princess of Wales Hospital; Philip Amato-Gauci (PI), Hinchingbrooke Hospital & Peterborough City Hospital; Ruchi Arora (PI), Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital; Pronab Bala (PI), Airedale General Hospital; Jane Booker, Barnsley Hospital; Helen Burtenshaw, Peterborough City Hospital; Alys Capell, Peterborough City Hospital; Lisa Capozzi, University Hospital Lewisham; Tanmoy Chakrabarty, Craigavon Area Hospital; Maggie Connon, Royal Aberdeen Children’s Hospital; Julie Cook, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital; Clinton Corin, Worthing Hospital; Emily Cornish, Southampton General Hospital; Sally Cunningham, Craigavon Area Hospital; Alyson Davies, Princess of Wales Hospital; Vivel Desai, Doncaster Royal Infirmary; Karen Duncan, Luton and Dunstable University Hospital; Sarah Farmer, Doncaster Royal Infirmary; Lynsey Felton, James Paget Hospital; Sharon Floyd, St Richard’s Hospital; Lesley-Ann Funston (PI), Craigavon Area Hospital; Emma Gardiner, University Hospital Lewisham; Alok Gaurav (PI), Princess of Wales Hospital; Kumudini Gomez (PI), University Hospital Lewisham; Hannah Goodge, Luton and Dunstable University Hospital; Eilidh Grant, Ninewells Hospital; Donna Griffiths, James Paget Hospital; Dionysios Grigoratos, King’s College Hospital; Suhail Habib (PI), Doncaster Royal Infirmary; Alysha Hancock, Princess of Wales Hospital; Emma Hassan, Homerton Hospital; Nicola Howell, Oxford Children’s Hospital; Sharon Hughes, Arrowe Park University Hospital; Dorothy Hutchinson, Diana Princess of Wales Hospital; Maya Jijin, Craigavon Area Hospital; Alice Jollands (PI), Ninewells Hospital; Amy Kitching, Airedale General Hospital; Helen Leonard (PI), Great North Children’s Hospital; Lucy Lewis, Arrowe Park University Hospital; Susan MacFarlane, Ninewells Hospital; Nadine McCrea (PI), Oxford Children’s Hospital; Dawn Metcalfe, Great North Children’s Hospital; Magdy Moussa, Barnsley Hospital; Michael Moussa (PI), Barnsley Hospital; Amy Nichols, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital; Alice Nicholson, Barnsley Hospital; James Pauling (PI), Arrowe Park University Hospital; Christina Petropoulos, University College London Hospital; Marie-Christina Petropoulos (PI), University College London Hospital; Louise Pollard, Oxford Children’s Hospital; Kate Pryde (PI), Southampton General Hospital; Judith Ratcliffe, Craigavon Area Hospital; Karen Samm, Luton and Dunstable University Hospital; Jasmine Stares, Diana Princess of Wales Hospital & Scunthorpe General Hospital; Elma Stephen (PI), Royal Aberdeen Children’s Hospital; Natalie Stroud, Princess of Wales Hospital; Oluseun Tayo (PI), James Paget Hospital; Sreenivasa Tekki-Rao (PI), Luton and Dunstable University Hospital; Vipin Tyagi, Luton and Dunstable University Hospital; Nina Vanner, Southampton General Hospital; Ramamoorthy Madhepalli Varadan (PI), Scunthorpe General Hospital; Katy Walker (PI), Worthing Hospital & St Richard’s Hospital; Sanjay Wazir (PI), Homerton Hospital; Lucy Wellings, University College London Hospital; Helen Wilson, Peterborough City Hospital.

Funding

This study was funded by National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Programme Grant for Applied Research RP-PG-0615-20007. DKP was additionally supported by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre. Views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DKP, PG conceived the idea for the study and acted as joint Chief Investigators. Together with LB, BC, DAH, CM, CTS, LW they submitted the successful grant application. TC and LSE led on trial management. LW was the workpackage lead for development of the COSI intervention assisted by GC. CM led the workpackage on development of core outcome set. BC led the qualitative workpackage assisted by HS. PG and DKP are co-inventors of the SleepSuite memory consolidation iPad game. PG produced the first draft of the manuscript. AA did the statistical analyses for the manuscript supervised by CTS. LB was the patient and public involvement lead. SL was the programme manager. DAH led the economic analysis and WH performed the economic analyses. All authors had full access to all the data in the study (with the exception of the patient-level PLICS data, which DAH and WASH alone had access to, and the qualitative data which BC and HS alone had access to). All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication, approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gringras, P., Anilkumar, A., Bray, L. et al. Randomised controlled trial of online behavioural sleep intervention for children with epilepsy. Sci Rep 15, 44238 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27206-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27206-3